Abstract

Objective:

To examine snacking patterns, food sources, and nutrient profiles of snacks in low- and middle- income Chilean children and adolescents.

Design:

Cross-sectional. Dietary data were collected via 24-hour food recalls. We determined the proportion of snackers, snacks per day, and calories from top food and beverage groups consumed. We compared the nutrient profile (energy, sodium, total sugars, and saturated fat) of snacks versus meals.

Setting:

Southeast region of Chile.

Subjects:

Children and adolescents from 2 cohorts: the Food Environment Chilean Cohort (n = 958, 4– 6 years old) and the Growth and Obesity Cohort Study (n = 752, 12–14 years old).

Results:

With an average of 2.30 ± 0.03 snacks per day consumed, 95.2% of children and 89.9% of adolescents reported at least 1 snacking event. Snacks contributed on average 360 kilocalories per day in snacking children and 530 kilocalories per day in snacking adolescents (29.0% and 27.4% daily energy contribution, respectively). Grain-based desserts, salty snacks, other sweets and desserts, dairy foods, and cereal-based foods contributed the most energy from snacks in the overall sample. For meals, cereal- based foods, dairy beverages, meat and meat substitutes, oils and fats, and fruits and vegetables were the top energy contributors.

Conclusions:

Widespread snacking among Chilean youth provides over a quarter of their kilocalories per day and includes foods generally considered high in energy, saturated fat, sodium, and/or total sugars. Future research should explore whether snacking behaviors change as the result of Chile’s national regulations on food marketing, labeling and school environments.

Keywords: snacking, Chile, Children, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

The past four decades have seen a worldwide increase in obesity and noncommunicable diseases.(1; 2) In Latin America many countries face the malnutrition double burden.(3; 4) Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable,(5; 6) as a high body mass index in childhood or adolescence has been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease later in life.(7)

In Chile 74.4% of the population was either overweight or obese in 2016(8) compared to 64.3% in 2009,(9) and obesity-related health problems were prevalent, with high blood pressure and diabetes affecting 27.5% and 9.4% of the population, respectively.(8) In the Chilean diet processed and ultraprocessed foods(10) account for 55.2% of the total calorie consumption. Processed foods include items such as bread, cheese, and canned fruits and vegetables. (11) Ultraprocessed foods include chips, ice cream, chocolate and other candies, and carbonated drinks, among others. Ultraprocessed foods in particular have been associated with excess weight (12; 13) and hypertension.(14) Only 12.9% of the population adheres to the recommendations of the Chilean National Dietary Guidelines.(15) Furthermore, less than a fifth of the population consumes 5 or more servings of fruits or vegetables per day, less than 15.0% consumes whole grains at least once a day, and less than 50.0% consumes fish or seafood once or more per week.(9)

Despite this evidence of generally unhealthy diets, little is known about the extent of snacking behaviors and the types of snacks the Chilean population consumes. Snacking is prevalent in the high- income North American countries Canada (16) and the United States (17; 18) and in Latin America, including Brazil (19) and Mexico.(20; 21) Identifying snacking patterns is particularly important for children and adolescents, since eating behaviors are acquired early and track into adulthood.(22) Moreover, some evidence suggests that snacking may be linked to increased energy intake (23–25) and also that snacking on energy-dense or unhealthy foods may contribute to overweight status,(26) suggesting that the types of snacks consumed are important. Furthermore, social, environmental, and individual factors affect snack selection and consumption.(27) The objective of this study was to examine snacking patterns and snack food and beverage sources in Chilean children and adolescents in 2016 and compare the nutrient profiles of foods selected as snacks versus those eaten at main meals.

METHODS

Study design and sample

This study includes dietary data from 2 cohorts: the Growth and Obesity Cohort Study (GOCS) and the Food Environment Chilean Cohort (FECHIC), both recruited from low- and middle-income neighborhoods in the southeastern area of Santiago, Chile. The GOCS started in 2006 and enrolled children (n = 1,195) who attended 54 nursery schools in the National Nursery Schools Council Program (JUNJI, acronym for the name in Spanish).(28; 29) The GOCS participants visited the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology Diagnostic Clinic (CEDINTA) at least once per year for a physical examination, which included dietary assessments starting in 2012. In 2016 dietary data were collected for 80.8% of the 953 GOCS participants (n = 770). The GOCS included children who were a single birth with a birthweight > 2,500 grams (g), who were enrolled the previous year in a JUNJI center, and who did not have physical or psychological conditions that could severely affect growth.(28) In 2016 these children were 12–14 years old and constituted our adolescent group.

The FECHIC included children 4–6 years old (born between 2010 and 2012) who attended 1 of 55 public schools in 2016. Because of the young ages of these children, they were invited to participate along with their mothers, since in Chile mothers are the primary caregivers and the main household food preparers, enabling them to respond to the questionnaires and dietary recalls for their children. Of 2,625 families who initially expressed interest, 962 enrolled in the study. The FECHIC included children who attended the contacted schools, who were single births, whose mothers were the primary caregivers and were in charge of food purchases for the home, and who (along with their mothers) had no mental illnesses or gastrointestinal diseases that would affect food consumption. The dietary data of 18 GOCS participants and 4 FECHIC participants were not reliable enough to be included in the analysis; therefore, our total analytic sample was 1,710: 752 GOCS participants and 958 FECHIC participants.

We obtained informed consent from the mothers of participants; in the case of adolescents, we also obtained an assent prior to conducting the interviews. The ethics committee of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA) approved the study protocol. The study was exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, because the university had no contact with the human subjects and received only secondary unidentified data.

Dietary assessment and food groups

The data analyzed in this study were collected between April and July of 2016 either at the study participants’ homes or at the CEDINTA. Trained nutritionists conducted 24-hour food recalls using a multiple-pass method assisted by computer software (SER-24) developed for that purpose. For preschool children, mothers were the primary reporters of dietary intake, and the children provided complementary information for times when the mother was not present. Interviewers used a food atlas (30) with images of bowls, plates, mugs, and glasses to assess serving sizes of common Chilean foods and beverages. Interviewers entered participants’ responses directly into SER-24, and a second nutritionist reviewed the information later to check for inconsistencies and to ensure quality in reported data. When 2 interviews were available for the same participant, we used only the first day’s data.

We used the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrient Database,(31) which contains nutrient information searchable by food item, food group, or manufacturer’s name, to calculate nutrient values. To determine the nutrient values for traditional Chilean dishes not present in the USDA Food and Nutrient Database we separated the specific ingredients and quantities and found the closest match to each ingredient using this same USDA database.(31)

Our team adapted food and beverage groups from a system previously developed at the Public Health Nutrition Department of the INTA(32) (Supplemental Table 1). We disaggregated the components of mixed dishes and classified them correspondingly (i.e., for arroz a la jardinera, we grouped rice with cereals and onions and peppers with vegetables) except for those dishes that, according to the previously established groups, were of interest when consumed as a whole. For example, sopaipilla, fried pumpkin dough; completo, traditional Chilean-style hot dog; and pizza were not disaggregated into ingredients (Supplemental Table 2).

Definitions of meals and snacks

Participants identified the names and times of eating occasions (EO) during the interviews. They reported EOs as either breakfast, colación (a small meal or snack), lunch, once (a small late afternoon meal), dinner, or picoteo (a snack or small appetizer). Participants could report several instances per type of EO, for example, 2 breakfasts at different times, but each EO could have only 1 label, that is, an EO could not be identified as both breakfast and snack. For our analyses, we always considered breakfast, lunch, once, and dinner a main meal, whereas we considered colación and picoteo snacks.

Once, a sit-down meal, typically consists of bread; an assortment of fixings, such as avocado, jam, butter, and cheese; and coffee or tea. Depending on one’s lifestyle and upbringing, once sometimes replaces dinner. Due to the large proportion of our sample reporting once and not dinner, for our analysis we considered it a meal and not a snack. A study conducted in Mexico (20) similarly considered almuerzo, which is usually midmorning but before lunch, a meal and not a snack.

We defined frequency of snacking based on the number of snack EOs reported per day, which ranged from 0 to 10. For descriptive purposes only, we classified respondents as nonsnackers (0 snacks per day), light snackers (1–2 snacks per day), and heavy snackers (≥ 3 snacks per day), an approach previously used elsewhere.(19) Participants also reported the locations of EOs as home, school, another person’s home, mall or food court, restaurant, work, street, transportation, or other.

Statistical analyses

We determined the proportion of children and adolescents consuming snacks and the mean number (standard error [SE]) of snacks consumed per age group, gender, and mother’s education level (less than high school, high school completed, and above high school) and explored differences using chi-square tests and t-tests at a significance of p < 0.05. We also determined per capita and per consumer energy intake from snacks versus meals and explored differences within each age group. Per capita refers to the mean consumption using our total sample as a denominator (stratified by age group), and per consumer refers to the mean consumption of a food group among those who reported consuming it. We then determined the top 10 food and beverage groups consumed as snacks and meals based on mean per capita contribution, the percentage of consumers for each food or beverage group, and the mean energy contributions of these food and beverage groups to the total energy intake among consumers.

Finally, we determined energy (kilocalories [kcals]) and nutrient density (macronutrients, saturated fat, total sugars, fiber, and sodium) intake per 100 g of foods and beverages consumed as snacks versus meals for each participant. For example, we calculated energy density for snacks as (kcals from snacks*100)/total g of snacks. We calculated measures per 100 g because using product weight allowed us to understand the energy density across different products and eased comparability between different EOs. We analyzed sodium, total sugars, and saturated fats in addition to macronutrients since they are the nutrients defined in recent Chilean food regulations (33; 34) as critical nutrients whose excess consumption should be avoided. Additionally, these nutrients have been defined as critical by global health organizations, (35) due to their link with obesity and non-communicable diseases. In such regulations, cut points are established per 100 g of a product. We used paired t-tests at a significance level of 0.05 to compare the nutrient profiles of snacks versus meals within each age group. We used STATA version 14.3 (36) for all analyses.

RESULTS

Overall eating occasions

Children reported slightly more EOs than adolescents (5.7 vs. 5.3 EOs/day, p < 0.05), likely due to a greater percentage of children reporting colación and dinner than adolescents (Table 1). More children than adolescents consumed breakfast, colación, and dinner (95.6% vs. 87.2%, 81.0% vs. 54.6%, and 43.3% vs. 17.8%, respectively, p < 0.05). More adolescents than children consumed picoteo (72.1% vs. 63.3%, p < 0.05). Less than half of the participants in both age groups reported dinner (43.3% in children, 17.8% in adolescents), suggesting that many might either substitute once for dinner or might have referred to dinner as such.

Table 1.

Mean kcal and percentage kcal consumed per day and snacking frequency among the sample

| Children (n = 958) | Adolescents (n = 752) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 465) | Females (n = 493) | Males (n = 377) | Females (n = 375) | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| Per capita total energy intake (kcal) | 1,244 | 18.4 | 1,172 | 17.4 | 1,991 | 32.5 | 1,700 | 32.0 | ||||

| Per capita energy intake from snacks (kcal) | 368 | 12.4 | 352 | 11.2 | 538 | 24.9 | 521 | 25.0 | ||||

| Per capita energy intake from snacks (% total) | 28.8 | 0.8 | 29.3 | 0.7 | 26.1 | 1.0 | 28.7 | 1.1 | ||||

| Percentage snackers† | 94.8 | — | 95.5 | — | 89.1 | — | 90.7 | — | ||||

| Per snackerb energy intake from snacks (kcal) | 388 | 12.4 | 368 | 11.2 | 603 | 25.8 | 575 | 25.4 | ||||

| Per snacker energy intake from snacks (% total) | 30.4 | 0.8 | 30.6 | 0.7 | 29.3 | 1.0 | 31.7 | 1.0 | ||||

| Snacking frequency (%) | ||||||||||||

| Nonsnackers (0 snacks/day) | 5.2 | — | 4.5 | — | 10.9 | — | 9.3 | — | ||||

| Light snackers (1–2 snacks/day) | 53.3 | — | 57.2 | — | 53.9 | — | 47.2 | — | ||||

| Heavy snackers (≥ 3 snacks/day) | 41.5 | — | 38.3 | — | 35.3 | — | 43.5 | — | ||||

| Eating occasion frequency (%) | ||||||||||||

| Breakfast | 96.3 | * | 94.9 | * | 87.8 | * | 86.7 | * | ||||

| Lunch | 94.6 | — | 95.9 | — | 94.7 | — | 94.9 | — | ||||

| Once | 76.8 | — | 79.9 | — | 83.0 | — | 80.3 | — | ||||

| Dinner | 44.3 | * | 42.4 | * | 18.8 | * | 16.8 | * | ||||

| Colación | 82.8 | * | 79.3 | * | 54.1 | * | 55.2 | * | ||||

| Picoteo | 60.7 | * | 65.7 | * | 70.0 | * | 74.1 | * | ||||

Participants reporting ≥ 1 snack/day.

Indicates the difference between children and adolescents by sex by chi-square tests for each type of EO (p < 0.05).

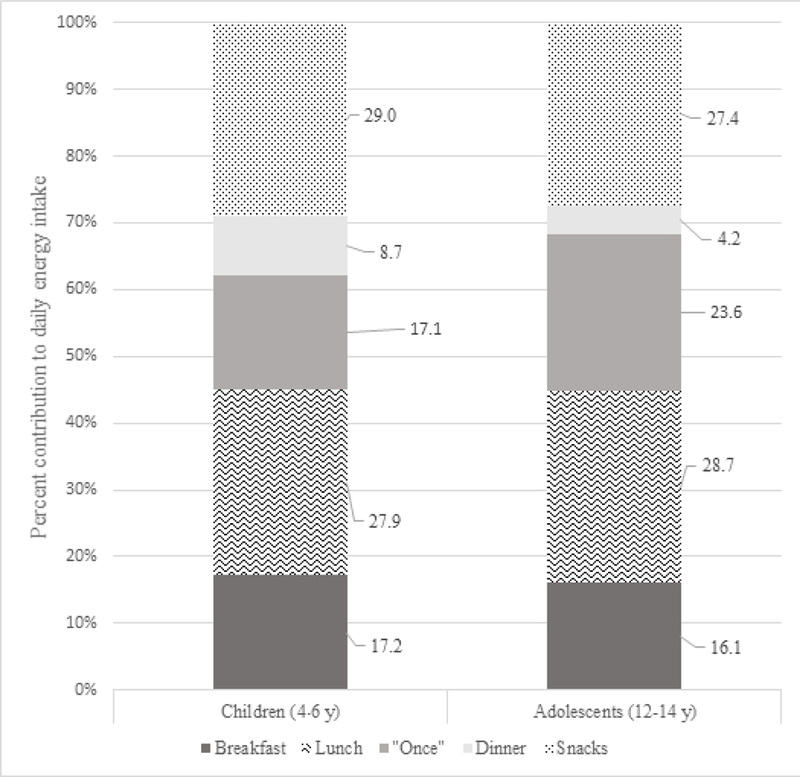

As Figure 1 shows, lunch contributed the most to total daily energy intake in both age groups (27.9% in children, 28.7% in adolescents), followed by once (17.1% in children, 23.6% in adolescents) and dinner (17.2% in children, 16.1% in adolescents). The per capita contribution of dinner to total energy intake was small in both age groups (8.7% in children, 4.2% in adolescents), which is expected due to the small percentage of participants that reported consumption of dinner.

Figure 1.

Percentage contribution of each type of EO of FECHIC (children) and GOCS (adolescents) study participants (n = 1,710), 2016.

General snacking patterns

Snacking was a prevalent behavior in both age groups, with 95.2% of children and 89.9% of adolescents reporting at least 1 snacking event in the previous day (Table 1). Snacks contributed on average 360 daily kcals in children and 530 kcals in adolescents. Furthermore, the mean daily energy contribution from snacks was 29.0% for children and 27.4% for adolescents (Figure 1). The mean number of meals, snacks, and EOs per day did not differ significantly by sex in children (Table 2), however, adolescent females reported slightly more snacks than adolescent males (2.50 ± 0.09 vs. 2.20 ± 0.08 snacks/day).

Table 2.

Eating occasions (EO) per day by sociodemographic characteristics of participants in the FECHIC and the GOCS included in the analyses, 2016

| Variable | N | Children (FECHIC, 4–6 years) | N | Adolescents (GOCS, 12–14 years) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snacks/day | Meals/day | Total EOs/day | Snacks/day | Meals/day | Total EOs/day | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Male (reference) | 465 | 2.32 | 0.06 | 3.37 | 0.04 | 5.70 | 0.07 | 377 | 2.19 | 0.08 | 3.03 | 0.04 | 5.22 | 0.08 |

| Female | 493 | 2.29 | 0.05 | 3.40 | 0.04 | 5.70 | 0.06 | 375 | 2.47 | 0.08* | 2.96 | 0.04 | 5.43 | 0.09* |

| Mother’s Education Level | ||||||||||||||

| Less than high school (reference) | 173 | 2.28 | 0.08 | 3.28 | 0.06 | 5.56 | 0.09 | 213 | 2.19 | 0.11 | 2.96 | 0.06 | 5.15 | 0.11 |

| High school completed | 396 | 2.31 | 0.06 | 3.45 | 0.05* | 5.76 | 0.07 | 335 | 2.48 | 0.09* | 2.93 | 0.04 | 5.42 | 0.09 |

| More than high school | 389 | 2.32 | 0.06 | 3.36 | 0.04 | 5.68 | 0.07 | 169 | 2.14 | 0.11 | 3.16 | 0.06* | 5.30 | 0.12 |

Indicates the difference from the reference group, p < 0.05. Independent sample t-test used for the mean number of snacks, meals, and EOs when comparing males and females. Linear regression model used to determine

Top foods and beverages consumed

The food and beverage categories consumed as snacks were similar among children and adolescents, with 8 of the top 10 groups present in both age groups (grain-based desserts, dairy products, other sweets and desserts, fruit-flavored drinks, salty snacks, fruits and vegetables, cereal-based foods, and fast food). Dairy beverages and ready-to-eat breakfast cereals ranked in the top 10 in children, whereas empanadas and sopaipillas and carbonated beverages ranked in the top 10 in adolescents (Tables 3a and 3b). Fruits and vegetables were the most commonly consumed snack food category in children (40.0%), but grain- based desserts ranked first in adolescents (46.0%).

Table 3a.

Daily energy intake per capita, percentage of consumption, and energy intake per consumer for the top 10 food and beverage groups consumed as snacks and meals in the FECHIC cohort (children), 2016

| Rank | Food group | Kcal/capita† |

Consumers‡ |

Kcal/consumer§ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | N | % | Mean | SE | ||

| Snacks | |||||||

| 1 | Grain-based desserts | 80 | 4 | 360 | 37.6 | 212 | 8 |

| 2 | Dairy beverages | 44 | 3 | 321 | 33.5 | 130 | 5 |

| 3 | Dairy foods | 43 | 2 | 333 | 34.8 | 124 | 3 |

| 4 | Other sweets and desserts | 34 | 3 | 263 | 27.5 | 122 | 9 |

| 5 | Fruit-flavored drinks | 28 | 2 | 227 | 23.7 | 116 | 3 |

| 6 | Salty snacks | 27 | 3 | 128 | 13.4 | 201 | 16 |

| 7 | Fruits and vegetables | 24 | 1 | 383 | 40.0 | 61 | 2 |

| 8 | Cereal-based foods | 18 | 1 | 168 | 17.5 | 103 | 4 |

| 9 | Ready-to-eat breakfast cereals | 15 | 1 | 154 | 16.1 | 92 | 3 |

| 10 | Fast food | 9 | 2 | 45 | 4.7 | 191 | 16 |

| Meals | |||||||

| 1 | Cereal-based foods | 210 | 5 | 890 | 92.9 | 226 | 5 |

| 2 | Dairy beverages | 163 | 4 | 818 | 85.4 | 191 | 5 |

| 3 | Meat and meat substitutes | 73 | 3 | 689 | 71.9 | 101 | 3 |

| 4 | Fruits and vegetables | 69 | 3 | 847 | 88.4 | 78 | 3 |

| 5 | Oils and fats | 66 | 2 | 825 | 86.1 | 77 | 2 |

| 6 | Dairy foods | 39 | 2 | 334 | 34.9 | 110 | 3 |

| 7 | Grain-based desserts | 34 | 3 | 160 | 16.7 | 201 | 12 |

| 8 | Legumes | 29 | 2 | 336 | 35.1 | 82 | 6 |

| 9 | Fast food | 23 | 3 | 81 | 8.5 | 263 | 20 |

| 10 | Eggs | 20 | 1 | 267 | 27.9 | 73 | 3 |

Mean daily per capita food group intake (including both consumers and nonconsumers of each food group). For all food groups, the mean total energy intake was 1,207 kcal.

Indicates the number of participants reporting each food group as a snack or a meal.

Mean daily kcal per food group among consumers.

Table 3b.

Daily energy intake per capita, percentage of consumption, and energy intake per consumer for the top 10 food and beverage groups consumed as snacks and meals in the GOCS cohort (adolescents), 2016

| Rank | Food group | Kcal/capita† |

Consumers‡ |

Kcal/consumer§ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | N | % | Mean | SE | ||

| Snacks | |||||||

| 1 | Grain-based desserts | 152 | 9 | 344 | 45.7 | 331 | 14 |

| 2 | Salty snacks | 73 | 7 | 164 | 21.8 | 332 | 23 |

| 3 | Cereal-based foods | 50 | 4 | 168 | 22.3 | 223 | 11 |

| 4 | Other sweets and desserts | 47 | 4 | 231 | 30.7 | 154 | 10 |

| 5 | Empanadas and sopaipillas | 28 | 4 | 53 | 7.0 | 386 | 32 |

| 6 | Carbonated beverages | 27 | 3 | 131 | 17.4 | 152 | 9 |

| 7 | Dairy foods | 25 | 2 | 149 | 19.8 | 125 | 5 |

| 8 | Fast food | 24 | 4 | 47 | 6.3 | 380 | 41 |

| 9 | Fruits and vegetables | 23 | 2 | 216 | 28.7 | 81 | 5 |

| 10 | Fruit-flavored drinks | 17 | 2 | 98 | 13.0 | 131 | 8 |

| Meals | |||||||

| 1 | Cereal-based foods | 422 | 10 | 716 | 95.2 | 442 | 9 |

| 2 | Meat and meat substitutes | 147 | 7 | 573 | 76.2 | 193 | 8 |

| 3 | Fast food | 89 | 9 | 126 | 16.8 | 528 | 32 |

| 4 | Oils and fats | 87 | 3 | 632 | 84.0 | 104 | 3 |

| 5 | Fruits and vegetables | 80 | 3 | 639 | 85.0 | 94 | 4 |

| 6 | Grain-based desserts | 79 | 8 | 153 | 20.3 | 387 | 29 |

| 7 | Dairy beverages | 63 | 4 | 333 | 44.3 | 143 | 5 |

| 8 | Dairy foods | 57 | 4 | 299 | 39.8 | 142 | 7 |

| 9 | Carbonated beverages | 50 | 3 | 244 | 32.4 | 152 | 6 |

| 10 | Empanadas and sopaipillas | 48 | 7 | 55 | 7.3 | 643 | 50 |

Mean daily per capita food group intake (including both consumers and nonconsumers of each food group). For all food groups, the mean total energy intake was 1,207 kcal.

Indicates the number of participants reporting each food group as a snack or a meal.

Mean daily kcal per food group among consumers.

Similarly, for foods and beverages consumed as meals, 8 out of the top 10 food groups were the same in both age groups (cereal-based foods, dairy beverages, meat and meat substitutes, fruits and vegetables, oils and fats, dairy foods, grain-based desserts, and fast food). Legumes and eggs were among the other top energy contributors in children, whereas for adolescents carbonated beverages and empanadas and sopaipillas ranked in the top 10 (Tables 3a and 3b).

Nutrient profile by eating occasion

As Table 4 shows, while snacks contributed about a third of the daily energy (kcal/100 g) in both age groups, they more contributed more to the total daily sugar intake (41.7% in children, 38.5% in adolescents) and slightly less to the total daily protein intake (20.0% in children, 17.4% in adolescents) than would be expected given their energy contribution compared to that of meals. Among participants who reported at least 1 meal and 1 snack in a day (n = 1,585), the daily energy density was higher for snacks (124 kcal/100 g for children, 187 kcal/100 g for adolescents) than for meals (85 kcal/100 g for children, 103 kcal/100 g for adolescents) in both age groups (p < 0.05). Furthermore, snacks were significantly less protein dense and more carbohydrate, total sugars, total fat, and saturated fat dense than meals.

Table 4.

Nutrient profile (expressed in quantities per 100 g) of snacks and meals according to age group

| Children (n = 958) |

Adolescents (n = 752) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snacks† |

Meals‡ |

Snacks† |

Meals‡ |

|||||||||||||

| % of total intake | per 100 g | % of total intake | per 100 g | % of total intake | per 100 g | % of total intake | per 100 g | |||||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Energy, kcal | 28.9 | 0.5 | 124* | 3 | 71.1 | 0.5 | 85* | 1 | 27.4 | 0.7 | 187* | 5.1 | 72.6 | 0.7 | 103* | 1.2 |

| Macronutrient intake | ||||||||||||||||

| Total protein (g) | 20.0 | 0.5 | 2.9* | 0.1 | 80.0 | 0.5 | 3.5* | 0.0 | 17.4 | 0.6 | 3.3* | 0.103 | 82.6 | 0.6 | 4.1* | 0.1 |

| Total carbohydrates (g) | 32.8 | 0.6 | 20.0* | 0.4 | 67.2 | 0.6 | 11.6* | 0.1 | 29.3 | 0.8 | 27.5* | 0.704 | 70.7 | 0.8 | 13.9* | 0.2 |

| Fiber, g | 28.7 | 0.7 | 1.1* | 0.0 | 71.3 | 0.7 | 0.8* | 0.0 | 26.1 | 0.8 | 1.4* | 0.052 | 73.9 | 0.8 | 0.9* | 0.0 |

| Total sugars (g) | 41.7 | 0.7 | 12.1* | 0.2 | 58.3 | 0.7 | 4.8* | 0.1 | 38.5 | 0.9 | 14.2* | 0.472 | 61.5 | 0.9 | 4.4* | 0.1 |

| Total fat (g) | 26.4 | 0.7 | 4.0* | 0.2 | 73.6 | 0.7 | 2.8* | 0.0 | 28.9 | 0.9 | 7.5* | 0.301 | 71.1 | 0.9 | 3.5* | 0.1 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 28.6 | 0.7 | 1.5* | 0.1 | 71.4 | 0.7 | 0.9* | 0.0 | 30.8 | 0.9 | 2.6* | 0.129 | 69.2 | 0.9 | 1.1* | 0.0 |

| Micronutrient intake | ||||||||||||||||

| Sodium (milligrams) | 24.7 | 0.7 | 95 | 4 | 75.3 | 0.7 | 90 | 2 | 22.7 | 0.8 | 152* | 6 | 77.3 | 0.8 | 131* | 3 |

Snack energy/nutrient density calculated for 912 children and 676 adolescents who reported at least 1 snack.

Meal energy/nutrient density calculated for 957 children and 750 adolescents who reported at least 1 meal.

p < 0.05. Paired sample t-test comparing snack versus meal densities within each age group.

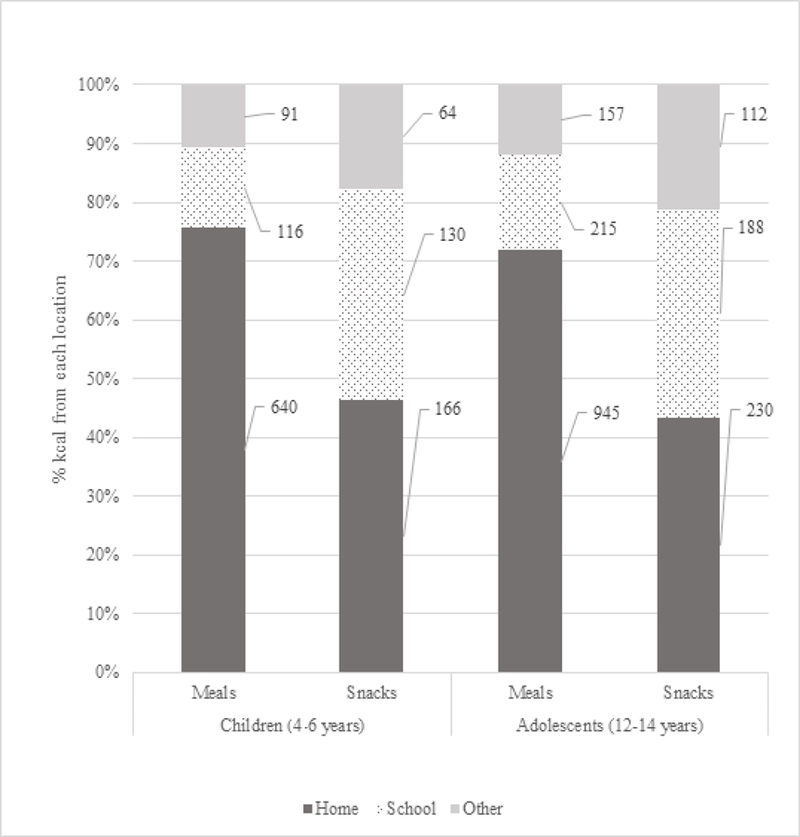

Meal and snack consumption locations

Most of the daily energy intake from both snacks and meals was consumed at participants’ homes (806 kcal for children, 1,175 kcal for adolescents) or school (246 kcal for children, 403 kcal for adolescents) (Figure 2). However, both groups reported a larger percentage of calories from snacks consumed at school, 35.5–36.0%, compared to 13.7–16.3% from meals. That is, on average children consumed 130 kcal in snacks at school, and adolescents consumed 188 kcal in snacks at school. In contrast, on average children consumed 116 kcal in meals at school and adolescents 215 kcal.

Figure 2.

Per capita energy intake (kcal) provided by location per type of EO of FECHIC (children) and GOCS (adolescents) study participants (n = 1,710), 2016.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that snacking is prevalent among Chilean children and adolescents. Snacking accounts for 29.0% and 27.4%, respectively, of the mean daily energy consumption in children and adolescents. In total 95.2% of the children and 89.9% of the adolescents in our study consumed at least 1 snack per day, with a mean per capita of 2.30 ± 0.03 snacks consumed per day. Grain-based desserts, salty snacks, other sweets and desserts, dairy foods, cereal-based foods, dairy beverages, fruits and vegetables, fruit- flavored drinks, fast food, and sopaipillas and empanadas contributed the most energy from snacks in the overall sample.

To our knowledge this is the first study to thoroughly report on snacking patterns in Chilean children and adolescents. A previous study explored the association between unhealthy snacking and academic outcomes in Chilean students from the Santiago Metropolitan Region, using a validated food frequency questionnaire with fifth and ninth graders. That study reported that 56% of students consumed snacks that were high in fat, sugar, salt, and energy and that unhealthy snacking lowered the odds of good academic performance.(37) Another study looked at food preferences among 10- to 13-year-old adolescents in 7 public schools in Chile and found that the snacks most commonly purchased were sweet snacks (35%), juice and ice cream (33%), salty snacks (30%), yogurt (11%), and fruit (7%).(38) Similar to these studies, in our larger sample size with both children and adolescents, snacks tended to be foods and beverages that are energy dense and high in total sugars and saturated fat.

Several studies have assessed snacking behaviors in low- and middle-income countries, including Brazil, Mexico, and China. The percentage of snackers among both age groups in our study (90% or above) was higher than that reported in Mexico (75% among 2- to 5-year-olds, 68% among 6- to 13-year- olds). Similarly, the average number of snacks consumed per day was higher in our study than that reported in Mexico (1.6 snacks per day and 1.2 snacks per day, respectively).(20) Likewise, snacking by adolescents was more prevalent and more frequent in Chile than in Brazil, where 79% of 10- to 18-year- olds reported at least 1 snack per day and an average of 1.6 snacks per day.(19) This difference might be partly explained by the way we defined snacking (self-identified by participants as either colación or picoteo) in comparison to a definition based on the reported time of day, the caloric content of the EO, or the time lapsing between EOs. Snacking patterns in Chile are more like those reported in the United States, where 95% and 92% of children and adolescents, respectively, report at least 1 snacking occasion per day and an average of 3.0 and 2.5 snacks are consumed per day.(17)

One of the main concerns is the quality of the foods and beverages consumed as snacks by our sample. In children the most frequently reported snack items were fruits and vegetables, grain-based desserts (i.e., cookies and other sweet bakery products), dairy foods (i.e., yogurt), dairy beverages, and other sweets and desserts (i.e., chocolates, other candies, and frozen treats). Adolescents most frequently reported grain-based desserts, other sweets and desserts, fruits and vegetables, cereal-based foods, and salty snacks. It is important to note that even though fruits and vegetables rank high in terms of reported frequency as snacks, due to their lower energy density, other foods and beverages considered less healthy provide a greater proportion of the energy per capita from snacks. These food and beverage choices consumed as snacks are similar to those reported as snacks in other countries. In Brazil (19) the top 5 food groups consumed by 10- to 18-year-old snackers were sweets and desserts; sugar-sweetened beverages; fried or baked dough with meat, cheese, or vegetables; sweetened coffee and tea; and fruit. In Mexico fruit, milk and yogurt, salty snacks, candy, cookies, sweetened breads, and atoles contributed to snacking occasions among 2- to 5-year-olds. Similarly, among 6- to 13-year-olds these food groups were important in addition to sandwiches, tortas or filled rolls, and carbonated sodas.(20)

In our study the food and beverage groups consumed as meals could potentially be of a healthier profile than that of snacks. For children meat and meat substitutes, legumes, eggs, and oils and fats (likely used in food preparation) are the top contributors to meals but not to snacks, whereas for adolescents meat and meat substitutes, oils and fats, and dairy beverages were the main contributors to meals but not to snacks. Given these differences in food groups consumed as snacks or meals, the difference in the nutrient profile of both types of EO are somewhat expected. Even though snacks contribute to about a third of the daily energy in both age groups, they contribute more total sugars and slightly less total protein (expressed as a percentage of total intake) compared to that of meals. Snacks were also more energy dense; less protein dense; and more carbohydrate, total sugars, total fat, and saturated fat dense than meals.

Of interest is the apparent shift from snacks that might contribute important nutrients in children to less healthy snacks in adolescents. In our study 40.0% of children consumed fruits and vegetables as snacks, but only 28.7% of adolescents did so; 34.8% of children consumed dairy foods (mostly yogurt), but only 19.8% of adolescents did so; and items high in added sugars and fats (desserts, salty snacks, fast food, and empanadas and sopaipillas) were reported more frequently by adolescents. Specifically, 37.6% of children reported grain-based desserts versus 45.7% of adolescents, 27.5% of children reported other sweets and desserts versus 30.7% of adolescents, 13.4% of children reported salty snacks versus 21.8% of adolescents, and 4.7% of children reported fast food versus 6.3% of adolescents. When considering both snacks and meals in our sample, the shift by age in some food group consumption is even more evident. For example, 25.5% of children reported consuming carbonated beverages, while in adolescents this percentage nearly doubled to 47.2%. Similarly, fast food (12.8% in children, 21.7% in adolescents) and empanadas and sopaipillas (5.6% in children, 14.1% in adolescents) were noticeably more commonly consumed by adolescents than children. Adolescents are more independent in their food selections, and preferences might play a greater role in their decisions. Thus the role of the school food environment in snacking choices should not be overlooked, as it influences the snack foods available to children and adolescents during the day, especially given that it is likely that children have money to purchase these snacks.(38)

Our findings show that a larger percentage of calories reported from snacks are consumed at school (35.5–36.0%) in comparison to the percentage of calories reported from meals consumed at school (13.7–16.3%). This should raise awareness regarding the importance of the availability of healthy snacks at school. In Chile both primary and secondary schools tend to have a kiosko escolar, a small store in the school where foods are made, sold, or both (separate from the school lunch program).(39) As in other Latin American countries, these small food stores have traditionally sold a mix of foods made on-site and packaged foods and until recently had not been subject to regulations regarding the nutrition quality of the items sold.(40) Previous research has evidenced that unhealthful food options were readily available to Chilean students in school kioskos.(41; 42) However, whether and how this has changed in the current policy context is yet to be determined.

For example, the Chilean government recently passed a law regarding food labeling and advertising (approved in 2012 and implemented starting in 2016) (43) that can potentially affect snacking behaviors, particularly among adolescents. The law requires front-of-package (FOP) warning labels for foods and beverages that surpass previously specific levels of energy, sodium, total sugars, and saturated fats. Furthermore, these products are subject to marketing restrictions and cannot be sold in schools.(33) These regulations may affect many of the foods and beverages typically consumed as snacks by children and adolescents.

The FOP labeling regulations are an especially promising way of nudging snacking behaviors. A study in Guatemala seeking to understand which snack foods are most frequently purchased by children and how aspects of food packaging influence their perceptions found that some visual aspects influenced their favorite products and also led some children to incorrectly perceive that foods contained healthy ingredients when they did not.(44) This suggests that the Chilean FOP labeling can potentially influence children and adolescents’ selections of snack foods, but whether and how this will occur is an important question to address, particularly in light of our results.

We acknowledge several limitations in our study. First, we investigated snacking patterns over a 1-day period, which might not be representative of children and adolescents’ usual food consumption, and therefore usual snacking patterns might be different. Second, recall bias is always a possibility in self-reported dietary intake measures, especially when working with younger populations. Despite the different strategies we used (such as a food atlas to probe for portions consumed, and caregivers responding for younger children during interviews), there is a possibility of misreporting by participants. Third, the literature has previously raised the challenges of defining what is considered a snack and the implications of different definitions.(45) As in previous studies, our participants self-identified snacks.(17; 20; 46) For each EO participants reported whether they considered the EO a snack or a meal. However, this measure of snacking might exclude snack foods that are consumed as part of main meals and therefore might not give a complete picture of the population’s consumption of snacks.(45)

Finally, due to our recruitment strategies, the socioeconomic characteristics of our study sample are likely homogenous and not representative of the entire population in Chile. However, it is important to note that 92% of Chilean children and adolescents (1st-8th grade) attend public-funded schools(47), and we therefore believe that our results can be generalizable to a vast majority of this age group.

CONCLUSION

We found that snacking is widespread among Chilean children and adolescents and that it contributes greatly to daily energy intakes. Even though, as others have noted, snacking as a behavior is not necessarily unhealthy,(19) the food categories consumed as snacks in our sample are generally considered high in energy, saturated fat, sodium, and/or total sugars and therefore are potentially targeted by the newly implemented nationwide food regulation, with the exception of the fruits and vegetables frequently consumed as snacks. Future research is needed to understand how these regulations affect snacking behaviors and how snacking in this population is associated with weight gain trajectories through childhood and adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Phil Bardsley and Karen Ritter for their assistance with data management; Natalia Rebolledo and Michael Essman for support with food and beverage grouping; Fernanda Sanchez, Nancy Casas and Macarena Jara for their help in understanding the data collection process in Chile.

Financial Support: Funding for this study came from Bloomberg Philanthropies with additional support from IDRC Grant 108180 (INTA-UNC), CONICYT FONDECYT #1161436, and the NIH National Research Service Award (Global Cardiometabolic Disease Training Grant) #T32 HL129969–01A1.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have conflict of interests of any type with respect to this manuscript.

Ethical Standards Disclosure: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA) at the University of Chile. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardian.

REFERENCES

- 1.Popkin BM (2006) Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 84, 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB (2013) Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9, 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivera JA, Pedraza LS, Martorell R et al. (2014) Introduction to the double burden of undernutrition and excess weight in Latin America. Am J Clin Nutr 100, 1613s–1616s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uauy R, Albala C, Kain J (2001) Obesity trends in Latin America: transiting from under- to overweight. J Nutr 131, 893S–899S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivera JÁ, de Cossío TG, Pedraza LS et al. (2014) Childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Latin America: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2, 321–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corvalán C, Garmendia M, Jones‐Smith J et al. (2017) Nutrition status of children in Latin America. Obes Rev 18, 7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawlor DA, Benfield L, Logue J et al. (2010) Association between general and central adiposity in childhood, and change in these, with cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence: prospective cohort study. Bmj 341, c6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile (2017) Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2016–2017 Primeros Resultados. http://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ENS-2016-17_PRIMEROS-RESULTADOS.pdf (accessed June 2018)

- 9.Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile (2010) Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2009–2010 http://www.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/bcb03d7bc28b64dfe040010165012d23.pdf (accessed August 2017)

- 10.Cediel G, Reyes M, da Costa Louzada ML et al. (2018) Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the Chilean diet (2010). Public Health Nutr 21, 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac J-C et al. (2015) Dietary guidelines to nourish humanity and the planet in the twenty-first century. A blueprint from Brazil. Public Health Nutr 18, 2311–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canella DS, Levy RB, Martins AP et al. (2014) Ultra-processed food products and obesity in Brazilian households (2008–2009). PLoS One 9, e92752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendonca RD, Pimenta AM, Gea A et al. (2016) Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 104, 1433–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendonca RD, Lopes AC, Pimenta AM et al. (2017) Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and the Incidence of Hypertension in a Mediterranean Cohort: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am J Hypertens 30, 358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Departamento de Nutrición, Universidad de Chile (2010) Encuesta Nacional de Consumo Alimentario http://www.minsal.cl/sites/default/files/ENCA-INFORME_FINAL.pdf (accessed August 2017)

- 16.Nishi SK, Jessri M, L’Abbe M (2018) Assessing the Dietary Habits of Canadians by Eating Location and Occasion: Findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2. Nutrients 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunford EK, Popkin BM (2017) 37 year snacking trends for US children 1977–2014. Pediatr Obes 13, 247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunford EK, Popkin BM (2017) Disparities in Snacking Trends in US Adults over a 35 Year Period from 1977 to 2012. Nutrients 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffey KJ, Pereira RA, Popkin BM (2013) Prevalence and energy intake from snacking in Brazil: analysis of the first nationwide individual survey. Eur J Clin Nutr 67, 868–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taillie LS, Afeiche MC, Eldridge AL et al. (2015) Increased Snacking and Eating Occasions Are Associated with Higher Energy Intake among Mexican Children Aged 2–13 Years. J Nutr 145, 2570–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duffey KJ, Rivera JA, Popkin BM (2014) Snacking is prevalent in Mexico. J Nutr 144, 1843–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beckerman JP, Alike Q, Lovin E et al. (2017) The Development and Public Health Implications of Food Preferences in Children. Front Nutr 4, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM (2013) Causes of increased energy intake among children in the U.S., 1977–2010. Am J Prev Med 44, e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berteus Forslund H, Torgerson JS, Sjostrom L et al. (2005) Snacking frequency in relation to energy intake and food choices in obese men and women compared to a reference population. Int J Obes (Lond) 29, 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapelot D (2011) The role of snacking in energy balance: a biobehavioral approach. J Nutr 141, 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson NI, Miller JM, Watts AW et al. (2016) Adolescent snacking behaviors are associated with dietary intake and weight status. J Nutr 146, 1348–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hess JM, Jonnalagadda SS, Slavin JL (2016) What Is a Snack, Why Do We Snack, and How Can We Choose Better Snacks? A Review of the Definitions of Snacking, Motivations to Snack, Contributions to Dietary Intake, and Recommendations for Improvement. Adv Nutr 7, 466–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kain J, Corvalan C, Lera L et al. (2009) Accelerated growth in early life and obesity in preschool Chilean children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17, 1603–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaskins AJ, Pereira A, Quintiliano D et al. (2017) Dairy intake in relation to breast and pubertal development in Chilean girls. Am J Clin Nutr 105, 1166–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cerda R, Barrera C, Arena M et al. (2010) Atlas Fotográfico de Alimentos y Preparaciones Típicas Chilenas Edición Primera ed. Santiago: Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (2016) USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28 https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/ (accessed July 2017)

- 32.Quintiliano D, Jara M (2016) Protocolo Sistema de Clasificación de los Alimentos - CEPOC Santiago: Universidad de Chile. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile (2012) Ley 20606: Sobre composición nutricional de los alimentos y su publicidad https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1041570 (accessed August 2017)

- 34.Corvalan C, Reyes M, Garmendia ML et al. (2018) Structural responses to the obesity and non- communicable diseases epidemic: Update on the Chilean law of food labelling and advertising. Obes Rev [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization (2016) Nutrient Profile Model http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/18621/9789275118733_eng.pdf?sequence=9&isAllowed=y (accessed July 2016)

- 36.StataCorp (2017) Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 vol. 2017 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Correa-Burrows P, Burrows R, Orellana Y et al. (2015) The relationship between unhealthy snacking at school and academic outcomes: a population study in Chilean schoolchildren. Public Health Nutr 18, 2022–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bustos N, Kain J, Leyton B et al. (2010) Snacks usually consumed by children from public schools: motivations for their selection. Rev Chil Nutr 37, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministerio de Salud, Ministerio de Educación, Chile Gd (2016) Guía de Kioskos y Colaciones Saludables https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/GUIA-DE-KIOSCOS-SALUDABLES.pdf (accessed September 2018)

- 40.Fraser B (2013) Latin American countries crack down on junk food. Lancet 382, 385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prochownik K, Vera-Vergara M, Cheskin L (2015) New Regulations for Foods Offered to School Children in Chile: Barriers to Implementation. International Journal of Nutrition 1, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bustos N, Kain J, Leyton Br et al. (2011) Changes in food consumption pattern among Chilean school children after the implementation of a healthy kiosk. Arch Latinoam Nutr 61, 302–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corvalán C, Reyes M, Garmendia ML et al. (2013) Structural responses to the obesity and non- communicable diseases epidemic: the Chilean Law of Food Labeling and Advertising. Obes Rev 14 Suppl 2, 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Letona P, Chacon V, Roberto C et al. (2014) A qualitative study of children’s snack food packaging perceptions and preferences. BMC Public Health 14, 1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hess JM, Slavin JL (2018) The benefits of defining “snacks”. Physiol Behav [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM (2011) Energy density, portion size, and eating occasions: contributions to increased energy intake in the United States, 1977–2006. PLoS Med 8, e1001050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gobierno de Chile, Ministerio de Educación (2017) Estadísticas de la Educación 2016 https://centroestudios.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2017/07/Anuario_2016.pdf (accessed November 2018)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.