Abstract

In renal cell carcinoma (RCC), HLA class I downregulation has been found in about 40% of the lesions examined. Since only scanty information is available about the molecular basis of these defects, we have investigated the mechanism(s) underlying HLA class I antigen down-regulation or loss in six RCC cell lines. Five of them express HLA class I antigens although at various levels; on the other hand, HLA class I antigens are not detectable on the remaining cell line, the RCC52 cell line, belonging to a sarcomatoid subtype, even following incubation with IFN-γ. β2-microglobulin (β2m) was not detected in RCC52 cells. Surprisingly, RCC52 cells harbor two mutations in the β2m genes in exon 1: a single G deletion (delG) in codon 6, which introduces a premature stop at codon 7, and a CT dinucleotide deletion (delCT), which leads to a premature stop at codon 55. Analysis of eight clonal sublines isolated from the RCC52 cell line showed that the two β2m gene mutations are carried separately by RCC52 cell subpopulations. The delG/delCT double mutations were detected in two sublines with a fibroblast-like morphology, while the delCT mutation was detected in the remaining six sublines with an epithelial cell morphology. Furthermore, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the β2m gene at STR D15S-209 was found only in the epithelioid subpopulation, indicating loss of one copy of chromosome 15. Immunostaining results of the tumor lesion from which the cell line RCC52 was originated were consistent with the phenotyping/molecular findings of the cultured cells. This is the first example of the coexistence of distinct β2m defects in two different tumor subpopulations of a RCC, where loss of one copy of chromosome 15 occurs in one of the subpopulations with total HLA class I antigen loss.

Keywords: HLA class I, β2-Microglobulin, Renal cell carcinoma, Sarcomatoid subtype, Cell lines

Introduction

It has been known for some time that tumor cells can have impaired HLA class I antigen expression during the course of tumor progression [1–3]. HLA class I antigen downregulation or loss often occurs in tumor cells when the primary tumor breaks the basal membrane, invades the surrounding tissues, and/or starts to metastasize to regional lymph nodes or distant organs [4, 5]. Tumor-induced immune modulation of surrounding tissue including sentinel lymph nodes plays an important role in this invasive/metastatic process. Since HLA class I molecules present tumor antigen-derived peptides to host CTLs, altered HLA class I antigen expression by malignant cells constitute an efficient mechanism to escape HLA class I-restricted, tumor antigen-specific T cell immune responses. Therefore, it is important to characterize these altered phenotypes in tumor samples, analyze the underlying mechanisms and select patients suitable for immunotherapy.

RCC, one of the most common malignancies of the adult kidney, accounts for approximately 3% of all adult cancers in the Western countries [6]. About one-third of patients present with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and about 40% of patients treated for their primary tumors will relapse with metastatic disease [7]. In Taiwan, patients suffering from RCC account for less than 1.42% and patients who die of RCC fall into 0.37% of all major cancers that are being considered [8]. Over the past few years, general defects in DC function, increase in circulating regulatory T cell numbers and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment have been identified in patients with RCC [9], although RCC is considered one of the few immunogenic human neoplasms. Thus far, only limited information is available regarding HLA class I antigen expression in RCC, and the analysis of HLA class I antigen expression in primary and metastatic RCC lesions as well as RCC-derived cell lines has relied on cytofluorometry and immunohistochemistry [2, 10–12]. In these studies, about 40% of the analyzed RCC lesions showed partial loss of HLA class I molecules [2, 13], while 6% of the tumors showed total HLA class I antigen loss [13]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been reported regarding the mechanism(s) underlying HLA class I antigen downregulation or loss in RCC. In this communication, we describe a RCC cell line of the sarcomatoid subtype with total HLA class I antigen loss caused by the coexistence of two distinct mutations in the two β2m encoding genes.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human RCC cell lines (HH050, HH244, HH332, HOKN-9, RCC52 and RCC98) were derived from surgically removed primary RCC lesions. Their characteristics are listed in Table 1. The RCC cell lines and the B lymphoid cell line LG2 were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, MD), containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) which had been previously heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. The NP69 cell line [14], derived from normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cells immortalized by SV40 large T antigen, was kindly provided by Dr. S.-W. Tsao, Department of Anatomy, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. This cell line was maintained in keratinocyte-SFM medium containing l-glutamine, human epidermal growth factor and bovine pituitary extract (as specified by the supplier, Gibco-BRL), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Clonal sublines were isolated from the RCC52 cell line by limiting dilution. Briefly, cells were seeded at a theoretical number, i.e. 0.5 cell/100 μl complete RPMI-1640 medium, onto each well of a 96-well microtiter-plate (NUNC, Roskilde, Denmark). Those wells with growth from an obvious single cell were selected and expanded gradually.

Table 1.

Diagnosis and clinical information of patients from whom the six RCC cell lines were established

| Parameter | Cell line designation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCC52 | RCC98 | HH050 | HH244 | HH332 | HOKN-9 | |||||||

| Histopathologic type | Sarcomatoidb (with residual clear cell carcinoma found) | Chromophobe cell carcinoma | Papillary renal cell carcinoma | Tubular carcinoma | Clear cell carcinoma | Clear cell carcinoma | ||||||

| Fulman grade | 3 | 2 | –a | – | – | – | ||||||

| Stage | IIIb | II | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Clinical status | DOD | DOD | DOD | DOD | DOD | DOD | ||||||

| Genotype of HLA class Ic | A2 | A11 | A2 | A24 | A2 | A3 | A1 | A24 | A24 | A29 | A2 | A24 (9) |

| B46 | B60 (40) | B35 | B46 | B62 | B35 | B8 | B35 | B51 | B58 | B35 | B46 | |

| Cw1 | Cw7 | Cw1 | Cw9 (3) | C3 | C4 | C4 | C7 | C7 | C14 | C1 | C3 | |

| Initiator(s) of cell line | C-K. Chuang and S-K. Liao, Taiwan | C-K. Chung and S-K. Liao, Taiwan | S. K. Nayak, USA | S. K. Nayak, USA | S. K. Nayak, USA | Y. Yoshida and K. Hasumi, Japan | ||||||

DOD died of disease

Unknown

Original diagnosis was sarcomatoid RCC, and after careful evaluation of tumor sections in this study it was found to be a mixture of sarcomatoid and clear cell RCC with a dominant sarcomatoid element. Of note is that the RCC52 cell line established in vitro composed exclusively of sarcomaoid cells

Results were generated from this study (see text)

IFN-γ

Recombinant human IFN-γ was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. Mineapolis, MN.

Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies

The mAb W6/32, which recognizes the properly folded HLA-A,-B,-C,-E,-F,-G heavy chains associated with β2m [15, 16], was purchased from BD-PharMingen, San Diego, CA. The mAb HC-10 which recognizes a determinant expressed on β2m-free HLA-A10, -A28, -A29, -A30, -A31, -A32 and -A33 heavy chains and on all β2m-free HLA-B and C heavy chains [17, 18], the mAb HCA-2 which recognizes a determinant expressed on β2m-free HLA-A (except-A24), -B7301 and -G heavy chains [19], the β2m-specific mAb L368 [20], the LMP2-specific mAb SY-1 [21], the LMP7-specific mAb HB2 [21], the TAP1-specific mAb NOB1 [22], the TAP2-specific mAb NOB2, and the HLA-DR, DQ, DP antigen-specific mAb LGII-612.14 [22] were previously developed and characterized. Fluorescein-isothioyanate conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies were purchased from DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark).

Cytofluorometric analysis

Cell surface staining and intracellular staining with mAb were performed as described previously [23]. Reactions in which the primary antibody was replaced with PBS, purified normal mouse IgG (NMIgG) or an isotype-matched normal mouse IgG were used as specificity controls. Stained cells were analyzed with a FACscan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Co., Oxnard, CA). Results were expressed as % stained cells and as relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

HLA class I genotyping

Micro SSP™ HLA class I locus specific genotyping was performed utilizing the reagents from One Lambda, Inc. (Canoga Park, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells utilizing the TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was performed with mAbs using the primers for β2m, LMP2, LMP7, TAP1, TAP2 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, as a loading control, Table 2). The following PCR conditions were used: 40 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1.5 min and 72°C for 2 min with a 10 min extension after the last cycle. The PCR products were then fractionated on a 1% agarose gel (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The resulting bands were read by a densitometer, ChemiSmart 3000 equipped with the Bioprofil 1D++ software (Vilber Lournat, Marne-la-Vallee, France). The amount of transcript of each experimental group was estimated after normalization with the density of the resulting GAPDH band of the same group.

Table 2.

RT-PCR primers used in this study

| Gene | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| β2m | GGGCATTCCTGAAGCTGACA TGCGGCATCTTCAAACCTCC |

424 |

| LMP2 | TTGTGATGGGTTCTGATTCCCG CAG AGCAATAGCGTCTGTGG |

449 |

| LMP7 | TCGCCTTCAAGTTCCAGCATGG CCAACCATCTTCCTTCATGTGG |

542 |

| TAP1 | TCTCCTCTCTTGGGGAGATG GAGACATGATGTTACCTGTCTG |

273 |

| TAP2 | CTCCTCGTTGCCGGCTTCT TCAGCTCCCCTGTCTTAGTC |

298 |

| GAPDH | TTCATTGACCTCAACTACAT GAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTT |

469 |

PCR and sequence analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from RCC98 and RCC52 cells utilizing the mammalian genomic DNA extraction miniprep kit (Sigma, Dorset, England) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was carried out using the β2m gene-specific primers forward 744F: 5′-CTCTAACCTGGCACTGCGTC-3′ and reverse 468R: 5′-TGAGAAGGAAGTCACGGAGC-3′ to amplify the entire open reading frame (ORF). PCR products were then electrophoresed as mentioned above. The bands with the predicted size of 283 bp were extracted from the gel and purified using the DNA/RNA extraction kit (Viogene, Illkirch Cedex, France). Direct sequencing of purified PCR products was performed by the Biopolymer using an ABI-PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Mission biotech, Taipei, Taiwan).

Immunohistochemistry

Sections (5 μm in thickness) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded RCC tumor blocks obtained from patients with RCC were processed in the Pathology Department, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan. Prior to immunostaining, the deparaffinized slides were subjected to an antigen retrieval process by dipping the slides in a beaker containing 0.01 M sodium citrate (pH 6.0) in a boiling state on a hotplate. Following a 20 min incubation, the beaker was removed from the hotplate and let cool down at room temperature for 20 min. Slides were washed once in PBS and stained with mAbs using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) method (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis of the β2m gene

LOH analysis of β2m was performed as previously described [24] with slight modifications. Briefly, purified genomic DNA (200 ng) was subjected to PCR amplification using two pairs of primers (D15S-126 and D15S-209) specific to the short tandem repeat (STR) markers [24] flanking the β2m gene at 15q21. The amplification parameters were the following: 95°C for 10 min; 95°C, 30 s, 54°C, 30 s, 72°C, 30 s for 5 cycles; 95°C, 30 s, 56°C, 30 s, 72°C, 30 s for 30 cycles, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were then fractionated on a 4% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The intensity of the staining was determined and analyzed by ImageJ (Research Services Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD). LOH is reported when a LOH index, (Intensity of tumor allele one/Intensity of tumor allele two)/(Intensity of normal allele one/Intensity of normal allele two), is less than 50%.

Results

HLA class I and class II antigen expression on the six RCC cell lines analyzed

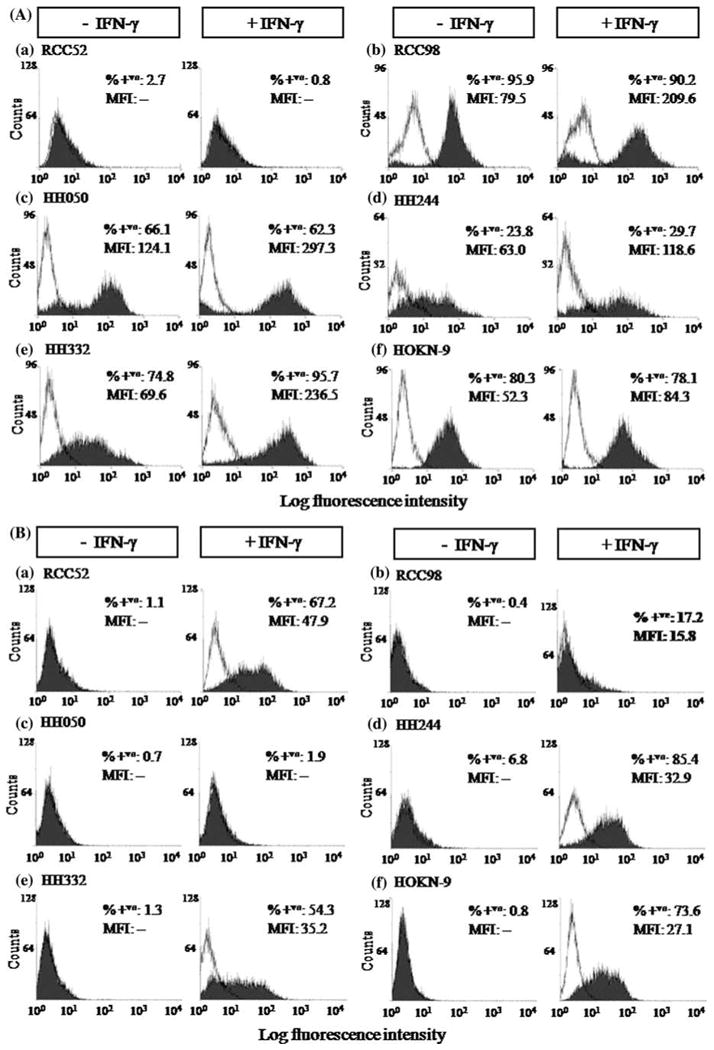

Cytofluorometric analysis of the RCC cell lines HH050, HH244, HH332, HOKN-9, RCC52 and RCC98 stained with the HLA-A, -B, -C, -E, -F, -G antigen-specific mAb W6/32 showed that, with the exception of the RCC52 cell line, all the others were stained, although with differences in percentage of stained cells and in staining intensity. The results are presented as histograms and as bars in Figs. 1, 2, respectively. Surface HLA class I antigen expression was enhanced, although to a variable extent, on all the 5 RCC cell lines following a 48 h incubation at 37°C with IFN-γ (300 U/ml). The expression of HLA class I antigens was enhanced on HH332 cells in terms of percentage of stained cells and of staining intensity. In contrast, approximately 80, 60 and 24% of the cell population in the cell lines HOKN-9, HH050 and HH244, respectively, was resistant to modulation by IFN-γ (Fig. 1a). However, MFI reflective of surface HLA class I antigen density increased in these three cell lines, indicating that in the latter cell lines some of the cells were IFN-γ responsive. Furthermore, HLA class I antigens were not induced on the cell line RCC52, following IFN-γ treatment.

Fig. 1.

Differential surface HLA class I (a) and HLA class II (b) antigen expression on the RCC cell lines, RCC52 (a) RCC98 (b) HH050 (c) HH244 (d) HH332 (e) and HOKN-9 (f) under basal conditions (−IFN-γ) and following incubation with IFN-γ (300 U/ml) at 37°C for 48 h (+IFN-γ) in vitro. The results presented in the histograms were determined by cytofluorometric analysis of cells stained with HLA class I antigen-specific mAb W6/32 and with HLA class II antigen-specific mAb LGII-612.14. Experiments were repeated three times with each cell line; similar results were obtained

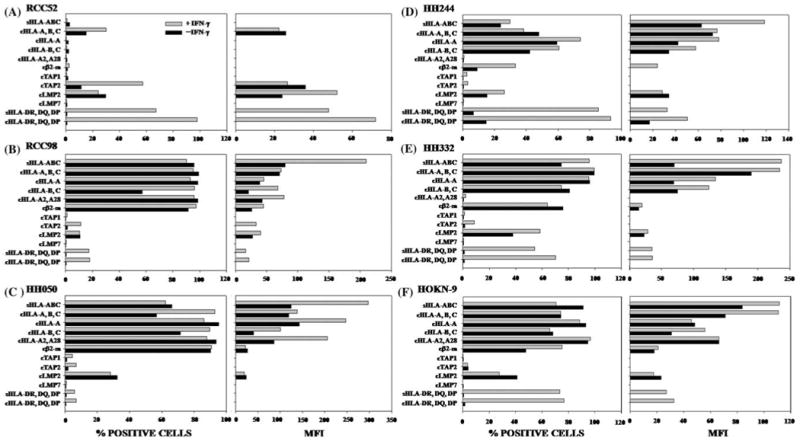

Fig. 2.

HLA class I and APM components expression by RCC cell lines a RCC52, b RCC98, c HH050, d HH244, e HH332 and f HOKN-9. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 h with or without IFN-γ (300 U/ml). Surface and intracellular expression of the molecules was determined by cytofluorometric analysis. Results are expressed as % stained cells on the left frame and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on the right frame. The symbols “s” and “c” at the prefix of the indicated antigen stand for surface and cytoplasmic antigens, respectively. *HC stands for HLA heavy chains. The values of MFI are not indicated, when the stained cells is less than 10%

To monitor the susceptibility of the six RCC cell lines to modulation by IFN-γ, they were tested for HLA class II antigen expression following a 48 h incubation at 37°C with IFN-γ (300 U/ml). Cytofluorometric analysis of these cell lines under basal conditions showed that at most 7% of cells were stained by the HLA-DR, DQ, DP antigen-specific mAb LGII-612.14 (Fig. 1b). However, with the exception of the HH050 cell line, the percentage of stained cells markedly increased in all the cell lines following a 48 h incubation at 37°C with IFN-γ (300 U/ml). Genotyping results of HLA class I antigens on the six RCC cell lines are summarized in Table 1.

Intracellular expression of HLA class I heavy chain, β2m, TAP subunits and LMP subunits in the RCC cell lines analyzed

To investigate the mechanism(s) underlying the differential HLA class I antigens surface expression by the six RCC cell lines, we tested their cytoplasmic expression of HLA class I heavy chains, β2m, and APM components. As shown in Fig. 2, HLA-A, HLA-A2 and HLA-B,-C heavy chains as well as β2m were not detected in the cytoplasm of RCC52 cells. Unlike LMP2, which was detectable albeit at a low level in all six RCC cell lines, LMP7 and TAP1 had a low expression or were not detectable in all the cell lines tested. These findings reflected neither the low reactivity of the mAb preparations used nor the low sensitivity of the assay system used, since the same mAb preparations stained other cell lines such as cultured human B lymphoid cell line.

Expression of β2m, TAP and LMP mRNAs in the RCC cell lines analyzed

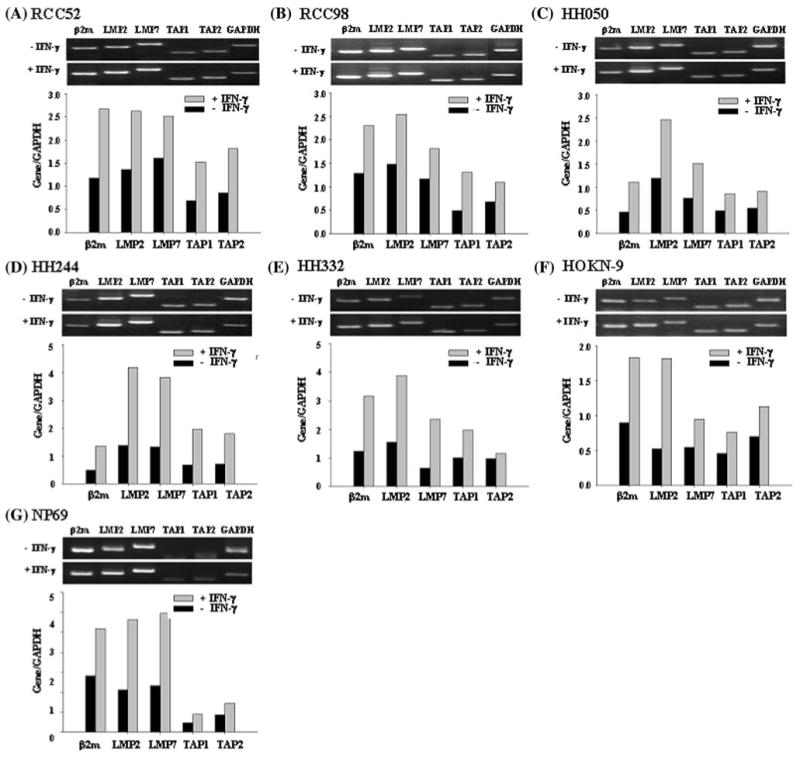

To determine whether lack of expression or down-regulation of some MHC class I-associated APM components in the six RCC cell lines reflected transcriptional defects at the messenger level, using semi-quantitative RT-PCR methods we measured the levels of β2m, TAP1, TAP2, LMP2 and LMP7 mRNA in the six RCC cell lines under basal conditions and following a 48 h incubation at 37°C with IFN-γ (300 U/ml). The NP69 cell line (immortalized normal epithelial cells) supposed to express most normal epithelial characteristics served as a positive control. Like the NP69 cell line (Fig. 3g), all the six RCC cell lines express detectable levels of β2m, TAP1, TAP2, LMP2 and LMP7 mRNAs under basal conditions; the level of each component mRNA was augmented in all the cell lines following incubation with IFN-γ (Fig. 3a–f).

Fig. 3.

Upregulation by IFN-γ of β2m, LMP2, LMP7, TAP1 and TAP2 transcripts in the RCC cell lines a RCC52, b RCC98, c HH050, d HH244, e HH332, f HOKN-9 and in the control g NP69 cell line. Total RNA from cells cultured with or without IFN-γ (300 U/ml) at 37°C for 48 h was isolated and transcribed. β2m, LMP2, LMP7, TAP1 and TAP2 transcripts were amplified by PCR with appropriate primer pairs. GAPDH was included as an internal control. The PCR products were run on 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The upper frame is banding patterns in agarose gel and the lower one is the result of quantification. GAPDH was also included as an internal loading control. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Experiments were repeated three times with each cell line; similar results were obtained

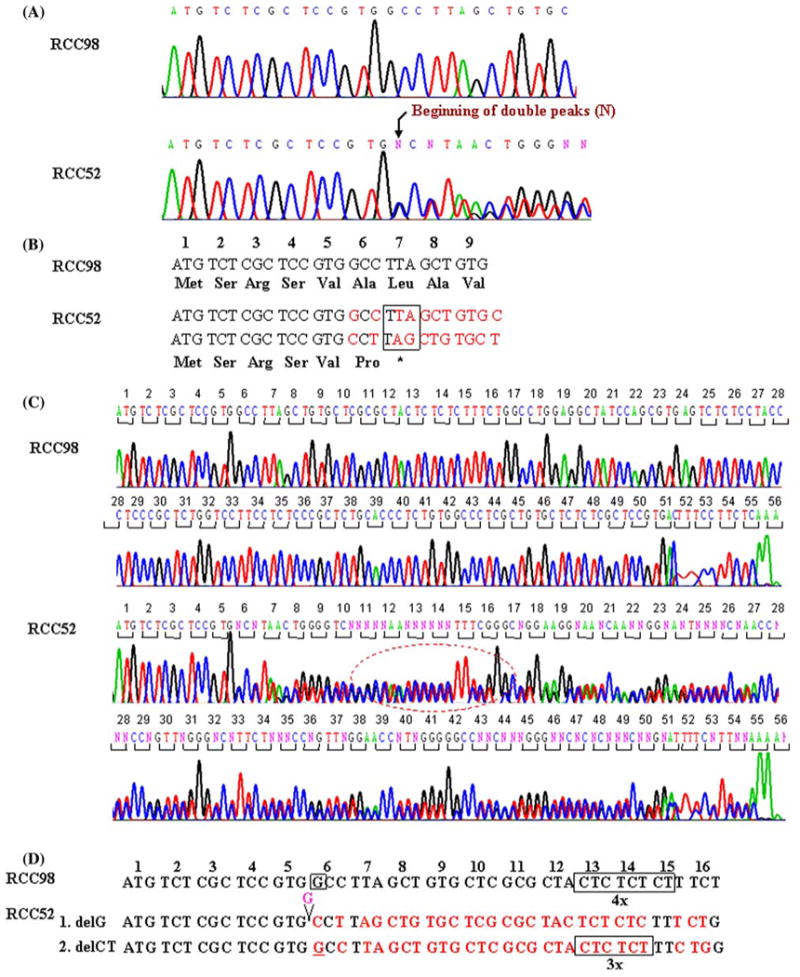

Identification of β2m gene mutations in the RCC52 cell line

The phenotype of RCC52 cells, i.e. total HLA class I antigen loss, which is not modulated by IFN-γ, is compatible with defects in the assembly of HLA class I heavy chain with β2m because of lack of expression of functional β2m. To determine whether abnormalities in β2m were caused by mutation(s) in the encoding genes, genomic DNA was isolated from RCC52 cells and subjected to sequencing. DNA isolated from RCC98 cells was used as a control. Analysis of sequence chromotograms for the RCC52 cell DNA identified two mutations. A single G deletion (delG) in exon 1 changed codon 6 from GCC to CCT, and consequently, introduced a premature stop at codon 7 (Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, a CT dinucleotide deletion (delCT) within codon 13 to 15 (Fig. 4c, d) introduced another premature stop at codon 55. The pattern of double peaks within codon 13 to 15 suggests that the two mutations are located in distinct copies of chromosome 15. Therefore, it appears that distinct β2m gene mutations in the β2m encoding alleles coexist in the RCC52 cell populations analyzed.

Fig. 4.

Identification of two frame-shift mutations in the β2m gene in RCC52 cells. a The sequence chromatograms of the β2m gene ORFs derived from RCC98 (served as a wild type) and RCC52 cells are shown. The reading frame-shifts at codon 6 and the reading stops prematurely at codon 7 in RCC52 cells (bracket, lower panel), as a result of single G deletion. b Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of the β2m gene exon 1 (codon 1 to 7) from RCC98 and RCC52 cells are shown. The mis-sense codon-deduced amino acid is typed in bold. c The sequence chromatograms of the β2m gene ORFs derived from RCC98 and RCC52 cells are shown. The reading frame-shift at codon 13 to 15 (in circle) and the reading stops prematurely at codon 55 in RCC52 cells, as a result of deletion of a CT dinucleotide. d Nucleotide sequences of the β2m gene exon 1 (codon 1 to 16) from RCC98 and RCC52 cells are shown for comparison

Distinct β2m gene mutations carried by subpopulations in the RCC52 cell line

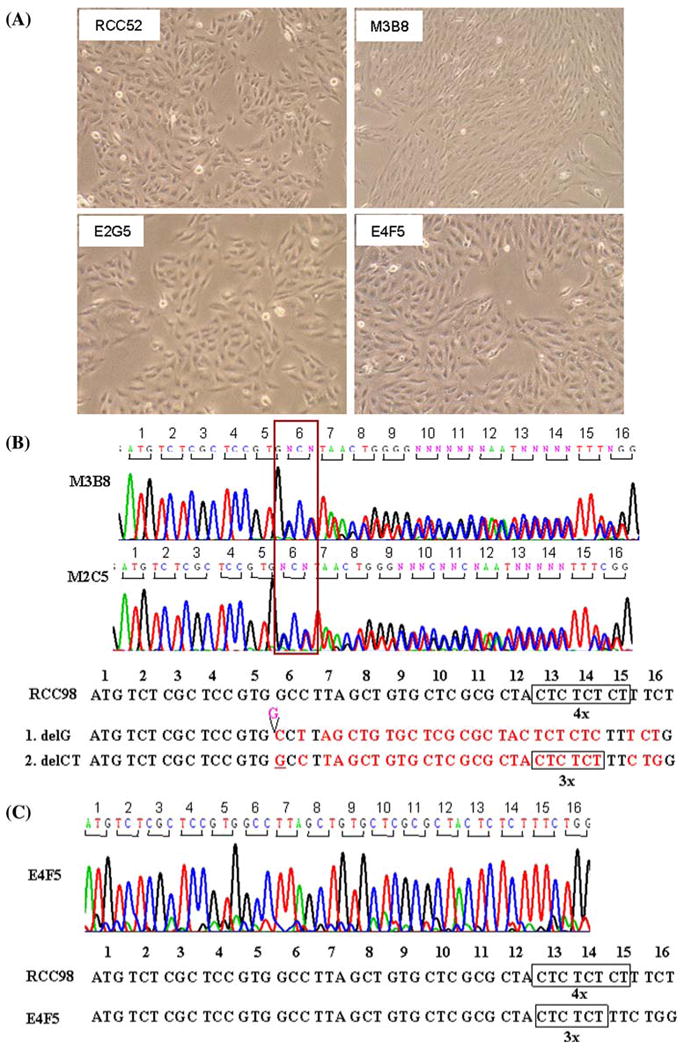

To corroborate the possibility that the distinct mutations in the β2m encoding alleles coexist in the same RCC cell population, eight clonal sublines were established from RCC52 cells by limiting dilution. Among them, M2C5 and M3B8 displayed a spindle or fibroblast-like cellular morphology, whereas E1A5, E2G5, E3D2, E3D4, E4D7 and E4F5 exhibited an epithelioid shape (Fig. 5a). Like the parental RCC52 cell line, none of these eight sublines expressed surface HLA class I antigens (results not shown). Each subline was examined for its β2m gene mutation(s). The delG/delCT double mutations were detected in the sublines M2C5 and M3B8 with fibroblast-like cell morphology (Fig. 5b), while the delCT single mutation was detected in the other six sublines with epithelioid cell morphology (Fig. 5c). No single delG mutation was detected in any of the sublines examined. Therefore, the delCT alone represented the predominant β2m gene mutation in RCC52 cells and was carried by the subpopulation with epithelioid cell morphology.

Fig. 5.

Monolayer culture morphology and sequence abnormalities of the β2m genes of the RCC52 cell line and its representative clonal sublines. a RCC52, parental cells showing predominantly epithelioid cell morphology; clonal sublines E2G5 and E4F5 displaying epithelioid cell morphology; and clonal subline M3B8 showing fibroblast-like cell morphology. Sequence chromatograms of the β2m gene show the double mutations, delG and delCT in the clonal sublines M2C5 and M3B8 with fibroblast-like morphology b and the single mutation in the clonal sublines E3D2, E1A5, E2G5, E3D4, E4D7 and E4F5 with epithelioid cell morphology. c The representative sequence chromatogram of the clonal subline E4F5 is shown, The sequence chromatogram of RCC98 cells which contains quadruplicate CT dinucleotide is shown for comparison. Original magnification, ×100

Lack of β2m and HLA class I antigen expression in the sarcomatoid component in the tumor lesion from which the RCC52 cell line was originated

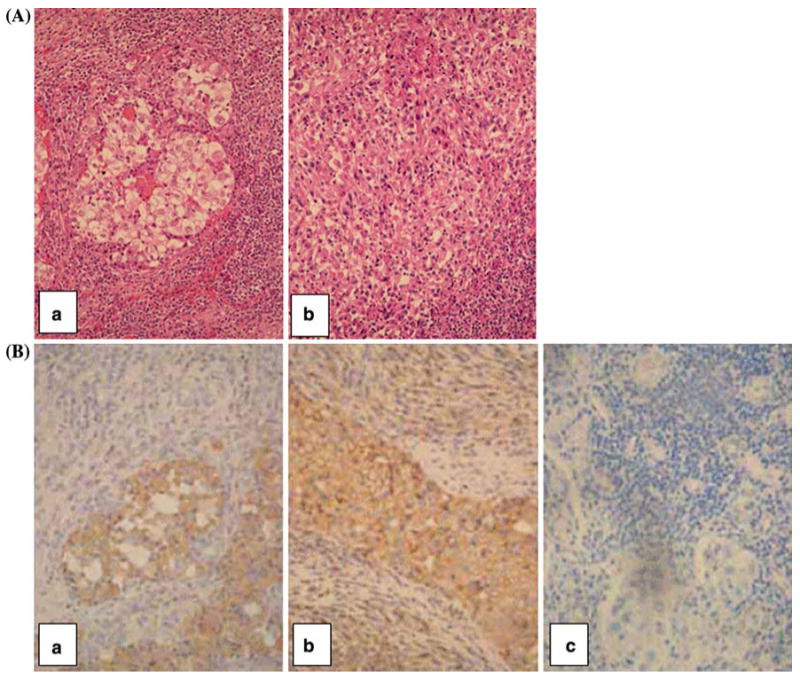

To exclude the possibility that the lack of HLA class I antigen expression by the cultured RCC52 cells was caused by an in vitro artifact associated with their in vitro culture, the surgically removed lesion from which the cell line had been established was tested for β2m and HLA class I heavy chain expression. H&E staining of tumor sections showed that the majority of tumor cells were sarcomatoid, while only small areas exhibited clear cell morphology coexisting with sarcomatoid cells (Fig. 6A(a), (b)). Immunostaining with the β2m-specific mAb L368 showed positive staining with moderate intensity in the clear cell component; on the other hand, no staining or only faint staining was detected in the sarcomatoid component of the malignant lesion (Fig. 6B(a)). Immunostaining with the HLA class I heavy chain-specific mAb HC-10 resulted in moderate to strong surface and cytoplasmic staining of the clear cell component, and in weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining of the sarcomatoid component of the malignant tumor (Fig. 6B(b)). The observed immunoreactivity was specific, since no staining was detected when tumor tissue sections were incubated with NMIgG (Fig. 6B(c)) or matched-isotype control in place of primary mAb (not shown).

Fig. 6.

H&E and immunohistochemical staining of a RCC lesion from which the RCC52 cell line was established.a H&E staining shows the mixed clear cell (central area) and sarcomatoid RCC (a) and sarcomatoid RCC representing a majority of the tumor population (b).b Immunostaining with the β2m-specific mAb L368 resulted in the staining of clear cell component, but did not stain or barely stained the sarcomatoid component of the tumor tissue (a). Immunostaining with the HLA class I heavy chain-specific mAb HC-10 resulted in moderate to strong staining of the surface and cytoplasm of the clear cell component and in weak to moderate staining of the cytoplasm of the sarcomatoid component of the tumor tissue (b). No staining of the tumor tissue section was detected with normal mouse IgG (NMIgG) (c). Original magnification, ×400

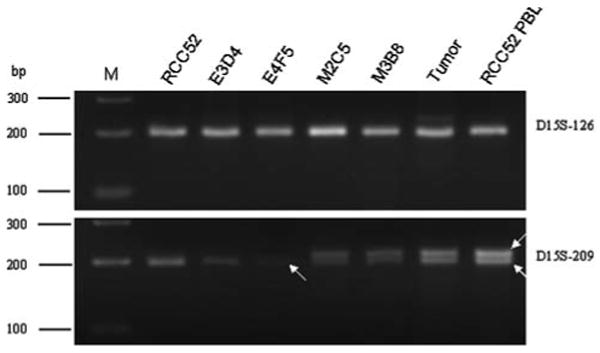

Detection of LOH at STR D15S-209 of the β2m gene only in RCC52 epithelioid sublines

To characterize the mechanisms underlying the defects leading to β2m loss, fibroblast-like (M2C5 and M3B8) and epithelioid (E3D4 and E4F5) sublines of the RCC52 cell line were analyzed for their status of heterozygosity at 15q21 where the β2m gene has been mapped [25]. Genomic DNAs extracted from RCC52 patient's PBL and surgically removed tumor specimen served as controls. As shown in Fig. 7, homozygosity (with one band) at STR D15S-126 is present in both PBL control and tumor specimen, as well as in the four RCC52 sublines and the RCC52 parental cell line. On the other hand, LOH at STR D15S-209 (with a single band) is evident for the parental RCC52 cell line and two RCC52 epithelioid sublines, compared with retention of heterozygosity (ROH) (with two bands) at STR D15S-209 in the fibroblast-like sublines, the PBL control and tumor specimen. The ROH at STR D15S-209 in the tumor specimen was likely due to the presence of stromal fibroblast cells, endothelial cells and leucocytes in situ, cell populations died out during the establishment of the parental RCC52 cell line in culture. Based on these results, LOH was observed only in the epithelioid subpopulations of RCC52 cells and may reflect loss of one copy of chromosome 15 in these cells.

Fig. 7.

LOH analysis of chromosome 15 STR markers D15S-126 and D15S-209 flanking the β2m gene on the RCC52 cell line, its epithelioid E3D4 and E4F5 sublines and its fibroblast-like M2C5 and M3B8 sublines. Genomic DNAs prepared from RCC52 patient's tumor specimen and peripheral blood lymphocytes (RCC52 PBL) were analyzed in parallel with those extracted from the four RCC52 clonal sublines. Two white arrows indicate two separate alleles, i.e. retention of heterozygosity (ROH), while a single arrow indicates one allele, i.e. LOH. M: DNA size ladder in base pairs (bp)

Discussion

In this study, cytofluorometric analysis of six RCC cell lines stained with mAbs revealed defective HLA class I expression in all of them. Cell surface expression of HLA class I antigens was not detected on the cell line RCC52 under basal conditions and was not induced by incubation with IFN-γ. The total HLA class I antigen loss is caused by abnormalities at the translational level in β2m, a subunit crucial for proper HLA class I assembly and transport [3, 26]. As a result, HLA class I heavy chains, although synthesized by RCC52 cells, failed to travel to the cell surface and were retained intracellularly, as indicated by the intracellular staining with mAb HC-10 and mAb TP25.99.8.4. The lack of association of HLA class I heavy chains with β2m accounts for the lack of staining of RCC52 cells by HLA-A2,-A28-specific mAb CR11-351 and HLA-B,-C-specific mAb B1.23.1. The latter two mAbs recognize epitopes which are expressed only on properly conformed, β2m-associated HLA class I heavy chains.

Our findings of the molecular defects in the β2m gene of RCC52 cells are summarized in Table 3. The defects in the β2m gene were identified to be two frame-shift mutations, i.e. one G deletion (delG) in codon 6, resulting in the introduction of a premature stop at codon 7, and a CT dinucleotide deletion (delCT) within codon 13 to 15, leading to another premature stop at codon 55. The two mutations are in different copies of chromosome 15. Interestingly, the delCT mutation was carried solely in the epithelial-like RCC52 subpopulation, while the delG/delCT double mutations were harbored in the spindle or fibroblast-like RCC52 subpopulation. Of note is that no single delG was detected in any of the eight RCC52 sublines. Our LOH results indicate that the epithelioid RCC52 cells has more extensive genomic instability than the fibroblast-like cells, since the former carry one small deletion at β2m and one large mutation (LOH) at chromosome 15, whereas the latter has two separate small mutations at β2m with heterozygosity still maintained. The more advanced stage of epithelioid cells is supported by their markedly faster growth rate in vitro and readily growth in SCID mice (data not shown), as well as by their predominance in the tumor lesion, compared with fibroblast-like cells. Presently, it is not clear whether the two morphologically distinct types of cells are two unrelated tumor populations evolved together at the tumor site or were in the process of a mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) when the disease progressed. Thus far, MET is rare compared with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which has been an indication for the progression of carcinoma towards dedifferentiation and a more malignant status in other tumor types such as breast carcinoma [27, 28]. Previously, in the HLA class I loss variants of colorectal tumors examined, a number of distinct β2m gene mutations including delCT were found to coexist in a given neoplasm and to be closely associated with microsatellite instability [29]. Our RCC52 case is another example of heterogeneous β2m gene mutations in sarcomatoid tumor cell subpopulations within one sarcomatoid/clear RCC lesion that leads to a homogenous total HLA class I antigen loss phenotype. Whether this phenomenon reflects a relationship between tumor cell progression and chromosome 15 instability remains to be determined.

Table 3.

Genetic abnormalities in the β2m locus of the RCC52 epithelioid and fibroblast-like clonal sublines

| Morphological type of subline | Mutation(s) in the coding region of the β2m gene | Heterozygosity status at chromosome 15q21 STRs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D15S-126 | D15S-209 | ||

| Epithelioid | delCT in codon 13 to 15 | Homozygous | LOH |

| Fibroblast-like | delG in codon 6 and delCT in codon 13 to 15 | Homozygous | ROH |

STRs short tandem repeats, LOH loss of heterozygosity, ROH retention of heterozygosity

The site of the delCT mutation is within the CT dinucleotide repeats in the β2m gene, known as a mutation hotspot which has also been found in colon carcinoma [28] and melanoma cells [30]. Mutations in this dinucleotide repeat region have been identified in greater than 75% of tumor cells with total HLA class I antigen loss [31]. A recent report suggests that the hotspot β2m gene mutations in melanoma tend to be associated with T cell-based immunotherapy-related selective pressure [32]. It is noteworthy that although patient donating the RCC52 cell line has never received any forms of T cell-based immunotherapy, RCC is one type of tumor in which immunological events are believed to play a role in the clinical course of the disease.

Among the five HLA class I-positive RCC cell lines, HH050, HH244 and HOKN-9, are populated with tumor cell variants that are resistant to IFN-γ-modulated enhancement of HLA class I antigen expression, since the percent positive cells in each of these cell lines remained unchanged as those cultured in the absence of IFN-γ (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, in these cell lines some cells are IFN-γ sensitive, as indicated by increase in MFI in cells following the IFN-γ treatment. At present, we do not know whether these findings have in vivo relevance. If this is the case, our findings may have implications for selecting patients for T cell-based immunotherapy, in which IFN-γ-induced, HLA class I-presented T cell epitopes often serve as the primary signal to stimulate a tumor antigen-specific immune response. On the other hand, the IFN-γ-resistant tumor cell variants may represent a subpopulation that has escaped from IFN-γ-modulated CTL response in the course of the malignancy.

The tumor lesion from which the RCC52 cell line was originated was pathologically classified as a sarcomatoid subtype. Our immunohistochemical analysis of the surgically removed tumor tissue revealed that the sarcomatoid component, representing the major tumor subpopulation, was not stained by β2m-specific mAb L368 (Fig. 6B(a)), while both the sarcomatoid component and the clear cell component (the minor subpopulation) were stained by the HLA class I heavy chain-specific mAb HC-10 (Fig. 6B(b)). These results parallel those we have obtained by analyzing the RCC52 cell line. In fact, HLA class I antigen loss can be demonstrated by the lack of reactivity with mAb W6/32 of RCC52 cells tested as early as in the 8th in vitro passage (data not shown), suggesting that the clear cell subpopulation prepared from the lesion failed to grow along with the sarcomatoid one during the course of the cell line establishment.

Sarcomatoid RCC, to which RCC52 cells belong, is a subtype that could be transformed from any of RCC types including clear cell, chromophobe, papillary and collecting duct carcinomas [33]. As compared with non-sarcomatoid RCCs, sarcomatoid RCCs have been associated with poor prognosis, higher metastatic rate, local recurrence rate, and shorter survival intervals, although constituting only 1 to 5% of the total RCC cases [34, 35]. We here have only examined one sarcomatoid RCC cell line and its corresponding tumor lesion. The six RCC cell lines we have analyzed were representative of at least four major RCC types. Therefore, we are fully aware of the limitation in drawing a definitive conclusion concerning the frequency of specific defect(s) for a given RCC type before more tumor lesions and cell lines are investigated. The total HLA class I loss identified here in the sarcomatoid RCC subtype is in line with a previous study in which another sarcomatoid RCC cell line known as UOK123 was found to have lost total HLA class I expression; however, no information was given regarding its underlying mechanism [11]. Therefore, given the notorious clinical feature of sarcomatoid RCC, our study may have provided useful pilot data regarding the molecular defects in this subtype that lead to a total HLA class I loss. Further investigation on this sarcomatoid RCC subtype to determine if the total HLA class I loss as well as the type and sites of the identified β2m gene mutations are specific for this subtype of RCC is warranted.

In conclusion, total HLA class I loss in the sarcomatoid RCC52 cell line was determined to be caused by the coexistence of two distinct mutations in the β2m genes, the mechanism being described for the first time in RCC. The resulting information may also help to improve the selection of patients with RCC to be enrolled in trials [36–38].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Tzu-Ju Chang, Chen-Chen Kang, and Hung-Chang Chen for their excellent technical assistance. Special thanks are also expressed to late Dr. Shanka K Nayak, Hoag Cancer Center, Newport Beach, CA, for providing the HH050, HH244 and HH332 cell lines and to Dr. Yukiyo Yoshida, Hasumi International Research Foundation, Tokyo Laboratory, Suginami, Japan, for the HOKN-9 cell line to be used in this study. This study was supported in part by the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC93-2314-B-182-022; NSC94-2314-B-182-060) and the Chang Gung Medical Research Fund (CMRP-363) awarded to S-K.L, by the NSC grant NSC97-2923-B-007-002-MY2 to C-C.C, and by National Cancer Institute, DHHS (USA) PHS grants RO1CA67108 and RO1CA110249 to S.F.

Contributor Information

Chin-Hsuan Hsieh, Graduate Institute of Biomedical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Ya-Jan Hsu, Graduate Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Chien-Chung Chang, Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan.

Hsin-Chun Liu, Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan.

Kun-Lung Chuang, Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan; Division of Uro-Oncology, Department of Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Cheng-Keng Chuang, Division of Uro-Oncology, Department of Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

See-Tong Pang, Division of Uro-Oncology, Department of Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Kenichiro Hasumi, Hasumi International Research Foundation, Tokyo Laboratory, Suginami, Tokyo, Japan.

Soldano Ferrone, Cancer Institute, Departments of Surgery, of Immunology and of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Shuen-Kuei Liao, Graduate Institute of Biomedical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan; Graduate Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan; Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan; Tumor Immunology Laboratory, Chang Gung University, 259 Wen-Hua 1st Road, Kweishan, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan, e-mail: liaosk@mail.cgu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens, immune surveillance, and tumor immune escape. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:346–355. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins D, Ferrone S, Schmahl GE, Störkel S, Seliger B. Down-regulation of HLA class I antigen processing molecules: an immune escape mechanism of renal cell carcinoma? J Urol. 2004;171:885–889. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000094807.95420.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrone S, Marincola FM. Loss of HLA class I antigens by melanoma cells: molecular mechanisms, functional significance and clinical relevance. Immunol Today. 1995;16:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Fisher ER. The interrelationship of hematogenous and lymphatic tumor cell dissemination: an experimental study. Rev Inst Nac Cancerol (Mex) 1966;19:576–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cochran AJ, Huang RR, Lee J, Itakura E, Leong SP, Essner R. Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:659–670. doi: 10.1038/nri1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer registry annual report 2002. Republic of China (Taiwan): Department of Health, Taipei, The executive Yuan, Republic of China; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dekernion JB. Renal tumors. In: Walsh PC, Gittesm RF, Perlmutter AD, Stamey TA, editors. Campbell's Urology. 6th. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1993. pp. 1294–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uzzo RG, Novick AC, Bukowski RM, Finke JH. Molecular mechanisms of immune dysfunction in renal cell carcinoma. In: Bukoowski RM, Novick AC, editors. Renal cell carcinoma Molecular biology, Immunology and clinical management. Humana Press; Yotowa: 2000. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordon-Cardo C, Fuks Z, Drobnjak M, Moreno C, Eisenbach L, Feldman M. Expression of HLA-A, B, C antigens on primary and metastatic tumor cell populations of human carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6372–6380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakobsen MK, Restifo NP, Cohen PA, Marincola FM, Cheshire LB, Linehan WM, Rosenberg SA, Alexander RB. Defective major histocompatibility complex class I expression in a sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma cell line. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1995;17:222–228. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199505000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamura H, Honma I, Torigoe T, Asanuma H, Sato N, Tsukamoto T. Down-regulation of HLA class I antigen is an independent prognostic factor for clear cell renal carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177:1269–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero JM, Aptsiauri N, Vazquez F, Cozar JM, Canton J, Cabrera T, Tallada M, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. Analysis of the expression of HLA class I, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in primary tumors from patients with localized and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Tissue Antigens. 2006;68:303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao SW, Wang X, Liu Y, Cheung YC, Feng H, Zheng Z, Wong N, Yuen PW, Lo AK, Wong YC, Huang DP. Establishment of two immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell lines using SV40 large T and HPV16E6/E7 viral oncogenes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1590:150–158. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnstable CJ, Bodmer WF, Brown G, Galfre G, Milstein C, Williams AF, Ziegler A. Production of monoclonal antibodies to group A erythrocytes, HLA and other human cell surface antigens-new tools for genetic analysis. Cell. 1978;14:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redman CW, McMichael AJ, Stirrat GM, Sunderland CA, Ting A. Class 1 major histocompatibility complex antigens on human extra-villous trophoblast. Immunology. 1984;52:457–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perosa F, Luccarelli G, Prete M, Favoino E, Ferrone S, Dammacco F. β2-microglobulin-free HLA class I heavy chain epitope mimicry by monoclonal antibody HC-10-specific peptide. J Immunol. 2003;171:1918–1926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stam NJ, Spits H, Ploegh HL. Monoclonal antibodies raised against denatured HLA-B locus heavy chains permit biochemical characterization of certain HLA-C locus products. J Immunol. 1986;137:2299–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sernee MF, Ploegh HL, Schust DJ. Why certain antibodies cross-react with HLA-A and HLA-G: epitope mapping of two common MHC class I reagents. Mol Immunol. 1998;35:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(98)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lampson LA, Fisher CA, Whelan JP. Striking paucity of HLA-A, B, C and β2-microglobulin on human neuroblastoma cell lines. J Immunol. 1983;130:2471–2478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandoh N, Ogino T, Cho HS, Hur SY, Shen J, Wang X, Kato S, Miyokawa N, Harabuchi Y, Ferrone S. Development and characterization of human constitutive proteasome and immunoproteasome subunit-specific monoclonal antibodies. Tissue Antigens. 2005;66:185–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Campoli M, Cho HS, Ogino T, Bandoh N, Shen J, Hur SY, Kageshita T, Ferrone S. A method to generate antigen-specific mAb capable of staining formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. J Immunol Methods. 2005;299:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogino T, Wang X, Ferrone S. Modified flow cytometry and cell-ELISA methodology to detect HLA class I antigen processing machinery components in cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum. J Immunol Methods. 2003;278:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramal LM, Feenstra M, van der Zwan AW, Collado A, Lopez-Nevot MA, Tilanus M, Garrido F. Criteria to define HLA haplotype loss in human solid tumors. Tissue Antigens. 2000;55:443–448. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.550507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodfellow PN, Jones EA, Van Heyningen V, Solomon E, Bobrow M, Miggiano V, Bodmer WF. The β2-microglobulin gene is on chromosome 15 and not in the HLA-region. Nature. 1975;254:267–269. doi: 10.1038/254267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugita M, Brenner MB. An unstable β2-microglobulin: major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chain intermediate dissociates from calnexin and then is stabilized by binding peptide. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2163–2171. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue C, Plieth D, Venkov C, Xu C, Neilson EG. The gatekeeper effect of epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulates the frequency of breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3386–3394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson EW, Newgreen DF, Tarin D. Carcinoma invasion and metastasis: a role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition? Cancer Res. 2005;65:5991–5995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabrera CM, Jiménez P, Cabrera T, Esparza C, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. Total loss of MHC class I in colorectal tumors can be explained by two molecular pathways: β2-microglobilin inactivation in MSI-positive tumors and LMP7/TAP2 downregulation in MSI-negative tumors. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:211–219. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez B, Benitez R, Fernández MA, Oliva MR, Soto JL, Serrano S, López Nevot MA, Garrido F. A new β2 microglobulin mutation found in a melanoma tumor cell line. Tissue Antigens. 1999;53:569–572. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.530607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seliger B, Cabrera T, Garrido F, Ferrone S. HLA class I antigen abnormalities and immune escape by malignant cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:3–13. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang CC, Campoli M, Restifo NP, Wang X, Ferrone S. Immune selection of hot-spot β2-microglobulin gene mutations, HLA-A2 allospecificity loss, and antigen-processing machinery component down-regulation in melanoma cells derived from recurrent metastases following immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2005;174:1462–1471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuroda N, Toi M, Hiroi M, Enzan H. Review of sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma with focus on clinical and pathobiological aspects. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:551–555. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris SC, Hird PM, Shortland JR. Immunohistochemistry and lectin histochemistry in sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: a comparison with classical renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 1989;15:607–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomera KM, Farrow GM, Lieber MM. Sarcomatoid renal carcinoma. J Urol. 1983;130:657–659. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandha HS, John RJ, Hutchinson J, James N, Whelan M, Corbishley C, Dalgleish AG. Dendritic cell immunotherapy for urological cancers using cryopreserved allogeneic tumour lysate-pulsed cells: a phase I/II study. BJU Int. 2004;94:412–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su Z, Dannull J, Heiser A, Yancey D, Pruitt S, Madden J, Coleman D, Niedzwiecki D, Gilboa E, Vieweg J. Immunological and clinical responses in metastatic renal cancer patients vaccinated with tumor RNA-transfected dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2127–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gouttefangeas C, Stenzl A, Stevanović S, Rammensee HG. Immunotherapy of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]