Abstract

Objective:

ADHD symptom severity appears to be exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. The present study surveyed top problems experienced by adolescents and young adults (A/YAs) with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic to identify possible reasons for symptom escalation and potential targets for intervention. We also explored perceived benefits of the pandemic for A/YAs with ADHD.

Method:

At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (April-June 2020), we administered self and parent ratings about current and pre-pandemic top problem severity and benefits of the pandemic to a sample of convenience (N=134 A/YAs with ADHD participating in a prospective longitudinal study).

Results:

The most common top problems reported in the sample were social isolation (parent-report: 26.7%; self-report: 41.5%), difficulties engaging in online learning (parent-report: 23.3%, self-report: 20.3%), motivation problems (parent-report: 27.9%), and boredom (self-report: 21.3%). According to parent (d=.98) and self-report (d=1.33), these top problems were more severe during the pandemic than in prior months. Contrary to previous speculation, there was no evidence that pandemic-related changes mitigated ADHD severity. Multi-level models indicated that A/YAs with higher IQs experienced severer top problems exacerbations at the transition to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions:

For A/YAs with ADHD, several risk factors for depression and school dropout were incurred during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. A/YAs with ADHD should be monitored for school disengagement and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recommended interventions attend to reducing risk factors such as increasing social interaction, academic motivation, and behavioral activation among A/YAs with ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD, Adolescence, COVID-19

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) occurs in 5-10% of youth and is characterized by impairing attention problems and hyperactivity/impulsivity (Barkley, 2014; Danielson et al., 2018). As research emerges on the impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on mental health, findings suggest symptom increases among youth with ADHD (Becker et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Elevated ADHD symptoms, even when time-limited, can beget risks for serious impairments such as school failure, major depression, substance abuse, and conflict with family members (Edwards et al., 2001; Kent et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Meinzer et al., 2014; Sibley et al., 2019). A looming concern for older youth with ADHD is that pandemic-related symptom exacerbations might lead to permanent negative consequences such as grade retention or dropout, legal problems, heavy substance use, or suicidal/parasuicidal behaviors (Barkley et al., 1991; Elkins et al., 2018; Hinshaw et al., 2012; Sibley et al., 2011). Research is necessary to establish the clinical needs of adolescents and young adults (A/YAs) with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic and offer empirically-informed guidelines for assessment and treatment of ADHD during this global event.

A/YAs with ADHD (versus children) may be at particular risk for experiencing pandemic-related increases in ADHD severity and/or related impairments (Becker et al., 2020; Cortese et al., 2020). For one, secondary and post-secondary students are expected to independently manage large-parcel academic work (Barber & Olson, 2004; Eccles, 2004) with minimal scaffolding from parents and teachers (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Unlike elementary school, these academic contexts demand self-regulated learning—the ability to independently regulate one’s motivational state and behavior when completing schoolwork (Zimmerman, 2002). Pandemic-related shifts to low-structure, online learning environments heighten demands for self-regulated learning by eliminating structured school routines and reducing teacher prompts, assistance, and reinforcements. With deficits in many psychological processes that support self-regulated learning (Lee & Zentall, 2017; Modesto-Lowe et al., 2013; Sonuga-Barke, 2003), A/YAs with ADHD may experience worsening symptoms as they adjust to home learning. Pandemic-related symptom exacerbations may resemble maladjustment noted when youth with ADHD transition from highly-structured elementary school to less-structured middle school (Langberg et al., 2008) and from high school to fully-unstructured college (Howard et al., 2016). If ADHD symptoms become unmanageable during the pandemic, A/YAs with ADHD may risk academic disengagement and even dropout. During the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescents with ADHD appear to experience greater problems with remote learning than peers due to difficulties concentrating, trouble maintaining a structured academic routine, and poor access to school accommodations (Becker et al., 2020).

ADHD symptoms also can be exacerbated by stress exposure (Cook et al., 2017; Hartman et al., 2019; van der Meer et al., 2017), which may come as a consequence of managing safety concerns, economic hardship, and increased family chaos during the COVID-19 pandemic (Horesh & Brown, 2020). The research on ADHD severity and stress exposure suggests that mood and conduct problems may be clinical sequelae when individuals with ADHD experience high stress levels (Hartman et al., 2019; van der Meer et al., 2017). Thus, increased stress exposure during the pandemic may contribute to pandemic-related symptom and impairment exacerbations among A/YAs with ADHD.

Finally, individuals with ADHD demonstrate vulnerabilities to the onset of serious psychiatric and behavioral health problems such as mood disorders, suicidal behavior, substance abuse, and antisocial behavior—particularly during adolescence and young adulthood (Huang et al., 2018; Meinzer et al., 2014; Sibley et al., 2011; Wilens et al., 1997). There is a concern that the pandemic may engage known mechanisms of risks and trigger initial psychiatric episodes—particularly for A/YAs with ADHD, who are vulnerable to the onset of comorbidities. For example, feelings of social isolation are a known consequence of COVID-19-related social distancing and quarantine (Courtet et al., 2020) and predicts onset of depression and suicide attempts in adolescents (Hall-Lande et al., 2007). School connectedness may decrease as students move to online learning formats (Becker et al., 2020) and is an important protective factor against adolescent substance use in youth with ADHD (Flory et al., 2011). Family conflict may increase during COVID-19 as a consequence of confinement (Behar-Zusman et al., 2020) and predicts onset of depression among adolescents with ADHD (Eadeh et al., 2017; Ward et al., 2019). Identifying emergent risk factors experienced by A/YAs with ADHD during COVID-19 confinement might guide targeted screening and prevention efforts.

The present study was designed to survey the top problems experienced by A/YAs with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic, the extent to which these problems were acutely exacerbated at the transition to pandemic confinement, and individual-level predictors of accelerated impairment during the pandemic. We also explored perceived benefits of the pandemic for A/YAs with ADHD. Our sample of convenience included 134 A/YAs with ADHD (ages 13-22) who were scheduled for research assessments during the COVID-19 pandemic (April to June 2020) as part of long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of psychosocial treatment for adolescent ADHD (Sibley et al., 2020). We hypothesized that top problems severity would increase from pre to peri-pandemic and that top problems reported by A/YAs with ADHD and their parents would include known risk factors (e.g., social isolation, increased family conflict, difficulties engaging with online learning) for the onset of adverse outcomes. We hypothesized greater pandemic-related top problems exacerbations would be predicted by higher family adversity, male sex, younger age, lower IQ, ADHD-Combined subtype, comorbid Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), presence of an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or Section 504 Plan, and absence of medication treatment.

Method

Participants

Original Sample.

At baseline (2015-2018), participants (N=278; ages 11-17) were incoming patients at four community agencies in a large pan-Latin American and pan-Caribbean U.S. city. They were required to meet full criteria for ADHD according to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) based on a structured diagnostic interview (Shaffer et al., 2000) and parent and teacher symptom and impairment ratings (Fabiano et al., 2006; Pelham et al., 1992) that were reviewed by two licensed psychologists on the research team. Autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability (IQ<70) were exclusionary. For more information about the full sample, see Sibley et al., 2020.

Current Subsample.

At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, we initiated data collection with a sample of convenience (N=134) who were scheduled to participate in a wave of long-term follow-up assessments between April and June 2020. The full wave was ongoing from January to July 2020. Parent and self assessments were completed separately; an unequal number of parent (n=92) and self (n=86) assessments were conducted during the COVID-19 study period as this sub-study was terminated at the conclusion of the local school year (June 2020) and began midway through the scheduled data collection wave.

The 134 A/YAs (age range 13-22) with either parent or self report COVID-19 data were included in the present study. Demographic characteristics of the subsample are presented in Table 1. Slight differences between the original sample and current subsample were noted as well as differences between those with and without parent and adolescent reports in the subsample1. During the pandemic, 3.7% of youth attended school in person, 83.6% completed school online using a curriculum provided by the school, .7% completed school at home using curriculum provided by the parent, 8.2% did not participate in schooling, and 3.7% endorsed “other.”

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Average age (Mean ± sd) | 17.11 ± 1.62 |

| Average IQ (Mean ± sd) | 97.25 ± 13.71 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) Diagnosis | |

| Yes | 49.30% |

| No | 50.70% |

| ADHD Symptom Count at Follow-up (Mean ± sd) | |

| Inattention | 4.46 ± 3.23 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | 2.76 ± 2.70 |

| ADHD Medication at Follow-up | |

| Yes | 21.60% |

| No | 78.40% |

| Sex | |

| Male | 65.70% |

| Female | 34.30% |

| Race/ Ethnicity | |

| Latinx | 85.10% |

| Non-White (African-American, Black, Mixed Race) | 10.40% |

| White | 4.50% |

| Received School Accommodations | |

| Yes | 39.80% |

| No | 60.20% |

| Parent Bachelor’s Degree | 52.20% |

| Parent Marital Status | |

| Single (Divorced, Never married) | 30.60% |

| Married | 69.40% |

| Parent English Proficiency | |

| Proficient | 52.20% |

| Non-Proficient | 47.80% |

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the Florida International University Institutional Review Board. All participants and parents provided written informed consent and/or assent at baseline and long-term follow-up. Detailed information about the original trial is published elsewhere (Sibley et al., 2020). Briefly, participants with ADHD were randomly assigned to receive a 10-week evidence-based psychosocial treatment protocol or usual care provided by community mental health practitioners at the agency at which they sought care. Participants in both groups were assessed at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up (~4.70 months after post-treatment) during the acute phase of the trial.

On average, data collection for the long-term follow-up wave occurred 2.57 years (SD=.80) after study treatment concluded. Beginning in January 2020, the full sample (parents and A/YAs) were separately contacted to consent to participation and complete a long-term follow-up assessment consisting of parent and self-ratings of symptoms and impairments. Based on participant preference, assessments were administered either by online survey (47.5%) or phone (52.5%). Phone interviews were administered by carefully trained and supervised research assistants (a majority of whom were fluent in both English and Spanish). Research assistants were required to demonstrate fidelity to survey administration procedures in an analogue assessment prior to interaction with research participants. Participants received $50 for completing the follow-up assessment. Participants who were scheduled for assessment between April-June 2020 received an additional survey querying functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Measures

Top Problems Assessment.

A rating scale adaptation of the Top Problems (TP) assessment (Weisz et al., 2011) was administered to parents and A/YAs. Respondents were asked to list the A/YA’s three “top problems” during the COVID-19 pandemic using their own words. Following indication of top problems, respondents were asked to rate the severity of each problem from 0 to 6 (lower numbers indicated lower severity). Finally, for each problem, respondents were asked to rate the severity the problem immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic using the same scale. Although the full psychometrics of the TP rating scale adaptation remain untested, the standard TP assessment demonstrates strong convergent validity with established measures of youth psychopathology (Weisz et al., 2011). A TP average score was computed as the mean severity score across all reported top problems.

To code the top problems assessment, we consulted the TP assessment coding manual (Herren et al., 2018). Based on recommendations, responses to the TP assessment were not coded if they were vague (e.g., “communication”, “allergies”, “I don’t know”) or utilized wording without a clear behavioral or emotional referent (e.g., “unable to log in to do class work”, “unable to get financial assistance, “computer not working properly”). This led to the exclusion of 15 top problems noted by parents (5.4%) and 33 top problems noted by teens (12.8%); but no participant had all three top problems excluded for any rater. The resulting responses were coded using procedures by Merriam (1998). Research staff segmented responses into distinct units of data that represented the smallest possible pieces of information that were relevant to the question (i.e., when top problems included double problems). Four coders were instructed to review a unique subset of the data to create categories that were relevant, exhaustive (place all data into a category), and mutually exclusive. The coders gave each category a name that matched its content. Following independent category construction, coders compared the list of categories. The independent coders collaborated to create a final list of categories, each with an operational definition and key examples. In a final step, coders were tasked with reviewing the full set of data (two coders reviewed the parent responses and two coders reviewed the youth responses) and sorted each response using the finalized list of categories and their definitions. Coders were blind to study hypotheses during coding. Responses provided by parents in Spanish were coded by Spanish speaking coders. Twenty percent of codes were double coded to assess inter-rater reliability, which was kappa=.83, indicating strong agreement (McHugh, 2012).

Benefits of COVID-19.

We developed a scale that mirrored the TP assessment and asked parents and teens to report on “the three top benefits that your teen is experiencing due to lifestyle changes surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic?” For each listed benefit, respondents were asked “How is this benefit impacting the teen’s ADHD severity?” Response scale ranged from “−2 greatly decreasing ADHD severity” to “+2 greatly increasing ADHD severity.” Benefits were coded using the process described above. Inter-rater reliability was kappa=.78, indicating moderate agreement (McHugh, 2012).

Predictors of Top Problem Severity.

We tested eight potential predictors of top problem severity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Age (derived from birth date) and sex were measured from participant report on a standard demographic questionnaire that was administered at baseline. Current stimulant medication and presence of an IEP/Section 504 Plan were measured using a comprehensive treatment questionnaire (Kuriyan et al., 2014) administered to participants and their parents at each assessment. ADHD subtype (Predominantly Inattentive, Combined) and ODD diagnosis were measured at baseline using the diagnostic process described previously. IQ was measured at baseline using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-2nd Edition (WASI-II; Wechsler, 2011). Family adversity was measured using a cumulative risk index. We previously adapted the Rutter Family Adversity Index (Coxe et al., under review; Rutter et al., 1975) to fit the sample context (i.e., high prevalence of immigrant families) and available data. The resulting score (0-4) equally weighed the following risk factors: (1) single parent household, (2) all parents with a high school degree or less (indicator of low socioeconomic status), (3) all parents with limited English proficiency, and (4) greater than two children living in the home. Higher scores on the family adversity index indicated presence of more risk factors.

Analytic Plan.

Sample moments for qualitatively coded top problems and benefits were presented descriptively. Repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to evaluate pre- and peri-pandemic perceived differences in TP severity. Cohen’s d standardized difference scores were calculated. To examine whether eight youth characteristics (e.g., family adversity, IQ) predicted changes in parents’ and youths’ perceived TP severity during the transition to COVID-19, multi-level models were conducted using Mplus 8.1. These models adjusted for the nesting of time points within individuals. First, both parent and teen-rated severity were regressed onto a time variable (0 = pre-COVID, 1 = peri-COVID) at the within-person level (Level 1). Then, each predictor was added independently at the between-person level (Level 2). A cross-level interaction was modeled to examine whether each predictor moderated the effect of time. The Johnson-Neyman method was used to probe significant interactions, which plots continuous changes in the slope between time and TP severity at differing levels of the moderator, as opposed to relying on cut-off scores, such as +/−1SD of the moderator mean (Borich & Wunderlich, 1973; Johnson & Neyman, 1936). Full Information Maximum Likelihood was used to handle missing data, with predictors of missingness (i.e., parent education, English proficiency, IQ, Latinx ethnicity, baseline ODD diagnosis) included as auxiliary variables, by estimating their variances at the between-level.

Results

Top Problems.

Parents and A/YAs provided a range of responses to the TP assessment resulting in 14 categories of problems (see Table 2). The three most common problems reported by parents were motivation problems (27.9%), social isolation (26.7%), and difficulties engaging in online learning (23.3%). The three most common problems reported by A/YAs were social isolation (41.5%), boredom (21.3%), and difficulties engaging in online learning (20.2%). Average severity (0-6 scale) across top problems during the pandemic was 3.32 (SD=2.22) for parent report and 2.74 (SD=1.87) for self report. For parent report, perceived top problems severity during the pandemic significantly differed from pre-pandemic top problems severity (M=1.72, SD=1.64; F(1,84)=75.41, p<.001, d=0.98). For self report, the same was true (pre-pandemic M=1.05, SD=1.27, F(1,91)=92.56, p<.001, d=1.33).

Table 2.

Top Problems Reported by Adolescents and Young Adults with ADHD and their Parents during early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Endorsed by Parents% (n) | Endorsed by Youth % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Social Isolation | 26.7 (23) | 41.5 (39) |

| Difficulties Engaging in Online Learning | 23.3 (20) | 20.2 (19) |

| Motivation Problems | 27.9 (24) | 14.9 (14) |

| Boredom | 8.1 (7) | 21.3 (20) |

| Sleep Dysregulation | 14.0 (12) | 8.5 (8) |

| Concentration Problems | 11.6 (10) | 9.6 (9) |

| Organization, Time management, and Planning Problems | 10.5 (9) | 6.4 (6) |

| Anxiety | 9.3 (8) | 7.4 (7) |

| Reduced Physical Activity | 5.8 (5) | 9.6 (9) |

| Irritability | 11.6 (10) | 3.2 (3) |

| Depression | 8.1 (7) | 3.2 (3) |

| Conflict with family members | 1.2 (1) | 9.6 (9) |

| Difficulty Following Safety Guidelines | 2.3 (2) | 3.2 (3) |

Benefits.

To explore whether certain functional problems improved during the pandemic, we also coded top benefits of the pandemic for A/YAs with ADHD. Parents and youth provided a range of responses to the benefits assessment resulting in 19 categories of benefits (see Table 3). The three most common benefits reported by parents were spending more time with family (43.0%), more time available to complete academic work (12.8%), and reduced anxiety (12.8%). The three most common benefits reported by A/YAs were more unstructured time to relax (39.4%), spending more time with family (29.8%), and more time available to complete academic work (21.3%). With respect to the impact of these benefits on ADHD symptom severity (−2 to +2 scale), parents reported an average benefit impact score of −.26 (SD=0.89) and A/YAs reported an average benefit impact score of −.38 (SD=0.80). These scores correspond most closely with the anchor of “0=No Impact on ADHD severity.”

Table 3.

Top Benefits Reported by Adolescents and Young Adults with ADHD and their Parents during early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Endorsed by Parents% (n) | Endorsed by Youth % (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spending More Time with Family | 43.0 (37) | 29.8 (28) |

| More Unstructured Time to Relax | 11.6 (10) | 39.4 (37) |

| More Time Available to Complete Academic Work | 12.8 (11) | 21.3 (20) |

| Improved Sleep | 11.6 (10) | 17.0 (16) |

| Increased Self-Awareness | 11.6 (10) | 17.0 (16) |

| Reduced Anxiety | 12.8 (11) | 8.5 (8) |

| Improved Concentration | 9.3 (8) | 10.6 (10) |

| School Demands Decreased | 11.6 (10) | 7.4 (7) |

| Enjoying Staying at Home | 7.0 (6) | 10.6 (10) |

| Improved Grades | 5.8 (5) | 7.4 (7) |

| Reduced Irritability/Mood Problems | 9.3 (8) | 1.1 (1) |

| Healthier Eating Habits | 1.2 (1) | 7.4 (7) |

| Social Isolation | -- | 8.5 (8) |

| Completing More Household Tasks | 5.8 (5) | 3.2 (3) |

| Increased Social Interaction | 2.3 (2) | 5.3 (5) |

| Increased physical activity | 2.3 (2) | 4.3 (4) |

| Increased Parental Monitoring | 5.9 (5) | --- |

| Increased Health-Conscious Behaviors | 4.7 (4) | 1.1 (1) |

| Improved Finances | 1.2 (1) | 2.1 (2) |

Predictors of Escalating Problems at the Transition to COVID-19.

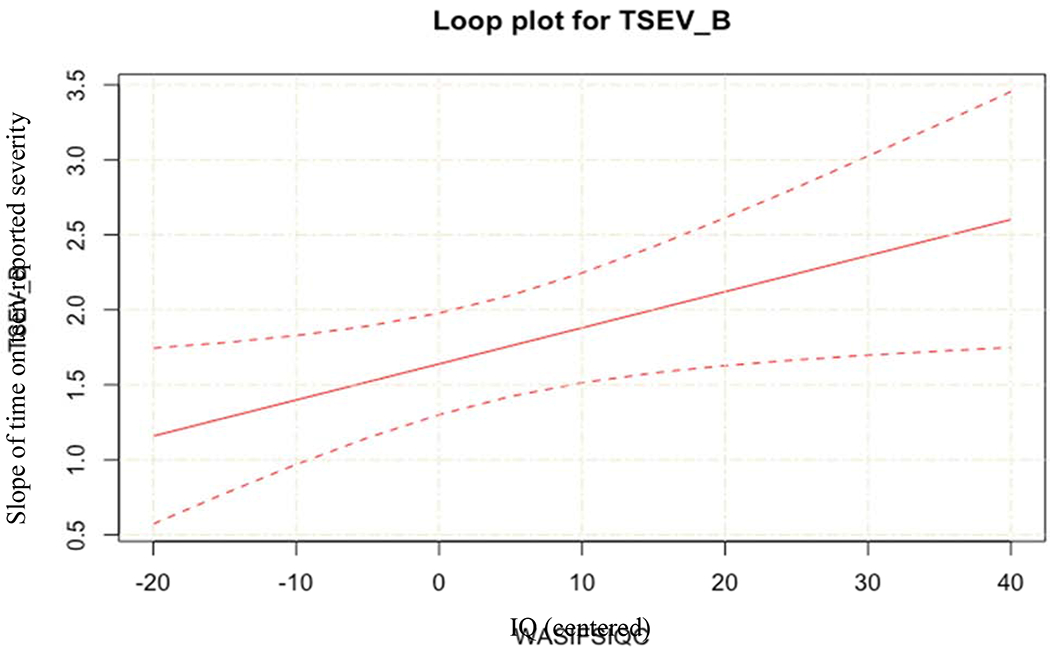

In the initial model with no demographic predictors, time was a significant predictor of both self-reported and parent-reported severity indicating increased problem severity from pre to peri-pandemic. Both A/YAs (B = 1.67(0.17), p < .001) and parents (B = 1.61(0.18), p < .001) reported increases in severity during COVID-19 than prior to the pandemic. Of the 8 moderators of change in parent- or self-reported severity (see Table 4), only IQ significantly moderated the relationship between time and severity for A/YAs (B = 0.02(0.01), p = .04), but not for parents (B = 0.01(0.01), p = .73). As IQ increased, A/YAs reported higher degrees of change in severity of their top problems from pre- to peri-COVID (although the change in severity was still significant for all participants in the sample).

Table 4.

Predictors of Top Problem Exacerbation during the COVID-19 Pandemic

| A/YA | Parents | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Main Effect (pre-COVID = 0) | Predictor Main Effect | Time*Predictor Interaction | Time Main Effect (pre-COVID = 0) | Predictor Main Effect | Time*Predictor Interaction | |||||||||||||

| Predictors | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Age | 2.02 | 2.29 | .38 | 0.01 | 0.10 | .95 | −0.02 | 0.13 | .88 | 1.53 | 1.92 | .43 | −0.09 | 0.11 | .41 | 0.01 | 0.11 | .96 |

| Medication (Med. = 1) | 1.72 | 0.19 | <.001 | −0.12 | 0.35 | .74 | −0.25 | 0.40 | .53 | 1.67 | 0.20 | <.001 | −0.15 | 0.30 | .71 | −0.27 | 0.46 | .56 |

| Gender (Male = 1) | 1.68 | 0.30 | <.001 | −0.54 | 0.29 | .07 | −0.04 | 0.36 | .91 | 2.05 | 0.32 | <.001 | 0.14 | 0.36 | .69 | −0.61 | 0.38 | .11 |

| Risk Index | 1.89 | 0.26 | <.001 | −0.03 | 0.10 | .79 | −0.15 | 0.15 | .30 | 1.78 | 0.30 | <.001 | 0.01 | 0.15 | .92 | −0.11 | 0.16 | .48 |

| IEP (IEP = 1) | 1.75 | 0.21 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.19 | .18 | −0.16 | 0.20 | .42 | 1.66 | 0.24 | <.001 | 0.10 | 0.24 | .69 | −0.07 | 0.23 | .78 |

| ADHD (ADHD-C = 1 ADHD- PI = 0) | 1.75 | 0.23 | <.001 | 0.10 | 0.27 | .71 | −0.18 | 0.34 | .61 | 1.92 | 0.26 | <.001 | −0.37 | 0.35 | .29 | −0.60 | 0.35 | .09 |

| Comorbid ODD (ODD = 1) | 1.81 | 0.27 | <.001 | 0.53 | 0.26 | .05 | −0.26 | 0.34 | .44 | 1.46 | 0.25 | <.001 | 0.56 | 0.35 | .10 | 0.35 | 0.37 | .34 |

| IQ | −0.50 | 1.09 | .64 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .79 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .04 | 1.17 | 1.26 | .35 | −0.01 | 0.02 | .49 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .73 |

Discussion

During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the most common top problems reported by our sample of A/YAs with ADHD included social isolation, motivation problems, boredom, and difficulties engaging in online learning. Parents and A/YAs perceived exacerbation in problem severity as the sample transitioned to the COVID-19 pandemic, in the absence of ameliorative effects on ADHD symptom severity. These exacerbations appeared to arise uniformly, regardless of an individual’s demographic and clinical characteristics. However, A/YA’s with higher IQs experienced the greatest exacerbations in self-perceived problems as they transitioned to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, most A/YAs with ADHD did not appear to experience increases in severe problem behaviors (i.e., major depression, dropout, heavy substance use, legal problems; see Table 1). Yet, as hypothesized, they demonstrated increases in several known risk factors for these adverse outcomes. The detected risk factors (i.e., social isolation, school disengagement, motivation problems, boredom) demand clinical attention given that A/YAs with ADHD are vulnerable to the negative outcomes they predict (Barkley et al., 1991; Elkins et al., 2018; Hinshaw et al., 2012; Sibley et al., 2011). Our data was collected in the early pandemic months; based on emergent risk factor in this sample, we hypothesize that late-pandemic assessments of A/YAs with ADHD will detect increases in serious adverse outcomes relative to A/YAs without ADHD.

In particular, when an A/YA with ADHD experiences social isolation, boredom, motivation problems, and/or school disengagement during the COVID-19 pandemic, they may experience a perfect storm of risk factors for major depression and school dropout. Considering both parent and self reports, negative effects of social isolation were noted in nearly half the sample (particularly by self-report) and boredom in nearly a third. Social isolation is a critical mechanism of depression onset among youth (Hall-Lande et al., 2007). Because A/YAs with ADHD demonstrate difficulties initiating social interactions and maintaining friendships outside of school, they may primarily experience social interactions in school (Bagwell et al., 2001; Ros & Graziano, 2020). As a result, they may be more vulnerable to social isolation when transitioning to home learning. Boredom proneness is associated with attention problems (Harris, 2000; Malkovsy et al., 2012) making this mental state an unsurprising sequalae of the COVID-19 pandemic for A/YAs with ADHD. Like social isolation, chronic boredom is associated with depression onset (Spaeth et al., 2015; van Hoof & van Hooft, 2016). Taken together, these findings may suggest that remote learning could be contraindicated for A/YAs with ADHD, who rely on in-person school experiences for social interactions and optimal engagement in academics.

Motivation problems mediate the relationship between ADHD and school performance (Lee et al., 2012)—in our sample, motivation difficulties may directly manifest as difficulties engaging in remote learning. A concern remains that characteristically tenuous school engagement among adolescents with ADHD (Zendarski et al., 2017) may snowball in the context of remote learning and lead to premature dropout (Becker et al., 2020). Heterogeneity in reported top problems indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic also bestowed a wide variety of challenges to individual A/YAs with ADHD such as sleep dysregulation, anxiety, and reduced physical activity, each of which contributed to the large exacerbations in peri-pandemic top problems reported in the sample (d=0.98 to 1.33).

Some speculate that COVID-19 pandemic-related changes may improve ADHD symptoms by introducing flexible schedules and greater personal space and tranquility during home learning compared to school (Bobo et al., 2020). In the present sample, parents and A/YAs reported pandemic-related benefits that included spending more time with family, increased relaxation time, and more time to complete academic work (see Table 2). However, there was no evidence that these benefits impacted ADHD symptom severity in a meaningful way. Still, it is possible that downstream effects of benefits might buffer negative consequences of risks. For example, closer family relationships may mitigate depression risk among A/YAs with ADHD (Ward et al., 2019). Mastering remote learning environments in high school may ready adolescents with ADHD for shifts to independent learning in college. On the other hand, downstream effects of pandemic-related problems (i.e., missing social interactions that are critical to adolescent identity development; O’Brien & Bierman, 1988) may be more prominent. The moderating effects of perceived problems and benefits on post-pandemic outcomes should be investigated in future research. We also note that some parent-perceived problems (i.e., sleeping during the day, too much relaxation time) were viewed as benefits to A/YAs (i.e., more lenient sleep schedules, more time to relax). Future work should investigate the role of self-perception differences in predicting longitudinal trajectories among individuals with ADHD.

Surprisingly, the subgroup at highest risk for COVID-19 pandemic-related top problems exacerbations were youth with high IQs. Although some research suggests that individuals with ADHD and high IQs demonstrate more persistent forms of the disorder (de Zeeuw et al., 2012), most work suggests that high IQ mitigates ADHD severity and promotes positive prognoses (Cheung et al., 2015; Mahone et al., 2010). Post-hoc analyses indicated that higher IQ was significantly associated with report of higher family conflict during the COVID-19 pandemic (r=.230; p=.026); thus, higher conflict may be a mechanism of greater problem exacerbations among high IQ A/YAs with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gifted A/YAs with ADHD may also experience particularly high academic demands that may be more challenging to self-manage during the shift to remote learning. In support of this possibility, Duraku & Hoxha (2020) reported that sleep disturbances and negative emotions increased in gifted high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which the COVID-19 pandemic may be particularly challenging for individuals with ADHD and high IQs.

The limitations of this study include our sample of convenience, which may inadequately represent the full population of adolescents with ADHD (e.g., adolescents with comorbid Autism Spectrum Disorder, European-American adolescents, adolescents receiving stimulant medication, adolescents with severe ADHD symptoms), or the full participant pool from which the current sample was drawn. In addition, report of pre-pandemic functioning required retrospective recall of up to three months. Retrospective reporting is more prone to reporting errors than prospectively collected data. Some predictor variables (e.g., ADHD subtype, IQ) were measured at baseline (~three years prior to COVID-19). Though stability in these variables over time is expected, it is possible that changes in these variables that occurred in the study’s follow-up period were not reflected in our analyses. Our analyses included A/YAs in middle school, high school, and college academic environments; although we found no effects of age on outcomes, future work with larger samples is needed to understand how school setting may influence the effects herein. We did not include a non-ADHD comparison group in this study, which would have elucidated whether study findings were specific to ADHD. Because participants completed TP assessments in a survey format, responses were not screened for acceptability at the time of administration. Although no informant had all three of their top problems excluded, our procedure led to the exclusion of 5.4% of parent responses and 12.8% of A/YA responses. Thus, some participant average TP scores were based on less than three top problems. We also did not ask respondents to name their three top problems immediately prior to the pandemic. Thus, we are unable to conclude whether pre-pandemic top problems got worse, or whether new top problems leapfrogged the old in severity. Finally, we did not collect pre-pandemic ADHD symptom ratings that would have facilitated mediational models that directly test whether pandemic-related exacerbations in top problems are a mechanism of ADHD symptom escalations.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, we offer several clinical recommendations for ADHD treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, youth with ADHD should be regularly monitored for depression and school avoidance, as well as risk factors that may indicate these difficulties could be forthcoming (e.g., social isolation, boredom, motivation difficulties, sleep problems, disengagement from online learning). Second, adolescent engagement in remote learning is a clear priority for treatment during the pandemic. Stimulant medication may be instrumental in promoting academic engagement (Evans et al., 2001; Pelham et al., 2017) with medium to large effects on ADHD symptoms reported in the A/YA age group (Findling et al., 2011; Wilens et al., 2006). In accordance with existing COVID-19 guidelines (CADDRA, 2020; Cortese et al., 2020), practitioners are encouraged to confirm that patient ADHD medications are appropriately titrated during the pandemic. Clinical treatment of ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic should also include a focus on creating socially rewarding peer interactions in a virtual or socially distant manner. Some research suggests that one-to-one peer activities may be more beneficial to youth with ADHD and social problems than group peer activities (Ros & Graziano, 2020). Psychosocial interventions for adolescent ADHD that specifically address motivation problems (i.e., Plan My Life, Boyer et al., 2015; Supporting Teens’ Autonomy Daily; STAND; Sibley et al., 2016) may be particularly appropriate during the pandemic and can be successfully delivered via telehealth (Sibley et al., 2017). For maximal impact, utilizing combined treatment approaches may be especially appropriate for adolescents and young adults with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic. We anticipate that many of these recommendations will remain relevant post-pandemic—particularly for A/YAs with ADHD who engage in remote learning.

Figure 1.

Johnson-Neyman Plot outlining the change in slope between time and teen-reported top problem severity at increasing levels of IQ (solid red line) and confidence intervals (dotted lines).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Compared to the full sample (N=278), the COVID-19 subsample possessed significantly higher parent education levels (p=.037), lower parent English proficiency (p=.037), and higher full-scale IQs (p=.039). Compared to the subsample with only teen data (N=48), those with parent data (N=86) were more likely to identify as Latinx (p=.008) and have parents with limited English proficiency (p=.011). Compared to the subsample with only parent data (N=42), those with teen data (N=92) were more likely to have a baseline ODD diagnosis (p=.043). These differences may reflect facilitators to scheduling follow-up appointments (i.e., parents with English proficiency and adolescents without ODD may have been easier to schedule for assessments from January-March, completing data collection wave prior to COVID-19).

Reference

- Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, & Hoza B, 2001. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: Predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1285–1292. 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, & Olsen JA, 2004. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(1), 3–30. 10.1177/0743558403258113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA (2014). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Anastopoulos AD, Guevremont DC, & Fletcher KE, 1991. Adolescents with ADHD: Patterns of behavioral adjustment, academic functioning, and treatment utilization. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(5), 752–761. 10.1016/S0890-8567(10)80010-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Breaux R, Cusick CN, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Sciberras E, & Langberg JM, in press. Remote learning during COVID-19: Examining school practices, service continuation, and difficulties for adolescents with and without ADHD. Journal of Adolescent Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar-Zusman V, Chavez JV, & Gattamorta K, 2020. Developing a measure of the impact of COVID-19 social distancing on household conflict and cohesion. Family Process, 59(3), 1045–1059. 10.1111/famp.12579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo E, Lin L, Acquaviva E, Caci H, Franc N, Gamon L, Picot MC, Pupier F, Speranza M, Falissard B, & Purper-Ouakil D, 2020. How do children and adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) experience lockdown during the COVID-19 outbreak? Encephale, 46(3). 10.1016/j.encep.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borich GD, & Wunderlich KW, 1973. Johnson-neyman revisited: Determining interactions among group regressions and plotting regions of significance in the case of two groups, two predictors, and one criterion. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 33(1), 155–159. 10.1177/001316447303300118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer BE, Geurts HM, Prins PJM, & Van der Oord S, 2015. Two novel CBTs for adolescents with ADHD: the value of planning skills. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(9), 1075–1090. 10.1007/s00787-014-0661-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CADDRA (2020). ADHD and COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions. (https://www.caddra.ca/wp-content/uploads/CADDRA-ADHD-and-Virtual-Care-FAQ.pdf). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cheung CHM, Rijdijk F, McLoughlin G, Faraone SV, Asherson P, & Kuntsi J, 2015. Childhood predictors of adolescent and young adult outcome in ADHD. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 62, 92–100. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, DeRosa R, Hubbard R, Kagan R, Liautaud J, Mallah K, Olafson E, & Van Der Kolk B, 2005. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 390–398. 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Asherson P, Sonuga-Barke E, Banaschewski T, Brandeis D, Buitelaar J, Coghill D, Daley D, Danckaerts M, Dittmann RW, Doepfner M, Ferrin M, Hollis C, Holtmann M, Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Santosh P, Rothenberger A, Soutullo C, … Simonoff E, 2020. ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: Guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 4(6), 412–414. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30110-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtet P, Olie E, Debien C, & Vaiva G, 2020. Keep socially (but not physically) connected and carry on: Preventing suicide in the age of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 81(3), e20com13370–e20com13370. 10.4088/JCP.20com13370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe SJ, Sibley MH, & Becker SP (under review). Presenting Problems Profiles for Adolescents with ADHD: Differences by Race, Sex, Age, and Family Adversity. Paper submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, & Blumberg SJ, 2018. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 199–212. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1417860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zeeuw P, Schnack HG, van Belle J, Weusten J, van Dijk S, Langen M, Brouwer RM, van Engeland H, & Durston S, 2012. Differential brain development with low and high IQ in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. PLoS ONE, 7(4), e35770. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraku ZH, & Hoxha N (2020). The impact of COVID-19, school closure, and social isolation on gifted students’ wellbeing and attitudes toward remote (online) learning. Unpublished manuscript. Downloaded January 4, 2021 from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zamira_Hyseni_Duraku/.

- Eadeh HM, Bourchtein E, Langberg JM, Eddy LD, Oddo L, Molitor SJ, & Evans SW, 2017. Longitudinal evaluation of the role of academic and social impairment and parent-adolescent conflict in the development of depression in adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2374–2385. 10.1007/s10826-017-0768-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, 2004. Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In handbook of adolescent psychology. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Berkley RA, Laneri M, Fletcher K, & Metevia L, 2001. Parent-adolescent conflict in teenagers with ADHD and ODD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29(6), 557–572. 10.1023/A:1012285326937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, Saunders GRB, Malone SM, Wilson S, McGue M, & Iacono WG, 2018. Mediating pathways from childhood ADHD to adolescent tobacco and marijuana problems: Roles of peer impairment, internalizing, adolescent ADHD symptoms, and gender. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 59(10), 1083–1093. 10.1111/jcpp.12977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Pelham WE, Smith BH, Bukstein O, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Altenderfer L, & Baron-Myak C, 2001. Dose-response effects of methylphenidate on ecologically valid measures of academic performance and classroom behavior in adolescents with ADHD. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 9(2), 163. 10.1037/1064-1297.9.2.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, Onyango AN, Kipp H, Lopez-Williams A, & Burrows-MacLean L, 2006. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 369–385. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling R, Childress A, Cutler A, Gasior M, Hamdani M, Ferreira C, & Squires L (2011) Efficacy and Safety of Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate in Adolescents with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Malone PS, & Lamis DA, 2011. Childhood ADHD symptoms and risk for cigarette smoking during adolescence: School adjustment as a potential mediator. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 320. 10.1037/a0022633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Lande JA, Eisenberg ME, Christenson SL, & Neumark-Sztainer D, 2007. Social isolation, psychological health, and protective factors in adolescence. Adolescence, 42(166), 265. Gale Academic OneFile. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MB, 2000. Correlates and characteristics of boredom proneness and boredom. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(3), 576–598. 10.1111/j.15591816.2000.tb02497.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman CA, Rommelse N, van der Klugt CL, Wanders RBK, & Timmerman ME, 2019. Stress exposure and the course of ADHD from childhood to young adulthood: comorbid severe emotion dysregulation or mood and anxiety problems. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8(11), 1824. 10.3390/jcm8111824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herren J, Garibaldi P, Evan SC, & Weisz JR, 2018. Youth top problems assessment manual. Available online at: https://weiszlab.fas.harvard.edu/files/jweisz/files/top_problems_assessment_manual_09.11.18.pdf (accessed 30 September 2020).

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Zalecki C, Huggins SP, Montenegro-Nevado AJ, Schrodek E, & Swanson EN, 2012. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1041–1051. 10.1037/a0029451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horesh D, & Brown AD, 2020. Covid-19 response: Traumatic stress in the age of Covid-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 331. 10.1037/TRA0000592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AL, Strickland NJ, Murray DW, Tamm L, Swanson JM, Hinshaw SP, Eugene Arnold L, & Molina BSG, 2016. Progression of impairment in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through the transition out of high school: Contributions of parent involvement and college attendance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(2), 233. 10.1037/abn0000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zheng Z, Zhu T, Qu Y, & Mu D, 2018. Maternal smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 141(1) 234–238. 10.1542/peds.2017-2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, & Neyman J, 1936. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kent KM, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Sibley MH, Waschbusch DA, Yu J, Gnagy EM, Biswas A, Babinski DE, & Karch KM, 2011. The academic experience of male high school students with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(3), 451–462. 10.1007/s10802-010-9472-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE Jr, Molina BS, Waschbusch DA, Sibley MH, & Gnagy EM (2014). Concordance between parent and physician medication histories for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 24(5), 269–274. 10.1089/cap.2013.0081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Epstein JN, Altaye M, Molina BSG, Arnold LE, & Vitiello B, 2008. The transition to middle school is associated with changes in the developmental trajectory of ADHD symptomatology in young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 651–663. 10.1080/15374410802148095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, & Zentall SS, 2017. Reading motivation and later reading achievement for students with reading disabilities and comparison groups (ADHD and typical): A 3-year longitudinal study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 50, 60–71. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NC, Krabbendam L, Dekker S, Boschloo A, de Groot RHM, & Jolles J, 2012. Academic motivation mediates the influence of temporal discounting on academic achievement during adolescence. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 1(1), 43–48. 10.1016/j.tine.2012.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, & Glass K, 2011. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 328–341. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahone EM, Hagelthorn KM, Cutting LE, Schuerholz LJ, Pelletier SF, Rawlins C, Singer HS, & Denckla MB, 2002. Effects of IQ on executive function measures in children with ADHD. Child Neuropsychology, 8(1), 52–65. 10.1076/chin.8.1.52.8719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkovsky E, Merrifield C, Goldberg Y, & Danckert J, 2012. Exploring the relationship between boredom and sustained attention. Experimental Brain Research, 221(1), 59–67. 10.1007/s00221-012-3147-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML, 2012. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. 10.11613/bm.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer MC, Pettit JW, & Viswesvaran C, 2014. The co-occurrence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and unipolar depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(8), 595–607. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB, 1998. Qualitative research and case study applications in education, 2nd Volume. Jossey-Bass Publisher, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Modesto-Lowe V, Chaplin M, Soovajian V, & Meyer A, 2013. Are motivation deficits underestimated in patients with ADHD? A review of the literature. Postgraduate Medicine, 125(4), 47–52. 10.3810/pgm.2013.07.2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien SF, & Bierman KL, 1988. Conceptions and perceived influence of peer groups: Interviews with preadolescents and adolescents. Child Development, 59(5), 1360–1365. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgilés M, Morales A, Delvecchio E, Mazzeschi C, & Espada JP, 2020. Immediate psychological effects of COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3588552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Evans SW, Gnagy EM, & Greenslade KE, 1992. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders: Prevalence, factor analyses, and conditional probabilities in a special education sample. School Psychology Review, 21(2), 285–299. 10.1080/02796015.1992.12085615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Smith BH, Evans SW, Bukstein O, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, & Sibley MH, 2017. The effectiveness of short- and long-acting stimulant medications for adolescents with ADHD in a naturalistic secondary school setting. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21(1), 40–45. 10.1177/1087054712474688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros R, & Graziano PA, 2020. A transdiagnostic examination of self-regulation: Comparisons across preschoolers with ASD, ADHD, and typically developing children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49(4), 493–508. 10.1080/15374416.2019.1591280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Cox A, Tupling C, Berger M, & Yule W (1975). Attainment and adjustment in two geographical areas: I—the prevalence of psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 493–509. 10.1192/bjp.126.6.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME, 2000. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC- IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–38. 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Comer JS, & Gonzalez J, 2017. Delivering parent-teen therapy for ADHD through videoconferencing: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 39(3), 467–485. 10.1007/s10862-017-9598-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Graziano PA, Coxe S, Bickman L, & Martin P, 2020. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing-enhanced behavior therapy for adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A randomized community-based trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.07.907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Graziano PA, Kuriyan AB, Coxe S, Pelham WE, Rodriguez L, Sanchez F, Derefinko K, Helseth S, & Ward A, 2016. Parent-teen behavior therapy + motivational interviewing for adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 84(8), 699. 10.1037/ccp0000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Ortiz M, Graziano P, Dick A, & Estrada E, 2020. Metacognitive and motivation deficits, exposure to trauma, and high parental demands characterize adolescents with late-onset ADHD. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(4). 10.1007/s00787-019-01382-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Biswas A, MacLean MG, Babinski DE, & Karch KM, 2011. The delinquency outcomes of boys with ADHD with and without comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(1), 21–31. 10.1007/s10802-010-9443-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, 2003. The dual pathway model of AD/HD: An elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. 27(7), 593–604. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaeth M, Weichold K, & Silbereisen RK, 2015. The development of leisure boredom in early adolescence: Predictors and longitudinal associations with delinquency and depression. Developmental Psychology, 51(10), 1380–1394. 10.1037/a0039480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Morris AS, 2001. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 83–110. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.L83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer D, Hartman CA, Pruim RHR, Mennes M, Heslenfeld D, Oosterlaan J, Faraone SV, Franke B, Buitelaar JK, & Hoekstra PJ, 2017. The interaction between 5-HTTLPR and stress exposure influences connectivity of the executive control and default mode brain networks. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 11(5), 1486–1496. 10.1007/s11682-016-9633-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hooff MLM, & van Hooft EAJ, 2016. Work-related boredom and depressed mood from a daily perspective: The moderating roles of work centrality and need satisfaction. Work and Stress, 30(3), 209–227. 10.1080/02678373.2016.1206151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AR, Sibley MH, Musser ED, Campez M, Bubnik-Harrison MG, Meinzer MC, & Yeguez CE, 2019. Relational impairments, sluggish cognitive tempo, and severe inattention are associated with elevated self-rated depressive symptoms in adolescents with ADHD. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(3), 289–298. 10.1007/s12402-019-00293-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2011). WASI-II: Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. PsychCorp. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, Ugueto AM, Langer DA, & Hoagwood KE, 2011. Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 369–380. 10.1037/a0023307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, & Spencer T, 1997. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with early onset substance use disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(8), 475–482. 10.1097/00005053-199708000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, McBurnett K, Bukstein O, McGough J, Greenhill L, Lerner M, … & Lynch JM (2006). Multisite controlled study of OROS methylphenidate in the treatment of adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 160, 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zendarski N, Sciberras E, Mensah F, & Hiscock H, 2017. Early high school engagement in students with attention/deficit hyperactivity disorder. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 127–145. 10.1111/bjep.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shuai L, Yu H, Wang Z, Qiu M, Lu L, Cao X, Xia W, Wang Y, & Chen R, 2020. Acute stress, behavioural symptoms and mood states among school-age children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102077. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman BJ, 2002. Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. 10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]