Abstract

Egg activation is the essential process in which mature oocytes gain the competency to proceed into embryonic development. Many events of egg activation are conserved, including an initial rise of intracellular calcium. In some species, such as echinoderms and mammals, changes in the actin cytoskeleton occur around the time of fertilization and egg activation. However, the interplay between calcium and actin during egg activation remains unclear. Here, we use imaging, genetics, pharmacological treatment, and physical manipulation to elucidate the relationship between calcium and actin in living Drosophila eggs. We show that, before egg activation, actin is smoothly distributed between ridges in the cortex of the dehydrated mature oocytes. At the onset of egg activation, we observe actin spreading out as the egg swells though the intake of fluid. We show that a relaxed actin cytoskeleton is required for the intracellular rise of calcium to initiate and propagate. Once swelling is complete and the calcium wave is traversing the egg, it leads to a reorganization of actin in a wave-like manner. After the calcium wave, the actin cytoskeleton has an even distribution of foci at the cortex. Together, our data show that calcium resets the actin cytoskeleton at egg activation, a model that we propose to be likely conserved in other species.

Keywords: Egg activation, calcium wave, actin organization, oocyte-to-embryo transition, Drosophila development

INTRODUCTION

Production of female gametes is an important part of the faithful passage of genetic information from parents to offspring. Upon completion of oogenesis, mature oocytes remain developmentally arrested. They are triggered to resume development by egg activation, a series of conserved processes that include completion of meiosis to generate a haploid female pronucleus, structural changes in the extracellular matrix of the oocyte, translation and degradation of maternal mRNAs, rearrangement of the cytoskeleton, and modification of proteins (Horner and Wolfner, 2008; Kashir et al., 2014; Krauchunas and Wolfner, 2013; Miao and Williams, 2013; Sartain and Wolfner, 2013; Swann and Lai, 2016). All of these events are preceded by a transient rise in the intracellular level of free calcium (Kubota et al., 1987; Miao et al., 2002; Kaneuchi et al., 2015; York-Andersen et al., 2015; Bernhardt et al., 2018). This calcium rise, which can result from influx of extracellular calcium and/or the release of calcium from internal stores, leads to dramatic changes in the mature oocyte that prepare it for further development. Many of these changes require the activity of calcium-dependent kinases and phosphatases (Horner et al., 2006; Takeo et al., 2006; Takeo et al., 2010; Mochida and Hunt, 2007), which alter the phospho-proteome of the egg (Roux et al., 2008; Krauchunas et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2015; Presler et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019; reviewed in Krauchunas and Wolfner, 2013).

The trigger that initiates egg activation varies across species. In vertebrates, and some invertebrates, egg activation requires sperm entry. Significantly, in other invertebrates egg activation is independent of fertilization and can be initiated by changes in the ionic environment, variation in external pH, or mechanical pressure (reviewed in Horner and Wolfner, 2008).

In Drosophila melanogaster, egg activation is triggered by mechanical pressure during ovulation and does not require sperm (Heifetz et al., 2001; Horner and Wolfner, 2008). When a mature oocyte is ovulated and moves from the ovary to the lateral oviduct, it is thought to experience pressure and fluid uptake. This results in its swelling and a transient wave of increased cytoplasmic calcium that initiates from oocyte poles, predominantly the posterior, due to calcium influx through Trpm channels (Horner and Wolfner, 2008; Kaneuchi et al., 2015; Hu and Wolfner, 2019). This calcium influx and wave can be recapitulated ex vivo by submerging dissected mature oocytes in certain hypotonic buffers (Kaneuchi et al., 2015; York-Andersen et al., 2015). This experimental approach has shown that initiation of the calcium wave requires a functional actin cytoskeleton, as the presence of the actin-polymerization inhibitor Cytochalasin D results in a loss of the full calcium wave in the majority of oocytes (York-Andersen et al., 2015).

Changes in the actin cytoskeleton have previously been observed at fertilization and egg activation in multiple systems. In sea urchins, actin polymerizes around the sperm binding site to form a fertilization cone and facilitates the sperm-egg fusion that initiates egg activation events (Tilney, 1980). In mouse oocytes, actin is required for TRPV3 mediated calcium influx during parthenogenetic egg activation with strontium chloride, as the actin polymerization inhibitor Latrunculin-A blocks the calcium rise through TRPV3 activation (Lee et al., 2016). Furthermore, starfish eggs treated with ionomycin to raise the intracellular level of calcium show a perturbed actin cytoskeleton and fail to display the centripetal movement of filamentous actin (F-actin) (Vasilev et al., 2012). Together these data highlight potential regulatory interactions between the actin cytoskeleton and calcium at egg activation. However, a clear mechanistic understanding and detailed characterization of the interplay between calcium and actin at egg activation is lacking.

Here we use live imaging, pharmacological disruption, mechanical manipulation and genetics to determine the relationship between calcium and actin at egg activation in Drosophila. We show that actin has a broad distribution, filling in ridges that cover the cortex of the mature oocyte. Upon egg activation we report dispersal of the actin cytoskeleton concurrent with rounding of the cortex as the egg swells. The change in the actin cytoskeleton is required for the calcium wave. The calcium wave in turn is required for reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, which also proceeds in a wave-like manner. Moreover, we found that cortical actin is dynamic before and after egg activation as well. Regional pressure on mature oocytes can induce a local calcium rise with no increase of the local actin signal. Together, our data suggest that increased cytoplasmic calcium is necessary for actin reorganization. The co-dependence of the calcium wave and actin reorganization enables the mature oocyte to undergo the dramatic physiological and molecular changes required for initiation of further development. Since our model links calcium, a ubiquitous secondary messenger, to actin, a key cytoskeletal component, we expect that the interactions established in this study will be conserved in other species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks and reagents

The following fly stocks were used: matα4-GAL-VP16>UASp-GCaMP3 (as previously described Kaneuchi et al., 2015); UAS-Lifeact::mCherry (a gift from from Palacios Lab, QMUL); UAS-SpireB.tdTomato (a gift from the Quinlan Lab, UCLA); UASp-F-Tractin.tdTomato (RRID:BDSC_58988, 58989); UASp-Act5C-GFP (RRID:BDSC_7309); UAS-SCAR.RNAi (RRID:BDSC_36121). All UAS constructs were driven with matα4-GAL-VP16 (RRID:BDSC_7062, 7063).

Fly stocks were raised on either standard cornmeal–agar medium or yeast-glucose agar medium at 21°C or 25°C, mainly on a 12/12 light/dark cycle. Prior to dissection of the mature oocytes, female flies were fattened on yeast for 48 to 72 hours at 25C°.

BAPTA (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 10mM, Cytochalasin D (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10μg/ml, Phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 3.3nM, Latrunculin-A (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10μg/ml, 2-APB (Sigma-Aldrich) at 200μM, and RFP/mCherry booster (Atto 594) at 1:200 (ChromoTek).

Oocyte and embryo collection

Mature oocytes were dissected from the ovaries from fattened flies using a probe and fine forceps as described previously (Kaneuchi et al., 2015; York-Andersen et al., 2015). Embryos were collected for 30 minutes on apple or grape juice agar plates with yeast and then dechorionated in 50% bleach.

Ex vivo egg activation assay

Oocytes were activated with different, but equivalent preparation methods:

Dissected oocytes were placed in series 95 halocarbon oil (KMZ Chemicals) on 22×40 cover slips, aligned parallel to each other to maximize the acquisition area for imaging and left to settle for 10–15 minutes before addition of activation buffer (AB) and imaging (Derrick et al., 2016); AB contains 3.3 mM NaH2PO4, 16.6 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM NaCl, 50 mM KCl, 5% polyethylene glycol 8000, 2 mM CaCl2, brought to pH 6.4 with a 1:5 ratio of NaOH:KOH (Mahowald et al., 1983).

Oocytes were dissected in isolation buffer (IB) (Page and Orr-Weaver, 1997) in a glass-bottomed Petri dish and activated by replacing IB with modified Robb’s buffer (RB). IB contains 55mM NaOAc, 40mM KOAc, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1mM CaCl2, 110mM sucrose, 100mM HEPES in ddH2O. IB is adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH and filter-sterilized. RB contains 55mM NaOAc, 8mM KOAc, 20mM sucrose, 0.5mM MgCl2, 2mM CaCl2, 20mM HEPES in ddH2O. RB was adjusted to pH 6.4 with NaOH and filter sterilized (Hu and Wolfner, 2019);

For the high resolution 3D live imaging oocytes were mounted in a glass-bottomed culture dish (MatTek) in Schneider’s insect culture medium (GIBCO-BRL) with a 1 mm2 coverslip on the oocyte. For activation, Schneider’s medium was removed and replaced with AB (Weil et al., 2008).

Imaging

Mature oocytes were imaged using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope with Zen software under 10X 0.45NA water immersion objective with detection wavelength of 493–556 nm for GCaMP signal, and 566–691 nm for F-tractin signal. Z-stacks were taken from the shallowest to deepest visible plane of the oocyte. Z-stacks and time series of images taken were 3D reconstructed in Imaris software for final output. Image processing and analysis were performed using imageJ (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Alternatively, images were acquired with an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope, under 20× 0.7NA immersion objective with acquisition parameters of 500–570nm, 400Hz. Similar settings were used for the F-tractin cytoskeleton, with acquiring parameters of 570–700nm. The Z-stacks were taken from the shallowest visible plane of the oocyte and were acquired at 2μm per frame 40μm deep. The Z-stacks were presented as maximum projections of 40μm, unless stated otherwise.

High-resolution 3D images of the cortex were collected using an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope with Schneider’s mounting and activation preparation. Parameters for image collection were: 60x silicon immersion objective, 60μm Z-stack, 0.34μm between each Z-slice, 2048 × 2048 resolution of varying ROIs at the cortex, approximately 8–10 minutes per complete acquisition. Movie 1-5 show brightest point 3D projection with a Y-axis of rotation and 0.34μm slice spacing (120 z-frames). The display has an initial angle of 0°, total rotation of 150° and a rotation angle increment of 1°. Image processing and analysis were performed using imageJ (Schindelin et al., 2012) and displayed as a maximum Z-projection or 3D projections.

FRAP was carried out on the cortex of the mature oocyte using a UV laser on the Olympus FV3000 microscope for 15 seconds. The fluorescence recovery was recorded using Olympus FV3000 for 20 minutes. Samples were imaged under a 30× 1.05NA silicon immersion objective. Despite technical challenges due to swelling of activated eggs, we were able to visualize the bleached region clearly for approximately 100 seconds after photobleaching. A partial calcium wave is defined as one that initiates but fails to completely traverse the entire oocyte; A full (or complete) calcium wave is defined as one that is able to traverse the entire oocyte.

Microneedle manipulation

Microneedles were fabricated from borosilicate glass rods (catalog no. BR-100–15, Sutter Instrument), in a Sutter model P97 flaming/brown micropipette puller, with the following program: heat=490, pull=0, velocity=25, time=250. Mature oocytes of the indicated genotype were incubated in a glass bottom Petri dish in 100 μl of IB that contains propidium iodide (PI, Molecular probes) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml as an indicator of plasma membrane (PM) integrity. Since the PM is not permeable to PI, PI staining at the microneedle pressing site would suggest damage to the PM and false calcium signal by calcium in IB entering through PM breach. To manipulate the oocyte, the microneedle was attached to and manipulated with an Eppendorf Injectman NI 2 micromanipulator. The indicated regions of mature oocytes were pressed with the microneedle until a calcium rise occurred as visible with GCaMP. Oocyte calcium and actin dynamics were observed for 20 min.

RESULTS

Actin reorganizes and is more dynamic during Drosophila egg activation

Throughout Drosophila oogenesis, actin plays a role in tissue morphogenesis, signaling cascades, localization of mRNAs, and maintaining the integrity of the cortex (Spracklen et al., 2014b; Wang and Riechmann, 2007; Weil et al., 2008). In order to establish the distribution of the actin cytoskeleton prior to egg activation in the mature oocyte, we used the actin indicator F-tractin. Generated from the rat actin-binding inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3- kinase A, F-tractin has been shown to closely correlate with Phalloidin staining and is suggested to be the least invasive actin probe in Drosophila follicle development (Schell et al., 2001; Spracklen et al., 2014a).

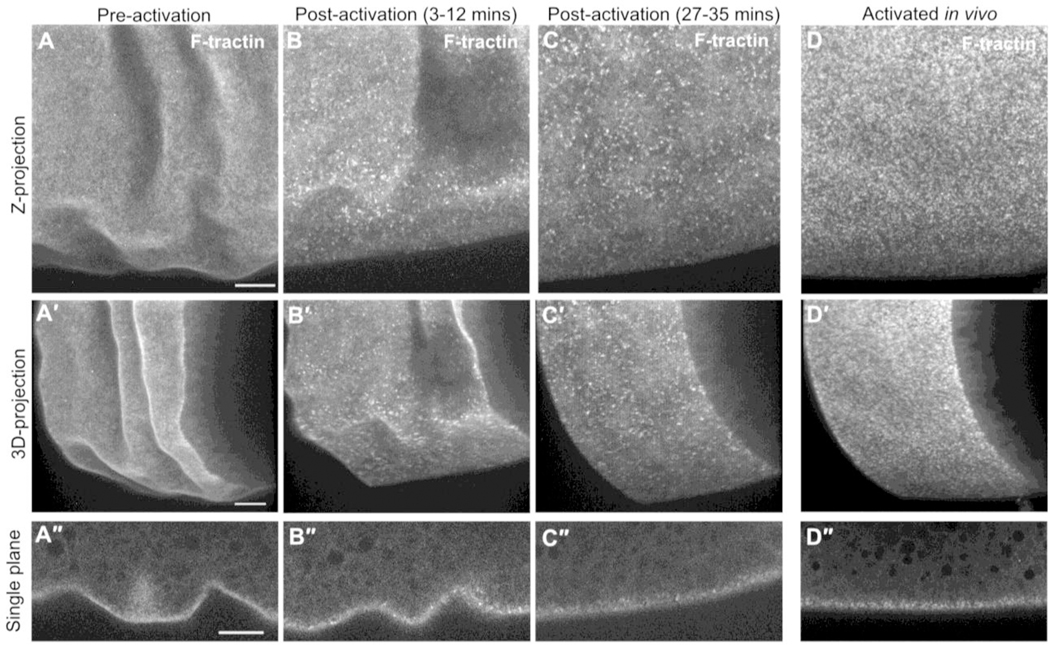

In order to observe the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton at live egg activation, we took advantage of an established ex vivo egg activation protocol (Weil et al., 2008) which enabled us to collect high-resolution 3D images at different time points. This showed that prior to egg activation, actin is finely distributed around well-defined ridges in the dehydrated mature oocyte (Figure 1A–A′′, Movie 1). Following egg activation ex vivo, actin initially dispersed and was then reorganized into larger, more widely distributed foci (Figure 1B–C′′, Movie 2 and 3). We observed the same reorganization of actin in the in vivo activated egg (Figure 1D–D′′, Movie 4) and in the early embryo (Supplemental Figure 1, Movie 5).

FIGURE 1. Actin is reorganized at egg activation.

Time series of an ex vivo activated mature oocyte (A-C, n=6) and in vivo activated egg (D, n=4) expressing F-Tractin.tdTomato. Maximum Z-projection (A-D), 3D-projection at a 45° angle (A′-D′) and a single Z-plane at 20μm depth (A′′-D′′) are shown for each time point. Images were acquired using an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope.

(A-A′′) Prior to the addition of activation buffer, actin is in a smooth cortical distribution around ridges in the cortex (as shown in Movie 1).

(B-C′′) Following egg activation (3–12 minutes, as shown in Movie 2) and (27–35 minutes, as shown in Movie 3), actin is reorganized in larger, more widely distributed foci. 3D-projection shows that the cortex has expanded and that actin is no longer associated with the ridge. Single plane images show that a cortical enrichment pre-activation is lost and that actin is not as enriched at the cortex after activation.

(D-D′′) In vivo activated eggs collected from the oviduct have a similar actin distribution as mature oocytes activated ex vivo (compare C-C′′ (Movie 3) to D-D′′ (as shown in Movie 4)). Scale bar, 10 μm (A-D′).

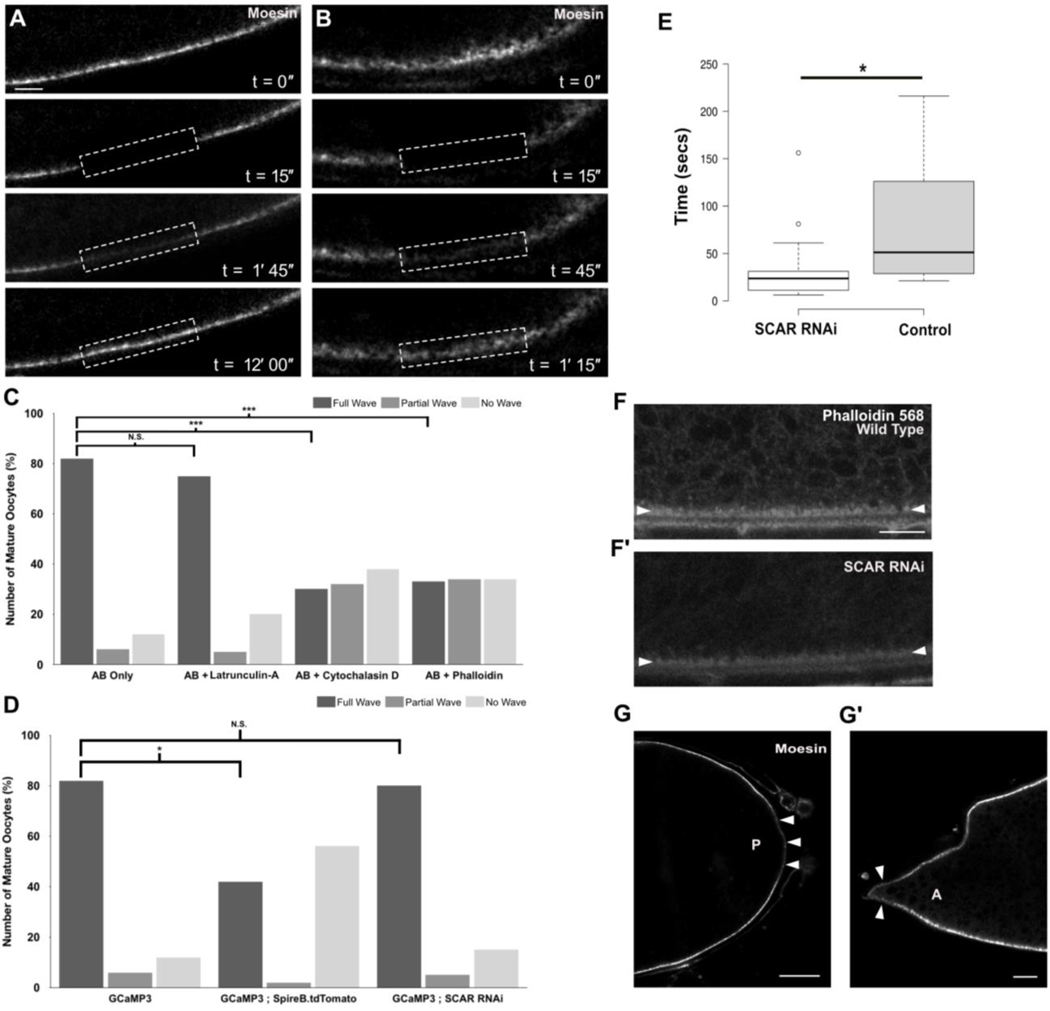

To test the dynamics of actin before and after egg activation, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) on mature oocytes expressing GFP-Moesin, which is comprised of the C-terminal actin-binding domain of Moesin, a transmembrane protein and member of the ERM family, labelling only actin at the cortex (Edwards et al., 1997). By measuring the mean fluorescence intensity, we observed a more rapid recovery of GFP-Moesin after photobleaching in activated versus mature eggs. Pre-activation, GFP-Moesin has a recovery halftime of 45 seconds, compared to post-activation in which the recovery halftime is 14 seconds (n=5, Figure 2A–B). We have also tested the recovery of the actin marker Act5C-GFP (Weil, 2006), and find similar FRAP recovery times before and after egg activation (41 seconds versus 20 seconds, respectively (n=5, Supplemental Figure 2). The difference in GFP-Moesin (and Act5C-GFP) recovery before and after egg activation suggests an increased turnover of cortical actin and/or stabilization of F-actin, either of which could result in increased recruitment of GFP-Moesin.

FIGURE 2. A dynamic actin cytoskeleton is required for a calcium wave at egg activation.

(A-B′,G,G′) Egg chamber expressing GFP-Moesin. Images were acquired using an Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope.

(A-B) Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of GFP-Moesin before and after ex vivo egg activation (n=5). GFP-Moesin labeling actin at the lateral cortex is reduced to 25% of original fluorescent intensity following a bleach step. In both stage 14 mature egg chambers before activation (A) and after activation (B) recovery can be detected. In the unactivated oocyte, full recovery is complete at 12 minutes post-bleaching. However, in the activated oocyte recovery is substantially faster post-activation (14 seconds versus 45 seconds recovery halftime, n=5). Note that movement caused by the addition of activation buffer meant recovery could only be recorded for 1 minute and 15 seconds post-bleach. Dashed white box denotes bleached region.

(C) Graph showing calcium wave phenotypes when mature oocytes are treated with activation buffer and the actin perturbing drugs Latrunculin-A, Cytochalasin-D, or Phalloidin. A ‘full wave’ indicates the calcium wave traversed the whole oocyte, a ‘partial wave’ indicates that the calcium wave initiated but did not traverse the whole oocyte, and a ‘no wave’ phenotype indicates that a calcium wave never initiated. When only AB is added, 82% of oocytes displayed full waves. Addition of Latrunculin-A shows a non-significant decrease in full waves to 72% (n=20, P=0.5). Mature oocytes treated with Cytochalasin-D or Phalloidin show a significant decrease in full waves observed to 28% and 32% respectively (n=35 for each, Fisher’s Exact statistical analysis, P=0.0001 (***))

(D) Graph showing calcium wave phenotypes when mature oocytes are treated with AB in GCaMP3 controls, over expression of SpireB and knockdown of scar. When SpireB is over-expressed there is a significant decrease, to 40%, in the number of activated mature oocytes that show a full calcium wave, and an increase in the number of ‘no wave’ phenotypes to 58% (n=12, Fisher’s Exact statistical analysis, P<0.05). When scar is knocked down using RNAi, there were no significant changes in the calcium wave phenotype.

(E) Boxplot showing the speeds of calcium entry into the mature oocyte in control (GCaMP3) and scar RNAi mature oocytes (n=15 and n=18). Speed of calcium entry was determined as the time taken from addition of AB to the time of first GCaMP fluorescence detected in the oocyte. Initial calcium entry was observed by eye and confirmed through quantification of the fluorescent signal, using a threshold of a 10% increase from the oocyte background. Images were taken every 3 seconds. There was a significant decrease in the time taken for calcium to enter the oocyte in the scar RNAi background (P<0.05).

(F, F′) Stage 14 egg chambers fixed and labelled for actin with Phalloidin (n=10). More actin is detected at the cortex in a wildtype egg chamber (F) compared to a scar RNAi expressing egg chamber (F′). White arrowheads mark the lateral cortex of the egg chamber.

(G, G′) In the stage 14 egg chamber, prior to egg activation, GFP-Moesin is less enriched at the posterior pole (G) of the oocyte (white arrowheads) as compared to elsewhere of the oocyte cortex (paired t-test P<0.05, n=20). Observation of GFP-Moesin at the anterior pole was challenging due to the presence of the dorsal appendages. However, in some (~40%, n=25) oocytes Moesin is depleted compared to the lateral cortex (G′) and in these oocyte the depletion is significant (paired t-test P<0.05, n=10).

Single plane image (A,B,F,G). Scale bar, 10μm (A-B), 20μm (F,G).

Dynamic actin is required for a calcium wave during egg activation

The dispersal of actin appeared to occur prior to the previously established timing of the calcium wave associated with egg activation (Kaneuchi et al., 2015; York-Andersen et al., 2015). Moreover, previous work suggested that the calcium wave might depend on a freely dynamic actin cytoskeleton (York-Andersen et al., 2015). To confirm this relationship, we treated mature oocytes expressing the calcium indicator GCaMP3 with activation buffer (AB) mixed with Phalloidin, a class of filament stabilizing phallotoxins (Cooper, 1987). Upon the addition of this solution, the mature oocytes swelled but exhibited a disrupted calcium wave in 68% of the oocytes, as the majority of phenotypes observed were partial or no waves (Figure 2C, n=35). We also elaborated on previous data and showed that when mature oocytes were treated with AB and Cytochalasin D, 72% displayed a disrupted calcium wave (Figure 2C, n=35) (York-Andersen et al., 2015). Notably, full calcium waves, defined as a wave of calcium which traverses the entire oocyte, were observed in some oocytes. This is likely due to incomplete inhibition by the drug, and in these cases swelling of the oocyte occurred as normal. Higher concentrations of the drugs did not change the observed calcium wave phenotypes.

In addition to disrupting F-actin, we tested the effect of reducing the pool of globular actin (G-actin) monomers by treating mature oocytes with AB and Latrunculin A, which binds the G-actin monomers and prevents actin assembly (Yarmola et al., 2000). Upon the addition of this solution, the majority of oocytes showed a full calcium wave (75%, n=20), not significantly different from wildtype. Together these pharmacological disruptions suggest that the calcium wave is dependent on a dynamic F-actin network and can occur without de novo actin assembly from G-actin monomers (Figure 2C).

We next hypothesized that excess polymerized F-actin in the mature oocyte would disrupt the calcium wave. To test this, we over-expressed the actin nucleation factor Spire B (Dahlgaard et al., 2007; Quinlan et al., 2005; Wellington et al., 1999) and observed the calcium wave. We found that additional Spire B leads to a reduction (42% versus 85%) in the number of mature oocytes that showed a wildtype calcium wave (Figure 2D, n=12 and n=30). In those eggs that did show a calcium wave, we observed a delay of 5–10 minutes in the initiation of the wave. These results corroborate the Phalloidin data that showed excess or a stabilized actin cytoskeleton to be inhibitory to the calcium wave at egg activation.

Finally, we tested if reducing F-actin assembly prior to egg activation would allow for a faster entry of calcium into the egg at activation. We used RNAi against scar, an activator of the Arp2/3 complex, to disrupt the nucleation of the actin network (Zallen et al., 2002). We showed that while the number of mature oocytes that showed a normal calcium wave is equal to wildtype, knockdown of scar resulted in calcium entering the egg more quickly than in controls (Figure 2E). Moreover, we observed a decrease in the concentration of actin at the cortex in scar knockdown egg chambers (Figure 2F–F′). This supports a model where a spreading or reduction of actin at the cortex allows for calcium entry. In addition, we observed that the cortical actin marker GFP-Moesin was less concentrated at the posterior pole (Figure 2G), and in some cases at the anterior pole (Figure 2G′). This could explain why there is a higher occurrence of calcium waves from the posterior pole of mature oocytes when activated ex vivo.

Taken together, these data support a model in which an intact and dynamic F-actin cytoskeleton, but not de novo assembly of F-actin, is essential to regulate the initiation of the calcium wave.

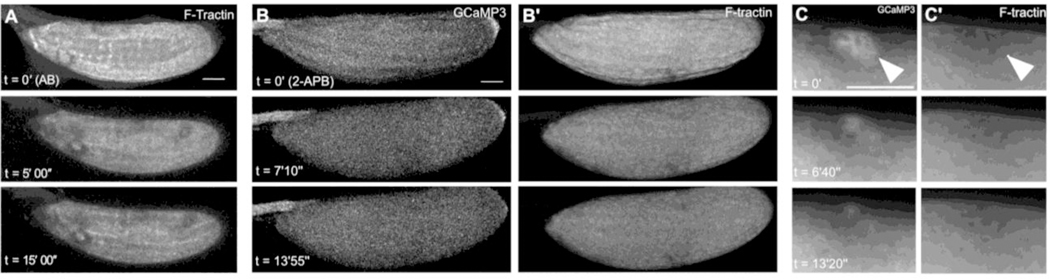

A wavefront of actin follows the calcium wave during egg activation

We next examined actin dynamics following the calcium wave in ex vivo egg activation. We used a germline driver to express markers for both calcium and F-actin simultaneously during Drosophila egg activation. Using AB to activate the mature oocyte we observed and analyzed a calcium wave and a wavefront of actin (Figure 3A–A′, Movie 6). Analysis shows that the actin wavefront (Figure 3B, Movie 7) lags behind the calcium wave at initiation by approximately two minutes and completes propagation across the oocyte approximately four minutes after the calcium wave. A similar phenomenon is observed with recovery of both waves, actin trailing calcium. (see Figure 3A legend for details). We confirmed this result using Robb’s Buffer (RB) to initiate egg activation and show that the speed of the F-tractin wavefront is similar to that of the calcium wave (0.56 μm/sec) (Supplemental Figure 3, Movie 8). The average times of the calcium wave and the F-actin wavefront highlights the similarities between the dynamics of these waves.

FIGURE 3. Actin wavefront dynamics follow calcium changes at egg activation.

Time series of a mature egg chamber co-expressing GCaMP3 and F-Tractin.tdTomato (A), or only expressing F-Tractin.tdTomato (B) or Lifeact::mCherry (C).

(A) At activation with activation buffer (AB) (n=9), a calcium wave (A) initiates from the posterior pole (t=0′) and propagates across the entire egg. A corresponding wavefront of F-tractin (A′) initiates from the posterior pole and traverses the egg. Analysis of the fluorescence intensity shows that the calcium wave initiates on average 106 seconds after the addition of AB (SEM=11.5 seconds), traverses the whole oocyte by 267 seconds (SEM= 42 seconds) and has recovered back to its initial level by 737 second (SEM = 148.37 seconds). A wave of F-actin follows behind this calcium wave, initiating on average 220 seconds after the addition of AB (SEM = 60 seconds). The actin wave traverses the whole oocyte by 503 seconds (SEM = 72 seconds) and has recovered to its initial state by 829 seconds (SEM = 222 seconds). On average, the F-actin wave lags behind the calcium wave by 103 seconds. As shown in Movie 6. Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope sequentially, with a scan time of ~30 second per z-stack.

(B) F-actin, labelled by F-tractin (n=15), shows a posterior to anterior wavefront following addition of AB (t=0′). The wave initiates (t=4′), propagates across the oocyte to the anterior pole (t=10′) and recovers (t=16′). As shown in Movie 7. Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

(C) F-actin, labelled by Lifeact (n=10), shows a similar actin wavefront as F-tractin (B) in its initiation (t=3′), propagation (t=9′30″) and recovery (t=15′). The bright fluorescence outside of the egg chamber is ovarian tissue associated with the dissection. As shown in Movie 9. Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

Image a projection of 40μm (A, B, C). Scale bar, 60μm (A-C).

To verify the discovery of an actin wavefront at Drosophila egg activation, we also tested the widely used in vivo actin marker Lifeact, a 17-amino acid peptide from yeast Abp140 (Riedl et al., 2008). At egg activation, Lifeact showed an increase in fluorescence from the posterior pole that propagated across the oocyte in a wave-like manner (Figure 3C, Movie 9). The speed of the wave was consistent with that of F-tractin. Overall, using multiple activation methods and F-actin markers, we demonstrate that the calcium wave during egg activation is followed by a wavefront of F-actin reorganization.

The calcium wave is necessary to sustain the actin wavefront

Our previous observation that the actin wavefront follows the calcium wave with a similar speed and direction, suggests that the actin wavefront may be dependent on the calcium wave. To test this dependence, we used a genetic approach to assess the requirement of a calcium increase for the F-actin wavefront at egg activation. Our previous work has shown that the calcium wave does not occur in a sarah mutant (York-Andersen et al., 2015). sarah encodes a key protein in the calcium signaling pathway that regulates the calcium dependent phosphatase calcineurin (Horner et al., 2006; Takeo et al., 2006, Takeo et al., 2010). F-actin visualized in a sarah mutant background revealed normal swelling of the mature oocyte but no change in the in F-actin distribution or levels (Figure 4A, n=12).

FIGURE 4. Actin wavefront requires the calcium wave at egg activation.

Time series of mature egg chamber expressing F-Tractin.tdTomato (A) or mature egg chambers co-expressing (B,C) GCaMP3 and F-Tractin.tdTomato (B′,C′).

(A) Time series of mature egg chambers expressing F-Tractin in a sarah mutant background (sraA108/sraA426) (n=7). Addition of AB to mature egg chambers causes an initial dispersion of cortical actin (t=4′), but does not initiate a wavefront of F-actin (t=15′). Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

(B-B′) Addition of 2-APB (a TRP and IP3 pathway inhibitor) to RB prevents initiation of the calcium wave and an F-actin wavefront is not observed (t=13′55″) (n=14). Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope.

(C-C′) Application of pressure to the lateral cortex of the mature egg chamber induces a local increase calcium (C) (white arrowhead, t=0′) (n=12). This local increase recovers over time (t=9′30″). Application of pressure does not result in a local F-actin increase (C′) (white arrowhead, t=0′), nor does it trigger an F-actin wavefront. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope.

Image a projection of 40μm (A) or 90μm (B,C). Scale bar, 60μm (A-C).

Next, we inhibited the calcium wave upon egg activation with the addition of 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB). Calcium waves at the oocyte pole(s) initiate due to influx of external calcium through the Trpm channel (Hu and Wolfner, 2019). Propagation of the waves through the oocyte requires the IP3R (Kaneuchi et al., 2015). 2-APB is a known ion channel inhibitor that has been experimentally used to block of both TRP channels and IP3R (Clapham et al., 2001; Maruyama et al., 1997). We observed that addition of 2-APB results in no calcium wave or F-actin wavefront, despite the oocytes swelling normally (Figure 4B–B′, n=14), again supporting the conclusion that the calcium wave is necessary for the F-actin wavefront.

To test the sufficiency of the calcium rise in the induction of an actin wavefront, we initiated a regional calcium rise via local pressure with a microneedle. In order to ensure that the induced calcium rise was not caused by calcium leaking in due to a damaged plasma membrane, we included propidium iodide (PI) dye in the IB to indicate plasma membrane damage. We observed that regional pressure by a microneedle can induce a local calcium rise without damaging the oocyte plasma membrane (Figure 4C). However, a calcium rise induced by such local pressure did not spread beyond the induction site or change the actin network (Figure 4C′, n=12). This argues that regional pressure can cause a local calcium rise, but that an additional factor(s) is required to reorganize the actin cytoskeletal network.

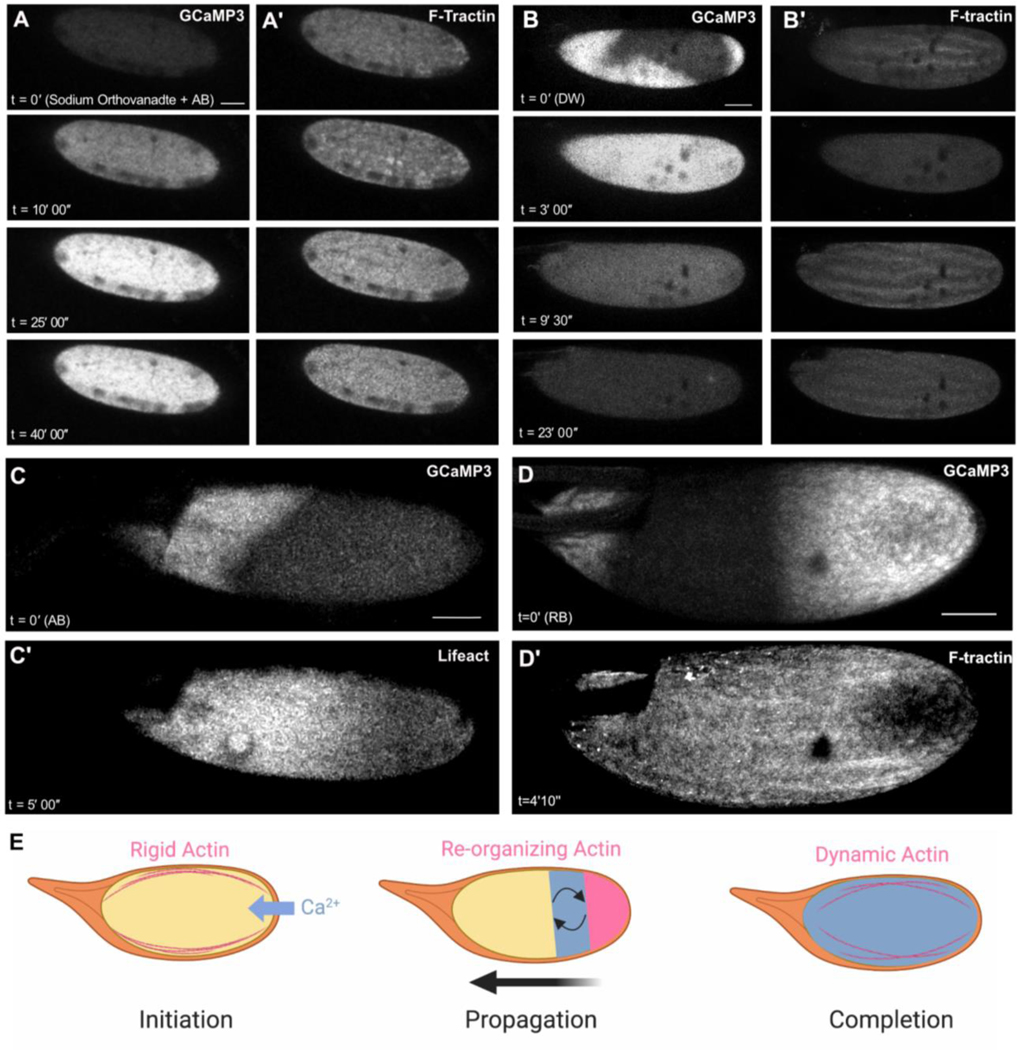

We therefore assessed whether sustaining a global calcium signal is sufficient to maintain the increase we observed in F-actin. To test this, we treated mature oocytes with sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), an ATPase inhibitor, dissolved into AB (Figure 5A–A′). Upon addition of AB with Na3VO4, the calcium rise no longer recovered to basal levels and we found that the F-actin signal also remained elevated. These data suggest that a prolonged global calcium rise may be sufficient to maintain a higher actin signal post-activation and suggest that there is an ATP-dependent mechanism in recovery and extrusion of calcium after activation. However, we make this suggestion with caution, as Na3VO4 has numerous effects on cells.

FIGURE 5. Pattern of actin reorganization follows calcium changes.

Time series of mature egg chambers co-expressing GCaMP3 and F-Tractin.tdTomato (A,B,D) or co-expressing GCaMP3 and Lifeact::mCherry (C).

(A-A′) Addition of activation buffer (AB) with sodium orthovanadate initiates a calcium wave that is sustained (t=40′) (n=10). An increase in F-actin is similarly seen and is also maintained (t=40′). Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

(B-B′) Following addition of distilled water (DW) (n=20), the mature egg chamber undergoes a global increase in intracellular calcium (t=0′) which slowly recovers to basal levels (t=15′). F-actin displays an initial dispersion (t=3′) followed by a global increase (t=9′30″). As shown in Movie 10. Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

(C) Following addition of AB (n=5), the calcium wave initiates from the anterior pole (t=0′) and is followed by the wavefront of F-actin from the same pole (t=5′). Images were acquired using an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

(D) Following addition of Robb’s Buffer (RB) (n=4), the calcium wave initiates from both anterior and posterior poles (t=0′) and traversing the oocyte (t=4′10″). The F-actin wavefront initiates at the same sites as the calcium wave (t=4′10″) and propagates in a similar manner. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope.

(E) Diagram showing interaction between calcium and actin during Drosophila egg activation. Cortical actin is relatively rigid before egg activation. It is less dense near the oocyte poles, where calcium waves initiate ex vivo. The calcium wave that progresses through the oocyte precedes a wavefront of actin reorganization. The actin wave and the calcium wave display similar speeds and are inter-dependent for propagation and completion. After completion of the calcium wave, cortical actin appears more dynamic in distribution. Actin is represented in pink and calcium in blue. Diagram is created with BioRender.com.

Image a projection of 40μm (A-C) or 90μm (D). Scale bar, 60μm (A-D).

To further investigate the dynamics of actin following a calcium rise, we observed the F-actin phenotype when mature oocytes were treated with distilled water. This treatment results in a rapid swelling of the oocyte and a calcium increase from multiple points at the cortex (Figure 5B, Movie 10). Following this pattern of calcium rises, we observed a similar pattern of actin increase approximately four minutes later (Figure 5B′). Interestingly, this assay suggests that all regions of the cortex have the potential to initiate a calcium wave that spreads through the oocyte and that stressing the system with excessive fluid uptake results in the loss of spatio-temporal control of the calcium entry and resulting actin reorganization.

Finally, we observe that in some wildtype ex vivo activation events, the calcium wave initiated from the anterior pole or from both poles (Kaneuchi et al., 2015). Consistent with our experimental manipulations of the calcium rise and subsequent actin changes, we found that the actin wavefront started from the anterior pole in all of the oocytes that showed the anterior calcium wave, and from both poles when calcium wave initiated from both poles (Figure 5C–D′). Taken together, our data suggest that initiation of the calcium wave is necessary to induce a wavefront of F-actin reorganization, and a global but not regional calcium rise may be sufficient in maintaining the actin wave and in coordinating its directionality.

DISCUSSION

Actin plays an essential role in fertilization and egg activation in many organisms. However, its functions in these aspects of Drosophila reproduction have not been fully explored. In this study, we showed that F-actin disperses and become more dynamic during Drosophila egg activation, and that this dynamic actin cytoskeletal network is required for a normal calcium wave to occur during ex vivo egg activation (Figure 5E). Moreover, the calcium wave mediates a reorganization of F-actin in a wave-like manner. This F-actin wavefront follows, requires, and has similar characteristics to the calcium wave. Together, these findings suggest a highly co-regulated calcium and actin signaling network in Drosophila oocytes during egg activation.

The importance of the actin cytoskeleton in egg activation

Our work demonstrates that in Drosophila, actin dynamics are important for the calcium rise which in turn leads to a reorganization of F-actin. Rearrangement of F-actin appears to be a common feature of oocytes undergoing egg activation. The reorganization of F-actin following exposure to osmotic pressure in zebrafish oocytes mediates the release of the cortical granules (Becker and Hart, 1999; Hart and Collins, 1991). More recent work in zebrafish has shown that the actin-binding factor, Aura, mediates this reorganization of actin and that in a mutant Aura background F-actin does not rearrange, and cortical granule exocytosis is inhibited (Eno et al., 2016).

Our data are reminiscent of events in starfish, where a pharmacologically-induced calcium rise results in depolymerization of surface actin and polymerization of F-actin bundles within the cytoplasm (Vasilev et al., 2012). Starfish oocytes also exhibit actin rearrangements at egg activation that are required for the calcium release at the cortex (Kyozuka et al., 2008). This calcium wave initiates a PIP2 increase at the starfish cortex in a biphasic manner, whereas pharmacological inhibition of PIP2 results in a delayed calcium wave and disrupted actin organization (Chun et al., 2010).

Functions of the actin wavefront

It is hypothesized that F-actin waves are essential for actin self re-assembly after its initial dispersion at the cortex and are thought to mediate the polymerization of actin (Bretschneider et al., 2009; Case and Waterman, 2011). For example, pharmacological depolymerization of actin results in an increased number of actin waves in Dictyostelium (Bretschneider et al., 2009). A similar observation was made in fibroblasts, where actin waves take form of “circular dorsal ruffles”, which are non-adhesive actin structures found on the dorsal side of some migrating cells (Bernitt et al., 2017; Bernitt et al., 2015; Chhabra and Higgs, 2007). Moreover, the F-actin wave is proposed to be associated with actin-binding factors, including Arp2/3, Myosin B, CARMIL and coronin. Live visualization of these factors in Dictyostelium cells have shown their enrichment at the leading edge of the F-actin wavefront (Bretschneider et al., 2009; Khamviwath et al., 2013). Together, this provides other examples of how the reorganization of F-actin can trigger F-actin waves. By analogy, the F-actin wavefront we observed during Drosophila egg activation might serve a similar purpose of reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton to facilitate further developmental events in embryogenesis.

Calcium and actin co-regulatory networks

Our work suggests a pathway of actin-calcium interdependence as initial calcium entry is enabled at the poles, where we see a breakdown of the actin cytoskeleton at the cortex, and this calcium increase is required to generate a global reorganization in the actin population. Calcium is thought to regulate the actin cytoskeleton predominantly via actin-binding factors, including myosin, profilin and villin/gelsolin (reviewed in Hepler, 2016). Early experiments showed that calcium regulates muscle contractions via myosin V protein, rather than directly through the actin filaments (Szent-Györgyi, 1975). In this case, calcium binds troponin that, in turn, binds tropomyosin to mediate the actin-myosin contraction cycle (Lehman et al., 1994). Similarly, plants utilize the actin-myosin network for cytoplasmic streaming, and actin is again regulated by calcium signaling via myosin XI (Tominaga et al., 2012). Calcium can also control actin dynamics via profilin, an actin-binding factor, which is required for F-actin polymerization (Vidali and Hepler, 2001). Experiments with profilin show that calcium inhibits F-actin polymerization by sequestering actin monomers and profilin subunits, which are no longer able to form the actin filaments (Kovar, 2000). Calcium causes depolymerization or severing of the actin cytoskeleton via villin actin-binding factor and was shown to aid the organization of actin in epithelial intestinal cells (Walsh et al., 1984).

One especially interesting factor is α-Actinin, an actin cross-linking protein that is a member of the spectrin family and is found primarily on F-actin filaments in non-muscle cells. α-Actinin has been suggested to cross-link actin under low calcium conditions. However, when intracellular calcium rises (as in the case of a calcium wave), α-Actinin releases actin filaments, thus no longer cross-linking the F-actin filaments (Jayadev et al., 2014; Prebil et al., 2016; Sjöblom et al., 2008). However, further work will be required to establish the exact connections between calcium and actin networks (Veksler and Gov, 2009).

Actin and calcium feedback loop during egg activation

One hypothesis for how actin dynamics are linked to calcium wave initiation is through interaction with mechanosensitive channels such as TRP channels and DEG/ENaC. We recently showed that the Drosophila Trpm channel is required for the initial calcium influx (Hu and Wolfner, 2019), but how Trpm responds to mechanical stimuli remains to be elucidated. There are several models for how these channels are activated. One suggested cue is a direct mechanical stress applied on the plasma membrane, due to physical pressure during ovulation and/or osmotic swelling of the oocyte in the oviducts. While it is possible that the Trpm channel might respond to the stress directly, it is also possible that the mechanical signal is also transduced through the actin cytoskeleton causing the channel to open, enabling an influx of calcium ions (Christensen and Corey, 2007).

We showed here that prior to egg activation, the cortical actin marker Moesin is less concentrated at the posterior end of the oocyte where calcium waves generally initiate and decreases in concentration at the cortex. It is possible that lack of actin rigidity is linked to calcium channel opening: the initial sparse site of actin allows calcium channels to open and leads to calcium influx, which in turn regulates the dynamic changes in actin to form a wavefront following calcium wave. The inter-linked nature of these two pathways suggests a positive feedback loop that facilitates the progression and completion of the waves. This could be achieved as follows: (1) actin disperses and calcium enters the oocyte; (2) this calcium rise causes further actin dispersion through regulation of actin binding proteins; (3) more calcium then enters the activating egg which results in the complete calcium wave and actin reorganization in a wave-like manner. Overall, we propose that in Drosophila egg activation, actin is able to modulate the intracellular calcium rise, and calcium wave in turn regulate the reorganization of actin.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Rafael Fissore for advice on TRP channel inhibitors, Dr. Jan Lammerding and Gregory Fedorchak for equipment and guidance in the microneedle experiments, the Cornell Biotechnology Resource Center for equipment and assistance with imaging, Zoology Imaging Facility and Matt Wayland for assistance with microscopy, Evvia Gonzales for assistance with RNAi experiments and Liza Sarde for manuscript feedback. This work was supported NYSTEM grant CO29155 and NIH grant S10OD018516 for the shared Zeiss LSM880 confocal/multiphoton microscope, and NIH grant R21-HD088744 (to MFW), the University of Cambridge ISSF grant number 097814 (to TTW), Balfour Studentship (AHYA), BBSRC summer studentship and DTP (BWW), and Sir Isaac Newton Trust Research Grant (Ref 18.07ii(c)) to the Imaging Facility, Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge.

(NIH grant to MFW, R21-HD088744), (University of Cambridge ISSF grant to TTW, 097814), (NYSTEM grant CO29155 and NIH grant S10OD018516 to MFW for the shared Zeiss LSM880 confocal/multiphoton microscope), and (Sir Isaac Newton Trust Research Grant, Ref 18.07ii(c), to the Imaging Facility, Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge).

Footnotes

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Becker KA and Hart NH (1999). Reorganization of filamentous actin and myosin-II in zebrafish eggs correlates temporally and spatially with cortical granule exocytosis. Journal of cell science 112 ( Pt 1), 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernitt E, Döbereiner H-G, Gov NS and Yochelis A. (2017). Fronts and waves of actin polymerization in a bistability-based mechanism of circular dorsal ruffles. Nature Communications 8, 15863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernitt E, Koh CG, Gov N and Döbereiner H-G (2015). Dynamics of Actin Waves on Patterned Substrates: A Quantitative Analysis of Circular Dorsal Ruffles. PLoS ONE 10, e0115857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C and Plastino J. (2014). Actin Dynamics, Architecture, and Mechanics in Cell Motility. Physiological Reviews 94, 235–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider T, Anderson K, Ecke M, Müller-Taubenberger A, Schroth-Diez B, Ishikawa-Ankerhold HC and Gerisch G. (2009). The Three-Dimensional Dynamics of Actin Waves, a Model of Cytoskeletal Self-Organization. Biophysical Journal 96, 2888–2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. (1979). Cytochalasin inhibits the rate of elongation of actin filament fragments. The Journal of Cell Biology 83, 657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case LB and Waterman CM (2011). Adhesive F-actin Waves: A Novel Integrin-Mediated Adhesion Complex Coupled to Ventral Actin Polymerization. PLoS ONE 6, e26631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra ES and Higgs HN (2007). The many faces of actin: matching assembly factors with cellular structures. Nature Cell Biology 9, 1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AP and Corey DP (2007). TRP channels in mechanosensation: direct or indirect activation? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8, 510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun JT, Puppo A, Vasilev F, Gragnaniello G, Garante E and Santella L. (2010). The Biphasic Increase of PIP2 in the Fertilized Eggs of Starfish: New Roles in Actin Polymerization and Ca2+ Signaling. PLoS ONE 5, e14100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE, Runnels LW and Strübing C. (2001). The trp ion channel family. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2, 387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA (1987). Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. The Journal of Cell Biology 105, 1473–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgaard K, Raposo AASF, Niccoli T and St Johnston D. (2007). Capu and Spire Assemble a Cytoplasmic Actin??Mesh that Maintains Microtubule Organization in the Drosophila Oocyte. Developmental Cell 13, 539–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick CJ, York-Andersen AH and Weil TT (2016). Imaging Calcium in Drosophila at Egg Activation. Journal of Visualized Experiments 54311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KA, Demsky M, Montague RA, Weymouth N and Kiehart DP (1997). GFP-Moesin Illuminates Actin Cytoskeleton Dynamics in Living Tissue and Demonstrates Cell Shape Changes during Morphogenesis in Drosophila. Developmental Biology 191, 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eno C, Solanki B and Pelegri F. (2016). aura( mid1ip1l) regulates the cytoskeleton at the zebrafish egg-to-embryo transition. Development (Cambridge, England) 143, 1585–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan MD and Lin S. (1980). Cytochalasins block actin filament elongation by binding to high affinity sites associated with F-actin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 255, 835–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, et al. (2015). Phosphoproteomic network analysis in the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus reveals new candidates in egg activation. Proteomics. 15 (23). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart NH and Collins GC (1991). An electron-microscope and freeze-fracture study of the egg cortex of Brachydanio rerio. Cell and Tissue Research 265, 317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz Y, Yu J and Wolfner MF (2001). Ovulation triggers activation of Drosophila oocytes. Developmental Biology 234, 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK (2016). The Cytoskeleton and Its Regulation by Calcium and Protons. Plant Physiol. 170, 3–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KC, Popp D, Gebhard W and Kabsch W. (1990). Atomic model of the actin filament. Nature 347, 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner VL and Wolfner MF (2008). Transitioning from egg to embryo: Triggers and mechanisms of egg activation. Developmental Dynamics 237, 527–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner VL, Czank A, Jang JK, Singh N, Williams BC, Puro J, Kubli E, Hanes SD, Mckim KS, Wolfner MF, et al. (2006). The Drosophila Calcipressin Sarah Is Required for Several Aspects of Egg Activation. Medical Engineering & Physics 16, 1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q and Wolfner MF (2019). The Drosophila Trpm channel mediates calcium influx during egg activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, p.201906967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayadev R, Kuk CY, Low SH and Murata-Hori M. (2014). Calcium sensitivity of α-actinin is required for equatorial actin assembly during cytokinesis. Cell Cycle 11, 1929–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W, Mannherz HG, Suck D, Pai EF and Holmes KC (1990). Atomic structure of the actin: DNase I complex. Nature 347, 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneuchi T, Sartain CV, Takeo S, Horner VL, Buehner NA, Aigaki T and Wolfner MF (2015). Calcium waves occur as Drosophila oocytes activate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, 791–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashir J, Nomikos M, Lai FA and Swann K. (2014). Sperm-induced Ca2+ release during egg activation in mammals. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 450, 1204–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamviwath V, Hu J and Othmer HG (2013). A Continuum Model of Actin Waves in Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS ONE 8, e64272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR (2000). Maize Profilin Isoforms Are Functionally Distinct. THE PLANT CELL ONLINE 12, 583–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauchunas AR, Horner VL, Wolfner M,F (2012). Protein phosphorylation changes reveal new candidates in the regulation of egg activation and early embryogenesis in D. melanogaster. Developmental Biology. 370, 125–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauchunas AR and Wolfner MF (2013). Molecular changes during egg activation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 102, 267–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler J-M and Lasko P. (2014). Localization, anchoring and translational control of oskar, gurken, bicoid and nanos mRNA during Drosophila oogenesis. Fly 3, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyozuka K, Chun JT, Puppo A, Gragnaniello G, Garante E and Santella L. (2008). Actin cytoskeleton modulates calcium signaling during maturation of starfish oocytes. Developmental Biology 320, 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HC, Yoon S-Y, Lykke-Hartmann K, Fissore RA and Carvacho I. (2016). TRPV3 channels mediate Ca²⁺ influx induced by 2-APB in mouse eggs. Cell Calcium 59, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman W, Craig R and Vibert P. (1994). Ca2+-induced tropomyosin movement in Limulus thin filaments revealed by three-dimensional reconstruction. Nature 368, 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DC and Lin S. (1979). Actin polymerization induced by a motility-related high-affinity cytochalasin binding complex from human erythrocyte membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 76, 2345–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean-Fletcher S and Pollard TD (1980). Mechanism of action of cytochalasin B on actin. Cell 20, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald AP, Goralski TJ and Caulton JH (1983). In vitro activation of Drosophila eggs. Dev. Biol. 98, 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T and Mikoshiba K. (1997). 2APB, 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate, a Membrane-Penetrable Modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-Induced Ca2+ Release. Journal of Biochemistry 122, 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y and Williams CJ (2013). Calcium signaling in mammalian egg activation and embryo development: Influence of subcellular localization. Mol Reprod Dev. 79, 742–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S and Hunt T. (2007). Calcineurin is required to release Xenopus egg extracts from meiotic M phase. Nature. 449, 336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AW and Orr-Weaver TL (1997). Activation of the Meiotic Divisions in Drosophila Oocytes. Developmental Biology 183, 195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Pastor C, Rubio-Moscardo F, Vogel-González M, Serra SA, Afthinos A, Mrkonjic S, Destaing O, Abenza JF, Fernández-Fernández JM, Trepat X, et al. (2018). Piezo2 channel regulates RhoA and actin cytoskeleton to promote cell mechanobiological responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, 1925–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prebil SD, Slapšak U, Pavšič M, Ilc G, Puž V, de Almeida Ribeiro E, Anrather D, Hartl M, Backman L, Plavec J, et al. (2016). Structure and calcium-binding studies of calmodulin-like domain of human non-muscle α-actinin-1. Scientific Reports 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presler M, Van Itallie E, Klein AM, Kunz R, Coughlin ML, Peshkin L, Gygi SP, Wuhr M, Kirschner MW (2017). Proteomics of phosphorylation and protein dynamics during fertilization and meiotic exit in the Xenopus egg. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 114, E10838–E47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan ME, Heuser JE, Kerkhoff E and Dyche Mullins R. (2005). Drosophila Spire is an actin nucleation factor. Nature 433, 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, Bista M, Bradke F, Jenne D, Holak TA, Werb Z, et al. (2008). Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. arXiv 5, 605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux MM, Radeke MJ, Goel M, Mushegian A, Foltz KR (2008). 2DE identification of proteins exhibiting turnover and phosphorylation dynamics during sea urchin egg activation. Developmental biology. 313, 630–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartain CV and Wolfner MF (2013). Calcium and egg activation in Drosophila. Cell Calcium 53, 10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell MJ, Erneux C and Irvine RF (2001). Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate 3-Kinase A Associates with F-actin and Dendritic Spines via Its N Terminus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276, 37537–37546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöblom B, Salmazo A and Djinović-Carugo K. (2008). α-Actinin structure and regulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2688–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spracklen AJ, Fagan TN, Lovander KE and Tootle TL (2014a). The pros and cons of common actin labeling tools for visualizing actin dynamics during Drosophila oogenesis. Developmental Biology 393, 209–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spracklen AJ, Kelpsch DJ, Chen X, Spracklen CN and Tootle TL (2014b). Prostaglandins temporally regulate cytoplasmic actin bundle formation during Drosophila oogenesis. MBoC 25, 397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K and Lai FA (2016). Egg Activation at Fertilization by a Soluble Sperm Protein. Physiological Reviews 96, 127–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szent-Györgyi AG (1975). Calcium regulation of muscle contraction. Biophysical Journal 15, 707–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S, Tsuda M, Akahori S, Matsuo T, Aigaki T. (2006). The calcineurin regulator sra plays an essential role in female meiosis in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 16, 1435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S, Hawley RS, Aigaki T. (2010). Calcineurin and its regulation by Sra/RCAN is required for completion of meiosis in Drosophila. Developmental biology. 344, 957–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney LG (1980). Actin, microvilli, and the fertilization cone of sea urchin eggs. The Journal of Cell Biology 87, 771–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tojkander S, Ciuba K and Lappalainen P. (2018). CaMKK2 Regulates Mechanosensitive Assembly of Contractile Actin Stress Fibers. CellReports 24, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Kojima H, Yokota E, Nakamori R, Anson M, Shimmen T and Oiwa K. (2012). Calcium-induced Mechanical Change in the Neck Domain Alters the Activity of Plant Myosin XI. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, 30711–30718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev F, Chun JT, Gragnaniello G, Garante E and Santella L. (2012). Effects of Ionomycin on Egg Activation and Early Development in Starfish. PLoS ONE 7, e39231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veksler A and Gov NS (2009). Calcium-Actin Waves and Oscillations of Cellular Membranes. Biophysical Journal 97, 1558–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidali L and Hepler PK (2001). Actin and pollen tube growth. Protoplasma 215, 64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh TP, Weber A, Davis K, Bonder E and Mooseker M. (1984). Calcium dependence of villin-induced actin depolymerization. Biochemistry 23, 6099–6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y and Riechmann V. (2007). The Role of the Actomyosin Cytoskeleton in Coordination of Tissue Growth during Drosophila Oogenesis. Medical Engineering & Physics 17, 1349–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil TT, Forrest MK, and Gavis ER (2006) Localization of bicoid mRNA in Late Oocytes Is Maintained by Continual Active Transport. Developmental Cell 11, 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil TT, Parton R, Davis I and Gavis ER (2008). Changes in bicoid mRNA Anchoring Highlight Conserved Mechanisms during the Oocyte-to-Embryo Transition. Current Biology 18, 1055–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington A, Emmons S, James B, Calley J, Grover M, Tolias P and Manseau L. (1999). Spire contains actin binding domains and is related to ascidian posterior end mark-5. Development 126, 5267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarmola EG, Somasundaram T, Boring TA, Spector I and Bubb MR (2000). Actin-Latrunculin A Structure and Function: DIFFERENTIAL MODULATION OF ACTIN-BINDING PROTEIN FUNCTION BY LATRUNCULIN A. Journal of Biological Chemistry 275, 28120–28127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York-Andersen AH, Parton RM, Bi CJ, Bromley CL, Davis I and Weil TT (2015). A single and rapid calcium wave at egg activation in Drosophila. Biology open 4, 553–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Ahmed-Braimah Y, Goldberg ML and Wolfner MF (2019). Calcineurin dependent protein phosphorylation changes during egg activation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Proteomics 18, S145–S158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.