Capsule Summary:

Among 774 infants with severe bronchiolitis, rhinovirus species related to distinct nasopharyngeal microbiota. Infants with rhinovirus-A were more likely to have Haemophilus-dominant microbiota profile, while those with rhinovirus-C were more likely to have Moraxella-dominant profile.

Keywords: airway microbiota, bronchiolitis, children, infant, microbiome, respiratory infection, rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus

To the Editor:

Bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospitalization in U.S. infants.1 Rhinovirus (RV) is the second most common cause of severe bronchiolitis (i.e., bronchiolitis requiring hospitalization) following respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).1 RVs are RNA viruses consisting of >160 genotypes that are classified into three species (RV-A, B, and C).2 RV-A and RV-C are more frequently found in children with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) and wheezing illnesses than RV-B.3, 4 Emerging evidence suggests a complex interplay between viral infection, airway microbes, and host immune response in the pathobiology of ARI. Studies have shown that RV infection in children is associated with increased detection of pathogenic bacteria in the airways.5, 6 Furthermore, detection of RV together with specific airway pathogens (e.g., M. catarrhalis) is associated with increased ARI and asthma symptoms.6 Recently, RV-A and RV-C were reported to differentially associate with detection of pathogenic bacteria in school-age children.7 However, no study has investigated the relationships between rhinovirus species and airway microbiota in infants, let alone infants with bronchiolitis. To address the knowledge gap, we examined the association between rhinovirus species and the nasopharyngeal airway microbiota determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing in 774 infants with severe bronchiolitis.

This was a post-hoc analysis of the data from the 35th Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC-35) cohort study – a multicenter prospective cohort study of infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis. The details of the study design, setting, virus and microbiota measurements, and analysis are described in the Online Supplement. Briefly, 1,016 infants (age <1 year) hospitalized for bronchiolitis were enrolled in 17 sites across 14 U.S. states (Table E1). Bronchiolitis was defined according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. The institutional review boards at participating sites approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from the infants’ parent or legal guardian. Nasopharyngeal samples were collected within 24 hours of hospitalization and stored at −80 °C locally. These samples were processed and tested for 17 respiratory pathogens by real-time PCR and for microbiota using 16S rRNA gene sequencing at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX). Singleplex real-time PCR was used to detect RV and positive specimens were further genotyped by using molecular typing assay at University of Wisconsin (Madison, WI). By using partitioning around medoids (PAM) unsupervised clustering with the use of weighted UniFrac distance, 4 distinct nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles were derived as previously described.8 In the current analysis, we grouped infants into 4 mutually-exclusive virus categories: solo RSV (reference), RV-A, RV-B, and RV-C. We tested the association between these virus categories and nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles by constructing multinomial logistic regression model adjusting for 8 covariates. Data were analyzed using R version 3.4.4.

Of 1,016 enrolled infants, 774 were in 1 of the 4 pre-specified virus categories (580 RSV-only, 91 RV-A, 12 RV-B, and 91 RV-C) and had high-quality microbiota data; they comprised the analytic sample. Overall, the median age was 2.9 months (interquartile range, 1.6–5.3), 60% were male, and 16% infants received intensive care therapy. Compared to infants with RSV-only, those with RV-A or RV-C were older and more likely to have previous breathing problems (P<0.001; Table E2).

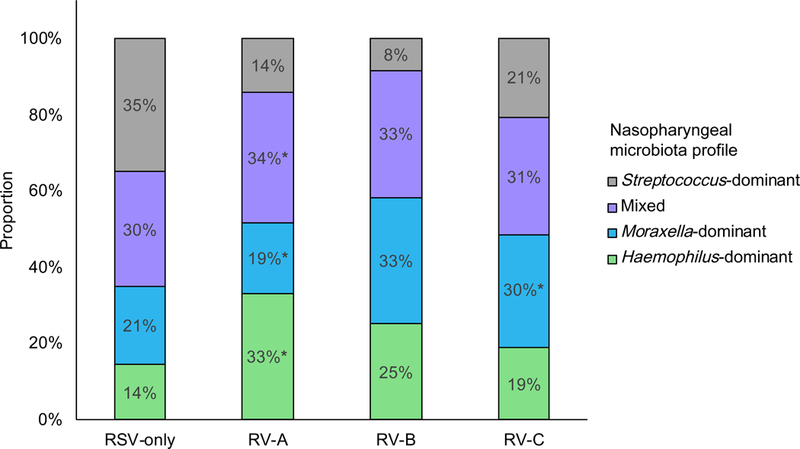

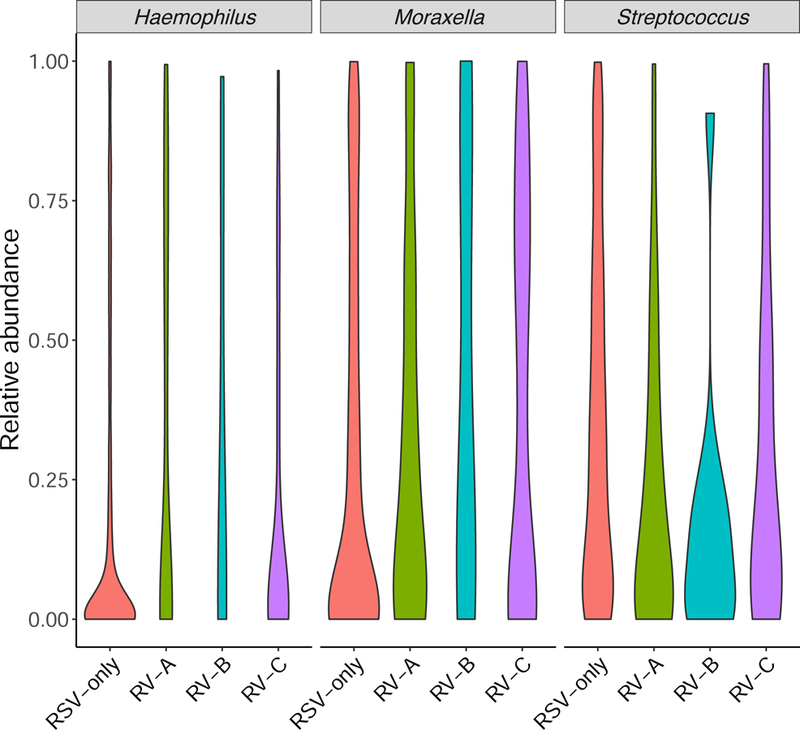

Across the virus categories, there was a significant difference in the likelihood of nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles (P<0.001; Table E3). For example, while infants with RSV had a highest likelihood of Streptococcus-dominant profile (the reference virus and microbiota profile), those with RV-A had a highest likelihood of Haemophilus-dominant profile (Figure 1A), corresponding to an adjusted relative rate ratio (RRR) of 5.67 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.76–11.67, P<0.001; Table 1). In contrast, infants with RV-C were more likely to have Moraxella-dominant profile than Streptococcus-dominant profile (adjusted RRR 2.69, 95%CI 1.39–5.20, P=0.003). Similarly, at the genus-level (Figure 1B and Table E3), compared to infants with RSV-only, those with any RV species had lower relative abundance of Streptococcus (P=0.002) and those with RV-A had higher abundance of Haemophilus (P=0.002).

Figure 1. Between-virus difference in nasopharyngeal microbiota in infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis.

A) Between the four virus categories, the proportion of nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles differed. For example, compared to infants with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-only bronchiolitis, those with rhinovirus (RV)-A infection were more likely to have a Haemophilus-dominant, mixed, or Moraxella-dominant profile than a Streptococcus-dominant profile. Infants with RV-C were more likely to have a Moraxella-dominant profile. P-values were derived from adjusted multinomial logistic regression model. Corresponding relative rate ratios are shown in Table 1. * P<0.05

B) Between the four virus categories, the distribution of relative abundance of three most common genera in the nasopharyngeal microbiota differed. Data are presented using violin plots which are boxplots with a rotated kernel density plot on each side. P-values adjusted for multiple comparisons are shown in Table E3. RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus

Table 1.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations of respiratory viruses (exposure) with nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles (outcome) in infants hospitalized for bronchiolitis

| Microbiota profiles |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemophilus-dominant n=133 | Moraxella-dominant n=167 | Mixed profile n=239 | Streptococcus-dominant n=235 | ||||

| Model and virus category | RRR (95% CI) | P-value | RRR (95% CI) | P-value | RRR (95% CI) | P-value | RRR (95% CI) |

| Unadjusted model | |||||||

| RSV-only (n=580) | reference | reference | reference | reference | |||

| RV-A (n=91) | 5.62 (2.79–11.30) | <0.001 | 2.22 (1.04–4.73) | 0.04 | 2.74 (1.39–5.39) | 0.004 | reference |

| RV-B (n=12) | 7.30 (0.75–71.21) | 0.09 | 6.79 (0.75–61.46) | 0.09 | 4.59 (0.51–41.50) | 0.17 | reference |

| RV-C (n=91) | 2.18 (1.08–4.40) | 0.03 | 2.41 (1.29–4.53) | 0.006 | 1.69 (0.91–3.13) | 0.09 | reference |

| Adjusted modela | |||||||

| RSV-only (n=580) | reference | reference | reference | reference | |||

| RV-A (n=91) | 5.67 (2.76–11.67) | <0.001 | 2.26 (1.05–4.89) | 0.04 | 2.74 (1.38–5.44) | 0.004 | reference |

| RV-B (n=12) | 7.50 (0.74–76.08) | 0.09 | 5.72 (0.62–52.71) | 0.12 | 4.73 (0.52–43.04) | 0.17 | reference |

| RV-C (n=91) | 1.81 (0.86–3.81) | 0.12 | 2.69 (1.39–5.20) | 0.003 | 1.57 (0.83–2.96) | 0.17 | reference |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RRR, relative rate ratio; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus

Multinomial logistic regression model adjusting for 8 patient-level covariates (age, sex, race/ethnicity, gestational age, siblings in the household, breastfeeding, history of breathing problems, and lifetime history of systemic antibiotic use). RSV-only infection was used as the reference of exposure (virus category) and Streptococcus-dominant microbiota profile was used as the reference for the outcome (nasopharyngeal microbiota profile).

Earlier studies reported that RV-C infection is associated with higher risks of subsequent ARI in young children4 and that enrichment of Moraxella abundance in the upper airways is related to higher frequency of ARIs.9 Furthermore, a recent analysis from RhinoGen study (310 children [aged 4–12 years] with or without asthma, using quantitative PCR for 3 bacteria) reported that RV-A and RV-C are differentially associated with increased quantity of H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, and S. pneumoniae.7 Our observations – e.g., the association between RV-C and higher likelihood of Moraxella-dominant microbiota – corroborate these earlier findings, and extend them by applying 16S rRNA gene sequencing to the airway samples of a large multicenter prospective cohort of infants with severe bronchiolitis.

The underlying mechanisms of the virus-microbiota relationships are beyond the scope of our data. The observed associations may be causal – i.e., specific respiratory virus species (e.g., RV-C) alters the airway microbiota.6 Alternatively, unique microbiota profiles in conjunction with airway immune response might have contributed to susceptibility to specific virus infection. These potential mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Despite this complexity, the identification of the association between specific virus species and airway microbiota in infants with bronchiolitis is important given their relation to subsequent respiratory health in children

Our study has potential limitations. First, the study design precluded us from examining the relation between the temporal pattern of airway microbiota and respiratory health in children. To address this question, the cohort is currently being followed longitudinally for 6+ years with serial examinations of microbiota. Second, the current study did not have healthy controls. However, the study aim was to determine the association of virus species with microbiota among infants with bronchiolitis. Finally, while the study cohort comprised a racially/ethnically diverse US sample of infants, we must generalize the inferences cautiously beyond infants with severe bronchiolitis. Regardless, our data are highly relevant for 130,000 U.S. children hospitalized with bronchiolitis each year.1

In summary, based on this multicenter prospective cohort study of infants with severe bronchiolitis, we observed that, compared to RSV-only infection, infants with RV-A or RV-C infection had distinct nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles – e.g., those with RV-C had a higher likelihood of Moraxella-dominant microbiota profile whereas those with RV-A had a higher likelihood of Haemophilus-dominant profile. While causal inferences remain premature, our data should advance research into delineating the complex interrelations between respiratory viruses, airway microbiome, and respiratory outcomes in children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the MARC-35 study hospitals and research personnel for their ongoing dedication to bronchiolitis and asthma research (Table E1 in the Online supplement), and Janice A. Espinola, MPH, Ashley F. Sullivan, MS, MPH, and Courtney N. Tierney, MPH (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) for their many contributions to the MARC-35 study. We also thank Joseph F. Petrosino, PhD, at Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research, Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology, Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX) for 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis and Alkis Togias, MD, at the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) for helpful comments about the study results.

Financial support: The current analysis was supported by grants UG3 OD-023253, U01 AI-087881, R01 AI-134940, and R01 AI-137091 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Toivonen was supported by the Finnish Medical Foundation and Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- ARI

acute respiratory infection

- RRR

relative rate ratio

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- RV

rhinovirus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA Jr. Infectious pathogens and bronchiolitis outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014;12:817–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bochkov YA, Gern JE. Rhinoviruses and their receptors: Implications for allergic disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2016;16:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwane MK, Prill MM, Lu X, Miller EK, Edwards KM, Hall CB, et al. Human rhinovirus species associated with hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young US children. J Infect Dis 2011;204:1702–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox DW, Bizzintino J, Ferrari G, Khoo SK, Zhang G, Whelan S, et al. Human rhinovirus species C infection in young children with acute wheeze is associated with increased acute respiratory hospital admissions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:1358–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karppinen S, Terasjarvi J, Auranen K, Schuez-Havupalo L, Siira L, He Q, et al. Acquisition and transmission of Streptococcus pneumoniae are facilitated during rhinovirus infection in families with children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloepfer KM, Lee WM, Pappas TE, Kang TJ, Vrtis RF, Evans MD, et al. Detection of pathogenic bacteria during rhinovirus infection is associated with increased respiratory symptoms and asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:1301–7, 7.e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashir H, Grindle K, Vrtis R, Vang F, Kang T, Salazar L, et al. Association of rhinovirus species with common cold and asthma symptoms and bacterial pathogens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141:822–4.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Ajami NJ, Espinola JA, Henke DM, Petrosino JF, et al. Association of nasopharyngeal microbiota profiles with bronchiolitis severity in infants hospitalised for bronchiolitis. Eur Respir J 2016;48:1329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch AA, de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, van Houten MA, Chu M, Biesbroek G, Kool J, et al. Maturation of the infant respiratory microbiota, environmental drivers and health consequences: a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1582–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.