Abstract

Background

Our aims were to: (1) estimate the prevalence of essential tremor (ET) in a community-based study in northern Manhattan, New York, (2) compare prevalence across ethnic groups, and (3) provide prevalence estimates for the oldest old.

Methods

This study did not rely on a screening questionnaire. Rather, as part of an in-person neurological evaluation, each participant produced several handwriting samples, from which ET diagnoses were assigned.

Results

There were 1,965 participants (76.7 ± 6.9 years, range = 66 – 102 years); 108 had ET (5.5%, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.5%–6.5%). Odds of ET were robustly associated with Hispanic ethnicity vs. White ethnicity (odds ratio [OR] = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.03–4.64, p = 0.04) and age (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.03–1.26, p = 0.01)(i.e., with every 1 year advance in age, the odds of ET increased by 14%). Prevalence reached 21.7% among the oldest old (age ≥95 years).

Conclusions

This study reports a significant ethnic difference in the prevalence of ET. The prevalence of ET was high overall (5.5%) and rose markedly with age so that in the oldest old, more than one of five individuals had this disease.

Keywords: essential tremor, epidemiology, prevalence, ethnicity, clinical

Introduction

Essential tremor (ET), a progressive neurological disease, is regarded as one of the most prevalent neurological disorders [1–4]. Yet there are wide disparities in prevalence estimates, with an approximately 3,000-fold difference between the lowest and highest estimates [5], so that prevalence has not been established with precision. A major methodological problem is that, with few exceptions [1,6,7], the more than 20 prevalence studies have relied on screening questionnaires, which generally have low sensitivity.

Age is a well-established risk factor for ET [8,9], yet little is known about other key disease determinants. For example, there are few direct comparisons between persons of different ethnicity [10–12], so that the role of ethnicity as a disease determinant has not been examined in detail. Even with regard to age, with a rare exception [6], studies have not reported data on prevalence among persons aged 90 and older, so that it is not clear whether prevalence continues to rise or declines towards the end of the age spectrum.

We assessed the prevalence of ET in a large community-based health survey of persons 65 years and older (range = 65–102 years) living in northern Manhattan, New York. We assessed participants independent of screening results in order to obtain a more complete estimate of ET prevalence. The multi-ethnic nature of this sample further allowed for direct comparisons of ET prevalence across these ethnic groups.

Methods

Study sample

2,776 individuals participated in a prospective study of aging and dementia in Medicare-eligible northern Manhattan residents, age ≥65 years (Washington/Hamilton Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project: WHICAP II). The WHICAP II cohort represents a combination of continuing members of a cohort originally recruited in 1992 (WHICAP I; n = 602) and members of a new cohort recruited between 1999 and 2001 (n = 2,174). The sampling strategies have been described in detail [13]. Prevalence was previously estimated in a larger sample of members recruited in 1992 [10]; therefore, the current analyses were restricted to the baseline assessment of the new cohort recruited between 1999 and 2001 (n = 2,174). Informed consent and study procedures were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

In Person Evaluation

A trained research assistant collected demographic information (including self-reported race, which was coded as non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic African-American, and Other) and administered a structured interview of health, which included questions on current and past medical conditions and current medication use. The structured interview also included the questions “do your arms or legs shake?”, “have you ever been told that you have Parkinson’s disease?”, and “have you ever taken levodopa or Sinemet?” Names and dosages of all current medications were collected.

Each participant also underwent a standardized neurological examination by a general physician. The physician was not asked to comment on or rate action tremor but performed an abbreviated (ten-item) version of the motor portion of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)[14], and assigned a preliminary diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) based on the presence of two or more cardinal signs. Using the same criteria, PD diagnoses were then confirmed by a study neurologist based on a second, more-detailed neurological examination.

As noted above, examining physicians were not asked to rate action tremor. Hence, ET diagnoses were assigned at a later point based on handwriting samples. As part of their evaluation, each participant was asked to generate two handwriting samples. The first set of handwriting samples was administered as part of a neuropsychological test battery. It was comprised of a series of five standard shapes (a triangle, a diamond, a triangle overlapping a square, a series of lines at different angles, and a cube) that had to be copied [15], and a trail making test in which the participant was asked to draw a series of lines connecting numbered circles [16]. A second handwriting sample was collected as part of a literacy test (10–60 minutes after the first sample); the participant was asked to copy a standardized hand-written sentence, “I have a calendar in my room” onto a sheet of paper.

Rating Handwriting Samples

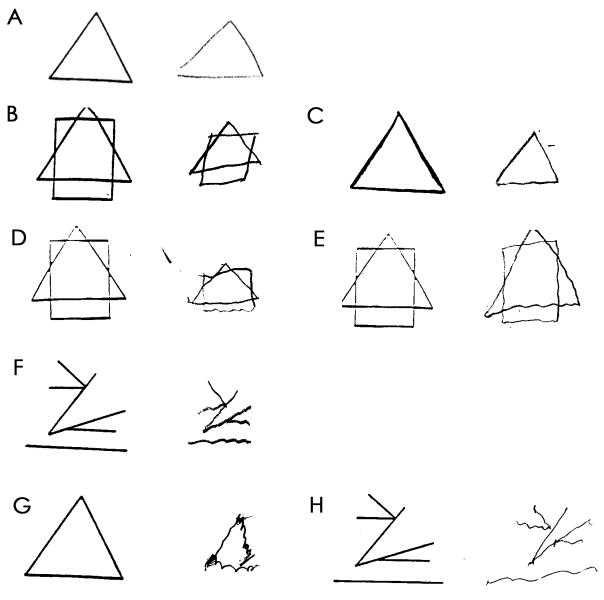

A medical student (S.T.) was trained by a senior neurologist specializing in tremor disorders (E.D.L.) to rate the severity of tremor in the five shapes and the trail making test. Tremor was rated from 0–2 in each of the six items. The ratings were: 0 (no tremor), 0.5 (possible tremor), 1.0 (clear tremor that was mild, equivalent to a rating of 2 on an Archimedes spiral in the rating scale of Bain and Findley[17]), 1.5 (mild to moderate tremor, equivalent to a rating of 3 – 4 in Bain and Findley[17]), 2 (moderate or greater tremor, equivalent to a rating ≥5 in Bain and Findley[17])(Figure 1). Based on the six rated items, a total tremor score was generated for each participant (range = 0–12). After training was completed, agreement between the medical student and senior neurologist was assessed using handwriting samples from 25 participants, and agreement was substantial (for total tremor score, intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.80). The student then began to review the research records of each participant, rating tremor. During the course of these ratings, which required three months, every 40th sample (i.e., 2.5% of all samples) was selected for independent rating by the student and the senior neurologist to ensure that agreement remained high. For these ratings, the intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.71.

Figure 1.

Examples of drawings with tremor ratings of 0 (A), 0.5 (B and C), 1.0 (D and E), 1.5 (F), and 2 (G and H). For each example (A–H), the pre-printed sample is on left and hand-drawn copy by the study participant is on the right.

ET Diagnosis

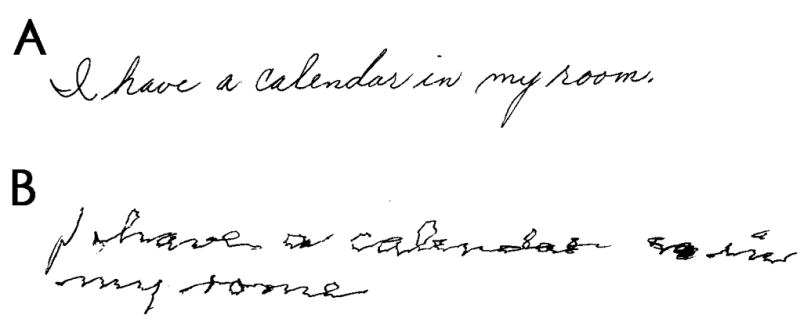

Bain and Findley[17] suggested that their tremor rating ≥2 be used to distinguish ET from enhanced physiological tremor because this rating corresponded with twice that of the 95th percentile seen in healthy controls. As noted above, their rating of 2 is the visual equivalent to our rating of 1.0. A tremor rating of 1.0 on each of our six rated items would result in a total tremor score of 6.0. To be more inclusive (i.e., accounting for the possibility that one of the 6 items could have received a rating of 0.5), we considered those with a total tremor score of 5.5 or higher as having a preliminary diagnosis of ET and these participants were selected for further consideration. The senior neurologist reviewed their records, re-rating tremor and assigning a total tremor score. As an additional test, the handwritten sentence was rated by the senior neurologist using published guidelines of Bain and Findley[17], with any Bain and Findley rating ≥2, being considered consistent with ET. A final diagnosis of ET was assigned when the senior neurologist confirmed a total tremor score of 5.5 or higher or rated the handwritten sentence ≥2 (Figure 2). Participants were not assigned a final diagnosis of ET if they were diagnosed with PD, were ever told they had PD, had used levodopa at any point in their lives, or if the tremor was related to another neurological disorder. Subsequently, nine of the ET cases were randomly selected for enrollment in an epidemiological study of ET [18] and each had a complete videotaped tremor examination (sustained arm extension, pouring, drinking, using a spoon, finger-nose-finger maneuver, and writing); the diagnosis of ET was confirmed in 100% of these based on published research criteria (moderate or greater amplitude tremor during three activities or a head tremor in the absence of PD, dystonia or another neurological disorder)[18].

Figure 2.

Example of handwritten sentences with ratings of 0 (A) and 2 (B).

Final Sample

Complete data were available on 1,965 (90.4%) of 2,174 participants. The remaining 209 participants refused the writing tasks due to poor eye sight or difficulty following the instructions. In one instance, a participant completed the drawings but not the written sentence; this was because tremor made writing difficult.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square (x2) tests were used to compare proportions. We calculated point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Overall frequency was provided as a crude estimate and adjusted estimates (2000 United States Census, age ≥65)[19].

Results

The mean ± SD age of the final sample of 1,965 participants was 76.7 ± 6.9 years (range = 66–102); 1,306 (66.5%) were women. Ethnicity was 589 (30.0%) non-Hispanic White, 642 (32.7%) non-Hispanic African-American, 702 (35.7%) Hispanic, and 32 (1.6%) Other. Mean education was 10.4 ± 4.8 years. Forty (2.1%) of 1,965 were diagnosed with PD or previously had been told they had PD or had used levodopa at any point in their lives.

One-hundred-forty-two (7.2%) of 1,965 participants were assigned a preliminary diagnosis of ET, but 13 were excluded because they were diagnosed with PD or had been told they had PD or had used levodopa at any point in their lives, leaving 129 (6.6% of 1,965) participants with a preliminary diagnosis of ET. A final diagnosis of ET was assigned to 108 of 1,965 participants (crude prevalence = 5.5%, 95% CI = 4.5%–6.5%). After age-adjustment to the 2000 United States Census, the estimated prevalence in the United States population (age ≥65 years) was 5.0%, 95% CI = 4.0% –6.0%, and after similar adjustment for Hispanic status, prevalence was 4.9%, 95% CI = 4.0% – 5.9%. Thirty-four (31.5%) of 108 had answered “yes” to the question “do your arms or legs shake?”

The prevalence of ET was similar by gender. It was higher in African-Americans and Hispanics than Whites and increased with age, reaching 21.7% among the oldest old (age ≥95 years)(Table 1). The prevalence of ET is shown within strata defined by ethnicity and age (Table 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of ET by Gender, Ethnicity, and Age Stratum

| Number of ET cases/Number of Participants | Crude Prevalence Per 100 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 38/659 | 5.8 (3.9–7.5) |

| Women | 70/1,306 | 5.4 (4.1–6.5) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 18/589 | 3.1 (1.6–4.4) |

| Non-Hispanic African-American | 38/642 | 5.9 (4.1–7.7) |

| Hispanic | 51/702 | 7.3 (5.3–9.1) |

| Other | 1/32 | 3.1 (0.0–8.1) |

|

| ||

| Age (10 Year Strata) | ||

| 65–74 | 22/868 | 2.5 (1.5–3.5) |

| 75–84 | 55/812 | 6.8 (5.0–8.4) |

| 85–94 | 26/262 | 9.9 (6.3–13.5) |

| 95 and older | 5/23 | 21.7 (4.4–37.7) |

For gender, x2 = 0.14, p = 0.71.

For ethnicity, x2 = 11.55, p = 0.009. (For White vs. African-American, x2 = 5.80, p = 0.016; for White vs. Hispanic, x2 = 11.22, p = 0.001; for Hispanic vs. African-American, x2 = 0.98, p = 0.32).

For age (10 year strata), x2 = 38.78, p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Prevalence of ET Within Strata Defined by Ethnicity and Age

| 65–74 Years | 75–84 Years | 85 Years and Older | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | 5/249 (2.0, 0.3–3.7) | 10/229 (4.4, 1.7–6.9) | 3/111 (2.7, 0.0–5.7) |

| Non-Hispanic African- American | 5/270 (1.9, 0.2–3.4) | 17/271 (6.3, 3.3–9.1) | 16/101 (15.8, 8.0–22.0) |

| Hispanic | 12/336 (3.6, 1.5–5.5) | 27/298 (9.1, 5.8–12.3) | 12/68 (17.6, 8.1–25.9) |

| Other | 0/13 (0.0) | 1/13 (7.7, 0–22.0) | 0/5 (0.0) |

Values are number of ET cases/number of participants (percent, 95% CI).

In a logistic regression analysis that included age, gender and ethnicity, the odds of ET (dependent variable) were associated with age (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.03–1.26, p = 0.01)(i.e., with every one year advance in age, the odds of ET increased by 14%) and Hispanic vs. White ethnicity (OR = 2.19, 95% CI = 1.03–4.64, p = 0.04) but not with female gender (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.58–1.96, p = 0.83) or African American vs. White ethnicity (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 0.66–3.37, p = 0.33).

It is conceivable that handwriting tremor could have been the result of other medical co-morbidities (esp., thyroid disease, stroke, arthritis) or tremor-producing medications. However, these medical co-morbidities were no more common in our ET cases than other participants. Similarly, the current use of a variety of tremor-producing medications (e.g., thyroid supplements, steroids, estrogen replacement therapy, insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, antidepressants) did not differ in ET cases vs. other participants. These data suggest that medical comorbidity and medications were not likely to have been the cause of tremor.

Discussion

The prevalence of ET was high (5.5%) and rose markedly with age. In the oldest old, more than one in five individuals had ET. This study did not rely on a screening questionnaire, as was a design feature in three prior prevalence studies [1,6,7]. In a study in Italy, the crude prevalence of ET was 97/4,573 (2.1%) in persons aged ≥61 years [6]. The low estimate was likely due to the fact that the initial examination was performed by general family practitioners rather than neurologists specializing in movement disorders [6]. A study of Arabic villagers in Israel aged ≥65 years also reported a low crude prevalence of 8/424 (1.9%), leading the investigators to query whether the prevalence might be particularly low in that ethnic group [7]. Dogu et al. [1] studied tremor in Mersin Turkey. Each participant was examined by a study neurologist and the authors used the same standardized examination and diagnostic criteria as Inzelberg et al.[7], reporting a crude prevalence of ET (age ≥60 years) of 39/622 (6.3%). Our results (prevalence in age ≥65 years = 5.5%) lie between those of previous studies [1,6,7], yet closer to those of Dogu et al.[1]

Ethnic differences, if present in ET, could reflect differences in the prevalence of susceptibility genotypes; they could also reflect differences in exposure to environmental factors that have been associated with ET [20]. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of ET have received only modest attention. Tan et al.[12] studied the prevalence of ET in a community-based survey in Singapore, comparing Singaporean Chinese, Malays, and Indians. The prevalence was marginally higher in Indians than Chinese (p = 0.08). No Malays with ET were identified. Inzelberg et al.[7] reported a very low prevalence among Arabic villagers in Israel; however, there was no formal comparison with other ethnic groups in Israel. In a study in Copiah county, Mississippi, there was a nonsignificant trend for ET to be higher among whites than African-Americans, although it is important to note that the study relied on an initial screening questionnaire, which could have biased results toward lower prevalence among less educated participants [11]. Similarly, an earlier study in northern Manhattan that analyzed data on 2,117 persons aged ≥65 years recruited in 1992 (WHICAP I), reported a non-significant trend towards higher prevalence in whites than African-Americans; however, that study also relied on an initial screening questionnaire [10]. By contrast, the current study, which did not rely on an initial screening questionnaire, reports a significant ethnic difference in the prevalence of ET, with the prevalence among whites being the lowest. Clearly, ethnic differences in ET require further study.

As reported previously [1,5,21,22], the prevalence of ET increased with age. This is one feature of the disease that has been used to support the notion that it is degenerative. Recent postmortem studies report degenerative type changes in the ET brain, including Purkinje cell loss [23–25]. Of additional interest is that prevalence of ET continued to rise in the oldest age groups. Prior studies of ET generally have not reported separate prevalence estimates for persons aged 90 and older. Other than our study, Mancini et al. [6] similarly reported that prevalence continued to rise in persons age 90 and older. There is a mixed literature in other late life degenerative disorders (e.g., PD), with many demonstrating a continued increase with advancing age [26] while others suggest a reduction in incidence or prevalence in the oldest old [27,28].

Approximately one-half of our ET cases did not report tremor. Previous work in community-based studies, in which ET cases often have mild tremor, has similarly demonstrated a high proportion of cases who do not report tremor (e.g., 28%.3[10], 31.3%[8], and 50.0%[29]).

As noted above, in WHICAP I (1992), we estimated the prevalence of ET in an earlier, different sample of persons living in the same neighborhoods in northern Manhattan [10]. Aside from being a completely different sample from the one reported here, the earlier study used a different method for ascertaining ET cases (based on a screening questionnaire) and handwriting samples were not routinely analyzed as we did here. Hence, the earlier estimate of crude prevalence, 3.9%, was lower than that reported here.

This study had limitations. First, ET was diagnosed based on handwriting. It is possible that we under-ascertained cases whose tremor manifested only during tasks other than writing. Thus, the results reported in this paper may be a conservative estimate of prevalence. In a previous population-based study of ET, we observed that 15.5% of ET cases had no tremor while drawing one spiral with their dominant arm [30]. Similarly, Dogu et al. [31] observed this value to be 12.4%. However, in the current study, we used multiple different writing tasks/samples so that this proportion is likely to have been far lower. Even if the actual prevalence were 15% higher, it would have been similar to our estimate (6.3% rather than 5.5%). On the other hand, we may also have included some cases of primary writing tremor [32]; however, this entity is rare [33] (by one estimate its prevalence was 1/200th that of ET)[34] and this would not have been a major source of misclassification. Second, we did not assess head tremor. However, previous ET series indicate that isolated head tremor cases comprise a small proportion of ET cases (e.g., 0.0%[35], 0.0%[7], 1.6%[21], 2.0%[34], 3.2%[36]) so that this was not likely to have been a major source of underestimation. Third, we could not estimate prevalence in younger individuals. Fourth, family history data were not routinely collected so that we could not assess ethnic differences in familial tremor. Finally, although it is conceivable that we failed to ascertain tremor in individuals with severe ET who could not perform the writing tasks, our data indicate that no participants fell into this category.

This study had several strengths. First, it was population-based rather than clinic-based. Second, as in relatively few other studies [1,6,7], our prevalence estimate was based on direct evaluation of each participant rather than a screening questionnaire. Such screens are known to have low sensitivities [21,37]. Third, few prior studies have reported separate prevalence estimates for persons aged 90 and older [6]; we were able to address whether and to what extent the prevalence rose in the oldest old. Finally, with few other exceptions [11,12], the Washington-Heights population is the only one in which ethnic differences in the prevalence of this common disorder have been directly assessed.

Acknowledgments

P01 AG07232 and R01 NS39422 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dogu O, Sevim S, Camdeviren H, Sasmaz T, Bugdayci R, Aral M, Kaleagasi H, Un S, Louis ED. Prevalence of essential tremor: Door-to-door neurologic exams in Mersin province, Turkey. Neurology. 2003;61:1804–1806. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000099075.19951.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benito-Leon J, Louis ED. Essential tremor: Emerging views of a common disorder. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:666–678. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moghal S, Rajput AH, Meleth R, D’Arcy C, Rajput R. Prevalence of movement disorders in institutionalized elderly. Neuroepidemiology. 1995;14:297–300. doi: 10.1159/000109805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moghal S, Rajput AH, D’Arcy C, Rajput R. Prevalence of movement disorders in elderly community residents. Neuroepidemiology. 1994;13:175–178. doi: 10.1159/000110376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis ED, Ottman R, Hauser WA. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Estimates of the prevalence of essential tremor throughout the world. Mov Disord. 1998;13:5–10. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancini ML, Stracci F, Tambasco N, Sarchielli P, Rossi A, Calabresi P. Prevalence of essential tremor in the territory of Lake Trasimeno, Italy: Results of a population-based study. Mov Disord. 2007;22:540–545. doi: 10.1002/mds.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inzelberg R, Mazarib A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Strugatsky R, Friedland RF. Essential tremor prevalence is low in Arabic villages in Israel: Door-to-door neurological examinations. J Neurol. 2006;253:1557–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benito-Leon J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Louis ED. Incidence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Neurology. 2005;64:1721–1725. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161852.70374.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajput AH, Offord KP, Beard CM, Kurland LT. Essential tremor in Rochester, Minnesota: A 45-year study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:466–470. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.47.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis ED, Marder K, Cote L, Pullman S, Ford B, Wilder D, Tang MX, Lantigua R, Gurland B, Mayeux R. Differences in the prevalence of essential tremor among elderly African Americans, whites, and Hispanics in northern Manhattan, NY. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:1201–1205. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540360079019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haerer AF, Anderson DW, Schoenberg BS. Prevalence of essential tremor. Results from the Copiah county study. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:750–751. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510240012003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan LC, Venketasubramanian N, Ramasamy V, Gao W, Saw SM. Prevalence of essential tremor in Singapore: A study on three races in an asian country. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Merchant C, Lantigua R, Costa R, Stern Y, Mayeux R. Incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in African-Americans, caribbean Hispanics and caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis ED, Schupf N, Manly J, Marder K, Tang MX, Mayeux R. Association between mild parkinsonian signs and mild cognitive impairment in a community. Neurology. 2005;64:1157–1161. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156157.97411.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen W. The Rosen drawing test. Bronx, New York: Veterans Administration Medical Center; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenlief CL, Margolis RB, Erker GJ. Application of the trail making test in differentiating neuropsychological impairment of elderly persons. Percept Mot Skills. 1985;61:1283–1289. doi: 10.2466/pms.1985.61.3f.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bain P, Findley LJ. Assessing tremor severity. London: Smith-Gordon; 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis ED, Zheng W, Jurewicz EC, Watner D, Chen J, Factor-Litvak P, Parides M. Elevation of blood beta-carboline alkaloids in essential tremor. Neurology. 2002;59:1940–1944. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038385.60538.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Commerce. 2000 census of population and housing. Profiles of general demographic characteristics. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louis ED. Environmental epidemiology of essential tremor. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:139–149. doi: 10.1159/000151523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benito-Leon J, Bermejo-Pareja F, Morales JM, Vega S, Molina JA. Prevalence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Mov Disord. 2003;18:389–394. doi: 10.1002/mds.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergareche A, De La Puente E, Lopez De Munain A, Sarasqueta C, De Arce A, Poza JJ, Marti-Masso JF. Prevalence of essential tremor: A door-to-door survey in Bidasoa, Spain. Neuroepidemiology. 2001;20:125–128. doi: 10.1159/000054771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axelrad JE, Louis ED, Honig LS, Flores I, Ross GW, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP. Reduced Purkinje cell number in essential tremor: A postmortem study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:101–107. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shill HA, Adler CH, Sabbagh MN, Connor DJ, Caviness JN, Hentz JG, Beach TG. Pathologic findings in prospectively ascertained essential tremor subjects. Neurology. 2008;70:1452–1455. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310425.76205.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis ED, Faust PL, Vonsattel JP, Honig LS, Rajput A, Robinson CA, Pahwa R, Lyons KE, Ross GW, Borden S, Moskowitz CB, Lawton A, Hernandez N. Neuropathological changes in essential tremor: 33 cases compared with 21 controls. Brain. 2007;130:3297–3307. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Rijk MC, Tzourio C, Breteler MM, Dartigues JF, Amaducci L, Lopez-Pousa S, Manubens-Bertran JM, Alperovitch A, Rocca WA. Prevalence of parkinsonism and parkinson’s disease in Europe: The Europarkinson collaborative study. European community concerted action on the epidemiology of parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:10–15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajput AH, Offord KP, Beard CM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of parkinsonism: Incidence, classification, and mortality. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:278–282. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgante L, Rocca WA, Di Rosa AE, De Domenico P, Grigoletto F, Meneghini F, Reggio A, Savettieri G, Castiglione MG, Patti F, et al. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and other types of parkinsonism: A door-to-door survey in three sicilian municipalities. The Sicilian Neuro-Epidemiologic Study (SNES) group. Neurology. 1992;42:1901–1907. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.10.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louis ED, Ford B, Wendt KJ, Ottman R. Validity of family history data on essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1999;14:456–461. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<456::aid-mds1011>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louis ED, Ford B, Wendt KJ, Lee H, Andrews H. A comparison of different bedside tests for essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1999;14:462–467. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<462::aid-mds1012>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dogu O, Louis ED, Sevim S, Kaleagasi H, Aral M. Clinical characteristics of essential tremor in Mersin, Turkey--a population-based door-to-door study. J Neurol. 2005;252:570–574. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klawans HL, Glantz R, Tanner CM, Goetz CG. Primary writing tremor: A selective action tremor. Neurology. 1982;32:203–206. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer C, Papapetropoulos S, Spielholz NI. Primary writing tremor: Report of a case successfully treated with botulinum toxin a injections and discussion of underlying mechanism. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1387–1388. doi: 10.1002/mds.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinelli P, Gabellini AS, Gulli MR, Lugaresi E. Different clinical features of essential tremor: A 200-patient study. Acta Neurol Scand. 1987;75:106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1987.tb07903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bain PG, Findley LJ, Thompson PD, Gresty MA, Rothwell JC, Harding AE, Marsden CD. A study of hereditary essential tremor. Brain. 1994;117 ( Pt 4):805–824. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salemi G, Aridon P, Calagna G, Monte M, Savettieri G. Population-based case-control study of essential tremor. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1998;19:301–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00713856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louis ED, Ford B, Pullman SL. Prevalence of asymptomatic tremor in relatives of patients with essential tremor. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:197–200. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550140069014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]