Abstract

The technique of color EM that was recently developed enabled localization of specific macromolecules/proteins of interest by the targeted deposition of diaminobenzidine (DAB) conjugated to lanthanide chelates. By acquiring lanthanide elemental maps by energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM) and overlaying them in pseudocolor over the conventional greyscale TEM image, a color EM image is generated. This provides a powerful tool for visualizing subcellular component/s, by the ability to clearly distinguish them from the general staining of the endogenous cellular material. Previously, the lanthanide elemental maps were acquired at the high-loss M4,5 edge (excitation of 3d electrons), where the characteristic signal is extremely low, and required considerably long exposures. In this paper, we explore the possibility of acquiring the elemental maps of lanthanides at their N4,5 edge (excitation of 4d electrons), which occurring at a much lower energy-loss regime and contains significantly greater total characteristic signal owing to the higher inelastic scattering cross-sections at the N4,5 edge. Acquiring EFTEM lanthanide elemental maps at the N4,5 edge instead of the M4,5 edge, provides ~4x increase in signal-to-noise and ~2x increase in resolution. However, the interpretation of the lanthanide maps acquired at the N4,5 edge by the traditional 3-window method, is complicated due to the broad shape of the edge profile and the lower signal-above-background ratio. Most of these problems can be circumvented by the acquisition of elemental maps with the more sophisticated technique of EFTEM Spectrum Imaging (EFTEM SI). Here, we also report the chemical synthesis of novel second generation DAB lanthanide metal chelate conjugates that contain 2 lanthanide ions per DAB molecule in comparison with 0.5 lanthanide ion per DAB in the first generation. Thereby, four-fold more Ln3+ per oxidized DAB, would be deposited providing significant amplification of signal. This paper applies the color EM technique at the intermediate-loss energy-loss regime to three different cellular targets, namely using mitochondrial matrix-directed APEX2, histone H2B-Nucleosome and EdU-DNA. All the examples shown in the paper are single color EM images only.

INTRODUCTION

The Electron Microscope (EM) has gained immense popularity within the scientific community since its invention1, partly because in addition to providing for the acquisition of high resolution images, it also has the ability to simultaneously investigate the chemical/elemental composition of the sample. The elemental composition of the sample is primarily obtained either by Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) or Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS), with the latter having higher sensitivity and resolution2–4. The EELS technique has been applied in materials science to map elements with single atom sensitivity5–7 and in biological science to detect and quantify many endogenous elements 8–11. The EELS technique can be applied either in the Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) mode, generally referred to as the Energy Filtered TEM (EFTEM) 12–16 or in the Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) mode, referred to as STEM-EELS or EELS Spectrum-Imaging17–22. Although EFTEM mode has lower sensitivity than STEM-EELS, it provides larger fields of view, at least an order of magnitude larger, typically 105 – 107 pixels in comparison to 103 – 105 pixels in STEM-EELS10,17. For certain biological applications, a more encompassing field of view is just as important as either resolution or sensitivity, as is the case for the application of color EM electron probes to simultaneously label multiple cellular proteins/organelles in cells23–25. In the method that we developed, the localization of the multiple targeted molecules was achieved by the sequential deposition of specific lanthanide chelates conjugated to diaminobenzidine, which were selectively oxidized by orthogonal photosensitizers / peroxidases23. The core-loss or high-loss (M4,5 edge) elemental map/maps of the lanthanides obtained by the EFTEM mode were then overlaid in pseudo-color onto a conventional electron micrograph to create color EM images23,26,27.

The M4,5 core-loss edge for the lanthanides occurs at an energy loss > 800 eV. At these energy loss regions, the elemental signal is an extremely small fraction of the total incident beam3, requiring exposure times exceeding several minutes to acquire an elemental map. Such long exposures lead to poor image quality primarily due to specimen drift28, which can be somewhat offset, by taking a series of EFTEM images at shorter exposure times and then using drift correction to align them into a single image28–32. In additional to the aforementioned drift correction strategy, we demonstrated that using a Direct Detection Devices (DDD) instead of the traditional phosphor-based scintillator imaged by a photo-sensitive Charge Coupled Device (CCD) to obtain EFTEM maps provided significant improvements to signal-to-noise (SNR) and spatial resolution30. The proof of concept, of the inherent advantages of directly detecting electrons for spectroscopy, versus photo-conversion in a scintillator, was first demonstrated by Egerton, but he had to limit routine use in this mode due to the excessive beam damage33. It was only recently that beam-hardened CMOS Direct Detection Devices (DDD) able to operate continuously for months on a 300 KV TEM without significant beam damage were invented34–41. Recently, other labs have also started to use DDD, primarily for STEM-EELS, to improve the spectral resolution and SNR42–44.

However, in spite of these advances in EFTEM elemental mapping, we are fundamentally limited by the total intensity available at the high energy loss regions, which decreases exponentially with the increase in energy loss, in the so called Power Law form3. Alternatively, lanthanides also have a relatively strong N4,5 edge which occur at much lower energy loss regions, at 99 eV and 195 eV, in comparison to the M4,5 edge onset at 832 eV and 1588 eV for La and Lu respectively45. It has been suggested in the ‘EELS Atlas’, that for lanthanides the N4,5 edge can also be used for elemental mapping and microanalysis45. In continuation of our work of acquiring EFTEM elemental maps on the DDD, this paper discusses the advantages and pitfalls of obtaining elemental maps at the lower energy loss region (N4,5 edge) for biological samples specifically labeled with lanthanide conjugated diaminobenzidine. Technically, the energy loss region up to 50 eV is considered Low-Loss region, and the energy loss region > 50 eV is considered High-Loss region2. In this report to make a clear distinction between the M4,5 and N4,5 edge of the Lanthanides, we will refer to the M4,5 edge as the high-loss (HL) region and the N4,5 edge as the intermediate-loss (IL) region. To facilitate these studies and future applications of color-EM, we also report the synthesis and application of a novel second generation series of lanthanide chelates of DAB (Ln2-DAB) that deposit more metal upon DAB (photo)oxidation.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Materials

Reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Solvents and cell culture reagents were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) except where noted. Reactions were monitored by LC-MS (Ion Trap XCT with 1100 LC, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) using an analytical Luna C18(2) reverse-phase column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), acetonitrile/H2O (with 0.05% v/v CF3CO2H) linear gradients, 1 mL/min flow, and ESI positive or negative ion mode. Compounds were purified by silica gel column chromatography or alternatively by preparative HPLC using the above gradients and semi-preparative Luna C18(2) columns at 3.5 ml/min. UV−Vis absorption spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-2700 (Kyoto, Japan) spectrophotometer. A second generation of the lanthanide chelates of the DAB (Ln2-DAB) was chemically synthesized (see figure 1), which has 4 times the metal/lanthanide per DAB than the first generation (Ln-DAB2). For the detailed description of the chemical synthesis of Ln2-DAB, please refer to the supplementary section.

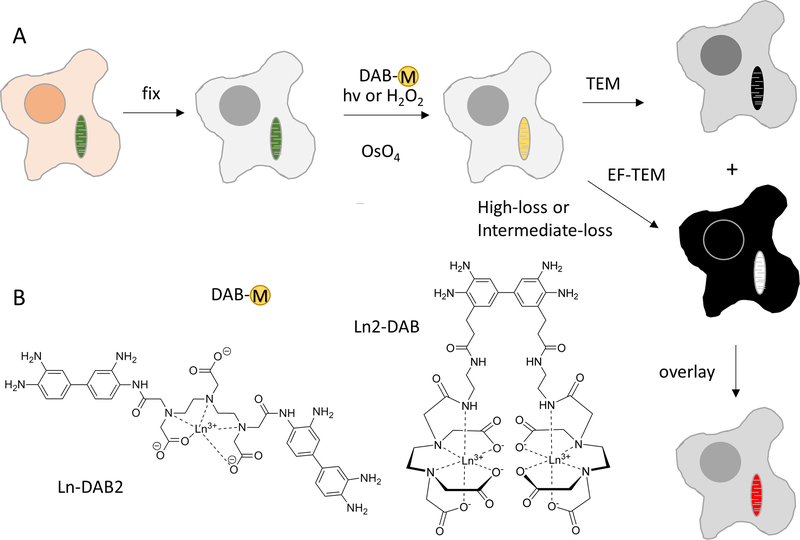

Figure 1.

a) Scheme of process for obtaining color-EM images of cells. Cells containing mitochondria labeled with a photosensitizer or peroxidase are fixed, incubated with a metal chelate of DAB, DAB-M and either irradiated or incubated with H2O2 respectively. Following osmification, embedding and sectioning, corresponding TEM and EF-TEM images are collected at element-distinctive high loss and intermediate loss energies. A pseudocolor overlay of these electron energy loss images on the osmium TEM yields a color-EM image of the cells. b) Chemical structures of DAB-lanthanide metal chelates; first generation, Ln-DAB2 and second generation, Ln2-DAB.

Samples

Three sets of samples were prepared of three different cellular targets, namely using mitochondrial matrix-directed APEX2, histone H2B-Nucleosome and EdU-DNA. Also, each of these 3 samples were labeled with DAB conjugated to three different lanthanide chelates: cerium, lanthanum and neodymium, respectively. The cerium and lanthanide DAB chelates were of second generation (Ln2-DAB) and the neodymium DAB chelate was of the first generation (Ln-DAB2).

Finally, a fourth set of samples were prepared, that served as a control, mitochondrial matrix-directed APEX2 labeled with unmodified DAB i.e. DAB without any lanthanide chelate bound to it. For detailed description of the preparation protocols for each of the sample, please refer to the supplementary section.

Specimen processing post secondary fixation.

Post fixative was removed from cells and were rinsed with 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4 (5×1min) on ice. Cells were washed with ddH2O at room temperature (5×1min) followed by an ice-cold graded dehydration ethanol series of 20%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100% (anhydrous) for one minute each and 2×100% (anhydrous) at room temperature for 1 minute each. Cells were infiltrated with one part Durcupan ACM epoxy resin (44610, Sigma-Aldrich) to one part anhydrous ethanol for 30 minutes, 3 times with 100% Durcupan resin for 1 hours each, a final change of Durcupan resin and immediately placed in a vacuum oven at 60°C for 48 hours to harden. Cells were identified, cut out by jewel saw and mounted on dummy blocks with Krazy glue. Coverslips were removed and 100 nm thick specimen sections were created with a Leica Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome and Diatome Ultra 45° 4mm wet diamond knife. Sections were picked up with 50 mesh gilder copper grids (G50, Ted Pella, Inc) and carbon coated on both sides with a Cressington 208 Carbon Coater for 15 second at 3.4 volts.

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed with a JEOL JEM-3200EF transmission electron microscope, equipped with a LaB6 source operating at 200 KV. The microscope is fitted with an in-column Omega filter after the intermediate lenses and before the projector lenses. The Cs and Cc aberration coefficients of the objective lens are 3.2 and 3.0 mm respectively. Conventional TEM and EFTEM images were collected using a condenser aperture of size 120 μm, an objective aperture of size 30 μm and entrance aperture of size 120 μm was used. Additionally, a selective area aperture of size 50 μm was used for acquisition of electron energy-loss spectra. The spectrometer energy resolution is 2 eV, measured as the FWHM of the zero-loss peak. Before the acquisition of elemental maps, the sample was pre-irradiated with a low beam dose of ~ 3.5 × 104 e-/nm2 for about 20 mins to stabilize the sample and to reduce contamination46.

The conventional TEM images and electron energy loss spectra were acquired on an Ultrascan 4000 CCD from Gatan (Pleasanton, CA). All the elemental maps, irrespective of whether it is a high-loss or an intermediate-loss map, were acquired on a DE-12 camera, which is a DDD from Direct Electron LP (San Diego, CA). The maps presented in this paper were acquired either by the traditional 3-window method3,47 or by the EFTEM Spectrum Imaging (EFTEM SI) technique48–51. For the 3-window method, to mitigate the effects of sample drift, instead of acquiring a single Pre-edge 1, Pre-edge 2 and Post-edge image for long exposures, a series of images of shorter durations for each of the pre-edge and the post-edge were acquired. These images were drift corrected and merged to form a single image pre-edge or post-edge image as the case may be. Also, instead of sequentially collecting the entire series of images at one energy window before proceeding to the next energy window, we acquired a set of images successively through all the energy windows and then acquire the next set through all the energy windows and so on. This interlaced acquisition reduces detrimental effects due to sample shrinkage/warping and high-tension instabilities over time, has been previously described in more detail23. The acquisition of both the 3-window method and EFTEM SI was accomplished by writing a macro in Serial EM for the control DE-12 detector52. The high-loss EFTEM images were aligned using the Template Matching plug-in in ImageJ53 and the intermediate-loss EFTEM images were aligned using the filters and alignment routines of Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc). The elemental maps for the 3-window method was computed using the EFTEM-TomoJ plug-in of ImageJ54 and the elemental maps for the EFTEM SI was computed using the Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc). The EFTEM images were dark current subtracted only and not gain normalized to avoid the fixed pattern noise arising due to uncertainties in flat-fielding30. All the elemental maps presented in this paper, were acquired at the full resolution of the DE-12 detector with out any binning applied to them. The SNR of the elemental map was obtained by dividing the signal by the standard deviation of the background intensity55,56. The signal was calculated by subtracting the mean intensity of regions that contained the lanthanide from the mean intensity of regions that represented the background. Please see the supplementary section in this paper, for the detailed TEM and spectrometer acquisition parameters for each of the datasets presented.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

The method for color EM that we developed depends upon the sequential oxidative deposition of Ln-DAB2 (Figure 1), consisting of a single lanthanide ion, Ln3+ bound to the chelate (DTPA) conjugated to one of the amino groups of two diaminobenzidine molecules23 by two of its carboxylate groups. To deposit more lanthanide per oxidized DAB, we synthesized Ln2-DAB (Figure 1B), by a multi-step synthesis (Suppl. Figure 1) from 3,3’-dinitrobenzidine by bromination to the 5,5’-dihalo derivative, followed by Heck reaction with ethyl acrylate. BOC-protection of the amino groups was necessary to avoid their intramolecular cyclization with the ortho acrylic esters. Catalytic hydrogenation of acrylic and nitro groups, and saponification of the ethyl ester gave the resulting diacid that was coupled to N-aminoethyl-EDTA via an intermediate bis-NHS ester, to give the BOC-protected DAB derivative conjugated to two EDTA chelates. Acid deprotection and titration with Ce3+ or Ln3+ gave the final product, Ln2-DAB, in which 2 lanthanide ions are bound per DAB and would therefore deposit four-fold more Ln3+ per oxidized DAB than our first generation chelate, Ln-DAB2.

HEK293T tissue culture cells transiently transfected with the genetically-encoded peroxidase, APEX2 were fixed with 2 % glutaraldehyde and incubated with Ce2-DAB and H2O2 for 5 minutes until a faint darkening of the cells was visible by bright field microscopy. Followed by post-fixation with ruthenium tetroxide, RuO4, and then dehydrated, infiltrated, embedded and sectioned for TEM57. Previously, the EFTEM elemental maps for the lanthanide/s were obtained at their high-loss M4,5 edge, which were then overlaid in pseudo-color onto a conventional electron micrograph to create the so-called color EM (see figure 1)23.

The main drawback of obtaining elemental maps at the M4,5 high-loss region for the lanthanides, is that the total intensity is very low, and requires long exposures at relatively high dose and dose rates30. The background intensity I varies as a function of Energy Loss E, in the so-called power-law form I = AE-r, with values for parameters A and r being dependent on the experimental conditions3. The overall signal intensity drops exponentially with energy loss, reaching negligible levels for energy loss above 2000 eV, and which is the practical limit of the technique2. For example, it has been shown that only 5 × 10−5 fraction of the total incident electron dose contributed to the oxygen K edge (onset at 532 eV) for a sample of 40 nm amorphous ice58.

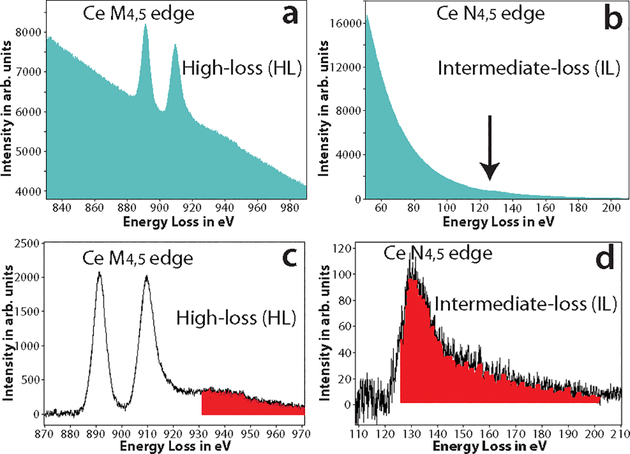

It has been suggested that for lanthanides, the N4,5 edge occurring at much lower energy-loss can also be potentially used for elemental mapping45. Figures 2a and 2b, show the raw spectra of the high-loss M4,5 edge region (onset at 883 eV) and the intermediate-loss N4,5 edge region (onset at 110 eV) for cerium, respectively. The N4,5 edge spectrum was acquired at a fraction of the dose of the M4,5 edge spectrum. The two distinct white lines of the M4,5 edge prominently stand out from the background in figure 2a, in contrast to the N4,5 edge which is barely discernible from the background as a small bump in figure 2b (see where the arrow points). In figure 2d, after the background subtraction, the saw tooth shape of the N4,5 edge is apparently evident.

Figure 2.

a) The raw spectrum acquired at the high-loss M4,5 edge of Ce, the two white line peaks with onset ~ 883 eV is clearly visible. b) The raw spectrum acquired at the intermediate-loss N4,5 edge of Ce, edge is barely visible as a small bump in the spectrum (see arrow direction). c) The background subtracted spectrum of (a), the M4,5 edge of Ce has a high signal-above-background ratio (SBR). The red shaded region shows the Ce extended energy-loss fine structure (EXELFS) bleed into the Pr edge. d) The background subtracted spectrum of (b), the N4,5 edge of Ce is now clearly visible, though with a much lower SBR. The red shaded region shows the part of the Ce edge that bleeds into the Pr edge.

As outlined above, the total intensity and the SNR are significantly better at the intermediate-loss region than at the high-loss region. However, for edge visibility and detection, in addition to a good SNR, it is important to have a good signal-above-background ratio (SBR)3. Therefore, if the concentration of the lanthanide metal is low, then in spite of the good SNR, the SBR of the N4,5 edge can be so low that it cannot be distinguished from the background, and obtaining an elemental map at this edge will not be feasible. Also, it should be emphasized that, unlike M4,5 which is distinct and well separated for the lanthanides, the N4,5 edge have significant overlap from edge of adjacent lanthanides. The instance, the N4,5 edge of Ce (onset at 110 eV) will be difficult to distinguish from N4,5 edge of Pr (onset at 113 eV), for a more detailed discussion on this please see the supplementary section ‘Criteria for edge selection in EFTEM elemental mapping’. However, this should not limit one to obtain EFTEM elemental maps at of lanthanides at N4,5 edge, when there is no overlapping edge from other lanthanides or endogenous elements in the sample.

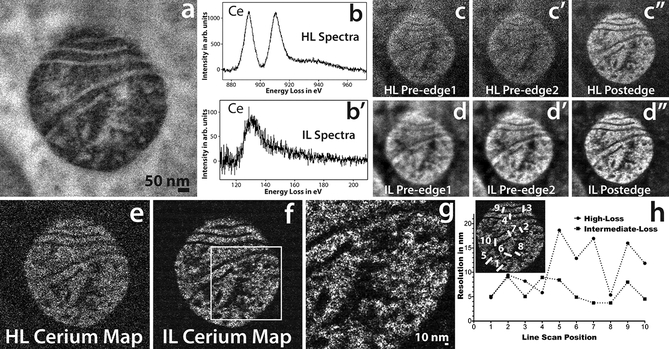

Figure 3a shows the conventional TEM image of mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 labeled with Ce2-DAB (second generation), figures 3b and 3b’ show the Ce spectra of high-loss M4,5 edge and the intermediate-loss N4,5 edge obtained on this region. A high-loss and an intermediate-loss elemental map were acquired on the sample, at the same dose rate and total dose (total dose for the high-loss acquisition was ~3% higher than the intermediate-loss acquisition). Figures 3c – c” and 3d – d” show the aligned and summed pre-edges and post-edge of the high-loss and intermediate-loss acquisition, respectively. It is very clear comparing these two sets of images that the pre-edges and the post-edge of the intermediate-loss show superior SNR and detail compared to the high-loss, as is expected. For the intermediate loss, the mitochondria in the post-edge image (figure 3d”) looks sharper than the pre-edge images (figure 3d and d’) because the mitochondrial matrix is loaded with Ce, and there is an increase in signal in this region relative to the background. However, it is for the high-loss that the difference between the post-edge image (Figure 3c”) and the pre-edge images (Figure 3c and 3c’) are most striking. The pre-edge images at high-loss are very blurry and noisy in comparison to the post-edge. The reason for this striking difference at the high-loss, is because of the much higher SBR of the M4,5 edge in comparison to the N4,5 edge. The SBR measured from the spectra for the signal and background integrated for a 30 eV window, is 1.0 and 0.3 for the high-loss and the intermediate-loss region, respectively.

Figure 3.

a) Conventional TEM image of mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 labeled with Ce2-DAB (second generation). b) The background subtracted high-loss spectrum acquired on the sample showing the M4,5 edge of Ce. b’) The background subtracted intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the sample showing the N4,5 edge of Ce. c, c’ and c”) The pre-edge1, pre-edge 2 and post-edge acquired for the high-loss M4,5 cerium edge at 815 eV, 855 eV and 899 eV respectively. Each energy-plane is a sum of 3 images acquired at an exposure of 100 sec/image. d, d’ and d”) The pre-edge1, pre-edge 2 and post-edge acquired for the intermediate-loss N4,5 cerium edge at 75 eV, 98 eV and 138 eV respectively. Each energy-plane is a sum of 29 images acquired at an exposure of 10 sec/image. The dose and dose rate was nearly the same for both the high-loss and intermediate-loss acquisitions. e) The High-loss Ce elemental map. f) The intermediate-loss Ce elemental map. g) Magnified view of the intermediate-loss Ce elemental map. h) The relative resolution comparison between the high-loss and the intermediate-loss Ce elemental map, measured by as the width of the intensity between 25 to 75% of the peak, for 10 different regions taken exactly the same position of the sample for both the maps (see the inset). To enhance image display, a Gaussian blur of radius 1 was applied to the conventional image and Gaussian blur of radius 2 was applied to the EFTEM images and maps.

Figure 3e and 3f, show the elemental maps computed by the 3-window method for the high-loss and the intermediate-loss, respectively. Both, of which were acquired as a series with shorter exposure/energy plane. The intermediate-loss was acquired at an exposure of 10 sec/image, the high-loss required much longer exposures of 100 sec/image to be able to accumulate enough signal, the complete details of the acquisition can be found in the supplementary section. The intermediate-loss elemental map is considerably sharper with a higher SNR, the SNR for the intermediate-loss map was 7.4 and for the high-loss map was 1.8, when calculated on the same region of the respective maps. It has been suggested, that in a plot of the intensity distribution across an edge in an image, the measure of the width of the intensity between 0.25 to 0.75 of its peak value, can be appropriated as the resolution59. The edge width being proportional to the beam broadening, due to the point spread function (PSF) of the imaging system. The region between the matrix and the cristae or the exterior background in the elemental maps (figures 3e and 3f), serve as an edge for the measurement of the achieved resolution in the intermediate-loss and high-loss map. It should be cautioned, that unlike grayscale conventional TEM/STEM images, where the intensity on either side of the edge is reasonably uniform, the pixel intensity of elemental maps vary significantly from one pixel to another because the intensity is proportional to the concentration of the element in that pixel. Therefore, measuring resolution from the edge step profile for elemental maps can be misleading. However, if the edge step profile is taken on precisely the same region of the image for both the high-loss and the intermediate-loss maps, then this can be used as a measure of relative degradation of resolution between the two maps. We obtained edge profiles at 10 precise same locations of the sample on both the maps, width (nm) of the intensity between 0.25 to 0.75 of its peak value, are shown in figure 3e.

The resolution from this calculation, for the high-loss and the low-loss maps are 11.0 ± 3.0 and 6.1 ± 2.0 nm, respectively. This is consistent with the magnified view of the intermediate-loss elemental map in Figure 3g, which clearly shows a particle of 4 nm (measured as FWHM) distinguishable from the background. We would like to emphasize, that this only implies that the resolution of the map acquired at the intermediate-loss region is ~ 1.8 times better than the map acquired at the high-loss region, and do not make any claim that these values are the absolute achievable resolution for the maps acquired at the respective energy-loss region.

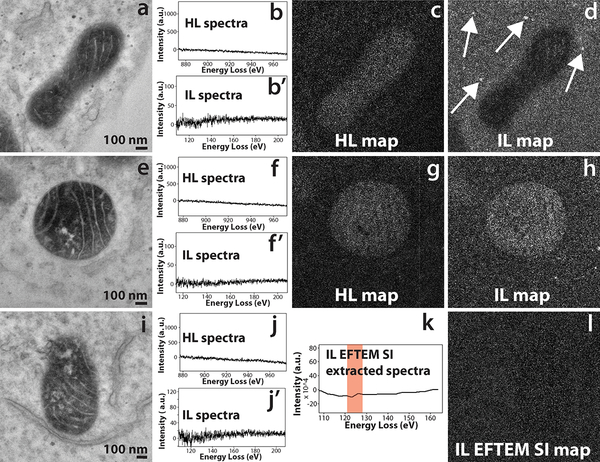

As demonstrated above, both the SNR and the resolution of the elemental map is somewhat better at intermediate-loss than at high-loss. The correctness of the power law background subtraction at the intermediate-loss is not well known. However, there can be some speculation that the contrast that is seen in the intermediate-loss elemental map may be density contrast of the heavily stained region containing cerium + ruthenium (secondary fixative), erroneously being interpreted as a cerium elemental map. On the other hand, for the high-loss 3-window method (energy-loss > 200 eV), the accuracy of the power-law background subtraction, and the optimization of the position and width of the energy-loss EFTEM images are well established14. Therefore, there needs to be additional validation that the contrast that is seen in the intermediate-loss Ce map, is indeed an elemental contrast. To test this hypothesis, a control sample was made, by labeling mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 with unmodified DAB (i.e., with no bound lanthanide). The intensity of the mitochondrial matrix staining with DAB was comparable to that of the Ce2-DAB sample, but containing only ruthenium and no cerium. If an intermediate-loss map is acquired on the control sample with the same experimental settings as that of the mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 labeled with Ce2-DAB (figure 3f), and if the map shows positive contrast for the matrix region of the mitochondria, then it can be concluded that contrast seen in figure 3f is not a true Ce elemental contrast. Figure 4a – d, shows a high-loss and intermediate-loss map acquired using the 3-window method on the control sample, with the same spectrometer settings as in figure 3 (see the supplementary section for details). The mitochondrial matrix in the high-loss map (figure 4c) shows a faint positive contrast indicating an under subtraction of the background, and in the intermediate-loss map (figure 4d), it shows a negative contrast due to over subtraction of the background. Also, in figure 4d, although the mitochondrial matrix shows negative contrast, the spherical stained structures show positive contrast (see where the arrows point). Therefore, it can be concluded that in this case, mitochondrial matrix showing a negative contrast and not a positive contrast (i.e., density contrast), would have led to a partial suppression of the Ce elemental signal, if the sample did contain Ce (control sample does not contain Ce). Figures 4e – h, illustrates another example of high-loss and intermediate-loss elemental maps acquired on the control sample by the 3-window method, in this case the intermediate-loss map was acquired at a slightly different spectrometer settings than the previous example in figure 4d. The intermediate-loss map was acquired for slit width of 15 eV instead of 20 eV, and the pre-edge 1, pre-edge 2 and post-edge were acquired at 84 eV, 102 eV and 135 eV, respectively. In the previous example (figure 4d), the pre-edge 1, pre-edge 2 and post-edge were acquired at 75 eV, 98 eV and 138 eV, respectively. The high-loss map (figure 4g) shows a faint positive contrast as in the previous example (figure 4c), however, the intermediate-loss map (figure 4h) now shows a positive contrast instead of a negative contrast for the mitochondria. It can be deduced from figures 4d and 4h, that the intermediate-loss elemental maps are more susceptible to inconsistencies in background subtraction even for small changes in the slit width or position. The lower SBR of the intermediate-loss N4,5 edge, is the primary reason for this contrast inversion.

Figure 4.

a) Conventional TEM image of the control sample of mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 labeled with plain DAB (no Ce or any other lanthanides). b and b’) The background subtracted high-loss and intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the mitochondrial matrix region of (a), confirming the absence of Ce in the sample. c) The high-loss elemental map computed by the 3-window method, for pre edge 1, pre edge 2 and post-edge obtained for a slit width of 30 eV at 815 eV, 855 eV and 899 eV respectively. The image shows a positive contrast for the matrix region, implying an under subtraction of the background. d) The intermediate-loss elemental map computed by the 3-window method, for pre edge 1, pre edge 2 and post-edge obtained for a slit width of 20 eV at 75 eV, 98 eV and 138 eV respectively. The image shows a negative contrast for the matrix region, implying an over subtraction of the background. However the spherical stained structures show a positive contrast (see the arrows), implying inconsistencies in background subtraction. e) Conventional TEM image of a different region of the same control sample. f and f’) The background subtracted high-loss and intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the mitochondrial matrix region of (d), confirming the absence of Ce in the sample. g) The high-loss elemental map computed by the 3-window method, for pre edge 1, pre edge 2 and post-edge obtained for a slit width of 30 eV at 815 eV, 855 eV and 899 eV respectively. The image shows a positive contrast for the matrix region, implying an under subtraction of the background. h) The intermediate-loss elemental map computed by the 3-window method, for pre edge 1, pre edge 2 and post-edge obtained for a slit width of 15 eV at 84 eV, 102 eV and 135 eV respectively. The image shows a positive contrast for the matrix region, implying an under subtraction of the background.

i) Conventional TEM image of a different region of the same control sample. j and j’) The background subtracted high-loss and intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the mitochondrial matrix region of (g), confirming the absence of Ce in the sample. k) The virtual intermediate-loss spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI image-series, corroborating the results in (h’). l) The intermediate-loss elemental map computed by the EFTEM SI method, for an acquisition acquired from 90 eV to 150 eV, for a slit width of 8 eV and an energy step of 3 eV. The signal was integrated from the region represented by the red box in k. The image shows a no contrast and only noise for the matrix region, implying a correct subtraction of the background. To enhance image display, a Gaussian blur of radius 1 was applied to the conventional images and Gaussian blur of radius 2 was applied to the EFTEM maps.

From the discussion presented above, it is evident that the best technique to acquire an elemental map at the intermediate-loss region is the EFTEM Spectrum Imaging (EFTEM SI)32,50,51,60. This technique involves acquiring a series of EFTEM images with a narrow slit, and with the spectrometer continuously stepping through energies (or energy-loss), from a region representing the edge to the background region prior to the edge onset. The spectrometer is stepped in such a way, that there is a slight energy overlap between successive acquisitions. From the thus acquired EFTEM SI image series, a spectrum can be virtually extracted using the SI picker tool in Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc). Since this extracted spectrum directly correlates to the image series, the user has complete flexibility to choose which region (i.e., which subset of images) contributes to the background and which region contributes to the elemental signal. Additionally, the user can compensate for any chemical shifts or spectrum energy shifts post acquisition.

Figure 4i – l, shows the EFTEM SI intermediate-loss acquisition on the same control sample shown in the previous two examples (figures 4a – h). Figures 4j and 4j’, is the high-loss and intermediate-loss background subtracted spectra, that confirm that there is no Ce in the sample. Figure 4k, is the background subtracted virtual spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI image series, also confirming absence of Ce. Figure 4l, displays the Ce intermediate-loss elemental map that was computed from the energy-loss region indicated by the red box in Figure 4k, i.e., the region that would have contained the N4,5 edge of Ce (the control does not contain Ce). This map shows neither a positive or a negative contrast at the mitochondrial matrix region and is only noise, clearly authenticating the accuracy of background extrapolation of the EFTEM SI technique over the 3-window method.

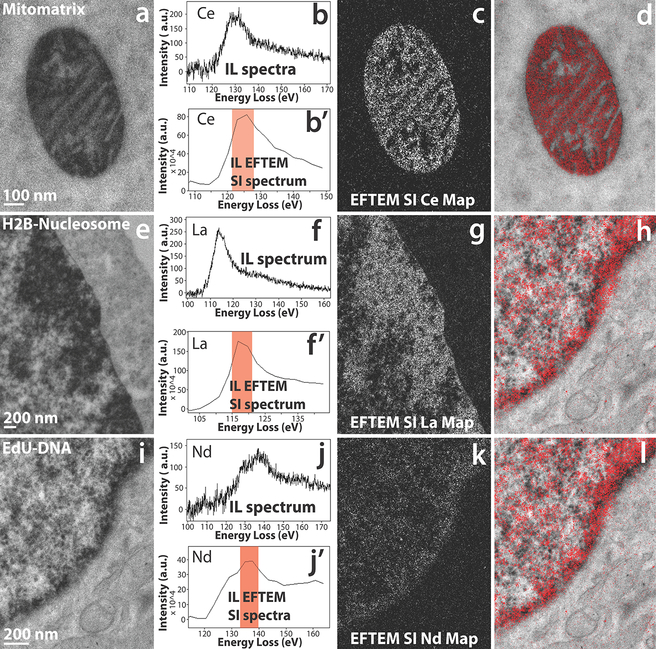

Figure 5, illustrates some examples of EFTEM SI intermediate-loss elemental maps of three different cellular targets, namely using mitochondrial matrix-directed APEX2, histone H2B-Nucleosome and EdU-DNA labeled with three different lanthanides: cerium, lanthanum, and neodymium respectively. This demonstrates the important capability advanced by this method to provide chemical identity of a specific genetically introduced probe providing a base for lanthanide-based identification by analytical EM in a background of context-highlighting electron density free of the chemical label.

Figure 5.

a) Conventional TEM image of mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 labeled with Ce2-DAB (second generation). b) The background subtracted intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the mitochondrial matrix region of (a), confirming the presence of Ce in the sample. b’) The virtual intermediate-loss spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI image-series, corroborating the results in (b). c) The intermediate-loss Ce elemental map computed by the EFTEM SI, the region (or images) contributing to the signal is enclosed in the red box in (b’). d) Single Color EM. e) Conventional TEM image of MiniSOG-H2B labeled with La2-DAB (second generation). f) The background subtracted intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the nucleus of (d), confirming the presence of La in the sample. f’) The virtual intermediate-loss spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI image-series, corroborating the results in (e). g) The intermediate-loss La elemental map computed by the EFTEM SI, the region (or images) contributing to the signal is enclosed in the red box in (f’). h) Single Color EM. i) Conventional TEM image of DNA incubated with EdU and clicked with Fe-TAML-azide for oxidation of Nd-DAB2 (first generation lanthanide DAB). j) The background subtracted intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the nucleus of (g), confirming the presence of Nd in the sample. j’) The virtual intermediate-loss spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI image-series, corroborating the results in (h). k) The intermediate-loss Nd elemental map computed by the EFTEM SI, the region (or images) contributing to the signal is enclosed in the red box in (j’). l) Single Color EM. To enhance image display, a Gaussian blur of radius 1 was applied to the conventional image and Gaussian blur of radius 2 was applied to the EFTEM images and maps.

Figure 5 a – d, demonstrates the acquisition of EFTEM SI intermediate-loss cerium elemental map on the mitochondrial matrix-APEX2 labeled with Ce2-DAB. Figure 5b shows the real background subtracted intermediate-loss spectrum acquired on the mitochondrial region of (a), showing presence of Ce. In Figure 5b’, the virtual spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI image-series, and subsequently background subtracted can be seen. Though the extracted spectrum of 5b’ is of a lower energy resolution than the actual spectra of 5b, the two closely match on the general shape and profile of the N4,5 edge. Computing the elemental map with the aid of the spectrum in b’, with the flexibility to choose parameters post-acquisition, gives undisputable confidence in the correctness of the final result. Figure 5c shows the Ce elemental map, computed from the energy-loss region indicated by the red box and figure 5d displays the color EM image of the pseudo-colored elemental map overlaid over the conventional TEM image. The color EM image was generated by an ImageJ plugin that we developed, and this algorithm has been described elsewhere23.

The main drawback of acquiring elemental maps by the EFTEM SI method over the 3-window method, is that it necessitates the use of a narrow slit width and with an energy overlap between successive images, thereby requiring a far higher electron dose. For example, the EFTEM SI intermediate-loss elemental map acquisition in figure 5c, required 2.6 times the dose of the 3-window acquisition in figure 3f, for an elemental map with substantially lower SNR. The SNR of the EFTEM SI elemental map in figure 5c is 1.6 in comparison to the SNR of 7.4 for the 3-window method in figure 3f. However, the EFTEM SI acquisition in this case was oversampled, and considerable reduction in dose can be achieved by making subtle changes in the acquisition parameters. To illustrate, the EFTEM SI intermediate-loss elemental map in figure 5c, was acquired between an energy-loss of 90 eV to 150 eV, with a slit width of 8 eV and an energy step of 3 eV, resulting in a total of 21 images. The region that used for background subtraction was 98.6 eV to 107.1 eV and that for the Ce signal was 121.4 eV to 127.1 eV. The regions from 90 to 98.5 eV and 121.2 to 150 eV did not contribute in any way for the computation of the elemental map. Therefore, an acquisition from ~ 94 eV to 134 eV, should be sufficient and is wide enough to compensate for any chemical shifts (−2 eV, +7 eV). An EFTEM SI acquisition with a 5 eV energy step instead of 3 eV, would reduce the total number of images in the EFTEM SI stack from 21 to 9, reducing the total dose by ~ 60%. This would then make the dose required for the EFTEM SI acquisition comparable to the dose required for the 3-window method.

Figures 5e – 5f, illustrates the EFTEM SI intermediate-loss lanthanum elemental map acquisition on the MiniSOG-H2B labeled with La2-DAB. The actual spectrum (figure 5f) and the spectrum extracted from the EFTEM SI stack (figure 5f’) show excellent correlation in shape and profile. The lanthanum elemental map shows good signal with a clean background in figure 5g, and figure 5h shows the corresponding color overlay. Figures 5i – 5l, shows the EFTEM SI intermediate-loss neodymium elemental map acquired on the EdU-DNA labeled with Nd-DAB2. The actual spectrum and the extracted EFTEM SI spectrum show good correlation similar to the previous two examples, but the signal in the neodymium elemental map (figure 5k) is faint. The reason for the poor neodymium signal is that, unlike the previous two examples, this sample was labeled with first generation lanthanide DAB rather than the second generation. Therefore, in this case there is 4 times less metal (i.e., Nd) per DAB, with corresponding lower signal amplification, and therefore the signal-above-background (SBR) is low. To accommodate for the low SBR, 3 sets of EFTEM SI stack were acquired on the sample, subsequently aligned and added to create the summed EFTEM SI stack to improve the SNR51. Therefore, even for cases where the concentration of the lanthanide is low, EFTEM SI method of acquiring intermediate-loss elemental maps is still possible.

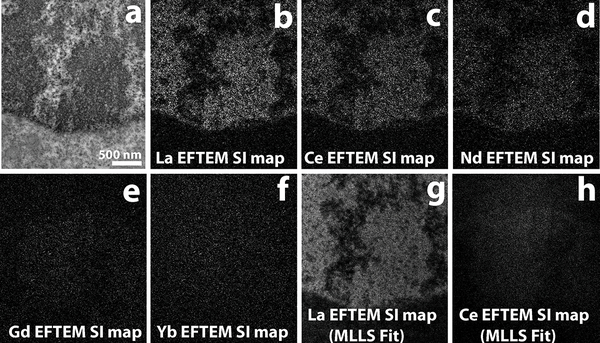

The main limitation of working at the N4,5 edge instead of the M4,5 edge for the lanthanides, is that these have very broad edge profiles, extending well into the edge profiles of many adjacent lanthanides (see figure 2). Therefore, from the perspective of color EM, extending it from single color to multi-color, where the spectral signal from 2 or more lanthanides each labeling a distinct macromolecule/protein can be unambiguously detected and separated23, would be difficult. The immediately ensuing question is what is the degree and scale of the spectral overlap at the N4,5 edge region, if the two (or more) lanthanides are chosen such that they are well separated in atomic number, like La (Z = 57) and Yb (Z = 70). In such a scenario will it be possible to do multi color EM at the intermediate-loss region? This premise can be tested easily, by recording an EFTEM SI acquisition of the H2B-Nucleosome sample labeled with La2-DAB, starting from the La N4,5 edge (onset at 99 eV) and continuing through the Yb N4,5 edge (onset at 185 eV). Subsequent computation of the elemental map at the La N4,5 edge will show the genuine La signal in the sample, while computation of the elemental map at the Yb N4,5 edge will show the bleed-through of the La signal into the Yb N4,5 edge.

Figure 6a shows the conventional TEM image of H2B-Nucleosome sample labeled with La2DAB. An EFTEM SI series was acquired on this region from 77 eV to 212 eV, with an energy slit width of 8 eV and energy step of 3 eV. After the background was fit and extrapolated, the signal was integrated for an energy-width of ~ 6eV, at different energy-loss regions representing the edge of La (115.2 – 121 eV), Ce (121 – 126.9 eV), Nd (132.8 – 138.6 eV), Gd (150.4 – 156.2 eV) and Yb (194.4 – 200.3 eV). The La EFTEM SI map shown in Figure 6b, displays strong La signal at the H2B region of the nucleus as expected. In the Ce EFTEM SI map (Figure 6c) of the same region, indicates that there is significant bleed-through of the La signal into the Ce edge, but it gets fainter at the Nd edge (Figure 6d) and is almost negligible at the Gd edge (Figure 6e) and Yb edge (Figure 6f). The multiple linear least-squares (MLLS) fitting is a powerful technique in EELS/EFTEM to separate overlapping edges by precisely mapping out the spectral shape resulting from fitting the spectra extracted from the EFTEM SI series to a reference spectra61. Figure 6g and 6h, show the MLLS fit algorithm of the EFTEM SI series to a previously acquired spectra of La and Ce, respectively. The bleed-through of the La signal into the Ce intermediate-loss region in Figure 6c, is completely removed by applying the MLLS technique. This clearly shows that with signal from adjacent lanthanides can indeed be effectively separated at the intermediate-loss region by using advanced computational techniques like MLLS. The panels 6g and 6h, were processed after a bin 4 to speed up the computation and the MLLS subroutine of Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc) was used to process the datasets. Although, this paper does not provide any results of multicolor EM, the discussion above gives some confidence that it can be done in the Intermediate loss region. We are currently in the process of chemically synthesizing DAB chelates of lanthanides, other than the 3 listed in this manuscript (La, Ce and Nd) such as Gd and Yb, and will explore multicolor EM at the intermediate-loss region in a future manuscript.

Figure 6.

a) Conventional TEM image of H2B-Nucleosome sample labeled with La2DAB. b) La EFTEM SI map, with strong La signal as expected. c) Ce EFTEM SI map of the same sample indicates that there is significant bleed-through of the La signal into the Ce edge, that gets fainter at the Nd edge (d) and is almost negligible in the Gd edge (e) and Yb edge (f). La (g) and Ce (h) maps computed with the multiple linear least-squares (MLLS) fitting to La and Ce spectra acquired separately. The MLLS sub-routine of Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc), is a linear fitting algorithm that can be applied to discriminate overlapping edges. With MLLS fitting, the bleed-through of the La signal into the Ce edge can be effectively removed (h). The MLLS fit was applied to images after binning by 4 (g and h), all other panels are unbinned images.

CONCLUSION

As an extension of the technique of color EM, we have expanded both the labeling chemistry of the lanthanide-chelated DAB’s and the different strategies of targeting specific subcellular structures/macromolecules. The chemical synthesis of the novel second-generation DAB-lanthanide chelates has been demonstrated. These second- generation DAB-lanthanides bind two chelated lanthanide ions per DAB molecule, instead of two DAB molecules chelated to a single lanthanide ion as in the first- generation lanthanide-DAB’s. Therefore, it provides for a 4x increase in the number of lanthanide atoms for every oxidized DAB molecule, resulting in significant signal amplification in the EELS core-loss signal. Additionally, we introduced the idea of using the N4,5 edge (intermediate-loss) instead of the M4,5 edge (high-loss) for the acquisition and computation of the lanthanide elemental maps. The substantially greater total characteristic signal due to the much higher inelastic scattering cross-sections at the intermediate-loss region provides a compelling reason for this strategy. For the same acquisition parameters, the intermediate-loss map provides ~4x increase in signal-to-noise and ~2x increase in resolution, in comparison to the high-loss map. However, due to the much lower signal-above-background at the intermediate-loss region, the intermediate-loss elemental maps of the lanthanides are more prone to artifacts due to the inconsistencies in the background subtraction. Most of these artifacts and issues in the lanthanide intermediate-loss elemental map can be eliminated, if the maps are acquired using the more sophisticated EFTEM Spectrum Imaging (EFTEM SI) instead of the 3-window method. The intermediate-loss EFTEM SI elemental maps were used to generate color EM images of mitochondrial matrix-directed APEX2 labeled with second generation Ce2-DAB, histone H2B-Nucleosome labeled with second generation La2-DAB and EdU-DNA labeled with first generation Nd-DAB2. All the examples demonstrated in the paper are of single-color EM only. The main limitation of using N4,5 edge or intermediate-loss map for the lanthanides, is the broader edge profile includes large overlapping regions with adjacent lanthanide edge profiles and hinders extension of this technique to enable multicolor EM, where 2 or more lanthanide chelated DAB’s are simultaneously used to label different subcellular targets. However, if there is sufficiently large difference in Z between the lanthanides, e.g., lanthanum and gadolinium, or cerium and ytterbium, then multicolor EM should be potentially possible in the intermediate-loss region and will be explored in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Scheme of the synthesis of Ln2-DAB. Reagents, solvents, conditions, a) Br2, acetic acid, rt; b) ethyl acrylate, Pd(OAc)2, (o-tolyl)3phosphine, NEt3, DMF, 80°C; c) BOC anhydride, DMAP, DMF, 80°C; d) 1 atm H2, Pd-C, EtOAc-EtOH, rt; e) NaOH, dioxane-MeOH, rt; f) HOSu, EDC, DMF, rt; g) eda-EDTA, NEt3, DMSO, rt; h) TFA, rt; i) LnCl3, pH 7 buffer, rt.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Rob Bilhorn and Benjamin Bammes of Direct Electron for help with the DE-12 detector. We would like to thank David Mastronarde of University of Colorado Boulder for help with SerialEM. This work was supported by NIH grants R01GM086197 and R24GM137200.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knoll M & Ruska E (1932). Knoll M, Ruska E. The electron microscope. 1932, vol 78, p 318. Z Phys 79(9–10), 699–699. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter CB & Williams DB (2009). Transmission Electron Microscopy. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egerton RF (1996). Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy. Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein JI, Newbury DE, Echlin P, Joy DC, Lyman CE, Lifshin E, Sawyer L & Michael JR (2003). Scanning Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller DA, Kourkoutis LF, Murfitt M, Song JH, Hwang HY, Silcox J, Dellby N & Krivanek OL (2008). Atomic-scale chemical imaging of composition and bonding by aberration-corrected microscopy. Science 319(5866), 1073–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller DA (2009). Structure and bonding at the atomic scale by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Nat Mater 8(4), 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varela M, Lupini AR, van Benthem K, Borisevich AY, Chisholm MF, Shibata N, Abe E & Pennycook SJ (2005). Materials characterization in the aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope. Annu Rev Mater Res 35, 539–569. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronova MA, Kim YC, Harmon R, Sousa AA, Zhang G & Leapman RD (2008). Three-dimensional elemental mapping of phosphorus by quantitative electron spectroscopic tomography (QuEST) (Reprinted from J. Struct. Biol, vol 160, pg 35–48, 2007). J Struct Biol 161(3), 322–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronova MA, Kim YC, Pivovarova NB, Andrews SB & Leapman RD (2009). Quantitative EFTEM mapping of near physiological calcium concentrations in biological specimens. Ultramicroscopy 109(3), 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aronova MA & Leapman RD (2012). Development of electron energy-loss spectroscopy in the biological sciences. Mrs Bull 37(1), 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somlyo AP & Shuman H (1982). Electron-Probe and Electron-Energy Loss Analysis in Biology. Ultramicroscopy 8(1–2), 219–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egerton RF (2012). Tem-Eels: A Personal Perspective. Ultramicroscopy 119, 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grogger W, Varela M, Ristau R, Schaffer B, Hofer F & Krishnan KM (2005). Energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy on the nanometer length scale. J Electron Spectrosc 143(2–3), 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofer F, Grogger W, Kothleitner G & Warbichler P (1997). Quantitative analysis of EFTEM elemental distribution images. Ultramicroscopy 67(1–4), 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lozano-Perez S, Bernal VD & Nicholls RJ (2009). Achieving sub-nanometre particle mapping with energy-filtered TEM. Ultramicroscopy 109(10), 1217–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verbeeck J, Van Dyck D & Van Tendeloo G (2004). Energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy: an overview. Spectrochim Acta B 59(10–11), 1529–1534. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leapman RD (2017). Application of EELS and EFTEM to the life sciences enabled by the contributions of Ondrej Krivanek. Ultramicroscopy 180, 180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosman M & Keast VJ (2008). Optimizing EELS acquisition. Ultramicroscopy 108(9), 837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goping G, Pollard HB, Srivastava M & Leapman R (2003). Mapping protein expression in mouse pancreatic islets by immunolabeling and electron energy loss spectrum-imaging. Microsc Res Techniq 61(5), 448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt JA & Williams DB (1991). Electron Energy-Loss Spectrum-Imaging. Ultramicroscopy 38(1), 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kothleitner G & Hofer F (2003). Elemental occurrence maps: a starting point for quantitative EELS spectrum image processing. Ultramicroscopy 96(3–4), 491–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leapman RD (2003). Detecting single atoms of calcium and iron in biological structures by electron energy-loss spectrum-imaging. J Microsc-Oxford 210, 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams SR, Mackey MR, Ramachandra R, Palida Lemieux SF, Steinbach P, Bushong EA, Butko MT, Giepmans BN, Ellisman MH & Tsien RY (2016). Multicolor Electron Microscopy for Simultaneous Visualization of Multiple Molecular Species. Cell Chem Biol 23(11), 1417–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirozzi NM, Hoogenboom JP & Giepmans BNG (2018). ColorEM: analytical electron microscopy for element-guided identification and imaging of the building blocks of life. Histochem Cell Biol 150(5), 509–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scotuzzi M, Kuipers J, Wensveen DI, de Boer P, Hagen KW, Hoogenboom JP & Giepmans BNG (2017). Multi-color electron microscopy by element-guided identification of cells, organelles and molecules. Sci Rep-Uk 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boassa D, Lemieux SP, Lev-Ram V, Hu J, Xiong Q, Phan S, Mackey M, Ramachandra R, Peace RE, Adams SR, Ellisman MH & Ngo JT (2019). Split-miniSOG for Spatially Detecting Intracellular Protein-Protein Interactions by Correlated Light and Electron Microscopy. Cell Chem Biol, 26(10), 1407–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sastri M, Darshi M, Mackey M, Ramachandra R, Ju S, Phan S, Adams S, Stein K, Douglas CR, Kim JJ, Ellisman MH, Taylor SS & Perkins GA (2017). Sub-mitochondrial localization of the genetic-tagged mitochondrial intermembrane space-bridging components Mic19, Mic60 and Sam50. J Cell Sci 130(19), 3248–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heil T & Kohl H (2010). Optimization of EFTEM image acquisition by using elastically filtered images for drift correction. Ultramicroscopy 110(7), 745–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aoyama K, Matsumoto R & Komatsu Y (2002). How to make mapping images of biological specimens - data collection and image processing. J Electron Microsc 51(4), 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramachandra R, Bouwer JC, Mackey MR, Bushong E, Peltier ST, Xuong NH & Ellisman MH (2014). Improving signal to noise in labeled biological specimens using energy-filtered TEM of sections with a drift correction strategy and a direct detection device. Microsc Microanal 20(3), 706–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaffer B, Grogger W & Kothleitner G (2004). Automated spatial drift correction for EFTEM image series. Ultramicroscopy 102(1), 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terada S, Aoyama T, Yano F & Mitsui Y (2001). Time-resolved acquisition technique for elemental mapping by energy-filtering TEM. J Electron Microsc 50(2), 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egerton RF (1984). Parallel-Recording Systems for Electron-Energy Loss Spectroscopy (Eels). J Electron Micr Tech 1(1), 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faruqi AR, Cattermole DM & Raeburn C (2003). Direct electron detection methods in electron microscopy. Nucl Instrum Meth A 513(1–2), 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xuong NH, Milazzo AC, Leblanc P, Duttweiler F, Bouwer JC, Peltier ST, Ellisman M, Denes P, Bieser F & Matis HS (2004). First use of a high- sensitivity active pixel sensor array as a detector for electron microscopy. Proc. SPIE 5301, 242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milazzo AC, Leblanc P, Duttweiler F, Jin L, Bouwer JC, Peltier S, Ellisman M, Bieser F, Matis HS, Wieman H, Denes P, Kleinfelder S & Xuong NH (2005). Active pixel sensor array as a detector for electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 104(2), 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faruqi AR, Henderson R, Pryddetch M, Allport P & Evans A (2005). Direct single electron detection with a CMOS detector for electron microscopy. Nucl Instrum Meth A 546(1–2), 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xuong NH, Jin L, Kleinfelder S, Li SD, Leblanc P, Duttweiler F, Bouwer JC, Peltier ST, Milazzo AC & Ellisman M (2007). Future directions for camera systems in electron microscopy. Method Cell Biol 79, 721–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin L, Milazzo AC, Kleinfelder S, Li SD, Leblanc P, Duttweiler F, Bouwer JC, Peltier ST, Ellisman MH & Xuong NH (2008). Applications of direct detection device in transmission electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 161(3), 352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milazzo AC, Lanman J, Bouwer JC, Jin L, Peltier ST, Johnson JE, Kleinfelder S, Xuong NH & Ellisman MH (2009). Advanced Detector Development for Electron Microscopy Enables New Insight into the Study of the Virus Life Cycle in Cells and Alzheimer’s Disease. Microsc Microanal 15, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milazzo AC, Moldovan G, Lanman J, Jin LA, Bouwer JC, Klienfelder S, Peltier ST, Ellisman MH, Kirkland AI & Xuong NH (2010). Characterization of a direct detection device imaging camera for transmission electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 110(7), 741–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baek D, Zachman M, Goodge B, Lu D, Hikita Y, Hwang HY & Kourkoutis LF Direct Electron Detection for Atomic-Resolution EELS Mapping at Cryogenic Temperature. In Microsc Microanal, pp. Microsc.Microanal. 24 (Suppl 21). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hart JL, Lang AC, Leff AC, Longo P, Trevor C, Twesten RD & Taheri ML (2017). Direct Detection Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy: A Method to Push the Limits of Resolution and Sensitivity. Sci Rep-Uk 73 Egerton, R.F. (1996). Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy. Plenum Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maigne A & Wolf M (2018). Low-dose electron energy-loss spectroscopy using electron counting direct detectors. Microscopy-Jpn 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahn CC & Krivanek OL (1983). EELS Atlas. Gatan. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Egerton RF, Li P & Malac M (2004). Radiation damage in the TEM and SEM. Micron 35(6), 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berger A & Kohl H (1993). Optimum Imaging Parameters for Elemental Mapping in an Energy Filtering Transmission Electron-Microscope. Optik 92(4), 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kortje KH (1994). Image-Eels - Simultaneous Recording of Multiple Electron- Energy-Loss Spectra from Series of Electron Spectroscopic Images. Journal of Microscopy 174, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lavergne JL, Martin JM & Belin M (1992). Interactive Electron-Energy-Loss Elemental Mapping by the Imaging-Spectrum Method. Microsc Microanal M 3(6), 517–528. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaffer B, Kothleitner G & Grogger W (2006). EFTEM spectrum imaging at high-energy resolution. Ultramicroscopy 106(11–12), 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe M & Allen FI (2012). The SmartEFTEM-SI method: Development of a new spectrum-imaging acquisition scheme for quantitative mapping by energy-filtering transmission electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 113, 106–119. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mastronarde DN (2005). Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol 152(1), 36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tseng QZ, Wang I, Duchemin-Pelletier E, Azioune A, Carpi N, Gao J, Filhol O, Piel M, Thery M & Balland M (2011). A new micropatterning method of soft substrates reveals that different tumorigenic signals can promote or reduce cell contraction levels. Lab Chip 11(13), 2231–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Messaoudi C, Aschman N, Cunha M, Oikawa T, Sorzano COS & Marco S (2013). Three-Dimensional Chemical Mapping by EFTEM-TomoJ Including Improvement of SNR by PCA and ART Reconstruction of Volume by Noise Suppression. Microsc Microanal 19(6), 1669–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He ZL & Zhou JZ (2008). Empirical evaluation of a new method for calculating signal-to-noise ratio for microarray data analysis. Appl Environ Microb 74(10), 2957–2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waters JC (2009). Accuracy and precision in quantitative fluorescence microscopy. J Cell Biol 185(7), 1135–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayat MA (1981). Fixation for Electron Microscopy. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maigne A & Wolf M (2018). Low-dose electron energy-loss spectroscopy using electron counting direct detectors. Microscopy-Jpn 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reimer DL & Kohl H (2008). Transmission Electron Microscopy. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schaffer B, Grogger W, Kothleitner G & Hofer F (2008). Application of high-resolution EFTEM SI in an AEM. Anal Bioanal Chem 390(6), 1439–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.LEAPMAN RD & SWYT CR (1988) Separation of overlapping core edges in electron energy loss spectra by multiple-least-squares fitting. Ultramicroscopy, 26, 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfannmoller M, Flugge H, Benner G, Wacker I, Sommer C, Hanselmann M, Schmale S, Schmidt H, Hamprecht FA, Rabe T, Kowalsky W & Schroder RR (2011). Visualizing a Homogeneous Blend in Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells by Analytical Electron Microscopy. Nano Lett 11(8), 3099–3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pfannmoller M, Flugge H, Benner G, Wacker I, Kowalsky W & Schroder RR (2012). Visualizing photovoltaic nanostructures with high-resolution analytical electron microscopy reveals material phases in bulk heterojunctions. Synthetic Met 161(23–24), 2526–2533. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Scheme of the synthesis of Ln2-DAB. Reagents, solvents, conditions, a) Br2, acetic acid, rt; b) ethyl acrylate, Pd(OAc)2, (o-tolyl)3phosphine, NEt3, DMF, 80°C; c) BOC anhydride, DMAP, DMF, 80°C; d) 1 atm H2, Pd-C, EtOAc-EtOH, rt; e) NaOH, dioxane-MeOH, rt; f) HOSu, EDC, DMF, rt; g) eda-EDTA, NEt3, DMSO, rt; h) TFA, rt; i) LnCl3, pH 7 buffer, rt.