Abstract

Positive emotions help us during times of stress. They serve to replenish resources and provide relief from stressful experiences. Positive emotions may be particularly beneficial during times of stress by dampening negative emotional reactivity and quickening recovery from stressful events. In this study, we used a daily diary design to examine how positive emotions experienced on days with minor stressful events are associated with same day and next day stressor-related negative emotions. We combined data from the National Study of Daily Experiences II (NSDE II) and the Midlife in the United States survey (MIDUS II), resulting in 1,588 participants who answered questions about daily stressors and emotion across 8 consecutive days. On days when people experienced a stressor and had higher than their average level of positive emotion, they experienced less of a same day increase in negative emotion. Additionally, they experienced less subsequent negative emotion the following day and were less likely to experience a stressor the next day. Results held when adjusting for trait measures of positive and negative emotion. These results suggest that daily positive emotions experienced on days of stress help regulate our negative emotion during times of stress.

Keywords: Emotions, Stress, Negative Emotion, Positive Emotion

Positive emotions play an important role in successful adaptation to stress. A large literature has demonstrated the benefits of trait positive emotions and having a general positive disposition on well-being for the stress process (for a review, see Pressman & Cohen, 2005). Several studies suggest that more transient positive emotions are related to shorter and less severe responses to stress (Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2004; Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, 2006) as well as quicker recovery from stressful events (Ong et al., 2006; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). Positive emotions experienced during days with stressful events may help regulate negative emotional responses to stressful events and facilitate quicker emotional recovery from the negative consequences of a stressful experience. The current study assesses whether experiencing higher levels of positive emotion on the day of a reported stressor will buffer stressor-related negative emotion, and whether any potential buffering effects will remain a day later.

Benefits of Positive Emotions

Two major theories have examined and discussed the benefits of positive emotions on attenuating negative emotional responses to stressful events. The dynamic affect model contends that during times of stress, negative emotions tend to crowd out positive emotions (Zautra, Smith, Affleck, and Tennen, 2001). When people experience positive emotions during stressors, these positive emotions will attenuate negative emotional responses. Studies supporting the dynamic affect model demonstrate that positive emotions tend to lessen negative emotions in response to both chronic stressors and everyday life events (Zautra et al., 2001; Zautra, Affleck, & Tennen, 2005; Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2006; Ong & Bergeman, 2004).

In line with the dynamic affect model, the Broad and Build Theory posits that positive emotions serve adaptive functions in times of stress (Fredrickson, 2001, 2013). Positive emotions allow individuals to build up resources (e.g. skills, knowledge, social ties) during times of low stress that are beneficial during times of high stress. Additionally, the Broaden and Build Theory posits that positive emotions also facilitate quicker recovery once negative responses have occurred (Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998). This “undoing effect” hypothesizes that positive emotions undo cardiovascular and autonomic aftereffects of negative emotions by hastening recovery from stressful events. Multiple studies have provided support for the Broaden and Build Theory (for a review, see Fredrickson, 2013). For example, studies conducted in the lab have found that positive emotions are linked to faster cardiovascular recovery from an induced stressor (Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, & Tugade, 2000).

Much of the literature examining the benefits of positive emotions on the stress response has focused on trait qualities, showing that people who generally are more positive and experience more positive emotions have more adaptive stress responses (i.e. Faulk, Gloria, Cance, & Steinhardt, 2012; Moskowitz, Shmueli-Blumberg, Acree, & Folkman, 2012). In addition, emotional responses from stressors are often considered to be a relatively stable trait characteristic (Cohen et al., 2000). Fewer studies focus on how reactions to stressors may fluctuate within individuals despite a study showing that only about 27% of variability in emotional reactivity to a stressor is due to stable individual differences (Sliwinski et al., 2009). This finding implies there is considerable within-person variability in how people respond to stressors.

In laboratory studies, researchers find that induced positive emotions are linked to faster emotional recovery from lab-induced stressors (Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998; Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, & Tugade, 2000). In daily dairy research, one study with older adults has found that positive emotions experienced on days with greater stressor severity led to quicker emotional recovery the following day (Ong et al., 2006). This study provides support for the idea that experiencing positive emotions on days of greater reported stressor severity are linked with attenuated negative emotion within individuals. The proposed study differs from the study by Ong and colleagues in a few important ways. First, the study by Ong and colleagues assessed stress based on ratings of stressor severity and not the occurrence of a stressor. It is possible that the measure of stress was conflated with how people appraised a stressor. This may introduce a report bias conflating both intensity of the experienced stressor and amount of positive emotion. The proposed study focuses not on perceived severity, but on differences in reported negative emotion on days with and without a stressor. Second, the current study conducted additional follow-up tests to see if positive emotion decreases the likelihood of experiencing a next day stressor, a question not examined in the Ong and colleagues’ paper. Finally, the study by Ong and colleagues examined these processes in a relatively small sample of older adults (N = 40, Ages 60 – 85). The current study will expand upon this by looking at a large, national, community-based sample of adults (N = 1,588, Ages 33 – 84).

Current Study

The current study explored the relationship between positive emotions experienced on days when people reported the occurrence of a daily stressful event (e.g. argument with a spouse, work deadline) and both same day and next day negative emotion. We hypothesized that on days when people experienced a stressor and also reported higher than their average level of positive emotion, they would experience lower levels of same day negative emotion than on days they experienced a stressor and reported lower than average positive emotion. We also hypothesized that they would experience less negative emotion the following day. We further hypothesized that these associations would hold after adjusting for trait positive and negative emotion. The daily diary design, where people responded to questions about stressors and emotion across eight days, allowed us to examine these daily processes. Additionally, we adjusted for average number of stressors experienced across the eight-day period, allowing us to rule out the possibility that these associations are driven by overall stressor exposure.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants included a subset of individuals who completed the second Midlife in the United States Survey (MIDUS II), a national, community-based sample of U.S. adults. The MIDUS II consisted of a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaires designed to assess physical and psychosocial well-being. A subset of these participants (N=2022) also completed the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE II), a daily diary study where participants completed repeated telephone interviews across eight consecutive days about their daily experiences (Almeida, McGonagle and King, 2009). 14,912 daily interviews were obtained from the 2,022 participants (92% adherence rate). On the basis of this sample size, there was adequate power (>.90) for detecting small effects (r = .10) and an alpha error probability of .05. Participants were between the ages of 33 and 84 (M=56.2), were fairly well educated (95% reporting at least a high school education), and were predominantly white (92%). The MIDUS and NSDE protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Wisconsin and the Pennsylvania State University, and participants provided informed consent.

Measures Assessed in NSDE II

Daily emotion

Daily emotion was assessed using scales developed for the MIDUS Study (Kessler et al., 2002; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998). For negative emotion, participants were asked each day how much of the time over the past 24 hours they felt nervous, worthless, hopeless, lonely, afraid, jittery, irritable, ashamed, upset, angry, frustrated, restless or fidgety, that everything was an effort, and so sad nothing could cheer you up. Participants rated their answers on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). Scores were then averaged across the 14 items for each day (alphas on each day ranged from .85 to .95) Daily positive emotion was measured through 13 items including in good spirits, cheerful, extremely happy, calm, satisfied, full of life, close to others, like you belong, enthusiastic, attentive, proud, active, and confident. On each of the 8 days, participants were asked how much of the time over the past 24 hours they felt each emotional state on a scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). Scores were then averaged across the 13 items for each day (alphas on each day ranged from .92 to .95).

Daily stressors

Daily stressors were measured by using the semi-structured Daily Inventory of Stressful Events, a validated instrument for assessing daily stressors (Almeida et al., 2002). The DISE asks participants about the occurrence of seven different types of daily stressors within various life domains and captures a variety of interpersonal stressors, work stressors, and network stressors (see Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002 for a detailed description of the DISE). This measure was comprised of 7 stem questions that asked if the following stressors had occurred in the past 24 hours: an argument with someone; almost having an argument but avoiding it; a stressful event at work or school; a stressful event at home; experiencing race, gender, or age discrimination; having something bad happen to a close friend or relative; and having had anything else bad or stressful happen in the past 24 hours. Stressors were then summed for each day. Participants reported between 0 and 5 stressors on each day of the interview (M = 0.51, SD = 0.74 across the 8 days). Across all days, participants reported 0 stressors on 61% of the days, 1 stressors on 29% of the days, and 2 or more stressors on 10% of the days. Because participants reported either experiencing 0 or 1 stressors on 90% of the days, stressors were categorized as either having experienced a stressor on a given day (1) or not (0) to address the skewness of the variable.

Average number of stressors

The total number of stressors reported across the eight-day period were summed and averaged as an index of average stressor levels.

Measures Assessed in MIDUS II

Trait positive emotion

Trait positive emotion was measured in MIDUS II by asking participants how much of the time over the past 30 days they felt 10 items including cheerful, in good spirits, extremely happy, calm and peaceful, satisfied, full of life, enthusiastic, attentive, proud, and active. Responses ranged from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). Scores were averaged across items a for single positive emotion score (α = .84).

Trait negative emotion

Trait negative emotion was measured in MIDUS II by asking participants how much of the time over the past 30 days they felt 11 items including afraid, jittery, irritable, ashamed, upset, nervous, so sad nothing could cheer you up, restless or fidgety, hopeless, everything was an effort, and worthless. Responses ranged from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time), and were averaged together for a single negative emotion score (α = .86).

Statistical Analyses

We used multilevel modeling in SAS Proc Mixed to examine how positive emotions experienced on the same day as a stressor were related to same and next day negative emotion. To examine associations with same day negative emotion, daily stressors were entered as a level 1 variable. Daily positive emotion was centered around a person’s mean level and included as a moderator at level 1. Person-mean centering daily positive emotion allowed us to interpret parameter estimates in terms of a person’s deviation from their own average level. This model also included average number of stressors experienced, age, education, trait positive emotion, and trait negative emotion. These variables were centered at the grand mean and entered at level 2. This generated the following model:

Level 1: Current-day negative emotionij = β0j+ β1j(current-day positive emotionij-1) + β2j(current-day stressorij-1) + β3j(current-day stressorij-1*current-day positive emotionij-1) + rij

Level 2: β0j= γ00+γ01(agej) +γ02(average stressor numberj) + γ03(educationj) + γ04(genderj) + γ06(trait positive emotionj) + + γ07(trait negative emotionj) μ 0j

To examine associations with next day negative emotion, we calculated lagged variables for positive emotion and stressors. This allowed us to assess the association between current day stressors and current day positive emotion on next day negative emotion. Lagged daily positive emotion was centered at the person’s mean and included as a moderator at level 1. Consistent with previous research (Leger et al., 2018), to further ensure that next day negative emotion was not influenced by a next day stressor, we excluded days when individuals experienced a next day stressor. Removing these days from the analyses provides a more stringent test by ensuring that changes in negative emotion are not due to next day stressor. This model also included average number of stressors experienced, age, education, trait positive emotion, and trait negative emotion. These variables were centered at the grand mean and entered at level 2. This generated the following model:

Level 1: Next-day negative emotionij = β0j+ β1j(current-day positive emotionij-1) + β2j(current-day stressorij-1) + β3j(current-day stressorij-1*current-day positive emotionij-1) + rij

Level 2: β0j= γ00+γ01(agej) +γ02(average stressor numberj) + γ03(educationj) + γ04(genderj) + γ06(trait positive emotionj) + γ07(trait negative emotionj) + μ 0j

Results

Participants reported experiencing some negative emotion on 55% of the days they were interviewed (M = 0.19, SD = 0.33). The day after participants experienced a stressor, they reported higher negative emotion (M = 0.24, SD = 0.36) than when they did not experience a prior stressor (M = 0.10, SD = 0.22) (t(13421) = 52.18, p <.001). Participants reported experiencing at least some positive emotion on 99% of the interview days (M = 2.74, SD = 0.79). Positive emotion was lower on days when they experienced stressors (M = 2.53, SD = 0.79) (t(13422) = −261.25, p <.001).

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the main variables of interest. People who experienced fewer stressors were older (r = −0.23, p <.001), male t(14568) = 11.16, p <.001), and had a lower education level (r = 0.20, p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Variables of Interest

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Daily negative emotion | 0.19 | 0.33 | - | ||||||||

| 2. Daily positive emotion | 2.74 | 0.79 | −0.49 | - | |||||||

| 3. Stressor (Ref=no) | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.35 | −0.21 | - | ||||||

| 4. Trait positive emotion | 2.46 | 0.70 | −0.29 | 0.52 | 0.11 | - | |||||

| 5. Trait negative emotion | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.38 | −0.39 | −0.1 | −0.62 | - | ||||

| 6. Age | 56.24 | 12.20 | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.12 | - | |||

| 7. Education | 2.11 | 0.83 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.12 | - | ||

| 8. Gender (ref = female) | 0.56 | 0.50 | −0.05 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.11 | - | |

| 9. Average number of stressors | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.34 | −0.27 | 0.49 | −0.2 | 0.18 | −0.23 | 0.20 | −0.09 | - |

Note: Significant values are indicated in bold and are significant at the p<.001 level

People who experienced greater amounts of daily positive emotion reported fewer stressors (r = −0.28, p <.001) and less negative emotion (r = −0.49, p <.001). Trait positive emotion was also significantly associated with fewer number of stressors (r = −0.19, p <.001), less daily negative emotion (r = −0.29, p <.001), and greater daily positive emotion ((r = 0.52, p <.001). Trait negative emotion, age, gender, and education were significantly associated with daily stressors and where thus included in the model as covariates.

Positive Emotion and Same Day Negative Emotion

People had to report at least one stressor during the eight-day period to be included in the analyses. Of the 2,022 participants, 1,814 experienced at least one stressor. Of these 1,812 participants, 1,588 had complete data for all variables of interest.

Results from the model examining the associations between daily positive emotion and same day negative emotion are shown in table 2. Higher levels of daily negative emotion were related to overall greater trait negative emotion and a greater average number of stressors. As predicted, on days when people experienced a stressor, they reported greater levels of negative emotion the same day (γ = 0.13, p < .001, 95% CI [0.12, 0.13]). Additionally, on days when people had higher than their average daily positive emotion, they reported lower levels of negative emotion (γ = −0.29, p < .001, 95% CI [−0.31, −0.28]).

Table 2.

Multi-level Model of Effects of Current Day Positive Emotions and Stressors on Current Day Negative Emotion

|

Outcome: Current day negative emotion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03, 0.06 |

| Average number of stressors | 0.16*** | 0.01 | 0.14, 0.19 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000,0.00 |

| Gender (ref=female) | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 |

| Education | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02, 0.01 |

| Trait positive emotion | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.00 |

| Trait negative emotion | 0.18*** | 0.01 | 0.15, 0.20 |

| Current day stressor | 0.13*** | 0.00 | 0.12, 0.13 |

| Current day positive emotion | −0.29*** | 0.01 | −0.31, −0.28 |

| Current day stressor x Current day positive emotion | −0.15*** | 0.01 | −0.17, −0.13 |

p<.05

p <.01

p <.001

In line with our main hypothesis, an interaction occurred between stressor and positive emotion, indicating that on days when people experienced a stressor and greater than average daily positive emotion, they experienced less same day negative emotion compared to days when they experienced a stressor and lower than average daily positive emotion (γ = −0.15, p <.001, 95% CI [−0.17, −0.13]). This finding held after adjusting for trait levels of negative and positive emotion.

Positive Emotion and Next Day Negative Emotion

Next, we examined the associations between a daily stressor and daily positive emotion on next day negative emotion. As a strict test to ensure that next day negative emotion was not influenced by a next day stressor, we excluded days when individuals experienced a next day stressor. After these days were removed from the analyses, there were 1518 participants and 6,128 current stressor-free days.

Results from the model examining the associations between daily positive emotion and next day negative emotion are shown in table 3. Similar to the findings on same day negative emotion, on days when people experienced a stressor, they reported greater levels of negative emotion the next day (γ = 0.01, p = .01, 95% CI [0.00, 0.02]).

Table 3.

Multi-level Model of Effects of Current Day Positive Emotions and Stressors on Next Day Negative Emotion

|

Outcome: Next day negative emotion |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | 95% CI |

| Intercept | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.12, 0.04 |

| Average number of stressors | 0.09*** | 0.01 | 0.07, 0.12 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00,0.00 |

| Gender (ref=female) | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02, 0.02 |

| Education | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 |

| Trait positive emotion | −0.02** | 0.01 | −0.04, −0.01 |

| Trait negative emotion | 0.13*** | 0.01 | 0.11, 0.15 |

| Current day stressor | 0.01** | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.02 |

| Current day positive emotion | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 |

| Current day stressor x current day positive emotion | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.05, −0.00 |

p<.05

p <.01

p <.001

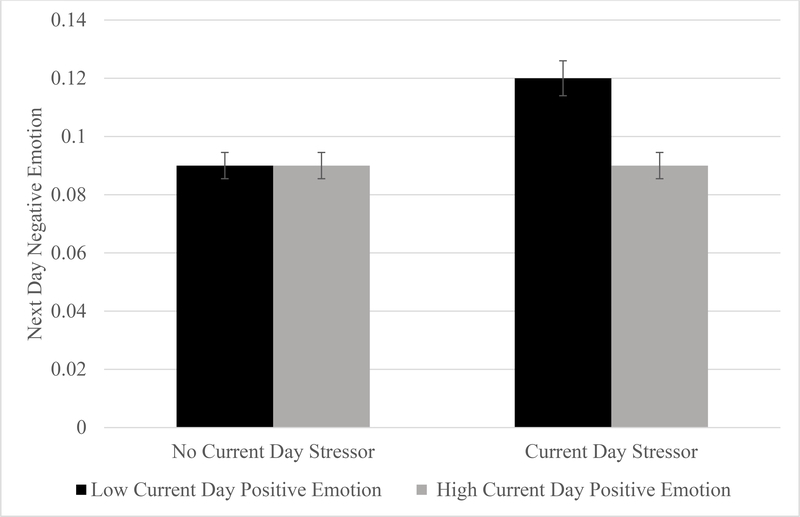

In line with our main hypothesis, an interaction occurred between a current day stressor and current day positive emotions, indicating that on days when people experienced a stressor and greater than average daily positive emotion, they experienced less negative emotion the following day compared to days when they experienced a stressor and lower than average daily positive emotion (γ = −0.02, p = .03, 95% CI [−0.05, −0.00]). Figure 1 shows the relationship between stressor occurrence on next day negative emotion and the interactive effects of high vs. low positive emotion experienced on the day of the stressor. Of note, this model adjusted for amount of stressor exposure and eliminated subsequent day stressors, indicating that higher than average positive emotion experienced during stressor days had a unique association on next day negative emotion. Furthermore, this association held after adjusting for trait levels of positive and negative emotion.

Fig 1.

Negative emotion the day after a stressor and low vs. high positive emotion (calculated as +/− 1 standard deviation from average level)

Follow-up Analyses

The above analyses examined the buffering effects of positive emotion experienced during a stressor on same day and next day negative emotion. If a stressor was reported that next day, the data were excluded from these analyses to ensure that any changes in next day negative emotion were not due to the presence of another stressor. Yet, positive emotions may also decrease the probability of experiencing a stressor the next day. To test this question, we ran a logistic regression to examine the effects of daily positive emotion on next day stressor experience. This model adjusted for trait positive and negative emotion, average numbers of stressors, same day stressors, and relevant demographic covariates. Results from the model showed that for every one-unit increase in positive emotion, the odds of experiencing a next day stressor decreased by 0.87 (95% CI = 0.78 to 0.99).

Discussion

This study examined the effects of daily positive emotion on days when people experience a stressful event on same and next day negative emotion. Results indicated that when people experienced higher than their average positive emotion the day of a stressor, they experienced less same day negative emotion as well as less negative emotion the following day. These relationships held after adjusting for trait positive and negative emotion. They were also less likely to experience a stressor the next day.

During times of stress, people experience both positive and negative emotion (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Scott, Sliwinski, Mogle, & Almeida, 2014). We found that on stressor days when people experience higher than their average positive emotion, they have less same day stressor-related negative emotion. This finding is in line with theories that view positive emotions as resources that can be drawn upon to facilitate adaptation and enhanced emotion regulation during times of stress (Frederickson, 1998, 2001). From this viewpoint, positive emotions may promote resistance to negative emotional responses to stress by providing a psychological breather from stressful situations and restoring depleted personal resources. Experiencing positive emotions during days when people also experience stressful events may be beneficial by interrupting and reducing negative emotions associated with a stressor.

We also found that on stressor days when people experience higher than average positive emotion, they have less increases in negative emotion the next day. This suggests that daily positive emotion can facilitate quicker recovery from stressors by helping individuals more quickly return to a baseline negative emotion and undo the effects of the stressful event. One potential explanation is that positive emotion on days of stress serve as motivators that help people cope with a stressor. When people experience positive emotions during times of stress, this may bolster their ability to use coping strategies such as positive reappraisal in order to maintain positive emotions and decrease negative emotions after a stressor is over (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000).

Additionally, findings held even after adjusting for trait levels of positive emotion. Both trait positive emotion and daily positive emotion are beneficial to well-being and predict better life outcomes (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Pressman & Cohen, 2005). One implication for this finding is that traits and skills that help people generate daily positive emotions may be particularly helpful for emotional recovery from stress. For example, daily positive emotions may be one way through which traits such as optimism are linked with better recovery from stressful events (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010).

The relationship between daily positive emotion and negative emotion has important implications for several aspects of health and well-being. Heightened negative emotional reactivity and prolonged recovery as a result of daily stress are associated with poor health behaviors such as sleep habits (Thomsen, Mehlsen, Christensen, & Zachariae, 2003) and worse physical health later in life (Leger et al., 2018). Sustained negative emotions are tied with perseverative cognitions such as rumination and worry (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008) and are implicated in mood and anxiety disorders (Watson, Clark, & Carey, 1988). Positive emotions, on the other hand, are predictive of several desirable outcomes including better health, productivity, and well-being (Ong, 2010). By attenuating negative emotional reactivity and hastening recovery from daily stressors, positive emotions may be contributing to better health and well-being.

Limitations and Future Directions

The main limitation in this study is that people were asked about emotion and stressors over the past 24 hours. As such, stressors and emotion were not measured when the stressors occurred, and retrospective reports were used to calculate same day and next day stressor related emotion. One potential limitation of this approach is that stressors had to be a certain level of importance for a person to recall a given event as a stressor. More minor stressors such as a brief negative exchange may be quickly forgotten about and go unreported. It is also possible that report biases may have led to spurious relationships between people’s reports of stressors and emotion. Furthermore, because questions about stressors and emotion were asked in the same interview, we cannot tease apart any temporal sequence for emotion and stressors. However, next day negative emotion does take place after the assessment of stressors and daily positive emotion. Therefore, we were able to conclude that positive emotions experienced on days of stress relate to negative emotions experienced the next day.

In addition, we could not be certain if positive emotions occurred during, before, or after the stressor occurred. Thus, our interpretation of the relationship between stressors, positive emotion, and stressor-related negative emotion were limited to the interplay of these factors on the daily level. For example, if positive emotions reduce next day negative emotion by speeding up emotional recovery from a stressor, then it could be that positive emotions experienced right after a stressful event occurs are more beneficial to speeding emotional recovery than positive emotions experienced before or during that event. However, if positive emotions are used as resources that can help people regulate their emotions during times of stress, then it could be that positive emotions experienced before or during a stressful event are most beneficial. Future momentary sampling studies should produce more fine-grained analyses to capture positive emotions experienced at different points before, during, or after a stressor and assess how these differences relate to subsequent negative emotions.

Finally, even though participants were selected from a community-based cohort of adults, most of the participants were Caucasian and had more education and a higher socioeconomic status than the average American. Future studies should specifically examine minority groups and individuals of lower income levels given that the relationship between daily stressor and emotional experience may be different for various groups of people.

Conclusion

Positive emotions are beneficial during times of stress. The current study demonstrated that one way through which positive emotions are beneficial is through their relationship with same day and next day negative emotion. If people experienced greater positive emotions on days of stress, then they also reported less same day negative emotion and less negative emotion the following day. This study demonstrates that not only do daily positive emotions provide a buffer against same day negative emotional consequences of daily stress, but that they also are related to decreases in negative emotion a full day later.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Aging and the National Institutes of Health by grants awarded to Susan Charles (R01AG042431) and to David M. Almeida (R01 AG019239).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Almeida DM, McGonagle K, & King H (2009). Assessing daily stress processes in social surveys by combining stressor exposure and salivary cortisol. Biodemography and Social Biology, 55, 219–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Wethington E, & Kessler RC (2002). The daily inventory of stressful events an interview-based approach for measuring daily stressors. Assessment, 9, 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, & Schilling EA (1991). Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality, 59, 355–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, & Reynolds AL (2011). Race-related stress, racial identity status attitudes, and emotional reactions of black americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 156–162. 10.1037/a0023358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, & Segerstrom SC (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879–889. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Hamrick N, Rodriguez MS, Feldman PJ, Rabin BS, & Manuck SB (2000). The stability of and intercorrelations among cardiovascular, immune, endocrine, and psychological reactivity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 22, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulk KE, Gloria CT, Cance JD, & Steinhardt MA (2012). Depressive symptoms among US military spouses during deployment: The protective effect of positive emotions. Armed Forces & Society, 38, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Moskowitz JT (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55, 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In Devine P & Plant A (Eds.) Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–53). Burlington: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Levenson RW (1998). Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiovascular sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 12, 191–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Mancuso RA, Branigan C, & Tugade MM (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 24, 237–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, & Matthews KA (2003). Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 10–51. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, … & Zaslavsky AM (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Kanner AD, & Folkman S (1980). Emotions: A cognitive-phenomenological analysis. In Plutchik R & Kellerman H (Eds.), Theories of Emotion (pp. 189–217). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leger KA, Charles ST, & Almeida DM (2018). Let it go: lingering negative affect in response to daily stressors can impact physical health years later. Psychological Science. Advance Online Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King L, & Diener E (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Shmueli-Blumberg D, Acree M, & Folkman S (2012). Positive affect in the midst of distress: implications for role functioning. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 22, 502–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, & Kolarz CM (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1333–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, & Lyubomirsky S (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD (2010). Pathways linking positive emotion and health in later life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, & Bergeman CS (2004). The complexity of emotions in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, & Wallace KA (2006). Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 730–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, & Cohen S (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 925–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, Mogle JA, & Almeida DM (2014). Age, stress, and emotional complexity: Results from two studies of daily experiences. Psychology and Aging, 29, 577–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski MJ, Almeida DM, Smyth J, & Stawski RS (2009). Intraindividual change and variability in daily stress processes: Findings from two measurement-burst diary studies. Psychology and Aging, 24, 828–840. 10.1037/a0017925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen DK, Mehlsen MY, Christensen S, & Zachariae R (2003). Rumination—relationship with negative mood and sleep quality. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, & Fredrickson BL (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 320–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Carey G (1988). Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Affleck GG, Tennen H, Reich JW, & Davis MC (2005). Dynamic approaches to emotions and stress in everyday life: Bolger and Zuckerman reloaded with positive as well as negative affects. Journal of Personality, 73, 1511–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra A, Smith B, Affleck G, & Tennen H (2001). Examinations of chronic pain and affect relationships: applications of a dynamic model of affect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 786–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]