1. INTRODUCTION

Permanent structural changes in brains of those with chronic pain [2,7,11,25] resemble that seen in neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia [3]. Pain dimensions, namely sensory-discriminative, cognitive-evaluative, and affective motivational, are known to activate a wide network of brain regions [13,19]. It is likely that there is an overlap in structural brain changes in chronic pain and dementia. Chronic pain affects cognitive, mood, and mental status [6,10], and is also a feature of dementia [8,12]. However, the long-term association between pain and dementia remains unclear; pain could be a cause, correlate, or a prodromal feature of dementia.

Associations of pain or painful chronic conditions with cognitive decline [5,20–22,28,29] and dementia have been documented in several studies [9,15,27,33,36,37,39]; however few studies have examined the temporal nature of this association and the evidence is inconsistent. Most aforementioned studies were conducted amongst older populations and had less than five year mean follow-up. Given that dementia is characterized by a preclinical period lasting 15–20 years [24], it is possible that previous findings were affected by reverse causation whereby the observed association is primarily due to increase in pain in the preclinical period of dementia.

Accordingly, our objective was to examine the temporal association between pain scores, composed of pain interference and pain intensity, and incident dementia using time-to-event analysis with mean duration between pain assessment and dementia diagnosis varying from 25 to 3.2 years. Complementarily, we characterized pain trajectories, in almost three decades preceding dementia diagnosis and compared them to those observed among persons free of dementia during the same period.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

The Whitehall II study is an ongoing population based cohort started in 1985 among 10308 British civil servants (6895 men, 3413 women), aged 35 to 55 years. Data collection involves questionnaires on health behaviors, physical and mental well-being every two to three years, and clinical examinations including anthropometric measures and health-related parameters every four to five years until the most recent examination in 2015–2016. Participants’ written, informed consent and research ethics approval are renewed at each contact; the most recent approval was from the NHS London - Harrow Research Ethics Committee, reference number 85/0938.

2.2. Pain

Pain was assessed using the ‘bodily pain scale’ of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire on 9 occasions since its introduction to the study in 1991–1993 (in 1995, 1997–1999, 2001, 2002–2004, 2006, 2007–2009, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016). SF-36 assesses quality of life based on eight scales [35] (vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning, and mental health) of which the bodily pain scale has been used for assessment of pain in previous studies [9]. The bodily pain scale is composed of two questions that assess pain intensity and pain interference “over the last four weeks”. Intensity measurement ranges from none (scored 100), very mild (scored 80), mild (scored 60), moderate (scored 40), severe (scored 20) to very severe (scored 0). Similarly, interference measurement ranges from not at all (scored 100), a little bit (scored 75), moderately (scored 50), quite a bit (scored 25) up to extremely (scored 0). Total pain is calculated by averaging the pain intensity and interference scores. To ease interpretation, the usual scoring was reversed such that higher scores on pain intensity, pain interference and total pain indicated higher pain levels. The following three continuous pain measures were used: “Total pain”, “Pain intensity” and “Pain interference”. We also categorized these measures into two groups: “moderate to severe” and “mild or no” pain.

2.3. Incidence of dementia

Dementia was ascertained by linkage to three electronic health records: Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS), and mortality register up to the 31st March 2019 using a unique National Health Service (NHS) identifier for each individual. Dementia cases were identified based on ICD-10 codes F00, F01, F02, F03, F05.1, G30, G31.0, G31.1, and G31.8 (Table S1); the date of diagnosis was set at the first record of disease in these databases. The sensitivity and specificity of dementia diagnosis in HES data has been reported to be 78.0% and 92.0% [26]. Additional use of MHSDS in our study is likely to improve sensitivity of dementia diagnosis [38].

2.4. Covariates

Sociodemographic factors included age, birth cohort (in five year bands), sex, ethnicity (Caucasian, other), education (less than primary school, lower secondary school, higher secondary school, university, and higher university degree), and marital status (married/cohabiting, others) at the time of pain evaluation. Questionnaire data, electronic health records, or clinical examinations over the follow-up were used for the following health conditions: 1) a multimorbidity index comprising coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancers (except non-melanoma skin cancers), type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson’s disease and obesity (based on body mass index ≥ 30kg/m); 2) depression based on electronic health records and use of anti-depressants; and 3) pain medication based on use of analgesic and anti-rheumatic medications.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study population as a function of dementia status at the end of the follow-up were compared using Pearson’s Chi square and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Then two sets of analysis were performed, as described below.

Time to event analysis

We used Cox regression to assess the association between pain measurements (separately for continuous and dichotomized scores) in 1991–1993 and incident dementia. These analyses were repeated with pain measurements drawn from 1997–1999, 2003–2004, 2008–2009, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016 to assess whether the length of the follow-up had an impact on observed associations. Participants were censored at dementia diagnosis, death, or 31st March 2019, whichever came first. Age was used as the time-scale, and analysis was stratified on birth cohort and initially adjusted for sex, ethnicity, marital status, education (Model 1); then also for multimorbidity index, depression, and pain medication use at the time of pain measurement (Model 2). Analyses were undertaken using pain as a continuous (10-point increase) and a dichotomous measure (“moderate to severe” pain vs. “mild or no pain”).

Retrospective analysis of 27-year pain trajectories

This analysis aimed at comparing individual pain trajectories in dementia cases with non-cases among the study population. We used mixed linear models with continuous pain variables as the dependent variables and a backward timescale, such that index date (date of dementia diagnosis for cases and the earliest of 31st March 2019 or date of death for non-cases) was year 0, and pain measures were modeled from year 0 to year -27. Similar analyses were undertaken for dichotomized pain measures (“moderate to severe” vs. “mild or no” pain) using mixed logistic models. Mixed models have the advantage to use all available data over the follow-up, handle differences in length of follow-up, and account for the correlation of the repeated measures on the same individual. Cubic spline regression curves based on mixed models suggested the use of time, time2 and time3 terms (slope terms) to model nonlinear changes in pain trajectories (see Figure S1 and S2 in the supplement). Random effects for the intercept and time allowed individual differences in pain score at intercept (Year 0) and change in pain over time. Analyses were adjusted for age at year 0, sex, education, ethnicity, marital status, dementia status, the terms for slope, interaction between these covariates and the terms for slope, and for birth cohort (Model 1). The analyses were then also adjusted for pain medication use, multimorbidity index, and depression at the time of pain measurement (Model 2). The beta associated with the dementia term yielded the difference in pain at year 0 between dementia cases and non-cases. The interaction term between dementia and slope terms denoted whether change in pain over the previous 27 years differed by dementia status. The differences in pain between cases and non-cases for each of the 27 years of the follow-up were estimated using the MARGINS commands in STATA. All analyses were performed using STATA 15.1(64-bit). All resulting P-values were two-tailed and a P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population characteristics

Of the 10308 participants at study inception (1985–1988), 9284 had participated in at least one of the waves between 1991–1993 and 2015–2016 among whom 238 participants had missing data on pain or covariates, leaving a study population of 9046 (2840 women and 6206 men) participants (flowchart in Figure S3 in the supplement). Compared to excluded study participants, those included were more likely to be younger (included vs. excluded participants mean age 44.8 vs. 45.7 years in 1985; P<0.001), men (68.6% vs. 54.6%; P<0.001), Caucasian (90.7% vs. 77.5%, P<0.001), married/cohabiting (75.0% vs. 67.1%; P<0.001), and to have university education (27.1% vs. 17.1%; P<0.001) (Table S2 in the supplement).

Amongst the 9046 study participants, 567 developed dementia at the mean age of 77.0 (Standard Deviation (SD) = 5.9) years over the mean 25 years of follow-up, 56.1% of these cases were diagnosed in the last five years of follow-up. Table 1 shows that dementia cases were more likely to be older (mean age = 55.8 vs. 50.3 years, P<0.001), women (39.5% vs. 30.9%, P<0.001) and less likely to be Caucasians (86.4% vs. 91.0%, P<0.001) and to have university education (21.0% vs. 27.5%, P<0.001), and presented more often with chronic diseases (23.8% vs. 15.9%, P<0.001), and depression (4.8% vs. 3.1%, P=0.03). Dementia cases also had higher mean pain scores at first wave of pain measurement (19.4 vs. 15.7 for total pain, P<0.001) which became larger at the last wave of pain measurement (Table 1). On average 6.9 pain measures were recorded in non-cases and 5.8 in dementia cases. There was no evidence of sex differences in associations of pain with dementia (Pinteraction>0.07) leading us to combine both sexes in the analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants as a function of dementia status at the end of follow-upa (March 31, 2019).

| No dementia | Dementia | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=8479 | N=567 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Women | 2616 | 30.9 | 224 | 39.5 | <0.001 |

| Caucasian | 7713 | 91.0 | 490 | 86.4 | <0.001 |

| University level education | 2329 | 27.5 | 119 | 21.0 | <0.001 |

|

Characteristics at the first wave of pain measurement | |||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 6480 | 76.4 | 412 | 72.7 | 0.04 |

| Depression | 263 | 3.1 | 27 | 4.8 | 0.03 |

| Pain medication use | 559 | 6.6 | 48 | 8.5 | 0.08 |

| At least one chronic diseaseb | 1345 | 15.9 | 135 | 23.8 | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||

| Total pain (Score > 32.5) | 1125 | 13.3 | 104 | 18.3 | 0.001 |

| Pain intensity (Score > 40) | 1272 | 15.0 | 120 | 21.2 | <0.001 |

| Pain interference (Score > 25) | 686 | 8.1 | 74 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age, y | 50.3 | 6.3 | 55.8 | 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Pain variables | |||||

| Total pain | 15.7 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 22.2 | <0.001 |

| Pain intensity | 21.9 | 23.4 | 25.9 | 25.5 | <0.001 |

| Pain interference | 9.4 | 18.8 | 12.9 | 22.3 | <0.001 |

|

Characteristics at last wave of pain measurement | |||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 6017 | 71.0 | 363 | 64.0 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 957 | 11.3 | 104 | 18.3 | <0.001 |

| Pain medication use | 1453 | 17.1 | 116 | 20.5 | 0.04 |

| At least one chronic diseaseb | 4416 | 52.1 | 335 | 59.1 | 0.001 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||

| Total pain (Score > 32.5) | 2119 | 25.0 | 228 | 40.2 | <0.001 |

| Pain intensity (Score > 40) | 2160 | 25.5 | 209 | 36.9 | <0.001 |

| Pain interference (Score > 25) | 1472 | 17.4 | 182 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age, y | 68.9 | 8.6 | 70.9 | 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Pain variables | |||||

| Total pain | 24.2 | 22.7 | 31.2 | 26.7 | <0.001 |

| Pain intensity | 31.2 | 24.5 | 35.6 | 27.3 | <0.001 |

| Pain interference | 17.3 | 24.1 | 26.7 | 29.1 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: SD, Standard Deviation.

Among participants with data at least once over the follow-up period.

Chronic diseases: coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancers, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson’s disease and obesity.

3.2. Association between pain and incident dementia

Table 2 shows results from Cox regression for the associations of continuous and dichotomized pain score measures recorded at 1991–1993, 1997–1999, 2003–2004, 2007–2009, 2012–2013 and 2015–2016 with incident dementia, using a mean follow-up of 25.0, 19.6, 14.5, 10.0, 6.2 and 3.2 years respectively. In analysis not adjusted for health conditions (Model 1), the continuous pain interference was associated with increased hazard ratio of dementia, irrespective of the length of the follow-up (time between pain assessment and date of dementia diagnosis or end of follow-up for non-cases). In the fully adjusted analyses (Model 2), the association remained only when the mean follow-up was 10 years (hazard ratio (HR) per 10-increase=1.06; 95%CI: 1.01, 1.11; P=0.03) or less. The association between the dichotomized pain measures and dementia strengthened as the follow-up became shorter, when mean follow-up was 3.2 years total pain (HR=2.17; 95%CI: 1.40, 3.38; P=0.001), pain intensity (HR=1.59; 95%CI: 1.01, 2.50; P=0.05), and interference (HR=2.57; 95%CI: 1.61, 4.09; P<0.001) were all associated with dementia in fully adjusted analyses.

Table 2.

Association between pain (continuous (10-point increase) and dichotomous measures) and incident dementia: analysis using Cox regression.

| Total pain |

Pain intensity |

Pain interference |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N cases/ N total | Model 1a | Model 2b | N cases/ N total | Model 1a | Model 2b | N cases/ N Total | Model 1a | Model 2b | |||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Pain in 1991–1993 (Mean follow-up = 25.0y, SD = 4.7) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain score | 508/8281 | 1.05c | 1.01, 1.10 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 | 508/8281 | 1.04c | 1.00, 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.07 | 508/8281 | 1.05c | 1.00, 1.09 | 1.03 | 0.99, 1.08 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||||||||||||

| No | 427/7240 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 410/7057 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 454/7665 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. |

| Yes | 81/1041 | 1.20 | 0.94, 1.52 | 1.12 | 0.87, 1.44 | 98/1224 | 1.25 | 0.99, 1.57 | 1.19 | 0.95, 1.51 | 54/616 | 1.29 | 0.97, 1.72 | 1.21 | 0.90, 1.63 |

| Pain in 1997–1999 (Mean follow-up = 19.6y, SD = 3.8) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain score | 425/7026 | 1.07d | 1.03, 1.12 | 1.05c | 1.00, 1.10 | 425/7026 | 1.06d | 1.02, 1.10 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.08 | 425/7026 | 1.07d | 1.02, 1.11 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||||||||||||

| No | 334/5879 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 327/5814 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 357/6300 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. |

| Yes | 91/1147 | 1.23 | 0.97, 1.57 | 1.10 | 0.85, 1.42 | 98/1212 | 1.29c | 1.02, 1.63 | 1.17 | 0.91, 1.50 | 68/726 | 1.44d | 1.11, 1.88 | 1.27 | 0.96, 1.69 |

| Pain in 2002–2004 (Mean follow-up = 14.5y, SD = 2.9) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain score | 397/6752 | 1.04 | 0.99, 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.07 | 397/6752 | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.05 | 397/6752 | 1.05c | 1.01, 1.10 | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.08 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||||||||||||

| No | 291/5434 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 291/5317 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 324/5939 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. |

| Yes | 106/1318 | 1.33c | 1.05, 1.67 | 1.19 | 0.93, 1.54 | 106/1435 | 1.20 | 0.95, 1.51 | 1.06 | 0.83, 1.37 | 73/813 | 1.36c | 1.05, 1.77 | 1.21 | 0.90, 1.62 |

| Pain in 2007–2009 (Mean follow-up = 10.0y, SD = 2.0) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain score | 329/6588 | 1.06c | 1.01, 1.12 | 1.03 | 0.97, 1.09 | 329/6588 | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.93, 1.04 | 329/6588 | 1.08e | 1.03, 1.13 | 1.06c | 1.01, 1.11 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||||||||||||

| No | 233/5223 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 240/5157 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 258/5742 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. |

| Yes | 96/1365 | 1.26 | 0.98, 1.61 | 1.07 | 0.82, 1.41 | 89/1431 | 1.09 | 0.85, 1.40 | 0.90 | 0.68, 1.19 | 71/846 | 1.42c | 1.08, 1.87 | 1.21 | 0.90, 1.63 |

| Pain in 2012–2013 (Mean follow-up = 6.2y, SD = 1.1) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain score | 233/6129 | 1.10d | 1.04, 1.16 | 1.08c | 1.02, 1.16 | 233/6129 | 1.05 | 0.99, 1.11 | 1.03 | 0.97, 1.09 | 233/6129 | 1.12e | 1.06, 1.17 | 1.11e | 1.05, 1.18 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||||||||||||

| No | 140/4751 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 149/4720 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 162/5224 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. |

| Yes | 93/1378 | 1.78e | 1.36, 2.35 | 1.72e | 1.28, 2.33 | 84/1409 | 1.51d | 1.14, 1.99 | 1.41c | 1.04, 1.92 | 71/905 | 1.88e | 1.40, 2.52 | 1.80e | 1.30, 2.49 |

| Pain in 2015–2016 (Mean follow-up = 3.2y, SD = 0.6) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain score | 100/5355 | 1.14d | 1.05, 1.24 | 1.12c | 1.02, 1.24 | 100/5355 | 1.07 | 0.99, 1.17 | 1.05 | 0.96, 1.15 | 100/5355 | 1.15e | 1.07, 1.24 | 1.15e | 1.06, 1.25 |

| Moderate to severe pain | |||||||||||||||

| No | 55/4082 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 61/4041 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 63/4521 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. |

| Yes | 45/1273 | 2.23e | 1.48, 3.36 | 2.17e | 1.40, 3.38 | 39/1314 | 1.72c | 1.13, 2.61 | 1.59c | 1.01, 2.50 | 37/834 | 2.62e | 1.71, 4.01 | 2.57e | 1.61, 4.09 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI confidence intervals.

Model 1: adjusted for age (as time scale), sex, birth cohort, education, ethnicity, and marital status.

Model 2: Model 1 + pain medication use, multimorbidity index, and depression assessed at the time of pain measurement.

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001

3.3. Pain trajectories over 27 years of follow-up

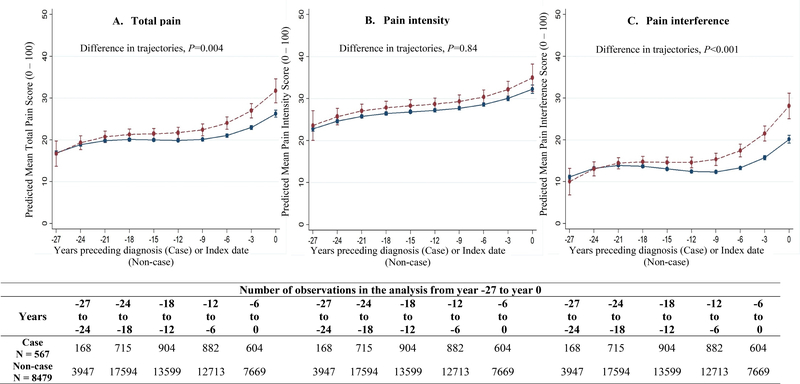

Pain trajectories over the 27-year follow-up differed between dementia cases and non-cases (Figure 1 for fully adjusted model, and Figure S4 for Model 1) as shown by significant interaction between dementia status and slope terms for total pain (Pinteraction=0.004) and pain interference (Pinteraction<0.001). In fully adjusted analyses (Model 2, Table 3; corresponding results for Model 1 in Table S3), dementia cases had higher total pain scores than non-cases starting 16 years before diagnosis (difference=1.4, 95%CI: 0.1, 2.7; P=0.04, corresponding to 7% of a SD of total pain score). Difference in pain score increased steadily to reach 5.5 (95%CI: 2.5, 8.4; P<0.001) at dementia diagnosis (year 0), corresponding to 28% of SD of the total pain score. These differences were driven primarily by the pain interference component, where differences between cases and non-cases began at year -16 and increased to reach 8.0 (95%CI: 4.8, 11.2; P<0.001) at dementia diagnosis (year 0). Differences in pain intensity were confined to the seven years before dementia diagnosis (Table 3). Analyses of 27-year trajectories of the probability of “moderate to severe” pain in fully adjusted analyses are shown in Figure S5, estimates shown in Table S4 in the supplement. The difference in estimated probability at 2.5% (95%CI: 0.1%, 4.8%; P=0.04) for total pain, 2.7% (95%CI: 0.0%, 5.5%; P=0.05) for pain intensity, and 1.9% (95%CI: 0.1%, 3.7%; P=0.03) for pain interference began at year -11, -6 and -12 years respectively. At dementia diagnosis these increased approximately 5 times for total pain and pain interference (Table S4).

Figure 1. Twenty-seven year trajectories of pain, using continuous measures, before dementia diagnosis.

Estimated from linear mixed models adjusted for age at Year 0, sex, education, ethnicity, marital status, dementia status, slope terms (time, time2, and time3), interaction of these covariates with slope terms, birth cohort, pain medication use, multi-morbidity index, and depression assessed at the time of pain measurement. Estimates came from Margins command in STATA.

Higher scores correspond to higher pain.

Table 3.

Differences in pain score between dementia cases and non-cases in the 27 years preceding dementia diagnosis in fully adjusted analysis.

| Years before index date | Total pain | Pain intensity | Pain interference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diff | 95% CI | P value | Diff | 95% CI | P value | Diff | 95% CI | P value | |

| −27 | −0.2 | −3.2, 2.9 | 0.90 | 0.8 | −2.8, 4.4 | 0.66 | −1.1 | −4.3, 2.1 | 0.51 |

| −26 | 0.1 | −2.4, 2.5 | 0.97 | 0.9 | −2.0, 3.8 | 0.53 | −0.7 | −3.3, 1.8 | 0.57 |

| −25 | 0.3 | −1.7, 2.3 | 0.79 | 1.0 | −1.3, 3.4 | 0.39 | −0.4 | −2.5, 1.6 | 0.69 |

| −24 | 0.5 | −1.2, 2.2 | 0.60 | 1.1 | −0.9, 3.1 | 0.27 | −0.1 | −1.9, 1.6 | 0.87 |

| −23 | 0.6 | −0.9, 2.2 | 0.42 | 1.2 | −0.6, 3.0 | 0.19 | 0.1 | −1.4, 1.6 | 0.90 |

| −22 | 0.8 | −0.7, 2.2 | 0.29 | 1.3 | −0.4, 3.0 | 0.15 | 0.3 | −1.1, 1.7 | 0.66 |

| −21 | 0.9 | −0.5, 2.3 | 0.21 | 1.3 | −0.3, 3.0 | 0.12 | 0.5 | −0.9, 1.9 | 0.46 |

| −20 | 1.0 | −0.4, 2.4 | 0.15 | 1.3 | −0.3, 3.0 | 0.11 | 0.7 | −0.7, 2.1 | 0.31 |

| −19 | 1.1 | −0.3, 2.5 | 0.11 | 1.4 | −0.2, 3.0 | 0.10 | 0.9 | −0.5, 2.3 | 0.21 |

| −18 | 1.2 | −0.1, 2.6 | 0.08 | 1.4 | −0.2, 3.0 | 0.09 | 1.1 | −0.3, 2.4 | 0.13 |

| −17 | 1.3 | −0.0, 2.7 | 0.06 | 1.4 | −0.1, 3.0 | 0.08 | 1.2 | −0.1, 2.6 | 0.07 |

| −16 | 1.4 | 0.1, 2.7 | 0.04 | 1.4 | −0.1, 2.9 | 0.07 | 1.4 | 0.1, 2.7 | 0.04 |

| −15 | 1.5 | 0.2, 2.8 | 0.02 | 1.4 | −0.1, 2.9 | 0.06 | 1.6 | 0.3, 2.9 | 0.02 |

| −14 | 1.6 | 0.3, 2.9 | 0.02 | 1.4 | −0.0, 2.9 | 0.06 | 1.8 | 0.5, 3.1 | 0.008 |

| −13 | 1.7 | 0.4, 3.0 | 0.01 | 1.5 | −0.0, 3.0 | 0.06 | 2.0 | 0.6, 3.3 | 0.004 |

| −12 | 1.8 | 0.5, 3.2 | 0.007 | 1.5 | −0.0, 3.0 | 0.06 | 2.2 | 0.8, 3.5 | 0.002 |

| −11 | 2.0 | 0.6, 3.3 | 0.005 | 1.5 | −0.1, 3.1 | 0.06 | 2.4 | 1.0, 3.8 | 0.001 |

| −10 | 2.1 | 0.7, 3.5 | 0.003 | 1.5 | −0.1, 3.1 | 0.06 | 2.7 | 1.3, 4.1 | <0.001 |

| −9 | 2.3 | 0.9, 3.8 | 0.002 | 1.6 | −0.1, 3.2 | 0.06 | 3.0 | 1.5, 4.5 | <0.001 |

| −8 | 2.5 | 1.0, 4.0 | 0.001 | 1.6 | 0.0, 3.3 | 0.06 | 3.3 | 1.8, 4.9 | <0.001 |

| −7 | 2.8 | 1.3, 4.3 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 0.0, 3.4 | 0.05 | 3.7 | 2.2, 5.3 | <0.001 |

| −6 | 3.0 | 1.5, 4.5 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.1, 3.5 | 0.04 | 4.2 | 2.6, 5.7 | <0.001 |

| −5 | 3.3 | 1.8, 4.9 | <0.001 | 1.9 | 0.1, 3.6 | 0.03 | 4.7 | 3.0, 6.3 | <0.001 |

| −4 | 3.7 | 2.0, 5.3 | <0.001 | 2.0 | 0.2, 3.8 | 0.03 | 5.2 | 3.5, 6.9 | <0.001 |

| −3 | 4.0 | 2.3, 5.8 | <0.001 | 2.1 | 0.2, 4.1 | 0.04 | 5.8 | 3.9, 7.6 | <0.001 |

| −2 | 4.5 | 2.4, 6.5 | <0.001 | 2.3 | 0.0, 4.6 | 0.05 | 6.5 | 4.3, 8.6 | <0.001 |

| −1 | 4.9 | 2.5, 7.4 | <0.001 | 2.5 | −0.3, 5.3 | 0.08 | 7.2 | 4.6, 9.8 | <0.001 |

| 0 | 5.5 | 2.5, 8.4 | <0.001 | 2.7 | −0.7, 6.1 | 0.12 | 8.0 | 4.8, 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Difference in trajectories | P=0.004 | P=0.84 | P<0.001 | ||||||

Abbreviations: Diff, difference; CI confidence intervals.

Estimates were extracted from linear-mixed models adjusted for age at Year 0, sex, education, ethnicity, marital status, dementia status, slope terms (time, time2, and time3), and interaction of these covariates with slope terms, birth cohort, pain medication use, multimorbidity index, and depression assessed at the time of pain measurement.

4. DISCUSSION

This longitudinal study with repeated pain measures collected over 27 years suggests steady progression in self-reported pain prior to dementia diagnosis. Time to event analysis, where data on pain measures over the course of the study were used to assess the impact of the length of follow-up on the association between pain and incident dementia, showed the association to be evident only when the mean follow-up was ten years or lower. The use of backward pain trajectories describes how small differences in pain scores between dementia cases and non-cases become increasingly pronounced in the decade before diagnosis of dementia. Taken together these results highlight the time dependent association between pain and dementia; given the long preclinical phase of dementia there is no strong evidence from our results that pain is a causal risk factor for dementia.

Several previous studies have examined the association between pain and cognitive outcomes, some [5,18,20–22,28–30] but not all studies [20,32] have suggested pain to be associated with impairment of cognitive domains such as attention, working memory, psychomotor speed and executive function. Whitlock et al reported faster 12-year memory decline and increase in dementia probability score among individuals with 2-year moderate to severe persistent pain [37]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies with a follow-up ranging 2.75 to 11.8 years found no association between persistent pain and incident cognitive decline/dementia, but, stratification of studies based on follow-up period revealed an association when follow-up was shorter than 4.5 years [1]. Cognitive decline has also been shown to affect pain perception [16], suggesting the need for closer attention to temporal framework in analysis of pain as a risk factor for dementia.

Pain [9] and chronic painful conditions such as fibromyalgia [27], osteoarthritis [36], head ache [33] have been found to be associated with risk of dementia. Few studies examine both the associations of pain intensity and pain interference, one such study with a four year mean follow-up found pain interference rather than intensity to be associated with dementia [9]. Other studies show pain interference, irrespective of the site [39] or nature of painful disease [15] to be associated with dementia risk. Our results also show pain interference rather than pain intensity to be the driver of observed associations between pain and dementia. Affective and cognitive domains of pain [13] are likely to determine subjective experience of pain interference [4]. These pain domains are affected early in dementia related neurodegeneration [23], underlying the emergence of pain interference in the pre-clinical phase of dementia. In agreement, the association between pain interference and incident dementia was observed earlier than the association between pain intensity and dementia in the present study. Nonetheless, the association needs to be interpreted with caution as limitations in daily activities, irrespective of pain, emerge in the decade preceding diagnosis [31]. Some authors suggest pain interference and limitations in daily activities as distinct domains [17], thus increase in pain interference and limitations in daily activities might be two different features observed in the dementia preclinical period.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the role of time in the association between pain and dementia. An important feature of this analysis is the construction of retrospective backward trajectories of pain spanning 27 years before dementia diagnosis allowing progressive change in pain to be tracked. Most previous studies used a mean follow-up of less than five years with pain assessed only at baseline, ignoring the time varying nature of pain. Our study, by combining findings from both backward trajectories and Cox regression models repeated at varying time points with mean follow-up ranging from three to 25 years permits a more comprehensive analysis of the timeline of the association between pain and dementia in its preclinical phase.

There are several possible explanations for the observed progression of pain before dementia diagnosis. One, pain could be a causal risk factor for dementia. Chronic pain induced chronic stress [14] via cortisol dysfunction [14] and neuroglial inflammation [14,20] can disrupt neuronal environment, accelerating neurodegenerative processes. However, differences in pain scores observed sixteen years before dementia diagnoses between dementia cases and non-cases in the backward trajectory models were negligible (around 1.4) when compared with the minimal clinically important difference of 4.9 suggested for rheumatoid arthritis [34]. Cox regression adjusted only for socio-demographic factors showed an association between pain interference and incidence of dementia but further adjustment for health conditions attenuated associations except when the time between pain measures and dementia diagnosis was ten years or less. These findings suggest that pain is not an independent, causal risk factor for dementia. Two, pain could be a preclinical symptom of dementia. Brain structures involved in motivational-affective and cognitive-evaluative pain processing are affected early in dementia related neurodegeneration [12,23], underpinning the longer-term association between pain interference and dementia. Three, pain and dementia may have common causes as both share pathophysiological mechanisms within the brain [3].

Limitations of the present study include lack of data on the characteristics, type, and location of pain. The specific chronic conditions that contributed to the association between pain and dementia could not be examined in sufficient detail. Our multi-morbidity index included a range of conditions to reflect overall disease burden, it is possible that some of these play a more important role than others. Finally, as dementia diagnosis was based on electronic health records we did not have complete information on type or severity of dementia. This method might miss milder dementia but it has the advantage of providing data on dementia for all participants recruited to the study rather than those who consent to face-to-face assessment of dementia status over the follow-up.

5. CONCLUSION

Dementia is a major challenge for social and health care due to aging of populations, highlighting the need to better understand the course of dementia, associated symptoms, and risk factors for effective preventive strategies. We found pain to increase rapidly in the preclinical period of dementia such that association of pain with dementia became stronger when assessed closer in time to dementia diagnosis. These findings suggest that pain is a prodromal symptom of dementia or both share common causal mechanisms rather than an important contributor to risk of dementia. Between pain intensity and pain interference, it was the latter that had a stronger association with dementia highlighting the need for better management of pain in older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants from civil service departments and their welfare, personnel, and establishment officers and all members of the Whitehall II study teams.

Funding: The Whitehall II study has been supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, NIH (R01AG056477, RF1AG062553); UK Medical Research Council (R024227, S011676); the British Heart Foundation (RG/16/11/32334). Mika Kivimaki is supported by the Medical Research Council (K013351, R024227, S011676), UK, NordForsk, the Academy of Finland (311492) and Helsinki Institute of Life Science. Séverine Sabia is supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-19-CE36-0004-01).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest disclosures: None reported.

Data Sharing: Whitehall II data, protocols, and other metadata are available to the scientific community. Please refer to the Whitehall II data sharing policy at https://www.ucl.ac.uk/epidemiology-health-care/research/epidemiology-and-public-health/research/whitehall-ii/data-sharing.

Ethical approval: NHS London - Harrow Research Ethics Committee, reference number 85/0938.

References

- [1].Aguiar GP, Saraiva MD, Khazaal EJB, de Andrade DC, Jacob-Filho W, Suemoto CK. Persistent pain and cognitive decline in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis from longitudinal studies. Pain 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Apkarian AV, Hashmi JA, Baliki MN. Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain 2011;152(3 Suppl):S49–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Apkarian AV, Scholz J. Shared mechanisms between chronic pain and neurodegenerative disease. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Mechanisms 2006;3(3):319–326. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Auvray M, Myin E, Spence C. The sensory-discriminative and affective-motivational aspects of pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;34(2):214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Berryman C, Stanton TR, Jane Bowering K, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Lorimer Moseley G. Evidence for working memory deficits in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2013;154(8):1181–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bushnell MC, Case LK, Ceko M, Cotton VA, Gracely JL, Low LA, Pitcher MH, Villemure C. Effect of environment on the long-term consequences of chronic pain. Pain 2015;156 Suppl 1:S42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cauda F, Palermo S, Costa T, Torta R, Duca S, Vercelli U, Geminiani G, Torta DM. Gray matter alterations in chronic pain: A network-oriented meta-analytic approach. Neuroimage Clin 2014;4:676–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].de Tommaso M, Arendt-Nielsen L, Defrin R, Kunz M, Pickering G, Valeriani M. Pain in Neurodegenerative Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Behav Neurol 2016;2016:7576292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ezzati A, Wang C, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Zammit AR, Zimmerman ME, Pavlovic JM, Sliwinski MJ, Lipton RB. The Temporal Relationship between Pain Intensity and Pain Interference and Incident Dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res 2019;16(2):109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fine PG. Long-term consequences of chronic pain: mounting evidence for pain as a neurological disease and parallels with other chronic disease states. Pain Med 2011;12(7):996–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fritz HC, McAuley JH, Wittfeld K, Hegenscheid K, Schmidt CO, Langner S, Lotze M. Chronic Back Pain Is Associated With Decreased Prefrontal and Anterior Insular Gray Matter: Results From a Population-Based Cohort Study. J Pain 2016;17(1):111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gagliese L, Gauthier LR, Narain N, Freedman T. Pain, aging and dementia: Towards a biopsychosocial model. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2018;87(Pt B):207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R. Pain matrices and neuropathic pain matrices: a review. Pain 2013;154 Suppl 1:S29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther 2014;94(12):1816–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ikram M, Innes K, Sambamoorthi U. Association of osteoarthritis and pain with Alzheimer's Diseases and Related Dementias among older adults in the United States. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27(10):1470–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].James RJE, Ferguson E. The dynamic relationship between pain, depression and cognitive function in a sample of newly diagnosed arthritic adults: a cross-lagged panel model. Psychol Med 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Karayannis NV, Sturgeon JA, Chih-Kao M, Cooley C, Mackey SC. Pain interference and physical function demonstrate poor longitudinal association in people living with pain: a PROMIS investigation. Pain 2017;158(6):1063–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lee DM, Pendleton N, Tajar A, O'Neill TW, O'Connor DB, Bartfai G, Boonen S, Casanueva FF, Finn JD, Forti G, Giwercman A, Han TS, Huhtaniemi IT, Kula K, Lean ME, Punab M, Silman AJ, Vanderschueren D, Moseley CM, Wu FC, McBeth J, Group ES. Chronic widespread pain is associated with slower cognitive processing speed in middle-aged and older European men. Pain 2010;151(1):30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Melzack R, Katz J. Pain. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 2013;4(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moriarty O, McGuire BE, Finn DP. The effect of pain on cognitive function: a review of clinical and preclinical research. Prog Neurobiol 2011;93(3):385–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Murata S, Nakakubo S, Isa T, Tsuboi Y, Torizawa K, Fukuta A, Okumura M, Matsuda N, Ono R. Effect of Pain Severity on Executive Function Decline in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2018;4:2333721418811490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Murata S, Sawa R, Nakatsu N, Saito T, Sugimoto T, Nakamura R, Misu S, Ueda Y, Ono R. Association between chronic musculoskeletal pain and executive function in community-dwelling older adults. Eur J Pain 2017;21(10):1717–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Scherder EJ, Sergeant JA, Swaab DF. Pain processing in dementia and its relation to neuropathology. Lancet Neurol 2003;2(11):677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Silverberg N, Elliott C, Ryan L, Masliah E, Hodes R. NIA commentary on the NIA-AA Research Framework: Towards a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14(4):576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Smallwood RF, Laird AR, Ramage AE, Parkinson AL, Lewis J, Clauw DJ, Williams DA, Schmidt-Wilcke T, Farrell MJ, Eickhoff SB, Robin DA. Structural brain anomalies and chronic pain: a quantitative meta-analysis of gray matter volume. J Pain 2013;14(7):663–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sommerlad A, Perera G, Singh-Manoux A, Lewis G, Stewart R, Livingston G. Accuracy of general hospital dementia diagnoses in England: Sensitivity, specificity, and predictors of diagnostic accuracy 2008–2016. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14(7):933–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Liu FC, Chiu YH, Chang HA, Yeh CB, Huang SY, Lu RB, Yeh HW, Kao YC, Chiang WS, Tsao CH, Wu YF, Chou YC, Lin FH, Chien WC. Fibromyalgia and Risk of Dementia-A Nationwide, Population-Based, Cohort Study. Am J Med Sci 2018;355(2):153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van der Leeuw G, Ayers E, Blankenstein AH, van der Horst HE, Verghese J. The association between pain and prevalent and incident motoric cognitive risk syndrome in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019;87:103991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].van der Leeuw G, Ayers E, Leveille SG, Blankenstein AH, van der Horst HE, Verghese J. The Effect of Pain on Major Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. J Pain 2018;19(12):1435–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].van der Leeuw G, Eggermont LH, Shi L, Milberg WP, Gross AL, Hausdorff JM, Bean JF, Leveille SG. Pain and Cognitive Function Among Older Adults Living in the Community. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71(3):398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Verlinden VJA, van der Geest JN, de Bruijn R, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Ikram MA. Trajectories of decline in cognition and daily functioning in preclinical dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12(2):144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Veronese N, Koyanagi A, Solmi M, Thompson T, Maggi S, Schofield P, Mueller C, Gale CR, Cooper C, Stubbs B. Pain is not associated with cognitive decline in older adults: A four-year longitudinal study. Maturitas 2018;115:92–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang J, Xu W, Sun S, Yu S, Fan L. Headache disorder and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Headache Pain 2018;19(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ward MM, Guthrie LC, Alba MI. Clinically important changes in short form 36 health survey scales for use in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials: the impact of low responsiveness. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(12):1783–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide, Vol. 30: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center. Boston, Massachusetts: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Weber A, Mak SH, Berenbaum F, Sellam J, Zheng YP, Han Y, Wen C. Association between osteoarthritis and increased risk of dementia: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(10):e14355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Whitlock EL, Diaz-Ramirez LG, Glymour MM, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE, Smith AK. Association Between Persistent Pain and Memory Decline and Dementia in a Longitudinal Cohort of Elders. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(8):1146–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, Rannikmae K, Bush K, Brayne C, Quinn TJ, Sudlow CLM, Group UKBNO, Dementias Platform UK. Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14(8):1038–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yamada K, Kubota Y, Tabuchi T, Shirai K, Iso H, Kondo N, Kondo K. A prospective study of knee pain, low back pain, and risk of dementia: the JAGES project. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.