Abstract

In inner ear hair cells, activation of mechotransduction channels is followed by extremely rapid deactivation that depends on the influx of Ca2+ through these channels. Although the molecular mechanisms of this “fast” adaptation are largely unknown, the predominant models assume Ca2+ sensitivity as an intrinsic property of yet unidentified mechanotransduction channels. Here we examined mechanotransduction in the hair cells of young postnatal shaker 2 mice (Myo15sh2/sh2). These mice have no functional myosin-XVa, which is critical for normal growth of mechanosensory stereocilia of hair cells. Although stereocilia of both inner and outer hair cells of Myo15sh2/sh2 mice lack myosin-XVa and are abnormally short, these cells have dramatically different hair bundle morphology. Myo15sh2/sh2 outer hair cells retain a “staircase” arrangement of the abnormally short stereocilia and prominent tip links. Myo15sh2/sh2 inner hair cells do not have obliquely oriented tip links and their mechanosensitivity is mediated exclusively by “top-to-top” links between equally short stereocilia. In both inner and outer hair cells of Myo15sh2/sh2 mice, we found mechanotransduction responses with a normal “wild type” amplitude and speed of activation. Surprisingly, only outer hair cells exhibit fast adaptation and sensitivity to extracellular Ca2+. In Myo15sh2/sh2 inner hair cells, fast adaptation is disrupted and the transduction current is insensitive to extracellular Ca2+. We conclude that the Ca2+-sensitivity of the mechanotransduction channels and the fast adaptation require a structural environment that is dependent on myosin-XVa and is disrupted in Myo15sh2/sh2 inner hair cells, but not in Myo15sh2/sh2 outer hair cells.

Keywords: hearing, mechano-electrical transduction, cochlea, shaker 2, non-syndromic deafness, DFNB3

Introduction

Mechano-electrical transduction (MET) in inner ear hair cells is initiated by deflection of stereocilia, the microvilli-like cellular projections that are arranged in rows of graded heights (Corey and Hudspeth, 1979). Current models postulate that yet unidentified MET channels are mechanically gated by the tension of tip links, the extracellular filaments connecting the tops of the shorter stereocilia and the adjacent taller stereocilia (Pickles et al., 1984). Following activation, Ca2+ influx through these non-selective cation channels initiates the adaptation processes that deactivate MET channels on both fast and slow time scales (Wu et al., 1999; Holt and Corey, 2000). “Slow” adaptation has been linked to the motor activity of unconventional myosin-Ic (Holt et al., 2002), although myosin-VIIa may also participate (Kros et al., 2002). The myosin-based adaptation motor is thought to move the upper end of a tip link along the actin core of a stereocilium resetting link tension and resulting in slow adaptation (Howard and Hudspeth, 1987; Hacohen et al., 1989; Assad and Corey, 1992).

The ATPase cycle of any myosin might be too long to account for “fast” adaptation that occurs on sub-millisecond timescales (Fettiplace and Hackney, 2006). According to one model, fast adaptation occurs when Ca2+ ions enter the cell and close the MET channel by binding to or near the channel (Howard and Hudspeth, 1988; Crawford et al., 1991). According to an alternative hypothesis, Ca2+ binds to some intracellular structural element(s) in series with the MET channel, causing decrease of the tension applied to the channel and its inactivation (Bozovic and Hudspeth, 2003; Martin et al., 2003). There is evidence that myosin-Ic mediates fast adaptation in vestibular hair cells, providing “tension release” by a quick conformational change (Stauffer et al., 2005). It is still unknown whether myosin-Ic is essential for orders of magnitude faster adaptation in mammalian auditory hair cells (Kennedy et al., 2003; Ricci et al., 2005).

Myosin-XVa is localized at the tip of every stereocilium in mammalian hair cells (Belyantseva et al., 2003). In shaker 2 mice (Myo15sh2), a recessive mutation in the motor domain prevents translocation of myosin-XVa to the stereocilia tips (Belyantseva et al., 2003; Belyantseva et al., 2005), resulting in abnormally short stereocilia (Probst et al., 1998) and profound deafness (Liang et al., 1998; Nal et al., 2007). In young postnatal homozygous Myo15sh2/sh2 mice, auditory hair cells are still mechanosensitive despite stereocilia length abnormalities (Stepanyan et al., 2006). Here we demonstrate that the absence of myosin-XVa in Myo15sh2/sh2 stereocilia disrupts fast adaptation and Ca2+-sensitivity of the mechanotransducer in cochlear inner hair cells (IHCs) but not in outer hair cells (OHCs). Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs do not have “classical” tip links and their mechanosensitivity is mediated by “top-to-top” links between equally short stereocilia, while Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs have a still prominent “staircase” arrangement of the stereocilia and obliquely oriented tip links. We propose that Ca2+-dependent deactivation of the mechanotransducer requires proper positioning and/or oblique orientation of the tip links, which are both disrupted in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs but not in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs.

Materials and Methods

Organ of Corti explants

Organ of Corti explants were dissected at postnatal days 1-4 (P1-4), placed in glass-bottom Petri dishes (WillCo Wells, Amsterdam, Netherlands), and cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES and 7% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C and 5% CO2 as described previously (Russell et al., 1986; Russell and Richardson, 1987; Stepanyan et al., 2006). Briefly, the sensory epithelium was separated first from the lateral wall and then from modiolus. The most basal “hook” region was cut out and the remaining two turns were uncoiled and placed into the Petri dish to form a circle. The hair cells located approximately at the middle of the explant were used for experiments. The organ of Corti explants were kept in vitro from one to six days before the experiments. The equivalent age (age of dissection + days in vitro) of the specimens reported in this study was P3-9. In some experiments, 10 μg/ml of ampicillin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) was added to the medium with no observed effects on MET currents. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Kentucky Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mouse genotyping

We mate a homozygous mutant male to a heterozygous female. This produces ∼1:1 ratio of normal to mutant phenotypes. In parallel with organ of Corti dissections, we dissect sensory epithelium from ampula, fix it in 4% paraformaldehyde in HBSS for 2 hours, and stain with rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to visualize F-actin of stereocilia. Normal and mutant phenotypes are easily distinguishable by observing rhodamine-stained bundles of vestibular hair cells with epifluorescent illumination. This procedure is relatively fast and provides a phenotypic determination of genotypes by the time cultured epithelia are ready for experiments. For definitive genotyping, tail snip samples were extracted from mouse pups and genomic DNA was purified using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and eluted in 200 μl. PCR was performed using LA Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Mirus Bio, Madison, WI). Primers and PCR conditions were described previously (Belyantseva et al., 2005).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording

Most experiments were performed in L-15 cell culture medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing the following inorganic salts (in mM): NaCl (137), KCl (5.4), CaCl2 (1.26), MgCl2 (1.0), Na2HPO4 (1.0), KH2PO4 (0.44), MgSO4 (0.81). However, when we tested the effects of extracellular solution with low Ca2+, we used in the bath a modified Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing the following inorganic salts (in mM): NaCl (138), KCl (5.3), CaCl2 (1.5), MgCl2 (1.0), NaHCO3 (4.17), Na2HPO4 (0.34), KH2PO4 (0.44). All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Hair cells were observed with an inverted microscope using a 100× 1.3NA 0.2WD oil-immersion objective and differential interference contrast (DIC). To access the basolateral plasma membrane of the OHCs and IHCs, outermost cells were removed by gentle suction with a ∼5 μm micropipette (Fig. 1A, 2A). Smaller pipettes for whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM): CsCl (140), MgCl2 (2.5), Na2ATP (2.5), EGTA (1.0), HEPES (5). Osmolarity and pH of the intrapipette solution were adjusted with D-glucose and CsOH to match corresponding values of the bath (325 mOsm, pH=7.35). The pipette resistance was typically 2-4 MΩ when measured in the bath. Patch-clamp recordings were performed with a computer-controlled amplifier (MultiClamp 700B, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Series resistance was always compensated (up to 80% at a 16 kHz bandwidth). After compensation, the time constant of the recording system determined by the “membrane test” feature of the pClamp 9.0 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) was in the range of 13-50 μs. Between the records, IHCs were maintained at a holding potential of -65 mV, while OHCs were held at -70 mV. Unless specifically stated, we did not correct the values of holding potential for the voltage drop across the series resistance. For the period of MET recordings, the holding potential was temporarily changed to -85 or -90 mV. MET responses were low-pass filtered at 20 kHz (Bessel type) and averaged 4 times.

Figure 1.

Recordings of MET responses in cochlear hair cells. A, Cultured organ of Corti explant with a piezo-driven probe (left) and a patch pipette (right). A third pipette (left-top) was used to deliver test solutions to the hair bundle. Image of the probe was projected to a pair of photodiodes (dashed rectangles) that monitor displacement stimuli. The specimen was visualized on an inverted microscope. Scale bar: 5 μm. B, In-scale schematic drawing of a 5 μm probe deflecting stereocilia of Myo15+/sh2 (top) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (bottom) IHCs. Stereocilia of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are deflected by the probe located at the top of the bundle.

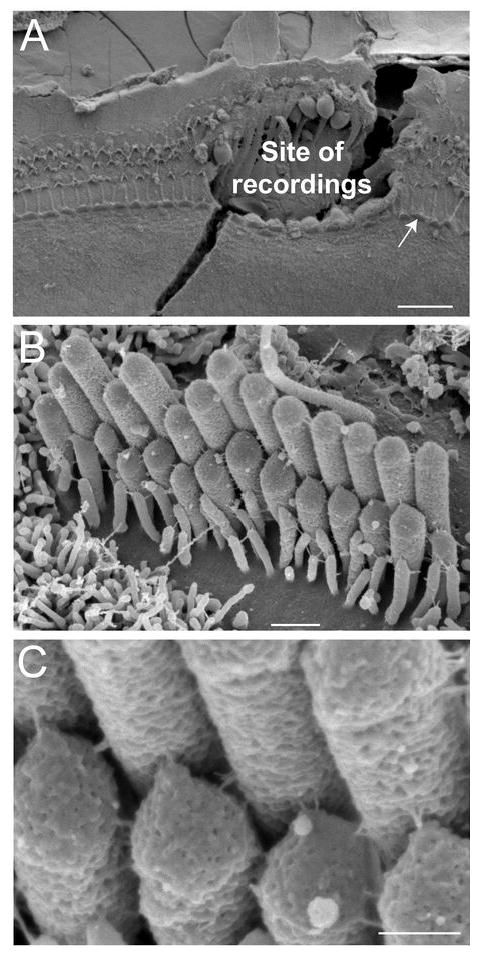

Figure 2.

Post-experimental examination of specimens. A, The site of patch-clamp recordings is easy to identify even in the presence of the SEM preparation artifact (a fracture across the recording site). B, C, An IHC that is indicated by an arrow in A is shown at high (B) and very high (C) magnifications. Our oldest Myo15+/sh2 preparation (P4 + 5 days in vitro) is shown in order to illustrate preservation of IHC morphology in vitro. Scale bars: (A) 20 μm; (B) 0.5 μm; (C) 200 nm.

We did not analyze a cell with a maximal MET current less than 0.4 nA at holding potentials of -85 or -90 mV. Following the general wisdom of the field, we reason that a small amplitude of MET current is likely to indicate excessive damage to the MET apparatus, loading of the cell with Ca2+, improper fitting of the stimulating probe to the hair bundle, or other potential artifacts.

Hair bundle deflection by a piezo-driven probe

We deflected a hair cell bundle with a stiff glass probe that had been fire-polished to a diameter that matches the V-shape of the hair bundle (Fig. 1). Therefore, the diameter of the probe is determined by the curvature of the bundle and may vary from ∼3-4 μm for OHCs at P3 to almost 10 μm for older IHCs. All experiments were performed with hair cells at the mid-cochlear location, i.e. at the basal end of the first (apical) turn or at the beginning of the second turn of the cochlea. Since the length of the tallest OHC and IHC stereocilia at this cochlear location at P3-9 is in the range of ∼1.5-3 μm (Kaltenbach et al., 1994; Holme et al., 2002; Rzadzinska et al., 2005), the probe must contact stereocilia at the lower half of its tip, even in hair cells of wild type mice (Fig. 1B). In case of uniformly short stereocilia of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, the probe is positioned at the top of the bundle (Fig. 1B). There is an ∼15° angle between the axis of probe movement and the bottom surface of a Petri dish, which translates a maximal movement of the probe of ∼1 μm into a horizontal movement of ∼0.96 μm and a vertical movement of ∼0.27 μm (Fig. 1B). This vertical movement is less than the typical height of Myo15sh2/sh2 hair bundles (∼0.5-1 μm).

The probe was moved by a fast piezo actuator (PA 4/12, Piezosystem Jena, Germany) driven by a high power amplifier (ENV 800, Piezosystem Jena, Germany). The command voltage steps were generated by pClamp software and low pass filtered with the analog Bessel-type filter (48 dB/oct; Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA) that is known for its superior step response. The movement of the probe was monitored (see below) and the filtering frequency was optimized experimentally for each probe to achieve the maximal speed of the probe movement but without excessive resonant oscillations. Typically, the filtering frequency was set just below the resonant frequency of the probe, which varied substantially, in the range of 10-20 kHz. To avoid lateral resonances, the length of the probe was kept to minimum, no more than 20 mm, typically ∼15 mm. Concentric mounting of the probe was also important. We tightly mount the probe into a concentric hole that was drilled in a 3 mm diameter plastic screw. To provide additional stiffness, the screw-probe assembly was first tightened with a small strip of Parafilm and then tightly secured to the piezo actuator.

We monitored horizontal movement of the probe by a photodiode technique (Crawford et al., 1989). A custom-made lens projected the image of the probe to the pair of photodiodes (SPOT-2DMI, OSI Optoelectronics, Hawthorne, CA) at a 600× magnification. The photodiode signal was amplified by precision current preamplifiers (SIM918, Stanford Research Systems, Sunnyvale, CA) and recorded with pClamp software. It is impossible to monitor the actual movement of stereocilia beneath the probe, because the probe obscures the stereocilia. Since the probe is rigid, the tallest stereocilia are deflected with the speed of the probe movement, which had a time constant of 12-20 μs (Fig. 3G). For uniformly short stereocilia of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, it means that all responding stereocilia become deflected in ∼12-20 μs. For wild type IHCs, the overall speed of bundle displacement depends on whether or not the shorter rows of stereocilia move in unison with the tallest row. Coherent stereocilia movement at high frequencies has been demonstrated only for frog sacculus hair cells (Kozlov et al., 2007) but not for mammalian IHCs. Having these caveats in mind, we always monitor the time course of the MET current activation to estimate the speed of the force that is “sensed” by MET channels. The rising phases of MET current activation and the probe movement were fitted with a first-order Boltzmann function:

Figure 3.

Loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. A, B, SEM images of Myo15+/sh2 (A) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (B) IHCs from approximately the same mid-cochlear location. Insets show stereocilia links of these cells at higher magnification (and different viewing angle in B). Scale bars: 1 μm (main panels); 200 nm (insets). C, D, MET responses (top traces) evoked by the graded deflections of stereocilia in the same specimens that were imaged in A and B. Horizontal movement of the piezo-driven probe was monitored by a photodiode technique (bottom traces). Responses to negative deflections are shown in black color. Right panels show the beginning of MET responses on a faster time scale to reveal fast adaptation. Adaptation at the small bundle deflection of 150 nm (τad) is fitted with single exponential decay (dashed lines). E, H, The same MET records on an ultra-fast time scale to reveal time constants of MET activation and probe movement. Holding potential was -90 mV. Age of the cells: (A, C, E) P2+2 days in vitro; (B, D, H) P3+1 day in vitro. F, Average maximum MET responses. G, Time constants of MET activation (τact): average and row data. Gray area indicates the range of time constants of the stimuli in the same experiments. I, Percent changes of the MET current at the end of 25 ms stimulation step (extent of adaptation) as a function of stimulus intensity. J, The relationship between maximum MET current and time constant of adaptation at the small bundle deflection of 150 nm. Solid line shows least squares fit to data points from Myo15+/sh2 IHCs, R = -0.91, p<0.0001. The same records contribute to F, G, I and J. Number of cells: n=17 (Myo15+/sh2), n=18 (Myo15sh2/sh2). All averaged data are shown as Mean±SE. Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * – p<0.05, ** – p<0.01, *** – p<0.0001 (t-test of independent samples).

where Rmax is the ampitude of the response, t0 is the mid-point of the transition, and τ is the time constant. This function was chosen because it gives the best approximation of the command voltage steps in our experimental conditions. The reported activation time constants (τact) are the time constants of this fit.

Voltage-displacement relationship of the probe movement was calibrated by video recording and command voltage was converted to displacement units. Resting (zero) position of the bundle was determined by manually advancing the piezo-probe toward the bundle in the excitatory direction until the MET current appeared and then stepping back until the cell current returned to normal.

Hair bundle deflection with a fluid-jet

The pressure is generated by High Speed Pressure Clamp (ALA HSPC-1, ALA Scientific, Westbury, NY) and applied to the back of a glass pipette with a tip diameter of ∼5 μm that is filled with the bath solution. The pipette tip is positioned at a distance of ∼5-10 μm in front of the hair bundle (Fig. 9B). Before each experiment, the steady-state pressure is adjusted to produce zero flow at resting conditions. This adjustment is performed by monitoring debris movement in front of a water-jet using high-resolution DIC imaging. During the experiment, the movement of the hair bundle is recorded at a video rate for subsequent frame-by-frame computation of the bundle displacements using algorithms that were developed for quantifying electromotility of isolated OHCs (Frolenkov et al., 1997).

Figure 9.

Abnormal directional sensitivity of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. A, MET currents evoked by negative displacements of stereocilia with a piezo-driven stiff probe in Myo15sh2/sh2 (top) and Myo15+/sh2 (middle) IHCs. Bottom traces show command voltage converted to displacement units. Holding potential: -90 mV. B, MET responses evoked by consecutive negative and positive deflections of the same bundle by a fluid-jet. Top image illustrates a fluid-jet pipette (left), a Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC bundle (middle), and a patch pipette (right). Traces below show the records obtained in this experiment (from top to bottom): MET responses, movement of the stereocilia bundle determined by off-line frame-by-frame analysis of the video record (Frolenkov et al., 1997), and the command pressure that was applied to the fluid-jet pipette. C, In an experiment when the probe was strongly adhered to the hair bundle, both positive and negative ramp-like deflections of stereocilia evoked MET responses in a Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC. Top traces show MET responses at different holding potentials (right), which are indicated after correction for the voltage drop across series resistance. Note that the MET responses reverse at the holding potential close to zero as expected for non-selective cation channels. Bottom trace shows the stimulus. D, Current-displacement relationship derived from MET responses at +71 mV holding potential in (C). To illustrate sampling frequency, the data are presented as a scatter plot of individual measurements during ramp deflections of stereocilia. The ages of the cells: (A) P3+4 days in vitro and P3+3 days in vitro; (B) P3+4 days in vitro; (C, D) P4+4 days in vitro. Insets in (A and D) show schematically the direction of the stimuli.

Drug delivery

A puff pipette with an opening of ∼3 μm was filled either with dihydrostreptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in the extracellular solution, or with a low Ca2+ HBSS containing (in mM): NaCl (138), KCl (5.3), CaCl2 (0.02), MgCl2 (1.0), NaHCO3 (4.17), Na2HPO4 (0.34), KH2PO4 (0.44), or with zero-Ca2+ HBSS (as above but without Ca2+) supplemented with 5 mM of BAPTA, or with FM1-43 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) dissolved in the extracellular solution to a final concentration of 10 μM. The puff pipette was placed behind the hair bundle at a distance of ∼30 μm in such a way that a test application of extracellular solution did not evoke any noticeable MET current. Moderate pressure (10-15 kPa) was applied to the back of the puff pipette by a pneumatic injection system (PDES-02T, npi electronics, Tamm, Germany) gated under software control. Subtilisin (protease type XXIV; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in extracellular solution and applied to the bath.

Fluorescent imaging

Time-lapse live cell fluorescent imaging was used to observe FM1-43 accumulation in the auditory hair cells. Cultured organ of Corti explant was observed with epifluorescent illumination using Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope equipped with a 100× 1.3 NA oil-immersion objective and CARV confocal imager (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Images were acquired with an ORCA-II-ER cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu Co., Hamamatsu City, Japan) using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Downington, PA).

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

At the end of every experiment, the cultured organ of Corti explant was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2 for 1-2 hours at room temperature. The specimen was dehydrated in a graded series of acetone, critical-point dried from liquid CO2, sputter-coated with platinum (5.0 nm, controlled by a film-thickness monitor), and observed with a field-emission SEM (S-4800, Hitachi, Japan). The location of the cells that have been patched is easily identifiable on SEM images because neighboring cells are removed in order to gain access to the basolateral plasma membrane of the hair cells (Fig. 2A). Since a hair cell is usually damaged after detaching the patch-clamp pipette, we examine the hair bundles in the undisturbed regions of the epithelium next to the recording area (Fig. 2B). Tip links can be easily identified in these images (Fig. 2C).

Results

Normal mechanosensitivity but disrupted adaptation in IHCs without functional myosin-XVa

Stereocilia link morphology is dramatically different in IHCs of young normal hearing heterozygous (Myo15+/sh2) and deaf homozygous Myo15sh2/sh2 mice. In contrast to the apparently normal set of tip and “side” links of Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3A), the abnormally short Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC stereocilia of approximately equal heights are interconnected only by “top-to-top” links that run perpendicular to the stereocilia (Fig. 3B). We used a conventional whole-cell patch-clamp technique to record MET responses in hair cells of the cultured organ of Corti explants at the mid-cochlear location (Fig. 1). MET currents were evoked by deflection of the stereocilia bundles with a piezo-driven rigid glass probe (Fig. 1B). After MET recordings, the same specimens were examined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to determine the morphology of stereocilia links (Fig. 2).

In spite of the absence of “classical” obliquely oriented tip links, Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs exhibit prominent MET responses (Fig. 3D). The maximal amplitude of MET current in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was actually larger than that in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3C, D, F). We included in this study only the cells with MET current larger than 0.4 nA (at a holding potential of -90 or -85 mV). In all Myo15+/sh2 IHCs, MET current showed prominent adaptation with a major, rapid component occurring at a sub-millisecond time scale (Fig. 3C). Following a commonly accepted definition, we will refer to this component as “fast” adaptation. None of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs exhibited fast adaptation (Fig. 3D).

In each experiment, we deflected the hair bundle as fast as possible without evoking the resonant oscillations of the piezo-driven probe. The time constant of the probe movement determined by a photodiode technique was in the range of 12-20 μs (Fig. 3G). In the majority of experiments with either Myo15+/sh2 or Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, MET responses were activated as fast as we could move the probe (Fig. 3E, H). The average time constant of MET current activation was identical in normal Myo15+/sh2 IHCs and in mutant Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3G). Similar to the previous report in rat OHCs (Ricci et al., 2005), these data do not resolve the actual activation kinetics of the MET channels. They just show that the activation of MET responses follow the stimulus. However, the time constant of our stimulation (<20 μs) was rapid enough to evoke fast adaptation in wild type IHCs and in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs. In fact, we still detected robust fast adaptation in normal IHCs, even when we intentionally decreased the speed of bundle deflection and activated MET responses with the time constant as slow as ∼50 μs (Supplemental Fig. S1). This is slower than the time constant of any of our MET records in the mutant Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3G). We concluded that the absence of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs could not be due to an abnormally slow speed of MET activation.

The overall extent of adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was severely affected at all non-saturating stimuli intensities. A residual adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was small, less than 30% as compared to almost 90% adaptation at small bundle deflections in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3I). The time constant of adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was an order of magnitude larger than that of the fast adaptation in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3J). This relatively slow residual adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs may correspond to the “slow” adaptation in wild type IHCs. Indeed, the time constants of this residual adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs were identical to the time constants of slow adaptation in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 4C). Typically, adaptation is more prominent at low stimuli intensities and vanishes at higher intensities (Assad et al., 1989; Crawford et al., 1989; Ricci et al., 2005). This phenomenon was prominent in phenotypically normal Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3C), but not in the mutant Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3D; 4A, B).

Figure 4.

“Slow” adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. A, B, SEM examination (A) and MET responses (B) in an experiment with one of the most prominent adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. Inset in A shows top-to-top stereocilia links; the specimen is viewed from an ∼30° angle. Age of the specimen was P3+2 day in vitro. Scale bars: (A) 1 μm; (A, inset) 100 nm. C, Scatter plot of the time constants of adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs and slow adaptation in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs versus maximum MET current. The same set of experiments as in Figure 3. Time constants of slow adaptation in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs were determined for MET responses to 300-600 nm deflections by fitting these responses to double exponential function.

The lack of functional myosin-XVa does not affect adaptation in OHCs

Starting from late embryonic development, myosin-XVa is present at the tips of every stereocilium not only in IHCs, but also in OHCs and vestibular hair cells of wild type mice and rats (Belyantseva et al., 2003; Rzadzinska et al., 2004; Belyantseva et al., 2005; Schneider et al., 2006). Therefore, if myosin-XVa is a part of the machinery of fast adaptation, fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs should also be disrupted, similarly to the loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs.

OHCs of young postnatal Myo15sh2/sh2 mice possess numerous stereocilia links (Fig. 5B) that are similar to the links in OHCs of normal-hearing heterozygous littermates (Fig. 5A) and typical for this developmental age (Goodyear et al., 2005). In contrast to Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, tip links (i.e. filaments running from the top a shorter stereocilium to the side of a taller stereocilium along the axis of normal mechanosensitivity) are still present in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs (Fig. 5B, inset), although not as prominent as in normal Myo15+/sh2 OHCs (Fig. 5A, inset). Apparently, the dramatic difference of tip link morphology between Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs and OHCs is due to a still apparent staircase arrangement of abnormally short stereocilia in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Apparently normal adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs. A, B, SEM images of Myo15+/sh2 (A) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (B) OHCs from approximately the same mid-cochlear location. Insets show stereocilia links at higher magnification. Presumable tip links in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bars: 0.5 μm (main panels) and 200 nm (insets). C, D, MET responses (top traces) evoked by the graded deflections of stereocilia in the same specimens that were imaged in A and B. Movement of the piezo-driven probe was calibrated by video recording and command voltage was converted to displacement units. Right traces show the beginning of MET responses on a faster time scale. Fast adaptation to small stimuli is fitted with single exponential decays (dashed lines). Holding potential was -85 mV. Age of the cells: (A, C) P2+1 day in vitro; (B, D) P2+2 days in vitro. E, Percent changes of the MET current at the end of 25 ms stimulation step (extent of adaptation) as a function of stimulus intensity. Data are shown as Mean±SE. F, The relationship between maximum MET current and the time constant of fast adaptation to small bundle deflection of 150 nm. Solid line shows least squares fit to all points, R = -0.88, p<0.0001. The same records contribute to E and F. Number of cells: n=8 (Myo15+/sh2), n=12 (Myo15sh2/sh2).

In Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs, we observed a fast mechanically gated current (Fig. 5D) that was indistinguishable from the MET current in Myo15+/sh2 OHCs (Fig. 5C). These MET responses showed prominent fast adaptation (Fig. 5C, D; right traces). Slow adaptation, the subsequent decay of MET current on a time scale of tens of milliseconds, was also observed (Fig. 5C, D; left traces). We did not find any statistically significant differences in the extent of adaptation between Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs at any stimulus intensities (Fig. 5E). Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs also showed a nearly identical inverse relationship between the time constant of fast adaptation and the maximum MET current (Fig. 5F). An almost identical dependence of the fast adaptation on MET current has been reported for OHCs of wild type rats (Kennedy et al., 2003). The largest MET current in these experiments was more than 1 nA and it was observed in a mutant OHC (Fig. 5F). We concluded that myosin-XVa is unlikely to be a part of the fast adaptation machinery, at least in young postnatal OHCs.

Postnatal development and the loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs

All our data were obtained from cells located approximately at the middle of the cochlea, i.e. at the basal end of the first (apical) turn or at the beginning of the second turn of the cochlea, and at the equivalent age of P3-9 (age of dissection + days in vitro). At this developmental stage, the distribution of stereocilia links as well as the expression and localization of many known stereocilia link proteins are not yet fully mature (Goodyear et al., 2005; Ahmed et al., 2006; Nayak et al., 2007). In contrast, maturation of MET responses seems to be generally completed by P3 in the OHCs of wild type rats (Kennedy et al., 2003; Waguespack et al., 2007) and mice (Kros et al., 1992; Stauffer and Holt, 2007), perhaps with the exception of the OHCs at the very apex of the cochlea (Waguespack et al., 2007). In our experiments, we observed no changes in the adaptation properties of MET responses within the developmental period of P3-9 neither in OHCs nor in IHCs, in both Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 mice (Supplemental Fig. S2).

All our data were obtained from cultured organ of Corti explants. In vitro conditions may accelerate or slow down the developmental maturation of stereocilia bundles as well as affect the distribution and the number of stereocilia links. Therefore, we examined stereocilia bundles of IHCs in the acutely dissected organs of Corti from Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 mice. Although we observed some signs of accelerated maturation in vitro, such as slightly accelerated thickening of stereocilia and retraction of surrounding microvilli together with the smallest excess stereocilia, we did not notice any apparent changes in the distribution and the abundance of stereocilia links neither in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs nor in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Impaired Ca2+-sensitivity of the MET apparatus in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs

It is well known that Ca2+-infux through the MET channels promotes adaptation in wild type hair cells (Assad et al., 1989; Crawford et al., 1989; Ricci and Fettiplace, 1998; Beurg et al., 2006). Because adaption is severely disrupted in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, we hypothesize that Ca2+-dependence of the MET apparatus is somehow affected in these cells. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of low extracellular Ca2+ on MET responses. It is known that application of low extracellular Ca2+ increases the amplitude of MET responses and the time constant of adaptation (Crawford et al., 1991; Ricci and Fettiplace, 1998). We observed both these phenomena in Myo15+/sh2 (Fig. 6A) but not in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 6B). Application of low Ca2+ solution to undeflected hair bundles produced an increase of whole-cell current in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs but evoked only negligible current changes in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 6C, E). The average whole-cell current responses to low extracellular Ca2+ were significantly different in Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, while the resting current was almost identical in Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 6D). The increase of MET responses and the slowing of adaptation by low extracellular Ca2+ were also observed in the mutant Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs (data not shown). It is worth remembering that Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs have prominent fast adaptation (Fig. 5). In Myo15+/sh2 IHCs and Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs, the average increase of MET responses by low extracellular Ca2+ was statistically significant in contrast to a nonsignificant decrease of MET responses in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 6F). We concluded that the Ca2+-dependent mechanisms normally deactivating MET channels are not functional in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. The absence of dependence of the adaptation time constants on maximal MET currents in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3J) is also consistent with the lack of Ca2+ sensitivity in these cells. This dependence was observed in normally adapting Myo15+/sh2 IHCs, Myo15+/sh2 OHCs, and Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs (Fig. 3J; 5F).

Figure 6.

Disrupted Ca2+-sensitivity of the MET machinery in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. A, B, MET responses in Myo15+/sh2 (A) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (B) IHCs evoked by the graded deflections of stereocilia in an extracellular solution containing 1.5 mM Ca2+ (top traces) and in low Ca2+ solution containing 20 μM Ca2+ (middle traces). Bottom traces show command voltage converted to displacement units. Right panels show the same records on a faster time scale. Scale bars of the MET current apply to both top and middle traces. C, E, Changes of the whole-cell current produced by low extracellular Ca2+ in the same IHCs. Dashed lines indicate the breaks, during which we examined MET responses in low Ca2+ environment. Age of the cells: (A, C) P3+5 days in vitro; (B, E) P3+4 days in vitro. D, Resting whole-cell current at holding potential of -60 mV (Irest) and the changes of this current (ΔI) evoked by the application of low Ca2+ extracellular medium to the stereocilia bundles of Myo15+/sh2 (open bars) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (closed bars) IHCs. F, Maximum amplitude of MET responses during and after application of low Ca2+ extracellular solution as a percentage of maximal amplitude of MET responses before application. MET responses were recorded at holding potential of -90 mV. Averaged data in D and F are shown as Mean±SE. Number of cells: n=6 (IHCs, Myo15+/sh2), n=8 (IHCs, Myo15sh2/sh2), n=3 (OHCs, Myo15sh2/sh2). Asterisks indicate statistical significance: * – p<0.05, ** – p<0.01 (t-test of independent samples in D and paired t-test in F).

Mechanotransduction in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is mediated by “top-to-top” stereocilia links

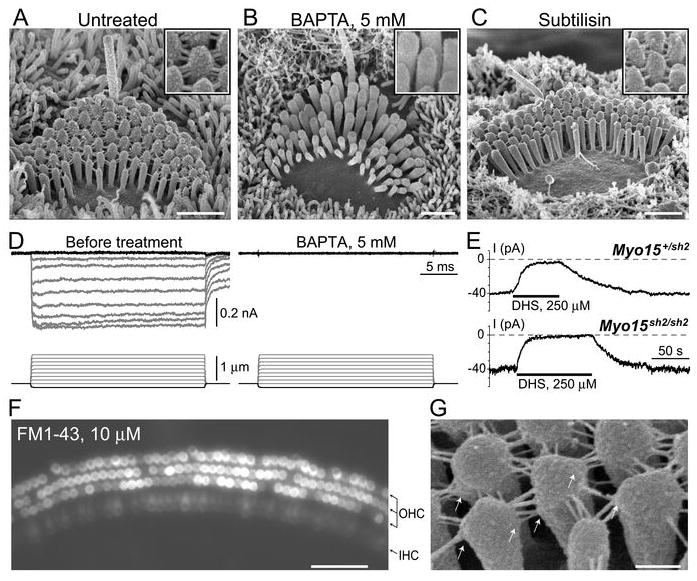

Although “top-to-top” stereocilia links in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs cannot be classified as “tip links” based on their localization, they exhibit the known biochemical properties of tip links (Assad et al., 1991; Zhao et al., 1996; Goodyear and Richardson, 1999): sensitivity to Ca2+ chelation by BAPTA and insensitivity to subtilisin treatment (Fig. 7A, B, C). BAPTA treatment effectively eliminated all stereocilia links in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 7B). However, this does not mean that the absence of myosin-XVa somehow eliminates BAPTA-insensitive side links. In the first week of postnatal development, side links are not well developed in mouse IHCs (Goodyear et al., 2005). The same BAPTA treatment completely eliminated all stereocilia links also in the wild type age-matched control IHCs, but did not disrupt side links in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs (data not shown). In Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, BAPTA treatment that eliminates top-to-top links also disrupts MET responses (Fig. 7D). Therefore, we conclude that MET responses in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are likely to be mediated by the top-to-top links.

Figure 7.

Mechanotransduction in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is mediated by “top-to-top” stereocilia links. A-C, SEM images of the organ of Corti explants incubated in standard HBSS (A), Ca2+-free HBSS supplemented with 5 mM of BAPTA (B), and in standard HBSS supplemented with 50 μg/ml subtilisin (C). Insets show magnified images of stereocilia links. All incubations were performed at room temperature. The duration of incubations: (A, B) 5 min; (C) 60 min. D, MET responses in a Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC before (left) and after (right) application of Ca2+-free HBSS supplemented with 5 mM of BAPTA for 1 min. Holding potential: - 90 mV. E, Whole-cell current responses evoked by the application of 250 μM of dihydrostreptomycin to the stereocilia bundle of Myo15+/sh2 (top) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (bottom) IHCs. Holding potential: -60 mV. F, Brief application of 10 μM of FM1-43 to the cultured Myo15sh2/sh2 organ of Corti explant (45 seconds at room temperature) results in accumulation of the dye in both OHCs and IHCs. Arrows at the right side of the panel point to three rows of OHCs and one row of IHCs. G, SEM image of a Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC showing membrane “tenting” (arrows) at the attachments of top-to-top stereocilia links. The ages of the cells: (A-C) P3+3 days in vitro; (D) P3+1 day in vitro; (E) P3+4 days in vitro; (F) P4+4 days in vitro; (G) P1+4 days in vitro. Scale bars: (A-C) 1 μm; (F) 50 μm; (G) 200 nm.

Are the “top-to-top” stereocilia links tensioned at rest?

SEM images show splaying of the hair bundle after BAPTA treatment (Fig. 7B), which may be an artifact of SEM preparation, but may also indicate that the stereocilia of an untreated Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC bundle are held together by the tension of the top-to-top links. Because MET channels in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are activated by both positive and negative displacements (Fig. 9, below), it is not easy to determine whether such resting tension exists. We applied to resting (undeflected) stereocilia bundles dihydrostreptomycin (250 μM), a known reversible inhibitor of MET channels (Marcotti et al., 2005). In both Myo15+/sh2 and Myo15sh2/sh2 hair cells, this application produced a similar inhibition of whole-cell current (Fig. 7E). The average current response produced by dihydrostreptomycin at -60 mV holding potential was 36±8 pA in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Mean±SE, n = 4) and 42±6 pA in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (n = 4). The difference is not statistically significant (t-test of independent samples).

Then we briefly applied to Myo15sh2/sh2 organ of Corti explants FM1-43, a small styryl dye that permeates mechanotransduction channels (Gale et al., 2001; Meyers et al., 2003). We observed accumulation of this dye in both OHCs and IHCs, albeit the labeling of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was significantly less intense (Fig. 7F). The surrounding supporting cells were not labeled at all. This difference between the intensity of FM1-43 labeling in OHCs and IHCs is not surprising, because it is well documented in the similar cultured organ of Corti preparations in the wild type (Gale et al., 2001; McGee et al., 2006; van Aken et al., 2008). Therefore, MET channels in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs may have some non-zero open probability at rest.

It was proposed that the resting tension of the tip links results in “tenting”, an asymmetrical pointed shape of the tip of the stereocilium at the attachment to the tip link (Rzadzinska et al., 2004). Rounded shape of the tips of tip link-free stereocilia in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3B; Fig. 4A) is consistent with this proposal. Furthermore, in some but not all Myo15sh2/sh2 specimens, we observed “tenting” at the side of a stereocilium, at the attachment points of the top-to-top links (Fig. 7G). These observations may indicate that: 1) top-to-top links may indeed be under tension in resting conditions; and 2) even when the force is applied in unfavorable direction perpendicularly to the actin core of stereocilium, some remodeling of the stereocilia cytoskeleton may still be possible.

Although taken alone none of the above observations is compelling, all of them together allow us to propose that top-to-top links in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs may be under certain tension in resting conditions.

Abnormal directional sensitivity of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs

Mathematical models predict that stretching an obliquely oriented tip link (or an elastic element associated with this link) is proportional to the angular deflection of the stereocilia bundle, whereas stretching a horizontal link (e.g. the link oriented parallel to the cuticular plate such as the top-to-top link) is proportional to the square of the angle of stereocilia deflection (Geisler, 1993). Therefore, at small bundle deflections, top-to-top links should undergo minimal stretching as compared to the stretching of obliquely oriented tip links (Geisler, 1993; Pickles, 1993). In qualitative correspondence with this prediction, the average current-displacement relationships (IX-curves) showed that MET responses to the small deflections in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are smaller than the MET responses to similar stimuli in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 8). Quantitative testing of this model prediction would require systematic measurements of the shape of stereocilia as well as stereocilia link dimensions and orientations in the specimens devoid of tissue shrinkage artifacts associated with SEM preparation, e.g. in the fast-frozen freeze-substituted preparations.

Figure 8.

Average relationships (Mean±SE) between peak transduction current and probe displacement in Myo15+/sh2 (open circles, n=17) and Myo15sh2/sh2 (closed circles, n=18) IHCs. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of the difference (p<0.05, t-test of independent samples). The same set of experiments as in Fig. 3F,G,I,J and 4C.

Mediation of mechanotransduction by top-to-top links should also have a profound impact on the directional sensitivity of the hair bundle. In contrast to wild type hair bundle, where tip link tension increases when the bundle is deflected toward the tallest stereocilia and decreases when the bundle is deflected in the opposite direction, movements of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC stereocilia in either positive or negative directions should produce an increase of tension of the top-to-top links resulting in comparable MET responses. In full correspondence with this prediction, we found that deflections of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC bundles in the normally inhibitory direction (away from kinocilium) produced robust mechanotransduction responses (Fig. 9A, top traces). The same stimulation in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs evoke significant MET current only at the falling phase of bundle deflection (Fig. 9A, middle traces) suggesting generally mature directional sensitivity of these age-matched (P4-P9) control IHCs. Furthermore, abnormal directional sensitivity of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was also observed in the experiments where we deflect stereocilia in positive and negative directions in the same record using fluid-jet stimulation and where we monitor simultaneously the movement of the stereocilia bundle (Fig. 9B).

Bidirectional stimulation of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs with a piezo-driven probe is complicated, because the probe is deflecting stereocilia from the top (Fig. 1B) and, therefore, the adhesion forces between the probe and stereocilia have to be really strong to produce MET responses to negative displacements. Among Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs reported in this study, it happened only twice and the results were similar. In these two Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, we were able to deflect stereocilia bundle with biphasic ramps (Fig. 9C) and generate a detail current-displacement relationship (Fig. 9D). This relationship clearly shows the abnormal directional sensitivity of the Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC bundle and confirms the prediction that the tension of top-to-top links is proportional to the square of the angle of stereocilia deflection (Geisler, 1993). Thus, we have reasons to believe that MET responses in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are indeed mediated by top-to-top links.

Discussion

This is the first report of the fast mechanotransduction in hair cells lacking “classical” tip links. Although the absence of myosin-XVa in IHC stereocilia may potentially have a number of effects on mechanotransduction, the disruption of fast adaptation is the most prominent effect. This loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is not due to a slow activation or smaller amplitude of the MET current but rather represents the disruption of Ca2+-sensitivity of the MET channels. Myosin-XVa itself is unlikely to participate in fast adaptation, because myosin-XVa deficient Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs have apparently normal adaptation as discussed below. Therefore, we propose that the machinery of fast adaptation includes an accessory element(s) to the transduction channel that is inactivated in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs but not OHCs.

The speed of MET channel activation and the loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs

Current techniques of hair bundle deflection with a piezo-driven probe are too slow to resolve the activation kinetics of the MET channels in mammalian auditory hair cells (Ricci et al., 2005). Therefore, it is still theoretically possible that the absence of myosin-XVa in IHC stereocilia somehow slows down the activation of the MET channels. However, any such effect must occur on a time scale below ∼20 μs, which is the identical time constant of the rising phase of MET responses in Myo15sh2/sh2 and Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 3G). Even slower stimuli are able to evoke fast adaptation in phenotypically normal Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (Fig. S1). Moreover, when the MET channels have order of magnitude slower activation kinetics, fast adaptation still occur in turtle auditory hair cells (Ricci et al., 2005). Finally, Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are not sensitive to extracellular Ca2+ even in resting conditions, without any mechanical stimulation of the bundle (Fig. 6D). Thus, even if some unnoticed changes of the activation kinetics of the MET channels in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs do occur, they are unlikely to account for the dramatic reduction of MET adaptation observed in these cells.

Role of stereocilia links in the gating of MET channels

Although generally accepted, the assumption that the MET channels are gated by the tension of tip links is largely based on one experimental finding: the concurrent disappearance and recovery of mechanotransduction together with tip links following BAPTA treatment (Assad et al., 1991; Zhao et al., 1996). Here we examined and confirmed two predictions of the “tip link” theory: the abnormal current-displacement relationship at small bundle displacements (Fig. 8); and the abnormal directional sensitivity (Fig. 9) of a bundle with mechanosensitive “top-to-top” links.

Maximum MET current in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs was larger than that in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs. To some extent, it could be attributed to the release of Ca2+-dependent inhibition of MET channels in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs (Fig. 6). However, MET current in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs did not saturate even at the largest bundle deflections (Fig. 8), suggesting that, in addition to their Ca2+-insensitivity, Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs may have more functional MET channels per cell. Indeed, the total number of stereocilia in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is slightly larger than that in Myo15+/sh2 IHCs (76±4, n=16 and 68±2, n=22, respectively; equivalent age: P3-6). Moreover, the smallest excess stereocilia at the base of postnatal Myo15+/sh2 IHC bundle are unlikely to contribute to MET current, because they are unlikely to be deflected when the force is applied to the taller stereocilia. In contrast, equally short stereocilia of Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs are probably deflected all together, producing larger MET current. Finally, it is also possible that some MET channels become associated with “inappropriate” links in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, resulting in a larger number of MET channels per stereocilium. In any case, our data show that stereocilia links are critical for mechanotransduction even in such an unusual hair bundle that has only top-to-top links.

Different effects of myosin-XVa deficiency in OHCs and IHCs

Our data demonstrate that myosin-XVa is required for normal adaptation in IHCs but not in OHCs. One could suggest that IHCs utilize myosin-XVa for adaptation, while OHCs use another molecule. However, available reports convincingly show the presence of myosin-XVa at the tips of wild type stereocilia in both IHCs and OHCs, including the young postnatal specimens as we used in this study (Belyantseva et al., 2003; Rzadzinska et al., 2004). Alternatively, the absence of myosin-XVa within the MET complex might be differently compensated for in IHCs and OHCs by another unconventional myosin. This hypothetical compensation has to be absent in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs and nearly complete in Myo15sh2/sh2 OHCs. However, in the wild type, the known stereocilia myosins that could affect adaptation (Ic, VIIa, and IIIa) are available in both IHCs and OHCs (Hasson et al., 1995; Dumont et al., 2002; Schneider et al., 2006). It is more likely that the loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is associated with an unusual hair bundle architecture in these cells, which adds to other predicted effects of this architecture that have been demonstrated in this study (Fig. 8-9).

Mechanotransduction in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs and a “channel reclosure” model of fast adaptation

In its simplest form, the “channel reclosure” model proposes that fast adaptation results from deactivation of the MET channel by Ca2+ ions that bind to this channel at some intracellular site (Howard and Hudspeth, 1988; Crawford et al., 1991; Wu et al., 1999; Holt and Corey, 2000). Therefore, the model implies that the adaptation should occur whenever there is a substantial and fast influx of Ca2+ through the MET channels. The large and fast MET current in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is not compatible with this simple model. Furthermore, our data show that sensitivity of the MET machinery to extracellular Ca2+ can be disabled without apparent degradation of the amplitude and the speed of MET responses. In turtle hair cells, low extracellular Ca2+ increases single channel conductance of the mechanotransducer (Ricci et al., 2003). This effect is probably mediated through a Ca2+ binding site that is different from the site responsible for fast adaptation, because depolarization of the cell eliminates fast adaptation but does not influence MET channel conductance (Ricci et al., 2003; Beurg et al., 2006). The large amplitude of MET responses and the loss of sensitivity to extracellular Ca2+ indicate that the MET channels in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs may be “locked” in a high conductance state. Apparently, Ca2+-sensitivity is not an intrinsic property of the MET channel but it also depends on a microenvironment of the channel. To explain these observations, a more elaborate model may include an accessory element that, upon Ca2+ binding, forces the MET channel to change conformation, decreasing the single channel conductance (Fig. 10A). Another Ca2+-sensing accessory element may be responsible for fast adaptation, as it has been proposed in the “tension release” model (Bozovic and Hudspeth, 2003; Martin et al., 2003). It is easy to envision how a tension release element could be dissociated from the MET channel (Fig. 10B) or become inactive (Fig. 10C) in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. It was demonstrated that fast adaptation depends on myosin-Ic (Stauffer et al., 2005) that may serve as a tension release structural element (Tinevez et al., 2007; Adamek et al., 2008; Hudspeth, 2008). In reality, all hypothetical accessory elements depicted in Figure 10 may consist of just one protein with multiple Ca2+ binding sites, several different proteins, or one or more macromolecular complexes. Irrespective of the molecular nature of these accessory elements, the loss of fast adaptation in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs is consistent with a “tension release” model, but requires modifications to the simple “channel reclosure” model.

Figure 10.

Some potential mechanisms that could result in the loss of Ca2+ sensitivity and fast adaptation of the mechanotransducer in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs. A, An accessory element may convey Ca2+-sensitivity to the MET channel. Upon Ca2+ binding, this accessory element may force conformational changes of the MET channel into the state with a lower single channel conductance. In Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, this element may somehow become dissociated from the MET channel. For example, it may be localized at the tip of a shorter stereocilium. The MET channels (open circles) may be localized at either or both ends of the tip link (Denk et al., 1995). B, According to the “tension release” model of fast adaptation, Ca2+ ions enter the cell and bind to the nearby “tension release” element that releases the tension applied to the MET channel (Bozovic and Hudspeth, 2003; Martin et al., 2003). If the “tension release” element is situated at the tip of a stereocilium, it may become separated from the MET channel in Myo15sh2/sh2 IHCs, resulting in loss of fast adaptation. C, Because myosin-Ic molecules are thought to be assembled in series along the length of a stereocilium (Gillespie and Cyr, 2004), the overall displacement produced by this assembly might also be directed along the stereocilium. If this “tension release” displacement is oriented along the stereocilium, it would decrease the tension of an obliquely oriented tip link in a normal Myo15+/sh2 IHC but would not be effective in changing the tension of a perpendicularly oriented top-to-top stereocilia link in a mutant Myo15sh2/sh2 IHC.

“Staircase” architecture of the hair bundle as a structural prerequisite for fast adaptation

In hair cells of all vertebrates, the mechanosensory stereocilia are arranged in rows of graded heights. This evolutionary conserved “staircase” architecture of the hair bundle was suggested to be absolutely essential for hair cell mechanosensitivity (Manley, 2000). Our study is the first to show prominent MET responses in hair cells without the staircase architecture of the stereocilia bundle. Therefore, the staircase architecture of the bundle is not a prerequisite for hair cell mechanosensation. However, the staircase morphology ensures the oblique orientation of the tip links (Pickles et al., 1984), which is essential for the optimal gain of the mechanotransducer (Howard and Hudspeth, 1987; Hacohen et al., 1989)(see also Fig. 8) and perhaps for fast adaptation (Fig. 3-5). Fast adaptation is linked to the active force generation in the stereocilia bundle (Ricci et al., 2000), which could amplify sound-induced vibrations in the cochlea (Martin and Hudspeth, 1999; Kennedy et al., 2005; Cheung and Corey, 2006). In non-mammalian species, this “stereocilia-based” amplification is likely to determine the sensitivity of hearing (Martin and Hudspeth, 1999; Manley, 2001). In mammals, the role of the “stereocilia amplifier” is less clear, because cochlear amplification requires an additional mechanism of prestin-based somatic motility of OHCs (Liberman et al., 2002; Dallos et al., 2008). However, even in mammalian hair cells, fast adaptation may contribute to optimal filtering of the MET responses irrespective of whether it is associated with cochlear amplification or not (Ricci, 2003; Dallos et al., 2008). Our study suggests that the staircase architecture of the hair bundle may be a structural prerequisite for fast adaptation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank I.A. Belyantseva, K.S. Campbell, T.B. Friedman, K.H. Iwasa, R.J. Morell, and A.J. Ricci for valuable comments and critical reading of our manuscript. We also thank R. Leapman (NIBIB/NIH), T.B. Friedman (NIDCD/NIH) and Hitachi High Technologies Division (Gaithersburg, MD) for providing access to SEM instruments. This study was supported by the Deafness Research Foundation, by the National Organization for Hearing Research Foundation, and by NIDCD/NIH (DC008861).

References

- Adamek N, Coluccio LM, Geeves MA. Calcium sensitivity of the cross-bridge cycle of Myo1c, the adaptation motor in the inner ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5710–5715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710520105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed ZM, Goodyear R, Riazuddin S, Lagziel A, Legan PK, Behra M, Burgess SM, Lilley KS, Wilcox ER, Riazuddin S, Griffith AJ, Frolenkov GI, Belyantseva IA, Richardson GP, Friedman TB. The tip-link antigen, a protein associated with the transduction complex of sensory hair cells, is protocadherin-15. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7022–7034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assad JA, Corey DP. An active motor model for adaptation by vertebrate hair cells. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3291–3309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03291.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assad JA, Hacohen N, Corey DP. Voltage dependence of adaptation and active bundle movement in bullfrog saccular hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2918–2922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assad JA, Shepherd GM, Corey DP. Tip-link integrity and mechanical transduction in vertebrate hair cells. Neuron. 1991;7:985–994. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyantseva IA, Boger ET, Friedman TB. Myosin XVa localizes to the tips of inner ear sensory cell stereocilia and is essential for staircase formation of the hair bundle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13958–13963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334417100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belyantseva IA, Boger ET, Naz S, Frolenkov GI, Sellers JR, Ahmed ZM, Griffith AJ, Friedman TB. Myosin-XVa is required for tip localization of whirlin and differential elongation of hair-cell stereocilia. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:148–156. doi: 10.1038/ncb1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurg M, Evans MG, Hackney CM, Fettiplace R. A large-conductance calcium-selective mechanotransducer channel in mammalian cochlear hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10992–11000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2188-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozovic D, Hudspeth AJ. Hair-bundle movements elicited by transepithelial electrical stimulation of hair cells in the sacculus of the bullfrog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:958–963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337433100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung EL, Corey DP. Ca2+ changes the force sensitivity of the hair-cell transduction channel. Biophys J. 2006;90:124–139. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DP, Hudspeth AJ. Ionic basis of the receptor potential in a vertebrate hair cell. Nature. 1979;281:675–677. doi: 10.1038/281675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AC, Evans MG, Fettiplace R. Activation and adaptation of transducer currents in turtle hair cells. J Physiol. 1989;419:405–434. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AC, Evans MG, Fettiplace R. The actions of calcium on the mechano-electrical transducer current of turtle hair cells. J Physiol. 1991;434:369–398. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Wu X, Cheatham MA, Gao J, Zheng J, Anderson CT, Jia S, Wang X, Cheng WH, Sengupta S, He DZ, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for Mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk W, Holt JR, Shepherd GM, Corey DP. Calcium imaging of single stereocilia in hair cells: localization of transduction channels at both ends of tip links. Neuron. 1995;15:1311–1321. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont RA, Zhao YD, Holt JR, Bahler M, Gillespie PG. Myosin-I isozymes in neonatal rodent auditory and vestibular epithelia. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002;3:375–389. doi: 10.1007/s101620020049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettiplace R, Hackney CM. The sensory and motor roles of auditory hair cells. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:19–29. doi: 10.1038/nrn1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolenkov GI, Kalinec F, Tavartkiladze GA, Kachar B. Cochlear outer hair cell bending in an external electric field. Biophys J. 1997;73:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78198-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale JE, Marcotti W, Kennedy HJ, Kros CJ, Richardson GP. FM1-43 dye behaves as a permeant blocker of the hair-cell mechanotransducer channel. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7013–7025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07013.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler CD. A model of stereociliary tip-link stretches. Hear Res. 1993;65:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90203-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie PG, Cyr JL. Myosin-1c, the hair cell's adaptation motor. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:521–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.112842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear R, Richardson G. The ankle-link antigen: an epitope sensitive to calcium chelation associated with the hair-cell surface and the calycal processes of photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3761–3772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03761.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear RJ, Marcotti W, Kros CJ, Richardson GP. Development and properties of stereociliary link types in hair cells of the mouse cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 2005;485:75–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacohen N, Assad JA, Smith WJ, Corey DP. Regulation of tension on hair-cell transduction channels: displacement and calcium dependence. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3988–3997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-11-03988.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson T, Heintzelman MB, Santos-Sacchi J, Corey DP, Mooseker MS. Expression in Cochlea and Retina of Myosin Viia, the Gene-Product Defective in Usher Syndrome Type 1B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:9815–9819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme RH, Kiernan BW, Brown SD, Steel KP. Elongation of hair cell stereocilia is defective in the mouse mutant whirler. J Comp Neurol. 2002;450:94–102. doi: 10.1002/cne.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JR, Corey DP. Two mechanisms for transducer adaptation in vertebrate hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11730–11735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JR, Gillespie SK, Provance DW, Shah K, Shokat KM, Corey DP, Mercer JA, Gillespie PG. A chemical-genetic strategy implicates myosin-1c in adaptation by hair cells. Cell. 2002;108:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Hudspeth AJ. Mechanical relaxation of the hair bundle mediates adaptation in mechanoelectrical transduction by the bullfrog's saccular hair cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3064–3068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Hudspeth AJ. Compliance of the hair bundle associated with gating of mechanoelectrical transduction channels in the bullfrog's saccular hair cell. Neuron. 1988;1:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspeth AJ. Making an effort to listen: mechanical amplification in the ear. Neuron. 2008;59:530–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Falzarano PR, Simpson TH. Postnatal development of the hamster cochlea. II. Growth and differentiation of stereocilia bundles. J Comp Neurol. 1994;350:187–198. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Force generation by mammalian hair bundles supports a role in cochlear amplification. Nature. 2005;433:880–883. doi: 10.1038/nature03367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HJ, Evans MG, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Fast adaptation of mechanoelectrical transducer channels in mammalian cochlear hair cells. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:832–836. doi: 10.1038/nn1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov AS, Risler T, Hudspeth AJ. Coherent motion of stereocilia assures the concerted gating of hair-cell transduction channels. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nn1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kros CJ, Rusch A, Richardson GP. Mechano-electrical transducer currents in hair cells of the cultured neonatal mouse cochlea. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1992;249:185–193. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kros CJ, Marcotti W, van Netten SM, Self TJ, Libby RT, Brown SD, Richardson GP, Steel KP. Reduced climbing and increased slipping adaptation in cochlear hair cells of mice with Myo7a mutations. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:41–47. doi: 10.1038/nn784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, et al. Genetic mapping refines DFNB3 to 17p11.2, suggests multiple alleles of DFNB3, and supports homology to the mouse model shaker-2. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:904–915. doi: 10.1086/301786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Gao J, He DZ, Wu X, Jia S, Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. Cochlear mechanisms from a phylogenetic viewpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11736–11743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA. Evidence for an active process and a cochlear amplifier in nonmammals. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:541–549. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.2.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotti W, van Netten SM, Kros CJ. The aminoglycoside antibiotic dihydrostreptomycin rapidly enters mouse outer hair cells through the mechano-electrical transducer channels. J Physiol. 2005;567:505–521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.085951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Hudspeth AJ. Active hair-bundle movements can amplify a hair cell's response to oscillatory mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14306–14311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Bozovic D, Choe Y, Hudspeth AJ. Spontaneous oscillation by hair bundles of the bullfrog's sacculus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4533–4548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04533.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee J, Goodyear RJ, McMillan DR, Stauffer EA, Holt JR, Locke KG, Birch DG, Legan PK, White PC, Walsh EJ, Richardson GP. The very large G-protein-coupled receptor VLGR1: a component of the ankle link complex required for the normal development of auditory hair bundles. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6543–6553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0693-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers JR, MacDonald RB, Duggan A, Lenzi D, Standaert DG, Corwin JT, Corey DP. Lighting up the senses: FM1-43 loading of sensory cells through nonselective ion channels. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4054–4065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04054.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nal N, Ahmed ZM, Erkal E, Alper OM, Luleci G, Dinc O, Waryah AM, Ain Q, Tasneem S, Husnain T, Chattaraj P, Riazuddin S, Boger E, Ghosh M, Kabra M, Riazuddin S, Morell RJ, Friedman TB. Mutational spectrum of MYO15A: the large N-terminal extension of myosin XVA is required for hearing. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:1014–1019. doi: 10.1002/humu.20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak GD, Ratnayaka HS, Goodyear RJ, Richardson GP. Development of the hair bundle and mechanotransduction. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:597–608. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072392gn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles JO. A model for the mechanics of the stereociliar bundle on acousticolateral hair cells. Hear Res. 1993;68:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90120-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles JO, Comis SD, Osborne MP. Cross-links between stereocilia in the guinea pig organ of Corti, and their possible relation to sensory transduction. Hear Res. 1984;15:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst FJ, Fridell RA, Raphael Y, Saunders TL, Wang A, Liang Y, Morell RJ, Touchman JW, Lyons RH, Noben-Trauth K, Friedman TB, Camper SA. Correction of deafness in shaker-2 mice by an unconventional myosin in a BAC transgene. Science. 1998;280:1444–1447. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci A. Active hair bundle movements and the cochlear amplifier. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14:325–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Fettiplace R. Calcium permeation of the turtle hair cell mechanotransducer channel and its relation to the composition of endolymph. J Physiol. 1998;506(Pt 1):159–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.159bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Active hair bundle motion linked to fast transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7131–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07131.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Tonotopic variation in the conductance of the hair cell mechanotransducer channel. Neuron. 2003;40:983–990. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Kennedy HJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. The transduction channel filter in auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7831–7839. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1127-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Richardson GP. The morphology and physiology of hair cells in organotypic cultures of the mouse cochlea. Hear Res. 1987;31:9–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Richardson GP, Cody AR. Mechanosensitivity of mammalian auditory hair cells in vitro. Nature. 1986;321:517–519. doi: 10.1038/321517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzadzinska A, Schneider M, Noben-Trauth K, Bartles JR, Kachar B. Balanced levels of Espin are critical for stereociliary growth and length maintenance. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2005;62:157–165. doi: 10.1002/cm.20094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzadzinska AK, Schneider ME, Davies C, Riordan GP, Kachar B. An actin molecular treadmill and myosins maintain stereocilia functional architecture and self-renewal. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:887–897. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ME, Dose AC, Salles FT, Chang W, Erickson FL, Burnside B, Kachar B. A new compartment at stereocilia tips defined by spatial and temporal patterns of myosin IIIa expression. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10243–10252. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2812-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer EA, Holt JR. Sensory transduction and adaptation in inner and outer hair cells of the mouse auditory system. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:3360–3369. doi: 10.1152/jn.00914.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer EA, Scarborough JD, Hirono M, Miller ED, Shah K, Mercer JA, Holt JR, Gillespie PG. Fast adaptation in vestibular hair cells requires myosin-1c activity. Neuron. 2005;47:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanyan R, Belyantseva IA, Griffith AJ, Friedman TB, Frolenkov GI. Auditory mechanotransduction in the absence of functional myosin-XVa. J Physiol. 2006;576:801–808. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinevez JY, Julicher F, Martin P. Unifying the various incarnations of active hair-bundle motility by the vertebrate hair cell. Biophys J. 2007;93:4053–4067. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aken AF, Atiba-Davies M, Marcotti W, Goodyear RJ, Bryant JE, Richardson GP, Noben-Trauth K, Kros CJ. TRPML3 mutations cause impaired mechano-electrical transduction and depolarization by an inward-rectifier cation current in auditory hair cells of varitint-waddler mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:5403–5418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waguespack J, Salles FT, Kachar B, Ricci AJ. Stepwise morphological and functional maturation of mechanotransduction in rat outer hair cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13890–13902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2159-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YC, Ricci AJ, Fettiplace R. Two components of transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2171–2181. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yamoah EN, Gillespie PG. Regeneration of broken tip links and restoration of mechanical transduction in hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15469–15474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.