Abstract

Objective:

Using a legal standard for scrutinizing the regulation of food label claims, this study assessed whether consumers are misled about whole grain (WG) content and product healthfulness based on common product labels.

Design:

First, a discrete choice experiment used pairs of hypothetical products with different amounts of WG, sugar, and salt to measure effects on assessment of healthfulness; and, second, a WG content comprehension assessment used actual product labels to assess respondent understanding.

Setting:

Online national panel survey.

Participants:

For a representative sample of U.S. adults (n=1030), survey responses were collected in 2018 and analyzed in 2019.

Results:

First, 29–47% of respondents incorrectly identified the healthier product from paired options, and respondents who self-identified as having difficulty understanding labels were more likely to err. Second, for actual products composed primarily of refined grains, 43–51% of respondents overstated the WG content, while for one product composed primarily of WG, 17% of respondents understated the WG content.

Conclusions:

The frequency of consumer misunderstanding of grain product labels was high in both study components. Potential policies to address consumer confusion include requiring disclosure of WG content as a percentage of total grain content or requiring disclosure of the grams of whole grains versus refined grains per serving.

Keywords: whole grains, food labels, consumer confusion, nutrition policy

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological evidence suggests that high consumption of whole grains (WG) protects against cardiovascular disease(1–3), type 2 diabetes(4,5), cancer(1–3,6), and total mortality(1–3). In 1999, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognized the health benefits of WG by authorizing a health claim linking WG intake with reduced risk of heart disease and cancer(7). The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) recommends that consumers “make at least half of grains whole grains”(8), which is stronger than the 2000 DGA recommendation to consume “a variety of grains daily, especially whole grains”(9). Likewise, the American Cancer Society recommends choosing “whole grains in preference to refined grain products”(10).

Food manufacturers have developed and marketed many new products with increased WG content, but they also use WG claims on less healthful products. In addition, the terms “wheat,” “multigrain,” or “made with whole grain,” may appear on products whose grain content comes primarily from refined grains. Previous research found that subsets of consumers have difficulty assessing WG content from food labels(11,12). In light of the foregoing, the Center for Science in the Public Interest petitioned FDA to require disclosure of the refined grain and WG content on any product whose label makes a WG content claim(13). Moreover, members of Congress proposed a bill that, if enacted, would require disclosure of WG content as a percentage of total grain content(14).

Policymakers seeking to enhance labeling requirements for WG claims must ensure that a proposed regulation does not violate the First Amendment of the Constitution, which protects commercial speech, including labeling(15). Courts use two separate legal tests to determine if a regulation of commercial speech violates the First Amendment depending on whether the government seeks to require disclosure of factual information(16) or restrict commercial speech(15). The government may require the disclosure of purely factual and “uncontroversial” information about the product itself under the Zauderer test, as long as it is reasonably related to a governmental interest and is not unjustified or unduly burdensome(17,18). Valid government interests include preventing consumer deception and promoting health(19). Conversely, the government may ostensibly restrict commercial speech under the Central Hudson test if the restriction directly advances a substantial governmental interest and is not more extensive than necessary to serve that interest(20). However, the Supreme Court has not upheld a commercial speech restriction under Central Hudson since 1995. Nonetheless, the Court has consistently maintained that the government may regulate misleading or deceptive commercial speech(19).

The Supreme Court has distinguished among three types of misleading or deceptive commercial speech: inherently misleading, actually misleading, and potentially misleading. Whole grain labels are not likely to be considered “inherently” misleading, because this has been found when terms have no inherent meaning(21). For labels that are merely “potentially” misleading (meaning that the information can be presented in a way that is not misleading), the government may order correction, revision, or increased factual disclosures, but it cannot prohibit the claims(22). The Supreme Court has stated that “actually” misleading speech occurs when empirical evidence proves that the speech is “misleading in practice,” and the government therefore may restrict such speech(22,23).

To assess the legal feasibility of proposals to regulate WG labels, it is essential to have better empirical information(19). Thus, to measure the extent of consumer understanding and misunderstanding of grain product labels and their impact on consumer assessment of product healthfulness for a representative sample of U.S. adults, this study uses an online discrete choice experiment with hypothetical products, and survey questions about labels for actual products.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study had two main components. First, in a discrete choice experiment, respondents were shown paired hypothetical products, with and without WG labels, and were asked, “Which product is healthier?” In each pair, one product was nutritionally superior or inferior based on the disclosed nutrition information. Second, in a WG content comprehension assessment, respondents were shown real products with various WG content claims and were asked to identify the relative amount of WG. In addition, we asked 5 questions with Likert scale options for agreement/disagreement with statements about familiarity with or difficulty using WG labels (e.g., “I find it difficult to determine which products contain whole grain”).

Sample

The sample was recruited from U.S. adult members of a large international panel from Survey Sampling International (SSI) in 2018. The target sample size for this study was 1000, with sub-targets by race and ethnicity to match the U.S. adult population. Members of the ongoing customer research panel were contacted by SSI and offered the opportunity to respond to our online survey, for which they were compensated by SSI. From the commercial survey panel, the recruited sample was chosen to match demographic characteristics of the U.S. adult population by age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education attained, and household income in 7 broad categories.

Discrete Choice Experiment

Each respondent was asked about one pair of hypothetical products in each of three product categories (cereal, crackers, and bread). The respondent was shown the mocked up front-of-pack (the principal display panel) and a Nutrition Facts Panel and ingredient list identical to those required by the FDA for a side-by-side pair of hypothetical products (Online Supplemental Figures 1–3). The left or right position was assigned at random. The “no WG label” product had no claim on the front of pack but had higher WG content according to the ingredients list and higher fiber content according to the Nutrition Facts Panel. The “WG label” product had a WG content claim on the front of pack but lower WG content than the other option and had other nutritional disadvantages (e.g., higher sugar) according to the ingredients list and Nutrition Facts Panel, as noted below. From each pair, respondents were asked to choose which product was “healthier,” with three multiple choice options (“A”, “equally healthy”, or “B”). By design, the “no WG label” option was the healthier option, while the equal and WG label options were less healthy and thus incorrect. Similar to the large discrete choice literature in which respondents face a tradeoff between a favorable characteristic and higher price(24), this experiment assessed how respondents balanced the appeal of the WG label on the front of pack against the information from the ingredients list and Nutrition Facts Panel.

Within each of the three product categories, there were three variations for the front-of-pack WG label (the cereal and cracker categories had “made with whole grains,” “multigrain,” and a WG stamp; the bread category had “multigrain,” “wheat,” and a WG stamp). Each respondent was shown just one randomly-selected variation. For example, for the cereal category, the “no WG label” had WG corn as the third ingredient, while the “WG label” products had more sugar and WG corn as the sixth ingredient.

We conducted a balance analysis to confirm no significant differences in demographic variables across the randomly assigned label variations and left/right position of the label. For descriptive analysis, we estimated frequencies for the choice of healthier label and cross-tabulations with the categorical question about self-reported difficulty determining which products contain WG. For multivariate analysis, we used an ordered logit model to test hypotheses and to estimate associations between explanatory variables and the propensity to select an incorrect label. The outcome variable was coded 1 (unlabeled), 2 (equally healthy), 3 (labeled), ordered from most correct to most incorrect. Coefficients in the ordered logit model represent the effect of explanatory variables on a latent variable, which determines the log-odds of choosing the next highest value of the outcome variable (for example, choosing the equally healthy option over the unlabeled option or choosing the labeled option over the equally healthy option). The ordered logit model was also used to test whether respondent choices were associated with randomly assigned left/right position (which should be irrelevant), with the three product label variations, and with the questions about familiarity with or difficulty using WG labels. Control variables in an initial extended multivariate model were age, sex, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, and income; after excluding variables that were statistically insignificant for all three product categories, we retained age, race, and education category in the main analysis.

WG Content Comprehension

For the 4 real grain products, each respondent was shown an image of the actual product packages from the manufacturers’ websites, with the accompanying Nutrition Facts Panel and ingredient list. The respondents were asked to choose the best option on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “All the grain is whole grain” to “There is little or no whole grain”, with a fifth option indicating “other” responses. The 4 products were the following: (a) a “honey wheat” bread that had “unbleached enriched flour” as first ingredient and <1g fiber, (b) a “multigrain” cracker with “enriched flour” as the first ingredient and <1g fiber, (c) an apple cinnamon oat cereal whose package noted “first ingredient whole grain oats” and “simply made gluten free”, with “whole grain oats” as first ingredient and 2g fiber, and (d) a “12 grain” bread with “enriched wheat flour” as the first ingredient and 3g fiber.

Analyses were conducted in 2018 and 2019 using Stata v14 (Stata Corp). The survey was reviewed and approved by the [University name omitted] IRB. Each respondent gave informed consent on the first screen of the online survey.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The survey respondents (n=1030) had a similar distribution in age, sex, race, and Hispanic ethnicity as the U.S. adult population in 2017 (Table 1). The survey respondents were more likely than the general U.S. adult population to have a college or graduate degree (44.6% versus 29.5%), and slightly more likely to have mid-level household annual income ($50k-$75k) and less likely to have very high household annual income (above $150k). The balance analysis confirmed that sample characteristics were not significantly different across the randomly assigned left/right label position and the three randomly assigned label variations in the discrete choice experiment (Online Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample and U.S. adult population.

| Frequencies (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sample | USA (2017)a | |

| n | 1030 | 3190040 |

| Age | ||

| 18 to 24 years old | 9.5 | 12.2 |

| 25 to 34 years old | 19.8 | 17.8 |

| 35 to 44 years old | 20.3 | 16.4 |

| 45 to 54 years old | 17.7 | 16.8 |

| 55 to 64 years old | 16.1 | 16.7 |

| Age 65 or more | 16.6 | 20.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 47.2 | 48.7 |

| Female | 52.8 | 51.3 |

| Race | ||

| White / Caucasian | 77.3 | 74.0 |

| Black / African American | 14.0 | 12.3 |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 4.6 | 6.0 |

| American Indian / Alaska Native | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Other race | 3.2 | 6.9 |

| Prefer not to say | 0.2 | n/a |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non Hispanic/Latino | 88.2 | 84.0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 11.1 | 11.9 |

| Prefer not to say | 0.8 | 4.1 |

| Education | ||

| High school degree or less | 29.5 | 45.0 |

| Some college | 25.9 | 24.3 |

| College degree | 30.0 | 18.6 |

| Graduate school / professional degree | 14.6 | 10.9 |

| Household Income | ||

| Less than $25,000 | 20.7 | 20.3 |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 20.7 | 21.5 |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 23.5 | 16.5 |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 13.8 | 12.5 |

| $100,001–$150,000 | 14.9 | 14.5 |

| More than $150,000 | 5.5 | 14.7 |

| Prefer not to say | 0.97 | n/a |

U.S. data from Census, 2018 (income variables) and Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), 2018 (all other variables).

Discrete Choice Experiment

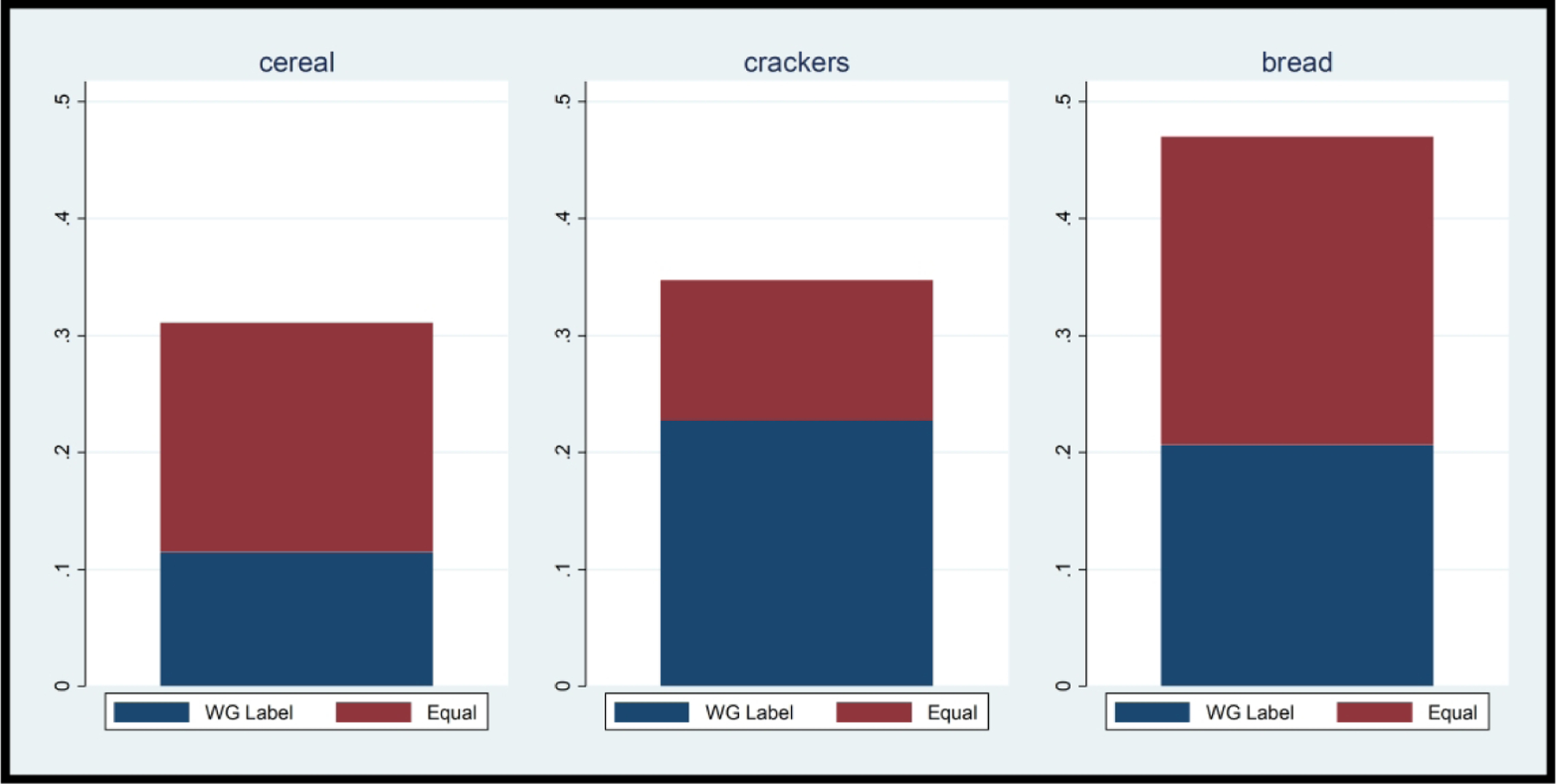

Although by design the “no WG label” option had more actual WG content, substantial fractions of respondents incorrectly identified the “WG label” option as healthier or chose the “equally healthy” option (Figure 1). Disaggregated results and standard errors are in Online Supplemental Table 2 and Online Supplemental Figure 1. For the cereal category, 31.1% of respondents incorrectly chose the “equally healthy” or “WG label” options, with no significant difference across the 3 variations on WG labels (made with whole grains, multigrain, and the WG stamp). For the crackers category, a substantial percent also incorrectly answered, and there were modest but statistically significant differences across the three variations: the frequency of incorrectly choosing the “equally healthy” or “WG label” options was 36.5% for the made with WG label, 38.2% for the multigrain label, and 29.2% for the WG stamp. For the bread category, 47.0% of respondents incorrectly chose the “equally healthy” or “WG label” options, and, as with the cereal category, there was no significant difference across the 3 variations (multigrain, wheat, and WG stamp).

FIGURE 1.

Relative frequency of incorrect responses (stating that the WG labeled option was healthier or both options were equally healthy, in trials of hypothetical product pairs for which the unlabeled option was healthier). Online Supplemental Table 1 provides standard errors, and Online Supplemental Figure 1 provides disaggregated results for 3 randomly-assigned variations of the product labels.

There was wide variation in self-reported familiarity with or difficulty using WG labels (Table 2). More than 60% strongly or somewhat agreed with a statement that they purposefully choose WG products. One-third strongly or somewhat agreed with a statement that they find it difficult to determine which products contain WG. Higher agreement with this latter statement about “difficulty” was associated with higher frequency of choosing the incorrect “equally healthy” or “WG label” options in the discrete choice experiment (Table 3). For example, for the cereal category, among those who strongly agreed that they had difficulty, just 47.7% correctly chose the “no WG label” option; among those who strongly disagreed that they had difficulty, 72.8% correctly chose the “no WG label” option (Table 3).

Table 2.

Response frequencies for agreement with behavior and attitude statements (%) (n=1036)

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Somewhat Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I find it difficult to determine which products contain whole grain.” | 11.2 | 22.6 | 27.4 | 26.6 | 12.2 |

| “I rely on statements made on the front of food packages to find healthy food.” | 18.2 | 30.8 | 18.8 | 19.3 | 12.9 |

| “I rely on the nutrition and ingredient information on food packages to find healthy food.” | 39.6 | 44.8 | 10.9 | 2.9 | 1.8 |

| “When buying certain foods, I purposefully choose whole grain products.” | 23.5 | 38.8 | 23.2 | 9.8 | 4.8 |

| “Eating more whole grains and less refined grains can help reduce the risk of heart disease and some cancers.” | 36.3 | 40.2 | 19.1 | 2.7 | 1.7 |

Table 3.

Relative frequency of correct responses and incorrect responses, disaggregated by agreement with a statement that “I find it difficult to determine which products contain whole grain.”a

| Cereal (n=1030) | Cracker (n=1016) | Bread (n=1022) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement with statement that “I find it difficult to determine which products contain whole grain”: | Which product is healthier? | Which product is healthier? | Which product is healthier? | |||||||||||||||

| No WG Label Claim | Equal | WG Label Claim | No WG Label Claim | Equal | WG Label Claim | No WG Label Claim | Equal | WG Label Claim | ||||||||||

| Correct | Incorrect | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | Incorrect | ||||||||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |

| Strongly Agree | 47.7 | 4.8 | 27.9 | 4.3 | 24.3 | 4.1 | 41.1 | 4.7 | 34.8 | 4.5 | 24.1 | 4.1 | 36.3 | 4.5 | 25.7 | 4.1 | 38.1 | 4.6 |

| Somewhat Agree | 62.8 | 3.2 | 26.0 | 2.9 | 11.3 | 2.1 | 61.2 | 3.2 | 26.9 | 2.9 | 11.9 | 2.2 | 49.6 | 3.3 | 24.3 | 2.8 | 26.1 | 2.9 |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 66.2 | 2.8 | 22.1 | 2.5 | 11.7 | 1.9 | 64.9 | 2.9 | 23.3 | 2.5 | 11.8 | 1.9 | 50.0 | 3.0 | 19.4 | 2.4 | 30.6 | 2.8 |

| Somewhat Disagree | 84.0 | 2.2 | 11.3 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 77.2 | 2.5 | 16.5 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 1.5 | 63.3 | 2.9 | 18.5 | 2.3 | 18.2 | 2.3 |

| Strongly Disagree | 72.8 | 4.0 | 12.8 | 3.0 | 14.4 | 3.2 | 68.8 | 4.2 | 16.8 | 3.4 | 14.4 | 3.2 | 59.2 | 4.4 | 16.8 | 3.4 | 24.0 | 3.8 |

Images for the hypothetical product comparison are in Online Supplemental Figure 2, and results for 4 more attitude statements are available on request.

In the multivariate analysis, for all three product categories, ordered logit estimates showed that the propensity to choose an incorrect unlabeled option was higher for younger respondents with high school or less education, who were Black or African American, and who self-reported more difficulty determining the WG content of foods (Table 4). In the cereal category, for example, the ordered logit coefficient of −0.449 indicates that older adults (aged 65+ y) were approximately 45% less likely than younger adults (aged 18–24 y) to choose a more incorrect outcome category (i.e. choosing the equally healthy option over the correct unlabeled option or choosing the labeled option over the equally healthy option). Hypothesis tests are reported in Online Supplemental Table 6.

Table 4.

Ordered logit estimates for propensity to respond incorrectly (stating that both options were equally healthy or the WG labeled option was healthier) when comparing hypothetical product pairs for which the unlabeled option was healthier.a

| Cereal | Crackers | Bread | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory Varb | Coefd | SE | Coefd | SE | Coefd | SE |

| Label variation 1c | (comparison) | (comparison) | (comparison) | |||

| Label variation 2 | 0.135 | 0.173 | 0.022 | 0.161 | 0.008 | 0.152 |

| Label variation 3 | −0.102 | 0.179 | −0.351 | 0.170 | 0.087 | 0.153 |

| “Difficult to determine” which products contain WG | ||||||

| strong disagreement | (comparison) | (comparison) | (comparison) | |||

| some disagreement | −0.603 | 0.266 | −0.297 | 0.246 | −0.021 | 0.221 |

| neither | 0.321 | 0.242 | 0.210 | 0.235 | 0.457 | 0.218 |

| some agreement | 0.310 | 0.247 | 0.256 | 0.239 | 0.268 | 0.221 |

| strong agreement | 0.936 | 0.275 | 0.963 | 0.267 | 0.687 | 0.254 |

| 18 to 24 years old | (comparison) | (comparison) | (comparison) | |||

| 25 to 34 years old | 0.442 | 0.264 | 0.513 | 0.259 | 0.105 | 0.244 |

| 35 to 44 years old | 0.355 | 0.264 | 0.339 | 0.259 | −0.013 | 0.242 |

| 45 to 54 years old | −0.153 | 0.278 | −0.228 | 0.270 | −0.479 | 0.249 |

| 55 to 64 years old | −0.411 | 0.296 | −0.122 | 0.276 | −0.511 | 0.258 |

| Age 65 or more | −0.449 | 0.298 | −0.815 | 0.303 | −0.715 | 0.261 |

| Black / Afr. Amer. | (comparison) | (comparison) | (comparison) | |||

| Asian / Pacific Islander and Other | 0.164 | 0.271 | −0.339 | 0.277 | −0.009 | 0.256 |

| White / Caucasian | −0.368 | 0.193 | −0.430 | 0.185 | −0.598 | 0.181 |

| College degree | (comparison) | (comparison) | (comparison) | |||

| Grad / prof. degree | 0.088 | 0.233 | 0.110 | 0.224 | 0.342 | 0.205 |

| HS or less | 0.496 | 0.181 | 0.421 | 0.178 | 0.739 | 0.164 |

| Some college | 0.169 | 0.191 | 0.214 | 0.184 | 0.367 | 0.171 |

| Cutpoint 1 (Equal versus Unlabeled) | 0.929 | 0.364 | 0.550 | 0.351 | 0.061 | 0.335 |

| Cutpoint 2 (Labeled versus Equal) | 2.273 | 0.372 | 2.036 | 0.359 | 1.045 | 0.336 |

| Obs | 1015 | 1008 | 1013 |

Outcome variable coded 1 (unlabeled), 2 (equally healthy), 3 (WG labeled).

For simple comparisons across the 3 label variations, a reduced model without the “difficult to determine” question is presented in Online Supplemental Table 3. An extended model is presented in Online Supplemental Table 4 (the additional variables were statistically insignificant for all three product categories).

WG label variations for the cereal and cracker categories: (1) “made with whole grains,” (2) “multigrain,” and (3) a WG stamp; and for the bread category: (1) “multigrain,” (2) “wheat,” and (3) a WG stamp.

Coefficient shows effect of each explanatory variable on the log-odds of having the next higher value of the outcome variable (i.e. choosing equally healthy over unlabeled).

WG Content Comprehension

Respondents showed substantial difficulty in identifying the WG content of 4 actual products found in the marketplace (Table 4). For 3 products (the honey wheat bread, multigrain cracker, and farmhouse 12-grain bread), the correct answers are “less than half” or “little or none” of the grain is whole grain, because non-WG flour was the first ingredient and whole wheat flour was a lesser ingredient. Yet, the frequency of incorrectly stating that “all the grain is whole grain” or “half or more than half is whole grain” was 43% for the honey wheat, 41% for the multigrain cracker, and 51% for the farmhouse 12-grain bread. For the fourth product, an apple cinnamon oat cereal, the correct answer was “half or more than half the grain is whole grain,” because it did have WG oats as the first ingredient and non-WG corn starch was a lesser ingredient. For this product, 37% responded correctly and another 45% responded that “all the grain is whole grain” (which may be because corn starch is more difficult to identify as relevant to grain content from the ingredients list), while 17% of respondents underreported the WG content (Table 5).

Table 5.

Whole grain content comprehension questions for actual products with varying amounts of WG contenta

| Frequency of Respondent Choices (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Description | Actual Whole Grain Content | “All the grain is whole grain” | “Half or more than half the grain is whole grain” | “Less than half the grain is whole grain” | “There is little or no whole grain” | “Other” |

| Honey Wheat Bread | Less than half. Whole wheat flour (6th ingredient) is less than unbleached enriched wheat flour (1st ingredient). | 17.89 | 24.95 | 22.44 | 30.46 | 4.26 |

| Multigrain Cracker | Less than half. Whole wheat flour (5th ingredient) is less than enriched wheat flour (1st ingredient). | 14.33 | 26.62 | 30.40 | 25.56 | 3.10 |

| Farmhouse 12 Grain Bread | Less than half. Whole wheat flour (3rd ingredient) is less than enriched wheat flour (1st ingredient). | 22.14 | 29.13 | 27.86 | 18.16 | 2.72 |

| Apple Cinnamon Oat Cereal | Half or more. WG oats (1st ingredient) is more than corn starch (3rd ingredient). | 45.05 | 36.60 | 11.84 | 4.85 | 1.65 |

Product images are in Online Supplemental Figure 4.

WG, Whole Grain

DISCUSSION

For a survey sample of U.S. adults, this study investigated consumer understanding of WG labels using, first, a discrete choice experiment with assigned pairs of hypothetical products and, second, a WG content analysis of consumer understanding of WG labels for actual products. The first analysis found that, depending on the product and label, 29–47% of respondents incorrectly identified the healthiest product from paired options. The second analysis found that 17–51% of respondents had difficulty identifying the WG content of actual grain products.

In the discrete choice analysis, respondents faced a tradeoff between the appeal of WG content marketing (as indicated by front-of-pack labels) and the actual WG content and other nutritional advantages (as indicated by the ingredients list and Nutrition Facts Panel). For the cereal and crackers category, 31% and 35% of respondents, respectively, appeared to be misled by the front-of-pack label, incorrectly stating that both options were “equally healthy” or that the “WG label” option was healthier. For the bread category, the fraction of respondents that appeared to be misled was higher; 47% chose the incorrect options. The tendency to choose the incorrect response was greater for respondents with less education or who reported having difficulty determining the WG content of products. In this sense, the consumers who are most likely to be misled by WG labels are themselves aware of the problem.

In the WG content analysis, consumers were shown images of the front-of-pack, ingredients list, and Nutrition Facts Panel for actual products. For 3 products that really had less than half the grains as WG, but which had potentially confusing references to “wheat” or “multigrain”, 43% to 51% of respondents overstated the WG content. Conversely, for the 4th product, a whole-grain oat cereal that really did have WG as the first grain ingredient (ordered by weight), 17% of respondents erred in the opposite direction and understated the WG content (they stated that less than half the grain was whole grain, when actually more than half the grain was whole grain).

This study corroborates previous research. An in-depth small-sample study of 89 older adults found that 37% and 34%, respectively, incorrectly identified a WG cereal and a cracker product(11). For a bread product that was not WG, only 19% correctly identified it as a refined grain product. Similar to our discrete choice analysis, subjects in that study appeared to be misled by the claims on the front of the package. A different study of 387 socioeconomically diverse subjects in California used side-by-side comparisons of products in which 1 choice had less sodium, fewer calories, or more fiber(25). That study found poor accuracy in using label information to compare nutritional qualities of cereal products, and analysis of eye tracking showed lower accuracy associated with more attention to front-of-pack information about calories, fat, and sodium, and higher accuracy associated with more attention to fiber and sugar information. Higher accuracy also was associated with greater nutrition knowledge. As in the present study, there was evidence that subjects can be misled by marketing information on the front of food labels.

The current study has potential policy implications for Federal Trade Commission (FTC) oversight over false, unfair, and deceptive advertising, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversight over food labeling, and for the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), which are the basis for government food programs. The FTC is responsible for identifying deceptive advertising, which includes representations or omissions that are likely to mislead consumers and affect consumers’ decisions about a product(26). The FTC often relies on survey evidence to determine if “at least a significant minority of reasonable consumers” were misled by a representation or omission(27). Courts have upheld the FTC’s finding of deception when far fewer respondents (10.5% to 17.3%) were found to be misled than in the current study(28). In one case comparable to the WG findings here, survey evidence revealed 20–36% of the respondents were misled by the term “biodegradable” on plastic containers(29). The Sixth Circuit found that a significant minority of consumers were misled. Similarly, in the case of WG labeling, survey evidence of consumer misunderstanding may indicate that labels are deceptive.

Courts are increasingly skeptical of whole grain-related claims. In one case, a court found that even if the name of Subway’s breads, 9-Grain Wheat and Honey Oat, are “literally true,” it is a question for the fact-finder (e.g., the jury) whether “the manner in which Subway markets its … breads could have a tendency to mislead a reasonable consumer” about the breads’ WG content(30). Likewise, the Second Circuit found that a reasonable consumer could be misled by Kellogg Company’s Cheez-It crackers, labeled “whole grain” or “made with whole grain,” to “believe that the grain in whole grain Cheez-Its was predominantly whole grain”(31).

The FDA is responsible for regulating the labels of the majority of food products in the U.S., including WG products. Claims similar to those studied here may be considered “actually misleading” and thus amenable to prohibition in the contexts in which they were tested(32). Short of such prohibition, potential policy options include prescribing the ingredients for WG products as the FDA has done for whole wheat macaroni products(33); requiring disclosure of WG content as a percentage of total grain content(14); or requiring disclosure of the grams of WG versus refined grains per serving(13). These options would be in line with FDA’s current regulatory scheme and consistent with potential planned changes under its proposed Nutrition Innovation Strategy(34). The present study may inform the policy merits and legality of such proposals.

The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans noted that distinguishing WG from refined grains is especially important because Americans are currently consuming enough grains daily; however, over 40% are not consuming enough whole grains(8). Future DGAs may consider providing practical information to Americans on how to identify WGs or guide them to easy-to-identify WGs such as whole grain rice or oats, to support informed decisions when purchasing grain products. The DGAs influence nutrition policy beyond just consumer education, including nutrition standards in federal nutrition assistance programs and the Nutrition Facts Panel design, so the next DGA may contribute to greater clarity in food labeling policy for WGs.

This study had strengths and limitations. Our analysis used a large national U.S. sample (n=1030) with targets for race, Hispanic ethnicity, and sex that matched the U.S. adult population. However, high-education respondents were moderately over-represented. Participants in ongoing consumer panels had to volunteer to respond to an invitation to complete our survey, so it is not possible to estimate the denominator for a formal response rate, which is a threat to external validity. This sample offered reasonable cost and low implementation burden. In our discrete choice experiment, we randomly assigned three variations of WG product labels, but our product pairs had just one labeled and one unlabeled product within each product category. We randomly assigned left/right position, which had no significant effect, but we did not randomly assign other differences in the product pairs (color and hypothetical brand name). Future research might fully randomize all product differences. For the WG content analysis, our results apply to these 4 actual products, but these products reflect commonly found product characteristics in the marketplace.

CONCLUSION

This study confirms, through two distinct analyses, consumers have difficulty identifying the healthfulness and WG content of grain products. The high percentage of consumers misled by the front-of-package marketing indicates government could regulate WG claims and product names consistent with the First Amendment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Sarah Cronin1 for constructing the product images. She has approved this acknowledgment.

Financial Support: This study was supported by NIH/NIMHD 1R01MD011501. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

Ethical Standards Disclosure: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Tufts University IRB. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients on the first page of the online survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang B, Zhao Q, Guo W et al. (2018) Association of whole grain intake with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis from prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 72, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen GC, Tong X, Xu JY et al. (2016) Whole-grain intake and total, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nut 104, 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E et al. (2016) Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br Med J 353, i2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D et al. (2007) Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med 4, e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyro C, Tjonneland A, Overvad K et al. (2018) Higher Whole-Grain Intake Is Associated with Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes among Middle-Aged Men and Women: The Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Cohort. J Nutr 148, 1434–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R et al. (2011) Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br Med J 343, d6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration (1999) Health Claim Notification for Whole Grain Foods. https://www.fda.gov/food/labelingnutrition/ucm073639.htm (accessed April 2020).

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture (2015) 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/guidelines/ (accessed April 2020).

- 9.Kantor LS, Variyam JN, Allshouse JE et al. (2001) Choose a variety of grains daily, especially whole grains: a challenge for consumers. J Nutr 131, 473s–486s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M et al. (2012) American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin 62, 30–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Violette C, Kantor MA, Ferguson K et al. (2016) Package Information Used by Older Adults to Identify Whole Grain Foods. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 35, 146–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marquart L, Pham AT, Lautenschlager L et al. (2006). Beliefs about whole-grain foods by food and nutrition professionals, health club members, and special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participants/State fair attendees. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1856–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Center for Science in the Public Interest (2018) Re: FDA-2018-N-238; The Food and Drug Administration’s Comprehensive, Multi-Year Nutrition Innovation Strategy; Public Meeting; Request for Comments. In: Division of Dockets Management, US Food and Drug Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food Labeling Modernization Act of 2018, H.R.5425, 115th Cong (2018).

- 15.Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co., 514 U.S.476 (1995).

- 16.N.Y. State Rest. Ass’n v. N.Y. City Bd. of Health, 556 F.3d 114 (2nd Cir. 2009).

- 17.National Institute of Family & Life Advocates v. Becerra, 138 S. Ct. 2361 (2018).

- 18.Zauderer v Office of the Disciplinary Counsel, 471 US 626 (1985).

- 19.Pomeranz JL (2019) Abortion disclosure laws and the First Amendment: The broader public health implications of the Supreme Court’s Becerra decision. Am J Public Health 109, 412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Comm’n, 447 U.S. 557, 566 (1980).

- 21.Friedman v. Rogers, 440 U.S. 1 (1979).

- 22.In re R. M. J., 455 U.S. 191 (1982).

- 23.Peel v. Atty. Registration & Disciplinary Comm’n, 496 U.S. 91 (1990).

- 24.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M (2008) Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care. Vol 11. 1 ed: Springer; Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller LM, Cassady DL, Beckett LA et al. (2015) Misunderstanding of front-Of-package nutrition information on US food products. PLoS One 10, e0125306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Federal Trade Commission (1983) FTC Policy Statement on Deception. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/410531/831014deceptionstmt.pdf (accessed April 2020).

- 27.POM Wonderful, LLC vs. F.T.C., 777 F.3d 478 (D.C. Cir. 2015).

- 28.In re Telebrands Corp., 140 F.T.C. 278, 291 (2005), aff’d,, 457 F.3d 354 (4th Cir. 20006)

- 29.ECM Biofilms, Inc. v. FTC, 851 F.3d 599 (6th Cir. 2017).

- 30.Nat’l Consumer’s League v. Doctor’s Assocs., 2014 D.C. Super. LEXIS 15 (D.C. Super. Ct 2014).

- 31.Mantikas v. Kellogg Co., 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 34756 (2nd Cir. 2018).

- 32.In re R. M. J, 455 U.S. 191 (1982).

- 33.21 CFR 139.138 (2018).

- 34.Pomeranz JL, Lurie PG (2019) Harnessing the power of food labels for public health. Am J Prev Med 56, 622–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.