Abstract

At the optic chiasm, retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons make the decision to either avoid or traverse the midline, a maneuver that establishes the binocular pathways. In mice, the ipsilateral retinal projection arises from RGCs in the peripheral ventrotemporal (VT) crescent of the retina. These RGCs express the guidance receptor EphB1, which interacts with ephrin-B2 on radial glia cells at the optic chiasm to repulse VT axons away from the midline and into the ipsilateral optic tract. However, since VT RGCs express more than one EphB receptor, the sufficiency and specificity of the EphB1 receptor in directing the ipsilateral projection is unclear. In this study, we utilize in utero retinal electroporation to demonstrate that ectopic EphB1 expression can redirect RGCs with a normally crossed projection to an ipsilateral trajectory. Moreover, EphB1 is specifically required for rerouting RGC projections ipsilaterally, as introduction of the highly similar EphB2 receptor is much less efficient in redirecting RGC fibers, even when expressed at higher surface levels. Introduction of EphB1-EphB2 chimeric receptors into RGCs reveals that both extracellular and juxtamembrane domains of EphB1 are required to efficiently convert RGC projections ipsilaterally. Taken together, these data describe for the first time functional differences between two highly similar Eph receptors at a decision point in vivo, with EphB1 displaying unique properties that efficiently drives the uncrossed retinal projection.

Keywords: optic chiasm, axon guidance, Eph/ephrin signaling, retinal ganglion cells, electroporation, midline

INTRODUCTION

Retinal fibers converge at the ventral diencephalon to form the optic chiasm, the first step in patterning binocular vision. In mice, the ipsilateral RGC projection arises from the peripheral VT crescent of the retina and approaches then turns away from the optic chiasm midline. Optic chiasm cells express a contact-dependent cue that inhibits outgrowth specifically from VT RGCs (Marcus et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1995). Insights into the identity of this cue came from studies on Xenopus (Nakagawa et al., 2000) and were extended to mice, where EphB1 is upregulated in the peripheral VT crescent and ephrin-B2 at the optic chiasm midline (Williams et al., 2003). This repulsive receptor-ligand interaction directs the ipsilateral retinal projection.

Eph receptors are divided into two subfamilies (EphAs and EphBs) that primarily interact with their corresponding family of ligands (ephrin-As and ephrin-Bs), with extensive receptor-ligand promiscuity within each subfamily (Flanagan and Vanderhaeghen, 1998). Multiple Eph receptors (and ephrins) are commonly co-localized in the same cells throughout development, notably in the retina and superior colliculus/tectum (McLaughlin and O'Leary, 2005), thalamus (Dufour et al., 2003), cerebral cortex (Yun et al., 2003), and the developing limb (Eberhart et al., 2000; Kania and Jessell, 2003; Luria et al., 2008), leading to overlapping and compensatory functions. For example, in the retinocollicular/retinotectal projection, the relative levels of EphA receptors, and not the specific subtype of EphA receptor, govern proper topographic targeting (Brown et al., 2000; Lemke and Reber, 2005). Conversely, hippocampal neurons and cortical pyramidal scells express EphB1-B3, but only EphB1 and EphB2 contribute to spine morphogenesis in the hippocampus and primarily EphB2 in cortical neurons (Henkemeyer et al., 2003; Kayser et al., 2006). Thus, the functional redundancy and specificity of Eph receptors in vivo appears to be context-dependent.

In the murine retina, EphB2 is expressed in a high ventral-to-low dorsal gradient and EphB3 is expressed throughout the RGC layer (Williams et al., 2003; McLaughlin and O'Leary, 2005). Therefore, VT RGCs express EphB1-B3. Examination of knockout mice revealed that EphB1 appears to be the only receptor required for driving the ipsilateral projection, with EphB2 playing a minor role (Williams et al., 2003). Thus, in contrast to the retinocollicular/retinotectal projections, the specific subtype of EphB receptor (EphB1), and not the net level of EphB receptors, may direct the ipsilateral retinal projection. The issue of Eph receptor specificity vs. net Eph receptor levels has not been directly examined in the optic chiasm.

In this study, we examined the sufficiency and specificity of EphB1 in directing the ipsilateral RGC projection. We utilized in utero retinal electroporation to demonstrate that ectopic EphB1 expression converts crossed RGC projections to an ipsilateral fate. In addition, we compare and contrast similar EphB receptors to elucidate the domains of the EphB1 receptor required for guiding the ipsilateral retinal projection. These experiments reveal that EphB2 is less efficient that EphB1 in redirecting non-VT RGC axons ipsilaterally. Introduction of EphB1-EphB2 chimeric receptors into RGCs indicated that the increased efficiency requires both the extracellular and juxtamembrane domains of EphB1. These results demonstrate functional differences between similar EphB receptors in vivo at a well-characterized decision point.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57Bl/6J mice were kept in a timed pregnancy breeding colony at Columbia University. E0 defined was as midnight on the day a plug was found. Animals were treated according to NIH guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and Columbia University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved our mouse protocols.

Preparation of expression constructs

Full length murine EphB1 was obtained via EST clone #6400265 from the IMAGE Consortium. Murine EphB2 was obtained in the pMT21 vector (Williams et al., 2003). The HA tag was added to the 5’ end by cloning full-length EphB1 and EphB2 into pcDNA3.1/Hygro©(+) plasmid (Invitrogen) that contained a ‘signal sequence-HA’ insertion (gift of P. Scheiffele, Columbia University). The HA-tag is present in all EphB constructs used in this study. The GFP construct was a gift from A. Beg, Columbia University, and the Zic2 construct was a gift from E. Herrera, Alicante, Spain.

For EphB1 point mutations, the Stratagene Quikchange® XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit was used with the following primers and their reverse compliments (mutated sequences are underlined): 1) KD EphB1 mutant (K651Q): 5’-GGAAATCTATGTGGCCATCCAGACCCTGAAGGCTGG-3’, 2) 2Y-E EphB1 mutant (Y594E/Y600E): 5’-GGATGAAGATCGAGATTGACCCATTCACTGAGGAGGACCCCAATGAAGC-3’, 3) EphB1 Y928F: 5’-CCATCAAAATGGTCCAGTTCAGGGACAGCTTCC-3’, and 4) EphB1ΔSAM: 5’-CCCAGACTTCACGGCCTGAACCACCGTGGATGAC-3’.

For the intracellular swaps (EphB1out-B2in and EphB2out-B1in), a NotI site was inserted just outside the putative transmembrane region by performing overhang PCR reactions with the following primers (NotI site underlined): 1) EphB1out: 5’-TGCTGTCTCATCATTTTGGC-3’ and 5’-AAAGCGGCCGCTCTTGTAATCATC-3’, 2) EphB2out: 5’-TGCTGTCTCATCATTTTGGC-3’ and 5’-AAAGCGGCCGCTCTGGTACTCGGC-3’, 3) EphB1in: 5’-AGCCCAGTTTCTATGTGGTCTCC-3’ and 5’-AAAAGCGGCCGCAGAGAGCAGATA-3’, 4) EphB2in: 5’-AGCCCAGTTTCTATGTGGTCTCC-3’ and 5’- CCAAGCGGCCGCAAGGAAAAGCTA-3’. The ‘out’ PCR reactions were digested with NotI and XmaI and the ‘in’ PCR reactions were digested with NotI and XhoI. The desired products were then ligated into the proper backbone to produce EphB1out-B2in and EphB2out-B1in constructs.

For the SAM domain swap mutations (EphB1-B2T300 and EphB2-B1T300), EphB1 and EphB2 constructs were digested with BclI and XhoI, then these products were ligated into the other backbone to produce EphB1-B2T300 and EphB2-B1T300 constructs.

For the terminal 6 residue swaps (EphB1-B2T6 and EphB2-B1T6), overhang PCR reactions were performed with the following primers (terminal 6 residues underlined): 1) EphB1-B2T6: 5’-TCAAACCTCTACAGACTGGATCTGGTTCATCTGGACCCTCAT-3’ and 5’-AGCCGGAGCAACCCAATGGC-3’, and 2) EphB2-B1T6: 5’-TCACGCCATTACCGATGGTGACTGGTTCATCTGGGCCCGCAT-3’ and 5’-ATCGGCCGTGTCCATCATGC-3’. These blunt end PCR products were inserted into pCR®-Blunt using the Zero Blunt® PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen), digested with BclI and XhoI, and the desired regions were then ligated into the other backbone, similar to the SAM domain swaps. All cloning was carried out in either MAX Efficiency® DH5α™ Competent Cells (Invitrogen), XL10-Gold® Ultracompetent Cells (Stratagene), or dam−/dcm− Competent E. coli (New England Biolabs).

In utero retinal electroporation and analysis

A procedure similar to the one used in this study was previously described (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2007). E13.5- and E14.5-stage timed pregnant female mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 0.12 ml of a 1:0.2:4.6 volume mix of ketamine (100 mg/ml):xylazine (100 mg/ml):saline. A vertical incision was made on the midline of the abdomen to expose the uterine horns. DNA solution (0.5 µg/ml GFP ± 5.0 µg/ml HA-EphB DNA or Zic2 + 0.03% Fast Green Dye in distilled water) was loaded into a graduated pulled-glass micropipette and 0.1–0.5 µl was carefully injected into one retina of an embryo, ideally filling the space between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the outer retinal layer. The electroporation technique does not work well when DNA is injected into the vitreous, in agreement with previous observations (Matsuda and Cepko, 2004; Garcia-Frigola et al., 2007). Tweezer-type electrodes (CUY650-P7, Nepa Gene) were then placed around the head (with the ‘+’ electrode near the injected retina) and five 50-ms square current pulses were delivered (45V for E14.5, 35V for E13.5) at 950 ms intervals using an electroporator (ECM 830, Harvard Apparatus). After repeating this procedure for the desired number of embryos, the peritoneum was sutured and the skin was stapled closed, and the embryos were allowed to develop normally.

At E18.5, pregnant mothers were sacrificed and embryos perfused with 4% PFA. Retina were removed and examined with a fluorescent dissecting microscope for GFP+ fluorescence. All GFP+ retina were immunostained for GFP, HA (or Zic2) and neurofilament. Heads were then immersed in 30% sucrose in PBS, cryosectioned (20 µm sections), and immunostained for GFP, HA and neurofilament. Analysis was only carried out on embryos in which the most peripheral 300 µm of the VT crescent did not contain GFP+ cells, as this is the region which contains ipsilaterally projecting RGCs identified by retrograde backfills (Williams et al., 2006; data not shown). For each sectioned head, 3 evenly spaced sections of the contralateral and ipsilateral optic tract (OT) were taken and the GFP signal within each OT section was recorded (Supplementary Fig. 1). A ratio of ‘GFP+ signal in ipsilateral OT/GFP+ signal in ipsilateral + contralateral OT’ was determined for each of the three levels of section, which were then averaged to produce a ‘percentage of GFP+ signal in ipsilateral OT’ for each embryo. Analysis was carried out blind to which DNA construct was electroporated.

In some instances, the heads were not sectioned and instead semi-intact visual system preparations were immunostained for GFP to visualize axons in the optic nerve, optic chiasm and optic tracts. In these samples, two observers blind to which DNA constructs were electroporated scored the presence or absence of aberrant RGC projections at the chiasm.

Ex vivo retinal electroporation

E13.5 and E14.5 embryos were removed from anesthetized mothers by caesarian section and decapitated. Graduated pulled-glass micropipettes were filled with a DNA solution (0.4 µg/ml GFP ± 3.0 µg/ml HA-EphB DNA + 0.03% Fast Green Dye in distilled water). Heads were pinned down dorsal side up in a petri dish containing PBS and DNA was injected into the peripheral dorsal region (between the RPE and outer retinal layer) of both retinae. As above, tweezer-type electrodes were then placed on around the head (with ‘+’ electrode on the ventral surface of the head) and four 50-ms, 40V square current pulses were delivered. Intact retinas were then removed and incubated in serum free medium (SFM) derived from freshly bubbled (95% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide) DMEM/F12 medium at 37°C for 40 hrs, allowing for RGC differentiation and exogenous protein expression. Retinae were scanned for GFP+ regions, which were then dissected out and prepared into explants. In some samples, a small DiI crystal was placed in the peripheral ventral crescent to ensure that the GFP+ region was in fact peripheral dorsal retina (data not shown). Explants were plated either on laminin coated dishes for live staining or plated adjacent to ephrin-B2-Fc or Fc borders and incubated overnight at 37°C.

RGC explant assays and analysis

Preparation of retinal explant cultures, border assays and analyses has been described in detail previously (Petros et al., 2006). For border assays, murine ephrin-B2-Fc (gift of N. Gale, Regeneron) or human Fc (Jackson Immunologicals) was clustered by the addition of 10-fold excess goat anti-human Fc antibody (Jackson Immunologicals) at 37°C for 2 hr. To visualize borders, BSA conjugated to Alexa Fluor® 555 (1:800, Molecular Probes) was added to the Fc protein solutions, then 100 µl was applied to half of the culture dish, incubated at 37°C for 2 hr, and then the entire dish was coated with laminin. Explants were plated in serum-free medium containing 0.4% methylcellulose (Sigma). For border assays analyses, a ratio of ‘area of GFP+ signal within border region/total GFP+ signal approaching border’ was determined (Petros et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2008) (see cartoon in Fig. 7).

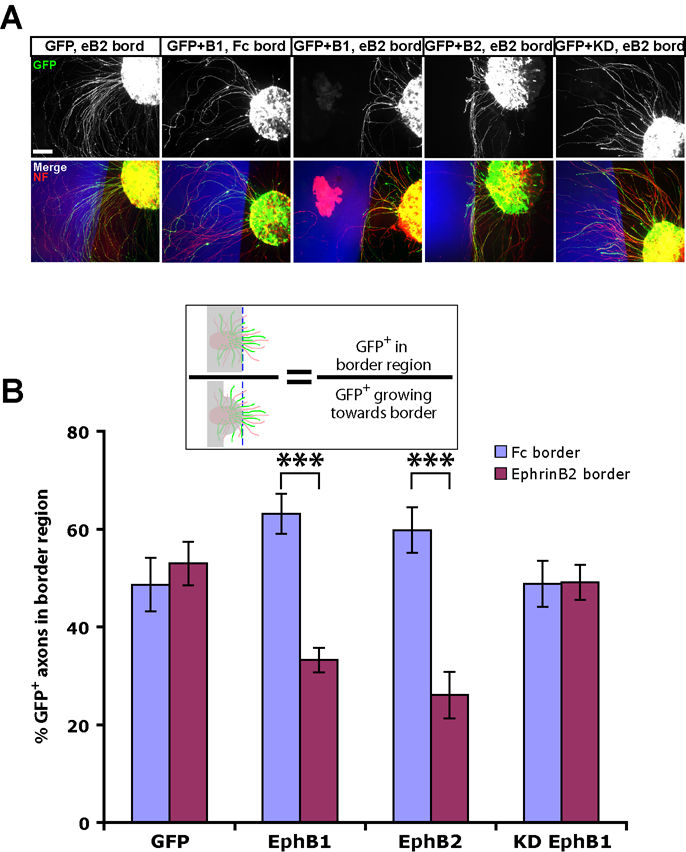

Figure 7. EphB2 electroporated retinal axons are repelled by ephrin-B2 substrates.

(A) Examples of explants from ex vivo electroporated retina plated adjacent to ephrin-B2 (eB2) or control Fc substrate borders (blue regions, see Fig. 6). Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) GFP+ RGC axons from both EphB1 and EphB2 electroporated retina are repelled by ephrin-B2 borders, while RGC axons electroporated with GFP alone or KD EphB1 project uninhibited into the ephrin-B2 region. Cartoon depicts method of analysis, with GFP axons in grey region not included in calculations. n ≥ 12 explants for each condition, from at least 2 separate experiments. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. ANOVA: F(7,127) = 8.08, p < .0001. Modified t-tests: *** = p < .0001.

Immunohistochemistry

E18.5 whole retinae and cryosections were blocked in 10% normal donkey serum (NDS, Jackson Immunochemicals) + 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma), while retinal explants from ex vivo electroporations were blocked in 10% NDS + 0.1% Tween (Sigma). The following primary antibody dilutions were used in these experiments, incubated in 50% block overnight at 4°C: rabbit anti-GFP, 1:500 (Molecular probes); sheep anti-GFP, 1:250 (Biogenesis); rat anti-HA, 1:500 (Roche); mouse IgG anti-neurofilament (2H3), 1:5 (gift of T. Jessell, Columbia University); rabbit anti-Zic2, 1:10,000 (gift of S. Brown, U. Vermont). After ≥ 1 hour PBS washes, appropriate fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunologicals) were added at RT for ≥ 2 hours.

For immunohistochemistry of live cells, ex vivo electroporated explants were cultured for 20 hrs at 37°C. Dishes were washed twice with RT HEPES buffer (HBS), and then rat anti-HA (1:250) in HBS was added to each dish for 40 min at RT. Dishes were then washed several times with HBS, fixed with 4% PFA, and then stained for GFP, neurofilament and HA (secondary Ab only) as described above. Fluorescence intensity and exposure time were kept constant between different experiments for imaging of live stained HA+ RGC axons and growth cones.

Retinal whole mounts, cryosections and retinal explants were imaged on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 epifluorescent microscope equipped AxioCam cameras (Zeiss) with Openlab deconvolution software (Improvision, Inc., Boston MA).

Analysis and Statistics

All data were analyzed and graphs constructed using Openlab imaging software or Microsoft Excel. All error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) and statistical analysis was determined using Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed Students’ t tests, or ANOVA followed by modified t-tests, where appropriate.

RESULTS

Ectopic EphB1 expression converts crossed RGCs into an ipsilateral fate

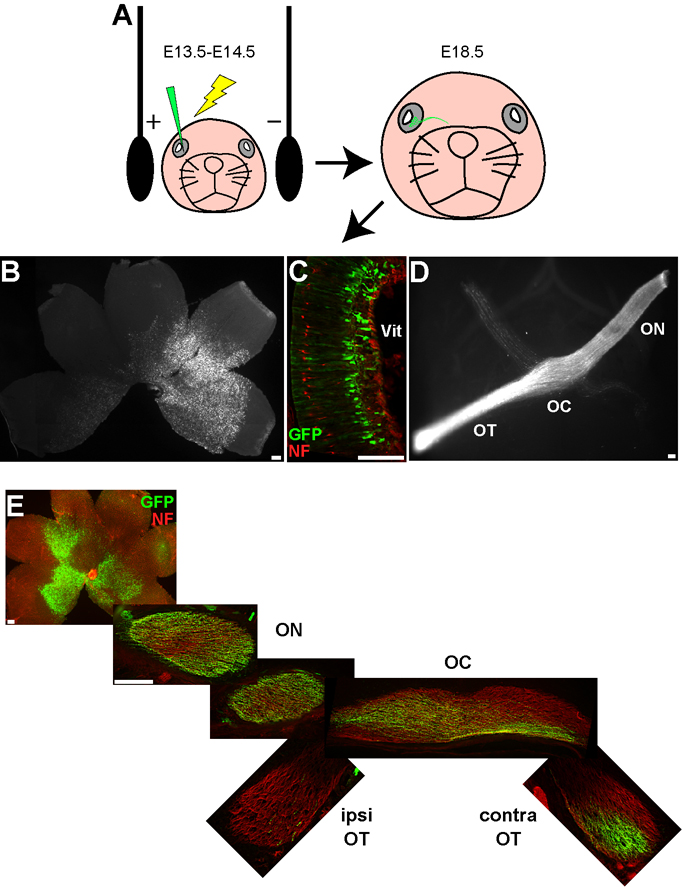

EphB1 is required for formation of the mature ipsilateral RGC projection from VT retina (Williams et al., 2003), but is EphB1 sufficient to direct RGC fibers ipsilaterally? We introduced genes into embryonic RGCs via in utero retinal electroporation (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2007) to determine if ectopic EphB1 expression can convert non-VT RGC fibers to an ipsilateral fate. To confirm the viability of this technique, we electroporated GFP expression constructs into E14.5 retina and harvested the embryos at E18.5 (Fig. 1A). We chose E14.5 because this is when the ipsilateral projection begins to form (Petros et al., 2008). GFP is visible in RGC cell bodies (Fig. 1B,C) and axons within the optic nerve, chiasm and optic tract, as viewed in either semi-intact visual system preparations (Fig. 1D) or cryosections through the optic pathway (Fig. 1E). GFP+ RGCs were usually confined to the central retina, and any retinae with GFP+ cells in the VT retina were not included in the calculations. No obvious cell morphology or projection defects were observed in the retina or ventral diencephalon in GFP electroporated embryos.

Figure 1. GFP expression in retinal ganglion cells after in utero retinal electroporation.

(A) Cartoon depicting in utero retinal electroporation procedure. All images are taken from E18.5 embryos electroporated with GFP at E14.5. (B–C) GFP+ retinal cells are clearly visible in both whole mount (B) and cryosectioned retina (C), where the GFP+ cells are predominantly localized to the ganglion cell layer. (D–E) GFP+ axons can be visualized throughout the optic nerve (ON), optic chiasm (OC) and optic tract (OT) in either the semi-intact visual system preparation (D) or serial cryosections throughout the projection pathway (E). NF = neurofilament, Vit = vitreous. All scale bars = 100 µm.

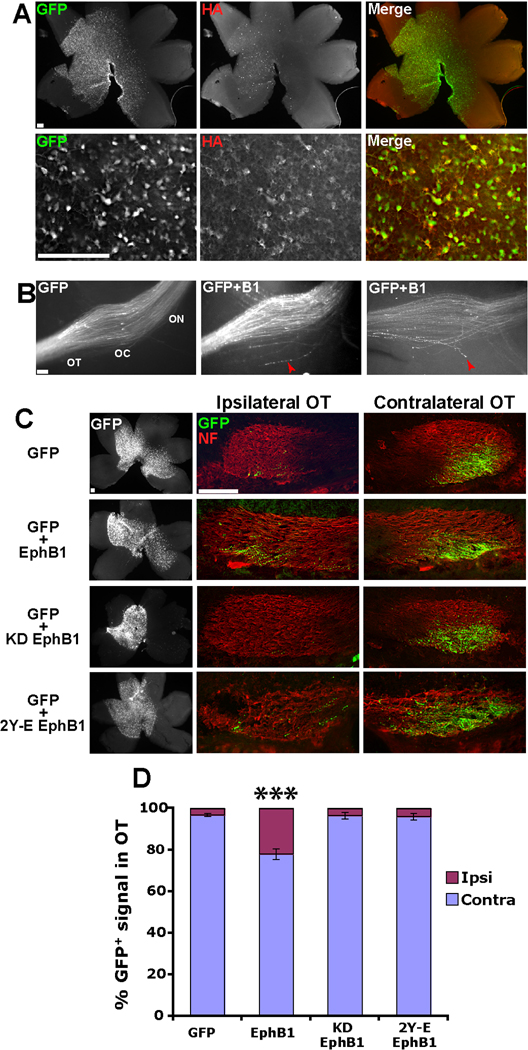

To determine if exogenous EphB1 can convert crossed RGC projections to an uncrossed fate, we co-electroporated GFP and HA-tagged EphB1 constructs into non-VT RGCs. GFP and HA were co-localized in the majority of RGCs (Fig. 2A), indicating that GFP reliably represents ectopic EphB1 expression. Examination of semi-intact whole mount preparations revealed that ectopic EphB1 expression induced projection errors at the optic chiasm. In the majority of embryos electroporated with GFP+EphB1 (77%, n=13 embryos), a small subset of GFP+ axons displayed ectopic projections posterior to the chiasm (Fig. 2B). This behavior was rarely observed after electroporating retina with GFP alone (14%, n=7, p=0.017, Fisher’s exact test).

Figure 2. Ectopic EphB1 expression converts crossed RGC projections to an ipsilateral fate in a kinase-dependent manner.

(A) Examples of E18.5 retina electroporated with GFP+HA-EphB1 at E14.5. Top, Low power view of entire retina. Bottom, Higher power images demonstrating that the vast majority of GFP+ cells are also HA+, indicating that GFP faithfully recapitulates ectopic EphB1 expression. (B) The optic chiasm in semi-intact visual system preparations of embryos electroporated with GFP (left) or GFP+EphB1 (middle & right). Note that some GFP+ axons from GFP+EphB1 electroporated embryos misproject posteriorly at the optic chiasm (red arrowheads), which was rarely observed in embryos electroporated with GFP alone. n ≥ 7 for each condition. (C) Whole mount retina and cryosections through the ipsilateral and contralateral optic tracts from embryos electroporated with either GFP, EphB1, KD EphB1 and 2Y-E EphB1. (D) A significant increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections is observed embryos electroporated with GFP+EphB1 compared to GFP alone (22% vs. 3%). This increase is not observed in KD EphB1 nor 2Y-E EphB1 electroporated embryos. n ≥ 9 embryos for each condition, from ≥ 3 separate electroporation experiments. Data represent mean ± s.e.m., all scale bars = 100 µm. ANOVA: F(3,48) = 27.09, p < .0001; Modified t-tests: *** = p < .0001.

We cryosectioned GFP+ E18.5 heads though the optic chiasm and optic tracts in order to more clearly analyze GFP+ projections (Supplementary Fig. 1). Electroporation of GFP alone (n=14 embryos) revealed that the majority of GFP+ fibers from non-VT retina cross the midline and project into the contralateral optic tract, with only a small percentage (3.3%) projecting ipsilaterally. In contrast, embryos electroporated with GFP and EphB1 (n=17) displayed a significantly higher percentage of GFP+ projections into the ipsilateral optic tract (22.1%) (Fig. 2C,D).

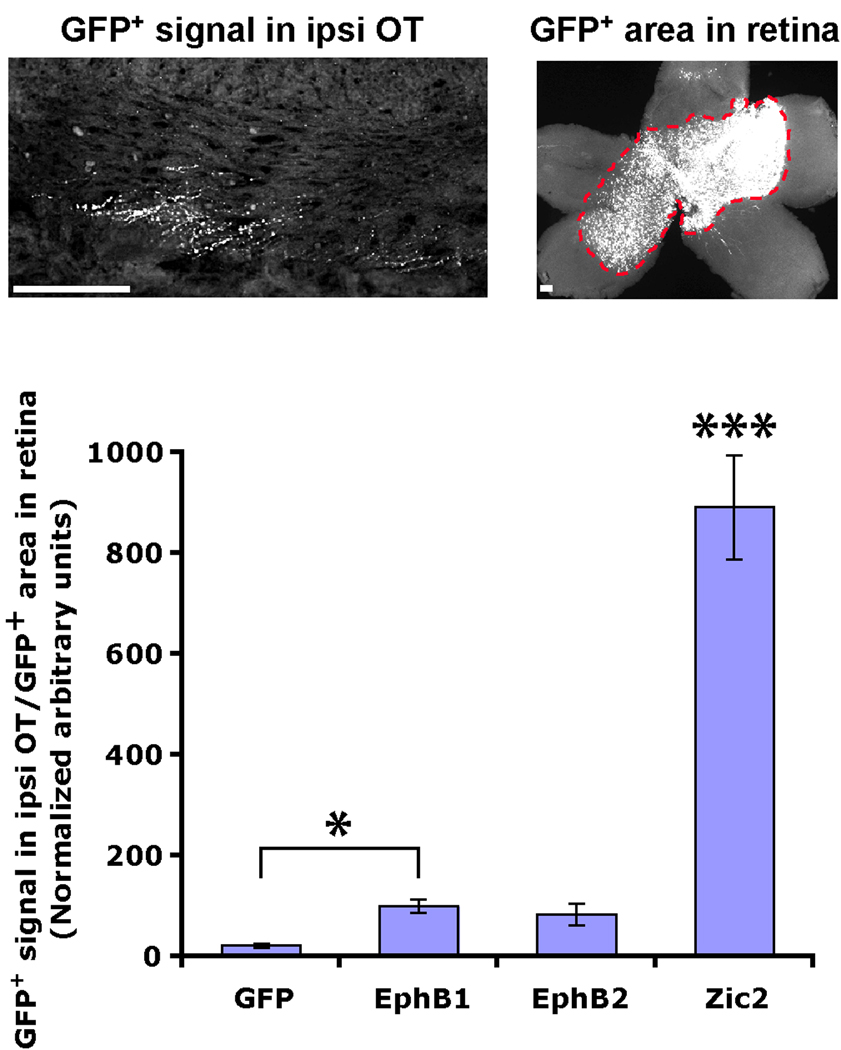

This apparent increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections could arise from a decrease in contralateral projections. To investigate this possibility, we divided the amount of GFP signal in the ipsilateral optic tract by the area of GFP+ cells in the retina. If there were an increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections, then this ratio should be higher for embryos electroporated with GFP and EphB1 compared to GFP alone. Indeed, this is what we observed (Fig. 3), indicating that there are definitively more GFP+ axons in the ipsilateral optic tract of embryos electroporated with GFP+EphB1. Thus, in addition to inducing misrouting at the chiasm, ectopic expression of EphB1 is sufficient to convert a subset of RGC projections from a crossed to an uncrossed fate.

Figure 3. Ectopic EphB1 and Zic2 induce an increase in GFP+ fibers in the ipsilateral optic tract.

It is possible that the apparent increase in ipsilateral projections actually arises from a decrease in contralateral projections. To confirm that this is not the case, we divided the GFP+ signal in the ipsilateral optic tract by the GFP+ area in the retina. If there is not an actual increase in uncrossed fibers, then this ratio should remain constant for all conditions. However, it is clear that there are significantly more GFP+ axons in the ipsilateral optic tract of EphB1 and Zic2-electroporated embryos. n ≥ 10 embryos for each condition, from ≥ 3 electroporation experiments. Data represent mean ± s.e.m., all scale bars = 100 µm. ANOVA: F(3,68) = 112.10, p < .0001. Modified t-tests: * = p ≤ .05, *** = p < .0001.

To confirm that the increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections is due to EphB1 activity, we prepared two constructs with perturbed EphB1 signaling: a kinase dead EphB1 receptor (KD EphB1) and a construct in which the kinase domain remains active but the receptor is incapable of activating many downstream signaling cascades due to phopho-mimetic mutations of two juxtamembrane tyrosine residues (2Y-E EphB1) (Zisch et al., 2000; Elowe et al., 2001; Vindis et al., 2003; Egea et al., 2005). Embryos electroporated with either GFP+KD EphB1 (n=11) or GFP+2Y-E EphB1 (n=10) did not display an increase in GFP+ ipsilateral fibers, mimicking control GFP electroporations (Fig. 2C,D). These findings indicate that the increased percentage of GFP+ ipsilateral RGC axons after EphB1 electroporations is not an artifact of ectopic gene overexpression. In addition, these experiments demonstrate that EphB1 kinase activity and downstream signaling cascades are required to redirect RGC projections ipsilaterally in vivo.

EphB1 is not as efficient as Zic2 in driving the ipsilateral RGC projection

Although exogenous EphB1 redirects a significant percentage of GFP+ fibers into the ipsilateral optic tract, the majority of GFP+ axons still project contralaterally. It is possible that some EphB1+ axons arrive at the optic chiasm after ephrin-B2 has been downregulated, which occurs at E16.5 (Williams et al., 2003), and thus EphB1+ axons can project through the ephrin-B2-negative optic chiasm. If this is true, then electroporating EphB1 one day earlier at E13.5 should produce an even greater increase in the percentage of GFP+ ipsilateral fibers. However, we did not observe a further increase in the number of GFP+ ipsilateral projections when EphB1 was electroporated at E13.5 (n=13, Fig. 4), indicating that ectopic introduction of EphB1 may be capable of converting only ~20% of all RGCs to an ipsilateral fate.

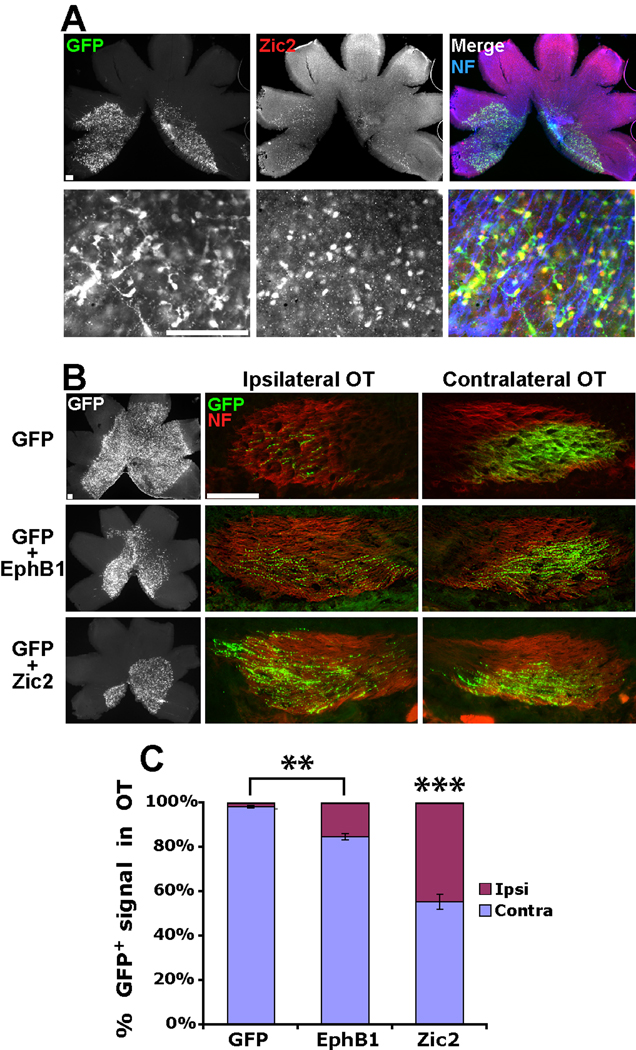

Figure 4. Zic2 induces a greater increase in ipsilateral RGC projections compared to EphB1.

(A) Low power (top) and high power (bottom) images of E18.5 retina electroporated with GFP+Zic2 at E13.5. Note that the majority of GFP+ cells stain positive for Zic2. (B) Representative examples of E18.5 retina and optic tracts from embryos electroporated with GFP, GFP+EphB1 and GFP+Zic2 at E13.5. (C) While electroporating EphB1 at E13.5 did not induce a greater increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections compared to E14.5 electroporations, ectopic Zic2 expression is significantly more efficient in converting contralateral RGC projections to an ipsilateral fate. n = 5 for GFP control electroporations and n ≥ 10 for EphB1 and Zic2 electroporations, from ≥ 3 different electroporation experiments. Data represent mean ± s.e.m., all scale bars = 100 µm. ANOVA: F(2,25) = 71.28, p < .0001. Modified t-tests: ** = p < .005, *** = p < .0001.

Exogenous EphB1 may not be capable of overriding endogenous transcriptional programs that direct the contralateral RGC projection. Similar to EphB1, the transcription factor Zic2 is expressed in the VT crescent and is required for directing the ipsilateral projection (Herrera et al., 2003). Zic2 drives EphB1 expression (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008), and ectopic Zic2 delivery can convert contralateral projections into an ipsilateral fate (albeit only when delivered at E13.5 and not E14.5) (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2008). To directly compare the abilities of EphB1 and Zic2 to redirect RGC fibers ipsilaterally, we electroporated GFP+Zic2 into E13.5 retina (n=10). The majority of GFP+ RGCs co-express Zic2 (Fig. 4A). In agreement with previous data (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2008), we found that exogenous Zic2 redirected nearly 50% of GFP+ RGC projections ipsilaterally (Fig. 4B,C, and Fig. 3). Thus, Zic2, located upstream of EphB1 in the hierarchy of genes that controls the ipsilateral program, is more efficient at driving RGC fibers to an ipsilateral fate than EphB1 alone.

Receptor specificity is more important than net EphB receptor levels for RGC axon divergence at the optic chiasm

EphB2 is expressed in a high ventral-to-low dorsal gradient and EphB3 is homogenously expressed within the RGC layer as the uncrossed RGC pathway develops (Birgbauer et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2003; McLaughlin and O'Leary, 2005). Thus, RGCs within the VT crescent likely express all three EphB receptors. Murine EphB1 and EphB2 sequences are highly similar (~75% identical), and both have similar binding affinities to ephrin-B2 (Bergemann et al., 1995; Brambilla et al., 1996; Gale et al., 1996). While EphB1−/− mice have a severely reduced ipsilateral projection, axon divergence at the optic chiasm appears normal in EphB2−/−, EphB3−/− and EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− mice (Williams et al., 2003) (although EphB2−/−;EphB3−/− mice display intraretinal guidance errors (Birgbauer et al., 2000)).

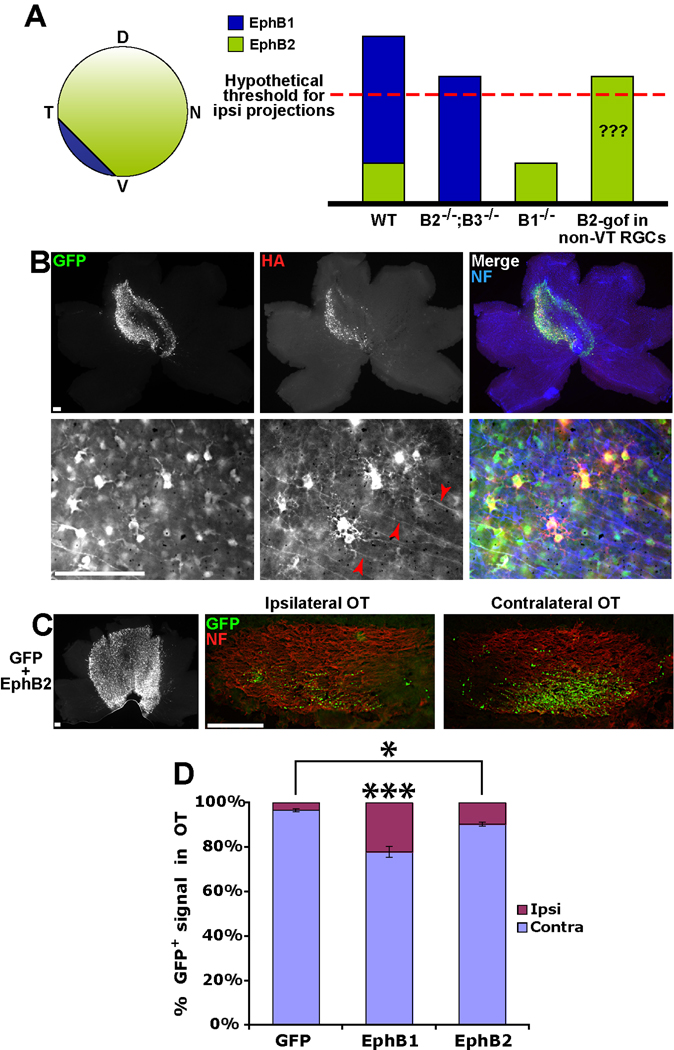

One possibility, which is consistent with the current data (Williams et al., 2003), is that EphB1 expression in the VT retina increases the total EphB receptor level (EphB1+EphB2+EphB3) above a certain threshold, which in turn could drive RGC fibers into the ipsilateral optic tract (Fig. 5A). Thus, the absolute level of EphB receptors may control retinal axon divergence at the optic chiasm, similar to the retinocollicular projection (Brown et al., 2000; Lemke and Reber, 2005). To address this hypothesis, we introduced HA-tagged EphB2 into embryonic RGCs via in utero retinal electroporation (n=13, Fig. 5B). If the total EphB receptor levels drive the ipsilateral projection, then we would expect to see a similar level of GFP+ ipsilateral projections compared to EphB1. However, ectopic EphB2 expression produced a significantly weaker increase in GFP+ ipsilateral RGC projections (10.0%) compared to EphB1 (22.3%) (Fig. 5C,D, and Fig. 3). Thus, EphB2 is less efficient in redirecting RGC projections ipsilaterally compared to EphB1.

Figure 5. EphB1 induces a greater proportion of GFP+ ipsilateral projections compared to EphB2.

(A) Cartoon depicting expression patterns of EphB1 and EphB2 in the embryonic mouse retina. Graph represents a scenario, consistent with current data from EphB knockout mice, in which the total expression level of EphB receptors exceeds a hypothetical threshold and drives the ipsilateral projection, rather than the specificity of EphB1. We tested whether ectopic expression of EphB2 in RGCs (EphB2 gain-of-function (B2-gof), right column) supports the validity of this model. (B) Low power and high power images of E18.5 retina electroporated with GFP+EphB2 at E14.5. Of note, HA expression is visible on intraretinal RGC axons electroporated with EphB2 (red arrowheads), but HA was rarely observed in EphB1+ axons (Fig. 2A). (C) Representative example of retina and optic tracts electroporated with GFP+EphB2. (D) EphB1 is significantly more efficient at directing ipsilateral projections compared to EphB2 (22% vs. 10%), but EphB2 does induce a greater percentage of uncrossed projections compared to GFP alone (10% vs. 3%). n ≥ 13 embryos for each condition, from ≥ 3 separate electroporation experiments. Data represent mean ± s.e.m., all scale bars = 100 µm. ANOVA: F(2,41) = 31.52, p < .0001. Modified t-tests: * = p < .05, *** = p < .0001.

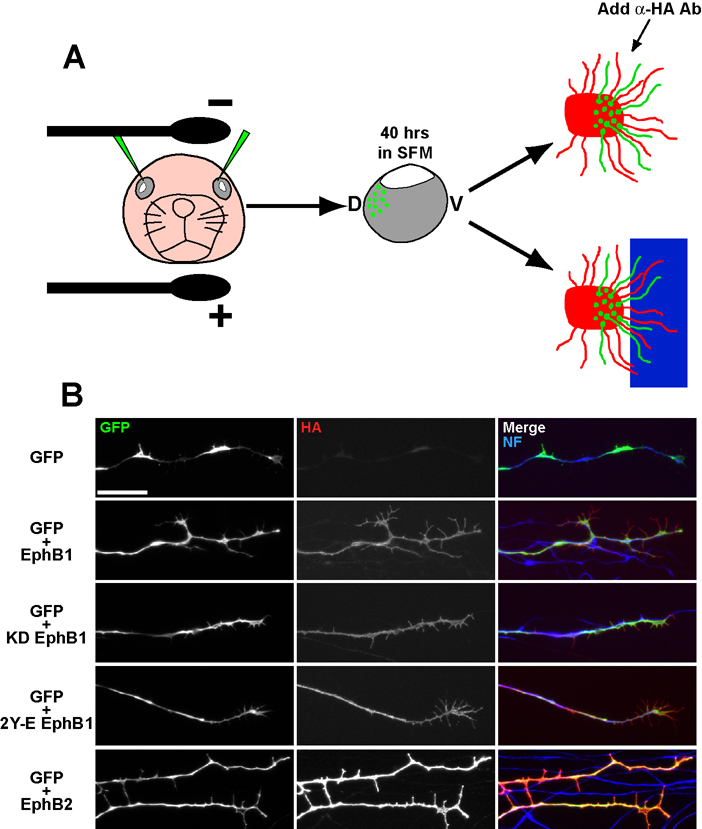

This effect could arise from weaker expression levels of EphB2 compared to EphB1. To examine surface expression levels of EphB1 and EphB2, we developed a novel ex vivo retinal electroporation technique to efficiently introduce GFP+EphB1/B2 into peripheral dorsal RGCs (EphB1−/EphB2−) and prepare GFP+ explants from these retina (Fig. 6A; see methods). This approach allows for greater control of injection sites compared to in utero electroporation. After culturing GFP+ retinal explants for 20 hours, α-HA antibody was bath applied to live explants in order to label HA-tagged EphB proteins on the cell surface. Surprisingly, HA immunostaining was consistently more intense on EphB2 electroporated RGC axons compared to fibers from EphB1 electroporated explants (Fig. 6B). Thus, EphB1 is more efficient at inducing an ipsilateral RGC projection compared to EphB2, even though exogenous EphB2 is expressed at higher surface levels on individual neurons.

Figure 6. Ex vivo retinal electroporations reveal that EphB1 and EphB2 are expressed at different surface levels.

(A) Cartoon diagramming ex vivo retinal electroporation. DNA is injected into dorsal retina and electroporated. Retinae are removed and cultured in serum-free medium (SFM) for ~40 hours, and then explants are prepared from GFP+ retinal regions and plated on laminin (for live HA staining) or adjacent to ephrin-B2 substrate borders. (B) Live HA staining reveals that EphB2 is expressed at higher levels compared to RGC axons from EphB1, KD EphB1 and 2Y-E EphB1 electroporated retina. Scale bar = 20 µm.

The stronger EphB2 expression levels could stimulate EphB2 kinase activity, potentially desensitizing these EphB2+ axons to ephrin-B2. To examine this possibility, we plated GFP+ dorsal retinal explants adjacent to ephrin-B2 or control Fc border substrates (Petros et al., 2006) (Fig. 6A). As expected, GFP+ axons electroporated with GFP and GFP+KD EphB1 were not repelled by ephrin-B2 substrates, while GFP+ axons from EphB1 electroporated explants were repelled at ephrin-B2 borders (Fig. 7). RGC axons electroporated with GFP+EphB2 also displayed strong repulsion upon contacting ephrin-B2 substrates (Fig. 7), indicating that exogenous EphB2+ RGCs are still capable of responding to ephrin-B2 in vitro, even when expressed at very high surface levels.

Several conclusions can be drawn from this series of experiments. First, EphB1 is significantly more efficient than EphB2 in converting crossed RGC fibers to an ipsilateral fate. Second, since EphB2 is expressed at higher surface levels, the specific EphB receptor subtype (EphB1) is more important for driving the ipsilateral projection than the net EphB receptor expression levels. Thus, certain features of the EphB1 receptor allow it to more efficiently direct RGC fibers to an ipsilateral fate.

The extracellular and juxtamembrane domains of EphB1 are required for maximal efficiency in driving the uncrossed projection

Very few studies have examined different domains and signaling capabilities between EphB1 and EphB2, and rarely (if ever) has this been examined in vivo. One report indicated that the adaptor protein Grb7 might interact specifically with EphB1 (at tyrosine 928) and not with other EphB receptors (Han et al., 2002). Grb7 is activated upon netrin-1 stimulation (Tsai et al., 2007), indicating that Grb7 may be involved in axon guidance decisions. We electroporated an EphB1 construct with a mutated Grb7 interaction site (EphB1Y928F) into embryonic retina, but these embryos displayed an increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections similar to WT EphB1 electroporations (19.7%, n=10, data not shown). Thus, this tyrosine residue (and Grb7 interaction site) is dispensable for RGC repulsion at the optic chiasm.

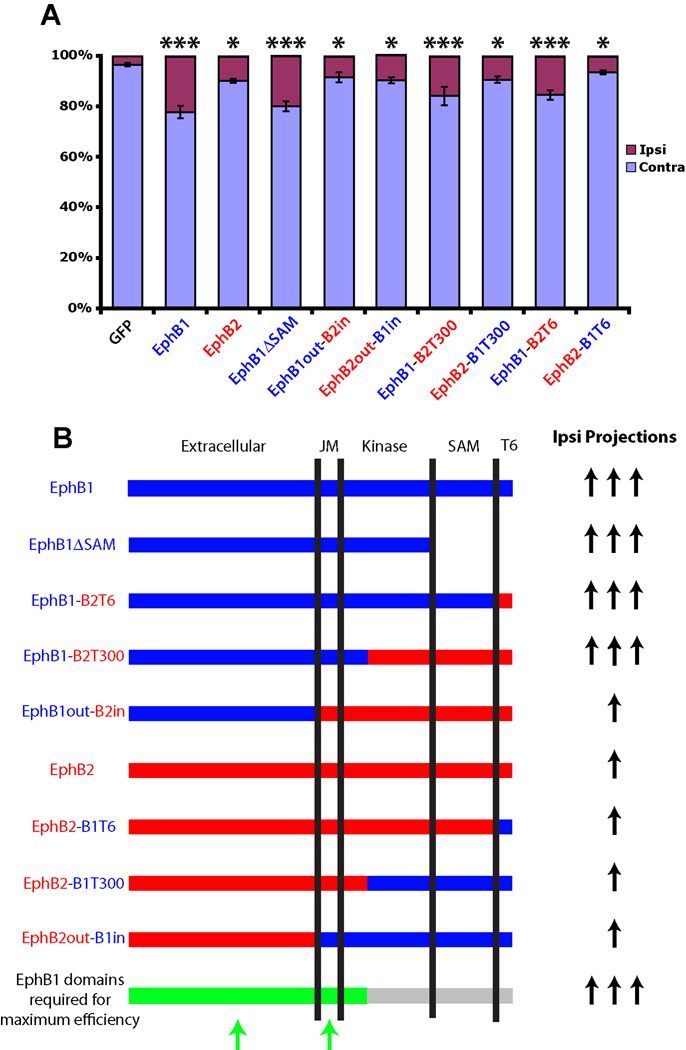

To further address the differences in efficiency between EphB1 and EphB2, we prepared chimeric receptors whereby the intracellular portion of EphB1 was replaced by EphB2 (EphB1out-B2in), and vice versa (EphB2out-B1in). We hypothesized that one chimera would behave like EphB1 and the other like EphB2, revealing whether the differences in efficiency are due to the extracellular or intracellular domains. However, both EphB1out-B2in (n=14) and EphB2out-B1in (n=17) induced a weak increase in the percentage of GFP+ ipsilateral projections (~10%), similar to full-length EphB2 (Fig. 8). Thus, neither chimeric receptor was capable of increasing ipsilateral projections as efficiently as WT EphB1, implying that portions of both the intracellular and extracellular domains are required for efficiently redirecting RGC axons ipsilaterally.

Figure 8. The extracellular and juxtamembrane domains of EphB1 are required for maximum efficiency in rerouting RGC axons ipsilaterally.

(A) Graph displaying the percentages of GFP+ ipsilateral projections for GFP, EphB1, EphB2, EphB1ΔSAM, and the chimeric EphB1-EphB2 receptors constructs. EphB1 regions are labeled blue, EphB2 regions are labeled red. *** labeled columns are statistically identical, with all of these mutants having significantly higher GFP+ ipsilateral projections compared to GFP alone (p < .0001) and compared to * labeled mutants (p < .05). (One exception is WT EphB1, which had a significantly higher percentage of GFP+ uncrossed projections compared to EphB1-B2T300 and EphB1-B2T6 mutants (p < .05)). * labeled mutants are statistically identical, with all of these columns having significantly higher GFP+ ipsilateral projections compared to GFP alone (p < .05, except for EphB2-B1T6, which is not significantly different from GFP) and a significantly lower GFP+ ipsilateral projections compared to *** labeled mutants (p < .05). Data represent mean ± s.e.m. ANOVA: F(9,121) = 13.59, p < .0001. All scale bars = 100 µm. (B) Summary of EphB1 and EphB2 chimeric constructs and their ability to convert crossed RGCs to an uncrossed fate. Both the juxtamembrane (JM) region and a portion of the extracellular domain (green domains on bottom bar) are required for maximal efficiency in giving rise to ipsilateral projections.

To further investigate this issue, we compared the EphB1 and EphB2 sequences and found that EphB2 ends in an IQSVEV motif, while EphB1 ends in SPSVMA (Supplementary Fig. 2). The IQSVEV sequence of EphB2 is a PDZ-binding motif (PBM) required for interaction with the PDZ domain of the ras-binding protein AF6 (Hock et al., 1998) and is important for clustering AMPA receptors at the synapse (Kayser et al., 2006). While other EphB receptors have PBMs similar to EphB2 (Torres et al., 1996; Hock et al., 1998), the terminal 6 residues of EphB1 are not predicted to be a PBM.

To determine if the lack of a PBM underlies the functional differences between EphB1 and EphB2, we prepared chimeric receptors where the terminal 6 (T6) residues were swapped (EphB1-B2T6 and EphB2-B1T6). When electroporated into embryonic RGCs, EphB1-B2T6 (n=12) produced a strong increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections, similar to EphB1, while EphB2-B1T6 (n=10) produced a weaker increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections, similar to EphB2 (Fig. 8). Thus, the PBM (or lack thereof) does not give rise to the different effects of EphB1 and EphB2 at the optic chiasm.

Eph receptors interact with each other via the SAM domain when clustering into larger oligomers, and differences in clustering efficiencies may underlie the functional differences between EphB1 and EphB2 (Stein et al., 1998a). We prepared chimeric receptors where we swapped the terminal 300 residues, which include the PBM, SAM domain and most of the kinase domains (EphB1-B2T300 and EphB2-B1T300). In addition, we prepared a truncated EphB1 receptor lacking a SAM domain (EphB1ΔSAM). EphB1ΔSAM (n=12) produced an increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections similar to full-length EphB1 electroporations (Fig. 8), indicating that the SAM domain is not required for driving crossed RGC fibers ipsilaterally. EphB1-B2T300 (n=11) produced a large increase in uncrossed GFP+ fibers, similar to EphB1, and EphB2-B1T300 (n=11) inducing a significantly weaker percentage of ipsilateral projections, similar to EphB2 (Fig. 8).

The results of these chimera studies are summarized in Fig. 8B. The EphB1 extracellular region is required for efficiently converting crossed fibers to an uncrossed fate. However, electroporation of the EphB1out-B2in construct produced only a weak increase in ipsilateral projections, indicating that simply having the EphB1 extracellular domain is not sufficient for maximal efficiency. Comparison of the EphB1out-B2in and EphB1out-B2T300 chimeras reveals that the EphB1 juxtamembrane (JM) region is required for the higher efficiency of EphB1. However, the JM region is not the sole determinant, as EphB2out-B1in (which includes the EphB1 JM region) produces a minor increase in ipsilateral projections (Fig. 8B). Thus, both the JM domain and the extracellular domain of EphB1 are required to most efficiently redirect RGC projections to an uncrossed fate.

DISCUSSION

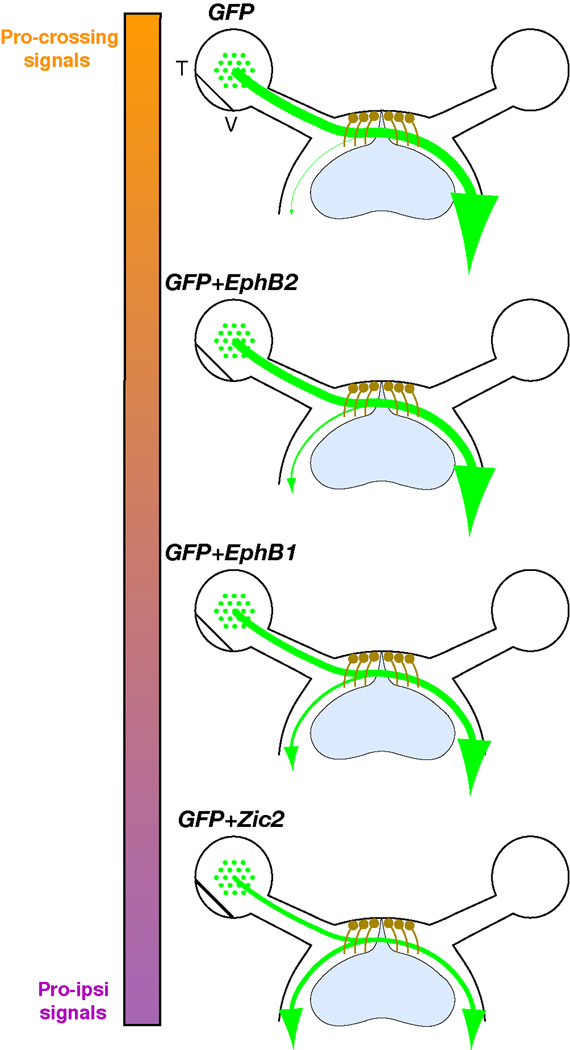

In this study, we demonstrate that ectopic EphB1 expression is sufficient to convert a significant proportion of crossed RGC projections to an uncrossed trajectory. Comparison of EphB1 and EphB2 revealed that the specific subtype of Eph receptor (EphB1) is more important than the total levels of EphB receptors in driving the ipsilateral projection. Additionally, we found that both the extracellular and JM domains of EphB1 are required to efficiently redirect RGC axons ipsilaterally. Thus, crossed RGC fibers can be converted to an ipsilateral fate by ectopic expression of EphB1 and EphB2 with varying degrees of efficiency (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Effects of ectopic gene expression on retinal axon divergence at the optic chiasm.

Diagrams summarize retinal fiber projection at the optic chiasm after ectopic expression of EphB1, EphB2 and Zic2 in non-VT RGCs. Nearly all GFP+ axons cross the midline when GFP alone is electroporated into embryonic retina. A moderate increase in GFP+ ipsilateral projections is observed in retina electroporated with GFP+EphB2 (~10%), while RGCs electroporated with GFP+EphB1 display an even greater increase in uncrossed GFP+ fibers (~22%). The strongest effect is observed with Zic2, which is capable of converting ~50% of non-VT GFP+ RGC axons to an ipsilateral fate. Colored bar represents theoretical relative percentages of ‘pro-crossing’ (orange) and ‘pro-ipsilateral’ (purple) signals in GFP+ RGCs.

Differences between EphB1 and EphB2 in driving the ipsilateral projection

EphB1 is significantly more efficient at redirecting RGC axons to an uncrossed fate compared to EphB2, even though EphB2 is expressed at higher surface levels in our experimental paradigm. Thus, the specific subtype of EphB receptor (in this case EphB1) is more important than net EphB receptor levels for driving RGC projections ipsilaterally. These results support the notion that EphB1 appears to be the sole EphB receptor that directs the mature ipsilateral projection (Williams et al., 2003), despite the presence of EphB2 and EphB3 in the peripheral VT retina.

It is possible that the differences in EphB1 and EphB2 surface levels are an artifact of exogenous overexpression. However, introduction of Zic2 into VT explants in vitro did not induce a further increase in EphB1 expression (Lee et al., 2008), indicating that cellular mechanisms may prevent EphB1 from being expressed at high levels. Additionally, significant differences in EphB1 and EphB2 expression levels and cellular localization were also observed after electroporation into chick motor neurons (A. Kania, personal communication). Thus, RGCs may possess endogenous mechanisms to limit EphB1 expression levels.

We found that exogenous EphB1+ and EphB2+ RGC axons from dorsal explants displayed similar levels of repulsion to ephrin-B2 substrates (Fig. 7), in contrast to their different effects in vivo. We repeated these border assays with lower ephrin-B2 substrate concentrations, but we were unable to identify ephrin-B2 concentrations at which repulsion was significantly different between EphB1+ and EphB2+ axons (data not shown). The lack of chiasm cells and ‘pro-crossing’ molecules in the border substrate likely make this environment more repulsive than the optic chiasm. Similar contradictory findings were observed with the crossed RGC projection, whereby perturbing Nr-CAM reduced neurite extension from dorsotemporal (DT) RGC axons in vitro, but DT RGC projections were unaffected in Nr-CAM−/− mice (Williams et al., 2006). These observations emphasize that results obtained from in vitro models, while reductionist and precise, need to be validated in vivo.

Our results from the EphB1-EphB2 chimeric receptor electroporations reveal that both the EphB1 JM region and extracellular domain are required for EphB1 to most efficiently convert crossed RGC projections to an uncrossed fate. The JM region contains two tyrosine residues that are important interaction sites for numerous downstream signaling proteins (Pasquale, 2008). It is possible that certain proteins interact more efficiently with ephrin-B2-bound EphB1 compared to ephrin-B2-bound EphB2. A previous study prepared chimeric receptors with the EphB extracellular domain joined to the intracellular TrkB domain. Upon stimulation with ephrin-B2, the EphB1-TrkB construct produced a functional response in the focus formation assay whereas EphB2-TrkB lacked this response (Brambilla et al., 1996). Thus, EphB1 and EphB2 may have different signaling capabilities upon ephrin-B2 binding despite their similar binding affinities to ephrin-B2.

Additionally, the conformation of the JM region is important for blocking kinase activity in the inactive form of the receptor (Wybenga-Groot et al., 2001), and various Eph receptor-ligand pairs undergo different dimeric or tetrameric architectural arrangements (Himanen et al., 2004). Thus, it is highly plausible that ephrin-B2 induces different conformational changes upon binding EphB1 and EphB2 that could affect their ability to oligomerize and/or stimulate specific signaling components to interact with the JM domain.

EphB1 kinase activity is required for directing the ipsilateral projection, but the SAM domain is dispensable

Results from the KD EphB1 and 2Y-E EphB1 electroporations highlight the requirement for kinase activity and downstream signaling cascades in driving the ipsilateral RGC projection. Previous studies have identified numerous proteins that interact with the two JM phosphorylated tyrosine residues of Eph receptors, such as Src kinases, RasGAP, Nck, and the Rho GEF Vav2 (Stein et al., 1998b; Elowe et al., 2001; Vindis et al., 2003; Cowan et al., 2005; Pasquale, 2005). Of interest, several of these signaling cascades converge on Rac/Rho signaling, an important mechanism controlling growth cone behavior. It would be interesting for future studies to examine which of these downstream signaling cascades are required for ephrin-B2-induced RGC growth cone repulsion at the optic chiasm. Additionally, there is some indication that the 2Y-E mutation produces a constitutively active Eph receptor (Egea et al., 2005), and thus we cannot rule out that the inability of 2Y-E EphB1 to reroute RGC fibers ipsilaterally arises from a constitutively active kinase domain.

Our results demonstrate that the SAM domain is dispensable for increasing the percentage of GFP+ ipsilateral RGC fibers. It has been well documented that the SAM domain is important for Eph receptor dimerization (Pasquale, 2005), but overexpression of EphB1ΔSAM might allow for ligand-bound EphB1 to trans-phosphorylate adjacent EphB1 receptors despite the absence of their primary dimerization interface. However, formation of the CST, anterior commissure, and thalamocortical projections are essentially normal in EphA4ΔSAM mutant mice (Kullander et al., 2001; Dufour et al., 2006). These observations, combined with our findings on EphB1ΔSAM function at the chiasm, strengthen the necessity for a better understanding of the in vivo functional relevance of the SAM domain.

Limitations on converting RGC projections to an ipsilateral fate

While ectopic EphB1 expression induces a significant increase in GFP+ ipsilateral RGC fibers, the majority of EphB1+ RGCs cross the midline. One possibility is that some EphB1+ fibers reach the chiasm and cross the midline after downregulation of ephrin-B2 at E16.5 (Williams et al., 2003), but an additional increase in GFP+ ipsilateral fibers was not observed when EphB1 was electroporated one day earlier at E13.5 (Fig. 4). A more likely explanation is that EphB1+ RGC axons that traverse the midline continue to express ‘pro-crossing’ factors (possibly CAMs or Islet2-regulated genes (Pak et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2006)), and ectopic expression of EphB1 may not be sufficient to overcome these pro-crossing mechanisms. In support of this hypothesis, we found that Zic2 converts a significantly higher percentage of axons to an ipsilateral fate (Fig. 9). Furthermore, Zic2 induces a small increase in ipsilateral projections when introduced into E13.5 retina of EphB1−/− mice (Garcia-Frigola et al., 2008). Thus, Zic2 is more potent in shifting the molecular balance of non-VT RGCs towards an ipsilateral trajectory, likely by downregulating pro-crossing factors and/or upregulating other pro-ipsilateral factors besides EphB1 (Fig. 9).

Exogenous EphB1 may interact with endogenous ephrin-Bs, which are expressed in a high dorsal-to-low ventral gradient in embryonic RGCs (McLaughlin and O'Leary, 2005). Since many RGCs electroporated with EphB1 are in the dorsal hemiretina, they likely express high levels of both EphB1 and ephrin-Bs. EphAs and ephrin-As interact in cis when co-expressed in RGCs to modulate the function of EphA receptors (Hornberger et al., 1999; Carvalho et al., 2006). Conversely, EphAs and ephrin-As in motor neurons are localized to distinct membrane domains, preventing cis interactions and enabling EphAs and ephrin-As to retain their individual functions (Marquardt et al., 2005). Whether EphB-ephrin-B interactions occur in cis in the retina to modulate EphB activity, or instead they segregate into distinct membrane domains, remains unknown.

Two roles for Eph-ephrin signaling in neural development

Eph-ephrin interactions appear to have two prominent roles in axon guidance. First, Eph receptors and ephrins are often expressed as gradients in the origin and target region, as in the retinotectal pathway (McLaughlin and O'Leary, 2005) and thalamocortical projections (Vanderhaeghen et al., 2000; Dufour et al., 2003; Bolz et al., 2004; Cang et al., 2005). Proper topographic targeting in these systems is guided by the relative expression levels of Eph receptors and ephrins rather than the actual subtype of Eph receptor (Brown et al., 2000; Cang et al., 2005; Lemke and Reber, 2005; Torii and Levitt, 2005). Second, Eph-ephrin signaling is prominent at intermediate targets and decision regions, specifically at midline structures such as the optic chiasm (Williams et al., 2003), corpus callosum (Mendes et al., 2006), and spinal cord (Kadison et al., 2006; Kullander et al., 2001). Our results demonstrate that the specific subtype of Eph receptor, EphB1, is required for efficiently driving RGC projections ipsilaterally. Thus, in contrast to target regions, Eph receptor specificity trumps net Eph receptor levels at the optic chiasm. It will be important now to characterize functional differences between Eph receptors at other decision points, and to examine whether specific subtypes of Eph receptors or net Eph receptor levels guide these decisions.

Supplementary Material

Left, Representative coronal sections through the anterior, middle and posterior optic tract used for analysis. Phase images are overlaid with neurofilament staining (red) to visualized optic tracts. Scale bar = 250 µm. Right, GFP signal is taken (from higher power images) in the ipsilateral (I1, I2, I3) and contralateral (C1, C2, C3) optic tracts to calculate the percentage of GFP+ signal in the ipsilateral optic tract for each embryo.

Red Y’s = tyrosine residues mutated for 2Y-E EphB1 mutant and Y929F EphB1 mutant, green K = residue mutated for KD EphB1 mutant. The transmembrane (TM) domain, kinase domain, SAM domain, and PDZ binding motifs are highlighted. The juxtamembrane (JM) region lies between the transmembrane domain and the kinase domain.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank J.W. Tsai and R. Vallee for help with the electroporation experiments, S. Williams and A. Beg for advice on the molecular cloning, P. Scheiffele, T. Jessell, J. Dodd, E. Herrera, F. Doetsch, H. Wichterle, P. Faust and S. Brown for sharing reagents and equipment, and R. Blazeski and M. Melikyan for expert technical assistance. We are grateful to T. Sakurai, A. Kania, P. Scheiffele and members of the Mason lab for helpful discussion and comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by N.I.H grants F31 NS051008 (T.J.P) and RO1 EY12736 (C.M.).

REFERENCES

- Bergemann AD, Cheng HJ, Brambilla R, Klein R, Flanagan JG. ELF-2, a new member of the Eph ligand family, is segmentally expressed in mouse embryos in the region of the hindbrain and newly forming somites. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4921–4929. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgbauer E, Cowan CA, Sretavan DW, Henkemeyer M. Kinase independent function of EphB receptors in retinal axon pathfinding to the optic disc from dorsal but not ventral retina. Development. 2000;127:1231–1241. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolz J, Uziel D, Muhlfriedel S, Gullmar A, Peuckert C, Zarbalis K, Wurst W, Torii M, Levitt P. Multiple roles of ephrins during the formation of thalamocortical projections: maps and more. J Neurobiol. 2004;59:82–94. doi: 10.1002/neu.10346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla R, Bruckner K, Orioli D, Bergemann AD, Flanagan JG, Klein R. Similarities and differences in the way transmembrane-type ligands interact with the Elk subclass of Eph receptors. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:199–209. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Yates PA, Burrola P, Ortuno D, Vaidya A, Jessell TM, Pfaff SL, O'Leary DD, Lemke G. Topographic mapping from the retina to the midbrain is controlled by relative but not absolute levels of EphA receptor signaling. Cell. 2000;102:77–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cang J, Kaneko M, Yamada J, Woods G, Stryker MP, Feldheim DA. Ephrin-as guide the formation of functional maps in the visual cortex. Neuron. 2005;48:577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho RF, Beutler M, Marler KJ, Knoll B, Becker-Barroso E, Heintzmann R, Ng T, Drescher U. Silencing of EphA3 through a cis interaction with ephrinA5. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:322–330. doi: 10.1038/nn1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CW, Shao YR, Sahin M, Shamah SM, Lin MZ, Greer PL, Gao S, Griffith EC, Brugge JS, Greenberg ME. Vav family GEFs link activated Ephs to endocytosis and axon guidance. Neuron. 2005;46:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Egea J, Kullander K, Klein R, Vanderhaeghen P. Genetic analysis of EphA-dependent signaling mechanisms controlling topographic mapping in vivo. Development. 2006;133:4415–4420. doi: 10.1242/dev.02623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Seibt J, Passante L, Depaepe V, Ciossek T, Frisen J, Kullander K, Flanagan JG, Polleux F, Vanderhaeghen P. Area specificity and topography of thalamocortical projections are controlled by ephrin/Eph genes. Neuron. 2003;39:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart J, Swartz M, Koblar SA, Pasquale EB, Tanaka H, Krull CE. Expression of EphA4, ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A5 during axon outgrowth to the hindlimb indicates potential roles in pathfinding. Dev Neurosci. 2000;22:237–250. doi: 10.1159/000017446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowe S, Holland HJ, Kulkarni S, Pawson T. Downregulation of the Ras-Mitogen-Activated protein kinase pathway by the EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for Ephrin-induced neurite retraction. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7429–7441. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7429-7441.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea J, Nissen UV, Dufour A, Sahin M, Greer P, Kullander K, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Greenberg ME, Kiehn O, Vanderhaeghen P, Klein R. Regulation of EphA4 Kinase Activity Is Required for a Subset of Axon Guidance Decisions Suggesting a Key Role for Receptor Clustering in Eph Function. Neuron. 2005;47:515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JG, Vanderhaeghen P. The ephrins and Eph receptors in neural development. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:309–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NW, Holland SJ, Valenzuela DM, Flenniken A, Pan L, Ryan TE, Henkemeyer M, Strebhardt K, Hirai H, Wilkinson DG, Pawson T, Davis S, Yancopoulos GD. Eph receptors and ligands comprise two major specificity subclasses and are reciprocally compartmentalized during embryogenesis. Neuron. 1996;17:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Frigola C, Carreres MI, Vegar C, Herrera E. Gene delivery into mouse retinal ganglion cells by in utero electroporation. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Frigola C, Carreres MI, Vegar C, Mason C, Herrera E. Zic2 promotes axonal divergence at the optic chiasm midline by EphB1-dependent and-independent mechanisms. Development. 2008;135:1833–1841. doi: 10.1242/dev.020693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DC, Shen TL, Miao H, Wang B, Guan JL. EphB1 associates with Grb7 and regulates cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45655–45661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkemeyer M, Itkis OS, Ngo M, Hickmott PW, Ethell IM. Multiple EphB receptor tyrosine kinases shape dendritic spines in the hippocampus. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1313–1326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera E, Brown L, Aruga J, Rachel RA, Dolen G, Mikoshiba K, Brown S, Mason CA. Zic2 patterns binocular vision by specifying the uncrossed retinal projection. Cell. 2003;114:545–557. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen JP, Chumley MJ, Lackmann M, Li C, Barton WA, Jeffrey PD, Vearing C, Geleick D, Feldheim DA, Boyd AW, Henkemeyer M, Nikolov DB. Repelling class discrimination: ephrin-A5 binds to and activates EphB2 receptor signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:501–509. doi: 10.1038/nn1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock B, Bohme B, Karn T, Yamamoto T, Kaibuchi K, Holtrich U, Holland S, Pawson T, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Strebhardt K. PDZ-domain-mediated interaction of the Eph-related receptor tyrosine kinase EphB3 and the ras-binding protein AF6 depends on the kinase activity of the receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9779–9784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger MR, Dutting D, Ciossek T, Yamada T, Handwerker C, Lang S, Weth F, Huf J, Wessel R, Logan C, Tanaka H, Drescher U. Modulation of EphA receptor function by coexpressed ephrinA ligands on retinal ganglion cell axons. Neuron. 1999;22:731–742. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadison SR, Makinen T, Klein R, Henkemeyer M, Kaprielian Z. EphB receptors and ephrin-B3 regulate axon guidance at the ventral midline of the embryonic mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8909–8914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania A, Jessell TM. Topographic motor projections in the limb imposed by LIM homeodomain protein regulation of Ephrin-A:EphA interactions. Neuron. 2003;38:581–596. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser MS, McClelland AC, Hughes EG, Dalva MB. Intracellular and trans-synaptic regulation of glutamatergic synaptogenesis by EphB receptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12152–12164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3072-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K, Mather NK, Diella F, Dottori M, Boyd AW, Klein R. Kinase-dependent and kinase-independent functions of EphA4 receptors in major axon tract formation in vivo. Neuron. 2001;29:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Petros TJ, Mason CA. Zic2 regulates retinal ganglion cell axon avoidance of ephrinB2 through inducing expression of the guidance receptor EphB1. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5910–5919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0632-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke G, Reber M. Retinotectal mapping: new insights from molecular genetics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:551–580. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.022403.093702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luria V, Krawchuk D, Jessell TM, Laufer E, Kania A. Specification of motor axon trajectory by Ephrin-B:EphB signaling: symmetrical control of axonal patterning in the developing limb. Neuron. 2008;60:1039–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RC, Blazeski R, Godement P, Mason CA. Retinal axon divergence in the optic chiasm: uncrossed axons diverge from crossed axons within a midline glial specialization. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3716–3729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03716.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T, Shirasaki R, Ghosh S, Andrews SE, Carter N, Hunter T, Pfaff SL. Coexpressed EphA receptors and ephrin-A ligands mediate opposing actions on growth cone navigation from distinct membrane domains. Cell. 2005;121:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Cepko CL. Electroporation and RNA interference in the rodent retina in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235688100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin T, O'Leary DD. Molecular gradients and development of retinotopic maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:327–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes SW, Henkemeyer M, Liebl DJ. Multiple Eph receptors and B-class ephrins regulate midline crossing of corpus callosum fibers in the developing mouse forebrain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:882–892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3162-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Brennan C, Johnson KG, Shewan D, Harris WA, Holt CE. Ephrin-B regulates the Ipsilateral routing of retinal axons at the optic chiasm. Neuron. 2000;25:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak W, Hindges R, Lim YS, Pfaff SL, O'Leary DD. Magnitude of binocular vision controlled by islet-2 repression of a genetic program that specifies laterality of retinal axon pathfinding. Cell. 2004;119:567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph receptor signalling casts a wide net on cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:462–475. doi: 10.1038/nrm1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros TJ, Williams SE, Mason CA. Temporal regulation of EphA4 in astroglia during murine retinal and optic nerve development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros TJ, Rebsam A, Mason CA. Retinal axon growth at the optic chiasm: to cross or not to cross. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:295–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Schoecklmann HO, Schroff AD, Van Etten RL, Daniel TO. Eph receptors discriminate specific ligand oligomers to determine alternative signaling complexes, attachment, and assembly responses. Genes Dev. 1998a;12:667–678. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Huynh-Do U, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. Nck recruitment to Eph receptor, EphB1/ELK, couples ligand activation to c-Jun Kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998b;273:1303–1308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii M, Levitt P. Dissociation of corticothalamic and thalamocortical axon targeting by an EphA7-mediated mechanism. Neuron. 2005;48:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M, Gomez-Pardo E, Gruss P. Pax2 contributes to inner ear patterning and optic nerve trajectory. Development. 1996;122:3381–3391. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai NP, Bi J, Wei LN. The adaptor Grb7 links netrin-1 signaling to regulation of mRNA translation. Embo J. 2007;26:1522–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhaeghen P, Lu Q, Prakash N, Frisen J, Walsh CA, Frostig RD, Flanagan JG. A mapping label required for normal scale of body representation in the cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:358–365. doi: 10.1038/73929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindis C, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO, Huynh-Do U. EphB1 recruits c-Src and p52Shc to activate MAPK/ERK and promote chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:661–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LC, Dani J, Godement P, Marcus RC, Mason CA. Crossed and uncrossed retinal axons respond differently to cells of the optic chiasm midline in vitro. Neuron. 1995;15:1349–1364. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SE, Grumet M, Colman DR, Henkemeyer M, Mason CA, Sakurai T. A role for Nr-CAM in the patterning of binocular visual pathways. Neuron. 2006;50:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SE, Mann F, Erskine L, Sakurai T, Wei S, Rossi DJ, Gale NW, Holt CE, Mason CA, Henkemeyer M. Ephrin-B2 and EphB1 mediate retinal axon divergence at the optic chiasm. Neuron. 2003;39:919–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wybenga-Groot LE, Baskin B, Ong SH, Tong J, Pawson T, Sicheri F. Structural basis for autoinhibition of the Ephb2 receptor tyrosine kinase by the unphosphorylated juxtamembrane region. Cell. 2001;106:745–757. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun ME, Johnson RR, Antic A, Donoghue MJ. EphA family gene expression in the developing mouse neocortex: regional patterns reveal intrinsic programs and extrinsic influence. J Comp Neurol. 2003;456:203–216. doi: 10.1002/cne.10498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisch AH, Pazzagli C, Freeman AL, Schneller M, Hadman M, Smith JW, Ruoslahti E, Pasquale EB. Replacing two conserved tyrosines of the EphB2 receptor with glutamic acid prevents binding of SH2 domains without abrogating kinase activity and biological responses. Oncogene. 2000;19:177–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Left, Representative coronal sections through the anterior, middle and posterior optic tract used for analysis. Phase images are overlaid with neurofilament staining (red) to visualized optic tracts. Scale bar = 250 µm. Right, GFP signal is taken (from higher power images) in the ipsilateral (I1, I2, I3) and contralateral (C1, C2, C3) optic tracts to calculate the percentage of GFP+ signal in the ipsilateral optic tract for each embryo.

Red Y’s = tyrosine residues mutated for 2Y-E EphB1 mutant and Y929F EphB1 mutant, green K = residue mutated for KD EphB1 mutant. The transmembrane (TM) domain, kinase domain, SAM domain, and PDZ binding motifs are highlighted. The juxtamembrane (JM) region lies between the transmembrane domain and the kinase domain.