Abstract

Systemic exposure to greater than optimal fluoride (F) can lead to dental fluorosis. Parental A/J (dental fluorosis susceptible) and 129P3/J (dental fluorosis resistant) inbred mice were used for histological studies and to generate F2 progeny. Mice were treated with 0ppm or 50ppm F in their drinking water for 60 days. A clinical criterion (modified Thylstrup and Fejerskov categorical scale) was used to assess the severity of dental fluorosis for each individual F2 animal. Parental strains were subjected to histological examination of maturing enamel. Fluoride treatment resulted in accumulation of amelogenins in the maturing enamel of A/J mice. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) detection was performed using phenotypic extreme F2 animals genotyped for 354 SNP-based markers distributed throughout the mouse genome followed by Chi square analysis. Significant evidence of association was observed on chromosomes 2 and 11 for a series of consecutive markers (p<0.0001). Further analyses were performed to examine whether the phenotypic effects were found in both male and female F2 mice or whether there was evidence for gender-specific effects. Analyses performed using the markers on chromosomes 2 and 11 which were significant in the mixed-gender mice were also significant when analyses were limited to only the male or female mice. The QTL detected on chromosomes 2 and 11 which influence the variation in response to fluorosis have their effect in mice of both genders. Finally the QTL in both chromosomes appear to have an additive effect.

Keywords: genetics, dental fluorosis, fluoride, mouse models

Introduction

Dental (enamel) fluorosis is an undesirable developmental defect of tooth enamel attributed to greater than optimal systemic fluoride exposure during critical periods of amelogenesis. DF is characterized by increased porosity (subsurface hypomineralization) with a loss of enamel translucency and increased opacity (Fejerskov et al. 1990). It is generally accepted that increasing DF severity correlates with increasing F exposure. However individual variation in DF severity can exist when F exposure is relatively constant in a community (Mabelya et al. 1994; Yoder et al. 1998). Our studies using inbred strains of mice indicate that genetic background plays a role in DF susceptibility and in fluoride's actions on bone biology (Everett et al. 2002; Vieira et al. 2005; Mousny et al. 2006; Yan et al. 2007). The mechanism(s) that underlie the development of DF remain elusive, as well as the precise stage of amelogenesis most affected by fluoride. Despite fluoride’ ability to interact at a physicochemical manner with tooth enamel the cellular target is the ameloblast (Pergolizzi et al. 1995). In chronic F exposure the maturation phase of enamel formation appears to be the target stage (DenBesten 1986; Richards et al. 1986; DenBesten and Thariani 1992). Retention of enamel matrix proteins due to reduced removal during enamel maturation, perturbation of extracellular transport , or initiation of ER stress response pathway indicate that some developmental process is possibly adversely affected by excessive F (DenBesten 1986; DenBesten and Thariani 1992; Matsuo et al. 1996; DenBesten et al. 2002; Kubota et al. 2005).

Material and Methods

Animals

Male and female A/J (DF susceptible) and 129P3/J (DF resistant) inbred mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, U.S.A.) at 5−6 weeks of age and were acclimated for one week prior to mating in reciprocal crosses to produce F1 hybrids. A panel of F2 mice was produced via sister: brother mating of F1s. At weaning each F2 animal was placed on NaF provided in the drinking water at concentration of 50ppm F ion for 60 days. Parental A/J and 129P3/J mice at 3-weeks of age were treated with 0ppm [F] or 50ppm [F] as controls for examiner calibration and for histological studies. The treatment duration permitted full development of dental fluorosis in the erupting incisors (fig. 1) (Everett et al. 2002). All animals were housed in the Division of Lab Animal Medicine facility within the Dental Research Center a fully AAALAC accredited unit and were maintained on a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle with an ambient temperature of 21°C. Mice were fed a constant nutrition LabDiet® 5001 (PMI® Nutrition International), which contained 0.95% calcium, 0.67% phosphorous, 4.5 IU/gm vitamin D3 and an average [F] of 6.56 ± 0.28 μg/gm. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Fig. 1.

Clinical images of incisors from dental fluorosis susceptible A/J and resistant 129P3/J mouse strains. Panels on the left are from mice treated 60 days with 0ppm [F] and panels on the right are from mice treated with 50ppm [F].

Sample collecting

Serum was collected from each mouse following euthanasia and then frozen at −80°C. Samples were randomly selected for fluoride determinations. Microdirect analysis of serum F was performed according to the method of (Vogel et al. 1990).

Dental fluorosis phenotyping

All mice were uniquely identified, and the two examiners (ETE and DY) performed independent assessment of DF status for each animal. The determination of DF was made clinically over the entire upper and lower incisor tooth surfaces according to a modified TF index (table 1)(Thylstrup and Fejerskov 1978; Fejerskov et al. 1994; Everett et al. 2002).

Table 1.

Classification of the characteristic clinical appearance of fluorotic incisor enamel in mice as modified from Thylstrup and Fejerskov 1978*

| TF score 0 | The normal translucency of the glossy creamy yellow enamel remains after wiping and drying of the tooth surface. |

| TF score 1 | Thin white opaque lines are seen running across the tooth surface. Such lines are found on all parts of the surface. The lines correspond to the position of the perikymata. |

| TF score 2 | The opaque white lines are more pronounced and frequently merge to form small cloudy areas scattered over the whole surface. |

| TF score 3 | Merging of the white lines occurs, and cloudy areas of opacity spread over many parts of the surface. In between the cloudy areas, white lines can also be seen. |

| TF score 4 | The entire surface exhibits a marked opacity or appears chalky white. Parts of the surface exposed to attrition or wear may appear to be less affected. |

Genotyping

Genomic DNA were prepared using the Puregene Tissue kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and quantitated by picogreen fluorometry. Genotyping was performed on the Illumina platform at The Mutation Mapping and Developmental Analysis Project (MMDAP; Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School)(Moran et al. 2006). Each mouse was genotyped for 354 SNP-based markers distributed throughout the mouse genome.

Histology

Prior to euthanasia mice were perfused with 10% NBF while under anesthesia. Tissues were collected and further fixed in ice cold NBF overnight followed by demineralization in 0.2M EDTA pH 7.2 containing 2% NBF. Mandibles were processed for routine histology. In order to obtain a representative stage of amelogenesis in maturing enamel, cross-sections at the level of the mesial root of the first mandibular molar were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Smith and Nanci 1989). Serial sections from the same stage of amelogenesis were dewaxed and rehydrated for immunohistochemistry. Following preincubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol and rinses in 0.03% Tween20 sections were subjected to primary polyclonal antibodies (rabbit anti porcine amelogenin, gift from Dr. James Simmer, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) or normal serum as a control. This primary antibody has been shown to have cross reactivity to rodent amelogenins (Uchida et al. 1991). Anti amelogenin immunoreactivity was visualized using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit (Rabbit IgG)(Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were counterstained using hematoxylin prior to examination.

Statistical analyses

Chi square analysis was performed to compare the genotypic distribution in the two groups of phenotypically extreme F2 mice as well as to examine whether the phenotypic effects were found in male and female mice combined or whether there was evidence for gender-specific effects. Statistical significance was reached when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Histology of normal and fluorotic enamel

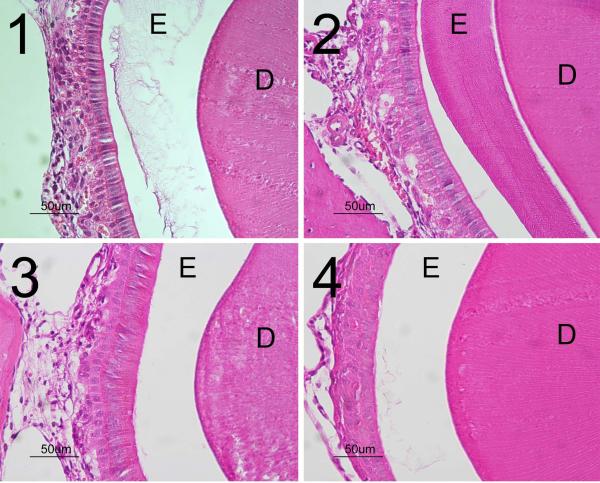

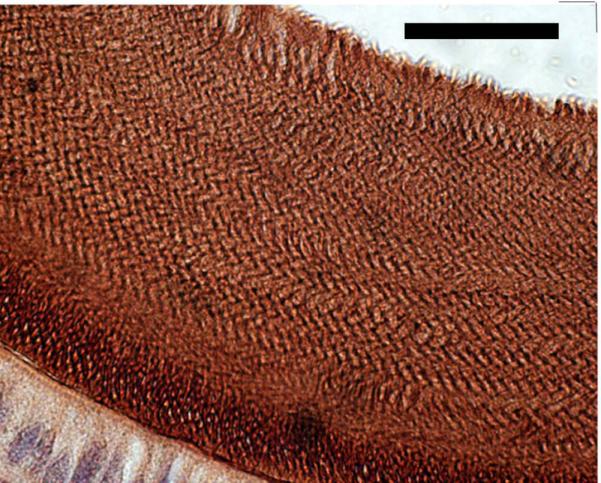

Delayed removal or persistence of matrix proteins was present in the maturing enamel of A/J mice. H&E serial cross sections through the mandibles of A/J mice at the level of the mesial root of the first molar reveal the presence of eosinophilic staining material in the enamel zone following EDTA demineralization in both control (0ppm [F]) and 50ppm [F] treated animals (fig. 2, panels 1 and 2). There was greater abundance in the enamel zone following F treatment. The 129P3/J mice had an enamel zone that was barren of material with only a small accumulation of proteineacous material following F treatment (fig. 2, panels 3 and 4). In order to better understand the composition of the accumulated matrix proteins in fluorotic A/J enamel we performed immmunohistochemistry using anti-amelogenin antibodies. Strong immunoreactivity was found in the enamel zone (fig. 3) and reflected the enamel rod pattern.

Fig. 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained cross sections of demineralized formalin fixed paraffin embedded mandibular incisors at the level of the molar mesial root in A/J (panels 1 and 2) and 129P3/J (panels 3 and 4) parental strains treated with 50ppm [F] (panels 2 and 4) or control 0ppm [F] (panels 1 and 3). E : enamel zone D: dentin

Fig. 3.

Anti-amelogenin immunohistochemical staining of the mandibular incisor enamel zone from an A/J mouse treated with 50ppm [F] (scale bar = 25 microns).

QTL identification and possible gender effects

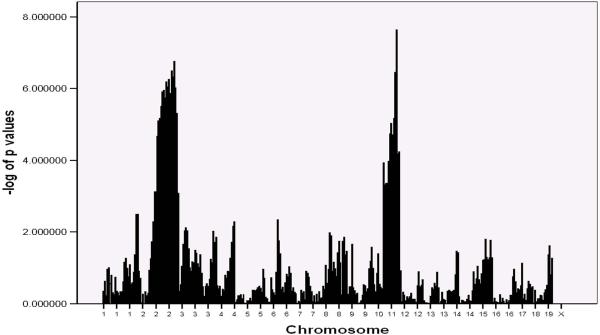

A F2 panel of 458 mice derived from A/J and 129P3/J parental strains were treated with 50ppm F in their drinking water for 60 days. Monitoring of F exposure was performed by serum F analyses in randomly selected F2s representing all 4 TF scales demonstrated a mean serum [F] of 12.366 ± 1.713 μM. The serum [F] values obtained in a cross section the F2 panel did not significantly differ from serum [F] determined in comparably treated parental mice (11.296 ± 3.984 μM). DF severity in the mandibular incisors was assessed in each individual F2 animal using clinical criteria (modified Thylstrup and Fejerskov scale, table 1). To maximize the power to detect QTLs contributing to the variation in response to dental fluorosis, only the phenotypic extreme F2 animals (102 animals with a score of 1 or 4) were genotyped for 354 SNP-based markers distributed throughout the mouse genome. These mice were composed of 55 males and 52 females. Chi square analysis was performed to compare the genotypic distribution in the two groups of phenotypically extreme F2 mice. Significant evidence of association was observed on chromosomes 2 and 11 for a series of consecutive markers (p<0.0001)(fig. 4). On chromosome 2 a QTL interval of approximately 77.62 Mb flanked by markers rs13476589 and UT_2_156.443943 was identified, and on chromosome 11 a QTL interval of approximately 74.29 Mb flanked by markers rs3708339 and rs6161623 was identified.

Fig. 4.

Genome-wide scan for dental fluorosis phenotypes for mouse Chromosomes 1−19 (excluding X and Y chromosomes). The p values obtained from Chi square analyses were converted to -log of p values and plotted on the y axis vs. the relative location along each chromosome on the x axis. Data are from 107 mice representing the phenotypic extremes of animals scored as either a clinical dental fluorosis of 1 or a 4 from a panel of 458 F2 mice.

We observed that female mice represented 74% of the F2s with a TF score = 1 and male mice represented 76% of the F2s with a TF score = 4. No such gender bias was previously observed with the two parental strains or with their F1 hybrid progeny (data not shown). These mice were subjected to analyses to examine whether the phenotypic effects were found in both male and female mice and whether there was evidence for gender-specific effects. Significant gender differences in the frequencies of mild (TF = 1) to severe (TF = 4) DF in the F2 panel were observed (Chi-Square, p < 0.0001). Analyses were performed to examine whether the phenotypic gender-specific effects contributed to possible differences in QTL detection. Analyses performed using the markers on chromosome 2 and 11 which were significant in the mixed-gender mice were also significant when analyses were limited to only the male or female mice. Therefore, the QTL in these two regions which influence the variation in response to DF has its effect in mice of both genders. Finally, preliminary analyses suggest that the QTL in both chromosomes appear to have an additive effect.

Discussion

The objective of the research was to determine what part of the mouse genome carries susceptibility to fluorosis and to investigate further the nature of the enamel defect in the F susceptible mice. For the former fluoride (F) sensitive and fluoride resistant inbred mice were mated, generating offspring (F2) that were each unique with respect to the mix of chromosomes they inherited from their parents. Their susceptibility to fluorosis was determined by providing them high F in the drinking water and then staging their fluorosis phenotypes using a modified TF index. As expected, the F2 mice varied with respect to their susceptibility to fluorosis, but unexpectedly F2 males and females varied in their susceptibility. To characterize what parts of the genome of these mice were inherited from the F susceptible and F resistant parents, each F2 mouse was “genotyped”, that is characterized for the presence 354 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) distributed throughout the genome. Statistical analyses were performed for the F2 mice that were the most F resistant and F susceptible to determine which parts of the genome correlate with these phenotypes. Our investigations of DF susceptibility/resistance QTL using A/J and 129P3/J inbred mice in the generation of F2 progeny was capable of detecting QTL on chromosomes 2 and 11. The QTL intervals detected in this study contain nearly 2000 genes. More importantly lack of significant evidence of association observed on chromosomes X, 3, 5, 7, or 9 suggest little role of amelogenin, ameloblastin, enamelin, amelotin, Klk-4, or Mmp20 in DF susceptibility/resistance in our animal model. We have no ready explanation for the gender differences observed in our F2 panel. Sex or gender differences in DF affecting humans have not been observed. Future studies will focus on narrowing the QTL intervals detected and in identifying candidate genes for further interrogation.

Separately, the nature of the enamel defect in the F susceptible mice was investigated. Histological analyses of the maturing EDTA soluble enamel from the DF susceptible A/J mouse strain following F exposure demonstrated an accumulation of matrix proteins composed in part of amelogenins. Interestingly some retention of matrix proteins was present in the 0ppm [F] treatment group of the A/J strain. The enamel zone of comparably staged 129P3/J incisor remained devoid of any proteinaceous material. The accumulation of enamel matrix proteins in the fluorotic enamel found in the A/J mice is consistent with many previous studies (DenBesten 1986; DenBesten and Thariani 1992; Den Besten 1999). We found detectable accumulation of matrix proteins in the non-fluorosed enamel of A/J mice suggesting that inherent differences in tooth enamel formation may exist between these two strains of mice. Previously we observed that baseline differences in enamel quality between A/J and 129P3/J mice. Using mircohardness as a criteria the incisor enamel of 129P3/J mice is approximately 22% harder than that in A/J (Vieira et al. 2005). More notably we found that F treatment (50ppm [F]) resulted in a greater loss of enamel microhardness in the A/J strain (71% reduction) compared to a 15% reduction in the 129P3/J strain. While the retention/persistence of matrix proteins in maturing enamel of A/J mice was greatly enhanced by systemic F exposure and likely contributed directly to the DF phenotype present in this strain new questions emerge regarding genetically determined variability in normal enamel formation.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Ms. Cynthia Suggs. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research grant DE014853.

List of abbreviations

- QTL

quantitative trait loci

- F

fluoride

- DF

dental fluorosis

- D

dentin

- E

enamel zone

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- NBF

neutral buffered formalin

References

- Den Besten PK. Mechanism and timing of fluoride effects on developing enamel. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:247–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1999.tb03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DenBesten PK. Effects of fluoride on protein secretion and removal during enamel development in the rat. J Dent Res. 1986;65:1272–1277. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DenBesten PK, Thariani H. Biological mechanisms of fluorosis and level and timing of systemic exposure to fluoride with respect to fluorosis. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1238–1243. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710051701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DenBesten PK, Yan Y, Featherstone JD, Hilton JF, Smith CE, Li W. Effects of fluoride on rat dental enamel matrix proteinases. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47:763–770. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(02)00117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett ET, McHenry MA, Reynolds N, Eggertsson H, Sullivan J, Kantmann C, Martinez-Mier EA, Warrick JM, Stookey GK. Dental fluorosis: variability among different inbred mouse strains. J Dent Res. 2002;81:794–798. doi: 10.1177/0810794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fejerskov O, Larsen MJ, Richards A, Baelum V. Dental tissue effects of fluoride. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8:15–31. doi: 10.1177/08959374940080010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fejerskov O, Manji F, Baelum V. The nature and mechanisms of dental fluorosis in man. J Dent Res. 1990:69. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690S135. Spec No:692−700; discussion 721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Lee DH, Tsuchiya M, Young CS, Everett ET, Martinez-Mier EA, Snead ML, Nguyen L, Urano F, Bartlett JD. Fluoride induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in ameloblasts responsible for dental enamel formation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23194–23202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabelya L, van 't Hof MA, Konig KG, van Palenstein Helderman WH. Comparison of two indices of dental fluorosis in low, moderate and high fluorosis Tanzanian populations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:415–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo S, Inai T, Kurisu K, Kiyomiya K, Kurebe M. Influence of fluoride on secretory pathway of the secretory ameloblast in rat incisor tooth germs exposed to sodium fluoride. Arch Toxicol. 1996;70:420–429. doi: 10.1007/s002040050294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JL, Bolton AD, Tran PV, Brown A, Dwyer ND, Manning DK, Bjork BC, Li C, Montgomery K, Siepka SM, Vitaterna MH, Takahashi JS, Wiltshire T, Kwiatkowski DJ, Kucherlapati R, Beier DR. Utilization of a whole genome SNP panel for efficient genetic mapping in the mouse. Genome Res. 2006;16:436–440. doi: 10.1101/gr.4563306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousny M, Banse X, Wise L, Everett ET, Hancock R, Vieth R, Devogelaer JP, Grynpas MD. The genetic influence on bone susceptibility to fluoride. Bone. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi S, Santoro A, Santoro G, Trimarchi F, Anastasi G. Enamel fluorosis in rat's incisor: S.E.M. and T.E.M. investigation. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol. 1995;38:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards A, Kragstrup J, Josephsen K, Fejerskov O. Dental fluorosis developed in post-secretory enamel. J Dent Res. 1986;65:1406–1409. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650120501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Nanci A. A method for sampling the stages of amelogenesis on mandibular rat incisors using the molars as a reference for dissection. Anat Rec. 1989;225:257–266. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092250312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O. Clinical appearance of dental fluorosis in permanent teeth in relation to histologic changes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1978;6:315–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1978.tb01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Tanabe T, Fukae M, Shimizu M, Yamada M, Miake K, Kobayashi S. Immunochemical and immunohistochemical studies, using antisera against porcine 25 kDa amelogenin, 89 kDa enamelin and the 13−17 kDa nonamelogenins, on immature enamel of the pig and rat. Histochemistry. 1991;96:129–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00315983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira AP, Hancock R, Eggertsson H, Everett ET, Grynpas MD. Tooth quality in dental fluorosis genetic and environmental factors. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;76:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel GL, Carey CM, Chow LC, Ekstrand J. Fluoride analysis in nanoliter- and microliter-size fluid samples. J Dent Res. 1990:69. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690S106. Spec No:522−528; discussion 556−527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Gurumurthy A, Wright M, Pfeiler TW, Loboa EG, Everett ET. Genetic background influences fluoride's effects on osteoclastogenesis. Bone. 2007;41(6):1036–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KM, Mabelya L, Robison VA, Dunipace AJ, Brizendine EJ, Stookey GK. Severe dental fluorosis in a Tanzanian population consuming water with negligible fluoride concentration. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:382–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]