Abstract

Objective:

To assess the safety of, and subsequent allergy documentation associated with, an antimicrobial stewardship intervention consisting of test dose challenge procedures prompted by an electronic guideline for hospitalized patients with reported beta-lactam allergies.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting:

Large healthcare system consisting of two academic and three community acute care hospitals (April 2016-December 2017).

Methods:

We evaluated beta-lactam antibiotic test dose outcomes, including adverse drug reactions (ADRs), hypersensitivity reactions (HSRs), and electronic health record (EHR) allergy record updates. HSR predictors were examined using a multivariable logistic regression model. Modification of the EHR allergy record after test doses considered relevant allergy entries added, deleted, and/or specified.

Results:

We identified 1,046 test doses: 809 (77%) to cephalosporins, 148 (14%) to penicillins, and 89 (9%) to carbapenems. Overall, 78 patients (7.5%; 95%CI 5.9% to 9.2%) had signs or symptoms of an ADR, with 40 (3.8%; 95%CI 2.8% to 5.2%) confirmed HSRs. Most HSRs occurred at the second (i.e., full dose) step (68%) and required no treatment beyond drug discontinuation (58%); 3 HSR patients were treated with intramuscular epinephrine. Reported cephalosporin allergy history was associated with an increased odds of HSR (OR 2.96 [95% CI 1.34 to 6.58]). Allergies were updated for 474 (45%) patients, with records specified (82%), deleted (16%), and added (8%).

Conclusion:

This antimicrobial stewardship intervention using beta-lactam test dose procedures was safe. 3.8% of patients with beta-lactam allergy histories had an HSR; cephalosporin allergy histories conferred a 3-fold increased risk. Encouraging EHR documentation might improve this safe and practical acute care antibiotic stewardship tool.

Keywords: policy, guideline, stewardship, adverse drug reaction, hypersensitivity, allergy, beta-lactam, drug, allergy, penicillin, test dose, graded challenge, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Beta-lactam antibiotic allergies, reported by up to 15% of hospitalized patients, impact acute care antibiotic prescribing.1,2 Cephalosporins, antibiotics important to the treatment of common inpatient infections, are inconsistently prescribed to patients reporting penicillin allergies despite low cross-reactivity.3-5 Alternatives to beta-lactam antibiotics may be less effective,4,6 and can lead to adverse sequelae for patients, most notably healthcare-associated infections such as Clostridioides difficile infection.7,8

The majority of patients with a documented penicillin allergy do not have clinically significant hypersensitivity and can be safely treated with penicillins and other beta-lactams.9 While penicillin allergy evaluation is encouraged by antibiotic stewardship guidelines,10 penicillin skin testing (PST) is operationally challenging in acute care settings.11,12 Further, many of the antibiotics generally used in hospitalized patients after a negative PST can be administered safely without preceding PST by a full dose or test dose challenge.13-15

The Partners HealthCare System (PHS) guideline for inpatients with beta-lactam allergy histories is an antibiotic stewardship tool that includes penicillin and cephalosporin hypersensitivity pathways that direct PST when institutionally available and needed (i.e., patients reporting IgE-mediated allergy symptoms to a penicillin who require a penicillin or cross-reactive cephalosporin), but encourages direct full dose and test dose (i.e., standardized 2-step graded) drug challenges. Prior to this study, our results demonstrated that the guideline safely increased beta-lactam antibiotic use at two academic medical centers.12,14-16 In this study, we sought to further assess the safety of guideline-directed beta-lactam antibiotic test doses after implementation of the computerized guideline throughout five acute care PHS hospitals with varied resources.

METHODS

Computerized guideline with optional clinical decision support

We developed beta-lactam hypersensitivity pathways in 2013 at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), which were modified and studied prospectively at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH).12,14,16 All pathways were implemented as hospital guidelines with electronic health record (EHR) support throughout PHS acute care sites in 2016 (Supplemental Table 1).15

Study Design Overview

We identified all PHS beta-lactam antibiotic test doses performed from April 2016 through December 2017.15 While beta-lactam test doses were not performed at community hospital sites prior to April 2016, test doses at academic sites prior to guideline adoption occurred exclusively at the direction of an allergist. Beta-lactam antibiotic test doses reviewed included those performed with and without preceding PST; PST was available at three sites by an Allergy/Immunology consultation. All patients receiving one or more test dose challenge had their EHR reviewed by PHS housestaff, with data entry and maintenance supported by Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) hosted by PHS.17

Data Definitions and Outcomes

EHR-abstracted data included characteristics of the test dose (drug, hospital, ordering clinician, patient care service, Allergy/Immunology consultation use, PST use, test dose timing, length of stay) and patient characteristics (demographics, allergy history). Historical penicillin and cephalosporin reactions were recorded. Reactions were grouped, considering itching, flushing, rash, and hives as non-severe cutaneous reactions; bronchospasm, shortness of breath, wheezing, anaphylaxis, angioedema, swelling, syncope, arrhythmia, hypotension, dizziness, and positive skin testing were considered severe IgE histories. Other EHR drug allergies were recorded.

The primary outcome was a hypersensitivity reaction (HSR) resulting from a beta-lactam antibiotic test dose. PHS housestaff reviewers recorded reaction details including timing/onset, test dose step, symptoms/presentation, treatment, and clinical context for all possible reactions. Allergy specialist co-investigators (KGB, PGW, JTH, ARW) determined if the signs and/or symptoms were consistent with an HSR. All reactions not consistent with HSRs were considered adverse drug reactions (ADRs). For all HSRs, allergy specialists determined if there were objective findings present and whether the pathways were followed correctly. Confirmed HSRs were grouped: non-severe cutaneous reactions included itching, flushing, rash, tingling, and urticaria; severe IgE reactions included angioedema, swelling, bronchospasm, wheezing, hypotension, and anaphylaxis; and severe delayed immunologic reactions included organ-specific reactions and severe cutaneous adverse reactions. We assessed HSRs overall, by drug class, and separately considered only direct challenges (i.e., challenges performed without prior PST).

Modification of the EHR allergy record after test dose was determined by assessing if the allergy module had a relevant allergy entry added, deleted, and/or specified (i.e., additional detail was included).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics such as numbers with frequencies and medians with interquartile ranges. Univariable comparisons were made with chi-squared and Kruskal Wallis tests. Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using exact (i.e., Clopper Pearson) methods. HSR and ADR predictors were identified using multivariable logistic regression models and we reported adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CI. Selection of variables to include in multivariable models involved a priori knowledge of variable association with outcome. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Test Dose Characteristics

From April 2016 through December 2017, 1,046 test doses to beta-lactams were administered to 942 patients across five PHS hospitals (Table 1). Test dose procedures were performed to penicillins (n=148), cephalosporins (n=809), and carbapenems (n=89). Test doses were performed largely at academic sites (83%) by housestaff (59%). The most common service performing test dose procedures was internal medicine (45%).

Table 1.

Test dose and patient characteristics

| Test Dose Characteristics* | n=1,046 |

|---|---|

| Beta-lactam drug class | |

| Penicillin | 148 (14) |

| Cephalosporin | 809 (77) |

| Carbapenem | 89 (9) |

| Hospital type | |

| Academic† | 867 (83) |

| Community‡ | 179 (17) |

| Ordering provider | |

| Housestaff | 621 (59) |

| Physician assistant | 144 (14) |

| Attending physician | 142 (14) |

| Nurse practitioner | 120 (12) |

| Unknown | 19 (2) |

| Service | |

| Internal medicine¶ | 469 (45) |

| Emergency department | 131 (13) |

| Surgery¶ | 126 (12) |

| Oncology | 111 (11) |

| Intensive care | 110 (11) |

| Cardiology¶ | 24 (2) |

| Neurology¶ | 16 (2) |

| Obstetrics/gynecology¶ | 13 (1) |

| Pediatrics¶ | 11 (1) |

| Unknown | 35 (3) |

| Allergy/Immunology consultation | 96 (9) |

| Penicillin skin test performed | 38 (4) |

| Days in hospital prior to test dose, Med [IQR] | 2 [1, 4] |

| Length of stay, Med [IQR] | 10 [5, 19] |

| Patient Characteristics * | n=942 |

| Female | 612 (65) |

| Age at admission, Med [IQR] | 64 [51, 75] |

| Allergy to penicillin | 900 (96) |

| Penicillin reaction§ | |

| Non-severe cutaneous** | 453 (48) |

| Severe IgE†† | 185 (20) |

| Allergy to cephalosporin | 273 (29) |

| Cephalosporin reaction‡ ‡ | |

| Non-severe cutaneous ¶¶ | 164 (17) |

| Severe IgE*** | 42 (5) |

| Other drug allergy | |

| Sulfonamide antibiotics | 254 (27) |

| Opioids | 170 (18) |

| Fluoroquinolones | 128 (14) |

| Macrolides | 106 (11) |

Number (%) unless otherwise specified;

MGH performed 713 and BWH performed 154;

NWH performed 89, NSMC performed 80, and BWF performed 10;

Non-intensive care;

Numbers do not sum because patients can have more than one reaction. Reactions also included 214 other reactions and 197 with unknown reactions.

Non-severe cutaneous reactions to penicillin included rash (n=266), hives (n=190), itching (n=35), and flushing (n=2);

Severe IgE reactions to penicillin included anaphylaxis (n=78), angioedema (n=48), swelling (n=40), shortness of breath (n=21), bronchospasm (n=6), wheezing (n=6), syncope (n=5), dizziness (n=3), and tested positive (n=1);

Numbers do not sum because patients can have more than one reaction. Reactions also included 790 other reactions and 50 unknown reactions.

Non-severe cutaneous reactions to cephalosporins included rash (n=109), hives (n=45), itching (n=19), and flushing (n=2);

Severe IgE reactions to cephalosporins included anaphylaxis (n=18), angioedema (n=9), swelling (n=8), shortness of breath (n=4), hypotension (n=2), arrhythmia (n=2), and wheezing (n=1).

Abbreviations: Med, median; IQR, interquartile range; Ig, immunoglobulin; MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; BWH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; NWH, Newton Wellesley Hospital; NSMC, North Shore Medical Center; BWF, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital.

Allergy/Immunology was consulted for 96 (9%) of test dose challenges administered, more often for penicillin test doses (19%) than for carbapenem test doses (16%) and cephalosporins (7%, p < 0.001). PST prior to the test dose was performed in 38 (4%) patients, most commonly prior to penicillin test doses (13%), compared to cephalosporins test doses (2%), and carbapenem test doses (0%, p< 0.001).

Patients were in the hospital a median of 2 days prior to their test dose [IQR 1 day, 4 days]; patients received penicillin test doses later in the hospitalization (3 days [IQR 1 day, 7 days]) than patients who received cephalosporin (2 days [IQR 1 day, 4 days]) or carbapenem test doses (2 days [IQR 1 day, 6 days], p=0.003). Overall median length of stay was 10 days [IQR 5 days, 19 days] for patients receiving test doses.

Patient Characteristics

Patients receiving test doses were female (65%) with median age of 64 years [IQR 51 years, 75 years]. Patients receiving test doses had penicillin allergy histories (96%); 29% had cephalosporin allergy histories. Penicillin allergy histories included non-severe cutaneous reactions (48%) and severe IgE-mediated reactions (20%). Cephalosporin allergy histories included non-severe cutaneous reactions (17%) and severe IgE mediated reactions (5%).

Adverse and Hypersensitivity Reactions

There were 78 (7.5%, 95%CI 5.9% to 9.2%) ADRs, of which 40 (3.8%, 95%CI 2.8% to 5.2%) were HSRs and 38 (3.6%, 95%CI 2.6% to 5.0%) were non-HSRs (e.g., somatic symptoms, intolerances, toxicities).

Most HSRs occurred after 24 hours from the initial test dose (n=16, 40%), but 14 (35%) occurred during the 1-hour test dose observation period (Table 2). HSRs were non-severe cutaneous reactions (n=25, 63%) and symptoms suggestive of severe IgE-mediated reactions (n=10, 25%); severe delayed HSRs (n=3, 8%) were also observed. Most HSRs required no treatment (n=23, 58%). Treatments included antihistamines (n=16, 40%), parenteral corticosteroids (n=3, 8%), and epinephrine (n=3, 8%). Objective findings were present in the majority of HSRs (n=34, 85%). The pathway was interpreted correctly in most cases (n=34, 85%); however, the pathway was not followed correctly for one of the three patients treated with epinephrine.

Table 2.

Hypersensitivity reactions resulting from beta-lactam test dose challenge procedures

| Hypersensitivity Reactions (n=40) | |

|---|---|

| Reaction timing (hrs) | |

| ≤1 hour | 14 (35) |

| > 1 hour to <4 hours | 4 (10) |

| ≥ 4 hours to <24 hours | 2 (5) |

| > 24 hours | 16 (40) |

| Unknown | 4 (10) |

| Symptoms or presentation | |

| Non-severe cutaneous reactions* | 25 (63) |

| Severe IgE reactions† | 10 (25) |

| Severe delayed reaction¶ | 3 (8) |

| Reaction treatment | |

| None | 23 (58) |

| Antihistamines | 16 (40) |

| Parenteral corticosteroids | 3 (8) |

| IM epinephrine | 3 (8) § |

| Albuterol | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 13 (33) |

| Objective findings | 34 (85) |

| Pathway followed and correctly implemented | 34 (85)** |

Includes rash (n=19), itching (n=6), hives (n=2), tingling (n=1). Numbers do not sum because patients can have more than one reaction.

Includes bronchospasm/wheezing (n=5), angioedema/swelling (n=4), hypotension/dizziness (n=3), anaphylaxis (n=1). Numbers do not sum because patients can have more than one reaction.

Includes acute interstitial nephritis (n=1), severe cutaneous adverse reaction (n=1), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (n=1)

All three patients whose HSR required IM epinephrine treatment had cephalosporin test dose challenges. The first patient had a history of urticaria and angioedema to penicillin and developed throat tightness, diffuse pruritus, abdominal pain, and wheezing during the cefepime full dose; IM epinephrine, hydroxyzine, and albuterol led to resolution. The second patient had a history of ampicillin anaphylaxis and received ceftriaxone by test dose and full dose uneventfully, but developed throat tightness when broadened to cefepime for Pseudomonas spp. coverage. Symptoms resolved with IM epinephrine, parenteral steroids, and antihistamines. The third patient had a history of penicillin anaphylaxis and was administered cefoxitin by test dose without prior PST. The patient experienced blurry vision, throat closing, and diffuse pruritus; symptoms resolved with IM epinephrine and diphenhydramine.

Pathway was not followed because: patient was too sick/deemed inappropriate candidate for test dose (n=3), patient had active allergy symptoms (n=2), and algorithm not correctly interpreted (n=1).

Abbreviations: IM, intramuscular; PST, penicillin skin test

An allergy to cephalosporin antibiotics (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.96 [95%CI 1.34 to 6.58]) was associated with an increased odds of HSR (Supplemental Table 2). Female sex (aOR 1.86 [95%CI 1.11 to 3.13]), allergy to cephalosporin antibiotics (aOR 2.49 [95%CI 1.37 to 3.13]), and allergy consultation (aOR 2.42 [95%CI 1.30 to 4.51]) were associated with a significantly increased odds of ADR.

Hypersensitivity Reactions to Direct Test Dose Challenges

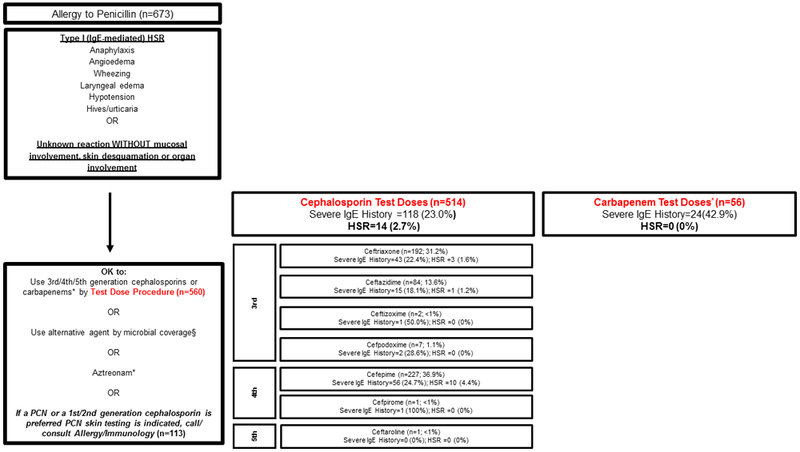

There were 570 penicillin allergy patients with IgE histories or unknown histories directly challenged to cephalosporins (3rd/4th/5th generation) or carbapenems (Figure 1A). Of 514 patients direct challenged to 3rd/4th/5th generation cephalosporins, 14 (2.7%) had HSRs (95%CI 1.5% to 4.5%). The highest HSR rate was with cefepime (4.4%; 95%CI 2.1% to 8.0%). Of 56 patients direct challenged to carbapenems, there were no HSRs.

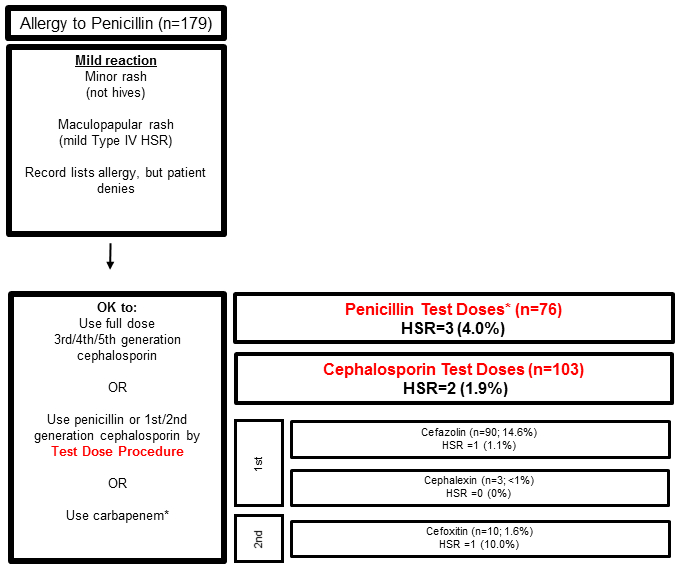

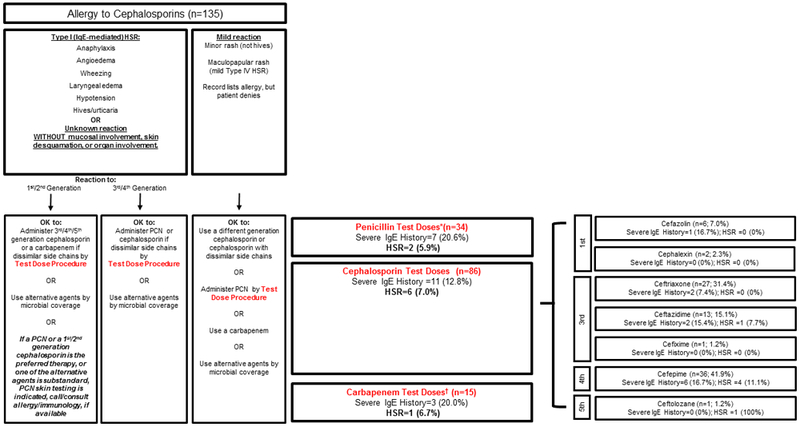

Figure 1.

Reactions from direct beta-lactam antibiotic challenges.

These figures provide insight into beta-lactam HSRs and real-world potential cross-reactivity in acute care patients with well-characterized historical reactions. Patients exclude patients with both penicillin and cephalosporin allergy histories and those who received PST prior to their challenge.

(A) Patients with penicillin allergy histories who received beta-lactam test doses following the penicillin hypersensitivity pathway through the Type I (IgE-Mediated) HSR pathway (n=673)

* Meropenem n=46, imipenem n=6, ertapenem n=4

(B) Patients with penicillin allergy histories who received beta-lactam test doses following the penicillin hypersensitivity pathway through the Mild HSR pathway (n=179).

* Piperacillin/tazobactam n=26, Ampicillin/sulbactam n=21, ampicillin n=13, amoxicillin n=6, penicillin G n=5, nafcillin n=4, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid n=1.

(C) Patients with cephalosporin allergy histories who received beta-lactam test doses following the cephalosporin hypersensitivity pathway (n=135).

* Piperacillin/tazobactam n=18, ampicillin/sulbactam n=8, ampicillin n=5, nafcillin n=2, penicillin G n=1.

† Meropenem n=11, ertapenem n=3, imipenem n=1

Abbreviations: Ig, immunoglobulin; PCN, penicillin; HSR, hypersensitivity reaction; PST, penicillin skin test

We identified 179 patients with mild penicillin reaction histories who received direct test dose challenges. Of 76 patients direct challenged to penicillin, there were 3 HSRs (4.0%; 95%CI 0.8% to 11.1%). Of 103 patients direct challenged to cephalosporins (1st/2nd generation), there were 2 HSRs (1.9%; 95%CI 0.2% to 6.8%) (Figure 1B).

There were 135 patients with cephalosporin allergy histories direct challenged to beta-lactams: 34 to penicillins (2 HSRs; 5.9%; 95%CI 0.7% to19.7%), 86 to cephalosporins (6 HSRs; 7.0%; 95%CI 2.6% to 14.6%), and 15 to carbapenems (1 HSR; 6.7%; 95%CI 0.2% to 32.0%, Figure 1C).

Updating of the Electronic Health Record Allergy Module

Overall, 474/1,046 (45%) patients had their EHR allergy section updated after the beta-lactam antibiotic test dose challenge. Among updated cases, 37 (8%) had an allergy added, 75 (16%) had an allergy deleted, and 390 (82%) had an allergy specified (records could have more than one action). PHS community hospitals updated the EHR more frequently after test doses than PHS academic hospitals (54% vs 43%, p=0.009). Of patients with an Allergy/Immunology consultation (n=96), 59 (61%) had their EHR updated.

DISCUSSION

We implemented a healthcare system-wide guideline to standardize the approach to inpatients with beta-lactam allergy histories as an antibiotic stewardship tool.16 We report on the outcomes of 1,046 beta-lactam antibiotic test dose challenges performed by five diverse acute care hospitals within a single healthcare system, largely without preceding PST (96%). Test doses were predominantly to cephalosporin antibiotics. There was a 7.5% ADR rate and a 3.8% HSR rate. Most HSRs occurred after the full dose step and required no treatment beyond drug discontinuation. There were 10 HSRs consistent with severe IgE-mediated HSRs; 3 were treated with intramuscular epinephrine. Although a cephalosporin allergy history conferred a 3-fold increased HSR risk, HSRs were infrequent to cephalosporins in patients with specific penicillin allergy histories. Allergy records after test doses were not routinely updated.

Hospitalized patients with documented beta-lactam allergies experience inferior outcomes, including treatment failures, adverse events, resistant organisms, and healthcare-associated infections.3,4,6,7,8 To address this problem, hospitals implemented structured allergy histories, PST, and/or comprehensive guidelines.11,12,18,19,20 Because PST can pose operational challenges,12 effective skin testing interventions often select inpatients for PST evaluation based on “need,” such as patients on broad spectrum or non-preferred antibiotics,21-23 or patients referred by Infectious Diseases consultation.18,24 When more inclusive inpatient PST studies were attempted, only 20–33% of eligible inpatients received testing.11-13 Our guideline uses PST only when indicated, given both the allergy history and the desired therapeutic antibiotic, and institutionally available. This guideline applies to all adults, children, and pregnant women in all care units (e.g., emergency departments, medical wards, intensive care units), was previously found to increase beta-lactam use by 80%,12 and in this study of over 1,000 test doses, was safe and feasible in a large, diverse healthcare system. Notably, hospitals without access to inpatient Allergy/Immunology consultation or PST were included, and one such site (Newton Wellesley Hospital [NWH]), contributed almost 10% of the test doses analyzed. NWH’s high test dose volume may have been facilitated by shared MGH housestaff, who had been implementing the guideline at MGH beginning in 2013, three years prior to other sites. While NWH and North Shore Medical Center had consistent clinical champions since program implementation, clinical champion turnover at the Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital may have impacted their test dose volume. Still, each site had successful implementation regardless of allergist access. Given that most US hospitals lack immediate allergist or PST access, our approach may be widely feasible. Indeed, some US hospitals have already adopted this approach and pathways were incorporated into educational materials.19,26,27

In this study, 7.5% of test dose challenges resulted in an ADR. Notably, a nocebo effect (i.e., noxious symptoms from a placebo drug) can occur in patients with prior drug reactions.28,29 A recent US study identified that 10% of patients who thought they were challenged to amoxicillin in an outpatient allergy practice “reacted” to the placebo.30 ADR risk factors included female sex, patients with cephalosporin allergy histories (also a significant HSR risk factor), and Allergy/Immunology consultation. Female sex was previously associated with higher reported drug allergies/intolerances.31,32 Allergy/Immunology consultation was associated with a higher ADR risk by design: consults were indicated after positive challenges in locations with Allergy/Immunology access. The overall ADR frequency is important to consider; all patient-reported symptoms require assessment, and although reassurance may be possible for patients with only subjective symptoms, ADRs after test dose procedures often result in drug discontinuation.

The HSR rate observed in this study was 3.8%, which is similar to our prior study at MGH (3.9%) and comparable to the penicillin HSR rate observed previously by allergy specialists (1.5–2.6%).30,33 Further, all drug administration carries a comparable risk; hospitalized patients with infections have a baseline incidence of antibiotic allergy from 0.5% to 5.0%.34 The HSRs in this study were determined by allergist review and largely supported by objective data. Although one-quarter of HSRs had signs or symptoms suggestive of a severe IgE-mediated HSR, most HSRs required no anti-allergy treatment and only 3 HSR patients were treated with epinephrine. Over one-third (35%) of HSRs were triggered by the test dose, which may have led to those 14 patients having less severe HSRs.

This study provides insight into “real world” beta-lactam cross-reactivity in patients with specified IgE penicillin allergy histories, including patients with severe IgE histories. Prior observational studies of cephalosporins administered to penicillin allergy patients largely excluded patients with higher risk penicillin allergy histories because they were selected out.5 Patients with severe IgE histories have an increased risk of true allergy and beta-lactam cross-reactivity.35,36 Although the later (3rd/4th/5th) generation cephalosporins overall had a low 2.6% HSR rate in patients with IgE penicillin allergy histories, the cefepime HSR rate was 4.4% with a 95%CI up to 8.0%. It remains unclear if later generation cephalosporins need to be initiated with a test dose challenge (many clinicians initiate these cephalosporins in penicillin allergy histories with a full dose). Of 56 carbapenem test doses administered to patients with IgE penicillin allergy histories (including almost half with severe IgE histories), there were no HSRs, which prompts us to consider modification of the penicillin hypersensitivity pathway to indicate that carbapenems be administered by a full dose. For mild penicillin allergy histories, full dose challenges for 1st/2nd generation cephalosporins are a safe modification that would facilitate the use of any cephalosporin for any patient with mild penicillin allergy histories. This change could benefit acute care obstetric and perioperative patients where cefazolin or cefoxitin are indicated.3,37

Allergy to cephalosporin antibiotics was associated with a significant 3-fold increased odds of HSR. Documented cephalosporin allergies may more often be true hypersensitivities that occurred more recently compared to documented penicillin allergies (often “unknown” and/or remote). The cephalosporin hypersensitivity pathway may not be as accurate as the penicillin hypersensitivity pathway in this US acute care populaton.38,39 Although a notable signal, because only 135 patients with cephalosporin allergy histories received direct cephalosporin test doses to date, more data gathering on this approach is needed prior to considering pathway modifications.

Drug allergy documentation is important for quality and safety. However, EHR allergy documentation is often incomplete and inaccurate.40 Inpatient beta-lactam allergy interventions require taking an allergy history that should then be recorded in the EHR. Further, results of skin tests and drug challenges should be specified in the EHR to ensure communication between providers and settings.41,42 We identified that allergy documentation was changed less than half of the time after test doses were performed. Incomplete documentation compromises the effectiveness of any allergy intervention as an antibiotic stewardship tool; beta-lactams may be unnecessarily avoided or a duplication of allergy procedure might be repeated unnecessarily. Targeted alerting to the test dose prescriber may improve allergy documentation after test doses.

Although the guideline can recommend beta-lactam avoidance or administration of a full dose beta-lactam, we only reviewed beta-lactams initiated by a test dose in this study. All data were abstracted and analyzed retrospectively, which can result in misclassification; however, HSR determination was rigorously determined by allergist co-investigators. Although we can compare our observed ADR and HSR rates from test doses to published ADR and HSR rates from the literature, it was not possible to identify an internal comparison group of PHS patients who were eligible for beta-lactam test doses, but who did not receive them. While evaluating HSRs occurring from direct challenges in patients with different allergy histories provides insight into beta-lactam cross-reactivity, patients included in this study had an unknown true allergy status. Finally, while we report on a multi-site intervention, all hospitals are part of one geographically localized large US healthcare system. However, non-PHS hospitals have also adopted this guideline.19

An electronic guideline with penicillin and cephalosporin hypersensitivity pathways encouraging beta-lactam test dose challenges was implemented in five hospitals with different resources using one EHR as an antibiotic stewardship tool. The ADR and HSR rates were low, and not higher than expected given a morbid inpatient population with prior reported drug allergies. Certain test dose challenges may be omitted given their observed safety, and caution is prudent with cephalosporin-allergy challenged inpatients. Additional efforts to improve allergy documentation are important to the success of beta-lactam allergy interventions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding

This work was supported by Partners Quality, Safety, and Value and the Partners Clinical Process Improvement Leadership Program. Dr. Blumenthal receives career development support from the NIH K01AI125631, the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology Foundation, and the MGH Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

General acknowledgments

The authors thank Partners Penicillin Hypersensitivity Pathway team members: David W. Kubiak, PharmD, BCPS, Praveen Meka, MD, Diana Balekian, MD, MPH, and Roger P. Clark, DO. The authors thank Partners Quality, Safety, and Value and Clinical Process Improvement Leadership Program sponsors: Brian Cummings, MD and Thomas Sequist, MD, MPH. The authors thank Christian Mancini for his research assistance and Xioqing Fu, MS for her data analysis support. Finally, the authors thank Youyang Yang, MD, Jonathan D. Paolino, MD, Arianne Baker, MD, Yasmin Islam, MD, and Robert P. McInnis, MD for serving as housestaff chart reviewers.

Abbreviations:

- PST

Penicillin skin testing

- PHS

Partners HealthCare System

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- BWH

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

- EHR

Electronic health record

- HSR

Hypersensitivity reaction

- ADR

Adverse drug reaction

- CI

Confidence intervals

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- NWH

Newton Wellesley Hospital

- NSMC

North Shore Medical Center

- BWF

Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital

- Med

Median

- IQR

Interquartile range

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IM

Intramuscular

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Blumenthal reports royalties from UpToDate, and honoraria from New England Society of Allergy, Dartmouth Medical School, and Vanderbilt Medical School, outside the submitted work. Drs. Blumenthal and Shenoy report a licensed clinical decision support tool for beta-lactam allergy evaluation that is used institutionally at Partners HealthCare System.

REFERENCES

- 1.Conway EL, Lin K, Sellick JA, Kurtzhalts K, Carbo J, Ott MC, et al. Impact of penicillin allergy on time to first dose of antimicrobial therapy and clinical outcomes. Clin Ther. 2017;39(11):2276–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee CE, Zembower TR, Fotis MA, Postelnick MJ, Greenberger PA, Peterson LR, et al. The incidence of antimicrobial allergies in hospitalized patients: implications regarding prescribing patterns an demerging bacterial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2819–2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenthal KG, Ryan EE, Li Y, Lee H, Kuhlen JL, Shenoy ES. The impact of a reported penicillin allergy on surgical site infection risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(3):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffres MN, Narayanan PP, Shuster JE, Schramm GE. Consequences of avoiding beta-lactams in patients with beta-lactam allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;137(4):1148–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macy E, Blumenthal KG. Are cephalosporins safe for use in penicillin allergy without prior allergy evaluation? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6(1):82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M, Kuhlen JL, Ware WA, Parker RA, et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Li Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Risk of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile in patients with a documented penicillin allergy: Population based matched cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sacco KA, Bates A, Brigham TJ, Imam JS, Burton MC. Clinical outcomes following inpatient penicillin allergy testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2017;72(9):1288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, MacDougall C, Schuetz AN, Septimus EJ, et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS, Tran T, Khan DA. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Hurwitz S, et al. Tackling inpatient penicillin allergies: Assessing tools for antimicrobial stewardship. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140(1):154–161 e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rimawi RH, Cook PP, Gooch M, Kabchi B, Ashraf MS, Rimawi BH, et al. The impact of penicillin skin testing on clinical practice and antimicrobial stewardship. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Hurwitz S, Varughese CA, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Effect of a drug allergy educational program and antibiotic prescribing guideline on inpatient clinical providers’ antibiotic prescribing knowledge. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Wolfson AR, Berkowitz DN, Carballo VA, Balekian DS, et al. Addressing inpatient beta-lactam allergies: A multihospital implementation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):616–625 e617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA, Hurwitz S, Hooper DC, Banerji A. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):294–300 e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heil EL, Bork JT, Schmalzle SA, Kleinberg M, Kewalramani A, Gilliam BL, et al. Implementation of an infectious disease fellow-managed penicillin allergy skin testing service. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):ofw155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacco KA, Cochran BP, Epps K, Parkulo M, Gonzalez-Estrada A. Inpatient beta-lactam test-dose protocol promotes antimicrobial stewardship in patients with history of penicillin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018. DOI 10.1016/j.anai.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaisman A, McCready J, Hicks S, Powis J. Optimizing preoperative prophylaxis in patients with reported beta-lactam allergy: A novel extension of antimicrobial stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(9):2657–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swearingen SM, White C, Weidert S, Hinds M, Narro JP, Guarascio AJ. A multidimensional antimicrobial stewardship intervention targeting aztreonam use in patients with a reported penicillin allergy. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(2):213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staicu ML, Brundige ML, Ramsey A, Brown J, Yamshchikov A, Peterson DR, et al. Implementation of a penicillin allergy screening tool to optimize aztreonam use. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(5):298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leis JA, Palmay L, Ho G, Raybardhan S, Gill S, Kan T, et al. Point-of-Care beta-lactam allergy skin testing by antimicrobial stewardship programs: A pragmatic multicenter prospective evaluation. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(7):1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall GC, Peters L, Leaders CB, Wille JA. Pharmacist-managed service providing penicillin allergy skin tests. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(12):1271–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trubiano JA, Beekmann SE, Worth LJ, Polgreen PM, Thursky KA, Slavin MA, et al. Improving antimicrobial stewardship by antibiotic allergy delabeling: Evaluation of knowledge, attitude, and practices throughout the emerging infections network. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(3):ofw153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaisman A, McCready J, Powis J. Clarifying a “penicillin” allergy: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:269–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenthal KG, Solensky R. Choice of Antibiotics in Penicillin-Allergic Hospitalized Patients. In: Post TW, Ed. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/choice-of-antibiotics-in-penicillinallergic-hospitalized-patients. Accessed September 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liccardi G, Senna G, Russo M, Bonadonna P, Crivellaro M, Dama A, et al. Evaluation of the nocebo effect during oral challenge in patients with adverse drug reactions. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14(2):104–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lombardi C, Gargioni S, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. The nocebo effect during oral challenge in subjects with adverse drug reactions. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;40(4):138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iammatteo M, Alvarez Arango S, Ferastraoaru D, Akbar N, Lee AY, Cohen HW, et al. Safety and outcomes of oral graded challenges to amoxicillin without prior skin testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018. DOI 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Acker WW, Chang Y, Banerji A, Ghaznavi S, et al. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome and multiple drug allergy syndrome: Epidemiology and associations with anxiety and depression. Allergy. 2018;73(10):2012–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macy E, Ho NJ. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome: Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and management. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108(2):88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, Arndt K. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions. A report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program on 15,438 consecutive inpatients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA. 1986;256(24):3358–3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiriac AM, Wang Y, Schrijvers R, Bousquet PJ, Mura T, Molinari N, et al. Designing Predictive Models for Beta-Lactam Allergy Using the Drug Allergy and Hypersensitivity Database. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):139–148 e132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romano A, Valluzzi RL, Caruso C, Maggioletti M, Quaratino D, Gaeta F. Cross-Reactivity and tolerability of cephalosporins in patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to penicillins. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1662–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macy E Penicillin skin testing in pregnant women with a history of penicillin allergy and group B streptococcus colonization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(2):164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romano A, Gaeta F, Valluzzi RL, Maggioletti M, Zaffiro A, Caruso C, et al. IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to cephalosporins: Cross-reactivity and tolerability of alternative cephalosporins. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(3):685–691 e683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zagursky RJ, Pichichero ME. Cross-reactivity in beta-lactam allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):72–81 e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blumenthal KG, Park MA, Macy EM. Redesigning the allergy module of the electronic health record. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(2):126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliver WD, Heil EL, Thom KA, Martinez JP, Hayes BD. Allergy profile should be updated after uneventful administration of a penicillin or penicillin-related antibiotic to a patient with penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(1):184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouwmeester MC, Laberge N, Bussieres JF, Lebel D, Bailey B, Harel F. Program to remove incorrect allergy documentation in pediatrics medical records. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(18):1722–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.