Abstract

Background

Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell (CART19) therapy holds great promise in the treatment of hematological malignancies. A high occurrence of cardiac dysfunction has been noted in children treated with CART19 therapy.

Objectives

We aimed to define the occurrence of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in adult patients treated with CART19 cells and assess the relationships between clinical factors, echocardiographic parameters, laboratory values, and cardiovascular outcomes.

Methods

Baseline clinical, laboratory and echocardiographic parameters were collected in 145 adult patients undergoing CART19 cell therapy. MACE included cardiovascular death, symptomatic heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, ischemic stroke and de novo cardiac arrhythmia. Baseline parameters associated with MACE were identified using Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression analysis.

Results

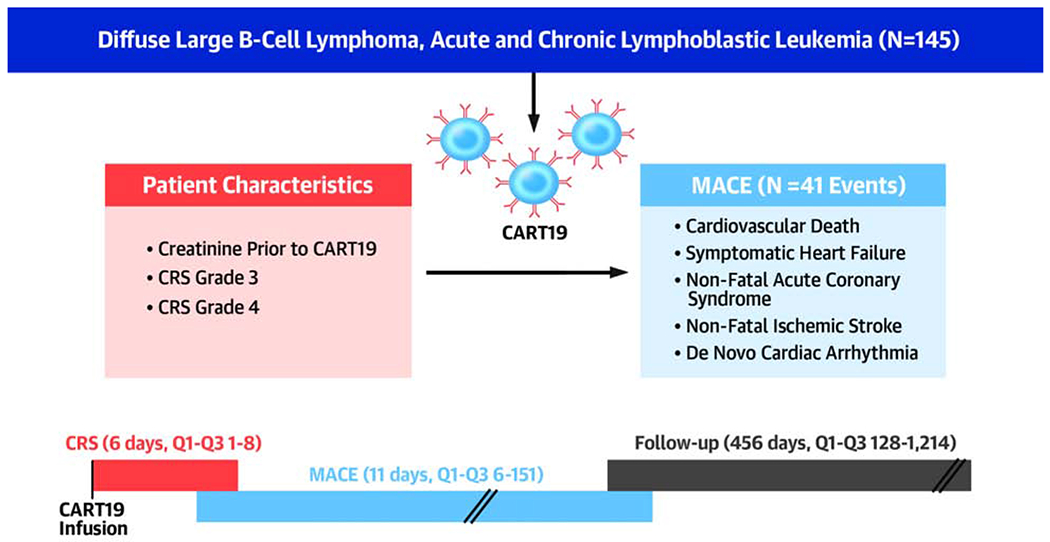

Thirty-one patients had MACE (41 events) at a median time of 11 days (Q1-Q3:6-151 days) after CART19 cell infusion. The median follow-up period was 456 days (Q1-Q3: 128-1214 days). Sixty-one patients died. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) occurred 176 times in 104 patients; the median time to CRS was 6 days (Q1-Q3: 1-8 days). The Kaplan-Meier estimates for MACE and CRS at 30 days were 17% and 53% respectively. The KM estimates for survival at 1 year was 71%. Multivariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression analysis determined that baseline creatinine and Grade 3 or 4 CRS were independently associated with MACE.

Conclusion

Patients treated with CART19 are at an increased risk of MACE and may benefit from cardiovascular surveillance. Further large prospective studies are needed to confirm the incidence and risk factors predictive of MACE.

Keywords: Cardiovascular, CART cells, Cardio-oncology

Condensed Abstract

We defined the occurrence of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in 145 adult patients treated with CART19 and assessed the relationships between clinical factors, echocardiographic parameters, blood biomarkers and cardiovascular outcomes in these patients. Thirty-one patients had 41 MACE. Multivariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression analysis demonstrated that baseline creatinine and Grade 3 or 4 CRS were independently associated with MACE. Patients treated with CART19 cells are at risk of MACE and may benefit from cardiovascular surveillance.

Introduction

Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell (CART19) therapy, first developed at the University of Pennsylvania, is a tremendous advance in the field of hematological malignancies. The patient’s own T cells are engineered to target CD19, an antigen frequently and highly expressed in some B cell malignancies, notably acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL)(1,2). In clinical trials, CART19 therapy has shown a remarkable response rate (70-90%) and durability of remission; in a chemotherapy-resistant DLBCL population, 65% of patients were relapse-free at one year (3–5). To date, there are two FDA-approved CD19 immunotherapies for refractory B-ALL and large B-cell lymphoma, tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) and axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta).

A frequent and potentially lethal side effect of CART19 cell therapy is cytokine release syndrome (CRS), with symptoms ranging from mild to high fever, severe hypotension and hypoxia, occurring usually within days after CART19 therapy. In a recent large systematic review and meta-analysis, CRS was reported in more than half of the patients treated with CART19 cells (6). Cytokine release syndrome is a systemic inflammatory response syndrome triggered in particular by release of large amounts of interleukin-6 (7). The release of cytokines induces fever, vascular leakage and potentially direct myocardial injury.

Cardiovascular complications and potential cardiotoxicity of CART19 cell therapy are especially relevant concerns in this patient population as they may have pre-existing cardiac dysfunction or risk factors (8) and/or received multiple previous cycles of cardiotoxic chemotherapy.

Cardiovascular complications of CART19 cell therapy have been reported in two retrospective studies in the pediatric population (1,9) and recently in a third retrospective study in adults (10). In 39 children with acute leukemia, Fitzgerald et al. (9) reported that more than one third of patients developed cardiovascular complications such as shock or cardiomyopathy. In the other study by Burstein et al. (1), 24 patients out of 98 children (24%) had hypotension requiring inotropic support. Of these 24 patients, 10 patients (50% of children who had an echocardiogram) demonstrated left ventricular systolic dysfunction. The cardiomyopathy was mostly reversible in these children. Left ventricular dysfunction in the pediatric heart, however, may be different in severity, reversibility and progression compared to the adult heart.

In the present study, we defined the rate of occurrence and the natural history of cardiovascular events in all consecutive adult patients treated with CART19 cell therapy. Clinical, laboratory and echocardiographic parameters were collected to investigate the association between these parameters and the cardiovascular outcomes of patients treated with CART19.

Methods

Identification of patients and endpoints

The study was conducted at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania (HUP) and was approved by the local institutional review board. All consecutive adult patients (≥18 years old) with CD19+ malignancy (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), ALL (acute lymphoblastic leukemia), CLL (chronic lymphoblastic leukemia)) treated with experimental and commercial CART19 cells at HUP between August 2010 and January 2019 were identified. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (11) were defined as cardiovascular death, symptomatic heart failure, non-fatal acute coronary syndrome, non-fatal ischemic stroke and de novo cardiac arrhythmia. In order to identify the occurrence of MACE, each chart was reviewed individually (BL). All MACE were recorded and defined using the ACC/AHA outcome definitions outlined for clinical trials by Hicks et al. (11). Symptomatic heart failure was identified when 3 or more of the following 4 criteria were met: symptoms of heart failure, clinical signs of heart failure on physical examination, laboratory or imaging/radiographic findings of heart failure (B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)/N-terminal pro-BNP, Kerley B-lines or pulmonary edema, pleural effusion, decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)), initiation of new treatment for heart failure (pharmacologic therapies such as diuretics and/or mechanical support). One or more symptoms of heart failure and two or more signs on physical examination were necessary for the diagnosis. Symptoms of heart failure were defined as dyspnea at rest or during exercise, decreased exercise capacity and symptoms of volume overload. Clinical signs on physical examination were defined as peripheral edema, ascites in the absence of hepatic disease, pulmonary crackles or rales, increased jugular venous pressure, S3 gallop and significant and rapid weight gain related to fluid retention. De novo cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation were identified on electrocardiogram (ECG). All cardiovascular events were adjudicated by two independent cardiologists blinded to all other clinical and quantitative echocardiographic data (BL and YK). A third cardiologist (MSC) further adjudicated if any disagreement occurred between the 2 initial reviewers. Signs and symptoms of heart failure arising concurrently with sepsis were excluded from MACE.

Cardiovascular risk factors and pre-existing cardiovascular (CV) disease were extracted manually from each electronic medical record. All baseline characteristics were reported at the time of or most proximal to CART19 infusion. Cardiovascular disease was defined by pre-existing coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, atrial fibrillation or stroke. Cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes were classified as present if both diagnosis and treatment were identified in the medical chart. Other cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and smoking history were also identified. Non-cardiac death was also reported and included death due to septic shock, multiple organ failure or progression of cancer. In order to minimize loss of follow-up from death, every patient was also searched in a national necrology database. Vital signs and laboratory results were extracted from the HUP electronic medical record.

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) events were reviewed and graded according to the latest ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome (12). CRS is defined into four grades according to symptoms and clinical status. CRS Grade 3 and 4 include temperature ≥38.0°C, hypotension requiring at least one vasopressor and/or hypoxia with high-flow oxygen supplementation, positive pressure or intubation.

Echocardiography Analysis

Echocardiographic images were extracted from the HUP database. Measurements were acquired by a single observer (BL) blinded to clinical data or the occurrence of MACE and reported from the average of three consecutive cardiac cycles using the recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. Left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated using the modified Simpson’s biplane method and left atrial volume was calculated using the biplane method (13).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are expressed as percentages and continuous data as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (25th and 75th percentiles). Normality was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Differences amongst patients with ALL, CLL and DLBCL were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test. Kaplan-Meier estimates at 30 days, 6 months and 12 months were also performed for each cancer subtype and MACE, CRS and survival rates. The Cumulative Incidence Function (CIF) was used to estimate the incidence of MACE and non-cardiac death.

The Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression analysis was used to determine the parameters associated with MACE in our population. All variables were tested with univariable analysis. Initially, clinically significant non-collinear variables with a p-value of <0.10 by univariable analysis were entered into a multivariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression. Multicollinearity was tested with the variance inflation factor. The decision was made to use a maximum of 4 variables (41 events, 1 parameter per 10 events) as to avoid model instability. In order to confirm the results, multivariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression was repeated with a stepwise regression using the backward elimination method using all variables with a p-value <0.10 by univariable analysis. All variables were subsequently re-entered individually into the final model, to assess for significance in the presence of the final model variables. Hazard Ratio (HR) are expressed with 95% confidence interval (CI). All CRS gradings were compared to “CRS Grade 0” as an indicator. Univariable and multivariable analysis were also confirmed with the Fine and Gray distribution hazard regression model in a competing risk regression model.

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) and R version ii386 3.5.0 (Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org/). A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients treated with CART19 cell therapy

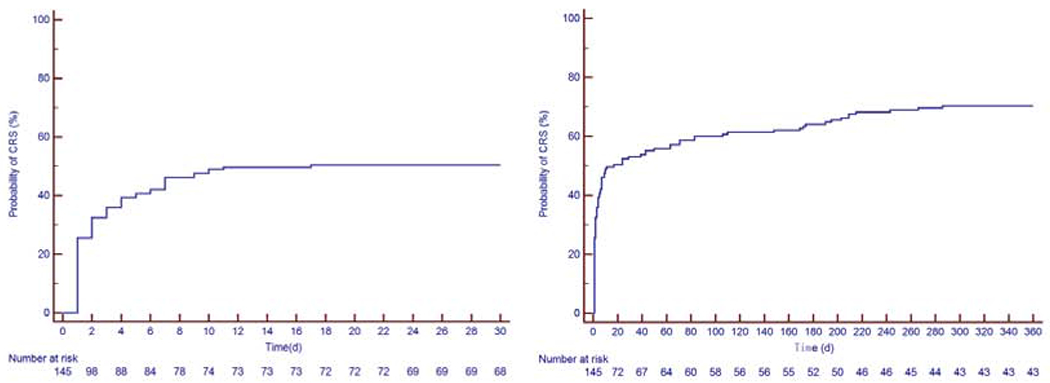

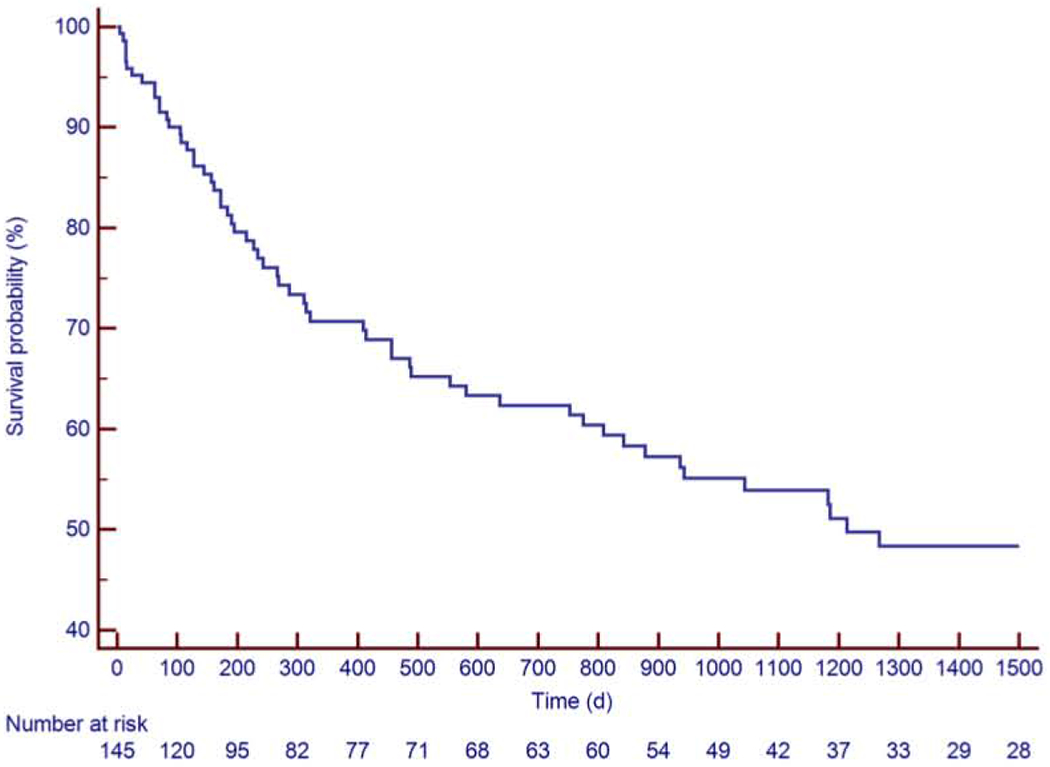

Between August 2010 and January 2019, a total of 145 patients were identified (median 60 years old, 1st-3rd quartiles 50-66 years, 74% male). Thirty-six patients (25%) were diagnosed with ALL, 43 patients with DLBCL (30%) and 66 patients (46%) with CLL. Baseline clinical characteristics, reported at the time of or most proximal to CART19 infusion, medications and laboratory results are presented in Table 1. The median follow-up period was 456 days (1st-3rd quartiles 128-1,214 days, range 5 to 3,103 days). There were 176 occurrences of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in 104 patients (72 %), with a median time to CRS of 6 days (1st-3rd quartiles 1-8 days: range 0-175 days). The Kaplan-Meier estimates for CRS rate was 53% at 30 days, 64% at 6 months and 71% at 12 months (Figure 1). Sixty-one patients died, 59 of them from non-cardiac death. The KM estimates for overall survival was 95% at 30 days, 81% at 6 months and 71% at 12 months (Figure 2). Six patients (4%) were lost to follow-up at a median time of 391 days.

Table 1:

Characteristics of 145 Patients Treated with CART Cell Therapy

| All Patients n=145 | MACE n= 31 | No MACE n= 114 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Demographics and Cardiovascular Characteristics | |||

| Median Age at Infusion (year, interquartile 1-3) | 60 (50-66) | 50 (29-61) | 61 (54-67) |

| Male Sex | 107 (74%) | 26 (84%) | 81 (71%) |

| History of Smoking (Current or Former) | 59 (41%) | 16 (52%) | 43 (38%) |

| Hypertension | 52 (36%) | 13 (42%) | 39 (34%) |

| Diabetes | 13 (9%) | 4 (13%) | 9 (8%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 44 (30%) | 13 (42%) | 31 (27%) |

| Heart Failure | 4 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (3%) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 14 (10%) | 5 (16%) | 9 (8%) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 12 (8%) | 5 (16%) | 7 (6%) |

| Baseline LVEF (%) | 61 ± 9 (n=124, 86%) | 62 ± 7 (n=28, 90%) | 61 ± 9 (n=96, 84%) |

| Type of Cancer | |||

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) | 36 (25%) | 8 (26%) | 28 (25%) |

| Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) | 66 (46%) | 18 (58%) | 48 (42%) |

| Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) | 43 (30%) | 5 (16%) | 38 (33%) |

| Baseline Treatment and Medication | |||

| Previous Anthracycline Use | 87 (60%) | 14 (45%) | 73 (64%) |

| Radiation | 33 (23%) | 4 (13%) | 29 (25%) |

| Aspirin | 9 (6%) | 4 (13%) | 5 (4%) |

| ACEi/ARB | 24 (17%) | 6 (19%) | 18 (16%) |

| Beta-Blockers | 27 (19%) | 7 (23%) | 20 (18%) |

| Statin | 31 (21%) | 12 (39%) | 19 (17%) |

| Oral Hyperglycemics | 11 (8%) | 3 (10%) | 8 (7%) |

| Insulin | 5 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (2%) |

| Baseline Blood Tests, Vital Signs and Outcomes | |||

| Hgb (g/dL) | 11.3 ± 2.2 | 10.7 ± 2.3 | 11.5 ± 2.2 |

| Median WBC (K/μL, interquartile 1-3) | 3.0 (1.2-6.3) | 2.1 (0.5 – 3.9) | 3.3 (1.6 – 6.9 |

| Platelets (K/μL) | 114 ± 66 | 94 ± 65 | 120 ± 65 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.92 ± 0.27 | 1.03 ± 0.27 | 0.89 ± 0.26 |

| Median GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2, interquartile 1-3) | 85.0 (67.6-111.7) | 112.0 (91.5 – 162.0) | 79.0 (65.5 – 95.5) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure at infusion (mmHg) | 121 ± 16 | 118 ± 15 | 121 ± 16 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure at infusion (mmHg) | 70 ± 10 | 66 ± 8 | 71 ± 10 |

| Anti-interleukin-6 Use | 36 (25%) | 15 (48%) | 21 (18%) |

| Vasopressors Use | 33 (23%) | 17 (52%) | 16 (14%) |

The “No MACE” and “All Patients” columns comprised both patients lost to follow-up or with non-cardiac death prior to MACE.

ACEi/ARB= angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin II receptor blockers, CKD= chronic kidney disease, CRS= cytokine release syndrome, GFR= glomerular filtration rate, Hgb= hemoglobin, LVEF= left ventricular ejection fraction, WBC= white blood cells

Number in each column represents number, % for categorical variables and Mean±SD or Median (Q1-Q3) for continuous variables

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Cytokine Release Syndrome.

The first image to the left is the Kaplan-Meier curve at 30 days and the figure to the right is the Kaplan-Meier curve over 360 days. The Kaplan-Meier estimate for CRS was 53% at 30 days, 64% at 6 months and 71% at 12 months.

CRS: cytokine release syndrome

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier Estimate of the Survival Rate.

The Kaplan-Meier estimates for survival were 95% at 30 days, 81% at 6 months and 71% at 12 months.

Occurrence and characteristics of MACE developed by patients treated with CART19 cell therapy

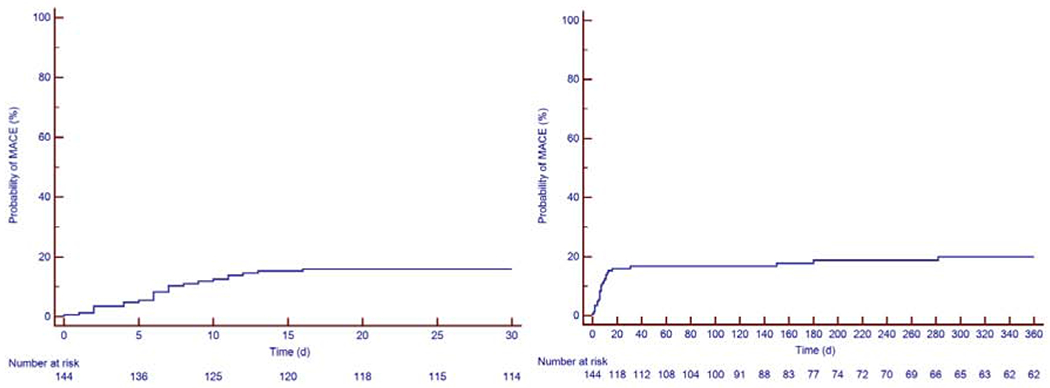

Thirty-one patients developed MACE, for a total of 41 events. All events were considered in the subsequent analyses. The median time to MACE was 11 days after CART19 infusion (1st-3rd quartiles 6-151 days: range 0-2372 days). The KM estimates for MACE was 17% at 30 days, 19% at 6 months and 21% at 12 months (Figure 3). The adjudication of all HF events is included in Supplemental Table 1. The median follow-up period of patients in the MACE group was 753 days (1st-3rd quartiles 215-1714 days: range 14-3061 days). There were 22 heart failure events (one of which was a stress-induced cardiomyopathy) in 21 patients (15%), 12 episodes of atrial fibrillation in 11 patients (7.5%), 2 events of other arrhythmias (supraventricular tachycardia, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia), 2 episodes of acute coronary syndrome and 2 cardiac deaths. The cardiac deaths were a pulseless electrical activity arrest and a massive pulmonary embolism leading to a ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Two patients had atrial fibrillation concurrent with the use of ibrutinib and thus, were not included in MACE. The cumulative incidence of MACE and non-cardiac death in all patients is shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Major Cardiovascular Events (MACE).

The first image to the left is the Kaplan-Meier curve at 30 days and the figure to the right is the KM curve over 360 days. The Kaplan-Meier estimates for MACE were 17% at 30 days, 19% at 6 months and 21% at 12 months.

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events

Echocardiographic characteristics of patients treated with CART19 cell therapy

Baseline echocardiographic findings are listed in Table 2. The LVEF obtained both from echocardiogram and MUGA was available for 124 patients (86%) and was 61 ± 9%. Prior to CART19 cell infusion, 110 patients had an echocardiogram (78 of which had a full report available and could be used for further analysis). The median time of echocardiogram to CART19 cell infusion was 43 days (1st-3rd quartiles 21-80 days: range 2-615 days) and was not associated with MACE. The baseline LVEF in patients who developed MACE was 62 ± 7% (echocardiogram obtained in 28 patients) and 61 ± 9% in patients who did not. Seventeen patients (55% of the patients with MACE) had another echocardiogram performed when MACE occurred. The LVEF measured at the time of MACE was 49 ± 14 %.

Table 2:

Echocardiographic Parameters at Baseline

| All Patients n= 78 | MACE n= 16 | No MACE n= 62 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 75 ± 17 | 72 ± 8 | 75 ± 17 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 4.65 ± 0.53 | 4.72 ± 0.17 | 4.62 ± 0.52 |

| LVESD (cm) | 3.15 ± 0.52 | 3.20 ± 0.32 | 3.14 ± 0.52 |

| IVS (cm) | 0.93 ± 0.18 | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.18 |

| PWT (cm) | 0.93 ± 0.14 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.14 |

| RV Base (cm) | 3.45 ± 0.53 | 3.45 ± 0.52 | 3.46 ± 0.54 |

| TAPSE (cm) | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| RV S’ (mm/s) | 13.2 ± 3.1 | 13.5 ± 2.5 | 13.2 ± 2.7 |

| MV E (interquartile 1-3) | 67.8 (59.8-81.0) | 71.8 (63.2 – 83.1) | 67.6 (59.4 – 80.7) |

| MV a (interquartile 1-3) | 61.0 (52.9-82.9) | 56.4 (46.5 – 67.2) | 64.2 (54.8 – 87.4) |

| Mitral E/a | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| Mitral E/e’ | 8.7 ± 3.5 | 10.0 ± 0.1 | 8.3 ± 3.3 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 27 ± 6 | 30 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 |

| LAVI (cm/m2) | 29.7 ± 11.0 | 35.1 ± 11.7 | 28.0 ± 10.1 |

| LVEF Simpson’s Method (%) | 62.1 ± 7.2 | 61.8 ± 7.5 | 62.3 ± 6.5 |

The “No MACE” and “All Patients” columns comprised both patients lost to follow-up or with non-cardiac death prior to MACE.

bpm= beat per minute, IVS= Interventricular septum thickness, LAVI= Left atrial volume indexed, LVEDD= Left ventricle end-diastolic diameter, LVEF= Left ventricular ejection fraction, LVESD= Left ventricle end-systolic diameter, MV = mitral valve; PASP= Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, PWT= Posterior wall thickness, TAPSE= tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

Number in each column Mean±SD or Median (Interquartile 1-3) for continuous variables

Clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic parameters associated with MACE

The differences between patients with and without MACE are presented in Table 1 (and Supplemental Table 2), and the univariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression model in Table 3 (additional Fine and Gray analysis in Supplemental Table 4). The variables associated with MACE were prior atrial fibrillation (HR 2.83, 95% CI 1.08-7.43, p=0.035), aspirin use (HR 3.13, 95% CI 1.09-8.99, p=0.034), statin use (HR 2.29, 95% CI1.11-4.73, p=0.025), insulin use (HR 5.70, 95% CI 1.70-19.08, p=0.005), baseline creatinine (HR of 4.30 for each 1 mg/dL increase, 95% CI 1.19-15.59, p=0.026), overall CRS grading (HR 2.10, 95% CI 1.47-2.98, p<0.001), CRS Grade 2 (HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17-0.91, p=0.029), CRS Grade 3 (HR 3.31, 95% CI 1.55-7.09, p=0.002), CRS Grade 4 (HR 9.79, 95% CI 3.96-24.21, p<0.001), diastolic blood pressure (HR of 0.95 for each 1mm Hg increase, 95% CI 0.91-0.99, p=0.007), hemoglobin (HR of 0.83 for each 1 g/dL increase, 95% CI 0.69-0.99, p=0.035) and platelets (HR of 0.99 for each 1 K/μL increase, 95% CI 0.99-1.00, p=0.027). There was a trend in the association of MACE with higher E/e’ ratio (HR 1.15 for each 1-unit increase, 95% CI 1.00-1.31, p=0.046) and larger indexed left atrial volume (HR 1.04 for each 1 ml/m2 increase, 95% CI 1.00-1.08, p=0.075). Analyses of diastolic function using the 2016 guidelines (14) indicated that thirty-one patients had normal diastolic function (40%), 22 patients grade I diastolic dysfunction (28%), 1 patient had grade II dysfunction (1%), 3 patients grade III dysfunction (4%), and 21 patients had indeterminate diastolic function (27%). There was no association between the presence of diastolic dysfunction and MACE (p=0.866).

Table 3:

Univariable Cox Proportional Cause-Specific Hazards Regression

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | 0.431 |

| Sex (male) | 1.73 (0.66-4.51) | 0.265 |

| Hypertension | 1.40 (0.68-2.89) | 0.362 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.70 (0.59-4.86) | 0.326 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.58 (0.77-3.25) | 0.212 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.17 (0.16-8.60) | 0.879 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 2.07 (0.79-5.42) | 0.139 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 2.83 (1.08-7.43) | 0.035 |

| Stroke | 2.33 (0.55-9.84) | 0.250 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 2.08 (0.63-6.88) | 0.228 |

| Smoking | 1.35 (0.92-1.97) | 0.122 |

| Radiation | 0.66 (0.23-1.90) | 0.441 |

| Cancer Subtypes | 0.75 (0.44-1.27) | 0.278 |

| Transplantation | 0.92 (0.35-2.43) | 0.872 |

| Aspirin | 3.13 (1.09-8.99) | 0.034 |

| ACEi/ARB | 1.23 (0.50-3.01) | 0.648 |

| Beta-Blocker | 1.35 (0.58-3.15) | 0.488 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 0.86 (0.26-2.84) | 0.806 |

| Statin | 2.29 (1.11-4.73) | 0.025 |

| Diuretics | 0.97 (0.23-4.06) | 0.964 |

| Oral Anticoagulation | 0.88 (0.12-6.45) | 0.898 |

| Insulin | 5.70 (1.70-19.08) | 0.005 |

| Ferritin | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.634 |

| CRS Grading | 2.10 (1.47-2.98) | <0.001 |

| CRS Grade 1 | 0.25 (0.03-1.86) | 0.176 |

| CRS Grade 2 | 0.39 (0.17-0.91) | 0.029 |

| CRS Grade 3 | 3.31 (1.55-7.09) | 0.002 |

| CRS Grade 4 | 9.79 (3.96-24.21) | <0.001 |

| LVEF | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | 0.778 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | 0.346 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.007 |

| Heart Rate | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.868 |

| Hgb | 0.83 (0.69-0.99) | 0.035 |

| WBC | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.619 |

| Platelets | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.027 |

| Creatinine | 4.30 (1.19-15.59) | 0.026 |

| GFR | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.181 |

| Mitral E/e’ | 1.15 (1.00-1.31) | 0.046 |

| PASP | 1.05 (0.93-1.18) | 0.150 |

| Diastolic Dysfunction | 1.11 (0.32-3.85) | 0.866 |

| Left Atrial Volume Indexed | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 0.075 |

| Interventricular Septal Thickness | 3.13 (0.19-50.91) | 0.422 |

ACEi/ARB= angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin II receptor blockers, CI= confidence interval, CRS= cytokine release syndrome, GFR= glomerular filtration rate, Hgb= hemoglobin, IV=intravenous, LVEF= left ventricular ejection fraction, PASP= Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, WBC= white blood cells

Baseline creatinine, statin treatment and CRS grading were chosen for the multivariable competing risk analysis according to their clinical relevance, effect size in univariable models, and limited to these variables in order to avoid multicollinearity. The multivariable competing risk regression analysis revealed that baseline creatinine (HR 15.54 for each 1 mg/dL increase, 95% CI 3.67-65.86, p<0.001), and Grade 3 CRS (HR 8.42, 95% CI 3.48-20.40, p<0.001) or Grade 4 CRS (HR 29.86, 95% CI 9.80-90.94, p<0.001) were independently associated with MACE (Table 4). These results were confirmed with the stepwise regression using the backwards elimination method and by individually adding variables into the final model. The same results were found with the Fine and Gray method (Supplemental Table 5). Statin use at baseline was not independently associated with MACE.

Table 4:

Association with MACE determined using Multivariable Cox Proportional Cause-Specific Hazards Regression Analyses

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Statin | 1.83 (0.88-3.81) | 0.105 |

| Creatinine | 15.54 (3.67-65.86) | <0.001 |

| CRS Grade 1 | 0.49 (0.06-3.74) | 0.489 |

| CRS Grade 2 | 0.95 (0.33-2.71) | 0.917 |

| CRS Grade 3 | 8.42 (3.48-20.40) | <0.001 |

| CRS Grade 4 | 29.86 (9.80-90.94) | <0.001 |

CI= confidence interval, CRS= cytokine release syndrome

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that adult patients with CD19+ malignancy treated with CART19 cells are at risk of MACE, mainly symptomatic heart failure, most of which occur within weeks of the infusion (Central Illustration). The variables independently associated with MACE in our study included baseline creatinine and Grade 3 and 4 cytokine release syndrome.

Central illustration: Timeline Demonstrating the Relationship Between CART Cells Infusion, CRS, MACE and Follow-up.

As the median time to MACE was 5 days later than the median time to CRS onset, this suggests that CRS and its treatments can at least contribute to the occurrence of MACE in patients treated with CART19 cell therapy.

CART: chimeric antigen receptor T cell, CRS: cytokine release syndrome, MACE: major cardiovascular events

Between August 2010 and January 2019, a total of 145 patients were identified. The median age (60 years old), male distribution (74%) and distribution of malignancies (25% ALL, 30% DLBC and 46% CLL) are representative of the current population receiving CART19 cell therapy (15,16). The KM estimates for overall survival were 95% at 30 days, 81% at 6 months and 71% at 12 months (Figure 2). The mortality in our cohort is less than previously described likely due to the improving expertise and the expanding applications to patients with less severe conditions and to patients who have received a less intensive chemotherapy regimen (4,15,17).

In a recent publication from our group in 450 patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or ALL, only 3% of patients with ALL suffered from heart failure (18). Another study investigating patients with hematologic cancers treated with anthracyclines reported that 4% of lymphoma patients developed symptomatic heart failure at a median time of 523 days after the initiation of anthracycline therapy (19). Our study, with a prevalence of 15% for symptomatic heart failure at a median time of 11 days, suggests a higher heart failure incidence than previously described, underlining the effect of CART cell treatment.

The cardiovascular profile of the patients treated with CART19 cells was slightly worse compared to that noted in the general population, with respect to the rates of heart failure, hypertension and coronary artery disease (20–23). According to age, <2% of persons aged 40-59 years in the general population are reported to have HF, compared to 3% in our study. The prevalence of coronary disease for those 40-59 years of age in the general population is about 6% which is lower than in our study (10%)(22). The prevalence of hypertension is estimated at 32% in the general population, compared to 36% in our study (20,24). The prevalence of diagnosed diabetes mellitus is approximately 10%, slightly higher than in our study (9%)(21). The current or previous smoking rate may appear elevated (41%) in our study. However, when taking into account current smokers only (12/145 patients, 8%), the prevalence of current smoking was less than the current American smokers (14%) (25). The difference in proportion of previous heart failure or coronary disease could be attributed to prior cancer therapy (e.g. 60% anthracycline use, 23% radiation, 21% stem cell transplant). Similarly, atrial fibrillation (8%) was more prevalent in our study than in the general population (<2% under age 65 years) and may be explained by the use of ibrutinib (for CLL, diagnosed in 46% of our patients).

Cancer subtype does not seem to influence the risk of MACE (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.44-1.28, p=0.278) despite the different cardiovascular profiles of patients. Patients with CLL and DLBCL were older than patients with ALL and had increased cardiovascular risk, however, their previous and current treatment may be less aggressive than that of ALL, possibly. Kaplan-Meier estimates for each cancer subtype and MACE, CRS and survival were also performed at 30 days, 6 months and 12 months (see Supplemental Figures 2–4).

In our study, 104 patients (72%) had at least one CRS episode which was higher than the previously documented rate (55.3%) in a recent large systematic review and meta-analysis (6). We used the most current and broadest CRS consensus definition in order to identify the episodes (12), which may explain the increased detection of CRS.

The use of statin, insulin, aspirin, and higher baseline creatinine levels were each associated with MACE and likely reflect patients with a high cardiovascular risk profile and comorbidities pre-treatment. The analysis of baseline echocardiographic characteristics revealed that there was also a trend for diastolic dysfunction and high left ventricular filling pressures and MACE. However, diastolic function categories as defined using the 2016 guidelines (14) was not associated with MACE; this result could be explained by the paucity of moderate or severe diastolic dysfunction, and the relatively high frequency of indeterminate diastolic function.

Interestingly, baseline LVEF was not associated with MACE, underlining the importance of analyzing baseline diastolic function indices (E/e’, left atrial volumes) in these patients. Although prior atrial fibrillation and the use of aspirin and insulin were associated with MACE, they were not included in further analysis as the proportion of patients treated with aspirin and insulin or with previous atrial fibrillation was low.

The occurrence of Grade 3 and 4 CRS was strongly associated with MACE. It is possible that CRS may result in depressed myocardial function explaining the high rates of heart failure. It is also possible that patients with CRS receive large quantities of intravenous fluids that can worsen the volume overload state. The exact CRS treatment was left to the discretion of the treating physicians but usually comprises intensive fluid resuscitation followed by vasopressors. The median time to MACE was 5 days later than the median time to CRS onset, suggesting that CRS and its treatments may contribute to MACE in patients treated with CART19 cell therapy.

Limitations

The data were obtained retrospectively. As with all retrospective studies, MACE could have been misclassified due to reporting errors or loss to follow-up. However, each medical chart was carefully reviewed, and signs and symptoms of MACE were individually adjudicated. Also, our overall lost to follow-up was small (6 patients (4%)). In order to decrease the loss of follow-up, every patient was researched using a national necrology database. Thus, it is unlikely that deaths were missed. Confidence intervals for many of our risk estimates were also wide, and as such, these results need to be confirmed in additional studies.

As patients were referred from around the world to receive CART19 cell therapy, prior anthracycline use could have been underreported, and it was not possible to determine the total radiation or anthracycline dose previously received. It is widely acknowledged that total radiation or anthracycline dose is directly associated with MACE; the association of anthracycline dose or radiation with MACE could have been underestimated.

Clinical relevance

As CART19 cell therapy use becomes more available and accessible, it is crucial to understand not only the benefits but the possible side effects and time frame in which they can occur. In contrast to radiation or other potentially cardiotoxic chemotherapies, no guidelines are currently available for screening or surveillance of cardiac function of patients treated with CART19 cells. Understanding the incidence and the natural history of treatment-induced side effects will allow for better screening and follow-up for these patients. To this effect, an extensive monitoring program in the United Kingdom is underway (26).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study conducted in adult patients treated with CART19 cells evaluating the occurrence of and risk factors associated with adverse cardiovascular events. Using multivariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazards regression analysis, we determined that baseline creatinine and Grade 3 or 4 CRS were independently associated with MACE. CART cells have opened a new field in the treatment of hematologic malignancies and are now under investigation for other indications including solid tumors, AML and multiple myeloma (27–29). Given that CART19 cell use will only increase in the future and that no recommendations for monitoring and follow-up of left ventricular function and MACE currently exist (30), prospective studies are needed to ascertain the incidence and predictors of MACE.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives:

Competencies in Medical Knowledge and Patient Care:

Patients undergoing cancer treatment with CART cells are at risk of MACE, mainly symptomatic heart failure. Patients at increased risk for MACE may benefit from cardiovascular monitoring.

Translational Outlook:

The use of CART19 cell therapy will increase in the future. Currently, no recommendations for cardiovascular monitoring and follow-up exist. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the incidence and identify the predictors of MACE in CART cell treated patients. This is important to inform the follow-up and management of these patients.

Funding Sources/Acknowledgement:

The study was funded through NHLBI 1R01HL130539-01 (to MSC). We thank Jesse Chittams MS, and Ronald Kamusiime MS, for assistance with statistical analysis.

Abbreviations List:

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CART

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell

- CART19

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell against CD19 antigen

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- CRS

cytokine release syndrome

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- DLBCL

diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- MACE

major cardiovascular events

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest : The authors declare no conflicts of interest and have no industry relations to disclose.

The study was partially presented as an oral presentation at the American Heart Association Scientific Meeting, Nov 2019, Philadelphia

References

- 1.Burstein DS, Maude S, Grupp S, Griffis H, Rossano J, Lin K. Cardiac Profile of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy in Children: A Single-Institution Experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018. August 1;24(8):1590–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Gödel P, Subklewe M, Stemmler HJ, Schlößer HA, Schlaak M, et al. Cytokine release syndrome. J Immunother Cancer. 2018. June 15;6(1): 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim WA, June CH. The Principles of Engineering Immune Cells to Treat Cancer. Cell. 2017. 09;168(4):724–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter DL, Hwang W-T, Frey NV, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, Loren AW, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2015. September 2;7(303):303ra139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019. 03;380(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grigor EJM, Fergusson D, Kekre N, Montroy J, Atkins H, Seftel MD, et al. Risks and Benefits of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell (CAR-T) Therapy in Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transfus Med Rev. 2019. April;33(2):98–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leick MB, Maus MV. Toxicities associated with immunotherapies for hematologic malignancies. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2018;31(2):158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assuncao BMBL, Handschumacher MD, Brunner AM, Yucel E, Bartko PE, Cheng K-H, et al. Acute Leukemia is Associated with Cardiac Alterations before Chemotherapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr Off Publ Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017. November;30(11):1111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald JC, Weiss SL, Maude SL, Barrett DM, Lacey SF, Melenhorst JJ, et al. Cytokine Release Syndrome After Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Crit Care Med. 2017. February;45(2):e124–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvi RM, Frigault MJ, Fradley MG, Jain MD, Mahmood SS, Awadalla M, et al. Cardiovascular Events Among Adults Treated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cells (CAR-T). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. December 16;74(25):3099–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular Endpoint Events in Clinical Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015. July;66(4):403–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Turtle CJ, Brudno JN, et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019. April 1;25(4):625–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015. January;28(1):1–39. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016. April;29(4):277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, Nasta SD, Mato AR, Anak Ö, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Refractory B-Cell Lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2017. December 28;377(26):2545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014. October 16;371(16):1507–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017. December 28;377(26):2531–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang Y, Assuncao BL, Denduluri S, McCurdy S, Luger S, Lefebvre B, et al. Symptomatic Heart Failure in Acute Leukemia Patients Treated With Anthracyclines. JACC CardioOncology. 2019. December 17;1(2):208–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali MT, Yucel E, Bouras S, Wang L, Fei H-W, Halpern EF, et al. Myocardial Strain Is Associated with Adverse Clinical Cardiac Events in Patients Treated with Anthracyclines. J Am Soc Echocardiogr Off Publ Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(6):522–527. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hypertension Prevalence and Control Among Adults: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief No 289, oct 2017 [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db289.htm [PubMed]

- 21.National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. 2020;32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020. March 3;141(9):e139–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prevalence of Coronary Heart Disease --- United States, 2006--2010 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6040a1.htm

- 24.Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt VL. Hypertension Among Adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. 12 p. [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDC. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm

- 26.Ghosh AK, Chen DH, Guha A, Mackenzie S, Walker JM, Roddie C. CAR T Cell Therapy–Related Cardiovascular Outcomes and Management. JACC CardioOncology. 2020. March;2(1):97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh A, Mailankody S, Giralt SA, Landgren CO, Smith EL, Brentjens RJ. CAR T cell therapy for multiple myeloma: where are we now and where are we headed? Leuk Lymphoma. 2018. September 2;59(9):2056–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yong CSM, Dardalhon V, Devaud C, Taylor N, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. CAR T-cell therapy of solid tumors. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017. April;95(4):356–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotiroti MC, Arcangeli S, Casucci M, Perriello V, Bondanza A, Biondi A, et al. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Targeting by Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells: Bridging the Gap from Preclinical Modeling to Human Studies. Hum Gene Ther. 2017. March;28(3):231–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, Ewer MS, Ky B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, et al. Expert Consensus for Multimodality Imaging Evaluation of Adult Patients during and after Cancer Therapy: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014. September;27(9):911–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.