Abstract

Background:

Whether exposure to a single general anaesthetic (GA) in early childhood causes long-term neurodevelopmental problems remains unclear.

Methods:

PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library were searched from inception to October 2019. Studies evaluating neurodevelopmental outcomes and prospectively enrolling children exposed to a single GA procedure compared to unexposed children were identified. Outcomes common to at least three studies were evaluated using random effects meta-analyses.

Results:

Full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ), the parentally-reported Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Total, Externalizing, and Internalizing Problems scores, and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) scores were assessed. Of 1644 children identified, 841 who had a single exposure to GA were evaluated. CBCL problem scores were significantly higher (i.e. worse) in exposed children: mean score difference (CBCL Total: 2.3 [95% CI 1.0 – 3.7] p=0.001, CBCL Externalizing: 1.9 [95% CI 0.7 – 3.1] p=0.003, and CBCL Internalizing Problems: 2.2 [95% CI 0.9 – 3.5] p=0.001. Differences in BRIEF were not significant after multiple comparisons adjustment. FSIQ was not affected by GA exposure. Secondary analyses evaluating the risk of these scores exceeding predetermined clinical thresholds found that GA exposure was associated with increased risk of CBCL Internalizing behavioural deficit (risk ratio [RR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.08 – 2.02, p=0.016) and impaired BRIEF executive function (RR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.23 – 2.30, p=0.001).

Conclusion:

Combining results of studies utilizing prospectively collected outcomes showed that a single GA exposure was associated with statistically significant increases in parent reports of behavioural problems with no difference in general intelligence.

Keywords: anaesthetic neurotoxicity, paediatric anaesthesia, meta-analysis, neurodevelopment, systematic review

Exposure of young animals to clinically-utilized general anaesthetic drugs produces neurodegeneration and later problems with learning, memory, and behaviour.1 Clinical studies have also evaluated long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed to anaesthesia.2–8 However, there is significant variation in the studies with regard to study design, patient populations, and neurodevelopmental outcomes assessed, hampering their interpretation. This heterogeneity stems from challenges including inability to randomise children needing surgery to a non-anaesthetic control group, difficulty in accounting for underlying comorbid conditions in children needing surgery, and the need to assess outcomes many years after the exposure. As a result, most studies of anaesthetic neurotoxicity are observational and use pre-existing datasets.2–5 Prior meta-analyses of these retrospective studies have reported increased neurodevelopmental deficits in anaesthetic-exposed children.9,10 However, the underlying studies included outcomes that may not be the most sensitive for evaluating neurodevelopment after anaesthetic exposure and often lacked clinical data regarding pre-exposure and peri-operative factors that could affect neurodevelopment. This lack of clinical data is problematic as children with major congenital anomalies or intraoperative complications may be included in the anaesthetic exposed group, potentially biasing the results and complicating interpretation of these studies.

This systematic review and meta-analysis compares long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with and without exposure to a single episode of general anaesthesia during a predefined study period. While well-conducted randomised controlled trials (RCT) typically provide effect estimates that are less susceptible to bias than non-randomised studies, the inclusion of observational studies that appropriately control for confounding may be beneficial.11 In order to address the limitations of previously published meta-analyses, only RCTs and non-randomised studies of children who were prospectively enrolled and tested were included. This was done because these studies were designed to include the most sensitive outcomes for evaluating neurodevelopment after anaesthesia exposure and also allowed for review of clinical data in an attempt to minimise confounding.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Columbia University Vagelos Medical Center (New York, NY, USA) as exempt from requiring written/informed consent. A systematic review with a meta-analysis was performed adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Checklists.12 The review protocol was not registered in an online database.

Study design and search strategy

The systematic review was performed identifying all published studies evaluating cognitive function after exposure to general anaesthesia or surgery in children <18 yr old. The criteria and search strategy searching PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library was published by Clausen and colleagues identifying 67 English language studies published prior to June 16th, 2017.13 In the present study, an update using the same search criteria save for minor differences in formatting of search terms was performed to identify any additional studies published from June 17th, 2017 until October 16th, 2019 (Appendix1 in Supplement). This methodology of utilizing results from a previously published systematic review was performed to allow for a more efficient review of new evidence.14

Study selection and data extraction

The population of interest was children exposed to a single general anaesthetic during a predefined study period using contemporary general anaesthetic medications and monitoring. Studies with children exposed predominantly to halothane were excluded as that medication is no longer available in most anaesthetic practices. After broadly identifying all studies evaluating cognitive function after exposure to general anaesthesia or surgery in children, additional criteria were applied in order to focus on relevant RCTs and non-randomizsed studies with prospectively collected neurodevelopmental outcomes:

Inclusion criteria:

Studies must evaluate neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed to a single general anaesthetic during a defined study period compared to children unexposed to general anaesthesia.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes must be prospectively assessed in exposed and unexposed children who are at least school-aged, defined in this study as 5 yr of age or older, in order to allow for more accurate cognitive assessment.

Exclusion criteria:

Studies that only evaluated short-term perioperative cognitive outcomes such as delirium or anxiety.

Studies focusing specifically on children with major chronic conditions (congenital cardiac or other major congenital condition, extreme prematurity, etc.). Children in these studies have significant clinical heterogeneity and may have severe baseline medical issues, complicating interpretation of these studies.

Studies that met these additional criteria were reviewed, and all primary and secondary outcome data were considered. Any prospectively assessed neurodevelopmental outcome that was measured by the same instruments and common to at least three studies were included in the meta-analysis. While there is no lower limit of studies needed for a meta-analysis, when only two studies are included, there is a potential for increased risk of Type I error in the setting of heterogeneity between studies.15 Two reviewers (CI, WJ), independently assessed title, abstract and full text for eligibility using Covidence software (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Conflicts were resolved through consensus, and if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer (DOW). The same reviewers extracted the data from these studies.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Critical appraisals were conducted using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs and the ROBINS-I for non-randomised studies.16–18 Response options for the Cochrane risk of bias instrument was “low” or “high”, while response options for the ROBINS-I were “low”, “moderate”, “serious”, or “critical”. Two reviewers (CI, WJ), independently assessed each study, with conflicts resolved through consensus or, if necessary, discussion with a third reviewer (GL).

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis evaluated all eligible neurodevelopmental outcome scores as continuous variables. The consistency of outcome scores between studies were evaluated by calculating Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics for each outcome. Each of the outcome scores were then evaluated using random-effects models. An overall meta-analysis for each outcome was performed by pooling summary data from any outcome used in three or more studies. Publication bias could not be evaluated due to the limited number of available studies.19 All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) and figures generated using GraphPad Prism version 8.1.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For the primary analysis, Holm-Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons.20

Secondary analysis

A secondary analysis was performed evaluating the parentally reported outcomes after dichotomizing the scores using pre-specified clinical cut-offs. For CBCL or BRIEF, scores surpassing a threshold of >60 were >1 standard deviation from the standardized mean score and considered to be a clinically significant deficit, as used in prior studies.7,8 Additional data were requested from study authors as necessary to perform this analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

Following review of all published paediatric studies prospectively evaluating cognitive function after exposure to general anaesthesia, one identified study using included outcomes did not independently report scores for children with single vs multiple anaesthetic exposures.21 The authors were contacted to obtain scores for the children with single exposures, but the data could not be retrieved. The results from this study however were included in a separate sensitivity analysis.

Subgroup analysis of parent reported outcomes based on blinding status

A criticism of studies using parentally reported outcome measures is that knowledge of their child’s exposure to general anaesthesia could bias parents to give their children worse scores if parents believe that general anaesthesia is detrimental. A subgroup analysis was therefore performed using data from the GAS trial in which about half the parents reported being blinded from knowing whether their child received general anaesthesia or regional anaesthesia.6 In this analysis, the parentally reported outcome scores were stratified by blinding status to determine if group differences based on type of anaesthetic used were primarily reported by unblinded parents, with blinded parents reporting no difference. This data was evaluated in multiple ways including as per protocol or intention to treat, and also used multiple imputation as per the original GAS trial analysis.

Results

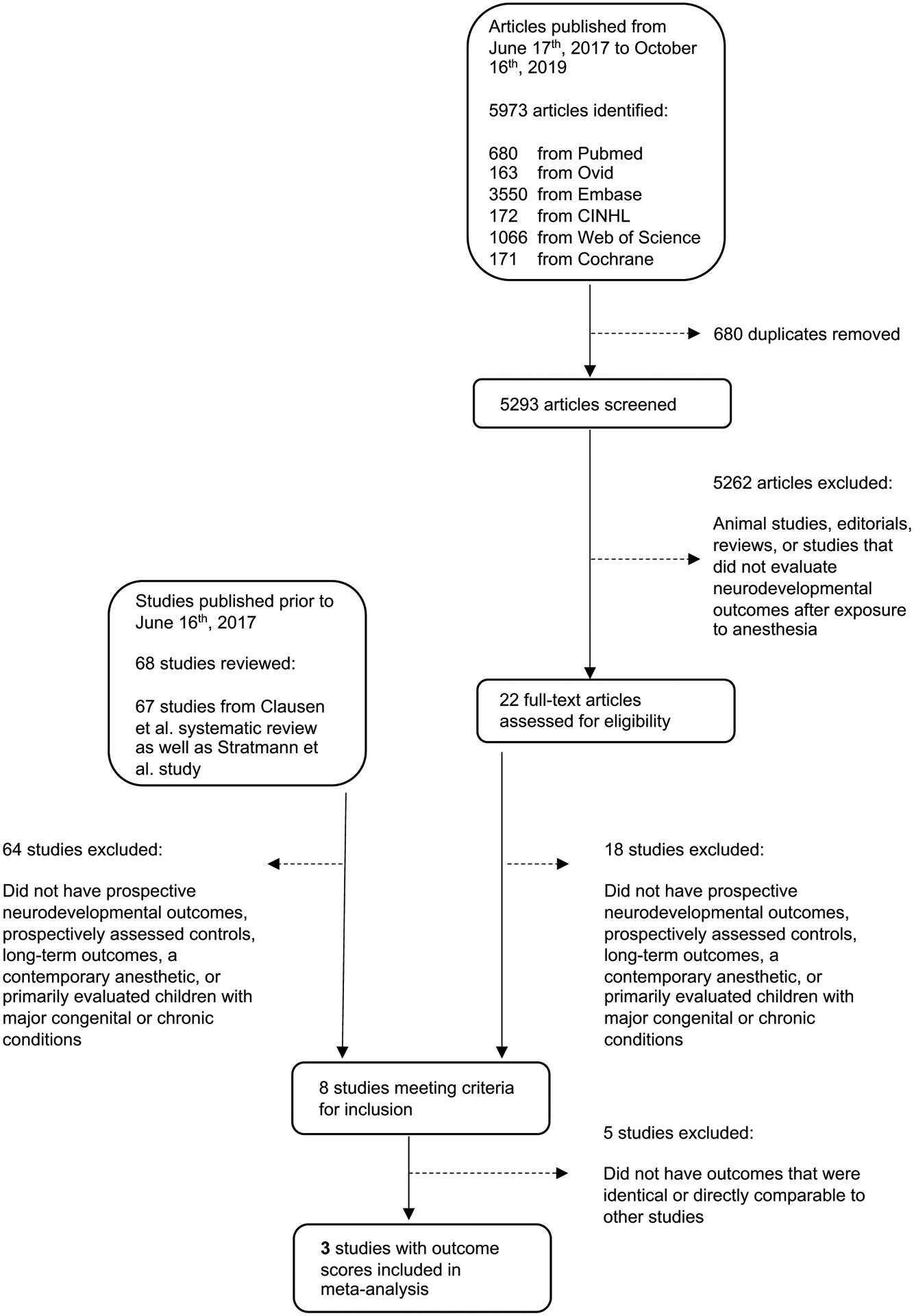

The systematic review identified 5,293 studies published between June 17, 2017 and October 16, 2019 after removal of duplicates. Of these, 22 studies evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes after exposure to general anaesthesia or surgery in children. Clausen and colleaguesref performed an extensive review which excluded all animal studies. As a result, one notable study by Stratmann and colleagues21 was missed, likely because it included data from animals as well as humans. With inclusion of that additional study, there were a total of 68 studies of neurodevelopmental outcomes after exposure to general anaesthesia or surgery in children prior to June 16, 2017 and 22 studies from June 17, 2017 until October 16, 2019, for a total of 90 studies of anaesthetic neurotoxicity (Figure 1). After applying additional inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify studies that assessed prospectively collected neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed to a contemporary general anaesthetic, a total of eight studies remained7,8,21–27 (Supplemental Table1).

Figure 1:

Diagram of the Study Selection Process for the Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Outcomes evaluated

In reviewing the eight eligible studies, five outcome scores were identified that were reported in at least three studies: Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Total Problems, Externalizing Problems, and Internalizing Problems scores, the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) Global Executive Composite score, and Full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ)(Table 1). For the FSIQ, two of the studies used the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) to assess FSIQ,7,8 while one study used the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, third edition (WPPSI-III).6 For the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) Global Executive Composite, one of the studies used the preschool version.6 For FSIQ and BRIEF, the scores used were appropriate for the age of the study population. Given the similarities between the FSIQ as measured by the WASI vs. the WPPSI-III, and Global Executive Composite score as measured by the BRIEF vs. the BRIEF preschool version, they were considered to be the same instruments for the purposes of the meta-analysis. In interpreting the parentally reported outcome scores, higher scores represent worse behaviour (CBCL Externalizing Problems), increased emotional distress (CBCL Internalizing Problems) and more impaired executive function (BRIEF Global Executive Composite).

Table 1:

Neurodevelopmental outcomes evaluated in the eligible studies

| Measure | Sun et al. (PANDA)7 | Warner et al. (MASK)8 | McCann et al. (GAS)22 | Taghon et al.23 | Bakri et al.24 | Khochfe et al.25 | Warner et al. (OTB Study)26 | Zhang et al.27 | *Stratmann et al.21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIEF GEC | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| CBCL Ext | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| CBCL Int | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| CBCL Total Problems | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| CPT2 number commissions | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| DKEFS TMT condition 1 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| DKEFS TMT condition 2 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| DKEFS TMT condition 3 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| DKEFS TMT condition 4 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| DKEFS TMT condition 5 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Grooved Pegboard dominant hand | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Grooved Pegboard nondominant hand | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| WASI FSIQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| WASI Matrix Reasoning | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| WASI Vocab | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| ABAS-II General Adaptive Composite score | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| NEPSY-II Speeded naming | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| NEPSY-II Word Generation | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| ABAS-II Conceptual Composite score | ✓ | ||||||||

| ABAS-II Practical Composite score | ✓ | ||||||||

| ABAS-II Social Composite score | ✓ | ||||||||

| CVLT-C Total Trials 1–5 (Verbal memory) | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Comprehension of instructions | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Delayed Memory for Faces | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Memory for Faces | ✓ | ||||||||

| WASI Block design | ✓ | ||||||||

| WASI Performance IQ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| WASI Similarities | ✓ | ||||||||

| WASI Verbal IQ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| WISC-IV Coding (Processing Speed) | ✓ | ||||||||

| WISC-IV Digit Span | ✓ | ||||||||

| Beery: Motor Coordination | ✓ | ||||||||

| Beery: VMI | ✓ | ||||||||

| Boston Naming Test | ✓ | ||||||||

| CBCL ADHD Problems | ✓ | ||||||||

| CLDQ Math Scale | ✓ | ||||||||

| CLDQ Reading Scale | ✓ | ||||||||

| CPT2 Detectability | ✓ | ||||||||

| CPT2 Hit Reaction Time | ✓ | ||||||||

| CPT2 Hit Reaction Time std error | ✓ | ||||||||

| CPT2 number omissions | ✓ | ||||||||

| CPT2 Variability | ✓ | ||||||||

| CTOPP: Rapid Naming Composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| DKEFS Expressive language composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| DKEFS Tower test Total Achievement Score | ✓ | ||||||||

| DKEFS Verbal Fluency: Category fluency | ✓ | ||||||||

| Grooved Pegboard Fine motor composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| Judgment of Line Orientation | ✓ | ||||||||

| Veery: Visual perception | ✓ | ||||||||

| Visual-spatial abilities composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| WASI Matrix Vocab | ✓ | ||||||||

| WCST: Perseverative errors | ✓ | ||||||||

| WCST: Perseverative responses | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Attention/concentration Index | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Delayed verbal recall composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Design Memory subtest | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Design Recognition subtest | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Story Memory Delay Recall | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Story Memory Recognition | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Verbal Learning Delay Recall | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Verbal learning Recognition | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Verbal memory index | ✓ | ||||||||

| WRAML-2 Verbal recognition composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| CMS Numbers | ✓ | ||||||||

| CMS Word Lists I | ✓ | ||||||||

| CMS Word Lists II | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Affect Recognition | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Auditory Attention | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Design Copy | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Fingertip tapping repetitions | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Fingertip tapping sequences | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Inhibition | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Memory for Names | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Sentence Repetition | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Statue | ✓ | ||||||||

| NEPSY-II Theory of Mind | ✓ | ||||||||

| WIAT-II Numerical Composite | ✓ | ||||||||

| WIAT-II Spelling | ✓ | ||||||||

| WIAT-II Word reading | ✓ | ||||||||

| WPPSI-III FSIQ | ✓ | ||||||||

| WPPSI-III Performance IQ | ✓ | ||||||||

| WPPSI-III Processing Speed score | ✓ | ||||||||

| WPPSI-III Verbal IQ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Go/no go task | ✓ | ||||||||

| CBCL 1 1/2–5 years | ✓ | ||||||||

| DSM 4th edition (3 point scale) | ✓ | ||||||||

| Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) | ✓ | ||||||||

| OTB | ✓ | ||||||||

| RCPM-IO | ✓ | ||||||||

| Color recollection | ✓ | ||||||||

| Spatial recollection | ✓ | ||||||||

| Color familiarity | ✓ | ||||||||

| Spatial familiarity | ✓ |

Study included in sensitivity analysis

Study characteristics

Three studies contributed data for the FSIQ, BRIEF, and CBCL outcome scores. The General Anaesthesia or Awake-regional Anaesthesia in Infancy (GAS) trial enrolled children scheduled for inguinal hernia repair (mean age ~70 days) and randomised them to receive either general anaesthesia with sevoflurane, or regional anaesthesia with spinal or caudal blocks with neurodevelopmental evaluation at 5 yr of age.6 The two other studies relied on an “ambi-directional” observational approach, with children old enough to undergo prospective neuropsychological testing retrospectively identified as having been exposed to surgery and anaesthesia at ≤3 yr of age. The Pediatric Anesthesia NeuroDevelopment Assessment (PANDA) study7 included siblings discordant for exposure to hernia surgery with neurodevelopmental evaluation at 8 to 15 yr of age, and the Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) study8 included children undergoing a variety of surgical procedures with children singly or multiply exposed to general anaesthesia prior to age 3 yr propensity matched to unexposed children with neurodevelopmental evaluation at 8 to 12 or 15 to 20 yr.

In all three studies, these outcomes were evaluated as continuous variables and presented in each publication as mean differences between exposed and unexposed children with 95% confidence intervals around those differences.6–8 For the GAS trial, the results were evaluated in several different ways. For the purposes of this meta-analysis, the results from the multiple imputation per protocol analysis were used.6 For the MASK study, only data from children singly-exposed to anaesthesia were included.8

Risk of bias

All studies were at risk of bias with the GAS trial at risk due to incomplete blinding and loss to follow-up, while the PANDA and MASK studies were at risk due to confounding and selection bias (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

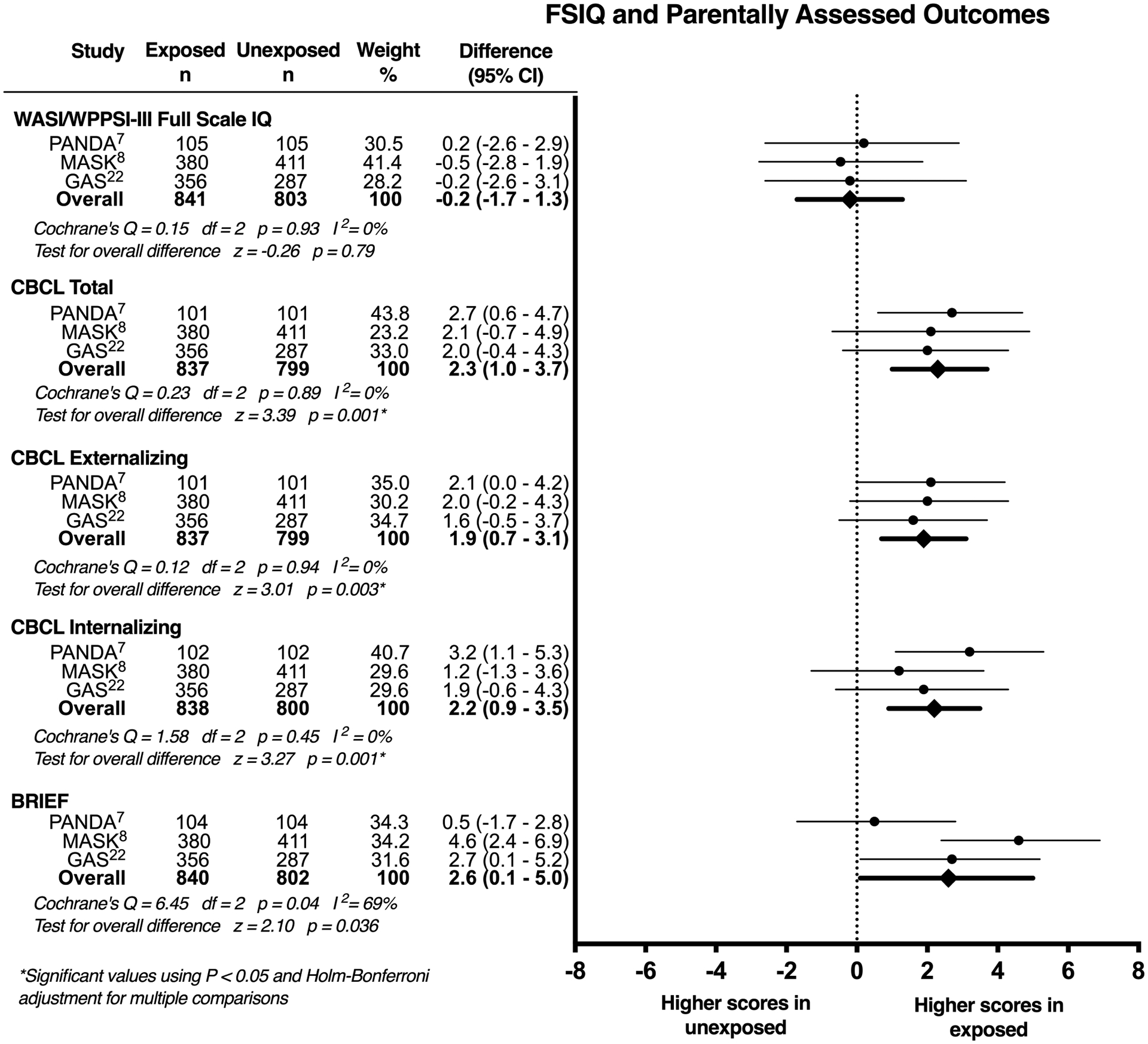

Outcomes after general anaesthetic exposure

Of 1644 children were included, outcome data were available for 837 to 841 children exposed to general anaesthesia and 799 to 803 children unexposed to general anaesthesia depending on the outcome score (Figure 2). Regarding heterogeneity in the outcomes between studies, FSIQ and CBCL scores were consistent between all three studies, with I2 = 0%, but substantial between-study heterogeneity among the BRIEF scores with I2 = 69% was seen. After pooling summary data from all three studies, the difference in mean scores between those exposed and unexposed to general anaesthesia was −0.2 (95% CI −1.7 – 1.3), p=0.79 for FSIQ, 2.3 (95% CI 1.0 – 3.7), p=0.001 for CBCL Total Problems, 1.9 (95% CI 0.7 – 3.1), p=0.003 for CBCL Externalizing Problems, 2.2 (95% CI 0.9 – 3.5), p=0.001 for CBCL Internalizing Problems, and 2.6 (95% CI 0.1 – 5.0), p=0.036 for BRIEF scores. After adjustment for multiple comparisons, the differences in all CBCL scores remained statistically significant, but differences in BRIEF scores were no longer significant.

Figure 2:

FSIQ and parent reported outcome scores in children with a single exposure to general anaesthesia vs. no exposure to general anaesthesia. CI: confidence interval; FSIQ: Full-scale intelligence quotient; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

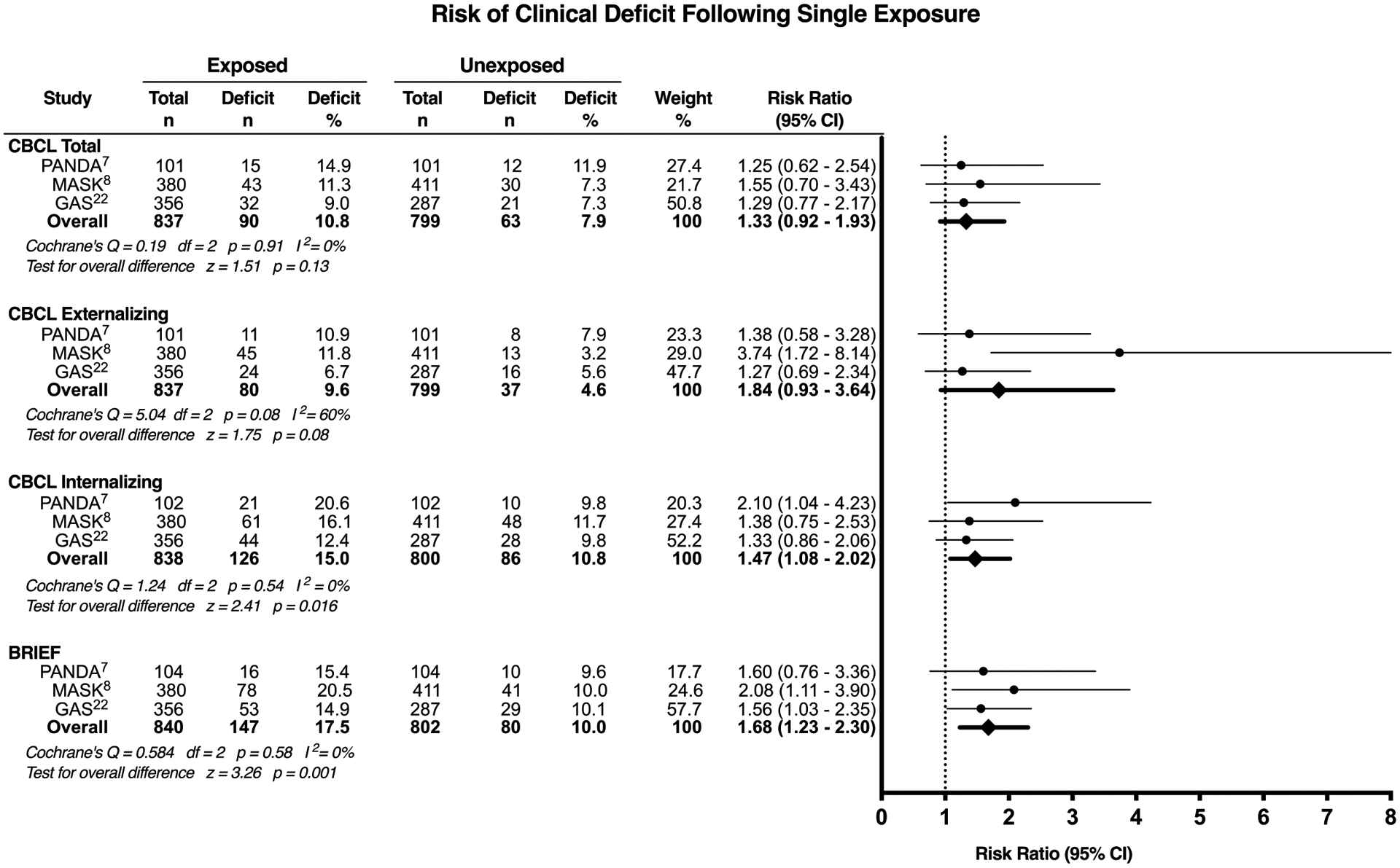

In the secondary analysis, the increased risk of the score exceeding a predetermined threshold for clinical deficit was evaluated, with a single exposure associated with an increased risk of subsequent CBCL internalizing behavioural deficit (risk ratio [RR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.08 – 2.02, p=0.016) and impaired executive function (RR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.23 – 2.30, p=0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Clinically significant deficit in parent reported outcome scores in children with a single exposure to general anaesthesia vs. no exposure to general anaesthesia. CI: confidence interval; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

In a sensitivity analysis, data from the Stratmann and colleagues article were added, which included 28 exposed and 28 unexposed children.21 Of the exposed children, 64% (n=18) received a single anaesthetic. Inclusion of the FSIQ and CBCL total scores from this study did not substantially alter the primary results (Supplemental Figure 1).

Parent reported outcomes according to blinding status

In the GAS trial, blinding to treatment assignment was achieved in 51% (n=256) of parents, while the remainder reported knowing the type of anaesthetic their child received. The proportion of blinded parents in the regional and general anaesthesia groups were also similar, with parental blinding in 51% (n=105) of children receiving regional anaesthesia, and 49% (n=118) of children receiving general anaesthesia. In blinded parents, the general anaesthetic exposed children had mean CBCL scores that were between 0.4 and 2.5 points higher, and BRIEF scores that were 1.3 to 1.6 points higher than the mean scores of children with a regional anaesthetic (Table 2). In unblinded parents, the general anaesthetic exposed children had mean CBCL scores that were between 0.5 and 1.8 points higher, and BRIEF scores that were 2.2 to 2.9 points higher than the mean scores of children with a regional anaesthetic.

Table 2:

Comparison of general anaesthetic vs. regional anaesthetic groups stratified by blinding status

| GA group | RA group | Difference in GA-RA (95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mean (SD) | n | mean (SD) | ||

| Blinded Parents | |||||

| CBCL Total | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 132 | 47 (12.6) | 100 | 45.4 (11.9) | 2.1 (−1.1 – 5.4) |

| PP complete case | 129 | 46.9 (12.2) | 97 | 45.4 (11.4) | 2 (−1.2 – 5.1) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 132 | 47 (12.6) | 124 | 45.7 (12.6) | 1.8 (−1.4 – 4.9) |

| ITT complete case | 129 | 46.9 (12.2) | 120 | 45.7 (12) | 1.6 (−1.5 – 4.6) |

| CBCL Externalizing | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 132 | 45.6 (11.8) | 100 | 45.1 (11.3) | 0.8 (−2.2 – 3.9) |

| PP complete case | 129 | 45.5 (11.5) | 97 | 45 (10.9) | 0.7 (−2.4 – 3.7) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 132 | 45.6 (11.8) | 124 | 45.2 (11.9) | 0.5 (−2.4 – 3.5) |

| ITT complete case | 129 | 45.5 (11.5) | 120 | 45.2 (11.4) | 0.4 (−2.5 – 3.3) |

| CBCL Internalizing | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 132 | 48.5 (12.8) | 100 | 46.5 (12.4) | 2.5 (−0.9 – 5.9) |

| PP complete case | 129 | 48.4 (12.4) | 97 | 46.5 (11.9) | 2.4 (−0.9 – 5.7) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 132 | 48.5 (12.8) | 124 | 46.7 (12.8) | 2.3 (−0.9 – 5.5) |

| ITT complete case | 129 | 48.4 (12.4) | 120 | 46.7 (12.2) | 2.2 (−1 – 5.3) |

| BRIEF | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 132 | 51.1 (14.4) | 100 | 49.9 (14.4) | 1.5 (−2.3 – 5.3) |

| PP complete case | 116 | 51 (12.5) | 90 | 49.5 (12.5) | 1.6 (−1.9 – 5.1) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 132 | 51.1 (14.4) | 124 | 50 (14.5) | 1.3 (−2.3 – 4.9) |

| ITT complete case | 116 | 51 (12.5) | 112 | 49.8 (13) | 1.3 (−2.1 – 4.7) |

| Unblinded Parents | |||||

| CBCL Total | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 118 | 46 (12.7) | 105 | 44.2 (12.3) | 1.1 (−2.2 – 4.4) |

| PP complete case | 116 | 45.9 (12.5) | 104 | 44.1 (12.2) | 1 (−2.3 – 4.3) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 118 | 46 (12.7) | 131 | 44.6 (12.5) | 0.7 (−2.4 – 3.9) |

| ITT complete case | 116 | 45.9 (12.5) | 129 | 44.5 (12.3) | 0.7 (−2.4 – 3.8) |

| CBCL Externalizing | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 118 | 45.7 (12.5) | 105 | 43.3 (10.8) | 1.8 (−1.3 – 4.9) |

| PP complete case | 116 | 45.6 (12.3) | 104 | 43.3 (10.7) | 1.7 (−1.4 – 4.8) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 118 | 45.7 (12.5) | 131 | 43.9 (11.8) | 1.2 (−1.8 – 4.2) |

| ITT complete case | 116 | 45.6 (12.3) | 129 | 43.9 (11.6) | 1.1 (−1.8 – 4.1) |

| CBCL Internalizing | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 118 | 47.4 (12.6) | 105 | 46.1 (12.9) | 0.5 (−2.9 – 3.9) |

| PP complete case | 116 | 47.3 (12.4) | 104 | 46.1 (12.9) | 0.5 (−2.9 – 3.9) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 118 | 47.4 (12.6) | 131 | 46.1 (12.9) | 0.6 (−2.5 – 3.8) |

| ITT complete case | 116 | 47.3 (12.4) | 129 | 46 (12.7) | 0.7 (−2.5 – 3.8) |

| BRIEF | |||||

| PP multiple imputation | 118 | 50.5 (14.6) | 105 | 47.3 (13.5) | 2.5 (−1.2 – 6.3) |

| PP complete case | 107 | 51 (14.1) | 95 | 47.3 (13) | 2.9 (−0.9 – 6.7) |

| ITT multiple imputation | 118 | 50.5 (14.6) | 131 | 47.6 (13.3) | 2.2 (−1.3 – 5.7) |

| ITT complete case | 107 | 51 (14.1) | 119 | 47.8 (12.7) | 2.6 (−1 – 6.1) |

Adjusted for gestational age at birth and country

PP: As per protocol analysis of data; ITT: Intention to treat analysis of data.

Discussion

We evaluated all prospectively assessed neurodevelopmental outcome data from prospectively designed studies comparing general anaesthetic exposed children to children not exposed to general anaesthesia up to October 2019. Studies included children exposed to anaesthesia at under 1 yr of age6 and under 3 yr of age7,8. Compared to children who did not receive general anaesthesia, children exposed to a single general anaesthetic had mean score differences in CBCL and BRIEF from 1.9 to 2.6 points worse than those in unexposed children, which in secondary analyses corresponded to a 47% increased risk of an internalizing behavioural deficit and a 68% increased risk of impaired executive function. No significant differences in FSIQ were found.

Parent reports of behaviour and executive function are standard and useful components of clinical neuropsychological evaluations as behaviour or emotional issues may not manifest in the structured setting of a neuropsychological assessment but are evident in other settings such as home or school.28 The finding of more problems in children exposed to general anaesthesia is consistent with studies of non-human primates exposed to anaesthetics that reported behavioural problems after early anaesthetic exposure.29 It is also consistent with some retrospective analyses suggesting that children exposed to anaesthesia may be more likely to develop later behavioural problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.3,30–32 Thus, measures of behaviour may be of particular interest in the search for a potential phenotype associated with anaesthesia exposure. One criticism of parent reports is that if parents know that their child was exposed to general anaesthesia, they may be biased towards reporting more problems. The results of the GAS trial, an RCT with blinding to treatment assignment maintained for about half of participants, provide insight into this possibility. If bias was the factor causing more problems to be reported in anaesthetic exposed children, worse scores might primarily be seen in unblinded parents, with blinded parents reporting no difference. Although the small sample size precluded a formal analysis, there was little evidence that blinding status was consistently associated with differences between parent-reported scores in general and regional anaesthesia groups since similar results were seen in both groups.

The clinical relevance of these score differences (~ 0.2 standard deviations or 2 points on CBCL and BRIEF) identified in children undergoing short single procedures is unclear, particularly on an individual level. However, on a broader scale, if these worse behavioural scores are actually caused by anaesthesia, given that 500,000 to 1 million children are exposed to anaesthesia in early childhood each year in the US alone, these differences may have increased importance on a population level.33,34 To further evaluate the clinical significance of these score differences, we evaluated the percentage of children crossing a predetermined clinical threshold for deficit. A single general anaesthetic exposure significantly increased the risk of developing internalizing behavioural problems by 47% and impaired executive function by 68%. Whether these score differences represent a shift for the entire population of general anaesthetic exposed children or only a small group of vulnerable children is unclear. If an entire normal distribution is shifted to the right by 0.2 standard deviations, the percentage of children with scores above 1 standard deviation from the mean (equivalent to >60 on the CBCL or BRIEF) would increase by approximately 34%. This is similar to the increased risk found in this study, and therefore could suggest that all children were affected. However, given the uncertainty around these estimates, it is also possible that this shift in scores represents a more severe impact on a vulnerable group of children in combination with some children who were unaffected.

A limitation of this analysis is the heterogeneity amongst the included studies in design, control condition examined, and analytic methods used. The age at evaluation also differed, with children from the GAS study evaluated at age 5 yr, while children from the MASK and PANDA studies were evaluated at 8 to 20 yr of age. While meta-analyses commonly include studies with methodological differences, heterogeneity poses a threat to the validity of combining the results of these studies. Heterogeneity was also seen between studies in BRIEF scores despite consistency in FSIQ and CBCL scores. Another limitation is that children were characterized as being exposed to general anaesthesia based on exposure during the assessment period defined in each study. While balanced between exposed and unexposed groups, some children in all of these studies were exposed to general anaesthesia after the study assessment period, which could bias against finding differences if these later exposures affected neurodevelopment.

Conclusions

Combining the results of studies utilizing common prospectively collected outcomes shows that a single exposure to general anaesthesia in early childhood was associated with statistically significant increases in parent reports of behavioural problems, but no difference in general intelligence. While there was heterogeneity in study methodology, interestingly mean score differences for behavioural problems in the included studies were strikingly similar. Further research is needed to evaluate the clinical significance of these differences and to identify potentially vulnerable children. The limitations of this analysis mean that these are provisional conclusions that require further research for confirmation.

Supplementary Material

Editor’s key points.

Whether exposure to a single exposure to general anaesthesia in early childhood causes long-term neurodevelopmental problems is unclear despite incriminating animal evidence.

A meta-analysis was performed of prospective studies evaluating neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed to a single general anaesthetic compared to unexposed children. Exposure to general anaesthesia was associated with increases in parental reports of behavioural problems with no difference in general intelligence.

Further research is needed to evaluate the clinical significance of these differences and to identify potentially vulnerable children.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the GAS consortium, and the MASK and PANDA study collaborators for providing additional unpublished data needed to complete the analyses.

Funding Source

CI was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) under award number R01HS026493. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Vutskits L, Xie Z. Lasting impact of general anaesthesia on the brain: mechanisms and relevance. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016;17:705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glatz P, Sandin RH, Pedersen NL, Bonamy AK, Eriksson LI, Granath F. Association of Anesthesia and Surgery During Childhood With Long-term Academic Performance. JAMA Pediat. 2017;171:e163470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ing C, Ma X, Sun M, et al. Exposure to Surgery and Anesthesia in Early Childhood and Subsequent Use of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Medications. Anesth Analg 2020. [update] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Leary JD, Janus M, Duku E, et al. A Population-based Study Evaluating the Association between Surgery in Early Life and Child Development at Primary School Entry. Anesthesiolog. 2016;125:272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, et al. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology 2009;110:796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCann ME, de Graaff JC, Dorris L, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age after general anaesthesia or awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled equivalence trial. Lancet 2019;393:664–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun LS, Li G, Miller TL, et al. Association Between a Single General Anesthesia Exposure Before Age 36 Months and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Later Childhood. JAMA 2016;315:2312–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner DO, Zaccariello MJ, Katusic SK, et al. Neuropsychological and Behavioral Outcomes after Exposure of Young Children to Procedures Requiring General Anesthesia: The Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) Study. Anesthesiology 2018;129:89–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimaggio C, Sun LS, Ing C, Li G. Pediatric Anesthesia and Neurodevelopmental Impairments: A Bayesian Meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2012;24(4):376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Du L, Du Z, Jiang H, Han D, Li Q. Association between childhood exposure to single general anesthesia and neurodevelopment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort study. J Anesth. 2015;29(5):749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrier I, Boivin JF, Steele RJ, et al. Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(10):1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clausen NG, Kahler S, Hansen TG. Systematic review of the neurocognitive outcomes used in studies of paediatric anaesthesia neurotoxicity. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(6):1255–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris SR, Langkamp DL. Predictive value of the Bayley mental scale in the early detection of cognitive delays in high-risk infants. J Perinatol. 1994;14(4):275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonnermann A, Framke T, Grosshennig A, Koch A. No solution yet for combining two independent studies in the presence of heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2015;34(16):2476–2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalton JE, Bolen SD, Mascha EJ. Publication Bias: The Elephant in the Review. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(4):812–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holm S A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stratmann G, Lee J, Sall JW, et al. Effect of general anesthesia in infancy on long-term recognition memory in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(10):2275–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCann ME, de Graaff JC, Dorris L, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age after general anaesthesia or awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10172):664–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taghon TA, Masunga AN, Small RH, Kashou NH. A comparison of functional magnetic resonance imaging findings in children with and without a history of early exposure to general anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(3):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakri MH, Ismail EA, Ali MS, Elsedfy GO, Sayed TA, Ibrahim A. Behavioral and emotional effects of repeated general anesthesia in young children. Saudi J Anaesth. 2015;9(2):161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khochfe AR, Rajab M, Ziade F, Naja ZZ, Naja AS, Naja ZM. The effect of regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia on behavioural functions in children. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38(4):357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warner DO, Chelonis JJ, Paule MG, et al. Performance on the Operant Test Battery in young children exposed to procedures requiring general anaesthesia: the MASK study. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122(4):470–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q, Peng Y, Wang Y. Long-duration general anesthesia influences the intelligence of school age children. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17(1):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW, Vannest KJ. Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC). In: Kreutzer JS, Caplan B, DeLuca J, eds. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. New York; London: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman K, Robertson ND, Dissen GA, et al. Isoflurane Anesthesia Has Long-term Consequences on Motor and Behavioral Development in Infant Rhesus Macaques. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(1):74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu D, Flick RP, Zaccariello MJ, et al. Association between Exposure of Young Children to Procedures Requiring General Anesthesia and Learning and Behavioral Outcomes in a Population-based Birth Cohort. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(2):227–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ing C, Sun M, Olfson M, et al. Age at Exposure to Surgery and Anesthesia in Children and Association With Mental Disorder Diagnosis. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(6):1988–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1053–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzong KY, Han S, Roh A, Ing C. Epidemiology of Pediatric Surgical Admissions in US Children: Data From the HCUP Kids Inpatient Database. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2012;24(4):391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi Y, Hu D, Rodgers EL, et al. Epidemiology of general anesthesia prior to age 3 in a population-based birth cohort. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28(6):513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.