Abstract

There are two popular approaches for automated white matter parcellation using diffusion MRI tractography, including fiber clustering strategies that group white matter fibers according to their geometric trajectories and cortical-parcellation-based strategies that focus on the structural connectivity among different brain regions of interest. While multiple studies have assessed test-retest reproducibility of automated white matter parcellations using cortical-parcellation-based strategies, there are no existing studies of test-retest reproducibility of fiber clustering parcellation. In this work, we perform what we believe is the first study of fiber clustering white matter parcellation test-retest reproducibility. The assessment is performed on three test-retest diffusion MRI datasets including a total of 255 subjects across genders, a broad age range (5 to 82 years), health conditions (autism, Parkinson’s disease and healthy subjects), and imaging acquisition protocols (3 different sites). A comprehensive evaluation is conducted for a fiber clustering method that leverages an anatomically curated fiber clustering white matter atlas, with comparison to a popular cortical- parcellation-based method. The two methods are compared for the two main white matter parcellation applications of dividing the entire white matter into parcels (i.e., whole brain white matter parcellation) and identifying particular anatomical fiber tracts (i.e., anatomical fiber tract parcellation). Test-retest reproducibility is measured using both geometric and diffusion features, including volumetric overlap (wDice) and relative difference of fractional anisotropy (FA). Our experimental results in general indicate that the fiber clustering method produced more reproducible white matter parcellations than the cortical-parcellation-based method.

Keywords: Diffusion MRI, Tractography parcellation, Fiber clustering, Cortical-parcellation-based

1. Introduction

Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) provides the only existing technique to map the structural connections of the living human brain in a non-invasive way (Basser, Mattiello, and LeBihan 1994). dMRI allows the estimation of white matter fiber tracts in the brain via a process called tractography (Basser et al. 2000), which has been widely used for understanding neurological development, brain function, and brain disease, as described in several reviews (Olga Ciccarelli et al. 2008; Yamada et al. 2009; Pannek et al. 2014; Piper et al. 2014; Essayed et al. 2017). White matter parcellation, i.e. dividing the massive number of tractography fibers (streamline trajectories) into multiple fiber parcels (or fiber tracts), is the first and essential step to enable fiber quantification and visualization. White matter parcellation can enable the study of fiber parcels from the entire white matter to identify between-population differences (e.g. between patients harboring disease and healthy subjects) using machine learning or statistical analyses (Ingalhalikar et al. 2014; Fan Zhang, Wu, Ning, et al. 2018; Fan Zhang, Savadjiev, et al. 2018; Sporns, Tononi, and Kötter 2005; Zalesky et al. 2012). White matter parcellation is also important for identifying anatomical fiber tracts for clinical visualization (Nimsky et al. 2006; Golby et al. 2011; O’Donnell et al. 2017; S. Gong et al. 2018) or hypothesis-driven research (A. L. Alexander et al. 2007; Yeo, Jang, and Son 2014; C.-H. Wu et al. 2015; Shany et al. 2017; Y. Wu et al. 2018). Automated and robust white matter parcellation can enable the analysis of new, large dMRI datasets that are being acquired to study complex neural systems across the lifespan and across brain disorders (L. M. Alexander et al. 2017; Casey et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2017).

There are two popular strategies for automated white matter parcellation (O’Donnell, Golby, and Westin 2013): (1) fiber clustering that groups white matter fibers according to their geometric trajectories, aiming to reconstruct tracts corresponding to the white matter anatomy (Ding, Gore, and Anderson 2003; O’Donnell and Westin 2007; D. Wassermann et al. 2010; Visser et al. 2011; Guevara et al. 2012; Jin et al. 2014; Prasad et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2017; Garyfallidis et al. 2018; Siless et al. 2018; Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018; Garyfallidis et al. 2012) and (2) cortical-parcellation-based that parcellates tractography according to a cortical parcellation, focusing on the structural connectivity among different brain regions of interest (ROIs) (Bullmore and Sporns 2009; Sporns, Tononi, and Kötter 2005; G. Gong et al. 2009; Zalesky et al. 2012; Bastiani et al. 2012; Ingalhalikar et al. 2014; Yeh, Badre, and Verstynen 2016; Bassett and Bullmore 2016; Demian Wassermann et al. 2016; Y. Zhang et al. 2010; Wakana et al. 2007).

An important goal of white matter parcellation is to identify white matter structures that are reproducible (O’Donnell and Pasternak 2015). Test-retest reproducibility assesses whether parcellated white matter structures can be reliably reproduced for the same individual subject in repeated (test-retest) dMRI scans. Test-retest reproducibility is considered to be a good indicator of the reliability of white matter parcellation for potential clinical applications (Keihaninejad et al. 2013; Jovicich et al. 2014; Lin et al. 2013; Besseling et al. 2012; Kristo et al. 2013). To measure test-retest reproducibility, previous works have used geometrical measures such as volume, volumetric overlap, fiber length and shape, and number of fibers (Cheng et al. 2012; Kristo et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2013; Owen, Chang, and Mukherjee 2015; Smith et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2015; Cousineau et al. 2017). Other groups have used diffusion measures such as fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) computed from the voxels through which the parcellated fibers pass (Besseling et al. 2012; Kristo et al. 2013; Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013; O. Ciccarelli et al. 2003; Pfefferbaum, Adalsteinsson, and Sullivan 2003; Vollmar et al. 2010; Yendiki et al. 2016; Duan et al. 2015). While multiple studies have assessed test-retest reproducibility of white matter parcellations using cortical-parcellation-based strategies, e.g. on the brain connectome network (Besson et al. 2014; Bonilha et al. 2015; Buchanan et al. 2014; Dennis et al. 2012; Duda, Cook, and Gee 2014; Schumacher et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2015; Vaessen et al. 2010; Zhao et al. 2015; Z. Zhang et al. 2018) and on anatomical fiber tracts (Besseling et al. 2012; Cousineau et al. 2017; Heiervang et al. 2006; Kristo et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2013; Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013; Tensaouti et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2012; Yendiki et al. 2016), there are no existing studies of fiber clustering, to our knowledge. Studies have suggested that fiber clustering approaches have advantages in parcellating the white matter in a highly consistent way, aiming to reconstruct fiber parcels/tracts corresponding to the white matter anatomy (Ziyan et al. 2009; Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018; Ge et al. 2012; Sydnor et al. 2018; F. Zhang, Norton, et al. 2017), while cortical-parcellation-based methods could be less consistent considering factors such as the variability of inter-subject cortical anatomy, the dependence on registration between dMRI and structural images, and the presence of false positive/negative connections (Amunts et al. 1999; Fischl et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 2018; Sinke et al. 2018; Maier-Hein et al. 2017). However, to our knowledge, test-retest reproducibility of the cortical-parcellation-based and fiber clustering white matter parcellation strategies has not yet been quantitatively compared.

In the present work, we conduct what we believe is the first study to investigate the test-retest reproducibility of fiber clustering white matter parcellation. An fiber clustering method based on an anatomically curated white matter fiber clustering atlas (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018) is evaluated, with comparison to a cortical-parcellation-based method based on a cortical and subcortical parcellation from Freesurfer (Bruce Fischl 2012). Both of these white matter parcellation methods have been demonstrated to be successful in comparison to manual tract parcellation (Sydnor et al. 2018; O’Donnell et al. 2017; Demian Wassermann et al. 2016). Here, the test-retest reproducibility of the two methods is compared for two main applications: 1) whole brain white matter parcellation, i.e., dividing the entire white matter into fiber parcels, and 2) anatomical fiber tract parcellation, i.e., identifying particular anatomical fiber tracts. Multiple quantitative measurements, including a geometrical measure (volumetric overlap) and a diffusion measure (FA), are computed for test-retest reproducibility evaluation. A large test-retest dataset is studied, including a total of 255 subjects from multiple independently acquired populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets, data processing and tractography

In this study, we evaluated the test-retest reproducibility of two white matter parcellation methods on dMRI data from a total of 255 subjects across genders (87 females vs 168 males), a broad age range (children, young adults and older adults, from 5 to 82 years), and different health conditions (autism, Parkinson’s disease and healthy subjects). This publicly available test-retest dMRI data was from three independently acquired datasets with different diffusion imaging protocols. Table 1 gives an overview of the datasets studied, including demographic information and diffusion image acquisitions.

Table 1:

Demographics and dMRI data of the datasets under study.

| Dataset | # subjects | Age | Gender | Health condition | dMRI data studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE II | 70 | 5 to 17 years (12.0 ± 3.1) | 6 F 64 M |

49 AUT 21 healthy |

1 b0 image 63 gradient directions (b=1000) TE/TR=78/5200 ms resolution=3 mm3 (isotropic) test-retest interval: in same scan session |

| HCP | 44 | 22 to 35 years (30.4 ± 3.3) | 31 F 13 M |

44 healthy | 18 b0 images 90 gradient directions (b=3000) TE/TR=89/5520 ms resolution=1.25 mm3 (isotropic) test-retest interval: 18 to 328 days (134±62) |

| PPMI | 141 | 51 to 82 years (63.7 ± 7.2) |

50 F 91 M |

100 PD 41 healthy |

1 b0 image 63 gradient directions (b=1000) TE/TR=88/7600 ms resolution=2 mm3 (isotropic) test-retest interval: in same scan session |

Abbreviations: Dataset: ABIDE-II - Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange II (Di Martino et al. 2017); HCP - Human Connectome Project (Van Essen et al. 2013); PPMI - Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (Marek et al. 2011); Gender: F - female; M - Male. Disease: AUT - autism; PD - Parkinson’s disease.

For each of the subjects under study, the test-retest dMRI scans were preprocessed to exclude any potential artifacts, e.g., from eddy current and head motion effects. Details of the preprocessing steps for each dataset under study are included in Appendix. Whole brain tractography was then computed using the two-tensor unscented Kalman filter (UKF) method (Malcolm, Shenton, and Rathi 2010; Reddy and Rathi 2016), as implemented in the ukftractography package (https://github.com/pnlbwh/ukftractography). The UKF method fits a mixture model of two tensors to the dMRI data while tracking fibers, employing prior information from the previous step to help stabilize model fitting. We chose the UKF method because it has been shown to be highly consistent in tracking fibers in dMRI data from independently acquired populations across ages, health conditions and image acquisitions (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018), and it is more sensitive than standard single-tensor tractography, in particular in the presence of crossing fibers and peritumoral edema (Baumgartner et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2015, 2016; Liao et al. 2017). For each of the subjects under study, the tractography produced about 1 million fibers per dMRI scan. Details of the related tractography parameters are included in Appendix.

For each subject, the tractography datasets computed from the two test-retest dMRI scans were aligned into the same space. This was conducted by computing a registration between the FA images computed from the dMRI scans. The Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTS) package (https://github.com/ANTsX/ANTs) (Avants, Tustison, and Song 2009) was used to perform the registration, following the default steps in the software including a rigid, an affine, then a deformable transformation to reach a good intra-subject alignment. Here, we chose an FA-based registration because the FA image is sensitive to white matter fiber tracts and can provide a good correspondence between the registered fiber tracts (Goodlett et al. 2006), and it has been applied in many studies for registering between dMRI datasets (Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013; Vollmar et al. 2010; Besseling et al. 2012). In details, this registration was performed by aligning the FA image from the second scan to that from the first scan. The obtained transforms were then applied to the tractography data computed from the second scan, using 3D Slicer. This step ensured the tractography data from the second scan was registered to the space of the first scan. In this way, because transforms were applied after performing tractography, any resampling or blurring of diffusion-weighted image data was avoided.

2.2. White matter parcellation

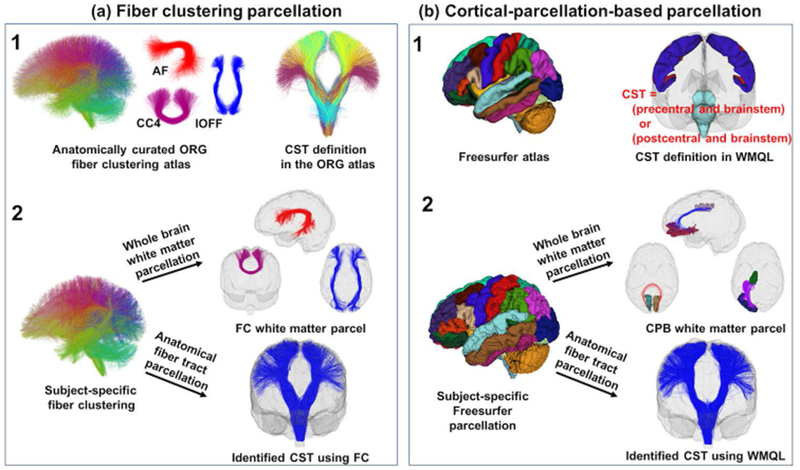

After obtaining whole brain tractography, white matter parcellation was performed using the two methods (fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based), as illustrated in Figure 1. For each method, both whole brain white matter parcellation and anatomical fiber tract parcellation were performed. Details of each parcellation method are introduced below.

Figure 1.

Overview of the two white matter parcellation methods. Sub-figure (a) shows the fiber clustering (FC) method. It relies on an O’Donnell Research Group (ORG) fiber clustering atlas (a.1) that includes an 800-cluster parcellation of the entire white matter and an anatomical fiber tract parcellation. Whole brain white matter parcellation (a.2) is performed by identifying subject-specific fiber clusters according to the 800-cluster atlas parcellation (a.2). Anatomical fiber tract parcellation (a.2) is performed by leveraging the anatomically curated tracts in the atlas. Sub-figure (b) shows the cortical-parcellation-based (CPB) method. It relies on a neuroanatomical brain parcellation atlas from Freesurfer to segment an individual’s brain into multiple cortical and subcortical regions (b.1). Whole brain white matter parcellation (b.2) is performed by identifying fiber parcels connecting between each pair of the segmented regions of interest (ROIs). Anatomical fiber tract parcellation (b.2) is performed by leveraging White Matter Query Language (WMQL), which provides anatomical definitions of fiber tracts based on their intersected Freesurfer regions (e.g., the CST).

2.2.1. Fiber clustering white matter parcellation

The fiber clustering method performs white matter parcellation of an individual subject based on an fiber clustering atlas (Figure 1.a.1) provided by the O’Donnell Research Group (ORG) (http://dmri.slicer.org/atlases) (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018). The ORG atlas contains an 800-cluster parcellation of the entire white matter and an anatomical fiber tract parcellation, including 58 deep white matter fiber tracts, plus 198 short and medium range superficial fiber clusters organized into 16 categories according to the brain lobes they connect. (The atlas was generated by creating dense tractography maps (using the same UKF tractography method as in the current study) of 100 individual HCP subjects and then applying an fiber clustering method to group the tracts across subjects according to their similarity in shape and location. The resulting clusters were annotated using expert neuroanatomical knowledge.) We chose the ORG-atlas-based fiber clustering method because it is an anatomically curated white matter atlas that has been demonstrated to have a good performance for consistent white matter parcellation across different populations (Zhang et al., 2018c).

The fiber clustering method was applied to perform white matter parcellation of one subject as follows. A tractography-based registration was performed to align the subject’s tractography data into the atlas space. A fiber spectral embedding was conducted to compute the similarity of fibers between the subject and the atlas, followed by the assignment of each fiber of the subject to the corresponding atlas cluster. This process produced a whole brain white matter parcellation into 800 fiber clusters. (This parcellation scale of 800 fiber clusters has been chosen to successfully separate white matter structures considered to be anatomically different (O’Donnell et al. 2017; Fan Zhang, Wu, Ning, et al. 2018; Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018).) These fiber clusters included 84 commissural clusters as well as 716 bilateral hemispheric clusters (that included fibers in both hemispheres). We separated the hemispheric clusters by hemisphere (the maximum number of clusters is thus (716 × 2 + 84) = 1516); therefore, we produced over 800 parcels for each subject (see experimental results in Section 3.1 for the number of parcels). Next, for anatomical fiber tract parcellation, we leveraged the anatomically curated tracts in the atlas. Each tract was comprised of a set of fiber clusters. In our study, we used 45 tracts (see Table 2 for the list of the tracts) that are defined in both the fiber clustering method and the cortical-parcellation-based method (Section 2.2.2). All fiber clustering processing was performed using the whitematteranalysis software (https://github.com/SlicerDMRI/whitematteranalysis), and all parameters were set to their default values. (Details are described in (O’Donnell and Westin 2007; O’Donnell et al. 2012, 2017; Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018).)

Table 2.

A total of 45 fiber tracts are compared between the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods, including 24 hemispheric (LR) association tracts, 7 commissural (C) tracts, and 14 hemispheric (LR) projection tracts. These tracts are the ones that can be identified in both of the parcellation methods.

| Tract category (number of tracts) | Tract name |

|---|---|

| Association tracts (24) | arcuate fasciculus (AF) – LR cingulum bundle (CB) – LR external capsule (EC) – LR extreme capsule (EmC) – LR inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) – LR inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus (IoFF) – LR middle longitudinal fasciculus (MdLF) – LR posterior limb of internal capsule (PLIC) – LR superior longitudinal fasciculus I (SLF I) – LR superior longitudinal fasciculus II (SLF II) – LR superior longitudinal fasciculus II (SLF III) – LR uncinate fasciculus (UF) – LR |

| Commissural tracts (7) | corpus callosum 1 (CC 1) – C corpus callosum 2 (CC 2) – C corpus callosum 3 (CC 3) – C corpus callosum 4 (CC 4) – C corpus callosum 5 (CC 5) – C corpus callosum 6 (CC 6) – C corpus callosum 7 (CC 7) – C |

| Projection tracts (14) | corticospinal tract (CST) – LR striato-frontal (SF) – LR striato-occipital (SO) – LR striato-parietal (SP) – LR thalamo-frontal (TF) – LR thalamo-occipital (TO) – LR thalamo-parietal (TP) – LR |

2.2.2. Cortical-parcellation-based white matter parcellation

The cortical-parcellation-based method performs white matter parcellation based on Freesurfer (http://freesurfer.net) (Bruce Fischl 2012). Freesurfer anatomically segments brain regions of an individual subject based on brain atlases including a cortical (Desikan et al. 2006) and a subcortical parcellation (Bruce Fischl et al. 2002) (Figure 1.b.1). We chose the Freesurfer-based cortical-parcellation-based method for comparison because it has been applied in many studies of the test-retest reproducibility of whole brain white matter parcellation (Besson et al. 2014; Bonilha et al. 2015; Buchanan et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2015) and anatomical fiber tract parcellation (Cousineau et al. 2017; Ning et al. 2016; Roy et al. 2017; Yendiki et al. 2016).

The cortical-parcellation-based method was applied to perform white matter parcellation of one subject as follows. The Freesurfer segmentation of an individual subject (Figure 1.b.2) was performed using the T1-weighted image. Registration between the T1-weighted and dMRI images was performed (see Appendix) so that the tractography data was in the same space as the Freesurfer parcellation result. Then, for whole brain white matter parcellation, we identified parcels connecting between all pairs of segmented cortical and subcortical regions (Figure 1.b.2), as in many previous studies (Besson et al. 2014; Bonilha et al. 2015; Buchanan et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2015). The Freesurfer atlases (Desikan et al. 2006; Bruce Fischl et al. 2002) include a total of 87 regions of interest (ROIs). Therefore, the cortical-parcellation-based whole brain parcellation resulted in a total of 3741 (87 × 86 / 2) parcels per subject. Next, for anatomical fiber tract parcellation, we leveraged the White Matter Query Language (WMQL) (https://github.com/demianw/tract_querier) (Demian Wassermann et al. 2016), an automated method to delineate anatomical fiber tracts based on the Freesurfer anatomical regions they intersect (Figure 1.b.1). In our study, we applied WMQL because it enables identification of a relatively large number of fiber tracts (45 tracts) and it has been used in multiple works to study white matter parcellation retest-retest reproducibility (Ning et al. 2016; Roy et al. 2017; Cousineau et al. 2017). For a given anatomical fiber tract, subject-specific parcellation was performed by identifying the fibers from the whole brain tractography that met the tract’s anatomical definition (Figure 1.b.2). In our work, a total of 45 anatomical fiber tracts that had available WMQL tract definitions were extracted for each subject under study (the same tracts as in the fiber clustering method; see Table 2 for the list of the tracts).

2.3. Test-retest measurements

After performing white matter parcellation, we computed test-retest measurements of the parcellated white matter structures (whole-brain fiber parcels or anatomical fiber tracts) to evaluate the reproducibility of the parcellation performance. We included both geometrical and diffusion measures.

For a geometrical measure, we computed the volumetric overlap between the parcellated white matter structures to investigate if they had the same volume and shape. We applied the weighted Dice (wDice) coefficient that was designed specifically for measuring volumetric overlap of fiber tracts (Cousineau et al. 2017). wDice extends the standard Dice coefficient (Dice 1945) taking account of the number of fibers per voxel so that it gives higher weighting to voxels with dense fibers, as follows:

| (1) |

where P1 and P2 represent two corresponding parcellated white matter structures from the test-retest data, v’ indicates the set of voxels that are within the intersection of the volumes of P1 and P2, v indicates the set of voxels that are within the union of the volumes of P1 and P2, and W is the fraction of the fibers passing through a voxel. A high wDice value represents a high reproducibility between the two corresponding parcellated white matter structures.

Then, for a diffusion measure, we calculated the reproducibility of the mean FA of the voxels where the parcellated white matter structures were located. In related work, Papinutto et al. evaluated reproducibility by computing the absolute difference between mean FA values divided by the average of the two mean FA values (Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013). In our study, we adopted a similar evaluation strategy and extended it by measuring a relative difference, i.e., the absolute difference divided by the sum of the mean FA values. We chose this approach because diffusion properties (e.g. FA) are different across different white matter structures (Pierpaoli et al. 1996; Madden et al. 2004; De Santis et al. 2014), and relative difference can provide comparable values across different structures. This was essential for comparing the reproducibility of the whole brain parcellations across methods, because there was no one-to-one correspondence between the white matter parcels produced by the two methods. Specifically, for two corresponding parcellated white matter structures P1 and P2 from the test-retest scans, we computed the mean FA of the voxels where their fibers passed, and measured the relative difference of the mean FA values, as follows:

| (2) |

A low relative difference value represents a high reproducibility between the two parcellated white matter structures. (We note that we have provided the results of the reproducibility of the mean MD, analyzed in the same way as the mean FA, in Supplementary Material 1.)

2.4. Statistical analysis

We then performed statistical comparisons between the two parcellation methods based on the computed test-retest measurements. These statistics were performed in each of the three datasets.

1). Whole brain white matter parcellation:

The parcellation methods were compared in two ways, including a comparison using all parcels and a more fine-grained comparison using parcels with similar volumes. First, for each parcel, we computed the mean wDice score and mean relative difference value across all subjects for each parcellation method. This gave a vector of mean wDice scores (and another vector of mean relative difference values), with length of the number of parcels, for each method. We compared the wDice (and also relative difference) measurements across methods using an unpaired two-sample Student’s (two-tailed) t-test, for each of the three datasets separately. Second, we compared parcels with similar volumes across the two methods. To enable this, we created a histogram by binning parcels into 50 bins evenly distributed between 0 to 100,000 mm3 (approximately the maximum volume size across all parcels). To compare parcels in each bin across methods, we performed an unpaired two-sample Student’s (two-tailed) t-test to analyze both the mean wDice and mean relative difference of these parcels. The false discovery rate (FDR) procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) was used to control for multiple comparisons (across all bins). We excluded a bin if the number of parcels in either method was 0. We note that, to eliminate potential biases from inconsistent parcels, for each method we included only the parcels that were detected in at least 95% of subjects (see Table 3 for the number of retained parcels).

Table 3:

Number of white matter parcels retained in each dataset after removing the parcels that were not consistently detected across subjects in each dataset. The parcels that were detected in at least 95% of the subjects in each dataset were retained (Section 2.4.1). The median of the mean volume of the retained parcels in each dataset is given in parentheses.

| ABIDE-II | HCP | PPMI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| fiber clustering | 1274 (9,569 mm3) | 1499 (10,088 mm3) | 1373 (10,025 mm3) |

| cortical-parcellation-based | 1968 (9,081 mm3) | 2350 (8,853 mm3) | 2269 (9,513 mm3) |

2). Anatomical fiber tract parcellation:

The parcellation methods were compared in two ways, including a comparison using all tracts and a more fine-grained comparison using individual tracts. First, for each tract, we computed the mean wDice and mean relative difference across all subjects for each parcellation method. We compared these measurements between methods using a paired two-sample Student’s (two-tailed) t-test. (The paired test was performed because the same set of anatomical tracts was selected in the fiber clustering method to match the set of tracts parcellated in the cortical-parcellation-based method.) Second, we compared individual tracts. For each tract, we analyzed the wDice and relative difference from all subjects using a paired two-sample Student’s (two-tailed) t-test. The FDR procedure was used to control for multiple comparisons across all tracts.

3. Results

3.1. Whole brain white matter parcellation results

Table 3 shows the number and volume of retained white matter parcels after removing the ones that were not consistently detected across each dataset (Section 2.4.1). While the number of retained parcels was different between the two methods across the three datasets (p = 0.006; paired t-test, two-tailed), their median parcel volumes were similar (p = 0.151; paired t-test, two-tailed).

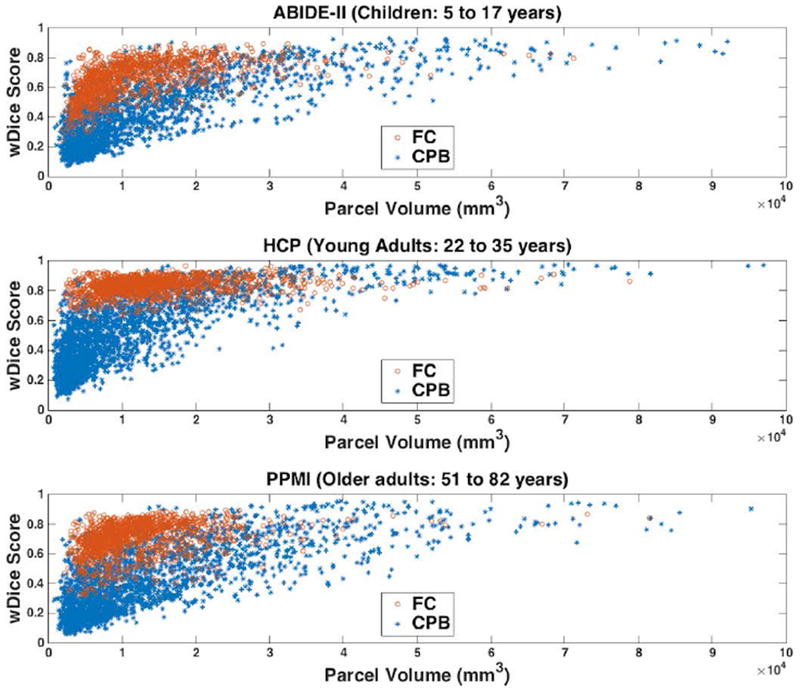

Volumetric overlap of whole brain white matter parcels:

Figure 2 shows the distributions of the mean wDice scores in each dataset, after application of the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods. Because there was no one-to-one correspondence of the parcels between the two methods, we plotted the mean wDice of each parcel versus its mean volume. This enables a visual comparison of method performance for parcels with various volumes. It is visually apparent that the mean wDice was generally lower and had a larger range in the cortical-parcellation-based method than the fiber clustering method. For quantitative assessment, in the comparison using all parcels, significantly higher mean wDice was achieved using the fiber clustering method compared to the cortical-parcellation-based method, with p<0.001 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed) for each of the three datasets. In the more fine-grained comparison using parcels with similar volumes (parcels within the same bin of the parcel volume histogram), 63.16%, 58.97% and 69.70% of all retained bins, respectively, in the ABIDE-II, HCP and PPMI datasets, had significantly higher mean wDice scores using the fiber clustering method (p<0.05, unpaired t-test, two-tailed; FDR corrected), while no bins had significantly higher mean wDice scores using the cortical-parcellation-based method. (See Supplementary Material 2 for the number of the retained bins in each dataset after removing the ones that had 0 parcels in either method.)

Figure 2.

Volumetric overlap of white matter parcels computed from the test-retest dMRI data using the fiber clustering (FC) and cortical-parcellation-based (CPB) methods. Each plotted point represents one parcel and shows the parcel’s mean wDice score versus the mean parcel volume across all subjects in one dataset. A high wDice score represents a high test-retest reproducibility.

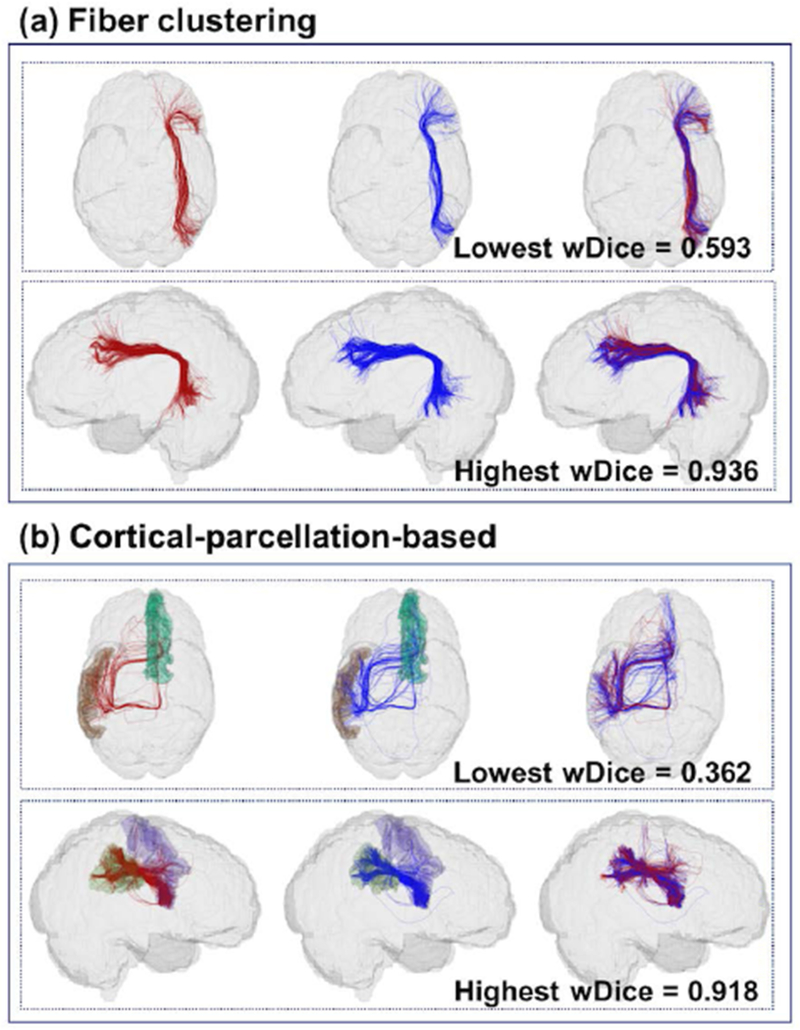

For visual quality assessment of the volumetric overlap performance, Figure 3 gives a visual comparison of the white matter parcels obtained using the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods. We identified the most and the least reproducible parcels from both methods, in terms of wDice score, for a certain parcel volume. In Figure 3, white matter parcels with volume around 10,000 mm3 (from one subject in the HCP dataset) are displayed. This volume was chosen as approximately the average of the median of the parcel volumes of the six parcellations (two parcellation methods for each of the three datasets).

Figure 3:

Visualization of volumetric overlap of white matter parcels (red - first scan; blue - second scan) obtained using the two parcellation methods. In the fiber clustering method, the parcel with the lowest wDice corresponds to the atlas cluster #728; the parcel with the highest wDice score corresponds to the atlas cluster #206. In the cortical-parcellation-based method, the parcel with the lowest wDice connects to the Freesurfer regions of the left middle temporal gyrus (brown) and right hemispheric superior frontal gyrus (dark green); the parcel with the highest wDice score connects to the Freesurfer regions of the right hemispheric precentral gyrus (purple) and the right hemispheric supramarginal gyrus (light green).

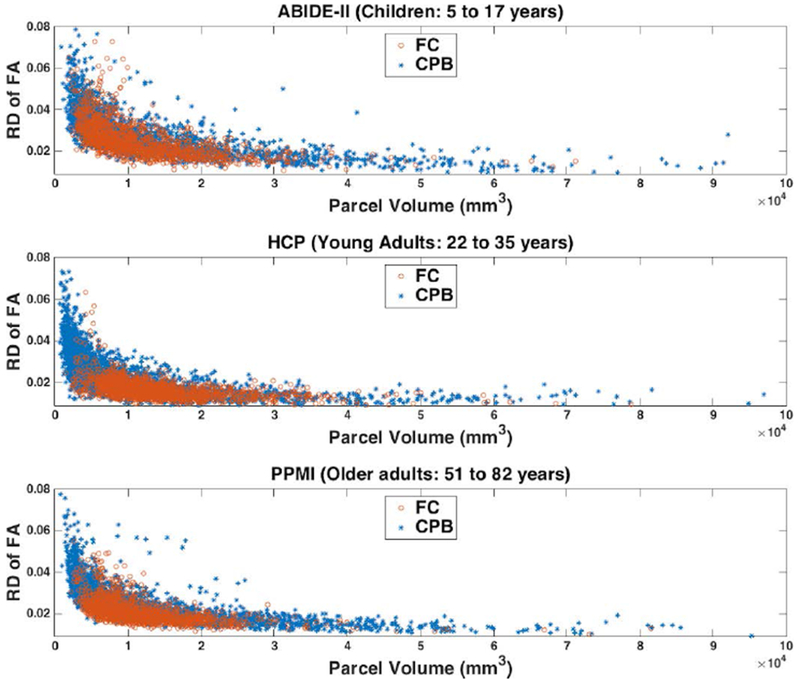

Relative difference of FA of whole brain white matter parcels:

Figure 4 shows the distributions of the mean relative difference of the white matter parcels in the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods, versus the mean parcel volume, in each dataset. We can observe that fiber clustering method obtained visually lower mean relative difference than the cortical-parcellation-based method; however, this visual difference is not as apparent as that observed in the mean wDice (Figure 2). For quantitative assessment, in the comparison using all parcels, significantly lower mean relative difference was achieved using the fiber clustering method compared to the cortical-parcellation-based method, with p<0.001 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed) for each of the three datasets. In the more fine-grained comparison using parcels with similar volumes (parcels within the same bin of the parcel volume histogram), 7.89%, 23.08% and 48.48% of all retained bins, respectively, in the ABIDE-II, HCP and PPMI datasets, had significantly lower mean relative difference values using the fiber clustering method (p<0.05, unpaired t-test, two-tailed; FDR corrected), while no bins had significantly lower mean relative difference values using the cortical-parcellation-based method. (See Supplementary Material 2 for the number of the retained bins in each dataset after removing the ones that had 0 parcels in either method.)

Figure 4.

Reproducibility of diffusion FA measure of white matter parcels computed from the test-retest dMRI data using the fiber clustering (FC) and cortical-parcellation-based (CPB) methods. In the plots, each point represents the mean relative difference (RD) of FA versus the mean parcel volume across all subjects in one dataset. A low relative difference value represents a high test-retest reproducibility.

3.2. Anatomical fiber tract parcellation results

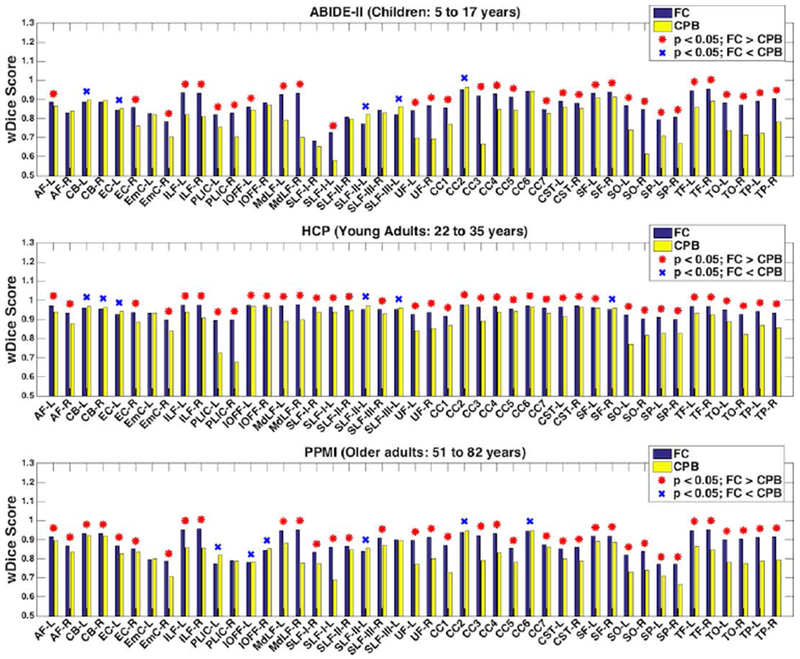

Volumetric overlap of anatomical fiber tracts:

Figure 5 shows the mean wDice of the 45 anatomical fiber tracts in each dataset, after application of the fiber clustering and the cortical-parcellation-based methods. In the comparison using all 45 tracts, significantly higher mean wDice was found using the fiber clustering method than the cortical-parcellation-based method in all of the three datasets, with p<0.001 (paired t-test, two-tailed). In the more fine-grained comparison using individual tracts, 32, 38 and 36 tracts, respectively, in the ABIDE-II, HCP and PPMI datasets, had significantly higher wDice scores using the fiber clustering method, while 5, 6 and 6 tracts had significantly higher wDice scores using the cortical-parcellation-based method (p < 0.05, paired t-test, two-tailed; FDR corrected). (Additional results on the tract volume are provided in Supplementary Material 3.)

Figure 5.

Volumetric overlap of anatomical fiber tracts identified from the test-retest dMRI data using the fiber clustering (FC) and cortical-parcellation-based (CPB) methods. Plots show the mean wDice score (averaged across subjects in each dataset) for each tract. A high wDice score represents a high test-retest reproducibility. The tracts with significantly higher mean wDice scores using the fiber clustering method are annotated with a red asterisk, while the tracts with significantly higher mean wDice scores using the cortical-parcellation-based method are annotated with a blue X.

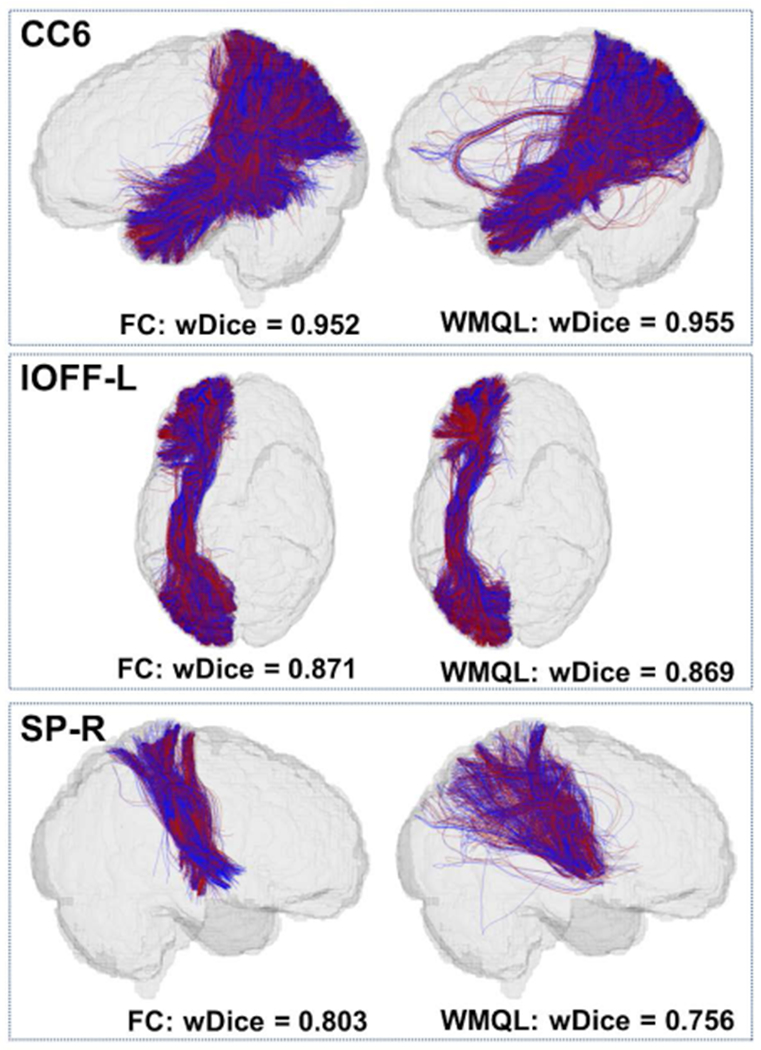

For visual quality assessment of the volumetric overlap performance, Figure 6 gives an visualization of the tracts obtained using the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods by showing the ones with high or low volumetric overlaps. To create this visualization, we computed an average wDice score for each tract. This average was computed across the results from all methods and datasets in that tract (across the two methods and three datasets). This gave a total of 45 average wDice values, one per tract. We then identified the tracts with the maximum, the median and the minimum mean wDice scores, which were the corpus callosum 6 (CC6), the left inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus (IOFF-L), the right striato-parietal (SP-R) tracts, respectively. In Figure 6, we display these three tracts from one HCP dataset.

Figure 6.

Visualization of volumetric overlap of example anatomical fiber tracts (red - first scan; blue - second scan) identified using the two parcellation methods. These three tracts have the maximum, the median and the minimum mean wDice scores. The tracts are corpus callosum 6 (CC6), left inferior occipito-frontal fasciculus (IOFF-L), and right striato-parietal (SP-R) tract.

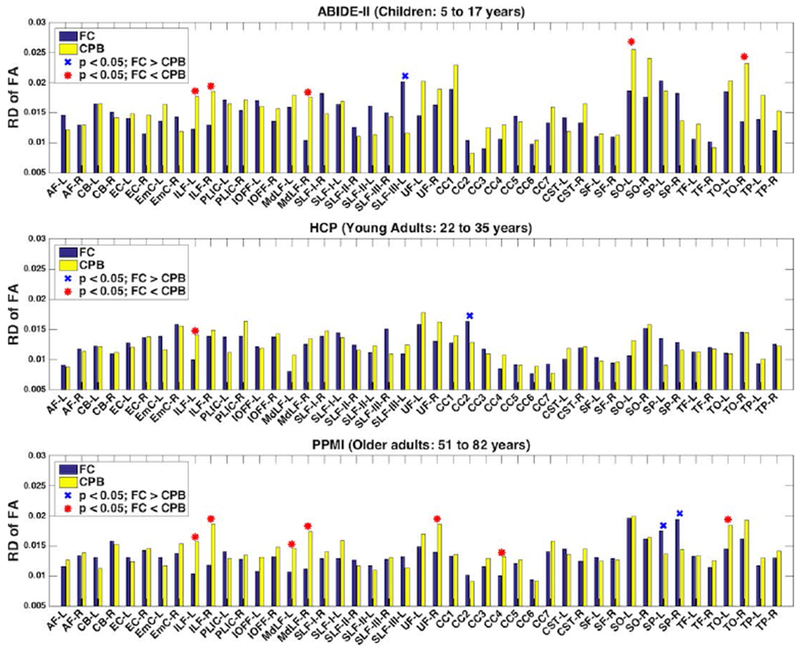

Relative difference of FA of anatomical fiber tracts:

Figure 7 shows the mean relative difference of FA of the 45 anatomical fiber tracts in each dataset, after application of the fiber clustering and the WMQL methods. In the statistical comparison across all 45 tracts, two of the three datasets (ABIDE-II and PPMI) had significantly lower relative difference values in the fiber clustering method than in the cortical-parcellation-based method (p=0.032 and 0.012, respectively, paired t-test, two-tailed), while there was no significant difference between the two methods in the HCP dataset (p=0.620, paired t-test, two-tailed). In the comparison on individual fiber tracts, 5, 1 and 7 tracts, respectively, in the ABIDE-II, HCP and PPMI datasets, had significantly lower relative difference values using the fiber clustering method, while 1, 1 and 2 tracts had significantly lower relative difference values using the cortical-parcellation-based method (p < 0.05, paired t-test, two-tailed; FDR corrected).

Figure 7:

Reproducibility of diffusion FA measure of anatomical fiber tracts identified from the test-retest dMRI data using the fiber clustering (FC) and cortical-parcellation-based (CPB) methods. A low relative difference (RD) value represents a high test-retest reproducibility. The tracts with significantly lower mean relative difference scores using the fiber clustering method are annotated with a red asterisk, while the tracts with significantly lower mean relative difference scores using the cortical-parcellation-based method are annotated with a blue X.

4. Discussion

In this work, we assessed test-retest reproducibility of two popular white matter tract parcellation strategies, including a white-matter-atlas-based fiber clustering method and a Freesurfer-based cortical-parcellation-based method. Overall, we found that the fiber clustering method had significantly higher reproducibility than the cortical-parcellation-based method in white matter parcellations for dividing the entire white matter into whole-brain parcels and identifying anatomical fiber tracts. When comparing all parcellated structures (either all whole-brain parcels or all anatomical tracts), the fiber clustering method obtained significantly higher reproducibility on both volumetric overlap and relative difference of FA in all of the three datasets. In more fine-grained comparisons on individual anatomical tracts, volumetric overlap and relative difference of FA were significantly higher using the fiber clustering method in 73.10% and 9.63% of tracts, respectively, on average across the 3 datasets. In contrast, volumetric overlap and relative difference of FA were significantly higher in 12.59% of tracts and 2.96% of tracts using the cortical-parcellation-based method. Below, we discuss several detailed observations regarding the comparison results for these two types of white matter parcellation.

We found that the test-retest reproducibility of white matter parcels obtained in whole brain white matter parcellation was highly related to their parcel volumes, such that parcels with larger volumes tended to be more reproducible. The cortical-parcellation-based method generated a white matter parcel based on its connected cortical or subcortical ROIs, where large-size ROIs likely generated parcels with large volumes. As a result, the reproducibility of a cortical-parcellation-based parcel was highly determined by the size of its connected ROIs, in agreement with other findings in the literature (Chamberland et al. 2017). For example, the most reproducible cortical-parcellation-based parcels connected to large-size Freesurfer regions such as the superior frontal gyrus and the rostral middle frontal gyrus (see Supplementary Material 4). Similar results related to the ROI size in cortical-parcellation-based strategies have also been reported in several previous studies (Bonilha et al. 2015; Cheng et al. 2012). On the other hand, the fiber clustering method produced white matter parcels based on the white matter anatomy. It did not require any gray matter anatomical information; thus it would not be affected by the sizes of ROIs. For instance, we found that the fiber clustering parcels related to the frontal pole, which is a relatively small Freesurfer cortical ROI, were highly reproducible (see Supplementary Material 4). However, while the cortical-parcellation-based method in general had the highest test-retest reproducibility on the largest volume parcels, the fiber clustering method did not produce parcels with volumes as large as the largest volume parcels from the cortical-parcellation-based method. For example, there were only a small number of fiber clustering parcels with volumes over 40,000mm3 (Figure 2).

We observed that the volumetric overlap of the anatomical fiber tracts was more sensitive than the diffusion FA measure for finding differences in test-retest reproducibility between the methods. There were a higher number of significant differences between the two methods when using the wDice overlap score than relative difference of FA (Figures 5 vs 7). The wDice score was driven by non-overlapping voxels that were not intersected by the white matter structure in both test-retest scans, while the relative difference of FA was driven by the FA differences of these voxels. It is possible that the higher number of significant differences using wDice, when compared to relative difference of FA, can be attributed to the fact that the measured FA is averaged in the entire tract. wDice is expected to be more sensitive to small changes in the borders or edges of the fiber tract, which may not greatly affect the tract mean FA. Therefore, small differences in the voxels intersected by the fiber tract do not have a large effect on the measured mean FA. In the field of studying brain white matter properties (e.g., for analyzing disease analysis, understanding neurodevelopment, etc.), the reproducibility of diffusion measures (such as FA and MD) is highly important. Our results suggested that the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods performed comparably on a diffusion measure (Figure 7). For example, while there were a larger number of tracts with significantly lower relative difference values using the fiber clustering method in the ABIDE II (5 versus 1 in the cortical-parcellation-based method) and PPMI (7 versus 2 in the cortical-parcellation-based method) datasets, both methods had the same number of tracts with significantly lower relative difference values in the HCP dataset (1 versus 1).

In comparison to related work on test-retest reproducibility of white matter parcellation, we found that both of the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods performed relatively well. While existing studies applied different evaluation criteria using different testing datasets (Cheng et al. 2012; Kristo et al. 2013; Lin et al. 2013; Owen, Chang, and Mukherjee 2015; Smith et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2015; Cousineau et al. 2017; Besseling et al. 2012; O. Ciccarelli et al. 2003; Duan et al. 2015; Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013; Pfefferbaum, Adalsteinsson, and Sullivan 2003; Vollmar et al. 2010; Yendiki et al. 2016), one study performed volumetric-overlap-based experiments in a comparable way to the present study (Cousineau et al. 2017). In this work, Cousineau et al. studied test-retest reproducibility of a Freesurfer-based cortical-parcellation-based anatomical tract parcellation on PPMI data and suggested a threshold for a good wDice score to be 0.72 (based on an analysis of the mean wDice score across data in a healthy population) (Cousineau et al. 2017). Although different parcellated tracts and different PPMI subject subsets were analyzed, 44 of 45 cortical-parcellation-based parcellated tracts and all fiber clustering parcellated tracts had mean wDice scores over 0.72 in our PPMI dataset, while only 8 of 28 parcellated tracts in (Cousineau et al. 2017) had mean wDice scores over this threshold. (This difference could potentially relate to the high consistency of UKF tractography across different scan protocols and age groups (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018). On average across all three datasets in our study, 87.41% of cortical-parcellation-based parcellated tracts and 99.26% of fiber clustering parcellated tracts had mean wDice scores over 0.72. In another study, Papinutto et al. measured test-retest reproducibility of FA of three tracts to evaluate across different acquisition dMRI parameters, and they reported that the lowest mean reproducibility error was around 2.4% (corresponding to an mean relative difference value of 0.012 in our study) (Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013). In our study, on average across all the three datasets, the mean relative difference values were 0.0122 and 0.0139 using the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods, respectively, which were close to the lowest value reported by Papinutto et al. In addition to comparison with existing work, we observed that changes in tract FA values between the test-retest scans (|FA1st - FA2nd| / FA1st) were relatively small (see Supplementary Material 5 for details). On average across the three datasets, FA changes of only 3.11% and 3.40% were observed in the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods, respectively. These statistics showed that the cortical-parcellation-based and fiber clustering methods used in the present study obtained generally reproducible results.

Overall, the differences of the test-retest reproducibility results from the two white matter parcellation methods can be explained as follows. First, the methods had different assumptions relative to the input tractography. The cortical-parcellation-based method relied on particular points on the fibers, especially on fiber terminal regions. Parcellation results were thus sensitive to whether the fiber endpoints touched the cortical and subcortical ROI. This could be affected by multiple factors, e.g., whether tractography could track through the low-anisotropy interface between gray matter and white matter or in deep gray matter regions near corticospinal fluid (CSF), where fiber endpoints are uncertain. The fiber clustering method, on the other hand, used all points on the fibers, i.e. the full length of the fiber trajectory. In this way, fibers whose endpoints did not quite reach the cortex or the subcortical structures could nevertheless be parcellated. Using the entire fiber trajectory could also enable localization of compact fiber clustering parcels, within which all fibers followed similar paths. This tendency toward compact fiber clustering parcels, versus the potentially more dispersed or spatially sparse parcels that were possible in the cortical-parcellation-based method (Figure 3), could also partially explain the higher volumetric overlap observed in the fiber clustering method. Second, the two methods applied different image registration steps to align the input tractography data to an atlas parcellation space. The cortical-parcellation-based method used multiple registration steps, including a registration between the subject-specific dMRI data and the subject-specific T1-weighted data, and a registration between the subject-specific T1-weighted data and the Freesurfer atlas. While there are sophisticated tools to compute these registrations (Avants et al. 2009; Jenkinson et al. 2012), the performance is limited by non-trivial factors. For example, the inter-modality registration between dMRI and T1-weighted can be affected by differences in image resolutions (Malinsky et al. 2013) echo-planar imaging (EPI) distortion in dMRI data (Albi et al. 2018). Large individual anatomical variations with respect to the atlas population could also affect, or even cause to fail, the subject-specific T1 registration to the atlas. For example, Freesurfer has been shown to have limited success in neonates (Makropoulos et al. 2017) and patients with brain tumors or other structural lesions (F. Zhang, Kahali, et al. 2017). In contrast, the fiber clustering method needed only one intra-modality registration step between the subject-specific tractography data and the atlas tractography data. This registration, in combination with robust fiber spectral embedding in the atlas space, has been demonstrated to enable successful white matter parcellation across subjects from different populations, including neonates, young children and brain tumor patients, who had large neuroanatomical variations to the atlas population (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018). Third, the two methods adopted different ways to handle false positive fibers that have been suggested to be a contributing factor affecting white matter parcellation reproducibility (Maier-Hein et al. 2017). In the present study, we applied a multi-fiber UKF tractography method to increase the sensitivity in tracking crossing fibers (Baumgartner et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2015, 2016; Liao et al. 2017). The high sensitivity has been suggested to be important to reduce false negatives, but at the expense of increased false positives (Maier-Hein et al. 2017; Thomas et al. 2014). Therefore, the UKF method, as well as other sensitive fiber tracking methods (Christiaens et al. 2015; Jeurissen et al. 2014), may introduce more false positive or anatomically incorrect errors compared to a standard single-fiber diffusion tensor fiber tracking method. Prior anatomical knowledge is often used to exclude false positive fibers by employing additional constraints and expert judgement (Conturo et al. 1999; Huang et al. 2004; Yeh et al. 2018). In the cortical-parcellation-based method, the WMQL tract definitions, which were originally designed for standard single-tensor tractography (Demian Wassermann et al. 2016), were improved following query testing and modification (by NM and colleagues) for the more sensitive UKF by including additional ROIs to constrain fiber selection (Sydnor et al. 2018). In the FC method, false positive fibers in the atlas were annotated and rejected via expert judgment to ameliorate potential subject-specific false positive fibers that were inconsistent with respect to known neuroanatomical knowledge (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018). In addition to the prior anatomical knowledge annotated in the atlas, the fiber clustering method also included a data-driven false positive fiber removal for rejection of fibers that have improbable fiber geometric trajectory (O’Donnell et al. 2017; Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018), similar to the processing applied in many other fiber clustering methods (Côté et al. 2015; Ziyan et al. 2009; Xia et al. 2005). This removal of false positive fibers can be one factor that improves the reproducibility of the wDice score in the FC method.

We also found that the test-retest reproducibility from the three datasets was different. In general, the HCP dataset had higher performance than the other two datasets. This likely relates to the much higher quality of the HCP acquisition (Table 1). It is well known that estimation of diffusion MRI parameters is more robust with a higher number of gradient directions and higher signal-to-noise ratio (Jones 2004; Farrell et al. 2007). The data quality may also explain that the HCP dataset had a larger number of retained white matter parcels than the other two datasets in both the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods (Table 2).

Test-retest reproducibility is considered to be a good indicator of the reliability of white matter parcellation for potential clinical applications, as well as the study of large datasets for neuroscientific research. Having highly reproducible parcellation is a prerequisite for clinical applications such as neurosurgery and neurology (Kristo et al. 2013). Test-retest reproducibility is also important to determine the sensitivity of tractography to reveal pathological abnormalities and changes over time (Besseling et al. 2012). Multiple studies have used test-retest reproducibility to assess predictive power in studying brain longitudinal changes (Keihaninejad et al. 2013; Jovicich et al. 2014; Lin et al. 2013). In our study, we showed a highly reproducible white matter parcellation using the fiber clustering method; thus, we suggested this method could be reproducibly applied for clinical applications and large dataset analysis. These applications can include white matter parcellation for neurosurgical planning (O’Donnell et al. 2017), parcellation of scans from different time points to track white matter changes, and analysis of very large diffusion MRI datasets that will soon become available (L. M. Alexander et al. 2017; Casey et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2017).

Potential future directions and limitations of the current work are as follows. First, the two compared methods produced different numbers of parcels, with different distributions of parcel volumes (though the median parcel volumes were not significantly different). The scale of the white matter parcellation (i.e the number of parcels, or the volume of those parcels) is an important factor in the success of the parcellation for a particular application. Many studies have shown that different parcellation scales can provide a better description of local brain regions (Fan Zhang, Savadjiev, et al. 2018; Cammoun et al. 2012; Hagmann et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2017). The scale of a white matter parcellation also affects the inter-subject parcellation consistency (F. Zhang, Norton, et al. 2017). Future work could include an investigation of different white matter parcellation scales on test-retest reproducibility. Second, the aim of this study was to compare test-retest reproducibility of different white matter parcellation methods on several independently acquired datasets; thus we did not perform any statistical analyses across the different populations. There have been studies that investigate differences of reproducibility measures, e.g. between disease versus healthy populations (Cousineau et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2013) and between data with different acquisitions (Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013), using cortical-parcellation-based strategies. Future work could include applying fiber clustering strategies for such statistical analyses. Third, in the present study, we chose volumetric overlap and FA to investigate white matter parcellation test-retest reproducibility. While these two measures are relatively representative test-retest reproducibility measures and have been used in many related studies (Cousineau et al. 2017; Besseling et al. 2012; O. Ciccarelli et al. 2003; Kristo et al. 2013; Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013; Pfefferbaum, Adalsteinsson, and Sullivan 2003; Vollmar et al. 2010), there are many other measures available, e.g., MD, apparent fiber density (AFD) and number of fiber orientations (NuFO) (Cousineau et al. 2017; Kristo et al. 2013; Kuhn et al. 2016; Papinutto, Maule, and Jovicich 2013). In Supplementary Material 1, we provide additional experimental results from relative difference of MD on whole brain white matter parcellation and anatomical fiber tract parcellation. The results in general agree with our overall finding, i.e., the fiber clustering method generates significantly more reproducible white matter parcellations than the cortical-parcellation-based method. However, we noticed that the performance on MD was slightly different from that on FA. For example, there are more significantly different tracts between the two methods using MD (11, 3, and 20, respectively, in the three datasets) compared to FA (6, 2, and 9, respectively, in the three datasets). This could potentially be related to different levels of fiber specificities of FA and MD. Therefore, a further investigation could be done by including more test-retest reproducibility measures and a comparison between them. Fourth, we performed comparison of the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based methods using a deterministic UKF tractography method, which is highly consistent in tracking fibers in dMRI data from independently acquired populations across ages, health conditions and image acquisitions (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018). However, many other tractography methods (such as probabilistic (Jeurissen et al. 2011), global (Christiaens et al. 2015) and multi-tissue (Jeurissen et al. 2014) fiber tracking methods) potentially could generate improved white matter parcellation test-retest reproducibility. Fifth, in the present study, we compared two fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based strategies that are widely used but relatively traditional approaches. In the past few years, there have been methods designed to improve test-retest reproducibility for constructing cortical-parcellation-based connectomes by including additional pre- and/or post-processing steps, e.g., dilating gray matter regions (Z. Zhang et al. 2018), constructing continuous connectome matrices (Moyer et al. 2017), and filtering out implausible fiber streamlines (Smith et al. 2015). A further study could include comparison of test-retest reproducibility between the fiber clustering and cortical-parcellation-based strategies with advanced processing.

5. Conclusion

Our experimental results in general indicate that the fiber clustering method generates significantly more reproducible white matter parcellations than the cortical-parcellation-based method. However, both methods have high performance when compared to existing studies of reproducibility of fiber tract anatomical parcellation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding provided by the following National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: P41 EB015902, P41 EB015898, R01 MH074794, R01 MH097979, U01 CA199459, and R03 NS088301.

Appendix: Data preprocessing and UKF tractography

For the HCP dataset, we used the already processed dMRI data (following the processing pipeline in (Glasser et al. 2013)). We extracted the b = 3000 s/mm2 shell of 90 gradient directions and all b0 scans (18) for each subject, as applied in our previous studies (O’Donnell et al. 2017; F. Zhang, Kahali, et al. 2017; F. Zhang, Norton, et al. 2017; Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018). Angular resolution is better and more accurate at high b-values such as 3000 (Descoteaux et al. 2007; Ning et al. 2015), and this single shell was chosen for reasonable computation time and memory use when performing tractography. The Freesurfer (version 5.2 was used in the HCP data processing pipeline) segmentation, which had been co-registered to the dMRI space, was directly used.

For the ABIDE-II and the PPMI datasets, we pre-processed the provided raw imaging data using the following steps. DWIConvert (https://github.com/BRAINSia/BRAINSTools) was first applied to convert the original data format (DICOM or NIFTI) to NRRD. Eddy current-induced distortion correction and motion correction were conducted using the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library tool (version 5.0.6) (Jenkinson et al. 2012). To further correct for distortions caused by magnetic field inhomogeneity (which leads to intensity loss and voxel shifts), an EPI distortion correction was performed with reference to the T2-weighted image using the Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTS) (Avants, Tustison, and Song 2009). Because T2-weighted images were not available in all of these datasets (no T2 images were provided in the ABIDE-II, and in the PPMI dataset not all subjects had T2 images), we generated a synthetic T2-weighted image from a T1-weighted image for each subject (T1-weighted images were available for in all datasets) using the T1-weighted to T2-weighted conversion toolbox (https://github.com/pnlbwh/T1toT2conversion). For each subject, a nonlinear registration (registration was restricted to the phase encoding direction) was computed from the b0 image to the synthetic T2-weighted image to make an EPI corrective warp. Then, the warp was applied to each diffusion image. A semi-automated quality control (using in-house developed Matlab scripts) was conducted on all diffusion images. Individuals that had diffusion images with any apparent signal drops were excluded from the analyses. For the remaining subjects, all gradient directions were retained for analysis. We also performed a Freesurfer (version 5.3) segmentation for each subject in these two datasets. Each individual’s Freesurfer segmentation was transformed from T1-weighted space into diffusion corrected (b0) space via nonlinear registration using ANTS.

After obtaining the pre-processed DWI data, we applied the same UKF parameters for all subjects under study, as follows. Tractography was seeded in all voxels within the brain mask where fractional anisotropy (FA) was greater than 0.1. Tracking stopped where the FA value fell below 0.08 or the normalized mean signal (the sum of the normalized signal across all gradient directions) fell below 0.06. The normalized average signal measure was employed to robustly distinguish between white/gray matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) regions. These seeding and stopping thresholds were set slightly below the default values (as used in our previous study (Fan Zhang, Wu, Norton, et al. 2018)) to enable higher sensitivity for fiber tracking, in particular for the subjects (such as children) that might have low white matter anisotropy. Fibers that were longer than 40 mm were retained to avoid any bias towards implausible short fibers (Guevara et al. 2012; Jin et al. 2014; Lefranc et al. 2016)

References

- Albi Angela, Meola Antonio, Zhang Fan, Kahali Pegah, Rigolo Laura, Tax Chantal M. W., Ciris Pelin Aksit, et al. 2018. “Image Registration to Compensate for EPI Distortion in Patients with Brain Tumors: An Evaluation of Tract-Specific Effects.” Journal of Neuroimaging: Official Journal of the American Society of Neuroimaging 28 (2): 173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Andrew L., Lee Jee Eun, Mariana Lazar, Rebecca Boudos, DuBray Molly B., Oakes Terrence R., Miller Judith N., et al. 2007. “Diffusion Tensor Imaging of the Corpus Callosum in Autism.” NeuroImage 34 (1): 61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Lindsay M., Escalera Jasmine, Ai Lei, Andreotti Charissa, Febre Karina, Mangone Alexander, Vega-Potler Natan, et al. 2017. “An Open Resource for Transdiagnostic Research in Pediatric Mental Health and Learning Disorders.” Scientific Data 4 (December): 170181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Bürgel U, Mohlberg H, Uylings HB, and Zilles K. 1999. “Broca’s Region Revisited: Cytoarchitecture and Intersubject Variability.” The Journal of Comparative Neurology 412 (2): 319–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants Brian B., Tustison Nick, and Song Gang. 2009. “Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTS).” The Insight Journal 2: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Mattiello J, and LeBihan D. 1994. “MR Diffusion Tensor Spectroscopy and Imaging.” Biophysical Journal 66 (1): 259–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Pajevic S, Pierpaoli C, Duda J, and Aldroubi A. 2000. “In Vivo Fiber Tractography Using DT-MRI Data.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 44 (4): 625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett Danielle S., and Bullmore Edward T.. 2016. “Small-World Brain Networks Revisited.” The Neuroscientist: A Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry, September 10.1177/1073858416667720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani Matteo, Shah Nadim Jon, Goebel Rainer, and Roebroeck Alard. 2012. “Human Cortical Connectome Reconstruction from Diffusion Weighted MRI: The Effect of Tractography Algorithm.” NeuroImage 62 (3): 1732–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Christian, Michailovich O, Levitt J, Pasternak O, Bouix S, Westin C, and Rathi Yogesh. 2012. “A Unified Tractography Framework for Comparing Diffusion Models on Clinical Scans.” In Computational Diffusion MRI Workshop of MICCAI, Nice, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Yoav, and Hochberg Yosef. 1995. “Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B, Statistical Methodology 57 (1): 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Besseling René M. H., Jansen Jacobus F. A., Overvliet Geke M., Vaessen Maarten J., Braakman Hilde M. H., Hofman Paul A. M., Aldenkamp Albert P., and Backes Walter H.. 2012. “Tract Specific Reproducibility of Tractography Based Morphology and Diffusion Metrics.” PloS One 7 (4): e34125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson Pierre, Lopes Renaud, Leclerc Xavier, Derambure Philippe, and Tyvaert Louise. 2014. “Intra-Subject Reliability of the High-Resolution Whole-Brain Structural Connectome.” NeuroImage 102 Pt 2 (November): 283–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilha Leonardo, Gleichgerrcht Ezequiel, Fridriksson Julius, Rorden Chris, Breedlove Jesse L., Nesland Travis, Paulus Walter, Helms Gunther, and Focke Niels K.. 2015. “Reproducibility of the Structural Brain Connectome Derived from Diffusion Tensor Imaging.” PloS One 10 (8): e0135247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan Colin R., Pernet Cyril R., Gorgolewski Krzysztof J., Storkey Amos J., and Bastin Mark E.. 2014. “Test–retest Reliability of Structural Brain Networks from Diffusion MRI.” NeuroImage 86 (February): 231–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore Ed, and Sporns Olaf. 2009. “Complex Brain Networks: Graph Theoretical Analysis of Structural and Functional Systems.” Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 10 (3): 186–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammoun Leila, Gigandet Xavier, Meskaldji Djalel, Jean Philippe Thiran Olaf Sporns, Do Kim Q., Maeder Philippe, Meuli Reto, and Hagmann Patric. 2012. “Mapping the Human Connectome at Multiple Scales with Diffusion Spectrum MRI.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 203 (2): 386–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Cannonier Tariq, Conley May I., Cohen Alexandra O., Barch Deanna M., Heitzeg Mary M., Soules Mary E., et al. 2018. “The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study: Imaging Acquisition across 21 Sites.” Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 32 (August): 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland Maxime, Girard Gabriel, Bernier Michaël, Fortin David, Descoteaux Maxime, and Whittingstall Kevin. 2017. “On the Origin of Individual Functional Connectivity Variability: The Role of White Matter Architecture.” Brain Connectivity 7 (8): 491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Hu, Wang Yang, Sheng Jinhua, Kronenberger William G., Mathews Vincent P., Hummer Tom A., and Saykin Andrew J.. 2012. “Characteristics and Variability of Structural Networks Derived from Diffusion Tensor Imaging.” NeuroImage 61 (4): 1153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Zhenrui, Tie Yanmei, Olubiyi Olutayo, Rigolo Laura, Mehrtash Alireza, Norton Isaiah, Pasternak Ofer, Rathi Yogesh, Golby Alexandra J., and O’Donnell Lauren J.. 2015. “Reconstruction of the Arcuate Fasciculus for Surgical Planning in the Setting of Peritumoral Edema Using Two-Tensor Unscented Kalman Filter Tractography.” NeuroImage. Clinical 7 (March): 815–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Zhenrui, Tie Yanmei, Olubiyi Olutayo, Zhang Fan, Mehrtash Alireza, Rigolo Laura, Kahali Pegah, et al. 2016. “Corticospinal Tract Modeling for Neurosurgical Planning by Tracking through Regions of Peritumoral Edema and Crossing Fibers Using Two-Tensor Unscented Kalman Filter Tractography.” International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 11 (8): 1475–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaens Daan, Reisert Marco, Dhollander Thijs, Sunaert Stefan, Suetens Paul, and Maes Frederik. 2015. “Global Tractography of Multi-Shell Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Data Using a Multi-Tissue Model.” NeuroImage 123 (December): 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli Olga, Catani Marco, Johansen-Berg Heidi, Clark Chris, and Thompson Alan. 2008. “Diffusion-Based Tractography in Neurological Disorders: Concepts, Applications, and Future Developments.” Lancet Neurology 7 (8): 715–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli O, Parker GJM, Toosy AT, Wheeler-Kingshott CAM, Barker GJ, Boulby PA, Miller DH, and Thompson AJ. 2003. “From Diffusion Tractography to Quantitative White Matter Tract Measures: A Reproducibility Study.” NeuroImage 18 (2): 348–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conturo TE, Lori NF, Cull TS, Akbudak E, Snyder AZ, Shimony JS, McKinstry RC, Burton H, and Raichle ME. 1999. “Tracking Neuronal Fiber Pathways in the Living Human Brain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (18): 10422–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté Marc-Alexandre, Garyfallidis Eleftherios, Larochelle Hugo, and Descoteaux Maxime. 2015. “Cleaning up the Mess: Tractography Outlier Removal Using Hierarchical QuickBundles Clustering.” Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine … Scientific Meeting and Exhibition. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Scientific Meeting and Exhibition. http://scil.dinf.usherbrooke.ca/wp-content/papers/cote-etal-ismrm15.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau Martin, Jodoin Pierre-Marc, Morency Félix C., Rozanski Verena, Marilyn Grand’Maison Barry J. Bedell, and Descoteaux Maxime. 2017. “A Test-Retest Study on Parkinson’s PPMI Dataset Yields Statistically Significant White Matter Fascicles.” NeuroImage. Clinical 16 (July): 222–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis Emily L., Jahanshad Neda, Toga Arthur W., McMahon Katie L., de Zubicaray Greig I., Martin Nicholas G., Wright Margaret J., and Thompson Paul M.. 2012. “Test-Retest Reliability of Graph Theory Measures of Structural Brain Connectivity.” Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention: MICCAI … International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 15 (Pt 3): 305–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santis De, Silvia Mark Drakesmith, Bells Sonya, Assaf Yaniv, and Jones Derek K.. 2014. “Why Diffusion Tensor MRI Does Well Only Some of the Time: Variance and Covariance of White Matter Tissue Microstructure Attributes in the Living Human Brain.” NeuroImage 89 (April): 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descoteaux Maxime, Angelino Elaine, Fitzgibbons Shaun, and Deriche Rachid. 2007. “Regularized, Fast, and Robust Analytical Q-Ball Imaging.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 58 (3): 497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan Rahul S., Florent Ségonne Bruce Fischl, Quinn Brian T., Dickerson Bradford C., Blacker Deborah, Buckner Randy L., et al. 2006. “An Automated Labeling System for Subdividing the Human Cerebral Cortex on MRI Scans into Gyral Based Regions of Interest.” NeuroImage 31 (3): 968–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dice Lee R. 1945. “Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association Between Species.” Ecology 26 (3): 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino Adriana, O’Connor David, Chen Bosi, Alaerts Kaat, Anderson Jeffrey S., Assaf Michal, Balsters Joshua H., et al. 2017. “Enhancing Studies of the Connectome in Autism Using the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange II.” Scientific Data 4 (March): 170010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Zhaohua, Gore John C., and Anderson Adam W.. 2003. “Classification and Quantification of Neuronal Fiber Pathways Using Diffusion Tensor MRI.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 49 (4): 716–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Fei, Zhao Tengda, He Yong, and Shu Ni. 2015. “Test-Retest Reliability of Diffusion Measures in Cerebral White Matter: A Multiband Diffusion MRI Study.” Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 42 (4): 1106–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda Jeffrey T., Cook Philip A., and Gee James C.. 2014. “Reproducibility of Graph Metrics of Human Brain Structural Networks.” Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 8 (May): 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essayed Walid I., Zhang Fan, Unadkat Prashin, Rees Cosgrove G, Golby Alexandra J., and O’Donnell Lauren J.. 2017. “White Matter Tractography for Neurosurgical Planning: A Topography-Based Review of the Current State of the Art.” NeuroImage. Clinical 15 (June): 659–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell Jonathan A. D., Landman Bennett A., Jones Craig K., Smith Seth A., Prince Jerry L., van Zijl Peter C. M., and Mori Susumu. 2007. “Effects of Signal-to-Noise Ratio on the Accuracy and Reproducibility of Diffusion Tensor Imaging–derived Fractional Anisotropy, Mean Diffusivity, and Principal Eigenvector Measurements at 1.5T.” Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: JMRI 26 (3): 756–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl Bruce. 2012. “FreeSurfer.” NeuroImage 62 (2): 774–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl Bruce, Salat David H., Busa Evelina, Albert Marilyn, Dieterich Megan, Haselgrove Christian, van der Kouwe Andre, et al. 2002. “Whole Brain Segmentation: Automated Labeling of Neuroanatomical Structures in the Human Brain.” Neuron 33 (3): 341–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, and Dale AM. 1999. “High-Resolution Intersubject Averaging and a Coordinate System for the Cortical Surface.” Human Brain Mapping 8 (4): 272–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garyfallidis Eleftherios, Brett Matthew, Correia Marta Morgado, Williams Guy B., and Nimmo-Smith Ian. 2012. “QuickBundles, a Method for Tractography Simplification.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 6 (December): 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garyfallidis Eleftherios, Côté Marc-Alexandre, Rheault Francois, Sidhu Jasmeen, Hau Janice, Petit Laurent, Fortin David, Cunanne Stephen, and Descoteaux Maxime. 2018. “Recognition of White Matter Bundles Using Local and Global Streamline-Based Registration and Clustering.” NeuroImage 170 (April): 283–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Bao, Guo Lei, Zhang Tuo, Zhu Dajiang, Li Kaiming, Hu Xintao, Han Junwei, and Liu Tianming. 2012. “Group-Wise Consistent Fiber Clustering Based on Multimodal Connectional and Functional Profiles.” Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention: MICCAI International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 15 (Pt 3): 485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser Matthew F., Sotiropoulos Stamatios N., Anthony Wilson J, Coalson Timothy S., Fischl Bruce, Andersson Jesper L., Xu Junqian, et al. 2013. “The Minimal Preprocessing Pipelines for the Human Connectome Project.” NeuroImage 80 (October): 105–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golby Alexandra J., Kindlmann Gordon, Norton Isaiah, Yarmarkovich Alexander, Pieper Steven, and Kikinis Ron. 2011. “Interactive Diffusion Tensor Tractography Visualization for Neurosurgical Planning.” Neurosurgery 68 (2): 496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Gaolang, He Yong, Concha Luis, Lebel Catherine, Gross Donald W., Evans Alan C., and Beaulieu Christian. 2009. “Mapping Anatomical Connectivity Patterns of Human Cerebral Cortex Using in Vivo Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography.” Cerebral Cortex 19 (3): 524–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Shun, Zhang Fan, Norton Isaiah, Essayed Walid I., Unadkat Prashin, Rigolo Laura, Pasternak Ofer, et al. 2018. “Free Water Modeling of Peritumoral Edema Using Multi-Fiber Tractography: Application to Tracking the Arcuate Fasciculus for Neurosurgical Planning.” PloS One 13 (5): e0197056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett Casey, Davis Brad, Jean Remi, Gilmore John, and Gerig Guido. 2006. “Improved Correspondence for DTI Population Studies via Unbiased Atlas Building.” Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention: MICCAI … International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 9 (Pt 2): 260–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara P, Duclap D, Poupon C, Marrakchi-Kacem L, Fillard P, Le Bihan D, Leboyer M, Houenou J, and Mangin J-F. 2012. “Automatic Fiber Bundle Segmentation in Massive Tractography Datasets Using a Multi-Subject Bundle Atlas.” NeuroImage 61 (4): 1083–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann Patric, Kurant Maciej, Gigandet Xavier, Thiran Patrick, Wedeen Van J., Meuli Reto, and Thiran Jean-Philippe. 2007. “Mapping Human Whole-Brain Structural Networks with Diffusion MRI.” PloS One 2 (7): e597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiervang E, Behrens TEJ, Mackay CE, Robson MD, and Johansen-Berg H. 2006. “Between Session Reproducibility and between Subject Variability of Diffusion MR and Tractography Measures.” NeuroImage 33 (3): 867–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Hao, Zhang Jiangyang, van Zijl Peter C. M., and Mori Susumu. 2004. “Analysis of Noise Effects on DTI-Based Tractography Using the Brute-Force and Multi-ROI Approach.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: Official Journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 52 (3): 559–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingalhalikar Madhura, Smith Alex, Parker Drew, Satterthwaite Theodore D., Elliott Mark A., Ruparel Kosha, Hakonarson Hakon, Gur Raquel E., Gur Ruben C., and Verma Ragini. 2014. “Sex Differences in the Structural Connectome of the Human Brain.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (2): 823–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson Mark, Beckmann Christian F., Behrens Timothy E. J., Woolrich Mark W., and Smith Stephen M.. 2012. “FSL.” NeuroImage 62 (2): 782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]