Abstract

Critical-sized defects were created in rat calvariae previously treated with 12 Gy irradiation 2 weeks before surgery. Gelatin scaffolds containing lyophilized AdBMP-2, freely suspended AdBMP-2, or negative controls were transplanted in the defects for 5 weeks. Lyophilized AdBMP-2 treatment significantly improved both bone quality and quantity over free AdBMP-2 administration. The effects of radiotherapy on osteogenesis were also compared. Bone mineral density was reduced after radiotherapy. Histological analyses demonstrated that radiation damage led to less bone regeneration. Woven bone and immature marrow formed in the radiated defects indicated that preoperative radiotherapy retarded normal bone development and turnover. Finally, the gelatin scaffolds with lyophilized AdBMP-2 were stored at -80°C to determine adenovirus stability. Micro-CT quantification demonstrated that there were no significant differences between bone regeneration treated with lyophilized AdBMP-2 before and after 1-month storage, suggesting that virus-loaded scaffolds should be convenient for application as pre-made constructs for surgical applications.

Keywords: Tissue Engineering, Gene delivery, Lyophilization, Radiotherapy, Bone regeneration

INTRODUCTION

Radiation therapy (XRT) is commonly used as primary treatment and as an adjuvant to the surgical excision of oral squamous cell cancer in the head and neck. While XRT is effective in destroying potential residual cancer cells, the side effects to adjacent tissue are well documented and include damage to normal epithelial, dermal and endothelial cells (Reuther et al., 2003). The ensuing hypocellularity and hypoxic environment leads to scarring and fibrosis that make secondary reconstruction of the surgical site difficult. In addition, reconstruction of recurrent tumors and the treatment of extensive osteoradionecrosis, as a side effect of XRT, often require the removal of large amounts of bone in a previously irradiated field. Current state of the art reconstruction of large maxillofacial defects that include bone is free tissue transfer with vascularized flaps from distant sites including fibula, radius, iliac crest, and scapula (Disa and Cordeiro, 2000; Emerick and Teknos, 2007). While these procedures have been proven effective, they require extended hospitalization for flap monitoring and recovery, generally compromise normal anatomy and require a secondary donor site with associated morbidity and complications.

As an alternative to the use of free tissue transfer, tissue-engineering approaches are being developed to regenerate large skeletal defects. Potential advantages to these approaches include the possibility of mirroring normal form and function without donor site morbidity. We choose to model the most difficult clinical reconstructive setting utilizing previously irradiated sites for reconstruction. This model is most applicable to treatment of recurrent disease and the post XRT complication of osteoradionecrosis. Technology successfully applied to this stringent environment would also be likely to succeed in a clinical setting where XRT is delivered within 6 weeks following definitive surgical treatment, the most common approach for treatment of primary squamous cell carcinomas within the oral cavity.

One tissue engineering approach to regenerate bone involves the delivery of cell-signaling factors such as growth factors or genes from biomaterial scaffolds. Growth factors such as VEGF, TGF-β1, and BMPs, have been delivered to defects and have significantly improved bone repair in irradiated sites (Ehrhart et al., 2005; Howard et al., 1998; Kaigler et al., 2006; Khouri et al., 1996; Wurzler et al., 1998). However, these studies did not demonstrate complete regeneration of critical-sized defects when using protein delivery alone. Furthermore, milligram doses are often necessary in protein-based therapies, which is extremely expensive and thus may be impractical for universal clinical application. Therefore, regenerative gene therapy may be an effective alternative method to address these difficulties by sustainably expressing osteoinductive factors through cells that are transduced in vivo (Franceschi, 2005). The effectiveness of BMP-transduced cells has been studied for the regeneration of critical-sized bone defects (Chang et al., 2003; Gysin et al., 2002; Koh et al., 2008; Krebsbach et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2001) and this ex vivo gene therapy has been shown to be capable of regenerating bone in defects compromised by XRT (Nussenbaum et al., 2003; Nussenbaum et al., 2005). While ex vivo gene therapy improves regeneration in bone defects compromised by XRT, this method requires the harvest of autologous cells from patients for in vitro transduction followed by in vivo transplantation. This sequence is very laborious, expensive and increases the risk of infection.

An in vivo regenerative gene therapy approach in which genes are directly delivered from biomatierials would circumvent the need to harvest and transplant autologous cells. We have developed methods to deliver adenovirus encoding bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) from biomaterials and demonstrated that such viral delivery is effective in regenerating bone in vivo (Hu et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2008). Using this gene delivery platform, host cells grown on scaffolds were transduced in situ to induce bone formation in critical-sized defects (Hu et al., 2007). Therefore, we hypothesized that this in vivo gene therapy strategy would be able to regenerate craniofacial defects compromised by preoperative XRT, an environment that is ordinarily refractory to most tissue engineering approaches. In addition, due to the high stability of lyophilized viral vectors, we investigated the feasibility of this gene delivery in preparing adenovirus-loaded scaffolds as pre-made constructs for surgical convenience.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of recombinant adenoviral vectors

An adenovirus encoding BMP-2 gene and CMV promoter sequence (AdBMP-2) was constructed using Cre/lox recombination with E1 and E3 deletion as previously described (Yang et al., 2003). Briefly, a full-length of BMP-2 cDNA was cloned into pAdlox, and then was cotransfected with Ψ5 into CRE8 cells (Hardy et al., 1997). Viral vectors were amplified in 293 cells and purified by gradient ultracentrifugation.

Animal irradiation

Surgical sites in Fisher rats were irradiated as previous described (Nussenbaum et al., 2005). Briefly, rats were anesthetized and a single 12-Gy dose was delivered to Dmax at a source-to-skin distance of 80 cm in an 11.47-min exposure to the surgical site. The rest of the body was shielded (Fields et al., 2000). The radiation dose was administered 2 weeks before the surgical procedure to mimic a clinical pre-surgical radiation protocol.

Polymer matrix loaded with adenovirus for BMP-2 gene delivery

Gelatin sponges (Pfizer, New York City, NY) were used as scaffolds to deliver AdBMP-2. For the virus lyophilization groups, 108 PFU adenoviral vectors were loaded in scaffolds before freeze drying for 24 hr (Hu et al., 2007). A free AdBMP-2 group was also prepared with the same virus concentration in PBS. To investigate the stability of freeze-dried adenovirus, one group of AdBMP2 lyophilized in scaffolds was stored at -80 °C for 1 month prior to implantation.

Calvarial defect model and specimen harvest

Critical-sized defects in calvariae were created as previous described (Hu et al., 2007). Briefly, a defect was created using an 8 mm diameter trephine burr. The calvarial disks were removed and viral loaded scaffolds or controls were placed in the defects. Five animals per group were implanted for 5 weeks. All specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin phosphate and stored in 70% alcohol prior to analysis. All animal protocols followed the guidelines established by the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

Micro-CT 3D reconstruction

Specimens were scanned by μ-CT on a MS8-CMR-100 μ-CT scanner (EVS Corp, London, ON, Canada). Reconstructed images were analyzed with Microview v2.1.0 software (GE, Waukesha, WI, USA). Circular regions of 8 mm in diameter were cropped as the region of interest (ROI). The bone volume fraction (BVF) and bone mineral density (BMD) of the regenerated bone were evaluated in the ROI, respectively. The superficial views were captured, and the bone coverage in defects was evaluated as bone area fraction (BAF).

RESULTS

3-D images reconstructed by μ-CT scanning

To facilitate bone regeneration, adenovirus encoding BMP-2 was delivered as either a free suspension or lyophilized within gelatin scaffolds before being implanted in calvarial defects compromised by preoperative XRT. Adenovirus encoding LacZ was used as a negative control to illustrate the effects of AdBMP2 on bone formation. The cranial specimens were harvested for μ-CT scanning to reconstruct 3-D images and processed for histological analysis.

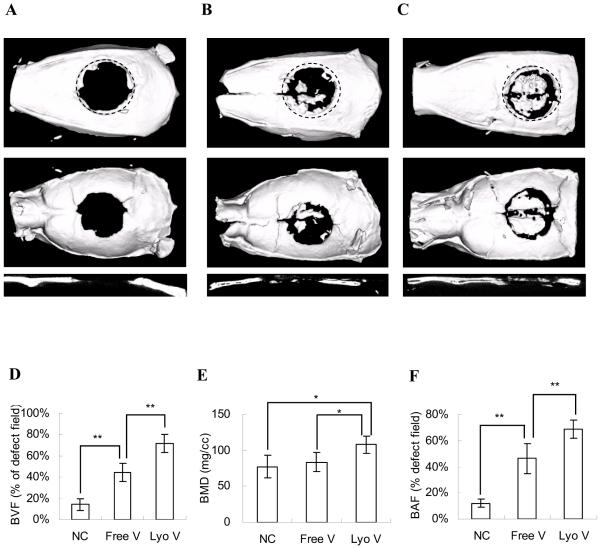

There was almost no regenerated bone in the defects except in the immediate vicinity of the surgical margins in the negative controls, demonstrating that AdLacZ was incapable of inducing new bone formation (Fig 1A). Using scaffolds with AdBMP2 suspensions, few bony islands were distributed throughout the defects, but newly formed bone did not significantly cover the defects (Fig 1B). In contrast, when AdBMP2 was delivered in a lyophilized formulation, significant regeneration nearly spanning the entire defect was achieved (Fig 1C).

Figure 1. Bone formation in critical-sized calvarial defects comprised by radiation therapy.

μ-CT analysis was performed to visualize and quantify bone regeneration. The 3-D images were reconstructed to illustrate the top, bottom, and sagittal section views of (A) AdLacZ lyophilized in gelatin scaffolds; (B) AdBMP-2 freely suspended in gelatin scaffolds and (C) AdBMP-2 lyophilized in gelatin scaffolds. The newly formed bone was evaluated by (D) bone volume fraction (BVF) in defects; (E) bone mineral density (BMD) of newly formed bone; (F) bone area fraction (BAF) in defects assessed from the projected area ratio of the μ-CT image. The data were compared by Student t test (*: p<0.05; **: p<0.01). The dotted line represents the surgical margin of the cranial defect.

Quantitative assessment of regenerated bone

Both BVF and BMD were evaluated by μ-CT scanning to quantify newly formed bone (Fig 1D,E). Compared to the negative control group, suspended AdBMP2 enhanced the BVF from 14.2±5.3% to 44.6±8.5%. However, there was no significant difference in BMD between these two groups (77±16 mg/cc vs. 88±13 mg/cc). In contrast, AdBMP2 lyophilized within scaffolds significantly improved both BVF and BMD over the AdLacZ and free AdBMP2 groups.

To judge the extent of regenerated bone in the cranial defects, the BAF of newly formed bone was determined based on 3-D projection images captured by μ-CT (Fig 1F). Compared to the free AdBMP-2 group, in which bone only covered a modest region of the defects (46.4±11.3%), lyophilized AdBMP2 treatment significantly increased bone formation and most of the area of the defects was covered by mineralized tissue (68.7±7.1%). These results suggest that the therapeutic effects of AdBMP2 were greatly improved when AdBMP was locally delivered within scaffolds.

The effects of bone regeneration in critical sized defects compromised by XRT

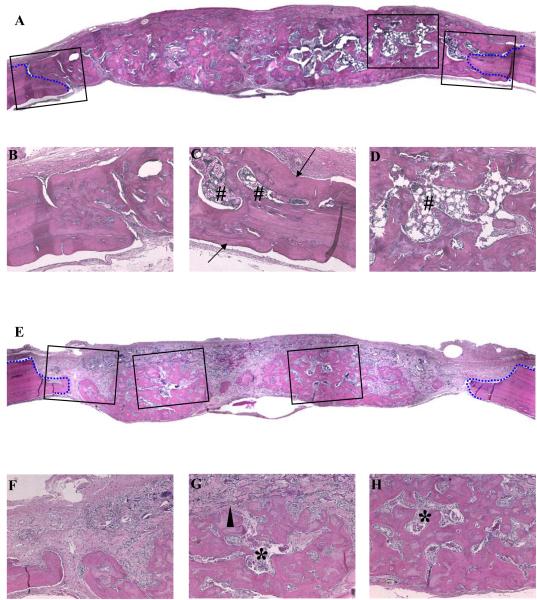

To evaluate the extent to which preoperative XRT retarded bone regeneration, rats without XRT treatment (No-XRT) were implanted with gelatin sponges containing lyophilized AdBMP-2. At the time of specimen harvest, scaffolds with lyophilized AdBMP-2 induced new bone growth that nearly filled the entire defect, and no residual scaffold material was observed (Fig 2A). The regenerated bone was integrated with the native bone at the defect margins (Fig 2B,C) and supported a robust hematopoietic marrow (Fig 2D).

Figure 2. Histological analysis of critical-sized calvarial defects with or without preoperative radiation therapy.

Sections were prepared from the midline of defects. The defects without (A-D) and with (E-H) radiation treatment were examined. The defect margins are depicted by blue lines. (Original magnitudes: (A), (E) X40, and (B-D), (F-H) X100) (Arrow: lamellar bone; arrow head: undegraded gelatin sponges; #: mature bone marrow with adipose tissues; *: immature bone marrow)

Defects treated with preoperative XRT (Pre-OP) were also successfully regenerated with lyophilized AdBMP2-containing scaffolds. Microscopic sections illustrated defects that were filled with newly formed bone (Fig 2E). However, the bone morphology was different from the non-XRT treated group. Here, the bone was admixed with connective tissues, with incomplete bridging (Fig 2E). Osseointegration at defect edges was not as complete as was observed in the non-XRT-treated group (Fig 2F) and remnants of non-resorbed scaffold material remained within the tissues (Fig 2G). The woven regenerated bone and sparse marrow suggested that normal bone remodeling was negatively affected by XRT (Fig 2G,H).

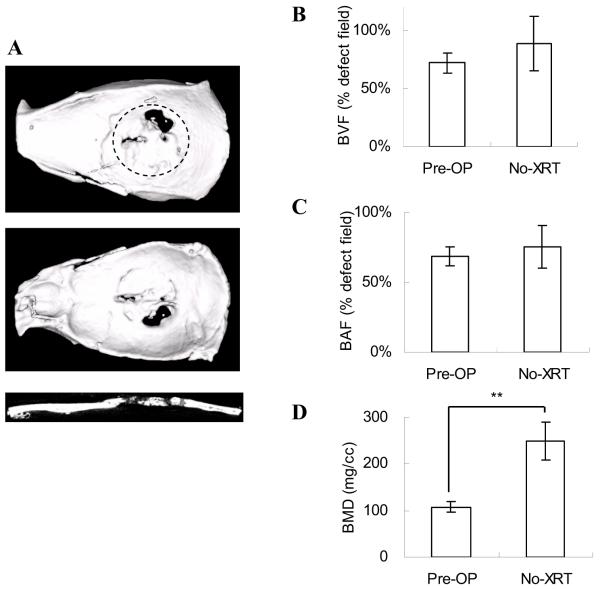

Bone regeneration was also compared using μ-CT analysis. Regenerated bone in the Pre-OP group (Fig 1C) illustrated similar coverage in defects as in the non-XRT group (Fig 3A). However, compared to the Pre-OP group in which non-union bone gaps existed between newly formed bone and defect margins, bone was well integrated with defect edges in non-XRT group.

Figure 3. Bone formation in critical-sized calvarial defects without radiation therapy (No-XRT).

(A) The 3-D images were reconstructed to illustrate the top, bottom, and sagittal section views. Bone regeneration was compared to the irradiated group (Pre-OP) by μ-CT analyses: (B) BVF; (C) BAF; (D) BMD. The data were analyzed by Student t test (*: p<0.05; **: p<0.01). The dotted line represents the surgical margin of the cranial defect.

The quantified data demonstrated that the BVF and BAF in these two groups had no significant differences (Fig 3 B,C). However, the BMD of the Pre-OP group was significantly less than the No-XRT group (108±12 mg/cc vs. 250±41mg/cc), suggesting the level of mineralization in the Pre-OP group was reduced because of the side effects of radiation (Fig 3D). Images of sagittal section were consistent with this result, demonstrating that the radiographs of defects in the Pre-OP group were less radiopaque than in the No-XRT group (Fig 1C, 3A).

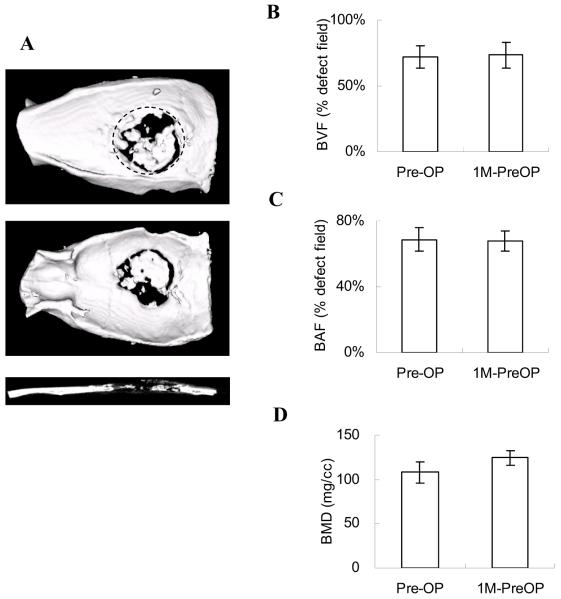

Adenoviral bioactivity is preserved in lyophilized gelatin scaffolds

Approximately 80% of adenovirus activity within lyophilized biomaterial scaffolds is maintained up to 6 months (Hu et al., 2007). Therefore, we tested the practicality of preparing virus-scaffold complexes as pre-made constructs for potential clinical applications. AdBMP2 lyophilized in gelatin scaffolds were stored at -80°C for 1 month and were implanted in calvarial defects with preoperative XRT (1M-PreOP). The 3-D images captured by μ-CT scanning illustrated that bone formation in the 1M-PreOP group had similar bone defect coverage as in the Pre-OP group (Fig 1C, 4A). The bone volume, area, and density assessments all demonstrated no significant differences between the Pre-OP and 1M-PreOP groups, suggesting that lyophilized AdBMP2 had similar therapeutic effects before and after 1 month storage (Fig 4 B-D). These results suggest that lyophilized AdBMP-2 maintained biologic activity while localized in scaffolds without losing its infectivity after long-term storage.

Figure 4. Irradiated defects regenerated with AdBMP-2 lyophilized in gelatin scaffolds.

Pre-made AdBMP-2 lyophilized scaffolds (1M-PreOP) were stored at -80°C for 1 month prior to surgery to test the stability of viruses in the gelatin scaffolds. (A) The 3-D images were reconstructed to illustrate the top, bottom, and sagittal section views. The bone regeneration was compared to the radiated group before storage (Pre-OP) by μ-CT analyses: (B) BVF; (C) BAF; (D) BMD. The data were analyzed by Student t test (*: p<0.05; **: p<0.01). The dotted line represents the surgical margin of the cranial defect.

DISCUSSION

Compared to the freely suspended virus group, AdBMP-2 lyophilized within gelatin scaffolds demonstrated superior bone formation in bone defects compromised by pre-operative XRT (Fig 1 B,C). Although the BVF and BAF in the suspended AdBMP-2 group were both higher than in the negative control group, there were no significant differences in BMD between these two groups (Fig 1 D-F). This suggests that the modest osteogenesis induced by free AdBMP-2 mainly increased bone quantity (BVF and BAF), but not bone quality (BMD). In contrast, lyophilized AdBMP-2 demonstrated BMD improvement over the other two groups, indicating that this local virus delivery enhanced both bone quantity and quality in irradiated defects. Because sufficient mineral density is important for bone homeostasis and function, the lyophilization strategy would be likely be more appropriate for treating irradiated bone defects than a conventional bolus gene delivery method.

To determine the effects of XRT on bone regeneration using an in vivo regenerative gene therapy strategy, gelatin scaffolds containing lyophilized AdBMP-2 were implanted into calvarial defects with and without preoperative XRT. Such wounds that are subjected to prior XRT are among the most difficult bony reconstructions both in preclinical studies and clinical practice (Deutsch et al., 1999). The newly formed bone in the Pre-OP group had similar bone volume and coverage in defects as in the No-XRT group (Fig 3 B,C). However, the sagittal images from μ-CT scanning and the BMD analysis demonstrated that the mineralized tissue in the Pre-OP group was less dense than in the No-XRT group (Fig 1C, 3A,D). This suggests that most of the osteoprogenitor or BMP-responsive cells were likely destroyed during XRT. Due to the lack of sufficient BMP-responsive cells, bone development and maturation processes were retarded, resulting in reduced calcium deposition in the newly formed bone. The histomorphologic assessments demonstrated that woven bone was mainly formed in the Pre-OP defects (Fig 2 E,G,H). In addition, the sparse marrow also suggests a poor suboptimal environment caused by radiation, and the bone regeneration period may need to be longer to properly recover (Fig 2 G,H).

The long-term storage experiments demonstrated that the biologic activity and therapeutic effects of lyophilized AdBMP-2 were maintained after 1-month storage at -80°C (Fig 4 A-D). These results suggest that viral vectors encoding cell-signaling genes can be incorporated within biomaterial scaffolds and stored at low temperatures as pre-made constructs, making clinical application convenient for surgeons to apply in an operating room setting.

In this study, we developed an in vivo gene therapy by locally delivering BMP-2 gene within scaffolds, which effectively repaired defects compromised by radiation damage. Compared to ex vivo gene therapy, lyophilized adenovirus in situ transduce cells in the wound sites and simplifies the treatment by avoiding repeated surgeries. Without the use of autologous cells, this method reduces the risk of contamination which may occur during in vitro cell culture. Furthermore, because virus-scaffold constructs can be prepared and stored in advance of a regenerative procedure, this virus-loaded scaffold could be applied in emergency cases. From a clinical standpoint, the development of this technology could provide alternative options for bone replacement in irradiated tissue beds without the limitations and side effects of current reconstructive techniques. In addition, lyophilized adenovirus in situ could have broad application to non-irradiated tissues where similar reconstruction requirements exist in a tissue environment not compromised by XRT.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health grant RO1 DE018890 (PHK). The authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Renny Franceschi for the use of the AdBMP construct.

REFERENCES

- Chang SCN, Wei FC, Chuang HL, Chen YR, Chen JK, Lee KC, et al. Ex vivo gene therapy in autologous critical-size craniofacial bone regeneration. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;112(7):1841–1850. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000091168.73462.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M, Kroll SS, Ainsle N, Wang B. Influence of radiation on late complications in patients with free fibular flaps for mandibular reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42(6):662–4. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199906000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disa JJ, Cordeiro PG. Mandible reconstruction with microvascular surgery. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;19(3):226–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-2388(200010/11)19:3<226::aid-ssu4>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart NP, Hong L, Morgan AL, Eurell JA, Jamison RD. Effect of transforming growth factor-beta1 on bone regeneration in critical-sized bone defects after irradiation of host tissues. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66(6):1039–45. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerick KS, Teknos TN. State-of-the-art mandible reconstruction using revascularized free-tissue transfer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7(12):1781–8. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.12.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields MT, Eisbruch A, Normolle D, Orfali A, Davis MA, Pu AT, et al. Radiosensitization produced in vivo by once-vs. twice-weekly 2′2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (gemcitabine) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(3):785–91. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi RT. Biological approaches to bone regeneration by gene therapy. J Dent Res. 2005;84(12):1093–103. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysin R, Wergedal JE, Sheng MH, Kasukawa Y, Miyakoshi N, Chen ST, et al. Ex vivo gene therapy with stromal cells transduced with a retroviral vector containing the BMP4 gene completely heals critical size calvarial defect in rats. Gene Ther. 2002;9(15):991–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy S, Kitamura M, Harris-Stansil T, Dai Y, Phipps ML. Construction of adenovirus vectors through Cre-lox recombination. J Virol. 1997;71(3):1842–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1842-1849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BK, Brown KR, Leach JL, Chang CH, Rosenthal DI. Osteoinduction using bone morphogenic protein in irradiated tissue. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(9):985–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.9.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WW, Wang Z, Hollister SJ, Krebsbach PH. Localized viral vector delivery to enhance in situ regenerative gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2007;14(11):891–901. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WW, Lang MW, Krebsbach PH. Development of adenovirus immobilization strategies for in situ gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2008;10(10):1102–12. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaigler D, Wang Z, Horger K, Mooney DJ, Krebsbach PH. VEGF scaffolds enhance angiogenesis and bone regeneration in irradiated osseous defects. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(5):735–44. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khouri RK, Brown DM, Koudsi B, Deune EG, Gilula LA, Cooley BC, et al. Repair of calvarial defects with flap tissue: role of bone morphogenetic proteins and competent responding tissues. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(1):103–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199607000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JT, Zhao Z, Wang Z, Lewis IS, Krebsbach PH, Franceschi RT. Combinatorial gene therapy with BMP2/7 enhances cranial bone regeneration. J Dent Res. 2008;87(9):845–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebsbach PH, Gu K, Franceschi RT, Rutherford RB. Gene therapy-directed osteogenesis: BMP-7-transduced human fibroblasts form bone in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11(8):1201–10. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Musgrave D, Pelinkovic D, Fukushima K, Cummins J, Usas A, et al. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2-expressing muscle-derived cells on healing of critical-sized bone defects in mice. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American Volume. 2001;83A(7):1032–1039. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenbaum B, Rutherford RB, Teknos TN, Dornfeld KJ, Krebsbach PH. Ex vivo gene therapy for skeletal regeneration in cranial defects compromised by postoperative radiotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14(11):1107–15. doi: 10.1089/104303403322124819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenbaum B, Rutherford RB, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in cranial defects previously treated with radiation. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(7):1170–7. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000166513.74247.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther T, Schuster T, Mende U, Kubler A. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws as a side effect of radiotherapy of head and neck tumour patients--a report of a thirty year retrospective review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(3):289–95. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzler KK, DeWeese TL, Sebald W, Reddi AH. Radiation-induced impairment of bone healing can be overcome by recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Craniofac Surg. 1998;9(2):131–7. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Wei D, Wang D, Phimphilai M, Krebsbach PH, Franceschi RT. In vitro and in vivo synergistic interactions between the Runx2/Cbfa1 transcription factor and bone morphogenetic protein-2 in stimulating osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(4):705–15. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]