Abstract

The serotonin transporter (5-HTT) plays a critical role in regulating serotonergic neurotransmission and is implicated in the pathophysiology of anxiety and affective disorders. PET scans using [C-11]DASB to measure 5-HTT availability (an index of receptor density and binding) were performed in 34 rhesus monkeys in which the relation between regional brain glucose metabolism and anxious temperament was previously established. 5-HTT availability in the amygdalohippocampal area and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis correlated positively with individual differences in a behavioral and neuroendocrine composite of anxious temperament. 5-HTT availability also correlated positively with stress-induced metabolic activity within these regions. Collectively, these findings suggest that serotonergic modulation of neuronal excitability in the neural circuitry associated with anxiety mediates the developmental risk for affect-related psychopathology.

Keywords: neuroimaging, development, positron emission tomography, amygdalohippocampal area, extended amygdala, non-human primate

Introduction

Extreme anxious temperament early in life is a prominent risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders (Biederman et al., 2001), and previous work suggests that amygdala activity in adult humans reflects a history of early anxious temperament (Schwartz et al., 2003). The nonhuman primate provides an excellent model to study the mechanisms underlying human anxiety (Kalin and Shelton, 2003), and we defined an anxious temperament phenotype in young rhesus monkeys using behavioral and neuroendocrine measures that include: threat-induced freezing, separation-induced vocalizations and stress-induced changes in cortisol levels (Fox et al., 2008). Using this model, high-resolution fluoro-18-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) revealed that individual differences in anxious temperament were positively correlated with individual differences in brain metabolism within the amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), periaqueductal gray and hippocampus, suggesting involvement of a wider circuit in mediating the risk for developing anxiety and depression (Fox et al., 2008).

Examining the role of specific neurotransmitter systems in modulating the activity of this circuit as it relates to anxious temperament is a critical next step and the serotonergic system is particularly interesting in this regard. The serotonergic system modulates amygdala-frontal circuits implicated in the regulation of emotion, and altered function of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) is hypothesized to play a role in affect and anxiety-related psychopathology (Holmes, 2008). Anatomical studies in primates demonstrate that 5-HTT distribution and density reflect the magnitude of regional brain serotonergic innervation (Smith and Porrino, 2008), and by clearing serotonin from the synapse, 5-HTT regulates serotonin signaling. 5-HTT is also the target of the most commonly used antidepressant and anxiolytic drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs). Furthermore, a polymorphism in the gene encoding 5-HTT (5-HTTLPR) is associated with amygdala (Hariri et al., 2002) and BNST (Kalin et al., 2008) reactivity, as well as the vulnerability to develop stress-related psychopathology (Hariri and Holmes, 2006).

The aim of the present study was to assess the extent to which variation in regional 5-HTT availability, an index of 5-HTT receptor density and ligand-protein binding, is predictive of individual differences in anxious temperament. To this end, high-resolution PET scans were performed using [C-11]DASB, a high-affinity tracer of 5-HTT, in 34 monkeys (mean age = 4.4 years; 12 male, 22 female) in which the relation between regional brain glucose metabolism and anxious temperament was previously established (Fox et al., 2008). We selectively focused on structures where metabolic activity was associated with anxious temperament, and performed voxelwise regression analyses to examine the relation between 5-HTT availability and anxious temperament within the a priori defined brain regions of interest. Within these brain regions, we hypothesized that individual differences in 5-HTT availability would predict individual differences in anxious temperament.

Materials and Methods

We employed the same sample described by Fox et al. (2008). The methods for behavioral and neuroendocrine assessment of anxious temperament and for FDG-PET are detailed in that report and are only briefly described here.

Subjects

Thirty-six rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) underwent behavioral testing and FDG-PET scans when they were juveniles (mean age = 2.7 years +/- .09, SEM). Thirty-four (22 females) underwent [C-11]DASB-PET scans approximately two years later. Animals were mother-reared, and pair-housed at the Harlow Primate Laboratory and the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Fluoro-18-deoxyglucose PET Acquisition and Behavioral Testing Paradigm

Animals received intravenous injections of 10 mCi FDG immediately before exposure to the experimental paradigm. Behaviors were monitored non-invasively using a video-recorder during each of several experimental conditions. The first stressful condition consisted of a separation in which the animal was relocated to a test-cage and remained alone for 30-minutes (ALN). The second stressful condition was the no eye contact (NEC) component of the human intruder paradigm (Kalin and Shelton, 1989), in which the animals were placed in the test cage and a human entered the room and stood still at a distance of 2.5 meters while presenting only their profile to the animal. Data were also collected during non-stressful home cage conditions. Following 30 minutes of exposure to the experimental conditions, animals were anesthetized with 15mg/kg ketamine and blood samples were taken. Subjects were then positioned in a sterotaxic head holder, and given isoflurane gas anesthesia (1-2%) for the duration of the 60-minute scanning procedure, during which FDG-uptake was measured. Scanning was performed using the microPET P4 scanner (Concorde Microsystems, Inc., Knoxville, TN).

Behavioral Assessment

Freezing was defined as a period of at least three seconds characterized by tense body posture, no vocalizations and no movement other than slow movements of the head. The frequency of coo vocalizations was also assessed. To ensure that behavioral data were normally distributed, the duration of freezing behavior was log-transformed and the frequency of coo vocalizations was square root transformed. Cortisol was measured in plasma samples using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX). To create a composite measure of anxious temperament, we first calculated the inverse of cooing frequency, then z-scored each measure (freezing, cortisol, and cooing) while controlling for any age effects across all animals, and computed the mean of the z-scored measures for each subject.

MRI Scanning

MRI data were collected using a GE Signa 3T scanner (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) with a standard quadrature birdcage headcoil using an axial 3D T1-weighted inversion-recovery fast gradient echo sequence (TR=9.4ms, TE 2.1ms, FOV=14cm, flip angle=10°, NEX=2, in-plane resolution=0.2734mm, 248 1-mm slices, .05mm interslice gap). Before undergoing MRI acquisition, the monkeys were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (15 mg/kg).

FDG-PET Pre-Processing

Each subject’s anatomical image was transformed to the standard space of Paxinos, Huang & Toga (Paxinos et al., 2000) after the creation of a study-specific template. First each subject’s T1-MRI image was manually skull-stripped of non-brain tissue using SPAMALIZE, http://brainimaging.waisman.wisc.edu/~oakes/spam/spam_frames.htm). Brain extracted MRI images were registered to an in-house 6-brain template in the standard space, using a 9-parameter linear transformation using FMRIB Software Library’s (FSL) “flirt” tool (Jenkinson et al., 2002). The brain-extracted MRI images in original space were then transformed to match this study-specific template using both linear 12-parameter affine, and 5th order non-linear transformation using Automated Image Registration (Woods et al., 1998). Images in standard space were segmented into specific tissue types, and voxelwise probabilities were calculated for gray-matter, white-matter and CSF using FSL-fast (Zhang et al., 2001). FDG-PET images were transformed into standard space based on the transformations derived from the anatomical data. FDG-PET images and gray-matter probability maps were smoothed using a 4mm FWHM Gaussian smoothing kernel to facilitate across-subject statistical comparisons.

[C-11]DASB PET Scanning

The DASB-PET methods are detailed in Christian et al. (in press), and are briefly described here. The [C-11] for the radiolabeling was produced with a National Electrostatics 9SDH 6 MeV Van de Graff tandem accelerator (Middleton, WI). PET data were acquired using a Concorde microPET P4 scanner (Tai et al., 2001). The monkeys were initially anesthetized with ketamine (15 mg/kg IM) at t = 55.4 ± 17.3 minutes prior to injection and maintained on 0.75% − 1.5% isoflurane for the duration of the entire imaging session. The animals were also administered atropine sulfate (0.27 mg IM) to minimize secretions during the course of the experiment, and positioned head down in the prone position. [C-11]DASB was administered with injected mean activity of 4.9 ± 1.1 mCi. Following the transmission scan, the radioligand was injected and dynamic data were acquired over 90 minutes. Corrections were made for scatter (direct calculation), attenuation, and normalization during reconstruction.

Data Analysis

The dynamic PET time series were transformed into parametric images with each voxel representing the distribution volume ratio (DVR) serving as an index of receptor binding (Innis et al., 2007). Cerebellar washout was estimated using the MRTM model as described by Ichise et al. (2003). The cerebellum was used as a reference region, and all voxels were divided by the mean cerebellar binding values (see Christian et al., in press). To reduce noise at the voxel-based level, the images from each time frame were spatially smoothed using a 3×3 (in-plane) voxel median filter, similar to techniques proposed by Zhou et al. (2003). Each subject’s DVR image was transformed into a standard space based on the corresponding MRI transformation.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using an adapted version of fmristat (Friston et al., 1995; Worsley et al., 1997). Voxelwise regression analyses were performed to examine the relations between 5-HTT availability and anxious temperament while controlling for the effects of age, DASB injected mass and gray matter probability (Oakes et al., 2007). Voxelwise tests were performed only in regions where FDG metabolism correlated significantly with the anxious temperament composite in both the NEC and ALN conditions (see purple clusters from Figure 4 of Fox et al., 2008). Within these pre-defined clusters the regression results were thresholded at p = 0.005 (uncorrected), and the DASB and FDG values were extracted from voxels within each cluster that survived the threshold. The DASB data were then residualized for the effects of age, gray matter probability and injection mass in order match the results produced by the voxelwise regression analysis; the FDG data were residualized for the effects of age and gray matter probability. Bivariate correlations between FDG and DASB were performed on the mean values from regions where both FDG and DASB were significantly correlated with anxious temperament. The FDG values were taken from the NEC component of the behavioral paradigm, and therefore represent glucose metabolism in response to a potential threat. (Analyses examining the relations between anxious temperament, 5-HTT availability and glucose metabolism from the social separation condition (ALN) can be seen in Tables S2 and S3 in the supplementary information online.) Hierarchical linear regression was used to determine the unique and shared variance in anxious temperament accounted for by the mean DASB and FDG values within each cluster.

Results

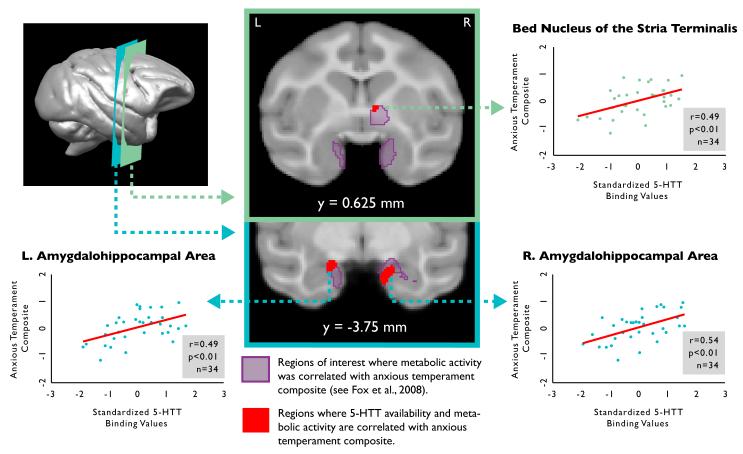

Voxelwise regression analysis demonstrated several significant correlations between anxious temperament and 5-HTT availability in components of the a priori defined circuit of anxious temperament (e.g., right amygdalohippocampal area: r = 0.536; left amygdalohippocampal area: r = 0.493; right BNST: r = 0.489; left BNST: r = 0.5; all p < 0.01; see Table 1, and Figure 1). (Results from an exploratory whole-brain voxelwise analysis can be seen in Table S1 in the supplementary information online.) Furthermore, glucose metabolism in response to a potential threat and 5-HTT availability were significantly positively correlated in the right amygdalohippocampal area (r = 0.479, p = 0.004) and the right BNST region (r = 0.377, p = 0.028; see Table 2). Using multiple linear regression, it was found that individual differences in glucose metabolism and 5-HTT availability together predicted 36% - 43% of the variance in anxious temperament within bilateral amygdalohippocampal area and BNST regions (see Table 3). Hierarchical linear regression revealed that, in addition to some shared variance, glucose metabolism and 5-HTT availability each uniquely explained significant proportions of the variance in anxious temperament within the left amygdalohippocampal area and bilateral BNST regions; a similar pattern was observed in the right amygdalohippocampal area (see Table 3). No significant sex differences were observed in the reported correlations (all p’s > 0.1).

Table 1.

Statistically significant bivariate correlations between mean 5-HTT binding values and the anxious temperament composite. Mean 5-HTT values were extracted from each brain region of interest, and residualized for the effects of age, gray matter probability and DASB injection mass.

| 5-HTT availability correlations with anxious temperament | n=34 | coordinates (realtive to AC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Region | hemisphere | Pearson’s r | p (two-tailed) | x | y | z |

| amygdalohippocampal area | left | 0.493 | 0.003 | −8.75 | −3.75 | −9.375 |

| BNST | left | 0.500 | 0.003 | −3.75 | −0.63 | 1.875 |

| hippocampus | left | 0.468 | 0.005 | −14.38 | −7.5 | −10 |

| genu of corpus callosum | midline | 0.472 | 0.005 | 0 | 10.63 | 6.875 |

| amygdalohippocampal area | right | 0.536 | 0.001 | 7.5 | −3.75 | −11.25 |

| BNST | right | 0.489 | 0.003 | 3.75 | 0.625 | 0.625 |

| hippocampus | right | 0.479 | 0.004 | 13.75 | −6.88 | −11.25 |

Figure 1.

Availability of 5-HTT in the amygdalohippocampal area and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is positively correlated with individual differences in the anxious temperament composite (red). Outlined in purple are the functionally derived regions of interest from a previous study in the same animals where metabolic activity correlated with the anxious temperament composite (see Fox et al., 2008).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between mean 5-HTT binding and FDG-PET values. Mean 5-HTT values were extracted from each brain region of interest, and residualized for the effects of age, gray matter probability and DASB injection mass. Mean FDG values were extracted from each brain region of interest, and residualized for the effects of age and gray matter probability. The FDG values were taken from the NEC component of the behavioral paradigm, and therefore represent glucose metabolism in response to a potential threat.

| 5-HTT availability correlations with NEC glucose metabolism | n=34 | coordinates (realtive to AC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Region | hemisphere | Pearson’s r | p (two-tailed) | x | y | z |

| amygdalohippocampal area | left | 0.292 | 0.094 | −8.75 | −3.75 | −9.375 |

| BNST | left | 0.195 | 0.270 | −3.75 | −0.625 | 1.875 |

| hippocampus | left | 0.254 | 0.147 | −14.375 | −7.5 | −10 |

| genu of corpus callosum | midline | 0.447 | 0.008 | 0 | 10.625 | 6.875 |

| amygdalohippocampal area | right | 0.479 | 0.004 | 7.5 | −3.75 | −11.25 |

| BNST | right | 0.377 | 0.028 | 3.75 | 0.625 | 0.625 |

| hippocampus | right | 0.067 | 0.707 | 13.75 | −6.875 | −11.25 |

Table 3.

Results of a hierarchical linear regression used to determine the unique and shared variance in anxious temperament accounted for by the mean 5-HTT availability and FDG metabolism within each cluster. The FDG values were taken from the NEC component of the behavioral paradigm, and therefore represent glucose metabolism in response to a potential threat.

| Total variance in anxious temperament accounted for by FDG(NEC) and 5-HTT |

5-HTT unique variance |

FDG(NEC) unique variance |

shared variance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Region | hemisphere | R2 | F | p | ΔR2 | F | p | ΔR2 | F | p | R2 - ΔR2 |

| amygdalohippocampal area | left | 0.434 | 11.890 | 0.0002 | 0.118 | 6.489 | 0.016 | 0.191 | 10.459 | 0.003 | 0.125 |

| BNST | left | 0.369 | 9.078 | 0.001 | 0.179 | 8.804 | 0.006 | 0.119 | 5.868 | 0.021 | 0.071 |

| hippocampus | left | 0.348 | 8.259 | 0.001 | 0.130 | 6.187 | 0.018 | 0.129 | 6.131 | 0.019 | 0.089 |

| genu of corpus callosum | midline | 0.346 | 8.208 | 0.001 | 0.070 | 3.325 | 0.078 | 0.124 | 5.868 | 0.021 | 0.152 |

| amygdalohippocampal area | right | 0.362 | 8.783 | 0.001 | 0.116 | 5.635 | 0.024 | 0.074 | 3.588 | 0.068 | 0.172 |

| BNST | right | 0.369 | 9.077 | 0.001 | 0.101 | 4.943 | 0.034 | 0.130 | 6.385 | 0.017 | 0.138 |

| hippocampus | right | 0.453 | 12.857 | 0.0001 | 0.199 | 11.305 | 0.002 | 0.224 | 12.693 | 0.001 | 0.030 |

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that 5-HTT availability in the BNST and amygdalohippocampal area predicts the behavioral and neuroendocrine components of anxious temperament as well as threat-related metabolic activity in these regions. The BNST, along with the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), is a major component of the extended amygdala, and a key output channel for limbic forebrain control of the HPA-axis mediated stress response (Heimer and Van Hoesen, 2006). Anatomical studies using 5-HTT as a marker demonstrate heavy serotonergic innervation of the macaque extended amygdala (Smith et al., 1999; Freedman and Shi, 2001; O’Rourke and Fudge, 2006). Likewise, regions of the primate amygdalohippocampal area receive dense serotonergic input (Sadikot and Parent, 1990; Bauman and Amaral, 2005; O’Rourke and Fudge, 2006), and tract-tracing studies in the rat demonstrate reciprocal connectivity between the amygdalohippocampal area and BNST (Pitkänen, 2000).

Studies imaging 5-HTT availability in humans in relation to affect and anxiety have produced inconsistent results (see Meyer, 2007). Two studies in depressed patients report decreases in 5-HTT availability in the amygdala (Parsey et al., 2006; Oquendo et al., 2007), and one study found that state anxiety in depressed patients was negatively correlated with amygdala 5-HTT availability (Reimold et al., 2008). Also, Rhodes et al. reported an inverse relationship between 5-HTT availability and amygdala responsivity measured with fMRI in normal adult humans (Rhodes et al., 2007). Other studies find elevated 5-HTT availability in the amygdala of patients with major depression (e.g., Cannon et al., 2007).

Since 5-HTT availability as assessed with PET is not a direct measure of function, we can only provide possible mechanistic explanations for how alterations in 5-HTT availability may influence brain activity and anxious temperament. Increased 5-HTT availability could be associated with lower synaptic serotonin levels, as the function of the transporter is to clear serotonin from the synapse. In support of this hypothesis, Heinz et al., (1998) used SPECT imaging in rhesus monkeys with β-CIT (a ligand that binds to both the dopamine and serotonin transporters) to demonstrate that reduced cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA were associated with increased brainstem transporter binding. Alternatively, increased 5-HTT availability could be a sign of increased (not decreased) synaptic serotonin, as neuroanatomical studies demonstrate that the magnitude of 5-HTT expression reflects the amount of serotonergic input to a region (Way et al., 2007). The degree to which these factors interact in determining post-synaptic serotonin levels remains unknown.

A lack of clarity regarding the actions of serotonin on amygdala and BNST function further complicates mechanistic interpretations. Preclinical studies provide evidence that serotonin reduces anxiety (Zangrossi et al., 2001; Burghardt et al., 2004) putatively by decreasing activity in the amygdala and BNST (Wang and Aghajanian, 1977; Stutzmann and LeDoux, 1999; Levita et al., 2004). This anxiolytic role of serotonin is consistent with results from long-term SSRI administration studies in humans demonstrating reduced anxiety (Kent et al., 1998) and a reduction in amygdala reactivity (Sheline et al., 2001; Harmer et al., 2006; Arce et al., 2008). Results from tryptophan depletion studies are also consistent, as they demonstrate that acute decreases in serotonin levels are accompanied by increased amygdala reactivity (Cools et al., 2005; van der Veen et al., 2007). However, other studies suggest opposite effects of serotonin (see Anderson et al., 2008). For example, the acute administration of SSRIs results in increased amygdala reactivity (Bigos et al., 2008). In addition, decreased dorsal raphe 5-HT1A autoreceptor expression, which is associated with increased forebrain serotonin release, is also associated with increased amygdala reactivity (Fisher et al., 2006). Finally, genetic differences associated with decreased 5-HT1A autoreceptor expression, and presumably increased serotonin signaling, is associated with greater threat-related amygdala reactivity and increased trait anxiety (Fakra et al., 2009).

It is also possible that the relation observed between 5-HTT availability and anxious temperament reflects functional changes that occurred early in development (Holmes et al., 2005). This is supported by studies in mice demonstrating that pharmacological blockade of 5-HTT in neonates increases anxiety and stress reactivity in adulthood (Ansorge et al., 2004). These ontogenetic effects have been hypothesized as a mechanism underlying the influences of 5-HTTLPR genetic variability on amygdala activity (Hariri et al., 2005), as well as the development of stress-related psychopathology (Caspi et al., 2003). This developmental hypothesis is particularly attractive for explaining the effects of the 5-HTTLPR, since numerous human imaging studies fail to demonstrate 5-HTT differences in s vs. l allele adults (e.g., Shioe et al., 2003; see however, Praschak-Rieder et al., 2007). To further understand the developmental influences of neonatal 5-HTT availability on adult anxiety and brain function, it will be important to perform additional studies manipulating primate 5-HTT function early in life.

While future studies are necessary to fully elucidate the role of serotonin in modulating anxious temperament, the present results demonstrate that 5-HTT availability in the BNST and amygdalohippocampal area predicts the behavioral and neuroendocrine components of anxious temperament. Moreover, the data suggest that the relation between 5-HTT availability and anxious temperament is in part mediated by serotonin’s effects on stress-related glucose metabolism within these regions. Therefore, based on the present data, we believe that altered serotonergic modulation in the amygdalohippocampal area and BNST may be an important factor in the development of the risk for anxiety and affect-related psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to H. Van Valkenberg, Tina Johnson, Kyle Meyer, Elizabeth Zao, Nick Vandehey, Jeff Rogers, the staff at the Harlow Center for Biological Psychology and the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center at the University of Wisconsin (RR000167) as this work could have never been accomplished without them. We also thank Alex Shackman for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the NIMH (MH84051, MH46729), The HealthEmotions Research Institute and Meriter Hospital.

References

- Anderson IM, McKie S, Elliott R, Williams SR, Deakin JF. Assessing human 5-HT function in vivo with pharmacoMRI. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge MS, Zhou M, Lira A, Hen R, Gingrich JA. Early-life blockade of the 5-HT transporter alters emotional behavior in adult mice. Science. 2004;306:879–881. doi: 10.1126/science.1101678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce E, Simmons AN, Lovero KL, Stein MB, Paulus MP. Escitalopram effects on insula and amygdala BOLD activation during emotional processing. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:661–672. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman MD, Amaral DG. The distribution of serotonergic fibers in the macaque monkey amygdala: an immunohistochemical study using antisera to 5-hydroxytryptamine. Neuroscience. 2005;136:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, Kagan J, Faraone SV. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigos KL, Pollock BG, Aizenstein HJ, Fisher PM, Bies RR, Hariri AR. Acute 5-HT reuptake blockade potentiates human amygdala reactivity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3221–3225. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt NS, Sullivan GM, McEwen BS, Gorman JM, LeDoux JE. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram increases fear after acute treatment but reduces fear with chronic treatment: a comparison with tianeptine. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon DM, Ichise M, Rollis D, Klaver JM, Gandhi SK, Charney DS, Manji HK, Drevets WC. Elevated serotonin transporter binding in major depressive disorder assessed using positron emission tomography and [11C]DASB; comparison with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R. Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a Polymorphism in the 5-HTT Gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian B, Fox A, Oler J, Vandehey N, Murali D, Rogers J, Oakes T, Shelton S, Davidson R, Kalin N. Serotonin Transporter Binding and Genotype in the Nonhuman Primate using [C-11]DASB PET. Neuroimage. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.090. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Calder AJ, Lawrence AD, Clark L, Bullmore E, Robbins TW. Individual differences in threat sensitivity predict serotonergic modulation of amygdala response to fearful faces. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:670–679. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakra E, Hyde LW, Gorka A, Fisher PM, Munoz KE, Kimak M, Halder I, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB, Hariri AR. Effects of HTR1A C(-1019)G on amygdala reactivity and trait anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:33–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.66.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PM, Meltzer CC, Ziolko SK, Price JC, Moses-Kolko EL, Berga SL, Hariri AR. Capacity for 5-HT1A-mediated autoregulation predicts amygdala reactivity. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1362–1363. doi: 10.1038/nn1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AS, Shelton SE, Oakes TR, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH. Trait-like brain activity during adolescence predicts anxious temperament in primates. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman LJ, Shi C. Monoaminergic innervation of the macaque extended amygdala. Neuroscience. 2001;104:1067–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline JB, Grasby PJ, Williams SC, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. Neuroimage. 1995;2:45–53. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Holmes A. Genetics of emotional regulation: the role of the serotonin transporter in neural function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Drabant EM, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Mattay VS, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. A susceptibility gene for affective disorders and the response of the human amygdala. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:146–152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Kolachana B, Fera F, Goldman D, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Mackay CE, Reid CB, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM. Antidepressant drug treatment modifies the neural processing of nonconscious threat cues. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:816–820. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Van Hoesen GW. The limbic lobe and its output channels: implications for emotional functions and adaptive behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:126–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Higley JD, Gorey JG, Saunders RC, Jones DW, Hommer D, Zajicek K, Suomi SJ, Lesch KP, Weinberger DR, Linnoila M. In vivo association between alcohol intoxication, aggression, and serotonin transporter availability in nonhuman primates. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1023–1028. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A. Genetic variation in cortico-amygdala serotonin function and risk for stress-related disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1293–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, le Guisquet AM, Vogel E, Millstein RA, Leman S, Belzung C. Early life genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, Takano A, Model K, Toyama H, Suhara T, Suzuki K, Innis RB, Carson RE. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1096–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis RB, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Defensive behaviors in infant rhesus monkeys: environmental cues and neurochemical regulation. Science. 1989;243:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.2564702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Nonhuman primate models to study anxiety, emotion regulation, and psychopathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1008:189–200. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Fox AS, Rogers J, Oakes TR, Davidson RJ. The serotonin transporter genotype is associated with intermediate brain phenotypes that depend on the context of eliciting stressor. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent JM, Coplan JD, Gorman JM. Clinical utility of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the spectrum of anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:812–824. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levita L, Hammack SE, Mania I, Li XY, Davis M, Rainnie DG. 5-hydroxytryptamine1A-like receptor activation in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: electrophysiological and behavioral studies. Neuroscience. 2004;128:583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JH. Imaging the serotonin transporter during major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:86–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke H, Fudge JL. Distribution of serotonin transporter labeled fibers in amygdaloid subregions: implications for mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes TR, Fox AS, Johnstone T, Chung MK, Kalin N, Davidson RJ. Integrating VBM into the General Linear Model with voxelwise anatomical covariates. Neuroimage. 2007;34:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Hastings RS, Huang YY, Simpson N, Ogden RT, Hu XZ, Goldman D, Arango V, Van Heertum RL, Mann JJ, Parsey RV. Brain serotonin transporter binding in depressed patients with bipolar disorder using positron emission tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, Huang YY, Simpson N, Arcement J, Huang Y, Ogden RT, Van Heertum RL, Arango V, Mann JJ. Lower serotonin transporter binding potential in the human brain during major depressive episodes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:52–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Huang X, Toga A. The rhesus monkey brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2nd Edition Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A. Connectivity of the rat amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala. A Functional Analysis. 2nd Edition Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 31–117. [Google Scholar]

- Praschak-Rieder N, Kennedy J, Wilson AA, Hussey D, Boovariwala A, Willeit M, Ginovart N, Tharmalingam S, Masellis M, Houle S, Meyer JH. Novel 5-HTTLPR allele associates with higher serotonin transporter binding in putamen: a [(11)C] DASB positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold M, Batra A, Knobel A, Smolka MN, Zimmer A, Mann K, Solbach C, Reischl G, Schwarzler F, Grunder G, Machulla HJ, Bares R, Heinz A. Anxiety is associated with reduced central serotonin transporter availability in unmedicated patients with unipolar major depression: a [11C]DASB PET study. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:606–613. 557. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes RA, Murthy NV, Dresner MA, Selvaraj S, Stavrakakis N, Babar S, Cowen PJ, Grasby PM. Human 5-HT transporter availability predicts amygdala reactivity in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9233–9237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1175-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadikot AF, Parent A. The monoaminergic innervation of the amygdala in the squirrel monkey: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 1990;36:431–447. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90439-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Wright CI, Shin LM, Kagan J, Rauch SL. Inhibited and uninhibited infants “grown up”: adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science. 2003;300:1952–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.1083703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA. Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:651–658. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shioe K, Ichimiya T, Suhara T, Takano A, Sudo Y, Yasuno F, Hirano M, Shinohara M, Kagami M, Okubo Y, Nankai M, Kanba S. No association between genotype of the promoter region of serotonin transporter gene and serotonin transporter binding in human brain measured by PET. Synapse. 2003;48:184–188. doi: 10.1002/syn.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HR, Porrino LJ. The comparative distributions of the monoamine transporters in the rodent, monkey, and human amygdala. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:73–91. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0176-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HR, Daunais JB, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Distribution of [3H]citalopram binding sites in the nonhuman primate brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:700–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, LeDoux JE. GABAergic antagonists block the inhibitory effects of serotonin in the lateral amygdala: a mechanism for modulation of sensory inputs related to fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-j0005.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YC, Chatziioannou A, Siegel S, Young J, Newport D, Goble RN, Nutt RE, Cherry SR. Performance evaluation of the microPET P4: a PET system dedicated to animal imaging. Physics In Medicine And Biology. 2001;46:1845–1862. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/7/308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen FM, Evers EA, Deutz NE, Schmitt JA. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on mood and facial emotion perception related brain activation and performance in healthy women with and without a family history of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:216–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RY, Aghajanian GK. Inhibiton of neurons in the amygdala by dorsal raphe stimulation: mediation through a direct serotonergic pathway. Brain Res. 1977;120:85–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way BM, Lacan G, Fairbanks LA, Melega WP. Architectonic distribution of the serotonin transporter within the orbitofrontal cortex of the vervet monkey. Neuroscience. 2007;148:937–948. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Grafton ST, Holmes CJ, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: I. General methods and intrasubject, intramodality validation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:139–152. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ, Poline JB, Friston KJ, Evans AC. Characterizing the response of PET and fMRI data using multivariate linear models. Neuroimage. 1997;6:305–319. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangrossi H, Jr., Viana MB, Zanoveli J, Bueno C, Nogueira RL, Graeff FG. Serotonergic regulation of inhibitory avoidance and one-way escape in the rat elevated T-maze. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:45–57. doi: 10.1109/42.906424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Endres CJ, Brasic JR, Huang SC, Wong DF. Linear regression with spatial constraint to generate parametric images of ligand-receptor dynamic PET studies with a simplified reference tissue model. Neuroimage. 2003;18:975–989. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.