Abstract

The global pandemic of SARS-CoV-2, the cause of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been associated with worse outcomes in several patient populations, including the elderly and those with chronic comorbidities. Data from previous pandemics and seasonal influenza suggest that pregnant women may be at increased risk for infection-associated morbidity and mortality. Physiological changes in normal pregnancy and metabolic and vascular changes of high-risk pregnancies may affect pathogenesis or exacerbate the clinical presentation of COVID-19. Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 enters the cell via the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is upregulated in normal pregnancy. Upregulation of ACE2 mediates conversion of Angiotensin II (vasoconstrictor) to Angiotensin 1–7 (vasodilator) and contributes to relatively low blood pressures, despite upregulation of other components of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system. As a result of higher ACE2 expression, pregnant women may be at an elevated risk of complications from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Upon binding to ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 causes its downregulation, thus lowering Angiotensin 1–7 levels, which can mimic/worsen vasoconstriction, inflammation, and pro-coagulopathic effects that occur in preeclampsia. Indeed, early reports suggest that, among other adverse outcomes, preeclampsia may be more common in pregnant women with COVID-19. Medical therapy, during both pregnancy and breast feeding, relies on medications with proven safety, but safety data are often missing for medications in the early stages of clinical trials. We summarize guidelines for medical/obstetric care and outline future directions for optimization of treatment and preventive strategies for pregnant patients with COVID-19 with the understanding that relevant data are limited and rapidly changing.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, ACE2, pregnancy, preeclampsia

INTRODUCTION

Coronaviruses are a family of enveloped, single-stranded, positive-strand RNA viruses characterized by spherical morphology with surface spike projections. Human coronaviruses are divided into α- and β-coronaviruses. The rapid emergence and human-to-human transmission of a virulent novel lineage b β-coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, has resulted in the global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.1, 2 World-wide population studies to date have identified several patient characteristics, including age and comorbid conditions, as risk factors for poor outcomes, but data on pregnant patients are limited. Based on data from prior pandemics, pregnant women3 are at higher risk of acquiring infection and dying compared to non-pregnant women. The current review will provide a multidisciplinary summary of the management of COVID-19 during pregnancy using an evidence base that has been published since identification of the first patients in Wuhan City, China, in December 2019.

TAXONOMY AND PHYLOGENY OF SELECT HUMAN CORONAVIRUSES

Virion and Viral Life Cycle

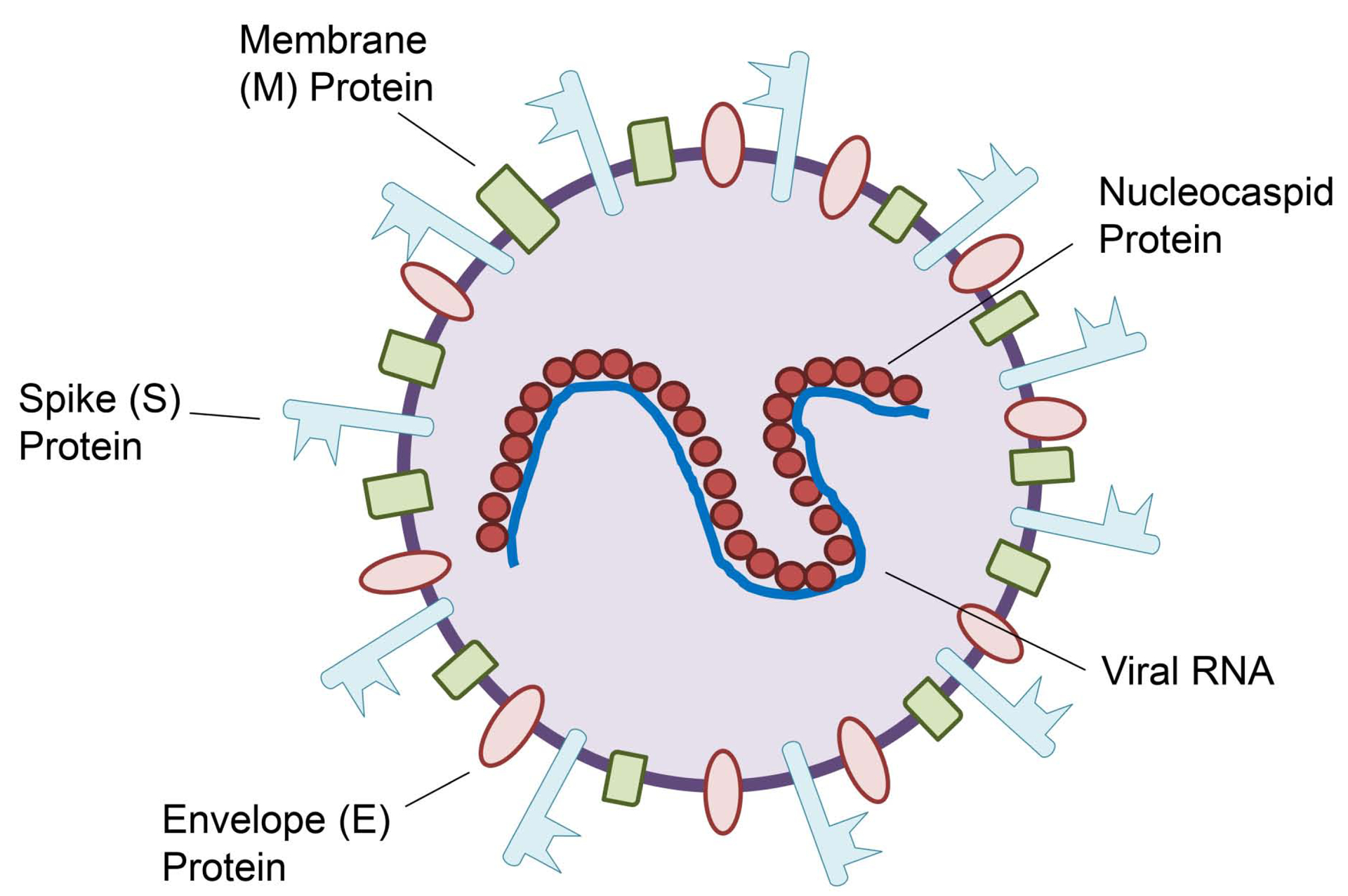

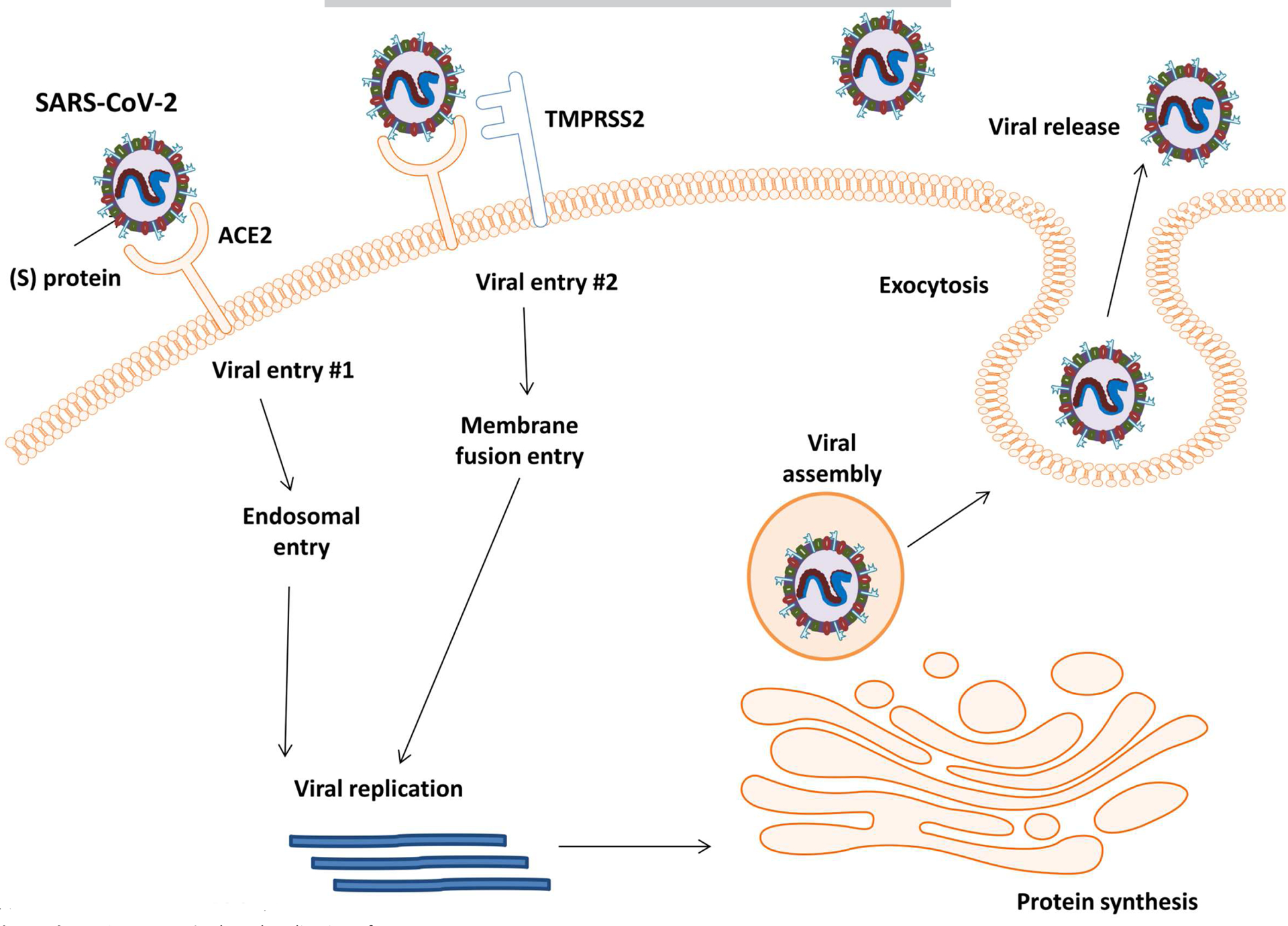

The capsid of SARS-CoV-2 contains a RNA genome complexed with a nucleocapsid protein. The membrane surrounding this nucleocapsid contains 3 proteins common to all coronaviruses, spike protein, membrane protein M, and small membrane protein E [Figure 1a and reference 4].4 Viral entry occurs via 2 routes. The first occurs when the spike protein attaches to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, releasing the viral genome and nucleocapsid protein into the host cell cytoplasm.5 The other pathway is the direct plasma membrane route via transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), which allows for the proteolytic cleavage of the spike protein and mediation of fusion with the cell membrane.6 Intracellularly, the viral genome is translated into a replicase to produce more genome RNA, mRNA and viral protein. Viral membrane proteins, M, N & E assemble on intracellular membranes. The nucleocapsid protein and viral RNA complex form a helical capsid structure, which buds between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Mature viral particles are packaged in vesicles, transported to the cell membrane, and released from the cell [Reference 5 and Figure 1b].5

Figure 1a: Features and lifecycle of SARS-CoV-2.

Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 viron

Figure 1b: Features and lifecycle of SARS-CoV-2.

Viral entry methods and replication of SARS-CoV-2

Viral Tropism, normal and high-risk pregnancies

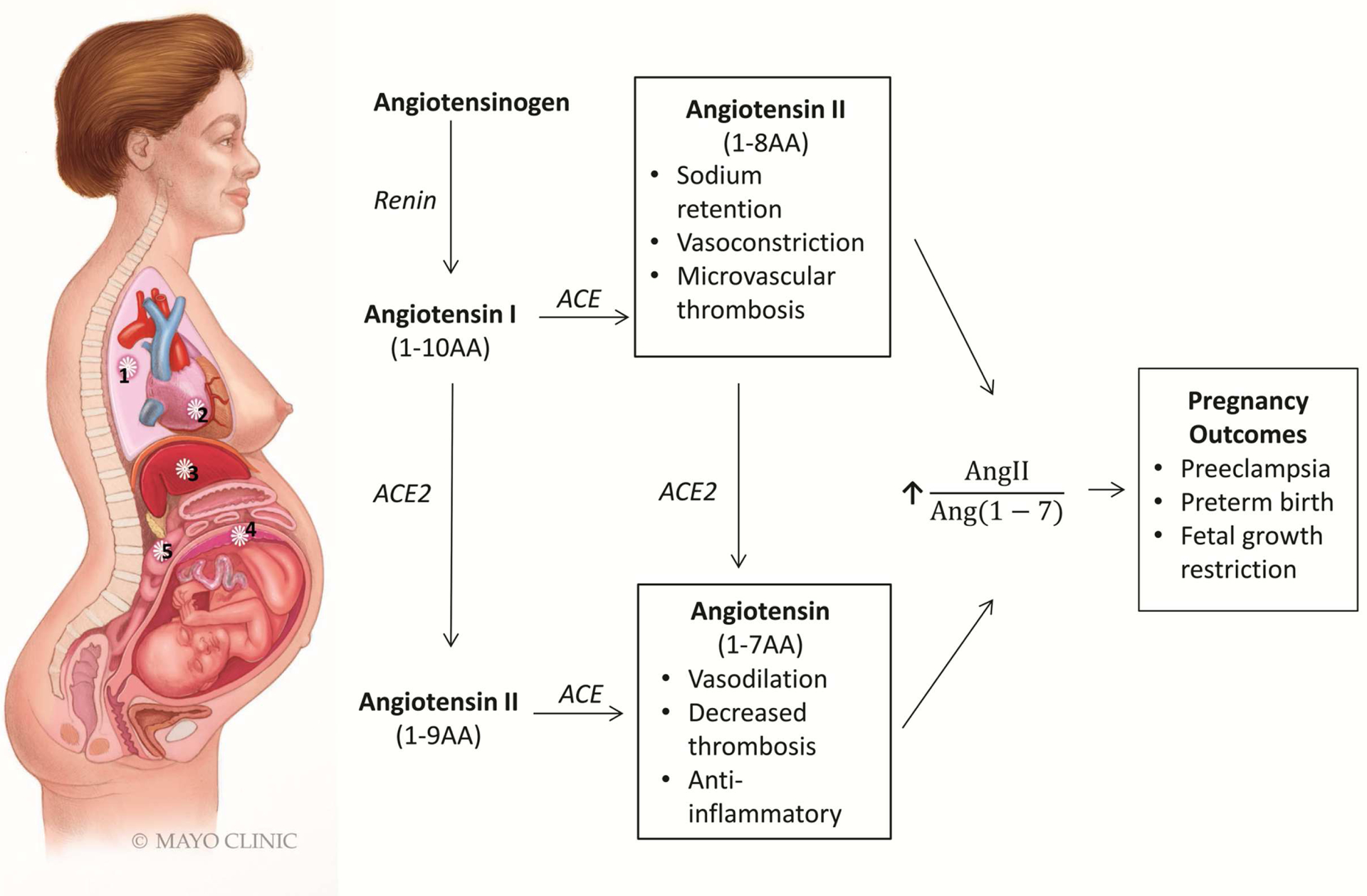

The ACE 2 enzyme plays a key role in in the conversion of Angiotensin I (Ang I) to Ang 1–9 and Ang II to Ang 1–7 (vasodilatory, anti-thrombotic, and anti-inflammatory activities) (Figure 2). The hormonal profile of normal gestation is characterized by an early increase of all of the components of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS), including ACE 2.7 This raises the possibility that pregnant women may be at a greater risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, low blood pressure in pregnant women is maintained through a balance between being refractory to the pressor effects of Angiotensin II (Ang II) and increased levels of Ang-(1–7), which exhibit systemic vasodilatory responses.8, 9 In preeclampsia, a pregnancy specific hypertensive disorder that affects 3.5% of all pregnancies10 and clinically is characterized by multisystem involvement and, commonly, proteinuria, this balance is lost, with an over-exaggerated Ang II blood pressure response.11 Preeclampsia has also been associated with decreased maternal plasma Ang-(1–7) levels.9 As SARS-CoV-2 not only binds to ACE2, but also causes its downregulation,12 infections during pregnancy may potentiate RAAS abnormalities i.e., increased Ang II relative to decreased Ang-(1–7), that are present in preeclampsia. COVID-19 and preeclampsia share additional common mechanisms, including endothelial cell dysfunction, and coagulation abnormalities. Notably, ACE2 receptors are also expressed by endothelial cells13 and endothelial cell infection and immune cell-mediated endothelial injury has been recently described in COVID-19.14 As the hallmark of preeclampsia is endothelial dysfunction,15 infection with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy could mimic and/or initiate microvascular dysfunction by causing endotheliitis. Systemic inflammation and microcirculatory dysfunction, characterized by vasoconstriction and resultant ischemia, ensue. This can further contribute to a pro-coagulopathic state, as demonstrated by high rates of deep vein thrombosis, stroke and pulmonary embolism, which are increasingly reported in COVID-19 patients.16, 17,18 Infection with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy can be particularly pro-thrombotic, as coagulation abnormalities may potentiate a hypercoagulable state, which is already present in non-complicated pregnancy, and exacerbated by preeclampsia.19 Similarly, complement activation, which is present both in preeclampsia20 and COVID-1921, may result in particularly severe thrombotic vascular injury when these two disease states are present concurrently. In summary, RAAS abnormalities, endothelial dysfunction, complement activation, and the pro-coagulopathic effects of COVID-19 are similar to those occurring in preeclamptic pregnancies, potentially resulting in progressive vascular damage. Therefore, pregnancy and its complications represent a vulnerable state for invasive infection with SARS-CoV-2 reflecting several overlapping cellular mechanisms.

Figure 2: Pregnancy, COVID-19, and mechanisms of vascular damage.

Upregulation of ACE2 receptor in pregnancy may increase the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Binding of virus to to ACE2 causes its downregulation and may increase Ang II relative to Ang-(1–7), thus favoring vasoconstriction, which can mimic/worsen vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia

1- Lungs, 2- Heart, 3- Kidneys, 4- Placenta and endothelial cells , 5- Intestine

In addition to the direct cytotoxic effect of the virus, tissue injury in COVID-19 is mediated through an excessive inflammatory response, commonly referred to as cytokine storm. Cytokine storm is mediated via immune responses, which are significantly modified in pregnancy, and may contribute to COVID-19 laboratory and clinical characteristics during pregnancy.

IMMUNE RESPONSES TO COVID −19

During pregnancy, the maternal immune system must adjust to tolerate the semi-allogeneic fetus while maintaining its ability to respond to pathogenic insult.22, 23 This is also known as T helper (Th) 2 polarization. However, near the end of pregnancy a switch to Th1 immunity occurs and the maternal immune system becomes pro-inflammatory, leading to the sequence of events that occur prior to parturition (i.e. cervical dilation, contractions). Data on immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women are lacking at this time, while data from prior pandemics suggest that pregnancy may increase the risk of acquiring infection and dying compared to non-pregnant women.3 The timing of infection during gestation may induce differences in maternal immune responses, viral clearance and ultimately perinatal outcomes. As the first and third trimesters are pro-inflammatory to promote implantation and labor,24 pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 during these trimesters may be at higher risk of exaggerated responses to virus (cytokine storm). Furthermore, high levels of stress and inflammation occur during labor, and the physiologic changes that occur in a mother’s body after the baby is born could lead to poor maternal SARS-CoV-2 outcomes postpartum. This has been observed clinically, where pregnant women with mild symptoms upon admission to the hospital for delivery required postpartum hospital admission for respiratory symptoms.25, 26

Conflicting data exist regarding vertical transmission of the virus; however, research on other coronavirus infections during pregnancy suggests that in utero transmission does not occur. However, mouse models and epidemiologic data have shown that inflammatory immune responses generated by viral infection during pregnancy can result in negative effects on fetal brain development.27–29 During the H1N1 pandemic, infected women had higher rates of preterm birth.30 Therefore, while placental transmission of the virus may not occur with SARS-CoV-2 infection, other short and long term effects from inflammation may adversely impact the developing fetus. These require further characterization. Maternal immunity may be passed on to protect the fetus, conferring passive immunity. IgG specific to the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak strain was found not only in maternal blood, but also in amniotic fluid and cord blood.31 Another possible source of antibodies could be breast milk, but this has yet to be determined.

MATERNAL PHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF COVID-19 DURING PREGNANCY

Significant physiological changes to respiration occur during pregnancy32 including increased secretions and congestion in the upper airways, increased chest wall circumference and upward displacement of the diaphragm. These changes result in decreased residual volume (RV) and increased tidal volume (TV) and air trapping, slightly decreased airway resistance, stable diffusion capacity, increased minute ventilation, and increased chemosensitivity to carbon dioxide. Hemodynamic changes include increased plasma volume of 20–50%, increased cardiac output and decreased vascular resistance.32 These changes result in a state of physiological dyspnea and respiratory alkalosis as well as an increased susceptibility to respiratory pathogens. As has been seen with other viral respiratory infections, the early symptoms of COVID-19 infection may mimic physiological dyspnea in pregnancy, which could result in delayed diagnosis and more severe disease.33

Pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection may experience more severe symptoms compared to non-pregnant women. Existing limited data have reported on rapid deterioration in women who had no symptoms upon arrival and were subsequently diagnosed with severe COVID-19.25 In some, but not all cases, maternal comorbidities were present (hypertension, diabetes, cholestasis of pregnancy).25, 34 Case reports have also described cases of quickly worsening maternal status with the ultimate diagnosis of cardiomyopathy.35 Unfortunately, these rapidly progressive maternal complications have led to a high rate of cesarean deliveries (CD) for either worsening maternal status or non-reassuring fetal status secondary to the worsening maternal clinical state.

Preeclampsia is an example of a common pregnancy-related complication that may be exacerbated by, or may exacerbate, COVID-19, as discussed above. The picture becomes further complicated because the two processes share common laboratory abnormalities. Thus, it may be difficult to discern whether certain abnormal laboratory findings are due to SARS-CoV-2 infection or preeclampsia, and this interplay may have treatment implications. For example, thrombocytopenia36 and liver function abnormalities,37 both of which are diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia with severe features, are also associated with worsening COVID-19 disease.

MATERNAL DISEASE AND OUTCOMES

Physiological changes in normal pregnancy and metabolic and vascular changes in high-risk pregnancies may affect the pathogenesis or exacerbate the clinical presentation of COVID-19 disease during pregnancy. A systematic review by Di Mascio et al38 evaluating and comparing obstetric outcomes in combined coronavirus infections (SARS, MERS and SARS-CoV-2) found SARS-CoV-2 alone resulted in higher rates of preterm birth (24.3%, 95% CI 12.5–38.6 for <37 weeks gestation; and 21.8%, 95% CI 12.5 −32.9 for <34 weeks gestation), preeclampsia (16.2%, 95% CI 4.2–34.1) and CD (83.9%, 95% CI 73.8–91.9).

As of April 22, 2020, a total of 23 studies26, 35, 39–59 (excluding overlapping of case reports) addressing obstetrical and neonatal outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy have been published. These studies span the time period from January 1, 2020 to April 22, 2020, and include 185 patients. The abstracted information is presented in Table 1, which summarizes maternal and neonatal outcomes. Briefly, most of the diagnoses occurred in the third trimester. Fever was the most common presenting symptom, followed by cough, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal alterations. Slightly > 25% of patients were asymptomatic at diagnosis. The most common laboratory findings were lymphopenia and neutrophilia. Pneumonia was a common diagnosis (40%) and a small percentage (3.24%) required ICU admission.

Table 1-.

Summary of maternal and neonatal outcomes during COVID-19 pandemic*

| Maternal Characteristics | Cases N (%); Total N = 185 (100%) |

|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 29.6 (range 20 to 41) |

| Trimester | |

| - First Trimester | 3/185 (1.62) |

| - Second Trimester | 5/185 (2.70) |

| - Third Trimester | 177/185 (95.68) |

| Signs and symptoms | |

| - Fever | 90/169 (53.20) |

| - Pneumonia | 75/184 (40.76) |

| - Cough | 56/169 (33.13) |

| - Asymptomatic | 44/169 (26.04) |

| - Dyspnea/Shortness of breath | 22/169 (13.01) |

| - GI alterations | 9/169 (5.32) |

| - ICU admission | 6/185 (3.24) |

| Diagnostic method | |

| - RT-PCR SARS-CoV 2 only | 179/185 (96.76) |

| - CT scan changes only | 6/185 (3.24) |

| - RT-PCR SARS- CoV 2 and CT changes | 100/185 (54.05) |

| Laboratory alterations | |

| - Lymphopenia (N=32 out of 93 reported) | 32/93 (34.40) |

| - Neutrophilia (N= 8 out of 93 reported) | 8/93 (8.6) |

| Interventions | |

| - Antibiotics | 64/145 (44.13) |

| - Supportive measures | 41/145 (28.20) |

| - Antiviral therapy | 39/145 (26.90) |

| - Corticosteroids | 12/145 (8.28) |

| Obstetric comorbidities** | |

| - Gestational Hypertension | 6/182 (3.29) |

| - Preeclampsia | 4/182 (2.20) |

| - Gestational Diabetes | 11/182 (6.04) |

| - Prelabor rupture of membranes | 13/184 (7.07) |

| - Fetal distress | 23/184 (12.50) |

| Number of patients | |

| - N of patients delivered | 152/185 (82.16) |

| - N of patients still pregnant | 33/185 (17.83) |

| Mode of delivery (N= 152) | |

| - Cesarean delivery | 129/152 (84.87) |

| - Vaginal Delivery | 19/152 (12.5) |

| - Pregnancy termination | 4/152 (2.63) |

| Gestational age at delivery of viable pregnancies (N=148) | |

| - <28 weeks | 0/148 (0.00) |

| - 28 to 31 6/7 weeks | 2/148 (1.35) |

| - 32 to 35 6/7 weeks | 26/148 (17.56) |

| - ≥36 weeks | 96/148 (64.86) |

| - Missing data | 24/148 (16.2) |

| Neonatal Characteristics | Cases N (%) |

| Total N of neonates reported | 146 (100) |

| - Livebirths | 145/146 (99.3) |

| - Stillbirths | 1/146 (0.68) |

| Comorbidities after livebirth (Out of Total N= 145) | |

| - NICU admission | 27/145 (18.60) |

| - Low birth weight | 15/145 (10.34) |

| - Pneumonia | 9/145 (6.20) |

| - RT- PCR SARS-CoV 2 positive | 2/145 (1.37) |

| - Neonatal death | 1/145 (0.69) |

Please note that certain parameters were not evaluated or reported in all patients, so the denominators used for calculations represent only the numbers for which data are available

17.8% (33 of 185) patients were still pregnant at the end of this study; therefore, rates of complications occurring in late pregnancy or close to delivery, such as preeclampsia, might have been underestimated

Management of patients varied according to institution. The majority were treated with medications that are considered to be relatively safe during pregnancy: antibiotics (cefoperazone, sulbactam, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, and azithromycin), antiviral therapy (lopinavir, ritonavir, oseltamivir, and ganciclovir), and a few were treated with corticosteroids (dexamethasone, methylprednisolone).

Due to the high false negative rates of the nasopharyngeal swab for the quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for the SARS-CoV-2 test,60 a CT scan may be required to confirm the diagnosis in cases of high suspicion, as seen in 4 cases reported by Wu et al.54 There were no patients who delivered before 28 weeks gestation and the majority of patients delivered at 36 0/7 weeks or later. The impact of infection on timing of delivery is still unclear. Yangli et al42 reported a 46% preterm labor rate between 32–26 weeks of gestation in 10 patients admitted with positive COVID-19 infection, while Zhang et al45 reported no difference in gestational age at delivery for 16 women with COVID-19 (38.7±1.4) and 45 women without COVID-19 (37.9±1.6).

A systematic review by Zaigham et al61 including 108 pregnant women reported CD was the most common mode of delivery, with a rate of 92%. It can be speculated that SARS-CoV-2 infections are more likely to result in maternal hypoxia or increased oxygen requirements, resulting in a non-reassuring fetal heart tracing, warranting expedited delivery. There may also be lack of SARS-CoV-2 screening in some healthcare settings resulting in selection bias for CD in severe cases. The indication for CD needs to be further evaluated as current guidelines indicate that SARS-CoV-2 infection alone is not an indication for CD.62, 63

A recent multicenter cohort study of severe COVID-19 disease in pregnant patients from 12 US institutions reported that patients were usually admitted with severe disease seven days after onset of symptoms, and typically were intubated 2 days after admission.64 Fifty percent of women required delivery resulting in a high rate of preterm birth.

NEONATAL OUTCOMES

Neonatal outcomes are shown in Table 1. There was one reported stillbirth42 due to severe maternal disease with multi-organ failure, and one neonatal death39 due to refractory shock with multi-organ failure following delivery at 34 5/7 weeks gestation. Among 145 livebirths, 2 neonates tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Both did well with supportive therapy and observation and were discharged from hospital in a stable condition.49, 59

Di Mascio et al38 reported increased perinatal mortality and higher rates of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) admissions, but all neonates tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Chen et al44 confirmed no morphological changes related to infection in three placentas of COVID-19 positive mothers. All 3 neonates also tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. Although these findings are consistent with reports suggesting minimal to no risk of vertical transmission,43, 44, 65 Penfield et al66 reported positive SARS-CoV-2 results in 3 of 11 placental swabs from COVID-19 positive mothers. All of the 3 neonates also tested negative. Whether vertical transmission truly occurred, or whether neonates were swabbed too early-during the incubation period- is unclear.

Shah et al67 published a well-structured classification system and case definition for SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates which gives the opportunity to consider the risk of maternal to fetal or neonatal transmission beyond just vertical transmission. The classification includes congenital infection from intrauterine death/stillbirth, congenital infection in live born infants, neonatal infection acquired intrapartum, or neonatal infection acquired postnatally. In addition, several professional societies have provided guidelines for management of COVID-19 during pregnancy. The overall summaries from these professional bodies are consistent, with some variation in the strength of recommendations.

CURRENT GUIDELINES FOR COVID-19 MANAGEMENT IN PREGNANCY

Professional perinatal societies, including the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine (SMFM)63, 68 and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG)69, 70from the United States, the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (RCOG)62 from the United Kingdom, the International Society for Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG),71 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)72, 73 and the World Health Organization (WHO)74 have developed guidelines for the care of pregnant patients.

Here, we have summarized the most current guidelines, updated as of April 22, 2020. A total of 9 papers were identified from 6 societies - SMFM, ACOG, RCOG, ISUOG, CDC, and WHO.

A summary of these guidelines are outlined in Table 2, and divided into three sections - antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum care. The guidelines provide practical management recommendations that institutions can adapt to their infrastructures and resource availability. The recommendations from the SMFM are focused on high risk pregnancies, while those from ACOG and RCOG focus on all pregnancies. The WHO and CDC both focus on recommendations that can be generalized across all patient populations, while ISUOG focuses on sonography and care of ultrasound equipment.

Table 2:

Consensus on recommendations classified by phase of care of pregnancy

| ANTEPARTUM CARE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Prenatal Infection Screening | Prenatal appointment | Ultrasound frequency | Ultrasound equipment/patient rooms | Antenatal surveillance | Antenatal corticosteroids | GBS screening |

| Consensus on recommendations | -Triage symptomatic patients via

telehealth -Test anyone with new flu like symptoms. Prioritize high risk patients- older, immune- compromised, advanced HIV, homeless, hemodialysis. -Utilize drive through or standalone testing area -All suspected cases should be screened with qRT-PCR -Symptomatic patients should be treated as positive till results are back -Repeat testing in 24 hours if negative, but still high suspicion |

-Elective and non-urgent appointments should

be postponed or completed by telehealth -Encourage use of telehealth for all visits -HCW meetings should all be virtual/audio. -Reserve F2F visits for 1113,20,28,36 weeks and weekly after 37 weeks -Complete labs and US on same visit day -Limit support person at outpatient F2F visits. |

-Consensus: Continue US as medically indicated

when possible. SMFM Suggestions -Combine dating and NT in 1st trimester -Anatomy scan at 20–22weeks - Consider stopping serial CL after anatomy US if TVUS CL >35mm, prior preterm birth at >34 weeks -BMI>40: schedule at 22 weeks to reduce risk of suboptimal views/need for follow up -Single growth F/U at 32 weeks -Low lying placenta F/U 34–36wks |

-Must be cleaned with disinfectant per

manufacturer guidelines after EVERY use -Deep clean of all instruments and room in case of positive patient |

- Reserve for medically indicated

screening -Limit NST <32 weeks -Twice weekly NST only for FGR with abnormal UA Doppler studies, complicated monochorionic twins, or Kell sensitized patients with significant titers -If patient needs US, perform BPP instead of NST -Kick counts instead of NST for low risk patients Daily NST if patient hospitalized |

-Should continue if <34 weeks, even if

tested positive for COVID-19 -Balance risks and benefits for 34 0/7–36 6/7 Weeks -Other modifications should be individualized |

- As indicated between, 36 0/7–37 6/7

weeks gestation. -Consider grouping with other visits within the same time frame -Patients can self-collect with proper instructions if the resources and infrastructure allow |

| INTRAPARTUM CARE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Pre-Delivery preparation/screening | Delivery location | Delivery Time | Mode of delivery | Support person | Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia | Oxygen use | Second Stage of labor | Third stage of labor | Umbilical cord clamping | PPE |

| Consensus on recommendations | -Social distancing and off work for 2 weeks prior to anticipated delivery (start at ~37wks) -Screen patient and partner on phone day before admission -Limit HCW staffing to only essential staff |

-Designated isolation room, for suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 | -Based on routine obstetric

indications -Early delivery should be considered for criticallyill patients -No contraindicat ions to IOL unless there are limited beds |

-Based on routine obstetric

indications -COVID-19 infection is NOT an indication for CD -Expedite delivery by CD in setting of fetal distress or maternal deterioration -Water births should be avoided. |

- Allowed one consistent asymptomatic support person | -No evidence against regional or general

anesthesia. -Epidural analgesia is recommended to women with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to minimize the need for GA if urgent delivery is needed. -Avoid use of nitrous oxide |

-Do not use O2 for intrauterine

resuscitation -Considered aerolizing, HCW must wear appropriate PPE (N95) |

-Do not delay pushing. -Consider shortening with operative delivery to minimize aerolization and maternal respiratory effort |

-Consider active management to reduce blood loss (national blood shortage) | -Delayed cord clamping is still recommended in

the absence of contraindications -Avoid delayed cord clamping in confirmed and suspected cases |

-Asymptomatic or negative patients- Patient

and provider wear surgical mask -Aerolizing procedures- N95 for patient and N95,gown,glov es, face shield for provider |

| POSTPARTUM CARE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Placental and fetal tissue | Length of stay | Breastfeeding | Skin to skin | Postpartum pain control | Postpartum visit |

| Consensus on recommendations |

ISUOG

recommendations -Should be handled as infectious tissue in positive patients -Consider qRT-PCR on placenta |

-Expedited discharge should be considered if

stable. -VD→ 1 day -CD→ 2 days |

-Limited evidence to advice against

breastfeeding. -Advise patients to: 1) Practice respiratory hygiene during feeding, 2) wear a mask 3)Wash hands before and after touching the baby 4)Routinely clean and disinfect surfaces they have touched. -During separation, encourage dedicated breast pumping |

-Routine precautionary separation of a healthy

baby and mother is not advised -Encourage good hygiene and appropriate PPE for COVID-19 positive patients |

-No contraindication to NSAID use | -Encourage telehealth for postpartum

visit -Limit F2F visits only for medically necessary concerns |

qRT-PCR – Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, HCW- Health care workers, F2F- Face to face, F/U- follow up, CD- Cesarean Delivery, IOL- Induction of labor, VD- Vaginal delivery, GBS-Group B streptococcus, VD-Vaginal Delivery

Prenatal/Antepartum Care

The consensus amongst all societies recommends the use of telehealth for prenatal visits. Ultrasound and antenatal surveillance should be combined with visits for labs or prenatal care. Patients should be screened for symptoms, travel history, and contact history before any face to face visits; and those who are symptomatic or meet criteria should undergo testing for SARS-CoV-2 using qRT-PCR. Appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) should be worn by patients and health care workers (HCW). Administration of antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturation should still be considered if a pregnancy is between 24 0/7 to 33 6/7 weeks gestation, but the risk/benefit balance needs to be discussed by the multidisciplinary team. Data on use of steroids during late preterm (34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks) are still controversial, but routine administration is not advised.68

Intrapartum care

Institutions should have a designated area for triaging, screening and admitting SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. The mode and timing of delivery should follow routine obstetric indications, keeping in mind that COVID-19 alone is not an indication for CD, unless there is fetal distress or deteriorating maternal clinical status. Societies recommend that only one consistent healthy asymptomatic individual providing support should be present during labor and delivery. Aerosol generating procedures, including forceful pushing during the second stage of labor and oxygen supplementation for intrauterine resuscitation, should be limited, and appropriate PPE (N95) worn. Water births are contraindicated due to limited ability to monitor mother and baby, and the risk of fecal transmission.

Postpartum care

Mother and baby separation or discouraging breastfeeding is not advised unless the mother is acutely ill. However, mothers are advised to follow appropriate respiratory hygiene by wearing masks during skin to skin contact and breastfeeding. Mothers should wash hands before handling their babies, touching pumps or bottles and avoid coughing while their babies are feeding. All surfaces and breast pumps should be sanitized after each use. In an effort to limit infection exposure, hospital length of stay should be decreased to 1 day for vaginal deliveries and 2 days for CD. Postpartum visits should be performed through telehealth and patients advised to continue compliance with social distancing after discharge. The method of telehealth should be individualized based on institution resources and availability.

IMPLICATIONS OF COVID-19 IN SPECIAL PREGNANT PATIENT POPULATIONS

Evidence on the potential outcomes of SARS-CoV2 in pregnancies already complicated by congenital anomalies is lacking. Given the severity of some potentially life-threatening congenital conditions as well as the disease altering effects of fetal interventions, these procedures are considered urgent essential medical services. Therefore, necessary adjustments to the prenatal work-up and selection of fetal intervention candidates have been proposed to better adapt this essential service to the ongoing pandemic. Perhaps the most important factor to consider is the potential risk of vertical transmission induced by the invasive nature of these procedures.

There is no definitive evidence of in utero transmission from SARS-CoV-2 to date. Some case reports52, 59, 75 have reported possible vertical transmission due to positive amniotic fluid SARS-CoV-2 PCR, but the majority of the limited patient series reported in the literature indicate a low-to-negligible risk.76, 77 Evidence is rapidly accumulating, however, and this consensus may change as more cases of COVID-19 in pregnancy are reported.

Prenatal diagnosis

In the event of a suspected or confirmed fetal anomaly, additional work-up (fetal echocardiography, amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or cordocentesis) may be indicated to identify patients who could benefit from fetal interventions.

Prenatal diagnostic work-ups may be classified as invasive or non-invasive depending on the risk of vertical transmission and exposure of patients and HCW to SARS-CoV-2. Imaging studies, including ultrasound and fetal echocardiography, are considered non-invasive (with no risk of vertical transmission), but specific precautions including hygiene and use of appropriate PPE should be applied to the patient and examiner, as well as proper care of the sonogram and ultrasound suite.78 For patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, consideration should be given to postponing prenatal imaging until asymptomatic, if safely feasible.

Invasive diagnostic tests (CVS, amniocentesis, and cordocentesis) are associated with a theoretical risk of vertical transmission, as these procedures may directly correlate with the risk of feto-maternal hemorrhage.76 CVS, which is usually performed between 10 0/7 to 13 6/7 weeks gestation, may be offered to patients with low risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (asymptomatic or negative screen). For symptomatic patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2, invasive diagnostic tests can be delayed if safely feasible. If genetic testing cannot be delayed, amniocentesis (usually performed after 14 0/7 weeks gestation) should be performed instead of CVS, due to the theoretical lower risk of vertical transmission if trans-placental access is avoided. Amniocentesis can also be offered to all asymptomatic or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 negative patients.76 Fetal blood sampling/transfusion is another invasive procedure with a theoretical risk of vertical transmission. This intervention may be offered to patients with confirmed negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR, but should be delayed (if feasible and safe) in symptomatic or positive SARS-CoV-2 cases.76

Fetal therapy

The Mayo Clinic Fetal Center follows the recommendations of the North American Fetal Therapy Network (NAFTNET) which currently recommends that fetal interventions should be provided as much as resources allow due to the time sensitive nature of conditions amenable to fetal therapy.79 Specific institutional policies may vary, but in general, all fetal interventions which have been established as the standard of care (for select patients) should continue to be provided, taking the necessary perioperative precautions. Conversely, innovative or experimental procedures which are yet to show proven benefit should be individualized. In general, for asymptomatic COVID-19 patients, fetal intervention can be offered. For symptomatic patients, it is recommended that fetal therapy be postponed until maternal conditions stabilize and patients have recovered from the disease. Some examples of fetal surgeries that are still currently offered at Mayo Clinic include: Fetoscopic laser ablation of placental anastomoses for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome,80 in utero repair of spina bifida,81 intrauterine fetal blood transfusion,82 in utero intervention for lower urinary tract obstruction,83 fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion for congenital diaphragmatic hernia,84, in utero procedure for fetal tumors associated with hydrops,85 and in utero intervention for severe congenital heart defects.86

TREATMENT OF COVID-19 IN PREGNANT PATIENTS

No drugs have been proven to be effective and safe to use for the treatment of COVID-19 to date. Table 3 outlines the medications or therapies used in various research protocols under investigation, as well as their safety for use in pregnancy. In addition, as the pro-coagulatory state of pregnancy may contribute to thrombotic risks associated with COVID-19, thrombo-prophylaxis, which is currently advised for COVID 19 patients,87 should be considered for pregnant patients as well.

Table 3:

Treatment options for COVID-19

| Treatment Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Effectiveness | Safety in Pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)/Chloroquine93 | Reduces inflammatory cytokines;94 interferes with ACE 2 receptor synthesis94, 95 | Reduction of body temperature recovery time and cough remission, pneumonia recovery, improved CT scan findings, nasopharyngeal viral clearance96–98 | Generally considered safe in pregnancy and frequently used for patients with autoimmune disease.99 Efficacy unproven. Concern for prolonged QTc. |

| HCQ and Azithromycin | Reduction of viral replication and Interleukins 6 and 8 production94, 100 | Improved nasopharyngeal viral clearance97 | HCQ: as above Azithromycin: considered safe101 |

| Lopinavir/rotinavir | Inhibition of 3-chymotrypsin-like protease102–104 | Reduced mortality105 | Good safety profile in pregnant patients with HIV106 |

| Remdesivir | Inhibition of viral RNA- dependent RNA polymerase107 | Clinical trial still underway Reduction in duration of hospital stay and mortality108 |

Not yet FDA approved |

| Anakinra | Interleukin - 1 inhibitor | Clinical trial still underway | Insufficient data to determine risk in pregnancy109 |

| Siltuximab | Human-mouse chimeric monoclonal antibody against Interleukin-6 | Improvement in clinical condition in 1/3 patients110 | Insufficient data to determine risk in pregnancy111 |

| Sarilumab | Recombinant interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody | No data yet from randomized clinical trials or observational studies93 | Insufficient data to determine risk in pregnancy93 |

| Tocilizumab | Recombinant interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody | No data yet from randomized clinical trials or observational studies93 | Insufficient data to determine risk in pregnancy93 |

| Interferon | Antiviral cytokines | No data yet from randomized clinical trials or observational studies93 | Varying side effect profiles in various preparations |

| Corticosteroid | Anti-inflammatory actions112 | Reduced mortality in ARDS patients113 Faster improvement of severe COVID pneumonia patients114 |

Considered safe, approved for lung maturation in preterm birth115 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) | ACE receptor 2, is the cell receptor for viral entry for COVID 19 virus116, 117 | No data yet from randomized clinical trials or observational studies93 | Contraindicated in pregnancy118, 119 |

| Convalescent Plasma | Convalescent plasma from recently recovered donors targeted COVID 19 virus | 10 clinically severe COVID 19 patients were

given 200ml of convalescent plasma. Increase in oxyhemoglobin saturation

by 3rd day, and improved lymphocyte count as well as CRP

levels were noted. Several studies are currently underway120 |

No data on safety in pregnancy. However, specific immunoglobulins as for varicella are used in pregnancy111 |

ARDS- Acute respiratory Distress Syndrome, CRP- C-reactive protein

There are 6 total candidate vaccines under phase 1 or 2 clinical trials and 77 more candidate vaccines in pre-clinical evaluation, as of April 23, 2020.88 Many vaccines use the spike protein (S protein) as their platform and present as forms of recombinant protein based vaccines, live attenuated vaccines, inactive viral vaccines and viral-vector based vaccines.89 Live, attenuated vaccines are generally contraindicated in pregnancy, but exceptions may be made during pandemic situations (exception for Smallpox vaccine). As with any drug under development, assessment for safety in pregnancy is conducted after initial safety data become available from clinical studies.90 Although it is essential to guarantee safety, an unfortunate impact of delaying research in pregnancy is that vaccinations for pregnant women may also be delayed. This is especially problematic during a pandemic or epidemic, as evident from lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak.91

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The presented data are preliminary, collected over a period of 4 months and likely to change once large datasets become available. However, the projected course of COVID-19 on the morbidity and mortality of pregnant patients during these challenging times is unprecedented. Racial disparities are known to exist in the obstetric literature.92 Global health crises subject racial and ethnic minorities, as well as patients with immunocompromised comorbidities, to poorer outcomes. We envision that national and international perinatal societies will focus on the unique challenges faced by vulnerable patient populations that are burdened with physical, emotional and social crises, with a focus on improving outcomes for all pregnant patients.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, given differing physiology during gestation, pregnancy represents a vulnerable state that may be associated with a greater risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent worse COVID-19 outcomes. Global efforts to fast track publication of data on COVID-19 in pregnancy, albeit limited, have allowed us to form a framework to care for these patients. Early reports suggest higher rates of preeclampsia and other pregnancy-related complications with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy, thus adding urgency to the pursuit of research into optimal COVID-19 treatment and preventive strategies during pregnancy.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS.

Physiologic, metabolic, and vascular changes in normal and high-risk pregnancies may affect risks for SARS-CoV-2 infection and modify/exacerbate the clinical presentation of COVID-19.

Pregnant women may be at greater risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection, with more severe COVID-19 symptoms, and worse pregnancy outcomes.

Studies to date have demonstrated higher risks of pregnancy complications, including preterm birth and preeclampsia, as well as higher rates of cesarean delivery.

Pharmacological therapy is limited to medications with proven safety during pregnancy and lactation; safety data are often unavailable for medications in early stages of clinical trials.

The current recommendations are based on a limited number of studies. Future, large, likely multi-center, studies will be critical in improving our understanding of the pathophysiology and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 and pregnancy, which may optimize COVID-19 preventive and treatment strategies during normal and high risk pregnancies.

Acknowledgments:

Margaret A. McKinney M.S., for assistance with media and illustration support

Funding support:

R01-HL136348

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- ACE 2

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane serine protease 2

- RAAS

Renin angiotensin aldosterone system

- Ang II

Angiotensin II

- Th

T helper

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- RV

Residual volume

- TV

Tidal volume

- CD

Cesarean Delivery

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- ACOG

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- SMFM

Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine

- RCOG

Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- ISUOG

International Society for Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- WHO

World Health Organization

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- HCW

Healthcare workers

- PPE

Personal protective equipment

- CVS

Chorionic villus sampling

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Loeffelholz MJ, Tang YW. Laboratory diagnosis of emerging human coronavirus infections - the state of the art. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:747–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, et al. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nature Microbiology. 2020;5:536–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Macfarlane K, Cragan JD, Williams J, Henderson Z. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women: summary of a meeting of experts. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 Suppl 2:S248–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prajapat M, Sarma P, Shekhar N, et al. Drug targets for corona virus: A systematic review. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52:56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss SR, Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus Pathogenesis and the Emerging Pathogen Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2005;69:635–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutard B, Valle C, de Lamballerie X, Canard B, Seidah NG, Decroly E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res. 2020;176:104742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brosnihan KB, Neves LA, Anton L, Joyner J, Valdes G, Merrill DC. Enhanced expression of Ang-(1–7) during pregnancy. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1255–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West CA, Sasser JM, Baylis C. The enigma of continual plasma volume expansion in pregnancy: critical role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F1125–f1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merrill DC, Karoly M, Chen K, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Angiotensin-(1–7) in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Endocrine. 2002;18:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garovic VD, White WM, Vaughan L, et al. Incidence and Long-Term Outcomes of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2323–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lumbers ER, Delforce SJ, Arthurs AL, Pringle KG. Causes and Consequences of the Dysregulated Maternal Renin-Angiotensin System in Preeclampsia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glowacka I, Bertram S, Herzog P, et al. Differential downregulation of ACE2 by the spike proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus NL63. J Virol. 2010;84:1198–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrario CM, Trask AJ, Jessup JA. Advances in biochemical and functional roles of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1–7) in regulation of cardiovascular function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2281–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garovic VD, Hayman SR. Hypertension in pregnancy: an emerging risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020:S0049–3848(0020)30120–30121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie Y, Wang X, Yang P, Zhang S. COVID-19 Complicated by Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2:e200067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garovic VD, Hayman SR. Hypertension in pregnancy: an emerging risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Nature clinical practice. Nephrology 2007;3:613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alrahmani L, Willrich MAV. The Complement Alternative Pathway and Preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risitano AM, Mastellos DC, Huber-Lang M, et al. Complement as a target in COVID-19? Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aghaeepour N, Ganio EA, McIlwain D, et al. An immune clock of human pregnancy. Sci Immunol. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enninga EA, Nevala WK, Creedon DJ, Markovic SN, Holtan SG. Fetal sex-based differences in maternal hormones, angiogenic factors, and immune mediators during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73:251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mor G, Aldo P, Alvero AB. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:469–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breslin N, Baptiste C, Miller R, et al. COVID-19 in pregnancy: early lessons. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 2020:100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, et al. COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: Two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. American journal of obstetrics & gynecology MFM. 2020:100118–100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi GB, Yim YS, Wong H, et al. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science. 2016;351:933–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei J, Vermillion MS, Jia B, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist therapy mitigates placental dysfunction and perinatal injury following Zika virus infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mednick SA, Machon RA, Huttunen MO, Bonett D. Adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to an influenza epidemic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303:1517–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang X, Gao X, Zheng H, et al. Specific Immunoglobulin G Antibody Detected in Umbilical Blood and Amniotic Fluid from a Pregnant Woman Infected by the Coronavirus Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2004;11:1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Respiratory physiology in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(SMFM) SfMFM. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Management Considerations for Pregnant Patients With COVID-19 Developed with guidance from Torre Halscott, MD, MS and Jason Vaught, MD2020.

- 34.Schwartz DA. An Analysis of 38 Pregnant Women with COVID-19, Their Newborn Infants, and Maternal-Fetal Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Maternal Coronavirus Infections and Pregnancy Outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juusela A, Nazir M, Gimovsky M. Two cases of coronavirus 2019–related cardiomyopathy in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 2020:100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang C, Shi L, Wang FS. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Mascio D, Khalil A, Saccone G, et al. Outcome of Coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID 1 −19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of obstetrics & gynecology MFM. 2020:100107–100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu H, Wang L, Fang C, et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Translational Pediatrics. 2020;9:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Zhu F, Tang Y, Shen X. A Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in a Pregnant Woman With Preterm Delivery. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, Huang B, Luo DJ, et al. [Pregnant women with new coronavirus infection: a clinical characteristics and placental pathological analysis of three cases]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:E005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Chen H, Tang K, Guo Y. Clinical manifestations and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. Journal of Infection. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang L, Ruihong Z, Shufa Z, et al. Lack of Vertical Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, China. Emerging Infectious Disease journal. 2020;26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. The Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, et al. [Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 in Hubei Province]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020;55:E009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu D, Li L, Wu X, et al. Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Women With Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: A Preliminary Analysis. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wen R, Sun Y, Xing Q-S. A patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy in Qingdao, China. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li N, Han L, Peng M, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia: a case-control study. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2003.2010.20033605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu N, Li W, Kang Q, et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia H, Zhao S, Wu Z, Luo H, Zhou C, Chen X. Emergency Caesarean delivery in a patient with confirmed COVID-19 under spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124:e216–e218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen R, Zhang Y, Huang L, Cheng B-h, Xia Z-y, Meng Q-t. Safety and efficacy of different anesthetic regimens for parturients with COVID-19 undergoing Cesarean delivery: a case series of 17 patients. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dong L, Tian J, He S, et al. Possible Vertical Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 From an Infected Mother to Her Newborn. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zambrano LI, Fuentes-Barahona IC, Bejarano-Torres DA, et al. A pregnant woman with COVID-19 in Central America. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020:101639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu X, Sun R, Chen J, Xie Y, Zhang S, Wang X. Radiological findings and clinical characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 pneumonia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. Published: April 8, 2020. 10.1002/ijgo.13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiong X, Wei H, Zhang Z, et al. Vaginal Delivery Report of a Healthy Neonate Born to a Convalescent Mother with COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology. Published Online ahead of print April 10, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peng Z, Wang J, Mo Y, et al. Unlikely SARS-CoV-2 vertical transmission from mother to child: A case report. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lowe B, Bopp B. COVID-19 vaginal delivery – a case report. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Published online ahead of print April 15, 2020. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vlachodimitropoulou Koumoutsea E, Vivanti AJ, Shehata N, et al. COVID19 and acute coagulopathy in pregnancy. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Published online ahead of print April 17, 2020. 10.1111/jth.14856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zamaniyan M, Ebadi A, Aghajanpoor Mir S, Rahmani Z, Haghshenas M, Azizi S. Preterm delivery in pregnant woman with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and vertical transmission. Prenat Diagn. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kelly JC, Dombrowksi M, O’neil-Callahan M, Kernberg AS, Frolova AI, Stout MJ. False-Negative COVID-19 Testing: Considerations in Obstetrical Care. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 2020:100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.(RCOG) RCoOaG. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy: information for healthcare professionals. 2020.

- 63.Boelig RC, Saccone G, Bellussi F, Berghella V. MFM Guidance for COVID-19. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 2020:100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pierce-Williams RAM. Clinical course of severe and critical COVID-19 in hospitalized pregnancies: a US cohort study. AJOG-SMFM2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from (Wuhan) Coronavirus 2019-nCoV Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections. Viruses. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Penfield C Detection of SARS-COV-2 in Placental and Fetal Membrane Samples American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (MFM): AJOG-SMFM; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shah PS, Diambomba Y, Acharya G, Morris SK, Bitnun A. Classification system and case definition for SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:565–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boelig RC, Manuck T, Oliver EA, et al. Labor and Delivery Guidance for COVID-19. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 2020:100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.(ACOG) ACoOaG. Novel Coronavirus COVID-19, a practice advisory2020.

- 70.(ACOG) ACoOaG. COVID-19 FAQs for Obstetrician-Gynecologists, Obstetrics2020.

- 71.Poon LC, Yang H, Lee JCS, et al. ISUOG Interim Guidance on 2019 novel coronavirus infection during pregnancy and puerperium: information for healthcare professionals. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. Published online ahead of print March 11, 2020. 10.1002/uog.22013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.(CDC) CDC. Information for Healthcare Providers: COVID-19 and Pregnant Women 2020.

- 73.(CDC) CfDC. Pregnany and Breastfeeding2020.

- 74.(WHO) WHO. Q&A on COVID-19, pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding2020.

- 75.Yu N, Li W, Kang Q, et al. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deprest J, Van Ranst M, Lannoo L, et al. SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) infection: is fetal surgery in times of national disasters reasonable? Prenat Diagn. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karimi-Zarchi M, Neamatzadeh H, Dastgheib SA, et al. Vertical Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) from Infected Pregnant Mothers to Neonates: A Review. Fetal and pediatric pathology. 2020:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abu-Rustum RS, Akolekar R, Sotiriadis A, et al. ISUOG Consensus Statement on organization of routine and specialist obstetric ultrasound services in the context of COVID-19. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bahtiyar MO, Baschat A, Deprest J, et al. Fetal Interventions in the Setting of COVID-19 Pandemic: Statement from the North American Fetal Therapy Network (NAFTNet). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruano R, Rodo C, Peiro JL, et al. Fetoscopic laser ablation of placental anastomoses in twin-twin transfusion syndrome using ‘Solomon technique’. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;42:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ruano R, Daniels DJ, Ahn ES, et al. In Utero Restoration of Hindbrain Herniation in Fetal Myelomeningocele as Part of Prenatal Regenerative Therapy Program at Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2020;95:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lindenburg IT, van Kamp IL, Oepkes D. Intrauterine blood transfusion: current indications and associated risks. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2014;36:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ruano R, Sananes N, Wilson C, et al. Fetal lower urinary tract obstruction: proposal for standardized multidisciplinary prenatal management based on disease severity. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;48:476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ruano R, Yoshisaki CT, da Silva MM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion versus postnatal management of severe isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;39:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nassr AA, Ness A, Hosseinzadeh P, et al. Outcome and Treatment of Antenatally Diagnosed Nonimmune Hydrops Fetalis. Fetal diagnosis and therapy. 2018;43:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Said SM, Qureshi MY, Taggart NW, et al. Innovative 2-Step Management Strategy Utilizing EXIT Procedure for a Fetus With Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome and Intact Atrial Septum. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019;94:356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2020;18:1023–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.WHO.int. DRAFT landscape of COVID-19 candidate vaccines – 23 April 2020. Vol 2020.

- 89.Amanat F, Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Status Report. Immunity. 2020;52:583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.FDA. Postapproval Pregnancy Safety Studies: Guidance for Industry. Vol 2020.

- 91.Gomes MF, de la Fuente-Núñez V, Saxena A, Kuesel AC. Protected to death: systematic exclusion of pregnant women from Ebola virus disease trials. Reprod Health. 2017;14:172–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 649: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.NIH. COVID-19 Treatment Guidlines. Vol 2020.

- 94.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.CHEN Jun LD, LIU Li,LIU Ping,XU Qingnian,XIA Lu,LING Yun,HUANG Dan,SONG Shuli,ZHANG Dandan,QIAN Zhiping,LI Tao,SHEN Yinzhong,LU Hongzhou. A pilot study of hydroxychloroquine in treatment of patients with common coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020;49:0–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, et al. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: A pilot observational study. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2020:101663–101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li Y, Xie Z, Lin W, et al. An exploratory randomized controlled study on the efficacy and safety of lopinavir/ritonavir or arbidol treating adult patients hospitalized with mild/moderate COVID-19 (ELACOI). medRxiv. 2020:2020.2003.2019.20038984. [Google Scholar]

- 99.FDA. PLAQUENIL® HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE SULFATE, USP. Vol 2020.

- 100.Gielen V, Johnston SL, Edwards MR. Azithromycin induces anti-viral responses in bronchial epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.FDA. ZITHROMAX® (azithromycin tablets) and (azithromycin for oral suspension). Vol 2020.

- 102.Zumla A, Chan JF, Azhar EI, Hui DS, Yuen KY. Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ul Qamar MT, Alqahtani SM, Alamri MA, Chen LL. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CL(pro) and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. J Pharm Anal. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu X, Wang X-J. Potential inhibitors against 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. J Genet Genomics. 2020;47:119–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.NIH. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Vol 2020.

- 107.Warren TK, Jordan R, Lo MK, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2016;531:381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Marchione MA 1st: US study finds Gilead drug works against coronavirus. Vol 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Anakinra. Vol 2020.

- 110.Gritti G, Raimondi F, Ripamonti D, et al. Use of siltuximab in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia requiring ventilatory support. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2004.2001.20048561. [Google Scholar]

- 111.NIH. Host Modifiers and Immune-Based Therapy Under Evaluation for Treatment of COVID-19. Vol 2020.

- 112.Barnes PJ. How corticosteroids control inflammation: Quintiles Prize Lecture 2005. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, et al. Early, low-dose and short-term application of corticosteroid treatment in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: single-center experience from Wuhan, China. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2003.2006.20032342. [Google Scholar]

- 115.ACOG. Practice advisory: novel coronavirus 2019. Vol 2020.

- 116.Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:221–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gralinski LE, Menachery VD. Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses. 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.FDA. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Pregnancy: FDA Public Health Advisory. Vol 2020.

- 119.Barreras A, Gurk-Turner C. Angiotensin II receptor blockers. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16:123–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Duan K, Liu B, Li C, et al. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]