Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

The objective of this study was to longitudinally investigate the trajectory of change in 1H MRS measurements in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers who became symptomatic during follow-up, and to determine the time at which the neurochemical alterations accelerated during disease progression.

METHODS:

We identified 8 MAPT mutations carriers who transitioned from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease during follow up. All participants were longitudinally followed with an average of 7.75 years (range 4–11years) and underwent two or more single voxel 1H MRS examinations from the posterior cingulate voxel, with a total of 60 examinations. The rate of longitudinal change for each metabolite was estimated using linear mixed models. A flex point model was used to estimate the flex time point of the change in slope.

RESULTS:

The decrease in the NAA/mI ratio accelerated 2.09 years prior to symptom onset, and continued to decline. A similar trajectory was observed in the presumed glial marker mI/Cr accelerating 1.86 years prior to symptom onset.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings support the potential use of longitudinal 1H MRS for monitoring the neurodegenerative progression in MAPT mutation carriers starting from the asymptomatic stage.

Keywords: MAPT, converter, MRS, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, longitudinal

Introduction

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is a neurodegenerative disorder with heterogeneous clinical features, characterized by behavioral and language disorders, impaired social and executive dysfunction, and some patients also develop features of motor neuron disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and cortical basal syndrome. It is highly heritable with an autosomal dominant family history in about 30–50% FTLD patients,1 usually associated with mutations of microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene.2 Families with MAPT mutations provide an opportunity to identify biomarkers for early neurodegenerative changes and tracking disease progression starting from asymptomatic stage.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) provides quantitative in vivo assessment of several brain metabolites in a single scan that are associated with early neurodegenerative pathology. 1H MRS measurements from the posterior cingulate gyrus have identified neurochemical abnormalities in both asymptomatic and symptomatic carriers of MAPT mutation.3 A decrease in the neuronal integrity marker N-acetylaspartate (NAA) or NAA to creatine (NAA/Cr) and elevation in possible glial marker myoinositol (mI) or mI to creatine (mI/Cr) have been found in symptomatic patients with FTLD,4 while only elevation in mI/Cr have been found in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers in the posterior cingulate gyrus.3

Longitudinal 1H MRS studies in Alzheimer’s disease demonstrated longitudinal decline in the neuronal integrity marker NAA and elevation in mI,5–7 suggesting serial MRS is a potential biomarker in for following the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. Establishing the trajectory of biomarker changes preceding the clinical disease onset during the asymptomatic stage in MAPT mutation carriers is crucial for assessing the effects of potential therapies that are currently being developed.

The objectives of this study were: (1) to longitudinally investigate the trajectory of change in 1H MRS measurements in MAPT mutations carriers who converted from asymptomatic to symptomatic status; and (2) to determine the time at which the neurochemical changes accelerated during disease progression.

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited from the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) and the Longitudinal Evaluation of Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Subjects (LEFFTDS) studies at the Mayo Clinic site from between August 2006 to July 2017. LEFFTDS is a multi-site study investigating the biomarkers of disease progression in familial FTLD mutation carriers. The current study included participants who screened positive for a mutation in MAPT with no clinical symptoms at baseline, but transitioned from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease during follow-up, which we refer to as converters (n=8; 4 females; median age=41.5). Converters were from 4 individual families with MAPT mutations (4 with N279K, 2 with V337M, 1 with P301L and 1 IVS9–10G>T mutations) with a mean score 29.75 (range 29–30) on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) at the baseline evaluation. All participants were followed prospectively with annual clinical examination at the time of MRI/1H MRS examination, including a medical history review, mental status examination, a neurological examination by a clinician with FTLD expertise and a neuropsychological examination.

None of the participants had structural lesions that could cause cognitive impairment or dementia, such as cortical infarction, subdural hematoma, or tumor, or had concurrent illness that would interfere with cognitive function other than FTLD on baseline and follow-up examinations.

All participants have undergone genetic testing for research and the behavioral neurologists evaluating the participants were blinded to the findings of the genetic testing for research before the phenoconversion. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for participation in the studies, which were approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board.

MRS and MRI

Single voxel (SV) 1H MRS studies were performed at 3T using an 8-channel phased array head coil (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). A 3D high-resolution T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) acquisition with repetition time/echo time/inversion time = 7/3/900 msec, flip angle 8 degrees, in-plane resolution of 1.0 mm, and a slice thickness of 1.2 mm was performed in sagittal plane for voxel positioning. 1H MRS studies were performed using the automated MRS package (PROBE/SV; GE Healthcare). Point resolved spectroscopy sequence with repetition time = 2,000 msec, echo time = 30 msec, 2,048 data points, and 128 excitation was used for the examination.

An 8 cm3 (2×2×2 cm) voxel was placed by trained MRI technologists on a mid-sagittal T1 weighted image, included right and left posterior cingulate gyri and inferior precunei. The anterior border of splenium, the superior border of corpus callosum and the cingulate sulcus were the anatomical landmarks to define the anterior inferior and the anterior superior border of the voxel. Individual voxel placements were visually evaluated by a trained image analyst for quality control. 1H MR spectra from voxels that were not properly placed according to predetermined anatomic landmarks, those with low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), poor water suppression, lipid contamination, wide linewidths or baseline distortions failed the quality control and were excluded. In this study, none of the spectra had to be excluded due to poor quality.

The PROBE’s prescan algorithm automatically adjusts the transmitter and receiver gains and center frequency. The local magnetic field homogeneity is optimized with the 3-plane auto-shim procedure and the flip angle of the third water suppression pulse is adjusted for chemical shift water suppression (CHESS) prior to point-resolved spectroscopy acquisition. Metabolite intensity ratios are automatically calculated using a previously validated algorithm at the end of each PROBE/SV.8,9 1H MRS metabolite ratios that were analyzed for this study included N-acetylaspartate/Creatine (NAA/Cr), myo-inositol (mI)/Cr and NAA/mI based on previous cross-sectional studies in MAPT mutation carriers showing abnormalities in these metabolite ratios.3

Genetic analysis

Analysis of MAPT exons 1, 7 and 9–13 was performed using primers and conditions that were previously published.10 PCR amplicons were purified using the Multiscreen system (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and then sequenced in both directions using Big Dye chemistry following the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems, Froster City, CA). Sequence products were purified using the Montage system (Millipore) before being run on an Applied Biosystem 3730 DNA Analyzer. Sequence data were analyzed using either SeqScape (Applied Biosystem) or Sequencher software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of converters with MAPT mutations were described with means, standard deviations, counts and proportions. We modeled the annual percent change of NAA/Cr, NAA/mI, and mI/Cr ratios using linear mixed effects models with a flex point in the fixed effects. The flex point models allow the regression slopes to change at some time before, at, or after the time of conversion. The models thus have two estimated regression lines, one with the first slope in the early times and one with the second slope at later times, with their point of intersection being the flex point. This flex point was estimated in the models using a dummy variable to shift the estimated line with the second slope up or down, thereby moving the flex point left or right. The specific coding in our models estimated a slope over the entire time, and then a modifier to the slope after the flex point. If the flex point was not significantly different from the time of conversion, we reduced to a more parsimonious model with slope change at the time of conversion. If in addition the slopes before and after the flex point did not differ, we reduced to a model with a single slope over the time span. We used p-values, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to evaluate the models. The mixed models used random intercepts to account for within-subject repeated measures correlations nested in within-family correlations. This allowed for dependence in the repeated measures per subject, and also dependence in family members. Families were assumed to be independent from each other. Because of the sample size restrictions, we were only able to use random intercepts in these models. Inclusion of random slopes and flex points would result in gross overfitting of the models, and non-convergence.

Results

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the converters. The converters were followed for a median of 8.2 years (range 3.8 to 10.7 years) and had at least two 1H MRS scans from the posterior cingulate gyrus, with a total of 60 1H MRS examinations included in 8 participants. 1H MRS acquisitions from the posterior cingulate voxel past the quality control assessment and were successful for the quantification of metabolite ratios in all participants.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline.

| MAPT mutation carriers | |

|---|---|

| Female, number (%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| Education, year | 15 (1) |

| Age at MRI scan, year | 41 (6) |

| MMSE | 30 (0.46) |

| NPI total | 1 (1) |

| DRS total MOANS | 12 (2) |

| AVLT delay recalled MOANS | 12 (3) |

| NAA/Cr ratio | 1.67 (0.06) |

| mI/Cr ratio | 0.54 (0.04) |

| NAA/mI ratio | 3.11 (0.3) |

Data shown are number (%) or mean (standard deviation).

MRI = magnetic resonance image; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examinations; NPI = Neuropsychiatric Inventory; DRS = Dementia rating scale; MOANS = Mayo’s Older Americans Normative Studies; AVLT = Auditory-verbal learning test; NAA = N-acetylaspartate; Cr = creatine; mI = myo-inositol.

The median age of symptom onset was 45.5 years with a range of 36 – 58 years. At the time of conversion, all participants were classified as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), with two later developing behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), two developing mixed bvFTD and PSP (Richardson’s syndrome), one developing bvFTD with Parkinsonism, and three remaining as MCI.

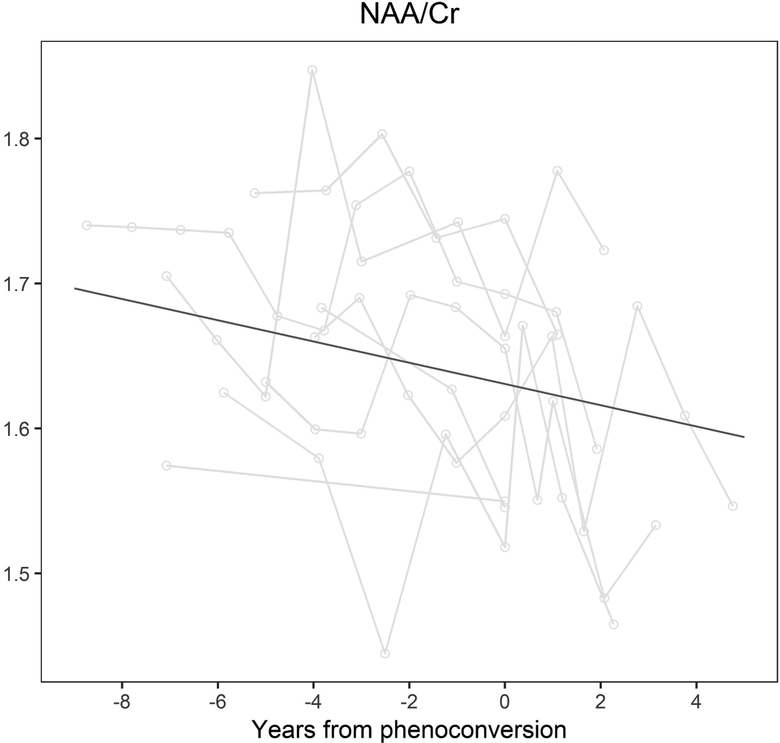

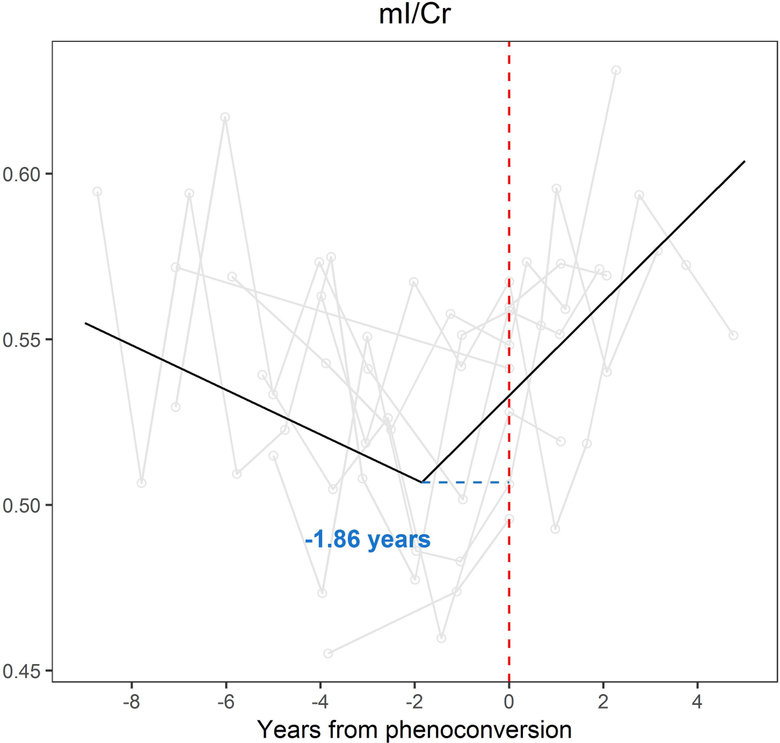

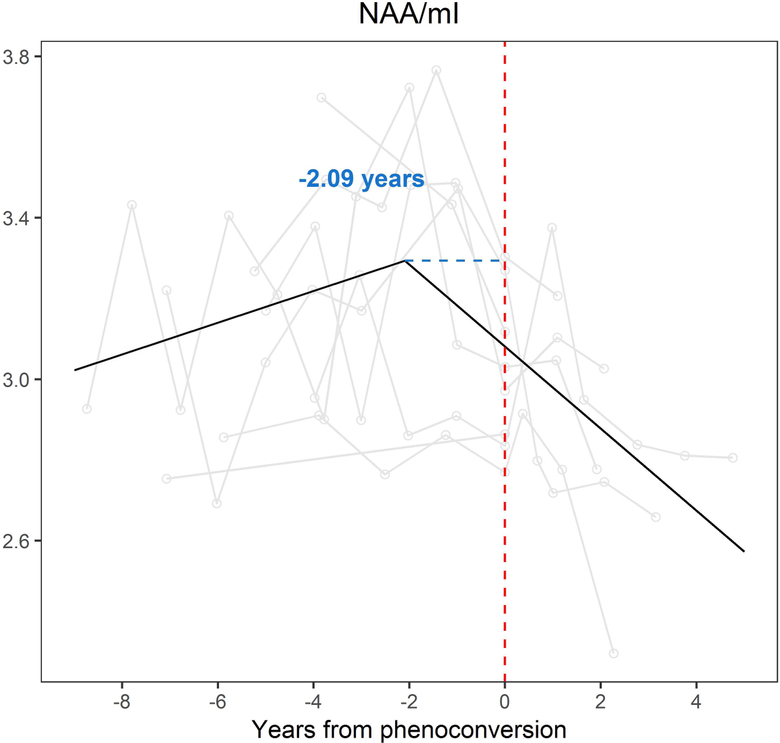

The flex point model demonstrated a change in slope in mI/Cr ratios (p=0.008) and NAA/mI (p =0.005) (Figure 1). Representative longitudinal spectra from a converter with MAPT mutation are shown in Figure 2. The increase in the presumed glial marker mI/Cr ratio accelerated 1.86 years prior to symptom onset, and continued to increase with the slope of 0.04 per year after the flex point (CI: 0.01, 0.07, p=0.008). A similar trajectory of decrease in the NAA/mI ratio accelerated 2.09 years prior to symptom onset, and continued to decline with a slope of −0.30 per year (CI: −0.50, −0.10, p=0.005). No evidence of longitudinal change was observed in NAA/Cr during the follow-up period (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The flex point model for 1H MRS metabolite ratios.

In the x axis, 0 indicates the actual age of symptom onset for converters with MAPT mutation. The metabolite ratios are in the y axis. The black line shows the predicted values calculated from the flex-point models. NAA/Cr ratios did not have a “flex-point” during the follow-up time window (A). The increase of the presumed glial marker mI/Cr accelerated in 1.86 years prior to symptom onset, and continued to increase in time (B). A similar trajectory of decrease was observed the neuronal marker NAA/mI ratio 2.09 years prior to symptom onset (C). NAA = N-acetylaspartate; Cr = creatine; mI = myo-inositol.

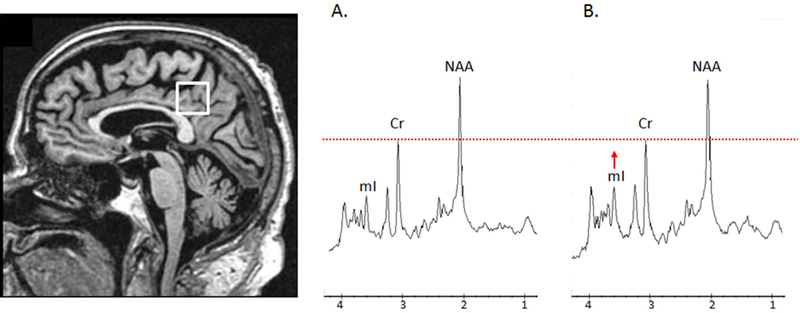

Figure 2.

Voxel location and representative 1H magnetic resonance spectra from a converter with MAPT mutation carrier

Posterior cingulate voxel is placed on a mid-sagittal 3D T1-weighted image (left). Example of 1H MRS for a converter with MAPT mutation at 2 years before symptom onset (A) and 2 year after symptom onset (B). The spectra are scaled to the creatine (Cr) peak as indicated with the dotted red line. During follow-up, the myoinositol (mI) peak is elevated from 2 years before symptom onset with mI/Cr ratio of 0.48 (A) to 2 years after symptom onset with mI/Cr ratio of 0.57 (B).

Table 2.

Annual change of metabolite ratios on flex point models in converters with MAPT mutations.

| NAA/Cr | mI/Cr | NAA/mI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates (95% CI) | Estimates (95% CI) | Estimates (95% CI) | |

| Intercept | 1.66 (1.60, 1.72)*** | 0.49 (0.46, 0.53)*** | 3.37 (3.14, 3.62)*** |

| Overall slope | −0.0003 (−0.01, 0.01) | −0.007 (−0.01, −0.002)* | 0.04 (0.003, 0.08)* |

| Slope modifier after the flex point | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.006) | 0.02 (0.006, 0.03)* | −0.10 (−0.18, −0.02)* |

| Flex point dummy variable | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07)** | −0.30 (−0.50, −0.10)** |

This flex point was estimated in the models using a dummy variable to shift the estimated line with the second slope up or down, thereby moving the flex point left or right. The specific coding in our models estimated a slope over the entire time, and then a modifier to the slope after the flex point. The mixed models used random intercepts to account for within-subject repeated measures correlations nested in within-family correlations.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001;

CI = confidence interval; Abbreviations: NAA = N-acetylaspartate; Cr = creatine; mI = myo-inositol.

Discussion

In current study, we report the trajectory of serial 1H MRS metabolite ratio changes from the posterior cingulate voxel in MAPT mutation carriers who converted from the asymptomatic to symptomatic disease during the longitudinal study. Findings were characterized by a trajectory of increasing mI/Cr and decreasing NAA/mI ratios that begin approximately 2 years prior to symptom onset. Our study extends upon prior cross-sectional findings of elevated mI/Cr and decreased NAA/mI in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers.3

One of the key findings in our study is the accelerated changes in mI/Cr and NAA/mI that occurred in approximately 2 years prior to symptom onset, suggesting a change in the trajectory of 1H MRS metabolite ratios prior to symptom onset. Our findings are consistent with the trajectories reported in a recent longitudinal study of converters with MAPT and GRN mutations, demonstrating that loss of white matter integrity and grey matter volume were present 2 years before symptom onset.11 In addition, previous cross-sectional studies in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers report presence of 1H MRS metabolite ratio abnormalities,3 grey matter atrophy,12 loss of white matter integrity13 and functional connectivity14 with range of 5 to 30 years before the estimated age of symptom onset. It should be noted that the cross-sectional studies estimated the age of onset by the information available from the carriers of the MAPT mutation type. Heterogeneity in symptom onset is a common feature across different mutations and within individuals from the same family. On the other hand, in the current study we were able to demonstrate the change in the trajectory of 1H MRS metabolite ratios with respect to the actual time of symptom onset during a longitudinal evaluation.

We utilized the flex-point model by using the multi-point 1H MRS datasets to determine when the change in the trajectory of 1H MRS metabolites occurred with respect to the time of symptom onset. Flex-point models have been used to model atrophy rates in preclinical sporadic and familiar Alzheimer’s disease.15,16 However, no prior studies have used flex-point models in MAPT mutation carriers, making it difficult to compare estimates. Our findings suggest that 1H MRS is a useful biomarker for tracking of disease progression starting from the asymptomatic stage.

In agreement with earlier cross-sectional 1H MRS studies in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers3, converters with MAPT mutations had increasing mI/Cr ratio in posterior cingulate gyrus prior to symptom onset that continued after the age of symptom onset. MI is present in glial cells17 and thought to be related with glial proliferation and astrocytic and microglial activation.18,19 Elevated mI was reported in both symptomatic and asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers in the posterior cingulate gyrus voxel.3 Elevated mI is also a common feature of MCI and mild AD even with normal NAA/Cr20–23 and associated with higher amyloid-β burden in both cognitively unimpaired individuals24,25 and those with preclinical AD.26 The posterior cingulate gyrus metabolite alterations starting from the asymptomatic stage is characterized by increasing presumed glia marker mI/Cr, followed by decreased NAA/Cr later, may suggest a period of reactive astrocytosis in MAPT mutation carriers.

In the current study, decreasing NAA/mI ratios in converters with MAPT mutation was mainly driven by increasing mI/Cr ratios, since the slope of the change in neuronal marker NAA/Cr ratios was not different from zero and did not have a “flex-point” during the follow-up time window. A similar profile characterized by elevated mI/Cr ratio without NAA/Cr ratio change, are reported not only in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers, but also in presymptomatic carriers of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) or presenilin 1 (PS1),27 indicating elevation in mI/Cr precedes a decrease in NAA/Cr in posterior cingulate gyrus voxel during the progression of neurodegenerative dementia. The similar pattern of metabolite abnormalities between the MAPT mutation carriers and presymptomatic AD with PS1 and APP mutations suggest that the 1H MRS changes from posterior cingulate voxel may be early markers of the neurodegenerative pathology in familial neurodegenerative dementias with proteinopathies caused by a variety of different mutations.3 However, we have recently demonstrated that the neuronal marker NAA/Cr28–30 from media frontal lobe voxel is decreased in asymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers,31 suggesting 1H MRS metabolite alterations may vary by region. Frontal lobes are one of the earliest brain regions involved with neurodegeneration and cortical atrophy in MAPT mutation carriers.32 The limbic pathways are involved as MAPT mutation carriers become symptomatic.33,34

A strength of our study was that the serial 1H MRS scans were collected over 10 years, which made the tracking of the disease progression from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease possible. However, the relatively small number of converters was still a limitation. Further assessment in a larger cohort could clarify whether our results are generalizable. Furthermore, data collected from the other brain regions such as the frontal lobes may provide further information on the regional distribution of neurodegenerative pathology, which may be present in the frontal lobes earlier than the posterior cingulate gyrus. In addition, using the absolute quantification of metabolite concentrations rather than the metabolite ratios from 1H MRS data and utilizing more advanced acquisition methods to quantify metabolites such as glutamine may provide more information about the mechanisms of metabolite changes associated with MAPT mutations in the future.

In conclusion, our data indicate an accelerated change in the 1H MRS metabolite ratios in MAPT mutation carriers as they transition from asymptomatic to symptomatic disease. Our findings support the utilization of longitudinal 1H MRS as a potential biomarker for monitoring the neurodegenerative disease progression in MAPT mutation carriers starting from the asymptomatic stage, which may have implications for estimating efficacy in future disease-modifying trials.

Acknowledgements and Disclosure:

This work is supported by grants U01 AG045390, U54 NS092089, U24 AG021886, U01 AG016976 and R01 AG 40042. We extend our appreciation to the staff of all centers, and particularly to our patients and their families for their participation in this protocol.

Q. Chen reports no disclosures.

BF. Boeve has served as an investigator for clinical trials sponsored by GE Healthcare and Axovant. He receives royalties from the publication of a book entitled Behavioral Neurology Of Dementia (Cambridge Medicine, 2009, 2017). He serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Tau Consortium. He receives research support from NIH, the Mayo Clinic Dorothy and Harry T. Mangurian Jr. Lewy Body Dementia Program and the Little Family Foundation.

N. Tosakulwong reports no disclosures.

T. Lesnick reports no disclosures.

D. Brushaber reports no disclosures.

C. Dheel reports no disclosures.

J. Fields receives research support from NIH.

L. Forsberg receives research support from NIH.

R. Gavrilova receives research support from NIH.

D. Gearhart reports no disclosures.

D. Haley reports no disclosures.

JL. Gunter reports no disclosures.

J. Graff-Radford receives research support from the NIH.

D. Jones receives research support from NIH and the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics.

D. Knopman serves on the DSMB of the DIAN-TU study, is a site PI for clinical trials

N. Graff-Radford receives royalties from UpToDate, has participated in multicenter therapy studies by sponsored by Biogen, TauRx, AbbVie, Novartis and Lilly. He receives receives research support from NIH.

R. Kraft reports no disclosures.

M. Lapid reports no disclosures.

R. Rademakers receives research funding from NIH and the Bluefield Project to Cure Frontotemporal Dementia.

ZK. Wszolek is partially supported by the NIH/NINDS P50 NS072187, NIH/NIA (primary) and NIH/NINDS (secondary) 1U01AG045390–01A1, Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, the gifts from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch, The Sol Goldman Charitable Trust, and Donald G. and Jodi P. Heeringa.

H. Rosen has received research support from Biogen Pharmaceuticals, has consulting agreements with Wave Neuroscience and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and receives research support from NIH.

AL. Boxer receives research support from NIH, the Tau Research Consortium, the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration, Bluefield Project to Cure Frontotemporal Dementia, Corticobasal Degeneration Solutions, the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation and the Alzheimer’s Association. He has served as a consultant for Aeton, Abbvie, Alector, Amgen, Arkuda, Ionis, Iperian, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Samumed, Toyama and UCB, and received research support from Avid, Biogen, BMS, C2N, Cortice, Eli Lilly, Forum, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and TauRx.

K. Kantarci serves on the data safety monitoring board for Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc. She receives research funding from the NIH, Alzheimer’s Drug and Discovery Foundation and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly.

References

- 1.Rohrer JD, Warren JD. Phenotypic signatures of genetic frontotemporal dementia. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:542–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingram EM, Spillantini MG. Tau gene mutations: dissecting the pathogenesis of FTDP-17. Trends Mol Med 2002;8:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarci K, Boeve BF, Wszolek ZK, et al. MRS in presymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers: a potential biomarker for tau-mediated pathology. Neurology 2010;75:771–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst T, Chang L, Melchor R, Mehringer CM. Frontotemporal dementia and early Alzheimer disease: differentiation with frontal lobe H-1 MR spectroscopy. Radiology 1997;203:829–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schott JM, Frost C, MacManus DG, et al. Short echo time proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal multiple time point study. Brain 2010;133:3315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarci K, Weigand SD, Petersen RC, et al. Longitudinal 1H MRS changes in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2007;28:1330–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waragai M, Moriya M, Nojo T. Decreased N-acetyl aspartate/myo-inositol ratio in the posterior cingulate cortex shown by magnetic resonance spectroscopy may be one of the risk markers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A 7-year follow-up study. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;60:1411–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb PG, Sailasuta N, Kohler SJ, et al. Automated single-voxel proton MRS: technical development and multisite verification. Magn Reson Med 1994;31:365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soher BJ, Hurd RE, Sailasuta N, Barker PB. Quantitation of automated single-voxel proton MRS using cerebral water as an internal reference. Magn Reson Med 1996;36:335–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, et al. Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 1998;393:702–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiskoot LC, Panman JL, Meeter LH, et al. Longitudinal multimodal MRI as prognostic and diagnostic biomarker in presymptomatic familial frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2019;142:193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohrer JD, Nicholas JM, Cash DM, et al. Presymptomatic cognitive and neuroanatomical changes in genetic frontotemporal dementia in the Genetic Frontotemporal dementia Initiative (GENFI) study: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:253–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiskoot LC, Bocchetta M, Nicholas JM, et al. Presymptomatic white matter integrity loss in familial frontotemporal dementia in the GENFI cohort: A cross-sectional diffusion tensor imaging study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018;5:1025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dopper EG, Rombouts SA, Jiskoot LC, et al. Structural and functional brain connectivity in presymptomatic familial frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2014;83:e19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younes L, Albert M, Miller MI, Team BR. Inferring changepoint times of medial temporal lobe morphometric change in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin 2014;5:178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinnunen KM, Cash DM, Poole T, et al. Presymptomatic atrophy in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: A serial magnetic resonance imaging study. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glanville NT, Byers DM, Cook HW, Spence MW, Palmer FB. Differences in the metabolism of inositol and phosphoinositides by cultured cells of neuronal and glial origin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1989;1004:169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brand A, Richter-Landsberg C, Leibfritz D. Multinuclear NMR studies on the energy metabolism of glial and neuronal cells. Dev Neurosci 1993;15:289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada T, McGeer E, Schelper R, et al. Histological and biochemical pathology in a family with autosomal dominant Parkinsonism and dementia. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 1993;2:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantarci K, Jack CR Jr., Xu YC, et al. Regional metabolic patterns in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A 1H MRS study. Neurology 2000;55:210–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catani M, Cherubini A, Howard R, et al. (1)H-MR spectroscopy differentiates mild cognitive impairment from normal brain aging. Neuroreport 2001;12:2315–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheikh-Bahaei N, Sajjadi SA, Manavaki R, et al. Positron emission tomography-guided magnetic resonance spectroscopy in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2018;83:771–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Alexander GE, Chang L, et al. Brain metabolite concentration and dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease: a (1)H MRS study. Neurology 2001;57:626–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nedelska Z, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, et al. (1)H-MRS metabolites and rate of beta-amyloid accumulation on serial PET in clinically normal adults. Neurology 2017;89:1391–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray ME, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, et al. Early Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology detected by proton MR spectroscopy. J Neurosci 2014;34:16247–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voevodskaya O, Sundgren PC, Strandberg O, et al. Myo-inositol changes precede amyloid pathology and relate to APOE genotype in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2016;86:1754–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godbolt AK, Waldman AD, MacManus DG, et al. MRS shows abnormalities before symptoms in familial Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006;66:718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bates TE, Strangward M, Keelan J, et al. Inhibition of N-acetylaspartate production: implications for 1H MRS studies in vivo. Neuroreport 1996;7:1397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in AD. Neurology 2001;56:592–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petroff OA, Errante LD, Kim JH, Spencer DD. N-acetyl-aspartate, total creatine, and myo-inositol in the epileptogenic human hippocampus. Neurology 2003;60:1646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q, Boeve BF, Brushaber D, et al. Frontal lobe 1H MR Spectroscopy in asymptomatic and symptomatic MAPT mutation carriers. Neurology 2019; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr., Boeve BF, et al. Voxel-based morphometry patterns of atrophy in FTLD with mutations in MAPT or PGRN. Neurology 2009;72:813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahoney CJ, Simpson IJ, Nicholas JM, et al. Longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging in frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol 2015;77:33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elahi FM, Marx G, Cobigo Y, et al. Longitudinal white matter change in frontotemporal dementia subtypes and sporadic late onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin 2017;16:595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]