Abstract

Vessel wall MRI (vwMRI) is a useful tool for the evaluation of intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD). Enhancement can be particular instructive. This study investigated the impact of duration between contrast administration and image acquisition, finding the cohort with the longest duration had the greatest increase in signal intensity change. When using vwMRI to assess ICAD, protocols should be designed to maximize duration between contrast administration and image acquisition to best demonstrate enhancement.

INTRODUCTION

Development of vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging (vwMRI) protocols has improved evaluation of intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) by providing direct visualization of the vessel wall and plaque itself.1–6 In the evaluation of ICAD with vwMRI, an important diagnostic finding is plaque enhancement, a characteristic widely believed to reflect inflammation.7, 8 Inconsistencies in acquisition parameters and image interpretation have limited progress in the development of these promising MRI techniques.6, 7, 9–12

Reproducible quantitative interpretation techniques could help overcome these limitations, particularly with respect to enhancement, but standardization of acquisition parameters is also needed.6 Duration between contrast administration and image acquisition affects the degree of measured enhancement in other pathologies.13, 14 This study examines the impact of time intervals on enhancement measured in ICAD plaques and reference structures.

METHODS

Following an IRB-approved protocol, retrospective analysis was performed of patients undergoing vwMRI for evaluation of ischemic strokes at a major academic medical center. In this protocol, vwMRI studies are performed for patients with confirmed new infarcts suspected to be due to ICAD or not be attributed to another etiology. All patients in this study were evaluated with vwMRI within 14 days of the infarct.

Studies were performed with dedicated head coils on Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) 3T MRI scanners (Prisma, Trio, or Verio). Two blinded neuroradiologists assessed the arterial tree upstream to the new infarct. The reviewers were notified which artery to assess by the vascular neurologist, who adjudicated the stroke parent artery status according to a diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) lesion within the vascular territory of a major artery with ICAD. Reviewers were blinded from clinical data and other MRI findings, most notably DWI. Reviewers noted the lesion that had most likely caused the downstream infarction. The culprit lesions were determined by each reviewer and confirmed between them to be the same lesion for each patient. Each reviewer was blinded from measurements made by the other reviewer. Patients in whom multiple ICAD lesions in the same vascular bed could be considered culprit were excluded to avoid bias. After confirming consensus on the culprit lesion, maximum signal intensity values were recorded on 3D T1-weighted SPACE with DANTE flow suppression pre- and post-contrast.5 Patients were given gadobenate dimeglumine (MultiHance) at a dose of 0.2 mL/kg (0.1 mmol/kg). Additionally, structures known to normally enhance were included, including the low infundibulum, defined as the lowest segment distinguishable from the pituitary gland on axial images; muscle, chosen within the temporalis muscle medial to its mid-belly fibrous band,; cavernous sinus, measuring a segment clearly representing only blood; and choroid plexus.6, 15 Three data points were measured for each site assessed, and the mean was calculated.

Times were tabulated for contrast administration and acquisition of post-contrast images. To exclude outlier data during early development of the vwMRI protocol that could introduce bias, studies with greater than 40 minutes between contrast injection and T1 DANTE acquisition were excluded. Correlation coefficients were calculated between variables as well as p-values to assess significance of associations. For further analysis, the cohort was divided into three different time intervals from contrast injection to T1 DANTE: 0–20 minutes, 20–30 minutes, and 30–40 minutes. Comparison was made of the variance of pre- to post-contrast measurements across these time periods using Levene’s test of the equality of variance. All analyses were performed in Stata 15.1 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

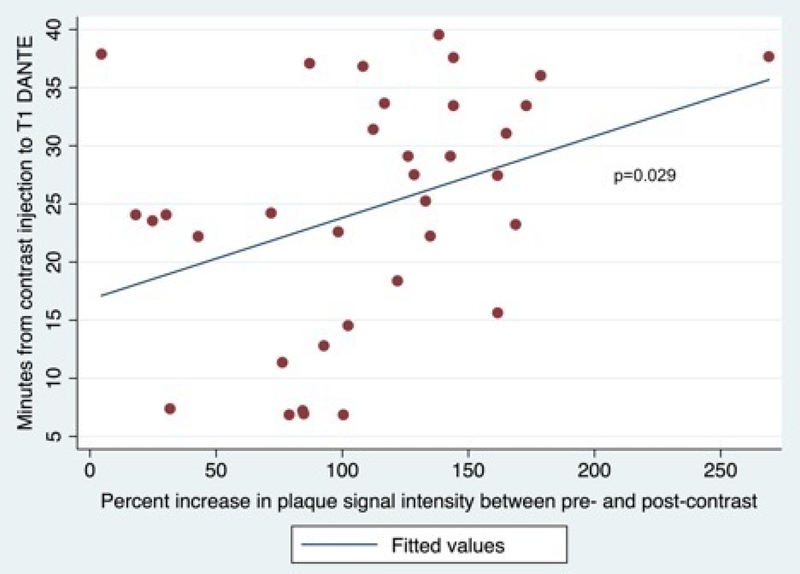

Studies from 54 patients were evaluated. 35 patients met all inclusion criteria (10 studies in the 0–20 minutes group, 13 in 20–30 minutes, and 12 in 30–40 minutes). Representative studies from each time group are provided in Figure 1. The mean±SD time from contrast injection to T1 DANTE was 24.5±10.4 minutes (range 6.9 to 39.5 minutes). In culprit plaques, the percent increase in signal intensity from pre- to post-contrast was 110.2±54.7%, which was significantly associated with time from contrast injection to T1 DANTE (Figure 2, p=0.029). For the reference structures, there was no association between time from contrast injection to T1 DANTE and change in signal intensity between pre- and post-contrast (Table 1). Creating a ratio of percentages in increase T1 signals of plaque over lower infundibulum demonstrates a stronger correlation with timing than plaque alone (r2=0.410, p=0.016). Introducing pituitary signal increase into the model for plaque as a covariate, plaque maintains the association with time (p<0.05). Additionally, there is no direct association between the plaque and infundibulum changes (r2=−0.103, p=0.561).

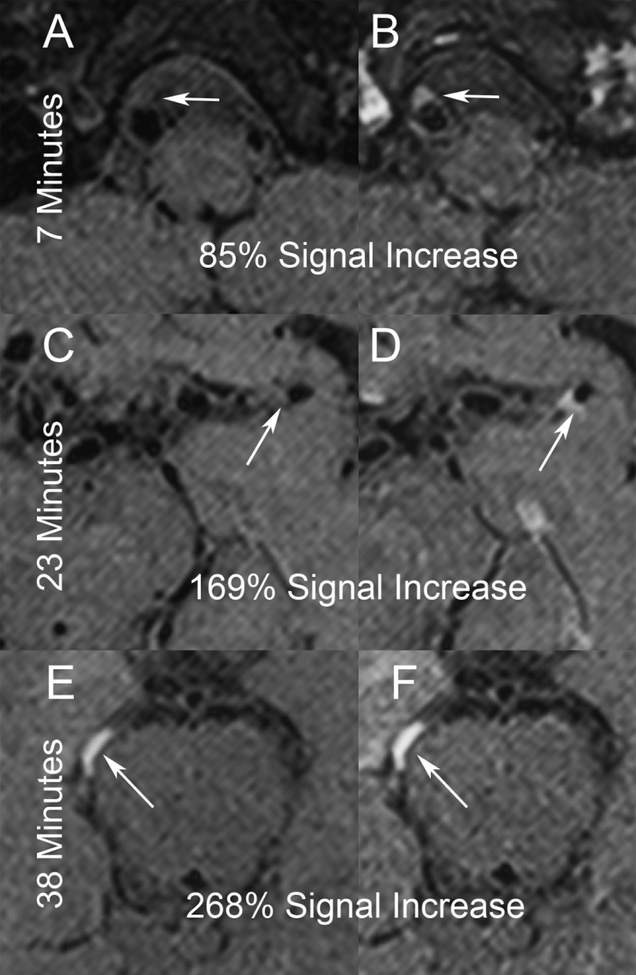

Figure 1:

Representative images of vwMRI studies of symptomatic ICAD lesions (arrows) with studies in each of the three timing cohorts, <20 minutes (A-B), 20–30 minutes (C-D), and 30–40 minutes (E-F). For each study, pre- (A, C, E) and post-contrast (B, D, F) images are shown of lesions in the right V4 segment (A, B), distal left M1 segment (E, F), and right P2 segment (I, J).

Figure 2:

Linear regression between the minutes from contrast injection to T1 DANTE and percent increase in plaque signal intensity between pre- and post-contrast.

Table 1:

Correlation between time from contrast injection to T1 DANTE and measurements of change in signal intensity between pre- and post-contrast.

| Variable | Correlation coefficient | Coefficient of determination (r2) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque (% increase) | 0.370 | 0.137 | 0.029 |

| Low infundibulum (% increase) (n=34) | −0.314 | 0.099 | 0.071 |

| Cavernous sinus (% increase) (n=32) | −0.054 | 0.003 | 0.770 |

| Muscle (% increase) (n=33) | −0.011 | <0.001 | 0.951 |

| Choroid plexus (% increase) (n=33) | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.788 |

| Variable | Correlation coefficient | Coefficient of determination (r2) | p value |

| Plaque (% increase) | 0.370 | 0.137 | 0.029 |

| Low infundibulum (% increase) (n=34) | −0.314 | 0.099 | 0.071 |

| Cavernous sinus (% increase) (n=32) | −0.054 | 0.003 | 0.770 |

| Muscle (% increase) (n=33) | −0.011 | <0.001 | 0.951 |

| Choroid plexus (% increase) (n=33) | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.788 |

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of ICAD can be aided with vwMRI studies.1–3, 6, 8 While these techniques have proven useful, broad clinical utilization is impeded by heterogenous acquisition and interpretation methods. Standardized methodologies can mitigate such issues, particularly when quantitative analyses are employed.6 Enhancement of ICAD plaques is a particularly instructive feature, and this characteristic in particular is prone to variability.6–8 These results confirm our early clinical observation that lesion enhancement was accentuated by increased duration between contrast administration and acquisition of post-contrast DANTE images. The association between time and T1 signal changes in is independent of changes in the pituitary, standardizing plaque signal change to change measured in the pituitary is even more dependent on time from contrast administration. In response to these findings, we have standardized a vwMRI protocol that maximizes this duration within the accepted temporal confines for these studies by acquiring sequences not impacted by contrast (T2, FLAIR) after contrast administration and before post-contrast DANTE imaging.

This study has several limitations that warrant mention. Visualized enhancement may reflect variables other than timing such as differences in plaques, patient age or biological sex, or other factors. Additionally, elapsed time after contrast may be confounded, which cannot be determined without imaging the same person multiple times or doing a dynamic study. Such factors can be assessed in future investigation. Despite these limitations, it appears that future studies using vwMRI might benefit from defined time intervals between contrast administration and post-contrast T1 imaging.

Funding—

This study was funded in part by NIH S10OD018482, NIH R01HL127582, and NIH/NINDS K23NS105924.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval—All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent—Informed consent was obtained as dictated by the institutional review board for participation in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mossa-Basha M, Alexander M, Gaddikeri S, et al. Vessel wall imaging for intracranial vascular disease evaluation. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 1154–1159. 2016/01/16 DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-012127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Havenon A, Mossa-Basha M, Shah L, et al. High-resolution vessel wall MRI for the evaluation of intracranial atherosclerotic disease. Neuroradiology 2017; 59: 1193–1202. 2017/09/25 DOI: 10.1007/s00234-017-1925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandell DM, Mossa-Basha M, Qiao Y, et al. Intracranial Vessel Wall MRI: Principles and Expert Consensus Recommendations of the American Society of Neuroradiology. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology 2017; 38: 218–229. 2016/07/30 DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L, Chai JT, Biasiolli L, et al. Black-blood multicontrast imaging of carotid arteries with DANTE-prepared 2D and 3D MR imaging. Radiology 2014; 273: 560–569. 2014/06/12 DOI: 10.1148/radiol.14131717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li L, Miller KL and Jezzard P. DANTE-prepared pulse trains: a novel approach to motion-sensitized and motion-suppressed quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 2012; 68: 1423–1438. 2012/01/17 DOI: 10.1002/mrm.24142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander MD, de Havenon A, Kim SE, et al. Assessment of quantitative methods for enhancement measurement on vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of intracranial atherosclerosis. Neuroradiology 2019. 2019/01/25 DOI: 10.1007/s00234-019-02167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Baradaran H, Al-Dasuqi K, et al. Gadolinium Enhancement in Intracranial Atherosclerotic Plaque and Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5 2016/08/17 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander MD, Yuan C, Rutman A, et al. High-resolution intracranial vessel wall imaging: imaging beyond the lumen. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 589–597. 2016/01/10 DOI: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JM, Jung KH, Sohn CH, et al. Middle cerebral artery plaque and prediction of the infarction pattern. Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 1470–1475. 2012/08/23 DOI: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiao Y, Zeiler SR, Mirbagheri S, et al. Intracranial plaque enhancement in patients with cerebrovascular events on high-spatial-resolution MR images. Radiology 2014; 271: 534–542. 2014/01/31 DOI: 10.1148/radiol.13122812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skarpathiotakis M, Mandell DM, Swartz RH, et al. Intracranial atherosclerotic plaque enhancement in patients with ischemic stroke. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology 2013; 34: 299–304. 2012/08/04 DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vakil P, Vranic J, Hurley MC, et al. T1 gadolinium enhancement of intracranial atherosclerotic plaques associated with symptomatic ischemic presentations. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology 2013; 34: 2252–2258. 2013/07/06 DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tofts PS and Kermode AG. Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability and leakage space using dynamic MR imaging. 1. Fundamental concepts. Magn Reson Med 1991; 17: 357–367. 1991/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander MD, Hughes N, Cooke DL, et al. Revisiting classic MRI findings of venous malformations: Changes in protocols may lead to potential misdiagnosis. Neuroradiol J 2018; 31: 509–512. 2018/08/10 DOI: 10.1177/1971400918791787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smirniotopoulos JG, Murphy FM, Rushing EJ, et al. Patterns of contrast enhancement in the brain and meninges. Radiographics 2007; 27: 525–551. 2007/03/22 DOI: 10.1148/rg.272065155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]