Abstract

Unfolded protein response (UPR) suppression by Kifunensine has been associated with lung hyperpermeability, the hallmark of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The present study investigates the effects of the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor Luminespib (AUY-922) towards the Kifunensine-triggered lung endothelial dysfunction. Our results indicate that the UPR inducer Luminespib counteracts the effects of Kifunensine in both human and bovine lung endothelial cells. Hence, we suggest that UPR manipulation may serve as a promising therapeutic strategy against potentially lethal respiratory disorders, including the ARDS related to COVID-19.

Keywords: P53, endothelium, inflammation, acute lung injury

Introduction

The pulmonary vasculature forms a continuous monolayer of endothelial cells to act as a semi-permeable barrier to control the extravasation of blood fluid, electrolytes, proteins and leucocytes. Dysregulation of lung endothelial barrier function due to lung inflammation has been associated with hyperpermeability responses across the endothelial and epithelial barriers. Such events contribute to the development of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1]. Patients hospitalized due to severe ARDS are subjected to mechanical ventilation and the risk of death in such instances may rise up to 45%, especially in the elderly. Hence, the development of novel therapeutic strategies towards the enhancement of lung endothelial barrier may deliver novel therapeutic possibilities in ARDS, including the ARDS related to COVID-19 [2].

Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a highly abundant molecular chaperone, essential for many fundamental processes including cell signaling, proliferation, differentiation, and survival [3, 4]. It is required for the folding, stability, and maturation of various client proteins (e.g. kinases, transcription factors, steroid hormone receptors) which are involved and propel inflammatory processes. Moreover, inflammatory stimuli (e.g. LPS) have been shown to activate (phosphorylate) Hsp90 [5, 6]. On the other hand, Hsp90 inhibition by the corresponding compounds (Hsp90 inhibitors) delivers an exciting possibility towards inflammatory conditions, including cancers [7]. An emerging body of evidence indicates that Hsp90 inhibitors oppose cancer and inflammation [8]. In experimental models of ALI/ARDS, Hsp90 inhibition counteracts lung endothelial hyperpermeability by remodeling the actin cytoskeleton [9, 10].

Those effects involve the endothelial defender and tumor suppressor P53, which senses threats to devise cellular responses [11, 12]. The mild induction of this 53 kDa protein exerts anti-inflammatory effects in the lungs, linked to the decrease of the reactive oxygen species production [13]. We have shown that Hsp90 inhibitors suppress the LPS-induced P53 phosphorylation, protecting this transcription factor against degradation [14]. Moreover, those anti-cancer compounds stabilize P53 by reducing both in vivo and in vitro MDM2 and MDM4 (P53 suppressors) [15].

The unfolded protein response (UPR) affects P53 in a positive manner [16]. This is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-based mechanism; which organizes cellular repairing processes [17]. The protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and the inositol-requiring enzyme-1α (IRE1α) are the major elements of that mechanism, which bind to the immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP) [18]. Increased ER stress disassociates BiP from the previously mentioned UPR components, leading to their activation [19]. Interestingly, the Hsp90 inhibitors, 17-AAG, 17- DMAG, and AUY-922 induce UPR in both bovine and human lung endothelial cells, as well as in lungs from mice[20, 21]. Moreover, the α-mannosidases inhibitor and UPR suppressor Kifunensine (KIF) disrupted the lung endothelial barrier integrity, as reflected in measurements of transendothelial resistance (TEER) and key mediators of the vascular permeability [22]. In the current study, we employed the UPR suppressor (KIF) and the Hsp90 inhibitor (Luminespib) to investigate Hsp90 inhibition supports against the Kifunensine-induced lung endothelial barrier dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Kifunensine (IC15995201), Luminespib (AUY-922) (101756–820), anti-mouse IgG HRP linked whole antibody from sheep (95017–554), anti-rabbit IgG HRP linked whole antibody from donkey (95017–556) and nitrocellulose membranes (10063–173), radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (AAJ63306-AP), as well as 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (BT142015–5G) were obtained from VWR (Radnor, PA). Phospho-cofilin (3313S), Cofilin (3318S), phospho-myosin Light Chain 2 (3674S), myosin Light Chain 2 (3672S) and P53 (9282S) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The β-actin antibody (A5441) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Cell culture

Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (BPAEC) (PB30205) were purchased from Genlantis (San Diego, CA) as well as human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HuLEC–5a) (CRL–3244) from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Bovine cells were cultured in DMEM medium (VWRL0101–0500) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (89510–186), and the human cells in PromoCell endothelial cell growth medium MV (10172–280). Those media were supplemented with 1X penicillin/streptomycin (97063–708) and cells were maintained at 37 °C, in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air. All reagents were purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA).

Measurement of Cell Viability

BPAECs were seeded in 96-well culture plates (10,000 cells/well) in complete growth media and were treated with KIF (0.01–200 μM) and AUY-922 (0.01–200 μM). After 24 hours, media was replaced with serum-free media containing 0.5 mg/ml 3-(4, 5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). After 3 hours of incubation, DMSO (100 μl/well) was added to dissolve MTT crystals and 15 minutes later absorbance was measured at 570 nm on Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Reader from Biotek (Winooski, VT).

Measurement of endothelial barrier function

The barrier function of endothelial cell monolayers grown on electrode arrays (8W10E+) was estimated by electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS), utilizing ECIS model ZΘ (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY, USA). All experiments were conducted on wells which had reached a steady-state resistance of at least 800 Ω [23].

Western blot analysis

RIPA buffer and the EZBlock™ protease inhibitor cocktail were used to isolate the proteins from the cells. Protein-matched samples were separated according to their molecular weight by electrophoresis onto 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate Tris-HCl gels. Then, we employed a wet transfer technique to transfer the proteins onto the nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were exposed for at least 60 minutes at room temperature in a solution of 5% non-fat dry milk. After incubating, the blots were exposed overnight (4 °C) to appropriate primary antibodies (1:1000). The following day, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies (1:2000) to develop the signal for immunoreactive proteins. Protein signal was detected using chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific). All the images were captured using ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The β-actin was used as a loading control unless indicated otherwise. All reagents were purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA).

Densitometry and statistical analysis

Image J software (National Institute of Health) was used to perform densitometry of immunoblots. All data are expressed as mean values ±SEM (standard error of mean). Student’s t-test was performed to determine statistically significant differences among groups. A value of P <0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism (version 5.01) was used to analyze the data. The letter n represents the number of experimental repeats.

Results

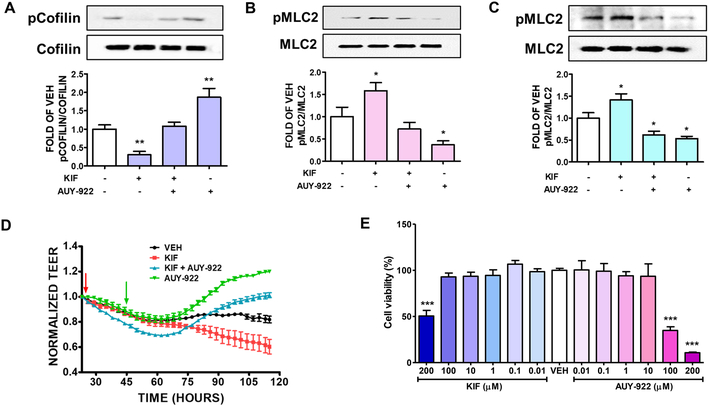

Hsp90 inhibitor luminespib (AUY-922) suppressed the KIF-induced activation of cofilin in BPAEC

Bovine lung cells were grown in six well plates. Confluent cells were pretreated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO), or 5 μM of KIF for 24 hours. After 16 hours of post-treatment with AUY-922, we investigated the effects of those treatments in the phosphorylation of Cofilin (pCofilin). As shown in Fig. 1A, UPR suppression decreased the phosphorylated cofilin and luminespib opposed that effect.

Figure 1: Effects of KIF and AUY-922 on lung endothelial cells.

Western Blot analysis of (A) phosphorylated Cofilin (pCofilin) and Cofilin (B) phosphorylated MLC2 (pMLC2) and MLC2 after 24 hours treatment of BPAEC with either KIF (5 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) and post-treatment with AUY-922 (2 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 16 hours. The blots shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. The signal intensity of the bands was analyzed by densitometry. Protein levels of pCofilin and pMLC2 were normalized to Cofilin and MLC2 respectively. *P < 0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle. Means ± SEM. Western Blot analysis of (C) phosphorylated MLC2 (pMLC2) and MLC2 after 24 hours treatment of HuLEC with either KIF (5 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO); and post-treatment with AUY-922 (2 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 16 hours. The blots shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. The signal intensity of the pMLC2 was analyzed by densitometry. Protein levels of pMLC2 were normalized to MLC2. *P<0.05 vs vehicle. Means ± SEM. (D) Confluent monolayers of BPAEC were pre-treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (25 μM) (red arrow) for 18 hours, followed by treatment with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 5 μM of AUY-922 (green arrow). A gradual increase in endothelial permeability (reduced TEER) was observed in KIF treated cells (red line). AUY-922 significantly reduced the endothelial permeability (increased TEER) in both KIF-pretreated (blue line) and vehicle-treated cells (green line). (E) Cells were incubated with either VEH (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 200 μM) or AUY-922 (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 200 μM) for 24 hours. Cellular viability was evaluated by employing the MTT assay. ***P<0.001 vs VEH, n=3. Means ± SEM.

Luminespib suppressed the KIF-induced phosphorylation of MLC2 in BPAEC

BPAEC were pretreated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or the UPR suppressor KIF (5μM) for 24 hours, followed by treatment with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or luminespib (2μM). After 16 hours of AUY-922 exposure, we investigated the effects of UPR suppression in the phosphorylation of myosin light chain 2. Our results suggest that KIF significantly induces the phosphorylated MLC2 (pMLC2) level and the Hsp90 inhibitor luminespib downregulated that MLC2 phosphorylation in both vehicle-treated and KIF-treated cells (Fig. 1B).

Luminespib suppressed the KIF-induced phosphorylation of MLC2 in HuLEC-5a

Human lung endothelial cells were exposed to either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (5μM). After 24 hours of KIF exposure, the cells were treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or luminespib (2μM) for 16 hours. Western blot analysis was performed on cell lysates to measure protein levels. The densitometry analysis of the immunoblots revealed that KIF significantly induces the phosphorylation of MLC2 (pMLC2), while AUY-922 remarkably reduces the activation of MLC2 in both the vehicle-treated and KIF-treated human lung endothelial cells (Fig. 1C).

Luminespib protects against the KIF-induced endothelial barrier hyperpermeability in BPAEC

We employed the electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) model to evaluate the lung endothelial barrier function. BPAEC were seeded onto the gold electrode arrays and left to reach steady transendothelial values, an indicator of the monolayer formation. The cells were treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (25 μM) for 18 hours prior to treatment with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or AUY-922 (5 μM). Treatment with KIF to the lung cells exerted decreased TEER values (increased permeability). Luminespib (5 μM) post-treatment prevented the Kifunensine-triggered hyperpermeability, as reflected in the increased TEER values (Fig. 1D).

Effects of KIF and luminespib (AUY-922) in cellular viability

BPAECs were seeded on 96-well plate (10,000 cells in each well) and treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (0.01–200 μM) or AUY-922 (0.01–200 μM) for 24 hours. Our results suggest that moderate concentrations of KIF (0.01–100 μΜ) and luminespib (0.01–10 μΜ) do not exhibit toxicity to bovine lung endothelial cells (Fig. 1E). However, cells exposed to higher concentrations of KIF (200 μΜ) and AUY-922 (100 and 200 μΜ) demonstrated significant reduction in their cellular viability.

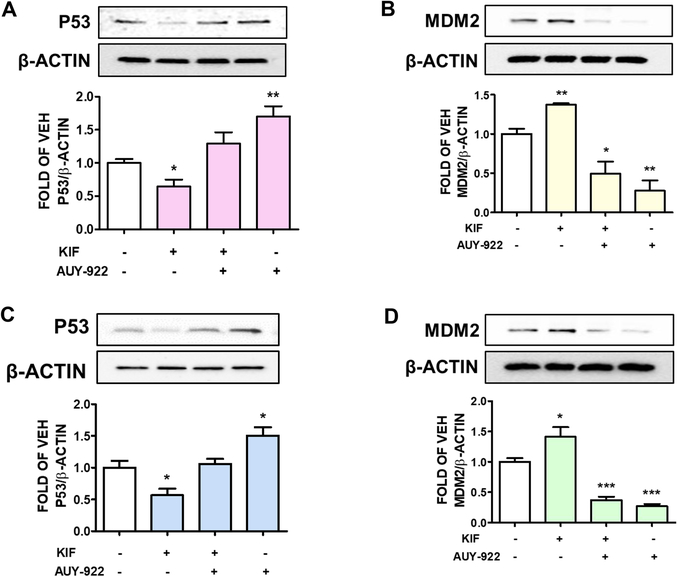

Luminespib (AUY-922) inhibits the KIF-induced suppression of P53 in BPAEC

To investigate the supportive effects of AUY-922 against KIF-induced hyperpermeability in BPAEC, we pretreated BPAEC with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (5μM) for 24 hours. The cells were post-treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or AUY-922 (2μM). After 16 hours of AUY-922 post-treatment, western blot analysis was performed to detect P53 expression levels. KIF significantly reduced P53 abundance, while luminespib inhibited that effect. Moreover, this Hsp90 inhibitor significantly induced P53 levels (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2: Effects of KIF and AUY-922 on P53 regulation.

Western Bot analysis of (A) P53 and β-actin, (B) MDM2 and β-actin expression after 24 hours treatment of BPAEC with either KIF (5 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO); and post-treatment with AUY-922 (2 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 16 hours. The blots shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. The signal intensity of P53 and MDM2 was analyzed by densitometry, and the protein levels were normalized to β-actin. *P < 0.05, **P<0.01 vs vehicle. Means ± SEM. Western Bot analysis of (C) P53 and β-actin, (D) MDM2 and β-actin expression after 24 hours treatment of HuLEC-5a with either KIF (5 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) and post-treatment with AUY-922 (2 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 16 hours. The blots shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Signal intensity of P53 and MDM2 was analyzed by densitometry. Protein levels were normalized to β-actin. *P < 0.05, ***<0.001 vs vehicle. Means ± SEM.

Luminespib (AUY-922) reduces the KIF-triggered induction of MDM2 in BPAEC

BPAEC were exposed to either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (5μM) for 24 hours. After that treatment, the cells were treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 2μM of luminespib for 16 hours. The KIF-treated cells exhibited higher levels of MDM2, while AUY-922 reversed that effect (Fig. 2B).

Luminespib (AUY-922) inhibits KIF-induced suppression of P53 in HuLEC-5a

Human lung endothelial cells were pretreated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (5μM) for 24 hours, followed by treatment with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or 2μM of AUY-922. After 16 hours of AUY-922 exposure, we performed densitometric analysis in the immunoblots. Fig. 2C shows that KIF significantly reduces P53 expression, while luminespib prevents that effect in both vehicle-treated and KIF-treated cells.

Luminespib (AUY-922) prevents KIF-mediated induction of MDM2 in HuLEC-5a

HuLEC-5a were pretreated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or KIF (5μM). After 24 hours of KIF exposure, the cells were treated with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or luminespib (2μM) for 16 hours. KIF promoted the induction of the P53 inhibitor MDM2, and AUY-922 significantly counteracted that effect (Fig. 2D).

Discussion

Investigating the molecular mechanisms involved in the mediation of the anti-inflammatory activities of the Hsp90 inhibitors in the vasculature expands our knowledge on the regulation of the lung endothelial barrier function. C-terminal domain-based Hsp90 inhibitors protect against the bacteria-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction [24, 25]. In the current work, we evaluated the effects of UPR manipulation towards the lung endothelial permeability. We employed the Hsp90 inhibitor AUY-922 (UPR inducer), as well as the UPR suppressor Kifunensine (a selective inhibitor of class 1 α-mannosidases) to evaluate their effects toward lung endothelial permeability. Luminespib represents an advanced stage in the development of Hsp90 inhibitors. It has been associated with minimum side effects, and has advanced to Phase II of clinical trials to fight cancer [26].

In our study, Luminespib opposed the KIF-induced phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC2) in both bovine and human lung endothelial cells (Fig. 1 B, C). Myosin light chain kinases (MLCKs) are a family of Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinases involved in the regulation of microvascular permeability. The function of MLCK is to phosphorylate the regulatory MLC2, which produces F-actin. The posttranslational modification of MLC is a fundamental molecular cascade towards the regulation of lung endothelial barrier integrity [27]. The pMLC2 triggers the ATP-dependent actomyosin contraction to potentiate endothelial cell membrane retraction, intercellular gap formation, and vascular barrier disruption [28].

Luminespib deactivates Cofilin, which is a small (19-kDa) ubiquitous actin-binding protein associated with the regulation of cell protrusions [29]. Phosphorylated cofilin does not bind to the actin, thus Cofilin is deactivated by phosphorylation to support lung endothelial barrier integrity. Plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is also associated with the cortical actin formation by inhibiting Cofilin [30]. In intestinal epithelial cells, hypoxia initiates the activation of Cofilin, which in turn increases endothelial permeability, as reflected in the decreased TEER measurements. Those values reflect changes in endothelial and epithelial permeability [31]. Similar reductions have been observed in models of ALI, indicating the disruption of tight junction proteins [32, 33].

KIF has been shown to activate Cofilin by dephosphorylation [22]. In the present study the Hsp90 inhibitor AUY-922 counteracted those events. It was also demonstrated that a mild UPR induction due to Hsp90 inhibition induces key players in the mediation of the UPR signaling, including the BiP, endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin-1 alpha (ERO1-Lα), and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) [17]. The importance of UPR in mediating normal respiratory functions is underlined by the fact that knock-in mice expressing a mutant BiP protein suffered from respiratory dysfunction due to abnormal secretion of lung surfactant by the alveolar type II epithelial cells [19, 34].

UPR is also essential for ER homeostasis during growth [19, 35]. IRE1α increased the level of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, while PERK exerted the opposite effects [36]. In another study, PERK knock-out (KO) mice were used to examine the effects of transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced lung fibrosis and lung vascular remodeling. Chronic TAC initiated the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and exacerbated lung remodeling in the mutant mice. UPR affects P53 expression levels, since UPR induction elevates P53 levels, while UPR suppressors reduce them [16].

P53 is a transcription factor essential for the regulation of vascular integrity, and involved in the lung function. Moreover, it exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κΒ)[37]. Mycoplasma infection activates NF-κΒ via P53 suppression, thus contributing to the development of tumors [38]. Moreover, P53 suppresses NF-κΒ by repressing the glucocorticoid receptor [39]. It was also shown that the induction of P53 protects against the lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-triggered endothelial barrier dysfunction [10]. In another study, the expression levels of major pro-inflammatory mediators were more prominent in P53 KO mice than the wild type counteracts due to LPS treatment [40, 41]. LPS was shown to downregulate P53 expression via the induction of MDM2. Indeed, P53 mediates the protective effects of Hsp90 inhibition by modulating the RhoA/MLC2 pathway [42], thus reducing the formation of the F-actin fibers [15]. In the present effort, we show that Hsp90 inhibition by AUY-922 counteracts the Kifunensine-induced P53 suppression by suppressing MDM2.

Our study demonstrates for the first time that the deteriorating effects of the UPR suppressor Kifunensine in lung endothelial cells are counteracted by the UPR inducer AUY-922. Thus, we suggest that UPR manipulation may serve as a promising therapeutic strategy towards lung disease, including the COVID-19 related ARDS. Future studies will follow to investigate the exact UPR branches involved in those phenomena, by employing advanced models of genetically modified mice. Those mutants will not express the inositol-requiring enzyme-1α (IRE1α), or the protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) and activating transcription factor 6α (ATF6α).

Highlights.

The Hsp90 inhibitor Luminespib induces lung endothelial barrier function.

Luminespib induces the unfolded protein response.

Kifunensine compromises vascular barrier function.

Kifunensine suppresses the unfolded protein response.

Luminespib counteracts the Kifunensin-induced lung endothelial barrier dysfunction

Acknowledgments

Funding: Our research is supported by the 1) R&D, Research Competitiveness Subprogram (RCS) of the Louisiana Board of Regents through the Board of Regents Support Fund (LEQSF(2019-22)-RD-A-26) (PI: NB) 2) Faculty Research Support Program from Dean’s Office, College of Pharmacy, ULM (PI: NB) and 3) NIGMS/NIH (5 P20GM103424-15, 3 P20 GM103424-15S1)

Footnotes

Disclosure: No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

The authors declare no conflict of interests

Not provided.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Good RJ, et al. , MicroRNA dysregulation in lung injury: the role of the miR-26a/EphA2 axis in regulation of endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2018. 315(4): p. L584–L594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres Acosta MA and Singer BD, Pathogenesis of COVID-19-induced ARDS: implications for an aging population. Eur Respir J, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scieglinska D, et al. , Heat shock proteins in the physiology and pathophysiology of epidermal keratinocytes. Cell Stress Chaperones, 2019. 24(6): p. 1027–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barabutis N, Heat shock protein 90 inhibition in the inflamed lungs. Cell Stress Chaperones, 2020. 25(2): p. 195–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbasi M, et al. , New heat shock protein (Hsp90) inhibitors, designed by pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening: synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular dynamics studies. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 2020. 38(12): p. 3462–3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barabutis N, et al. , LPS induces pp60c-src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Hsp90 in lung vascular endothelial cells and mouse lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2013. 304(12): p. L883–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barabutis N and Siejka A, The highly interrelated GHRH, p53, and Hsp90 universe. Cell Biol Int, 2020. 44(8): p. 1558–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barabutis N, Schally AV, and Siejka A, P53, GHRH, inflammation and cancer. EBioMedicine, 2018. 37: p. 557–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barabutis N, et al. , Wild-type p53 enhances endothelial barrier function by mediating RAC1 signalling and RhoA inhibition. J Cell Mol Med, 2018. 22(3): p. 1792–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barabutis N, P53 in lung vascular barrier dysfunction. Vasc Biol, 2020. 2(1): p. E1–E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller L, et al. , Hsp90 regulates the activity of wild type p53 under physiological and elevated temperatures. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(47): p. 48846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubra KT, et al. , P53 versus inflammation: an update. Cell Cycle, 2020. 19(2): p. 160–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhter MS, Uddin MA, and Barabutis N, P53 Regulates the Redox Status of Lung Endothelial Cells. Inflammation, 2020. 43(2): p. 686–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barabutis N, Uddin MA, and Catravas JD, Hsp90 inhibitors suppress P53 phosphorylation in LPS - induced endothelial inflammation. Cytokine, 2019. 113: p. 427–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barabutis N, et al. , p53 protects against LPS-induced lung endothelial barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015. 308(8): p. L776–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akhter MS, Uddin MA, and Barabutis N, Unfolded protein response regulates P53 expression in the pulmonary endothelium. J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2019. 33(10): p. e22380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barabutis N, Unfolded Protein Response in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Lung, 2019. 197(6): p. 827–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barabutis N, Unfolded Protein Response supports endothelial barrier function. Biochimie, 2019. 165: p. 206–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubra KT, et al. , Unfolded protein response in cardiovascular disease. Cell Signal, 2020. 73: p. 109699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uddin MA, et al. , Effects of Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibition In the Lungs. Med Drug Discov, 2020. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubra KT, et al. , Hsp90 inhibitors induce the unfolded protein response in bovine and mice lung cells. Cell Signal, 2020. 67: p. 109500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhter MS, et al. , Kifunensine compromises lung endothelial barrier function. Microvasc Res, 2020. 132: p. 104051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uddin MA, et al. , P53 supports endothelial barrier function via APE1/Ref1 suppression. Immunobiology, 2019. 224(4): p. 532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi AD, et al. , Heat shock protein 90 inhibitors prevent LPS-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction by disrupting RhoA signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2014. 50(1): p. 170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solopov P, et al. , The HSP90 Inhibitor, AUY-922, Ameliorates the Development of Nitrogen Mustard-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Dysfunction in Mice. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felip E, et al. , Phase 2 Study of the HSP-90 Inhibitor AUY922 in Previously Treated and Molecularly Defined Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol, 2018. 13(4): p. 576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rigor RR, et al. , Myosin light chain kinase signaling in endothelial barrier dysfunction. Med Res Rev, 2013. 33(5): p. 911–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen Q, et al. , Myosin light chain kinase in microvascular endothelial barrier function. Cardiovasc Res, 2010. 87(2): p. 272–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uddin MA, et al. , GHRH antagonists support lung endothelial barrier function. Tissue Barriers, 2019. 7(4): p. 1669989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belvitch P, et al. , Cortical Actin Dynamics in Endothelial Permeability. Curr Top Membr, 2018. 82: p. 141–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song H, et al. , Activation of Cofilin Increases Intestinal Permeability via Depolymerization of F-Actin During Hypoxia in vitro. Front Physiol, 2019. 10: p. 1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birukova AA, et al. , Prostacyclin post-treatment improves LPS-induced acute lung injury and endothelial barrier recovery via Rap1. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2015. 1852(5): p. 778–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovacs-Kasa A, et al. , Extracellular adenosine-induced Rac1 activation in pulmonary endothelium: Molecular mechanisms and barrier-protective role. J Cell Physiol, 2018. 233(8): p. 5736–5746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barabutis N, Unfolded Protein Response in Lung Health and Disease. Front Med (Lausanne), 2020. 7: p. 344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barabutis N, Unfolded protein response in lung health and disease. frontiers in medicine, 2020. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen WY, et al. , Genotype 2 Strains of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus Dysregulate Alveolar Macrophage Cytokine Production via the Unfolded Protein Response. J Virol, 2018. 92(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uddin MA and Barabutis N, P53 in the impaired lungs. DNA Repair (Amst), 2020. 95: p. 102952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gudkov AV and Komarova EA, p53 and the Carcinogenicity of Chronic Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2016. 6(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy SH, et al. , Tumor suppressor protein (p)53, is a regulator of NF-kappaB repression by the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(41): p. 17117–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu G, et al. , p53 Attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation and acute lung injury. J Immunol, 2009. 182(8): p. 5063–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uddin MA, et al. , P53 deficiency potentiates LPS-Induced acute lung injury in vivo. Curr Res Physiol, 2020. 3: p. 30–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barabutis N, P53 in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]