Abstract

In a cohort of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccine recipients (n=1090), we observed that spike-specific IgG antibody levels and ACE2 antibody binding inhibition responses elicited by a single vaccine dose in individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (n=35) were similar to those seen after two doses of vaccine in individuals without prior infection (n=228). Post-vaccine symptoms were more prominent for those with prior infection after the first dose, but symptomology was similar between groups after the second dose.

mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), offer great promise for curbing spread of infection.1–3 Challenges to the supply chain have prompted queries around whether single rather than double dose administration may suffice for certain individuals, including those recovered from prior infection. Emerging immune data, including detectable presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and virus-specific T-cells, have suggested possible alternate vaccination strategies for previously infected individuals.4–6 Recent small studies have indicated that individuals with prior infection may have naturally-acquired immunity that could be sufficiently enhanced by a single rather than double dose of administered vaccine.7,8 To this end, we evaluated SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody responses following the first and second doses of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccine in a large and diverse cohort of healthcare workers. We compared the responses of individuals with confirmed prior infection to those of individuals without prior evidence of infection.

We enrolled healthcare workers from across a large academic medical center in Southern California. Vaccine recipients (n=1090) who provided at least one blood sample for antibody testing were aged 41.9±12.2 years, 60.7% female and 53.3% non-white (Table 1): 981 vaccine recipients, including 78 with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, provided baseline (pre-vaccine) samples, 525 (35 with prior infection) provided samples after dose 1, and 239 (11 with prior infection) provided samples after dose 2. A total of 217 individuals (10 with prior infection) provided blood samples at all 3 time points. Antibody levels were measured at 3 time points: before or up to 3 days after dose 1; within 7 to 21 days after dose 1, and within 7 to 21 after dose 2. Because the timing of the first blood draw for antibody testing could confound the association of spike glycoprotein-specific IgG [IgG(S-RBD)] with prior infection versus early vaccine response,9 we used nucleoprotein-specific IgG [IgG(N)] to denote prior SARS-CoV-2 exposure while recognizing a small potential for representing cross-reactivity with other coronaviruses. Given that the BNT162b2 vaccine delivers mRNA encoding only for spike protein, the expected elicited response is production of IgG(S-RBD) antibodies and not IgG(N) antibodies;10 furthermore, IgG(N) are also known to represent a durable marker and indicator of post-infectious status.11 Accordingly, we determined prior SARS-CoV-2 infection status and timing in relation to first vaccine date, based on concordance of data documented in health records, presence of any IgG(N) antibodies at baseline pre-vaccination testing, and the self-reported survey information collected. All cases of data discrepancy regarding prior SARS-CoV-2 infection status underwent manual physician adjudication, including medical chart review for evidence of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR or antibody testing that could have been performed by outside institutions or otherwise documented in the medical record.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort.

| Total | Pre-Vaccine | Post-Vaccine Dose 1 | Post-Vaccine Dose 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1090 | 981 | 525 | 239 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 41.89 (12.18) | 41.60 (12.05) | 43.66 (12.79) | 44.12 (12.65) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 509 (46.7) | 453 (46.2) | 263 (50.1) | 130 (54.4) |

| Black or African American | 36 (3.3) | 33 (3.4) | 22 (4.2) | 9 (3.8) |

| Asian | 300 (27.5) | 265 (27.0) | 154 (29.3) | 67 (28.0) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 29 (2.7) | 27 (2.8) | 14 (2.7) | 3 (1.3) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiple/Other | 139 (12.8) | 130 (13.2) | 58 (11.1) | 27 (11.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 75 (6.9) | 71 (7.2) | 14 (2.6) | 3 (1.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 139 (12.8) | 126 (12.8) | 55 (10.5) | 20 (8.4) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 881 (80.8) | 788 (80.3) | 460 (87.6) | 216 (90.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 70 (6.4) | 67 (6.8) | 10 (1.9) | 3 (1.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 362 (33.2) | 331 (33.7) | 159 (30.3) | 65 (27.2) |

| Female | 662 (60.7) | 587 (59.8) | 353 (67.2) | 168 (70.3) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 65 (6.0) | 62 (6.3) | 12 (2.3) | 5 (2.1) |

| Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection, n (%) | 86 (7.9) | 78 (8.0) | 35 (6.7) | 11 (4.6) |

| Antibody Levels, mean (%) | ||||

| Architect IgG Index (S/C) [IgG(N)] | 0.30 (0.86) | 0.25 (0.84) | 0.36 (0.90) | 0.34 (0.82) |

| Architect IgM Index (S/C) | 0.99 (2.41) | 0.26 (1.24) | 2.11 (4.11) | 3.38 (5.96) |

| Architect Quant IgG II (AU/mL) [IgG(S-RBD)] | 2801.04 (6159.27) | 103.90 (693.89) | 3183.38 (7299.73) | 24084.06 (16367.63) |

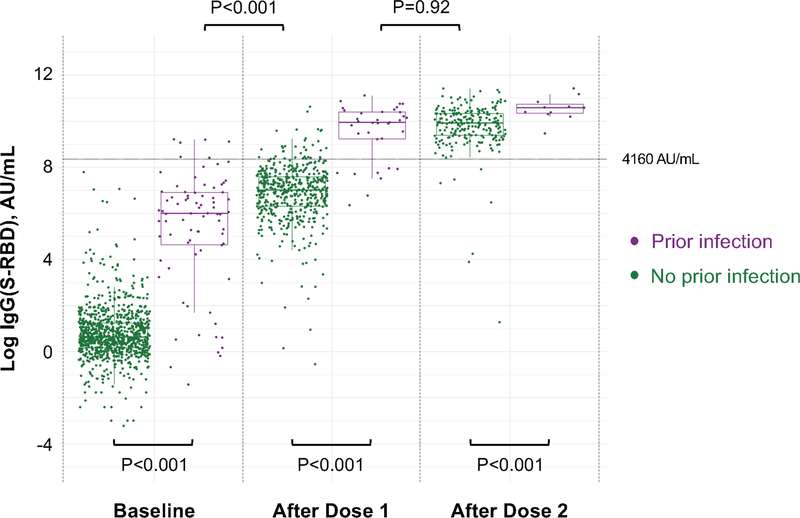

For both IgG(N) (representing response to prior infection) and IgG(S-RBD) (representing response to either prior infection or vaccine), as expected, individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection had higher antibody levels at all time points (P≤0.001) (Supplementary Tables 1–2 and Extended Data 1). Notably, IgG(S-RBD) levels were only slightly lower in previously infected persons at baseline when compared to infection naïve persons who had received a single vaccine dose (log median AU/mL [IQR], 6.0 [4.6, 6.9] vs 7.0 [6.3, 7.6], P<0.001). Moreover, IgG(S-RBD) levels were not significantly different between previously infected persons following a single dose and infection naïve persons who had received 2 doses (10.0 [9.2, 10.4] vs 9.9 [9.4, 10.3], P=0.92) (Figure 1). Similar results were found in a sensitivity analysis including only individuals who had antibody immunoassays performed at all 3 time points (Supplementary Tables 3–4). Specifically, those with prior infection had higher IgG(S-RBD) than those without prior infection at all time points. No difference in IgG(S-RBD) levels was detected between those with prior infection after one dose of vaccine compared with those without prior infection following two doses (10.2 [8.4, 10.5] vs 9.9 [9.4, 10.3], P=0.58).

Figure 1. IgG(S-RBD) Antibody Response to mRNA SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Persons With and Without Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection.

Box plots display the median values with the interquartile range (lower and upper hinge) and ±1.5-fold the interquartile range from the first and third quartile (lower and upper whiskers). We used two-sided Wilcoxon tests, without adjustment for multiple testing, to perform the following between-group comparisons: (1) infection naïve (n=903) and those with prior infection (n=78), both at baseline (P<0.001); (2) infection naïve (n=490) and those with prior infection (n=35), both following dose 1 (P<0.001); (3) infection naïve (n=228) and those with prior infection (n=11), both following dose 2 (P<0.001); (4) infection naïve (n=490) following dose 1 and those with prior infection (n=78) at baseline (P<0.001); and, (5) infection naïve (n=228) following dose 2 and those with prior infection (n=35) following dose 1 (P=0.92).

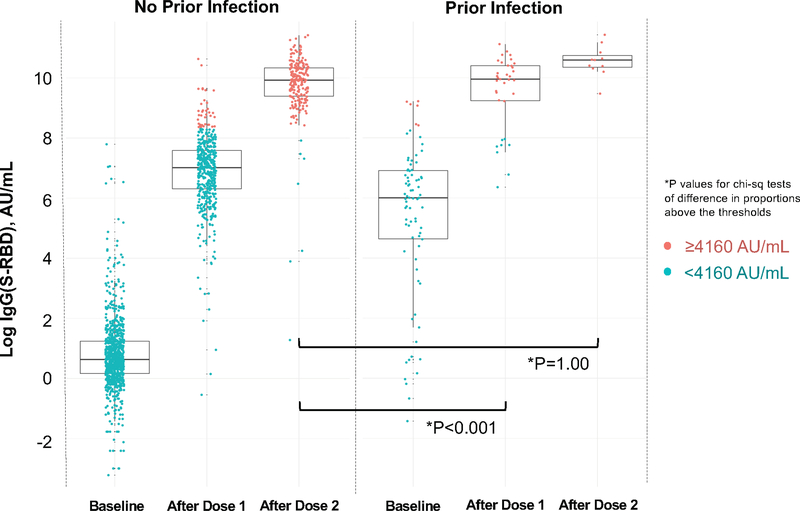

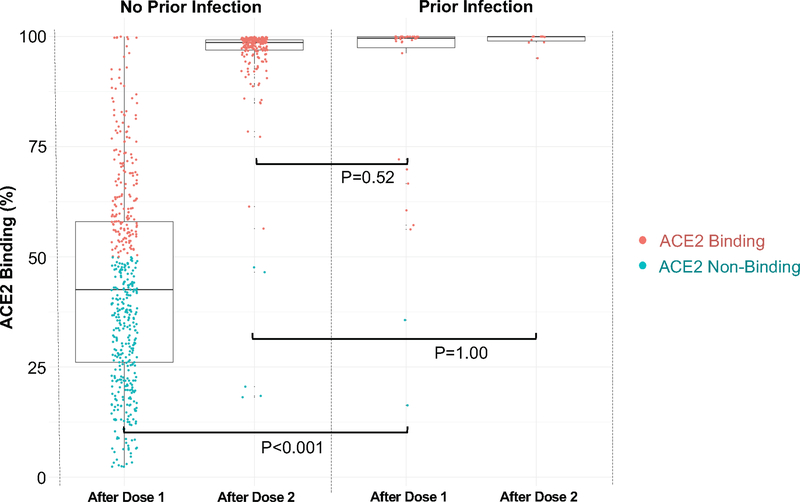

For surrogate measures of antibody neutralization, we examined IgG(S-RBD) levels at or above the 4160 AU/mL given this threshold corresponds to a 0.95 probability of obtaining a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) ID50 at a 1:250 dilution. Proportions of IgG(S-RBD) ≥4160 AU/mL were similar between previously infected individuals at baseline compared to infection naïve persons after a single dose (P=1.00). Notably, these proportions were lower in previously infected individuals after a single dose compared to infection naïve persons after 2 doses (P<0.001); there were no between-group differences after 2 doses (Supplementary Table 5 and Extended Data 2). We also used an ACE2 binding inhibition assay that correlates well with the SARS-CoV-2 PRNT methodology and exhibits a high correlation with the IgG(S-RBD) assay threshold (r2=0.95). We found that ACE2 binding inhibition was significantly higher among previously infected individuals than infection naïve participants after a single vaccine dose (94.3% vs 37.3%, P<0.001) with no between-group difference seen after the second dose (100.0% vs 97.8%, P=1.00). In time shifted analyses, there was no difference in ACE2 binding between participants with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection after a single dose compared with infection naïve participants following 2 doses (94.3% vs 97.8%, P=0.52) (Supplementary Table 6 and Extended Data 3).

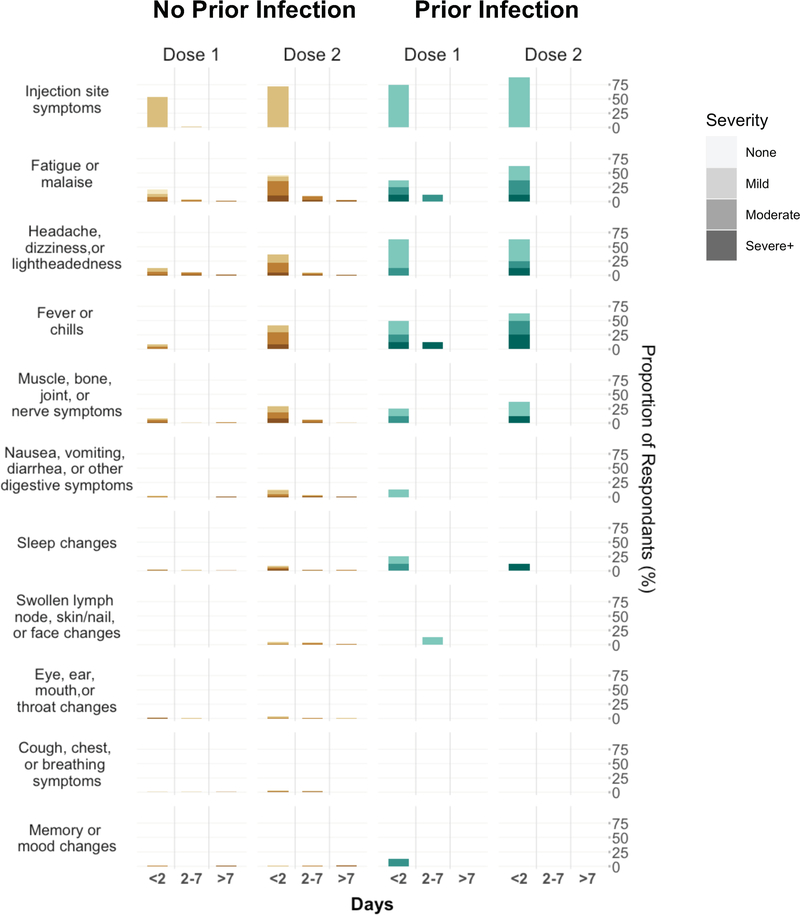

In parallel with antibody response analyses, we also examined post-vaccine symptomology (Supplementary Tables 7–11 and Extended Data 4). We observed that previously infected individuals experienced significant post-vaccine symptoms (i.e., reactogenicity) more frequently than infection naïve persons following dose 1 (36.8% vs 25.0%, P=0.03). However, there was no between-group difference in significant symptoms following dose 2 (51.3% vs 58.7%, P=0.26). In time shifted analyses, infection naïve persons had higher reactogenicity following dose 2 compared with previously infected persons following their first dose (58.7% vs 36.8%, P<0.001). Fever and chills were more common among previously infected vaccine recipients following the first dose, whereas infection naïve persons were more likely to experience headache, dizziness or lightheadedness following the second dose. In analyses of changes from dose 1 to dose 2, reactogenicity increased in frequency for infection naïve individuals (25.0% vs 58.7%, P<0.001) and less so in previously infected individuals (36.8% vs 51.3%, P=0.08).

Overall, we found that individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 developed vaccine-induced antibody responses following a single dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccine that were comparable to antibody responses seen after a two-dose vaccination course administered to infection naïve persons. Our findings in a large and diverse cohort of healthcare workers expand from the results of smaller studies that have indicated higher levels of anti-S antibodies at baseline, and after a single mRNA vaccine dose, in previously infected persons compared to those without prior infection.7,8,12,13 In a total cohort of over 1000 vaccine recipients, including several hundred with blood sampling following administered vaccine doses, we found that the anti-S antibody response following a single vaccine dose in previously infected individuals was comparable to the response seen after two doses in all vaccine recipients irrespective of prior infection status. We further assessed the neutralization potential of elicited antibodies using a high-throughput ACE2 inhibition neutralization surrogate assay; similar to findings from a smaller study that directly measured antibody neutralizing capacity in 59 volunteers,8 we found in our large cohort that a second vaccine dose did not offer previously infected persons a substantially greater benefit over a single dose in antibody neutralizing potential. As such, our data suggest that a single dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is sufficient for individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, not only when considering the response in anti-S antibody levels but also when examining results of an ACE2 inhibition assay indicating the potential neutralizing capability of elicited antibodies.

Limitations of our study include the 21-day timeframe within which antibodies were measured after each vaccine dose. Longer-term follow up can provide additional information regarding the putative duration of immunity acquired from receiving a single versus double dose of vaccine. Measures of T-cell responses can shed further light on how a single versus double dose of vaccine may be sufficient for augmenting T-cell memory in previously infected individuals.12 Further studies are needed to determine if a certain window for vaccination timing may be optimal to maximize efficacy as well as safety in previously infected individuals. Larger-sized cohorts are needed for sufficient statistical power to examine differences across demographic and clinical subgroups that are known to exhibit variation in antibody responses following vaccination.14–16 When neutralizing capacity was estimated using a conservative IgG(S-RBD) threshold of >4160 AU/mL, the single-dose response in previously infected persons was numerically similar, albeit statistically significantly lower than the antibody response following two doses in infection naïve persons; when applying this conservative threshold of >4160 AU/mL, which correlates with a 95% probability of high neutralizing antibody titer,17 statistical comparisons are susceptible to the influence of extreme values in the context of smaller-sized subgroups. Importantly, there was no significant difference in the surrogate measure of ACE2 binding inhibition between persons with and without prior infection in time shifted analysis following vaccine dose 1 and dose 2, respectively. Notwithstanding methodological differences between examining IgG(S-RBD) levels and assays of ACE2 binding inhibition, these surrogate measures suggest materially similar levels of achieved neutralization capacity. Some variation in antibody responses may also be related to heterogeneity within previously infected individuals, including in timing and severity of prior illness. While circulating antibody levels alone are not definitive measures of immune status, serial measures of the serological response to either natural or inoculated exposures are known to correlate well with effective protective immunity18 and our results indicate their potential utility in guiding vaccine deployment strategies for both previously infected and infection naïve persons.

Our results offer preliminary evidence in support of a middle ground between public health motivated and immunologically supported vaccine strategies. If validated, an approach that involves providing a single dose of vaccine to persons with a confirmed history of SARS-COV-2 infection along with an on-time complete vaccine schedule for infection naïve persons could maximize the benefit of a limited vaccine supply.

METHODS

We collected plasma samples from a cohort of healthcare workers who received Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination at our medical center in Southern California.1 Serological testing for antibodies to the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit of the viral spike protein [IgG (S-RBD)], and antibodies targeting the viral nucleocapsid protein [IgG(N)], was performed at Abbott Labs (Abbott Park, IL) using the SARS-CoV-2 IgG II assay and SARS-CoV-2 IgG assay, respectively. Antibody levels were measured at 3 time points: before or up to 3 days after dose 1; within 7 to 21 days after dose 1, and within 7 to 21 after dose 2. We considered an IgG(N) S/C of ≥1.4 as denoting seropositive status due to prior SARS-CoV-2 exposure based on a previously established cutoff.2

For assessing potential response of neutralizing antibodies, we considered a conservatively high IgG(S-RBD) threshold of 4160 AU/mL as a correlate of neutralization. The 4160 AU/mL threshold has been shown to corresponded to a 0.95 probability of obtaining a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) ID50 at a 1:250 dilution as a representative high titer; as such, we examined the proportion of vaccine recipients who achieved this IgG(S-RBD) threshold3 following administration of each dose of vaccine. Furthermore, as a high-throughput method of directly assessing viral inhibition (or neutralization), we also employed a research ACE2 binding inhibition assay to measure the ability of detected IgG(S-RBD) antibodies to inhibit viral spike protein from binding to ACE2 receptors. This ACE2 binding inhibition assay, which we applied to the post-vaccination samples, is known to correlate well with SARS-CoV-2 PRNT methodology and exhibits a high correlation with the IgG(S-RBD) assay threshold employed (r2=0.95).

All participants provided survey data on prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptoms experienced after each vaccine dose. We used an online RedCap4,5 questionnaire to survey all participants regarding post-vaccination symptoms, including presence or absence of distinct symptom types as well as the severity and duration of any symptom experienced. We administered the questionnaire 8 days after each vaccine dose. We defined a post-vaccine symptom reaction as significant if reported as a non-injection site symptom that was: (i) moderate to severe in degree and lasting <2 days, or (ii) of any severity and lasting >2 days. We determined prior SARS-CoV-2 infection status and timing in relation to first vaccine date, based on concordance of data documented in health records, presence of IgG(N) antibodies at baseline pre-vaccination testing, and the self-reported survey information collected. All cases of data discrepancy regarding prior SARS-CoV-2 infection status underwent manual physician adjudication, including medical chart review for evidence of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR or antibody testing that could have been resulted by outside institutions.

Statistical Analyses

We compared antibody levels and symptom responses between persons with and without a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. We analyzed data at both matched and shifted time points, including measures for persons with a prior infection (at baseline and following dose 1) compared to infection naïve persons (following dose 1 and dose 2). We log-transformed non-normally distributed values. For comparing between-group continuous values, we used the non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. For comparing between-group proportions (e.g., values above a given threshold), we used two-sided Chi-square tests with the Yates correction. We performed sensitivity analyses for those participants with immunoassays at all 3 time points. We conducted all statistical analyses using R (v3.6.1) and considered statistical significance as a two-tailed P value <0.05. All participants provided written informed consent, and all protocols were approved by the Cedars-Sinai institutional review board.

Extended Data

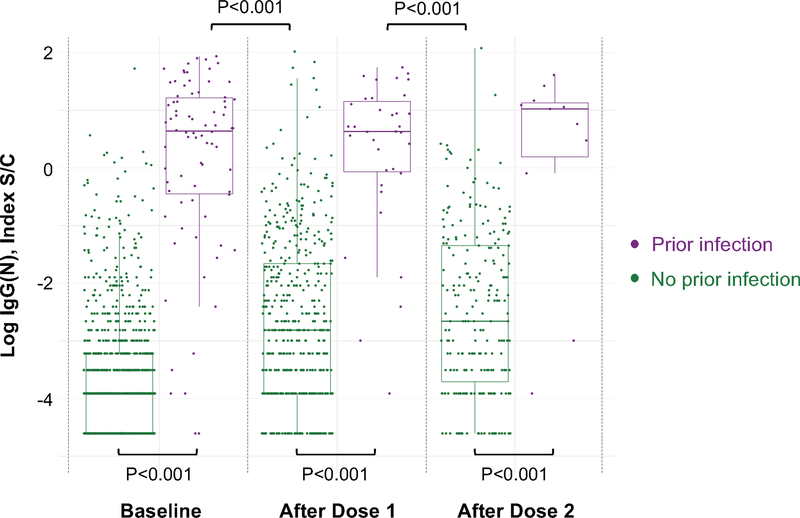

Extended Data 1. Anti-Nucleocapsid Protein IgG Antibody Response to mRNA SARS- CoV-2 Vaccination in Persons With and Without Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Box plots display the median values with the interquartile range (lower and upper hinge) and ±1.5-fold the interquartile range from the first and third quartile (lower and upper whiskers). We used two-sided Wilcoxon tests, without adjustment for multiple testing, to conduct the following between-group comparisons: (1) infection naïve (n=903) and those with prior infection (n=78), both at baseline (P<0.001); (2) infection naïve (n=490) and those with prior infection (n=35), both following dose 1 (P<0.001); (3) infection naïve (n=228) and those with prior infection (n=11), both following dose 2 (P<0.001); (4) infection naïve (n=490) following dose 1 and those with prior infection (n=78) at baseline (P<0.001); and, (5) infection naïve (n=228) following dose 2 and those with prior infection (n=35) following dose 1 (P<0.001).

Extended Data 2. Anti-Spike Receptor Binding Domain IgG Antibody Response to mRNA SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Persons With and Without Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection: Values Above and Below 4160 AU/mL.

Box plots display the median values with the interquartile range (lower and upper hinge) and ±1.5-fold the interquartile range from the first and third quartile (lower and upper whiskers). We used two-sided Chi-Square tests with the Yate’s correction, without adjustment for multiple testing, to conduct the following between-group comparisons: (1) infection naive (n=221) following dose 2 and those with prior infection (n=27) following dose 1 (P<0.001); and, (2) infection naive (n=221) and those with prior infection (n=11), both following dose 2 (P=1.00).

Extended Data 3. ACE2 Antibody Binding Capacity in Persons With and Without Prior SARS- CoV-2 infection: Values Above and Below 50%.

Box plots display the median values with the interquartile range (lower and upper hinge) and ±1.5- fold the interquartile range from the first and third quartile (lower and upper whiskers). Colors denote values above and below the 50% neutralizing threshold. We used two-sided Wilcoxon tests, without adjustment for multiple testing, to conduct the following between-group comparisons: (1 ) infection naïve (n=490) and those with prior infection (n=35), both following dose 1 (P<0.001); (2) infection naïve (n=228) and those with prior infection (n=11), both following dose 2 (P=1.00); and, (3) infection naïve (n=228) following dose 2 and those with prior infection (n=35) following dose 1 (P=0.52).

Extended Data 4. Post-Vaccination Symptoms in Persons With and Without Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Bar graphs display the frequency and severity of symptoms reported following each dose of vaccine administered, by prior infection status.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all the front-line healthcare workers in our healthcare system who continue to be dedicated to delivering the highest quality care for all patients. We would like to thank the following people for their collective effort: Francesca Paola Aguirre, MD; Kawsar Ahmad; Christine M. Albert, MD, MPH; Mona Alotaibi, MD; Allen Andres, PhD; Moshe Arditi, MD; Ani Balmanoukian, MD; Courtney Becker; James Beekley, MPH; Diana Benliyan; Anders H. Berg, MD, PhD; Eva Biener-Ramanujan; Aleksandra Binek, PhD; Patrick Botting, MSPH; Gregory J. Botwin, BS; David Casero; Cindy Chavira, MBA; Blandine Chazarin Orgel; Mingtian Che; Peter Chen, MD; Vi Chiu, MD, PhD; Dain Choi; Melanie Chow; Cathie Chung; MD; Cailin Climer; Bernice Coleman, PhD, RN; Sandra Contreras, MPH; Rachel Coren, MPH; Donna Costales, RN; Wendy Cozen, DO, MPH; Tahir Dar; Jennifer Davis; Tod Davis; Philip Debbas; Jacqueline Diaz; Jessica Dos Santos, Matthew Driver, MPH; Keren R. Dunn, CIP; Rebecca Ely, RN; Mark Faries, MD; Barbara Fields, RN; Jane C. Figueiredo, PhD; Lucia Florindez, PhD; Joslyn Foley; Norma Fontelera; Sarah Francis, RN; Jeffrey A. Golden, MD; Alma Gonzalez; Helen S. Goodridge, PhD; Jeanette Gonzalez; Jonathan D. Grein, MD; Gena Guidry, MSc; Omid Hamid, MD; Mary Hanna; Shima Hashemzadeh; Mallory Heath, MLS; Ergueen Herrera; Amy Hoang, MS; Lilith Huang; Khalil Huballa; Quyen Hurlburt, RN; Shehnaz K. Hussain, PhD; Carissa A. Huynh; Justina Ibrahim; Ugonna Ihenacho, MPH; Mohit Jain, MD, PhD; Harneet Jawanda, MD; Mary Jordan, Ashley Jose-Isip; Sandy Joung, MHDS; Michael Karin, PhD; Elizabeth H. Kim, MHDS; Linda Kim, PhD; Michelle M. Kittleson, MD, PhD; Edward Kowalewski; Catherine N. Le, MD; Nicole A. Leonard, JD, MBA; Yin Li; Yunxian Liu, PhD; John Lloyd; Eric Luong, MPH; Anzhelya Makaryan; Bhavya Malladi; Danica-Mae Manalo, David Marshall, DNP, JD; Angela McArdle; Dermot P.B. McGovern, MD, PhD; Inderjit Mehmi, MD; Darlene Mejia; Gil Y. Melmed, MD; Larry Mendez; Emebet Mengesha; Akil Merchant, MD; Noah Merin, MD, PhD; Kathrin S. Michelsen, PhD; Gail Milan, RN; Peggy B. Miles, MD; Jordan Miller; Margo Minissian, PhD; Romalisa Miranda-Peats, MPH; Seyedeh Elnaz Mirzadeh; April Moore; Pamela Moore; Janette Moreno, DNP; Angela Mujukian, MD; Nathalie Nguyen, MPH; Trevor Trung Nguyen; Magali Noval Rivas, PhD; Fleury Nsole Bitghe, PhD; Michelle Offner, NP; Jillian Oft, MD; Elmar Park; Eunice Park; Vipul Patel, PharmD; Connor Phebus; Lawrence Piro, MD; Lauren R. Polak, JD; Ashley Porter; Matthew Puccio; Koen Raedschelders, PhD; V. Krishnan Ramanujan, PhD; Rocio Ramirez; Gerardo Ramirez; Mohamad Rashid, MBChB; Karen Reckamp, MD; Kylie Rhoades; Celine E. Riera, PhD; Richard V. Riggs, MD; Alejandro Rivas; Jackie Robertson; Maria Salas; Michelle Schafieh, MS; Rita Shane, PharmD; Sonia Sharma, PhD; Cristina Simons, RN; Muhammad Soomar, MBA; Sarah Sternbach; Nancy Sun, MPS; Clive Svendsen, PhD; Brian Tep; Rose O. Tompkins, MD; Warren G. Toutellotte, MD, PhD; Rocio Vallejo; Christy Velasco; Mectabel Velasquez; Kirstin Washington; Kristopher Wentzel, MD; Shane White; Benjamin Wong; Melissa Wong, MD; Mahendra Yatawara, MBA; Rachel Zabner, MD; Cindy Zamudio, MD; Yi Zhang, MD, MS; Lisa Zhou; Patrick Zvara, MS.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (JEE; MW; NS; SC), the Erika J Glazer Family Foundation (JEE; MW; NS; JEVE; SC), the F. Widjaja Family Foundation (IP; JGB), the Helmsley Charitable Trust (IP; JGB), and NIH grants U54-CA260591 (JEE; JFB; MW; JEVE; JGB; SC; KS) and K23-HL153888 (JEE).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

JCP, ECF, and JLS work for Abbott Diagnostics, a company that performed the serological assays on the biospecimens that were collected for this study. The remaining authors have no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Requests for de-identified data may be directed to the corresponding authors (JGB, SC, KS) and will be reviewed by the Office of Research Administration at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center prior to issuance of data sharing agreements. Data limitations are designed to ensure patient and participant confidentiality.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baden LR, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 384, 403–416 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack FP, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 383, 2603–2615 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omer SB, Yildirim I & Forman HP Herd Immunity and Implications for SARS-CoV-2 Control. JAMA 324, 2095–2096 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melgaco JG, Azamor T & Ano Bom APD Protective immunity after COVID-19 has been questioned: What can we do without SARS-CoV-2-IgG detection? Cell Immunol 353, 104114 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey RA, et al. Real-world data suggest antibody positivity to SARS-CoV-2 is associated with a decreased risk of future infection. medRxiv, 2020.2012.2018.20248336 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumley SF, et al. Antibody Status and Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Health Care Workers. New England Journal of Medicine 384, 533–540 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krammer F, et al. Antibody Responses in Seropositive Persons after a Single Dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine. N Engl J Med (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saadat S, et al. Binding and Neutralization Antibody Titers After a Single Vaccine Dose in Health Care Workers Previously Infected With SARS-CoV-2. JAMA (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterlin D, et al. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci Transl Med 13(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahin U, et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature 586, 594–599 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seow J, et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nature Microbiology 5, 1598–1607 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prendecki M, et al. Effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection on humoral and T-cell responses to single-dose BNT162b2 vaccine. Lancet (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manisty C, et al. Antibody response to first BNT162b2 dose in previously SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. Lancet (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soiza RL, Scicluna C & Thomson EC Efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines in older people. Age and Ageing (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi T, et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature 588, 315–320 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abu Jabal K, et al. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel, December 2020 to January 2021. Euro Surveill 26(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant Assay User Manual. in 6S60 (Abbott Laboratories, Diagnostics Division, December 2020).

- 18.Wang Z, et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. bioRxiv, 2021.2001.2015.426911 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

METHODS ONLY REFERENCES

- 1.Ebinger JE, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11, e043584 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chew KL, et al. Clinical evaluation of serological IgG antibody response on the Abbott Architect for established SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Microbiol Infect 26, 1256.e1259–1256.e1211 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant Assay User Manual. in 6S60 (Abbott Laboratories, Diagnostics Division, December 2020).

- 4.Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42, 377–381 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PA, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 95, 103208 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Requests for de-identified data may be directed to the corresponding authors (JGB, SC, KS) and will be reviewed by the Office of Research Administration at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center prior to issuance of data sharing agreements. Data limitations are designed to ensure patient and participant confidentiality.