Abstract

Background

Human “loss-of-function” variants of ANK2 (ankyrin-B) are linked to arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. However, their in vivo effects and specific arrhythmogenic pathways have not been fully elucidated.

Methods

We identified new ANK2 variants in 25 unrelated Han Chinese probands with ventricular tachycardia by whole exome sequencing. The potential pathogenic variants were validated by Sanger sequencing. We performed functional and mechanistic experiments in ankyrin-B knock-in (KI) mouse models and in single myocytes isolated from KI hearts.

Results

We detected a rare, heterozygous ANK2 variant (p.Q1283H) in a proband with recurrent ventricular tachycardia. This variant was localized to the ZU5C region of ANK2, where no variants have been previously reported. KI mice harboring the p.Q1283H variant exhibited an increased predisposition to ventricular arrhythmias following catecholaminergic stress in the absence of cardiac structural abnormalities. Functional studies illustrated an increased frequency of delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and Ca2+ waves and sparks accompanied by a decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content in KI cardiomyocytes upon isoproterenol stimulation. The immunoblotting results showed increased levels of phosphorylated ryanodine receptor (RyR2) Ser2814 in the KI hearts, which was further amplified upon isoproterenol stimulation. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated dissociation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) from RyR2 in the KI hearts, which was accompanied by a decreased binding of ankyrin-B to PP2A regulatory subunit B56α. Finally, the administration of metoprolol or flecainide decreased the incidence of stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias in the KI mice.

Conclusions

ANK2 p.Q1283H is a “disease-associated” variant that confers susceptibility to stress-induced arrhythmias, which may be prevented by the administration of metoprolol or flecainide. This variant is associated with the loss of PP2A activity, the increased phosphorylation of RyR2, exaggerated DAD-mediated trigger activity and arrhythmogenesis.

Keywords: ankyrin-B, variant, protein phosphatase 2A, ryanodine receptor, catecholamine, arrhythmia

Introduction

Ankyrin-B (AnkB, encoded by ANK2) refers to the ankyrin member responsible for the targeting of integral membrane proteins to specialized cellular compartments or organelles.1–4 Canonical AnkB consists of a highly conserved N-terminal membrane-binding domain (MBD) with 24 ANK repeats, a spectrin-binding domain (SBD) with a ZU5N-ZU5C-UPA tandem, and a regulatory domain (RD) composed of a death domain (DD) and a variable C-terminal domain (CTD). In the SBD, ZU5N interacts with spectrin, thereby linking MBD-associated binding partners to the spectrin/actin-based cytoskeleton, whereas the function of ZU5C and UPA are still poorly defined.5 Human “loss-of-function” ANK2 variants as well as variants that decrease AnkB expression have been linked to a wide spectrum of arrhythmias termed “ankyrin-B syndrome,”1, 2 such as sinus node dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, long QT syndrome, ventricular tachycardia (VT), idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and sudden cardiac death (SCD).4 In vitro studies have shown that cellular afterdepolarizations and extrasystoles due to abnormal Ca2+ cycling are the underlying causes of arrhythmogenesis.1, 3 However, no comprehensive studies have explored the in vivo effects and the precise arrhythmogenic mechanisms of ANK2 variants.

AnkB-deficient mice (AnkB+/−) display an arrhythmia phenotype similar to that in human ANK2 variant carriers, which is partly mediated by ryanodine receptor (RyR2)-associated sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release.3, 6 However, the specific molecular events leading to RyR2 hyperactivity have not been extensively studied. Protein phosphatase type 2A (PP2A), which has catalytic, scaffolding and regulatory subunits, can regulate the dephosphorylation of RyR2.7 Of the 13 PP2A regulatory subunits, B56α appears to control the phosphorylation state of RyR2.8, 9 Notably, AnkB is essential for targeting B56α,10 which tethers PP2A to the RyR2 complex.9 Herein, we hypothesize that ANK2 variants may promote the development of arrhythmias through the RyR-mediated remodeling of Ca2+ signaling by interfering with normal PP2A activity.

We performed genetic screening and identified a rare, heterozygous ANK2 variant (p.Q1283H) localized to ZU5C in a proband with VT. We generated knock-in (KI) mice carrying the p.Q1283H variant, which exhibited an increased predisposition to arrhythmias during epinephrine challenge. The phenotype could be prevented by the administration of metoprolol or flecainide. Cellular electrophysiology and Ca2+-imaging experiments in the KI cardiomyocytes demonstrated an increased frequency of delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and arrhythmogenic SR Ca2+ release under isoproterenol (ISO) stimulation. Immunoblots revealed that phosphorylation of RyR2 Ser2814 was significantly increased in the KI hearts and was further enhanced by ISO stimulation. Mechanistically, the combination of enhanced adrenergic activity and the loss of local PP2A activity from RyR2, which was likely associated with reduced AnkB/B56α binding, is a potential cause of RyR2 hyperphosphorylation.

Materials and Methods

The data and analytical methods have been made available to other researchers for the purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. Please refer to the expanded materials and methods in the online-only Data Supplement for details.

Human studies

Human studies were performed in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital to Nanchang University. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Animal studies

Animal studies were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996) and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Nanchang University.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. For data with a Gaussian distribution, unpaired Student’s t-tests (equal variance), or unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (unequal variance) were used for comparisons between two independent groups; and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey’s tests was used for multiple comparisons. For data with a non-Gaussian distribution, we performed a nonparametric statistical analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons between two groups or the Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple comparisons. Categorical data are expressed as percentages and compared between groups using the Fisher’s exact test. All analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Identification of a rare human ANK2 variant associated with VT

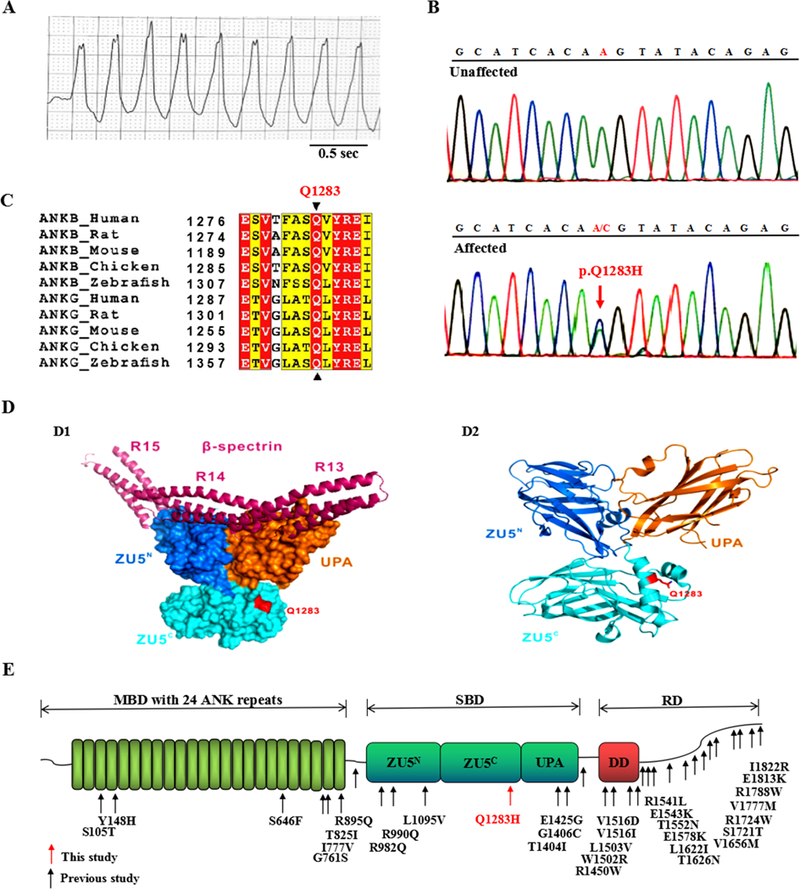

We performed whole exome sequencing in 25 unrelated Han Chinese probands with VT and identified an ANK2 variant in one 53-year-old female proband. This case had a history of recurrent palpitations and syncope due to VT (Fig. 1A). Her resting electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm, atrioventricular conduction and QT duration. VT episodes were abated upon treatment with a β-blocker (metoprolol). One month after termination of the drug, she re-experienced multiple syncopal episodes due to repeated VT. She subsequently underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation targeting the VT. The patient had no history of other diseases, familial cardiac events or SCD. Echocardiography examination did not detect any structural heart diseases.

Figure 1. Detection of the ANK2 p.Q1283H variant in a proband with VT.

(A) Electrocardiogram of the proband showing VT with a normal QTc interval of 430 ms. (B) Electropherogram showing the WT ANK2 sequence (upper panel) and the ANK2 p.Q1283H variant (lower panel, denoted by red arrow). This variant represents a heterozygous A-to-C nucleotide substitution (c.A3849C) in exon 33, resulting in a glutamine-to-histidine substitution at position 1283 (p.Q1283H). The c.A3849C and p.Q1283H variants described in this study are equivalent to the c.A3948C and p.Q1316H variants based on NM_020977.4 and NP_066187.2, respectively. (C) Protein sequence alignment revealing that the p.Q1283 residue of ANK2 is absolutely conserved across multiple species and isoforms. In this alignment, residues that are absolutely conserved and highly conserved are highlighted in red and yellow, respectively. (D) Structural model showing that the p.Q1283 residue was localized to the ZU5C domain outside of the spectrin-binding surface (D1). The ribbon structure of the crystal structure of AnkB ZZUD showing the location of the Q1283 residue (D2). The p.Q1283 residue is shown in red. (E) Mapping of the AnkB domain with ANK2 variants identified in previous studies (denoted by black arrows) and this study (denoted by red arrow). Canonical AnkB consists of distinct structural domains: an MBD with 24 ankyrin repeats, an SBD containing two ZU5 domains (ZU5N and ZU5C), a UPA domain, and an RD composed of a DD and a CTD. VT = ventricular tachycardia, QTc = corrected QT, WT = wild type, MBD = membrane-binding domain, SBD = spectrin-binding domain, RD = regulatory domain, DD = death domain, CTD = C-terminal domain, ZZUD = ZU5N-ZU5C-UPA-DD domains, sec = seconds.

Analysis of exome-sequencing data led to identification of 3 heterozygous variants, namely, p.T493I in CAMK2D, p.V2189I in AKAP9 and p.Q1283H in ANK2 (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). The CAMK2D p.T493I and AKAP9 p.V2189I variants showed a low pathogenicity potential based on in silico prediction algorithms (Supplemental Table 2). The ANK2 p.Q1283H (rs755373114) variant showed a high pathogenicity index and was further validated by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1B). This variant showed a rare minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.0008091 (East Asian) in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database. It was absent in 3,200 ethnically matched controls and in the “1000 Genomes” and “ESP6500” databases. The Q1283 residue of ANK2 is absolutely conserved across species and isoforms (Fig. 1C). The crystal structure of AnkB-SBD revealed that the p.Q1283H variant was localized to the surface of the ZU5C domain (Fig. 1D), where no variants have previously been linked with heart diseases (Fig. 1E). Family members of the proband with the p.Q1283H variant declined genetic studies.

To test the impact of the p.Q1283H variant on the AnkB polypeptide, we performed a biochemical analysis of purified AnkB-SBD harboring the p.Q1283H variant in parallel with the wild type (WT) and identified similar expression between them (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Analytical gel filtration assays using the WT and p.Q1283H mutant proteins with spectrin revealed an identical profile (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments further confirmed that the dissociation constants between the WT and mutant AnkB proteins with spectrin were similar (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Thus, we identified a rare ANK2 variant localized to the ZU5C region in a patient with VT, which did not affect the expression or the spectrin-binding properties of AnkB.

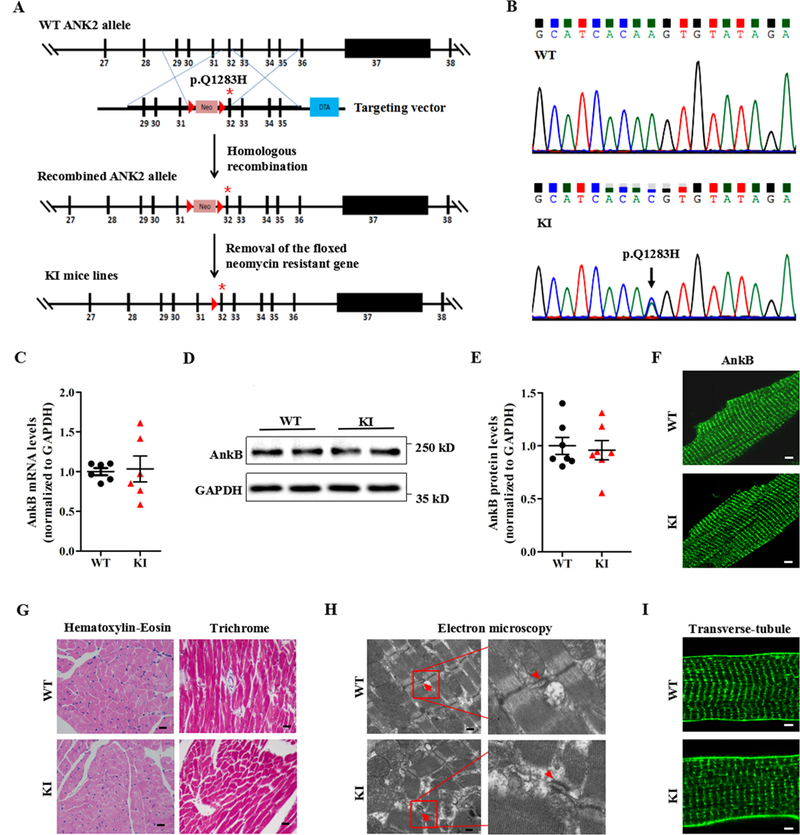

KI mice with the p.Q1283H variant exhibit cardiac arrhythmias in response to catecholamines

To characterize in vivo effects of the p.Q1283H variant on cardiac function, we engineered a KI mouse model harboring this variant through homologous recombination (Fig. 2A-B and Supplemental Table 3). In agreement with our biochemical data, the transcriptional and post-translational expression levels, as well as the localization of AnkB were indistinguishable between the WT and KI mice (Fig. 2C-F). Compared with age- and sex-matched WT littermates, the KI mice displayed no alterations in cardiac structure as assessed by echocardiography (Supplemental Table 4) and histopathological analysis (Fig. 2G), or in tissue ultrastructural organization, as assessed by electron microscopy (Fig. 2H). We also observed no differences in myocyte ultrastructure, including the t-tubule/SR complex (Fig. 2H-I), the intercalated disc protein (N-cadherin), and the microfilament and microtubule networks (Supplemental Fig. 3A).

Figure 2. Generation and evaluation of KI mouse models carrying the ANK2 p.Q1283H variant under basal conditions.

(A) Schematic diagram illustrating the targeting vector and step-wise generation of KI mouse models. (B) DNA sequencing confirming the successful generation of KI mice carrying the p.Q1283H variant (lower panel, denoted by black arrow). (C) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of AnkB mRNA in sections of the ventricles of WT and KI littermates (n = 6 hearts/genotype, P = 0.85). (D-E) Representative immunoblots (D) and quantitative assessment (E) of the protein expression level of AnkB in sections of the ventricles of WT and KI littermates (n = 7 hearts/genotype, P = 0.54). (F) Representative immunostaining showing that cardiomyocytes from WT and KI mice display a normal subcellular distribution of AnkB. (G) Representative images of hematoxylin-eosin staining (left; magnification ×400) and Masson’s trichrome staining (right; magnification ×400) of left ventricles from WT and KI mice. (H) Representative electron micrographs of left ventricles from WT and KI mice (red arrowheads indicate the t-tubule lumen marked by the sarcoplasmic reticulum and t-tubule membranes of the triads). (I) Representative immunostaining showing that cardiomyocytes from WT and KI mice display a normal t-tubule organization (stained with Di-8-ANEPPs). The data shown in F-I are representative of at least 3 hearts/genotype. WT = wild type, KI = knock-in, AnkB = ankyrin-B, GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-phosphate dehydrogenase, PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

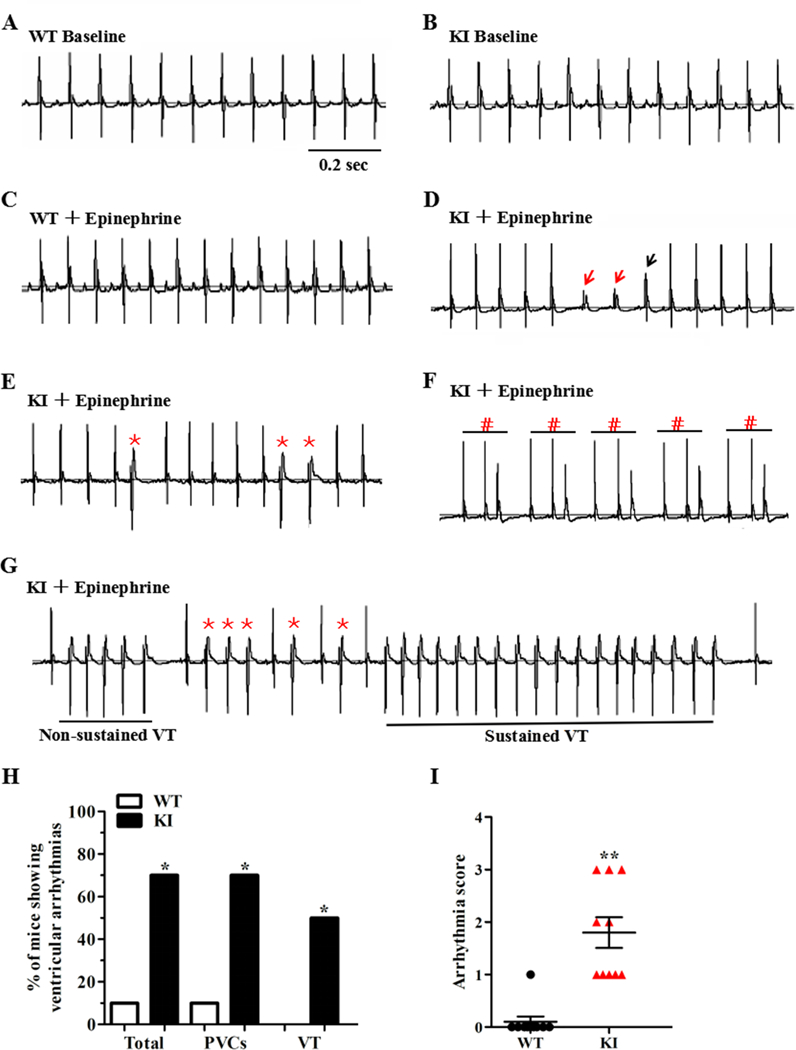

Telemetry monitoring of the cardiac rhythm in conscious animals revealed no differences in the electrocardiographic parameters between the two genotypes under sedentary conditions (Fig. 3A-B and Supplemental Table 5). Because both humans with ANK2 variants and AnkB+/− mice develop exercise- and/or catecholamine-induced ventricular arrhythmias and SCD,1, 3, 11 the KI mice were subjected to a catecholamine stress protocol (an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg epinephrine). Over a 60-min continuous recording, KI mice were more susceptible to developing a sinus pause and multiple ventricular arrhythmic patterns including premature ventricular contractions, bigeminy/trigeminy, and non-sustained or sustained VT episodes (Fig. 3C-G). Specifically, 7 of the 10 KI mice had an increased incidence of ventricular arrhythmias, whereas only 1 of the 10 WT mice showed an arrhythmia phenotype (70% in KI versus 10% in WT; P < 0.05; Fig. 3H). No WT mice presented a VT phenotype, but 50% of the KI mice did present a VT phenotype (50% in KI versus 0% in WT; P < 0.05). None of the VT rhythms deteriorated to ventricular fibrillation or death during the epinephrine challenge. In addition, compared with controls, the KI mice showed a remarkable increase in the arrhythmia score (P < 0.01; Fig. 3I).12

Figure 3. KI mice develop cardiac arrhythmias in response to stress stimulation.

(A-B) Representative lead-II ECG traces of conscious WT and KI mice at baseline, respectively. (C) Representative lead-II ECG traces of conscious WT mice after an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg epinephrine. (D-G) Representative lead-II ECG traces of conscious KI mice after an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg epinephrine. KI mice display a sinus pause (D, the escape rhythm is denoted by red arrows; the ventricular fusion beat is denoted by black arrow) and ventricular arrhythmias, including PVCs (E, *), trigeminy (F, #), and VT (G, both non-sustained and sustained episodes). (H) Cumulative incidence of ventricular arrhythmias of WT and KI mice under stress conditions (*P<0.05; n = 10 for WT and KI mice, respectively). (I) Cumulative data of the arrhythmia scores of WT and KI mice under stress conditions (**P<0.01; n = 10 for WT and KI mice). ECG = electrocardiogram, PVCs = premature ventricular contractions, VT = ventricular tachycardia, WT = wild type, KI = knock-in, sec = seconds.

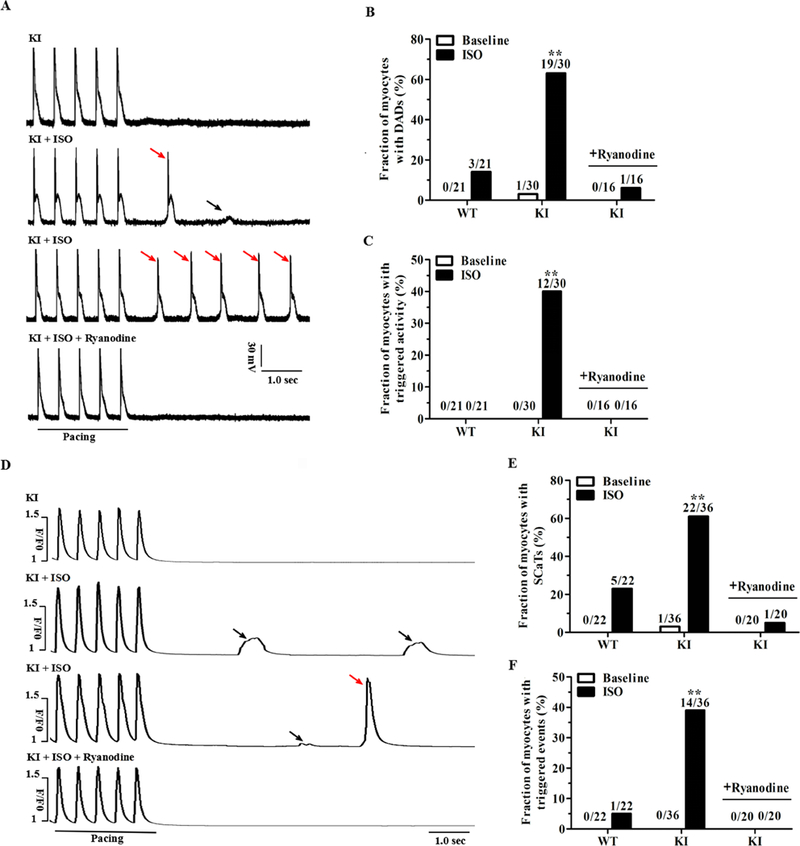

KI cardiomyocytes display delayed afterdepolarizations and spontaneous Ca2+ release under β-adrenergic stimulation

To determine the effect of the p.Q1283H variant on myocyte electrophysiological properties, we recorded the action potentials (Aps) of the WT and KI cardiomyocytes in the absence or presence of 1 μM ISO. After 10 seconds of pacing in order to reach steady-state Ca2+ transient amplitude, the field-stimulation was stopped and afterdepolarizations were recorded. In the absence of ISO, spontaneous afterdepolarizations were nearly absent in both groups. In the presence of ISO plus 2-Hz pacing, 14% (3/21) of the WT cardiomyocytes showed spontaneous DADs, whereas this incidence was increased to 63% (19/30) in the KI cardiomyocytes (P<0.01; Fig. 4A-B). Moreover, no WT cardiomyocytes showed trigger activity, but 40% (12/30) of the KI cardiomyocytes did show trigger activity (P<0.01; Fig. 4C). Under this condition, we observed no differences in the AP duration, AP amplitude, resting membrane potential, or rate of rise of the AP upstroke between the two groups (Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 4. KI cardiomyocytes display stress-induced delayed afterdepolarizations and spontaneous Ca2+ release.

(A) Representative traces of action potentials in KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO and/or 100 nM ryanodine. Small DADs (denoted by black arrow) and triggered activity (denoted by red arrows) were recorded following a stimulation pause after a 2-Hz field stimulation. (B-C) Cumulative incidence of DADs (B) and triggered activity (C) in WT and KI cardiomyocytes (n = 16 to 30 cells per group from 5 hearts/genotype, **P < 0.01 versus WT + ISO or versus KI + ISO + ryanodine). (D) Representative traces of the occurrence of SCaTs (denoted by black arrows) and triggered beats (denoted by red arrow) following a stimulation pause after 2-Hz field stimulation in KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO and/or 100 nM ryanodine. (E-F) Cumulative incidence of SCaTs (E) and triggered beats (F) in WT and KI cardiomyocytes (n = 20 to 36 cells per group from 5 hearts/genotype, **P < 0.01 versus WT + ISO or versus KI + ISO + ryanodine). WT = wild type, KI = knock-in, SR = sarcoplasmic reticulum, DADs = delayed afterdepolarizations, SCaTs = spontaneous Ca2+ transients, ISO = isoproterenol, sec = seconds.

Diastolic spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR is a potential electrophysiological basis for the formation of DAD-mediated trigger activity.13 To evaluate the status of SR Ca2+ release, we examined the occurrence of spontaneous Ca2+ transients (SCaTs, i.e., Ca2+ waves) in fluo-4-loaded cardiomyocytes. During pausing following a period of pacing, SCaTs were rarely observed in the two groups in the absence of ISO. However, in the presence of ISO plus 2-Hz pacing, 61% (22/36) of the KI cardiomyocytes developed SCaTs compared with 23% (5/22) of the WT cardiomyocytes (P<0.01; Fig. 4D-E). Moreover, only 5% (1/22) of the WT cells developed triggered events; however, this incidence was increased to 39% (14/36) in the KI cells (P<0.01; Fig. 4F). To test whether spontaneous SR Ca2+ release potentially underlies the chaotic electrical behavior, the KI cardiomyocytes were pretreated with ryanodine, an agent with a high affinity for RyR2. As shown in Fig. 4A-F, 100 nM ryanodine significantly inhibited the Ca2+ waves, and subsequently, the DADs and trigger activity in the KI cardiomyocytes under ISO stimulation.

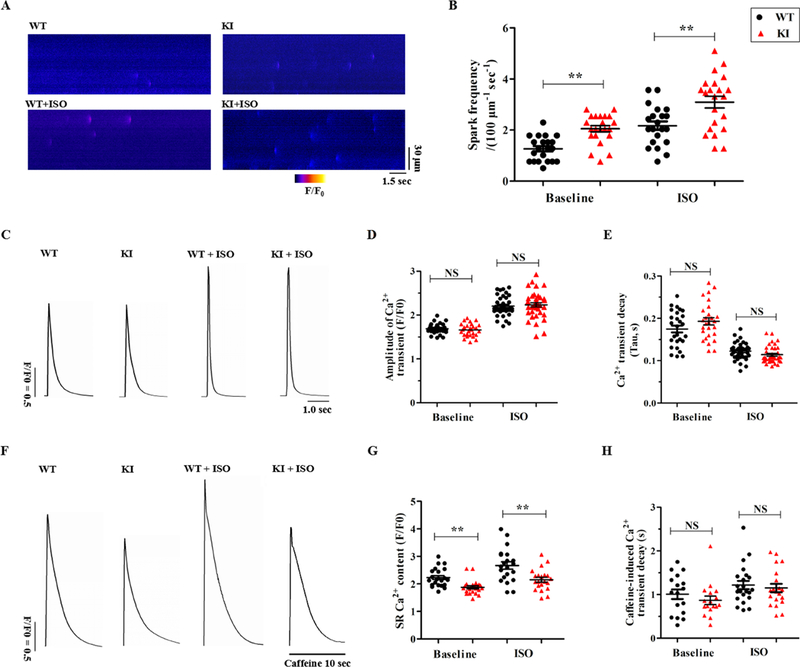

KI cardiomyocytes display an enhanced Ca2+ spark frequency and a reduced SR Ca2+ content

Because spontaneous SR Ca2+ release primarily manifests as abnormal RyR2 openings,14 we visualized Ca2+ sparks in quiescent fluo-4-loaded cardiomyocytes. As presented in Fig. 5A-B, the frequency of Ca2+ sparks was significantly increased in the KI cardiomyocytes without ISO stimulation (2.05 ± 0.12 in KI versus 1.27 ± 0.10 sparks/100 μm−1 s−1 in WT; P<0.01). In the presence of ISO, the Ca2+ spark frequency was further enhanced (3.09 ± 0.23 in KI versus 2.17 ± 0.17 sparks/100 μm−1 s−1 in WT; P<0.01). In addition, other Ca2+ spark characteristics were unchanged in the KI cardiomyocytes (Supplemental Table 7).

Figure 5. KI cardiomyocytes display an increased Ca2+ spark frequency and reduced SR Ca2+ content.

(A) Representative line-scan images of Ca2+ sparks in WT and KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO. (B) Cumulative data of the Ca2+ spark frequency in WT and KI cardiomyocytes (n = 21 to 22 cells per group from 5 hearts/genotype, **P < 0.01). (C) Representative traces of field-stimulated Ca2+ transients in WT and KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO. (D-E) Cumulative data of the amplitude of field-stimulated Ca2+ transients (D, P = NS) and decay-time constants (E, P = NS) in WT and KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO (n = 27 to 37 cells per group from 5 hearts/genotype). (F) Representative traces of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients in WT and KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO. (G-H) Cumulative data of the amplitude of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients (i.e., SR Ca2+ content, G, **P < 0.01) and decay-time constants (H, P = NS) in WT and KI cardiomyocytes ± ISO (n=17 to 22 cells per group from 5 hearts/genotype). WT = wild type, KI = knock-in, ISO = isoproterenol, SR = sarcoplasmic reticulum, NS = not significant, sec = seconds.

To determine whether aberrant Ca2+ sparks affect the cardiac systolic process, we compared the Ca2+ handling characteristics between the WT and KI cardiomyocytes. As shown in Fig. 5C-E, the amplitudes of field-stimulated Ca2+ transients and the average decay-time constants were similar between the two groups with or without ISO stimulation. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients were assessed by the rapid application of 10 mM caffeine following the cessation of pacing. Judging from the amplitude of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients, compared with their WT counterparts, the KI cardiomyocytes showed a significantly decreased SR Ca2+ content in both the absence and presence of ISO (Fig. 5F-G). However, the Ca2+ decay-time constant during the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients, which reflects the activity of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type 1 (NCX1),15 showed no difference between the two groups (Fig. 5H).

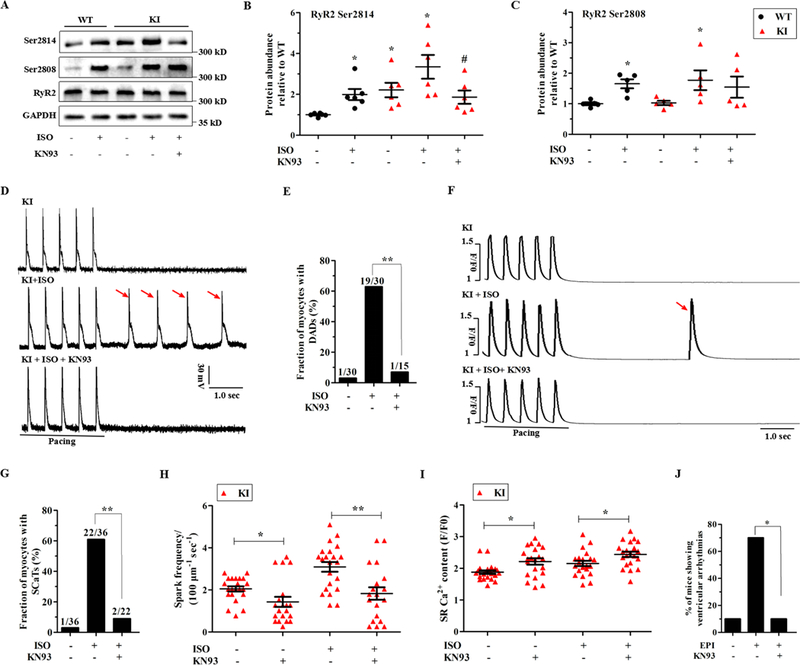

Enhanced phosphorylation of RyR2 contributes to spontaneous Ca2+ release in KI cardiomyocytes

Despite the changes in electrical activity observed in the KI cardiomyocytes, we observed no differences in the protein level of Kv7.1, Nav1.5 or connexin-43 between the experimental groups (Supplemental Fig. 4). To further investigate the molecular mechanisms of abnormal intracellular Ca2+ cycling, we performed immunoblotting and imaging analyses to determine possible changes in t-tubule/SR membrane-associated Ca2+-cycling regulatory proteins. However, we did not observe any alterations in the expression or subcellular distribution of sarcolemmal proteins, including NCX1, Na+/K+ ATPase α1/α2 and the L-type calcium channel (Cav1.2), or in SR membrane proteins, including RyR2, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R), SR Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase 2 (SERCA2), phospholamban (PLN), and calsequestrin 2 (Supplemental Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. 5).

The post-translational modification of Ca2+-cycling proteins is tightly regulated by adrenergic signaling pathways, which is a potent mechanism for modulating functional SR Ca2+ release.16 Therefore, we tested the phosphorylation status of RyR2, Cav1.2, and PLN at both the cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) sites. Consequently, the phosphorylation status of Cav1.2 and PLN showed no changes in the KI hearts (Supplemental Fig. 5). However, the data presented in Fig. 6A-C demonstrated that the phosphorylation of RyR2 at the CaMKII site (Ser2814) was significantly increased in the KI myocardium under basal conditions and further enhanced in the presence of ISO, whereas its phosphorylation at the PKA site (Ser2808) was comparable between the experimental groups.

Figure 6. CaMKII dependent phosphorylation of RyR2 and functional effects of CaMKII inhibition in KI hearts.

(A-C) Representative immunoblots (A) and quantitative assessment of the protein and phosphorylation levels of RyR2 at Ser2814 (B; *P < 0.05 versus WT at baseline, #P < 0.05 versus KI + ISO; n = 6 hearts/genotype) and Ser2808 (C; *P < 0.05 versus WT at baseline; n = 5 hearts/genotype) from left ventricle sections in littermates of WT and KI perfused hearts ± 1 μM ISO and/or 1 μM KN93. (D-E) Representative traces of the action potentials (D) and cumulative incidence of DADs (E; **P < 0.01) following a stimulation pause after a 2-Hz field stimulation in KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO and/or 1 μM KN93. (F-G) Representative traces of SCaTs (F) and the cumulative incidence of SCaTs (G; **P < 0.01) following a stimulation pause after a 2-Hz field stimulation in KI cardiomyocytes ± 1 μM ISO and/or 1 μM KN93. (H) Cumulative data of Ca2+ spark frequency in KI cardiomyocytes ± ISO (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (I) Cumulative data of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient amplitude (i.e., SR Ca2+ content) in KI cardiomyocytes ± ISO (*P < 0.05). (J) Cumulative incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in KN93-pretreated KI mice after an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg epinephrine (*P < 0.05; n = 10 KI mice for each group). CaMKII = calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, RyR2 = ryanodine receptor type 2, GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-phosphate dehydrogenase, WT = wild type, KI = knock-in, DADs = delayed afterdepolarizations, SCaTs = spontaneous Ca2+ transients, ISO = isoproterenol, sec = seconds.

To further test whether an increased level of RyR2 Ser2814 was responsible for the functional changes, a potent CaMKII inhibitor, KN93 (1 μM),17 was applied to the KI hearts in the absence or presence of ISO. As expected, KN93 significantly blunted the ISO-induced increase in RyR2 Ser2814 and had no effect on Ser2808 (Fig. 6A-C). The functional consequences of this effect on RyR2 were that KN93 significantly reversed the DADs and the Ca2+ waves that were induced by ISO as well as the Ca2+ spark frequency and the SR Ca2+ content under basal and stress conditions (Fig. 6D-I). As with KN-93, 1 μM AIP II,18 a highly selective peptide inhibitor, also alleviated these functional consequences (Supplemental Fig. 6). Importantly, after an intraperitoneal injection of 30 μmol/kg KN93, only 1 of the 10 KI mice suffered from ventricular arrhythmias during epinephrine challenge (P<0.05 versus no drug; Fig. 6J).

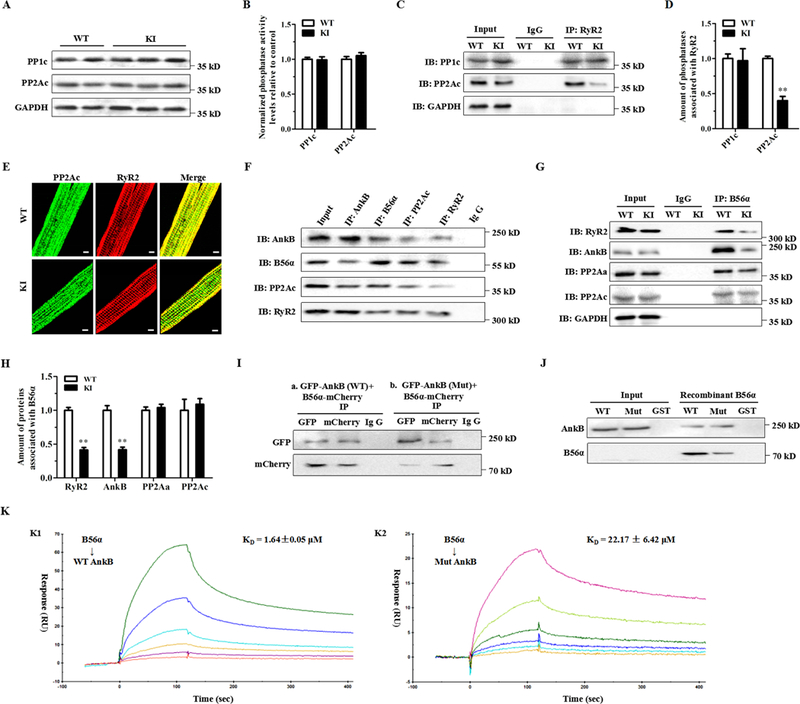

Enhanced phosphorylation of RyR2 is likely determined by the loss of local phosphatase activity in KI cardiomyocytes

The RyR2 complex is bound to kinases and phosphatases that modulate RyR2 in a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation dynamic balance.16, 19 Either an increase in kinase activity or a decrease in phosphatase activity may be responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of RyR2. The immunoblotting analysis did not show any changes in the expression of the PKA catalytic subunit or in CaMKII and its phosphorylation and oxidation (Supplemental Fig. 7A-B). In addition, we did not observe any changes in the phosphorylation status of other PKA (Cav1.2-Ser1928 and PLN-Ser16) or CaMKII (Cav1.2-Ser1512 and PLN-Thr17) targets. Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed no changes in the abundance of CaMKII that was physically associated with RyR2 in the KI hearts (Supplemental Fig. 7C). These findings reduce the possibility that the enhanced phosphorylation of RyR2 is caused by increased kinase activity.

Protein phosphatase type 1 (PP1) and PP2A are responsible for more than 90% of dephosphorylation events.7 However, our immunoblotting analysis found no differences in the expression of the catalytic subunits of PP1 (PP1c) and PP2A (PP2Ac) between the WT and KI hearts (Fig. 7A). Phosphatase activity assays showed no differences in the total activity of PP1 and PP2A in samples from both heart homogenates (Fig. 7B). However, co-immunoprecipitation assays showed a significantly reduced amount of PP2Ac associated with RyR2, but the interaction of PP1c with RyR2 was not affected in the KI hearts (Fig. 7C-D). Consistently, confocal images showed decreased co-localization of PP2Ac and RyR2 in the KI cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7E). We provide evidence that at least in part, RyR2 hyperphosphorylation is due to a decrease in the targeting of PP2Ac to RyR2.

Figure 7. The p.Q1283H variant affects the integration of RyR2 with PP2Ac likely due to decreased AnkB binding of B56α.

(A) Representative immunoblots of the expression levels of relevant phosphatases (PP1c and PP2Ac) from left ventricle sections in littermates of WT and KI mice. (B) Protein phosphatase assays using a fluorescence-based kit for measuring the total PP1 and PP2A activities in heart homogenates from WT and KI mice. (C-D) Representative immunoblots (C) and quantitative assessment (D) of PP1c and PP2Ac co-immunoprecipitated with RyR2 showing a reduced amount of PP2Ac associated with RyR2 (**P < 0.01), but the interaction of PP1c with RyR2 was not affected in KI hearts. (E) Representative immunofluorescence assays of WT (upper panel) and KI (lower panel) cardiomyocytes coimmunolabeled with PP2Ac (left, green) and RyR2 (middle, red) specific antibodies. (F) Representative co-immunoprecipitation assays showing a macromolecular complex composed of AnkB, B56α, PP2Ac and RyR2. Total protein homogenates from mouse left ventricles were immunoblotted with either an anti-RyR2 antibody or with antibodies that recognize AnkB, B56α, and PP2Ac, all of which were detected in immunoprecipitates, whereas control preimmune serum (IgG) did not immunoprecipitate the proteins. (G-H) Representative co-immunoprecipitation assays (G) and quantitative assessment (H) using the anti-B56α antibody as bait showing decreased binding of RyR2 (**P < 0.01) or AnkB (**P < 0.01) with B56α, but the abundance of PP2Aα or PP2Ac binding with B56α was unchanged in KI hearts. (I) Co-immunoprecipitation from HEK-293 cells expressing GFP-tagged mutant AnkB and mCherry-tagged B56α showing a reduced binding of AnkB to B56α. (J) Representative GST pull-down assays showing that GST-labeled WT AnkB pulled down recombinant B56α, but GST-labeled mutant AnkB showed a decreased binding to B56α. (K) BIAcore binding properties of WT (K1: KD = 1.64 ± 0.05 μM) or mutant (K2: KD = 22.17 ± 6.42 μM) AnkB purified proteins to B56α. PP1c = PP1 catalytic subunit, PP2Aα = PP2A scaffolding subunit, PP2Ac = PP2A catalytic subunit, RyR2 = ryanodine receptor type 2, AnkB = ankyrin-B, GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-phosphate dehydrogenase, WT = wild type, KI = knock-in, ISO = isoproterenol, HEK = human embryonic kidney, RU = response units, AnkB = ankyrin-B, IB = immunoblots, IP = immunoprecipitation, sec = seconds.

Local PP2A activity appears to be controlled by reversible post-translational modifications of PP2Ac, including tyrosine phosphorylation (Tyr-307) and leucine methylation (Leu-309),20 or is linked to the PP2A regulatory subunits,21 including B56α,10 B56δ,22, 23 and PR13024 that tether the PP2A holoenzyme to RyR2. However, we found no differences in their expression levels between KI versus WT hearts (Supplemental Fig. 8). Since B56α has been demonstrated to interact with AnkB,10 we hypothesized that a decrease in PP2A activity localized to RyR2 would reflect the central role of AnkB in targeting B56α. For this purpose, our co-immunoprecipitation experiments on mouse heart homogenates showed that the RyR2 macromolecular complex encompassed B56α, PP2Ac, the PP2A scaffolding subunit (PP2Aα) and AnkB (Fig. 7F). Notably, immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated a significantly decreased binding of AnkB or RyR2 with B56α, but the abundance of PP2Aα or PP2Ac binding with B56α was unchanged in the KI hearts (Fig. 7G-H). Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation experiments on the lysates of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells expressing GFP-tagged mutant AnkB and mCherry-tagged B56α demonstrated a reduced binding of AnkB to B56α (Fig. 7I). GST-labeled WT AnkB could pull down the recombinant B56α protein, but GST-labeled mutant AnkB decreased its binding to B56α (Fig. 7J). Further surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments revealed that the purified recombinant AnkB could bind to B56α, while the mutant AnkB proteins led to a reduced binding affinity with B56α (Fig. 7K).

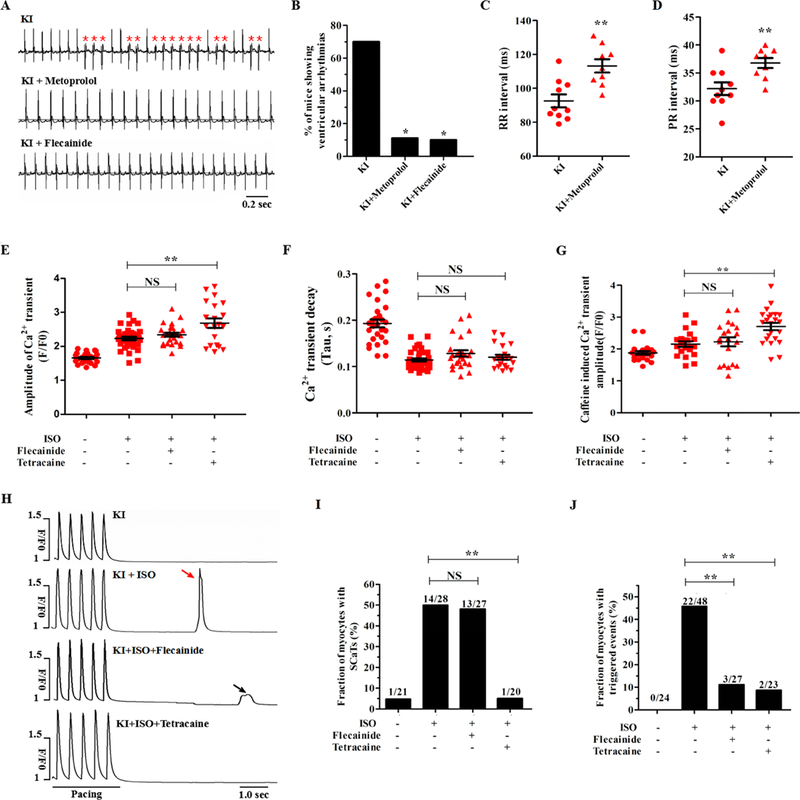

Effect of drug therapy on the stress-induced arrhythmia burden in KI mice

To evaluate the anti-arrhythmic potential of β-blocker therapy during epinephrine challenge, the KI mice were pretreated with 100 mg/kg/day metoprolol for 3 weeks. In contrast to untreated KI mice, only 1 of 9 metoprolol-pretreated animals suffered from stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias (P<0.05; Fig. 8A-B). The expected changes of prolonged RR and PR intervals typically resulting from metoprolol therapy were observed (Fig. 8C-D and Supplemental Table 5). However, the effect of metoprolol on these parameters was similar between the WT and KI mice (Supplemental Fig. 9). M-mode echocardiogram tracings indicated no alterations in the contractile or structural parameters of the KI mice pretreated with metoprolol (Supplemental Table 4). In the KI cardiomyocytes, ISO stimulation increased the amplitude and decay of field-stimulated Ca2+ transients, but metoprolol counteracted these β-adrenergic effects (Supplemental Fig. 10).

Figure 8. Effect of drug therapy on the stress-induced arrhythmia burden in KI mice.

(A) Electrocardiogram recordings of KI mice pretreated with metoprolol or flecainide after an intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg epinephrine (PVCs were denoted by red asterisks). (B) Cumulative incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in KI mice after administration of metoprolol (*P < 0.05 versus no drug) or flecainide (*P < 0.05 versus no drug). (C-D) Cumulative data of RR (C, **P < 0.01 versus no drug) and PR (D, **P < 0.01 versus no drug) intervals in metoprolol-pretreated KI mice. (E-G) Cumulative data of the field-stimulated Ca2+ transient amplitude (E, n = 20 to 37 cells per group, P = NS for KI + ISO + flecainide versus KI + ISO, **P < 0.01 for KI + ISO + tetracaine versus KI + ISO), field-stimulated Ca2+ transient decay-time constants (F, n = 20 to 37 cells per group, P = NS) and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient amplitude (G, n = 20 to 23 cells per group, P = NS for KI + ISO + flecainide versus KI + ISO, **P < 0.01 for KI + ISO + tetracaine versus KI + ISO) of KI cardiomyocytes. (H-J) Representative images (H) and cumulative data showing that tetracaine, but not flecainide, decreased the incidence of ISO-induced SCaTs (I, n = 20 to 28 cells per group, P = NS for KI + ISO + flecainide versus KI + ISO, **P < 0.01 for KI + ISO + tetracaine versus KI + ISO) and that both tetracaine and flecainide decreased the incidence of ISO-induced triggered beats (J, n = 23 to 48 cells per group, **P < 0.01) in KI cardiomyocytes. PVCs = premature ventricular contractions, SCaTs = spontaneous Ca2+ transients, KI = knock-in, ISO = isoproterenol, NS = not significant, sec = seconds.

Flecainide (a class IC antiarrhythmic drug) has been increasingly accepted to be an effective agent for suppressing CPVT in mouse models25 and clinical patients.26 The underlying mechanism of action of flecainide is linked, although not exclusively, to the suppression of SR Ca2+ release through RyR2.27 We assessed the therapeutic role of flecainide (15 mg/kg) in the KI mice during epinephrine challenge. As a result, only 1 of 10 KI mice pretreated with flecainide displayed ventricular arrhythmias (P<0.05 versus no drug; Fig. 8A-B). In the KI cardiomyocytes with ISO stimulation, 50 μM tetracaine (incubation for 3 minutes) increased the Ca2+ transient amplitude and SR Ca2+ content, but 6 μM flecainide (incubation for 30 minutes) had no effects on these parameters (Fig. 8E-G). Accordingly, flecainide had no effect on the incidence of SCaTs elicited by ISO, whereas tetracaine reduced this incidence from 50% to 5% (Fig. 8H-I). In contrast, both tetracaine and flecainide decreased the incidence of triggered events (Fig. 8J). These data suggest that flecainide may prevent stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias in KI mice, but not directly through RyR2 inhibition.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified a rare p.Q1283H variant in the ZU5C region of ANK2, which is associated with VT. The p.Q1283H is a “disease-linked” variant as shown by multiple techniques, including a KI mouse model, cardiac electrophysiology, and cellular and molecular investigations. The KI mice bearing this variant displayed stress-induced arrhythmias, exhibiting some resemblance to the human p.Q1283H carrier’s phenotype. Spontaneous SR Ca2+ release caused by RyR2 hyperphosphorylation is a contributing factor of the increased frequency of DADs and trigger activity. Mechanistically, the dissociation of PP2A from RyR2, characterized by a highly phosphorylated state of RyR2, is likely attributable to the reduced binding of AnkB to B56α. Finally, the administration of metoprolol or flecainide appears to be effective for managing p.Q1283H-induced arrhythmias.

Nearly all previously reported, likely deleterious ANK2 variants are located in the SBD or RD domains.4 In contrast, the p.Q1283H is the first variant identified in the ZU5C region. The minor allele frequency, in silico analyses and in vitro functional assays are commonly used to characterize the function and mechanistic rationale of ANK2 variants. More importantly, the introduction of a mutant AnkB construct into cardiomyocytes from AnkB+/− mice is unable to restore its abnormal functional activity, indirectly supporting a “disease-associated” variant.1–3 Nevertheless, compared with AnkB+/− mice with a large genetic intervention, KI mice bearing a specific ANK2 variant can be more valuable tools for directly characterizing its disease risk.28 Although KI mice homozygous for ANK2 p.L1622I produce cardiac electrical phenotypes,11 they cannot completely reproduce the human phenotype because heterozygous p.L1622I is more common in clinical settings. In contrast, we used heterozygous KI mice to mimic the heterozygous state of the human p.Q1283H carrier, and the mice displayed similarities to the arrhythmia phenotype of the patient.

Although similar phenotypes may result from different variants, the molecular mechanism underlying each variant can be distinct. ANK2 variants may interfere with normal AnkB function by modulating intramolecular interactions.29 For example, RD interacts with the amino-terminus of the MBD to modulate its protein association with Ca2+ channels and transporters, and these associations can be impaired by ANK2 variants in the RD.4 On the other hand, ANK2 variants participate in modulating its interactions with its targeting proteins.30 For example, the p.R1788W variant in the CTD directly abolishes AnkB binding to human DnaJ homologue 1.31 The p.R990Q variant in ZU5N leads to a severe arrhythmia phenotype by interfering with its binding to βII-spectrin.32 However, our p.Q1283H variant located in the ZU5C region did not affect its interaction with βII spectrin. In line with our findings, a number of synthetic ANK2 variants in the ZU5C region do not affect the βII-spectrin binding but still impair the function of AnkB.33 Of note, nearly all reported ANK2 variants result in a reduced abundance of AnkB, leading to altered intracellular Ca2+ dynamics linked with the abnormal expression and localization of NCX1, Na+/K+ ATPase α1/α2 and IP3R.4 Notably, the p.Q1283H variant did not alter the expression or subcellular distribution of AnkB. Therefore, beyond disturbed AnkB/βII spectrin binding or functional AnkB haploinsufficiency, previously unrecognized pathophysiological mechanisms that contribute to the processes of arrhythmias may exist.

In our study, patch-clamped KI myocytes showed an increased incidence of DAD-related trigger activity during ISO challenge. DADs are initiated by inward-mode NCX activation in response to spontaneous increases in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, which generates a transient depolarizing current.34 If DADs reach the threshold for sarcolemmal Na+ channels, an AP may be triggered and propagated through the myocardium, ultimately precipitating arrhythmias. It is thought that diastolic SR Ca2+ release via hyperactive RyR2 is the primary molecular basis for Ca2+-dependent DADs.13 Indeed, KI cardiomyocytes demonstrated an arrhythmogenic increase in spontaneous Ca2+ waves and SR Ca2+ leak, particularly following ISO challenge. Ryanodine rescued these components of abnormal Ca2+ signaling, demonstrating that abnormally high RyR2 activity potentially underlies dysfunctional Ca2+ regulation. In parallel with the upregulation of RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak, the SR Ca2+ content was decreased in KI cardiomyocytes. Upregulated RyR2-mediated SR Ca2+ leak is an underlying cause of a reduced SR Ca2+ content,35, 36 resulting in proarrhythmic remodeling of Ca2+ homeostasis and arrhythmias.37

It is well known that, the phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814 plays a more important role in arrhythmogenic SR Ca2+ release than that of RyR2 at Ser2808.16 In our KI model, the phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814 was significantly increased under both basal and stress conditions. The inhibition of CaMKII by KN93 normalized this hyperphosphorylation and successfully antagonized the β-adrenergic effects and the triggering of ventricular arrhythmias.17 Thus, the dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ cycling due to RyR2 hyperphosphorylation potentially contributes to DAD-related trigger activity. Furthermore, the adaptive changes in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis were in agreement with the dynamic changes in the phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814. Under basal conditions, arrhythmias and arrhythmogenic SR Ca2+ release events did not occur despite the increased phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814, suggesting that RyR2 Ser2814 alone is not sufficient to generate arrhythmias. After adding ISO to KI myocytes, β-adrenoceptor activation led to further abnormally enhanced the phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814 and functional disturbance. In fact, the p.Q1283H variant promoted the phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2814 at baseline and led to a highly arrhythmogenic state under conditions of increased sympathetic drive.

Experimental data suggest that alterations in local phosphatase activity toward specific substrates may be more harmful than alterations in the total phosphatase activity in cardiomyocytes.19, 37, 38 Likewise, in our KI hearts, downregulated local PP2A holoenzyme populations may be an explanation for the RyR2 hyperphosphorylation. The additional targets of PP2A-Cav1.2 and PLN exhibited unchanged phosphorylation states, suggesting that PP2A-based RyR2 dephosphorylation is mutation specific in this KI model. Similar arrhythmic substrates in different murine models may result from distinct molecular mechanisms. In the AnkB+/− mouse model, RyR2 hyperphosphorylation associated with spontaneous SR Ca2+ release contributes to sympathetically mediated arrhythmias.6, 39, 40 This RyR2 hyperphosphorylation in AnkB+/− hearts is CaMKII dependent due to increased junctional Ca2+,39 whereas defects in the PP2A-based signaling pathway facilitate the phosphorylation of RyR2 in our KI model. It appears that there is no need for CaMKII to be overactive because limited activity without CaMKII activation is sufficient to phosphorylate RyR2 in the absence of phosphatases.9, 41, 42

Several groups have investigated the specific sites of RyR2 dephosphorylation that are controlled by phosphatases, but their findings have been controversial. Little et al.8 demonstrated that the upregulation of PP2A activity decreased RyR2 phosphorylation at both Ser2814 and Ser2808. However, our findings demonstrated that changes in the local PP2A activity only dephosphorylated RyR2 at Ser2814. Consistently, Huke and Bers43 have demonstrated that PP1 preferentially controls RyR2 phosphorylation at Ser2808, whereas RyR2 Ser2814 is under the specific control of PP2A. Muscle-specific microRNAs mediating the suppression of PP2A activity in the RyR2 microdomain appear to regulate the phosphorylation of Ser2814.9, 23 Notably, the recognition of specific sites by the PP2A family may involve the additive effects of multiple distinct interactions, which could be a topic of cardiovascular research in follow-up studies.

AnkB is essential for targeting B56α,10 which in turn tethers PP2A to the RyR2 complex.9 B56α overexpression in vivo does not alter the expression of AnkB,44 whereas primary cardiomyocytes from AnkB-deficient mice display an increased abundance and disorganized distribution of B56α.8, 10 In addition, AnkB localizes with IP3R in a compartment distinct from RyR2,45 suggesting that AnkB does not form a stable complex with RyR2 and thus does not directly modify RyR2 activity. We speculate that AnkB-mediated RyR2 hyperactivity is likely linked to the modulation of B56α. It remains a subject of debate whether the regulation of B56α mediates the activity of PP2A or RyR2.16 Although the short-term expression of B56α in vitro does not alter PP2Ac expression,46 the cardiac-specific overexpression of B56α in transgenic mice leads to a compensatory increase in PP2Ac expression and activity.44 On the other hand, the inhibition of B56α expression causes profound changes in PP2A activity, subsequently causing RyR2 dysfunction.8, 9 In our study, cardiac expression of mutant AnkB impaired the binding ability of the PP2A/B56α complex to RyR2 at specialized myocyte subdomains. We summarize that the AnkB-based abnormal spatial distribution of B56α leads to the dissociation of local PP2A from RyR2, subsequently resulting in RyR2 hyperphosphorylation.

The management of AnkB-based arrhythmias mainly depends on the defined clinical features of the patients. In our KI mice, metoprolol reduced the incidence of stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias. However, some patients with ANK2 variants, such as R1788W,2 S646F,47 and W1535R,48 are refractory to β-blocker therapy; therefore, more effective therapeutic options are required. In our KI mice, flecainide mitigated the risk of stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias. In isolated KI myocytes, flecainide had no effect on ISO-induced SCaTs, but it significantly inhibited triggered events, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of flecainide may be not due to its direct blocking of open-state RyR2.49 As previously reported, this inhibitory action is likely due to the inhibition of subsarcolemmal Na+ channels25 or the modification of the NCX activity.50 Finally, understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms of arrhythmias is helpful for developing possible precision therapies. AnkB may indirectly regulate the function of RyR2 by modulating the activity of PP2A, suggesting a novel therapeutic target for arrhythmias.

Several limitations should be considered in this study. First, because our experiments are confined to young adult animals, future studies should focus on older animals to determine whether they exhibit more severe phenotypes. Second, while mouse models provides insight into the mechanisms of human disease, inherent differences between human and mouse physiology must ultimately be considered when interpreting our findings. Thus, while our findings support the mechanisms underlying this human condition, we recognize that there may be pathophysiological differences. Finally, we mainly focused on the susceptibility of KI mice to arrhythmias under acute stress. However, whether an increased sympathetic input to the heart tunes Ca2+ homeostasis in chronic disease is still unknown.

In conclusion, we first identified a “disease-associated” p.Q1283H variant in ANK2-ZU5C that is responsible for arrhythmias, which may be treated with metoprolol or flecainide. We found that the dysregulation of intracellular Ca2+ cycling because of RyR2 hyperphosphorylation potentially contributes to DAD-related trigger activity. Additionally, the combination of enhanced adrenergic activity and the loss of PP2A activity from RyR2, which is likely associated with reduced AnkB/B56α binding, provides the underlying molecular mechanisms of the diastolic SR Ca2+ release. Our findings provide new insights into the functional role of AnkB, as well as the potential pathogenesis of and the therapeutic options for AnkB-based arrhythmias.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective

What is new?

We identified the first ANK2 variant (p.Q1283H) localized to the ZU5C region in a patient with ventricular tachycardia.

KI mice with the p.Q1283H variant showed an increased susceptibility to arrhythmias associated with abnormal Ca2+ dynamics.

The loss of PP2A activity from RyR2 is likely associated with reduced ankyrin-B/B56α binding, which is the potential mechanism of RyR2 hyperphosphorylation.

Metoprolol and flecainide are potential therapies for ANK2 p.Q1283H-associated arrhythmias.

What are the clinical implications?

Our study indicates the dysfunction of the ZU5C region might be responsible for arrhythmias.

Our findings on ANK2 variants interfering with the PP2A-related Ca2+ signaling pathway would help in the development of a possible antiarrhythmic medication.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to Dr. Jianghua Shao (Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China) for the SPR experiments, and Prof. AJ Marian (University of Texas Health Science Center, USA) for the language and manuscript preparation editing.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, 81530013), National key Research & Development Program of China (2017YFC1307804), National Institute of Health (NIH, HL135754, HL134824).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

Affiliations: From Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (W.G.Z., C.W., J.Z.H., R.W., J.H.Y., J.Y.X., J.Y.M., L.J.G., J.G., Y.M.Q., L.F.C., H.L.L., X.Y., X.X.L., W.F.H., Y.S., K.H.); University of Science and Technology of China (J.Y., C.W.); Ohio State University (P.J.M.)

References

- 1.Mohler PJ, Le Scouarnec S, Denjoy I, Lowe JS, Guicheney P, Caron L, Driskell IM, Schott JJ, Norris K, Leenhardt A, Kim RB, Escande D, Roden DM. Defining the cellular phenotype of “ankyrin-B syndrome” variants: human ANK2 variants associated with clinical phenotypes display a spectrum of activities in cardiomyocytes. CIRCULATION. 2007;115:432–441. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.656512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohler PJ, Splawski I, Napolitano C, Bottelli G, Sharpe L, Timothy K, Priori SG, Keating MT, Bennett V. A cardiac arrhythmia syndrome caused by loss of ankyrin-B function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9137–9142. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0402546101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohler PJ, Schott JJ, Gramolini AO, Dilly KW, Guatimosim S, DuBell WH, Song LS, Haurogne K, Kyndt F, Ali ME, Rogers TB, Lederer WJ, Escande D, Le Marec H, Bennett V. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. NATURE. 2003;421:634–639. DOI: 10.1038/nature01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koenig SN, Mohler PJ. The evolving role of ankyrin-B in cardiovascular disease. HEART RHYTHM. 2017;14:1884–1889. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Yu C, Ye F, Wei Z, Zhang M. Structure of the ZU5-ZU5-UPA-DD tandem of ankyrin-B reveals interaction surfaces necessary for ankyrin function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4822–4827. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1200613109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGrande S, Nixon D, Koval O, Curran JW, Wright P, Wang Q, Kashef F, Chiang D, Li N, Wehrens XHT, Anderson ME, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ. CaMKII inhibition rescues proarrhythmic phenotypes in the model of human ankyrin-B syndrome. HEART RHYTHM. 2012;9:2034–2041. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubbers ER, Mohler PJ. Roles and regulation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) in the heart. J MOL CELL CARDIOL. 2016;101:127–133. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little SC, Curran J, Makara MA, Kline CF, Ho HT, Xu Z, Wu X, Polina I, Musa H, Meadows AM, Carnes CA, Biesiadecki BJ, Davis JP, Weisleder N, Gyorke S, Wehrens XH, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ. Protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit B56alpha limits phosphatase activity in the heart. SCI SIGNAL. 2015;8:a72 DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terentyev D, Belevych AE, Terentyeva R, Martin MM, Malana GE, Kuhn DE, Abdellatif M, Feldman DS, Elton TS, Gyorke S. miR-1 overexpression enhances Ca(2+) release and promotes cardiac arrhythmogenesis by targeting PP2A regulatory subunit B56alpha and causing CaMKII-dependent hyperphosphorylation of RyR2. CIRC RES. 2009;104:514–521. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhasin N, Cunha SR, Mudannayake M, Gigena MS, Rogers TB, Mohler PJ. Molecular basis for PP2A regulatory subunit B56alpha targeting in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H109–H119. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00059.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musa H, Murphy NP, Curran J, Higgins JD, Webb TR, Makara MA, Wright P, Lancione PJ, Lubbers ER, Healy JA, Smith SA, Bennett V, Hund TJ, Kline CF, Mohler PJ. Common human ANK2 variant confers in vivo arrhythmia phenotypes. HEART RHYTHM. 2016;13:1932–1940. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis MJ, Walker MJ. Quantification of arrhythmias using scoring systems: an examination of seven scores in an in vivo model of regional myocardial ischaemia. CARDIOVASC RES. 1988;22:656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landstrom AP, Dobrev D, Wehrens XHT. Calcium Signaling and Cardiac Arrhythmias. CIRC RES. 2017;120:1969–1993. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng H, Lederer MR, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks and [Ca2+]i waves in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C148–C159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson BR, Makarewich CA, Anderson DM, Winders BR, Troupes CD, Wu F, Reese AL, McAnally JR, Chen X, Kavalali ET, Cannon SC, Houser SR, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. A peptide encoded by a transcript annotated as long noncoding RNA enhances SERCA activity in muscle. SCIENCE. 2016;351:271–275. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobrev D, Wehrens XHT. Role of RyR2 Phosphorylation in Heart Failure and Arrhythmias: Controversies Around Ryanodine Receptor Phosphorylation in Cardiac Disease. CIRC RES. 2014;114:1311–1319. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzimas C, Terrovitis J, Lehnart SE, Kranias EG, Sanoudou D. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) inhibition ameliorates arrhythmias elicited by junctin ablation under stress conditions. HEART RHYTHM. 2015;12:1599–1610. DOI: org/ 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran J, Hinton MJ, Rios E, Bers DM, Shannon TR. Beta-adrenergic Enhancement of Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Leak in Cardiac Myocytes Is Mediated by Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase. CIRC RES. 2007;100:391–398. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258172.74570.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. CELL. 2000;101:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung H, Nairn AC, Murata K, Brautigan DL. Mutation of Tyr307 and Leu309 in the protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit favors association with the alpha 4 subunit which promotes dephosphorylation of elongation factor-2. BIOCHEMISTRY-US. 1999;38:10371–10376. DOI: 10.1021/bi990902g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei M, Wang X, Ke Y, Solaro RJ. Regulation of Ca2+ transient by PP2A in normal and failing heart. FRONT PHYSIOL. 2015;6:13 DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dodge-Kafka KL, Bauman A, Mayer N, Henson E, Heredia L, Ahn J, McAvoy T, Nairn AC, Kapiloff MS. cAMP-stimulated protein phosphatase 2A activity associated with muscle A kinase-anchoring protein (mAKAP) signaling complexes inhibits the phosphorylation and activity of the cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase PDE4D3. J BIOL CHEM. 2010;285:11078–11086. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M109.034868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belevych AE, Sansom SE, Terentyeva R, Ho HT, Nishijima Y, Martin MM, Jindal HK, Rochira JA, Kunitomo Y, Abdellatif M, Carnes CA, Elton TS, Gyorke S, Terentyev D. MicroRNA-1 and −133 increase arrhythmogenesis in heart failure by dissociating phosphatase activity from RyR2 complex. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e28324 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, Yang YM, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of ryanodine receptors: a novel role for leucine/isoleucine zippers. J CELL BIOL. 2001;153:699–708. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu N, Denegri M, Ruan Y, Avelino-Cruz JE, Perissi A, Negri S, Napolitano C, Coetzee WA, Boyden PA, Priori SG. Short Communication: Flecainide Exerts an Antiarrhythmic Effect in a Mouse Model of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia by Increasing the Threshold for Triggered Activity. CIRC RES. 2011;109:291–295. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannankeril PJ, Moore JP, Cerrone M, Priori SG, Kertesz NJ, Ro PS, Batra AS, Kaufman ES, Fairbrother DL, Saarel EV, Etheridge SP, Kanter RJ, Carboni MP, Dzurik MV, Fountain D, Chen H, Ely EW, Roden DM, Knollmann BC. Efficacy of Flecainide in the Treatment of Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:759–766. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe H, Chopra N, Laver D, Hwang HS, Davies SS, Roach DE, Duff HJ, Roden DM, Wilde AAM, Knollmann BC. Flecainide prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and humans. NAT MED. 2009;15:380–383. DOI: 10.1038/nm.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu Y, Xiao S, Hong T, Shaw RM. Cytoskeleton regulation of ion channels. CIRCULATION.2015;131:689–691.DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdi KM, Mohler PJ, Davis JQ, Bennett V. Isoform specificity of ankyrin-B: a site in the divergent C-terminal domain is required for intramolecular association. J BIOL CHEM. 2006;281:5741–5749. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M506697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunha SR, Mohler PJ. Obscurin targets ankyrin-B and protein phosphatase 2A to the cardiac M-line. J BIOL CHEM. 2008;283:31968–31980. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M806050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohler PJ, Hoffman JA, Davis JQ, Abdi KM, Kim CR, Jones SK, Davis LH, Roberts KF, Bennett V. Isoform specificity among ankyrins. An amphipathic alpha-helix in the divergent regulatory domain of ankyrin-b interacts with the molecular co-chaperone Hdj1/Hsp40. J BIOL CHEM. 2004;279:25798–25804. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M401296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith SA, Sturm AC, Curran J, Kline CF, Little SC, Bonilla IM, Long VP, Makara M, Polina I, Hughes LD, Webb TR, Wei Z, Wright P, Voigt N, Bhakta D, Spoonamore KG, Zhang C, Weiss R, Binkley PF, Janssen PM, Kilic A, Higgins RS, Sun M, Ma J, Dobrev D, Zhang M, Carnes CA, Vatta M, Rasband MN, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ. Dysfunction in the βII spectrin-dependent cytoskeleton underlies human arrhythmia. CIRCULATION. 2015;131:695–708. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kizhatil K, Yoon W, Mohler PJ, Davis LH, Hoffman JA, Bennett V. Ankyrin-G and beta2-spectrin collaborate in biogenesis of lateral membrane of human bronchial epithelial cells. J BIOL CHEM. 2007;282:2029–2037. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M608921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. CIRC RES. 2001;88:1159–1167. DOI: org/ 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tzimas C, Johnson DM, Santiago DJ, Vafiadaki E, Arvanitis DA, Davos CH, Varela A, Athanasiadis NC, Dimitriou C, Katsimpoulas M, Sonntag S, Kryzhanovska M, Shmerling D, Lehnart SE, Sipido KR, Kranias EG, Sanoudou D. Impaired calcium homeostasis is associated with sudden cardiac death and arrhythmias in a genetic equivalent mouse model of the human HRC-Ser96Ala variant. CARDIOVASC RES. 2017;113:1403–1417. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvx113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Velasco M, Rueda A, Rizzi N, Benitah JP, Colombi B, Napolitano C, Priori SG, Richard S, Gomez AM. Increased Ca2+ Sensitivity of the Ryanodine Receptor Mutant RyR2R4496C Underlies Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia. CIRC RES. 2009;104:201–209. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. CIRC RES. 2005;97:1314–1322. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiken S, Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, He KK, Prieto A, Becker E, Yi GG, Wang J, Burkhoff D, Marks AR. Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers restore cardiac calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) structure and function in heart failure. CIRCULATION. 2001;104:2843–2848. DOI: org/ 10.1161/hc4701.099578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popescu I, Galice S, Mohler PJ, Despa S. Elevated local [Ca2+] and CaMKII promote spontaneous Ca2+ release in ankyrin-B-deficient hearts. CARDIOVASC RES. 2016;111:287–294. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvw093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camors E, Mohler PJ, Bers DM, Despa S. Ankyrin-B reduction enhances Ca spark-mediated SR Ca release promoting cardiac myocyte arrhythmic activity. J MOL CELL CARDIOL. 2012;52:1240–1248. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terentyev D, Rees CM, Li W, Cooper LL, Jindal HK, Peng X, Lu Y, Terentyeva R, Odening KE, Daley J, Bist K, Choi BR, Karma A, Koren G. Hyperphosphorylation of RyRs Underlies Triggered Activity in Transgenic Rabbit Model of LQT2 Syndrome. CIRC RES. 2014;115:919–928. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeGrande ST, Little SC, Nixon DJ, Wright P, Snyder J, Dun W, Murphy N, Kilic A, Higgins R, Binkley PF, Boyden PA, Carnes CA, Anderson ME, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ. Molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac protein phosphatase 2A regulation in heart. J BIOL CHEM. 2013;288:1032–1046. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M112.426957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huke S, Bers DM. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation at Serine 2030, 2808 and 2814 in rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:80–85.DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirchhefer U, Brekle C, Eskandar J, Isensee G, Kucerova D, Muller FU, Pinet F, Schulte JS, Seidl MD, Boknik P. Cardiac function is regulated by B56alpha-mediated targeting of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) to contractile relevant substrates. J BIOL CHEM. 2014;289:33862–33873. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuvia S, Buhusi M, Davis L, Reedy M, Bennett V. Ankyrin-B is required for intracellular sorting of structurally diverse Ca2+ homeostasis proteins. J CELL BIOL. 1999;147:995–1008. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gigena MS, Ito A, Nojima H, Rogers TB. A B56 regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A localizes to nuclear speckles in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H285–H294. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.01291.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swayne LA, Murphy NP, Asuri S, Chen L, Xu X, McIntosh S, Wang C, Lancione PJ, Roberts JD, Kerr C, Sanatani S, Sherwin E, Kline CF, Zhang M, Mohler PJ, Arbour LT. Novel Variant in the ANK2 Membrane-Binding Domain Is Associated With Ankyrin-B Syndrome and Structural Heart Disease in a First Nations Population With a High Rate of Long QT Syndrome. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2017;10:e1537 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ichikawa M, Aiba T, Ohno S, Shigemizu D, Ozawa J, Sonoda K, Fukuyama M, Itoh H, Miyamoto Y, Tsunoda T, Makiyama T, Tanaka T, Shimizu W, Horie M. Phenotypic Variability of ANK2 Mutations in Patients With Inherited Primary Arrhythmia Syndromes. CIRC J. 2016;80:2435–2442. DOI: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bannister ML, Thomas NL, Sikkel MB, Mukherjee S, Maxwell C, MacLeod KT, George CH, Williams AJ. The Mechanism of Flecainide Action in CPVT Does Not Involve a Direct Effect on RyR2. CIRC RES. 2015;116:1324–1335. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sikkel MB, Collins TP, Rowlands C, Shah M, O’Gara P, Williams AJ, Harding SE, Lyon AR, MacLeod KT. Flecainide reduces Ca(2+) spark and wave frequency via inhibition of the sarcolemmal sodium current. CARDIOVASC RES. 2013;98:286–296. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvt012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.