Abstract

The selective modification of nucleobases with photolabile caging groups provides one of the most versatile strategies to study and control the processes and interactions of nucleic acids. Numerous exocyclic and ring positions of nucleobases have been targeted, but all are formally substituting a hydrogen atom with a photo-caging group. Nature, however, also explicitly uses ring nitrogen methylation, such as m7G and m1A, to change the electronic structure and properties of RNA and control biomolecular interactions essential for translation and turnover. We report that aryl ketones such as benzophenone and α-hydroxyalkyl ketone are photolabile caging groups if installed at the N7 position of guanosine or the N1 position of adenosine. Common photo-caging groups derived from the ortho-nitrobenzyl moiety were not suitable for these positions. Both chemical and enzymatic methods for site-specific modification of N7G in nucleosides, dinucleotides and RNA were developed, opening the door to studying the molecular interactions of m7G and m1A with spatio-temporal control.

Keywords: N7G, photocaging, RNA modification, benzophenone, RNA

Light is a versatile regulatory element because it is fully orthogonal to most cellular components, noninvasive, controllable in timing and localization to tissues, cells and even subcellular compartments.[1] To gain optical control over nucleic acids and the respective biomolecular interactions, irreversible photo(de)activation (“uncaging”) has been applied to nucleosides, nucleotides and oligonucleotides.[1–2] Various photolabile protecting groups have been placed either in the oligomer backbone or on the nucleobases and their removal by light of a defined wavelength ≥365 nm was proven to be compatible with living cells and organisms.[3] The ortho-nitrobenzyl (ONB) group is the most widely used photocaging (PC) group, but numerous alternative scaffolds, derived from coumarins, quinolines, dibenzofuran or the piperonyl group have been explored.[1–2]

Typically, these PC groups are installed at exocyclic heteroatoms, such as the O4 in thymidine or the N4 of cytidine.[4] In addition, the N3 position of thymidine was successfully used in optochemical biology.[3b] In purines, the exocyclic O6 of guanosine and N6 of adenosine are preferred sites for installation of photocaging groups.[5] In the case of guanosine, other positions like the N1, C8 or the exocyclic N2 position have been explored albeit to a much lower extent.[6] For chemo-enzymatic approaches, where photo-caged NTPs are synthesized and enzymatically introduced into DNA or RNA by polymerases, the 5 position of pyrimidines is particularly favorable.[7] Recently, also the post-enzymatic photocaging of DNA was achieved using methyltransferase (MTase)-catalyzed transfer of PC groups to the N6 position of adenosines.[8] In all of these cases, the PC group replaces a hydrogen atom and does not change the charge distribution of the nucleoside.

However, unlike the chemical modifications with PC groups developed to date, nature does not only substitute hydrogen atoms with modifications, but also explicitly uses methylation to change the electronic structure of the molecule. In naturally occurring m7G, m1A and m3C, the modifications confer a positive charge to the nucleobase. Out of these, m7G deserves particular attention because it is (i) one of the most conserved modified nucleosides, (ii) installed by numerous MTases in different organisms and (iii) found in rRNA, tRNA, snRNA as well as part of the 5′ cap in mRNA.[9] In the latter, m7G is crucial for coordinating mRNA translation and turnover by several interactions, such as binding to the translation initiation factor eIF4E or decapping scavenger enzymes DcpS.[10] Due to its importance in biology, we chose the N7 position of guanosine for modification with functional groups with the goal to remove them upon irradiation with light and recover the free guanosine. In the 5′ cap of mRNAs, the G becomes remethylated in cells.[11] To generate photocaged guanosines in different contexts, i.e. from single nucleosides to long mRNAs, we devised both a chemical and an enzymatic preparative route (Scheme 1). PC groups for nucleosides that do not substitute a hydrogen atom but instead introduce a positive charge have not been reported to date to the best of our knowledge.

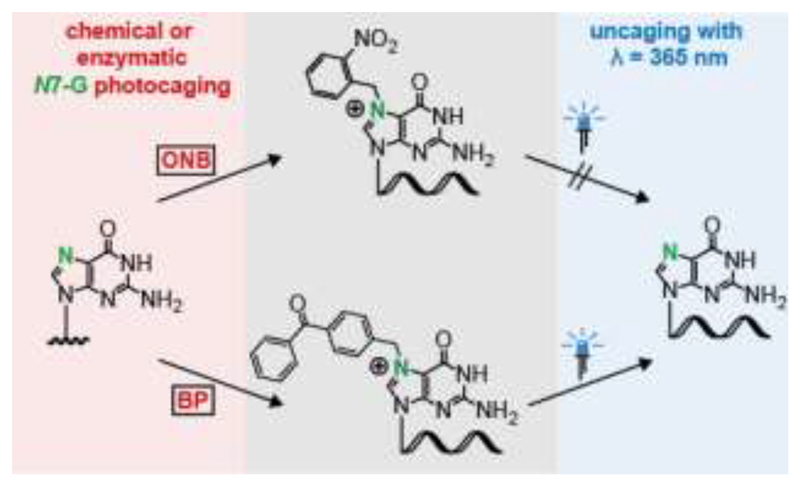

Scheme 1.

Concept for chemical and enzymatic photocaging of the N7 of guanosine using classical ortho-nitrobenzyl (ONB) group or aryl ketones such as benzophenone (BP) to generate the respective nucleoside, 5′ cap or RNA. N7-BP-modified guanosine is uncaged by subsequent irradiation with light (λmax = 365 nm).

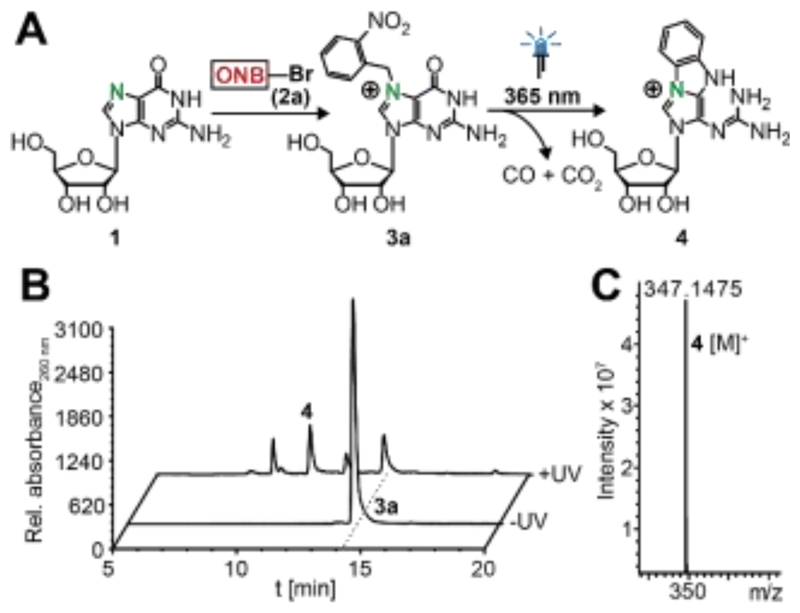

First, we explored the chemical photocaging of guanosine 1 using the well-known ortho-nitrobenzyl (ONB) group as well as para-nitrobenzyl (PNB) as negative control. The N7 of guanosine is the most potent nucleophile in DNA and RNA.[12] However, although N7G methylation was used in Maxam Gilbert sequencing,[13] the chemical modification of N7 has not been exploited to manipulate and control interactions by orthogonal triggers such as light. Building on the good nucleophilicity of the N7 position of guanosine, we reacted guanosine with the respective PC-bromides 2a-b and obtained the expected N7-ortho-nitrobenzyl- (N7-ONB) and N7-para-nitrobenzyl-(N7-PNB) guanosines 3a-b (Figure 1A, Figure S3-S5) in good yields (3a: 53% and 3b: 56%).[14] Subsequent irradiation of 3a, however, did not yield the desired photocleavage to release guanosine 1 but instead a different main product according to HPLC (Figure 1B, Figure S6). Mass analysis revealed a mass of m/z = 347.1475 indicating a mass loss of m/z = 71.98 from 3a, which would correspond to loss of CO and CO2 (Figure 1C). After isolating the product, we could identify the structure of 4 containing a guanidine moiety based on NMR and UHPLC-MS/MS analyses (Figure S7, S50-55). Importantly, the controls 3b as well as unmodified 1 were stable when irradiated under the same conditions (Figure S8-S9). These data indicate that the N7 position of guanosine can be readily derivatized with the well-known ONB group, however the photocleavage leads to an unusual product instead of guanosine, limiting its application in photocaging approaches.

Figure 1.

Chemical modification of the N7 position of guanosine derivatives with the common ONB group and subsequent irradiation. (A) Concept. (B) HPLC analysis before and after irradiation of 3a at 365 nm. (C) Mass analysis of 4 (calculated mass of [C15H19N6O4]+ = 347.1462 [M]+, found: 347.1475).

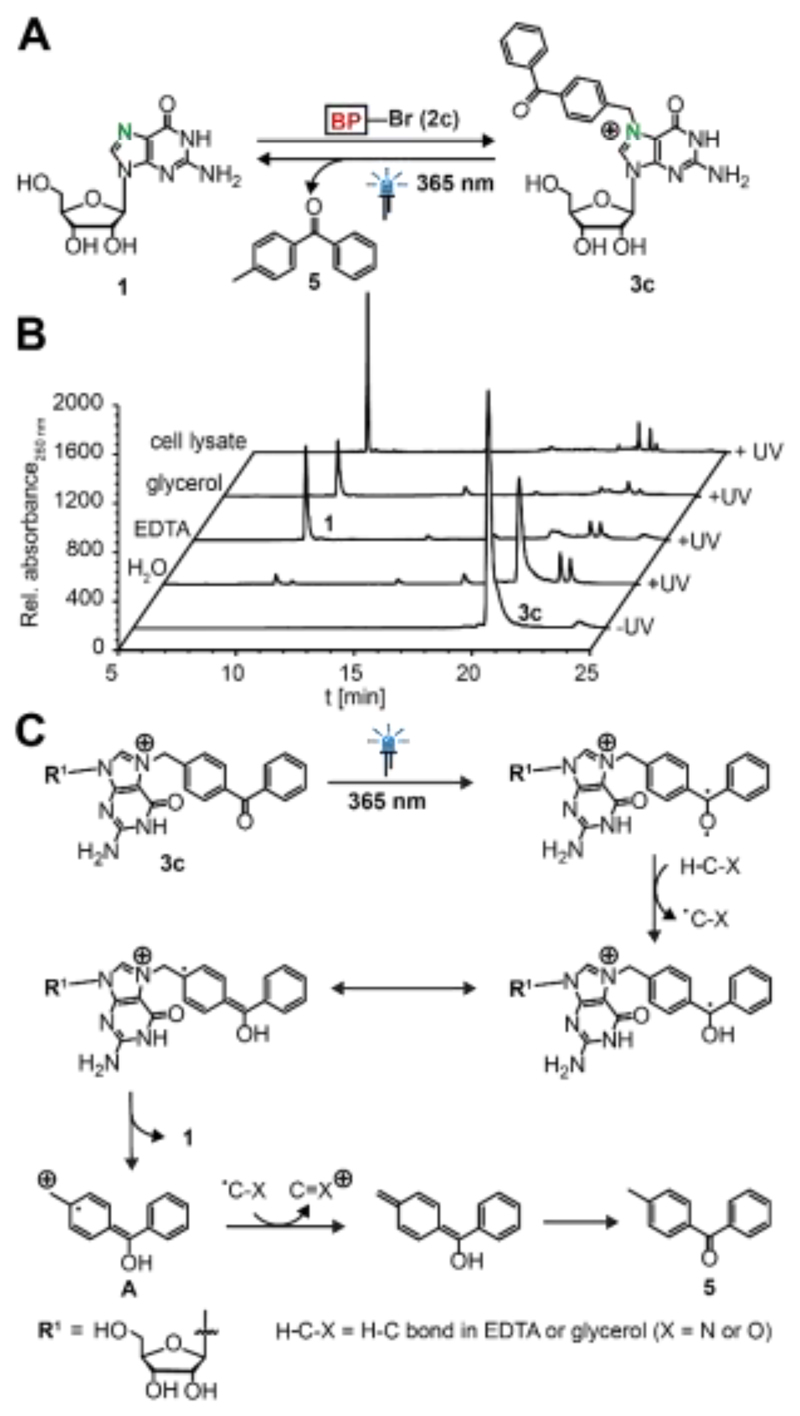

We therefore turned away from the classical PC groups and contemplated alternative light-sensitive groups as potential position-specific PC groups. Photoactivatable aryl ketone derivatives such as benzophenone (BP) are widely used biochemical probes.[15] BP can be manipulated in ambient light and activated at λ ~ 360 nm. It is chemically stable and reacts preferentially with unreactive C-H bonds, which is widely used to study protein-protein but also protein-RNA interactions.[16] The substituents on BP can affect the photochemistry significantly and electron-withdrawing groups increase the efficiency of H-abstraction.[15] We therefore reasoned that the positive charge at the N7 position might lead the radical to a different reaction pathway and therefore considered aryl ketone derivatives, such as BP or a 2-hydroxy-2-methyl-1-phenylpropan-1-one group (HAK), as a potential PC groups for the N7 position of guanosine. We chemically synthesized N7-BP-guanosine 3c (Figure S3-S4) and tested its uncaging properties (Figure 2A). After irradiation of 3c with light (λmax = 365 nm) in buffer containing EDTA and glycerol, we found free guanosine 1 and 4-methylbenzophenone 5 as cleavage products, indicating that BP can be used as photocaging group for the N7 position (Figure S11, Figure S10A-C). To learn more about the cleavage mechanism, we tested the components of the reaction buffer in more detail. We found that the cleavage reaction did not occur in plain water but when EDTA, glycerol or especially cell lysate were present, suggesting that hydrogen abstraction occurs from these buffer components or in the case of cell lysate other components (Figure 2B, Figure S11).

Figure 2.

Chemical preparation of N7-BP-guanosine and subsequent irradiation. (A) Concept. (B) HPLC analysis before and after irradiation of 3c at 365 nm in aqueous solution with different additives. (C) Postulated mechanism for the photocleavage.

A possible cleavage mechanism is shown in Figure 2C. Upon irradiation with λmax = 365 nm, benzophenone generates a triplet ketone, which abstracts a hydrogen atom from a C–H bond of EDTA or glycerol.[16] The ketyl radical thus formed does not engage in a C–C cross link, but the positive charge at the N7 position favors fragmentation to recover guanosine 1 along with the radical cation A. Single electron reduction of A by the EDTA or glycerol derived radical and tautomerization eventually leads to 5.

To test whether this strategy can be applied to the other purine nucleosides, we synthesized N1 benzophenone-modified adenosine (7) (Figure S4).[17] The corresponding methylated nucleoside m1A has recently been identified in mRNA and its functional role is still investigated.[18] This compound also has a positive charge, suggesting that photouncaging of aryl ketone derivatives might be possible in an analogous way. Indeed, we observed that irradiation of 7 with light of 365 nm led to complete formation of adenosine 6 and release of 5 similar to N7-photocaged guanosine (Figure S12-S13).

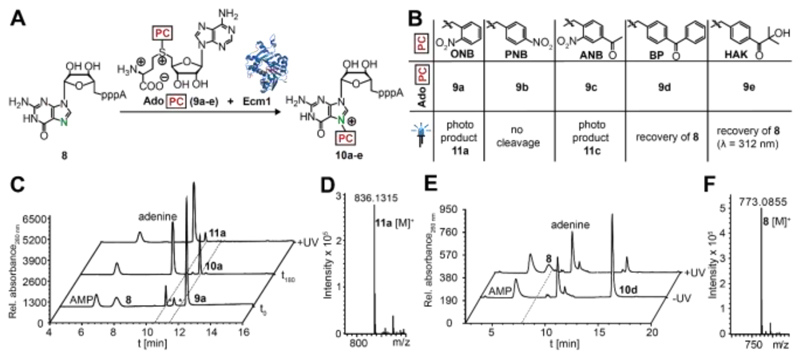

To examine whether our strategy can be extended to more complex molecules, we chose the dinucleotide GpppA 8, which is the hallmark structure of the 5′ cap found in eukaryotic mRNAs. Since site-specific chemical modification is not possible in this case, we devised an enzymatic approach, exploiting the site-specificity of the cap N7-methyltransferase Ecm1 together with its cosubstrate promiscuity.[19] To this end, we synthesized analogs of the natural cosubstrate S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet), suitable for transfer of the classical ONB-based and novel BP-based photocaging groups, i.e. AdoONB 9a, AdoPNB 9b and AdoANB 9c as well as AdoBP 9d (Figure S14).[8, 19c] These AdoMet analogues are well accepted by the highly promiscous Ecm1 resulting in efficient formation of the desired products N7-PC-GpppA 10a-d (Figure 3A-B, Figure S15), according to HPLC and UHPLC-MS analysis (Figure 3C, Figures S16-S19). In line with the results obtained for the nucleoside, irradiation of N7-ONB-GpppA 10a did not yield the uncaged 8 but instead a product 11a with a mass loss of m/z = 71.98 (Figures 1C-D, Figure S20). Similarly, irradiation of N7-ANB-GpppA 10c revealed a new product 11c with a mass loss of m/z = 71.98 (Figure S17,S19E). More detailed analyses of 10a and 11a by enzymatic digestion into single nucleosides using Snake Venom phosphodiesterase revealed that the mass loss occurred exclusively at the N7-ONB-guanosine moiety of the dinucleotide (Figure S21-S23). The controls, PNB-caged GpppA 10b as well as uncaged GpppA 8, remained stable when irradiated under these conditions, in line with our results from the guanosine (Figure S16,S24).

Figure 3.

Enzymatic modification of N7 position of 5′ cap structure GpppA. (A) Concept. (B) Panel of PC groups tested and summary of irradiation results. (B) HPLC analysis of enzymatic reaction of 8 to 10a and subsequent irradiation at 365 nm. (D) Mass analysis of 11a (calculated mass of [C25H33N11O16P3]+ = 836.1314, found: 836.1315). (E) HPLC analysis of enzymatic reaction of 8 to 10d before and after irradiation at 365 nm in buffer. (F) Mass analysis after irradiation, 8: Calculated mass of [C20H28N10O17P3]+ = 773.0841 [M+H]+, found: 773.0855. (* = impurities of 9a)

The benzophenone group, however, was again suitable for photouncaging at the N7G of the 5′ cap. Specifically, 10d was almost completely reacted (79% decrease) when irradiated in buffer, and GpppA 8 was formed as main product (Figure 3E, Figure S18A-B). As in the case of the nucleoside, addition of buffer was required to yield 8 and release 4-methylbenzophenone 5 (Figure S25-S26). Importantly, the uncaged product 8 could be re-modified enzymatically using the BP-group, confirming that the free and functional GpppA 8 had been formed after photocleavage of the BP group (Figure S18C).

To test whether other aryl ketone derivatives could also be suitable for photocaging, we used the α-hydroxyalkyl ketone (HAK) substituent, which is known to normally react according to Norrish type I to give the acylradical and ketylradical.[20] We enzymatically produced N7-HAK-GpppA 10e from GpppA 8 using Ecm1 and AdoHAK 9e (Figure S14-S15,S27). Irradiation of 10e with light of 312 nm in the reaction mixture led to recovery of almost 60% of 5 (Figure S28). UHPLC-MS analysis verified the photocleavage to GpppA 8 and small amounts of side-products, namely the N7-benzoic acid-modified cap analogue 11e,a and the corresponding N7-benzaldehyde-modified one 11e,b (Figure S29-S230). These data show that the HAK group is also a photocaging group for the N7 position of guanosine nucleotides, suggesting that our approach can be extended to other aryl ketones.

Furthermore, we enzymatically modified plasmid DNA at the N6 position of deoxyadenosine using MTase TaqI and AdoBP 9d, which worked efficiently (Figure S31). As expected, no uncaging and thus no plasmid degradation were observed after irradiation with light of 365 nm in buffer (Figure S31B). This showed that the positive charge at the N7 position is required for the photocleavage of aryl ketone derivatives such as BP.

To study whether our strategy is applicable to photocaging of oligonucleotides, we used a panel of short 5–21 nucleotide long RNAs with internal guanosine sites (Figure S33A). These RNA oligonucleotides were incubated with BP-bromide 2c, resulting in N7G but not N1A modification according to UHPLC-MS analysis after digestion and dephosphorylation to single nucleosides. The modified RNAs were then irradiated with light of 365 nm in buffer containing EDTA and single nucleosides were analyzed by UHPLC-MS. The data showed that BP was removed from N7-BP-guanosine after irradiation, suggesting that photocaging and uncaging is possible also in the context of RNA oligonucleotides (Figures S10D-E,S32-S39). Neither the reaction with 2c nor the irradiation at λmax = 356 nm led to RNA degradation as shown in denaturing PAGE analysis (Figure S38). Furthermore, the N7-modified caps were successfully used for in vitro transcription to produce long reporter mRNAs (>1000 nt) and these also remained intact after irradiation under the same conditions (Figure 4B).

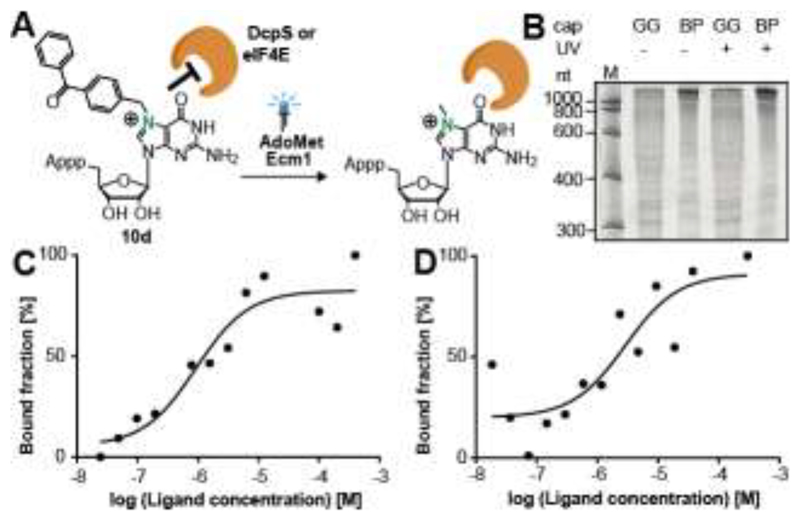

Figure 4.

Photocaging of N7 of guanosines blocks cap binding proteins and can be used to generate long RNAs. (A) Binding assay of N7-BP-GpppA was performed with DcpS (H277N) and eIF4E before and after photouncaging and remethylation. (B) N7-BP-modified cap was used to produce long mRNAs. These were stable under irradiation, if no H-donor was added. (C, D) Binding of 10d to eIF4E and DcpS (H277N) is restored by irradiation and remethylation.

Finally, we tested whether photocaging the N7 position of guanosine can be used to block a biological function (Figure 4A). The 5′ cap is involved in several interactions, most notably eIF4E for translation and decapping enzymes, such as DcpS, for RNA turnover.[10] These interactions require N7 methylation and unmodified caps have been show to become remethylated in the cytoplasm.[11] We measured the Kd values of recombinantly produced eIF4E and the inactive variant DcpS (H277N) for the native and modified cap and found that these proteins are not binding to N7-BP-modified-GpppA, whereas m7GpppA is bound, showing a Kd value in the sub-micromolar range—in line with reports in the literature (Figures S40-S41, Table S1).[10d, 21] After irradiation and enzymatic remethylation mimicking the cellular remethylation, the binding to both proteins was fully restored (Figure 4C-D). These data show that benzophenone can be used to block and release biologically relevant functions.

In summary, we have developed a strategy for photocaging purine nucleosides via formation of purine iminium ions. We present aryl ketone derivatives as new class of photolabile groups for these purine imine positions as exemplified for N7G and N1A and show that the common ONB group is not suitable for N7G. We developed both a chemical and an enzymatic strategy to photocage and release N7G, presenting the first photocaged nucleoside that strictly affecting the Hoogsteen recognition site of G to the best of our knowledge. Hoogsteen interactions are important in RNA biology, e.g. in riboswitches, ribozymes or formation of G quadruplexes. Furthermore, due to the biological importance of m7G in the 5′ cap and the enzymatic remethylation process in nature, our approach significantly expands the chemical biology toolbox and opens the door to control the functions of the 5′ cap with spatio-temporal control in the biological context. The photocaging of N7G and N1A can be further improved by testing additional aryl ketone derivatives that are excited at longer wavelengths and exploiting the two-photon excitation properties of BP in the future.[22]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. W. Dörner, A.-M. Dörner, S. Hüwel and S. Wulff for experimental assistance and Dr. M. Teders for helpful discussion (all WWU). We thank the Glorius group, Dr. F. Höhn and the technical workshop for providing and building custom-made LED boxes (all WWU Münster).This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [RE2796/6-1], the ERC and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (doctoral fellowship to L.A. and Dozentenpreis to A.R.). We thank Prof. C. Lima (Sloan Kettering Institute) for a plasmid coding for DcpS (H277N).

References

- [1].Liu Q, Deiters A. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:45–55. doi: 10.1021/ar400036a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brieke C, Rohrbach F, Gottschalk A, Mayer G, Heckel A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:8446–8476. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Ando H, Furuta T, Tsien RY, Okamoto H. Nat Genet. 2001;28:317–325. doi: 10.1038/ng583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hemphill J, Govan J, Uprety R, Tsang M, Deiters A. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7152–7158. doi: 10.1021/ja500327g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Heckel A, Mayer G. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:822–823. doi: 10.1021/ja043285e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schäfer F, Joshi KB, Fichte MA, Mack T, Wachtveitl J, Heckel A. Org Lett. 2011;13:1450–1453. doi: 10.1021/ol200141v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Menge C, Heckel A. Org Lett. 2011;13:4620–4623. doi: 10.1021/ol201842x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mikat V, Heckel A. RNA. 2007;13:2341–2347. doi: 10.1261/rna.753407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Buff MC, Schäfer F, Wulffen B, Müller J, Pötzsch B, Heckel A, Mayer G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2111–2118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Lusic H, Lively MO, Deiters A. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:508–511. doi: 10.1039/b800166a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ogasawara S. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:2652–2655. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ogasawara S. ACS Synth Biol. 2018;7:2507–2513. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ogasawara S. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:351–356. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Vaníková Z, Hocek M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:6734–6737. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boháčová S, Ludvíková L, Poštová Slavětínská L, Vaniková Z, Klán P, Hocek M. Org Biomol Chem. 2018;16:1527–1535. doi: 10.1039/c8ob00160j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Boháčová S, Vaníková Z, Poštová Slavětínská L, Hocek M. Org Biomol Chem. 2018;16:5427–5432. doi: 10.1039/c8ob01106k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Vaníková Z, Janoušková M, Kambová M, Krásná L, Hocek M. Chem Sci. 2019;10:3937–3942. doi: 10.1039/c9sc00205g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anhäuser L, Muttach F, Rentmeister A. Chem Commun. 2018;54:449–451. doi: 10.1039/c7cc08300a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tomikawa C. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E4080. doi: 10.3390/ijms19124080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Liu H, Rodgers ND, Jiao X, Kiledjian M. EMBO J. 2002;21:4699–4708. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu SW, Jiao X, Liu H, Gu M, Lima CD, Kiledjian M. RNA. 2004;10:1412–1422. doi: 10.1261/rna.7660804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gu M, Fabrega C, Liu SW, Liu H, Kiledjian M, Lima CD. Mol Cell. 2004;14:67–80. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Niedzwiecka A, Marcotrigiano J, Stepinski J, Jankowska-Anyszka M, Wyslouch-Cieszynska A, Dadlez M, Gingras AC, Mak P, Darzynkiewicz E, Sonenberg N, Burley SK, et al. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:615–635. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Burley SK. Cell. 1997;89:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Otsuka Y, Kedersha NL, Schoenberg DR. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2155–2167. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01325-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mukherjee C, Bakthavachalu B, Schoenberg DR. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gillingham D, Geigle S, von Lilienfeld O Anatole. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:2637–2655. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00271k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Maxam AM, Gilbert W. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:560–564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sauter B, Gillingham D. ChemBioChem. 2018;19:1638–1642. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201800235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) La DK, Upton PB, Swenberg JA. In: 14.05 - Carcinogenic Alkylating Agents* McQueen CA, editor. Elsevier; Oxford: 2010. pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]; b) Pautus S, Sehr P, Lewis J, Fortune A, Wolkerstorfer A, Szolar O, Guilligay D, Lunardi T, Decout JL, Cusack S. J Med Chem. 2013;56:8915–8930. doi: 10.1021/jm401369y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5661–5673. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Preston GW, Wilson AJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:3289–3301. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35459h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vik A, Hedner E, Charnock C, Tangen LW, Samuelsen Ø, Larsson R, Bohlin L, Gundersen LL. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:4016–4037. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben-Haim MS, Dai Q, Di Segni A, Salmon-Divon M, Clark WC, Zheng G, et al. Nature. 2016;530:441–446. doi: 10.1038/nature16998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li X, Xiong X, Wang K, Wang L, Shu X, Ma S, Yi C. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Safra M, Sas-Chen A, Nir R, Winkler R, Nachshon A, Bar-Yaacov D, Erlacher M, Rossmanith W, Stern-Ginossar N, Schwartz S. Nature. 2017;551:251–255. doi: 10.1038/nature24456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Schwartz S. RNA. 2018;24:1427–1436. doi: 10.1261/rna.067348.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Holstein JM, Anhäuser L, Rentmeister A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:10899–10903. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Holstein JM, Anhäuser L, Rentmeister A. Angew Chem. 2016;128:11059–11063. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Muttach F, Mäsing F, Studer A, Rentmeister A. Chem - Eur J. 2017;25:5988–5993. doi: 10.1002/chem.201605663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Muttach F, Muthmann N, Reichert D, Anhäuser L, Rentmeister A. Chem Sci. 2017;8:7947–7953. doi: 10.1039/c7sc03631k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mäsing F, Mardyukov A, Doerenkamp C, Eckert H, Malkus U, Nüsse H, Klingauf J, Studer A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:12612–12617. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Niedzwiecka A, Stepinski J, Darzynkiewicz E, Sonenberg N, Stolarski R. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12140–12148. doi: 10.1021/bi0258142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) McGimpsey WC, Scaiano JC. Chem Phys Lett. 1987;138:13–17. [Google Scholar]; b) Cai X, Sakamoto M, Yamaji M, Fujitsuka M, Majima T. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:5989–5994. doi: 10.1021/jp051703b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.