Abstract

Enamel development requires the strictly regulated spatiotemporal expression of genes encoding enamel matrix proteins. The mechanisms orchestrating the initiation and termination of gene transcription at each specific stage of amelogenesis are unknown. In this study, we identify cis-regulatory regions necessary for normal enamelin (Enam) expression. Sequence analysis of the Enam promoter 5′-noncoding region identified potentially important cis-regulatory elements located within 5.2 kb upstream of the Enam translation initiation site. DNA constructs containing 5.2 or 3.9 kb upstream of the Enam translation initiation site were linked to an LacZ reporter gene and used to generate transgenic mice. The 3.9-kb Enam-LacZ transgenic lines showed no expression in ameloblasts, but ectopic LacZ staining was detected in osteoblasts. In contrast, the 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ construct was sufficient to mimic the endogenous Enam ameloblast-specific expression pattern. Our study provides new insights into the molecular control of Enam cell- and stage-specific expression.

Keywords: Enam, cis-regulatory elements, Ameloblasts, Enamel proteins, Osteoblasts, Tissue-specific expression

Introduction

Dental enamel is produced through the secretions of highly specialized epithelial cells called ameloblasts [Smith, 1998], which create and maintain an extracellular milieu favorable for mineral deposition [Nanci, 2008]. Amelogenin, enamelin and ameloblastin are the major secretory products of ameloblasts [Fincham et al., 1999]. Severe enamel phenotypes have been demonstrated in mice with defective amelogenin (Amel) [Gibson et al., 2001; Prakash et al., 2005], enamelin (Enam) [Masuya et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2008] or ameloblastin (Ambn) [Fukumoto et al., 2004] genes. In humans, defects in AMELX cause X-linked amelogenesis imperfecta, while ENAM mutations cause autosomal dominant amelogenesis imperfecta [Hu and Yamakoshi, 2003; Stephanopoulos et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006].

Increasing evidence suggests that each enamel protein has specific properties that may correlate with unique functional roles. Amelogenin epitopes are relatively absent from the mineralization front where enamel crystals elongate [Orsini et al., 2001], while amelogenin ‘nanospheres’ [Fincham et al., 1994] appear to space enamel crystals and keep them in parallel arrays [Beniash et al., 2005; Margolis et al., 2006]. Ameloblastin (also called amelin or sheathlin) might maintain rod and interrod boundaries [Krebsbach et al., 1996; Hu et al., 1997b; Lyngstadaas, 2001] and contribute to ameloblast attachment to the enamel surface [Cerny et al., 1996; Fukumoto et al., 2004]. Intact (uncleaved) enamelin localizes to the mineralization front where it may be involved in crystal elongation, while its cleavage products accumulate in the deeper enamel and are thought to regulate crystal habit [Tanabe et al., 1990; Hu et al., 1997a]. This study focuses on enamelin.

Enamelin expression initiates in preameloblasts and continues throughout the secretory stage as demonstrated by in situ hybridization [Hu et al., 2001a], semiquantitative RT-PCR [Nagano et al., 2003] and X-gal histochemistry in the enamelin β-gal knockin mouse [Hu et al., 2008]. Enamelin expression is not detected in any other tissues during development. Execution of this spatially and temporally restricted pattern within ameloblasts is critical for the completion of amelogenesis, and perturbation of this expression results in abnormal enamel in mice and humans. However, it remains unknown how enamelin expression is initiated and maintained during ameloblast differentiation. The transcriptional regulation of amelogenin [Gibson et al., 1998; Gibson, 1999; Papagerakis et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 2000; Zhou and Snead, 2000; Papagerakis et al., 2003; Caton et al., 2005] has been investigated for a decade, but much less is known about the regulation of enamelin expression. Characterizing the enamelin cis-regulatory promoter region will give new insights into the molecular control of enamelin expression and will enhance our understanding of enamel formation under normal and pathological situations.

Methods

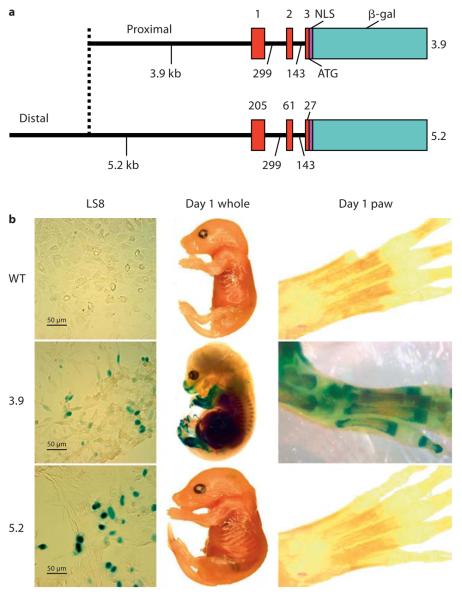

DNA Constructs and Detection of Enam-LacZ Activity in vitro

Two mouse Enam promoter fragments of different lengths were generated by PCR amplification using a previously isolated P1 clone as template [Hu et al., 2001b]. The following PCR primers used to generate the 3.9-kb fragment were forward 5′-GTCGACGGATCCAAAAACTTCTGCTCCCAG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTCCCGGGCACCAAAACTTTCATAAGCC-3′); the primers used to generate the 5.2-kb fragment were forward 5′-CAAACAGTCGACGTAACTACTACCTTTGAGGGCGGTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CAAACAGTCGACGTTTTCACCAAAACTTTCATAAGCC-3′. The amplification products were inserted into pLacZ [Dymecki, 1996] immediately 5′ to the nuclear localization sequence-β-galactosidase code and were used for transgenic mouse production (fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

The 3.9- and 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ reporter constructs and their transgenic expression. a The smaller construct (3.9-kb Enam-LacZ) contained 3,931 bp of Enam 5′ untranslated region extending from bases 1,555 to 5,485. The larger construct (5.2-kb Enam-LacZ) contained 5,217 bp of Enam from bases 269 to 5,485. Both Enam constructs contained the putative transcription initiation site at the start of exon 1 (at base 4,750) and the noncoding exons 1 and 2, as well as the beginning of exon 3 up to, but not including, the translation initiation site, which was supplied by the bacterial β-galactosidase cDNA (β-gal) fused to a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and followed by a downstream polyadenylation sequence. b Transient transfection in an ameloblastic cell line (LS8). Both the 3.9- and 5.2-kb constructs were sufficient to drive the expression of β-galactosidase in the nucleus of the LS8 line. Cells transfected with a promoterless LacZ construct lacked β-galactosidase staining (left panel). Whole embryo (center) and paw (right panel) from postnatal day 1 transgenic and wild-type (WT) mice showed no β-galactosidase expression for the wild-type mice, tooth-specific expression for the 5.2-kb transgenic mice and ec-topic bone expression for the 3.9-kb transgenic mice.

The 2 Enam-LacZ constructs (3.9 and 5.2 kb) were transiently transfected into the ameloblast-like cell line LS8 (kindly provided by Dr. M. Snead, Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology, USC, Los Angeles, Calif., USA) using a Lipofectamine 2000 transfection kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif., USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were plated in 6-well culture plates and transfection assays were performed when cells reached 70% confluence (1 μg of either the 3.9- or 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ or the LacZ DNA constructs, mixed with 6 μl of lipofectamine, was used for transfection within each separate well). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the media were removed, the cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS, fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde and assayed for β-galactosidase activity, as previously described [Yang et al., 2005]. Staining was evaluated and photographed using a dissecting microscope (SMZ1000; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and a digital camera (DXM1200; Nikon).

Generation of the 3.9- and 5.2-kb Enamelin-LacZ Hemizygotes Transgenic Mice

The 3.9- and 5.2-kb enamelin-LacZ DNA constructs were excised from the vector by restriction digestion, purified with a Qia-quick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Md., USA) and microinjected into fertilized CD1 eggs to generate transgenic mice. A total of 8 independent lines were generated at the Nathan Shock Aging Center at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and at the Transgenic Animal Model Core at the University of Michigan. Founders were bred with C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Me., USA). Tail DNA was used for genotyping by PCR and/or Southern blot analysis. All experimental procedures involving mice were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and University of Michigan Committees on the Use and Care of Animals. The in vivo activity of the Enam-LacZ constructs was determined using a standard protocol to detect β-galactosidase activity by X-gal staining tissue sections from newborn to mice at postnatal day 21 [Lawson et al., 1999].

The genotype of the 3.9-kb Enam-LacZ transgenic mice was determined by PCR analysis of genomic DNA using the primer pair forward 5′-AAGTTTTGGGATTTGGCTCA-3′ and reverse 5′-GTTGCACCACAGATGAAACG-3′. The 600-bp amplification product contained part of the enamelin promoter sequence, the coding sequence for the nuclear localization signal, and part of the bacterial β-galactosidase gene sequence.

Genotyping the 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ transgenic mice was accomplished by Southern blot hybridization using 100 μg of mouse tail DNA, digested to completion with the restriction enzyme BglII (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif., USA). The restricted genomic DNA was fractionated on 0.7% agarose gels and transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (No. 1-209-299; Roche, Indianapolis, Ind., USA). Randomly primed DNA probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Redivue deoxycytidine 5′-[α-32P] triphosphate, triethylammonium salt, AA0005, 10 μCi/μl, specific activity 3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Piscataway, N.J., USA) using a Random Primed DNA Labeling Kit (No. 1-004-760; Roche) and purified by Quick Spin Columns (radiolabeled DNA purification kit, No. 1-273-922 or 1-273-949; Roche). Denatured probe was added to the buffer at 107 cpm and hybridized overnight. Lowstringency washes involved two 5-min washes at room temperature with 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS followed by two 15-min high-stringency washes at 65 ° C in 5× SSC and 0.1% SDS. The blots were exposed to X-ray film (BioMax MR, 894-1114; Kodak, Rochester, N.Y., USA) with intensifying screens at −70 ° C overnight.

Detection of Enam-LacZ Activity in vivo

Tissues from newborn mice as well as mice at postnatal days 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 17 and 20 were collected immediately after sacrificing the animals. Whole bodies and/or heads were processed for β-galactosidase staining as previously described [Lu et al., 2005], and β-galactosidase staining was compared to the endogenous enamelin expression [Hu et al., 2000, 2001a].

For detection of the Enam-LacZ activity, tissue sections were postfixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS (3× for 5 min each), and incubated in freshly prepared X-gal staining buffer (1 mg/ml X-gal, 100 mM HEPES, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 1 mM MgCl2, 2% Triton X-100 and 5 mM DTT, pH 8.0) at 45 °C overnight. Tissue sections were then rinsed, counterstained with hematoxylin, and observed under a dissection microscope (SMZ1000; Nikon) or light microscope (Eclipse E600; Nikon) to determine the spatial and temporal activity of the enamelin-LacZ reporter constructs. All images were captured using a digital camera (DXM1200; Nikon) and Act1 imaging software (Mager Scientific, Dexter, Mich., USA).

Results

Enamelin-LacZ Activity in vitro

Positive β-galactosidase activity was detected in both 3.9- and 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ transfected LS8 ameloblast cells 48 h following transfection, demonstrating that both fragments contain the necessary basal promoter elements (fig. 1b). Staining was restricted to the nuclei, indicating specific expression of the nuclear-localized reporter molecule. LS8 cells transfected with the promoterless LacZ vector (control) showed no β-galactosidase activity (fig. 1b).

The 3.9- and 5.2-kb Enamelin-LacZ Mice

For the 3.9-kb Enam-LacZ transgene, 3 of 5 founders were productive. For the 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ transgene, 5 of 9 founders were productive. Offspring of the productive founders were evaluated for β-galactosidase expression using embryonic day 18 (E18) whole mounts (fig. 1b) and tissue sections from newborn to postnatal day 20 mice (fig. 2).

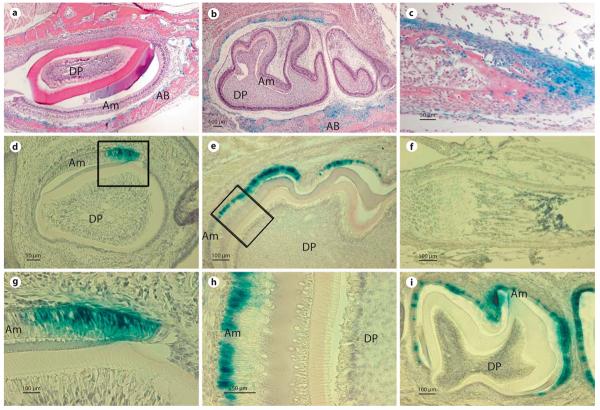

Fig. 2.

Comparison of β-galactosidase activity expressed by the 3.9- and 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ transgenes. a, b β-Galactosidase expression was not detected in ameloblasts (Am) or dental pulp (DP) cells of day 1 incisors (a) or day 1 and 5 molars (b). In contrast, β-galactosidase activity was detected in alveolar bone (AB) surrounding the incisors and molars. c At postnatal day 1, staining of long bones of the extremities is also distinct; mostly from the cells that encapsulate the developing long bones and joints. d–i β-Galactosidase activity was detected in ameloblasts (Am) of postnatal day 1 incisor (d, g). In molars, β-galactosidase reporter gene activity was not found in day 1 molars and it was first detected in the ameloblasts at postnatal day 5 (e, h). Positive staining of β-galactosidase activity specifically localized to the nuclei of the ameloblasts (g, h). The intensity of β-galactosidase activity peaked at postnatal day 9 and continued in maturation stage ameloblasts, being located within the nuclei until postnatal day 17 (i). Dental pulp (DP) and alveolar bone (AB) cells were devoid of staining. No β-galactosidase activity was detected in long bones of postnatal day 12 mice (f).

The 3.9-kb Enam-LacZ Activity in vivo

Whole mounts of E18 wild-type mice were negative (fig. 1b), while the 3.9-kb transgenic mice at the same stages of development showed ectopic β-galactosidase expression (fig. 1b). Staining in the craniofacial region was localized to the mandible, nasal region and papilla of the hair bulbs (fig. 1b). Preosteoblasts in the alveolar bone surrounding the developing incisors and molars of 1- and 5-day-old mice were positive for β-galactosidase staining, but no positive staining was observed within the incisors or molars themselves (fig. 2a, b). In addition, histological sections at day 1 showed β-galactosidase staining within the long bones of the extremities, primarily in cells encapsulating developing bones and joints (fig. 2c). These results contrast with the ameloblast-specific endogenous Enam mRNA localization, as defined by previous studies [Hu et al., 2001a]. These findings suggest that the 3.9-kb Enam sequence was sufficient to promote reporter expression, but insufficient to direct an ameloblast-specific expression. Characterization of the 3 independent 3.9-kb Enam-LacZ transgenic lines showed similar expression patterns that differed only in the intensity of the β-galactosidase staining (data not shown).

The 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ Activity in vivo

The nondental localization of reporter activity observed in the 3.9-kb Enam-LacZ transgenics contrasted strongly with the reporter activity in the 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ transgenics, which correlated well with endogenous Enam expression. Whole mounts of E18 5.2-kb mice were negative except for tooth and did not show staining in bone cells (fig. 1b). In postnatal tissue sections, β-galactosidase activity was initially detected in the secretory ameloblasts of day 1 incisors (fig. 2d, g), while the molars lacked reporter expression at this time. The 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ reporter activity was not detected in molar secretory ameloblasts until day 5 (fig. 2e, h). The 5.2-kb Enam-LacZ transgene expression in molars was strong in secretory and maturation stage ameloblast until postnatal day 14 (fig. 2i). β-Galactosidase staining was clearly detected within the nuclei of molar ameloblasts (fig. 2g, h), and persisted in a few ameloblasts until the molars erupted in 17-day-old mice (data not shown). No expression was detected in 20-day-old molars (data not shown). In addition, no staining was detected in any other tissues, like bone, liver and lung (fig. 2f). Compared with the Enam endogenous pattern (Hu et al., 2001a), the 5.2-kb construct directed tissue- and stage-specific expression of the reporter molecule that recapitulated Enam expression in vivo. The reporter activity varied depending upon which transgenic mouse line was characterized, but in the majority of mouse lines the expression of the reporter molecule clearly overlapped that of the endogenous enamelin mRNA expression.

Discussion

Dental mineralized tissues comprise enamel, dentin and cementum. Dentin and cementum share a similar repertoire of extracellular matrix proteins as bone. In contrast, enamel proteins are not normally found in bone cells, suggesting that regulatory mechanisms might exist that prevent their expression outside of enamel. To determine the necessary cis-regulatory promoter elements necessary for the spatiotemporal expression of enamelin in vivo, 3 transgenic lines were generated harboring 3.9 kb prior to the translation initiation codon (TIC) of the Enam linked to the reporter LacZ gene (3.9 kb). In addition, 5 independent transgenic lines were generated harboring 5.2 kb prior to the TIC (5.2 kb). The design of these 2 Enam-LacZ constructs (3.9 and 5.2 kb) was based upon sequence analysis of the human and mouse enamelin genes that suggested that the major regulatory regions governing enamelin expression are located within one or both of these Enam-regulatory regions. Our study reveals a cis-regulatory region that confers tooth-specific expression to the mouse Enam gene.

More specifically, in 3.9-kb mice, Enam-LacZ expression was dramatically downregulated in teeth, contrasting with the strong endogenous enamelin mRNA expression detected by in situ hybridization. Instead, enamelin-β-galactosidase activity was detected within preosteoblasts and chondrocytes, which were negative for endogenous Enam expression. Overall, the pattern exhibited by β-galactosidase activity was very different from endogenous enamelin expression, suggesting that the 3.9-kb fragment of the mouse Enam promoter lacks important regulatory elements essential for the ameloblast-specific expression of this gene.

In contrast to the results obtained with the 3.9-kb fragment, LacZ reporter mice harboring 5.2 kb of the Enam gene prior to the TIC showed β-galactosidase expression exclusively in ameloblasts in all 5 transgenic lines generated. However, within 2 of the 5 lines examined, the intensity of expression was relatively low when compared with endogenous Enam expression. Chromosomal position effects of the transgene integration site, and/or differences in the copy number of the transgene and/or the pattern of methylation of the CpG-rich regulatory sequences may cause variable expression levels between transgenic lines due to differences in chromatin structure modulation, as observed for other transgenes [Bestor and Tycko, 1996; Dobie et al., 1997]. Although we have not investigated in detail the exact reason for the observed differential intensity between the 5 independent transgenic lines, we are confident to conclude that the 5.2-kb reporter gene expression overlapped that of endogenous enamelin expression and well mimicked its tissue-specific pattern. Preservation of the essential aspects of enamelin tissue-specific expression from early to late amelogenesis indicates that critical elements for enamelin ameloblast expression are contained within the distal cis-regulatory region located between 5.2 and 3.9 kb upstream of the translation start site. Furthermore, this distal regulatory region may also contain negative regulatory elements that suppress enamelin expression in bone cells. Preliminary analysis of the potential binding trans-regulatory factors within this distal regulatory region (between 5.2 and 3.9 kb upstream of the translation start site) indicated that Runx2 and Dlx/Msx transcription factors might be good candidates for regulating enamelin expression during ameloblast differentiation. Runx2 and Msx/Dlx proteins are expressed by the ameloblasts concomitant with enamelin expression, and knockout mice and human genetics suggest that both Runx2 and Msx/Dlx proteins may play a role in controlling enamel formation [Price et al., 1998; D'Souza et al., 1999; Bei et al., 2004; Aioub et al., 2007].

While the molecular mechanisms governing tooth morphogenesis are being elucidated in detail [Thesleff and Sharpe, 1997], the genetic pathways controlling the specification of ameloblasts and enamel formation remain unclear. The terminal differentiation of ameloblasts starts during the late bell stage of tooth morphogenesis and is supposed to be regulated by reciprocal interactions between the epithelium and mesenchyme. Very little is known concerning the transcriptional mechanisms that regulate hard tissue formation in tooth. Our study provides new insights on the developmental- and tissue-specific expression of enamelin within the enamel-forming ameloblasts.

In conclusion, the 5.2-kb sequence upstream of the translation initiation site may contain the regulatory binding sites necessary for the control of the temporal and spatial expression of mouse Enam gene. To determine what specific sequences and corresponding transcription factors are critical for the tissue-specific expression of enamelin, in vitro promoter analysis and additional transgenic models are necessary. Nevertheless, our studies establish a framework for understanding the transcriptional regulation of enamel matrix proteins encoding genes within the ameloblasts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Snead for providing the LS8 ameloblast-like cell line. This study was funded by NIDCR/NIH grant projects DE011301 and DE015846.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- E18

embryonic day 18

- TIC

translation initiation codon

References

- Aioub M, Lezot F, Molla M, Castaneda B, Robert B, Goubin G, Nefussi JR, Berdal A. Msx2 −/− transgenic mice develop compound amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfecta and periodental osteopetrosis. Bone. 2007;41:851–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei M, Stowell S, Maas R. Msx2 controls ameloblast terminal differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:758–765. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E, Simmer JP, Margolis HC. The effect of recombinant mouse amelogenins on the formation and organization of hydroxyapatite crystals in vitro. J Struct Biol. 2005;149:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor TH, Tycko B. Creation of genomic methylation patterns. Nat Genet. 1996;12:363–367. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caton J, Bringas P, Jr., Zeichner-David M. IGFs increase enamel formation by inducing expression of enamel mineralizing specific genes. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny R, Slaby I, Hammarstrom L, Wurtz T. A novel gene expressed in rat ameloblasts codes for proteins with cell binding domains. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:883–891. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza RN, Aberg T, Gaikwad J, Cavender A, Owen M, Karsenty G, Thesleff I. Cbfa1 is required for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions regulating tooth development in mice. Development. 1999;126:2911–2920. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.13.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie K, Mehtali M, McClenaghan M, Lathe R. Variegated gene expression in mice. Trends Genet. 1997;13:127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymecki S. A modular set of Flp, FRT and lacZ fusion vectors for manipulating genes by site-specific recombination. Gene. 1996;171:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, Simmer JP. The structural biology of the developing dental enamel matrix. J Struct Biol. 1999;126:270–299. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, Simmer JP, Sarte P, Lau EC, Diekwisch T, Slavkin HC. Self-assembly of a recombinant amelogenin protein generates supramolecular structures. J Struct Biol. 1994;112:103–109. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1994.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Kiba T, Hall B, Iehara N, Nakamura T, Longenecker G, Krebsbach PH, Nanci A, Kulkarni AB, Yamada Y. Ameloblastin is a cell adhesion molecule required for maintaining the differentiation state of ameloblasts. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:973–983. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CW. Regulation of amelogenin gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Exp. 1999;9:45–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CW, Collier PM, Yuan ZA, Chen E. DNA sequences of amelogenin genes provide clues to regulation of expression. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998;106(suppl 1):292–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1998.tb02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CW, Yuan ZA, Hall B, Longenecker G, Chen E, Thyagarajan T, Sreenath T, Wright JT, Decker S, Piddington R, Harrison G, Kulkarni AB. Amelogenin-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31871–31875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CC, Fukae M, Uchida T, Qian Q, Zhang CH, Ryu OH, Tanabe T, Yamakoshi Y, Murakami C, Dohi N, Shimizu M, Simmer JP. Cloning and characterization of porcine enamelin mRNAs. J Dent Res. 1997a;76:1720–1729. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760110201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CC, Fukae M, Uchida T, Qian Q, Zhang CH, Ryu OH, Tanabe T, Yamakoshi Y, Murakami C, Dohi N, Shimizu M, Simmer JP. Sheathlin: cloning, cDNA/polypeptide sequences, and immunolocalization of porcine enamel proteins concentrated in the sheath space. J Dent Res. 1997b;76:648–657. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760020501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CC, Hart TC, Dupont BR, Chen JJ, Sun X, Qian Q, Zhang CH, Jiang H, Mattern VL, Wright JT, Simmer JP. Cloning human enamelin cDNA, chromosomal localization, and analysis of expression during tooth development. J Dent Res. 2000;79:912–919. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Sun X, Zhang C, Simmer JP. A comparison of enamelin and amelogenin expression in developing mouse molars. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001a;109:125–132. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Yamakoshi Y. Enamelin and autosomal-dominant amelogenesis imperfecta. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:387–398. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Zhang CH, Yang Y, Karrman-Mardh C, Forsman-Semb K, Simmer JP. Cloning and characterization of the mouse and human enamelin genes. J Dent Res. 2001b;80:898–902. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800031001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JCC, Hu Y, Smith CE, McKee MD, Wright JT, Yamakoshi Y, Papagerakis P, Hunter GK, Feng JQ, Yamakoshi F, Simmer JP. Enamel defects and ameloblast-specific expression in enamelin knock-out/LacZ knock-in mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10858–10871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710565200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Simmer JP, Lin BP, Seymen F, Bartlett JD, Hu JC. Mutational analysis of candidate genes in 24 amelogenesis imperfecta families. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114(suppl 1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebsbach PH, Lee SK, Matsuki Y, Kozak CA, Yamada K, Yamada Y. Full-length sequence, localization, and chromosomal mapping of ameloblastin: a novel tooth-specific gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4431–4435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson KA, Dunn NR, Roelen BA, Zeinstra LM, Davis AM, Wright CV, Korving JP, Hogan BL. Bmp4 is required for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1999;13:424–436. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhang S, Xie Y, Pi Y, Feng JQ. Differential regulation of dentin matrix protein 1 expression during odontogenesis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;181:241–247. doi: 10.1159/000091385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngstadaas S. Synthetic hammerhead ribozymes as tools in gene expression. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12:469–478. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis HC, Beniash E, Fowler CE. Role of macromolecular assembly of enamel matrix proteins in enamel formation. J Dent Res. 2006;85:775–793. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuya H, Shimizu K, Sezutsu H, Sakuraba Y, Nagano J, Shimizu A, Fujimoto N, Kawai A, Miura I, Kaneda H, Kobayashi K, Ishijima J, Maeda T, Gondo Y, Noda T, Wakana S, Shiroishi T. Enamelin (Enam) is essential for amelogenesis: ENU-induced mouse mutants as models for different clinical subtypes of human amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:575–583. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T, Oida S, Ando H, Gomi K, Arai T, Fukae M. Relative levels of mRNA encoding enamel proteins in enamel organ epithelia and odontoblasts. J Dent Res. 2003;82:982–986. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanci A, editor. Ten Cate's Oral Histology Development, Structure, and Function. Mosby; St. Louis: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini G, Lavoie P, Smith C, Nanci A. Immunochemical characterization of a chicken egg yolk antibody to secretory forms of rat incisor amelogenin. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:285–292. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagerakis P, Hotton D, Lezot F, Brookes S, Bonass W, Robinson C, Forest N, Berdal A. Evidence for regulation of amelogenin gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in vivo. J Cell Biochem. 1999;76:194–205. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(20000201)76:2<194::aid-jcb4>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagerakis P, MacDougall M, Hotton D, Bailleul-Forestier I, Oboeuf M, Berdal A. Expression of amelogenin in odontoblasts. Bone. 2003;32:228–240. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00978-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash SK, Gibson CW, Wright JT, Boyd C, Cormier T, Sierra R, Li Y, Abrams WR, Aragon MA, Yuan ZA, van den Veyver IB. Tooth enamel defects in mice with a deletion at the Arhgap 6/Amel X locus. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77:23–29. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-1213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JA, Bowden DW, Hart TC. Identification of a CA/TG repeat polymorphism proximal to the human DLX3 gene. Hum Hered. 1998;48:288–290. doi: 10.1159/000022818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE. Cellular and chemical events during enamel maturation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:128–161. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanopoulos G, Garefalaki ME, Lyroudia K. Genes and related proteins involved in amelogenesis imperfecta. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1117–1126. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Aoba T, Moreno EC, Fukae M, Shimizu M. Properties of phosphorylated 32 kD nonamelogenin proteins isolated from porcine secretory enamel. Calcif Tissue Int. 1990;46:205–215. doi: 10.1007/BF02555046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thesleff I, Sharpe P. Signalling networks regulating dental development. Mech Dev. 1997;67:111–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Lu Y, Kalajzic I, Guo D, Harris MA, Gluhak-Heinrich J, Kotha S, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ, Rowe DW, Turner CH, Robling AG, Harris SE. Dentin matrix protein 1 gene cis-regulation: use in osteocytes to characterize local responses to mechanical loading in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20680–20690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YL, Lei Y, Snead ML. Functional antagonism between Msx2 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α in regulating the mouse amelogenin gene expression is mediated by protein-protein interaction. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29066–29075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YL, Snead ML. Identification of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α as a transactivator of the mouse amelogenin gene. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12273–12280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]