Abstract

The seasonal burden of influenza coupled with the pandemic outbreaks of more pathogenic strains underscore a critical need to understand the pathophysiology of influenza injury in the lung. Interleukin 22 (IL-22) is a promising cytokine that is critical in protecting the lung during infection. This cytokine is strongly regulated by the soluble receptor IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) which is constitutively expressed in the lungs where it inhibits IL-22 activity. The IL-22/IL-22BP axis is thought to prevent chronic exposure of epithelial cells to IL-22. However, the importance of this axis is not understood during an infection such as influenza. Here we demonstrate through the use of IL-22BP knockout mice (il-22ra2−/−) that a pro-IL-22 environment reduces pulmonary inflammation during H1N1 (PR8/34 H1N1) infection and protects the lung by promoting tight junction formation. We confirmed these results in NHBE cells in vitro demonstrating improved membrane resistance and induction of the tight junction proteins Cldn4, Tjp1 and Tjp2. Importantly, we show that administering rIL-22 in vivo reduces inflammation and fluid leak into the lung. Taken together our results demonstrate the IL-22/IL-22BP axis is a potential targetable pathway for reducing influenza-induced pneumonia.

Introduction

The seasonal burden of influenza, coupled with the potential catastrophe of pandemic outbreaks, underscores the critical need for understanding the pathophysiology of influenza injury. Vaccination remains a cornerstone in the prevention of infection. However, vaccine efficacy can vary from 50-80 % in a healthy population (1) and is significantly decreased in groups such as the immune compromised (2), very young children and the elderly (1). Thus, while much of the focus is on prevention, there are significant populations that remain at risk of infection. With the recent emergence of more pathogenic strains such as the 2009 and 2014 H1N1, infection can have more devastating consequences. During the 2013-2014 influenza season alone, it was reported that a very high number of young, otherwise healthy individuals required critical care in the ICU, with a high percentage (72%) of these patients developing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and respiratory failure requiring ventilator therapy (3). The current course of treatment for these patients consists of antiviral therapies (Oseltamvir or Zanamivir), which are most effective when given within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. This is often well outside of the window in which individuals seek medical attention. Given the tremendous inflammation and injury that occurs in the lung after influenza infection, effective therapeutic regimens should be focused on reducing viral burden, while decreasing inflammation and at the same time promoting lung/epithelial repair.

The host response to influenza infection has been the subject of intense research to determine whether aspects of this response can be exploited therapeutically. It is important to understand that cytokines play critical roles in both regulating protective and reparative processes as well as causing injury. IL-22 has great potential in reducing pulmonary injury and promoting epithelial repair. Its limited receptor distribution allows IL-22 to have a focused effect on the epithelium. Through the IL-22Ra1/IL-10Rb receptor complex, IL-22 activates STAT3 in lung epithelium there by augmenting barrier function, epithelial repair and the induction of antimicrobial genes (4). Our lab (5) and others (6-8) have shown that IL-22 is important for recovery during influenza infection, as Il-22−/− mice have more severe injury. Moreover, we showed IL-22 receptor distribution in the lung and its importance in reducing lung pathology in both the airways and lung parenchyma after influenza challenge. We also found that Il-22−/− mice infected with H1N1 PR/834 have enhanced structural lung pathology, defective expression of genes that control epithelial repopulation and increased evidence of fibrosis (5).

Generally, IL-22 is not found in the naive lung and is produced by activated T cells following infection. In the case of influenza, IL-22 is produced by both Natural Killer (NK) and Natural Killer T (NKT) cells (7, 9). Once it is produced, it can be post-translationally regulated through interactions with IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP). This soluble receptor is a naturally occurring antagonist that has a 20-1000 fold higher affinity IL-22 than the membrane bound IL-22Ra1 (10-12). IL-22BP binds IL-22 at a site that is directly adjacent to and interferes with the binding of both its membrane bound receptors, IL-22Ra1 and IL-10Rb (11). When bound to IL-22BP, IL-22 is unable to signal through STAT3 (10-12). There are currently three isoforms that have been identified in humans (9). Isoform 1 is retained intracellularly and does not bind IL-22. Human isoform 1 has been found to interact with components of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (13). Human isoform 2 is most closely related to the single murine isoform of IL-22BP and is induced under inflammatory conditions. Human isoform three binds IL-22 with less affinity than human isoform two and is present at high levels during homeostatic conditions (10). In the intestine, IL-22BP is made by dendritic cells (14, 15) and is regulated by the inflammasome (15). Neutralizing IL-22BP in the lung significantly increases survival and decreases neutrophilia in a mouse model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (16). Under naïve conditions in the lung, alveolar epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages have been identified as sources of IL-22BP (17,18), and neutrophils are a source during catastrophic lung injury (18).

In the current study, we demonstrate that shifting the balance of the IL-22/IL-22BP axis in favor of IL-22, promotes recovery during influenza infection by promoting tight junction formation. We demonstrate that NK and CD45− cells and macrophages are main cellular sources of IL-22BP under naïve conditions. However, following influenza infection, these cellular sources decrease production, whereas production by dendritic cells is upregulated. Using Il-22ra2−/− mice we demonstrate that a pro-IL-22 environment significantly reduces pulmonary inflammation and vascular leak into the lung as well as lung pathology. We further reveal that this reduction in lung leak may be due to increases in tight junctions (CLDN4, TJP1, and TJP2) which was confirmed both in vitro and in vivo. More importantly, we demonstrate the therapeutic nature of IL-22 as oropharyngeal administration of IL-22:Fc during infection improved the epithelial barrier and reduced inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Mice

6-8 week old WT (C57Bl/6) were acquired from Jackson labs. Il-22ra1fl/fl mice on a C57BL/6 (B6) background have been previously described (19). To knock out the receptor, these mice were crossed to eIIa-cre (e2a-cre) mice. To determine functional recombination, DNA was extracted and subjected to PCR using primers spanning exon 3. To determine functional deletion of IL-22RA1, lungs were removed, and real time PCR was performed for the Il-22ra1. Il-22ra2−/− mice have been previously described and were backcrossed twelve times on a C57Bl/6 background to generate full knockouts (15). Male mice were used for all experiments and housed in pathogen free conditions in accordance with Tulane University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Oropharyngeal administration of influenza and IL-22:Fc

All treatments were performed via oropharyngeal aspiration while mice were under isofluorane anesthesia. H1N1 (Pr8) was administered at 100PFU in 100ul of sterile PBS. 5μg of IL-22:Fc (Generon, Shanghai, China) was administered in 50μl of sterile PBS.

Cell sorting

Lungs from wild type mice were harvested after 5 days post-infection with H1N1 (Pr8) at 100 PFU in 100 ul of sterile PBS. Lungs were placed in 2 ml of Advanced RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomicyn, Heparin (100 units/mL) and DNAse I (100 units/mL). After mincing the lungs, Liberase TH at 75 ug/mL was added. The tissue was incubated for 25 minutes at 37°C in an elliptical shaker. After incubation, cells passed through a 70 uM filter and incubated in red blood cell lysis buffer prior final resuspension in flow buffer. The following surface markers were used for Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS): CD45 (Tonbo Biosciences, San Diego, Ca), CD11b, CD11c, anti-γδ, CD3, CD4, NK1.1 (all from BioLegend, San Diego, CA), and Siglec F (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were sorted using a FACSAria II instrument (BD Biosciences). Cells from naïve mice were isolated and sorted as described above as controls. For flow sorting, single cells (based on forward and side scatter) were gated as follows: 1) γδ T cells= CD45+, CD3+, γδ+ 2)NK cells=CD45+, NK1.1+ 3) interstitial macrophages=CD45+, F4/80+, CD11b+, Siglec F− 4) alveolar macrophages= CD45+, F4/80+, CD11b+, Siglec F+ 5) dendritic cells= CD45+, F4/80+, CD11c+,CD103+. An aliquot of each sorted population was resorted post-collection to verify purity which was greater than 97% for all populations.

Analysis of lung inflammation and injury

Mouse lungs were lavaged with 1 mL of sterile PBS. Bronchoalveolar lavage (20) was then used for evaluation of inflammatory cells by differential cell counting. To measure lung injury, total protein in the first milliliter of BAL fluid was measured using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). LDH activity was measured using the LDH assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Both assays were performed in a 96-well plate for 30 minutes according to the manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed using the Benchmark Plus plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

To measure lung leak, the Evan’s blue assay was used. Briefly, mice were injected i.v. with a 0.1% sterile solution of Evan’s blue dye 30 minutes prior to sacrifice. The mouse paws and nose turning blue after injection verified dissemination of the dye visually. Evan’s blue was measured in the BAL by measuring absorbance at 620 nm on a spectrophotometer.

Right lung lobe from a separate cohort of mice was used to measure differences in inflammatory cells in the lung by flow cytometry. Briefly, Cd45+ cells differentiated total inflammatory cells. F4/80 was used to differentiate total macrophages. M2 macrophage were differentiated by double positive MHCII and CD206+ cells. M1 macrophages were differentiated by MHCII+CD206− cells. For histopathology, the left lung was fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin before dehydration and paraffin embedding. Paraffin blocks were sectioned at 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. To score the pathology, slides were blinded and full field low magnification (2x) images were taken from 3 sections per mouse. Total inflammation was scored by outlining and measuring the inflamed area using ImageJ and dividing by the total outlined area of the lung section. Numerical scoring was performed as previously described (5). Briefly, airway pathology was scored on a scale of 1-4 as follows: 0=no obvious signs of infection; 1=mild peribronchiolar inflammation; 2= mild mucus cell metaplasia; 3=mucus cell metaplasia with obvious inflammation; 4= severe mucus cell metaplasia, epithelial piling, and severe inflammation. Alveolitis was scored on a 1-4 scale as well. This scale was: 0= no obvious inflammation; 1=minimal focal inflammation; 2= multifocal, mild inflammation; 3 Diffuse, conspicuous coalescing inflammation; 4= Severe parenchymal inflammation with no obvious airspaces.

Cytokine Analysis.

Cytokine analysis was performed on whole lung supernatants from single cell suspensions using the Bio-Rad Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine 23-plex kit per manufacturer’s instructions and luminescence detected using the Bio-Rad BioPlex 200 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Bronchial brushings

Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and cervical dislocation was performed. The rib cage was removed to visualize the lungs. The trachea was exposed, and an incision was made to remove the viscera and muscle around it. Carefully, a small incision was made into the trachea and an abraded PE-10 polyethylene tubing (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was then used to brush inside each branch of the right and left side of the upper airways. One piece of tubing was used to brush each side respectively. Tubing from each bronchial brushing was transferred into 200μl Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) then flash frozen until RNA isolation as described in RT-qPCR section. Presence of upper airway cells were confirmed via RT-qPCR for Scgb1a1.

Cell culture

For Air liquid interface cultures, fully differentiated HBE cell cultures were derived from the Center for Organ Recovery and Education. Cells were prepared using previously described methods (21) approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB. Briefly, bronchi from the 2nd to 6th generations were collected, rinsed, and incubated overnight in EMEM at 4°C. The bronchi were then digested in MEM containing protease XIV and DNase. The epithelial cells were removed and collected by centrifugation and then resuspended in bronchial epithelial growth medium and plated onto collagen-treated tissue culture flasks. When 80%–90% confluence was reached, the passage 0 cells were trypsinized and seeded onto collagen-coated transwell filters. Upon reaching confluence, the cultures were maintained at an air-liquid interface (ALI) and media was changed basolaterally twice weekly. Individual experiments were performed on cells grown from a single donor. There were four total donors for the experiments performed here.

BEAS-2B and primary normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells (Lonza, Allendale NJ) were cultivated in Bronchial Epithelial Cell Basal Medium (BEBM) with BEGM SingleQuots (Lonza, Allendale NJ) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For primary cell lines, all plates were coated with .01mg/ml human fibronectin (Corning, Oneonto NY), 0.03mg/ml bovine collagen type I (Advanced Biomatrix, Carlsbad, CA), and 0.01mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Fisher Bioreagents, Waltham MA) in serum free BEBM. A549 cells were cultivated in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For maintenance of all stock cultures, cells were grown to ~70% confluence then dissociated using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Waltham MA). For primary cell lines, after dissociation cells were transferred to a 50ml conical then spun down at 500g for 5 minutes. Trypsin was then aspirated and fresh BEBM growth media added before plating cells.

H1N1 Infection of cell culture

Cells grown at air liquid interface were infected apically with 2009 H1N1 (MOI 100) in 50ul of media. Media was removed after 4 hours. Transepithelial resistance was measured using a voltmeter (Evom2 Epithelial Voltohmmeter, World Precision Instruments). IL-22:Fc was added to the basal media.

For non-ALI cultures, cells were seeded in 6 well plates at 3.0×105 cells/well and allowed to grow near 70% confluency in their respective growth media (DMEM or BEBM). A549 cells were then serum starved in DMEM with 1% FBS. After 24 hours cells were then infected with Pr8 (MOI 50). Following infection cells were treated with 30ng/ml of IL-22 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) for an additional 24 hours. Cells were then harvested in Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for RNA extraction or fixed in 4% PFA for immunofluorescence analysis after 48 hours.

Immunofluorescence

NHBE cells were seeded at 0.05×105 cells/well on glass bottom 24 well plates and grown to near 70% confluency. Once 70% confluent, were serum starved in DMEM with 1% FBS. Cells were then infected for 24 hours at MOI 50 (Pr8). Followed by treatment with 30ng/ml of IL-22 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) for an additional 48 hours. At the end of the treatment time period cells were then fixed 4% PFA and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100. Cells were washed with PBS and blocked in 5% normal goat serum then stained for ZO1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 10μg/ml for 1 hour each respectively. Goat anti-rabbit 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was then used as a secondary and samples were counterstained with DAPI. EVOS FL Auto Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Carlsbad, CA) was used for analysis.

RT-qPCR

RNA isolation was performed on cells and bronchial brushings using the Trizol method (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, 200μl of chloroform and 200ul of sterile PBS was added to each sample and shaken vigorously for 30 seconds. Samples were incubated for 10 minutes then spun down at 12,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The aqueous phase was then placed into 500μl isopropanol, mixed lightly and incubated for 5 minutes. Samples were then spun down at 12,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was decanted then 1ml of 75% ethanol was added to each sample and spun down at 7600g for 5 minutes. This step was repeated twice then RNA pellet was allowed to air dry before adding 30μl of nuclease free water. RNA was quantified by Nanodrop and quality was determined by a 260/280 verification of ~2. One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California) and verified by RT-PCR amplification of the GAPDH housekeeping gene.

TaqMan Gene Expression primers (Applied Biosystems) were used to determine levels of: GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1), CLDN2 (Hs00252666_s1), CLDN4 (Hs00976831_s1), TJP2 (Hs00910543_m1), Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Cldn4 (Mm00515514_s1), Ocln (Mm00500912_m1), Tjp1 (Mm00493699_m1), IL-22Ra2 (Mn01192969_m1) and Tjp2 (Mm00495620_m1).

Statistical Analysis

All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. Significance was determined using either an unpaired two-tailed t-test when comparing two groups or a one-way ANOVA with Tukey adjustment when comparing multiple groups. All statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6.

Results

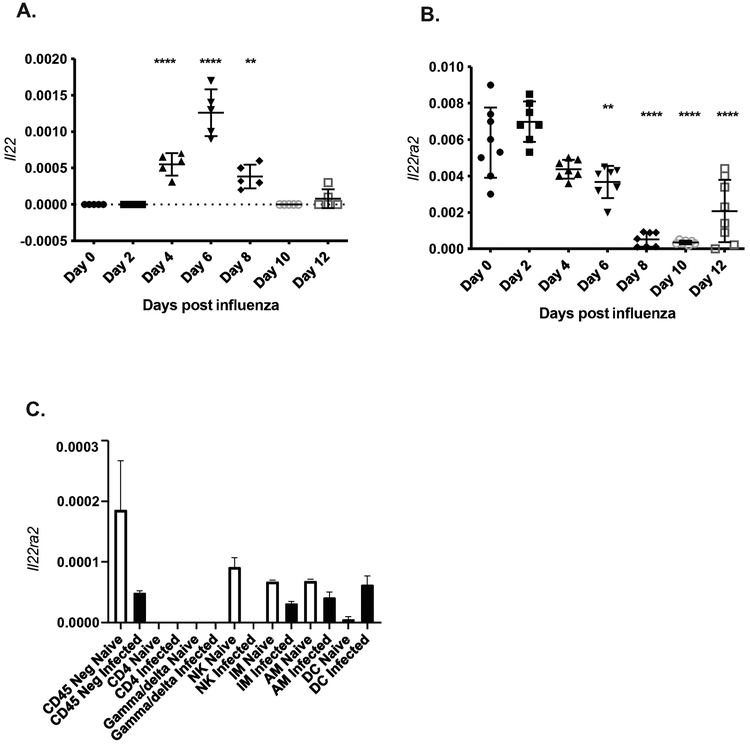

Il-22ra2−/− mice have rapid recovery from influenza infection

IL-22 is beneficial at the epithelial surface during infection(5, 7, 8, 22). Under naïve circumstances, Il22 transcripts are not measured in the lung, while Il22bp transcripts can be found at relatively abundant levels (Figure 1a). During influenza infection, Il22 transcript can be measured starting 4 days after infection and peaking around day 6. This is accompanied by a reduction in Il22bp starting at day 4 and not returning until day 12(Figure 1b).

Figure 1: Influenza induces a pro-IL-22 environment.

Mice were infected with PR8 (A/PR/8/34, 100 pfu) via oropharyngeal administration. Whole lung mRNA was purified. A)mRNA expression of Il22 is induced by day 4 and peaks by day 6. B) Il22bp mRNA is expressed constitutively in the lung and expression is reduced after infection. C) Lung cells from naïve mice and influenza-infected mice were isolated from whole lung and sorted at day 5 post-infection. Il22bp mRNA expression was measured by RT-qPCR. Data is presented as the mean and standard deviation and is representative of 3 experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. **p<0.01 compared to day 0. ****p< 0.0001 compared to day 0. N= at least 5 for all samples and is representative of 2 experiments.

We have had difficulty finding reliable antibodies to measure mouse IL22BP. Therefore, to determine the source of IL-22BP following influenza infection, cells were sorted from whole lung digests by FACS from naïve or day 5 after infection. Under naïve conditions, Il22bp was produced by CD45− cells, NK cells and both interstitial (IM) and alveolar (AM) macrophages. Within 5 days of influenza infection expression of IL22BP was lost in these cells, while expression of Il22bp was increased in dendritic cells (Figure 1C).

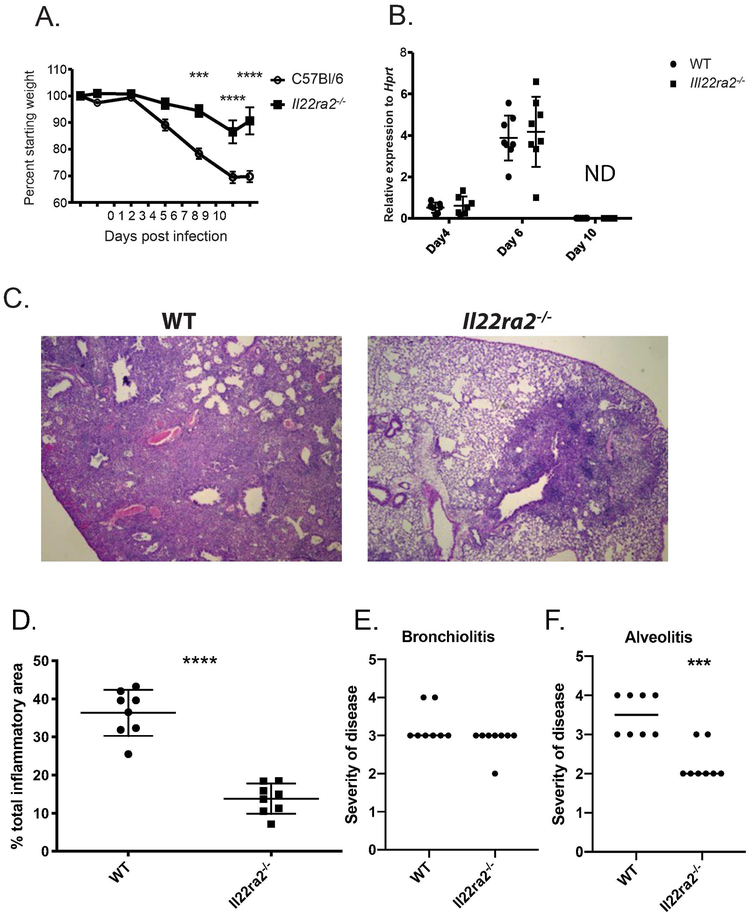

While loss of IL-22 during influenza infection is associated with epithelial disrepair (5, 6, 23), to date there are no publications investigating the impact of IL-22BP in the lung during influenza infection. To determine the importance of IL-22BP during influenza infection, Il22ra2−/− mice were infected with a sub-lethal concentration (100pfu) of influenza (A/PR8) and followed for 10 days. Over this time period, the Il22ra2−/− mice lost significantly less weight and began recovering more rapidly than wild type controls (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Il-22ra2−/− mice recover more quickly after influenza infection.

Mice were infected with PR8 (A/PR/8/34, 100 pfu) via oropharyngeal administration. A) Morbidity as measured by weight loss. Each time point is representative of 8 mice from 2 experiments. B) Lung viral load was measured by quantitative qRT-PCR for the influenza M1 gene. Each point represents an individual mouse. n=8 mice per group from 2 independent experiments. C) Histopathology from day 10 after infection demonstrates extensive inflammation in wild type (53) mice in comparison to very mild, very focal inflammation in the Il-22ra2−/− mice. D) Total affected vs. unaffected areas in infected wildtype and il-22ra2−/− mice. E) Slides were scored blindly for bronchiolitis and alveolitis as described in materials and methods. N= at least 8 for each figure, with each experiment being reproduced at least twice. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A,B) or Students T test. *** p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

While IL-22 can have anti-microbial properties in the lung, it was not known if IL-22 would promote anti-viral response. As such, we measured influenza burden by real time qPCR for the viral M1 gene as we have previously described (5, 24). We found that despite the differences in weight loss, there were no significant differences in viral burden between Il-22ra2−/− and wild type mice at 6 dpi and both groups cleared the virus by day 10 (Figure 2B).

The viral burden findings were not that surprising, as Il22−/− mice do not have any differences in viral clearance with the major phenotype in the Il22−/− mice being decreased epithelial repair (5, 6, 23). Therefore, we next examined histopathology. PR8 infection commonly induces severe airway and parenchymal inflammation at day 10, as seen in 2C. Il22ra2−/− mice had decreased parenchymal inflammation (2C-2F), with mild inflammation around the airways (2C and D). Moreover, we did not see a difference in the number of affected airways (as seen by surrounding inflammation and mucous cell metaplasia) or amount of airway metaplasia (2E) suggesting there was equal distribution of virus. We did however, observe less alveolitis (2F).

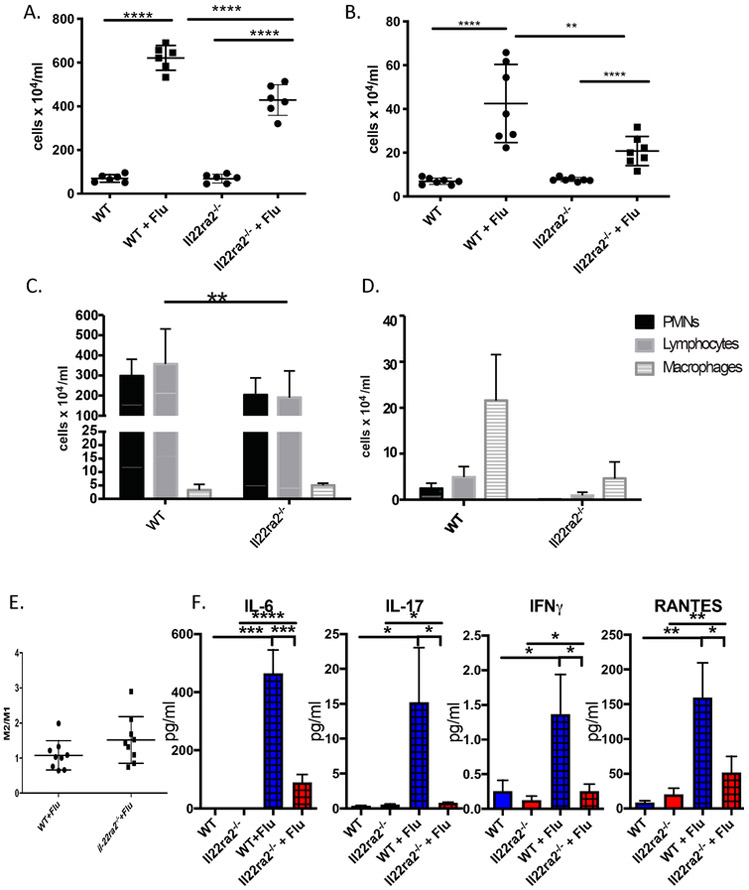

Il22ra2−/− mice have decreased inflammation

The differences in the inflammatory dissemination observed from the histopathology were somewhat surprising as IL-22 has not been found to have a profound impact on inflammation during influenza infection (5, 6, 23). To better understand the changes occurring in the inflammatory compartment, bronchoalveolar lavage (20) fluid was collected and total inflammatory cells were counted. There were no differences in the BAL of mock-infected WT and Il22ra2−/− mice (3A,B) with >98% of the cells being macrophages (data not shown). In conjunction with the histopathology data, Il22ra2−/− mice had decreases in inflammation. At day 5, where the weight loss curves began to diverge, there was a decrease in total inflammation (Figure 3A) as well as a reduction in the total number of T cells (Figure 3C). These data corresponded with decreased cytokine levels of IL-6, IL-17, interferon-γ and RANTES (3F). Inflammatory changes persisted through day 10, where Il22ra2−/− mice had significant decreases in total inflammatory cells (Figure 3B). In comparison to day 5, both groups had decreases in total neutrophils and lymphocytes with an increase in macrophage numbers. This increase was significantly abrogated (p<0.0001) in the Il22ra2−/− mice however (Figure 3D). Differences in types of macrophages were investigated as they were the most robustly altered between the wild-type and il22ra2−/− groups at day 10. Despite significant differences in total numbers of macrophages between the groups, the ratio of M2 (CD45+F4/80+MHCII+CD206+)/M1 (CD45+F4/80+MHCII+CD206−) macrophages remained unchanged (Figure 3E ).

Figure 3. Il-22ra2−/− mice have decreased inflammation 5 and 10 days after influenza infection.

Mice were infected with PR8 (A/PR/8/34, 100 pfu) via oropharyngeal administration. Bronchoalveolar lavage was collected and cells were collected. A) total inflammation from day 5. B) Total inflammation from Day 10 after infection. C) Differential counts from day 5. D) Differential counts from day 10. E) Ratio of M2/M1 macrophages in wildtype vs. il-22ra2−/− mice. F) Cytokine analysis for IL-6, IL-17, Ifnγ and RANTES from lung homogenate. N=8 mice from two independent experiments for A-D. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test or Students T test (E). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 ****p<0.0001

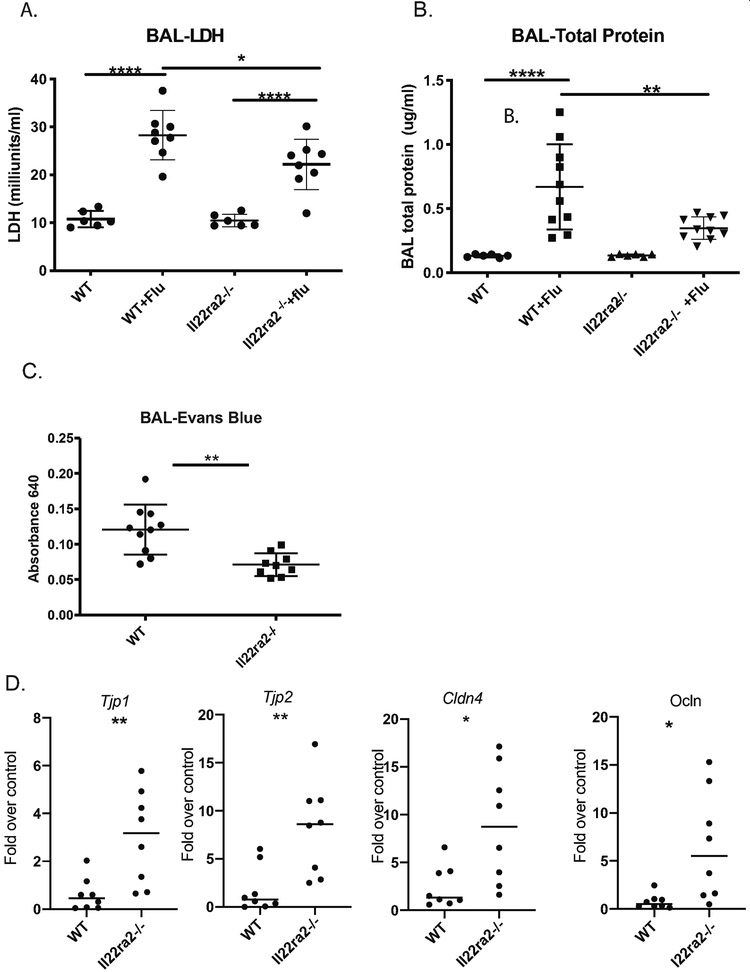

Il22ra2−/− mice have decreased pulmonary injury and pulmonary edema

Previous work from our lab has shown Il-22 knockout mice have severe epithelial injury and reduced epithelial repair during influenza infection (5). We therefore hypothesized that a pro-IL-22 signaling environment would lessen the pulmonary injury seen during influenza infection. To test this Il22ra2−/− mice were sacrificed 5dpi, during optimal IL-22 expression. We found that Il22ra2−/− mice had significantly less injury as measured by LDH (Figure 4A). Further, they had significantly less leak into the lung as measured by total protein in the BAL (Figure 4B). To confirm these data, a subset of influenza-infected mice were injected (i.v) with Evan’s blue dye 30 minutes prior to sacrifice. Similar to the total protein data, Il22ra2−/− mice had significantly less dye in the BAL (Figure 4C), demonstrating less pulmonary edema during influenza infection.

Figure 4. Il-22ra2−/− mice have decreased pulmonary injury and increased tight junctions during influenza infection.

BAL fluid was collected and analyzed from influenza-infected mice 5 days after infection. A) Cell cytotoxicity was detected by measuring lactate dehydrogenase. B) Total protein was measured using the BCA protein assay kit. C) Evan’s blue dye (0.1% in sterile PBS) was administered i.v. 30 minutes prior to collecting BAL. Evan’s blue is measured by absorbance at 640 on a spectrophotometer. D-F) bronchial brushings were performed to collect epithelial cells and RNA was purified and quantitative RT-PCR was performed for D) Tjp1, Tjp2, Cldn4 and Ocln. Data is presented as gene expression over uninfected controls. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test(A,B) or Students T test(C,D) . *p<0.05, **p<0.01 **** p<0.0001.

Loss of barrier function from influenza infection has been attributed to reduced claudin expression in epithelial cells leading to reduced tight junction formation (25). To understand if our observed differences in lung leak were associated with changes in tight junction proteins, we analyzed gene expression of claudins and tight junction proteins. RNA was collected from mouse bronchial brushings (5 DPI), allowing us to focus primarily on epithelial gene expression. In agreement with the pulmonary leak data, we found Il22ra2−/− mice had significantly higher expression of Tjp1,Tjp2, Cldn4 and Ocln during infection (Figure 4D).

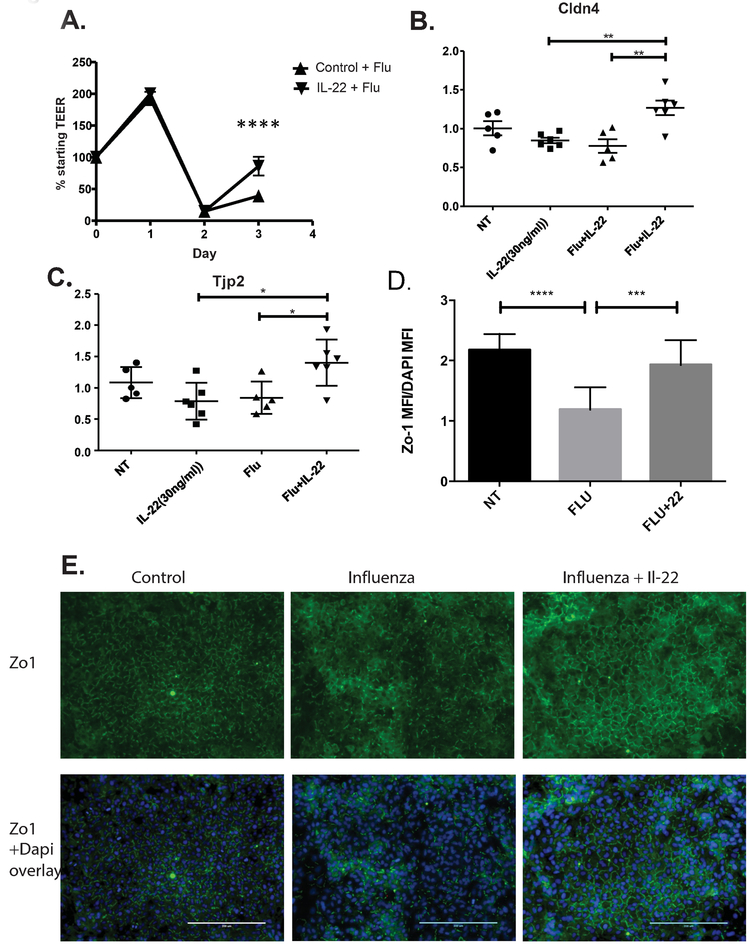

The in vivo findings suggest that a pro-IL-22 signaling environment(decreased IL22BP and increased IL-22) protects the epithelial barrier by promoting tight junction formation. To verify these findings, we next took an in vitro approach. Human lung airway epithelial cells grown at air-liquid interface were infected with influenza (2009 H1N1 MOI 100). Cells were treated with human IL-22:Fc one day after infection and barrier integrity was monitored by measuring resistance across the monolayer (TEER). Interestingly, treatment with IL-22 was not protective, as membrane resistance was lost in both groups. However, IL-22 treatment did promote a faster recovery in membrane resistance by day 3 (Figure 5A). In conjunction with these data, we found IL-22 treatment of NHBE cells grown on collagen induced TJP1 in (Figure 5B) and a significant increase in CLDN4 (Figure 5C). We also found that IL-22 promoted restoration of ZO1 in influenza infected A549 cells (MOI 50) (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5. rIL-22 administration induces tight junctions in vitro during infection.

A) Human airway cells were grown at air liquid interface. Cells were infected with 2009 H1N1 (MOI=100) and treated with human rIL-22:Fc or vehicle (PBS) basolaterally. Transepithelial resistance was measured daily. Each point represents 4 separate experiments from cells from 4 different donors. n=4 wells per experiment. B-C) NHBE cells monolayers grown on collagen and infected (A/PR/8/34, MOI=50) and treated with 30ng/ml rhIL-22 (R&D systems) 1 day after infection. RNA was collected and quantitative RT-PCR was performed for B) CLDN4 and C) TJP2. D) A549 cells were infected and treated with IL-22 (30ng/ml). Shown is representative immunofluorescence staining for ZO1 and DAPI from 2 independent experiments n=4 wells per experiment. E. Comparative quantification of ZO1 mean fluorescent intensity by group. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. N=5 and is representative of 3 experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

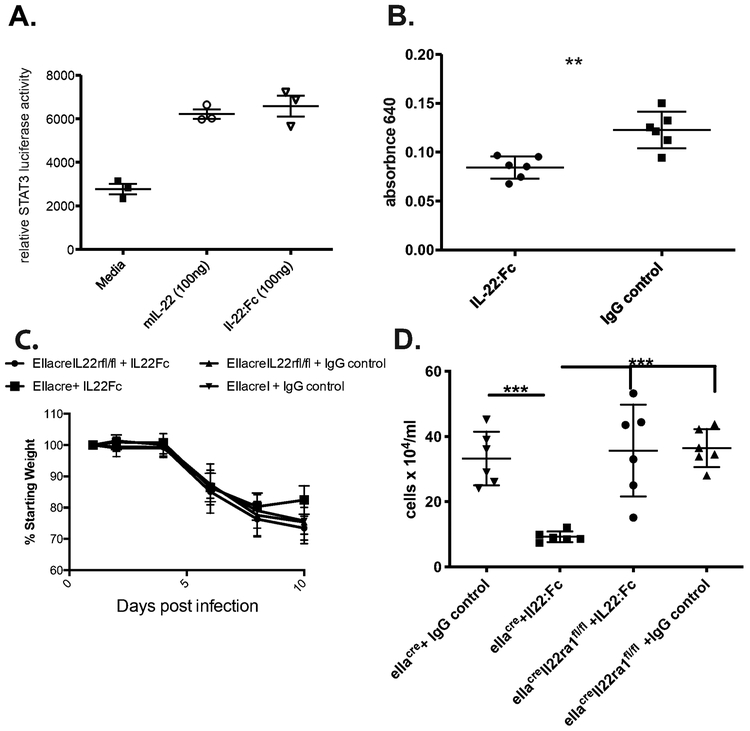

The ability to reduce leak into lung has promise in preventing severe influenza induced pneumonia and the resultant ARDS that occurs. To test the impact of IL-22 administration, we used a human rIL-22:Fc (26), which is capable of signaling on mouse cells (Figure 6A). Mice were treated with IL-22:Fc or Fc control 6 days after infection, when the expression of Il22ra2 significantly wanes (Fig. 1B). Measurement of vascular leak into the lung revealed a significant decrease 24 hours after IL-22:Fc treatment (Figure 6B). To confirm these results were not due to off target effects of the human IL-22 or the Fc, we performed experiments in mice lacking the IL-22 receptor. Il22ra1−/− mice(19, 27) were crossed with EIIa-cre+/+ (EIIacre)mice. This cre is expressed in the early mouse embryo and thus causes recombination and excision of Il-22ra1 globally. EIIacrexIl22ra1fl/fl or EIIacre controls were infected and treated at days 6 and 8 after infection. Although not significant, IL-22R competent mice, but not IL-22R deficient mice, recover weight after IL-22 treatment. Moreover, Results showed that IL-22:Fc treatment significantly reduced the influx of inflammatory cells in the BAL of EIIacre mice but not the mice lacking the IL-22 receptor (EIIacre+/+xIl-22ra1fl/fl) (Figure 6D) or in control treated mice. These data demonstrate IL-22 signaling through the IL-22 receptor, can significantly restore lung tight junctions and reduce inflammation.

Figure 6. rIL-22 administration reduces inflammation and lung leak in vivo during infection.

A) mIL-22 (100ng) and IL-22:Fc were administered to mouse c10 STAT3 luciferase reporter cells respectively. Luciferase activity was measured following treatment with each. C57Bl/6 mice were infected oropharyngeally with 100pfu H1N1 (Pr8) then treated with 5μg IL-22:Fc or IgG 6 days later. B) IL-22:Fc treatment lead to a significant in lung leak. C-D) To confirm this was not due to off target effects of human IL-22 or the Fc, ella-cre+/+ and ella-cre+/+ × il-22ra1fl/fl were infected oropharyngeally with 100pfu H1N1 (Pr8). Six and eight days later, mice were treated oropharyngeally with 5μg IL-22:Fc. IL-22:Fc reduced C) weight loss and D) total inflammation in control (ella-cre+/+) mice. Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. N=6 and is representative of two experiments. **p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Discussion

Influenza remains a severe global health threat. Despite great efforts in advancing vaccination strategies, there is little understanding of how to treat severe influenza induced pneumonia in cases where vaccination is ineffective. To develop treatment options for severe influenza it is vital to understand the immune processes that occur during infection. Here we show the importance of the IL-22/IL-22BP axis in influenza infection. We show that during influenza infection there is a change in the balance of IL-22/IL22BP with IL-22 increasing at the same time Il22ra2 expression is being reduced. We also identified multiple sources for IL22BP in the lung with the most predominant being cd45− cells. Next, using Il-22ra2−/− mice we demonstrate that a pro-IL-22 signaling environment reduces pulmonary inflammation and vascular leak into the lung as well as lung pathology. The reduced leak into the lung is due to increases in tight junction proteins as we found significant increases in claudin 4 as well as zo1 and 2 both in vivo and in vitro. More importantly, we demonstrate the therapeutic nature of IL-22 as oropharyngeal administration of IL-22:Fc during infection improved the epithelial barrier and reduced inflammation.

IL-22 activity appears to be tightly controlled in the lung, as neither transgenic overexpression (28) nor IL-22 administration (29) induce any pathology or inflammation under naïve circumstances. This is likely due in part to limited expression of the IL-22 receptor (5) and constitutive production of IL-22BP (8, 10). Our data demonstrates that Il22bp is present during naïve conditions, regulating the activity of IL-22. It is produced, mainly, by non-inflammatory (CD45−) cells as well as NK cells and macrophages. After infection, Il22bp transcription is significantly decreased in most of its cellular sources. Our data is similar to the findings of Ivanov et al (8), as expression of Il-22 increase in response to influenza infection, there is a reduction of Il22ra2. This is during the same time that the IL-22Ra1 is increased on epithelial cells (5, 30). These changes allow the lung to become a more permissive environment for IL-22 activity. This has been confirmed by microarray studies in which only 431 genes were differentially regulated after IL-22 treatment in naïve mice as opposed to 1231 genes after IL-22 treatment in influenza infected mice (29).

With the exception of rotavirus (31), IL-22 does not alter viral load in other organ systems (32, 33). We confirm these observations, as a pro-IL-22 signaling environment in il22ra2−/− mice had no bearing on influenza burden. Our studies are further supported by findings in the Il22−/− mice which also had no differences in viral burden (5, 6, 23). Interestingly, our findings in the Il22ra2−/− mice demonstrate that pulmonary recovery is independent of the viral load of the animal.

The decreased inflammation in the Il22ra2−/− mice was somewhat surprising, as Il22−/− mice have no inflammatory phenotype during influenza infection (5, 6, 23). The effects of IL-22 are dependent upon the inflammatory milieu and it has been hypothesized that the evolutionary function of IL-22BP is to act as a rheostat controlling the concentration of IL-22 in the milieu and thus its function (10). We found significantly enhanced expression of IL-6, IL-17, IFNγ, and RANTES in wildtype mice when compared to Il22ra2−/− mice. Both IL-6 and IL-17 have negative implications in flu infection. IL-6 is associated with more severe infection (34) and clinically worse outcomes (35). Similarly, IL-17 is associated with exacerbate influenza associated pathology (36, 37) (38). While it is unclear if IL-22 reduces IL-17 or IL-6 directly or through a general reduction of inflammation, it is likely that the reduction of these two cytokines is associated with the improved recovery observed in the Il22ra2−/− mice.

We found that IL-22 promotes tight junction formation during influenza infection, reducing fluid build up in the lung and induces claudin-4 both in vivo and in vitro. This tight junction transmembrane protein is found on epithelium throughout the lung (39). It functions to promote fluid clearance through para cellular chloride efflux (40). It is induced during mechanical trauma (41-43) and induction is and is considered protective in lung injury in both mice and humans (41-44). During influenza, claudin-4 is the primary tight junction protein that is decreased (25). The increased claudin 4, as well as other scaffold proteins (zo-1 and 2) likely account for the reduced fluid build up seen in pro-IL-22 conditions. These data not only have implications for influenza, they are also promising for other injurious or infectious situations that induce acute lung injury.

Admittedly, a caveat to these studies is that mice have only one isoform of IL-22BP as opposed to humans which have 3 (10, 17, 45). The different isoforms have varied distribution throughout the body as well as varying affinity for IL-22 (10, 17, 45). The mouse Il-22ra2 is homologous to the human isoform 2 (IL-22Ra2v2), which has the highest affinity for IL-22 (10, 46). This isoform was initially thought to be the predominant isoform (17, 45). However, it has been recently shown that the third isoform (IL-22Ra2v3) is the most highly expressed isoform in most healthy organs, including the lung (10). Isoform 2 on the other hand, has been found to be induced during inflammatory triggers such as TLR2 activation (10)and retinoic acid (47) in vitro. While it is unclear what happens to the balance of these isoforms in vivo during infection, it is likely our findings presented here are representative of the IL-22/IL-22BP (isoform 2) axis during infection.

Our studies demonstrate that tipping the IL-22/IL-22BP axis in favor of IL-22 is beneficial during influenza infection. Furthermore, targeting this axis has also proven useful in lung bacterial infections (4, 19) and fungal infections (48) as well as bacterial co-infections (8, 22). The question remains though- If IL-22 is so important in resolving infection, why is it so tightly controlled and is it safe to target? The answers to this can be found at other epithelial surfaces. In the skin, overabundance of IL-22 is associated with increased inflammation and psoriasis [for review see (49)] and reduced expression of IL-22BP only exacerbates this process (50, 51). In the intestine, where IL-22 is constitutively expressed to protect the mucosal surface (52), Il-22ra2−/− mice develop greater numbers of tumors in a colitis cancer model (15). Therefore too much IL-22 can have negative consequences. This does not preclude the positive, potentially therapeutic data we present here. Our studies examine very acute responses to IL-22/IL-22BP imbalance and therefore not likely to induce pathology that is seen in diseases of chronic IL-22/IL-22BP imbalance.

The IL-22/IL-22BP axis has likely evolved to protect organs from the potentially inflammatory and proliferative effects of chronic IL-22 exposure. The balance between the two proteins naturally shifts during influenza infection, to allow the lung to be more pro-IL-22. While knocking out Il22bp has a profound benefit on recovery during influenza infection, there are currently not any known therapeutic approaches designed to do this. Administration of IL-22:Fc may prove to be more beneficial. IL-22:Fc is currently in clinical trials for intestinal graft-versus-host disease () and alcoholic hepatitis () and may prove to be a useful therapy during influenza induced pneumonia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The experiments in this manuscript were supported by: NIH R01HL122760 (DAP), NIH R21AI117569(DAP), NIDDKP30-DK-072506 (JMP) and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Grant FRIZZE05X0 (JMP) .

References

- 1.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA, Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 12, 36–44 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zbinden D, Manuel O, Influenza vaccination in immunocompromised patients: efficacy and safety. Immunotherapy 6, 131–139 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catania J, Que LG, Govert JA, Hollingsworth JW, Wolfe CR, High intensive care unit admission rate for 2013-2014 influenza is associated with a low rate of vaccination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189, 485–487 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aujla SJ et al. , IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat Med 14, 275–281 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pociask DA et al. , IL-22 is essential for lung epithelial repair following influenza infection. Am J Pathol 182, 1286–1296 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paget C et al. , Interleukin-22 is produced by invariant natural killer T lymphocytes during influenza A virus infection: potential role in protection against lung epithelial damages. J Biol Chem 287, 8816–8829 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar P, Thakar MS, Ouyang W, Malarkannan S, IL-22 from conventional NK cells is epithelial regenerative and inflammation protective during influenza infection. Mucosal Immunology 6, 69–82 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanov S et al. , Interleukin-22 reduces lung inflammation during influenza A virus infection and protects against secondary bacterial infection. J Virol 87, 6911–6924 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paget C et al. , Interleukin-22 Is Produced by Invariant Natural Killer T Lymphocytes during Influenza A Virus Infection: potential role in protection against lung epithelial damage. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, 8816–8829 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim C, Hong M, Savan R, Human IL-22 binding protein isoforms act as a rheostat for IL-22 signaling. Sci Signal 9, ra95 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu PW et al. , IL-22R, IL-10R2, and IL-22BP binding sites are topologically juxtaposed on adjacent and overlapping surfaces of IL-22. J Mol Biol 382, 1168–1183 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Moura PR et al. , Crystal structure of a soluble decoy receptor IL-22BP bound to interleukin-22. FEBS Lett 583, 1072–1077 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Fernandez P et al. , Long Interleukin-22 Binding Protein Isoform-1 Is an Intracellular Activator of the Unfolded Protein Response. Front Immunol 9, 2934 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin JCJ et al. , Interleukin-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) is constitutively expressed by a subset of conventional dendritic cells and is strongly induced by retinoic acid. Mucosal Immunology 7, 101–113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber S et al. , IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature 491, 259–263 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broquet A et al. , Interleukin-22 level is negatively correlated with neutrophil recruitment in the lungs in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia model. Sci Rep 7, 11010 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu W et al. , A soluble class II cytokine receptor, IL-22RA2, is a naturally occurring IL-22 antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 9511–9516 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittington HA, Armstrong L, Uppington KM, Millar AB, Interleukin-22: a potential immunomodulatory molecule in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31, 220–226 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trevejo-Nunez G, Elsegeiny W, Conboy P, Chen K, Kolls JK, Critical Role of IL-22/IL22-RA1 Signaling in Pneumococcal Pneumonia. J Immunol 197, 1877–1883 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geoghegan S et al. , Mortality due to Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Burden and Risk Factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195, 96–103 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myerburg MM, Harvey PR, Heidrich EM, Pilewski JM, Butterworth MB, Acute regulation of the epithelial sodium channel in airway epithelia by proteases and trafficking. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43, 712–719 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barthelemy A et al. , Interleukin-22 Immunotherapy during Severe Influenza Enhances Lung Tissue Integrity and Reduces Secondary Bacterial Systemic Invasion. Infect Immun 86, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar P, Thakar MS, Ouyang W, Malarkannan S, IL-22 from conventional NK cells is epithelial regenerative and inflammation protective during influenza infection. Mucosal Immunol 6, 69–82 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pociask DA et al. , Epigenetic and Transcriptomic Regulation of Lung Repair during Recovery from Influenza Infection. Am J Pathol 187, 851–863 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Short KR et al. , Influenza virus damages the alveolar barrier by disrupting epithelial cell tight junctions. Eur Respir J 47, 954–966 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang KY et al. , Safety, pharmacokinetics, and biomarkers of F-652, a recombinant human interleukin-22 dimer, in healthy subjects. Cell Mol Immunol, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng M et al. , Therapeutic Role of Interleukin 22 in Experimental Intra-abdominal Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in Mice. Infect Immun 84, 782–789 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang P et al. , Immune modulatory effects of IL-22 on allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation. PLoS One 9, e107454 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barthelemy A et al. , Interleukin-22 immunotherapy during severe influenza enhances lung tissue integrity and reduces secondary bacterial systemic invasion. Infect Immun, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillon A et al. , Neutrophil proteases alter the interleukin-22-receptor-dependent lung antimicrobial defence. Eur Respir J 46, 771–782 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez PP et al. , Interferon-lambda and interleukin 22 act synergistically for the induction of interferon-stimulated genes and control of rotavirus infection. Nat Immunol 16, 698–707 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang X et al. , IL-22 and non-ELR-CXC chemokine expression in chronic hepatitis B virus-infected liver. Immunol Cell Biol 90, 611–619 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster RG, Golden-Mason L, Rutebemberwa A, Rosen HR, Interleukin (IL)-17/IL-22-producing T cells enriched within the liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection. Dig Dis Sci 57, 381–389 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHugh KJ, Mandalapu S, Kolls JK, Ross TM, Alcorn JF, A novel outbred mouse model of 2009 pandemic influenza and bacterial co-infection severity. PLoS One 8, e82865 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oshansky CM et al. , Mucosal immune responses predict clinical outcomes during influenza infection independently of age and viral load. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189, 449–462 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crowe CR et al. , Critical role of IL-17RA in immunopathology of influenza infection. J Immunol 183, 5301–5310 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C et al. , IL-17 response mediates acute lung injury induced by the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. Cell Res 22, 528–538 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gopal R et al. , Mucosal pre-exposure to Th17-inducing adjuvants exacerbates pathology after influenza infection. Am J Pathol 184, 55–63 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaarteenaho R, Merikallio H, Lehtonen S, Harju T, Soini Y, Divergent expression of claudin −1, −3, −4, −5 and −7 in developing human lung. Respir Res 11, 59 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eaton DC, Helms MN, Koval M, Bao HF, Jain L, The contribution of epithelial sodium channels to alveolar function in health and disease. Annu Rev Physiol 71, 403–423 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell LA, Overgaard CE, Ward C, Margulies SS, Koval M, Differential effects of claudin-3 and claudin-4 on alveolar epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301, L40–49 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saatian B et al. , Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cause barrier dysfunction in human airway epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers 1, e24333 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rokkam D, Lafemina MJ, Lee JW, Matthay MA, Frank JA, Claudin-4 levels are associated with intact alveolar fluid clearance in human lungs. Am J Pathol 179, 1081–1087 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y et al. , JNK inhibitor SP600125 protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via upregulation of claudin-4. Exp Ther Med 8, 153–158 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dumoutier L, Lejeune D, Colau D, Renauld JC, Cloning and characterization of IL-22 binding protein, a natural antagonist of IL-10-related T cell-derived inducible factor/IL-22. J Immunol 166, 7090–7095 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones BC, Logsdon NJ, Walter MR, Structure of IL-22 bound to its high-affinity IL-22R1 chain. Structure 16, 1333–1344 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin JC et al. , Interleukin-22 binding protein (IL-22BP) is constitutively expressed by a subset of conventional dendritic cells and is strongly induced by retinoic acid. Mucosal Immunol 7, 101–113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garth JM et al. , IL-33 Signaling Regulates Innate IL-17A and IL-22 Production via Suppression of Prostaglandin E2 during Lung Fungal Infection. J Immunol 199, 2140–2148 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabat R, Ouyang W, Wolk K, Therapeutic opportunities of the IL-22-IL-22R1 system. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13, 21–38 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voglis S et al. , Regulation of IL-22BP in psoriasis. Sci Rep 8, 5085 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin JC et al. , Limited Presence of IL-22 Binding Protein, a Natural IL-22 Inhibitor, Strengthens Psoriatic Skin Inflammation. J Immunol 198, 3671–3678 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pham TA et al. , Epithelial IL-22RA1-mediated fucosylation promotes intestinal colonization resistance to an opportunistic pathogen. Cell Host Microbe 16, 504–516 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammer J, Numa A, Newth CJ, Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatr Pulmonol 23, 176–183 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]