Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are highly prevalent aging-related diseases associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Some findings in human and animal models have linked T2DM to AD-type dementia. Despite epidemiological associations between the T2DM and cognitive impairment, the inter-relational mechanisms are unclear. The preponderance of evidence in longitudinal studies with autopsy confirmation have indicated that vascular mechanisms, rather than classic AD-type pathologies, underlie the cognitive decline often seen in self-reported T2DM. T2DM is a known risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease (CVD), including increased risk of infarcts and small vessel disease in the brain and other organs. Furthermore, neuropathological examinations of post-mortem brains demonstrated evidence of cerebrovascular disease and little to no correlation between T2DM and β-amyloid deposits or neurofibrillary tangles. Nevertheless, the mechanisms upstream of early AD-specific pathology remain obscure. In this regard, there may indeed be overlap between the pathologic mechanisms of T2DM/”metabolic syndrome”, and AD. More specifically, cerebral insulin processing, glucose metabolism, mitochondrial function, and/or lipid metabolism could be altered in patients in early AD and directly influence symptomatology and/or neuropathology.

Keywords: diabetes, alzheimer’s disease, neuropathology, review

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to describe potential aspects of distinction and commonality between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). T2DM is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance (IR), and loss of pancreatic β-cell function (138). T2DM cases make up the majority of diabetes cases worldwide and is associated with obesity and physical inactivity. Between 1980 and 2014, the global prevalence was reported to have risen from 108 to 422 million (113). T2DM typically presents with increased thirst, fatigue, frequent urination, and delayed wound healing (138). Major complications of T2DM include retinopathy, kidney failure, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), neuropathy, and limb amputation (138).

AD is a neurodegenerative disease with an insidious onset and progressive course (1,24). It is the most common form of dementia a contributing factor in approximately 70% of all dementia cases (1,24) – dementia indicating both memory decline and impairment of activities of daily living. The neuropathologic hallmarks of AD are extracellular β-amyloid peptide deposits, which are recognized as “amyloid plaques”, and intracellular hyperphosphorylated tau deposition which make up neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) when occurring in nerve cells (12). The typical course of AD is characterized by impairment of various cognitive domains including memory, executive function, and often comorbid psychiatric changes, ultimately culminating in death (1,24). While speed of progression varies, the average life expectancy after diagnosis is approximately nine years (149,185).

In this review, discussion will initially focus on existing evidence that T2DM related cognitive decline is not associated with increased AD-type neuropathology, but is instead mediated by cerebrovascular pathology. Next, we address the emerging role of glucose, mitochondrial, and lipid metabolism abnormalities as upstream components of AD clinical and neuropathological features. The review will finish by discussing hypothesized causes of cognitive decline in T2DM patients, with or without comorbid AD.

1. T2DM association with clinically- and pathologically-defined AD

T2DM is associated with the clinical features of cognitive decline and AD-type dementia

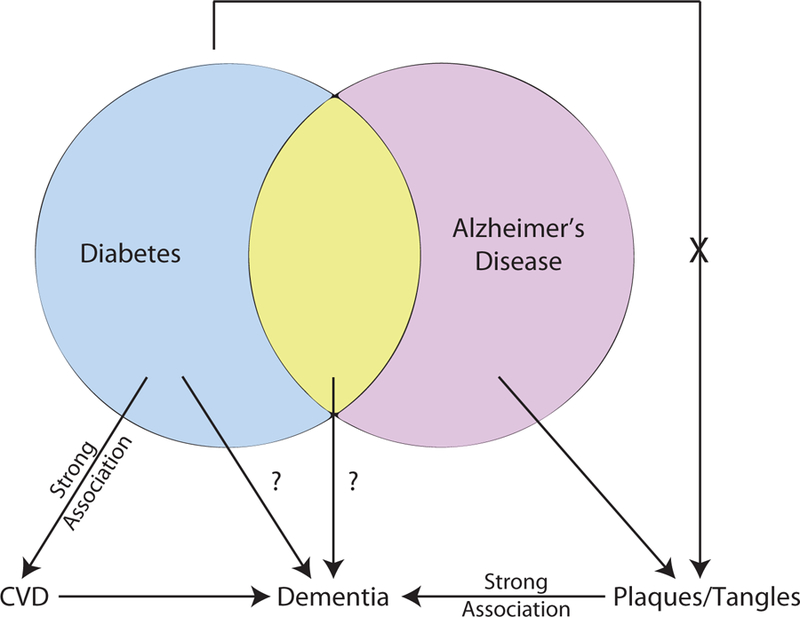

Cognitive dysfunction is a relatively poorly understood complication of T2DM; see Figure 1. Multiple epidemiological studies link T2DM to cognitive decline and clinically diagnosed AD (28,38,41,146,187,195,208), however not all studies demonstrate this association (see below). While there may be an association between T2DM, cognitive decline, and AD-type dementia, most of these studies lack correlation with neuropathology, i.e. autopsy confirmation. A 2013 systemic review and meta-analysis evaluated published studies to better delineate the relationship between T2DM and AD (190). The meta-analysis identified 15 studies conducted between the years of 1998 – 2012. Nine studies found a statistically significant correlation between T2DM and AD with risk estimates ranging from 0.83 – 2.45. Five of these studies evaluated the interaction between T2DM and Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele (APOE ε4), and three of these five studies demonstrated significant association with odds ranging from 2.4 – 4.99. While there is a reported epidemiological risk association between T2DM and clinical AD, Vagelatos and Eslick stated this association has a major confounder – cerebral infarcts (190). They found that infarcts are more common in patients with T2DM and was associated with the development of clinical AD. Based on neuropathological examination, the authors concluded: 1) cerebral infarcts are more common in T2DM than AD neuropathology; 2) Patients with clinical dementia have both infarcts and AD-type neuropathology on post mortem exam; 3) Cerebral infarcts reduce the number of AD-type lesions needed to cause clinical dementia but do not necessarily interact synergistically with AD-type pathology. Additionally, a recent review evaluated the association between T2DM and clinical AD diagnoses, and highlighted the complexity of the related scientific literature (100). The authors examined studies since 2015 and included a total of ten articles. According to the authors, only two of ten studies found that T2DM was independently related to cognitive decline in AD dementia.

Figure 1. Relationship Between T2DM and AD and Cognitive Decline.

Diabetes, specifically T2DM, has a strong association with CVD that causes dementia through generation of subcortical and cortical infarcts. T2DM has been linked with dementia and AD however the mechanism(s) are uncertain. Amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles have a strong association with cognitive status and to date, T2DM has not been associated with increased levels of plaques and tangles. T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; AD, Alzheimer’s Disease.

From a neuropathological standpoint, T2DM cognitive decline is not associated with AD lesions

The large majority of autopsy (neuropathologic) studies report no association between T2DM and amyloid plaques or NFTs (3,11,14,36,73,82,114,115,127,141,176). A recent multi-center study evaluated 2365 autopsied patients with >1300 patients having available cognitive data (2). The authors concluded that T2DM status is associated with altered likelihood of being diagnosed during life with clinical “Probable AD”; yet, at autopsy, there was no association between T2DM and AD pathology. The authors utilized logistic regression modeling to evaluate the association between diabetes, CVD pathology, Braak NFT stage, and neuritic amyloid plaque score. The presence of T2EM was associated with increased odds of brain infarcts (OR = 1.57), specifically lacunae (OR=1.71). T2DM with infarcts was associated with lower cognitive scores at end of life relative to T2DM without infarcts. Studies that have arrived at the conclusion that T2DM is associated with AD pathological hallmarks are few in number and characterized by subgrouping to determine a “positive” association. Overall, in dozens of papers, the null hypothesis – T2DM is not associated with AD-type pathology – has been tested repeatedly, and has been strongly supported.

Cerebrovascular disease contributes to cognitive decline in T2DM

T2DM is a known risk factor for CVD (87) – T2DM is associated with acute cerebral infarcts and increased stroke/brain infarction risk (50,77). Many clinical-radiological studies report that cerebral infarcts are significantly associated with increased odds of developing dementia (45,189,193). This association may help account for the reported epidemiological association between T2DM and dementia (181).

Multiple mechanisms underlie CVD in T2DM. In terms of large-vessel pathologies, vascular complications of T2DM are mediated at least partly through chronic hyperglycemia and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that apparently damage the vessel endothelium, and lead to atherosclerosis. Insult to vascular endothelium activates thrombotic cascades and recruits T-cells, macrophages, and mononuclear leukocytes impairing vascular integrity (210). From autopsy studies, T2DM is associated with cortical and subcortical atherosclerosis, and intracranial vascular stenosis is more common in those with T2DM than those without (9,91,116). Therefore, it is likely that T2DM association with cognitive decline is partly mediated through accelerated atherosclerosis in large blood vessels.

While microinfarcts are invisible to most radiological and gross examination techniques (by definition), they are well described in neuropathological literature and are often detected during post-mortem microscopic examination. The location of microinfarcts (i.e. cortical vs subcortical) correlates with disease subtypes. Cortical microinfarcts have been associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), subcortical microinfarcts with hypertensive encephalopathy, and periventricular microinfarcts with normal-pressure hydrocephalus (4,7,44). Microinfarcts are often located in subcortical areas in diabetics, however cortical infarcts and lacunes have also been described (2,11,147,176). T2DM-associated microinfarcts often coexist with AD neuropathological changes, however the number of microinfarcts is not necessarily related to the severity of AD neuropathology (10,130,165). The typical reported microinfarct size is 0.2 mm, however they range from 0.2 – 2.9 mm (10,137). Several prospective cohort autopsy-based studies evaluated the associative effect(s) of microinfarcts on cognition (10,20,66,67,121,130,165,177,180,189,201). According to these studies, microinfarcts are present in 18% - 40% of persons, while four studies found that the prevalence of microinfarcts was higher in those with dementia compared to those without dementia (10,165,177,180). These studies concluded that microinfarcts are independent predictors of dementia.

2. Classic hallmarks of AD: correlation with cognitive status and the question of “upstream” factors

Before focusing in on the possible overlapping pathogenetic mechanisms of AD and T2DM, an important concept to address is the AD-specific lesions themselves - β-amyloid plaques and NFTs. There has been some controversy about whether β-amyloid and NFTs are deleterious, whether they should be considered “disease-defining”, and/or whether these lesions are specifically associated with cognitive impairment (26,126,173,175). Numerous factors have contributed to this confusion, including the strong influence of impactful “mixed” and non-AD pathologies, some of which (e.g., TDP-43 pathology) were only relatively recently discovered (129), and others of which (e.g. small vessel pathologies) have only recently been appreciated to have strong association with cognitive impairment independent of other brain lesions (80,84,103). There also are notable biases in terms of the research volunteers that are drawn from dementia clinics (125,164), and limitations associated with studying elderly individuals without very well worked up antemortem cognitive status. Furthermore, the dichotomous approach of “dementia yes/no” (and even the corresponding dichotomous assessment of pathologies) is prone to bias as the results are dependent on the application of imperfect and arbitrary diagnostic thresholds. Over the past several decades, new research contributions have come from large community-based autopsy series with a new standard of cognitive assessments and longitudinal follow-up; from biomarker (neuroimaging and body fluid) studies in clinical series; and, from genetic studies with large sample sizes and carefully assessed phenotypes. These approaches have led to an improved appreciation of, and insights into, the heterogeneity and complexity of what occurs in the aged human brain. The direct “toxicity” of β-amyloid and NFTs still remains to be definitively proven, and autopsy evaluation is intrinsically cross-sectional. However, to summarize recent studies: an evolving scientific literature has provided strong support for the hypothesis that β-amyloid and NFTs are a part of a devastating organic disease within the complex milieu of the aged human brain, with strong adverse impact on brain function (126). For these reasons, these classic hallmarks still constitute the ‘gold standard’ for disease instantiation and severity.

Even if one accepts the concept that β-amyloid and NFTs “define” AD, there remain critically important questions: what occurs upstream of plaques and tangles? Can a person have the AD disease/”phenotype”, even before the pathologies are present? Are there common, clinically impactful features of AD that are parallel and separate from plaques and tangles? These questions get to the critical issues of causative “upstream” factors. Clearly, there is a strong genetic component to AD risk, involving the APOE gene and others genes (163), but the exact genotype/phenotype mechanisms are still incompletely understood. To date, the association(s) between specific environmental factors and AD risk are even more controversial. Developing study designs to address those uncertainties in human studies is challenging because any influence that negatively impacts cognition increases the chance of diagnosis of AD-type dementia, whether or not AD pathologies are the factors that underlie the symptoms. Here, we attempt to explore how the upstream biochemical pathways that contribute to AD-type dementia may overlap with T2DM, with the important caveat that classical AD pathologic hallmarks may be irrelevant to some of these pathways.

3. Glucose and Metabolic dysregulation in AD

While there is a wealth of information about AD pathophysiology, the initial events upstream of NFT formation and β-amyloid deposition are still unclear. Metabolic dysregulation has shown to be a possible contributory factor for AD neuropathology. Alterations in cerebral glucose metabolism, mitochondrial function, and lipid metabolism may be upstream triggers for NFT and β-amyloid deposition. The next section will focus on these topics and describe the links between metabolism and AD.

AD and glucose metabolism

Changes on flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) imaging may potentially detect glucose metabolism abnormalities, and/or synapse loss, in patients at risk of AD before symptom onset. This modality has demonstrated that cerebral glucose metabolism is affected early in the adult life of persons at genetic risk for developing AD. While the exact mechanism by which glucose metabolism is altered in AD is currently unknown, deficits in brain glucose metabolism begin decades before clinical onset of symptoms and –perhaps more importantly – even before the age where abundant plaques and tangles are observed (6,155,160,162).

There has been some controversy about whether the decline in cerebral glucose metabolism as demonstrated by PET studies were real – the effects may be attenuated by partial volume correction (79,206). Knopman et al. addressed this concern by increasing the power of their study and utilizing a larger patient cohort. His group found that there was a modest age-related reduction in cerebral glucose metabolism, and the presence of at least one APOE ε4 allele was associated with lower glucose metabolism measured in the posterior cingulate, precuneus, and/or lateral parietal regions (93). These results are similar to those found by Reiman et al. as indicated above (156).

Complementing the studies of preclinical disease, PET studies consistently demonstrate that patients with AD-type dementia have substantially reduced rates of cerebral glucose metabolism in posterior cingulate, parietal, temporal, and prefrontal cortices (117–119,174). This phenomenon was demonstrated in studies conducted by Herholz et al. and Loessner et al. and was later confirmed by others (74,131,155,156). Additional studies found that levels of glucose transporters in brain microvessels, frontal cortex, hippocampus, caudate nucleus, parietal, and temporal lobes were reduced in AD patients when compared with controls on autopsy studies (85,170). A recent study using the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging autopsy cohort provided further evidence supporting the hypothesis that glucose metabolism is affected early in AD (6). The authors found that higher brain tissue glucose concentrations (neural insulin resistance) and lower GLUT3 levels were associated with severity of AD neuropathology and AD clinical presentation. From these studies, the possibility emerges that glucose dysmetabolism is somehow correlated with AD-type pathologies per se, either as a causative factor or otherwise as part of the syndrome.

Mitochondrial dysregulation in AD

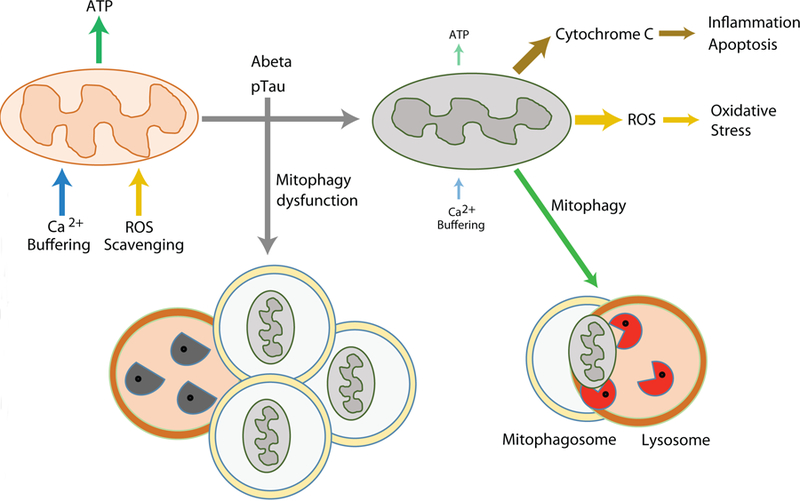

Alterations of mitochondria in AD were reported as early as the 1960s (58); See Figure 2. Subsequently, studies have reported that mitochondrial structure was altered, oxygen consumption reduced, and mitochondrial-localized enzyme activities were affected in AD (57,59,63,83,143,202). Furthermore, mitochondrial mass, size, and copy number were shown to be reduced in AD brains, and this was linked to mitochondrial interaction with β-amyloid peptide deposits (13,46). Cardoso et al. demonstrated that ρ0 cells were protected from β-amyloid peptide exposure, supporting the hypothesis that β-amyloid peptide is detrimental to mitochondrial function (25). Others have shown that β-amyloid peptide is capable of interacting with β-amyloid peptide-binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) and cyclophillin D (48,108). Interactions of β-amyloid peptide with ABAD deforms the enzyme and prevents its interaction with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD). When β-amyloid peptide interacts with cyclophilin D, this causes increased mitochondrial membrane permeability. The detrimental effects of β-amyloid peptide on the mitochondria may cause a compensatory response by increasing mitochondrial fission. The actions of mitochondrial-shaping proteins (OPA1, MFN1, MFN2, DRP1, FIS1) play a vital role in shaping and modifying mitochondrial structure during fusion and fission (211). Specifically, mediators of mitochondrial fusion (OPA1, MNF1, and MFN2) were reduced in degenerating neurons and mediators of mitochondrial fission (FIS1, DRP1) were increased (111,196–198). While these studies are important for elucidating the effect of β-amyloid peptide on mitochondrial metabolism and dynamics, they do not necessarily imply a reciprocal effect -- they do not prove that mitochondrial dysfunction promotes β-amyloid peptide deposition.

Figure 2. Mitochondrial autophagy in AD.

Mitochondrial dysfunction could play key roles in AD pathogenesis. Damaged mitochondria not only compromise the production of cellular energy and lose the capacity for Ca2+ buffering, they also release harmful ROS and cytochrome C resulted in activation of destructive pathways. Mitophagy is a mechanism for removing aged or damaged mitochondria, however, this mechanism is impaired in AD. Functionally defective mitochondria and insufficient clearance of the damaged organelles and macromolecules may synergistically intensify the detrimental pathways of AD. ATP, adenosine triphosphosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

The potential for mitochondrial metabolism to affect β-amyloid peptide production was demonstrated when cultured SH-SY5Y cell lines expressed AD- and wt-mtDNA (88). These AD-mtDNA “cybrid” cell preparations generated increased intracellular and extracellular levels of β-amyloid peptide relative to controls. This result suggests that AD-mtDNA causes functional changes not caused by wt-mtDNA, which may potentiate Aβ plaque formation. Additionally, another study found that when COS cells undergo glucose deprivation, levels of α-secretase-derived APP product increase (62). This alteration is perhaps relevant because AD patients have reduced rates of cerebral glucose metabolism in posterior cingulate, parietal, temporal, and prefrontal cortices (117–119,174) as stated above. These data may indicate how reduced glucose metabolism is linked to AD phenotype though dysregulation of mitochondria, which, as indicated in the prior paragraph, may be a self-propagating cycle with increasing β-amyloid peptide production and worsening mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mitochondrial autophagy in AD

Both neurodegeneration and diabetes are associated with oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions in the CNS that may be mediated partly by mitochondria dysfunction. Dysfunctional mitochondria may be compromised in the production of cellular energy and lose the capacity for buffering intracellular Ca2+, and they also can release harmful ROS. Uncontrolled oxidative stress triggers the discharge of cytochrome C and activates the pro-death apoptotic cascade (120). Increased oxidative stress also results from an imbalance in production of ROS and cells’ ROS scavenging systems from defective mitochondria. The inhibition of the clearance of damaged mitochondria, accompanied by the concurrent oxidative stress and inflammatory condition, may synergistically affect the health of neurons in AD and other conditions.

In healthy cells, mitochondria are turned over – damaged mitochondria are selectively identified, ubiquitinated, and degraded via an autophagy pathway termed “mitophagy”. This pathway is particularly important in long-lived (post-mitotic) cells such as neurons. Mitophagy selectively sequesters abnormal mitochondria to form autophagosomes and subsequently deliver the cargo to lysosomes for degradation. Mitophagy plays a key role in mitochondrial quality control and is an essential mechanism in tissue maintenance and cellular homeostasis, and the literature that pertains to autophagic dysregulation in AD may also be germane to mitophagy. Dysregulation of autophagy has been associated with AD pathogenesis. Nixon et al. reported the accumulation of immature autophagic vacuoles (AVs) in dystrophic neurites of AD brains (134). Later reports conflicted on how autophagy flux was affected in AD and what specific stages were dysregulated in human brains (135). Recently, Bordi et al. assessed the autophagy pathways and autophagy flux by performing microarray and immunochemical analyses of hippocampal CA1 neurons in postmortem tissue samples from AD subjects at different stages of disease (19). This study revealed that autophagy is upregulated and lysosomal biogenesis is increased in the early stage of AD (~10 years before clinical AD diagnosis). Additionally, autophagic flux was obstructed due to the impairment in the clearance of autophagic substrates. These studies indicate that the regulation of mitophagy plays important roles in mitochondrial homeostasis, however, how those molecular pathways interact with β-amyloid and pTau remains mostly unknown.

Lipid metabolism dysfunction in AD

Lipid dysmetabolism is a component of the metabolic syndrome that occurs in many T2D patients, and multiple lines of evidence have implicated perturbations in lipid biochemistry in AD. The brain is one of the most lipid-enriched organs and is partly composed of a variety of lipids such as glycerophospholipids (GPs), sphingolipids, and cholesterol (18). The involvement of lipid metabolism in the pathogenesis of AD was suspected when brains of AD patients were examined post-mortem and found to contain “adipose inclusions” or “lipid granules” (54). Alois Alzheimer originally described this finding during his milestone study examining the brain of Auguste Deter (5).

After the discovery that APOE ε4 allele is the strongest genetic risk factor for late onset AD, interest in lipid metabolism gained added momentum (16,33). One copy of the APOE ε4 allele increases the risk of developing AD by 2–3 fold, but two copies of APOE ε4 alleles increase the risk to ~12-fold (15,158). The APOE protein regulates cholesterol metabolism and mediates uptake of lipoprotein particles via low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor related protein (LRP) (23). The APOE ε4 isoform at least somewhat selectively binds β-amyloid peptide, modulating its aggregation and clearance (23). The APOE ε4 allele is associated with higher cholesterol levels compared to APOE ε2 allele (53,105).

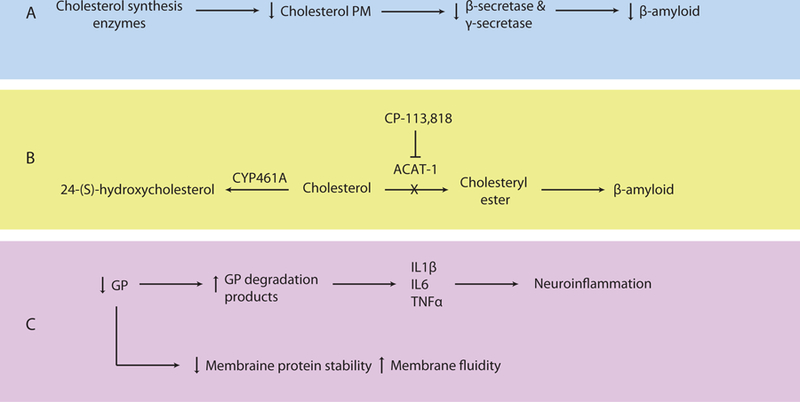

Studies demonstrated that cholesterol modulates β-amyloid peptide levels by affecting secretase function (106). Additionally, the involvement of cholesterol has been implicated in pathogenesis of AD in epidemiological studies (23,90). When membrane cholesterol levels are decreased, the activities of β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase are reduced, leading to lower β-amyloid production (52,169,194,207) (Figure 3A). In addition, the inhibition of cholesterol synthesis enzymes (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA-reductase and 7-dehydro-cholesterol-reductase) is able to reduce intracellular and extracellular β-amyloid levels (52,153,169).

Figure 3. Lipid Metabolism Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease.

A. Inhibition of cholesterol synthesis enzymes decreases plasma membrane cholesterol levels, β-secretase and γ-secretase activities, and β-amyloid production. B. Cholesterol can be converted to 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol or cholesteryl ester by CYP461A or ACAT-1, respectively. Increased ACAT-1 activity causes production of cholesteryl esters and increased β-amyloid levels. Inhibition of ACAT-1 by CP-113,818 reduces β-amyloid. C. Glycerophospholipids (GP) stabilize plasma membrane proteins such as ion channels and affect plasma membrane fluidity. Lower levels of GP are found in AD as evidenced by increased levels of GP degradation products, which are proinflammatory. Recruited astrocytes and microglia release IL1β, IL6, and TNFα and cause subsequent neuroinflammation. CYP461A, 24-hydroxylase; ACAT-1, sterol O-acyltransferase 1; GP glycerophospholipids; AD, Alzheimer’s Disease; IL1β, interleukin-1β; IL6, interleukin-6; TNFα tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Under normal conditions, free intracellular cholesterol is esterified to form cholesteryl-esters by sterol O-acyltransferase 1 (ACAT1) (Figure 3B). In cultured cells, it was demonstrated that when cholesteryl ester concentration was increased, there was a proportional rise in β-amyloid levels (148). When ACAT1 activity was inhibited, there was a significant reduction in β-amyloid peptide (78). Genetic deletion of ACAT1 has been shown to reduce β-amyloid peptide and cognitive impairment in AD mouse models, supporting its role in AD pathology (22). In addition to formation of cholesteryl-esters by ACAT1, cholesterol can be metabolized by the brain-specific enzyme, 24-hydroxylase (CYP46A1), into 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol (cerebrosterol) that can cross the blood brain barrier (22). When ACAT1 activity is reduced (either genetically deleted or antagonized by using a small molecular inhibitor), levels of 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol are increased and β-amyloid pathology in the brain is decreased (22). Studies have found that persons with early stage AD have higher levels of 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol in peripheral circulation and CSF relative to normal controls (94,109). This increase in 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol suggests that cholesterol metabolism is affected early in AD and 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol is produced as a byproduct or as part of a compensatory mechanism. Furthermore, peripheral levels of 24-(S)-hydroxycholesterol could be used as a blood biomarker for detection of early AD (89,109). Collectively, these studies suggest that the balance between free cholesterol and cholesterylesters can alter amyloidogenesis in AD.

Lipids other than cholesterol – GPs and sphingolipids – have been implicated in AD pathogenesis. Normally, GPs interact and bind to membrane proteins and ion channels, helping them maintain correct position in the plasma membrane (140) (Figure 3C). When GPs are reduced in cell plasma membranes, the membranes become more fluid and permeable (75). Interestingly, lower levels of GPs have been reported in AD (70,144). Further, higher levels of GP degradation products were found in the brains of AD patients (122). GP degradation products are pro-inflammatory, and may act as signals to activate astrocytes and microglia(51). This leads to additional release of interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and TNFα, producing a cascade of additional neuroinflammation (70,144), which can result in local tissue damage and neuron cell death.

Sphingolipids make up the largest structural lipid component of CNS membranes and are highly expressed in the myelin sheath. There are different subtypes of sphinolipids, for example ceramides are the simplest, while sphingomyelins and glycosphingolipids (e.g., cerebrosides, sulfatides, and gangliosides) are more complex (107). Sulfatides play important roles in the nervous system and are abundant in the myelin sheath and in oligodendrocytes (183). In AD brains, sulfatide levels are reduced and when sulfatides are degraded, ceramide byproducts are formed (71). Sulfatides were shown to be depleted up to 93% in gray matter and up to 58% in white matter of AD brains, while other major classes of lipids were not affected (71). Also, ceramide levels were increased more than three fold in AD brains (37,71,72). Low levels of sulfatides are specific for AD and do not occur in patients with Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, or multiple sclerosis (30,107). The exact mechanism for sulfatide deficiency or how the loss of sulfatides contributes to AD neuropathology is currently unknown; however, it has been suggested that it is unlikely to be mediated directly by β-amyloid peptide accumulation (30). A later study by the same group was inconclusive in elucidating a mechanism of sulfatide deficiency in AD (29); however, they proposed several explanations for the relationship between sulfatides and AD pathology. It was suggested that APOE mediates sulfatide depletion, sulfatides enhance β-amyloid binding to APOE, and sulfatides enhance uptake of β-amyloid peptides into the cell, leading to abnormal β-amyloid accumulation in lysosomes (69). We conclude from the prior literature on lipid neurochemistry in AD that the findings are complex and, as far as we know, the various experimental “story lines” have not been reconciled together nor tied directly to T2DM. However, there appears to be compelling data in support of the hypothesis that changes in lipid biochemistry occurs early in the course of AD pathogenesis.

4. T2DM-related pathways that may affect the brain

While CVD is a likely pathologic substrate of cognitive decline in T2DM, evidence exists for other mechanisms that may contribute in parallel or separately. The following section will discuss the impact of hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, inflammation, hypercorticolism, and amyloid accumulation as non-mutually exclusive mechanisms that cause or exacerbate cognitive decline in T2DM and AD.

Hyperglycemia and Cognitive Decline

The relationship between blood glucose levels and degree of cognitive dysfunction in T2DM patients has been extensively evaluated. Yaffe and colleagues studied a population of 2000 women and found that participants with HbA1c levels >7.0% had a four-fold increase in probability of developing cognitive impairment (203). Intriguingly, this study only included “non-diabetic” women. These findings again support the hypothesis that glucose dysregulation is associated with cognitive impairment. Other studies also found an inverse relationship between HbA1c and working memory, executive function, learning, and/or psychomotor performance in T2DM patients (124,142,152,159). While impaired glucose control in the context of T2DM is associated with declining cognitive function, studies have found that impaired glucose tolerance without a formal diagnosis of diabetes (“pre-diabetes”) is also a risk factor for cognitive dysfunction (36,86,96,191). Despite the strong evidence that supports the link between impaired glucose regulation with cognitive dysfunction, it is important to note that not all studies to date demonstrate this relationship (55,95,104,167).

Many of the prior studies that directly connect hyperglycemia with AD-relevant pathways were performed in animal models. The direct relevance of these studies to the human conditions (T2DM and AD) is not firmly established. In some of these studies, hyperglycemia causes tissue damage and alters cellular function through increasing polyol pathway activation, which causes the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and protein kinase C (PKC) activation (17,21,92,188). For example, treptozotocin-treated rats were found to have increased sorbitol in cranial nerves, cerebrum, and retina. When animals were subsequently treated with tolerstat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, the accumulation was reduced (178). Another study found that when sorbinil, an aldose reductase inhibitor, was given to streptozotocin-treated rats, it reduced brain levels of sorbitol and corrected cognitive dysfunction. However, more information is needed to definitively state whether this pathway contributes to cognitive decline in T2DM in humans

Another potential mechanism of cognitive decline due to hyperglycemia is the formation of AGEs and receptors for AGE (RAGEs). While there may be an association between AGEs, RAGEs, and cognitive decline in T2DM, currently there is not enough evidence to support this mechanism. While animal studies demonstrated increased RAGE expression and damage to white matter and myelin, human studies on this topic produced conflicting results (188,205). Several studies using human tissue demonstrated that patients with diabetes and AD have increased N-carboxymethyllysine (a type of AGE) staining on post-mortem analysis (64). However, another study failed to replicate this association (73). Little firm evidence exists for the role of PKC in relation to T2DM and cognitive decline. While some animal studies have found that PKC is highly expressed and has increased activity in diabetic animal models, other studies did not support this data (151,168).

Some animal studies have elucidated molecular changes that occur in hippocampal neurons in response to hyperglycemia. For example, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, the NMDA currents and NMDA protein levels were reduced in the hippocampus (60). Furthermore, CA3 neurons underwent remodeling in response to hyperglycemia. This remodeling includes apical dendrite retraction and simplification. There is also an associated decrease in presynaptic vesicles (110). Another study using the streptozotocin-induced diabetic model found evidence of apoptosis in hippocampal neurons. Cognitive deficits were associated with DNA fragmentation, positive TUNEL staining, and increased caspase-3 levels (101).

Insulin resistance, inflammation, hypercorticolism, and amyloid accumulation

There is a growing body of evidence linking IR, a component of T2DM, to the pathogenesis of AD (39,40,128). Several studies have reported that the incidence of clinically diagnosed AD is 1.2–1.7-fold greater in patients with T2DM and IR (35,36,96,99,139,141,203). Also, IR is reported to occur more frequently in patients with AD (82). IR has been found to impair central cholinergic activity, and diabetic animal models have reduced production and release of acetylcholine (ACh) (199,200). Remarkably, the administration of intranasal insulin rescued memory deficits in a subset of research volunteers with clinical AD (8,34,136,154).

Exactly how IR exerts its effects on cognitive function is not clear. However, several mechanisms have been proposed to help explain how IR contributes to cognitive decline in T2DM. The first mechanism is based on inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 that are increased in T2DM and metabolic syndrome and are associated with reduced cognitive function (27,42). Further, inflammatory reactants and proinflammatory cytokines have been found in CSF and β-amyloid plaques (49,68,81). A study conducted by Singh-Manoux et al. evaluated IL-6 and CRP in 5,217 people and found that elevated IL-6 in midlife can predict subsequent cognitive decline (171). The authors concluded that pro-inflammatory molecules can influence cognition by inducing a prothrombic state. For example, inflammatory signals can trigger local thrombotic vascular events leading to brain infarction. Other studies have also demonstrated that persons with metabolic syndrome and elevated inflammatory markers have impaired cognitive function (112,203).

Another hypothesized mechanism by which IR could contribute to cognitive impairment in T2DM involves dysregulation of the HPA axis, leading to higher cortisol levels. Humans and animals with T2DM have increased serum cortisol levels (98,157,186) and several studies found that high serum cortisol is associated with cognitive decline and dementia, an effect independent of APOE genotype. There is experimental evidence supporting the detrimental effects of cortisol on cognitive performance (43,132,133). For instance, healthy individuals treated with dexamethasone, corticosterone, or hydrocortisone performed worse on memory tests, and, additionally, patients with active Cushing’s disease (and thus high blood cortisol levels) also demonstrate decreased performance on working memory, reasoning, and attention tests relative to controls (56,150,184). However, not all studies agree on the association between increased levels of cortisol and cognitive impairment (31,97,166).

The third mechanism for IR in cognitive dysfunction involves an indirect contribution of IR to formation of β-amyloid plaques found in AD. It is known that β-amyloid peptide is produced from the cleavage of APP via β- and γ-secretase (65,172). Afterwards, the β-amyloid protein may be degraded by insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) (61,145,192). IDE is a zinc-binding protease that cleaves short polypeptides that vary considerably in sequence. IDE is responsible for degradation of insulin, glucagon, atrial natriuretic peptide, and β-amyloid peptide (71). Studies have shown that insulin affects metabolism of APP and β-amyloid by IDE (209). In rat hippocampal neurons, the administration of insulin upregulates IDE, leading, in turn, to increased β-amyloid clearance. Furthermore, in mice, IR leads to increased brain amyloidosis through an increase in γ-secretase activity, as well as decreased IDE (76,123,179). Patients with APOE ε4 were found to have a 50% reduction in hippocampal IDE levels when compared to persons lacking the APOE ε4 allele, suggesting that the β-amyloid peptide is not cleared appropriately in carriers of APOE ε4. Furthermore, hippocampal IDE mRNA levels were also reduced in AD patients with the APOE ε4 allele relative to controls (32). Thus, expression of IDE is associated with AD, and IR can lead to attenuated IDE levels, resulting in a decrease in β-amyloid clearance. If IR leads to increased β-amyloid peptide accumulation, this change can trigger a host of detrimental effects. Immunostaining has previously shown that β-amyloid peptide aggregates co-localizes with AGEs and RAGEs in astrocytes (161). Furthermore, β-amyloid peptide can bind to RAGEs and induce microglial and neuronal dysfunction, local inflammation, and oxidative stress (47,102,204). As such, IR is a component of T2DM that can lead to reduced IDE activity, promoting β-amyloid peptide accumulation, and subsequent local inflammation that may result in cognitive decline.

Conclusion

T2DM is a risk factor for cognitive decline, although the exact mechanism(s) mediating this relationship are unclear. Multiple studies have found that CVD is more common in patients with T2DM than in non-diabetics. CVD may comprise a combination of macroscopic and microscopic vascular lesions that contribute to cognitive impairment by impairing blood flow.

Alterations in glucose metabolism, mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction, mitochondrial autophagy, and alterations in lipid metabolism are all additional potential contributing factors to cognitive decline in T2DM. The mechanisms and processes that are occurring in aged brains still remain imperfectly characterized, and may involve the polyol pathway, formation of AGEs, PKC activation, IR, inflammation, and dysregulation of HPA axis.

Upstream events responsible for eventual β-amyloid peptide deposition and NFT formation are also still not well understood. However, recent literature has found that metabolic dysregulation is linked with AD orsl. Abnormalities in cerebral glucose metabolism, mitochondrial function, and lipid metabolism are shown to exist in persons at risk for developing AD pathology. Deeper understanding of how metabolic perturbations contribute to AD-type pathology can shed light on new treatments.

References

- (1).Dementia Fact sheet N°362 World Health Organization March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Abner EL, Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA, Fardo DW, Woltjer RL, et al. Diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular but not Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement 2016. August;12(8):882–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ahtiluoto S, Polvikoski T, Peltonen M, Solomon A, Tuomilehto J, Winblad B, et al. Diabetes, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia: a population-based neuropathologic study. Neurology 2010. September 28;75(13):1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Akai K, Uchigasaki S, Tanaka U, Komatsu A. Normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neuropathological study. Acta Pathol Jpn 1987. January;37(1):97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Alzheimer A, Stelzmann RA, Schnitzlein HN, Murtagh FR. An English translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde”. Clin Anat 1995;8(6):429–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).An Y, Varma VR, Varma S, Casanova R, Dammer E, Pletnikova O, et al. Evidence for brain glucose dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018. March;14(3):318–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Arboix A, Ferrer I, Marti-Vilalta JL. Clinico-anatomopathologic analysis of 25 patients with lacunar infarction. Rev Clin Esp 1996. June;196(6):370–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Arnold SE, Arvanitakis Z, Macauley-Rambach SL, Koenig AM, Wang HY, Ahima RS, et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol 2018. March;14(3):168–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Buchman AS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. The Relationship of Cerebral Vessel Pathology to Brain Microinfarcts. Brain Pathol 2017. January;27(1):77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct pathology, dementia, and cognitive systems. Stroke 2011. March;42(3):722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Arvanitakis Z, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Li Y, Arnold SE, Wang Z, et al. Diabetes is related to cerebral infarction but not to AD pathology in older persons. Neurology 2006. December 12;67(11):1960–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2011. March 19;377(9770):1019–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Baloyannis SJ. Mitochondrial alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2006. July;9(2):119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Beeri MS, Silverman JM, Davis KL, Marin D, Grossman HZ, Schmeidler J, et al. Type 2 diabetes is negatively associated with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005. April;60(4):471–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet 2007. January;39(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bertram L, Tanzi RE. Thirty years of Alzheimer’s disease genetics: the implications of systematic meta-analyses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008. October;9(10):768–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Biessels GJ, van der Heide LP, Kamal A, Bleys RL, Gispen WH. Ageing and diabetes: implications for brain function. Eur J Pharmacol 2002. April 19;441(1–2):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bjorkhem I, Meaney S. Brain cholesterol: long secret life behind a barrier. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004. May;24(5):806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bordi M, Berg MJ, Mohan PS, Peterhoff CM, Alldred MJ, Che S, et al. Autophagy flux in CA1 neurons of Alzheimer hippocampus: Increased induction overburdens failing lysosomes to propel neuritic dystrophy. Autophagy 2016. December;12(12):2467–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Brayne C, Richardson K, Matthews FE, Fleming J, Hunter S, Xuereb JH, et al. Neuropathological correlates of dementia in over-80-year-old brain donors from the population-based Cambridge city over-75s cohort (CC75C) study. J Alzheimers Dis 2009;18(3):645–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Brownlee M The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005. June;54(6):1615–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bryleva EY, Rogers MA, Chang CC, Buen F, Harris BT, Rousselet E, et al. ACAT1 gene ablation increases 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol content in the brain and ameliorates amyloid pathology in mice with AD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010. February 16;107(7):3081–3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bu G Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009. May;10(5):333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Burns A, Iliffe S. Alzheimer’s disease. BMJ 2009. February 5;338:b158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cardoso SM, Santos S, Swerdlow RH, Oliveira CR. Functional mitochondria are required for amyloid beta-mediated neurotoxicity. FASEB J 2001. June;15(8):1439–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Castellani RJ, Perry G. The complexities of the pathology-pathogenesis relationship in Alzheimer disease. Biochem Pharmacol 2014. April 15;88(4):671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Chen J, Wildman RP, Hamm LL, Muntner P, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, et al. Association between inflammation and insulin resistance in U.S. nondiabetic adults: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care 2004. December;27(12):2960–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Cheng G, Huang C, Deng H, Wang H. Diabetes as a risk factor for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Intern Med J 2012. May;42(5):484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Cheng H, Wang M, Li JL, Cairns NJ, Han X. Specific changes of sulfatide levels in individuals with pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease: an early event in disease pathogenesis. J Neurochem 2013. December;127(6):733–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Cheng H, Xu J, McKeel DW Jr, Han X. Specificity and potential mechanism of sulfatide deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease: an electrospray ionization mass spectrometric study. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2003. July;49(5):809–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Comijs HC, Gerritsen L, Penninx BW, Bremmer MA, Deeg DJ, Geerlings MI. The association between serum cortisol and cognitive decline in older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010. January;18(1):42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Cook DG, Leverenz JB, McMillan PJ, Kulstad JJ, Ericksen S, Roth RA, et al. Reduced hippocampal insulin-degrading enzyme in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is associated with the apolipoprotein E-epsilon4 allele. Am J Pathol 2003. January;162(1):313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993. August 13;261(5123):921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Craft S, Claxton A, Baker LD, Hanson AJ, Cholerton B, Trittschuh EH, et al. Effects of Regular and Long-Acting Insulin on Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers: A Pilot Clinical Trial. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;57(4):1325–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Cukierman T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes-- systematic overview of prospective observational studies. Diabetologia 2005. December;48(12):2460–2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Curb JD, Rodriguez BL, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Masaki KH, et al. Longitudinal association of vascular and Alzheimer’s dementias, diabetes, and glucose tolerance. Neurology 1999. March 23;52(5):971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Cutler RG, Kelly J, Storie K, Pedersen WA, Tammara A, Hatanpaa K, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004. February 17;101(7):2070–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).de la Monte SM. Relationships between diabetes and cognitive impairment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2014. March;43(1):245–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).de la Monte SM. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease. BMB Rep 2009. August 31;42(8):475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).de la Monte SM, Longato L, Tong M, Wands JR. Insulin resistance and neurodegeneration: roles of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2009. October;10(10):1049–1060. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).de la Monte SM, Tong M, Wands JR. The 20-Year Voyage Aboard the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: Docking at ‘Type 3 Diabetes’, Environmental/Exposure Factors, Pathogenic Mechanisms, and Potential Treatments. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;62(3):1381–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).de Luca C, Olefsky JM. Inflammation and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett 2008. January 9;582(1):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).de Quervain DJ, Roozendaal B, Nitsch RM, McGaugh JL, Hock C. Acute cortisone administration impairs retrieval of long-term declarative memory in humans. Nat Neurosci 2000. April;3(4):313–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Leys D, Maurage CA, Pasquier F. The impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy on the occurrence of cerebrovascular lesions in demented patients with Alzheimer features: a neuropathological study. Eur J Neurol 2011. June;18(6):913–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010. July 26;341:c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Diana A, Simic G, Sinforiani E, Orru N, Pichiri G, Bono G. Mitochondria morphology and DNA content upon sublethal exposure to beta-amyloid(1–42) peptide. Coll Antropol 2008. January;32 Suppl 1:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Doens D, Fernandez PL. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid beta for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation 2014. March 13;11:48–2094-11–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Du H, Guo L, Fang F, Chen D, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, et al. Cyclophilin D deficiency attenuates mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation and ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 2008. October;14(10):1097–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Duong T, Nikolaeva M, Acton PJ. C-reactive protein-like immunoreactivity in the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 1997. February 21;749(1):152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Ergul A, Kelly-Cobbs A, Abdalla M, Fagan SC. Cerebrovascular complications of diabetes: focus on stroke. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2012. June;12(2):148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Farooqui T. Modulation of inflammation in brain: a matter of fat. J Neurochem 2007. May;101(3):577–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, Stroick M, Lutjohann D, Keller P, et al. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer’s disease beta -amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001. May 8;98(10):5856–5861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, Harris T, Corti MC, Hyman BT, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 2 allele and risk of stroke in the older population. Stroke 1997. December;28(12):2410–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Foley P Lipids in Alzheimer’s disease: A century-old story. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010. August;1801(8):750–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Fontbonne A, Berr C, Ducimetiere P, Alperovitch A. Changes in cognitive abilities over a 4-year period are unfavorably affected in elderly diabetic subjects: results of the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. Diabetes Care 2001. February;24(2):366–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Forget H, Lacroix A, Somma M, Cohen H. Cognitive decline in patients with Cushing’s syndrome. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2000. January;6(1):20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Frackowiak RS, Pozzilli C, Legg NJ, Du Boulay GH, Marshall J, Lenzi GL, et al. Regional cerebral oxygen supply and utilization in dementia. A clinical and physiological study with oxygen-15 and positron tomography. Brain 1981. December;104(Pt 4):753–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Friede RL. Enzyme histochemical studies of senile plaques. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1965;24:477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Fukuyama H, Ogawa M, Yamauchi H, Yamaguchi S, Kimura J, Yonekura Y, et al. Altered cerebral energy metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease: a PET study. J Nucl Med 1994. January;35(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Gardoni F, Kamal A, Bellone C, Biessels GJ, Ramakers GM, Cattabeni F, et al. Effects of streptozotocin-diabetes on the hippocampal NMDA receptor complex in rats. J Neurochem 2002. February;80(3):438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Gasparini L, Gouras GK, Wang R, Gross RS, Beal MF, Greengard P, et al. Stimulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein trafficking by insulin reduces intraneuronal beta-amyloid and requires mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Neurosci 2001. April 15;21(8):2561–2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Gasparini L, Racchi M, Benussi L, Curti D, Binetti G, Bianchetti A, et al. Effect of energy shortage and oxidative stress on amyloid precursor protein metabolism in COS cells. Neurosci Lett 1997. August 8;231(2):113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Gibson GE, Sheu KF, Blass JP, Baker A, Carlson KC, Harding B, et al. Reduced activities of thiamine-dependent enzymes in the brains and peripheral tissues of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1988. August;45(8):836–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Girones X, Guimera A, Cruz-Sanchez CZ, Ortega A, Sasaki N, Makita Z, et al. N epsilon-carboxymethyllysine in brain aging, diabetes mellitus, and Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med 2004. May 15;36(10):1241–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Goedert M Neuronal localization of amyloid beta protein precursor mRNA in normal human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO J 1987. December 1;6(12):3627–3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bouras C, Kovari E. Identification of Alzheimer and vascular lesion thresholds for mixed dementia. Brain 2007. November;130(Pt 11):2830–2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Gold G, Kovari E, Herrmann FR, Canuto A, Hof PR, Michel JP, et al. Cognitive consequences of thalamic, basal ganglia, and deep white matter lacunes in brain aging and dementia. Stroke 2005. June;36(6):1184–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Gorelick PB. Role of inflammation in cognitive impairment: results of observational epidemiological studies and clinical trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010. October;1207:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Han X The pathogenic implication of abnormal interaction between apolipoprotein E isoforms, amyloid-beta peptides, and sulfatides in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 2010. June;41(2–3):97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Han X, Holtzman DM, McKeel DW Jr. Plasmalogen deficiency in early Alzheimer’s disease subjects and in animal models: molecular characterization using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Neurochem 2001. May;77(4):1168–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Han XM Holtzman D, McKeel DW Jr, Kelley J, Morris JC. Substantial sulfatide deficiency and ceramide elevation in very early Alzheimer’s disease: potential role in disease pathogenesis. J Neurochem 2002. August;82(4):809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).He X, Huang Y, Li B, Gong CX, Schuchman EH. Deregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2010. March;31(3):398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Heitner J, Dickson D. Diabetics do not have increased Alzheimer-type pathology compared with age-matched control subjects. A retrospective postmortem immunocytochemical and histofluorescent study. Neurology 1997. November;49(5):1306–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Herholz K, Salmon E, Perani D, Baron JC, Holthoff V, Frolich L, et al. Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. Neuroimage 2002. September;17(1):302–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Hishikawa D, Hashidate T, Shimizu T, Shindou H. Diversity and function of membrane glycerophospholipids generated by the remodeling pathway in mammalian cells. J Lipid Res 2014. May;55(5):799–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Ho L, Qin W, Pompl PN, Xiang Z, Wang J, Zhao Z, et al. Diet-induced insulin resistance promotes amyloidosis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J 2004. May;18(7):902–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Huang J, Zhang X, Li J, Tang L, Jiao X, Lv X. Impact of glucose fluctuation on acute cerebral infarction in type 2 diabetes. Can J Neurol Sci 2014. July;41(4):486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Hutter-Paier B, Huttunen HJ, Puglielli L, Eckman CB, Kim DY, Hofmeister A, et al. The ACAT inhibitor CP-113,818 markedly reduces amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2004. October 14;44(2):227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Ibanez V, Pietrini P, Furey ML, Alexander GE, Millet P, Bokde AL, et al. Resting state brain glucose metabolism is not reduced in normotensive healthy men during aging, after correction for brain atrophy. Brain Res Bull 2004. March 15;63(2):147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Ighodaro ET, Abner EL, Fardo DW, Lin AL, Katsumata Y, Schmitt FA, et al. Risk factors and global cognitive status related to brain arteriolosclerosis in elderly individuals. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017. January;37(1):201–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Iwamoto N, Nishiyama E, Ohwada J, Arai H. Demonstration of CRP immunoreactivity in brains of Alzheimer’s disease: immunohistochemical study using formic acid pretreatment of tissue sections. Neurosci Lett 1994. August 15;177(1–2):23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC. Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 2004. February;53(2):474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Johnson AB, Blum NR. Nucleoside phosphatase activities associated with the tangles and plaques of alzheimer’s disease: a histochemical study of natural and experimental neurofibrillary tangles. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1970. July;29(3):463–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Kalaria RN. The pathology and pathophysiology of vascular dementia. Neuropharmacology 2017. December 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Kalaria RN, Harik SI. Abnormalities of the glucose transporter at the blood-brain barrier and in brain in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Clin Biol Res 1989;317:415–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Kanaya AM, Barrett-Connor E, Gildengorin G, Yaffe K. Change in cognitive function by glucose tolerance status in older adults: a 4-year prospective study of the Rancho Bernardo study cohort. Arch Intern Med 2004. June 28;164(12):1327–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA 1979. May 11;241(19):2035–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Khan SM, Cassarino DS, Abramova NN, Keeney PM, Borland MK, Trimmer PA, et al. Alzheimer’s disease cybrids replicate beta-amyloid abnormalities through cell death pathways. Ann Neurol 2000. August;48(2):148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Khan TK, Alkon DL. Peripheral biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;44(3):729–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2009. August 13;63(3):287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Klassen AC, Loewenson RB, Resch JA. Cerebral atherosclerosis in selected chronic disease states. Atherosclerosis 1973. Sep-Oct;18(2):321–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Klein JP, Waxman SG. The brain in diabetes: molecular changes in neurons and their implications for end-organ damage. Lancet Neurol 2003. September;2(9):548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Lundt ES, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, aging, and apolipoprotein E genotype in cognitively normal persons. Neurobiol Aging 2014. September;35(9):2096–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Kolsch H, Heun R, Kerksiek A, Bergmann KV, Maier W, Lutjohann D. Altered levels of plasma 24S- and 27-hydroxycholesterol in demented patients. Neurosci Lett 2004. September 30;368(3):303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Kumari M, Marmot M. Diabetes and cognitive function in a middle-aged cohort: findings from the Whitehall II study. Neurology 2005. November 22;65(10):1597–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Kuusisto J, Koivisto K, Mykkanen L, Helkala EL, Vanhanen M, Hanninen T, et al. Association between features of the insulin resistance syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease independently of apolipoprotein E4 phenotype: cross sectional population based study. BMJ 1997. October 25;315(7115):1045–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Lara VP, Caramelli P, Teixeira AL, Barbosa MT, Carmona KC, Carvalho MG, et al. High cortisol levels are associated with cognitive impairment no-dementia (CIND) and dementia. Clin Chim Acta 2013. August 23;423:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Lee ZS, Chan JC, Yeung VT, Chow CC, Lau MS, Ko GT, et al. Plasma insulin, growth hormone, cortisol, and central obesity among young Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1999. September;22(9):1450–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Leibson CL, Rocca WA, Hanson VA, Cha R, Kokmen E, O’Brien PC, et al. Risk of dementia among persons with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 1997. February 15;145(4):301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Li J, Cesari M, Liu F, Dong B, Vellas B. Effects of Diabetes Mellitus on Cognitive Decline in Patients with Alzheimer Disease: A Systematic Review. Can J Diabetes 2017. February;41(1):114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Li ZG, Zhang W, Grunberger G, Sima AA. Hippocampal neuronal apoptosis in type 1 diabetes. Brain Res 2002. August 16;946(2):221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Liliensiek B, Weigand MA, Bierhaus A, Nicklas W, Kasper M, Hofer S, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) regulates sepsis but not the adaptive immune response. J Clin Invest 2004. June;113(11):1641–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Lim AS, Yu L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Buchman AS. Sleep Fragmentation, Cerebral Arteriolosclerosis, and Brain Infarct Pathology in Community-Dwelling Older People. Stroke 2016. February;47(2):516–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Lindeman RD, Romero LJ, LaRue A, Yau CL, Schade DS, Koehler KM, et al. A biethnic community survey of cognition in participants with type 2 diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, and normal glucose tolerance: the New Mexico Elder Health Survey. Diabetes Care 2001. September;24(9):1567–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Liu CC, Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol 2013. February;9(2):106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Liu Q, Zerbinatti CV, Zhang J, Hoe HS, Wang B, Cole SL, et al. Amyloid precursor protein regulates brain apolipoprotein E and cholesterol metabolism through lipoprotein receptor LRP1. Neuron 2007. October 4;56(1):66–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Liu Q, Zhang J. Lipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Bull 2014. April;30(2):331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, et al. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Science 2004. April 16;304(5669):448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Lutjohann D, Papassotiropoulos A, Bjorkhem I, Locatelli S, Bagli M, Oehring RD, et al. Plasma 24S-hydroxycholesterol (cerebrosterol) is increased in Alzheimer and vascular demented patients. J Lipid Res 2000. February;41(2):195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Magarinos AM, McEwen BS. Experimental diabetes in rats causes hippocampal dendritic and synaptic reorganization and increased glucocorticoid reactivity to stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000. September 26;97(20):11056–11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (111).Manczak M, Calkins MJ, Reddy PH. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and abnormal interaction of amyloid beta with mitochondrial protein Drp1 in neurons from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: implications for neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet 2011. July 1;20(13):2495–2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (112).Marioni RE, Strachan MW, Reynolds RM, Lowe GD, Mitchell RJ, Fowkes FG, et al. Association between raised inflammatory markers and cognitive decline in elderly people with type 2 diabetes: the Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study. Diabetes 2010. March;59(3):710–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (113).Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006. November;3(11):e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (114).Matioli MNPDS, Suemoto CK, Rodriguez RD, Farias DS, da Silva MM, Leite REP, et al. Association between diabetes and causes of dementia: Evidence from a clinicopathological study. Dement Neuropsychol 2017. Oct-Dec;11(4):406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (115).Matsuzaki T, Sasaki K, Tanizaki Y, Hata J, Fujimi K, Matsui Y, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with the pathology of Alzheimer disease: the Hisayama study. Neurology 2010. August 31;75(9):764–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (116).Mazighi M, Labreuche J, Gongora-Rivera F, Duyckaerts C, Hauw JJ, Amarenco P. Autopsy prevalence of intracranial atherosclerosis in patients with fatal stroke. Stroke 2008. April;39(4):1142–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (117).McGeer EG, Peppard RP, McGeer PL, Tuokko H, Crockett D, Parks R, et al. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography studies in presumed Alzheimer cases, including 13 serial scans. Can J Neurol Sci 1990. February;17(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (118).Mielke R, Pietrzyk U, Jacobs A, Fink GR, Ichimiya A, Kessler J, et al. HMPAO SPET and FDG PET in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: comparison of perfusion and metabolic pattern. Eur J Nucl Med 1994. October;21(10):1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (119).Minoshima S, Frey KA, Koeppe RA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. A diagnostic approach in Alzheimer’s disease using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine-18-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 1995. July;36(7):1238–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (120).Mishra P, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics and inheritance during cell division, development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014. October;15(10):634–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (121).Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993. November;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (122).Mulder C, Wahlund LO, Teerlink T, Blomberg M, Veerhuis R, van Kamp GJ, et al. Decreased lysophosphatidylcholine/phosphatidylcholine ratio in cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2003. August;110(8):949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (123).Mullins RJ, Diehl TC, Chia CW, Kapogiannis D. Insulin Resistance as a Link between Amyloid-Beta and Tau Pathologies in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2017. May 3;9:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (124).Munshi M, Grande L, Hayes M, Ayres D, Suhl E, Capelson R, et al. Cognitive dysfunction is associated with poor diabetes control in older adults. Diabetes Care 2006. August;29(8):1794–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (125).Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Smith CD, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol 2010. January;20(1):66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (126).Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012. May;71(5):362–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (127).Nelson PT, Braak H, Markesbery WR. Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease: a complex but coherent relationship. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009. January;68(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (128).Neth BJ, Craft S. Insulin Resistance and Alzheimer’s Disease: Bioenergetic Linkages. Front Aging Neurosci 2017. October 31;9:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (129).Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006. October 6;314(5796):130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (130).Neuropathology Group. Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS). Lancet 2001. January 20;357(9251):169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (131).Newberg A, Alavi A, Reivich M. Determination of regional cerebral function with FDG-PET imaging in neuropsychiatric disorders. Semin Nucl Med 2002. January;32(1):13–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (132).Newcomer JW, Craft S, Hershey T, Askins K, Bardgett ME. Glucocorticoid-induced impairment in declarative memory performance in adult humans. J Neurosci 1994. April;14(4):2047–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (133).Newcomer JW, Selke G, Melson AK, Hershey T, Craft S, Richards K, et al. Decreased memory performance in healthy humans induced by stress-level cortisol treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999. June;56(6):527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (134).Nixon RA, Wegiel J, Kumar A, Yu WH, Peterhoff C, Cataldo A, et al. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: an immuno-electron microscopy study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2005. February;64(2):113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (135).Nixon RA, Yang DS. Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease--locating the primary defect. Neurobiol Dis 2011. July;43(1):38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (136).Novak V, Milberg W, Hao Y, Munshi M, Novak P, Galica A, et al. Enhancement of vasoreactivity and cognition by intranasal insulin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37(3):751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (137).Okamoto Y, Ihara M, Fujita Y, Ito H, Takahashi R, Tomimoto H. Cortical microinfarcts in Alzheimer’s disease and subcortical vascular dementia. Neuroreport 2009. July 15;20(11):990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (138).Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Olokoba LB. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of current trends. Oman Med J 2012. July;27(4):269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (139).Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 1999. December 10;53(9):1937–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (140).Palsdottir H, Hunte C. Lipids in membrane protein structures. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004. November 3;1666(1–2):2–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (141).Peila R, Rodriguez BL, Launer LJ, Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Type 2 diabetes, APOE gene, and the risk for dementia and related pathologies: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes 2002. April;51(4):1256–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (142).Perlmuter LC, Hakami MK, Hodgson-Harrington C, Ginsberg J, Katz J, Singer DE, et al. Decreased cognitive function in aging non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Am J Med 1984. December;77(6):1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (143).Perry EK, Perry RH, Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Gibson PH. Coenzyme A-acetylating enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease: possible cholinergic ‘compartment’ of pyruvate dehydrogenase. Neurosci Lett 1980. May 15;18(1):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (144).Pettegrew JW, Panchalingam K, Hamilton RL, McClure RJ. Brain membrane phospholipid alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res 2001. July;26(7):771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (145).Pivovarova O, Hohn A, Grune T, Pfeiffer AF, Rudovich N. Insulin-degrading enzyme: new therapeutic target for diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease? Ann Med 2016. December;48(8):614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (146).Profenno LA, Porsteinsson AP, Faraone SV. Meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease risk with obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2010. March 15;67(6):505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (147).Pruzin JJ, Schneider JA, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Ahima RS, et al. Diabetes, Hemoglobin A1C, and Regional Alzheimer Disease and Infarct Pathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2017. Jan-Mar;31(1):41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (148).Puglielli L, Konopka G, Pack-Chung E, Ingano LA, Berezovska O, Hyman BT, et al. Acyl-coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase modulates the generation of the amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Cell Biol 2001. October;3(10):905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (149).Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2010. January 28;362(4):329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (150).Ragnarsson O, Berglund P, Eder DN, Johannsson G. Long-term cognitive impairments and attentional deficits in patients with Cushing’s disease and cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma in remission. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012. September;97(9):E1640–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (151).Ramakrishnan R, Sheeladevi R, Suthanthirarajan N. PKC-alpha mediated alterations of indoleamine contents in diabetic rat brain. Brain Res Bull 2004. August 30;64(2):189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (152).Reaven GM, Thompson LW, Nahum D, Haskins E. Relationship between hyperglycemia and cognitive function in older NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1990. January;13(1):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (153).Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, LaFrancois J, Malester B, Schmidt SD, Thomas-Bryant T, et al. A cholesterol-lowering drug reduces beta-amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2001. October;8(5):890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (154).Reger MA, Watson GS, Frey WH 2nd, Baker LD, Cholerton B, Keeling ML, et al. Effects of intranasal insulin on cognition in memory-impaired older adults: modulation by APOE genotype. Neurobiol Aging 2006. March;27(3):451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (155).Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Yun LS, Chen K, Bandy D, Minoshima S, et al. Preclinical evidence of Alzheimer’s disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N Engl J Med 1996. March 21;334(12):752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (156).Reiman EM, Chen K, Alexander GE, Caselli RJ, Bandy D, Osborne D, et al. Functional brain abnormalities in young adults at genetic risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004. January 6;101(1):284–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]