Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) accumulate in tumors and the peripheral blood of cancer patients and demonstrate cancer-promoting activity across multiple tumor types. A limited number of agents are known to impact MDSC activity. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 8 is expressed in myeloid cells. We investigated expression of TLR8 on MDSC and the effect of a TLR8 agonist, Motolimod, on MDSC survival and function. TLR8 was highly expressed in monocytic MDSC (mMDSC) but absent in granulocytic MDSC (gMDSC). Treatment of human PBMC with Motolimod reduced the levels of mMDSC in volunteers and cancer donors vs. control (p<0.001). Motolimod did not impact levels of gMDSC. The reduction of mMDSC was due to induced cell death by TLR8 ligation. Pre-treatment of PBMC with a FAS neutralizing antibody inhibited Motolimod induced reduction of mMDSC compared to control (p<0.001). Finally, we demonstrated that mMDSC impeded IL-2 secretion by CD3/CD28 activated T-cells, IL-2 secretion was partially restored when cells were co-cultured with Motolimod (142±36 pg/ml vs. 59±13 pg/ml; p=0.03). There is increasing evidence that MDSC contribute to the progression of cancer by inhibiting tumor-directed T-cells. TLR8 agonists may synergize with cancer immunotherapeutic approaches to enhance the anti-tumor effects of the adaptive immune response.

Keywords: TLR8, TLR8 agonist, MDSC, apoptosis, T cells, Cancers

Summary Sentence:

TLR8 is expressed in monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and TLR8 agonist Motolimod can reduce the levels of mMDSC and restore inhibited T cell function.

Introduction

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) demonstrate a variety of functions that both promote tumor growth as well as inhibit immune cell activity. Specific subtypes of MDSC, monocytic (mMDSC) and granulocytic MDSC (gMDSC), can prevent the egress of activated CD8 T-cells into the tumor [1], downregulate TCR-zeta chain thus limiting T-cell activation [2], and impede T-cell differentiation [3]. Elevated levels of MDSC portend a poor prognosis or predict disease progression in many types of cancers [4–6]. High levels of MDSC in the peripheral blood of cancer patients prior to therapy is associated with a lack of or incomplete response to treatment for several cancers [7, 8]. Elevated blood MDSC has also been shown to be associated with a lack of clinical response to immune therapy in cancer patients[9–11]. There are few agents known impair MDSC function or survival which could be used in the treatment of cancer.

MDSC modulate the adaptive immune response and can be activated via toll-like receptors including toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 [12–14]. Signaling through TLR4, for example, causes MDSC to secrete IL-10 and promote a Th2 immune phenotype[14]. TLR signaling in MDSC is an important pathway resulting in control of inflammatory processes [15].

Motolimod is a small molecule selective TLR8 agonist and has been shown to stimulate Type I cytokine production from antigen presenting cells resulting in T-cell activation [16]. We questioned whether TLR8 was expressed in MDSC and, if so, what effects TLR8 ligation would have on MDSC differentiation and function.

Materials and Methods

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

Frozen PBMC from volunteer donors were obtained from Astarte Biologics [17]. Patient PBMC (melanoma, prostate, and colon cancers treated to complete remission) were obtained under an IRB approved protocol [18]. Frozen PBMCs were thawed and washed before use [19].

Cell subset isolation.

PBMC were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Cell subtypes were isolated by BD FACS Aria II cell sorter. Myeloid (mDC; Lineage- HLA-DR+, CD11C+) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC; Lineage- HLA-DR+, CD11c-, CD123+) and monocytic myeloid-derived (mMDSC, HLA-DR- CD14+) and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (gMDSC, Lineage-HLA-DR- CD33+) were isolated. mMDSC, monocytes (HLA-DR+ CD14+) and CD3+ T-cells were also isolated.

TLR mRNA expression analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from FACS-sorted mDC, pDC, mMDSC, and gMDSC. mRNA expression of TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 was analysed and normalized to b-actin/HPRT [20].

Cell culture and treatment with TLR agonists.

PBMC (2×106/ml) were cultured with 167nM or 500nM Motolimod (VentiRx Pharmaceuticals) or PBS for 24 hours. In some assays, the cells were cultured with 0.5uM and 2uM of TLR7/8 agonist CL-075, 10uM and 50uM of TLR7 agonist Imiquimod, and 50nM and 100nM of TLR 9 agonist CpG ODN2006 with PBS control (all InvivoGen). Doses were optimized as previously reported [16].

Flow cytometry analysis.

Cells were stained with antibodies and analysed as percentage of mMDSC and gMDSC in PBMC. Cells were also stained with an Annexin V PE, 7-AAD apoptosis detection Kit (BD Biosciences). All Annexin V+ and 7-AAD+ positive cells were counted as dead. Cell surface death receptor Fas (CD95) was added and mean fluorescence (FL) of FAS expression compared between control and treated mMDSC. CD69+ and FAS-L+ cells % of CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ cells were compared between groups.

Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) and labelling of mMDSC.

HLA DR- CD14+ cells were enriched using microbeads (Miltenyl Biotec), and labelled with 3uM CFSE for 15 minutes at 370C using a Vybrant CFDA SE Cell Tracer Kit (Invitrogen) [21]. Labelled mMDSC were mixed with donor PBMC and cultured with PBS and 500nM Motolimod for 24 hours. Both HLA-DR- cells and HLA DR+CD14+ cells % of CFSE labelled cells were analyzed.

FAS blocking.

PBMC were cultured with 2 ug/ml of a Fas neutralizing antibody (clone ZB4, EMDMillipore) and isotype control for one hour. Cultured cells were incubated with or without 500nM Motolimod for 20 hours before analysis.

Cytokine analysis.

FACS-sorted CD3+ cells (2.5×106/ml) were stimulated with CD3/CD28 beads (Life technology, Carlsbad, CA) at a 5:1 ratio. FACS sorted mMDSC were added to the activated CD3 T-cells at 1:1 ratio +/− 750nM Motolimod. Both CD3+ T-cells and mMDSC alone and with Motolimod were used as control. FACS-sorted HLA-DR+CD14+ monocytes were also cultured +/− Motolimod for 20 hours and supernatants harvested. Quantification of secreted cytokines was performed using a cytokine human magnetic kit (Life Technologies) by Luminex (Qiagen) per manufacturer’s instructions and reported as mean of pg/ml of duplicated measurements [22].

Statistical analyses.

GraphPad Prism version 6 was used (GraphPad Software). Paired t-test compares the differences between control and treated cells. Differences in cytokine levels among groups were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test. p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

mMDSC, but not gMDSC, express TLR8 mRNA.

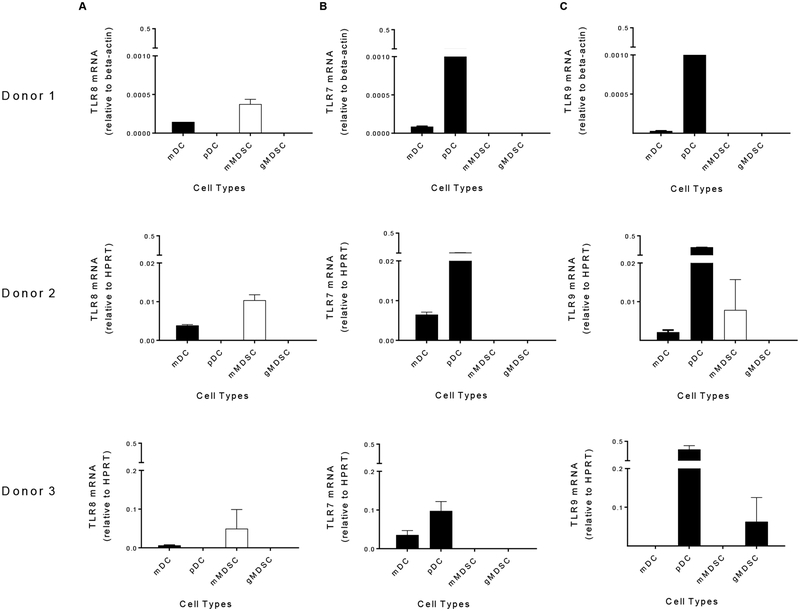

We have previously shown that TLR8 is expressed on monocytes and mDCs and the TLR8 agonist motolimod induces these cells to produce IL-12 and TNF-a [16]. We questioned whether TLR8 was expressed on MDSC; a heterogeneic population of cells that contain at least two subsets, monocytic and granulocytic, both of which have variable immunosuppressive effects [3]. We found that TLR8 was highly expressed on the mMDSC subpopulation (HLA-DR-CD14+) but absent on gMDSC [Lineage (Lin)-HLA-DR- CD33+] (Fig. 1A). Further, the levels of TLR8 expression were higher in mMDSC than in myeloid DC. mMDSC, as compared to gMDSC, are uniquely capable of inhibiting T-cells that have become activated. mMDSC prevent CD44 expression on activated T-cells and limit the movement of T-cells from the blood to tissues [23]. mMDSC also suppress expression of CD162 reducing T-cell adherence [23]. We evaluated the expression of TLR7 and TLR9 on MDSC in the same donors. We found that TLR7 mRNA was not expressed on either mMDSC or gMDSC (Fig. 1B). The expression of TLR9 on mMDSC and gMDSC was variable among donors (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. mMDSC, but not gMDSC, express higher levels of TLR8 mRNA.

mRNA expression of TLR8 (A), TLR7 (B) and TLR9 (C) on mDC, pDC, mMDSC and gMDSC in three donors. Columns and bars represents mean (± SE) of duplicate measurements. mMDSC, white column; other cell types, black columns.

Motolimod treatment reduces the levels of mMDSC in PBMC.

TLR8 is expressed on myeloid DC which are some of the most effective antigen presenting cells in the tumor microenvironment and capable of activing cancer specific T-cells [24]. TLR8 ligation stimulates myeloid DC to markedly upregulate co-stimulatory and MHC molecules, secrete Type I cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-12, and can even restore defective Type I cytokine secretion in the DC of patients with HIV [16, 25, 26]. In contrast to TLR8 effects on DC, we found in vitro treatment of PBMC with varying doses of Motolimod significantly decreased the number of mMDSC in a dose dependent manner. 167nM Motolimod reduced mMDSC to 42.9 ± 10.3 % (mean ± SE: n=15) of PBS treatment. When the cells were treated with 500nM Motolimod, the mMDSC fraction was further decreased to 23.1 ± 4.2 % (Table 1). The majority of mMDSC co-express CD33. The HLA-DR-CD14+CD33+ mMDSC in PBMC was also significantly decreased to 44.6 ± 14.8 % of control (mean ± SE, n=15) in cells treated with 167nM and 16.3 ± 3.7% in cells treated with 500nM Motolimod (Table 1). Neither dose of Motolimod affected Lin-HLA-DR- CD33+ gMDSC. The majority of gMDSC co-expressed CD11b. The Lin-HLA-DR-CD33+CD11b+ gMDSC was not impacted by the treatment (Table 1). Representative flow cytometric dot plots are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. We next questioned whether we would observe similar effects in the PBMC of cancer patients. PBMC derived from two patients with colon cancer, one with prostate cancer and one with melanoma were similarly treated. The mMDSC % in PBMC was decreased in all patients treated with Motolimod (Fig. 2A).

Table 1. Motolimod treatment reduces the levels of mMDSC in PBMC.

The numbers below show the percentage reduction of MDSC among PBMC as compared to PBS control.

| 167nM Motolimod mean ± SE (n=15) | 500nM Motolimod mean ± SE (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR-CD14+ mMDSC % among PBMC | 42.9 ± 10.3 | 23.1 ± 4.2 |

| HLA-DR-CD14+ CD33+mMDSC % among PBMC | 44.6 ± 14.8 | 16.3 ± 3.7 |

| Lin-HLA-DR-CD33+ gMDSC % among PBMC | 75.5 ± 27.0 | 57.6 ± 12.6 |

| Lin-HLA-DR-CD33+ CD11b+ gMDSC % among PBMC | 84.1 ± 29.3 | 57.0 ± 15.0 |

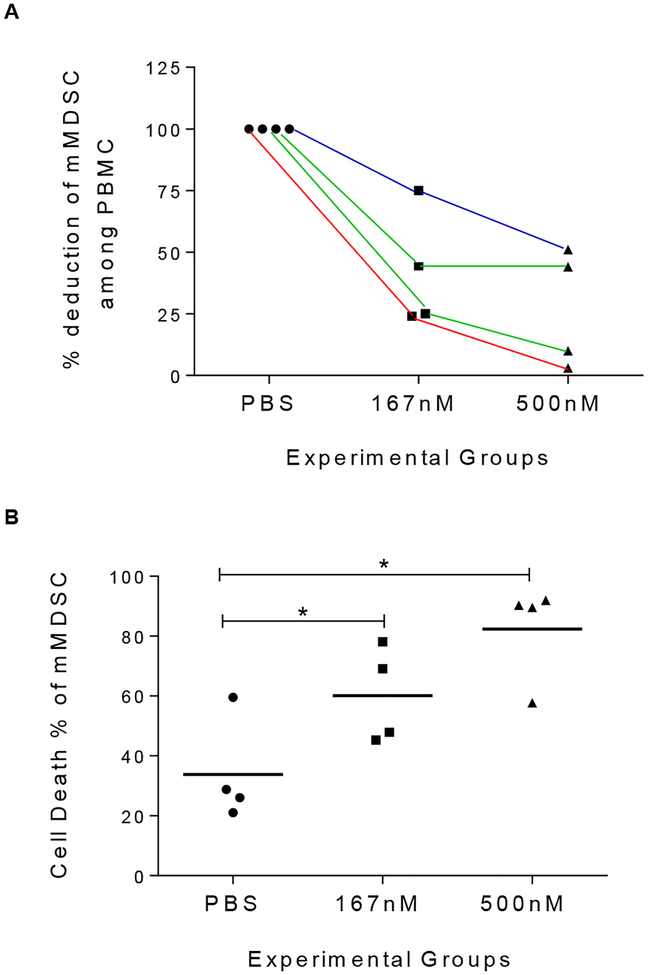

Figure 2. Motolimod treatment initiates apoptosis of mMDSC in cancer patients.

(A) % deduction of mMDSC among PBMC in patients treated with 167nM and 500nM Motolimod as compare to PBS control. Each line represents data form the same patient at varying doses. Red line: melanoma; green lines: colon cancer; blue line, prostate cancer (B) Cell death % of m-MDSC from above four patients. Lines are the means of each experimental group. * p<0.05.

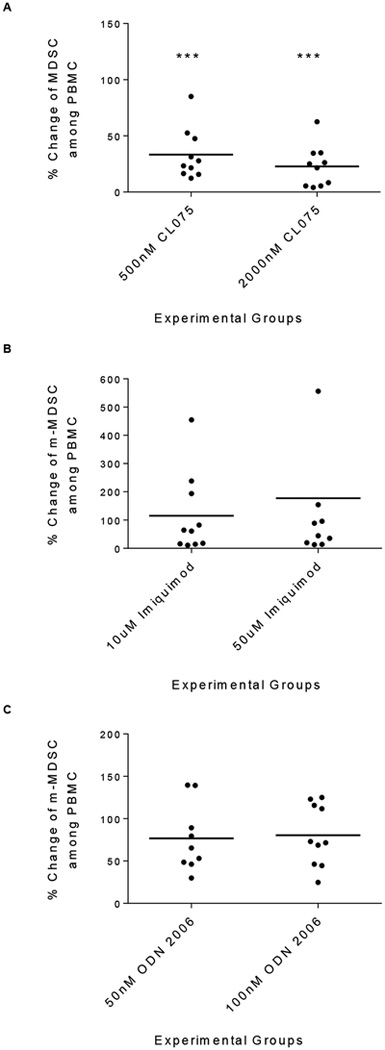

The reduction in mMDSC was specific for treatment with a TLR8 agonist.

We examined the effects of a TLR7/8 agonist CL075, a TLR7 agonist Imiquimod, and a TLR9 agonist ODN2006 on mMDSC. Similar to Motolimod, the HLA-DR-CD14+ mMDSC in PBMC was significantly decreased in cells treated with 0.5uM CL075 (mean ± SE: 33.4 ± 7.1% of PBS control p=0.000) and 2uM CL075 (22.8 ± 5.8%; p=0.000; n=10; Fig. 3A). However, both doses of Imiquimod (p>0.05, Fig. 3B) and ODN2006 (p>0.05, Fig. 3C) did not impact the level of the mMDSC population.

Figure 3. Reduction in mMDSC is specific for treatment with a TLR8 agonist.

Shown % change of mMDSC among PBMC in 0.5 uM and 2 uM CL075 (A), 10 uM and 500 uM Imiquimod (B) and 50 nM and 100 nM ODN 2006 (C) treated PBMC vs. PBS controls. Lines are the means of the experimental groups (n=10 volunteer donors). *** p<0.000.

Our results were unexpected as recent studies suggested incubation of mMDSC with a TLR7/TLR8 agonist could elicit significant IL-12 secretion and promote the differentiation of the cells into M1 macrophage over a 3 day period [27]. We did find that Motolimod treatment could promote limited Type I cytokine secretion in mMDSC (Supplemental Fig. 2A, 2B) but without any increase in HLA-DR+ cells (p>0.05) which would indicate a shift in phenotype (p>0.05; Supplemental Fig. 2C). These varying effects may be due to distinct functional differences between TLR8 and TLR7 agonists [28]. TLR8 is present only in myeloid DC while TLR7 agonists will activate both myeloid and plasmacytoid DC and B cells which may result in differential stimulation of T-cells. Moreover, studies demonstrate that Type I cytokine levels produced by monocytes stimulated with a specific TLR8 agonist are 100 times greater than levels induced by a TLR7 agonist [28]. Type I cytokine release mediated by Motolimod could lead to direct activation of both CD4 and CD8 T-cells resulting in upregulation of CD69 as well as FAS-L on the T-cell surface.

Motolimod induces apoptosis of mMDSC, in part, through FAS ligation.

Fas+ MDSC are susceptible to Fas-mediated killing by activated T-cells [29]. Investigations in mice have demonstrated that activated FasL+ T-cells induce apoptosis in Fas expressing MDSC [30, 31]. We questioned whether the reduction of mMDSC in human PBMC was secondary to the same phenomenon; induced cell death. The induction of cell death of mMDSC within PBMC was significantly increased in cells treated with 167nM Motolimod (mean ± SE of cell death % of mMDSC: PBS, 45 ± 7%; 167nM, 71 ± 9%; p=0.0111). When PBMC were treated with 500nM Motolimod, mMDSC death was further increased (84 ± 6%, vs. PBS, p=0.0001; vs. 167nM, p=0.0455; Fig. 4A). In contrast, cell death among total PBMC was no different from the control with both doses of Motolimod (p>0.05; Fig. 4B; representative staining Supplemental Figure 3A, 3B). Motolimod treatment induced similar levels of cell death of the mMDSC in cancer patients (Fig. 2B).

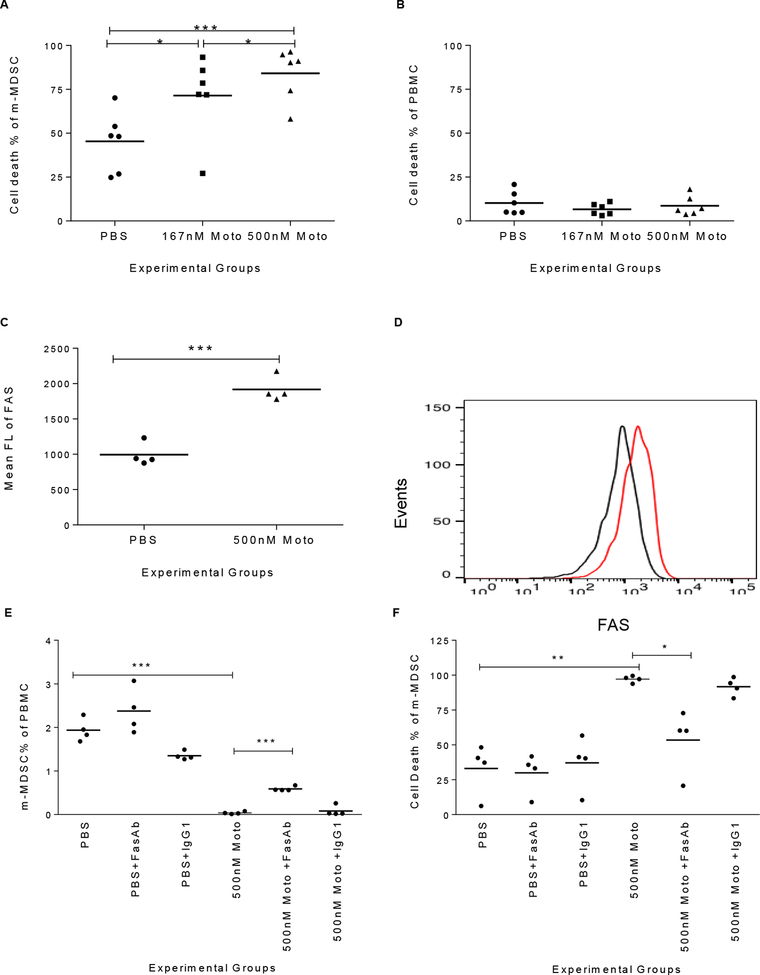

Figure 4. Motolimod induces apoptosis of mMDSC, in part through FAS ligation.

(A-B) Cell death % of mMDSC (A) and PBMC (B) following treatment with PBS or Motolimod in doses of 167 and 500nM (n=6 volunteer donors). (C-D) FAS expression in mMDSC population following treatment with PBS or 500nM Motolimod, (C) mean FL of FAS, n=4 volunteer donors, and (D) Representative overlay FLOW histograms of FAS expression (black, PBS; red, Motolimod). (E-F) mMDSC % of PBMC (E) and cell death % of mMDSC (F) in PBS alone, with FAS blocking Ab or IgG1 isotype control, and in 500nM Motolimod alone, with FAS blocking Ab or IgG1 isotype control. Lines are the means of the experimental groups. *p<0.05, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

We have previously shown that Motolimod does not directly activate T-cells [16]. Treatment with the agent, however, indirectly activated T-cells resulting in significant expression of CD69 on both CD4 (p=0.0148) and CD8 (p=0.0044) T-cells compared to cells treated with PBS (Supplemental Fig. 4A, 4B). Fas Ligand was also significantly upregulated on CD4 and CD8 T-cells with motolimod treatment (p=0.0056 and 0.0257 respectively as compared to PBS) (Supplemental Fig. 4C, 4D). Murine MDSC express the death receptor FAS and apoptose upon exposure to activated T-cells [30]. We measured the FAS (CD95) expression on human mMDSC after Motolimod treatment. The mean fluorescence (FL) of FAS on mMDSC was significantly elevated after the treatment (mean ± SE of mean FL: PBS, 994 ± 81%; Motolimod, 1917 ± 88, p=0.0003; Fig. 4C; representative histograms Fig. 4D). The mMDSC population among PBMC was not affected by FAS neutralizing antibody or isotype control alone as compared to the PBS control (p>0.05). The Motolimod dependent reduction of the mMDSC population could be inhibited by pre-treatment of the cells with FAS antibody (Fig. 4E) (mean ± SE of mMDSC % PBMC: Motolimod, 0.04 ± 0.01; with FAS antibody, 0.59 ± 0.03; p=0.0007) and not inhibited with the isotype control (p>0.05). Representative analyses are shown in Supplemental Figure 3C for the various culture conditions. Similarly, death of mMDSC induced by Motolimod was significantly reduced by FAS antibody (mean ± SE of cell death % of mMDSC: Motolimod: 94.1 ± 1.1%; with FAS antibody, 53.5 ± 10.1%, p=0.0354) but not by the isotype control (p>0.05, Fig. 4F).

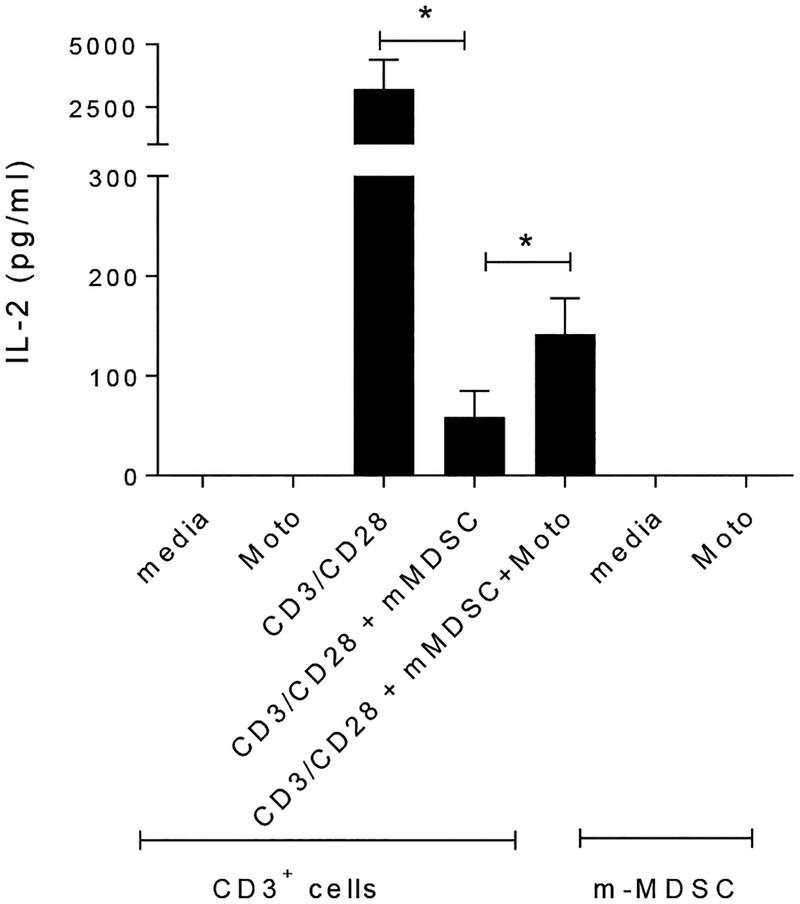

Motolimod dependent depletion of mMDSC partially restores T-cell activation.

As shown in Fig. 5, mMDSC significantly inhibited IL-2 secretion by CD3+ cells stimulated with CD3/CD28 antibody (mean ± SE of IL-2 (pg/ml): CD3/CD28 antibody alone, 3213 ± 1172 pg/ml; with mMDSC, 59 ± 13 pg/ml; p=0.029). IL-2 secretion was partially restored when the cells were co-cultured with Motolimod (142 ± 36; p=0.03). Motolimod incubation did not directly stimulate IL-2 secretion from CD3+ cells or mMDSC (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Motolimod induced depletion of mMDSC partially restores T cell activation.

IL-2 secretion from CD3+ cells treated with media, motolimod alone; and CD3+ cells stimulated with CD3/CD28, with mMDSC, and with mMDSC and Motolimod; and mMDSC treated with media and Motolimod. Columns and bars represent means (± SE) of 4 donors. * p<0.05.

Conclusions

Data presented here demonstrate that TLR8 is expressed in mMDSC and that selective TLR8 ligation can significantly reduce the levels of mMDSC in the peripheral blood via the induction of apoptosis. Reduction in the number of mMDSC in PBMC, mediated by TLR8 agonist treatment, will significantly enhance Type I cytokine secretion by activated T-cells. There is increasing evidence that MDSC contribute to the progression of cancer by inhibiting tumor-directed T-cells and producing mediators that promote the growth and survival of tumor cells [12, 32, 33]. Motolimod has a favorable safety profile when used as an immunotherapeutic in patients with cancer demonstrating limited toxicity and no evidence of cytokine storm [34]. One stragety would be to pre-condition patients with systemic infusion of motolimod to deplete MDSC prioir to therapy especially an immune-based therapy. Reducing MDSC, while activating T-cells, may synergize with cancer immunotherapeutic approaches and enhance the anti-tumor effects of the adaptive immune response.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

This work was supported by a commercial research grant from VentiRX Pharmaceutical (MLD.). MLD is also supported by a Komen Leadership Grant as well as the Athena Distinguished Professorship for Breast Cancer Research. Human samples from cancer patients were collected through the Clinical Research Center Facility at the University of Washington (NIH grant UL1TR000423).

Abbreviations

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- mMDSC

monocytic MDSC

- gMDSC

granulocytic MDSC

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- FL

fluorescence

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

MLD is a stockholder in Epithany and VentiRx and receives grant support from Celgene, EMD Serono, VentiRx and Seattle Genetics. HL is an employee of Immune Design. RH is an employee and has ownership (shares) in VentiRX. The remaining authors have no COI.

References

- 1.Lesokhin AM, Hohl TM, Kitano S, Cortez C, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Avogadri F, Rizzuto GA, Lazarus JJ, Pamer EG, Houghton AN, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD (2012) Monocytic CCR2(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Research 72, 876–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer C, Sevko A, Ramacher M, Bazhin AV, Falk CS, Osen W, Borrello I, Kato M, Schadendorf D, Baniyash M, Umansky V (2011) Chronic inflammation promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell activation blocking antitumor immunity in transgenic mouse melanoma model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 17111–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schouppe E, Van Overmeire E, Laoui D, Keirsse J, Van Ginderachter JA (2013) Modulation of CD8(+) T-cell activation events by monocytic and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunobiology 218, 1385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markowitz J, Brooks TR, Duggan MC, Paul BK, Pan X, Wei L, Abrams Z, Luedke E, Lesinski GB, Mundy-Bosse B, Bekaii-Saab T, Carson WE 3rd (2015) Patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma exhibit elevated levels of myeloid-derived suppressor cells upon progression of disease. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 64, 149–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergenfelz C, Larsson AM, von Stedingk K, Gruvberger-Saal S, Aaltonen K, Jansson S, Jernstrom H, Janols H, Wullt M, Bredberg A, Ryden L, Leandersson K (2015) Systemic monocytic-MDSCs are generated from monocytes and correlate with disease progression in breast cancer patients. PloS one 10, e0127028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirbod-Mobarakeh A, Mirghorbani M, Hajiju F, Marvi M, Bashiri K, Rezaei N (2016) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 31, 1246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koinis F, Vetsika EK, Aggouraki D, Skalidaki E, Koutoulaki A, Gkioulmpasani M, Georgoulias V, Kotsakis A (2016) Effect of first-line treatment on myeloid-derived suppressor cells’ subpopulations in the peripheral blood of patients with non-Small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 11, 1263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer C, Cagnon L, Costa-Nunes CM, Baumgaertner P, Montandon N, Leyvraz L, Michielin O, Romano E, Speiser DE (2014) Frequencies of circulating MDSC correlate with clinical outcome of melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 63, 247–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santegoets SJ, Stam AG, Lougheed SM, Gall H, Jooss K, Sacks N, Hege K, Lowy I, Scheper RJ, Gerritsen WR, van den Eertwegh AJ, de Gruijl TD (2014) Myeloid derived suppressor and dendritic cell subsets are related to clinical outcome in prostate cancer patients treated with prostate GVAX and ipilimumab. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer 2, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sade-Feldman M, Kanterman J, Klieger Y, Ish-Shalom E, Olga M, Saragovi A, Shtainberg H, Lotem M, Baniyash M (2016) Clinical significance of circulating CD33+CD11b+HLA-DR- myeloid cells in patients with stage IV melanoma treated with Ipilimumab. Clinical Cancer Research 22, 5661–5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura T, McKolanis JR, Dzubinski LA, Islam K, Potter DM, Salazar AM, Schoen RE, Finn OJ (2013) MUC1 vaccine for individuals with advanced adenoma of the colon: a cancer immunoprevention feasibility study. Cancer Prevention Research 6, 18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabrilovich DI and Nagaraj S (2009) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nature Reviews. Immunology 9, 162–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Zhang L, Zhu X, Wang Y, Liu W, Gong W (2015) Polysaccharide Agaricus blazei Murill stimulates myeloid derived suppressor cell differentiation from M2 to M1 type, which mediates inhibition of tumour immune-evasion via the Toll-like receptor 2 pathway. Immunology 146, 379–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunt SK, Clements VK, Hanson EM, Sinha P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S (2009) Inflammation enhances myeloid-derived suppressor cell cross-talk by signaling through Toll-like receptor 4. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 85, 996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray A, Chakraborty K, Ray P (2013) Immunosuppressive MDSCs induced by TLR signaling during infection and role in resolution of inflammation. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 3, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu H, Dietsch GN, Matthews MA, Yang Y, Ghanekar S, Inokuma M, Suni M, Maino VC, Henderson KE, Howbert JJ, Disis ML, Hershberg RM (2012) VTX-2337 is a novel TLR8 agonist that activates NK cells and augments ADCC. Clinical Cancer Research 18, 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietsch GN, Lu H, Yang Y, Morishima C, Chow LQ, Disis ML, Hershberg RM (2016) Coordinated activation of toll-like receptor8 (TLR8) and NLRP3 by the TLR8 agonist, VTX-2337, ignites tumoricidal natural killer cell activity. PloS one 11, e0148764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Disis ML, Dang Y, Coveler AL, Marzbani E, Kou ZC, Childs JS, Fintak P, Higgins DM, Reichow J, Waisman J, Salazar LG (2014) HER-2/neu vaccine-primed autologous T-cell infusions for the treatment of advanced stage HER-2/neu expressing cancers. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 63, 101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Disis ML, dela Rosa C, Goodell V, Kuan LY, Chang JC, Kuus-Reichel K, Clay TM, Kim Lyerly H, Bhatia S, Ghanekar SA, Maino VC, Maecker HT (2006) Maximizing the retention of antigen specific lymphocyte function after cryopreservation. Journal of Immunological Methods 308, 13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu H, Knutson KL, Gad E, Disis ML (2006) The tumor antigen repertoire identified in tumor-bearing neu transgenic mice predicts human tumor antigens. Cancer Research 66, 9754–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dang Y, Wagner WM, Gad E, Rastetter L, Berger CM, Holt GE, Disis ML (2012) Dendritic cell-activating vaccine adjuvants differ in the ability to elicit antitumor immunity due to an adjuvant-specific induction of immunosuppressive cells. Clinical Cancer Research 18, 3122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phan-Lai V, Dang Y, Gad E, Childs J, Disis ML (2016) The Antitumor efficacy of IL2/IL21-cultured polyfunctional Neu-specific T cells is TNFalpha/IL17 dependent. Clinical Cancer Research 22, 2207–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schouppe E, Mommer C, Movahedi K, Laoui D, Morias Y, Gysemans C, Luyckx A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA (2013) Tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets exert either inhibitory or stimulatory effects on distinct CD8+ T-cell activation events. European Journal of Immunology 43, 2930–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt SV, Nino-Castro AC, Schultze JL (2012) Regulatory dendritic cells: there is more than just immune activation. Frontiers in Immunology 3, 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackstein H, Knoche A, Nockher A, Poeling J, Kubin T, Jurk M, Vollmer J, Bein G (2011) The TLR7/8 ligand resiquimod targets monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation via TLR8 and augments functional dendritic cell generation. Cellular Immunology 271, 401–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardoso EC, Pereira NZ, Mitsunari GE, Oliveira LM, Ruocco RM, Francisco RP, Zugaib M, da Silva Duarte AJ, Sato MN (2013) TLR7/TLR8 activation restores defective cytokine secretion by myeloid dendritic cells but not by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in HIV-infected pregnant women and newborns. PloS one 8, e67036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Shirota Y, Bayik D, Shirota H, Tross D, Gulley JL, Wood LV, Berzofsky JA, Klinman DM (2015) Effect of TLR agonists on the differentiation and function of human monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Journal of Immunology 194, 4215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorden KB, Gorski KS, Gibson SJ, Kedl RM, Kieper WC, Qiu X, Tomai MA, Alkan SS, Vasilakos JP (2005) Synthetic TLR agonists reveal functional differences between human TLR7 and TLR8. Journal of Immunology 174, 1259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P, Chornoguz O, Ecker C (2012) Regulating the suppressors: apoptosis and inflammation govern the survival of tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC). Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 61, 1319–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinha P, Chornoguz O, Clements VK, Artemenko KA, Zubarev RA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S (2011) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells express the death receptor Fas and apoptose in response to T cell-expressed FasL. Blood 117, 5381–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss JM, Subleski JJ, Back T, Chen X, Watkins SK, Yagita H, Sayers TJ, Murphy WJ, Wiltrout RH (2014) Regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment undergo Fas-dependent cell death during IL-2/alphaCD40 therapy. Journal of Immunology 192, 5821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusmartsev S, Nefedova Y, Yoder D, Gabrilovich DI (2004) Antigen-specific inhibition of CD8+ T cell response by immature myeloid cells in cancer is mediated by reactive oxygen species. Journal of Immunology 172, 989–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Condamine T and Gabrilovich DI (2011) Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends in Immunology 32, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monk BJ, Brady MF, Aghajanian C, Lankes HA, Rizack T, Leach J, Fowler JM, Higgins R, Hanjani P, Morgan M, Edwards R, Bradley W, Kolevska T, Foukas P, Swisher EM, Anderson KS, Gottardo R, Bryan JK, Newkirk M, Manjarrez KL, Mannel RS, Hershberg RM, Coukos G (2017) A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of chemo-immunotherapy combination using motolimod with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent or persistent ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group partners study. Annals of Oncology 28, 996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.