Abstract

Aging is associated with a decline in immune function, which predisposes the elderly to higher incidence of infections. Information on the mechanism of age-related increase in susceptibility to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is limited. In particular, little is known regarding the involvement of the immune response in this age-related difference. We employed the streptomycin (STREP)-pretreated C57BL/6 mice to develop a mouse model that would demonstrate age-related difference in susceptibility and immune response to S. Typhimurium. In this model, old mice inoculated orally with 3×108 CFU or 1 ×106 CFU doses of S. Typhimurium had significantly greater S. Typhimurium colonization in ileum, colon, Peyer’s patches, spleen, and liver than those of young mice. Old mice had significantly higher weight loss than young mice on days 1 and 2 postinfection. In response to S. Typhimurium infection, the old mice failed to increase ex vivo production of IFN-γ and TNF-α in spleen and mesenteric lymph node cells to the same degree as those observed in the young mice, which was associated with their inability to maintain the presence of neutrophils and macrophages at a “youthful” level. These results indicate that STREP-pretreated C57BL/6 old mice are more susceptible to S. Typhimurium infection than young mice, which might be due to impaired IFN-γ and TNF-α production as well as the corresponding change in the number of neutrophils and macrophages in response to S. Typhimurium infection compared to young mice.

Introduction

Epidemiological, clinical, andanimal studies demonstrate that aged hosts have a higher incidence, severity, and mortality from infections than adult hosts (Pinner, Teutsch et al. 1996; Han, Wu et al. 2000; Yoshikawa 2000; Gay, Belisle et al. 2006). Statistics from the WHO demonstrated a 400-fold increase in mortality attributed to gastrointestinal infections in the elderly in comparison to the young adult population (Schmucker, Heyworth et al. 1996). Salmonella infection is one of the most common foodborne infections worldwide. It is estimated that 200 million to 1.3 billion cases of intestinal disease including 3 million deaths due to non-typhoidal Salmonella occur each year worldwide. An estimated 1.4 million non-typhoidal Salmonella infections, result in 168,000 visits to physicians, 15,000 hospitalizations and 580 deaths annually in the US (WHO 2005).

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is a facultative intracellular pathogen capable of surviving and replicating within macrophages (Mφ) and dendritic cells (DC). After oral infection S. Typhimurium colonizes the intestine and invades M cells and epithelial cells, and then colonizes the Peyer’s patch (PP), mesenteric lymph node (MLN) and disseminates to spleen and liver (Jones and Falkow 1996; Neutra, Frey et al. 1996). S. Typhimurium can evoke a non-systemic enterocolitis in humans and cattle. However, in Slc11a1-deficient mice (such as C57B/6 and BALB/c mice), S. Typhimurium causes a typhoid like disease, characterized by rapid multiplication of bacteria in liver and spleen but little intestinal pathology (Santos, Zhang et al. 2001). Nevertheless the animal models in which S. Typhimurium produces a disease similar to that in human are not suitable for studying the effect of age on S. Typhimurium resistance as the sufficient elderly animals in such models are not available. Barthel et al. (Barthel, Hapfelmeier et al. 2003) showed that 2 and 6 weeks old C57BL/6 mice that were pre-treated with streptomycin (STREP) and then exposed to 107 or108 CFU of S. Typhimurium exhibited pathologic changes that were similar to the intestinal inflammation caused by S. Typhimurium in humans. C57BL/6 mice are most commonly used in aging studies, thus we chose this strain to determine the suitability of STREP-pretreated mouse model for investigating the impact of aging on the host’s susceptibility to S. Typhimurium infection.

It is well-known that the immune response, particularly those that are mediated by T cells are impaired with aging (Engwerda, Fox et al. 1996; Schmucker, Thoreux et al. 2001; Haynes, Eaton et al. 2003). However, to date, there is no information available regarding the effect of age on resistance to S. Typhimurium infection in mouse model or the age-specific differences in the immune response to S. Typhimurium. This information is needed in order to determine the underlying mechanisms of age related increase in susceptibility to S. Typhimurium as well as development of strategies to combat it. Thus, the objective of this study was to develop a mouse model of S. Typhimurium infection for age-related studies, which would allow for obtaining further insight into the mechanism of age-related differences. We hypothesized that the aged mice would have lower resistance to oral challenge with S. Typhimurium and the difference in immune response between young and old mice contributs to this reduced resistance. In the present study, we used the STREP-pretreated mouse model (Barthel, Hapfelmeier et al. 2003) to characterize age-related differences in early stages of oral S. Typhimurium infection as well as in the immune response to S. Typhimurium infection.

Materials and Methods

Animals and bacterial strains

Young adult (4–6 months) and old (22–24 months) C57BL/6 male mice were obtained from the National Institute on Aging colonies at Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed individually at a constant temperature of 23°C with a 12-h light:dark cycle. Body weight was recorded daily. Animals were sacrificed by CO2 narcoses followed by exsanguination at the indicated time points postinfection (p.i.). The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University.

The wild-type strain S. Typhimurium SL1344 is naturally resistant to STREP. For inoculation, S. Typhimurium was grown with aeration in Luria-Bertoni (LB) broth overnight for 16 hours at 37°C with shaking. The concentration of bacteria was estimated using spectrophotometer. Bacteria were washed, resuspended and used to infect mice. The effective doses of bacteria administered were determined by plating serial dilutions of the inoculum on LB agar plates.

S. Typhimurium infection

To determine age-related difference in susceptibility to S. Typhimurium, young and old mice (11/group) were pre-adminstered STREP alone (uninfected animals) or pretreated with STREP and then administered S. Typhimurium by gavage as previously described (Barthel, Hapfelmeier et al. 2003). Briefly, water and food were withdrawn 4 h before oral administration of 20 mg of STREP in 150 μl of sterile water. Afterward, animals were supplied with water and food immediately. Twenty h after STREP treatment, water and food were withdrawn again for 4 h before the mice were administered with either 3.4×108 CFU or 1×106 CFU ST (200 μl suspension in PBS) orally. Thereafter, drinking water and food were offered ad libitum. Mice were monitored every day. Any animal that exhibited severe clinical abnormalities, became moribund, or lost 20% of initial body weight was sacrificed by CO2 narcoses followed by exsanguination. To determine the age-related difference in immune response to S. Typhimurium infection, STREP-pretreated mice (14–18/group) were infected with 1×106 CFU S. Typhimurium as described above. This lower dose was chosen for assessment of immune response as there was no statistically significant difference in colonization between the two doses.

Analysis of bacterial load in the intestinal contents, PP, MLN, spleen and liver

For S. Typhimurium infection, mice were sacrificed by CO2 narcoses followed by exsanguination at days 1, 2, or 4 p.i.. MLN, PP, spleen, and liver were harvested and placed into pre-weighed tubes with 1 ml of sterile PBS containing 15% glycerol. Ileum, cecum, and colon were aseptically removed and cut into pieces approximately 1 inch long. The content of each section was gently squeezed into the collection tubes using forceps. Intestinal tract content, MLN, PP, spleen, and liver were weighed and then mechanically homogenized using a Tissue Tearor apparatus (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK). Diluted homogenates in sterile PBS were plated on LB plates containing 200 μg ml−1 of STREP to quantify the S. Typhimurium as CFU g−1 tissues.

Lactoferrin assay

Fecal samples were collected right before mice were treated with STREP, which was 24 h prior to S. Typhimurium infection. This time point was designated as day −1 of infection. We then collected feces 24 h after STREP-treatment and before the mice were infected with S. Typhimurium. This time point was designated as day 0 of infection. In addition we collected fecal samples at days 3 and 4 following S. Typhimurium infection and these time points were designated as day 3 p.i. and day 4 p.i., respectively. Fecal samples were put into PBS containing 1 mg ml−1 deoxycholate and protease inhibitors and homogenized as described above. Lactoferrin levels were measured in fecal samples as previously described (Logsdon and Mecsas 2006). Levels of lactoferrin are expressed as ng lactoferrin g−1 feces.

Isolation of lymphocytes from spleen and MLN

To characterize the immune response, spleens and MLN were aseptically removed and placed in sterile complete RPMI 1640, which consists of RPMI 1640 (Biowhittaker, Walkerville, MD) media supplemented with 25 mmol HEPES L−1 (Invitrogen Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 2 mmol glutamine L−1 (Gibco), 1×105 units penicillin L−1, 100 mg STREP L −1 (Gibco) and gentamicin (50μg ml−1) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Single cell suspensions of MLN were prepared by gently forcing the tissue through a 70 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Splenocytes were prepared by gently disrupting spleens between two sterile frosted-glass slides then isolated via centrifugation (300 ×g). Red blood cells were lysed using Gey’s reagent. Cell preparations were washed twice with complete RPMI and total viable cell number was determined by trypan blue exclusion. The cells were suspended in complete RPMI containing heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) at appropriate densities for different experiments (see below). All the experiments were conducted under a condition of 37°C, atmosphere of 5% CO2, and 95% humidity unless indicated otherwise.

Determination of different cell types in spleen and MLN

The percentages of major cell types in spleen and MLN were determined by FACS analysis using the following anti-mouse antibodies (Abs): anti-CD3 (T cells), anti-NK-1.1 (NK cells), F4/80 (anti-BM8, Mφ), anti-Ly-6G (Gr-1, neutraphils), anti-CD11c (N418, dendritic cells). All mAbs were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For surface staining, 106 cells were stained with marker-specific fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate [FITC], phycoerythin (Guerrant, Araujo et al.), allophycocyanin [APC]-conjugated Abs, or appropriate isotype control Abs for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS) and were resuspended in FACS buffer. All samples were analyzed on a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences) using the software Summit 4.0 (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark).

Ex vivo cytokine production

Lymphocytes from spleen and MLN (5×106 cells/well) of control and S. Typhimurium-infected mice were cultured in 24-well culture plates (Becton Dickinson Labware) in the presence or absence of heat-killed-S. Typhimurium (HKS, 65°C 1h, at 2×108 CFU ml−1), concanavalin A (Con A; Sigma) at 5mg L−1 (for IFN-γ production), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma) at 5 mg L−1 (for TNF-α production) for 48 h. Cell-free supernatants were collected and stored at −70°C for later analysis of cytokines by ELISA (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Due to limitation in number of cells available from MLN, ex vivo cytokine production was not evaluated in response to HKS or medium alone.

Statistical analysis

The CFU were transformed to their log10 values prior to statistical analysis and are expressed graphically as log10 CFU g −1 of tissue. Bacterial counts less than 1 were given a value of 1 CFU g−1 for inclusion in analysis. Data which were not normally distributed (bacterial colonization and lactoferrin) were analyzed for the age differences by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis statistic test. The immunological data were analyzed for the age difference by Student’s t test. Significant differences were set at p < 0.05.

Results

Effect of age on tissue colonization following oral infection with S. Typhimurium

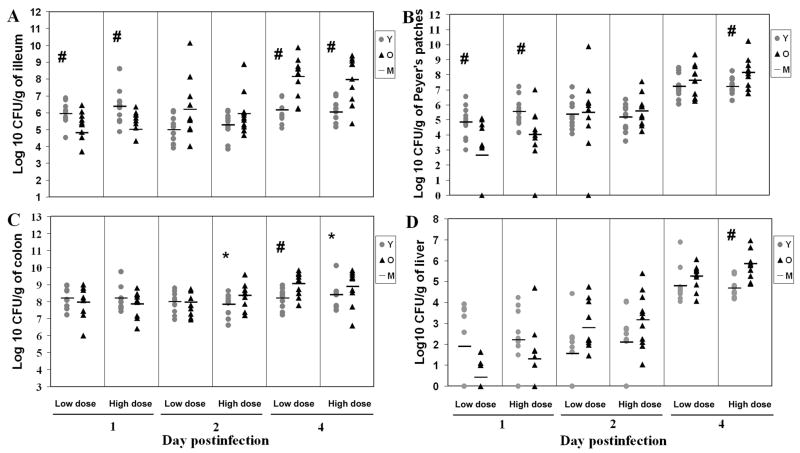

Young adult and aged mice were orally administered with two doses of S. Typhimurium, a low dose of 1×106 CFU and a high dose of 3.4×108 CFU S. Typhimurium. Bacterial colonization of the intestinal contents from the ileum, cecum and colon, as well as in the PP, MLN, spleen and liver were determined on days 1, 2 and 4 p.i.. Except for 2 old mice and 1 young mouse infected with high dose, all mice survived the course of infection. Overall, bacterial levels in the ileum were lower than those in the colon throughout the course of the infection. There was no significant effect of bacterial dose on the bacterial colonization (Fig. 1). At day 1 p.i., young mice had 13 and 22 fold higher colonization than old mice at low and high S. Typhimurium doses in the ileum, respectively (p<0.05). However, at day 4 p.i., old infected mice had 96 and 81 fold higher levels of colonization than young mice at low and high doses in the ileum, respectively (p<0.01) (Fig. 1a), indicating that old mice had less capability to control the bacteria multiplying than young mice at day 4 p.i. in the small intestine. Similar to the observation in ileum, the old mice infected with high bacterial dose exhibited 9 fold higher colonization in the PP at day 4 p.i. (p<0.05) although young mice infected with either low or high doses had significantly higher levels of mean colonization than old mice in PP at day 1 p.i. (p<0.05) (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Kinetic analysis of Salmonella typhimurium colonization in different tissues of streptomycin-pretreated young and old mice. Data represent CFU per gram of tissue in ileum (A), PP (B), colon (C), and liver (D) of mice infected with low dose (1×106 CFU) or high dose (3.4×108 CFU) of Salmonella typhimurium for 1, 2, or 4 days. Grey circle with Y represents young mice, black triangle with O represents old mice, level line with M represents mean of each group. # indicates that CFU recovered from young mice were significantly different from CFU recovered from old mice at p<0.05 and * indicates a similar trend at p<0.1 by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis statistic test, n=11/group, from 3 independent experiments.

Consistent colonization in colon was observed at days 1, 2, and 4 p.i. (range from 6.0 to 10.1 log CFU/gram) except for two young mice that were infected with the low bacterial dose at day 1 p.i.. As in the ileum, old mice infected with the low dose had significantly higher (7 fold) levels of colonization than young mice in colon at day 4 p.i. (p<0.01). A similar trend was observed for the high bacterial dose at days 2 and 4 p.i., but the differences did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06 and p=0.09, respectively) (Fig. 1c). No significant age-related difference was observed in bacterial colonization in cecum (data not shown).

The level of bacterial colonization in the MLN increased as the infection progressed in both young and old mice at either dose. However, there were no statistically significant age-related differences in the mean bacterial colonization in MLN at either dose or at any time point postinfection (data not shown).

Liver exhibited increased colonization as the infection progressed. At day 4 p.i. all livers exhibited colonization. The levels of colonization in old mice infected with high infectious dose were 14 fold higher than those of infected young mice (p<0.01) (Fig. 1d).

The levels of colonization in the spleen of both young and old mice increased from day 1 to day 4 p.i. and the spleen of old mice infected with the low bacterial dose exhibited a 10 fold higher bacterial levels at day 2 p.i. than those of young mice (p<0.05) (data not shown).

Overall, these data indicate that young mice are colonized at higher levels in the ileum and PP at day 1 p.i., but these mice are more efficient at controlling bacterial multiplication than old mice as the infection progresses. Similar results were observed at day 4 p.i. with colonization of colon and deeper tissues such as liver indicating higher systemic infection in old mice compared to young mice.

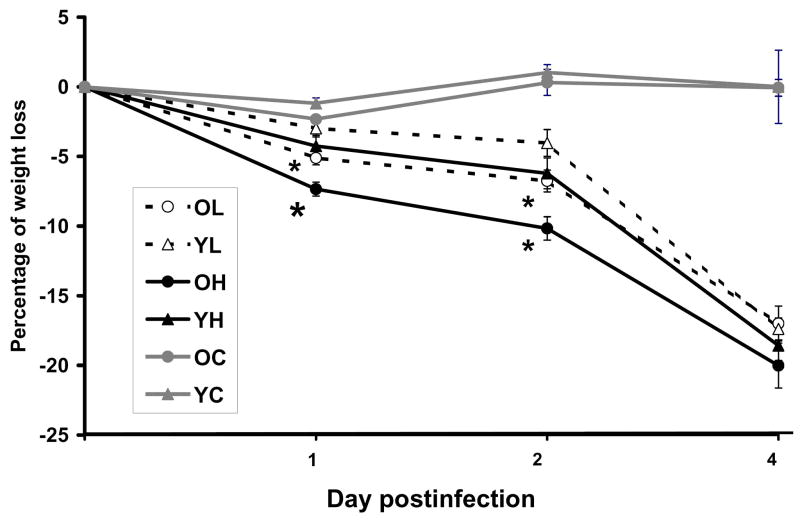

Effect of age on S. Typhimurium -infection-induced weight loss

Changes in percent body weight were monitored during the experiment to determine if the age-related difference observed in colonization is reflected in the health status of mice. As expected, an overall decrease in percent body weight was observed as the infection progressed. By days 2 and 4 p.i., all the infected groups had significantly greater weight loss than both uninfected young and old mice. However, At days 1 and 2 p.i., old mice infected with low or high dose S. Typhimurium lost significantly greater weight than the young mice infected with low or high dose S. Typhimurium mice, respectively (p<0.05) (Fig. 2). Old mice infected with high dose also had significantly greater percent weight loss than those infected with low dose (p<0.05). In summary, old mice lost significantly more weight during the early stage of infection (on days 1 and 2 p.i.) compared to young mice infected with either dose, which is consistent with the idea that old mice could not control the bacteria colonization as well as young mice.

Figure 2.

Effect of Salmonella typhimurium infection on weight loss in young and old mice. Percentage of weight loss in streptomycin-pretreated young and old mice infected with 3.4×108 CFU or 1×106 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium at days 1, 2, and 4 postinfection. n=11/group, from 3 independent experiments. * Indicates significantly greater percent weight loss than young infected mice of the same dose group at p<0.05. Blank circle with OL represents old mice infected with low dose. Blank triangle with YL represents young mice infected with low dose. Solid circle with OH represents old mice infected with high dose. Solid triangle with YH represents young mice infected with high dose. Grey circle with OC represents old uninfected mice. Grey triangle with YC represents young uninfected mice.

Effect of S. Typhimurium infection on fecal lactoferrin levels

Lactoferrin is abundantly expressed and secreted from glandular epithelial cells and is a prominent component of the secondary granules of neutrophils (Levay and Viljoen 1995; Baveye, Elass et al. 1999). During intestinal inflammation, neutrophils infiltrate the mucosa, resulting in an increased concentration of lactoferrin in feces (Guerrant, Araujo et al. 1992; Kane, Sandborn et al. 2003). Therefore we measured the levels of fecal lactoferrin as an indicator of intestinal inflammation.

There was no significant difference in lactoferrin level between young and old mice at baseline (24 hours prior to administration of STREP). Twenty four hours following oral administration of STREP, lactoferrin levels in both young and old uninfected (control) mice dropped significantly with no significant age-related difference. Lactoferrin levels increased following inoculation with S. Typhimurium in both young and old mice at days 3 and 4 p.i.. However, old mice infected with low dose of S. Typhimurium had significantly higher lactoferrin levels in feces compared to the young infected mice at day 4 p.i. (186±1.2 ng g−1 feces in old vs 72±1.4 ng g−1 feces in young mice, p<0.05) suggesting higher inflammation induced by S. Typhimurium in old mice compared to young mice (data not shown).

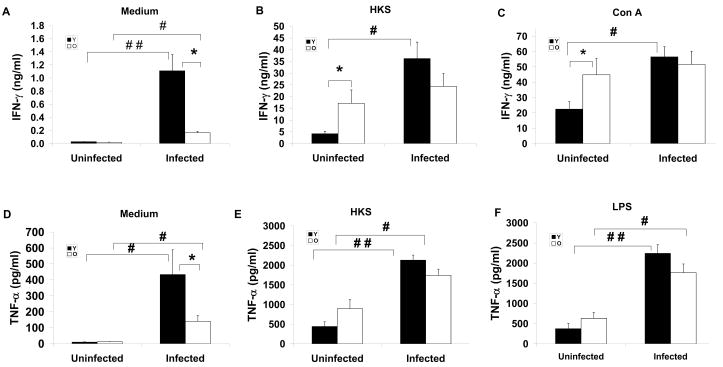

Cytokine response to S. Typhimurium infection

Because aging is associated with dysregulation of immune response, to explore the mechanism of age-related difference in S. Typhimurium infection, we examined the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in spleen and MLN. These cytokines were selected as they have been shown to play an important defensive role in response to S. Typhimurium infection (Tite, Dougan et al. 1991). Splenocytes and lymphocytes in MLN from uninfected or infected mice at day 4 p.i. were cultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of HKS, LPS or Con A for measurement of secreted cytokines in cultures using ELISA. Due to limited number of lymphocytes obtained from MLN, cytokine production was only measured in response to Con A or LPS. There was no significant difference in the levels of IFN-γ from unstimulated splenocytes between uninfected young and old mice, but splenocytes from old infected mice had significantly lower level of unstimulated IFN-γ production compared to splenocytes from young infected mice (Fig. 3a). While infection increased unstimulated IFN-γ production in both young and old mice, the infection-induced increase in INF-γ production was much higher in young compared to old mice (40 fold versus 9.5 fold in young versus old mice) (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b and Figure 3c show ex vivo IFN-γ production of splenocytes from uninfected and infected mice in response to HSK and Con A, respectively. Uninfected old mice had significantly higher production of IFN-γ in response to both stimuli than uninfected young mice. However, infected old mice failed to significantly increase their IFN-γ production following S. Typhimurium infection while young infected mice had a significantly greater IFN-γ production in response to HKS or Con A (1.4 and 1.1 fold higher in old infected mice compared to old uninfected mice vs 8.6 and 2.5 fold higher IFN-γ production in young infected mice compared to young uninfected mice in response to HKS and Con A, respectively). Similar results were observed in splenocyte TNF-α production in response to medium alone, HSK, or LPS (Fig. 3d, e, and f, respectively).

Figure 3.

Effect of Salmonella typhimurium infection on ex vivo cytokines production by splenocytes of streptomycin-pretreated young and old mice. IFN-γ (A, B, C), and TNF-α (D, E, F) production by splenocytes from young and old mice uninfected and infected with 1×106 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium at day 4 postinfection are shown. Splenocytes were stimulated with medium, heat-killed-Salmonella (HKS), Con A, or LPS for 48 h. Supernatant were collected and cytokines were measured by ELISA. (A) unstimulated IFN-γ. (B) HKS-stimulated IFN-γ. (C) Con A-stimulated IFN-γ, (D) unstimulated TNF-α, (E) HKS-stimulated TNF-α, (F) LPS-stimulated TNF-α. Solid bars with Y represent young mice and blank bars with O represent old mice. * indicates significant difference between young and old mice in the same infection group at p<0.05 by Student’s t test. #, and ## indicates significant difference between uninfected and infected mice in their respective age groups at p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively using Student’s t test. Data are mean± SE, n=14 –18/group from 2 independent experiments.

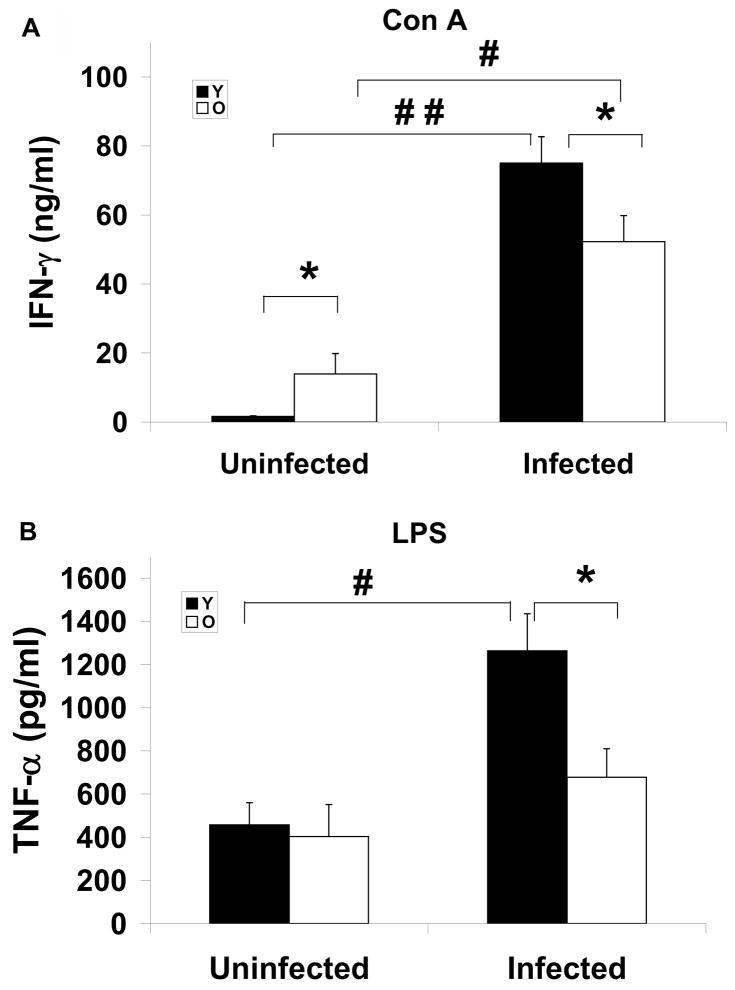

Similar to the observation in spleen, MLN from uninfected old mice had significantly higher level of IFN-γ compared to young mice in response to Con A (Fig. 4a). While infection increased production of both cytokines in both young and old mice, the infected old mice produced significantly lower levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α than young mice (Fig. 4a, b). In summary, old mice are significantly less capable of elevating IFN-γ and TNF-α production in their splenocytes and MLN compared to those of young mice after they are infected with S. Typhimurium.

Figure 4.

Effect of Salmonella typhimurium infection on ex vivo cytokine production in MLN. IFN-γ (A), and TNF-α (B) production in MLN from streptomycin-pretreated young and old mice uninfected and infected with 1×106 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium at day 4 postinfection are shown. Lymphocytes in MLN were stimulated with Con A or LPS for 48 h. Supernatant were collected and cytokines were measured by ELISA. (A) Con A-stimulated IFN-γ (B) LPS-stimulated TNF-α. Solid bars with Y represent young mice and blank bars with O represent old mice. * indicates significant age-related difference in uninfected or infected mice at p<0.05 using Student’s t test. #, and ## indicate significant difference between uninfected and infected mice in their respective age groups at p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively using Student’s t test. Data are mean± SE, n=14 –18/group from 2 independent experiments.

Changes in lymphoid cell populations in spleen and MLN in response to S. Typhimurium infection

To determine whether changes in TNF-α and IFN-γ production could be a reflection of changes in the cell numbers that produce these cytokines, we analyzed cell populations in spleen and MLN. Although the earlier studies have indicated that IFN-γ is primarily produced by NK and T cells in early and late stages of S. Typhimurium infection and TNF-α is primarily produced by Mφ (Nauciel and Espinasse-Maes 1992; Lalmanach and Lantier 1999), a recent study indicated that dominant sources of IFN-γ and TNF-α were Mφ and neutrophils in the early stage of S. Typhimurium infection (Kirby, Yrlid et al. 2002). Therefore, we determined the percentage of Mφ, neutrophils, T cells, and NK cells in spleen and MLN from uninfected and infected mice (Table 1, and data not shown). Given the size variation in the spleens of old mice which ranged from 0.04 to 0.29 grams, the percentage of cells per spleen was used rather than the total numbers.

Table 1.

Effect of age and Salmonella typhimurium infection on the percentage of spleen and MLN cell sub-population

| Spleen (%) |

MLN (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young |

Old |

Young |

Old |

|||||

| uninfected | infected | uninfected | infected | uninfected | infected | uninfected | infected | |

| neutrophil | 2.8±0.5 | 4.6±0.4# | 5.4±0.9** | 6.4±0.6* | 2.5±0.2 | 4.2±0.4# | 9.6±1.9* | 11.5±1.4* |

| Mφ | 2.8±0.3 | 2.7±0.3 | 6.2±1.0* | 4.1±0.5* # | 1.1±0.5 | 1.4±0.3 | 2.2±0.8 | 1.1±0.2# |

Streptomycin-pretreated young and old mice were administered with PBS or infected with 1×106 CFU of Salmonella typhimurium in PBS at day 4 postinfection. The percent of neutrophils and Mφ in spleen and MLN from uninfected and infected mice was analyzed by FACS.

indicates significant difference between uninfected and infected mice in their respective age groups at p<0.05 using Student’s t test.

indicate significant age-related difference in uninfected or infected mice at p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively using Student’s t test. Data are mean±SE of percent of cells, n=11/group, from 2 independent experiments.

Spleens and MLN from both uninfected and infected old mice had significantly higher percentage of neutrophils compared to their respective groups in young mice (Table 1). However, while young mice showed a significant increase in percentage of neutrophils in response to S. Typhimurium infection in both spleen and MLN (2.8±0.5 vs 4.6±0.4, in spleen and 2.5±0.2 vs 4.2±0.4 in MLN of uninfected and infected mice, respectively, p<0.05), there was no significant increase in percentage of neutrophils in spleen or MLN of old mice (5.4±0.9 vs 6.4±0.6 in spleen and 9.6±1.9 vs 11.5±1.4 in MLN of uninfected and infected old mice, respectively) (Table 1). Similar results were observed in percentage of Mφ in spleen. Spleens of old mice had significantly higher percentage of Mφ than those of young mice in both uninfected and infected mice (Table 1). However, while the percent of Mφ in the spleens of young mice did not change in response to S. Typhimurium infection, spleens from old mice infected with S. Typhimurium had significantly lower percent of Mφ compared to uninfected mice (2.8±0.3 vs 2.7±0.3 in uninfected and infected young and 6.2±1.0 vs 4.1±0.5 in uninfected and infected old mice, respectively, p<0.05). In MLN, there was no significant age-related difference in percent of Mφ in uninfected or infected mice (Table 1). However, while no significant change in the percent of MLN Mφ was observed in the young mice (1.1±0.5 vs 1.4±0.3 in uninfected and infected young mice, respectively), MLN of old mice infected with S. Typhimurium had significantly lower percentage of Mφ compare to uninfected mice (2.2±0.8 vs 1.1±0.2 in uninfected and infected mice, respectively, p<0.05) (Table 1). Similar results were obtained when the total number of Mφ and neutrophils in spleen and MLN were examined (data not shown).

No significant age-related difference in percentage of T and NK cells in spleen or MLN was observed in uninfected or infected mice except that infected old mice had higher percentage of NK cells in MLN than infected young mice (data not shown). These data suggest that the inability of the old mice to increase or maintain the percent of neutrophils and Mφ in response to S. Typhimurium in the immune organs might contribute to their reduced ability to increase TNF-α and IFN-γ production in response to S. Typhimurium compared to those of young mice.

Discussion

Aging is associated with higher morbidity and mortality from S. Typhimurium infection, however, the underlying mechanism of this age-related difference is not well understood. In particular little is known regarding the role of the immune response in this regard. This is in part due to lack of an appropriate rodent model for which old age groups are available to study the age-related differences. In this study, we employed the STRP-pretreated C57BL/6 mice to develop a mouse model that demonstrates age-related difference in susceptibility to S. Typhimurium. Furthermore, we explored the underlying mechanisms as it relates to the immune response.

A normal murine intestine infected by S. Typhimurium is resistant to colonization (Santos, Zhang et al. 2001) but STRP-resistant S. Typhimurium can trigger severe acute diffuse inflammation of cecum and colon (colitis) in the STRP-pretreated murine model, which more closely resembles the symptoms observed in humans (Barthel, Hapfelmeier et al. 2003). This model has been used to study S. Typhimurium infection in young mice (2 months old), and the results showed an intestinal inflammation and measurable tissue colonization at day 2 p.i., could be induced using S. Typhimurium at approximately 107 CFU (Barthel, Hapfelmeier et al. 2003). Based on this, we used the doses of 106 and108 CFU in the present study and found significant colonization at both doses suggesting that STRP-treatment increased the susceptibility to orally induced S. Typhimurium infection. Using the STRP-treated mouse model, we demonstrate, for the first time, that old mice have significantly higher morbidity compared to adult mice as demonstrated by higher tissue colonization and higher weight loss following S. Typhimurium infection. Thus, this animal model can be used to determine the underlying mechanisms of age-related differences in susceptibility to S. Typhimurium as well as for development of strategies to combat it.

To explore the underlying mechanism for the differences in infectivity of S. Typhimurium between young and old mice, we examined immune response in spleen and MLN from uninfected or infected mice. After oral infection, the first cells encountered by S. Typhimurium are intestinal epithelial cells, DC, and Mφ. Interaction with these cells leads to the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines resulting in influx of neutrophils, Mφ, and immature DC. IFN-γ acts in synergy with TNF-α to trigger an efficient bactericidal activity of the Mφ and connects the innate immunity with the acquired immune response mediated by T and B cells (Nauciel and Espinasse-Maes 1992; Lalmanach and Lantier 1999). However, there is no information available regarding the cytokine production in old mice infected with S. Typhimurium. Our data showed that the levels of unstimulated TNF-α and IFN-γ from spleen were not significantly different between uninfected young and old mice However, old mice were not able to increase their ex vivo production of unstimulated IFN-γ or TNF-α in response to S. Typhimurium infection, to the same level as those of young mice so that the old infected mice had significantly less splenocyte production of IFN-γ and TNF-α compared to young mice. Similarly, old mice exhibited significantly less ability to increase ex vivo stimulated IFN-γ and TNF-α production by splenocytes and MLN compared to those of young mice after they were infected with S. Typhimurium. The inability of old mice to increase TNF-α and IFN-γ production in response to S. Typhimurium could contribute to the higher bacterial colonization in old mice. TNF-α in infected mice could enhance bactericidal activity synergistically with IFN-γ and trigger nitric oxide production (Tite, Dougan et al. 1991). The lower level of TNF-α in the old infected mice could reflect the lower ability to defend against infection and result in higher susceptibility of old mice to S. Typhimurium as indicated by higher bacterial colonization in many tissues. No other information on age-related changes in cytokine levels in response to S. Typhimurium is available, however the impaired immune response to S. Typhimurium infection in aged mice in this study is consistent with observations by others of decreased T helper 1 cytokines production in old mice following Candida albicans (Murciano, Villamon et al. 2006) and influenza infection (Han, Wu et al. 2000).

To determine the underlying causes of age-related reduction in TNF-α and IFN-γ, we determined age-associated alterations in immune cells known to be the producers of these cytokines. The number of immune cells can directly or indirectly influence immune function and alter the outcome of infection. Earlier report had indicated NK and T cells to be the main producers of IFN-γ in response to S. Typhimurium infection. However, we did not observe a significant age-related difference in the percent of T cells and NK cells in spleen and infected old mice had slightly higher percentage of NK cells in MLN than young mice, which suggest that the age-related difference in IFN-γ production was not due to the changes in the percent of NK and T cells with age. One explanation, based on a recent report (Kirby, Yrlid et al. 2002), is that in this model, the NK cells and T cells are not predominant source of IFN-γ production compared to neutrophils and Mφ. This latter observation suggest that the inability of old mice to increase IFN-γ production to youthful levels following S. Typhimurium infection might be due to their inability to mount a significant change in the percentage of neutrophils and Mφ in response to this pathogen. Another possibility is that age-related functional changes but not the change in percent of NK and T cell might contribute to the inability of old mice to mount an effective IFN-γ response following S. Typhimurium infection. Further studies are needed to determine the contribution of functional changes in NK cells and T cells to age-related altered IFN-γ production in response to S. Typhimurium infection.

Mφ have been shown to be the predominant source of TNF-α in response to S. Typhimurium (Conlan 1996; Conlan 1997; Vassiloyanakopoulos, Okamoto et al. 1998), furthermore, a recent study(Kirby, Yrlid et al. 2002), showed that neutrophils can also contribute to TNF-α production in early stages of S. Typhimurium infection. Age-related changes in profile of different cells of the innate immune response have been reported including increased monocyte/Mφ cell numbers in mice (Mocchegiani and Malavolta 2004; Plackett, Boehmer et al. 2004). We show that both uninfected and infected old mice have higher percent of neutrophils and Mφ in spleen compared to young mice. MLN of old infected mice had significantly higher percent of neutrophils compared to those in young mice. These age-related differences in cell population do not readily explain the higher susceptibility of old mice to S. Typhimurium infection or the lower production of TNF-α. However, on closer inspection we noted that the pattern of change in response to infection is influenced by age and might contribute to the higher susceptibility of old mice to S. Typhimurium. Of particular interest is the observation that in young mice, there is a significant increase in percentage of neutrophils after infection, while no such increase is observed in old mice. Furthermore, while there was no change in percentage of Mφ of young mice, old mice exhibited a significant decrease in percentage of Mφ following infection. Given the important role that neutrophils and Mφ play in IFN-γ and TNF-α production in early stages of S. Typhimurium infection, the age-related difference in pattern of change observed in these cells following S. Typhimurium infection could be a contributing factor to the impaired IFN-γ and TNF-α production in response to S. Typhimurium infection in the aged mice. These cellular differences could also contribute to higher susceptibility of the aged to S. Typhimurium through other mechanisms. The impact of aging on Mφ functions has been well documented. For instance, the age-related deficit in Toll-like receptor (TLR) function as evidenced by reduced cytokine secretion, could be associated with the loss of TLR expression or another component of the receptor complex (Renshaw, Rockwell et al. 2002). However, another study failed to see age-dependent differences in cell-surface expression of TLR4 (Chelvarajan, Collins et al. 2005). Reduced phagocytosis and nitric oxide and superoxide production with age have also been documented (De la Fuente, Medina et al. 2000; Rosenberger, Gallo et al. 2004). In addition, Mφ are cellular hosts to S. Typhimurium during infection and S. Typhimurium can induce programmed cell death in Mφ (Monack, Raupach et al. 1996; Hueffer and Galan 2004), which can contribute to reduction in the number of Mφ following infection in old mice.

We observed a higher level of lactoferrin production in feces from old infected mice compared to those from young mice. This agrees with the higher overall percent of neutrophils in old mice compared to young mice. It is, however, interesting to note that unlike young mice, old mice did not exhibit a significant increase in percent of neutrophils in response to S. Typhimurium infection. This, together with lower levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ, suggests that despite the higher number of neutrophils in old mice, they are not functional and lack the ability to mount an effective response to S. Typhimurium.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that STREP-treated C57BL/6 mice can be used as an animal model to study the effect of age on resistance to S. Typhimurium infection. Our observations demonstrated that old mice infected with S. Typhimurium had higher bacterial loading in the ileum, colon, PP, spleen, liver, as well as greater weight loss than young infected mice. The higher susceptibility of aged mice to S. Typhimurium infection could be due to their decreased ability to effectively increase their production of IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to S. Typhimurium as well as to maintain the number of Mφ and neutrophils at a “youthful” level following infection. Further work is required to more definitively determine the role of IFN-γ and TNF-α as well as Mφ and neutrophils in the higher susceptibility of the aged to S. Typhimurium. Furthermore, the role of the adaptive immune response in control of the late stage of S. Typhimurium infection in the context of aging needs to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the US Departmentof Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service (58-1950-7-707); National Institutes of Health (AI056068) to Joan Mecsas and Lauren Logsdon.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an author manuscript that has been accepted for publication in Journal of Medical Microbiology, copyright Society for General Microbiology, but has not been copy-edited, formatted or proofed. Cite this article as appearing in Journal of Medical Microbiology. This version of the manuscript may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the rule of ‘Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials’ (section 17, Title 17, US Code), without permission from the copyright owner, Society for General Microbiology. The Society for General Microbiology disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by any other parties. The final copy-edited, published article, which is the version of record, can be found at http://jmm.sgmjournals.org, and is freely available without a subscription.

References

- Barthel M, Hapfelmeier S, et al. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect Immun. 2003;71(5):2839–58. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2839-2858.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baveye S, Elass E, et al. Lactoferrin: a multifunctional glycoprotein involved in the modulation of the inflammatory process. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37(3):281–6. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelvarajan RL, Collins SM, et al. The unresponsiveness of aged mice to polysaccharide antigens is a result of a defect in macrophage function. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77(4):503–12. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan JW. Neutrophils prevent extracellular colonization of the liver microvasculature by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1996;64(3):1043–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.1043-1047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan JW. Critical roles of neutrophils in host defense against experimental systemic infections of mice by Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1997;65(2):630–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.630-635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente M, Medina S, et al. Effect of aging on the modulation of macrophage functions by neuropeptides. Life Sci. 2000;67(17):2125–35. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engwerda CR, Fox BS, et al. Cytokine production by T lymphocytes from young and aged mice. J Immunol. 1996;156(10):3621–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay RT, Belisle S, et al. An aged host promotes the evolution of avirulent coxsackievirus into a virulent strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(37):13825–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605507103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant RL, Araujo V, et al. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(5):1238–42. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1238-1242.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SN, Wu D, et al. Vitamin E supplementation increases T helper 1 cytokine production in old mice infected with influenza virus. Immunology. 2000;100(4):487–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes L, Eaton SM, et al. CD4 T cell memory derived from young naive cells functions well into old age, but memory generated from aged naive cells functions poorly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433717100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueffer K, Galan JE. Salmonella-induced macrophage death: multiple mechanisms, different outcomes. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6(11):1019–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane SV, Sandborn WJ, et al. Fecal lactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker in identifying intestinal inflammation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1309–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AC, Yrlid U, et al. The innate immune response differs in primary and secondary Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 2002;169(8):4450–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalmanach AC, Lantier F. Host cytokine response and resistance to Salmonella infection. Microbes Infect. 1999;1(9):719–26. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levay PF, Viljoen M. Lactoferrin: a general review. Haematologica. 1995;80(3):252–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon LK, Mecsas J. A non-invasive quantitative assay to measure murine intestinal inflammation using the neutrophil marker lactoferrin. J Immunol Methods. 2006;313(1–2):183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocchegiani E, Malavolta M. NK and NKT cell functions in immunosenescence. Aging Cell. 2004;3(4):177–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Raupach B, et al. Salmonella typhimurium invasion induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(18):9833–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murciano C, Villamon E, et al. Impaired immune response to Candida albicans in aged mice. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 12):1649–56. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauciel C, Espinasse-Maes F. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha in resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1992;60(2):450–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.450-454.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutra MR, Frey A, et al. Epithelial M cells: gateways for mucosal infection and immunization. Cell. 1996;86(3):345–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinner RW, Teutsch SM, et al. Trends in infectious diseases mortality in the United States. Jama. 1996;275(3):189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plackett TP, Boehmer ED, et al. Aging and innate immune cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76(2):291–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw M, Rockwell J, et al. Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):4697–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger CM, Gallo RL, et al. Interplay between antibacterial effectors: a macrophage antimicrobial peptide impairs intracellular Salmonella replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(8):2422–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304455101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RL, Zhang S, et al. Animal models of Salmonella infections: enteritis versus typhoid fever. Microbes Infect. 2001;3(14–15):1335–44. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker DL, Heyworth MF, et al. Impact of aging on gastrointestinal mucosal immunity. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(6):1183–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02088236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker DL, Thoreux K, et al. Aging impairs intestinal immunity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122(13):1397–411. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tite JP, Dougan G, et al. The involvement of tumor necrosis factor in immunity to Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 1991;147(9):3161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiloyanakopoulos AP, Okamoto S, et al. The crucial role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in resistance to Salmonella dublin infections in genetically susceptible and resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7676–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Health Organization Drug-resistant Salmonella. 2005 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs139/en/print.html.2005.who website.

- Yoshikawa TT. Epidemiology and unique aspects of aging and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(6):931–3. doi: 10.1086/313792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]