Summary paragraph

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), affect several million individuals worldwide. CD and UC are complex diseases and heterogeneous at the clinical, immunological, molecular, genetic, and microbial levels. Extensive study has focused on individual contributing factors. As part of the Integrative Human Microbiome Project (HMP2), 132 subjects were followed for one year each to generate integrated longitudinal molecular profiles of host and microbial activity during disease (up to 24 time points each; in total 2,965 stool, biopsy, and blood specimens). These provide a comprehensive view of the gut microbiome’s functional dysbiosis during IBD activity, showing a characteristic increase in facultative anaerobes at the expense of obligate anaerobes, as well as molecular disruptions in microbial transcription (e.g. among clostridia), metabolite pools (acylcarnitines, bile acids, and short-chain fatty acids), and host serum antibody levels. Disease was also marked by greater temporal variability, with characteristic taxonomic, functional, and biochemical shifts. Finally, integrative analysis identified microbial, biochemical, and host factors central to the dysregulation. The study’s infrastructure resources, results, and data, available through the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi’omics Database (http://ibdmdb.org), provide the most comprehensive description to date of host and microbial activities in IBD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) affect >3.5 million people, with increasing incidence worldwide1. These diseases, the most prevalent forms of which are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are characterized by debilitating and chronic relapsing and remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract (for CD) or the colon (in UC). Extensive study has demonstrated that these conditions result from a complex interplay between host2, 3, microbial4–6, and environmental7 factors. Drivers in the human genome include over 200 risk variants, many of which are responsible for host-microbial interactions3. Common gut microbiome changes in IBD include an increase in facultative anaerobes, including E. coli8, and a decrease in obligately anaerobic short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) producers4. Here, to support a systems-level understanding of the etiology of the IBD gut microbiome that goes beyond previously reported metagenomic profiles, we introduce the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Multi’omics Database (IBDMDB), as part of the Integrative Human Microbiome Project (HMP2).

Results

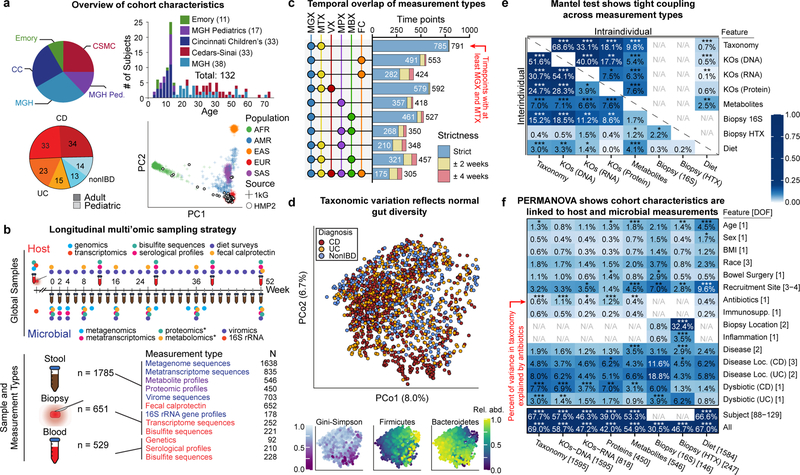

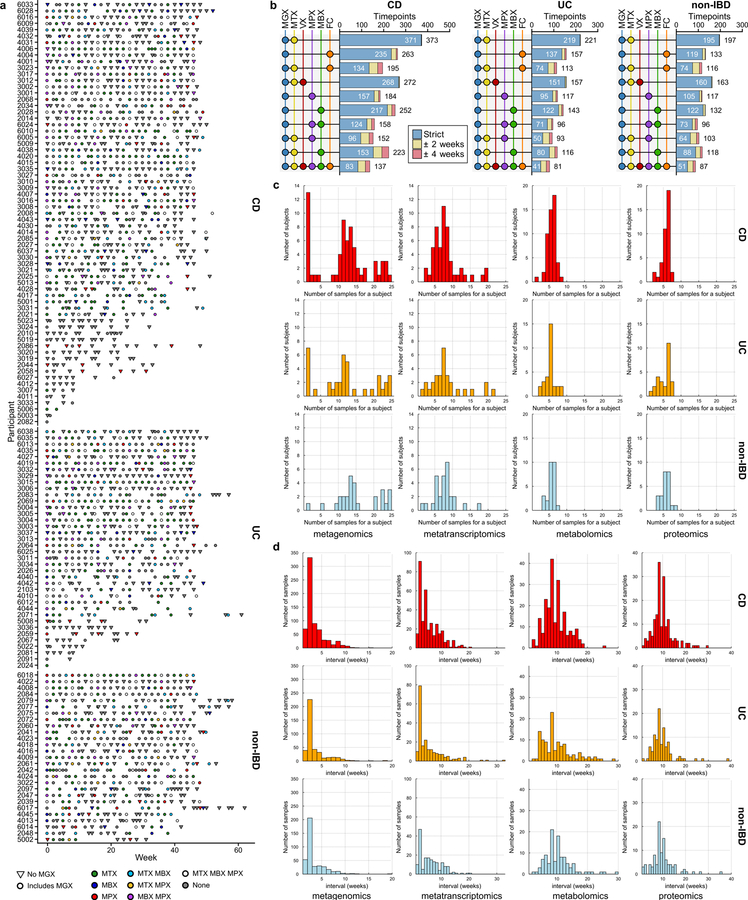

132 participants were recruited from five academic medical centers (three pediatric sub-cohorts: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital [MGH] Pediatrics, and Emory University Hospital, and two adult: MGH and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Fig. 1A, Extended Data Table 1, Methods). We analyzed 651 biopsies (baseline) and 529 blood samples (approximately quarterly) which were collected in clinic and 1,785 stool samples which were collected biweekly using a home shipment protocol for one year (Fig. 1B). The latter yielded primarily microbially-focused profiles: metagenomes (MGX), metatranscriptomes (MTX), proteomes (MPX), metabolomes (MBX), and viromes (VX) at several “global” time points across all subjects (Fig. 1B), as well as denser, more intensive sampling for individuals with more variable disease activity (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1A–D). Multiple measurement types were generated from many individual stool specimens, including 305 samples that contain all stool-derived measurements, and 791 MGX-MTX pairs (Fig. 1C, Extended Data Fig. 1B). Biopsies yielded host-and microbially-targeted human RNA-seq (HTX), epigenetic Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (16S), which are matched with human exome sequencing, serological profiles, and RRBS from blood. All data are available at https://ibdmdb.org/.

Figure 1. Multi’omics of the IBD microbiome in the IBDMDB study.

A) 132 CD, UC, and non-IBD control subjects were followed for one year each across a range of ages from five clinical centers. Principal component analysis (PCA) of SNP profiles shows the resulting IBDMDB cohort is mostly of European ancestry as compared to the 1000 Genomes reference (Methods). B) The study yielded host and microbial data from colon biopsy (baseline), blood (~quarterly), and stool (biweekly), assessing global time points for all subjects and dense time courses for a subset. Raw, non-quality-controlled sample counts are shown. C) Overlap of multi’omic measurements from the same sample (strict) or from near-concordant time points (with up to 2 or 4 weeks’ time difference; Methods). D) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on species-level Bray-Curtis dissimilarity; most variation is driven by a tradeoff between phylum Bacteroidetes vs. Firmicutes. IBD samples (CD in particular) had weakly lower Gini-Simpson alpha diversity (Wald test p-values 0.26 and 0.014 for UC and CD vs non-IBD, respectively). E) Mantel tests quantifying variance explained (square of Mantel statistic) between measurement type pairs, with differences across subjects (inter-individual) or within-subject over time (intra-individual; Methods). Sample sizes in (F). F) PERMANOVA shows that inter-individual variation is largest for all measurement types, with even relatively large effects (e.g. antibiotics or IBD phenotype) capturing less variation (Methods). Stratified tests (CD/UC) consider only samples within the indicated phenotype (note that sample counts decrease for these, resulting in larger expected covariation by chance). Stars show FDR-corrected statistical significance (* FDR p≤0.05, ** ≤0.01, *** ≤0.001). Variance is estimated for each feature independently (Methods). “All” refers to a model with all metadata. Total n for each measurement type is shown in [], distributed across up to 132 subjects (Extended Data Fig. 1A, Methods).

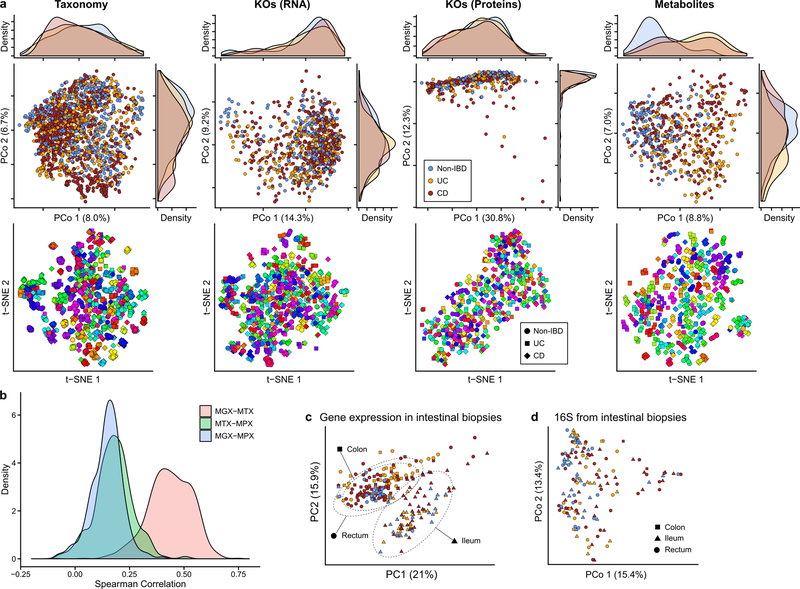

Multi’omic IBD gut microbiome perturbations

Consistent with prior studies4, 5, although IBD subsets (CD in particular) contributed to the second axis of taxonomy-based principal coordinates (Fig. 1D, Extended Data Fig. 2A), inter-individual variation accounted for the majority of variance for all measurement types5, 9, 10 (Fig. 1E, F, Extended Data Fig. 2A). Even relatively large effects, such as disease status, physiological, and technical factors, explained a smaller proportion of variation (Fig. 1F), which as consistent across measurement types although these captured distinct aspects of IBD dysbiosis (below).

Most measurement types captured correlated changes among and within subjects, cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Fig. 1E). Functional profiles, measured from MGX, MTX, and MPX, were the most tightly coupled (Fig. 1E), although some individual feature-wise correlations were weak (Spearman MGX-MTX 0.44±0.10 [mean ± standard deviation], MGX-MPX 0.14±0.083, and MTX-MPX 0.18±0.096, Extended Data Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, characterized enzymes tended to be only weakly correlated with their known substrates or products (Supplementary Fig. S1). Our dietary characterization, though from a very broad-level food frequency questionnaire, provides a first characterization of longitudinal diet-microbiome coupling in a substantial population over many months, and accounted for a small but significant 3% (FDR p = 7.4 × 10−4) of taxonomic variation between subjects, and 0.7% (FDR p = 4.3 × 10−4) of variation longitudinally.

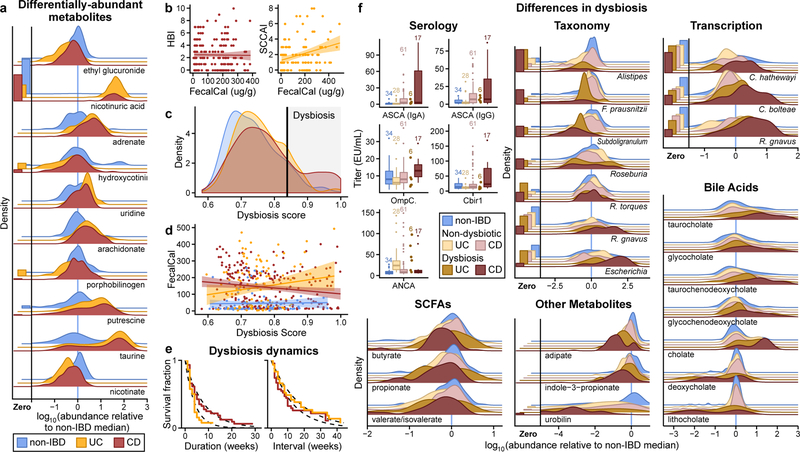

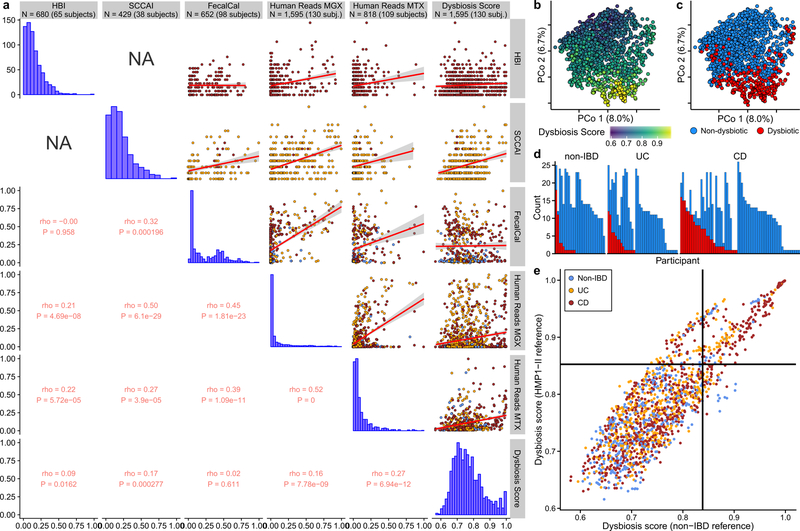

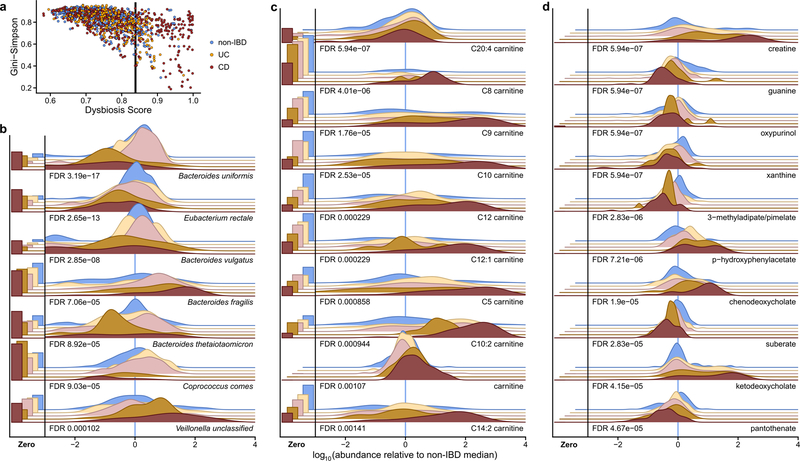

Simple cross-sectional differences among IBD and non-IBD phenotypes (Supplementary Tables S1–14) were most apparent in the metabolome (Fig. 1F, Fig. 2A, Extended Data 2A, 2C–D, Methods). Overall, metabolite pools were less diverse in IBD, paralleling previous observations for microbial diversity (Supplementary Table S2), possibly caused by poor absorption, greater water/blood content, and shorter transit times in IBD11. The smaller number of more-abundant compounds included polyunsaturated fatty acids such as adrenate and arachidonate. Pantothenate and nicotinate (vitamin B5 and B3, respectively) were particularly depleted in the IBD gut, notable since these are not typically part of the vitamin B deficiencies observed in the serum of IBD patients12, although low nicotinate levels have been detected during active CD13. Both vitamins are required to produce cofactors used in lipid metabolism14, and nicotinate plays anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic roles in the gut15. Interestingly, nicotinuric acid, a metabolite of nicotinate16, was found almost exclusively in the stool of IBD cases. Fecal calprotectin (FC) and the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI), two measures of disease severity in CD, did not show significant agreement, while the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index17 (SCCAI) in UC did weakly correlate with FC (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, and stool metabolomic profiles are disrupted during IBD activity.

A) Relative abundance distributions for 10 of the most cross-sectionally significantly differentially abundant metabolites in IBD, as a ratio to the median relative abundance in non-IBD (Wald test; all FDR p < 0.003; Methods; full results in Supplementary Tables S1–14). Fraction of samples below detection limit on left (Methods). N=546 samples from 106 subjects. B) Relationships between two different measures of disease activity: patient-reported (Harvey-Bradshaw Index, HBI, in CD N=680 samples from 65 subjects; Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index, SCCAI, in UC N=429 samples from 38 subjects) and host molecular (fecal calprotectin43 N=652 samples from 98 subjects). Linear regression shown with 95% confidence bound. C) Distribution of microbial dysbiosis scores as a measure of disease activity (median Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between a sample and non-IBD samples; Methods) and D) its relationship with calprotectin (N=652 samples from 98 subjects). Linear regression with 95% confidence. E) Kaplan-Meier curves for the distributions of the durations of (left) and intervals between (right) dysbiotic episodes for UC and CD subjects. Both are approximately exponential (fits in dashed lines), with a means of 4.1 and 17.2 weeks for UC, and 7.8 and 12.8 weeks for CD (Methods). F) Relative abundance distributions of significantly different metagenomic species (N=1,595 samples from 130 subjects), metabolites (N=546 samples from 106 subjects), and microbial transcribers (N=818 samples from 106 subjects) in dysbiotic samples compared to non-dysbiotic samples from the same disease group (Wald test; all FDR p < 0.05; full results in Supplementary Tables S15–28). Also shown are antibody titers for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies (ASCA, IgG or IgA), anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1 antibodies (N=146 from 61 subjects). Boxplots show median and lower/upper quartiles; whiskers show inner fences; sample sizes above boxes.

Notably, no metagenomic species were significantly different between IBD and non-IBD phenotypes after correction for multiple hypothesis testing (Supplementary Table S1), in contrast with prior work4, 5, 18. We hypothesized this was due to the differentiation of IBD patients into two subsets, one with relatively inactive disease (either due to remission or recent onset) and the other with greater activity. This differentiation has been observed in several IBD cohorts5, 18, though is more pronounced here since samples are not specifically from subjects selected for active disease. We thus classified samples with taxonomic compositions highly unlike those from non-IBD samples as “dysbiotic” (Fig. 2C, see definition and discussion in Methods, Extended Data Fig. 3A–E). Dysbiotic excursions in this cohort did not correspond with disease location (e.g. ileal CD; F-test p=0.11, Methods), and occurred longitudinally within subjects; they were weakly correlated with patient-reported and molecular measures of disease activity (Fig. 2D, Extended Data Fig. 3A). In total, 272 dysbiotic samples occurred in 78 full periods of dysbiosis and 9 censored periods (i.e. subjects which were dysbiotic at the end of the time series, Methods), or 17.1% of all samples (n=178 [24.3%] in CD and n=51 [11.6%] in UC). The durations of and times between dysbiotic periods were both approximately exponential, suggesting that transitions are triggered, at least in part, by events with constant probability over time (i.e. potentially stochastic, Fig. 2E).

Using the resulting definition, dysbiosis corresponded with a larger fraction of variation in all measurement types than did overall IBD phenotype (see Fig. 1F; Supplementary Tables S15–28), likely reflecting a clearer delineation between active and less active disease states within extremely heterogeneous subjects over time. Though it is unclear which aspects of dysbiosis are cause or consequence in IBD, characterizing these changes will lead to a greater understanding of microbial dynamics in disease. As in previous cross-sectional studies of established disease4, differences between dysbiotic and non-dysbiotic samples from CD subjects were more pronounced than in UC (see Fig. 1F). Notably, dysbiosis also distinguished between independent host measures, such as individuals with high and low ASCA, ANCA, OmpC (outer membrane protein C), and Cbir1 (anti-flagellin) antibody titers in serological profiles (Fig. 2F; Fisher’s combined probability test p-value 0.00044 from Wilcoxon tests between dysbiotic and non-dysbiotic CD). Dysbiosis was not significantly associated with demographics or medication (logistic regression with subject as random effect, all FDR p > 0.05). Dysbiosis recapitulated a known decrease in alpha diversity in active disease, but also identified numerous communities with normal complexity as dysbiotic (Extended Data Fig. 4A). Taxonomic perturbations during dysbiosis, strikingly, mirrored those previously observed cross-sectionally in IBD6, such as the depletion of obligate anaerobes including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia hominis in CD and the enrichment of facultative anaerobes such as Escherichia coli (Fig. 2F; Extended Data Fig. 4B). Ruminococcus torques and R. gnavus, two prominent species in IBD19, were also differentially-abundant in dysbiotic CD and UC, respectively (FDR p=0.041 and 0.0087). A smaller subset of species also increased significantly in transcriptional activity (mean total transcript relative abundance relative to genomic abundance; Methods) in addition to abundance differences, including Clostridium hathewayi, C. bolteae, and R. gnavus (Fig. 2F). All had significantly increased expression during dysbiosis (all FDR p<0.07), and thus their roles in IBD may be more pronounced than suggested solely by their genomic abundance differences.

In the metabolome, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) were generally reduced in dysbiosis (Fig. 2F). The reduction in butyrate in particular is consistent with the previously-observed depletion of butyrate producers6 such as F. prausnitzii and R. hominis, also observed here (Fig. 2F). We also detected enrichments in the primary bile acids cholate and its glycine and taurine conjugates (glycocholate q=5.2 × 10−5, taurocholate q=1.3 × 10−5) in dysbiotic CD. Similarly, glycochenodeoxycholate q=1.1 × 10−4 was also enriched. In contrast, secondary bile acids lithocholate and deoxycholate (q=5 × 10−7 and 1.8 × 10−4, respectively) were reduced in dysbiosis, suggesting that secondary bile-acid producing bacteria are depleted in IBD-related dysbiosis, or that transit time through the colon is too short for them to be metabolized20, 21. These highly significant metabolomic differences during microbial dysbioses, which were in turn concordant with changes expected during disease, provide further evidence that the dysbiosis measure is specifically relevant in IBD. We also observed several novel biochemical differences during dysbiosis, such as large changes in acylcarnitines. Many acylcarnitines were significantly enriched in dysbiosis (Extended Data Fig. 4C), while base metabolites were typically reduced (Fig. 2F, Extended Data Fig. 4D). Of note, however, arachidonoyl carnitine (C20:4 carnitine) was reduced while free arachidonate, a precursor of prostaglandins involved in inflammation, was increased (see Fig. 2A). Like bile acids, carnitines are microbially-modified compounds can have competing phenotypic effects depending on the precise modifications: L-carnitine, for example, tends to be anti-inflammatory, while fatty acid-conjugated carnitine does not act uniformly on gut inflammation22. These opposing changes in biochemically related metabolites further suggest that these differences do not stem simply from the wholesale dilution of stool. Numerous other metabolites were also significantly altered in dysbiotic IBD (117 of 548 tested known metabolites with FDR p<0.05; Extended Data Fig. 4D, Supplementary Table S16), showing a large-scale dysregulation of metabolite pools in tandem with host-and microbiome-specific taxonomic and molecular features (Fig. 2F). Finally, though we found only a single poorly-characterized bacteriophage to be differentially-prevalent in both IBD and in dysbiosis (interestingly with reduced prevalence in IBD, Supplementary Tables S3, S17), we note that several subjects were observed to have a spike in viral load prior to a dysbiotic period (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Decreased IBD gut microbiome stability

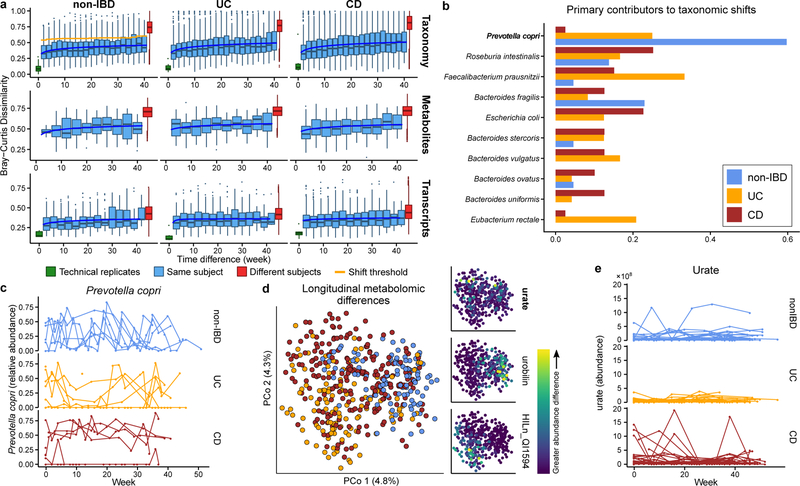

The IBDMDB’s dense time series for stool-derived multi’omics from many subjects enabled in-depth longitudinal analysis integrating multiple measurements of the microbiome. Each subject’s microbiome tended to change more over time for metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, and metabolomic profiles (Fig. 3A; F-test power law fit p-values < 10−24; Methods). These changes were most pronounced for CD and UC subjects’ taxonomic profiles (F-test difference in power law fits p-values < 10−9), where a single subject’s microbiome may have almost no species in common with itself at an earlier time point (dissimilarity of 1, Fig. 3A), consistent with previous observations9. Transcripts summarized within species (Extended Data Fig. 5A) showed similar trends (all F-test p-values < 8 × 10−4) to metagenomic species abundances. Meanwhile, gene family transcripts (KOs), metabolites (Fig. 3A), and proteins (KOs, Extended Data Fig. 5A) varied much more rapidly, with essentially as much change after ~two weeks as over longer time periods (increasing trends less-or non-significant: non-IBD, UC, CD F-test p-values 0.0006, 0.001, and 0.04, respectively for transcripts; 0.02, 0.06, and 0.003 for metabolites; and 0.5, 0.15, and 0.06 for proteomics). This indicates that these features all vary rapidly in both IBD and control subjects’ guts and lack additional, more extreme excursions during disease.

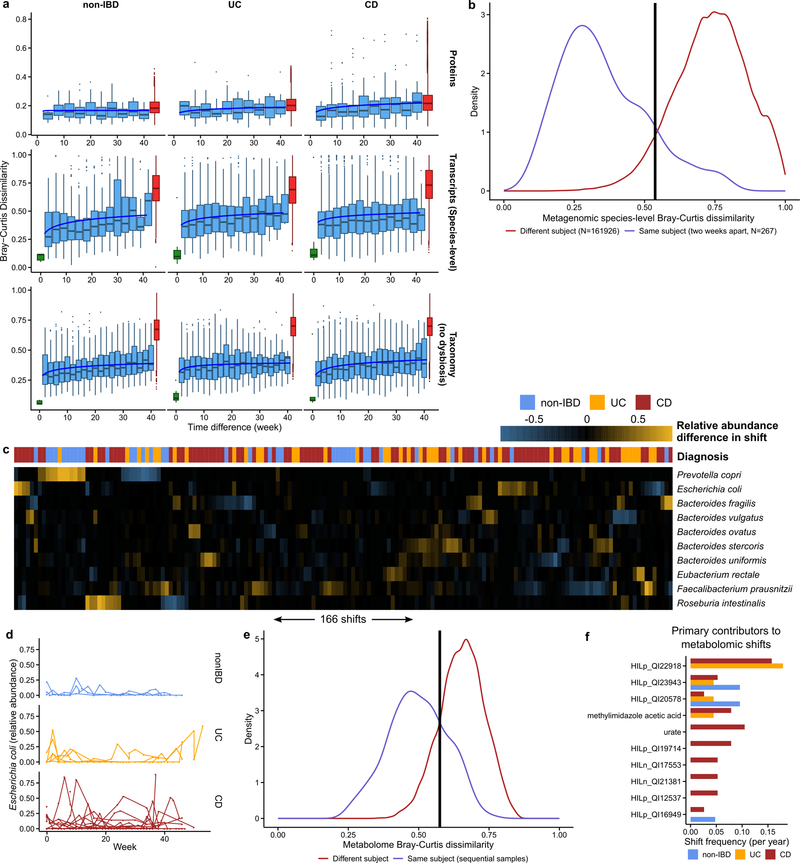

Figure 3. Temporal shifts in the microbiome are more frequent and more extreme in IBD.

A) Bray-Curtis dissimilarities within subject as a function of intervening time difference, as compared to different people or technical replicates; calculated for metagenomic taxonomic profiles (species; N=1,595 samples from 130 subjects), metabolomics (N=546 samples from 106 subjects), and functional profiles (KO30 gene families; N=818 samples from 106 subjects). Boxplots show median and lower/upper quartiles; whiskers show inner fences. Least-squares power-law fits in blue, thresholds for microbiome shifts in orange (Methods). Proteomics and species-level transcripts in Extended Data Fig. 5A. Within-subject changes are significantly more extreme in UC (F-test p-value 3.9 × 10−10) and CD (F-test 1.2 × 10−18) for taxonomic profiles and transcripts (latter F-test p-values 0.00016 and 1.7 × 10−5), with mixed differences for metabolites (F-test p-values 0.012 and 0.23). Technical replicates shown (when possible) at 0 weeks. B) Shift frequencies for the top 10 species with greatest change during shifts, ranked by number of shifts as primary contributor, stratified by disease phenotype(s) (full table Supplementary Table S29). C) Prevotella copri is of interest in arthritis23 and international populations44, and it uniquely retained stable abundances in CD but bloom-relaxation dynamics in controls (Two-tail Wilcoxon test of absolute differences between consecutive time points p=4.2 × 10−6 between non-IBD and UC, and 1.1 × 10−4 between non-IBD and CD). Plot shows 22 subjects with at least one time point with >10% differential abundance (N=267 samples). D) Ordination of temporally adjacent samples within individual, based on metabolomics (Bray-Curtis principal coordinates on normalized absolute abundance differences). Disease groups separate significantly (N=440 sample pairs from 106 subjects; PERMANOVA R2 = 2.8%, p<10−4). Urobilin, urate, and an unidentified untargeted feature that segregate with disease groups in the PCoA are shown (right); HILn_QI1594 (HILIC-neg method m/z 152.0354, RT: 4.16 min). E) As in (C), but for urate (Two-tail Wilcoxon test p=0.0012 non-IBD-UC, and 0.044 non-IBD-CD; N=546 samples from 106 subjects).

We further characterized large-scale temporal differences by searching for “shifts” in the microbiome between consecutive time points, defined as Bray-Curtis dissimilarities more similar to those between different people than within person (Fig. 3A, Extended Data Fig. 5B, Methods). First considering only metagenomic taxonomic profiles, 166 such shifts were observed, with 39 in non-IBD (of 382 total possible), 44 in UC (of 381), and 83 in CD (of 650) (Supplementary Table S29). Due to differences in total observation times, the rate of shifts was only marginally higher in CD and UC compared to non-IBD (2.09 and 1.83 shifts/year versus 1.79 in non-IBD), and these were generally confined to a subpopulation of dysbiotic individuals (Fig. 3A). However, the species with the greatest changes in relative abundance differed dramatically (Fig. 3B). Shifts in non-IBD subjects primarily occurred in individuals with high abundances of Prevotella copri, which underwent repeated expansion and relaxation cycles over the course of weeks to months (Fig. 3C). This organism is of particular interest due to its behavior as a population-scale outgroup and enrichment during new-onset rheumatoid arthritis23. The lack of shifts due to P. copri in IBD subjects was not due to an absence of P. copri in these individuals or an overabundance in non-IBD subjects (6 of 27 non-IBD subjects had at least one time point with >10% P. copri, consistent with healthy populations10, 24). Instead, the relative abundances that were present remained more stable in the IBD population (Fig. 3C). Taxonomic shifts in IBD subjects mirrored earlier observations of relative reductions of obligate anaerobes and overgrowths of facultative anaerobes (Fig. 3B, Extended Data Fig. 5C), and frequently corresponded with entry into/exit from dysbiosis (28 and 23 shifts marked entries and exits in IBD, respectively, accounting for 40% of shifts in IBD). E. coli in particular contributed to a large number of shifts in IBD, though there was no clear pattern in which species it trades abundance with (Extended Data Fig. 5C–D).

Defining shifts in a similar manner for metabolomics profiles (Extended Data Fig. 5E), we find approximately half the overall rate of shifts as in the metagenome (1.05 shifts/year in non-IBD subjects, 0.99 shifts/year in UC and 1.36 shifts/year in CD), though this is strongly affected by the availability of fewer metabolomics samples (Extended Data Fig. 5E). Examining differences in metabolite profiles between adjacent samples for the same subject, we find a significant separation by diagnosis (Fig. 3D; PERMANOVA p<10−4). These differences were largely driven by unknown compounds, emphasizing the need for further compound annotation efforts and follow up to determine their significance in IBD. Features with the greatest differences included urobilin (with larger differences in non-IBD), urate largely in CD, and a feature with m/z of 152.0354 and retention time (RT) of 4.16 min (potentially the formic acid adduct of pyridinaldehyde), accounting for differences largely specific to UC. The primary contributors to shifts were largely unidentified compounds (Extended Data Fig. 5F, Supplementary Table S30). HILp_QI22918, an unknown feature with m/z of 648.43067 and RT of 5.03 min, contributed the most (10) shifts exclusively in IBD subjects. Among known compounds, methylimidazole acetic acid and urate were the primary contributors to the most shifts (4 shifts each; Fig. 3E).

Microbiome-associated host factors

When incorporating host molecular measurements, primarily from intestinal biopsies taken colonoscopically at baseline, into analysis of the IBD microbiome, the main influences on population variability were strikingly different from those affecting the microbiota alone. In particular, tissue location is a major driver of intestinal epithelial gene expression (Extended Data Fig. 2C) even in the face of microbial variation25 (Extended Data Fig. 2D). Microbiome and phenotypic association analyses were thus performed independently for each standardized biopsy location (Methods).

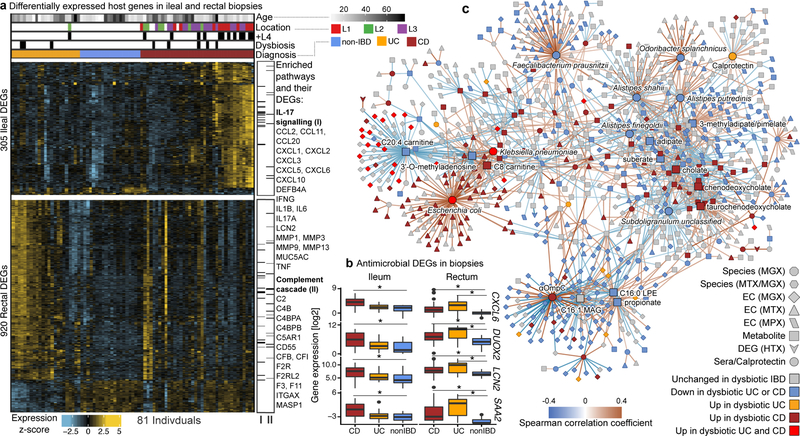

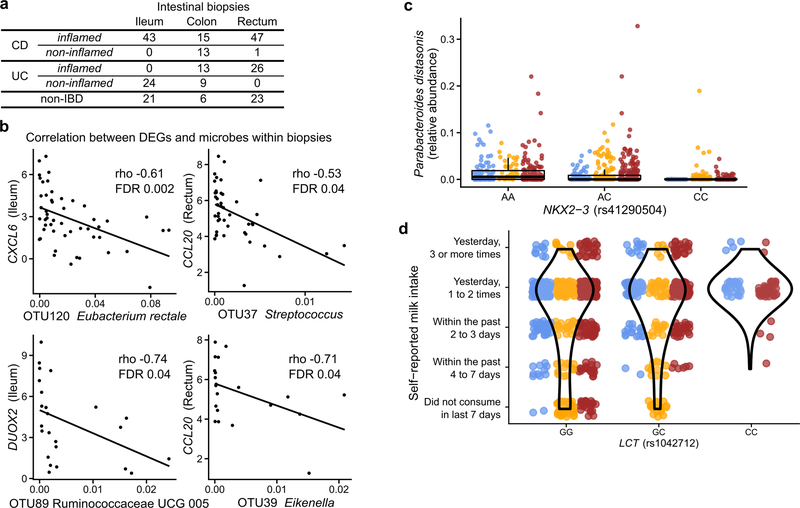

We identified genes that were significantly differentially expressed (DEGs) in patient biopsies taken in inflamed locations of the ileum (CD subjects) and rectum (CD and UC subjects) compared to non-IBD controls (Extended Data Fig. 6A). This targeted 305 ileal and 920 rectal genes, primarily overexpressed, for further analysis (together representing 1,008 unique genes, negative binomial model FDR p<0.05 and fold-change > 1.5. Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table S31). These included genes that can affect commensal microbes directly, such as the antimicrobial CXCL6 (a cell membrane disruptor26) and SAA2 (a Gram-negative growth inhibitor27), as well as indirect microbial modulators such as DUOX2 (reactive oxygen species production28) and LCN2 (iron starvation through sequestration29, Fig. 4B). Enrichment analysis testing for overrepresentation of KEGG30 pathways among DEGs also confirmed strong representation of immune related pathways (one-sided hypergeometric test, FDR p<0.05). Particularly, the IL-17 signaling pathway, whose components have been previously reported in gene expression studies of ileal biopsies of CD patients31, 32, was enriched in up-regulated DEGs in both ileum and rectum (FDR p=2.8 × 10−14, Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table S32). Among up-regulated DEGs in rectal biopsies of UC patients, we found further enrichment of the complement cascade (FDR p=4.4 × 10−10), a component of innate immunity33 which has been implicated in IBD in early studies25, 34, 35.

Figure 4. Colonic epithelial molecular processes perturbed during IBD and in tandem with multi’omic host-microbial interactions.

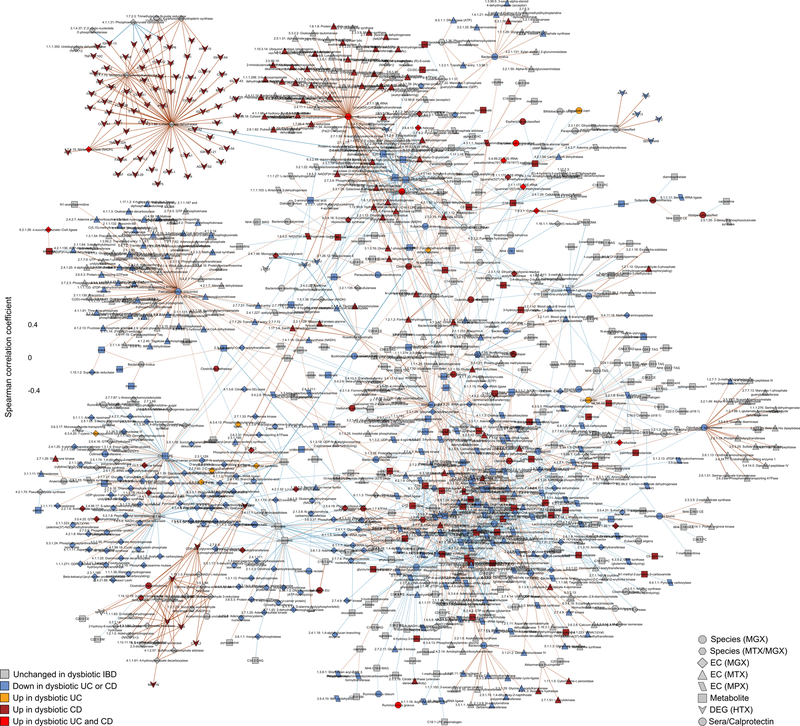

A) Differentially expressed human genes (DEGs) (negative binomial FDR p<0.05, min. fold change 1.5; Supplementary Table S31) from 81 subjects with paired ileal and rectal biopsies. Ordering by diagnosis, clustering within diagnosis. IL-17 signaling (I) showed strongest enrichment in ileal DEGs (FDR p=8.2 × 10−12)31, while the complement cascade (II)45 was enriched in rectal DEGs of UC patients (FDR p=5.2 × 10−8; KEGG30 gene sets, Supplementary Table S32). Example DEGs shown with I and II. B) Expression of four genes involved in host-microbial interactions26–29. Inflamed biopsy samples are shown for CD in ileum (left column, N=20, 23, 39 independent samples for non-IBD, UC, CD respectively); for CD and UC in rectum (right column; N=22, 25, 41 independent samples for non-IBD, UC, CD); non-IBD samples were non-inflamed. Stars indicate significant differential expression compared to non-IBD (Fisher’s exact, FDR p<0.05; p-values in Supplementary Table S31). Boxplots show median and lower/upper quartiles; whiskers inner fences. C) Significant associations among 10 different aspects of host-microbiome interactions: metagenomic species, species-level transcription ratios, functional profiles captured as EC gene families (MGX, MTX and MPX), metabolites, host transcription (rectum and ileum), serology, and calprotectin (sample counts in Fig. 1B–C). Network shows top 300 significant correlations (FDR p<0.05) between each pair of measurement types (for serology, FDR p<0.25). Nodes colored by the disease group they are “high” in, edges by sign and strength of association. Spearman correlations use residuals of a mixed-effects model with subjects as random effects (or a simple linear model when only baseline samples were used, i.e. biopsies) after covariate adjustment (Methods). Time points approximately matched with maximum separation 4 weeks (Methods). Singletons pruned for visualization (Extended Data Fig. 8). Hubs (nodes with ≥20 connections) emphasized.

To identify components of the microbiome most associated with these changes, we tested for transcripts covarying with microbe relative abundance measured directly from the same specimens using 16S amplicon sequencing. We identified 31 and 106 significant gene-OTU pairs in the ileum and rectum, respectively, with no overlap between the two sites, consistent with the different overall gene expression patterns that separate them (partial Spearman correlation FDR p<0.05, Methods, Extended Data Fig. 6B, Supplementary Table S33). Genes involved included known IBD-associated host-microbial interaction factors such as DUOX2 and its maturation factor DUOXA2 that produce reactive oxygen species31, 36, both negatively associated with abundance of Ruminococcaceae UCG 005 (OTU 89) in the ileum. Expression of several chemokines, some of which have reported antimicrobial properties37 (CXCL6, CCL20), were negatively correlated with the relative abundance of Eubacterium rectale (OTU 120) in the ileum, and Streptococcus (OTU 37) and Eikenella (OTU 39) in the rectum, suggesting that these species are the most susceptible to the activity of these chemokines. Finally, while this cohort was not designed for genetic association discovery (Supplementary Discussion, Extended Data Fig. 6C–D, Supplementary Table S34), we do also provide exome sequencing of 92 subjects such that these results may be integrated with larger populations in the future.

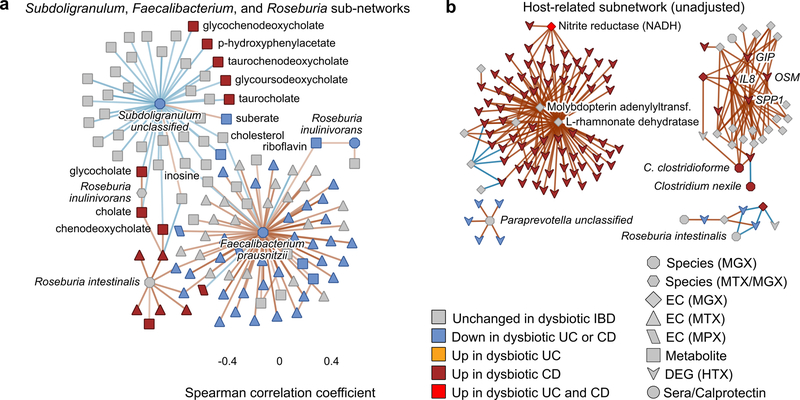

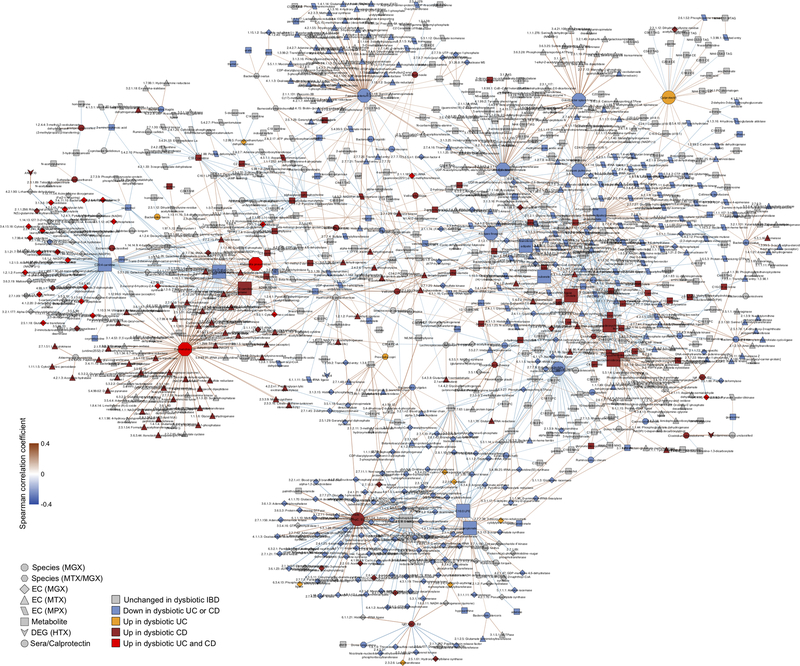

Dynamic, multi’omic microbiome interactions

We next searched for putative host and microbial molecular interactions underlying disease activity in IBD by constructing a large-scale cross-measurement type association network incorporating 10 different microbiome measurements: metagenomic species, species-level transcription ratios, functional profiles captured as Enzyme Commission (EC) gene families (MGX, MTX and MPX), metabolites, host transcription (rectum and ileum separately), serology, and fecal calprotectin. To identify co-variation between components of the microbiome above and beyond those linked strictly to inflammation and disease state, each measurement type was first residualized using the same mixed-effects model (or linear model when appropriate) used to determine differential abundance (“adjusted” network; Methods). This residualization utilizes the longitudinal measurements to minimize any inter-individual variation (including IBD status), as well as dysbiotic excursions as drivers of the detected associations, and thus highlights associations that occur within-person over time. The resulting network contained 53,161 total significant edges (FDR p<0.05) and 2,916 nodes spanning features from all measurement types (Supplementary Table S35). A filtered subnetwork was then constructed for visualization from the top 300 edges (by p-value) per measurement type in which at least one connected node was dysbiosis-associated (Fig. 4C).

Representatives from the five stool-derived measurements occurred as hubs (defined as nodes with ≥20 connections) in this network, all of which were identified as differentially abundant in dysbiosis. Particularly connected taxonomic features (from metagenomes and metatranscriptomes) included the abundances of F. prasunitzii and unclassified clades related to Subdoligranulum38, which are closely phylogenetically related, although the only molecular features common to both organisms were covariation with the abundances of cholesterol and inosine (Extended Data Fig. 7A). F. prausnitzii accounted for some of the strongest associations overall, including the expression of numerous down-regulated ECs in dysbiosis. On the other hand, E. coli (and to lesser extent Haemophilus parainfluenzae) accounted for a large fraction of up-regulated ECs. Members of the Roseburia genus were also associated, metatranscriptionally as well as metagenomically, with both the bile acids and a number of acylcarnitines, suggesting that Roseburia (together with Subdoligranulum) play an integral role in the carnitine and bile acid dysregulation observed in IBD.

Acylcarnitines and bile acids as overall chemical classes featured prominently in the network, related in part to their changes during dysbiosis. Acylcarnitines were associated with numerous dysbiosis-associated species including R. hominis (9 acylcarnitines, FDR p < 0.05; Supplementary Table S35), Klebsiella pneumoniae (3), and H. parainfluenzae (3), as well as expression of C. boltae (3), suggesting that multiple scales of regulation are involved—long-term growth-based and short-term transcriptional. Particularly notable biochemical hubs in the network included C8 carnitine, another acylcarnitine significantly increased in dysbiotic CD, cholate, chenodeoxycholate, and taurochenodeoxycholate, together accounting for 107 edges (6%; Fig. 4C). Other prominent metabolite associations included several long-chain lipid hubs and the SCFA propionate; antibodies against OmpC were strongly associated with these, as well as the metagenomic abundances of the numerous ECs involved in the system’s biosynthesis or as interactors. Calprotectin, as the sole feature in its own measurement type, was weakly associated with a number of metabolites that were not differentially abundant in dysbiosis, as well as with the metagenomic abundance of several dysbiosis-associated ECs. Three host genes appear in this high-significance subnetwork: the ileal expression of GIP, NXPE4, and ANXA10. Expression of RNA polymerase was also a prominent node in the network, though not a hub, up-regulated in dysbiosis (Extended Data Fig. 8). This essential enzyme class’s regulation is growth rate-dependent39, suggesting that microbial communities as a whole are more often in higher growth conditions in dysbiotic IBD.

Finally, we also identified associations among features in the microbiome that did take dysbiosis into account, resulting in a second network using the same methodology but without adjusting for dysbiosis (“unadjusted”; Supplementary Discussion, Extended Data Figs. 7B and 9, Supplementary Table S36). Together, these networks contextualize the multiple different types of microbiome disruptions observed in IBD, with associations among many different molecular feature types representing potential targets for follow-up studies on the mechanisms underlying IBD and gastrointestinal inflammation.

Conclusions

As part of the HMP2, we have developed the IBDMDB, one of the first integrated studies of multiple molecular features of the gut microbiome implicated in IBD dynamics. While overall population structure was comparable among measurements of the microbiome—metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, metabolomic, and others—each measurement identified complementary molecular components of longitudinal dysbioses in CD and UC. Some, such as taxonomic shifts in favor of aerotolerant, pro-inflammatory clades, have been captured by previous studies; others, such as greater gene expression by clostridia during disease, were only able to be newly discovered using other measurements (i.e. metatranscriptomes). Temporal stability of multiple microbiome measurements likewise differed across IBD phenotypes and disease activity, with distinct impacts on molecular components of the microbiome (including an unexpected stability of the relative abundance of P. copri in diseased individuals). The study provides a complete catalog of new relationships between multi’omic features identified as potentially central during IBD, in addition to data, protocols, and relevant bioinformatic approaches to enable future research.

By leveraging a multi’omic view on the microbiome, our results single out a number of new host and microbial features for follow-up characterization. An unclassified Subdoligranulum species, recently shown to form a complex of new species-level clades38, was both drastically reduced in IBD and central to the functional network, associating with a wide range of IBD-linked metabolites both identifiable (e.g. bile acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids) and unidentifiable. The clade likely contains at least seven species closely related to the Subdoligranulum, Gemmiger, and Faecalibacterium genera, typically butyrate-producers considered to be beneficial particularly in IBD40. Therefore, the isolation and characterization of additional species—particularly in tandem with these associated metabolites—is likely to reveal its physiological and immunological interactions and the consequences of its depletion in IBD. More generally, strain-level profiling of implicated microbes remains to be carried out, particularly in direct association with host epithelium and corresponding molecular changes. This is feasible with existing data from this study, and will serve to pinpoint the specific organisms responsible for IBD-associated accumulation of primary unconjugated bile acids and depletion of secondary bile acids41. Only very few, low-abundance species are currently known to be capable of secondary bile acid metabolism42, and thus expanding the range of strains known to carry appropriate metabolic cassettes will indicate potential new targets for therapeutic restoration. Beyond short-chain fatty acids and bile acids, the large-scale acylcarnitine dysbiosis observed here may also provide a promising new target for IBD, particularly after determining whether this large-scale shift in metabolite pools is host or microbially-driven.

We stress that it has not yet been determined whether these multi’omic features of the microbiome are predictive of disease events before their occurrence, nor have the disease-relevant time scales of distinct molecular events been identified (e.g. static host genetics, relatively slow epigenetics or microbial growth, rapid host and microbial transcriptional changes). It may also be fruitful to seek out the earliest departures from a subject-specific baseline state that, while themselves still “eubiotic,” may predict the subsequent onset of dysbiosis or disease symptoms. Some such characterization may be possible in data from this study, although other causal analysis may be better carried out at finer-grained time scales or using interventional study designs. It will be most important to take these molecular results back to the clinic, in the form of better predictive biomarkers of IBD progression and outcome, and as a set of new host-microbial interaction targets for which treatments to ameliorate the disease may be developed.

Methods

Recruitment and specimen collection

Recruitment

Five medical centers participated in the IBDMDB: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Emory University Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital for Children, and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Patients were approached for potential recruitment upon presentation for routine age-related colorectal cancer screening, work up of other GI symptoms, or suspected IBD, either with positive imaging (e.g. colonic wall thickening or ileal inflammation) or symptoms of chronic diarrhea or rectal bleeding. Subjects could not have had a prior screening or diagnostic colonoscopy. Potential subjects were excluded if they were unable or did not consent to provide tissue, blood, or stool, were pregnant, had a known bleeding disorder or an acute gastrointestinal infection, were actively being treated for a malignancy with chemotherapy, were diagnosed with indeterminate colitis, or had a prior, major gastrointestinal surgery such as an ileal/colonic diversion or j-pouch. Upon enrollment, an initial colonoscopy was performed to determine study strata. Subjects not diagnosed with IBD based on endoscopic and histopathologic findings were classified as “non-IBD” controls, including the aforementioned healthy individuals presenting for routine screening, and those with more benign or non-specific symptoms. This creates a control group that, while not completely “healthy”, differs from the IBD cohorts specifically by clinical IBD status. Differences observed between these groups are therefore more likely to constitute differences specific to IBD, and not differences attributable to general GI distress. In total, 132 subjects took part in the study (Extended Data Table 1).

Regulatory Compliance

The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Boards at each sampling site: overall Partners Data Coordination (IRB #2013P002215); MGH Adult cohort (IRB #2004P001067); MGH Pediatrics (IRB #2014P001115); Emory (IRB #IRB00071468); Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (2013–7586); and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (3358/CR00011696). All study participants gave their written informed consent before sampling. Each IRB has a federal wide assurance and follows the regulations established at 45 CFR Part 46. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and the requirements of applicable federal regulations.

Specimen collection and storage

Specimens for research (biopsies, blood draws, and stool samples) were collected during the screening colonoscopy, at up to 5 quarterly follow-up visits at the clinic (termed ‘baseline’, visit 2, etc, occurring at months 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12), and biweekly by mail.

Biopsies

Biopsies were primarily gathered during the initial screening colonoscopy, where approximately four to fourteen biopsies were collected for all subjects. For each location sampled (at least ileum and 10cm from rectum, plus discretionary sites of inflammation), one biopsy was collected for standard histopathology at the individual institution, two biopsies were collected and stored in RNAlater for molecular data generation (host and microbial, stored at −20 °C), and one biopsy was collected and placed in a sterile tube with 5% glycerol (stored at −80 °C). If possible, additional biopsies from inflamed tissue, as well as nearby non-inflamed tissue were taken from CD/UC subjects. For adult subjects, a second set of biopsies were also collected from each location (rectum and ileum) for epithelial cell culture (detailed protocols: http://ibdmdb.org/protocols). All biopsies were stored for up to two months at the collection site, and shipped overnight on dry ice to Washington University for epithelial cell culture or to the Broad Institute for molecular profiling.

Blood draws

Blood draws (whole blood and serum) were taken at the quarterly clinical visits. For whole blood, 1 mL of blood was collected and stored at −80 °C. For serum, blood was drawn into a 5mL SST tube, and left at room temperature for 40 minutes. This was centrifuged for 15 minutes at 3,000 rpm and 0.5 mL portions were immediately aliquoted into 2 mL microtubes. Tubes were stored at −80 °C.

Stool samples

Stool specimens were collected both at the clinical visits as well as biweekly by mail using a home collection kit developed for the project (http://ibdmdb.org/protocols) and previously validated46. Subjects first deposited stool into a collection bowl suspended over a commode. Subject then collected two aliquots using a scoop to transfer stool into two Sarstedt 80.623 tubes: one with approximately 5 mL molecular biology grade 100% ethanol, and one with no preservative. Stool samples were then sent from each participant by FedEx to the Broad Institute where they were processed immediately prior to storage at −80 °C. The ethanol tube was centrifuged to pellet stool, which was subaliquotted, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube for metabolomic analysis. Stool from ethanol was aliquoted into 2 ml cryovials in ~100–200 mg aliquots, prioritizing specimens for meta’omic sequencing, metabolomics, and viromics in that order. Any remaining stool was stored in additional aliquot tubes. 100mg of the non-ethanol stool was stored for assaying fecal calprotectin and the remainder was saved in a second tube. All samples were stored at −80 °C after receipt prior to processing. This home-collection method was shown previously to produce reproducible results compared to flash-frozen samples46, consistent with previous observations across data types47–49. Note that an accurate estimate of the stool water content could not be obtained, since samples were collected by subjects and preserved in ethanol at room temperature until aliquots were generated for the different data generation platforms.

Participant and sample metadata

Descriptions of each participant and specimen were captured at baseline and accompanying each specimen collection, respectively. At baseline (i.e. during or prior to the screening colonoscopy), subjects completed a Reported Symptoms Questionnaire, the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire50, a Food Frequency Questionnaire, and an Environmental Questionnaire, and the Simple Endoscopic Score51 for CD subjects or Baron’s Score52 for UC subjects was assessed.

During both follow-up visits and paired with mailed stool samples, subjects completed an Activity Index and Dietary Recall Questionnaire to assess their disease activity index (HBI for CD or SCCAI for UC) and provided a retrospective recall of their recent diet. All questionnaires, as well as detailed protocols (including product numbers) can be found on the IBDMDB data portal at http://ibdmdb.org/protocols. Responses and metadata are available at http://ibdmdb.org/results, and summaries of phenotypes for samples and subjects are available (Supplementary Fig. S3) along with summaries of the final time series for each subject (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Stool specimen processing

Sample selection

Sample selection proceeded in two phases, with an initial round of data generation producing a pilot metagenomics and metatranscriptomics dataset, analyzed separately53. This pilot sample selection included at least one sample per participant that was enrolled in the study at that time, two long time courses per disease group (CD, UC, non-IBD), and multiple shorter time courses, resulting in 300 samples. For a subset of 78 samples, metatranscriptomic data was generated. Samples were chosen based on sample mass, preferentially selecting samples that could be re-sequenced if needed during the later data generation.

For the second, larger phase of data generation, stool samples were selected for different assays with the goal of generating data tiling as many aspects of the cohort as possible, including per-subject time courses, cross-subject global time points, and samples from all patients, phenotypes, age ranges, clinical centers, and so forth (Fig. 1B). The subset of measurements performed for each sample was determined in large part by aliquot requirements (in particular, mass requirements for the assay relative to how much the patient provided) and cost.

For proteomics and metabolomics, 6 global time points were equally distributed over the year-long time series for as many subjects as possible. Restrictions such as available sample mass and missing samples were incorporated by selecting the nearest suitable sample in time, resulting in slight irregularities in the sampling pattern. In total, 546 metabolite profiles and 450 proteomics profiles were generated. From among these samples, a total of 768 were selected for metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and viromics, corresponding to 8 plates of 96 samples each. Samples already selected for proteomics/metabolomics were prioritised to facilitate integrated data analysis (316 samples had sufficient mass), resulting in 6 global time points for all subjects. In cases where the respective sample was not available for a subject, the nearest suitable sample in time was selected. Subjects with greater fluctuations in their HBI/SCCAI scores were then prioritised for a denser sampling, resulting in 12 long time courses for 5 CD, 4 UC, and 3 non-IBD subjects. The selection also includes 23 technical replicates for metagenomics, metatranscriptomics and viromics.

Finally, 576 additional samples were selected specifically for metagenomic sequencing (6 plates) resulting in a total of 1,344 metagenomic samples. Samples at previously-selected global time points and long time courses which had been restricted by available mass for other measurement types were prioritized. An additional 4 global time points were added by this process, as well as 15 long time courses (representing 10 CD, 10 UC, and 7 non-IBD subjects), and 22 samples which were previously sequenced for the pilot data and represent additional technical replicates. Lastly, 522 samples were selected for fecal calprotectin measurements, prioritizing samples that were selected for any other multi’omics data generation and representing a broad overview of the cohort. Of a total of 2,653 collected stool samples 1,785 generated at least one measurement type (Fig. 1B).

Sample selection for RNA-seq and 16S sequencing from biopsies, and host genotyping from blood draws, aimed to cover the 95 subjects who contributed at least 14 stool samples, as permitted by the availability of biopsies/blood draws for each assay. Sample selection from biopsies additionally aimed to cover biopsies from inflamed and non-inflamed sites. In total, 254 biopsies were selected for RNA-seq, covering 43 CD, 25 UC, and 22 non-IBD subjects, and distributed across biopsy sites and inflammation statuses (Extended Data Fig. 6A); and 161 biopsies were selected for 16S sequencing, covering 36 CD, 21 UC, and 22 non-IBD subjects. Exome sequencing was performed for 46 CD, 24 UC, and 22 non-IBD subjects.

Sample selection for remaining sample types (RRBS, blood serology) included all samples with a suitable sample available.

DNA and RNA isolation for metagenomics and metatranscriptomics

Total nucleic acid was extracted from one aliquot of each assayed stool sample via the Chemagic MSM I with the Chemagic DNA Blood Kit-96 from Perkin Elmer. This kit combines a chemical and mechanical lysis with magnetic bead-based purification. Prior to extraction on the MSM-I, TE buffer, Lysozyme, Proteinase K, and RLT Buffer with beta-mercaptoethanol were added to each stool sample. The stool lysate solution was vortexed to mix.

Samples were then placed on the MSM I unit to automate the following steps: M-PVA Magnetic Beads were added to the stool lysate solution and vortexed to mix. The bead-bound total nucleic acid was then removed from solution via a 96-rod magnetic head and washed in three ethanol-based wash buffers. The beads were then washed in a final water wash buffer. Finally, the beads were dipped in elution buffer to resuspend the DNA sample in solution. The beads were then removed from solution, leaving purified total nucleic acid eluate. The eluate was then split into two equal volumes, one for DNA the other for RNA. SUPERase-IN solution was added to the DNA samples, the reaction was cleaned up using AMPure XP SPRI beads. DNase was added to the RNA samples, and the reaction was cleaned up using AMPure XP SPRI beads.

DNA samples were quantified using a fluorescence-based PicoGreen assay. RNA samples were quantified using a fluorescence-based RiboGreen assay. RNA quality was assessed via smear analysis on the Caliper LabChip GX.

Metagenome sequencing

Metagenomes were generated from the resulting DNA for 1,638 stool samples, selected to obtain both a broad overview of targeted, aligned time points for all subjects (Fig. 1B), complemented by a dense sampling of subjects which tended to have greater disease activity, as determined by their HBI or SCCAI scores.

Whole genome fragment libraries were prepared as follows. Metagenomic DNA samples were quantified by Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay (Life Technologies) and normalized to a concentration of 50 pg/uL. Illumina sequencing libraries were prepared from 100–250pg of DNA using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol, with reaction volumes scaled accordingly. Prior to sequencing, libraries were pooled by collecting equal volumes (200 nl) of each library from batches of 96 samples. Insert sizes and concentrations for each pooled library were determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 kit (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were sequenced on HiSeq2000 or 2500 2×101 to yield ~10 million paired end reads. Post-sequencing de-multiplexing and generation of BAM and FASTQ files were generated using the Picard suite (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard).

Metatranscriptome sequencing

Metatranscriptomes were generated for 855 stool samples, subsampled from metagenomic selections as above. Illumina cDNA libraries were generated using a modified version of the RNAtag-seq protocol54. Briefly, 500 ng −1 μg of total RNA was fragmented, depleted of genomic DNA, dephosphorylated, and ligated to DNA adapters carrying 5’-AN8–3’ barcodes of known sequence with a 5’ phosphate and a 3’ blocking group. Barcoded RNAs were pooled and depleted of rRNA using the RiboZero rRNA depletion kit (Epicentre). Pools of barcoded RNAs were converted to Illumina cDNA libraries in 2 main steps: (i) reverse transcription of the RNA using a primer designed to the constant region of the barcoded adaptor with addition of an adapter to the 3’ end of the cDNA by template switching using SMARTScribe (Clontech) as described55; (ii) PCR amplification using primers whose 5’ ends target the constant regions of the 3’ or 5’ adaptors and whose 3’ ends contain the full Illumina P5 or P7 sequences. cDNA libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform to generate ~13 million paired end reads.

Viromics

703 stool samples were selected for viral profiling, following the sample selection used for metatranscriptomics, adjusted slightly only when aliquots were unavailable (Fig. 1C). Viral nucleic acids were extracted using the MagMax Viral RNA Isolation Kit (Cat # AM1939, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Viral RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript II RT (Cat # 18064014, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and random hexamers. After short molecule and random hexamer removal with ChargeSwitch (Cat # CS12000, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), molecules were amplified and tagged with a BC12-V8A2 construct56 using AccuPrimeTM Taq polymerase and cleaned with ChargeSwitch kit.

The resulting viral amplicons were normalized, pooled, and made into an Illumina library without shearing. The library (150–600 bp) was loaded in an Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced using the 2×100 bp chemistry. Reads were demultiplexed into a sample bin using the barcode prefixing read-1 and read-2, allowing zero mismatches. Demultiplexed reads were further processed by trimming off barcodes, semi-random primer sequences, and Illumina adapters. This process utilized a custom demultiplexer and the BBDuk algorithm included in BBMap (http://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap). The resulting trimmed dataset was analyzed using a pipeline created at the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research at Baylor College of Medicine57. Briefly, the viral analysis pipeline employs a clustering algorithm creates putative viral genomes using a mapping assembly strategy that leverages nucleotide and translated nucleotide alignment information. Viral taxonomies were assigned using a scoring system that incorporates nucleotide and translated nucleotide alignment results in a per-base fashion and optimizes for the highest resolution taxonomic rank.

Metabolomics

Sample selection, receipt, and storage

Sample selection for metabolomics aimed to obtain only a broad sampling of many subjects. In total 546 stool samples were selected for profiling (Fig. 1B). A portion of each selected stool sample (40–100 mg) and the entire volume of originating ethanol preservative were stored in 15 mL centrifuge tubes at −80 °C until all samples were collected.

Sample processing

Samples were thawed on ice and then centrifuged (4 °C, 5,000 x g) for 5 minutes. Ethanol was evaporated using a gentle stream of nitrogen gas using a nitrogen evaporator (TurboVap LV; Biotage, Charlotte, NC) and stored at −80 °C until all samples in the study had been dried. Aqueous homogenates were generated by sonicating each sample in 900 μl of H2O using an ultrasonic probe homogenizer (Branson Sonifier 250) set to a duty cycle of 25% and output control of 2 for 3 minutes. Samples were kept on ice during the homogenization process. The homogenate for each sample was aliquoted into two 10 µL and two 30 µL in 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes for LC-MS sample preparation and 30 µL of homogenate from each sample were transferred into a 50 mL conical tube on ice to create a pooled reference sample. The pooled reference mixture was mixed by vortexing and then aliquoted (100 µL per aliquot) into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes. Aliquots and reference sample aliquots were stored at −80 °C until LC-MS analyses were conducted.

LC-MS analyses

A combination of four LC-MS methods were used to profile metabolites in the fecal homogenates, as previously published58; two methods that measure polar metabolites, a method that measures metabolites of intermediate polarity (e.g. fatty acids and bile acids), and a lipid profiling method. For the analysis queue in each method, subjects were randomized and longitudinal samples from each subject were randomized and analyzed as a group. Additionally, pairs of pooled reference samples were inserted into the queue at intervals of approximately 20 samples for QC and data standardization. Samples were prepared for each method using extraction procedures that are matched for use with the chromatography conditions. Data were acquired using LC-MS systems comprised of Nexera X2 U-HPLC systems (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments; Marlborough, MA) coupled to Q Exactive/Exactive Plus orbitrap mass spectrometers (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA). The method details are summarized below:

LC-MS Method 1 – HILIC-pos: positive ion mode MS analyses of polar metabolites. LC-MS samples were prepared from stool homogenates (10 µL) via protein precipitation with the addition of nine volumes of 74.9:24.9:0.2 v/v/v acetonitrile/methanol/formic acid containing stable isotope-labeled internal standards (valine-d8, Isotec; and phenylalanine-d8, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories; Andover, MA). The samples were centrifuged (10 min, 9,000 x g, 4°C), and the supernatants injected directly onto a 150 × 2 mm Atlantis HILIC column (Waters; Milford, MA). The column was eluted isocratically at a flow rate of 250 µL/min with 5% mobile phase A (10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid in water) for 1 minute followed by a linear gradient to 40% mobile phase B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) over 10 minutes. MS analyses were carried out using electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode using full scan analysis over m/z 70–800 at 70,000 resolution and 3 Hz data acquisition rate. Additional MS settings are: ion spray voltage, 3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 350°C; probe heater temperature, 300 °C; sheath gas, 40; auxiliary gas, 15; and S-lens RF level 40.

LC-MS Method 2 – HILIC-neg: negative ion mode MS analysis of polar metabolites. LC-MS samples were prepared from stool homogenates (30 µL) via protein precipitation with the addition of four volumes of 80% methanol containing inosine-15N4, thymine-d4 and glycocholate-d4 internal standards (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories; Andover, MA). The samples were centrifuged (10 min, 9,000 x g, 4°C) and the supernatants were injected directly onto a 150 × 2.0 mm Luna NH2 column (Phenomenex; Torrance, CA). The column was eluted at a flow rate of 400 µL/min with initial conditions of 10% mobile phase A (20 mM ammonium acetate and 20 mM ammonium hydroxide in water) and 90% mobile phase B (10 mM ammonium hydroxide in 75:25 v/v acetonitrile/methanol) followed by a 10 min linear gradient to 100% mobile phase A. MS analyses were carried out using electrospray ionization in the negative ion mode using full scan analysis over m/z 60–750 at 70,000 resolution and 3 Hz data acquisition rate. Additional MS settings are: ion spray voltage, −3.0 kV; capillary temperature, 350°C; probe heater temperature, 325 °C; sheath gas, 55; auxiliary gas, 10; and S-lens RF level 40.

LC-MS Method 3 – C18-neg: negative ion mode analysis of metabolites of intermediate polarity (e.g. bile acids and free fatty acids). Stool homogenates (30 µL) were extracted using 90 µL of methanol containing PGE2-d4 as an internal standard (Cayman Chemical Co.; Ann Arbor, MI) and centrifuged (10 min, 9,000 x g, 4 °C). The supernatants (10 µL) were injected onto a 150 × 2.1 mm ACQUITY BEH C18 column (Waters; Milford, MA). The column was eluted isocratically at a flow rate of 450 µL/min with 20% mobile phase A (0.01% formic acid in water) for 3 minutes followed by a linear gradient to 100% mobile phase B (0.01% acetic acid in acetonitrile) over 12 minutes. MS analyses were carried out using electrospray ionization in the negative ion mode using full scan analysis over m/z 70–850 at 70,000 resolution and 3 Hz data acquisition rate. Additional MS settings are: ion spray voltage, −3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 320°C; probe heater temperature, 300 °C; sheath gas, 45; auxiliary gas, 10; and S-lens RF level 60.

LC-MS Method 4 – C8-pos: Lipids (polar and nonpolar) were extracted from stool homogenates (10 µL) using 190 µL of isopropanol containing 1-dodecanoyl-2-tridecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine as an internal standard (Avanti Polar Lipids; Alabaster, AL). After centrifugation (10 min, 9,000 x g, ambient temperature), supernatants (10 µL) were injected directly onto a 100 × 2.1 mm ACQUITY BEH C8 column (1.7 µm; Waters; Milford, MA). The column was eluted at a flow rate of 450 µL/min isocratically for 1 minute at 80% mobile phase A (95:5:0.1 vol/vol/vol 10 mM ammonium acetate/methanol/acetic acid), followed by a linear gradient to 80% mobile-phase B (99.9:0.1 vol/vol methanol/acetic acid) over 2 minutes, a linear gradient to 100% mobile phase B over 7 minutes, and then 3 minutes at 100% mobile-phase B. MS analyses were carried out using electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode using full scan analysis over m/z 200–1100 at 70,000 resolution and 3 Hz data acquisition rate. Additional MS settings are: ion spray voltage, 3.0 kV; capillary temperature, 300 °C; probe heater temperature, 300 °C; sheath gas, 50; auxiliary gas, 15; and S-lens RF level 60.

Metabolomics data processing

Raw LC-MS data were acquired to the data acquisition computer interfaced to each LC-MS system and then stored on a robust and redundant file storage system (Isilon Systems) accessed via the internal network at the Broad Institute. Nontargeted data were processed using Progenesis QIsoftware (v 2.0, Nonlinear Dynamics) to detect and de-isotope peaks, perform chromatographic retention time alignment, and integrate peak areas. Peaks of unknown ID were tracked by method, m/z and retention time. Identification of nontargeted metabolite LC-MS peaks were conducted by i) matching measured retention times and masses to mixtures of reference metabolites analyzed in each batch and ii) matching an internal database of >600 compounds that have been characterized using the Broad Institute methods. Temporal drift was monitored and normalized with the intensities of features measured in the pooled reference samples.

Proteomics

Sample selection and LC-MS/MS

Sample selection for proteomics largely followed sample selection for metabolomics (Fig. 1B–C), with slight adjustments when aliquots were unavailable. In total, 447 stool samples were targeted for profiling. From the selected samples, proteins were proteolytically digested using trypsin, and each digest subjected to automated offline high pH reversed-phase fractionation with fraction concatenation. LC-MS/MS analysis for each fraction was performed using a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer resident at UCLA, outfitted with a custom-built nano-ESI interface. Samples were loaded onto an in-house packed capillary LC column (70 cm x 75 μm, 3 μm particle size), and data were acquired for 120 min. Precursor MS spectra were collected over 400–2000 m/z, followed by data-dependent MS/MS spectra of the twelve most abundant ions, using a collision energy of 30%. A dynamic exclusion time of 30 s was used to discriminate against previously analyzed ions.

Peptide identification and protein data roll-up

Mass spectra from the resulting analyzes were evaluated using the MSGF+ software59 v10072 using the HMP 1 gut reference genomes (HMP_Refgenome-gut_2015–06-18). Briefly, after conversion of the metagenomic assemblies into predicted open reading frames (e.g., predicted proteins), libraries were created using the forward and reverse direction to allow determination of False Discovery Rate (FDR). The reverse decoy database allows measurement of the rate of detection of false hits, which in turn allows for FDR calculation and appropriate filtering of the data to maximize the real peptide identifications while minimizing spurious ones. MSGF+ was then used to search the experimental mass spectra data against both the forward/reverse decoy databases. Cut-offs for data included: MSGF+ spectra probability (>1 × 1010, equivalent to a BLAST e-value), mass accuracy (±20 ppm), protein level FDR of 1% and one unique peptides per protein identification.

Fecal calprotectin

Fecal calprotectin was quantified for 652 stool samples total, which were stored at −80C without preservative prior to processing. Sample selection focused on obtaining a broad survey of all subjects rather than detailed time series (Fig. 1B). Calprotectin was quantified using QUANTA Lite® Calprotectin ELISA (Inova Diagnostics 704770) following manufacturer protocol. Between 80–120 mg of stool was used for input. Incubation time prior to stopping reaction was adjusted to obtain OD 405nm values in the suggested range for assay.

Biopsy specimen processing

Co-isolation of DNA and RNA from frozen tissue

DNA and RNA were extracted from RNA-later-preserved biopsies via the AllPrep DNA/RNA Universal Kit from Qiagen. Biological samples were cut in 20–25mg pieces on a dry ice batch, then placed in tubes with a steel bead for mechanical homogenization and a highly denaturing guanidine isothiocyanate-containing buffer, which immediately inactivates DNases and RNases to ensure isolation of intact DNA and RNA. After homogenization, the lysate was passed through an AllPrep DNA Mini spin column. This column, in combination with the high-salt buffer, allows selective and efficient binding of genomic DNA. On-column Proteinase K digestion in optimized buffer conditions allows purification of high DNA yields from all sample types. The column was then washed and DNA was eluted in TE buffer. Flow-through from the AllPrep DNA Mini spin column was digested by Proteinase K in the presence of ethanol. This optimized digestion, together with the subsequent addition of further ethanol, allowed for appropriate binding of total RNA, including miRNA, to the RNeasy Mini spin column. Samples were then digested with DNase I to ensure high-yields of DNA-free RNA. Contaminants were efficiently washed away and RNA was eluted in water.

16S rRNA gene profiling

178 biopsies were selected for 16S amplicon-based taxonomic profiling. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing protocol was adapted from the Earth Microbiome Project60 and the Human Microbiome Project61–63. Briefly, bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from the total mass of the biopsied specimens using the MoBIO PowerLyzer Tissue and Cells DNA isolation kit and sterile spatulas for tissue transfer. The 16S rDNA V4 region was amplified from the extracted DNA by PCR and sequenced in the MiSeq platform (Illumina) using the 2×250 bp paired-end protocol yielding pair-end reads that overlap almost completely. The primers used contained adapters for MiSeq sequencing and single-index barcodes such that PCR products may be pooled and sequenced directly61, targeting at least 10,000 reads per sample.

Read pairs were demultiplexed and merged using USEARCH v7.0.109064. Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a similarity threshold of 97% using the UPARSE algorithm65. OTUs were subsequently mapped to a subset of the SILVA database66 containing only sequences from the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene to determine taxonomies. Abundances were then recovered by mapping the demultiplexed reads to the UPARSE OTUs, producing the final taxonomic profiles. The 150 samples with ≥1000 mapped reads were used in downstream analyses.

Host RNA-Seq

cDNA library construction

In total, 252 biopsies selected for transcriptional profiling. Total RNA was quantified using the Quant-iT™ RiboGreen® RNA Assay Kit and normalized to 5 ng/ul. Following plating, 2 uL of ERCC controls (using a 1:1000 dilution) were spiked into each sample. An aliquot of 200ng for each sample was transferred into library preparation which was an automated variant of the Illumina TruSeq™ Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit. This method preserves strand orientation of the RNA transcript. It uses oligo dT beads to select mRNA from the total RNA sample. It is followed by heat fragmentation and cDNA synthesis from the RNA template. The resultant 500bp cDNA then goes through library preparation (end repair, base ‘A’ addition, adapter ligation, and enrichment) using Broad Institute designed indexed adapters substituted in for multiplexing. After enrichment the libraries were quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen (1:200 dilution). After normalizing samples to 5 ng/uL, the set was pooled and quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina Sequencing Platforms. The entire process is in 96-well format and all pipetting is done by either Agilent Bravo or Hamilton Starlet.

Illumina sequencing

Pooled libraries were normalized to 2nM and denatured using 0.1 N NaOH prior to sequencing. Flowcell cluster amplification and sequencing were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols using either the HiSeq 2000 or HiSeq 2500. Each run was a 101bp paired-end with an eight-base index barcode read. Data was organized using the Broad Institute Picard Pipeline which includes de-multiplexing and lane aggregation.

Blood specimen processing

Serological analysis

210 sera were analyzed for expression of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies (ASCA), anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1 by ELISA as previously described67, 68. Antibody levels were determined and the results expressed as ELISA units (EU/mL), which are relative to laboratory standards consisting of pooled, antigen reactive sera from of patients with well-characterized disease.

DNA isolation from whole blood

DNA was extracted via the Chemagic MSM I with the Chemagic DNA Blood Kit-96 from Perkin Elmer. The kit combines a chemical and mechanical lysis with magnetic bead-based purification. Whole blood samples were incubated at 37 °C for 5–10 minutes to thaw. The blood was then transferred to a deep well plate with protease and placed on the Chemagic MSM I. The following steps were automated on the MSM I.

M-PVA Magnetic Beads were added to the blood, protease solution. Lysis buffer was added to the solution and vortexed to mix. The bead-bound DNA was then removed from solution via a 96-rod magnetic head and washed in three Ethanol-based wash buffers to eliminate cell debris and protein residue. The beads were then washed in a final water wash buffer. Finally, the beads were dipped in elution buffer to resuspend the DNA. The beads were then removed from solution, leaving purified DNA eluate. The resulting DNA samples were quantified using a fluorescence-based PicoGreen assay.

Host exome sequencing

92 host exomes were sequenced from DNA extracts using previously published methods69. Whole exome libraries were constructed and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencer with 151 bp paired-end reads. Output from Illumina software was processed by the Picard pipeline to yield BAM files containing calibrated, aligned reads.

Library construction

Library construction was performed as described69 with some slight modifications. Initial genomic DNA input into shearing was reduced from 3 µg to 50 ng in 10 µL of solution and enzymatically sheared. In addition, for adapter ligation, dual-indexed Illumina paired end adapters were replaced with palindromic forked adapters with unique 8 base index sequences embedded within the adapter and added to each end.

In-solution hybrid selection for exome enrichment

In-solution hybrid selection was performed using the Illumina Rapid Capture Exome enrichment kit with 38Mb target territory (29Mb baited). The targeted region includes 98.3% of the intervals in the Refseq exome database. Dual-indexed libraries are pooled into groups of up to 96 samples prior to hybridization. The liquid handling is automated on a Hamilton Starlet. The enriched library pools are quantified via PicoGreen after elution from streptavadin beads and then normalized to a range compatible with sequencing template denature protocols.

Preparation of libraries for cluster amplification and sequencing

Following sample preparation, the libraries prepared using forked, indexed adapters were quantified using quantitative PCR (purchased from KAPA biosystems), normalized to 2 nM using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system, and pooled by equal volume using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system. Pools were then denatured using 0.1 N NaOH. Denatured samples were diluted into strip tubes using the Hamilton Starlet Liquid Handling system.

Cluster amplification and sequencing

Cluster amplification of the templates was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina) using the Illumina cBot. Flow cells were sequenced on HiSeq 4000 Sequencing-by-Synthesis Kits, then analyzed using RTA2.7.3

Host genetic data processing

Host genetic exome sequence data were processed using the Broad Institute sequencing pipeline by the Data Sciences Platform (Broad Institute). This was done in three steps -pre-processing (including reads mapping, alignment to a reference genome and data cleanup), variant discovery (including per-sample variant calling and joint genotyping), and variant filtering to produce callset ready for downstream genetic analysis -using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (detailed documentation at https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/documentation/).

Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) libraries were prepared for 221 biopsies and 228 blood samples as described previously70 with modifications detailed below. Briefly, genomic DNA samples were quantified using a Quant-It dsDNA high sensitivity kit (ThermoFisher, cat# Q33120) and normalized to a concentration of 10 ng/ul. A total of 100 ng of normalized genomic DNA was digested with MspI in a 20 ul reaction containing 1 ul MspI (20 U/ul) (NEB, cat# R0106L) and 2 ul of 10X CutSmart Buffer (NEB, cat# B7204S). MspI digestion reactions were then incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours followed by a 15 min. incubation at 65 °C.

Next, A-tailing reactions were performed by adding 1 ul dNTP mix (containing 10 mM dATP, 1 mM dCTP and 1 mM dGTP) (NEB, cat# N0446S), 1 ul Klenow 3’−5’ exo− (NEB, cat# M0212L) and 1 ul 10X CutSmart Buffer in a total reaction volume of 30ul. A-tailing reactions were then incubated at 30 °C for 20 min, followed by 37 °C for 20 min, followed by 65 °C for 15 min.

Methylated Illumina sequencing adapters70 were then ligated to the A-tailed material (30 ul) by adding 1 ul 10X CutSmart Buffer, 5 ul 10 mM ATP (NEB, cat# P0756S), 1 ul T4 DNA Ligase (2,000,000U/ml) (NEB, cat# M0202M) and 2ul methylated adapters in a total reaction volume of 40 ul. Adapter ligation reactions were then incubated at 16 °C overnight (16–20 hours) followed by incubation at 65 °C for 15 min. Adapter ligated material was purified using 1.2X volumes of Ampure XP according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Beckman Coulter, cat# A63881).

Following adapter ligation, bisulfite conversion and subsequent sample purification was performed using the QIAGEN EpiTect kit according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol designated for DNA extracted from FFPE tissues (QIAGEN, cat# 59104). Two rounds of bisulfite conversion were performed yielding a total of 40 ul bisulfite converted DNA.

In order to determine the minimum number of PCR cycles required for final library amplification, 50 ul PCR reactions containing 3 ul bisulfite converted DNA, 5 ul 10X PfuTurbo Cx hotstart DNA polymerase buffer, 0.5 ul 100 mM dNTP (25 mM each dNTP) (Agilent, cat# 200415), 0.5 ul Illumina TruSeq PCR primers (25 uM each primer)70 and 1 ul PfuTurbo Cx hotstart DNA polymerase (Agilent, cat# 600412) were prepared. Reactions where then split equally into four separate tubes and thermocycled using the following conditions: denature at 95 °C for 2 min followed by ‘X’ cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 45 s (where ‘X’ number of cycles = 11, 13, 15 and 17), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were purified using 1.2X volumes of Ampure XP and analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer using a High Sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent, cat# 5067–4626). Once the optimal number of PCR cycles was determined, 200 ul PCR reactions were prepared using 24 ul bisulfite converted DNA, 20 ul 10X PfuTurbo Cx hotstart DNA polymerase buffer, 2 ul 100 mM dNTPs (25 mM each), 2 ul Illumina TruSeq PCR primers (25 uM each) and 4 ul PfuTurbo Cx hotstart DNA polymerase with the thermal cycling conditions listed above. PCR reactions were purified using 1.2X volumes of Ampure XP according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol and analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer using a High Sensitivity DNA kit.

RRBS sequencing produced an average of 15.0M reads (sd 4.0M reads) over all 504 samples, with 448 (88.9%) samples exceeding 10M reads. Samples were analyzed with Picard 2.9.4 using default parameters, resulting in a mean alignment rate to the human genome hg19 of 95.1%. Mean CpG coverage was 8.9X (sd. 2.1%). As expected, 99.9% (sd. 0.02%) of non-CpG bases and 49.8% (sd 2.8%) of CpG bases were converted.

Data handling

Informatics for microbial community sequencing data