Abstract

Reduced spine densities and an age-dependent accumulation of amyloid β and tau pathology are shared features of Down syndrome (DS) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Spine morphology and the synaptic plasticity that supports learning both depend upon the actin cytoskeleton, suggesting that disturbances in actin regulatory signaling might underlie spine defects in both disorders. The present study evaluated synaptic levels of two proteins that promote filamentous actin stabilization, the Rho GTPase effector p21-activated kinase 3 (PAK3) and Arp2, in DS versus AD. Fluorescent deconvolution tomography was used to determine postsynaptic PAK3 and Arp2 levels for large numbers of excitatory synapses in parietal cortex of individuals with DS plus AD pathology or AD alone relative to age-matched controls. Although numbers of excitatory synapses were not different between groups, synaptic PAK3 levels were greatly reduced in DS+AD and AD individuals versus controls. Synaptic Arp2 levels also were reduced in both disorders, but to a greater degree in AD. Western blotting detected reduced Arp2 levels in the AD group, but there was no correlation with phosphorylated tau levels suggesting that Arp2 loss does not contribute to mechanisms that drive tau pathology progression. Overall, the results demonstrate marked synaptic disturbances in two actin regulatory proteins in adult DS and AD brains, with greater effects in individuals with AD alone. As both PAK and the Arp2/3 complex play roles in the actin stabilization that supports synaptic plasticity, reductions in these proteins at synapses may be early events in spine dysfunction that contribute to cognitive impairment in these disorders.

Keywords: dendritic spine, Arp2/3 complex, neocortex, tau, actin cytoskeleton, human

Introduction

Down Syndrome (DS) is a genetic intellectual disability disorder, with individuals generally exhibiting mild to moderate cognitive impairment. There is considerable evidence that virtually all adults with DS exhibit neuropathology characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) including ß-amyloid (Aß) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles by 40 years of age, although not all go on to develop an AD-like cognitive decline (19). In AD, an early and progressive loss of spine synapses is thought to be a major driver of cognitive decline (1). It is widely assumed that Aß and tau pathology underlie this synaptic failure in AD and, by extension, DS (5) but the degree to which spine dysfunction in the two disorders overlap mechanistically is unknown.

Neuronal features in DS and AD suggest that both disorders involve disturbances in the filamentous (F-) actin cytoskeleton. DS brains exhibit reductions in cortical dendritic branching, reduced spine density, and abnormal spine structure (24, 31, 33, 34). AD is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration including dystrophic dendrites, dendritic branch loss, and an early and progressive loss of dendritic spines that correlates with cognitive decline (1, 3, 14, 45). Abnormalities in F-actin are seen in AD and DS: cofilin-actin rods are present in brains with AD pathology (4) and decreased expression of the actin-binding protein drebrin, that opposes cofilin-mediated severing of F-actin (15), has been reported for both disorders (56). These abnormalities may contribute to spine dysfunction and other cytoskeletal disturbances such as neurofibrillary tangles (4).

Synaptic structure and its reorganization in association with enduring synaptic plasticity are regulated by several signaling pathways that control F-actin polymerization, branching, and stabilization (9, 48). A key nodal element in these pathways is p21-activated kinase (PAK) that simultaneously inhibits severing and promotes branching of F-actin (46). PAK inhibits cofilin severing activities via Lim Kinase 1 (13), and engages cortactin which in turns recruits the Arp2/3 complex to initiate F-actin branching and stabilization (59). Disruption of PAK-Arp2/3 function leads to defective synaptic plasticity and learning deficits in association with intellectual disability (8, 18, 29, 36, 53). Other studies show that PAK3 gene mutations, that disrupt kinase activation or function, cause X-linked intellectual disability (62). Reduced regional PAK levels are described for AD brains (40, 64), and decreased PAK expression in a triple transgenic AD mouse model has been associated with dendrite and spine defects (2).

While there is considerable evidence for disturbances in spine actin regulation in both AD and DS, the degree to which synaptic PAK-Arp2/3 signaling may be disrupted in these disorders is not known. Moreover, there have been no studies directly comparing these disorders for differences in underlying mechanisms of spine dysfunction. Therefore, the goal of the present work was to evaluate levels of PAK3 and Actin-related protein 2 (Arp2; as a marker of the Arp2/3 complex) at excitatory synapses in neocortex of adults with DS+AD and those with AD alone, using an analytical approach that allows for analyses of very large numbers of individual synapses (8, 48, 53, 54). The studies were also aimed at determining if disturbances in these synaptic proteins reflect AD pathology in general or if they differ between the two disorders. In light of recent evidence that spine loss and levels of AD-like pathology may be dissociable (38), we also tested if changes in the PAK3-Arp2 pathway correlate with hyperphosphorylated tau levels.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California at Irvine (UCI) as a non-human subjects study. All samples (de-identified and coded) from tissue banks were recoded in-house and processed for all analyses with experimenter blind to subject and group. Analyses focused on parietal cortex because this region is preserved, compared to other cortical fields, in DS patient samples (44), and AD pathology has been described for parietal fields with age (39).

Tissue samples.

Postmortem parietal cortex samples were from subjects ranging from 52 to 64 years old (Table 1) with 10 controls, 6 DS cases, and 5 AD cases. Tissue blocks included a well-defined sulcus with portions of gyri present on both sides; superficial cortical layers within sulci were well-preserved and devoid of damage incurred during dissection or freezing. DS and AD tissue was provided by UCI Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders through the UCI-Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Control tissue was provided by the NICHD Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, and by the NINDS/NIMH sponsored Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center at the VA West Los Angeles Healthcare Center, Los Angeles, CA; controls in the same age range as the AD and DS cases were not available from the UCI ADRC. Effort was made to match age and postmortem interval (PMI) as closely as possible, although the control group contained both short and longer PMIs to assess whether this variable had effects on our measures. Both sexes were included but numbers of female controls available were more limited. All DS and AD cases had comparable AD pathology; i.e., stage 6 tangles and stage C plaques, as determined by the UCI ADRC. To assess the degree to which the AD and DS subjects were functionally comparable, ratings from a modified version of the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (mBADLS), collected within the last 1–2 years of life, were calculated. The mBADLS does not include items that DS individuals may not have been able to perform early in life (e.g., managing finances), and is based on a 0–42 point scoring system with higher scores indicating greater functional dependency (12) (Table 1). Higher mBADLS scores have been shown to be associated with lower cognitive scores on the Severe Impairment Battery for AD and DS individuals (12). Median mBADLS scores for DS and AD groups were 34.5 and 36, respectively; two AD individuals had comparatively lower scores than the other AD and DS cases.

Table 1.

Subject information.

| Condition | ID# | Bank | Age | Sex | PMI (h) | AD pathology Tangles; Plaques | mBADLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 2006–38 | UCI | 56 | F | 3.9 | Stage 6; Stage C | 36 |

| AD | 2009–5 | UCI | 57 | F | 3.2 | Stage 6; Stage C | 39 |

| AD | 2010–25 | UCI | 57 | F | 3.2 | Stage 6; Stage C | 11 |

| AD | 2006–19 | UCI | 59 | M | 3.3 | Stage 6; Stage C | 14 |

| AD | 2006–36 | UCI | 61 | M | 5.6 | Stage 6; Stage C | 37 |

| DS | 2007–31 | UCI | 52 | F | 4.4 | Stage 6; Stage C | 21 |

| DS | 2005–7 | UCI | 54 | M | 4.5 | Stage 6; Stage C | 40 |

| DS | 2008–42 | UCI | 55 | M | 4.5 | Stage 6; Stage C | 42 |

| DS | 2008–8 | UCI | 57 | F | 5.3 | Stage 6; Stage C | 29 |

| DS | 2004–23 | UCI | 58 | M | 3.4 | Stage 6; Stage C | 42 |

| DS | 2010–31 | UCI | 62 | F | 2.4 | Stage 6; Stage C | 25 |

| Control | 1503 | U. Maryland | 53 | F | 5 | ||

| Control | 5117 | U. Maryland | 56 | M | 5 | ||

| Control | 4263 | U. Maryland | 61 | M | 6 | ||

| Control | 5326 | U. Maryland | 62 | M | 6 | ||

| Control | M3983M | U. Maryland | 52 | M | 2 | ||

| Control | Hsb3371 | VA WLAHC | 52 | M | 16 | ||

| Control | Hsb3529 | VA WLAHC | 58 | M | 9 | ||

| Control | Hsb3558 | VA WLAHC | 59 | F | 19.5 | ||

| Control | Hsb3589 | VA WLAHC | 53 | M | 15 | ||

| Control | Hsb3611 | VA WLAHC | 64 | M | 17.5 |

Age, sex, and postmortem interval (PMI) for all cases in the study. DS and AD cases had AD pathology with stage 6 tangles and stage C plaques. Modified Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (mBADLS) scores are shown (higher scores indicate greater functional dependency; 0–42 points scale). See Materials and Methods for details.

Immunofluorescence.

Fresh-frozen tissue was sectioned (20 μm) perpendicular to the cortical surface, slide-mounted, and methanol-fixed. The tissue was processed for dual immunofluorescence using antisera directed against PSD-95 to label excitatory synapse postsynaptic densities (PSDs) (21) in combination with antisera to either PAK3 or Arp2 as described (8, 48). Antibodies included the well-characterized mouse anti-PSD-95 (1:1000; Thermo Scientific, #MA1–045, clone 6G6–1C9) (8, 9, 48), rabbit anti-PAK3 (1:300; Upstate, #06–902) (8, 9, 48, 53); and rabbit anti-Arp2 (1:200; Santa Cruz, #sc-15389) (28); additional antibody controls included verification of specificity by immunoblot and elimination of staining when primary antibodies were omitted. Species-specific Alexafluor488 and Alexafluor594 conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000 each; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for visualization.

Fluorescence deconvolution tomography.

Image z-stacks of layer 1 parietal cortex were collected through a depth of 2 um with 0.2 um steps, using 1.4 NA 63X objective and either a Leica DM6000 epifluorescence microscope with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera (PAK3 analyses) or a Leica DM6000 with a sCMOS pco.edge digital camera (Arp2 analyses). The sample field size was normalized to 42,840 um3 for both sets, and numbers of immunolabeled synapses ranged from 25,000–30,000 per stack. Layer 1 was analyzed because placement of the sample field, relative to the cortical surface, could be reliably replicated and the layer has few perikarya, thus allowing for greater sampling of synapses. For each antisera combination, 6–8 image stacks were collected from three sections per brain.

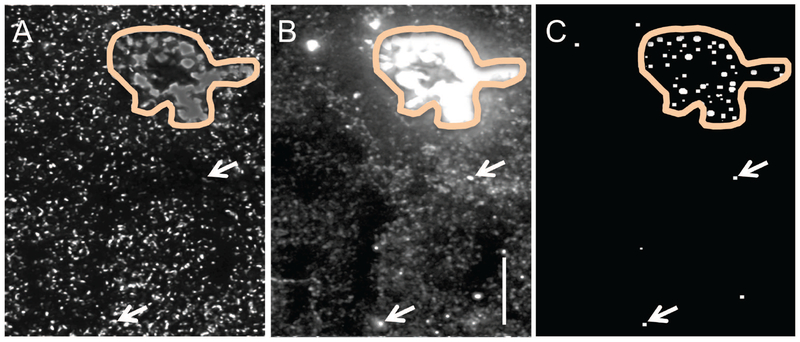

Image stacks were processed for iterative deconvolution using Volocity 4.1 (Perkin Elmer) or AutoQuant X2.1.3 (Media Cybernetics) for PAK3 and Arp2, respectively. Deconvolved images were analyzed to quantify both double- and single-labeled puncta within the size constraints of synapses as described (8, 9, 48, 53, 54). Background staining variations in the deconvolved images were normalized to 30% of maximum background intensity using a Gaussian filter. Object recognition and measurements of immunolabeled puncta were automated using software built in-house using Matlab R2007, Perl, and C which allows for analysis of objects reconstructed in 3D. Pixel values (8-bit) for each image were binarized using a fixed-interval intensity threshold series followed by erosion and dilation filtering to reliably detect edges of both faintly and densely labeled structures. Object area and eccentricity criteria were applied to eliminate from quantification elements that do not fit the size and shape range of synaptic structures. Puncta were considered colocalized if they touched or overlapped as assessed in 3D. Since lipofuscin granules are visible in both imaging channels, a final method was used to identify such granules that were counted in the first analyses. Briefly, a fluorescence intensity range for lipofuscin granules identified in the red channel was generated. From this range, the 110 intensity threshold was found to maximally identify lipofuscin granules (Fig. 1); notably, there were very few labeled objects identified at this threshold outside of densely autofluorescent lipofuscin-rich areas. Therefore, a cut-off intensity of ≥ 110 was applied to remove contributions of lipofuscin granules to the statistical analyses. This resulted in the removal of 1.0 ± 0.1, 1.8 ± 0.5, and 1.7 ± 0.3 percent of double-labeled profiles from control, DS, and AD groups, respectively.

Figure 1.

Identification of lipofuscin-positive granules in human tissue. Human parietal cortex processed for dual immunofluorescence localization of PSD-95 (green channel, A) and PAK3 (red channel, B) was examined for lipofuscin granules; example shown is from a control case. Outlined area indicates a region of autofluorescence containing dense fluorescent aggregates (A,B). Panel C shows elements evident in both channels that had a fluorescence intensity of ≥110; the majority of such objects were contained within lipofuscin-rich areas (outlined) although a few scattered lipofuscin granules (arrows) were distributed amongst the more numerous immunolabeled puncta. Bar, 10 um.

Object counts were averaged across z-stacks to produce mean values for each subject. Statistical comparisons used either a one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test for post-hoc paired comparisons, or the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s Multiple Comparison test (GraphPad Prism, Version 5.0); p<0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism (Version 5.0) was used for linear regression and intensity frequency curve (kurtosis and skewness) analyses. Because the main objective was to assess levels of PAK3 and Arp2 immunoreactivity associated with PSD-95, and because experiments were conducted separately, direct comparisons between the PAK3 and Arp2 levels were not possible.

Western blotting.

Sections from each tissue block were processed for blotting using Arp2 antisera (1:400; #sc-15389), PAK3 antisera (1:300; Abcam, #ab40808), phosphorylated (p) PAK Ser144/141/139 antisera (1:5000; Chemicon, #AB3833) that lies in the kinase inhibitory domain and plays a direct role in PAK activation (10), or AT8 antisera (1:750; Thermo Fisher, #MN1020; recognizes PHF tau epitopes S202 and T205) and ECL Plus Chemiluminescence (Amersham) (8). For PAK immunoblots, the blots were first probed for pPAK, then stripped using Restore Western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Fisher #21059) and probed for PAK3. For loading controls, blots were probed with mouse anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, #A5441) or anti-vinculin (ProSci, #PM7811). Blot densities were measured using ImageJ and normalized to loading controls for each sample. Significance was assessed by Student’s t-test (two groups) or either one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test or, for unequal variances, Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s Multiple Comparison Test (three groups), with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Synaptic PAK3 levels are reduced in DS and AD.

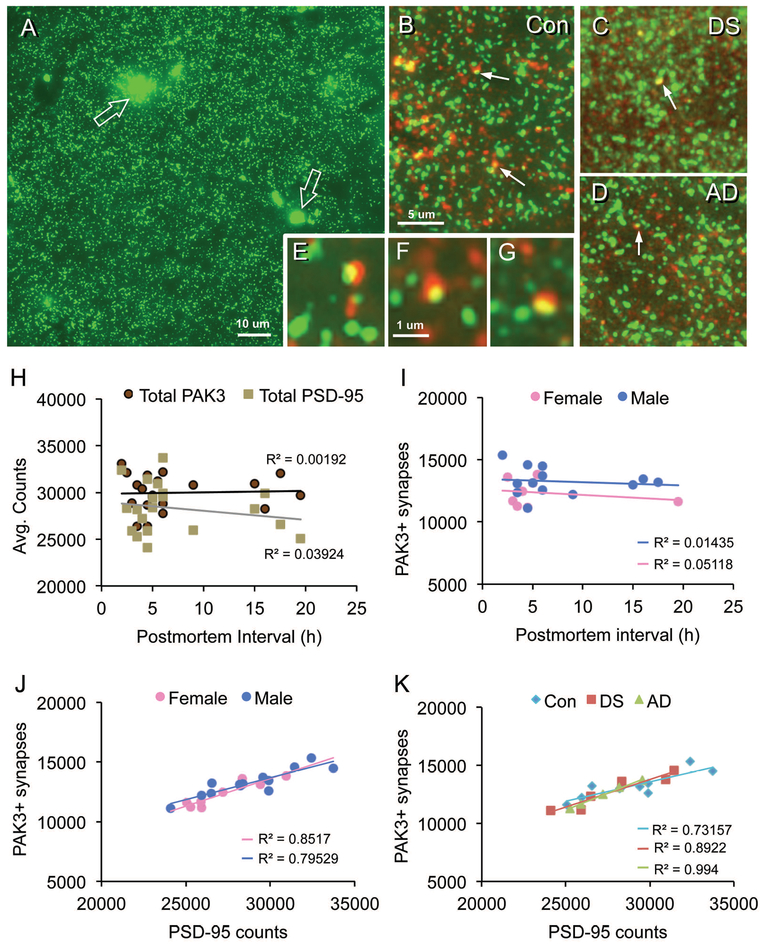

Quantitative immunofluorescence was used to assess PAK3 levels within the postsynaptic compartment of excitatory synapses in layer 1 parietal cortex (Fig. 2A–G) of middle-aged control subjects and individuals with DS and confirmed AD pathology or with AD alone. In all groups, antisera to the postsynaptic scaffold protein PSD-95 labeled round and crescent-shaped, synapse-sized elements that were broadly distributed across the neuropil (Fig 2A–D); a minority of these were double-labeled with antisera to PAK3 (Fig. 2B–G). In addition, there were larger patches of autofluorescence that were excluded from quantification (Fig. 2A; see Methods). Total counts of synapse-sized PAK3 immunopositive (+) and PSD-95+ elements (Fig. 1H), and of PAK3+ elements double-labeled for PSD-95 (Fig. 2I) were relatively unaffected by PMI; all correlational analyses were not significant. Moreover, numbers of PAK3+ synapses (double immunolabeled for PSD-95) were significantly correlated with the total numbers of PSD-95+ elements in samples from both females (p = 0.0011) and males (p< 0.0001) (Fig. 2J). Similarly high R2 values were obtained when the data were broken out by experimental group (p=0.0016 for controls, p=0.0045 for DS, and p=0.0002 for AD) (Fig. 2K). Importantly, total numbers of PSD-95+ puncta were comparable across groups indicating no significant differences in excitatory synapse densities in this lamina: average counts were 28,948 ± 2,741 (s.d.) for controls, 27,868 ± 2,905 for DS, and 27,223 ± 1,730 for AD (p = 0.4589, one-way ANOVA) for each 42,840 um3 sample field. The percentage of PSD-95+ elements colocalized with PAK3 immunoreactivity (ir) also did not differ among the three groups (p = 0.8564, Kruskal-Wallis).

Figure 2.

Synaptic localization of PAK3 immunoreactivity (ir) in human parietal cortex. Sections through layer 1 parietal cortex were processed for dual PSD-95 (green) and PAK3 (red) immunofluorescence. (A) Image shows typical PSD-95 immunolabeling in a control case: There is a relatively even distribution of small PSD-95 immunopositive (+) elements and fewer irregularly shaped auto-fluorescent deposits (open arrows). The latter were excluded from quantitative analyses based on size and intensity criteria. (B-G) Images show PAK3-ir (red) and PSD-9-ir (green) in control (Con) (B), Down syndrome (DS) (C), and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) (D) cases; arrows indicate double-labeled PSDs (seen as yellow) (bar, 5 um for B-D). (E-G) Higher magnification images of PSD-95 and PAK3 immunolabeled puncta and their colocalization (yellow) in control (E,F) and DS (G) cases (bar, 10 um for e-g). (H-K) Graphs show correlational analyses for numbers of PAK3+ synapses relative to postmortem interval (PMI) and sex; all cases are presented. (H) Scatter plots show average element counts per image field (42,840 um3) for total PAK3+ and total PSD-95+ puncta versus postmortem interval. Note the low R2 values; correlations were not significant for either protein (p = 0.8543 for PAK3; p = 0.4025 for PSD-95). (I) Plots of PAK3+ synapses by sex; the low R2 values were not significant (p = 0.5602 for males; p= 0.5901 for females). (J) Plots show similarly significant positive correlations between numbers of PAK3+ and PSD-95+ synapses for males (p < 0.0001) and females (p = 0.0011). (K) Re-plot of data presented in panel J with all cases identified by their disease group (sexes pooled). All three groups exhibit similar positive correlations between numbers of PAK3+ and PSD-95+ synapses (p = 0.0045 for DS, p = 0.0002 for AD, and p= 0.0016 for Con).

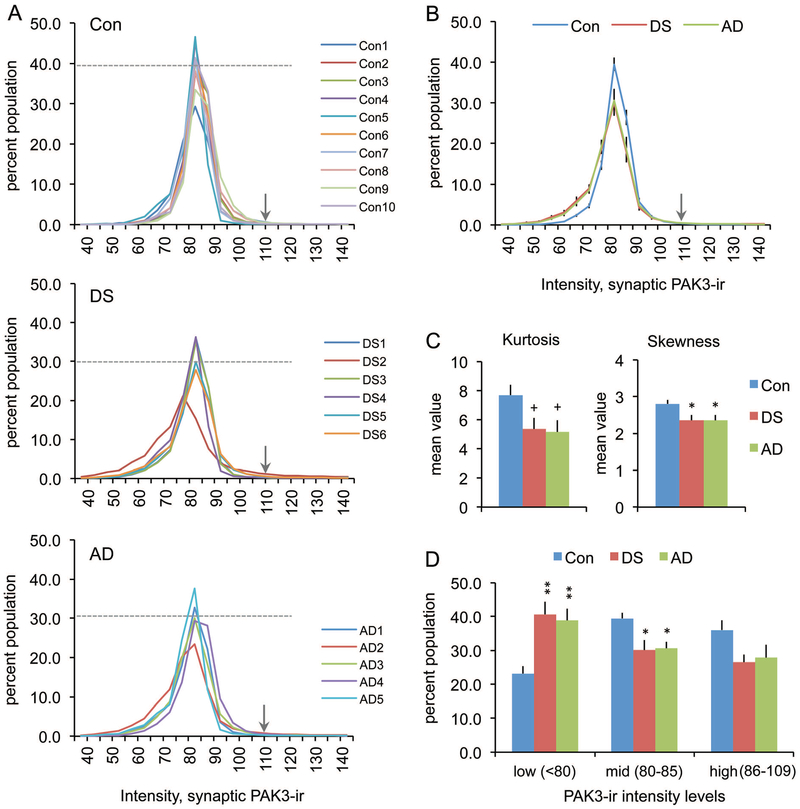

To determine if there was an effect of DS or AD on synaptic PAK3 content, the immunofluorescence intensity frequency distribution (IFD) for synaptic PAK3-ir was evaluated for all cases (Fig. 3A). As compared to controls, the IFD was broader for both DS and AD groups indicating a greater spread in the distribution of labeling intensities. The mean curves for each group show that the control distribution exhibits less variability and a more pronounced peak in the mid intensity range, whereas mean distributions for the DS and AD groups are virtually identical with greater spread into lower PAK3-ir intensities (Fig. 3B). Curve analyses identified significant differences in skewness (p = 0.02, one-way ANOVA; p < 0.05 for control vs DS and AD groups), and a trend toward an effect on kurtosis for DS and AD groups versus controls (p = 0.0538 and p = 0.0509 for DS and AD groups, respectively); the combined kurtosis values for DS and AD groups differed from controls (p = 0.0498 one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 3C). Overall, these results indicate that at excitatory synapses, postsynaptic PAK3 levels are reduced in both DS and AD parietal cortex, as compared to control.

Figure 3.

Synaptic PAK3 levels are reduced in DS and AD parietal cortex. (A) Synaptic immunolabeling intensity frequency distributions show the proportion of PSDs (Y-axis) that were immunolabeled for PAK3 at different intensities (X-axis) for the three groups. All cases in control (Con), DS, and AD groups are shown individually. Dashed line in each plot indicates the mean percent of that group for which PAK3-ir was at the 82.5 intensity level; arrows indicate the intensity threshold (110) that was used for cutoff in statistical analyses in panels C and D. (B) Intensity frequency distributions for group mean values (± SEM). For DS and AD groups there is a greater leftward skew in the distributions (towards lower intensities) and a lower proportion of synapses at the peak value relative to controls. (C) Bar graphs show the group mean kurtosis and skewness values (± SEM) for distributions presented in “A”. (Left: +p = 0.0538 for con vs DS, +p = 0.0509 for con vs AD, p = 0.0498 one-way ANOVA. Right: *p < 0.05 vs Con, p = 0.0202 one-way ANOVA). (D) Bar graph shows that for DS and AD groups there are greater numbers of synapses with low density (<80) PAK3-ir relative to the control group (Group means for low, mid, and high PAK3-ir intensity levels shown; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs Con).

As a second measure of synaptic PAK3 levels, we evaluated the volume of PAK3-ir elements colocalized with PSD-95. The cumulative labeling volume distributions for synaptic PAK3-ir were shifted to the left (i.e., toward lower volumes) for DS and AD groups relative to controls (Fig 4A). Mean volumes of PAK3-ir associated with PSD-95 were also significantly lower in DS and AD groups (p = 0.0066, one-way ANOVA; p < 0.01 for control vs both DS and AD groups), although this measure did not differ between DS and AD (p = 0.3063) (Fig. 4B). In contrast, PSD-95+ puncta volumes were comparable across groups (Fig. 4C&D) for both single- and double-labeled elements (p = 0.782 for double-labeled, p = 0.781 for single-labeled, one-way ANOVA), with volumes of double-labeled PSDs being larger than single-labeled PSDs in all groups. Thus, both intensity and volume measures demonstrate reduced PAK3 content in the postsynaptic compartment of excitatory synapses for middle-aged individuals with DS and AD relative to control subjects.

Figure 4.

Volumes of synaptic PAK3-ir are smaller in DS and AD parietal cortex compared to controls. (A,C) Cumulative frequency distributions show volumes of synaptic PAK3 and PSD-95 immunoreactivities for all three groups; PSD-95 data is from the double-labeled (PAK3+) puncta. Dashed line in each plot indicates the relative size accounted for by 80% of the population for each protein. (B) Bar graph shows group mean volumes of synaptic PAK3-ir: The DS and AD groups exhibited smaller synaptic PAK3-ir puncta, consistent with the small shift in the cumulative frequency curves for these two groups shown in ‘A’ (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs Con). (D) Bar graph shows no group differences in the volumes of PSD-95-ir puncta that were double- (+PAK3) or single-labeled.

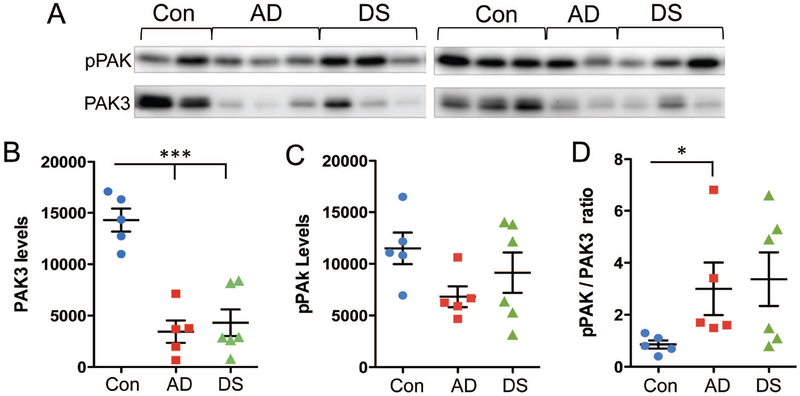

Finally, total levels of PAK3 and phosphorylated (p) PAK content in tissue sections from the same blocks used for immunofluorescence were evaluated by Western blotting. Because phosphorylation is affected by PMI (41), these analyses utilized the control cases with shorter intervals of 2–6h that best matched the AD and DS cases (Table 1). Total PAK3 levels were markedly reduced in the AD and DS groups (p < 0.0001 one-way ANOVA; p < 0.001 for control vs both DS and AD groups) (Figs. 5A,B), whereas pPAK levels were unaffected (p = 0.1365, Kruskal-Wallis test) (Fig. 5A,C). However, in comparing the ratio of pPAK to PAK3 levels in each sample this measure was significantly higher in the AD group relative to controls (p = 0.0245 Kruskal-Wallis; p < 0.05 AD vs control) (Fig. 5D). Although the pPAK to PAK3 ratio was high in some DS cases there was no group effect versus the controls. These results demonstrate that in conditions where PAK3 content is reduced, levels of PAK phosphorylation may also perturbed.

Figure 5.

Measures of total PAK3 and phosphorylated (p) PAK content in AD and DS parietal cortex. (A) Top row: Western blots showing pPAK levels in control (Con, n = 5), AD (n = 5), and DS (n = 6) cases with PMI of 6h or less. Bottom row: same blots that were stripped and then re-probed for PAK3 levels. (B, C) Quantification of immunoblots (Y-axis: arbitrary units). As shown, total PAK3 levels were markedly reduced in the AD and DS groups (p < 0.0001 one-way ANOVA; ***p < 0.001 for both DS and AD groups vs controls) (B), whereas pPAK levels were not significantly different across the three groups (p = 0.1365, Kruskal-Wallis test) (C). (D) Ratios of pPAK to PAK3 levels in each sample. Only the AD group had significantly elevated pPAK/PAK3 ratios versus controls (p < 0.05; p = 0.0245 Kruskal-Wallis).

Differential loss in synaptic Arp2 levels between DS and AD.

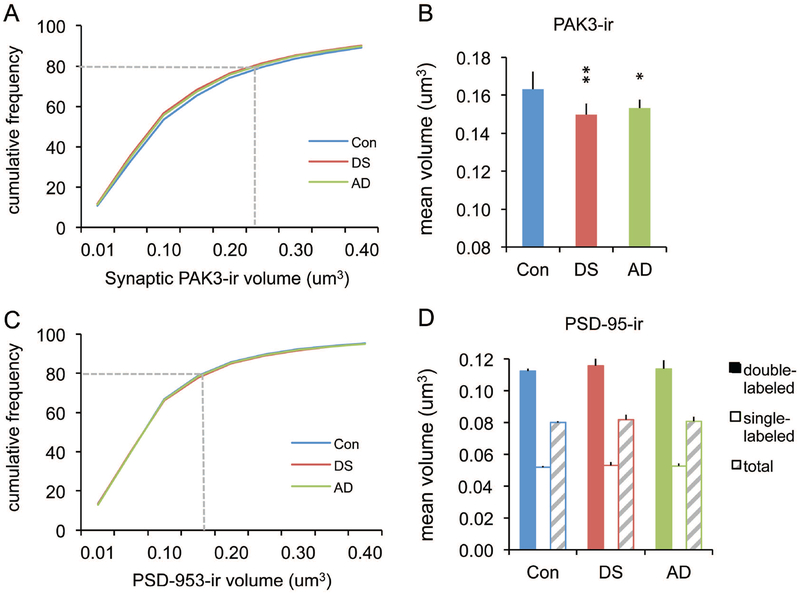

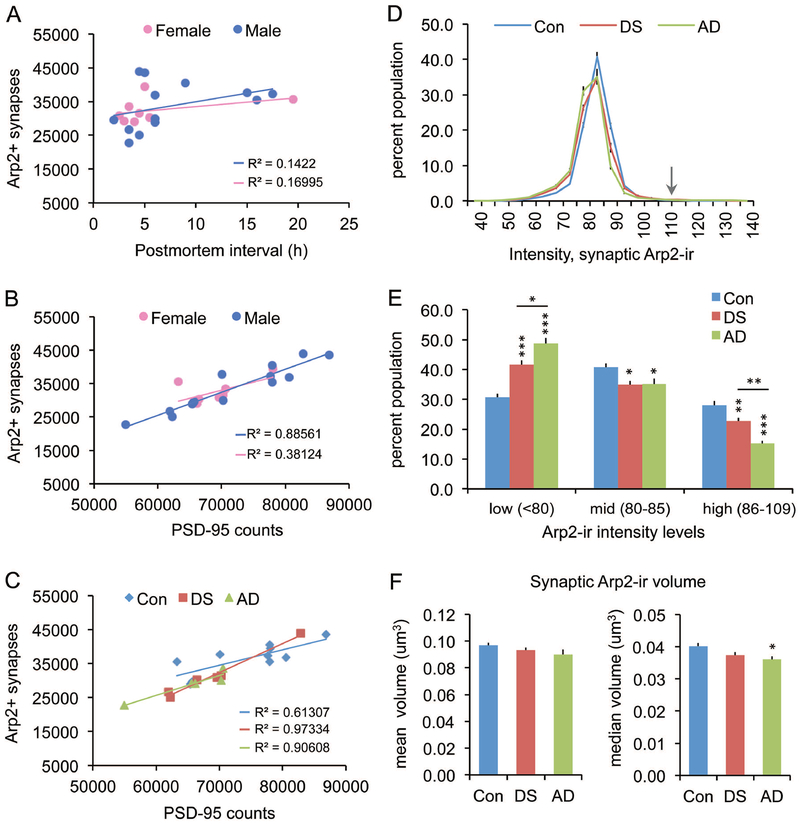

The Arp2/3 complex is a downstream target of PAK. To assess whether there are defects at multiple nodes in this signaling stream we analyzed levels of Arp2-ir colocalized with PSD-95. Numbers of Arp2+ synapses were unaffected by PMI (p=0.2040 and p=0.3201 for males and females, respectively) and were similar between the sexes (Fig. 6A). Numbers of Arp2+ synapses were positively correlated with total numbers of PSD-95+ elements for both sexes, although this only reached significance for males (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6B); combining both sexes, there was still a highly significant positive correlation (P < 0.0001; R2 = 0.8090). For the females, one outlier control case had a marked effect on the group, and when removed there was a significant positive correlation (p = 0.002; R2 = 0.9467). When these data were considered separately by condition, all three groups had significant positive correlations with the highest R2 values observed for DS (p = 0.0003) and AD (p = 0.0126) versus controls (p = 0.0074) (Fig. 6C). Normalizing the counts of double-labeled synapses to the total number of PSD-95+ elements (per sample) revealed that the proportion of PSDs containing Arp2 was 49 ± 1% (SEM) for controls, 45 ± 2% for DS, and 44 ± 1% for AD, with the AD group being significantly lower than controls (p = 0.0437 one-way ANOVA; p = 0.0214 for AD vs Con).

Figure 6.

Abnormalities in synaptic Arp2 levels are greater in AD than DS parietal cortex. (A-C) Numbers of Arp2+ synapses are unaffected by postmortem interval (PMI) or sex; all cases are presented in each panel. (A) Scatter plots show average counts per image field (42,840 um3) of Arp2+ synapses versus PMI for males and females; R2 values are low for each (p = 0.204 for males; p = 0.3201 for females). (B) Plots show positive correlations for numbers of Arp2+ synapses with total counts of PSD-95+ puncta in both sexes, although the correlation was significant for males (p < 0.0001) but not the females (p = 0.1029); notably, one female (control case, indicated by an asterisk) was an outlier, and it’s removal resulted in a significant correlation for the group (p = 0.002; R2 = 0.9467). (C) Plots show the same results presented in panel b but with all cases identified by group. All three groups had significant positive correlations between the two measures (p = 0.0003 for DS, p = 0.0126 for AD, p = 0.0074 for Con). (D) Plots show synaptic Arp2 immunolabeling intensity frequency distributions (expressed as a percent of total Arp2+ synapses) for control (Con), DS, and AD groups (group means ± SEM). Arrow indicates the 110 intensity threshold cutoff for statistical analyses. (E) Bar graph shows for each group the proportion of double-labeled synapses for which levels of Arp2-ir are in the low, middle (mid) and high intensity ranges (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs controls). The AD group exhibited a greater proportion of low vs high synaptic Arp2-ir compared to the DS group (*p<0.05, **p<0.01 for AD vs DS). (F) Bar graphs showing group mean (left) and median (right) ± SEM volumes for synaptic Arp2-ir; the median synaptic volume was significantly lower than Con for the AD group only (*p < 0.05).

In examining the intensity Arp2 immunolabeling colocalized with PSD-95, the IFDs for Arp2-ir had lower peaks and were shifted toward lower values in both DS and AD groups relative to controls (Fig. 6D). In accord with this, the proportions of synapses with high- and mid-intensity Arp2-ir were lower, whereas the proportions in the low-intensity range were greater, for both DS and AD groups versus controls. While these results indicate lower than control postsynaptic Arp2 levels in both DS and AD, the effect was significantly greater in the AD group (p < 0.01 for high intensity, and p < 0.05 for low intensity measures, AD vs DS; Fig. 6E). Analyses of synaptic Arp2-ir volume also revealed a greater differential from controls for the AD group: although mean Apr2-ir puncta volumes were not different between groups, the median volume of synaptic Arp2-ir was significantly smaller in the AD group versus controls (p < 0.05, Fig 6F). Median DS and control group values were not different. These results indicate that individuals with AD have lower postsynaptic Arp2 levels than do persons with DS or controls.

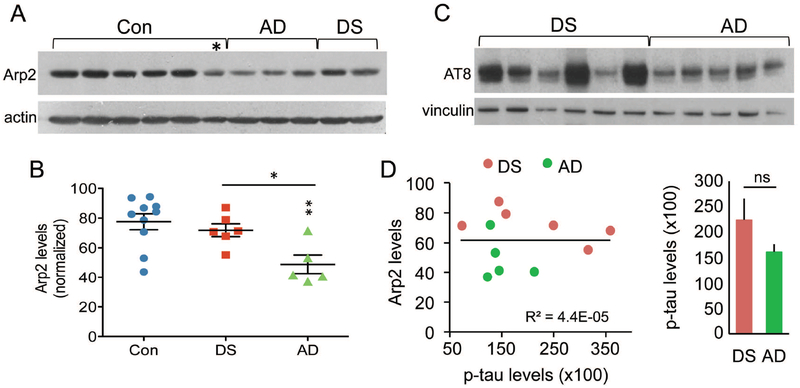

As the above finding suggests that there might be an overall reduction in Arp2 content in AD parietal cortex, total Arp2 levels were assessed using Western blots; tissue sections from the same blocks used for immunofluorescence were evaluated. The majority of control samples had high levels of Arp2-ir with two cases having ~40% less than the mean group value (p = 0.0079, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 7A,B). The DS group had similarly high levels of Arp2-ir (p = 0.4734 vs controls). In contrast, the AD samples had lower levels of Arp2-ir (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 for AD vs control and DS groups, respectively). To test if differences in Arp2-ir between DS and AD cases might reflect differences in AD pathology, levels of phosphorylated tau (p-Tau) in the same samples were evaluated using AT8 antisera (Fig. 7C,D). Levels of p-Tau were highly variable in the DS group with 3 of 6 cases having higher levels than any of the AD samples; among AD cases, only one had somewhat higher levels than the rest. Correlational analyses for measures of total Arp2 and p-Tau levels for all samples did not yield a significant effect (R2 = 4.4E-05; p = 0.9845). Similar analyses for DS (R2 = 0.37369; p = 0.1973) and AD (R2 = 0.12163; p = 0.5651) groups also did not show any correlation between Tau pathology and Arp2 content. Finally, there was no correlation between mBADLS scores and total Arp2 (R2 = 0.1136; p = 0.3108) or p-Tau (R2 = 0.06633; p = 0.4445) levels for the DS and AD groups combined.

Figure 7.

Total levels of Arp2-ir in parietal cortex are lower than normal in AD but not DS. (A) Representative Western blot shows bands of Arp2-ir, and actin-ir from same blot, for 6 control (Con), 3 AD, and 2 DS cases; asterisk indicates one control case that had low Arp2 levels. (B) Scatter plots show levels of Arp2-ir for all cases in each group (normalized to actin for each sample); lines show group mean ± SEM values. The AD group had significantly lower total Arp2-ir levels than did Con (**p < 0.01) or DS (*p < 0.05) groups. (C) Western blot shows AT8-ir and vinculin-ir from same blot for DS and AD cases. (D) Left, plot shows relationship of Arp2-ir to phosphorylated tau-ir levels (using AT8 anti-sera) in the same sample field of parietal cortex for all DS and AD cases; these measures were not significantly correlated (p = 0.9845, Student’s t-test). Right, bar graph shows p-tau measures (mean ± SEM values) for DS and AD groups (ns, not significant).

Discussion

Both DS and AD are associated with progressive dendritic spine loss in cortical and limbic regions (3, 14, 24, 31, 37). As greater than 90% of cortical excitatory synapses are on spines (23), this suggests that in both conditions there is a loss of excitatory synapses (see (51)). However, the present findings indicate that numbers of PSD-95+ synapses in parietal cortex layer 1 are at control levels in middle-aged individuals with DS plus AD pathology or with AD alone. This suggests that this cortical field may be spared from spine loss in the two disorders at least into middle age. It is also possible that spines are affected but this is compensated for by a shift from axospinous to axodendritic synapses that would not influence total PSD numbers. Consistent with this possibility, synapse density in the precuneus region of parietal cortex is reportedly unaffected in AD despite robust Aß load (52), even though spinophilin-positive spine synapses are reduced in AD in a manner that correlates with cognitive decline (37). Nevertheless, despite seemingly normal synapse numbers, we observed clear reductions in postsynaptic PAK3 and Arp2 levels in both disorders with decreases in synaptic and total Arp2 levels being greatest in the AD group. The basis for the difference in Arp2 levels between disorders was not clear. Arp2 levels did not correlate with those for p-Tau, which is elevated with AD pathology and correlates positively with dementia (17, 22). Moreover, the majority of DS cases exhibited much greater levels of p-Tau than those in the AD group; elevated levels of p-Tau in the DS group likely reflect overexpression of other DS related genes such as Dyrk1a which has been shown to directly phosphorylate Tau, including at one site that is recognized by the AT8 antibody used here (7, 49). It appears then that other factors are at play that differentially affects Arp2 protein levels between the DS and AD groups.

Prior studies had shown that regional PAK content is affected by AD, but levels at spine synapses were not known. In particular, cytosol levels of PAK1 and PAK3 isoforms, and phosphorylated PAK, are reportedly reduced in hippocampus and temporal cortex with moderate AD (64). Others found that in hippocampus reductions in phosphorylated PAK in perikarya correlate with the severity of AD pathology, and that total PAK levels are decreased in severe AD (40). Our findings of reduced total PAK3 levels in parietal cortex in AD, as well as in DS, cases with advanced pathology is consistent with this prior work. Notably, though, for the individual AD cases there was a marked elevation in the ratio of PAK phosphorylated at serine 144/141/139 within the kinase inhibitory domain relative to total PAK3 levels, further indicating that both levels and activation are altered in this disorder (32). Since phosphorylation at the site examined blocks the inhibitory domain resulting in catalytic activity of the kinase, the elevated pPAK/PAK ratio in AD suggests that the kinase may be constitutively active in this disorder. An alternative view is that there may be homeostatic mechanisms in place (e.g., altered phosphatase activity, different PAK pools) that maintain and in a sense protect pPAK levels despite the reduced total protein content. Importantly, the present work also goes beyond prior studies to show that within the postsynaptic compartment (i) PAK levels are reduced with severe AD, (ii) PAK disturbances are similar between DS individuals with AD pathology and those with AD alone, and (iii) changes in PAK levels are present outside of hippocampus and temporal cortex. It should also be noted that the loss of synaptic PAK was not all or none: Compared to controls, a generalized reduction in levels of synaptic PAK was evident in both immunolabeling intensity and volume measures. Whether reductions in synaptic PAK3 content are associated with enhanced kinase activation, as suggested by the blot findings, or with an aberrant redistribution (32) in spine is not known. However, insofar as PAK has been implicated in dendritic spine formation (27, 63) it is plausible that the observed deficits at synapses contribute to the apparent shift away from spine synapses in the parietal cortex in AD.

For DS, there is a potential link between PAK regulation and the trisomy 21 defect that underlies this disorder. The DS cell adhesion molecule (DSCAM) gene is located in the DS critical region, and DSCAM protein plays a role in dendritic arborization and spine formation (35). DS individuals tend to exhibit elevated DSCAM levels, particularly in cortical neurons (50). Interestingly, DSCAM overexpression in an immortalized cell line from a DS mouse model resulted in aberrant netrin 1-induced PAK1 phosphorylation but levels of PAK1–3 isoforms were unaffected (43). This suggests that elevated DSCAM levels in DS could influence PAK activity without an effect on PAK protein content. These observations further suggest that the decrease in postsynaptic PAK content in human DS brains observed here results from some aspect of AD pathology rather than from trisomy alone. Future studies are needed to determine if decreases in synaptic PAK content mirror the progression of AD pathology or if the loss only becomes evident in advanced cases, and if there is aberrant PAK phosphorylation in DS.

Arp2 phosphorylation is necessary for Arp2/3 complex activation (30). Thus, one might expect that reductions in Arp2 levels would have profound effects on Arp2/3 activity and the dynamic properties of F-actin networks. Little is known regarding the consequences of Arp2/3 complex deficits, although loss of the ArpC3 (p21) subunit in excitatory neurons during the postnatal period reduces spine F-actin remodeling, decreases spine head size and density, and increases axodendritic synapses (25, 26). These effects suggest that although spines are lost with an Arp2/3 complex defect, numbers of synapses may be preserved. This is consistent with the present results in which numbers of PSD-95+ synapses were unaffected in DS although spine loss is reportedly a general feature of the disorder (24, 31). Importantly, ArpC3 knockout mice exhibit working and episodic memory deficits (25), suggesting that reductions in Arp2/3 complex proteins have major behavioral consequences. We propose that decreases in postsynaptic Arp2 would blunt Arp2/3 complex activation and thereby contribute to cognitive deficits in both DS and AD; this effect is predicted to be greater in AD given the larger Arp2 reductions. It is noteworthy that Arp2/3 complex levels are reportedly reduced in DS cerebral cortex at mid-gestation (60), well before spinogenesis. Whether synaptic Arp2/3 complex levels are also altered in DS postnatally when synaptogenesis is high, and if this contributes to early dendritic abnormalities (34), remains to be determined. Finally, catalytically active PAK has been shown to increase ArpC1 (p41) phosphorylation which, in turn, promotes Arp2/3 complex assembly and its subcellular colocalization with actin (58). Although elevated pPAK/Pak ratios, as described here for AD, would be expected to enhance ArpC1 activity and complex assembly, constitutively active PAK could also interfere with mechanisms that regulate Arp2/3 complex disassembly resulting in abnormal complex localization and actin nucleation.

PAK and the Arp2/3 complex are important regulators of F-actin in dendritic spines (42), and are part of the Rac-Pak-cortactin cascade that promotes stabilization of long term potentiation (LTP) (48), and the associated spine head enlargement (9). Failed Rac-PAK signaling at excitatory synapses is linked to a higher threshold for inducing LTP (8, 29), and a protracted period over which newly induced LTP and activity-induced increases in spine F-actin are vulnerable to disruption (8). Thus, deficits in this pathway in DS and AD suggest that remodeling of the spine actin cytoskeleton, needed to sustain synaptic plasticity, may fail to properly stabilize in these disorders. Notably, DS is associated with a high proportion of spines that are short with large spine heads, so-called mushroom spines (33, 34). In contrast, in AD there are significantly fewer mushroom spines as compared to control brains that exhibit AD pathology (i.e. increased amyloid burden and neurofibrillary tangles) without cognitive decline (6). Thus, while DS and AD both show abnormally low spine densities, they differ in the incidence of mushroom-shaped spines. The relative reductions in synaptic PAK3 and Arp2 content in DS and AD could help explain the subtle differences in spine morphologies between these conditions. In particular, reduced PAK levels at DS and AD excitatory synapses could lead to exaggerated cofilin activity that would be predicted to shorten spine profiles, whereas lower Arp2 levels in AD as compared to DS synapses would be expected to more severely impair synaptic F-actin branching in AD. F-actin branching has been linked to spine head enlargement and, in particular, spine breadth (20). It is possible then that AD and DS diverge at this step in synaptic cytoskeletal regulation, with DS exhibiting mostly spine shortening, and AD manifesting both spine shortening and thinning of the spine head.

Our findings from comparisons of DS and AD brain specimens may provide new insights into the mechanisms of early synaptic dysfunction in these conditions. While few studies have evaluated postsynaptic proteins levels in both DS and AD, synaptic drebrin is reportedly reduced in cortex of middle-aged DS cases and in hippocampal and cortical regions of persons with AD (11, 16, 56, 64). Drebrin is critical for synapse formation and, like PAK and the Arp2/3 complex, regulates the stabilization of spine actin filaments (57). Importantly, PAK inhibition reduces neuronal drebrin content (64). These findings suggest that PAK is a critical upstream regulator of both the Arp2/3 complex and drebrin at spine synapses, and that PAK is essential for maintaining normal actin regulation. Thus, deficits in PAK would lead to failure of parallel actin-dependent mechanisms of spinogenesis in AD. How PAK regulates drebrin is not known, but evidence suggests it involves a common link with Cdk5: Cdk5/p35 modulates Rac activation of PAK (47), and Cdk5 phosphorylates drebrin to induce F-actin bundling (61). Both inactivation and hyperactivation of Cdk5 are neurotoxic, and heightened Cdk5 activation occurs in AD (55). These findings considered with the present results indicate that in adult DS and AD brains there are deficiencies in at least three synaptic proteins, PAK3, ARP2, and drebrin, that play major but unique (and potentially linked) roles in stabilizing the postsynaptic actin cytoskeleton. Such protein deficits, combined with aberrant Cdk5 activity as seen in AD, could represent early pathological events at synapses leading to the spine changes and associated cognitive disturbances that characterize these disorders. If PAK deficiency is in fact upstream of drebrin loss and decreased spine density in AD and DS, then new insights into the early stages of synaptic failure may be gained by determining the cause of synaptic PAK reduction.

Acknowledgments.

Supported by NICHD grant HD079823 to J.L., NIA grant P50 AG016573, and NICHD grant HD089491, with equipment support provided by the University of California Irvine Center for Autism Research and Treatment. C.C. was supported by NIA T32 grant AG00096–34. The authors thank Ms. Yue Q. Yao for superb technical contributions to these studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: the authors do not have any to report.

Data Availability. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Arendt T (2009) Synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol.118:167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arsenault D, Dal-Pan A, Tremblay C, Bennett DA, Guitton MJ, De Koninck Y, Tonegawa S, Calon F (2013) PAK inactivation impairs social recognition in 3xTg-AD Mice without increasing brain deposition of tau and Aβ. J Neurosci.33:10729–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baloyannis SJ (2009) Dendritic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurological Sci.283:153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamburg JR, Bernstein BW, Davis RC, Flynn KC, Goldsbury C, Jensen JR, Maloney MT, Marsden IT, Minamide LS, Pak CW, Shaw AE, Whiteman I, Wiggan O (2010) ADF/Cofilin-actin rods in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Alzheimer Res.7:241–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloom GS (2014) Amyloid-ß and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathology. JAMA Neurol.71:505–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boros BD, Greathouse KM, Gentry EG, Curtis KA, Birchall EL, Gearing M, Herskowitz JH (2017) Dendritic spines provide cognitive resilience against Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol.82:602–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cárdenas AM, Ardiles AO, Barraza N, Baéz-Matus X, Caviedes P (2012) Role of tau protein in neuronal damage in Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome. Arch Med Res.43:645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen LY, Rex CS, Babayan AH, Kramár EA, Lynch G, Gall CM, Lauterborn JC (2010) Physiological activation of synaptic Rac-PAK (p-21 activated kinase) signaling is defective in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci.30(33):10977–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LY, Rex CS, Casale MS, Gall CM, Lynch G (2007) Changes in synaptic morphology accompany actin signaling during LTP. J Neurosci.27:5363–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chong C, Tan L, Lim L, Manser E (2001) The Mechanism of PAK activation. J Cell Biol Chem.276:17347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Counts SE, He B, Nadeem M, Wuu J, Scheff SW, Mufson EJ (2012) Hippocampal drebrin loss in mild cognitive impairment. Neurodegener Dis.10(1–4):216–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick MB, Doran E, Phelan M, Lott IT (2016) Cognitive profiles on the severe impairment battery are similar in Alzheimer Disease and Down syndrome with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord.30:251–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN (1999) Activation of LIM-kinase by PAK1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signaling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat Cell Biol.1:253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiala JC, Spacek J, Harris KM (2002) Dendritic spine pathology: cause or consequence of neurological disorders? Brain Res Brain Res Rev.39:29–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grintsevich EE, Reisler E (2014) Drebrin inhibits cofilin-induced severing of F-actin. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken).71:472–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harigaya Y, Shoji M, Shirao T, Hirai S (1996) Disappearance of actin-binding protein, drebrin, from hippocampal synapses in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res.43(1):87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haroutunian V, Davies P, Vianna C, Buxbaum JD, Purohit DP (2007) Tau protein abnormalities associated with the progression of Alzheimer disease type dementia. Neurobiol Aging.28:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi ML, Choi SY, Rao BS, Jung HY, Lee HK, Zhang D, Chattarji S, Kirkwood A, Tonegawa S (2004) Altered cortical synaptic morphology and impaired memory consolidation in forebrain- specific dominant-negative PAK transgenic mice. Neuron.42:773–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Head E, Powell D, Gold BT, Schmitt FA (2012) Alzheimer’s disease in Down syndrome. Eur J Neurodegener Dis.1:353–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotulainen P, Hoogenraad CC (2010) Actin in dendritic spines: connecting dynamics to function. J Cell Biol.189:619–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt CA, Schenker LJ, Kennedy MB (1996) PSD-95 is associated with the postsynaptic density and not with the presynaptic membrane at forebrain synapses. J Neurosci.16:1380–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I (2010) Tau in Alzheimer Disease and Related Tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res.7:656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasthuri N, Hayworth KJ, Berger DR, Schalek RL, Conchello JA, Knowles-Barley S, Lee D, Vázquez-Reina A, Kaynig V, Jones TR, Roberts M, Morgan JL, Tapia JC, Seung HS, Roncal WG, Vogelstein JT, Burns R, Sussman DL, Priebe CE, Pfister H, Lichtman JW (2015) Saturated Reconstruction of a Volume of Neocortex. Cell.162:648–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufmann WE, Moser HW (2000) Dendritic anomalies in disorders associated with mental retardation. Cereb Cortex.10:981–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim IH, Racz B, Wang H, Burianek L, Weinberg R, Yasuda R, Wetsel WC, Soderling SH (2013) Disruption of Arp2/3 results in asymmetric structural plasticity of dendritic spines and progressive synaptic and behavioral abnormalities. J Neurosci.33(4):6081–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim IH, Rossi MA, Aryal DK, Racz B, Kim N, Uezu A, Wang F, Wetsel WC, Weinberg RJ, Yin H, Soderling SH (2015) Spine pruning drives antipsychotic-sensitive locomotion via circuit control of striatal dopamine. Nature Neuroscience.18:883–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreis P, Thevenot E, Rousseau V, Boda B, Muller D, Barnier JV (2007) The p21-activated kinase 3 implicated in mental retardation regulates spine morphogenesis through a Cdc42-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem.282(29):21497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauterborn JC, Kramár EA, Rice JD, Babayan AH, Cox CD, Karsten CA, Gall CM, Lynch G (2017) Cofillin activation is tmeporally assocaited with the cessation of growth in the developing hippocampus. Cereb Cortex.27:2640–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauterborn JC, Rex CS, Kramár EA, Chen LY, Pandyarajan V, Lynch G, Gall CM (2007) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci.27:10685–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeClaire LL, Baumgartner M, Iwasa JH, Mullins RD, Barber DL (2008) Phosphorylation of the Arp2/3 complex is necessary to nucleate actin filaments. J Cell Biol 182:647–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levenga J, Willemsen R (2012) Perturbation of dendritic protrusions in intellectual disability. Prog Brain Res.197:153–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma QL, Yang F, Calon F, Ubeda OJ, Hansen JE, Weisbart RH, Beech W, Frautschy SA, Cole GM (2008) p21-activated kinase-aberrant activation and translocation in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Biol Chem.283:14132–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marin-Padilla M (1972) Structural abnormalities of the cerebral cortex in human chromosomal aberrations: a Golgi study. Brain Res.44:625–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marin-Padilla M (1976) Pyramidal cell abnormalities in the motor cortex of a child with Down’s syndrome. A Golgi study. J Comp Neurol.167:63–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maynard KR, Stein E (2012) DSCAM contributes to dendrite arborization and spine formation in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci.32(47):16637–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng J, Meng Y, Hanna A, Janus C, Jia Z (2005) Abnormal long-lasting synaptic plasticity and cognition in mice lacking the mental retardation gene PAK3. J Neurosci.25:6641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mi Z, Abrahamson EE, Ryu AY, Fish KN, Sweet RA, Mufson EJ, Ikonomovic MD (2017) Loss of precuneus dendritic spines immunopositive for spinophilin is related to cognitive impairment in early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging.55:159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris GP, Clark IA, Vissel B (2014) Inconsistencies and controversies surrounidng the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun.2:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson LD, Siddarth P, Kepe V, Scheibel KE, Huang SC, Barrio JR, Small GW (2011) Positron emission tomography of brain β-amyloid and τ levels in adults with Down syndrome. Arch Neurol.68(6):768–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen TV, Galvan V, Huang W, Banwait S, Tang H, Zhang J, Bredesen DE (2008) Signal transduction in Alzheimer disease: p21-activated kinase signaling requires C-terminal cleavage of APP at Asp664. J Neurochem.104:1065–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oka T, Tagawa K, Ito H, Okazawa H (2011) Dynamic changes of phosphoproteome in postmortem mouse brains. Plos One.6(6):e21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penzes P, Rafalovich I (2013) Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in dendritic spines. Adv Exp Med Biol.970:81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pérez-Núñez R, Barraza N, Gonzalez-Jamett A, Cárdenas AM, Barnier JV, Caviedes P (2016) Overexpressed down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (DSCAM) deregulates p21-activated kinase (PAK) activity in an in vitro neuronal model of Down syndrome: consequences on cell process formation and extension. Neurotox Res.30(1):76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinter JD, Eliez S, Schmitt JE, Capone GT, Reiss AL (2001) Neuroanatomy of Down’s syndrome: a high-resolution MRI study. Am J Psychiatry.158:165901665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Probst A, Basler V, Bron B, Ulrich J (1983) Neuritic plaques in senile dementia of Alzheimer type: a Golgi analysis in the hippocampal region. Brain Res.268:249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rane CK, Minden A (2014) P21 activated kinases: structure, regulation, and functions. Small GTPases.5:e28003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rashid T, Banerjee M, Nikolic M (2001) Phosphorylation of Pak1 by the p35/Cdk5 kinase affects neuronal morphology. J Biol Chem.276:49043–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rex CS, Chen LY, Sharma A, Liu J, Babayan AH, Gall CM, Lynch G (2009) Different Rho GTPase-dependent signaling pathways initiate sequential steps in the consolidation of long-term potentiation. J Cell Biol.186:85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryoo SR, Jeong HK, Radnaabazar C, Yoo JJ, Cho HJ, Lee HW, Kim IS, Cheon YH, Ahn YS, Chung SH, Song WJ (2007) DYRK1A-mediated hyperphosphorylation of Tau. A functional link between Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem.282:34850–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saito Y, Oka A, Mizuguchi M, Motonaga K, Mori Y, Becker LE, Arima K, Miyauchi J, Takashima S (2000) The developmental and aging changes of Down’s syndrome cell adhesion molecule expression in normal and Down’s syndrome brains. Acta Neuropathol.100(6):654–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheff SW, Price DA (2003) Synaptic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of ultrastructural studies. Neurobiol Aging.24:1029–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, Roberts KN, Ikonomovic MD, Mufson EJ (2013) Synapse stability in the precuneus early in progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis.35:599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seese RR, Babayan AH, Katz AM, Cox CD, Lauterborn JC, Lynch G, Gall CM (2012) LTP induction translocates cortactin at distant synapses in wild-type but not Fmr1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci.32:7403–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seese RR, Chen LY, Cox CD, Schulz D, Babayan AH, Bunney WE, Henn FA, Gall CM, Lynch G (2013) Synaptic abnormalities in the infralimbic cortex of a model of congenital depression. J Neurosci.33(33):13441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah K, Rossie S (2018) Tale of the good and the bad Cdk5: remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton in the brain. Mol Neurobiol.55:3426–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shim KS, Lubec G (2002) Drebrin, a dendritic spine protein, is manifold decreased in brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett.324:209–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shirao T, Hanamura K, Koganezawa N, Ishizuka Y, Yamazaki H, Sekino Y (2017) The role of drebrin in neurons. J Neurochem.141:819–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vadlamudi R, Li F, Barnes C, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Kumar R (2004) p41-Arc subunit of human Arp2/3 complex is a p21-activated kinase-1-interacting substrate. EMBO Rep.5:154–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weaver AM, Karginov AV, Kinley AW, Weed SA, Li Y, Parsons JT, Cooper JA (2001) Cortactin promotes and stabilizes Arp2/3-induced actin filament network formation. Curr Biol.11:370–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weitzdoerfer R, Fountoulakis M, Lubec G (2002) Reduction of actin-related protein complex 2/3 in fetal Down syndrome brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.293(2):836–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Worth DC, Daly CN, Geraldo S, Oozeer F, Gordon-Weeks PR (2013) Drebrin contains a cryptic F-actin-bundling activity regulated by Cdk5 phosphorylation. J Cell Biol.202:793–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zamboni V, Jones R, Umbach A, Ammoni A, Passafaro M, Hirsch E, Merlo GR (2018) Rho GTPases in intellectual disability: from genetics to therapeutic opportunities. Int J Mol Sci.19:pii: E1821. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang H, Webb DJ, Asmussen H, Niu S, Horwitz AF (2005) A GIT1/PIX/Rac/PAK signaling module regulates spine morphogenesis and synapse formation through MLC. J Neurosci.25(13):3379–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao L, Ma QL, Calon F, Harris-White ME, Yang F, Lim GP, Morihara T, Ubeda OJ, Ambegaokar S, Hansen JE, Weisbart RH, Teter B, Frautschy SA, Cole GM (2006) Role of p21-activated kinase pathway defects in the cognitive deficits of Alzheimer disease. Nat Neurosci.9:234–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]