Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular deaths increased during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. However, it is unclear whether racial/ethnic minorities have experienced a disproportionate rise in heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths.

Methods:

We used the National Center for Health Statistics to identify heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic individuals from March-August 2020 (pandemic period), as well as for the corresponding months in 2019 (historical control). We determined the age- and sex-standardized deaths per million by race/ethnicity for each year. We then fit a modified Poisson model with robust standard errors to compare change in deaths by race/ethnicity for each condition in 2020 vs. 2019.

Results:

There were a total of 339,076 heart disease and 76,767 cerebrovascular disease deaths from March through August 2020, compared to 321,218 and 72,190 deaths during the same months in 2019. Heart disease deaths increased during the pandemic in 2020, compared with the corresponding period in 2019, for non-Hispanic White (age-sex standardized deaths per million, 1234.2 vs. 1208.7; risk ratio for death [RR] 1.02, 95% CI 1.02–1.03), non-Hispanic Black (1783.7 vs. 1503.8; RR 1.19, 1.17–1.20), non-Hispanic Asian (685.7 vs. 577.4; RR 1.19, 1.15–1.22), and Hispanic (968.5 vs. 820.4, RR 1.18, 1.16–1.20) populations. Cerebrovascular disease deaths also increased for non-Hispanic White (268.7 vs. 258.2; RR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03–1.05), non-Hispanic Black (430.7 vs. 379.7; RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.10–1.17), non-Hispanic Asian (236.5 vs. 207.4; RR 1.15, 1.09–1.21), and Hispanic (264.4 vs. 235.9; RR 1.12, 1.08–1.16) populations. For both heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths, each racial and ethnic minority group experienced a larger relative increase in deaths than the non-Hispanic White population (interaction term, p<0.001).

Conclusions:

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations experienced a disproportionate rise in deaths due to heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, suggesting that racial/ethnic minorities have been most impacted by the indirect effects of the pandemic. Public health and policy strategies are needed to mitigate the short- and long-term adverse effects of the pandemic on the cardiovascular health of minority populations.

Keywords: Race/Ethnicity, Health disparities, Cardiovascular disease, Cerebrovascular disease, COVID-19, Pandemic, Mortality

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted the delivery of health care services to patients with cardiovascular disease in the United States. During the early phase of the pandemic, hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions such as myocardial infarction and stroke declined by 40–50% across the country.1–4 At the same time, population-level deaths due to cardiac and cerebrovascular causes increased in some geographic regions,5 raising concern that the pandemic has had a substantial, indirect toll on patients with non-COVID-19-related medical conditions.

Despite the concerning national rise in cardiovascular deaths during the pandemic, little is known about whether these increases have been disproportionately concentrated among racial and ethnic minority populations. A large body of evidence has shown that Black and Hispanic communities have borne a high burden of COVID-19.6–10 It is possible that these communities have also been disproportionately affected by factors that have contributed to an increase in heart and cerebrovascular disease deaths, including reduced access to healthcare services, increased health system strain, and hospital avoidance due to fear of contracting the virus in high-burden areas.11–14 In addition, inequities in the social determinants of health that are associated with cardiovascular risk, such as poverty and stress, have likely worsened for these groups.15–17 Understanding how deaths have changed across different racial and ethnic populations is critically important, and could inform public health strategies to mitigate the short- and long-term adverse effects of the pandemic on cardiovascular health.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to characterize heart disease and cerebrovascular deaths by race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Asian, and Hispanic populations) during the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 compared with a historical control (2019). In addition, we evaluated whether relative increases in deaths were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minority groups, compared with non-Hispanic White persons, after the onset of the pandemic in 2020 relative to corresponding months in 2019.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Data

We obtained monthly cause of death data from the NCHS from March through August 2020, as well as for the corresponding months in 2019.18,19 We focused on deaths beginning in March because this is when many states began to experience a rapid rise in COVID-19 cases and issued stay-at-home orders. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes were used to identify underlying causes of death caused by heart diseases (I00–I09, I11, I13, I20–I51) and cerebrovascular diseases (I60–I69). Deaths with an underlying cause of COVID-19 were excluded.

Race and Ethnicity

Information about the race/ethnicity for deaths are obtained from death certificates by the NCHS. We included the following racial/ethnic groups in the analysis: non-Hispanic (non-Hispanic) White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic. We excluded American Indian/Alaska Natives and racial/ethnic groups designated as ‘other’, because data for these groups were often suppressed due to low counts in accordance with NCHS confidentiality standards. Population data for each race/ethnicity were obtained from the American Community Survey files.

Statistical Analysis

To determine heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths by race and ethnicity, we divided the total number of deaths (March through August of each respective year) for each condition by the total population (per million) of each group. We then calculated age- and sex-standardized deaths per million for each racial and ethnic group (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic) by applying direct standardization using census counts of the White population (in 2019) as the reference. Using the same reference population, the direct standardization approach was also applied to determine monthly age and sex-standardized deaths per million for each racial and ethnic group. The relative and absolute monthly difference in deaths per million in 2020 vs. 2019 was calculated for each racial and ethnic group.

Next, we fit a modified Poisson regression model with robust standard errors to calculate the risk ratio for death in 2020 vs. 2019 for each racial/ethnic group after adjustment for age and sex.20 We used this approach because information on deaths for each condition was available as summarized (grouped tabular) binomial data (e.g. the number of deaths for each unique combination of age strata in 5-year intervals, sex, and racial/ethnic group). The modified Poisson model is a numerically stable procedure and use of the robust variance allows for valid inference (e.g. accounting for heteroscedasticity).20,21 Our model included an interaction term for race/ethnicity and year, which allowed us to compare the relative risk of death for each racial/ethnic minority group (vs. non-Hispanic White) in 2020 vs. 2019.

Two-sided p<0.05 defined statistical significance. Analyses were performed using R 3.5.2. Institutional Board Review approval from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center was not required due to the use of publicly-available, deidentified datasets.

Results

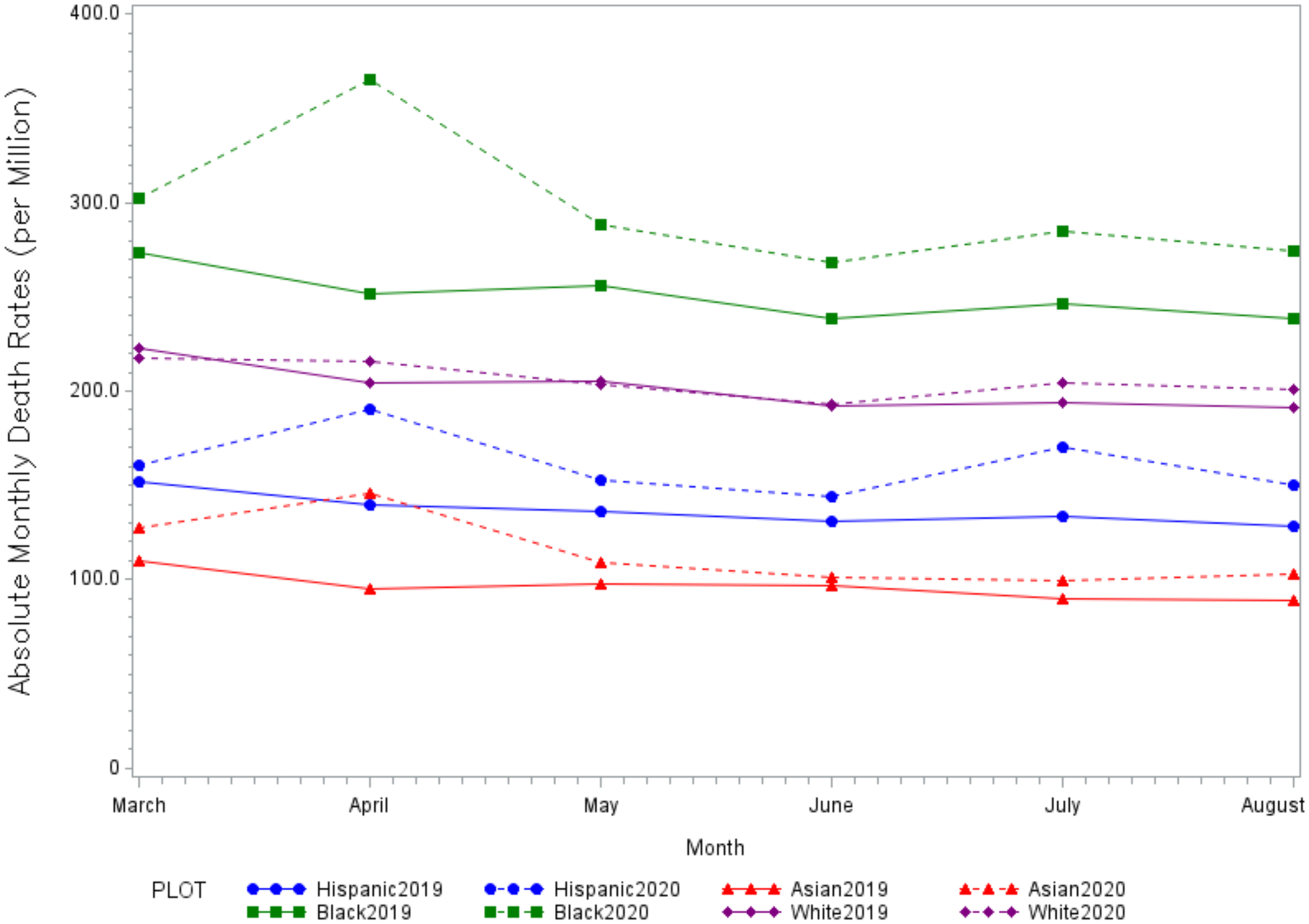

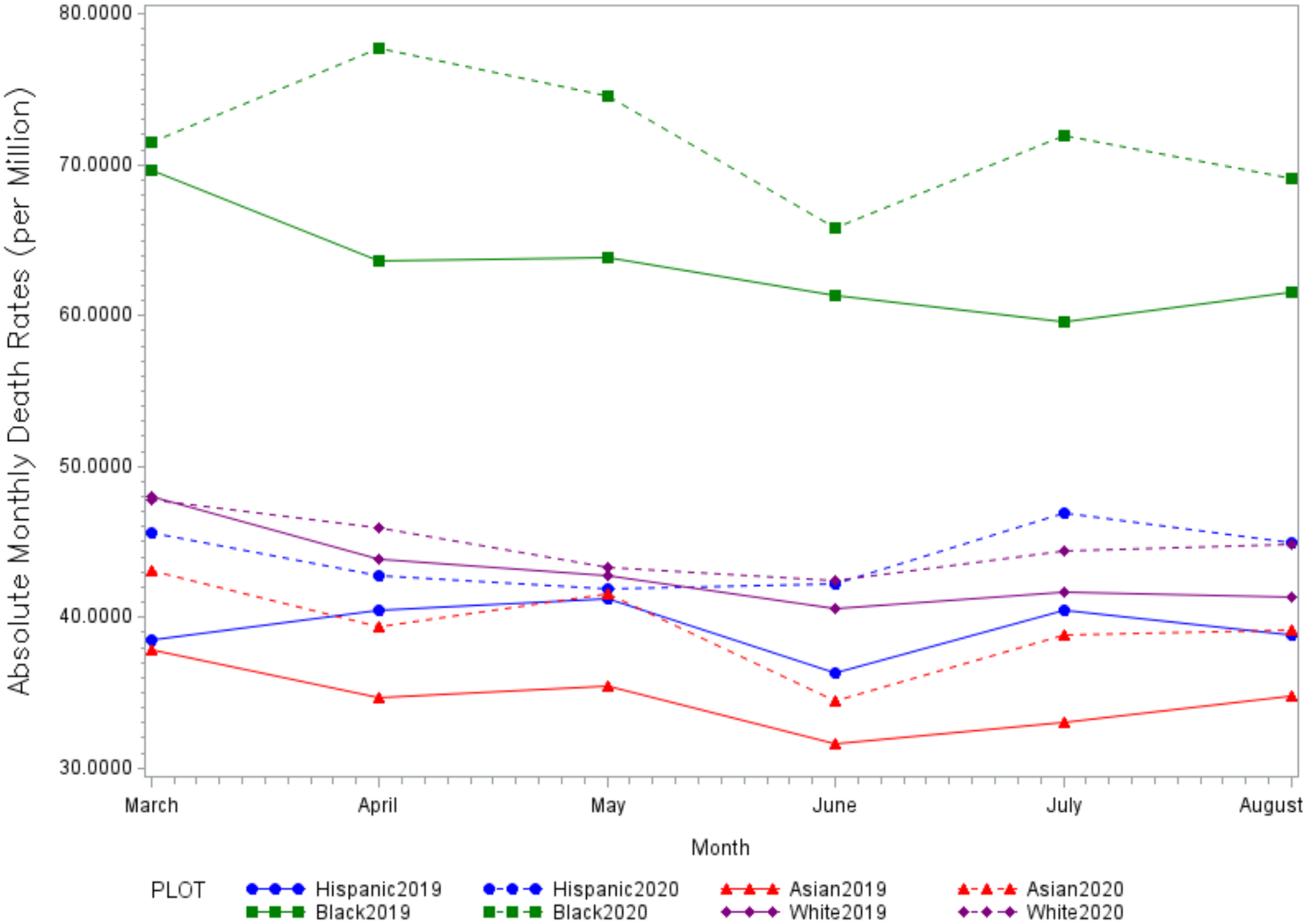

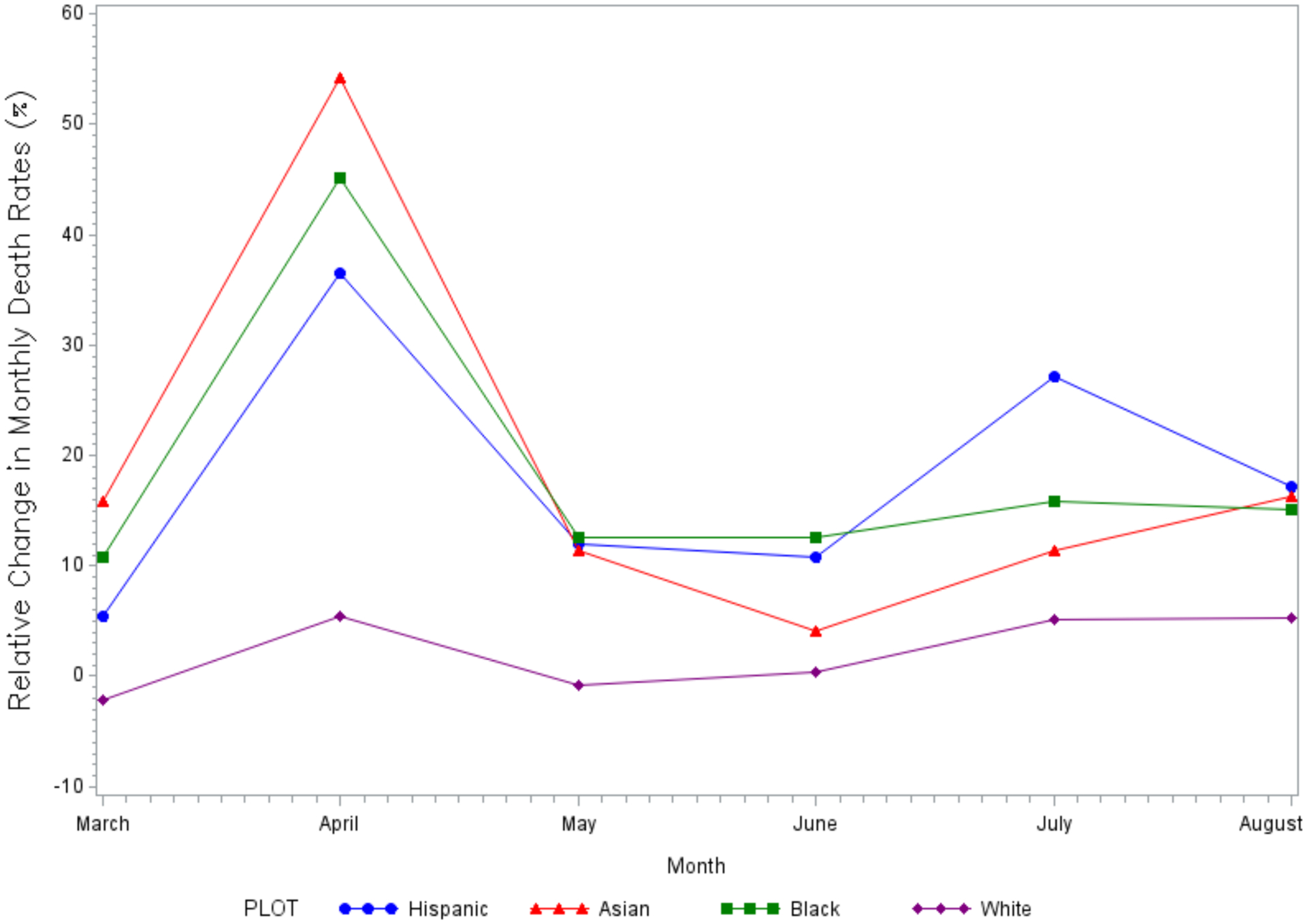

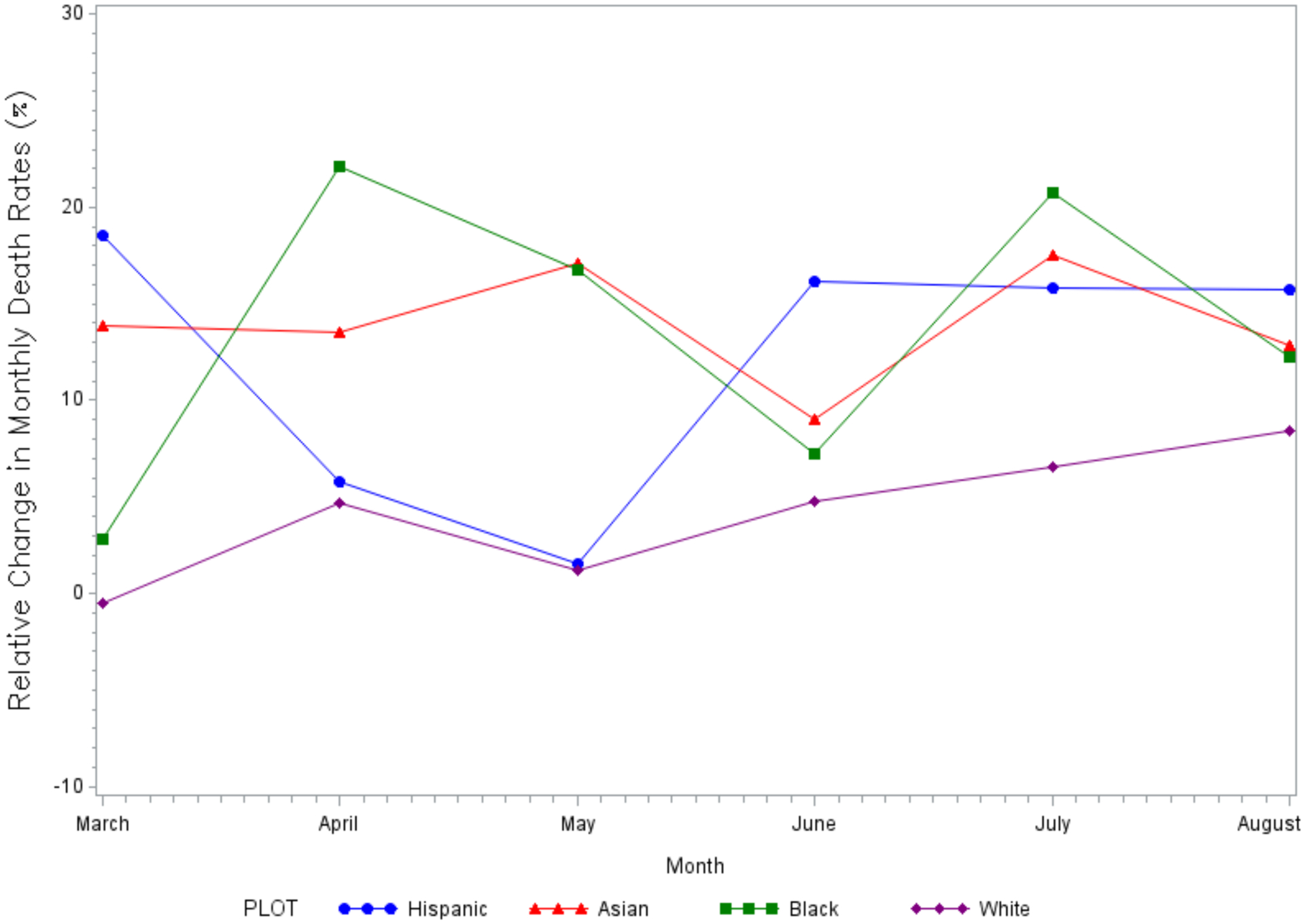

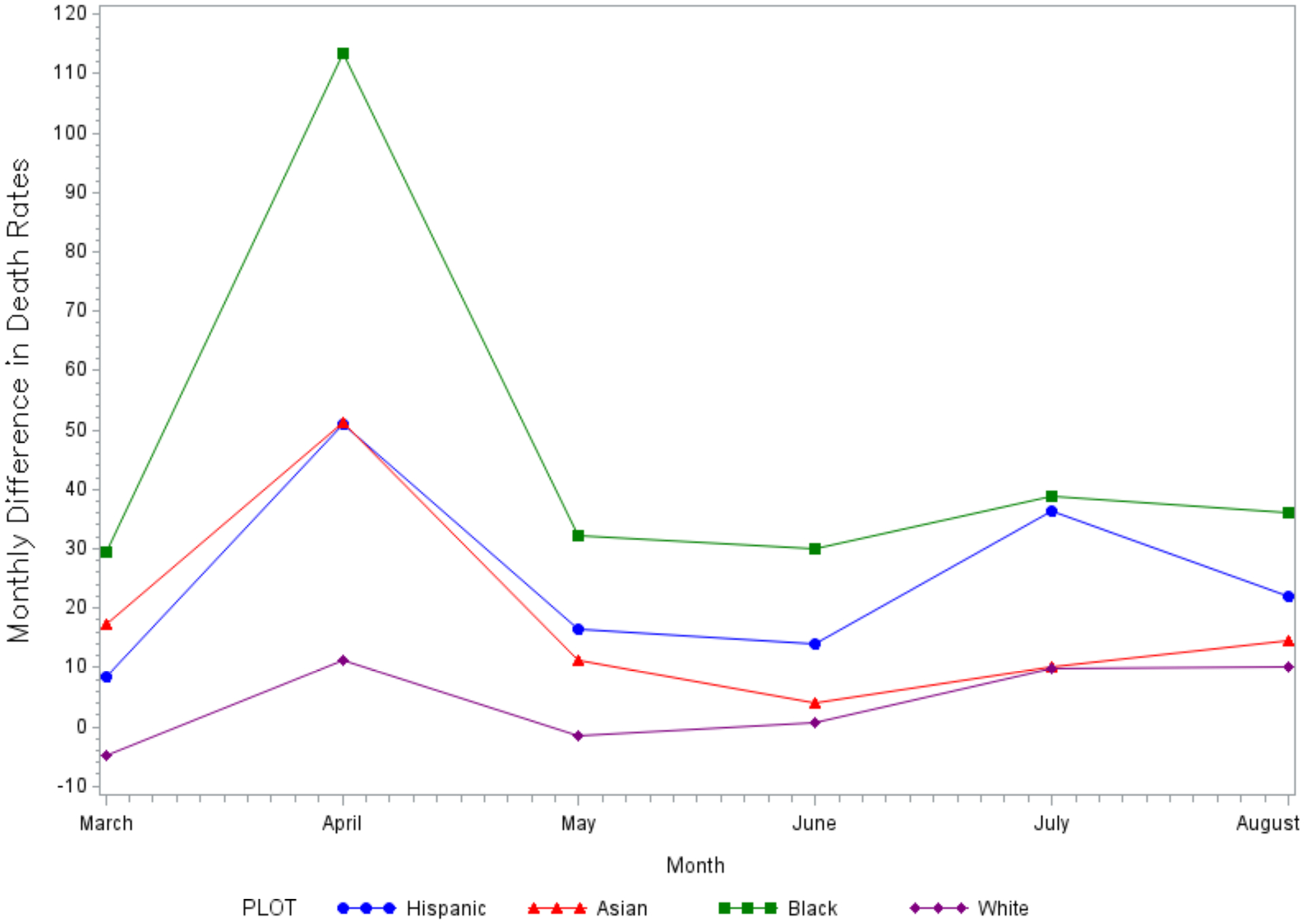

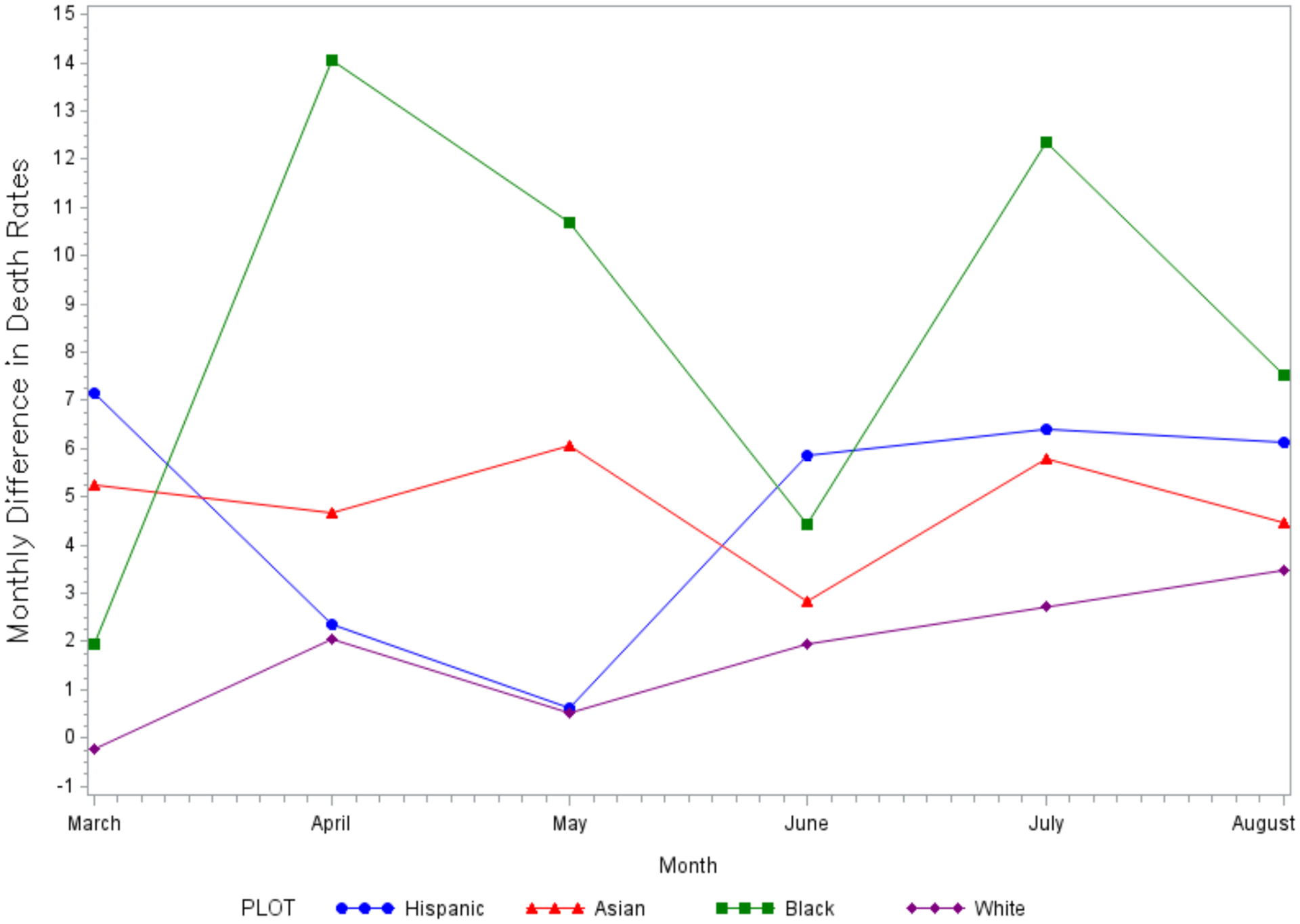

In the United States, there were a total of 339,076 heart disease and 76,767 cerebrovascular disease deaths during the pandemic from March through August 2020, compared to 321,218 and 72,190 deaths during the corresponding months in 2019. Observed heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths per million for each year are shown by race and ethnicity in Supplemental Table I and age-sex standardized deaths per million are shown in Table 1. In addition, monthly age-sex standardized deaths per million are shown in Figure 1. The relative and absolute monthly differences are shown by race/ethnicity (2020 vs. 2019) in Figures 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Age-Sex Standardized Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease Deaths per Million by Race and Ethnicity

| Heart disease deaths per million, 2019 | Heart disease deaths per million, 2020 | Cerebrovascular disease deaths per million, 2019 | Cerebrovascular disease deaths per million, 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH White | 1208.7 | 1234.2 | 258.2 | 268.7 |

| NH Black | 1503.8 | 1783.7 | 379.7 | 430.7 |

| NH Asian | 577.4 | 685.7 | 207.4 | 236.5 |

| Hispanic | 820.4 | 968.5 | 235.9 | 264.4 |

NH, non-Hispanic

The White population (in 2019) was used as the reference for age-sex standardization.

Figure 1. Monthly Age-Sex Standardized Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease Deaths per Million by Race and Ethnicity, 2020 vs. 2019.

Age-sex standardized heart disease (Panel A) and cerebrovascular disease (Panel B) deaths per million from March through August 2020 (dashed lines) compared with corresponding months in 2019 (solid lines) for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Panel A. Heart Disease

Panel B. Cerebrovascular Disease

Figure 2. Relative Monthly Differences Age-Sex Standardized Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease Deaths per Million by Race and Ethnicity, 2020 vs. 2019.

Relative (%) change in age-sex standardized heart disease (Panel A) and cerebrovascular disease (Panel B) deaths per million from March through August (2020 vs. 2019) for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Panel A. Heart Disease

Panel B. Cerebrovascular Disease

Figure 3. Absolute Monthly Differences in Age-Sex Standardized Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease Deaths per Million by Race and Ethnicity, 2020 vs. 2019.

Absolute differences in age-sex standardized heart disease (Panel A) and cerebrovascular disease (Panel B) deaths per million from March through August (2020 vs. 2019) for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Panel A. Heart Disease

Panel B. Cerebrovascular Disease

Overall, heart disease deaths increased during the pandemic in 2020 compared with the corresponding period in 2019 for non-Hispanic White (age-sex standardized deaths per million, 1234.2 vs. 1208.7; risk ratio [RR] 1.02, 95% CI 1.02–1.03), non-Hispanic Black (1783.7 vs. 1503.8; RR 1.19, 1.17–1.20), non-Hispanic Asian (685.7 vs. 577.4; RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.15–1.22), and Hispanic (968.5 vs. 820.4, RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.16–1.20) populations (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure I). Cerebrovascular disease deaths also increased for non-Hispanic White (age-sex standardized deaths per million, 268.7 vs. 258.2; RR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03–1.05), non-Hispanic Black (430.7 vs. 379.7; RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.10–1.17), non-Hispanic Asian (236.5 vs. 207.4; IRR 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.21), and Hispanic (264.4 vs. 235.9; RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.08–1.16) populations (Table 2). For both heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths, the interaction term for each racial/ethnic minority group (vs. non-Hispanic Whites) and year was statistically significant (p<0.001), indicating that the non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic populations each experienced a larger relative increase in deaths compared with non-Hispanic Whites during the pandemic (2020 vs. 2019).

Table 2.

Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease Deaths by Race/Ethnicity (2020 vs. 2019)

| Risk Ratio (2020 vs. 2019)* |

95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart Disease | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.19 | 1.17–1.20 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.19 | 1.15–1.22 |

| Hispanic | 1.18 | 1.16–1.20 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.04 | 1.03–1.05 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.13 | 1.10–1.17 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.15 | 1.09–1.21 |

| Hispanic | 1.12 | 1.08–1.16 |

Data represent deaths that occurred from March through August in each year. The interaction term for race/ethnicity and year (2020 vs. 2019) was statistically significant (p<0.001), indicating that each racial and ethnic group experienced a more pronounced increase in deaths relative to the non-Hispanic White population.

Discussion

In the United States, across all racial and ethnic groups, heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths were higher after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic between the months of March and August in 2020 relative to corresponding months in 2019. Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations each experienced a ≈20% relative increase in heart disease deaths, and a ≈13% relative increase in cerebrovascular disease deaths, during the pandemic. The increase in deaths due to heart disease and cerebrovascular disease was significantly more pronounced among these racial and ethnic minority populations compared with the non-Hispanic White population.

The racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular deaths that have emerged amid the COVID-19 pandemic are concerning. Although the direct toll of COVID-19 on Black and Hispanic adults as well as subgroups of the Asian population has been substantial,6–10,22,23 the marked rise in heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths suggest that these groups have also disproportionately been impacted by the indirect effects of the pandemic. Disruptions in access to health care services during the pandemic may have had a larger impact on the health outcomes of Black and Hispanic individuals, as these populations have a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension,24 obesity,25 and diabetes,26 as well as cardiovascular disease. At the same time, the strain imposed on already resource-constrained healthcare systems in these communities may have led to issues in care delivery, such as delays in access to hospital services, the deferral of cardiovascular procedures, and the delivery of suboptimal inpatient care for non-COVID-19 conditions.27–29

The avoidance of health care systems has likely also played a role in the disproportionate rise in cardiac and cerebrovascular deaths among racial and ethnic minorities, particularly during the early phase of the pandemic when less was known about SARS-CoV2.14 Because COVID-19 case rates have been highest in minority communities,6–9 individuals residing in these areas may have been more reluctant to seek hospital care for acute conditions. For example, a recent survey by the American Heart Association found that 41% of Hispanic Americans and 33% of Black Americans would stay at home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke due to fear of exposure to COVID-19 at the hospital.30 Although the use of telemedicine increased during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic to bridge gaps in care, Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients have experienced unequal access to video telemedicine, and these services alone may not be adequate for acute conditions.31 Overall, our data highlight the urgent need to improve public health messaging and provide reassurance that hospitals are safe places to receive care.

The pandemic has also impacted the social determinants of health associated with cardiovascular risk.15–17 Racial and ethnic minority groups disproportionately experience poverty in the US,32 and 60% of Black and 72% of Hispanic households reported serious financial problems during the pandemic, compared with only 36% of White households.33 As a result of financial strain and job losses, Black and Hispanic households have experienced large increases in housing and food insecurity.34 Communities of color have also disproportionately been exposed to psychosocial stressors associated with the pandemic.16,35 These social risk factors, which collectively worsened for Black and Hispanic communities during the pandemic, have likely contributed to the disparate rise in cardiovascular deaths in these groups. The ensuing socioeconomic repercussions of the pandemic, coupled with delays in care, may also explain why heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths increased again for some racial/ethnic minority groups in July-August 2020.

Policy-level factors may have also contributed to worse cardiovascular outcomes during the pandemic. In early 2020, just prior to the onset of the US pandemic, the Trump administration implemented a revised “public charge” immigration rule. Under this policy, legal immigrants who used public benefits from the government, such as Medicaid insurance or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or were in poor health could be at risk of being denied permanent residency status.36 As a result, Hispanic and Asian immigrant families may have avoided seeking care for non-COVID-19-related illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease, due to concerns related to this policy.8,37,38 The extent to which the avoidance of healthcare systems, either due to fear of contracting COVID-19 and/or immigration concerns, contributed to the increase in heart disease and cerebrovascular deaths observed in our study remains an important area for future study.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, our analysis was based on provisional death counts from the NCHS, which may be incomplete in recent weeks due to reporting delays. To minimize the impact of reporting delays, we only analyzed data through August 2020. Second, although our analysis only included underlying causes of death due to heart or cerebrovascular diseases, and excluded underlying causes due to COVID-19, it is possible that undiagnosed cases of COVID-19 partially contributed to the increase in deaths. However, our analysis is consistent with observations from other nations, such as England and Wales, which have also experienced an increase in cardiovascular deaths due to the indirect effects of the pandemic.39,40 Third, the identification of race and ethnicity relied on death certification information, which may have been misclassified.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Black, Asian and Hispanic populations experienced a disproportionate rise in deaths due to heart disease and cerebrovascular disease compared with the non-Hispanic White population. These findings suggest that racial/ethnic minorities have been most impacted by the indirect effects of the pandemic. Public health and policy strategies are urgently needed to mitigate the short- and long-term adverse effects of the pandemic on the cardiovascular health of minority populations.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is New?

Although cardiovascular deaths increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, it is unclear whether racial and ethnic minority populations were disproportionately affected.

Our findings demonstrate that Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations each experienced a ≈20% relative increase in heart disease deaths, and an ≈13% relative increase in cerebrovascular disease deaths, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Racial and ethnic minority populations experienced a larger relative increase in heart disease and cerebrovascular disease deaths than the non-Hispanic White population.

Clinical Implications

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations experienced a disproportionate rise in deaths due to heart disease and cerebrovascular disease compared with non-Hispanic Whites, suggesting that racial/ethnic minorities have been most impacted by the indirect effects of the pandemic.

Public health and policy strategies are urgently needed to mitigate the short- and long-term adverse effects of the pandemic on the cardiovascular health of racial/ethnic minority populations.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at the NIH (K23HL148525)

Disclosures

Dr. Wadhera receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant K23HL148525) at the National Institutes of Health. He serves as a consultant for Abbott, outside the submitted work. Dr. Figueroa receives research support from the Commonwealth Fund, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Arnold Ventures, Harvard Center for AIDS Research, and Mass Consortium for Pathogen Readiness. Dr. Rodriguez has received consulting fees from Novartis, Janssen, NovoNordisk, and HealthPals unrelated to this work. Dr. Yeh receives research support from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL136708) and the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and receives personal fees from Biosense Webster, grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic, outside the submitted work. Dr. Joynt Maddox receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL143421) and National Institute on Aging (R01AG060935). All other authors have no disclosures.

Non-Standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ICD-10

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

Footnotes

Supplemental Materials

Supplemental Table I

Supplemental Figure I

References

- 1.Baum A, Schwartz MD. Admissions to Veterans Affairs Hospitals for Emergency Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020; 324:96–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt AS, Moscone A, McElrath EE, et al. Fewer Hospitalizations for Acute Cardiovascular Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman TJ, Wilson MA, Chiu ST, et al. Case Rates, Treatment Approaches, and Outcomes in Acute Myocardial Infarction During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Cardiol. 2020; 5:1419–1424. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, et al. The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadhera RK, Shen C, Gondi S, Chen S, Kazi DS, Yeh RW. Cardiovascular Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, et al. Variation in COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths Across New York City Boroughs. JAMA. 2020; 323:2192–2195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2534–2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Lee D, Yeh RW, Sommers BD. Community-Level Factors Associated With Racial And Ethnic Disparities In COVID-19 Rates In Massachusetts. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020:101377hlthaff202001040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Mehtsun WT, Riley K, Phelan J, Jha AK. Association of race, ethnicity, and community-level factors with COVID-19 cases and deaths across U.S. counties. Healthc (Amst). 2020;9:100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez F, Solomon N, de Lemos JA, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Presentation and Outcomes for Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19: Findings from the American Heart Association’s COVID-19 Cardiovascular Disease Registry. Circulation. 2020. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karan A, Wadhera RK. Healthcare System Stress Due to Covid-19: Evading an Evolving Crisis. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, D C, Scheider E. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Outpatient Visits: Changing Patterns of Care in the Newest COVID-19 Hot Spots. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/aug/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-visits-changing-patterns-care-newest. Published 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young MN, Iribarne A, Malenka D. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Health: This Is a Public Service Announcement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:170–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czeisler ME, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19-Related Concerns - United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadhera RK, Wang Y, Figueroa JF, Dominici F, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. Mortality and Hospitalizations for Dually Enrolled and Nondually Enrolled Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 65 Years or Older, 2004 to 2017. JAMA. 2020;323:961–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stress and Health Disparities. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/stress-report.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mensah GA. Socioeconomic Status and Heart Health-Time to Tackle the Gradient. JAMA Cardiol. 2020; 5:908–909. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Index of COVID-19 Surveillance and Ad-hoc Data Files. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/covid-19-mortality-data-files.htm. Published 2021. Accessed January 8, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.COVID-19 Death Data and Resources. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/covid-19.htm#understanding-death-data-quality. Published 2021. Accessed April 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumley T, Kronmal R, Ma S. Relative Risk Regression in Medical Research: Models, Contrasts, Estimators, and Algorithm. UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series. https://biostats.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1128&context=uwbiostat. Published 2006. Accessed April 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcello RK, Dolle J, Tariq A, et al. Disaggregating Asian Race Reveals COVID-19 Disparities among Asian Americans at New York City’s Public Hospital System. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2011.2023.20233155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu JN, Tsoh JY, Ong E, Ponce NA. The Hidden Colors of Coronavirus: the Burden of Attributable COVID-19 Deaths. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, et al. Trends in Blood Pressure Control Among US Adults With Hypertension, 1999–2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA. 2020;324:1190–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Heart Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health, United States Spotlight Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/spotlight/HeartDiseaseSpotlight_2019_0404.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed February 14, 2021.

- 26.Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta MRG, et al. Prevalence of Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA. 2019;322:2389–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asch DA, Sheils NE, Islam MN, et al. Variation in US Hospital Mortality Rates for Patients Admitted With COVID-19 During the First 6 Months of the Pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021.;181:471–478. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ro R, Khera S, Tang GHL, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Deferred for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Because of COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2019801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uy-Evanado A, Chugh HS, Sargsyan A, et al. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Response and Outcomes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology. 2020:1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fueled by COVID-19 fears, approximately half of Hispanics and Black Americans would fear going to the hospital if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or stroke. American Heart Association. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/fueled-by-covid-19-fears-approximately-half-of-hispanics-and-black-americans-would-fear-going-to-the-hospital-if-experiencing-symptoms-of-a-heart-attack-or-stroke#_ftn2. Published 2020. Accessed February 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, et al. Patient Characteristics Associated With Telemedicine Access for Primary and Specialty Ambulatory Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2031640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/. Published 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Impact of Coronavirus on Households, by Race/Ethnicity. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XoV6pqzvtag4E9YQeLRTvHaWAlN-s830/view. Published 2020. Accessed April 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Housing Insecurity by Race and Place During the pandemic. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/report/housing-insecurity-by-race-and-place-during-the-pandemic/. Published 2020. Accessed April 5, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, Garfield R. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. Published 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalid NS, Moore A. Immigration and Compliance Briefing: COVID-19 Summary of Government Relief and Potential “Public Charge Rule” Impact on Nonimmigrant and Immigrant Visa Applications. National Law Review. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/immigration-and-compliance-briefing-covid-19-summary-government-relief-and-potential. Published 2020. Accessed February 14, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page KR, Venkataramani M, Beyrer C, Polk S. Undocumented U.S. Immigrants and Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sommers BD, Allen H, Bhanja A, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Assessment of Perceptions of the Public Charge Rule Among Low-Income Adults in Texas. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2010391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J, Mamas MA, Mohamed MO, et al. Place and causes of acute cardiovascular mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heart. 2021;107:113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pell R, Fryer E, Manek S, Winter L, Roberts ISD. Coronial autopsies identify the indirect effects of COVID-19. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.