Abstract

Input to sensory thalamic nuclei can be classified as either driver or modulator, based on whether or not the information conveyed determines basic postsynaptic receptive field properties. Here we demonstrate that this distinction can also be applied to inputs received by non-sensory thalamic areas. Using flavoprotein autofluorescence (FA) imaging we developed two slice preparations that contain the afferents to the anterodorsal thalamic nucleus (AD) from the lateral mammillary body (LM) and the cortical afferents arriving through the internal capsule, respectively. We examined the synaptic properties of these inputs and found that the mammillothalamic pathway exhibits paired-pulse depression, lack of a metabotropic glutamate component, and an all-or-none response pattern, which are all signatures of a driver pathway. On the other hand, the cortical input exhibits graded paired-pulse facilitation and the capacity to activate metabotropic glutamatergic responses, all features of a modulatory pathway. Our results extend the notion of driving and modulating inputs to the AD, indicating that it is a first order relay nucleus and suggesting that these criteria may be general to the whole of thalamus.

Keywords: anterior thalamus, thalamus, drive, cortex, metabotropic glutamate receptor glutamate, synaptic

INTRODUCTION

The thalamus receives input from a multitude of cortical and subcortical areas and relays this to cortex, representing the sole source of information flow to the latter. Afferents to the main sensory thalamic nuclei can be divided into drivers, which determine the main postsynaptic receptive field properties and carry the main information to be relayed to cortex, and modulators, which affect the way driver information is relayed (Sherman and Guillery, 1998, 2006). Driver inputs exhibit such synaptic features as a strong, all-or-none response pattern, paired-pulse depression, and the capacity to activate only ionotropic glutamate receptors. Modulators, on the other hand, produce relatively weak, graded responses with paired-pulse facilitation and can activate both ionotropic and metabotropic receptors (Sherman and Guillery, 2006). Individual thalamic nuclei, on the basis of whether they relay driving information from subcortical areas to the cortex or from one cortical area to another, have been categorized as first order (FO) or higher order (HO) nuclei, respectively (Guillery, 1995; Sherman and Guillery, 1998, 2006).

Whereas a great deal is known about the origin of driver and modulating input in most traditional sensory thalamic nuclei (Guillery, Feig, and Van Lieshout, 2001; Wang, Eisenback and Bickford, 2002; Li, Guido and Bickford, 2003; Reichova and Sherman, 2004, Van Horn and Sherman, 2007; Lee and Sherman, 2008), this is not the case for other nuclei. It needs to be noted that the distinction between “traditional sensory” and “other” thalamic nuclei is primarily a semantic one. By “traditional sensory nuclei”, we mean nuclei such as the lateral geniculate or ventral posterior medial nuclei, which have been the main experimental models to study thalamus. One of the ‘other’ nuclei is the anterodorsal nucleus (AD), perhaps the most prominent of the anterior thalamic nuclei. Its subcortical afferents arrive from LM of the hypothalamus (Watanabe and Kawana, 1980; Hayakawa and Zyo, 1989; Shibata, 1992), whereas cortical afferents arrive primarily from the parasubiculum, postsubiculum, and the parts of the retrosplenial cortex (van Groen and Wyss, 1990a, b; Shibata and Naito, 2005), the latter two also being the major target of AD efferents (Shibata, 1993a; van Groen and Wyss, 1995, 2003). In addition to their involvement in some limbic functions (Sziklas and Petrides, 1999; Celerier, Ognard, Decorte and Beracochea, 2000; Wolff, Loukavenko, Will and Dalrymple-Alford, 2008), AD cells have been found to respond to head direction activity, similarly to cells in cortical areas associated with AD (Sharp, 1996; Goodridge and Taube, 1997; Hargreaves, Yoganarasimha and Knierim, 2007). We wished to determine if the synaptic properties of various inputs to AD conformed to the driver/modulator model developed for the traditional sensory thalamic relays, thereby extending this concept to thalamus more generally, or if some other pattern might exist. To do so, we developed two new slice preparations in the mouse: one that contains the pathway between LM and AD, and the other that contains the severed corticothalamic axons terminating into AD through the internal capsule. We thus examined the synaptic responses of AD cells following the stimulation of their subcortical and cortical afferent pathways. Our data show that the mammillary input to AD possesses the profile characteristics of a driving pathway, whereas cortical input arriving through the internal capsule appears to be of an exclusively modulatory nature, a pattern seen in the traditional sensory thalamic nuclei.

Methods

Slice preparation

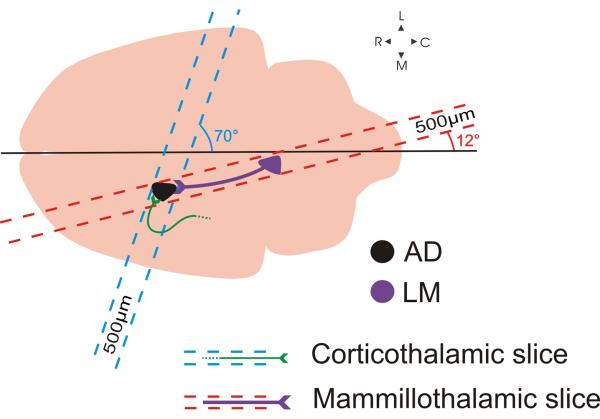

BALB/c mice (ages 14-18 days) were anaesthetized with isoflurane and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and placed in chilled (0-4°C), oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) slicing solution containing the following (in mM): 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 11 glucose and 206 sucrose. The mammillothalamic slice preparation was prepared as follows: Brains were blocked at a 12° angle from the midline over the right hemisphere (Figure 1) and the blocked side was glued onto a vibratome platform (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Slices were cut at 500μm off-parasagittal in that orientation, thus preserving most of the connectivity between LM and AD (see Results). The trajectory of the corticofugal fibers terminating in AD is such that the inclusion of the whole pathway in a single slice was not possible. We therefore had to develop a slice that would contain as much of the corticothalamic axons as possible so that to allow us to maximize the distance between the stimulation site and the imaged/recorded site in AD. For the corticothalamic slice preparation, brains were blocked at a 70° off-coronal angle (Figure 1), the blocked area was glued to the vibratome platform, and slices were cut at 500μm in that orientation. Once cut, slices from either preparation were placed in warm (32°C) oxygenated ACSF (containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1MgCl2, 2CaCl2, 25NaHCO3, 25 glucose) for 30 minutes and were then allowed to recover for at least an additional 30 minutes, at room temperature, before being used. Once in the recording chamber, slices were continuously perfused with oxygenated ACSF.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the blocking angles used to generate the two slice preparations. Mammillothalamic slice: Taking the midline as a reference, a 12° cut was made to parallel the route of the mammillothalamic tract and a single, 500μm-thick, slice was vibratomed. The slice containing the severed cortical axons into AD was prepared by blocking the brain at a 70° angle and by cutting a single 500μm-thick slice. Abbreviations: AD: Anterodorsal thalamic nucleus, LM: Lateral mammillary body

Flavoprotein autofluorescence imaging

The viability of connectivity in the two slice preparations was assessed using imaging of flavoprotein autofluorescence (FA), details of which can be found in Llano, Theyel, Mallik, Sherman and Issa (2009). Briefly, FA captures green light (520-560nm) emitted by mitochondrial flavoproteins in the presence of blue light (450-490nm) in conditions of cellular metabolic activity (see Shibuki, Hishida, Murakami, Kudoh, Kawaguchi, Watanabe, Kouuchi and Tanaka, 2003). This method allows the detection of cellular activation (through the elevated levels of mitochondrial green light emissions) once a connected pre-synaptic area has been stimulated. FA was carried out on a fluorescent light-equipped microscope (Axioscop 2FS, Carl Zeiss Instruments) connected with a QImage Retiga-SRV camera (QImaging Corporation, Surrey, BC, Canada).

For the assessment of the mammillothalamic and corticothalamic slices, LM and the dorsal internal capsule were respectively stimulated using a bipolar concentric electrode (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) while simultaneously imaging the postsynaptic activation in the anterior thalamus. Electrical stimulation consisted of a current injection train (50-250μA, 20Hz) over 1 second. FA activity was monitored over that period of time in addition to 1 second prior to stimulation and 12 seconds following stimulation. Fluorescence images were acquired at 2.5-10 frames per second (integration time of 150-300 ms). The optical image was generated as a function of the Δf/f ratio of the baseline autofluorescence of the slice prior to stimulation subtracted from the autofluorescence of the slice over the period of stimulation (Δf) divided by baseline (f).

In some FA experiments, LM was stimulated through the photo-uncaging of caged glutamate. For these experiments, nitroindolinyl-caged glutamate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the recirculating ACSF (0.4mM) and a UV laser beam (DPSS Laser, Santa Clara, CA) was used to locally photolyse the caged compound (Shepherd, Pologruto and Svoboda, 2003; Lam and Sherman, 2005; 2007; Lam, Nelson and Sherman, 2006). The laser beam had an intensity of 20-80mW and gave off a 10ms, 20-pulse, light stimulus (355-nm wavelength, frequency-tripled Nd:YVO4, 100-kHZ pulse repetition rate). For photo-uncaging FA experiments, the Δf/f ratio was calculated by subtracting baseline autofluorescence from autofluorescence immediately after the last laser pulse (Δf) and by then dividing the result by baseline (f). FA analyses for both electrical and glutamate photo-uncaging stimulation were carried out using a custom-made software written in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Electrophysiology

Whole cell patch clamp recordings in current clamp mode were carried out using a visualized slice setup under a DIC-equipped Axioscop 2FS microscope (Carl Zeiss Instruments, Jena, Germany) and with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The pipettes used for the recordings were pulled from 1.5mm borosilicate glass capillaries and were filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM): 117 K-gluconate, 13 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.07 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.4 Na-GTP; 7.3pH, 290mosm). Pipette input resistances varied between 4-8MΩ. Data were digitized on a Digidata 1200 board and stored on a computer. Analyses of the acquired traces were performed in ClampFit (Axon) software. In order to evoke synaptic responses in AD cells, electric stimulation of their afferent pathways was delivered through the same bipolar electrodes as the ones used for FA. For the examination of short-term synaptic plasticity, we used a protocol that consisted of four 0.1ms-long pulses at a frequency of 10Hz. In doing so, we used the minimal stimulation intensity required to elicit an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP). This was done in order to minimize the potential spread of current around the stimulation area, which could potentially result in the recruitment of other AD afferents, thus contaminating the responses recorded from the nucleus. Progressively higher intensities were used to test for a graded or an all-or-none response profile (see Results). The stimulation intensities that were used typically varied between 10 and 350μA. For the examination of metabotropic glutamate responses, we employed a high-frequency stimulation (HFS) protocol that delivered 0.1ms-long pulses at 125Hz over 800ms.

All experimental protocols (including FA ones) were carried out in the presence of GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonists (SR95531, 50nM and CGP46381, 50nM, respectively). In addition, in order to isolate any metabotropic responses that might be present, HFS was applied in the presence of NMDA and AMPA antagonists (MK-801, 40μM and DNQX, 50μM, respectively). Finally, the mGluR1 receptor antagonist LY367385 (40μM) was used to block metabotropic responses, when present.

Results

Viability of slice connectivity

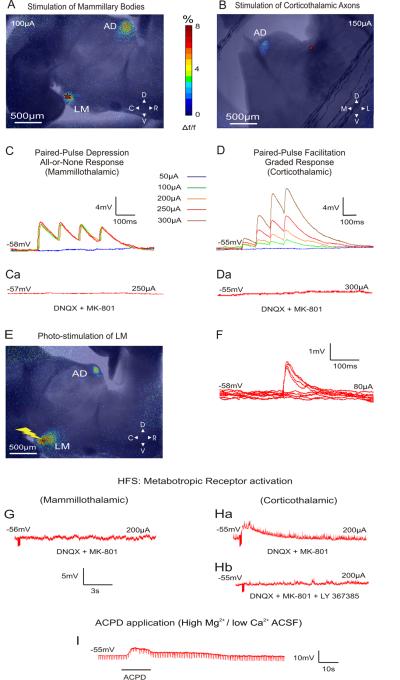

Figures 2A,B show the FA images during electrical stimulation of LM and the corticothalamic axons terminating in AD, respectively. In both cases, an activation can be seen in AD remote from the stimulation site. An activation of AD was also seen when the stimulation of LM was carried out through the photo-uncaging of caged glutamate (Figure 2E). We thus conclude that the imaged AD activation was the direct outcome of mammillary stimulation and not the product of any activated axons of passage.

Figure 2.

A, B: Examples of superimposed bright field and AF images illustrating the areas of activation during the stimulation of the mammillary bodies and the corticothalamic axons of AD, respectively (red stars indicate the area of stimulation). Stimulation in A resulted in paired-pulse depression (C) whereas stimulation in B resulted in paired-pulse facilitation (D). The color panel represents the % of FA signal change from pre-stimulation baseline. C: Demonstration of the all-or-none response profile in AD following mammillary stimulation of increasing intensity. D: Demonstration of the graded response profile in AD following corticothalamic axon stimulation of increasing intensity. Ca, Da: Responses in both types of synapses were blocked when MK801 and DNQX (NMDA and AMPA antagonist respectively) were applied to the bath. All traces represent the average of 10 sweeps. E. Example of a superimposed AF and bright field image illustrating the areas of activation during glutamate photo-uncaging (yellow bolt) over the mammillary bodies. The activation color scheme is the same as in A and B. F: Minimal stimulation intensity for depressing synapses was defined as the intensity that resulted in 50% failures in producing an EPSP. G. HFS (125Hz) of LM in the presence of ionotropic receptor antagonists resulted in no changes in the membrane potential of AD cells. H: Stimulation of the corticothalamic axons under these conditions resulted in a slow and prolonged membrane depolarization of AD cells (a) that could be blocked with LY367385 (mGluR1 antagonist) (b). I. Membrane depolarization seen after the application of ACPD in the slice in the presence of high

Mg2+ / low Ca2+ ACSF.

Driver vs Modulator response signatures

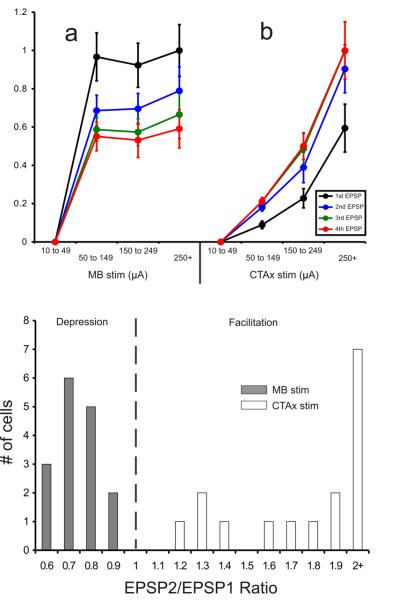

We recorded from 32 AD cells with resting membrane potentials of −53.1±5.1 mV (uncorrected for a ∼-10mV gap potential) and input resistances of 235.6±157.8 MΩ. For the 16 AD cells recorded in the mammillary slice, low frequency (10-20Hz) stimulation of LM that exceeded 50μA evoked EPSPs in the recorded AD cells. These EPSPs showed paired-pulse depression (mean EPSP2/EPSP1 ratio: 0.73 ±0.1; see Figures 2C and 3B) and an all-or-none activation pattern (see Figures 2C and 3Aa). That is, in order for EPSPs to be produced, a certain threshold of stimulation intensity had to be reached, after which further increases in stimulation intensity did not significantly increase the amplitude of the EPSPs. These EPSPs could be completely blocked by introducing ionotropic receptor (AMPA and NMDA) antagonists (DNQX, 50μM and MK801, 40μM, respectively) in the bath (Figure 2Ca). In the presence of these antagonists, HFS (120Hz) did not produce any changes in cell membrane potential, indicating a lack of involvement of metabotropic receptors evoked by the mammillothalamic synapse (Figure 2G).

Figure 3.

A: Normalized EPSP amplitudes recorded in AD following the stimulation of LM (a) and the corticothalamic axons (b) at different intensities. The data is plotted as a function of each EPSP (1st to 4th) for each intensity bin. Stimulation of LM (n=16) resulted in an all-or-none response pattern: Once the current intensity threshold for the generation of EPSPs is reached, further increases in current intensity do not produce larger EPSPs. Contrary to that, increases in the intensity of stimulation of the corticothalamic axons (n=16) resulted in increases in the amplitude of the EPSPs recorded in AD. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. B: Distribution of the paired-pulse effects in the two pathways plotted as the ratio of the amplitude of the 2nd EPSP divided by the amplitude of the 1st EPSP, as generated at minimal stimulation intensity. The mammillothalamic synapse produced ratios below 1 (depression) while the corticothalamic synapse produced ratios above 1 (facilitation). The EPSP2/EPSP1 ratios of the two populations were significantly different (p<.001, t-test). Abbreviations: LM: Lateral mammillary body, CTAx: Corticothalamic axons.

The synaptic properties revealed by stimulation of the dorsal internal capsule stimulation in 16 other AD cells in the other slice configuration were dramatically different from those of LM. The EPSPs produced from such stimulation showed paired-pulse facilitation (mean EPSP2/EPSP1 ratio: 2.53 ±1.34; see Figures 2D and 3Ab, B], and they showed a graded activation pattern, meaning that their amplitude demonstrated a positive correlation with the intensity of the injected current (Figures 2D, 3Ab). The evoked EPSPs generated by low frequency activation of the cortical axons were blocked by ionotropic receptor antagonists (Figure 2Da). However, in the presence of these antagonists, HFS produced a prolonged depolarization (9 sec, 4mV) of the cells' membrane potential (Figure 2Ha). This depolarization could be blocked by the mGluR1 antagonist LY367385 (Figure 2Hb). In order to examine whether the metabotropic responses could be postsynaptic (i.e., the result of metabotropic receptors in the recorded AD cell) and not pre-synaptic (i.e. the result of pre-synaptic metabotropic receptors on the corticothalamic axons and/or terminals), we applied the general mGluR agonist ACPD (final concentration: 65μM) in the presence of high Mg2+ / low Ca2+ ACSF, which blocks synaptic transmission. This control was carried out on five cells, three in the mammillothalamic and two in the corticothalamic preparation. The membrane depolarization for all five cells produced by ACPD in these conditions (Figure 2I), demonstrated that the metabotropic effect was postsynaptic to the recorded cell (mean depolarization for AD cells sampled in the mammillothalamic slice: 11.6±1.5mV, and in the corticothalamic slice: 10±2.8mV).

Discussion

The examination of the synaptic properties of the mammillothalamic and corticothalamic afferents of AD revealed that the two pathways possess different functional profiles. The mammillothalamic input to AD was found to possess driver characteristics such as a lack of metabotropic receptor activation and large, all-or-none, EPSPs that manifest synaptic depression. These synaptic features reflect a high probability of transmitter release and a fast postsynaptic relay of information (Sherman and Guillery, 2006). On the other hand, the generation of graded, facilitating, EPSPs and the activation of metabotropic receptors on AD cells following corticothalamic stimulation reflect a longer, yet overall weaker, influence onto these cells. Such an influence most likely operates in modulating the way driving input is relayed (Sherman and Guillery, 2006).

The pattern of cortical and subcortical synaptic relationships of AD, therefore, resembles that of the sensory FO thalamic nuclei, such as the lateral geniculate, the ventral posterior, and the ventral medial geniculate nuclei (Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Sherman and Guillery, 2006; Lee and Sherman, 2008). These nuclei receive their driving input from subcortical centers, whereas their cortical input arrives through axons of cortical cells in layer 6 and possesses modulatory synaptic characteristics. Even though HO sensory thalamic nuclei also receive modulatory input from cortical layer 6, they receive driving input that arises from cortical layer 5 (Guillery, 1995; Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Sherman and Guillery, 2006). In the present study, we stimulated the whole extent of the severed cortical axons reaching AD through the internal capsule, thus activating axons potentially originating in either of these layers. The absence of driver-like responses leads us to the conclusion that the cortical input to AD arises exclusively from layer 6, which agrees with previous anatomical reports from the rat (Van Groen and Wyss, 1990a).

However, not all cortical afferents of AD arrive through the traditional internal capsular route. Axons of cortical cells also reach AD through the fornix (Shibata, 1998), a fiber tract that carries cortical and hippocampal input into areas of the hypothalamus, including the mammillary bodies (Swanson and Cowan, 1977; Donovan and Wyss, 1983; Shibata, 1989). This input uses an unusual route to reach the thalamus, namely via an anterior and medial trajectory, thus apparently avoiding a transit through the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN), something that is not the case for most, if not all, other corticothalamic pathways, regardless of whether they innervate TRN or not. Because of the geometry and close proximity to AD of corticothalamic axons passing through the fornix, we could not isolate this corticothalamic input for stimulation. Thus while our data does not completely rule out the possibility that AD receives some driving input from layer 5 of cortex via the fornix route, other data does seem to do so. That is, Shibata (1998) reported that the multiple cortical areas retrogradely labeled from tracer injections into AD labeled only layer 6 neurons and not those in layer 5. Since layer 5 is the source of driver input to HO nuclei (Sherman and Guillery, 2006), and none seem to be involved in the cortical projection to AD, we conclude that AD is an FO nucleus with its subcortical driving input from the mammillary bodies.

Cells in AD and its associated cortical areas (as well as the mammillary bodies) appear to fire in accordance to the organism's head direction movements (Sharp, 1996; Goodridge and Taube, 1997; Stackman and Taube, 1998; Hargreaves, Yoganarasimha and Knierim, 2007). Previous reports combining lesions with electrophysiological recordings demonstrate that head direction activity in postsubiculum is dependant on AD but not vice versa (Goodridge and Taube, 1997). More specifically, lesions in AD result in the abolition of head direction related activity in the postsubiculum, whereas lesions of postsubiculum affect only secondary features of head direction related activity in AD, such as the range of directional firing. This suggests that driving information regarding head movement is not arriving to AD from cortex but that AD relays such information to cortex instead. This agrees with our results showing that cortical information coming into AD is of a modulatory nature and suggests that the driving head direction information reaching postsubiculum through AD may be arriving to the latter from the mammillary region.

Overall our results demonstrate that the distinction between driving and modulating inputs is not restricted exclusively to traditional sensory thalamic nuclei, but it may apply more broadly to thalamus. Understanding the functional organization of a transthalamic pathway cannot be achieved by examining the relative numerical strength of its afferents, given that these can exert significantly diverse postsynaptic effects of equally diverse functional importance. A better understanding of the above could be therefore offered through the identification of the origin of driving afferents in a thalamic area, a method the significance of which has been largely overlooked. This could represent a potentially useful tool in understanding not only the functional role of transthalamic pathways but, by extension, that of the cortical areas to which they project.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their invaluable help and technical advice in carrying out all experimental procedures (in alphabetical order): Dr Joseph A. Beatty, Elise N. Covic, Dr Y.W. Lam, Dr Charles C. Lee, Dr Dan A. Llano, Brian B. Theyel and Dr Carmen Varela. Funding was obtained from NIH/NEI Grant EY03038 and NIH/NIDCD Grant DC008794 to S.M.S.

REFERENCES

- Celerier A, Ognard R, Decorte L, Beracochea D. Deficits of spatial and non-spatial memory and of auditory fear conditioning following anterior thalamic lesions in mice: comparison with chronic alcohol consumption. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(7):2575–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan MK, Wyss JM. Evidence for some collateralization between cortical and diencephalic efferent axons of the rat subicular cortex. Brain Res. 1983;24(2592):181–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge JP, Taube JS. Interaction between the Postsubiculum and Anterior Thalamus in the generation of head direction cell activity. J Neurosci. 1997;17(23):9315–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09315.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW. Anatomical evidence concerning the role of the thalamus in corticocortical communication: a brief review. J Anat. 1995;187(3):583–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW, Feig SL, Van Lieshout DP. Connections of higher order visual relays in the thalamus: a study of corticothalamic pathways in cats. J Comp Neurol. 2001;438(1):66–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves EL, Yoganarasinha D, Knierim JJ. Cohesiveness of spatial and directional representations recorded from neural ensembles in the anterior thalamus, parasubiculum, medial entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2007;17(9):826–41. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Zyo K. Retrograde double-labeling study of the mammillothalamic and the mammillotegmental projections in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;1(2841):1–11. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YW, Nelson CS, Sherman SM. Mapping of the functional interconnections between thalamic reticular neurons using photostimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(5):2593–600. doi: 10.1152/jn.00555.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YW, Sherman SM. Mapping by laser photostimulation of connections between the thalamic reticular and ventral posterior lateral nuclei in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(4):2472–83. doi: 10.1152/jn.00206.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YW, Sherman SM. Different topography of the reticulothalmic inputs to first- and higher-order somatosensory thalamic relays revealed using photostimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98(5):2903–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.00782.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Sherman SM. Synaptic properties of thalamic and intracortical inputs to layer 4 of the first- and higher-order cortical areas in the auditory and somatosensory systems. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100(1):317–26. doi: 10.1152/jn.90391.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guido W, Bickford ME. Two distinct types of corticothalamic EPSPs and their contribution to short-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(5):3429–40. doi: 10.1152/jn.00456.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano DA, Theyel BB, Mallik AK, Sherman SM, Issa NP. Rapid and sensitive mapping of long range connections in vitro using flavoprotein autofluorescence imaging combined with laser photostimulation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009 doi: 10.1152/jn.91291.2008. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichova I, Sherman SM. Somatosensory corticothalamic projections: distinguishing drivers from modulators. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92(4):2185–97. doi: 10.1152/jn.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PE. Multiple spatial/behavioural correlates for cells in the rat postsubiculum: Multiple regression analysis and comparison to other hippocampal areas. Cerebral Cortex. 1996;6(2):238–59. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM, Pologruto TA, Svoboda K. Circuit analysis of experience-dependent plasticity in the developing rat barrel cortex. Neuron. 2003;24(382):277–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. On the actions that one nerve cell can have on another: distinguishing “drivers” from “modulators”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;9(9512):7121–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. Exploring the Thalamus. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H. Descending projections to the mammillary nuclei in the rat, as studied by retrograde and anterograde transport of wheat germ agglutinin-horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1989;22(2854):436–52. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H. Topographic organization of subcortical projections to the anterior thalamic nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;1(3231):117–27. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H. Efferent projections from the anterior thalamic nuclei to the cingulate cortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993a;22(3304):533–42. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H. Organization of projections of rat retrosplenial cortex to the anterior thalamic nuclei. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;(10):3210–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H, Naito J. Organization of anterior cingulate and frontal cortical projections to the anterior and laterodorsal thalamic nuclei in the rat. Brain Res. 2005;12(10591):93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuki K, Hishida R, Murakami H, Kudoh M, Kawaguchi T, Watanabe M, Watanabe S, Kouuchi T, Tanaka R. Dynamic imaging of somatosensory cortical activity in the rat visualized by flavoprotein autofluorescence. J Physiol. 2003;15(549Pt 3):919–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackman RW, Taube JS. Firing properties of the rat lateral mammillary single units: head direction, head pitch, and angular head velocity. J Neurosci. 1998;18(21):9020–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-09020.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Cowan WM. An autoradiographic study of the organization of the efferent connections of the hippocampal formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1977;1(1721):49–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sziklas V, Petrides M. The effects of lesions to the anterior thalamic nuclei on object-place associations in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(2):559–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Wyss JM. The connections of presubiculum and parasubiculum in the rat. Brain Res. 1990a;518:227–243. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90976-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Wyss JM. The postsubicular cortex in the rat: characterization of the fourth region of the subicular cortex and its connections. Brain Res. 1990b;529:165–177. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90824-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Wyss JM. Projections from the anterodorsal and anteroventral nucleus of the thalamus to the limbic cortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;7(3584):584–604. doi: 10.1002/cne.903580411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Wyss JM. Connections of the retrosplenial granular b cortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2003;463(3):249–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.10757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn SC, Sherman SM. Fewer driver synapses in higher order than in first order thalamic relays. Neuroscience. 2007;146(1):463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Eisenback MA, Bickford ME. Relative distribution of synapses in the pulvinar nucleus of the cat: implications regarding the “driver/modulator” theory of thalamic function. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454(4):482–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Kawana E. A horseradish peroxidase study on the mammillothalamic tract in the rat. Acta Anat (Basel) 1980;108(3):394–401. doi: 10.1159/000145322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Loukavenko EA, Will BE, Dalrymple-Alford JC. The extended hippocampal-diencephalic memory system: enriched housing promotes recovery of the flexible use of spatial representations after anterior thalamic lesions. Hippocampus. 2008;(10):996–1007. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]