1. SUMMARY

An explanation of the principles and mechanisms involved in peaceful co-existence between animals and the huge, diverse, and ever-changing microbiota that resides on their mucosal surfaces represents a challenging puzzle that is fundamental in everyday survival. In addition to mechanical barriers and a variety of innate defense factors, mucosal immunoglobulins (Ig) provide protection by two complementary mechanisms: specific antibody activity and innate, Ig glycan-mediated binding, both of which serve to contain the mucosal microbiota in its physiological niche. Thus, the interaction of bacterial ligands with IgA glycans constitutes a discrete mechanism that is independent of antibody specificity and operates primarily in the intestinal tract. This mucosal site is by far the most heavily colonized with an enormously diverse bacterial population, as well as the most abundant production site for antibodies, predominantly of the IgA isotype, in the entire immune system. In embodying both adaptive and innate immune mechanisms within a single molecule, S-IgA maintains comprehensive protection of mucosal surfaces with economy of structure and function.

Keywords: Secretory IgA, mucosal immunity, glycans, bacterial adherence

2. ROLE OF SECRETORY IgA (S-IgA) IN MUCOSAL IMMUNITY

Large surface areas of mucosal membranes (~200–400 m2) are in constant contact with a highly diverse microbiota [1–6] estimated to comprise ~15,000 – 36,000 species and 1,800 genera [7,8] and exceeding the total number of nucleated cells by an order of magnitude [1, 2, 5, 9] (1013 nucleated cells vs. ~1014 bacterial cells). More than 99.9% of all commensal bacteria are found in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the large intestine [5, 10]. Through evolution, the selective pressure arising from environmental antigens of microbial and food origin has resulted in a strategic, functionally advantageous distribution of cells involved in antigen uptake and processing, and the initiation of immune responses in mucosal tissues [9, 11–13]. The mucosal immune system contains this antigenic onslaught without compromising the integrity of the mucosal barrier [11] or exhausting the immune system, in part through the induction of mucosal (oral) tolerance [14, 15]. In addition to mechanical barriers and humoral effectors of innate immunity [6, 11, 16], mucosal antibodies and mucosal T cells provide antigen-specific protection [12, 17].

The characteristic distribution of antibodies in blood and external secretions, including the intestinal fluid, reflects the functional adaptation of various Ig isotypes to different immune compartments. Given that mucosal membranes are the most important site of antigen encounter, it should not be surprising that most antibody production takes place in mucosal tissues, particularly the intestine, rather than in the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes [12, 18–21], and that the daily synthesis of IgA far exceeds that of IgG, IgM, IgD and IgE combined [19–22]. Importantly for mucosal protection, more than two-thirds of total IgA production ends up in the external secretions [19, 21]. Quantitative studies of the origin of mucosal antibodies, particularly in the intestinal tract, demonstrate that >95% is of local origin and only trace amounts are derived from the circulation [19, 22, 23].

The mucosal microbiota, epithelial cells, and the mucosal immune system constitute a stable and interdependent “tripod” that maintains mucosal homeostasis by complex mechanisms [3, 4, 6, 24–28]. For example, epithelial cells display surface receptors that are selectively exploited by bacteria adhering to their apical surfaces [1, 2, 28–30], and express the basolateral membrane receptor (polymeric Ig receptor; pIgR) that transports locally-produced polymeric (p) IgA into the external secretions [23]. Bacteria endogenous to the intestinal tract, oral cavity, and probably alsp the respiratory and genital tracts, are coated in vivo with S-IgA [9, 13, 17, 31–39] that limits their epithelial adherence and penetration, thereby confining them to the mucosal surfaces. Numerous models have demonstrated the role of antibodies, especially S-IgA, in protecting the intestinal and other mucosal tracts. This has most convincingly been demonstrated in vivo in germ-free, colostrum-deprived newborn piglets [40–42], which, unlike humans, mice, rats, or rabbits, are born without transplacentally acquired Ig. In the absence of maternal as well as endogenous antibodies, milk-deprived piglets die of septicemia (usually E. coli) within 1–2 days after birth, whereas milk-fed animals survive [40]. Furthermore, piglets fed milk or serum, survive oral challenge with E. coli, whereas control animals deprived of Ig, irrespective of its source, succumb to the infection. In mice in which pIgR is copiously expressed on hepatocytes (not the case in humans, pigs, or dogs) and pIgA from the circulation is selectively transported into the bile and thence into the gut lumen [23, 43], pathogen-specific pIgA hybridoma antibodies derived from “backpack tumors” [44–47] protect mice against oral challenge with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Vibrio cholerae, or rotavirus [44, 45, 47–49]. In contrast IgG hybridoma antibodies of the same specificity are not protective, due to the lack of receptor-mediated transport of IgG into the intestine.

Mechanisms of S-IgA-mediated protection

Numerous such experiments clearly demonstrate protection in vivo dependent on the presence of antigen-specific IgA antibodies that interfere with pathogen adherence to or penetration through the mucosal barrier, or neutralize biologically active antigens such as viruses or toxins [41, 47, 48, 50–54]. Likewise many in vitro studies of specific antibody-mediated inhibition of bacterial adherence to epithelial cells corroborate these findings [30, 55–57]. However, agglutination and inhibition of the adherence of E. coli with Type 1 fimbriae to colonic epithelial cells that express a corresponding receptor can be mediated by IgA independently of specific antibody [30, 58, 59]. S-IgA and IgA myeloma proteins of both subclasses agglutinate E. coli, and mannose (Man) inhibits this agglutination. Furthermore, adherence of E. coli to human epithelial colonic cells can be inhibited by S-IgA as well as by IgA2 myeloma proteins. Analysis of the carbohydrate composition and complete primary structure of the oligosaccharide side-chains reveal that the most active pIgA2 myeloma protein contain several Man-rich N-linked glycan chains [30]. Thus, Man-dependent adherence of E. coli to epithelial cell receptors mediated by Type 1 fimbriae is competitively inhibited by similar glycans on S-IgA and IgA2 myeloma proteins acting as decoy receptors. Consequently, we have proposed that IgA proteins exhibit protective functions through antibody-dependent specific immunity as well as glycan-dependent innate immunity [30]. This concept was confirmed in vitro for other microbial ligand-glycan receptors [1, 26, 29, 60–78]. In addition to E. coli, many other bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Clostridium difficile, Shigella flexneri, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and some viruses (Table 1) interact with epithelial receptors via their glycan moiety.

Table 1.

Examples of glycans as adhesion sites and receptors for selected bacteria and viruses that colonize, or infect, mucosal surfaces (adapted from [1, 26, 29, 60–78, 132]).

| Epithelial Cell |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterium | Target Tissue | Glycan Structure | Form |

| Escherichiae with Type 1 fimbriae | intestine | Mana3 [Mana3 (Mana6)] | glycoprotein |

| urinary tract | |||

| P | intestine | Gal(α1,4)Gal | glycoprotein |

| S | intestine | NeuAc(α2,3), Gal(β1,3), GalNAc-O-linked | |

| glycoprotein | |||

| Helicobacter pylori | stomach | NeuAc(α2–3)Gal | glycolipid |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | intestine | Galβ3GlcAc | glycoprotein |

| Fuc | glycoprotein | ||

| Man | glycoprotein | ||

| respiratory tract | GalNAcβ1–4Gal | glycoprotein | |

| Shigella dysenteriae | intestine | asialoGM1 ganglioside | sialoconjugate |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | genital | Gal(β1,4) GalNAc | glycoprotein |

| Bordetella pertussis | respiratory | Gal(β1,4)Glc ceramide | ceramide |

| Haemophilus influenzae | respiratory tract | GlcNAcβ3Gal | glycoprotein |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | respiratory tract | NeuAc(α2–3)-GalβGlcNAc | glycoprotein |

| Virus | |||

| Influenza A, B, C | mucosal tissues | Neu5Ac, Neu5,9Ac2 | sialoconjugates |

| Paramyxoviruses | mucosal tissues | Neu5Ac | sialoconjugates |

| Coronaviruses | mucosal tissues | Neu5, 9Ac2 | sialoconjugates |

| Reo- and rota-viruses | sialic acid | sialoconjugates | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | respiratory mucosal tissues | glycosamine glycans | glycoproteins |

| HIV | epithelial cells | galactosylceramide | |

Man-mannose, Fuc-fucose, Gal-galactose, GlcNAc-N-acetyl glucosamine, GalNAc-N-acetyl galactosamine, NeuAc-sialic acid

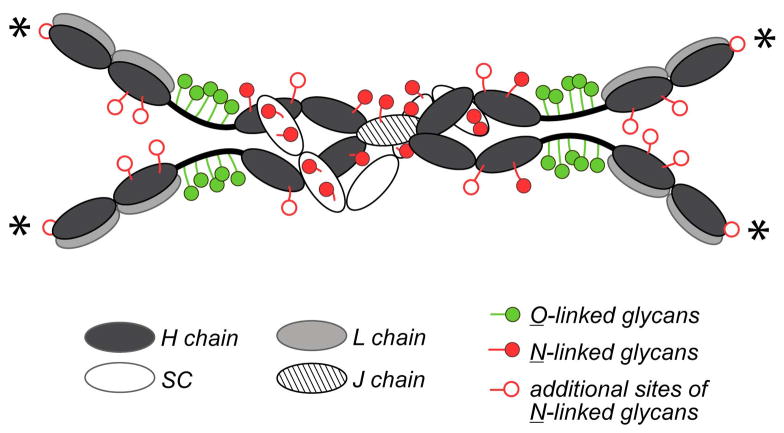

Thus, it has become obvious that the N- and O-glycans of S-IgA provide a link between innate glycan-mediated and adaptive specific antibody-dependent protection (Fig. 1). This concept, of paramount importance in IgA-mediated mucosal defense, prompts additional considerations. First, it has been shown that bacteria indigenous to the oral cavity and intestinal tract are coated in vivo with IgA [9, 17, 31–39, 79–81]. However, it is not known whether this coating depends on specific antibody-antigen or glycan-mediated interactions. Considering the enormous numbers of bacteria (~1012/g of intestinal content) [10], their diversity (~15,000 -36,000 species of 1,800 genera) [7], and the large number of potential antigenic determinants on many bacterial structures, it is unlikely that such coating is based exclusively on specific recognition by S-IgA antibodies. Secondly, in the large intestine IgA2-producing cells are dominant in contrast to other mucosal tissues [82, 83], and antibodies to antigens (e.g., endotoxin) of Gram-negative bacteria are associated predominantly with the S-IgA2 subclass [84–86]. Thirdly, in addition to glycans on the H chain of IgA [87–91], SC is extremely rich in glycans comprising 7 N-linked chains [88, 92–94] that also act as highly effective inhibitors of adherence for some bacterial species (e.g., Shigellae, S. pneumoniae [64, 65, 67–70]). Finally, prevention of the adherence of enormously diverse and variable mucosal microbiota is likely to be at least partially independent of specific antibody activity, reflecting the immediate need for protection against a broad spectrum of daily encountered microorganisms. Thus, in concert with the postulated Fab-mediated “polyreactivity” of S-IgA antibodies [95–100], glycan-mediated interactions are likely to further enforce protective functions of S-IgA.

Figure 1.

Model of a human dimeric S-IgA molecule with assigned adaptive (specific-antibody) activity and innate (glycan-dependent) activity [88]. Asterisk – possible N-glycosylation sites within the CDR3 segment of the VH region of α chains [97, 98, 128].

Skeptics of these concepts may argue that mucosal defenses in IgA-deficient individuals should be significantly compromised. Indeed, the majority of such patients display a higher incidence of respiratory and intestinal infections [101–103]. Currently, IgA deficiency is defined as <50 mg IgA/100 ml of serum, regardless of S-IgA which is not taken into account although it is usually also diminished. Because complete absence of IgA in sera or secretions of IgA-deficient patients is extremely rare, it is possible that even low levels of S-IgA may provide some level of protection. Furthermore, in most IgA-deficient individuals S-IgA is replaced by S-IgM [102–110]. Thus, in IgA-deficient individuals, 65–75% of total Ig-containing cells in the intestines produce IgM, in sharp contrast to normal individuals (in the large intestine, ~90% of cells produce IgA, ~6% IgM, and ~4% IgG) [18, 109]. Most importantly in this context, IgM and IgA display many common structural features, including: ability to form polymers; presence of J chain [111, 112]; ability to bind pIgR (thereby forming SC-containing secretory IgM) [23, 65, 106, 113]; homologies between primary structures of Cμ3, Cμ4 and Cα2, Cα3 domains and the C-terminal “tail-piece” [111, 114, 115]; and VH gene segment representation [116, 117], indicating their close evolutionary and functional similarity [114]. This structural homology also extends to the glycan moieties: IgM and IgA molecules display a similar number and domain location of N-linked glycan side-chains, and both contain Man-rich chains [114, 118–122]. Therefore, despite differences in the number of Ag-binding sites (up to 10 for IgM, and 4–8 for IgA dimers and tetramers), and ability to activate complement, it is clear that IgA and IgM are structurally, functionally, and evolutionarily closely related isotypes.

3. IgA-ASSOCIATED GLYCANS DISPLAY REMARKABLE HETEROGENEITY

Structural studies of human polyclonal S-IgA and monoclonal (myeloma) IgA1 and IgA2 proteins reveal considerable heterogeneity with respect to number, sites of attachment, composition, and primary structure of their glycan side-chains [30, 71–73, 87–94, 115, 122–127], which is likely to be of enormous biological importance. Because different microorganisms interact with epithelial cells through diverse glycan receptors, heterogeneity of IgA-associated glycans affords a variety of structures that can effectively inhibit these interactions.

Glycan moieties in S-IgA molecules are associated with H chains, J chain, and SC [88, 90–94, 124], but Man-rich N-linked glycans that inhibit the binding of Type 1 fimbriae to epithelial receptors occur only on the H chains [30, 122]. However, other bacteria may interact with N- or O-linked glycans on H chains or SC (Table 1, section B). Although the majority of N-linked glycans are found in the Fc region of the α chains [88–89, 114, 115, 124], there is great heterogeneity in the number and composition of individual glycan chains [30, 122] and additional N-linked glycan chains may also be present in the Fd fragment (N-terminal half of the α chain comprising VH and CH1 domains), within the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) [97, 98, 128]. The authors of these novel and functionally important studies propose that a high rate of somatic mutation in the CDR3 taking place within intestinal IgA-producing cells [97, 98, 116, 117, 128, 129] generates a glycosylation-signaling sequence that alters the specificity of intestinal IgA antibodies. Thus, antigen-binding by Fab segments of S-IgA is determined by both specific antibody activity and glycan-dependent interactions.

The heterogeneity of N- and O-linked side chains, with respect to their number, composition, and types of glycosidic bonds is further extended because many of them are incomplete, truncated forms [30, 78, 88, 122]. Most importantly, and in sharp contrast to the combinatorial possibilities of amino acids, glycans can generate a remarkably higher number of structures, due to the variety of glycosidic bonds. Thus, a sequence of six (out of 20) amino acids can theoretically generate 6.4 × 107 distinct hexapeptides, while there are potentially 1.44 × 1015 different hexasaccharides [130].

Specific antibody diversity is generated in an antigen-independent fashion during the differentiation of B lymphocytes by a number of mechanisms including recombination of multiple VJ (for L chains) and VDJ (for H chains) gene segments, combinatorial diversity of L and H chains, somatic hypermutation, gene conversion, and others [131]. The result of these genetic events is the generation of B lymphocytes with surface membrane Ig molecules that accommodate an enormous number of potential antigens, leading, after antigen-specific recognition, to B cell proliferation, differentiation, and the ultimate secretion of large amounts of antigen-specific antibodies. It is conceivable that analogous mechanisms operate in the generation of innate, glycan-mediated mechanisms of protection. Through random generation of enormously diverse glycan structures on mucosal glycoproteins, including S-IgA, S-IgM, SC, mucin, and lactoferrin, glycan configurations are generated that complement the equal heterogeneity of microbial adhesins. The protective effectiveness of these mechanisms may be further enhanced by subsequent somatic mutations within V regions of H and L chains, including the generation of glycosylation signals that lead to alterations of antibody specificities.

Parallel structural and functional exploration of the principles of adaptive (specific antibody) and innate (glycan) S-IgA-mediated immunity is likely to generate novel approaches to the design of broadly protective compounds that work by selectively interfering with the adherence and penetration of pathogens, or that contain the commensal microbiota residing at mucosal surfaces.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants, 5 U19AI028147, the Czech Republic (VZMSM0021620812), DE06746, AI074791, and the John R. Oishei Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abraham SN, Bishop BL, Sharon N, Ofek I. Adhesion of bacteria to mucosal surfaces. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cash HL, Hooper LV. Commensal bacteria shape intestinal immune system development. ASM News. 2005;71:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1058709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savage DG. Mucosal microbiota. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Tuckova L, Mestecky J, Kolinska J, Rossmann P, Stepankova R, et al. Interaction of mucosal microbiota with the innate immune system. Scand J Immunol. 2005;62 (Suppl 1):106–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13780–13785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macpherson AJ, Geuking MB, McCoy KD. Immune responses that adapt the intestinal mucosa to commensal intestinal bacteria. Immunology. 2005;115:153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitman WB, Coleman DC, Wiebe WJ. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6578–6583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer L, Walker WA. Development and physiology of mucosal defense: an introduction. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mestecky J, Blumberg RS, Kiyono H, McGhee JR. The mucosal immune system. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental Immunology. 5. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 2003. pp. 965–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macpherson AJ, Gatto D, Sainsbury E, Harriman GR, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science. 2000;288:2222–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mestecky J, Russell MW, Elson CO. Perspectives on mucosal vaccines: is mucosal tolerance a barrier? J Immunol. 2007;179:5633–5638. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mowat AM, Faria AMC, Weiner HL. Oral tolerance: physiologic basis and clinical applications. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 487–537. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell MW, Bobek LA, Brock JH, Hajishengallis G, Tenovuo J. Innate humoral defense factors. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bos NA, Jiang HQ, Cebra JJ. T cell control of the gut IgA response against commensal bacteria. Gut. 2001;48:762–764. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pabst R, Russell MW, Brandtzaeg P. Tissue distribution of lymphocytes and plasma cells and the role of the gut (letter) Trends Immunol. 2008;29:206–208. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conley ME, Delacroix DL. Intravascular and mucosal immunoglobulin A: Two separate but related systems of immune defense? Ann Int Med. 1987;106:892–899. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-6-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonard PP, Rambaud JC, Dive C, Vaerman JP, Galian A, Delacroix DL. Secretion of immunoglobulins and plasma proteins from the jejunal mucosa. Transport rate and origin of polymeric immunoglobulin A. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:525–535. doi: 10.1172/JCI111450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mestecky J, Russell MW, Jackson S, Brown TA. The human IgA system: a reassessment. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1986;40:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(86)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woof JM, Mestecky J. Mucosal immunoglobulins. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:64–82. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaetzel CS, Mostov K. Immunoglobulin transport and the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 211–250. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corthesy B. Roundtrip ticket for secretory IgA: role in mucosal homeostasis? J Immunol. 2007;178:27–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooper LV. Bacterial contributions to mammalian gut development. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Glycans as legislators of host-microbial interactions: spanning the spectrum from symbiosis to pathogenicity. Glycobiology. 2001;11:1R–10R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.2.1r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ismail AS, Hooper LV. Epithelial cells and their neighbors. IV. Bacterial contributions to intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G779–784. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00203.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orihuela CJ, Fogg G, DiRita VJ, Tuomanen E. Bacterial interactions with mucosal epithelial cells. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 753–767. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adlerberth I, Ahrne S, Johansson ML, Molin G, Hanson LA, Wold AE. A mannose-specific adherence mechanism in Lactobacillus plantarum conferring binding to the human colonic cell line HT-29. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2244–2251. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2244-2251.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wold AE, Mestecky J, Tomana M, Kobata A, Ohbayashi H, Endo T, et al. Secretory immunoglobulin A carries oligosaccharide receptors for Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial lectin. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3073–3077. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3073-3077.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bos NA, Bun JC, Popma SH, Cebra ER, Deenen GJ, van der Cammen MJ, et al. Monoclonal immunoglobulin A derived from peritoneal B cells is encoded by both germ line and somatically mutated VH genes and is reactive with commensal bacteria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:616–623. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.616-623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bos NA, Cebra JJ, Kroese FG. B-1 cells and the intestinal microflora. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;252:211–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-57284-5_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansen GJ, Wilkinson MH, Deddens B, van der Waaij D. Characterization of human faecal flora by means of an improved fluoro-morphometrical method. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:265–272. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroese FG, de Waard R, Bos NA. B-1 cells and their reactivity with the murine intestinal microflora. Semin Immunol. 1996;8:11–18. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ochsenbein AF, Fehr T, Lutz C, Suter M, Brombacher F, Hengartner H, et al. Control of early viral and bacterial distribution and disease by natural antibodies. Science. 1999;286:2156–2159. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shroff KE, Meslin K, Cebra JJ. Commensal enteric bacteria engender a self-limiting humoral mucosal immune response while permanently colonizing the gut. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3904–3913. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3904-3913.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Waaij LA, Kroese FG, Visser A, Nelis GF, Westerveld BD, Jansen PL, et al. Immunoglobulin coating of faecal bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:669–674. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000108346.41221.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Waaij LA, Limburg PC, Mesander G, van der Waaij D. In vivo IgA coating of anaerobic bacteria in human faeces. Gut. 1996;38:348–354. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandtzaeg P, Fjellanger I, Gjeruldsen ST. Adsorption of immunolgobulin A onto oral bacteria in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:242–249. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.1.242-249.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rejnek J, Trávnícek J, Kostka J, Sterzl J, Lanc A. Study of the effect of antibodies in the intestinal tract of germ-free baby pigs. Folia Microbiol. 1968;13:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller I, Cerna J, Travnicek J, Rejnek J, Kruml J. The role of immune pig colostrum, serum and immunoglobulins IgG, IgM, and IgA, in local intestinal immunity against enterotoxic strain in Escherichia coli O55 in germfree piglets. Folia Microbiol. 1975;20:433–438. doi: 10.1007/BF02877048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tlaskalova H, Rejnek J, Travnicek J, Lanc A. The effect of antibodies present in the intestinal tract of germfree piglets on the infection caused by the intravenous administration of the pathogenic strain Escherichia coli 055. Folia Microbiol. 1970;15:372–376. doi: 10.1007/BF02880107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peppard JV, Kaetzel CS, Russell MW. Phylogeny and comparative physiology of IgA. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kraehenbuhl JP, Neutra MR. Monoclonal secretory IgA for protection of the intestinal mucosa against viral and bacterial pathogens. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. Academic Press; San Diego: 1994. pp. 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michetti P, Mahan MJ, Slauch JM, Mekalanos JJ, Neutra MR. Monoclonal secretory immunoglobulin A protects mice against oral challenge with the invasive pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1786–1792. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1786-1792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renegar KB. Passive immunization: systemic and mucosal. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 841–851. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell MW, Kilian M. Biological activities of IgA. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wijburg OL, Uren TK, Simpfendorfer K, Johansen FE, Brandtzaeg P, Strugnell RA. Innate secretory antibodies protect against natural Salmonella typhimurium infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:21–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell MW. Biological functions of IgA. In: Kaetzel CS, editor. Mucosal Immune Defense: Immunoglobulin A. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 144–172. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kilian M, Mestecky J, Russell MW. Defense mechanisms involving Fc-dependent functions of immunoglobulin A and their subversion by bacterial immunoglobulin A proteases. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:296–303. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.2.296-303.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mestecky J, Russell MW. Intestinal immunoglobulin A: role in host defense. In: Hecht G, editor. Microbial Pathogens and the Intestinal Epithelial Cell. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mestecky J, Russell MW, Elson CO. Intestinal IgA: novel views on its function in the defence of the largest mucosal surface. Gut. 1999;44:2–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterson DA, McNulty NP, Guruge JL, Gordon JI. IgA response to symbiotic bacteria as a mediator of gut homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeitlin L, Cone RA, Whaley KJ. Using monoclonal antibodies to prevent mucosal transmission of epidemic infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:54–64. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leffler H, Svanborg Eden C. Chemical identification of a glycosphingolipid receptor for Escherichia coli attaching to human urinary tract epithelial cells and agglutinating human erythrocytes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;24:127. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svanborg-Eden C, Carlsson B, Hanson LA, Jann B, Jann K, Korhonen T, et al. Anti-pili antibodies in breast milk. Lancet. 1979;2:1235. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Svanborg-Eden C, Svennerholm AM. Secretory immunoglobulin A and G antibodies prevent adhesion of Escherichia coli to human urinary tract epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1978;22:790–797. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.3.790-797.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wold A, Mestecky J, Tomana M, Svanborg Eden C. Secretory IgA oligosaccharide chains as receptors for bacterial lectins. In: MacDonald TT, Challacombe SJ, Bland PW, Stokes CR, Heatley RV, Mowat MA, editors. Advances in Mucosal Immunology. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1990. pp. 851–852. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wold AE, Mestecky J, Svanborg Eden C. Agglutination of E. coli by secretory IgA--a result of interaction between bacterial mannose-specific adhesins and immunoglobulin carbohydrate? Monogr Allergy. 1988;24:307–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anthony BF, Concepcion NF, Puentes SM, Payne NR. Nonimmune binding of human immunoglobulin A to type II group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1789–1795. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1789-1795.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davin JC, Senterre J, Mahieu PR. The high lectin-binding capacity of human secretory IgA protects nonspecifically mucosae against environmental antigens. Biol Neonate. 1991;59:121–125. doi: 10.1159/000243333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Firon N, Ofek I, Sharon N. Carbohydrate specificity of the surface lectins of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella typhimurium. Carbohydr Res. 1983;120:235–249. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(83)88019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giugliano LG, Ribeiro ST, Vainstein MH, Ulhoa CJ. Free secretory component and lactoferrin of human milk inhibit the adhesion of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:3–9. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanisch FG, Hacker J, Schroten H. Specificity of S fimbriae on recombinant Escherichia coli: preferential binding to gangliosides expressing NeuAc α (2–3)Gal and NeuAc α (2–8)NeuAc. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2108–2115. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2108-2115.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaetzel CS. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor: bridging innate and adaptive immune responses at mucosal surfaces. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:83–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Korhonen TK, Vaisanen-Rhen V, Rhen M, Pere A, Parkkinen J, Finne J. Escherichia coli fimbriae recognizing sialyl galactosides. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:762–766. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.762-766.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu L, Lamm ME, Li H, Corthesy B, Zhang JR. The human polymeric immunoglobulin receptor binds to Streptococcus pneumoniae via domains 3 and 4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48178–48187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perrier C, Sprenger N, Corthesy B. Glycans on secretory component participate in innate protection against mucosal pathogens. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14280–14287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phalipon A, Cardona A, Kraehenbuhl JP, Edelman L, Sansonetti PJ, Corthesy B. Secretory component: a new role in secretory IgA-mediated immune exclusion in vivo. Immunity. 2002;17:107–115. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phalipon A, Corthesy B. Novel functions for mucosal SIgA. In: Kaetzel CS, editor. Mucosal Immune Defense: Immunoglobulin A. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schroten H, Stapper C, Plogmann R, Kohler H, Hacker J, Hanisch FG. Fab-independent antiadhesion effects of secretory immunoglobulin A on S-fimbriated Escherichia coli are mediated by sialyloligosaccharides. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3971–3973. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3971-3973.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walz A, Odenbreit S, Mahdavi J, Boren T, Ruhl S. Identification and characterization of binding properties of Helicobacter pylori by glycoconjugate arrays. Glycobiology. 2005;15:700–708. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ruhl S, Sandberg AL, Cisar JO. Salivary receptors for the proline-rich protein-binding and lectin-like adhesins of oral actinomyces and streptococci. J Dent Res. 2004;83:505–510. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palmer RJ, Jr, Gordon SM, Cisar JO, Kolenbrander PE. Coaggregation-mediated interactions of streptococci and actinomyces detected in initial human dental plaque. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3400–3409. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3400-3409.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takahashi Y, Ruhl S, Yoon JW, Sandberg AL, Cisar JO. Adhesion of viridans group streptococci to sialic acid-, galactose- and N-acetylgalactosamine-containing receptors. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17:257–262. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2002.170409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takahashi Y, Sandberg AL, Ruhl S, Muller J, Cisar JO. A specific cell surface antigen of Streptococcus gordonii is associated with bacterial hemagglutination and adhesion to alpha2–3-linked sialic acid-containing receptors. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5042–5051. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5042-5051.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cisar JO, Takahashi Y, Ruhl S, Donkersloot JA, Sandberg AL. Specific inhibitors of bacterial adhesion: observations from the study of gram-positive bacteria that initiate biofilm formation on the tooth surface. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:168–175. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110010801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ruhl S, Sandberg AL, Cole MF, Cisar JO. Recognition of immunoglobulin A1 by oral actinomyces and streptococcal lectins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5421–5424. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5421-5424.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Apperloo-Renkema HZ, Wilkinson MH, van der Waaij D. Circulating antibodies against faecal bacteria assessed by immunomorphometry: combining quantitative immunofluorescence and image analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:497–506. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kroese FGM, Kantor AB, Herzenberg LA. The role of B-1 cells in mucosal immune responses. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. Academic Press; San Diego: 1994. pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 81.van der Waaij LA, Mesander G, Limburg PC, van der Waaij D. Direct flow cytometry of anaerobic bacteria in human feces. Cytometry. 1994;16:270–279. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990160312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crago SS, Kutteh WH, Moro I, Allansmith MR, Radl J, Haaijman JJ, et al. Distribution of IgA1-, IgA2-, and J chain-containing cells in human tissues. J Immunol. 1984;132:16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brandtzaeg P, Carlsen HS, Farstad IN. The human mucosal B-cell system. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 617–654. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brown TA, Mestecky J. Immunoglobulin A subclass distribution of naturally occurring salivary antibodies to microbial antigens. Infect Immun. 1985;49:459–462. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.459-462.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brown TA, Mestecky J. Subclass distribution of IgA antibodies to microbial and viral antigens. In: Strober W, Lamm ME, McGhee JR, James SP, editors. Mucosal Immunity and Infections at Mucosal Surfaces. Oxford University Press; New York: 1988. pp. 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ladjeva I, Peterman JH, Mestecky J. IgA subclasses of human colostral antibodies specific for microbial and food antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;78:85–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Novak J, Tomana M, Kilian M, Coward L, Kulhavy R, Barnes S, et al. Heterogeneity of O-glycosylation in the hinge region of human IgA. Molec Immunol. 2001;37:1047–1056. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Royle L, Roos A, Harvey DJ, Wormald MR, van Gijlswijk-Janssen D, Redwan el RM, et al. Secretory IgA N- and O-glycans provide a link between the innate and adaptive immune systems. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20140–20153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Torano A, Tsuzukida Y, Liu YS, Putnam FW. Location and structural significance of the oligosaccharides in human Ig-A1 and IgA2 immunoglobulins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2301–2305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tomana M, Niedermeier W, Mestecky J, Hammack WJ. The moieties of IgA, J chain, secretory piece and IgD. In: Sox HC, editor. Carbohydrate Moieties of Immunoglobulin. MSS Information Corporation; New York: 1974. pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tomana M, Mestecky J, Niedermeier W. Studies on human secretory immunoglobulin A. IV. Carbohydrate composition. J Immunol. 1972;108:1631–1636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hughes GJ, Reason AJ, Savoy L, Jaton J, Frutiger-Hughes S. Carbohydrate moieties in human secretory component. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1434:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mizoguchi A, Mizuochi T, Kobata A. Structures of the carbohydrate moieties of secretory component purified from human milk. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:9612–9621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tomana M, Niedermeier W, Spivey C. Microdetermination of monosaccharides in glycoproteins by gas-liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1978;89:110–118. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bouvet JP, Dighiero G. From natural polyreactive autoantibodies to a la carte monoreactive antibodies to infectious agents: is it a small world after all? Infect Immun. 1998;66:1–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.1-4.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bouvet JP, Fischetti VA. Diversity of antibody-mediated immunity at the mucosal barrier. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2687–2691. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2687-2691.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fernandez C, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Abedi-Valugerdi M, Sverremark E, Cortes V. Polyreactive binding of antibodies generated by polyclonal B cell activation. I. Polyreactivity could be caused by differential glycosylation of immunoglobulins. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:231–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fernandez C, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Sverremark E. Polyreactive binding of antibodies generated by polyclonal B cell activation. II. Crossreactive and monospecific antibodies can be generated from an identical Ig rearrangement by differential glycosylation. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:240–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Quan CP, Berneman A, Pires R, Avrameas S, Bouvet JP. Natural polyreactive secretory immunoglobulin A autoantibodies as a possible barrier to infection in humans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3997–4004. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.3997-4004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shimoda M, Inoue Y, Azuma N, Kanno C. Natural polyreactive immunoglobulin A antibodies produced in mouse Peyer’s patches. Immunology. 1999;97:9–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Burrows PD, Cooper MD. IgA deficiency. Adv Immunol. 1997;65:245–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cunningham-Rundles C. Immunodeficiency and mucosal immunity. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 1145–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mestecky J, Hammarström L. IgA-associated diseases. In: Kaetzel CS, editor. Mucosal Immune Defense: Immunoglobulin A. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 321–344. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arnold RR, Cole MF, Prince S, McGhee JR. Secretory IgM antibodies to Streptococcus mutans in subjects with selective IgA deficiency. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1977;8:475–486. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(77)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Barros MD, Porto MH, Leser PG, Grumach AS, Carneiro-Sampaio MM. Study of colostrum of a patient with selective IgA deficiency. Allergol Immunopathol. 1985;13:331–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brandtzaeg P. Human secretory immunoglobulin M. An immunochemical and immunohistochemical study. Immunology. 1975;29:559–570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brandtzaeg P, Fjellanger I, Gjeruldsen ST. Immunoglobulin M: local synthesis and selective secretion in patients with immunoglobulin A deficiency. Science. 1968;160:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.160.3829.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brandtzaeg P, Karlsson G, Hansson G, Petruson B, Bjorkander J, Hanson LA. The clinical condition of IgA-deficient patients is related to the proportion of IgD- and IgM-producing cells in their nasal mucosa. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;67:626–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Savilahti E. IgA deficiency in children. Immunoglobulin-containing cells in the intestinal mucosa, immunoglobulins in secretions and serum IgA levels. Clin Exp Immunol. 1973;13:395–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Savilahti E, Pelkonen P. Clinical findings and intestinal immunoglobulins in children with partial IgA deficiency. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1979;68:513–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1979.tb05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mestecky J, Moro I, Kerr MA, Woof JM. Mucosal immunoglobulins. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 153–181. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mestecky J, Zikan J, Butler WT. Immunoglobulin M and secretory immunoglobulin A: presence of a common polypeptide chain different from light chains. Science. 1971;171:1163–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3976.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Crago SS, Kulhavy R, Prince SJ, Mestecky J. Secretory component of epithelial cells is a surface receptor for polymeric immunoglobulins. J Exp Med. 1978;147:1832–1837. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.6.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Low TL, Liu YS, Putnam FW. Structure, function, and evolutionary relationships of Fc domains of human immunoglobulins A, G, M, and E. Science. 1976;191:390–392. doi: 10.1126/science.1246619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Putnam FW. Structure of the human IgA subclasses and allotypes. Protides Biol Fluids. 1989;36:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boursier L, Dunn-Walters DK, Spencer J. Characteristics of IgVH genes used by human intestinal plasma cells from childhood. Immunology. 1999;97:558–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fischer M, Kuppers R. Human IgA- and IgM-secreting intestinal plasma cells carry heavily mutated VH region genes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2971–2977. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2971::AID-IMMU2971>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chapman A, Kornfeld R. Structure of the high mannose oligosaccharides of a human IgM myeloma protein. I. The major oligosaccharides of the two high mannose glycopeptides. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:816–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cohen RE, Ballou CE. Linkage and sequence analysis of mannose-rich glycoprotein core oligosaccharides by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4345–4358. doi: 10.1021/bi00559a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jouanneau J, Fournet B, Bourrillon R. Localization and overall structure of a mannose-rich glycopeptide from a pathologic immunoglobulin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;667:277–284. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(81)90193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Monica TJ, Williams SB, Goochee CF, Maiorella BL. Characterization of the glycosylation of a human IgM produced by a human-mouse hybridoma. Glycobiology. 1995;5:175–185. doi: 10.1093/glycob/5.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Endo T, Mestecky J, Kulhavy R, Kobata A. Carbohydrate heterogeneity of human myeloma proteins of the IgA1 and IgA2 subclasses. Mol Immunol. 1994;31:1415–1422. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Field MC, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Rademacher TW, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. Structural analysis of the N-glycans from human immunoglobulin A1: comparison of normal human serum immunoglobulin A1 with that isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem J. 1994;299 (Pt 1):261–275. doi: 10.1042/bj2990261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mattu TS, Pleass RJ, Willis AC, Kilian M, Wormald MR, Lellouch AC, et al. The glycosylation and structure of human serum IgA1, Fab, and Fc regions and the role of N-glycosylation on Fcα receptor interactions. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2260–2272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Renfrow MB, Cooper HJ, Tomana M, Kulhavy R, Hiki Y, Toma K, et al. Determination of aberrant O-glycosylation in the IgA1 hinge region by electron capture dissociation Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19136–19145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Renfrow MB, Mackay CL, Chalmers MJ, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Kilian M, et al. Analysis of O-glycan heterogeneity in IgA1 myeloma proteins by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: implications for IgA nephropathy. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;389:1397–1407. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1500-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tarelli E, Smith AC, Hendry BM, Challacombe SJ, Pouria S. Human serum IgA1 is substituted with up to six O-glycans as shown by matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339:2329–2335. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dunn-Walters D, Boursier L, Spencer J. Effect of somatic hypermutation on potential N-glycosylation sites in human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable regions. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dunn-Walters DK, Spencer J. Strong intrinsic biases towards mutation and conservation of bases in human IgVH genes during somatic hypermutation prevent statistical analysis of antigen selection. Immunology. 1998;95:339–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Weiss AA, Lyer SS. Glycomics aims to interpret the third molecular language of cells. Microbe. 2007;2:489–497. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Max EE. Immunoglobulins: molecular genetics. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental Immunology. 6. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 192–236. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Compans RW, Herrler G. Virus infection of epithelial cells. In: Mestecky J, Bienenstock J, Lamm ME, Mayer L, McGhee JR, Strober W, editors. Mucosal Immunology. 3. Elsevier/Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 769–782. [Google Scholar]