Abstract

Background

Alcohol use is common among people living with HIV and particularly harmful during pregnancy. However, objective data on alcohol use in pregnant women living with HIV (WLWH) are lacking. In areas with high levels of alcohol use generally, such as South Africa and Uganda, these data are needed to inform interventions.

Methods

Pregnant and non-pregnant, ART-naïve WLWH were recruited from outpatient clinics in South Africa and Uganda. Women provided self-report data on prior three-month alcohol use and potential mental health correlates of alcohol use (depression and stigma). Blood samples were used to measure phosphatidylethanol (PEth), an objective biomarker of recent alcohol intake. We analyzed any alcohol use (i.e., any self-reported use or PEth-positive [≥8 ng/ml]) and under-reporting of alcohol use (i.e., no self-reported use with concurrent PEth-positive).

Results

Among pregnant WLWH (n=163, median age was 26 [IQR: 23–29], median gestational age was 20 weeks [IQR: 16–26]), 40% were using alcohol and 16% under-reported alcohol use. Neither any alcohol use nor under-reporting of alcohol use differed significantly between pregnant and non-pregnant women or by country (p>0.05). Greater depression (but not greater stigma) was significantly associated with any alcohol use (aOR=1.41, 95% CI [1.01, 1.99]; p=0.045).

Conclusions

Alcohol use was prevalent and under-reported among pregnant WLWH in South Africa and Uganda, similar to non-pregnant participants, and associated with depression. General healthcare and antenatal clinic settings present opportunities to provide integrated alcohol-based counseling and depression treatment.

Keywords: Alcohol, HIV, Pregnancy, South Africa, Uganda, Phosphatidylethanol, women living with HIV

Introduction

Hazardous alcohol use is an ongoing problem among individuals living with HIV worldwide. In South Africa and Uganda, where HIV prevalence is among the highest in the world,1 the prevalence of hazardous alcohol use (ranging from heavy drinking to alcohol use disorders) is 7–31% among persons living with HIV.2–5 Alcohol consumption among persons living with HIV is linked to lower adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and, in some studies, compromised immunologic function and higher mortality.7

The harms of alcohol use are even greater among pregnant women living with HIV (WLWH), in part due to the adverse health impact on the developing fetus. Alcohol use during pregnancy is associated with low birth weight, pre-term delivery, and fetal alcohol syndrome, the latter of which affects as many as 21% of children in the Western Cape of South Africa.8–10 Maternal HIV infection itself 11,12 and exposure to some forms of ART13 may further increase risk for some of these poor outcomes.

Studies of perinatal alcohol use in South Africa and Uganda describe self-reported intake ranging from 18–43% during pregnancy.14–17 While many WLWH may reduce or cease alcohol intake after learning of their pregnancy,17,18 women who drink during pregnancy often do so at hazardous levels. Desmond and colleagues17 found that, among pregnant WLWH in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, two-thirds of drinkers (12% of the full sample) reported typically consuming three or more drinks on each drinking occasion. Another analysis found that 9% of pregnant WLWH recruited in Cape Town, South Africa reported hazardous drinking while aware of their pregnancy19; these mothers’ infants were more likely to be small for gestational age than those born to women reporting low levels of alcohol intake during pregnancy.

Perinatal alcohol use in South Africa and Uganda has not been evaluated using objective biomarkers measured during pregnancy, representing a significant gap in the literature for several reasons. For one, non-standard portion sizing20 and varied ethanol content of alcoholic beverages21 across sub-Saharan Africa makes self-report data in aggregate inherently unreliable. Moreover, persons living with HIV may under-report alcohol consumption due to social desirability bias, or fear of being denied ART by medical providers.22 Indeed, studies comparing self-reported to objectively measured alcohol use among non-pregnant persons living with HIV in Uganda reveal under-estimates of both frequency and amount of alcohol use,23,24 and a 50% under-reporting rate among patients initiating ART and testing positive for objective alcohol use.25 Pregnant WLWH may be especially motivated to conceal unhealthy or risky behaviors, such as alcohol consumption. A comparison of self-reported and objectively measured alcohol intake among pregnant WLWH, therefore, represents a critical next step in the literature. Moreover, gathering these objective data is particularly important in areas with known high per capita alcohol consumption, such as South Africa and Uganda.26

Understanding the drivers of alcohol use among pregnant WLWH is also important, and a necessary precursor to developing interventions aimed at reducing perinatal alcohol intake. Pregnancy is often a stressful time for women; one qualitative study among pregnant women surveyed at South African drinking establishments noted participants “drink[ing] [their] problems away,” suggesting the use of alcohol to deal with complex life challenges.27 This stress may be magnified among pregnant WLWH, who experience the added burdens of managing HIV, potential for HIV transmission to the newborn, and concerns about future child-rearing capacity.18,28 Depression is twice as common among pregnant WLWH compared to HIV-seronegative pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa,29,30 and has been linked to increased self-reported alcohol use among pregnant WLWH in South Africa.17 Relatedly, overt discrimination by healthcare workers due to HIV stigma has been reported by pregnant WLWH in Uganda and identified as a driver of maladaptive health behaviors, such as suboptimal engagement in HIV care.31 It remains unknown whether HIV-related stigma is associated with alcohol use among pregnant WLWH in South Africa or Uganda.

The aims of this paper are to: (1) quantify alcohol consumption and under-reporting of alcohol consumption using self-report and objective biomarker data among pregnant WLWH starting ART in South Africa and Uganda; (2) compare any alcohol consumption and under-reporting of alcohol consumption between pregnant and non-pregnant WLWH; and (3) evaluate HIV-related depression and HIV-related stigma as correlates of alcohol consumption among pregnant and non-pregnant WLWH, with pregnancy status as a potential effect modifier.

Methods

Recruitment and Participants

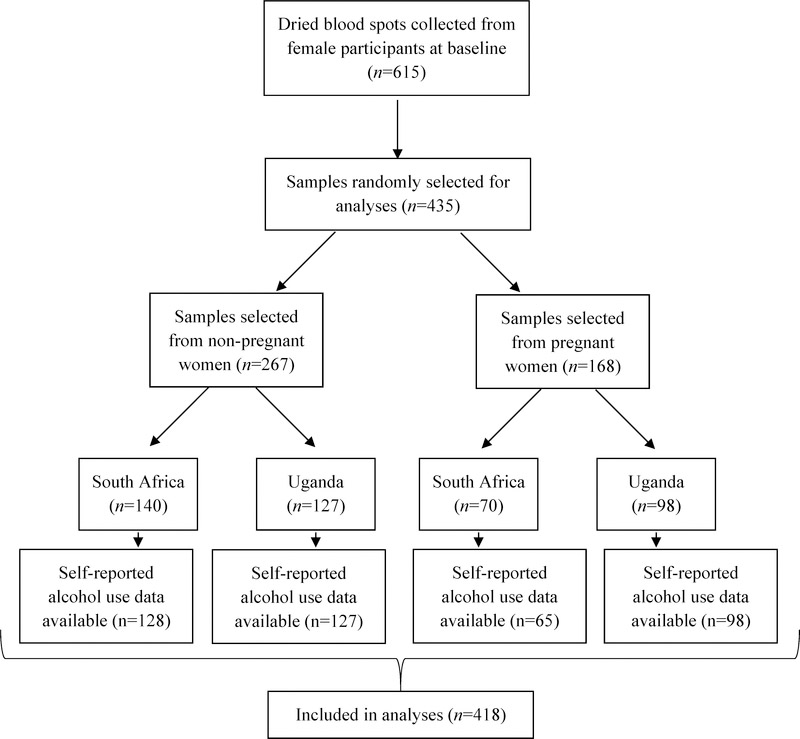

The results presented in this paper represent cross-sectional, secondary analyses from a longitudinal study of adherence to ART among individuals with HIV initiating treatment (Measuring Early Treatment Adherence [META]; ClinicalTrials.gov, 32). Participants were recruited from outpatient clinics offering HIV care in Cape Town, South Africa, and southwestern Uganda between March 2015 and September 2016. Patients were approached by study staff upon presenting for care. To be eligible for the parent study, participants were required to meet the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with HIV; (2) ART-naïve; (3) initiating ART within one month of enrollment; (4) at least 18 years of age; (5) live within 60 km of the clinic; (6) intending to stay in the area for the next year; (7) if pregnant, no more than 34 weeks gestation; (8) able to provide informed consent; and (9) able to communicate in English or local languages (Runyankole or Xhosa). Participants were excluded if they had either: (1) intermediate stage disease at enrollment (CD4: 200–349); or (2) among pregnant women only, late stage disease (CD4 < 200). For the analyses reported here, the sample was restricted to baseline visits only, and to individuals who provided both PEth and self-report data (see Figure 1). All women received care according to national guidelines for ART treatment. The threshold for ART initiation was a CD4 count <500 cells/mm3 during the recruitment period in both sites.

Figure 1.

Testing flow for study of women living with HIV in South Africa and Uganda

Measures

Participants completed a structured interview (measures detailed below) and blood draw at enrollment. Urine samples were collected from all women under age 50 to confirm pregnancy status.

Demographics

Participants were asked to provide basic demographic information including but not limited to age, income, marital status, and educational achievement.

HIV and pregnancy characteristics

Participants were asked to provide time since HIV diagnosis and gestational age. Past three-month CD4 cell count was extracted from participant medical charts, if available, and otherwise assessed by study blood draw at enrollment.

Alcohol consumption

Self-reported and objective alcohol consumption were measured using the three-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C)33 and a blood biomarker (phosphatidylethanol [PEth]), respectively. For the present study, we modified the AUDIT-C to account for only the past three months of alcohol intake (versus past year). The AUDIT-C is scored on a scale of 0–12, with higher scores representing greater self-reported alcohol intake.

To measure objective alcohol use, PEth results were obtained by testing dried blood spots prepared from venous blood draws. PEth levels reflect alcohol intake up to three weeks prior to blood draw.34 All samples were tested at the U.S. Drug Testing Laboratories in Des Plaines, IL using previously published methods.35 PEth testing has demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity (88.0% and 88.5%, respectively) in detecting any alcohol consumption among people living with HIV.36 PEth results have also effectively differentiated between true abstention and light, moderate, and heavy drinking among pregnant women.37

For the primary analyses in this paper, we defined alcohol use based on a combination of AUDIT-C and PEth values; a participant was positive for any alcohol use with an AUDIT-C > 0 (i.e., some self-reported alcohol use) and/or PEth ≥ 8 ng/ml (i.e., the lower limit of quantification). Under-report of alcohol use was defined as indication of no alcohol intake via self-report (AUDIT-C = 0) paired with a quantifiable PEth result (≥ 8 ng/ml). Heavy/hazardous alcohol use was defined as an AUDIT-C ≥ 3 (i.e., self-report cutoff for hazardous drinking, among women specifically) and/or PEth ≥ 50 ng/ml, consistent with cutoffs for heavy drinking used in previous studies.38

Depression

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Depression Scale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (DHSCL).39 The scale used in the present study consisted of 12 items, each representing a distinct depressive symptom. This version of the DHSCL specifically omitted somatic symptoms of depression, as they may overestimate depression among individuals living with HIV.40–42 Participants were asked to rate each symptom on a four-point scale based on the extent to which they experienced it over the previous week (1 = Not at all, 4 = Extremely). The DHSCL has successfully been used to assess depression prevalence among residents of rural Uganda43 and pregnant women across Africa.44 We used a cutoff of ≥ 1.75, which has demonstrated good sensitivity for detecting depression in studies among African populations.45,46

In addition to the DHSCL, pregnant participants completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).47 The EPDS is a frequently utilized measure of perinatal depression severity and probable postnatal depression in African countries, including Uganda.48 Meta-analytic analyses have revealed a pooled sensitivity of 0.94 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.68–0.99) and a pooled specificity of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.59–0.88) at the cutoff score of ≥ 9.44 We used a cutoff score of ≥ 10, consistent with previous studies.49,50

Stigma

Perceived HIV-related stigma was measured using 20 items adapted from the Berger HIV Stigma Scale.51 Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 4 = Strongly agree) and summed across two domains: perceived negative attitudes, and disclosure concerns. Higher scores indicate greater perceived HIV-related stigma.

Statistical Analyses

For descriptive analyses, we calculated proportions for categorical variables, and means, standard deviations (SD), medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. We examined bivariate associations between participant characteristics by pregnancy status and by country (separately) using Chi-square tests (categorical variables) and Mann-Whitney tests (continuous variables). We conducted logistic regression to test bivariate associations between each independent variable of interest (pregnancy status; depression; perceived negative attitudes stigma; disclosure concerns stigma), sociodemographics, and any alcohol use (yes/no; primary outcome variable). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to test the associations of these variables with any alcohol use, while controlling for the following demographic covariates selected a priori: age, marital status, education, and study site. We additionally examined pregnancy as a potential effect modifier of these associations using interaction terms in separate multivariable models, with p < 0.10 on the likelihood ratio test considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Descriptive statistics for demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Female study participants randomly selected for PEth testing (n = 435) were similar to those who were not selected for PEth testing (n = 180; 32 pregnant, 148 not pregnant); no significant differences were observed in age, marital status, education, household assets, months since HIV diagnosis, depression, or the disclosure concerns stigma scale. CD4 count was significantly higher among participants who had PEth results compared to those without (median = 428 [inter-quartile range [IQR]: 193–516], versus 384 [IQR: 144–451]; p < 0.01). Finally, scores on the perceived negative attitudes stigma scale were significantly lower among those with PEth results compared to those without (median = 1 [IQR: 0–2], versus 2 ([IQR: 0–3]; p = 0.02).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics: overall, by group, and by study site (N = 418)*

| Total (N = 418) | Non-pregnant (n = 255) | Pregnant (n = 163) | Uganda (n = 225) | South Africa (n = 193) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Pregnant | 98 (43.6) | 65 (33.7) | |||

| Age (median (IQR)) | 29 (24–35) | 31 (25–39) | 26 (23–29) | 27 (23–32) | 30 (26–37) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than primary school | 95 (22.7) | 62 (24.3) | 33 (20.3) | 77 (34.2) | 18 (9.3) |

| Primary school or more | 323 (77.3) | 193 (75.7) | 130 (79.8) | 148 (65.8) | 175 (90.7) |

| Married/cohabitating | 182 (43.5) | 86 (33.7) | 96 (58.9) | 133 (59.1) | 49 (25.4) |

| Household asset index | |||||

| Low | 176 (44.1) | 102 (42.2) | 74 (47.1) | 126 (58.3) | 50 (27.3) |

| Middle | 146 (36.6) | 88 (36.4) | 58 (36.9) | 49 (22.7) | 97 (53.0) |

| High | 77 (19.3) | 52 (21.5) | 25 (15.9) | 41 (19.0) | 36 (19.7) |

| Months since HIV+ diagnosis (median [IQR]) | 1.2 (0.1–21.7) | 1.4 (0.4–27.6) | 0.3 (0.0–12.7) | 1.2 (0.1–17.9) | 1.1 (0.2–24.3) |

| CD4 (median [IQR]) | 427 (193–517) | 375 (135–448) | 555 (435–692) | 458 (362–596) | 396 (176–474) |

| Number medical visits in past 6 months (median [IQR])** | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) |

| Weeks gestation (median [IQR]) | 20 (16–26) | - | 20 (16–26) | 19 (12–24) | 24 (19–28) |

| History of sexual violence (yes) | 63 (15.1) | 39 (15.4) | 24 (14.7) | 53 (23.7) | 10 (5.2) |

| Hopkins depression scale (mean [SD]) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) |

| Met clinical cutoff (yes; score ≥1.75) | 164 (39.2) | 111 (43.5) | 53 (32.5) | 60 (26.7) | 104 (53.4) |

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score (mean [SD]) | 9.2 (5.2) | -- | 9.2 (5.2) | 8.7 (5.1) | 9.9 (5.2) |

| Met clinical cutoff (yes; score ≥10) | 59 (41.0) | -- | 59 (41.0) | 26 (32.9) | 33 (50.8) |

| Stigma: perceived negative attitudes score (mean [SD]) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.2) |

| Stigma: disclosure concerns score (mean [SD]) | 1.9 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.6) |

Values in bold indicate p-values <0.05 (comparing non-pregnant versus pregnant women, or Uganda versus South Africa).

Number of medical visits includes all visits, scheduled or unscheduled, to a medical facility for any reason in the previous 6 months.

Alcohol Use Prevalence

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for alcohol use, and comparisons of alcohol use across participant groups based on pregnancy status and country. Among the 418 participants, 28.5% self-reported any alcohol use in the prior three months (AUDIT-C > 0). In comparison, 37.8% met criteria for any objective alcohol intake based on biomarker results (PEth ≥ 8 ng/ml). Combining self-report and objective alcohol use data, 42.6% (n = 178) of all participants met criteria for any alcohol use (AUDIT-C > 0 and/or PEth ≥ 8 ng/ml), with 14.1% of women under-reporting alcohol use. Further, 27.0% (n = 113) met criteria for heavy/hazardous alcohol use based on self-report and PEth results.

Table 2.

Participant substance use: overall, by group, and by study site (N = 418)*

| Total (N = 418) | Non-pregnant (n = 255) | Pregnant (n = 163) | Uganda (n = 225) | South Africa (n = 193) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| AUDIT-C (median [IQR]) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) |

| Any self-reported alcohol use (prior 3 months) (yes; AUDIT-C >0) | 119 (28.5) | 80 (31.4) | 39 (23.9) | 61 (27.1) | 58 (30.1) |

| PEth (ng/ml; median [IQR]) | <LLQ (<LLQ-33) | <LLQ (<LLQ-38) | <LLQ (<LLQ-27) | <LLQ (<LLQ-15) | <LLQ (<LLQ-45) |

| Any objectively measured alcohol use (yes; PEth ≥8 ng/ml) | 158 (37.8) | 99 (38.8) | 59 (36.2) | 77 (34.2) | 81 (42.0) |

| Any alcohol use (yes; AUDIT-C >0 and/or PEth ≥8 ng/ml) | 178 (42.6) | 113 (44.3) | 65 (39.9) | 91 (40.4) | 87 (45.1) |

| Under-report of any alcohol use (yes; AUDIT-C=0 and PEth ≥8 ng/ml) | 59 (14.1) | 33 (12.9) | 26 (16.0) | 30 (13.3) | 29 (15.0) |

| Heavy / hazardous alcohol use (yes; AUDIT-C ≥3 and/or PEth ≥50 ng/ml) | 113 (27.0) | 75 (29.4) | 38 (23.3) | 45 (20.0) | 68 (35.2) |

| Current cigarette use | 15 (3.6) | 12 (4.7) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) | 13 (6.7) |

| Current recreational drug use | 4 (1.0) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.6) |

Values in bold indicate p-values <0.05 (comparing non-pregnant versus pregnant women, or Uganda versus South Africa).

Recreational drug use includes marijuana or “other” recreational drugs.

Definitions: AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption; PEth = phosphatidylethanol; LLQ = Lower limit of quantification

Comparing participants based on pregnancy status, 39.9% of pregnant participants were positive for any alcohol use (vs. 44.3% non-pregnant), and 23.3% were positive for heavy/hazardous alcohol use (vs. 29.4% non-pregnant). A greater proportion of pregnant women under-reported current alcohol use (16.0% pregnant vs. 12.9% non-pregnant). None of these differences were statistically significant (p > 0.05). Compared by study site, significantly more participants in South Africa met criteria for heavy/hazardous drinking (35.2%) compared to those in Uganda (20.0%; p < 0.01).

Correlates of Alcohol Use

Tables 3 and 4 present results of multivariable analyses examining pregnancy and depression, respectively, as correlates of any alcohol use. Pregnancy status was not significantly associated with alcohol use in bivariate or multivariable analyses, (adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] = 0.80, 95% CI [0.51, 1.24], p = 0.32 [Table 3]); the association remained nonsignificant in bivariate analyses stratified for age, marital status, and study site (data not shown). Higher depression scores (on the DHSCL) were, however, significantly associated with any alcohol use after adjusting for pregnancy status and demographic covariates (age, marital status, education, and study site; aOR = 1.41, 95% CI [1.01, 1.99], p = 0.045 [Table 4]). Pregnancy status was not a statistically significant effect modifier of this relationship in the full sample (interaction p > 0.10); however, when we stratified these analyses by study site, pregnancy was a significant effect modifier among Ugandan participants only (depression + pregnant, aOR = 2.25, 95% CI [1.02, 4.94], p = 0.04 [Supplementary Table]). Neither stigma type (disclosure concerns stigma, negative attitudes stigma) was significantly associated with alcohol use in multivariable analyses (disclosure concerns, OR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.87, 1.11], p = 0.78; negative attitudes, OR = 0.97, 95% CI [0.82, 1.15], p = 0.72), and pregnancy status was not a statistically significant effect modifier in these relationships (disclosure concerns + not pregnant, aOR = 1.04, 95% CI [0.89, 1.21]; disclosure concerns + pregnant, aOR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.74, 1.10]; negative attitudes + not pregnant, aOR = 1.07, 95% CI [0.87, 1.33]; negative attitudes + pregnant, aOR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.60, 1.08]; all interactions, p > 0.10).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model examining the association between pregnancy status and any alcohol use (N = 418)*

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy status | 0.32 | |

| Not pregnant | 1.00 | |

| Pregnant | 0.80 (0.51, 1.24) | |

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.07 |

| Marital status | 0.39 | |

| Married/cohabitating | 1.00 | |

| Not married | 1.21 (0.78, 1.86) | |

| Education | 0.03 | |

| Less than primary school | 1.00 | |

| Primary school or more | 0.58 (0.35, 0.96) | |

| Study site | 0.17 | |

| Uganda | 1.00 | |

| South Africa | 1.37 (0.87, 2.15) |

Any alcohol use defined as AUDIT-C (prior 3 months) >0 and/or PEth ≥8 ng/ml.

Definitions: AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption; PEth = phosphatidylethanol

Table 4.

Multivariate analyses testing depression as a correlate of any alcohol use and pregnancy as a moderator of this relationship (N = 418)*

| Main Effects Model | Interaction Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR× (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Depression (Hopkins) × | 1.41 (1.01, 1.99) | 0.045 | - | |

| Pregnancy status | 0.38 | |||

| Not pregnant women | 1.00 | - | ||

| Pregnant women | 0.82 (0.52, 1.28) | - | ||

| Pregnancy + depression× | Interaction p=0.25 | |||

| Depression (Δ+1 point), not pregnant | - | 1.22 (0.81, 1.86) | 0.34 | |

| Depression (Δ+1 point), pregnant | - | 1.83 (1.05, 3.19) | 0.03 | |

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.07 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.09 |

| Marital status | 0.43 | 0.46 | ||

| Married/cohabitating | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Not married | 1.19 (0.77, 1.84) | 1.18 (0.76, 1.82) | ||

| Education | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||

| Less than primary school | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Primary school or more | 0.58 (0.35, 0.96) | 0.59 (0.36, 0.97) | ||

| Study site | 0.40 | 0.42 | ||

| Uganda | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| South Africa | 1.22 (0.77, 1.95) | 1.21 (0.76, 1.93) | ||

Any alcohol use defined as AUDIT-C >0 and/or PEth ≥8 ng/ml

Hopkins depression measure was used as continuous variable

Definitions: AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption; PEth = phosphatidylethanol

Discussion

We used a sensitive alcohol biomarker, phosphatidylethanol (PEth), to demonstrate a 43% prevalence of alcohol consumption among women living with HIV (WLWH) initiating ART in South Africa and Uganda. The inclusion of both pregnant and non-pregnant WLWH is unique in this study and allowed for direct comparisons of alcohol use and under-reporting of alcohol use across groups.

The high rates of perinatal alcohol use (40% any use, 23% heavy/hazardous use) among pregnant WLWH in our study are alarming, and exceed most previously reported figures,17,19 including biological measures of ethanol use drawn from newborn meconium.52 Our use of objective and sensitive biomarker data to quantify alcohol intake likely accounts for some of the observed discrepancy, and provided a more accurate assessment of alcohol use compared to self-report. Further, close to one in four pregnant WLWH engaged in heavy/hazardous perinatal drinking, suggesting high risk for adverse infant outcomes in our sample. Heavy episodic drinking during pregnancy is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes (e.g., low birth weight) and risk for long-term neurodevelopmental deficits in children (e.g., attention problems), some of which persist into adulthood.8–10,53 Knowledge of the risk of poor pregnancy outcomes associated with alcohol consumption should be reinforced among all pregnant women, and support provided to avoid any amount of alcohol intake. Indeed, data on the impact of light-to-moderate perinatal drinking on fetal neurodevelopment are inconclusive, and no level of alcohol use during pregnancy is considered reliably safe.54,55 In addition, given emerging data on poorer birth outcomes among women living with HIV and exposed to ART,13,56 our findings highlight the importance of objectively measuring other exposures known to impact birth outcomes.

Notably, alcohol use among pregnant WLWH in our study was not statistically different from non-pregnant women (40% vs. 44%, respectively). This finding raises questions about women’s motivation and/or ability to cease alcohol intake following pregnancy recognition, and the role of cultural factors such as social drinking norms. While we did not collect data on alcohol use preceding conception, prior research has identified pre-pregnancy alcohol consumption as a strong predictor of perinatal consumption among women in South Africa57; this suggests that alcohol use counseling and reduction interventions could best support women of child-bearing age if offered prior to conception in addition to during pregnancy. For example, alcohol-based counseling could be integrated in women’s healthcare, HIV care, and antenatal care settings, and may be performed by healthcare providers during clinic visits or off-site through community-based support groups.58–60

A significant minority of participants under-reported their alcohol intake, with similar rates demonstrated by pregnant and non-pregnant women (16% versus 13%, respectively). Our findings are consistent with a Ugandan study showing a 13% rate of alcohol use under-reporting among non-pregnant WLWH.25 Some under-report of alcohol use is unsurprising given social desirability bias,61 and that individuals initiating ART may be motivated to underplay their drinking behaviors for fear of being denied treatment.22 In fact, the rate of alcohol use under-reporting among pregnant WLWH in our study is surprisingly low. This finding may suggest a pre-established atmosphere of open communication among patients and providers in surveyed clinics or, conversely, patients’ willingness to disclose alcohol use to study research assistants specifically (but not necessarily to medical providers), as observed in prior research.24 The former explanation may be supported by the low levels of HIV-related stigma reported by our participants. As a third and final explanation, many WLWH in our study may have been unaware of the dangers posed by alcohol use during pregnancy, giving them little reason to conceal their true alcohol intake. Future research in this area should evaluate the association, if any, between women’s knowledge of the impact of alcohol consumption on birth outcomes and objective alcohol intake.

A significantly greater proportion of our study participants (pregnant and non-pregnant) recruited from the South African clinic were heavy/hazardous drinkers (35%) compared to women in Uganda (20%). This discrepancy is consistent with population-based data showing more prevalent heavy episodic drinking in South Africa (10.4%) compared to Uganda (3.4%).62 We did not explore the underpinnings of this finding; however, multifaceted cultural differences between countries, including social drinking norms, likely play a part.27,63 Future research should identify key factors associated with alcohol consumption in each country and, based on those data, develop alcohol reduction interventions tailored to local WLWH.

Depression was common and found in approximately 40% of all WLWH in the study. Depression was also significantly associated with alcohol use, such that WLWH with greater depressive symptoms were more likely to consume alcohol. These depression rates are consistent with the extant literature30,64 and suggestive of a pervasive problem among WLWH with potentially serious consequences. Indeed, a systematic review of the literature among persons living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa showed that depressed patients were 55% less likely to demonstrate good adherence to ART compared to their non-depressed peers.6 Interventions that integrate depression treatment with alcohol-based counseling are needed. Further, while pregnancy status was not a statistically significant effect modifier of the relationship between depression and alcohol use in our complete participant sample, we did find a significant association between incremental increases in depression and alcohol use among pregnant women only; it is possible that our relatively small sample size may have limited statistical power to detect a significant result in the full participant pool. Further research should attempt to confirm these findings in a larger sample.

Some methodological limitations to our study should be noted. First, PEth biomarker data reflect only sustained alcohol intake up to three weeks prior to blood draws,65 whereas the self-report measure captures alcohol use from the preceding three months. This mismatch may have impacted the accuracy of our findings by underestimating the rate of under-reporting. Thus, our estimate of under-reporting in this sample of WLWH is likely a conservative one. Second, our findings may have differed had we prospectively measured alcohol intake in the months following ART initiation (i.e., after study enrollment). Research suggests that individuals starting HIV treatment are often driven to reduce alcohol intake in the short-term; however, alcohol reduction efforts may wane over time, possibly in the absence of HIV- or ART-related physical symptoms.38 Indeed, an analysis of data from men and women living with HIV recruited for our parent study showed heavier alcohol use among individuals with higher CD4 levels in Uganda.66 Third, it is possible that PEth results among pregnant WLWH in our study were skewed due to intake of traditional fermented food and beverages with low, but detectable, alcohol content, and that are believed to render health benefits during pregnancy.15 Fourth, our participant sample had significantly higher (i.e., better) CD4 levels and lower reported stigma compared to individuals from the parent study not included in these analyses. It is possible, therefore, that our data would not generalize to all persons living with HIV in the geographic regions sampled. Fifth, it is worth noting that some pregnant participants meeting criteria for perinatal alcohol consumption may have done so only prior to learning of their pregnancy. In other words, women who drank during pregnancy may not have been aware of their pregnancy. Those who have stopped drinking since learning they are pregnant may need counseling to avoid pregnancy during times of heavy alcohol use in the future, but may not need counseling during the current pregnancy. To maximize the efficacy of alcohol use interventions for pregnant WLWH, women should be asked about the timing of their drinking behaviors in relation to pregnancy recognition. Finally, the generalizability of our findings may be limited by the exclusion of individuals with intermediate stage disease, and the short average duration of time since HIV diagnosis (1.2 months) in our sample. The latter may have altered our results in a number of ways, namely inflating depression scores, and potentially decreasing alcohol use.38

Conclusions and Future Directions

This study is the first to provide biomarker-corroborated data on alcohol consumption among pregnant WLWH in sub-Saharan Africa, and to examine differences by pregnancy status across two African countries. We show very high proportions of WLWH using alcohol, with no difference by pregnancy. Depression was also common among both pregnant and non-pregnant participants, and positively associated with alcohol intake.

Offering integrated alcohol-based counseling and mental health services in women’s HIV care and antenatal care settings may improve HIV health status and promote healthier pregnancies. The potential utility of integrating these services may be understood through a syndemics framework, wherein depression and alcohol use among WLWH represent intersecting epidemics with shared social and behavioral drivers.10,67–69 Services could be performed by healthcare providers and held during clinic visits or off-site. Community-based support and task shifting (i.e., recruiting unspecialized or untrained health workers to conserve resources) show promise for large-scale delivery of supportive services. The Mentor Mother Programme, which trains community health workers to deliver home-visiting support and education to pregnant women in African countries, exemplifies this model.70

To minimize alcohol use under-reporting, providers should be encouraged to employ a patient-centered, non-judgmental approach in conversations about alcohol use with WLWH to encourage open dialogue and increase the likelihood of positive change. Future studies should also utilize biomarker data to corroborate alcohol use during pregnancy, and collect data on adverse pregnancy outcomes (e.g., neurodevelopmental problems) to assess the health impact of objective alcohol intake among pregnant WLWH, particularly in settings with high alcohol use.

Finally, while some data support the use of PEth to distinguish levels of drinking (e.g., none versus heavy) among pregnant women,37,71 more studies are needed to confirm the validity of this method in the context of pregnancy (and the physiological changes associated with pregnancy, such as increased blood volume, which could impact test results).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants and the META team:

Principal Investigators: Dr. Jessica Haberer, Dr. Catherine Orrell, Dr. Norma Ware, Dr. Mwebesa Bosco Bwana, Dr. Stephen Asiimwe, Dr. Gideon Amanyire, Hon. Dr. Elioda Tumwesigye, Dr. David Bangsberg

Co-Investigators: Dr. Alex Tsai, Dr. Mark Siedner, Dr. Lynn T. Matthews, Dr. Ingrid Katz, Monique Wyatt

Research Assistants: Nomakhaya April (RN), Alienah Mpahleni, Vivie Situlo, Speech Mzamo, Nomsa Ngwenya, Khosi Tshangela Regina Panda, Teboho Linda, Christine Atwiine, Sheila Moonight, Edna Tindimwebwa, Nicholas Mugisha, Peace Atwogeire, Dr. Vian Namana, Catherine Kyampaire, Gabriel Nuwagaba

Program Managers: Annet Kembabazi, Stephen Mugisha, Victoria Nanfuka, Anna Cross, Nicky Kelly, Daphne Moralie, Kate Bell

Statistician: Nicholas Musinguzi

Data Managers: Dolphina Cogill, Justus Ashaba, Zoleka Xapa, Mathias Orimwesiga, Elly Tuhanamagyezi, Catherine Kyampaire

Lab Managers: Don Bosco Mpanga, Leonia Kyarisima, Simone Kigozi

Drivers: Edgar October, Silver Mugisha, Ibrahim Kiviiri

Conflicts of interest and source of funding: We have no conflicts of interest to report. Funding for the parent study was provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1056051) and National Institutes of Health (K24AA022586, Hahn; K24MH114732, Haberer).

References

- 1.UNAIDS. South Africa Factsheet: HIV and AIDS Estimates.; 2016. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica/.

- 2.Kekwaletswe C, Morojele N, Nkosi S. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Poster presented at the: 6th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; 2011; Rome. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myer L, Smit J, Le Roux L, Parker S, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(2):147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Munyaneza G. Depression, alcohol abuse, and disclosure of HIV serostatus among rural HIV-positive individuals in western Uganda. Neurobehav HIV Med. 2011;2011–3:19–25. doi: 10.2147/NBHIV.S13277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olley BO, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Persistence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa: A 6-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(4):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass JK, Alexandre P, et al. Depression, alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2101–2118. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, Samet JH. Alcohol use and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: Current knowledge, implications, and future directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(10):2056–2072. doi: 10.1111/acer.13204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donald K, Fernandez A, Claborn K, et al. The developmental effects of HIV and alcohol: A comparison of gestational outcomes among babies from South African communities with high prevalence of HIV and alcohol use. AIDS Res Ther. 2017;14:28. doi: 10.1186/s12981-017-0153-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.May PA, Blankenship J, Marais A-S, et al. Approaching the prevalence of the full spectrum of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in a South African population-based study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(5):818–830. doi: 10.1111/acer.12033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell B, Eaton L, Petersen-Williams P. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: Alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and HIV infection in South Africa. Curr HIVAIDS Rep. 2013;10(1):103–110. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0145-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slyker J, Patterson J, Ambler G, et al. Correlates and outcomes of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner A, Tabbah S, Mwapasa V, et al. Severity of maternal HIV-1 disease is associated with adverse birth outcomes in Malawian women: A cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(4):392–399. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a2d13c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zash R, Jacobson DL, Diseko M, et al. Comparative safety of antiretroviral treatment regimens in pregnancy. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10). doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croxford J, Viljoen D. Alcohol consumption by pregnant women in the Western Cape. Afri Med. 1999;89(9):962–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Namagembe I, Jackson L, Zullo M, Frank S, Byamugisha J, Sethi A. Consumption of alcoholic beverages among pregnant urban Ugandan women. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(4):492–500. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0500-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vythilingum B, Roos A, Faure S, Geerts L, Stein D. Risk factors for substance use in pregnant women in South Africa. Afri Med J. 2012;102(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desmond K, Milburn N, Richter L, et al. Alcohol consumption among HIV-positive pregnant women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Prevalence and correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brittain K, Remien RH, Phillips T, et al. Factors associated with alcohol use prior to and during pregnancy among HIV-infected pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sania A, Brittain K, Phillips TK, et al. Effect of alcohol consumption and psychosocial stressors on preterm and small-for-gestational-age births in HIV-infected women in South Africa: A cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn J, Bwana M, Javors M, Martin J, Emenyonu N, Bansberg D. Biomarker testing to estimate under-reported heavy alcohol consumption by persons with HIV initiating ART in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1265–1268. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9768-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis JM, Grosskurth H, Kapiga SH, Weiss HA, Mwashiuya J, Changalucha J. Ethanol concentration of traditional alcoholic beverages in northern Tanzania. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(3):476–477. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papas R, Gakinya B, Baliddawa J, et al. Ethical issues in a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral therapy feasibility study and trial to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in western Kenya. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(3):29–37. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.3.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asiimwe SB, Fatch R, Emenyonu NI, et al. Comparison of traditional and novel self-report measures to an alcohol biomarker for quantifying alcohol consumption among HIV-infected adults in sub-Saharan Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(8):1518–1527. doi: 10.1111/acer.12781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muyindike W, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Fatch R, et al. Phosphatidylethanol confirmed alcohol use among ART-naïve HIV-infected persons who denied consumption in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 2017;29(11):1442–1447. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1290209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajunirwe F, Haberer JE, Boum Y II, et al. Comparison of self-reported alcohol consumption to phosphatidylethanol measurement among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral treatment in southwestern Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health.; 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 27.Watt MH, Eaton LA, Choi KW, et al. “It’s better for me to drink, at least the stress is going away”: Perspectives on alcohol use during pregnancy among South African women attending drinking establishments. Soc Sci Med. 2014:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Motherhood in the context of maternal HIV infection. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26:470–482. doi: 10.1002/nur.10109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernatsky S, Souza R, De Jong K. Mental health in HIV-positive pregnant women: Results from Angola. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):674–676. doi: 10.1080/09540120601012705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaida A, Matthews L, Ashaba S, et al. Depression during pregnancy and the postpartum among HIV-infected women on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67 (Suppl 4):S179–S187. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashaba S, Kaida A, Coleman J, et al. Psychosocial challenges facing women living with HIV during the perinatal period in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haberer JE, Bwana BM, Orrell C, et al. ART adherence and viral suppression are high among most non-pregnant individuals with early-stage, asymptomatic HIV infection: An observational study from Uganda and South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(2):e25232. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley K, Bush K, Epler A, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hahn J, Anton R, Javors M. The formation, elimination, interpretation, and future research needs of phosphatidylethanol for research studies and clinical practice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(11):2292–2295. doi: 10.1111/acer.13213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones J, Jones M, Plate C, Lewis D. The detection of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol in human dried blood spots. Anal Methods. 2011;3(5):1101–1106. doi: 10.1039/C0AY00636J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hahn JA, Dobkin LM, Mayanja B, et al. Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) as a biomarker of alcohol consumption in HIV positives in sub-Saharan Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(5):854–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwak H, Han J, Choi J, et al. Characterization of phosphatidylethanol blood concentrations for screening alcohol consumption in early pregnancy. Clin Toxicol Phila. 2014;52(1):24–31. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.859263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hahn J, Emenyonu N, Fatch R, et al. Declining and rebounding unhealthy alcohol consumption during the first year of HIV care in rural Uganda, using phosphatidylethanol to augment self-report. Addiction. 2016;111(2):272–279. doi: 10.1111/add.13173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez P, Andia I, Emenyonu N, et al. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms and the receipt of antiretroviral therapy in southwest Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4):605–612. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9312-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, Somlai A. Assessing persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection using the Beck Depression Inventory: Disease processes and other potential confounds. J Assess. 1995;64(1):86–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(10):662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolton P, Wilk C, Ndogoni L. Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:442–447. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0763-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai A, Scott J, Hung K, et al. Reliability and validity of instruments for assessing perinatal depression in African settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chorwe-Sungani G, Chipps J. Validity and utility of instruments for screening of depression in women attending antenatal clinics in Blantyre district in Malawi. Afr Fam Pr. 2018;60(4):114–120. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2018.1432136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaaya S, Smith Fawzi M, Mbwambo J, Lee B, Msamanga G, Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(1):9–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01205.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakyo T, Muliira J, Mbalinda S, Kizza I, Muliira R. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among postpartum mothers in a rural district in Uganda. Midwifery. 2011;28(3):374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leung S, Leung C, Lam T, et al. Outcome of a postnatal depression screening programme using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: A randomized controlled trial. J Public Health Oxf. 2011;33(2):292–301. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ongeri L, Wanga V, Otieno P, et al. Demographic, psychosocial and clinical factors associated with postpartum depression in Kenyan women. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):318. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1904-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.English L, Mugyenyi G, Nightingale I, et al. Prevalence of ethanol use among pregnant women in southwestern Uganda. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(10):2209–2215. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2025-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Behnke M, Smith VC. Prenatal substance abuse: Short- and long-term effects on the exposed fetus Behnke M, Smith VC, Levy, et al. , eds. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e1009–e1024. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones K The effects of alcohol on fetal development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011;93(1):3–11. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polańska K, Jurewicz J, Hanke W. Smoking and alcohol drinking during pregnancy as the risk factors for poor child neurodevelopment – A review of epidemiological studies. Int J Occup Med Env Health. 2015;28(3):419–443. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uthman OA, Nachega JB, Anderson J, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(1):e21–e30. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30195-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi KW, Abler LA, Watt MH, et al. Drinking before and after pregnancy recognition among South African women: The moderating role of traumatic experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(97). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milligan K, Niccols A, Sword W, et al. Maternal substance use and integrated treatment programs for women with substance abuse issues and their children: A meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niccols A, Milligan K, Sword W, Thabane L, Henderson J, Smith A. Integrated programs for mothers with substance abuse issues: A systematic review of studies reporting on parenting outcomes. Harm Reduct J. 2012;9(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sweeney PJ, Schwartz RM, Mattis NG, Vohr B. The effect of integrating substance abuse treatment with prenatal care on birth outcome. J Perinatol. 2000;20(4):219. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Del Boca F, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: State of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98 Suppl 2:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health.; 2014:128, 132. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112736/9789240692763_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7910DA48EE00E0EB292B71E37DEC9E9F?sequence=1. Accessed December 18, 2018.

- 63.Kakufo A, Bukuluki P. Qualitative Research in Uganda on Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Concerning Alcohol. Health Communication Partnership (HCP), Afford Project, Young Empowered and Healthy (YEAH); 2008. https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/Alcohol%20Study%20Report%20FINAL%20March%2013th.pdf.

- 64.Yeji F, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Newell M, Hirschhorn L, Hosegood V, Bärnighausen T. Are social support and HIV coping strategies associated with lower depression in adults on antiretroviral treatment? Evidence from rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1482–1489. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.931561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wurst FM, Thon N, Yegles M, Schrück A, Preuss UW, Weinmann W. Ethanol metabolites: Their role in the assessment of alcohol intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(11):2060–2072. doi: 10.1111/acer.12851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magidson J, Fatch R, Orrell C, Amanyire G, Haberer J, Hahn J. Biomarker-measured unhealthy alcohol use in relation to CD4 count among individuals starting ART in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018;Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2364-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, et al. Co-occurring psychosocial problems and HIV risk among women attending drinking venues in a South African township: A syndemic approach. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(2):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9420-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wong M, Myer L, Zerbe A, et al. Depression, alcohol use, and stigma in younger versus older HIV-infected pregnant women initiating antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(1):149–159. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0688-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and Public Health: Reconceptualizing Disease in Bio-Social Context. Med Anthr Q. 2003;17(4):423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, et al. Philani Plus (+): A mentor mother community health worker home visiting program to improve maternal and infants’ outcomes. Prev Sci. 2011;12(4):372–388. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0238-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bracero LA, Maxwell S, Nyanin A, Seybold DJ, White A, Broce M. Improving screening for alcohol consumption during pregnancy with phosphatidylethanol. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;74:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.