Abstract

Background and Purpose

Non contrast-enhanced (CE) magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) techniques have experienced a renaissance due to the known correlation between the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents and the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, and also the deposition of gadolinium in some brain regions.

The purpose of this study was to assess the diagnostic performance of ungated non-CE radial quiescent-interval slice-selective (QISS)-MRA of extracranial supra-aortic arteries in comparison with the conventional CE-MRA in patients with clinical suspicion of carotid stenosis.

Material and Methods

In this prospective study, both MRA-pulse sequences were performed in thirty-one consecutive patients (median 68.8 years, 19 males). For the evaluation, the cervical arterial system was divided into 35 segments (right and left side). Three blinded reviewers separately evaluated these segments. An ordinal scoring system was used to assess the image quality of arterial segments and the stenosis grading of carotids.

Results

Overall venous contamination in QISS-MRA was rated as “none” by all readers in 84.9% and in CE-MRA in 8.1% of cases (p<0.0001). The visualization quality of arterial segments was considered good to excellent in 40.2% for the QISS-MRA and in 52.2% for the CE-MRA (p<0.0001). The diagnostic accuracy of ungated QISS-MRA concerning the stenosis grading showed a total sensitivity and specificity of 85.7% and 90.0%, respectively.

Conclusion

Ungated QISS-MRA can be used clinically as an alternative to CE-MRA without a significantly different image quality or diagnostic accuracy for detection of carotid stenosis at 1.5 Tesla.

Introduction

Extracranial internal carotid arteries (ICA) stenosis is a common disease and a risk factor for an ischemic stroke [1]. Atherosclerosis is the main cause of an ICA stenosis [2, 3]. Typical risk factors for atherosclerosis are hypertension, history of smoking, diabetes, obesity and elevated low density cholesterol level [4, 5]. An ICA stenosis can be treated either conservatively, for example with risk factor control and best medical therapy, or invasively (endarterectomy or stent-angioplasty) [3, 6]. The decision on the preferred method for the treatment of an ICA stenosis depends on several factors. Besides the existence of symptoms, the grade of the stenosis is an important factor [3, 7]. Therefore, determination of the stenosis grade is essential to assess the appropriate treatment.

Duplex ultrasound (DUS), computed tomography angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are the non-/minimal-invasive imaging modalities to evaluate the ICA [8]. The accuracy of a DUS-examination of the carotids depends on the experience of the investigator so that a second imaging modality is required in most cases. Additionally, extensive calcified plaques of the vessel wall impair accurate assessment of the grade of stenosis difficult due to acoustic shadowing. Contrast-enhanced MRA (CE-MRA) using gadolinium-based contrast agent is an often used minimally-invasive method for grading of an ICA stenosis. In patients with renal insufficiency gadolinium-based contrast agent should be applied with caution [9]. For these patients, the CE-CTA is not suitable alternative due to potential nephrotoxic iodine contrast medium. Furthermore the deposition of gadolinium-based contrast agent in the brain of patients even with a good renal function is a subject of ongoing discussions and investigations to use non-CE magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques [10, 11]. The above concerns about MRI contrast agent safety have spurred new developments in non-CE MR techniques with reliable clinical results [12-14]. The 2D/3D time of flight angiography (TOF-MRA) is a commonly used non-contrast-enhanced approach for MRA of the extracranial carotid arteries. However, both techniques are time-consuming compared to CE-MRA. The image quality and anatomical coverage provided by TOF-MRA is inferior to that of CE-MRA [15, 16]. Moreover, TOF is more sensitive to respiratory and flow artifacts and has a tendency to overestimate stenoses [14].

Recently, a new technique for non-CE MRA of arteries was presented. The so called quiescent-interval slice-selective (QISS) [17] MRA was first used to examine the peripheral arteries and showed promising results [13]. Recent advances in QISS technique facilitate non-CE MRA of other vessels [18], in particular extracranial carotid arteries at 3 T [19, 20]. The aim of this study was to test the feasibility of an ungated radial implementation of QISS-MRA at 1.5 Tesla and to assess its diagnostic performance for imaging the extracranial carotid arteries compared against the clinical standard technique of CE-MRA. To simplify the sentences below, the ungated non-CE radial QISS-MRA is abbreviated to ungated QISS-MRA.

Material and Methods

Patients

Patients were included in this prospective study, which had been consecutively referred to our center from May to September 2018 for clinically indicated extracranial MRA of the supra-aortic arteries. The medical history of all patients was reviewed to find out the reason of the clinical requested MRI examination of the carotid arteries. The study exclusion criteria were history of carotid stenting, renal insufficiency that precluded the administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent, as indicated by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m² [21], other contraindications for gadolinium-based contrast agent and contraindications for MRI.

This study was performed according to the protocol (No. D 508/18) approved by the institutional ethics committee and in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Our patients gave informed consent in written form.

Demographic data of study population

Pertinent demographic data (age, weight, body mass index (BMI) at MRI examination date and gender) of study population were recorded.

MRA imaging

Imaging was performed on a 1.5 T MRI system (MAGNETOM Aera, XQ gradients, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) having a maximum gradient strength of 45 mT/m and a maximum slew rate of 200 mT/m/ms. The MRI system was operated by the latest software (Syngo version E11C). The MR signal was received using a 20-element head coil, a four-element neck coil, and a 32-element array coil placed on the upper chest (Siemens GmbH, Erlangen, Germany).

The ungated QISS-MRA was performed in all subjects without electro-cardiogram (ECG) gating using a 2D single-shot radial flow compensated fast low angle shot (FLASH) readout. Flow compensation minimized blood flow artifacts.

The breath-hold first-pass CE-MRA was performed after ungated QISS-MRA in all subjects with the administration of 0.1 mmol/kg body weight of gadolinium-based contrast agent (Gadovist® 1.0 mmol/ml, Gadobutrol, Bayer Vital GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany) in an antecubital vein at a rate of 2 mL/s. After CE-MRA examination the CE-MRA images were subtracted from a native MRA-image (mask), which was acquired with the same parameters before contrast agent injection. The imaging parameters for both MRA pulse sequences are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Imaging parameters for ungated quiescent-interval single-shot (QISS) and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) sequences.

| Parameter | Ungated QISS-MRA | CE-MRA |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging mode | 2D | 3D |

| FLASH TR/TE (ms) | 15.0/4.7 | 3.09/1.2 |

| QISS sequence TR (ms) | 1100.8 | -- |

| Acquisition matrix (Px) | 384 × 384 | 512 × 512 |

| Acquisition pixel (mm2) | 0.5 × 0.5 | 0.6 × 0.6 |

| In-plane interpolation | On | On |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Number of slices | 128 | 80 |

| Slice distance factor (%) | −33 | 20 |

| Number of averages | 1 | 1 |

| Receiver bandwidth (Hz/Px) | 303 | 540 |

| Flip angle (°) | 30 | 30 |

| Slice orientation | Tilted transversal to coronal (45° tilt) | Coronal |

| k-space trajectory | Radial | Cartesian |

| Number of radial projections | 204 | -- |

| Number of shots per slice | 3 | -- |

| Phase oversampling (%) | 0 | 40 |

| Filter | distortion correction (2D); prescan normalizer | distortion correction (3D); prescan normalizer |

| B0 shim mode | Heart | Tune-up |

| Asymmetrical echo | Off | On |

| RF pulse type | Normal | Normal |

| Gradient mode | Fast | Fast |

| RF spoiler | On | On |

| iPAT modus (acceleration factor/number of reference lines) | --- | 2 /24 |

| Partial Fourier (phase and slice) | -- | 6/8th |

| Venous saturation slab thickness (mm) | 100 | -- |

| Distance between venous saturation and imaging slab (mm) | 10 | -- |

| TI (ms) | 530 | -- |

| Acquisition time (min) | 7:03 | 0:20 |

TR = repetition time, TE = echo time, RF = radiofrequency, iPAT = integrated parallel imaging technique, TI = time from in-plane and venous saturation to the acquisition of central k-space (ky=0).

Image analysis

Three blinded board-certified radiologists (S. P., M. H., U. J.K.) with each at least 7 years of experience in neuroradiology and MRA evaluated all MRI data sets independently and during separate reading sessions. Source images and rotating maximum intensity projection (MIP) images were reviewed. The image analysis was performed on a workstation (IMPAX EE, Agfa HealthCare GmbH, Bonn, Germany).

The overall diagnostic image quality of MR images was rated by using a scoring scale of 1–3 with respect to the arterial signal and presence of artifacts (including parallel acquisition reconstruction artifact, motion artifact, and/or noise):

Grade 1: Poor image quality, inadequate arterial signal and/or the presence of a significant amount of artifacts/noise impairing the diagnosis.

Grade 2: Good image quality sufficient for diagnosis, adequate arterial signal, and/or mild-to-moderate amounts of artifacts/noise not interfering with diagnosis.

Grade 3: Excellent image quality for highly confident diagnosis, good arterial signal, and no-to-minimal amount of artifacts/noise.

Potentially contaminating venous signal was evaluated on a scale of 0-3:

Grade 0: None.

Grade 1: Minimal, allowing interpretation with a high degree of diagnostic confidence.

Grade 2: Moderate, exceeding acceptable degree and limiting diagnostic confidence.

Grade 3: Severe, markedly limiting diagnostic confidence.

The cervical arteries were divided into 35 segments (Table 2). The continuity, visibility, and edge sharpness of these segments were assessed in all subjects. Visualization of each segment was assessed by using a scoring scale of 1-4:

Grade 1: Non-diagnostic, barely visible lumen rendering the segment.

Grade 2: Fair, ill-defined vessel borders with suboptimal image quality for diagnosis.

Grade 3: Good, minor inhomogeneities not influencing vessel delineation.

Grade 4: Excellent, sharply defined arterial borders with excellent image quality for highly confident diagnosis.

Table 2:

Evaluation of ungated QISS-MRA versus CE-MRA based on the introduced 3-, 4-, and 5-point scale scoring systems in the section “image analysis” using Wilcoxon-signed-rank test.

| Variable | QISS-MRA | CE-MRA | p-value (QISS-MRA vs. CE-MRA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median [min, max] | |||

| Image quality | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.46 |

| Venous contamination | 0 [0, 2] | 1 [0, 3] | <0.0001 |

| Global quality of arterial visualization | 2 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | <0.0001 |

| Stenosis grading | |||

| Right | 1 [1, 5] | 1 [1, 5] | 0.64 |

| Left | 1 [1, 5] | 1 [1, 5] | 0.73 |

| Segmental quality of arterial visualization | |||

| Right side | |||

| Origin of brachiocephalic artery (1) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | <0.0001 |

| Origin of CCA (2) | 3[1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | <0.0001 |

| CCA (3) | 3 [1, 4] | 4 [1, 4] | 0.03 |

| Bifurcation of CCA (4) | 3 [1, 4] | 4 [1, 4] | 0.002 |

| ICA-C1 (cervical) (5) | 3 [1, 4] | 4 [1, 4] | 0.011 |

| ECA (superior thyroid artery) (6) | 1 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.007 |

| ECA (lingual artery) (7) | 1 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.0002 |

| ECA (facial artery) (8) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.0003 |

| ECA (occipital artery) (9) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.043 |

| ECA (posterior auricular artery) (10) | 1 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 4] | 0.16 |

| ECA (suprafacial temporal artery) (11) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.002 |

| ECA (maxillary artery) (12) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.001 |

| ECA (ascending pharyngeal artery) (13) | 1 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 4] | 0.39 |

| Origin of subclavian artery(14) | 2 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | <0.0001 |

| Origin of vertebral artery (V0) (15) | 2 [1, 4] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.19 |

| V1 (preforaminal) (16) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.064 |

| V2 (foraminal) (17) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.51 |

| V3 (atlantic, extradural or extra spinal) (18) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.097 |

| Left side | |||

| Origin of CCA (1) | 2 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.0003 |

| CCA (2) | 3 [2, 4] | 4 [1, 4] | 0.01 |

| Bifurcation of CCA (3) | 3 [2, 4] | 4 [1, 4] | 0.008 |

| ICA-C1 (cervical) (4) | 3 [1, 4] | 4 [1, 4] | 0.02 |

| ECA (superior thyroid artery) (5) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.02 |

| ECA (lingual artery) (6) | 1 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.002 |

| ECA (facial artery) (7) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | <0.0001 |

| ECA (occipital artery) (8) | 2 [1, 4] | 2 [1, 3] | 0.34 |

| ECA (posterior auricular artery) (9) | 1 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 3] | 0.98 |

| ECA (suprafacial temporal artery) (10) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.0003 |

| ECA (maxillary artery) (11) | 2 [1, 3] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.0008 |

| ECA (ascending pharyngeal artery) (12) | 1 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 3] | 0.34 |

| Origin of subclavian artery (13) | 2 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | <0.0001 |

| Origin of vertebral artery (V0) (14) | 2 [1, 4] | 2 [1, 4] | 0.001 |

| V1 (preforaminal) (15) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.002 |

| V2 (foraminal) (16) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.88 |

| V3 (atlantic, extradural or extra spinal) (17) | 3 [1, 4] | 3 [1, 4] | 0.11 |

The image quality of an arterial segment was deemed as diagnostic (grade ≥ 3) if the reader was confidently able to visualize the lumen of the carotid’s structure in its entirety.

The stenosis grading of the right and left internal carotid artery was evaluated based on the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET [22]) criteria by using a scoring scale of 1-5:

Grade 1: 0% normal patency.

Grade 2: <50% stenosis.

Grade 3: 50-69% stenosis.

Grade 4: ≥70% stenosis.

Grade 5: 100% occlusion.

When multiple stenotic lesions occurred in a particular arterial segment, the most stenotic lesion was considered the diagnostic grade and was used in the analysis.

Detailed information about the ungated QISS-MRA and the statistical analysis are available in the supplement.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Our study population consisted of 31 patients (median age 65.0 years, age range of [27.7, 91.4] years, weight 79.2 [53.4, 120.0] kg, BMI of 26.3 [17.4, 37.9] kg/m²), including 19 male and 12 female subjects. In 21 cases, the MRI was requested due to the suspicion of an arterio-arterial embolic ischemic stroke or a suspected stroke, in 5 cases for exclusion of a severe carotid stenosis, before a cardiac or aortic surgery, and in 5 cases to exclude a dissection of the cervical arteries after a trauma or after previous dissections.

Image Quality

A total of 62 data sets (31 data sets per QISS-MRA and CE-MRA) were evaluated by three readers.

For QISS-MRA, reader 1 graded the overall image quality in 6.5% (2/31) as “poor”, in 38.7% (12/31) as “good”, and in 54.8% (17/31) of cases as “excellent”; reader 2 graded 16.1% (5/31) as “poor”, 71.0% (22/31) as “good”, and 12.9% (4/31) of cases as excellent; reader 3 graded 3.2% (1/31) as “poor”, 93.5% (29/31) as “good”, and 3.2% (1/31) of cases as excellent.

For CE-MRA, reader 1 graded the overall image quality in 9.7% (3/31) as “poor”, in 48.4% (15/31) as “good”, and in 41.9% (13/31) of cases as “excellent”; reader 2 graded 16.1% (5/31) as “poor”, 38.7% (12/31) as “good”, and 45.2% (14/31) of cases as excellent; reader 3 graded 9.7% (3/31) as “poor”, 80.6% (25/31) as “good”, and 9.7% (3/31) of cases as excellent.

Image quality was graded in 23.7% (22/93) of QISS-MRA cases and in 32.3% (27/93) of CE-MRA cases as “excellent” by all readers. There was no significant difference between both MRA-pulse sequences concerning the image quality (2 [1, 3] vs. 2 [1, 3], p = 0.46, Table 2).

Venous Contamination

For QISS-MRA, reader 1 graded the contaminating venous signal in 77.4% (24/31) as “none“, in 19.4% (6/31) as “minimal”, and in 3.2% (1/31) of cases as moderate; reader 2 graded 93.5% (29/31) as “none“, 3.2% (1/31) as “minimal”, and 3.2% (1/31) of cases as moderate; reader 3 graded 83.9% (26/31) as “none“ and 16.1% (5/31) of cases as “minimal”.

For CE-MRA, reader 1 graded the contaminating venous signal in 3.2% (1/31) as “none“, in 83.4% (26/31) as “minimal”, in 6.5% (2/31) as moderate, and in 6.5% (2/31) of cases as severe; reader 2 graded 12.9% (4/31) as “none“,64.5% (20/31) as “minimal”, 16.1% (5/31) as moderate, and 6.5% (2/31) of cases as severe; reader 3 graded 9.7% (3/31) as “none“, 61.3% (19/31) as “minimal”, 19.4% (6/31) as moderate, and 9.7% (3/31) of cases as severe.

Overall venous contamination was rated as “none” by all readers in 84.9% (79/93) of QISS-MRA cases and in 8.1% (8/93) of CE-MRA cases (0 [0, 2] vs. 1 [0, 3], p < 0.0001, Table 2).

Visualization of Arterial Segments

A total of 3255 arterial segments (35 arterial segments, 18 on the right side and 17 on the left side) for each patient per QISS-MRA and CE-MRA) were evaluated once by all three readers.

For QISS-MRA, reader 1 scored 11.2% (121/1085) of segments with grade 4, 30.9% (335/1085) with grade 3, 29.8% with grade 2 (323/1085), and 28.2% (306/1085) with grade 1. Reader 2 identified 11.2% (121/1085) of segments with grade 4, 30.6% (332/1085) with grade 3, 45.0% with grade 2 (488/1085), and 13.3% (144/1085) with grade 1. Reader 3 graded 11.6% (126/1085) of segments with grade 4, 25.2% (273/1085) with grade 3, 30.5% with grade 2 (331/1085), and 32.7% (355/1085) with grade 1.

The overall median rating grades [min, max] of all readers were: 2 [1, 4]

For CE-MRA, reader 1 identified 22.3% (242/1085) of segments with grade 4, 28.1% (305/1085) with grade 3, 28.6% with grade 2 (310/1085), and 21.0% (228/1085) with grade 1. Reader 2 scored 28.6% (310/1085) of segments with grade 4, 36.3% (394/1085) with grade 3, 29.0% with grade 2 (315/1085), and 6.1% (66/1085) with grade 1. Reader 3 graded 16.8% (182/1085) of segments with grade 4, 24.6% (267/1085) with grade 3, 28.8% with grade 2 (312/1085), and 29.9% (324/1085) with grade 1.

The overall median rating grades [min, max] of readers 1 and 2 were: 3 [1, 4], and reader 3: 2[1, 4].

The visualization quality of arterial segments was considered good to excellent (grade ≥ 3) in 40.2% (1308/3255) for the QISS-MRA and in 52.2% (1700/3255) for the CE-MRA (2 [1,4] vs. 3[1,4], p < 0.0001). A detailed comparison between all arterial segments between both MRA-pulse sequences is shown in Table 2.

There was a strong correlation between QISS-MRA and CE-MRA sequence concerning the detection of carotid stenosis on both sides (r=0.92, p<0.0001) with an excellent inter observer agreement of 0.94 for both sides (Table 3).

Table 3:

Inter observer agreement for the evaluation of QISS-MRA and CE-MRA based on the introduced 3-, 4-, and 5-point scale scoring systems in the section “image analysis”.

| Variable | Inter observer agreement |

|---|---|

| Image quality | 0.54 (0.46, 0.62) |

| Venous contamination | 0.86 (0.80, 0.91) |

| Quality of global arterial visualization | |

| Right side | 0.72 (0.70, 0.74) |

| Left side | 0.71 (0.69, 0.72) |

| ICA stenosis | |

| Right side | 0.94 (0.89, 0.97) |

| Left side | 0.95 (0.90, 0.98) |

Data presented in the form: agreement (95% confidence interval).

The inter observer agreement for the QISS-MRA and CE-MRA concerning the image quality was 0.54, contamination with the venous enhancement was 0.86, visualization of arterial segments on the left and right side was 0.71. Detailed information about the evaluation results are available in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Table 4:

Comparison of ungated QISS-MRA and CE-MRA for assessment of the stenosis grade the extracranial carotid arteries.

| Readers | Right side | Left side | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 66.7 (9.4 – 99.2) |

100.0 (15.8 – 100.0) |

50.0 (1.3 – 98.7) |

100 (39.8 – 100.0) |

83.3 (35.9 – 99.6) |

100.0 (39.8 – 100.0) |

| All readers | 71.4 (29.0 – 96.3) |

92.9 (66.1 – 99.8) |

||||

| Both sides | 85.7 (63.7 – 97.0) |

|||||

| Specificity (%) | 89.3 (71.8 - 97.7) |

86.2 (68.3 - 96.1) |

89.7 (72.7 - 97.8) |

92.6 (75.7 - 99.1) |

88.0 (68.8 - 97.5) |

96.3 (81.0 – 99.9) |

| All readers | 87.7 (78.5 – 93.3) |

92.4 (84.2 – 97.2) |

||||

| Both sides | 90.0 (84.3 – 94.2) |

Data presented in the form: sensitivity/specificity (95% confidence interval).

Clinical examples are provided in Figures 1-5.

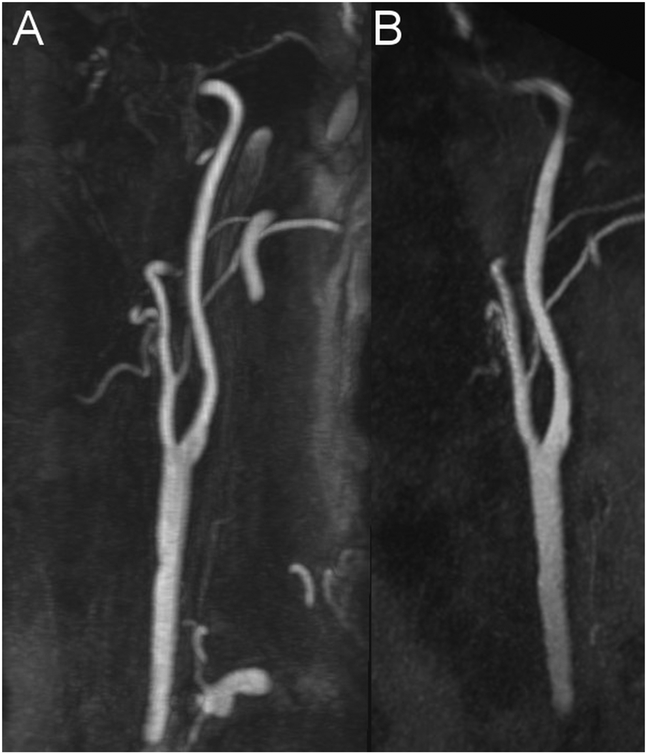

Figure 1: Example for an excellent imaging quality (Grade 3) without any venous contamination (Grade 0).

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with angulation to the left carotid bifurcation of the CE-MRA (A, slice thickness:14.5 mm) and the ungated QISS-MRA (B, slice thickness: 14.1 mm) of a 76-year-old patient with clinical suspected infarction of the right hemisphere and suspected stenosis of the cervical internal carotid artery of the right by ultrasound (same patient as in Figure 5).

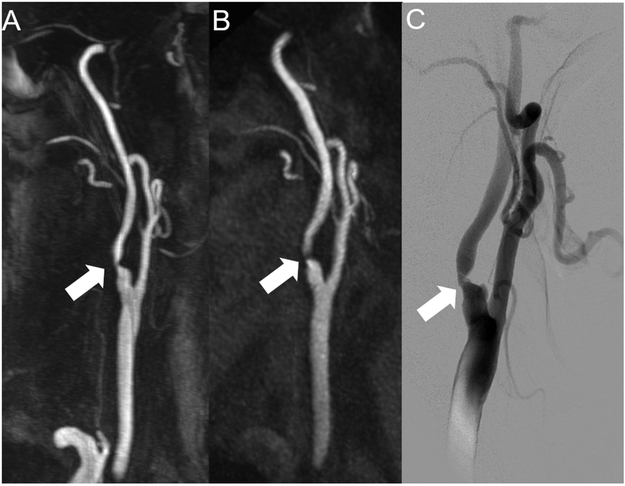

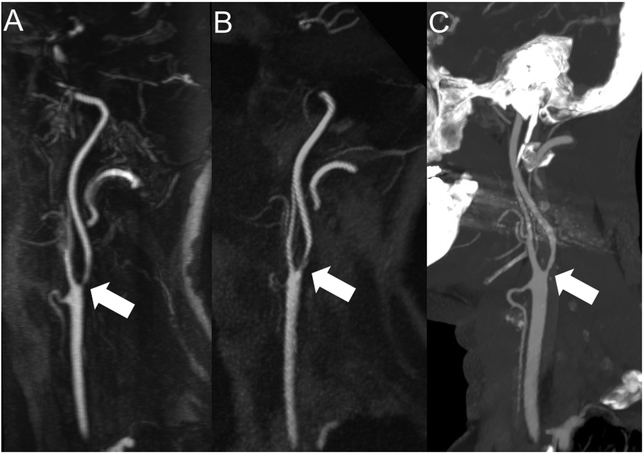

Figure 5: Visualization of internal carotid artery stenosis using CE-MRA and ungated QISS-MRA compared with invasive DSA.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with angulation to the right carotid bifurcation of the CE-MRA (A, slice thickness: 14.0 mm) and the QISS-MRA (B, slice thickness: 13.5 mm) of a 76-year-old patient with clinical suspected infarction of the right hemisphere and suspected stenosis of the cervical internal carotid artery of the right by ultrasound (same patient as in Figure 1). The Corresponding DSA of the right carotid bifurcation (C) before stent angioplasty confirmed the stenosis (white arrows).

Discussion

Due to the known correlation between the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents and the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with end-stage renal disease [9], and also the deposition of gadolinium in some brain regions [10], non CE-MRA techniques have experienced a renaissance in research and development and clinical application [12, 23].

Since the introduction of non-CE QISS-MRA for evaluating the lower extremities in 2010 [17], this technique and its variants have been used and clinically evaluated in a variety of vascular territories. In 2016, Koktzoglou et al [19] presented the feasibility of a cardiac-gated Cartesian QISS sequence variant for non-CE MRA of the extracranial carotid arteries in five healthy volunteers and five patients at 3 T. The results of QISS were compared with those of 2D TOF and CE-MRA, where they found QISS provided better image quality than 2D TOF. Moreover, their initial results suggested that cardiac-gated QISS has potential utility as a non-CE alternative to CE-MRA. A recent retrospective study conducted at 3 T has also demonstrated improved image quality of radial QISS with respect to 2D TOF [20].

In our prospective study, for the first time the diagnostic accuracy of ungated QISS-MRA was compared with CE-MRA in patients with suspected extracranial carotid artery stenosis at 1.5 T. The main findings of this study are: 1) QISS-MRA provides good visualization of the supra-aortic arteries without contrast agent and without cardiac gating. 2) Based on the performed segmental evaluation by three experienced radiologists, ungated QISS-MRA showed high sensitivity and specificity, and a significant correlation with CE-MRA for the detection of carotid artery stenosis. 3) Ungated QISS-MRA is therefore a reliable technique for diagnosing carotid artery stenosis, in particular, in patients with contraindications to gadolinium-based contrast agents.

QISS was originally described as a technique that leverages cardiac gating to optimally synchronize the quiescent intervals and read out to rapid systolic and slow diastolic arterial flow, respectively. However, since the most MRI protocols for imaging in the head and neck are performed without cardiac or peripheral pulse triggering, it is most convenient from a clinical perspective to image without cardiac synchronization.

In this study, an ungated implementation of QISS-MRA pulse sequence leveraging radial k-space sampling was used. The consistent arterial contrast obtained using QISS-MRA in this study was predicated on three factors: first, the continuous flow found in the brain circulation; second, the combination of a rather lengthy inter-echo spacing (~15 ms) and a low flip angle (30°), which minimized saturation of arterial flow; and third, the use of radial k-space sampling to suppress arterial pulsation artifacts.

The duration of the measurement time using ungated QISS-MRA was fixed to 7 minutes and was independent of patient heart rate and ECG quality. While the measurement time of CE-MRA on paper is only 20 seconds, the total time to perform CE-MRA is in fact longer than that needed for ungated QISS-MRA. This is due to the extra time required for the preparation of patients for contrast agent injection, acquisition of a pre-contrast data set as a mask for CE-MRA (~ 20 sec), and also the post-processing of the CE data set (~ 30 sec), which is not needed for the ungated QISS-MRA procedure. The ungated QISS-MRA can be repeated as often as required without occurrence of problems with venous contamination, for instance, for the diagnosis of various arterial abnormalities in head and neck region, and also for serial follow-up imaging. The intracranial arteries can also be acquired in addition to the extracranial arteries, when the slice distance factor is set to a value of −20 to −25% instead of −33% (used in this study), without any extension of measurement time.

As demonstrated in this study, the image quality of ungated QISS-MRA was comparable to that of CE-MRA, and was graded as good or excellent in the majority of cases. In some cases, the informative value of the ungated QISS-MRA was even higher due to less venous signal. There was almost no residual venous signal observed in the ungated QISS-MRA. This result indicates sufficient suppression of venous spins by the tracking venous inversion RF-pulse, despite the use of tilted slices. Compared to axial slices, a possible drawback of tilted slices is the potential for insufficient inflow into vessel segments parallel to the slice direction. A slight reduction of arterial signal intensity was most visible in the aortic arch, near the aortic branches. Based on our data, however, this reduction of image contrast does not affect the diagnosis accuracy for grading of a carotid stenosis. In comparison, some CE-MRA examinations showed severe venous contamination due to mistiming of the image acquisition with respect to the first pass of the contrast bolus.

The acquisition of a CE-MRA data set of extracranial carotid arteries was performed in breath-hold to reduce the image artifacts due to respiratory motion. To avoid the possible image artifacts during the swallowing act, the patients were asked to stop swallowing (e.g. for about 20 seconds). In contrast, ungated QISS-MRA could be performed in free breathing. The ungated QISS-MRA pulse sequence is largely insensitive to respiratory motion and arterial pulsation artifacts due to its use of radial k-space sampling which oversamples the center of k-space and dilutes the impact of respiratory and flow-related signal fluctuations that occur in a minority of radial views. These physiological signal fluctuations were suppressed with the use of radial k-space sampling to a degree that there was no residual stripping apparent with ungated QISS-MRA. Meanwhile, the use of an image-based navigator reduced the impact of intermittent swallowing motion artifact.

All 35 extracranial segments with different shape, length and diameter were analyzed in our study to show up even small, clinically not relevant differences in imaging quality. The CE-MRA provided slightly better visualization of the small vessels. However, these differences did not influence the patient management. Moreover, the clinically relevant findings were reliably detected also by the QISS-MRA.

The results of ungated QISS-MRA correlated strongly with those of CE-MRA concerning the stenosis grading. All three neuroradiologists graded the carotid artery stenosis in nearly 90% of segments (right side: 87.0%, left side: 93.5%) with the same score in ungated QISS-MRA and CE-MRA. In 5 cases, QISS-MRA overestimated the grade of stenosis, and in one case, QISS-MRA underestimated it. In three cases, the overestimation of stenosis grading by QISS-MRA led to a change between grade 1 and 2 (0% to 50% stenosis) and thus without therapeutic relevance.

In two cases, the overestimation of stenosis grading by QISS-MRA led to a change between grade 2 and 3. In one of these cases, the stenosis overestimation would have affected the patient management due to the presence of symptoms for the right carotid stenosis. But in the other case, this overestimation did not affect the therapy management, because the patient did not have the required symptoms on this side.

In the last case, the diagnosis based on the results of QISS-MRA led to an overestimation of stenosis grade in the right carotid from 3 to 4. This change in grading did not affect the therapy management, because a therapy was indicated due to the symptoms on this side. Discrepancies in stenosis evaluation do not only occur between QISS-MRA and CE-MRA, but also between different modalities used for the assessment of ICA stenosis such as CE-CT, DUS and DSA. In cases with discrepant results or borderline stenosis grading, we perform catheter angiography prepared for optional stent implantation. Therefore, relevant stenosis will not be missed and will treated. The diagnostic accuracy of ungated QISS-MRA showed a total sensitivity and specificity of 85.7% and 90.0%, respectively. Furthermore, the evaluation of the ICA stenosis grading revealed an excellent inter observer agreement. This data indicates that ungated QISS-MRA can potentially be used as an alternative to CE-MRA for grading carotid artery stenosis.

The number of patients in our single-center study was relatively small. Potentially a higher number of patients in a multi-center study is necessary to confirm the diagnostic performance of ungated QISS-MRA across wider range of clinical indications.

Conclusions

This study indicates that ungated QISS-MRA is a reliable angiographic technique with significant clinical potential for the visualization of the extracranial carotid arteries and detection of their stenosis at 1.5 T. Ungated QISS-MRA is a feasible alternative for patients with contraindications to gadolinium-based contrast agents, especially in high risk patients with severe renal insufficiency and with an irregular cardiac rhythm. Furthermore, ungated QISS-MRA can avoid the timing-related difficulties of CE-MRA.

Supplementary Material

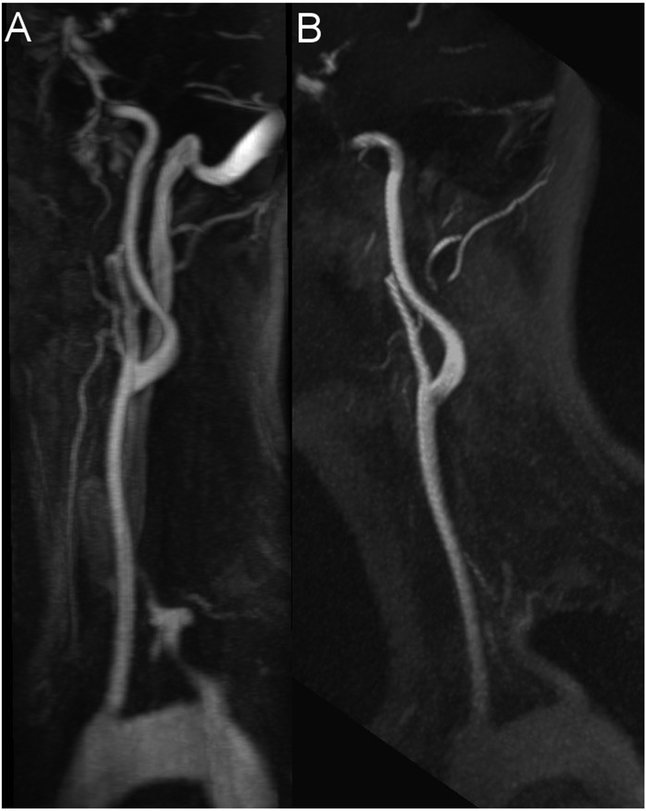

Figure 2: The effect of venous contamination on the image quality.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with angulation to the left carotid bifurcation of the CE-MRA (A, slice thickness: 13.9 mm) and the QISS-MRA (B, slice thickness: 13.5 mm) of a 33-year-old patient with suspected cerebral infarction. In the CE-MRA the bolus is slightly missed, resulting in a severe venous contamination, whereas the QISS-MRA shows no venous signal.

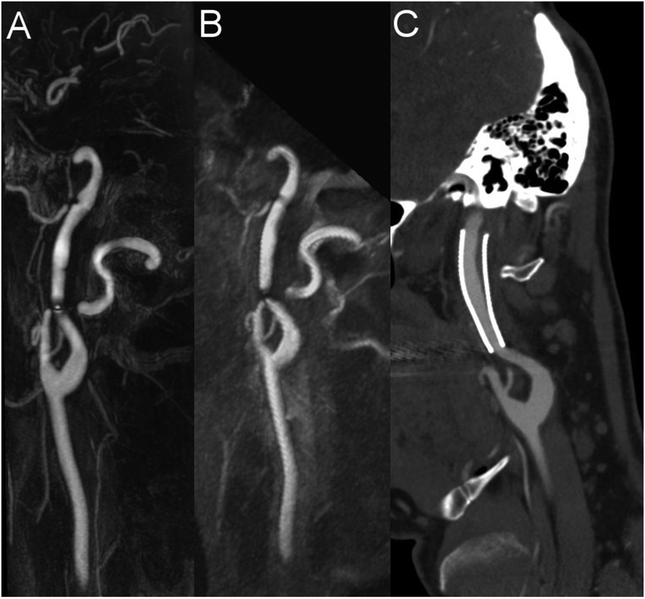

Figure 3: Influence of implanted stent on the image quality.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the CE-MRA (A, slice thickness: 13.0 mm) and of the ungated QISS-MRA (B, slice thickness: 13.0 mm) with angulation to the left internal carotid artery of a 50-year-old patient, who was stented five years ago due to a carotid artery dissection. Corresponding MIP of a CE-CTA (C, slice thickness: 1.4 mm) was obtained two years and digital subtracted angiography (DSA) one year after stenting. In both MRA techniques there are just slight artifacts at the ends of the stent and the lumen is visualized well. This patient was not included in this study.

Figure 4: Visualization of internal carotid artery stenosis using CE-MRA and ungated QISS-MRA compared with CE-CTA.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with angulation to the left carotid bifurcation of the CE-MRA (A, slice thickness: 13.1 mm), the QISS-MRA (B, slice thickness: 13.0 mm), and the CE-CTA (C, slice thickness: 13.0 mm) of a 55-years-old patient with confirmed suspected infarction of the left hemisphere and suspected stenosis of the left internal carotid artery using ultrasound. All three techniques verified the diagnosis of carotid stenosis (white arrows).

Acknowledgments

Grant support

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01EB027475. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CE

contrast enhanced

- CTA

computed tomography angiography

- DSA

digital subtracted angiography

- DUS

Duplex ultrasound

- ECG

electro-cardiogram

- FLASH

fast low angle shot

- FOCI

Frequency offset corrected inversion

- MRA

magnetic resonance angiography

- NASCET

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial

- QISS

quiescent-interval slice-selective

References:

- 1.Flaherty ML, Kissela B, Khoury JC, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Woo D, et al. Carotid Artery Stenosis as a Cause of Stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MSV. Stroke Risk Factors, Genetics, and Prevention. Circ Res. 2017;120:472–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padalino DJ, Deshaies EM. Management of Atherosclerotic Carotid Artery Stenosis In: Rezzani R, editor. Carotid artery disease-from bench to beside and beyond. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobson RW, Mackey WC, Ascher E, Murad MH, Calligaro KD, Comerota AJ, et al. Management of atherosclerotic carotid artery disease: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:480–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishbein MC, Fishbein GA. Arteriosclerosis: Facts and fancy. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2015;24:335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wabnitz AM, Turan TN. Symptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis: Surgery, Stenting, or Medical Therapy? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2017;19:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott AL, Paraskevas KI, Kakkos SK, Golledge J, Eckstein H- H, Diaz-Sandoval LJ, et al. Systematic Review of Guidelines for the Management of Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Carotid Stenosis. United States; 2015. November. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adla T, Adlova R. Multimodality Imaging of Carotid Stenosis. Int J Angiol. 2015;24:179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobner T Gadolinium--a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1104–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanda T, Ishii K, Kawaguchi H, Kitajima K, Takenaka D. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: Relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology. 2014;270:834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa AF, van der Pol CB, Maralani PJ, McInnes MDF, Shewchuk JR, Verma R, et al. Gadolinium Deposition in the Brain: A Systematic Review of Existing Guidelines and Policy Statement Issued by the Canadian Association of Radiologists. Canada; 2018. November. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer H, Runge VM, Morelli JN, Williams KD, Naul LG, Nikolaou K, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of the carotid arteries: Comparison of unenhanced and contrast enhanced techniques. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin P, Collins JD, Koktzoglou I, Molvar C, Markl M, Edelman RR, Carr JC. Evaluating peripheral arterial disease with unenhanced quiescent-interval single-shot MR angiography at 3 T. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:886–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber J, Veith P, Jung B, Ihorst G, Moske-Eick O, Meckel S, et al. MR angiography at 3 Tesla to assess proximal internal carotid artery stenoses: Contrast-enhanced or 3D time-of-flight MR angiography? Clin Neuroradiol. 2015;25:41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yucel EK, Anderson CM, Edelman RR, Grist TM, Baum RA, Manning WJ, et al. AHA scientific statement. Magnetic resonance angiography: Update on applications for extracranial arteries. Circulation. 1999;100:2284–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huston J3, Fain SB, Riederer SJ, Wilman AH, Bernstein MA, Busse RF. Carotid arteries: Maximizing arterial to venous contrast in fluoroscopically triggered contrast-enhanced MR angiography with elliptic centric view ordering. Radiology. 1999;211:265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edelman RR, Sheehan JJ, Dunkle E, Schindler N, Carr J, Koktzoglou I. Quiescent-interval single-shot unenhanced magnetic resonance angiography of peripheral vascular disease: Technical considerations and clinical feasibility. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:951–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edelman RR, Carr M, Koktzoglou I. Advances in non-contrast quiescent-interval slice-selective (QISS) magnetic resonance angiography. Clin Radiol. 2019;74:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koktzoglou I, Murphy IG, Giri S, Edelman RR. Quiescent interval low angle shot magnetic resonance angiography of the extracranial carotid arteries. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:2072–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koktzoglou I, Aherne EA, Walker MT, Meyer JR, Edelman RR. Ungated nonenhanced radial quiescent interval slice-selective (QISS) magnetic resonance angiography of the neck: Evaluation of image quality. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American college of Radiology Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media, Version 10.3: Available at: https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Clinical-Resources/Contrast_Media.pdf; 2018.

- 22.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991;22:711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koktzoglou I, Walker MT, Meyer JR, Murphy IG, Edelman RR. Nonenhanced hybridized arterial spin labeled magnetic resonance angiography of the extracranial carotid arteries using a fast low angle shot readout at 3 Tesla. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.