Abstract

A major limitation of current humanized mouse models is that they primarily permit the analysis of human-specific pathogens that infect hematopoietic cells. However, most human pathogens target other cell types including epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells. Here, we show that implantation of human lung tissue, that contains up to 40 cell types including non-hematopoietic cells, into immunodeficient mice (lung-only mice [LoM]) resulted in the development of a highly vascularized lung implant. We demonstrate that emerging and clinically relevant human pathogens such as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Zika virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and cytomegalovirus replicate in vivo in these lung implants. When incorporated into bone marrow/liver/thymus (BLT) humanized mice (BLT-L mice), lung implants are repopulated with autologous human hematopoietic cells. We show robust antigen-specific humoral and T cell responses following cytomegalovirus infection that control virus replication. LoM and BLT-L mice dramatically increase the number of human pathogens that can be studied in vivo facilitating the in vivo testing of therapeutics.

Although in vivo animal models exist for many clinically relevant and emerging human pathogens1–4, they currently all lack biologically relevant human cells, which limits our ability to study pathogen replication, pathogenesis, immune responses and sensitivity to therapeutics in vivo. In vivo animal models with natural human target cells for infection are needed to accelerate the development and testing of effective vaccines and therapeutics for many highly relevant human pathogens such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), in addition to many emerging pathogens1; all of which cause significant global mortality and morbidity5–9.

Although commonly used, inbred mouse strains do not faithfully recapitulate important aspects of human disease and the human immune response10. Furthermore, many human pathogens do not replicate in wild-type mice1, 5, 11–21. The availability of highly immunodeficient mouse strains allows for the creation of human/mouse chimeric models (humanized mice) that are locally or systemically reconstituted with human hematopoietic cells following engraftment of human tissues and/or stem cells. Humanized mice have been used to study human immune development and human-specific pathogens that replicate in human hematopoietic cells (e.g. Epstein-Barr virus, dengue virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus) and to test the efficacy of preventative and therapeutic agents5, 11–19, 22, 23. Bone marrow/liver/thymus (BLT) humanized mice are generated by bone marrow transplantation of immunodeficient mice implanted with autologous human thymus/liver tissue. BLT mice are systemically reconstituted with human innate (monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells) and adaptive (B and T cells) immune cells. The presence of a human thymic organoid in the BLT model allows for human T cell education on human leukocyte antigens (HLA) and the induction of HLA-restricted T cell responses consistent with those observed in humans14, 24, 25.

The applications of current humanized mouse models for biomedical research would be significantly broadened by the inclusion of human non-hematopoietic cell types, the primary targets of most human pathogens, that can present antigen to autologous human immune cells in the full context of HLA5, 9, 26–29. The human lung contains up to 40 different cell types including epithelial, endothelial, mesenchymal and smooth muscle cells30 and it is an important natural site of infection9, 26, 31–34. We implanted human lung tissue subcutaneously into the back of immunodeficient mice to create humanized lung-only mice (LoM). The human lung tissue vascularizes, expands and persists as a human lung implant, and supports replication of viral and bacterial human pathogens in vivo. When incorporated into BLT mice (BLT-L mice), lung implants are repopulated with autologous human innate and adaptive immune cells. Direct inoculation of BLT-L human lung implants with HCMV induces HCMV-specific human IgM, IgG and T cell responses that can effectively control infection in vivo. LoM and BLT-L mice expand the susceptibility of humanized mice to a broad range of human pathogens. These new models can be used to study pathogen replication, pathogenesis, immune reactivity and human therapies.

RESULTS

Human lung tissue development into ectopic lung implants

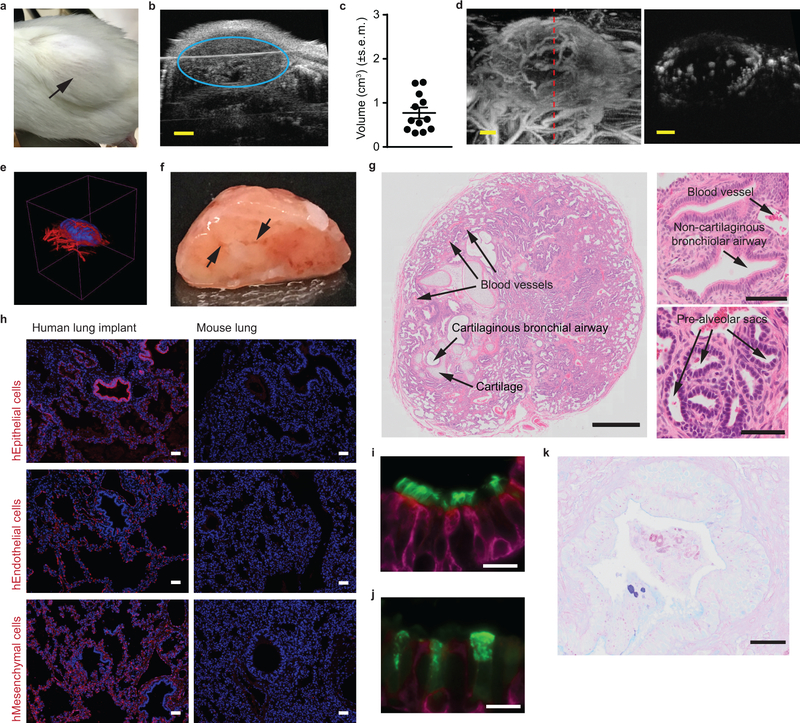

Two small pieces of human lung tissue were surgically implanted into separate sites of the back of immunodeficient mice to create humanized lung-only mice (LoM). Over time, the implanted tissue expanded (Fig. 1a). B-mode ultrasound imaging established the presence of well-defined implants with a mean volume of 0.75 cm3 (± 0.42 cm3) (Fig. 1b,c). Acoustic angiography35, 36 revealed angiogenesis and the formation of large blood vessels (Fig. 1d, left panel). Vasculature was also observed within the human lung implant (Fig. 1d, right panel). Fig. 1e and Supplementary Video show a 3D reconstruction of the implant, illustrating its structure and extensive vasculature. Finally, surgical excision of a human lung implant revealed its well-defined structure and internal vasculature (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1: Subcutaneous implantation of human lung tissue into immunodeficient mice results in the development of readily accessible ectopic human lung implants.

(a) Subcutaneous human lung implant (n=1 LoM imaged, black arrow). (b) B-mode ultrasound imaging of a human lung implant (blue circle) under the skin. (c) Volume (cm3) of human lung implants (n=12, filled circles) in mice determined from B-mode ultrasound images. (d-e) In vivo visualization of human lung implant blood vessel vascularization by acoustic angiography (n=12 implants analyzed). (d) Acoustic angiography image showing blood vessels encapsulating (left) and within (right) a human lung implant. A red dashed line (left panel) indicates the location of the implant cross-section depicted in the right panel. (e) Three-dimensional rendering of vascularization (red) of a human lung implant (blue). (f) Gross structure of an excised human lung implant (n=1) two months post-surgery exhibiting blood vessel vascularization (black arrows). (g) Histologic sections of human lung implants (n=6 implants analyzed) showing presence of airways, ciliated epithelium, alveolar structures, cartilage and associated blood vessels (images: top panel 5X, bottom panels 100X). (h) Immunofluorescence staining for human epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells in a human lung implant (n=3 implants analyzed, left panels) and mouse lung (n=1 mouse lung analyzed, right panels) (positive cells: red, nuclei: blue). Immunofluorescence staining for cytokeratin 19 (magenta) and (i) cilia or (j) club cells (green, scale bars: 20 µm) in a human lung implant (n=4 implants analyzed). (k) AB-PAS staining for mucous secretions (blue, scale bars: 20 µm) in a human lung implant (n=4 implants analyzed). In c, horizontal lines represent mean ± s.e.m. Scales bars in b and d: 2 mm. In g and h, scale bars shown for 5X (1 mm), 10X (50 µm), and 100X (100 µm) images.

Even though the lung implants are ectopic and not ventilated, we observed structures that are characteristic of the human lung including airways, ciliated epithelium, alveolar structures, cartilage and associated blood vessels (Fig. 1g). We observed cartilaginous bronchial and non-cartilaginous bronchiolar airways both of which were lined by ciliated airway epithelium (Fig. 1g). Pre-alveolar sacs were also present (Fig. 1g). The presence of human epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells was also confirmed (Fig. 1h and i). Club cells and non-ciliated secretory epithelial cells were also present (Fig. 1j). Staining for mucus secretions revealed the presence of mucin-secreting human globlet epithelial cells (Fig. 1k). Ex vivo culture of lung implant cells with LPS demonstrated their capacity to produce human cytokines and chemokines (Supplementary Table 1).

Analysis of human donor matched lung tissue at the time of implantation and at two months post-implantation indicates continous human lung tissue development. Pre-alveolar sacs were expanded and both flattened and cubodial shaped epithelial cells could be observed in alveoli indicative of Type I and Type II pneumocytes respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Although not observed in lung tissue at the time of implantation, club cells were readily detected two months later (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Fig. 1) and ciliated epithelial cells were more abundant (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Consistent with reports of other subcutaneously implanted human tissues (e.g. synovial tissue and bone)37, 38, the vasculature within the human lung implants is primarily of human origin (Fig. 1h). Mouse endothelial and epithelial cells were not readily detected (Supplementary Fig. 2). Few hematopoietic cells (murine or human) could be detected in human lung implants (Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3). In summary, implantation of human lung tissue into the back of immunodeficient mice results in the development of well-defined, well-vascularized and easily accessible human lung implants with structures that resemble those present in human lung tissue and that is composed almost entirely of human cells.

LoM support infection of a broad range of human pathogens

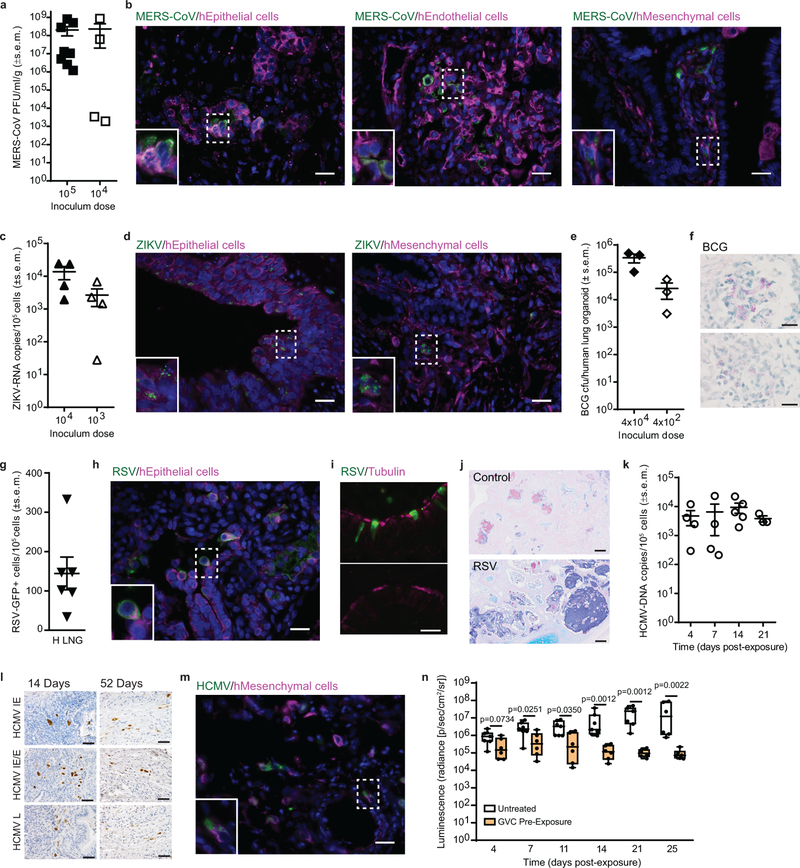

MERS-CoV is an emerging human pathogen that targets the human lung26 but does not infect mice, ferrets or hamsters due to genetic differences in its receptor, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4)1, 20, 21. MERS-CoV was inoculated directly into the human lung implants of LoM. MERS-CoV titers (mean: 2.02×108 ± 1.08×108 s.e.m. PFU/ml/g, range: 1.2×106-8.09×108 PFU/ml/g) in the human lung implants 48 h later were 3-logs higher than the inoculum (Fig. 2a). The presence of MERS-CoV antigen in human epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells indicated that MERS-CoV has broad cellular tropism in vivo (Fig. 2b). At a lower inoculum (104 PFU), MERS-CoV replication was variable but still readily detectable (mean: 2.29×108 ± 2.09×108 s.e.m. PFU/ml/g, range:1.92×103-8.57×108 PFU/ml/g) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2: LoM are susceptible to infection with a broad range of emerging and clinically relevant human pathogens.

(a) MERS-CoV titer in infected lung implants (105 PFU dose: n=8, filled squares; 104 PFU dose: n=4, open squares). (b) MERS-CoV-infected cells (green) co-stained for human epithelial (cytokeratin 19), endothelial (CD34) or mesenchymal (vimentin) cell markers (magenta) in a lung implant (n=1, images: 40X). (c) ZIKV-RNA copies in infected lung implants (104 FFU dose: n=4, filled upward triangles; 103 FFU dose: n=4, open upward triangles). (d) ZIKV-infected cells (green) co-stained for human epithelial or mesenchymal cell markers (magenta) in a lung implant (n=1, images: 40X). (e) BCG colony forming units (CFU) (4×104 CFU dose: n=3, closed diamonds; 4×102 CFU dose: n=3, open diamonds) and (f) Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast staining for BCG (positive: pink) in lung implants (n=2). Top and bottom images: 100X. (g) Number of RSV-GFP positive cells in lung implants (n=6, closed downward triangles). (h) RSV-infected cells (green) co-stained for a human epithelial cell marker (magenta) in a lung implant (n=1, image: 40X) (i) Co-staining for RSV-infected cells (green) and ciliated cells (magenta) (top) and isotype control antibody (green) and ciliated cells (magenta) (bottom panel) in a human lung implant (n=4 analyzed, images: 100X). (j) AB-PAS staining for mucus (blue) in a naïve control (n=4 analyzed, top) and RSV-infected (n=4 analyzed, bottom) lung implant (scale bars: 100 µm). (k) HCMV-DNA levels (open circles) in lung implants at 4 (n=4), 7 (n=4), 14 (n=5) and 21 (n=3) days post TB40/E exposure. (l) HCMV immediate early (IE), early (E) and late (L) protein expression in lung implants (n=1 per time point, images: 40X, positive cells: brown). (m) HCMV-infected cells (green) co-stained for a human mesenchymal cell marker (magenta) in a lung implant (n=1, image: 40X). (n) Ganciclovir (GCV) was administered to LoM daily (100 mg/kg) for 17 days starting two days prior to HCMV TB40/E exposure. HCMV-luciferase activity in lung implants of GCV-treated LoM (orange boxes; n=6) and untreated control LoM (white boxes; days 4–21, n=7 and day 25, n=6) was compared with a two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. The median (horizontal line), upper and lower quartiles (box ends) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers) are shown. In a-k, n=number of lung implants analyzed and horizontal lines represent mean ± s.e.m. In b, d, f, h, i, l and m scale bars shown for 40X (50 µm) and 100X (20 µm) images. In b, d, h and m the bottom left inset image represents the area indicated with a dashed box and nuclei are stained blue.

ZIKV has been detected in human neonatal lungs and shown to infect human lung cell lines in vitro31, 39. In wild-type mice, the type 1 interferon response suppresses ZIKV infection2. Human lung implants of LoM inoculated with ZIKV and assayed 48 h later contained robust levels of cell-associated ZIKV-RNA (mean 1.37×104 ± 5.91×103 s.e.m. ZIKV-RNA copies/105 cells, range: 5.21×103-2.42×104 ZIKV-RNA copies/105 cells) (Fig. 2c). ZIKV antigen was detected in human epithelial and mesenchymal cells (Fig. 2d). Similar to MERS-CoV, at a lower inoculum (103 FFU), ZIKV-RNA levels were variable but readily detectable (mean 2.65×103 ± 1.47×103 s.e.m. ZIKV-RNA copies/105 cells, range: 2.7×101-6.83×103 ZIKV-RNA copies/105 cells) (Fig. 2c).

We inoculated Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated live vaccine strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) into the human lung implants of LoM. Bacterial burden was assessed by colony formation (colony forming units, CFU). BCG levels in human lung implants of LoM 28 days post-exposure (mean: 3.40×105 ± 1.20×105 s.e.m. CFU, range: 1.03–4.95×105 CFU) were 8.5-fold higher than the inoculum (4×104 CFU) (Fig. 2e). BCG also replicated in the human lung implants of LoM receiving a 100-fold lower inoculum (4×102 CFU); the bacterial burden (mean: 2.57×104 ± 1.53×104 s.e.m. CFU, range: 3.10×103-5.49×104 CFU) was 65-fold higher than the inoculum. Acid-fast staining confirmed diffuse clusters of bacteria within the human lung implants (Fig. 2f).

We inoculated LoM implants with RSV expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). At 4 days post RSV inoculation, GFP-positive cells indicative of RSV infection and replication were detected in the human lung implants (mean: 144.38 ± 41.53 s.e.m. GFP+ cells/105 total cells, range: 35–333 GFP+ cells/105 total cells) (Fig. 2g). Infection of human airway epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo with RSV is characterized by extrusion of infected cells into the airway lumen and loss of cilia from infected ciliated cells40. Consistent with these observations, RSV-infected cells were observed protruding and shedding from the epithelial cell layer into the lumen (Fig. 2h) and they lacked co-staining for cilia (Fig. 2i). Large deposits of mucin were also noted in the airways of RSV-infected lung implants (Fig. 2j) as has been observed in the lungs of RSV-infected children41.

HCMV is an ubiquitous human-specific pathogen that does not replicate in other species5. We injected cell-free HCMV TB40/E, a clinical HCMV strain, into the human lung implants of LoM. HCMV-DNA was detected in the lung implants of LoM as early as 4 days post inoculation (mean: 4.70×103 ± 2.54×103 s.e.m. HCMV-DNA copies/105 cells, range: 2.94×102-1.19×104 HCMV-DNA copies/105 cells) (Fig. 2k). HCMV immediate early (IE), early (E) and late (L) proteins were detected in lung implants at 14 and 52 days post-inoculation indicating that HCMV infection was maintained over time (Fig. 2l). The expression of IE proteins is consistent with lytic HCMV replication in this model as observed during human primary infection and reactivation42. In vivo, HCMV antigen was observed in human mesenchymal cells (Fig. 2m). We determined the effect of pre-exposure prophylaxis with ganciclovir (GCV) on HCMV replication in LoM. GCV was administered once daily two days prior to and 14 days after inoculation of HCMV TB40/E expressing luciferase (Fig. 2n). HCMV replication was monitored over time by measuring luciferase activity. By four days post-exposure, HCMV levels were ~66% lower in the human lung implants of GCV-treated LoMs (mean: 3.36×105 ± 1.61 ×105 s.e.m. radiance) compared to untreated controls (mean: 1.00×106 ± 2.90 ×105 s.e.m. radiance) (Fig. 2n). HCMV levels continued to decline over time in GCV-treated LoM. At the end of the GCV treatment course (14 days post HCMV exposure), HCMV levels were ~2 logs lower in the lung implants of GCV-treated LoM (mean: 1.48×105 ± 4.96 ×104 s.e.m. radiance) compared to untreated LoMs (mean: 8.99×106 ± 5.02 ×106 s.e.m. radiance) (Fig. 2n). Suprisingly, after GCV treatment was discontinued, HCMV levels continued to decline. By 25 days post HCMV-exposure (11 days after the last GCV dose), HCMV levels in the lung implants of GCV-treated LoM were further reduced by ~40% (mean: 9.25×104 ± 2.65 ×104 s.e.m. radiance) and significantly lower than untreated controls (mean: 3.27×107 ± 1.69 ×107 s.e.m. radiance) (Fig. 2n). Together, these results demonstrate the ability of LoM to sustain replication of several clinically relevant human pathogens and to serve as a platform for the in vivo testing of existing and novel antimicrobials.

HCMV gene expression is consistent with lytic replication

In healthy individuals, HCMV establishes a life-long latent infection. In immune suppressed individuals such as transplant and AIDS patients, HCMV can reactivate resulting in uncontrolled lytic replication causing a multi-organ CMV syndrome43. Therefore, novel antivirals are needed that can inhibit HCMV lytic replication in vivo to ameliorate clinical symptoms of CMV disease. Since natural infections are typically asymptomatic and undiagnosed, the profile of HCMV genes expressed during lytic replication in vivo has not been determined on a genome-wide scale due to the difficulty of obtaining acutely infected samples. To define the complement of HCMV genes expressed in human tissue in vivo, we injected cell-free HCMV TB40/E into the human lung implants of LoM. HCMV (ds)cDNA was enriched with biotinylated probes spanning both strands of the entire HCMV genome and next generation sequencing used to measure viral gene expression. Using this novel approach, we were able to measure, for the first time, the complement of viral genes expressed in vivo in human tissue during lytic replication. Results revealed widespread HCMV gene expression spanning the viral genome, consistent with robust lytic replication (Supplementary Fig. 4). Expression of known lytic genes encoding IE proteins IE1 (UL123) and IE2 (UL122), early proteins (UL44 and UL38), and late proteins pp65 (UL83) and pp71 (UL82) were detected. By contrast, expression of UL138, a well-characterized latency gene, was not observed. These results serve as proof-of-principle of the utility of LoM to investigate key aspects of HCMV replication in human lung tissue in vivo.

The human innate and adaptive immune system of BLT-L mice

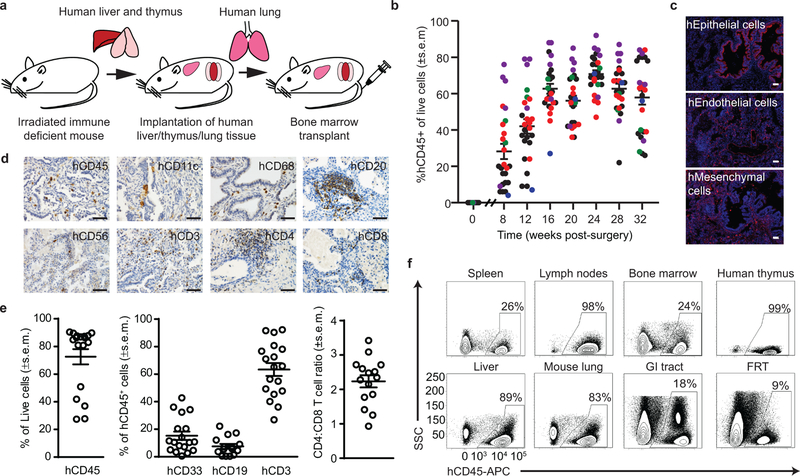

We generated a new in vivo model with human lung implants and an autologous human immune system by constructing BLT mice with autologous human lung implants (BLT-L humanized mice). BLT-L mice were constructed by surgically implanting 1) autologous human thymus and liver tissue under the kidney capsule and 2) human lung tissue subcutaneously into the back of the same pre-conditioned (irradiated) immunodeficient mouse followed by bone marrow transplantation with autologous human hematopoietic stem cells (Fig. 3a). Over time, BLT-L mice developed human lung implants and robust levels of human hematopoietic cells (hCD45+) in peripheral blood (PB) that were sustained for at least 8 months (last time analyzed) (Fig. 3b). The PB of BLT-L mice was reconstituted with human myeloid cells, B cells and T cells, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 3: Systemic reconstitution of BLT-L humanized mice with human innate and adaptive immune cells.

(a) Construction of BLT-L humanized mice. (b) Human hematopoietic cells (hCD45+) in peripheral blood of BLT-L mice (n=26 mice, 5 cohorts). Colors indicate BLT-L mouse cohorts. (c) Immunofluorescence staining for human epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells in a human lung implant of a BLT-L mouse (n=4 mice analyzed, positive cells: red, nuclei: blue). Images shown are at 10X magnification (scale bars: 50 µm). (d) Human hematopoietic (hCD45) cells including dendritic cells (hCD11c), macrophages (hCD68), B cells (hCD20), NK/NK T cells (hCD56), and T cells (hCD3, hCD4 and hCD8) in the human lung implant (n=3 mice analyzed, positive cells: brown). Images shown are at 40X magnification (scale bars: 50 µm). (e) Levels of hCD45 cells including human myeloid cells (hCD33), B cells (hCD19) and T cells (hCD3) as well as the ratio of human CD4:CD8 T cells in the human lung implants (open circles) of BLT-L mice (hCD45, hCD33 and hCD3 analysis n=18 implants and hCD19 and hCD4:CD8 analysis, n=15 implants). (f) Human CD45+ cells in tissues of BLT-L mice (n=4 mice analyzed) by flow cytometry. GI: gastrointestinal. FRT: female reproductive tract. In b and e, horizontal lines represent mean ± s.e.m.

In addition to human epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells (Fig. 3c), human lung implants of BLT-L mice contained human innate and adaptive immune cells (Fig. 3d). Ex vivo stimulation of these cells with PMA/ionomycin or LPS demonstrated their broad capacity for human cytokine (pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory) and chemokine production (Supplementary Table 2). The human hematopoietic cells present in the human lung implants of BLT-L mice (hCD45+, mean: 72.5% ± 5.5% s.e.m., range: 27.4–90.4%) included human myeloid cells (hCD33+, mean: 15.2% ± 3.0% s.e.m., range: 0.5–42.8%), B cells (hCD19+, mean: 7.5% ± 1.7% s.e.m., range: 0.4–22.2%) and T cells (hCD3+, mean: 63.4% ± 4.6% s.e.m., range: 26.9–92.3%) (Fig. 3e). No significant difference in human myeloid cell, B cell or T cell levels was observed between the human lung implants and mouse lung of BLT-L mice (Supplementary Fig. 6). CD4+ and CD8+ human T cells were present in the human lung implants of BLT-L mice. Human CD4+ T cell levels were significantly lower (p=6.472e-7) and CD8+ T cell levels were significantly higher (p=0.0004) in the human lung implants of BLT-L mice compared to the mouse lung. The CD4:CD8 T cell ratio (mean: 2.2 ± 0.17 s.e.m., range: 0.93–3.42) in human lung implants (Fig. 3e) was similar to that observed in humans44. No difference in T cell activation was observed (Supplementary Fig. 6). Memory (CD45RO+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were present in the human lung implants of BLT-L mice, the majority of which expressed an effector memory phenotype (CCR7-negative) (CD4+ T cells, mean: 87.2% ± 1.97% s.e.m., range: 81.8–90.8% and CD8+ T cells, mean: 97.1% ± 0.44% s.e.m., range: 96.1–97.9%) (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). We also identified the presence of CD4+ (mean: 25.4% ± 3.58% s.e.m., range: 18.5–35.5% of memory CD4+ T cells) and CD8+ (mean: 38.5% ± 7.11% s.e.m., range: 21.0–51.8% of memory CD8+ T cells) tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM, CD45RO+CD69+) in the human lung implants of BLT-L mice as observed in humans (Supplementary Fig. 7c,d)44. Like BLT mice, in addition to the human lung implant, human hematopoietic cells were systemically distributed throughout the animals including primary and secondary immune tissues (bone marrow, human thymic implant, spleen and lymph nodes), effector sites and mucosal tissues (lung, liver, gastrointestinal [GI] tract and female reproductive tract [FRT]) of BLT-L mice (Fig. 3f). Innate and adaptive human immune cells were present in all tissues analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 7e).

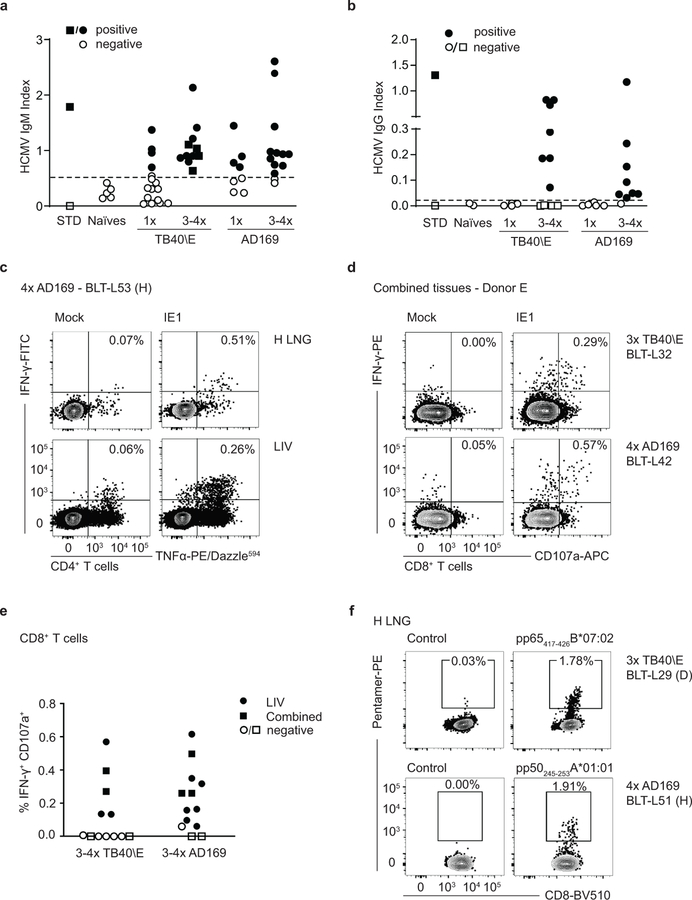

Immune mediated control of HCMV infection in BLT-L mice

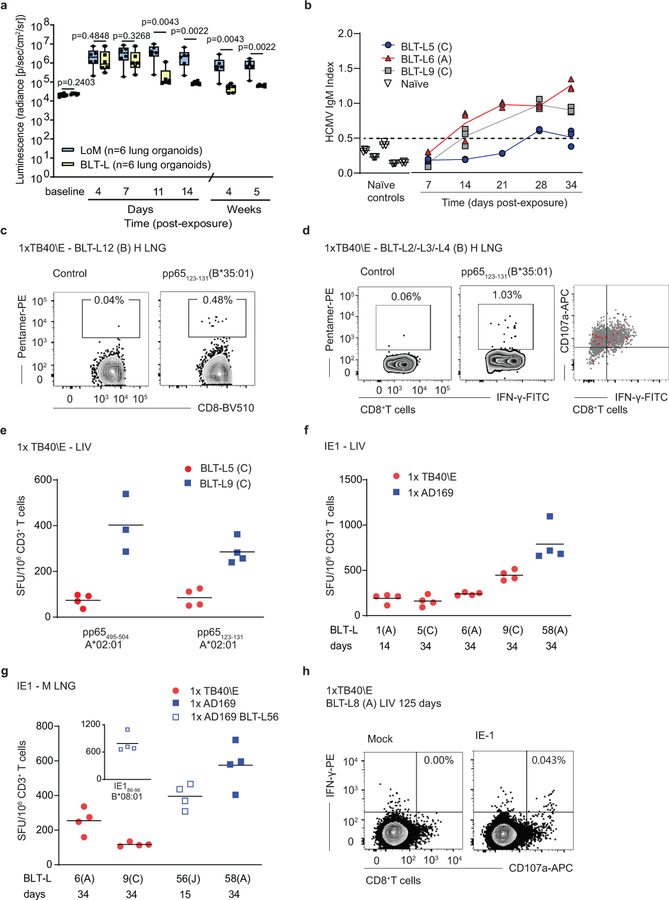

LoM and BLT-L mice were inoculated with HCMV TB40/E expressing luciferase45. HCMV replication was detectable in the human lung implants of LoM and BLT-L mice at 4 days post-inoculation (Fig. 4a). In LoM, robust HCMV replication was maintained up to 5 weeks post-inoculation (last time point analyzed) (Fig. 4a). In contrast, in BLT-L mice virus replication began to decline by 11 days post-inoculation (Fig. 4a). Luciferase activity in BLT-L mice was significantly lower compared to LoM (Fig. 4a). HCMV replication in BLT-L mice continued to decline over time (Fig. 4a). Specifically, luciferase activity in the human lung implants of BLT-L mice at week 4 (mean: 5.10×104 ± 2.25×104 s.e.m. radiance, range: 2.68–8.4×104 radiance) and week 5 (mean: 6.46×104 ± 8.08×103 s.e.m. radiance, range: 5.5–7.47×104 radiance) post-inoculation approached baseline levels (mean: 2.34×104 radiance) and was significantly lower compared to LoM (Fig. 4a). These results demonstrate that while the human lung implants of LoM and BLT-L mice support HCMV infection, in contrast to LoM, HCMV replication is efficiently controlled in BLT-L mice.

Fig. 4: HCMV infection induces robust, sustained humoral and T cell responses that control virus replication in BLT-L mice.

(a) HCMV TB40/E-luciferase activity in lung implants of LoM (blue boxes; n=6 implants) and BLT-L mice (yellow boxes; n=6 implants). Baseline (BL): luminescence measured pre-exposure. The median (horizontal line), upper and lower quartiles (box ends) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers) are shown. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test. (b) HCMV-specific IgM in the plasma of HCMV-exposed BLT-L mice (TB40/E: BLT-L5 and BLT-L6, ADrUL131: BLT-L 9) and five naïve control BLT-L mice. Mean values (horizontal lines) and technical replicates are shown for each mouse. Dashed line: threshold for seropositivity defined from naïve mice. (c) HCMV-specific CD8+ T cells detected by pentamer-reactivity in the lung implant (H LNG) of one BLT-L mouse 12 days post-exposure. (d) Pentamer-reactive HCMV-specific CD8+ T cells in the lung implant 21 days post-exposure (left). Overlay of pentamer-reactive cells (red) on PMA/ionomycin stimulated CD8+ T cells (gray) from one BLT-L mouse is shown (right). (e) IFN-γ ELISpot reactivity to commonly targeted CD8+ T cell epitopes in human infection. Mean values (horizontal lines) and technical replicates are shown for two BLT-L mice. SFU: spot forming units. (f and g) IFN-γ ELISpot reactivity to the HCMV Immediate Early 1 (IE1) protein. Mean values (horizontal lines) and technical replicates are shown for six BLT-L mice. (e-g) ELISpot data are background subtracted. Criteria for positivity: ≥2x mean of replicate negative control wells and >50 SFU/million CD3+ T cells. (h) IE1-specific IFN-γ+CD107a+ CD8+ T cells detected 125 days post-HCMV exposure in one BLT-L mouse. (e-h) Cells were isolated from the (e, f and h) liver (LIV) or (g) mouse lung (M LNG). (b-h) BLT-L cohorts are indicated in parentheses. (c-h) BLT-L mice were exposed to HCMV strains TB40/E or AD169 as indicated. Full details of immune reactivity for each BLT-L mouse are indicated in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

Levels of human cytokines and chemokines were analyzed in BLT-L mice pre and post HCMV TB40/E inoculation. At 4 days post inoculation, increased plasma levels of human GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, MDC, IP-10, GRO and MCP-1 were detected (Supplementary Fig. 8). HCMV-specific human antibody and T cell responses were examined in BLT-L mice exposed to the three different HCMV strains: TB40/E, AD169 and ADrUL131. AD169 is a well-characterized fibroblast-adapted laboratory strain that lacks the UL131 gene. ADrUL131 is an AD169 derivative in which UL131 is repaired46–48. PB plasma was collected longitudinally to measure HCMV-specific IgM levels. HCMV IgM levels in humans peak between one and three months after primary infection49. Consistent with human infection, HCMV IgM was detected as early as 14 days following TB40/E or ADrUL131 inoculation in different BLT-L cohorts (i.e. mice generated from different human donor tissues) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

To examine whether BLT-L mice induced CD8+ T cell responses to HCMV that are immunoprevalent in human infection, BLT-L donor tissue was HLA-typed (Supplementary Table 3), and reactivity to HCMV pentamers examined. HCMV infection induced classically HLA Ia-restricted HCMV pp65-specific CD8+ T cells in the human lung implant as early as 12 days following HCMV TB40/E inoculation (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Table 4). The functionality of these T cells was also examined by HCMV pentamer overlay of cells (mononuclear cells pooled from the liver of 3 mice, cohort B), stimulated with mitogen (Fig. 4d). All HCMV pentamer-reactive CD8+ T cells (red events, Fig. 4d right panel) were functional, producing the antiviral cytokine IFN-γ or both IFN-γ and the lytic granule marker CD107a.

Additional functional studies were performed using either ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot assays or intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) in which irradiated autologous B cell lines (BCL) were used to present HCMV peptide epitopes or peptide pools (HCMV pp65 or IE1) to tissue cells (Supplementary Table 4). Here, we compared TB40/E and AD169 infection. Like TB40/E, AD169 induced T cell responses to HLA-A and HLA-B pp65 peptide epitopes in BLT-L mice (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 5). Both strains also consistently induced T cell responses to HCMV IE1 as early as 14 days post-exposure (Fig. 4f,g and Supplementary Table 5). IE1 is an immunoprevalent HCMV protein not found in virions but expressed after infection42. The detection of IE1-specific responses is consistent with the in vivo lytic replication of HCMV observed in Fig. 4a. HCMV-specific T cell responses were detected in the human lung implant of BLT-L mice and systemically (liver and mouse lung) (Fig. 4c-h) and were maintained for up to 125 days (last time point analyzed) (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Table 4). Full details of T cell reactivity are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Our data demonstrating IE1-specific T cell responses in BLT-L mice and a progressive decline in TB40/E-luciferase activity indicates that these mice were productively infected with HCMV, but unlike LoM (Fig. 2k-m, Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9), virus replication was controlled. HCMV-DNA was readily detected in the human lung implants of all BLT-L mice analyzed <14 days post exposure (Supplementary Table 6). However, consistent with the immune-mediated virological control observed in BLT-L mice (Fig. 4a), only 55% of human lung implants analyzed between 14–34 days post-exposure, and none of the human lung implants analyzed after 34 days post-exposure had detectable levels of viral DNA (Supplementary Table 6). HCMV-DNA was rarely detected in other tissues analyzed (12/135) (Supplementary Table 6), suggesting that HCMV dissemination to peripheral tissues was limited and/or replication controlled.

Re-exposure boosts antibody and T cell responses to HCMV

To mimic the ongoing antigenic exposure that occurs during chronic HCMV infection, we investigated the effect of repeated HCMV exposure on host immune responses. Mice were inoculated with 3–4 doses of HCMV TB40/E or AD169.

Over 90% (22/24) of mice had detectable HCMV-specific IgM following repeated (3–4×) HCMV exposure, regardless of the infecting HCMV strain (Fig. 5a). HCMV-specific IgG was detected in ~73% (16/22) of re-exposed BLT-L mice (Fig. 5b), demonstrating efficient class switching. Plasma samples collected from BLT-L mice repeatedly exposed to TB40/E and with detectable HCMV-specific IgM and IgG possessed neutralizing activity, reducing HCMV infection in vitro by up to 91% (Supplementary Fig. 10). The time from first HCMV exposure to antibody testing differed between singly or multiply exposed mice (1 dose: mean 48 days post-exposure, range 12–125 days and 3–4 doses: mean 77 days post-exposure, range 42–120 days). We cannot therefore exclude that time, in addition to repeated antigen exposure, contributed to class switching. However, TB40/E failed to induce HCMV-specific IgG 125 days after a single exposure (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 4), despite the presence of a detectable HCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response (Fig. 4h).

Fig. 5: HCMV re-exposure further promotes antibody induction and class switching and boosts HCMV specific T cell responses in BLT-L mice.

HCMV-specific (a) IgM and (b) IgG in naïve BLT-L mice (n=5) and following single or 3 or 4 exposures to HCMV TB40/E (IgM n=15 single and 11 re-exposed mice, IgG n= 4 single and 11 re-exposed mice) or AD169 (IgM n=8 single and 13 re-exposed mice, IgG n=4 single and 11 re-exposed mice). Negative (open diamonds) and positive (filled diamonds) standards (STD). Shown is the mean of three technical replicates per mouse. Dashed line: threshold for seropositivity defined from naïve controls. (c) HCMV re-exposure induced IE1-specific TNF-α/IFN-γ double positive CD4+ T cells at the site of inoculation, the human lung implant, and systemically in the liver. Contour plots exampling HCMV-IE1 specific CD8+ T cell IFN-γ production and CD107a degranulation in a BLT-L mouse. (d) CD8+ T cells were isolated from combined tissues of TB40/E (top panels representative of measurements in four independent BLT-L mice) or AD169 (bottom panels representative of measurements in 11 independent BLT-L mice) exposed mice, stimulated and then assessed using intracellular cytokine staining. (e) Summary graph showing background subtracted IE1-specific CD8+ T cell responses (IFN-γ production) in mice receiving repeated inoculations of TB40/E or AD169. (f) Repeated TB40/E (top panels representative of measurements in four independent BLT-L mice) and AD169 (bottom panels representative of measurements in four independent BLT-L mice) exposure induced high frequencies of HCMV-specific CD8+ T cells as determined by pentamer reactivity. Full details of immune reactivity for each multiple exposed BLT-L mouse are indicated in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8.

HCMV infection induces robust and sustained CD4+ T cell responses50. In BLT-L mice inoculated once with HCMV, we were unable to detect HCMV-specific CD4+ T cell responses by ICS (data not shown). However, following repeated HCMV exposure, IE1-specific CD4+ T cell cytokine responses were detected in the human lung implant and liver of BLT-L mice, suggesting repeated antigen exposure induced or augmented antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses (Fig. 5c). IE1-specific CD8+ T cell responses measured by ICS were detected more frequently in repeatedly HCMV exposed mice than in singly exposed BLT-L mice (Fischer’s exact, two-tailed p=0.039) (Fig. 5d,e and Supplementary Tables 4, 7 and 8). Repeated HCMV exposure also induced stronger HCMV-specific CD8+ T cell responses across tissues (Fig. 5d-f and Fig. 4h), producing T cell responses consistent with those reported in chronic human HCMV infection51–54. Increases in pentamer reactivity were also observed. Classically restricted HCMV-specific CD8+ T cells in repeat exposure BLT-L mice approached 2% of all CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5f), between 4–15-fold greater than pentamer frequencies observed following a single exposure (Fig. 4c,d and data not shown). Full details of immune reactivity following repeated HCMV inoculation are provided in Supplementary Tables 7 and 8.

Although BLT-L mice were exposed to multiple doses of TB40/E or AD169, HCMV-DNA was only detected in the human lung implants of 9/18 mice analyzed (2 TB40/E and 7 AD169 exposed BLT-L mice) (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). HCMV-DNA was rarely detected in tissues other than the human lung implants (3/108 tissues analyzed) and was not detected in PB (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10) suggesting strong immune control of HCMV replication in vivo.

DISCUSSION

To extend the breadth of human pathogens that can be studied using humanized mice, we validated two novel models, LoM and BLT-L mice that provide human lung tissue as an in vivo target for human pathogens either without (LoM) or with (BLT-L mice) an autologous systemic human immune system. The engraftment levels of human immune cell types in BLT-L mice are similar to previously reported BLT mice55–57. The subcutaneously implanted human lung tissue expands and develops into lung implants containing human epithelial, endothelial and mesenchymal cells and a vasculature of human origin. Just underneath the skin, the lung implants can be readily accessed and imaged.

Using LoM, we demonstrated that the human lung implants are susceptible to five diverse emerging and clinically relevant human pathogens (MERS-CoV, ZIKV, mycobacteria, RSV and HCMV) without further engineering of the pathogens or the host. However, it is possible that a respiring lung will have different host gene expression profiles that could alter the replication conditions of some pathogens. We next demonstrated that pre-exposure prophylaxis with GCV can effectively control HCMV replication in LoM and performed an in vivo transcriptome analysis of lytic HCMV infection. In the future, transcriptome analyses of the pathogen and host may identify new drug targets and host factors that modulate infection.

HCMV infection in BLT-L mice produced acute virus kinetics that reflected lytic replication, consistent with those reported in humans. With the onset of adaptive humoral and T cell responses, HCMV replication in BLT-L mice declined to background levels. Whereas HCMV-DNA was detected in all exposed LoM, HCMV-DNA was only detected in BLT-L mice during the first two weeks post infection consistent with the strong virological immune control observed. CD8+ T cell responses were detectable in the lung implant as early as 12 days post-inoculation to multiple epitopes including the IE1 and pp65 proteins that are targeted in 50% of human patients58. HCMV-specific T cells were detected systemically in the liver and mouse lung. HCMV-specific CD8+ T cell responses were detected up to 125 days following inoculation. The induction of a systemic antigen-specific immune response in BLT-L mice combined with our data demonstrating the production of human cytokines/chemokines following ex vivo mitogen stimulation of human immune cells isolated from the lung implants, demonstrate the functionality of the human immune cells that repopulate the lung implants.

Mimicking the ongoing antigenic exposure that occurs during chronic HCMV infection, multiple exposures to HCMV resulted in a more robust HCMV-specific antibody and T cell response in BLT-L mice. We readily detected HCMV-specific IgG in BLT-L mice re-exposed to TB40/E or AD169 suggesting that repeat antigen stimulation facilitates human IgG class switching. Multiple HCMV exposures also induced a robust HCMV-specific T cell response. Natural HCMV infection in humans elicits a lifelong CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response and very high reactivity (80–100%) to IE1 and pp65 proteins58, 59. We readily observed IE-1 specific CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues of BLT-L mice repeatedly exposed to HCMV. The magnitude of the HCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response was also increased in BLT-L mice exposed to multiple doses of HCMV and reached levels comparable to humans52–54, 60, 61. The fact that repeated exposure can be used to broaden the immunoprevalence of T cell responses in BLT-L mice, suggests that the model might be useful in vaccine testing.

We did not observe a HCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response or HCMV-specific IgG in cohort F of BLT-L mice despite multiple exposures to TB40/E. This cohort (F) was homozygous across all Class Ia and II alleles (Supplementary Table 3). HCMV induced low levels of IgM but no class switching was observed (Fig. 5a,b, square symbols). Despite a 111–120 day follow-up (post first HCMV exposure), no IE1-specific T cell IFN-γ+/CD107a+ responses were detected (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Table 7). T cells and mDCs in this cohort were functional; specifically, mitogenic stimulation of T cells induced potent cytokine production and degranulation and autologous mDCs induced a mixed-lymphocyte reaction (MLR) when co-cultured with allogeneic PBMC (data not shown). These results suggest that a limited repertoire of HLA presented viral peptides impedes the generation of antigen-specific adaptive immune response in vivo.

BLT-L mice generate antigen-specific humoral and cell-mediated immune responses that control pathogen replication in vivo. These results validate BLT-L mice as an in vivo platform to study the replication, pathogenesis and immunogenicity of human pathogens in the context of a functional systemic human immune system. In this regard, BLT-L mice would support the type of direct, systematic and sophisticated in vivo experimentation that is characteristic of rodent models but cannot be performed in humans. Our results also support BLT-L mice as a model for the in vivo evaluation of human immune therapies, including vaccines, especially for diseases with a strict species tropism.

In summary, we have developed two novel humanized mouse models that support infection and replication of important human viral and bacterial pathogens. LoM and BLT-L mice could be used to study other human pathogens that target the lung (e.g. enterovirus D68, adenovirus type 7, influenza virus, rhinovirus and metapneumovirus), accelerating the in vivo testing of preventative and therepeutic approaches for these agents. Our analysis of implant vascularization using 3D ultrasound acoustic angiography, a non-invasive technique to visualize microvasculature, also suggests that this technology can be used for monitoring angiogenesis and vascularization in other systems. Our results also suggest that developing additional in vivo humanized mouse models for human pathogens with tropism for other tissues might be possible and enhance the precision of humanized mouse models for biomedical research.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

Animal studies were carried out according to protocols approved by the Institutional Use and Care Committee at UNC-Chapel Hill and in adherence to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Generation of humanized mice

Lung-only mice (LoM) were constructed by implanting two pieces (~2–4 mm3) of human fetal lung tissue (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Alameda CA) subcutaneously into the back (right and left back or upper and lower back) of 13–18 week old male and female NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid ll2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ mice (NSG; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) mice creating two separate human lung implants. Engraftment and expansion of the human lung implants was monitored by palpation. After 12 weeks post implantation, the lung implants are readily palpable under the skin of the mice and easy to manipulate for experiments. The lung implants persist for at least 12 months post implantation (last time point analyzed). BLT-Lung (BLT-L) mice were constructed by implanting a sandwich of human fetal thymus-liver-thymus tissue (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Alameda CA) under the kidney capsule of irradiated (200 rads) 10–15 week old male and female NSG mice. Two pieces of autologous human lung tissue (~2–4 mm3) was implanted subcutaneously into the right and left back. Following tissue implantation animals received a bone marrow transplant (via tail vein injection) of autologous liver-derived human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. The non-CD34+ cell fraction was used for 4-digit HLA typing at the HLA-A, B and C loci. Reconstitution of BLT-L mice with human hematopoeitic cells was monitored longitudinally by flow cytometry as previously described13, 14, 62–64. Mice were maintained by the Division of Comparative Medicine at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Ultrasound imaging

Two forms of 3D ultrasound imaging using Vevo 770 (version V3.0.0, VisualSonics, Inc.) acquisition software were performed: B-mode, which is sensitive to different tissue types, and acoustic angiography, which is sensitive to microvasculature. B-mode imaging was used to assess implant volume, while acoustic angiography was performed to visualize implant vasculature. Acoustic angiography has been described in detail previously35, 36. For imaging, LoMs (n=6 mice, 12 human lung implants, 24–35 weeks post-surgery) were anesthetized with vaporized isoflurane (maintained at 2.0–2.5%), the animal’s side and back were depilated with a hair removal cream (Nair), and the ultrasound transducer was coupled to the skin with gel. For acoustic angiography imaging, a microbubble contrast agent (MCA) diluted in saline was administered intravenously through a tail-vein catheter. The lipid-shelled, perfluorocarbon core MCA used here is standard for ultrasound imaging and has been described in this application previously65. Rendering in 3D was performed with Slicer (version 4.8.1).

Human lung implant volume measurement

All image processing and analyses were performed in MATLAB R2017b (version 9.3.0.713579, The Mathworks, Inc). Implant volume was measured from 3D B-mode ultrasound images as follows. First, the center slice of the implant was identified in all three orthogonal planes, and the dimensions of the implant were measured in each central slice, resulting in two measurements of each dimension. The two independent measurements were then averaged to obtain the three orthogonal dimensions (i.e. diameters) of the implant. Implant volume was approximated as that of an ellipsoid of the same size, given by , where a, b, and c are equal to one half the orthogonal dimensions measured.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed as previously described14, 63, 64, 66. Briefly, human lung tissue and tissues collected from NSG, LoM and BLT-L mice were fixed in 4% PFA or 10% formalin, paraffin embedded and cut into 5 µm sections. Prior to primary antibody incubation, antigen retrieval was performed and Ig-binding sites and endogenous peroxidase activity blocked. Tissue sections were developed using the MACH-3™ polymer system (Biocare Medical) and DAB (Vector Laboratories), counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted. Immunofluorescence staining was also performed on 4% PFA or formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections. Following antigen retrieval and blocking with 5% serum (corresponding to the secondary antibody’s host species), 0.1% Triton x100, and 50% Rodent M block (Biocare Medical) in PBS, tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Tissue sections were then stained with fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies followed by DAPI and then mounted. Primary antibodies were directed against human epithelial cells (cytokeratin 19), endothelial cells (CD34), mesenchymal cells (vimentin), hematopoietic cells (CD45), macrophages (CD68), dendritic cells (CD11c), natural killer (NK) cells/NK T cells (CD56), B cells (CD20), T cells (CD3), CD4+ cells (CD4), CD8+ cells (CD8) (Life Sciences Reporting Summary). Primary antibodies directed against mouse endothelial cells (mCD34), epithelial cells (mcytokeratin 19), and hematopoietic cells (mCD45) were used to distinguish the presence of mouse cells (Life Sciences Reporting Summary). Primary antibodies directed against HCMV glycoprotein B, immediate early (IE), early (E) and late (L) proteins were used to detect HCMV positive cells (Life Sciences Reporting Summary). Tissue sections were stained with an anti-ZIKV NS2B antibody to detect ZIKV infected cells. Small pieces of human lung implant tissue collected from MERS-CoV infected LoM were fixed in 10% formalin for >7 days at 4°C, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 µm) and stained with MERS-CoV nucleocapsid polyclonal antibody (Life Sciences Reporting Summary). Tissue sections were also stained with appropriate isotype negative control antibodies. Tissue sections for immunohistochemistry were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse Ci microscope using Nikon Elements BR software (version 4.30.01) with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-Fi2 camera and Brightness and contrast were adjusted on whole images in Adobe Photoshop (CS6). Tissue sections for immunofluorescence were imaged on an Olympus BX61 upright wide field microscope using Improvision’s Velocity software (version X) with a Hammatuse ORCA RC camera. Brightness and contrast were adjusted on whole images using ImageJ software (version 1.51C). In Fig. 2b, d, h and m, pseudocoloring was used to depict MERS-CoV, ZIKV, RSV and HCMV antigen in green and human cell types in magenta. In Fig. 1i and j, Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 1b, where red/green fluorescent images were originally captured the red fluorescent signal was digitally altered to improve visualization by colorblind readers by adjusting the red channel hue by −45 using Adobe Photoshop (CS6).

Analysis of human immune cell reconstitution

Human immune cell reconstitution in the peripheral blood (PB) and tissues of BLT-L mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. MNC were isolated from tissues collected from BLT-L mice by passage through a cell strainer and red blood cell (RBC) lysis as previously described13, 14, 62–64. The human lung implants, mouse lung, liver and female reproductive tract were enzymatically digested prior to passing tissue through a cell strainer. Liver and mouse lung MNC were purified with a Percoll gradient. MNC were isolated from the gastrointestinal tract (small and large intestines) lamina propria layer with an enzymatic digest as previously described. Prior to antibody (Life Sciences Reporting Summary) incubation Ig-binding sites were blocked. The antibody panels were as follows: CD45-APC, CD19-PE, CD3-FITC and CD4-PerCP (Panel 1); CD45-APC, CD19-PE-Cy7, CD33-PE, CD3-FITC, CD4-APC-H7 and CD8-PerCP (panel 2); CD45-APC, CD19-PE-Cy7, CD33-PE, CD3-FITC and CD8-APC-Cy7 (panel 3); CD45-V500, CD3-AlexaFlour 700 or APC-R700, CD4-BV605, CD8-APC-Cy7, CD45RO-FITC or negative control mouse IgG2ak-FITC, CD69-PE or negative control mouse IgG1k, CCR7-PE-Cy7 or negative control rat IgG2aak, HLA-DR-PerCP or negative control mouse IgG2ak-PerCP and CD25-APC or negative control mouse IgG1k-APC (panel 4); CD45-V500, CD19-PE-Cy7, CD3-AlexaFlour 700 or APC-R700, CD4-APC-H7, CD8-FITC, CD45RA-Pacific Blue or negative control mouse IgG1ak-Pacific Blue, CD27-PE or negative control mouse IgG1k-PE, HLA-DR-PerCP or negative control mouse IgG2ak-PerCP and CD38-APC or negative control mouse IgG1k-APC (panel 5). Following antibody incubation, PB was treated with 1X BD FACS lysing solution (BD Biosciences) to remove RBCs. Samples were then washed and fixed with PFA. Data was acquired on a BD LSRFortessa or FACSCanto instrument and analyzed with FACSDiva software (version 6.1.3).

Analysis of human cytokine/chemokine production

MNC were isolated from BLT-L mouse (n=6 mice and 12 lung implants, represents two experiments) human lung implants. Human lung implants were enzymatically digested prior to passing tissue through a cell strainer and MNC were purified with a Percoll gradient. MNC were pooled from the lung implants of 3 mice (n=6 lung implants) and cultured (7.8×105 cells/well of a 48 well plate) for 4 h in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (untreated control, 1 well per experiment) or media supplemented with PMA (25 ng/ml)/Ionomycin (250 ng/ml) (1 well experiment 1 and 2 wells experiment 2) or with LPS (100 ng/ml, E. coli O55:B5, Sigma) (1 well per experiment). Cell culture supernatant was collected at 4 h. Cells were also isolated from the human lung implant of LoMs (n=1 mouse, 2 human lung implants, represents one experiment) following a 24 h enzymatic digest (1% Protease XIV/0.01% DNAse solution diluted 1:19 in F12 media supplemented with Amphotericin and Gentamicin) at 4°C. Cells (1×106 cells per well) were cultured overnight in bronchial epithelial growth medium (BEGM)67 supplemented with 10% FBS in wells of a collagen coated 48 well plate (5.6 ug/cm2 human placental collagen type IV). Wells were washed to remove non-adherent cells and then cells cultured in BEGM + 10% FBS media alone (untreated control) or supplemented with LPS (100 ng/ml, E. coli O55:B5, Sigma) (3 wells per condition/lung implant). Cell culture supernatant was collected at 24 h. Plasma was isolated from PB collected from BLT-L mice (n=10 mice, represents three experiments) 3 days prior to and 4 days post HCMV-TB40/E (2.2×106 TCID50) inoculation into human lung implants. Human cytokine/chemokine levels in cell culture supernatant and plasma were measured using a Milliplex MAP kit (Millipore #HCYTMAG-60K-PX41, limit of detection: 3.2 pg/ml) on a Luminex MagPix instrument. Samples were run undiluted in singular wells. The following 41 human analytes were measured: Eotaxin/CCL11, FGF-2, Flt-3 ligand, Fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFN-α2, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1rα, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, IP-10, MCP-1, MCP-3, MDC (CCL22), MIP-1α, MIP-1β, PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB/BB, RANTES, sCD40L, TGF-α, TNF-α, TNF-β, VEGF and EGF. BEGM contains human EGF, therefore, EGF levels were not reported.

MERS-CoV production and analysis of infection

Stocks of the wild-type HCoV-EMC/2012 of MERS-CoV (originally provided by Dr. Bart Haagmans, Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam, The Netherlands at passage 8) were prepared and virus titers determined on Vero CCL81 cells (ATCC) under Biosafety Level (BSL) 3 conditions as previously described1. MERS-CoV (104 or 105 PFU per human lung implant) was inoculated in the human lung implants of anesthetized LoM via direct injection (50 µl volume) and human lung implants harvested at 48 h post-infection (104 PFU: n=2 mice, 4 human lung implants and represents one experiment, 105 PFU: n=4 mice, 8 human lung implants and represents two experiments). To determine tissue MERS-CoV titers, pieces of human lung implant were weighed, homogenized and then stored at −80°C.

ZIKV production and analysis of infection

Stocks of Zika virus (ZIKV) strain H/PF/2013 were prepared on Vero CCL81 cells (ATCC). Virus titers were determined by quantifying the number of ZIKV-RNA copies with real-time PCR (3,208 ZIKV-RNA copies/FFU based on real-time PCR analysis of ZIKV stocks titered on Vero CCL81 cells as previously described 68). The human lung implants of LoM were injected with 104 or 103 FFU ZIKV (n=2 LoM, 4 human lung implants, per dose and represents one experiment) (100 µl volume per implant). Mice were necropsied 48 h post-inoculation. Human lung implants were processed into a single cell suspension as described above. Cell-associated ZIKV-RNA levels were measured using a quantitative real-time PCR assay using TaqMan® RNA to-CT 1-step kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the forward and reverse primers and the TaqMan® probe for PCR amplification and detection of ZIKV RNA were: 5′-CCGCTGCCCAACACAAG −3′, 5′-CCACTAACGTTCTTTTGCAGACAT −3′, and 5′-FAM-AGCCTACCT/ZEN/TGACAAGCAGTCAGACACACTCAA-Q-3′, respectively69.

BCG production and analysis of infection

Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Pasteur was grown at 37° C in liquid Middlebrook 7H9 medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, 0.5% glycerol, and 1X ADS (>0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% glucose, 0.85% NaCl). The human lung implants of anesthetized LoM were injected with 4×104 or 4×102 CFU BCG (n=3 LoM, 3 human lung implants, per dose and represents one experiment) (100 µl volume per lung implant). Mice were necropsied 28 days post-exposure. At necropsy, one-half of each human lung implant was homogenized in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, 100 ng/ml cycloheximide and 50 μg/ml carbenicillin. The diluted homogenate was then plated onto 7H10-ADS-glycerol plates with 10 mg/ml cycloheximide for CFU enumeration. The total number of CFU per human lung implant was calculated by multiplying the number of CFU ×2.To visualize BCG, a LoM injected with 105 CFU BCG via intra-human lung injection (100 µl volume) was necropsied 28 days post-exposure and small pieces of human lung implant tissue were fixed in 4% PFA, paraffin embedded and sectioned (5 µm). Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast staining was performed with carbol fuchsin and methylene blue. Tissue sections were imaged on an Olympus BX61 microscope with a RETIGA 4000R camera and brightness and contrast adjusted in Adobe Photoshop (CS6).

RSV production and analysis of infection

Recombinant RSV strain A2 expressing GFP has been previously described70. RSV (2.5×105 TCIU per human lung implant) was directly injected (100 µl volume) into the human lung implants of anesthetized LoM (n=3 mice, 6 human lung implants and represents two experiments). At necropsy (4 days post-exposure), human lung implants were harvested, enzymatically digested and passed through a cell strainer. RSV infection and replication were evaluated by measuring GFP expression with flow cytometry. Data was collected on a BD LSRFortessa instrument and analyzed with BD FACSDiva software (version 6.1.3). For immunofluoresence, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were probed with an anti-RSV antibody and an anti-cytokeratin 19 antibody or anti-β-tubulin IV antibody (Life Sciences Reporting Summary) to detect cilia of ciliated cells. Club cells were detected with an anti-CC10 antibody. Alcian-blue periodic acid-Schiff (AB-PAS) staining was peformed to analyzed mucus production in human lung implants of naive control and RSV-infected LoM. Sections were imaged on an Olympus BX61 upright wide field microscope with a Hammatuse ORCA RC camera, Olympus VS120 virtual slide scanning system with an Allied Vision Pike 5 CCD progressive scan camera, or a Leica DM IRB epifluorescent microscope with a Q-Imaging Retiga Camera. Image acquisition was performed with using Improvision’s Volocity (version 6.3) or QImaging Q Capture software (version 2.81) and brightness/contrast adjusted on whole images using ImageJ software (version 1.51C).

HCMV production and infection of mice

Anesthetized LoM and BLT-L mice were exposed to HCMV by direct injection of HCMV TB40/E (4.25×105-6×106 TCID50)45, 71, ADrUL131 (2.4×105 TCID50)48 or AD169 (1.1–6×106 TCID50)72 into the human lung implants. For the TB40/E time course experiment in LoM, human lung implants were harvested at days 4 (n= 2 mice, 4 human lung implants), 7 (n= 2 mice, 4 human lung oganoids), 14 (n=3 mice, 5 human lung implants) and 21 (n=2 mice, 3 human lung implants) post-exposure and represents one experiment. The TB40/E infected human lung implant analyzed at 52 days post-exposure in Fig. 2l represents an additional LoM. For the GCV pre-exposure prophylaxis experiment, LoM (n=3 mice, 6 human lung implants) were administered 100 mg/kg GCV daily for 17 days by intraperitoneal injection and inoculated with HCMV TB40/E expressing luciferase (4.25×105 TCID50)45 after two GVC doses. Untreated LoM (n=5 mice, 7 human lung implants) inoculated with HCMV TB40/E expressing luciferase (4.25×105 TCID50) served as a control. Luciferase expression was measured on anesthetized mice with an IVIS Lumina Optical System following intraperitoneal injection of D-Luciferin (15 mg/kg) on days 4, 11, 14, 21 and 25 post-exposure. For the AD169 time course experiment in LoM, human lung implants were harvested at days 4 (n= 2 mice, 3 human lung implants), 7 (n= 2 mice, 4 human lung oganoids), 14 (n=2 mice, 4 human lung implaesthetized LoM and BLT-L mice were exposed nts), 21 (n=2 mice, 4 human lung implants) and 28 (n=2 mice, 4 human lung implants) post-exposure and represents one experiment. To evaluate HCMV replication over time in human lung implants, HCMV TB40/E expressing luciferase (4.25×105 TCID50)45 was inoculated into the human lung implants of human donor matched LoM (n=3 mice, 6 human lung implants) and BLT-L mice (n=3 mice, 6 human lung implants). Luciferase expression was measured on anesthetized mice with an IVIS Lumina Optical System following intraperitoneal injection of D-Luciferin (15 mg/kg) on days 4, 7, 11, 14, and weeks 4 and 5 following HCMV exposure. Baseline luminescence in human lung implants was determined in LoM and BLT-L mice prior to HCMV exposure. Data represents one experiment in LoM and BLT-L mice. To evaluate the HCMV-specific immune response after multiple virus doses, BLT-L mice received three (administered one month and then two weeks apart) or four (administered two weeks apart) inoculations of HCMV TB40/E or AD169. PB and tissues were collected from LoM and BLT-L mice and processed as described previously and above. In Fig. 2k, human lung implant cells isolated from TB40/E infected LoM were also percolled. HCMV-DNA levels in peripheral blood and tissue cells were measured by real-time PCR analysis as previously described73. Data represents five experiments.

HCMV transcriptome analysis

Total RNA was extracted from human lung implants harvested from HCMV TB40/E infected LoM using Trizol following tissue homogenization and combined. Data represents one experiment. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was depleted using RiboMinus™ (Thermo Fisher). Double-stranded cDNA ((ds)cDNA) was generated from rRNA-depleted total RNA using the SMARTer PCR cDNA synthesis kit (Takara). Viral-specific (ds)cDNA was then captured using custom designed biotinylated probes spanning both strands of the entire HCMV genome (Agilent). After extensive washing, the bound (ds)cDNA was eluted from the capture probes, and next generation sequencing (NGS) libraries generated from the eluted (ds)cDNA using the Nextera XT trans-fragmentation kit (Illumina). The resulting library was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 using 2×100 bp paired end reads. High quality reads were aligned to the HCMV genome, and viral expression was quantified in read per kilobase per million (rpkm) using Cuffdiff (Cufflinks, version 2.2.1).

Detection of IgM and IgG antibodies to HCMV

Antibodies to HCMV in plasma were measured using either a HCMV IgM or IgG enzyme immunoassay test kit (Genway, CA USA). HCMV IgM or IgG Index = average OD of triplicate samples / (calibrator OD × lot specific Calibrator Factor), as per manufacturer’s protocol. Randomly selected samples were re-run to assess intra-assay variability. All tests showed low inter- and intra-assay variability (<10% CV). A seropositive sample was designated as having either a HCMV IgM or IgG index > measured index from naïve BLT-L mice (n=5). To analyze the HCMV neutralizing activity in plasma of HCMV-exposed BLT-L mice, the plasma of a naïve BLT-L mouse (n=1) and BLT-L mice exposed repeatedly to TB40/E (3–4×, n=6 mice) was heated at 56°C for 15–20 min then diluted 1:60 in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS (heat-inactivated) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Diluted plasma was incubated with HCMV-TB40/E-RFP for 1 h at 37°C. The virus mixture was added to ARPE-19 cells (MOI 5) in quadruplicate wells of a 24 well plate and incubated for 2 h at 37°C at which time virus containing media was removed and fresh media added. After 72 h, cells were fixed, stained with DAPI, and the number of RFP+ cells counted. Data represents one in vitro infection experiment.

Human antigen presenting cell production

Autologous human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCL) or myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) were generated from each human tissue donor analyzed (eight donors total) and used as antigen presenting cells (APCs) in ELISpot and ICS assays. BLCLs were derived from the human fetal liver CD34-negative fraction or from human CD19+ cells positively selected from BLT-L tissue cells using CD19 microbeads (Miltenyi), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were infected with EBV B95–8 overnight and maintained at 37° C until transformation (8–10 weeks later). BLCLs were propagated in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. mDCs were generated from human fetal liver-derived CD34+ cells magnetically selected using CD34 microbeads (Miltenyi). Purified CD34+ were plated at a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml in IMDM medium supplemented with 10% of FBS, 100 ng/ml GM-CSF, 2.5 ng/ml TNF-α, 50 ng/ml Flt-3L, 2.5 ng/ml SCF and 10 ng/ml IL-4 (R&D Systems). Medium was refreshed every 3 days. Maturation of DCs was initiated three days before planned T cell assays using IMDM supplemented with 10% FBS, 800 U/ml GM-CSF, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, 1 µg/ml PEG-2, 10 ng/ml IL-1β, 400 U/ml IL-4 and 100 ng/ml IL-6 (R&D Systems). Autologous BLCLs (CD19-PerCP positive) or mDCs (CD11c-PE positive) were phenotyped by flow cytometry using the following antibodies: pan-HLA-I Class-Pacific Blue, HLA-E-PE, and HLA-DR-PE-Cy7; CD80-PE-Cy7, CD83-APC and CD86-PE-Cy7 (Life Sciences Reporting Summary). APC irradiation and peptide pulsing: Peptides were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys. Autologous BLCLs or matured mDCs were irradiated (5000 rad), then pulsed for 60 min at 37° C with either individual peptides (1–2.5 µg) or a pool of 69 overlapping peptides (12–18 aa overlapping by 10aa) spanning the CMV IE1 protein (0.5 µg of each peptide) for 60min. Cells were then washed 3×, counted before adding to T cell assays. The following individual peptides used in these studies include pp65(495–504) NLVPMVATV (A*02:01) and pp65(123–131) IPSINVHHY (B*35:01)

Ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot assay

3×105 BLT-L tissue cells were co-cultured with peptide-pulsed, autologous BLCL in a 1:2 ratio in a 200 µl for 18–20 h at 37°C/5%CO2. Assays were performed in triplicate or quadruplicate. Tissue cells co-cultured with mock-pulsed BLCLs served as a negative control and tissue cells co-cultured with 50 ng/ml PMA + 500 ng/ml Ionomycin served as a positive control. ELISpot assay development and spot counting was performed as described previously74. ELISpot data were expressed as the mean spot forming units (SFU) per million CD3-positive T cells ± SEM. Positive T cell responses were defined as those > 50 SFU/million CD3 T cells and ≥ 2× mean of negative control wells. While not a criteria for positivity, across all assays in all cohorts, the average of the mock-pulsed BLCLs was <24.6 SFU/input cells, as detailed in Supplementary Table 5.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Peptide-pulsed autologous BLCL (2:1) or mDCs (1:10) were irradiated (5000 rad) then combined with filtered (0.45 µm), total or CD8-microbead (Miltenyi) selected tissue suspensions (minimum 1×106 cells). Panels measured either IFN-γ/CD107a or IFN-γ/TNF-α. For measurement of IFN-γ/CD107a, co-cultures were immediately stained with CD107a-APC, monensin added then cultured 6 h or overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Next, cells were stained with Zombie NIR viability dye at RT 20 min, then labelled with CD3-BV421; CD4-BV650; CD8-BV510; PerCP-conjugated CD14, 16, 19, and 56 (dump channel) at RT 15 min. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained intracellularly with either IFN-γ-PE. For detection of IFN-γ/TNF-α, monensin/Brefeldin A was added to co-cultures which were then incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. The next day, cells were stained with Zombie NIR and lymphocyte markers are described above. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained intracellularly with IFN-γ-FITC and TNFα-PE/Dazzyle™594 (Life Sciences Reporting Summary). In all assays, fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls were used for gating of CD107a, cytokine and CD8 reactive populations. For compensation, beads were used for all colors excepting Zombie. For Zombie, live and dead (heat inactivated) cells were mixed and Zombie stained to generated positive and negative populations. All cells were acquired using an LSRFortessa flow cytometer and data analyzed with FlowJo Software (version 10) (gating strategies illustrated in Supplementary Figure 11a,b). T cell responses were expressed as frequency of either CD8+ or CD4+ T cell lymphocytes. A HCMV-specific T cell response met the following criteria: >10000 CD4 or CD8 positive events, > 0.01% of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells; a minimum of 10 events in the IFN-γ /CD107a or IFN-γ /TNF-α double-positive gate, 2× no-peptide control.

Multimer reactivity

PE- or APC-conjugated pentamers (ProImmune) were used for staining of total or CD8-microbead (Miltenyi Biotec) selected tissue (liver or/and human lung) suspensions. In all assays, minimum 1×106 cells were used and cells were filtered (0.45 µm) prior to staining. Cells were stained with Zombie 2 viability dye at RT for 20 min, followed by staining with pentamer (as per manufacturer’s instructions) at RT for 15 min. After washing, CD3-BV421, CD4-BV650, CD8-BV510, PerCP-conjugated CD14, 16, 19, and 56 (dump channel) were added and cells incubated on ice for 15 min. Cells were washed and fixed. All cells were acquired using an LSRFortessa flow cytometer and data analyzed with FlowJo Software (version 10) (gating strategy illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 11c). A pentamer reactive population met the following criteria: >3000 CD8 positive events, greater than 2× control pentamer (HLA-mismatched, non-HCMV), greater than 0.01% of all CD8+ T cells, > 10 events in the pentamer gate and no evidence of non-specific staining in non-CD8+ T cell gates.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical test used is indicated below and in the figure legends and/or the Results. The definition of center, and dispersion and precision measures is indicated in the figure legends and/or the Results. The exact value of n and what n stands for is in the figure legends and methods details. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (version 6, 7 or 8) or R (version 3.4.4). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. No randomization was used to determine how samples/animals were allocated to experimental groups or processed. Investigators were not blinded to group allocations or when assessing outcomes. For all statistical comparisons p values <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical tests were exact. A two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used to compare luciferase activity in the human lung implants of LoM and BLT-L mice (Fig. 4a) and human immune cell levels in the mouse lung and human lung organoids of BLT-L mice (Supplementary Fig.6). A two-tailed Fischer’s exact test was used to compare the incidence of HCMV-specific human IgM, IgG and CD8+ T cells in BLT-L mice exposed to one or multiple doses of HCMV (Fig. 4 and 5). Human cytokine and chemokine levels pre and post HCMV inoculation were compared with a two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI103311 (NJM), AI123811 (NJM), AI110700 (RSB), AI100625 (RSB), P30 AI0227763 (NG), AI113736 (RJP), T32 HL069768 (IGN), AI123010 (AW), AI111899 (JVG), AI140799 (JVG), MH108179 (JVG), CA189479 (PAD), CA170665 (PAD) and the North Carolina University Cancer Research Fund (NJM). This work was also supported by the UNC Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30 AI050410). We thank K. Arend for the generation of HCMV virus stocks used in these experiments. We thank P. Collins and M. Peeples for recombinant RSV expressing GFP and C. O’Connor for recombinant HCMV TB40/E expressing luciferase. We thank G. Clutton for input on the analysis of antigen specific T cell responses. The authors thank members of the Garcia laboratory for technical assistance. We thank technicians at the UNC Animal Histopathology Core, The Marsico Lung Institute Tissue and Procurement Core, and the Department of Comparative Medicine. We also thank J. Schmitz and technicians at the UNC Clinical Microbiology/Immunology Laboratories. We thank J. Nelson and technicians at the UNC CFAR Virology Core Laboratory and K. Mollan at the UNC CFAR Biostatistics Core. The authors thank M.T. Heise, L.J. Picker, and J.P. Ting for manuscript review and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

P.A.D. is an inventor of the acoustic angiography imaging technique, and a co-founder of SonoVol, Inc., a company which has licensed this patent.

Data Availability

The data generated are available from corresponding authors on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cockrell AS et al. A mouse model for MERS coronavirus-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nature microbiology 2, 16226 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison TE & Diamond MS Animal Models of Zika Virus Infection, Pathogenesis, and Immunity. Journal of virology 91 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safronetz D, Geisbert TW & Feldmann H Animal models for highly pathogenic emerging viruses. Current opinion in virology 3, 205–209 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitt K et al. Zika viral infection and neutralizing human antibody response in a BLT humanized mouse model. Virology 515, 235–242 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford LB, Streblow DN, Hakki M, Nelson JA & Caposio P Humanized mouse models of human cytomegalovirus infection. Current opinion in virology 13, 86–92 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor G Animal models of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Vaccine 35, 469–480 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta UD & Katoch VM Animal models of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 85, 277–293 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonseca KL, Rodrigues PNS, Olsson IAS & Saraiva M Experimental study of tuberculosis: From animal models to complex cell systems and organoids. PLoS pathogens 13, e1006421 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickles RJ & DeVincenzo JP Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its propensity for causing bronchiolitis. The Journal of pathology 235, 266–276 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlman RL. Mouse models of human disease: An evolutionary perspective. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Shultz LD, Brehm MA, Garcia-Martinez JV & Greiner DL Humanized mice for immune system investigation: progress, promise and challenges. Nature reviews. Immunology 12, 786–798 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia JV Humanized mice for HIV and AIDS research. Current opinion in virology 19, 56–64 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahl A et al. A cluster of virus-encoded microRNAs accelerates acute systemic Epstein-Barr virus infection but does not significantly enhance virus-induced oncogenesis in vivo. Journal of virology 87, 5437–5446 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melkus MW et al. Humanized mice mount specific adaptive and innate immune responses to EBV and TSST-1. Nature medicine 12, 1316–1322 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Islas-Ohlmayer M et al. Experimental infection of NOD/SCID mice reconstituted with human CD34+ cells with Epstein-Barr virus. Journal of virology 78, 13891–13900 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bente DA, Melkus MW, Garcia JV & Rico-Hesse R Dengue fever in humanized NOD/SCID mice. Journal of virology 79, 13797–13799 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith MS et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor reactivates human cytomegalovirus in a latently infected humanized mouse model. Cell host & microbe 8, 284–291 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crawford LB et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Induces Cellular and Humoral Virus-specific Immune Responses in Humanized BLT Mice. Scientific reports 7, 937 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang LX et al. Humanized-BLT mouse model of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 3146–3151 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockrell AS et al. Mouse dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is not a functional receptor for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Journal of virology 88, 5195–5199 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman CM, Matthews KL, Goicochea L & Frieman MB Wild-type and innate immune-deficient mice are not susceptible to the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. The Journal of general virology 95, 408–412 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Torres F, Nochi T, Wahl A, Garcia JV & Denton PW Hypogammaglobulinemia in BLT humanized mice--an animal model of primary antibody deficiency. PloS one 9, e108663 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nochi T, Denton PW, Wahl A & Garcia JV Cryptopatches are essential for the development of human GALT. Cell reports 3, 1874–1884 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudek TE et al. Rapid evolution of HIV-1 to functional CD8(+) T cell responses in humanized BLT mice. Science translational medicine 4, 143ra198 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brainard DM et al. Induction of robust cellular and humoral virus-specific adaptive immune responses in human immunodeficiency virus-infected humanized BLT mice. Journal of virology 83, 7305–7321 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J, Chu H, Chan JF & Yuen KY Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: virus-host cell interactions and implications on pathogenesis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Frumence E et al. The South Pacific epidemic strain of Zika virus replicates efficiently in human epithelial A549 cells leading to IFN-beta production and apoptosis induction. Virology 493, 217–226 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu S, DeLalio LJ, Isakson BE & Wang TT AXL-Mediated Productive Infection of Human Endothelial Cells by Zika Virus. Circulation research 119, 1183–1189 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamel R et al. Biology of Zika Virus Infection in Human Skin Cells. Journal of virology 89, 8880–8896 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franks TJ et al. Resident cellular components of the human lung: current knowledge and goals for research on cell phenotyping and function. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 5, 763–766 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sousa AQ et al. Postmortem Findings for 7 Neonates with Congenital Zika Virus Infection. Emerging infectious diseases 23, 1164–1167 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunha BA Cytomegalovirus pneumonia: community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent hosts. Infectious disease clinics of North America 24, 147–158 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon CL et al. Tissue reservoirs of antiviral T cell immunity in persistent human CMV infection. The Journal of experimental medicine 214, 651–667 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyon SM & Rossman MD Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Microbiology spectrum 5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gessner R et al. High-resolution, high-contrast ultrasound imaging using a prototype dual-frequency transducer: in vitro and in vivo studies. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control 57, 1772–1781 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]