Introduction

There is an increasing appreciation for the role of secreted extracellular vesicles (EVs) and non-vesicular nanoparticles in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Small EVs (sEVs) are 40–200 nm lipid-bilayer enclosed membrane vesicles while exomeres are small (< 50 nm), non-membranous, extracellular nanoparticles.1,2 The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic is caused by the recent emergence of SARS-CoV-2.3 For infection, SARS-CoV-2 must bind to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to gain entry.4 ACE2 is also the critical receptor used by SARS-CoV-1, responsible for the 2002–2004 SARS epidemic. Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a highly lethal respiratory disease initiated by binding of MERS-CoV to its entry receptor dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4).5 ACE2 and DPP4 are highly expressed in gastrointestinal tissues, and a significant number of COVID-19, SARS and MERS patients present with gastrointestinal symptoms.6,7 The ectodomain of ACE2 can be released by the activity of the metalloprotease TACE and the serine protease TMPRSS2.4 The S1 subunit of the spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 is primed by the transmembrane serine proteases TMPRSS2 or TMPRSS4 for cell entry4,7, and TMPRSS2 can also prime the S protein of MERS-CoV. It has been demonstrated that human recombinant soluble ACE2, but not mouse ACE2, can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection8, raising the possibility extracellular ACE2 carried by EVs or extracellular nanoparticles may act as a decoy to bind the virus. Here, we explore the hypothesis that sEVs and exomeres containing ACE2 can bind SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Detailed methods are available in the Supplementary Methods.

Results

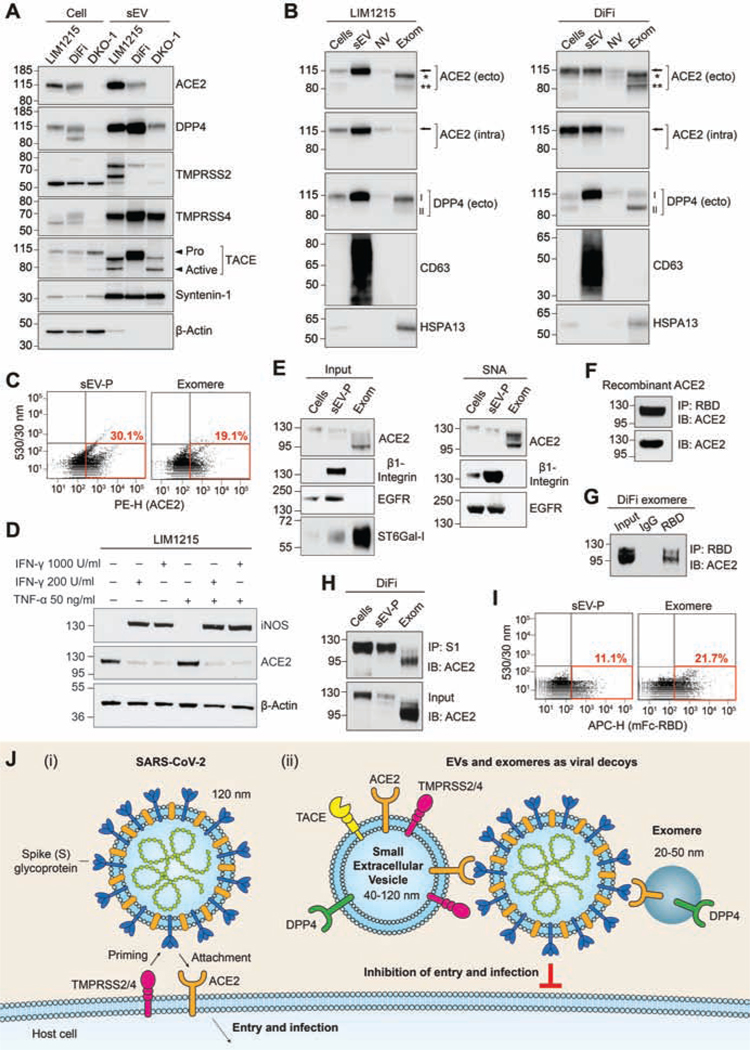

Colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines LIM1215 and DiFi express high levels of ACE2 whereas Caco-2 express much less, and ACE2 was undetectable in DKO-1 (Supplementary Figure 1A). Following high-resolution density gradient purification1, ACE2 was found to be secreted in LIM1215 and DiFi sEVs while DPP4 was enriched in sEVs from LIM1215, DiFi and DKO-1 cells (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1B). The proteases TACE, TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 were all expressed by LIM1215, DiFi and DKO-1 cells, and secreted in sEVs (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1A). To investigate further, we fractionated extracellular samples into sEV, non-vesicular (NV) and exomere fractions.1,2 While cells and sEVs contained full-length ACE2, the two ectodomain glycoforms of ACE2 were present in exomeres (Figure 1B). The full-length ACE2 in cells and sEVs was detected with antibodies recognizing ectodomain and intracellular epitopes. However, the two shed ectodomain fragments present in exomeres were only detected with the ectodomain-specific ACE2 antibody, confirming identity (Figure 1B). Additionally, full-length DPP4 was highly enriched in sEVs from both LIM1215 and DIFI cells while shed ectodomain DPP4 was present in exomeres (Figure 1B). Both DiFi cell-derived ACE2-containing sEVs and exomeres could be analyzed using fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting (FAVS) with an APC-conjugated polyclonal antibody recognizing the ectodomain of ACE2 (Figure 1C). FAVS detection of sEVs was confirmed by using a monoclonal antibody to the ectodomain of ACE2 (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and exomeres containing ACE2 can bind SARS-CoV-2 through the virus spike (S) protein. (A) Immunoblot analysis of cells and sEVs purified by high-resolution density gradients. (B) LIM1215 (left panel) and DiFi (right panel) samples were fractionated followed by immunoblotting. Arrow, full-length ACE2; * indicates ectodomain glycoform 1 of ACE2; ** indicates ectodomain glycoform 2 of ACE2. ACE2 (ecto), ectodomain-specific monoclonal antibody. ACE2 (intra), intracellular-specific monoclonal antibody. I indicates glycosylated DPP4, II indicates non-glycosylated DPP4. Anti-CD63 and -HSPA13 are used as exosomal and exomere markers, respectively. NV, non-vesicular. Exom, exomere. (C) FAVS analysis for ACE2 expression in sEV-pellets (P) and exomeres from DiFi cells using an ectodomain-specific polyclonal antibody directly conjugated to PE. (D) Immunoblot analysis of iNOS and ACE2 expression in LIM1215 cells treated with indicated doses of IFN-γ and TNF-α. (E) Sample inputs (left) and agarose-conjugated Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) lectin pull-downs (right) were analyzed by immunoblotting. β1-Integrin and EGFR are known to be α2,6-sialylated and were used as positive controls.(F) Binding of human recombinant soluble ACE2 to the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 S protein. IP, immunoprecipitation. IB, immunoblotting. (G) Binding of DiFi exomeres with RBD of SARS-CoV-2 S protein. (H) Binding of DiFi cells, sEV-P and exomeres with the S1 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 S protein. (I) FAVS analysis for binding of DiFi sEV-P and exomere to a mouse Fc-tagged RBD of SARSCoV-2 S protein.(J) Schematic illustration of (i) SARS-CoV-2 viral infection of ACE2-positive cells and (ii) inhibition of infection due to hypothetical viral decoy binding by ACE2-positive sEVs and exomeres. Similarly, DPP4-positive sEVs and exomeres may act as decoys for MERS-CoV.

Since inflammatory cytokines modulate expression of ACE29 and inflammation influences ACE2 mRNA levels in ileal and colonic tissue10, we sought to determine the baseline inflammatory state of CRC cells secreting sEV- and exomere-containing ACE2. Under the growth conditions used for production of sEVs and exomeres, levels of the inflammatory marker, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), were clearly detectable in Caco-2 cells but were undetectable in DLD-1, LIM1215 and DiFi cells (Supplementary Figure 2A). ACE2 levels were high in DiFi and LIM1215 cells, but much lower in Caco-2 and undetectable in DLD-1 cells. However, following treatment with the inflammatory cytokine, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), or co-treatments with IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), the expression of iNOS was strongly induced in both LIM1215 and DiFi cells (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 2B). Furthermore, these inflammatory cytokines significantly reduced ACE2 protein levels in both LIM1215 and DiFi cells while ACE2 levels in Caco-2 cells were relatively unchanged (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 2B). Thus, under these culture conditions, LIM1215 and DiFi cells were in a non-inflammatory state at baseline, but IFN-γ, in particular, decreased cellular levels of ACE2.

ACE2 and DPP4 are type I or type II transmembrane receptors, respectively, and both are known to be extensively glycosylated in their respective N-terminal or C-terminal ectodomains. The enzyme responsible for α2,6-sialylation, β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6Gal-I), was enriched in DiFi exomeres (Figure 1E, left panel).We isolated total α2,6-sialylated proteins by Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) lectin pull-down and probed for ACE2 by immunoblotting. Full-length ACE2 in cells and sEVs was modified by α2,6-sialylation as were the two ectodomain glycoforms secreted in exomeres (Figure 1E, right panel).

Virus-receptor recognition occurs through the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 with the extracellular peptidase of the ACE2 ectodomain.4 As the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein subunit S1 binds the ectodomain of ACE2, the presence of the ectodomain of ACE2 in exomeres suggested these extracellular nanoparticles might bind the virus. We first confirmed a mouse Fc-tagged RBD of the S1 subunit could bind human recombinant soluble ACE2 (Figure 1F). We next demonstrated that DiFi exomeres containing ACE2 could be bound and pulled down with the mouse Fc-tagged RBD (Figure 1G). Moreover, the S1 subunit could bind DiFi cells, sEVs and exomeres that all contain ACE2 (Figure 1H). FAVS analysis further confirmed that ACE2-positive DiFi sEVs and exomeres could bind to the RBD (Figure 1I), while sEVs and exomeres from the ACE2-negative LS174T cell line could not (Supplementary Figure 2C and D). It has been demonstrated that human soluble recombinant ACE2 can act as decoy for SARS-CoV-2 and thereby inhibit infection.8 Based on our characterization of extracellular carriers of ACE2, and their binding to SARS-CoV-2 S protein, we propose that ACE2-containing sEVs and exomeres may also act as decoys to inhibit infection (Figure 1J).

Discussion

We show full-length ACE2 and DPP4, critical receptors for SARS-CoV-1, −2 and MERS-CoV, respectively, are released in sEVs from CRC cells and that shed ectodomain fragments of ACE2 and DPP4 are enriched in exomeres. To our knowledge, we provide the first evidence that ACE2 in cells, sEVs and exomeres is α2,6-sialylated. Both sEVs and exomeres released from cells expressing ACE2 can bind to the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein S1 subunit. Thus, human cells might be used for large-scale production of EVs and exomeres containing fully post-translationally modified ACE2 that can be used as decoys for SARS-CoV-2 to attenuate infection, as has been demonstrated for human soluble recombinant ACE2.8 Studies comparing the efficiency and stability of S protein binding between recombinant soluble ACE2, sEVs containing full-length ACE2, and exomeres containing ectodomain ACE2 may inform the best therapeutic intervention for COVID-19 infections. The inflammatory state of gastrointestinal tissues can influence the expression of ACE2.10 Intriguingly, we find that induction of inflammation can lead to a marked reduction of ACE2 protein expression in LIM1215 and DiFi CRC cells. Further study is necessary to determine if inflammatory modulation of cellular ACE2 expression results in altered secretion of ACE2-containing sEVs and exomeres. It is possible that inflammation leads to increased secretion of ACE2 in sEVs and exomeres, thereby lowering cellular levels or that lower cellular levels results in decreased release of ACE2. In either case, the inflammatory state of tissues may influence the proposed decoy effect of extracellular ACE2.

To enable binding to ACE2, the transmembrane serine proteases TMPRSS2 or TMPRSS4 prime the SARS-CoV-2 S protein. Additionally, the proteases TACE and TMPRSS2 cleave ACE2 to release the ectodomain. Thus, the activity of these proteases is critical for infection and these proteins may represent important clinical targets.4 We found that TMPRSS2, TMPRSS4 and TACE are all secreted in sEVs and are thus present in the extracellular environment allowing them to potentially interact with viral particles. It is currently unknown if the sEV-embedded proteases play any role in priming of coronavirus S proteins, or if transfer of these proteases to recipient cells can prime cells for subsequent virus entry into host cells. Our findings have potential important implications for COVID-19, SARS and MERS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert H. Carnahan of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Center for useful discussions and providing reagents. The authors acknowledge the support of Vanderbilt Digestive Diseases Research Center and Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center.

Funding

This work was supported by the DARPA grant HR0011-18-2-0001, NIH contract 75N93019C00074 and the Dolly Parton COVID-19 Research Fund at Vanderbilt to James E. Crowe, Jr., and National Cancer Institute R35 CA197570, UG3 241685 and P50 236733 to Robert J. Coffey.

James E. Crowe Jr. has served as a consultant for Takeda Vaccines, Sanofi-Aventis U.S., Pfizer, Novavax, Lilly and Luna Biologics, is a member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of CompuVax and Meissa Vaccines and is Founder of IDBiologics. The Crowe laboratory at Vanderbilt University Medical Center has received sponsored research agreements from Moderna and IDBiologics.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- DPP4

dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- FAVS

fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- NV

non-vesicular

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- sEV

small extracellular vesicle

- SNA

Sambucus nigra agglutinin

- ST6Gal-I

β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase 1

- TACE

tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane serine protease 2

- TMPRSS4

transmembrane serine protease 4

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The other authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jeppesen DK, et al. Cell 2019;177:428–445 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Q, et al. Cell Rep 2019;27:940–954 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. Nature 2020;579:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, et al. Cell 2020;181:271–280 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raj VS, Mou H, et al. Nature 2013;495:251–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding S, Liang TJ. Gastroenterology 2020;159:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zang R, Gomez Castro MF, et al. Sci Immunol 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monteil V, et al. Cell 2020;181:905–913 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lang A, et al. Virology 2006;353:474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak JK, et al. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1151–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.