Abstract

Background:

Nurses are well positioned to initiate advance care planning (ACP) conversations because of their unique strength in communication and central patient-facing role in the interdisciplinary team. Nurse-led ACP conversations have demonstrated promising results in settings outside of the emergency department (ED). Understanding ED nurses’ perspectives regarding ACP conversations is needed before implementing similar practices in the ED.

Objective:

To explore ED nurses’ perception of facilitating ACP conversations.

Design:

We conducted a cross-sectional survey to assess ED nurses’ perceptions of facilitating ACP conversations in the ED.

Setting:

ED nurses at one academic hospital and one community hospital located within the northeastern region of the United States.

Results:

Seventy-seven (53.1%) out of 145 eligible ED nurses completed the survey. All participants perceived ACP conversations in the ED as at least somewhat important. Forty (51.9%) felt somewhat comfortable in facilitating these conversations. The majority of participants (77.9%) agreed that a specially trained nurse consultation model might be helpful in the ED. We found a correlation between total clinical experience and interest in facilitating ACP conversations in the ED (p = 0.045).

Conclusion:

ED nurses are well positioned to help patients clarify their goals-of-care and end-of-life care preferences. They perceived ACP conversations to be important and felt comfortable to facilitate them in the ED. Additional studies are needed to empirically test its implementation.

Keywords: advance care planning, ED GOAL, emergency medicine, motivational interview, nurse-led

Introduction

In older adults with serious life-limiting illnesses, advance care planning (ACP) conversations can lead to well-informed shared decision making and improved quality of life.1 Such conversations are associated with lower rates of in-hospital death, less aggressive medical care at the end of life, earlier hospice referrals, increased peacefulness, decreased stress and anxiety among caregivers, and a 56% greater likelihood to have end-of-life wishes known and followed.1–8 Yet only 37% of seriously ill older adults have ACP conversations with their clinicians, on average 33 days before death.9 During the last six months of life, 75% of older adults visit the emergency department (ED),10 signaling a more rapid decline in their illness trajectories.11–13 At this point, a strong impetus exists to motivate seriously ill older adults to seek ACP conversations.14

Our research team developed ED GOAL, a six-minute motivational interview to empower older adults in the ED to engage in ACP conversations, modeled from previously successful ED-based behavioral interventions.15–22 The intervention consists of establishing rapport with the patients, assessing their readiness to discuss ACP, and setting up the next steps of discussing ACP with their providers.21–23 A pilot study among 50 seriously ill older adults revealed that 83% of patients found the physician-led intervention acceptable and that it may have motivated them to engage in ACP conversations after leaving the ED.21,22 Yet physicians were often interrupted when they were conducting the pilot intervention22 and during regular clinical care,24–26 limiting its potential efficacy. At the same time, multiple nurses who witnessed ED GOAL with their patients expressed interest in performing ED GOAL.

Nurse-led ACP interventions have been shown to reduce patients’ decisional conflict and increase the documentation of care preferences.27 An international expert panel recommends the initiation of ACP by nonphysicians.28 Nurses may be well positioned to initiate ACP because they have a unique strength in communication skills,29 spend more time at the bedside, and perform motivational interviews as part of their scope of practice.30,31 Despite the theoretical advantages demonstrated in other clinical care settings, the empiric evidence for a nurse-led ACP intervention in the ED is lacking. Therefore, we sought to determine full-time clinical staff nurses’ perceptions regarding facilitating ACP conversations in the ED.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a survey to examine full-time ED nurses’ perceptions of facilitating ACP conversations in general in the ED at one academic and one community hospitals. We chose to only include full-time nurses in our study because we are hoping to identify ACP nurse champions within our department for future studies. Both EDs are located within the northeastern region of the United States with a total volume of 70,000 visits annually. This study was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board. We followed the STROBE criteria for reporting of our results.32

Participants and procedure

We included nurses who worked primarily in the ED setting at one of the sites. We excluded participants who identified as float or part-time nurses working <32 hours per week. Potential participants were identified by nursing directors. We requested that nursing directors of both EDs send out study recruitment e-mails with an electronic survey link of the study to the sites’ ED nursing e-mail distribution list. In addition, trained research assistants approached nurses to complete the survey in person, either online or on paper, over four weeks. Study data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies.33,34

Survey development

Because validated surveys to measure nurses’ perception of facilitating ACP conversations in the ED do not exist, a panel of experts with expertise in ED nursing care (B.B., N.A.E., and K.O.), nursing research (T.F.G. and D.L.B.), and ACP conversations in the ED (K.O.) designed the survey. The survey was iteratively refined in content and language used until the study team found it clinically relevant and acceptable for administration.

To measure nurses’ perceptions of facilitating ACP conversations, we used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 2 = slightly, 3 = somewhat, 4 = very, 5 = extremely) and a series of multiple-choice questions. In addition to nurses’ perceptions, we also assessed the prevalence of patients who would potentially benefit from ACP conversations in the ED and explored participants’ interest and comfort level in facilitating such conversations. Their perceptions of potential models for training nurses to assist patients with ACP conversations were also explored. We also collected demographic information of the nurse participants, including gender, age range, clinical experience, clinical certifications, and union membership status.

Statistical methods

For descriptive statistics, data were described as frequency and percentage. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the means of groups of nurses by gender and hospital sites (academic and community EDs), whereas Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for age groups and total clinical experience. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Version 24.35

Results

We identified 145 full-time (>32 work hours per week) nurses. Among the eligible nurses, 77 completed the survey (53.1% response rate). The reliability of the survey responses demonstrated the Cronbach’s α of 0.72. The study participants were primarily female (61, 79.2%), more than half were between 31 and 55 years of age (43, 55.8%), and 57 (74.0%) worked at the academic ED. Forty-five participants (58.4%) reported having had at least 10 years of total clinical experience. Most nurses had a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) (65, 84.4%), whereas one (1.3%) had a doctorate. Twenty-two (28.6%) had Certified Emergency Nurse (CEN) certification, and two were Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) certified. All (98.7%) but one participant were members of a nursing union (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ Characteristics

| Participants | Results (N = 77), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Female | 61 (79.2) |

| Age, years | |

| <31 | 18 (23.4) |

| 30–55 | 43 (55.8) |

| >55 | 16 (20.8) |

| Highest education | |

| ADN | 7 (9.1) |

| BSN | 65 (84.4) |

| Master’s | 4 (5.2) |

| DNP | 1 (1.3) |

| Clinical experience | |

| Total, years | |

| <5 | 13 (16.9) |

| 5–10 | 19 (24.7) |

| >10 | 45 (58.4) |

| ED | |

| <5 | 21 (27.3) |

| 5–10 | 18 (23.4) |

| >10 | 38 (49.4) |

| Nursing union | |

| Yes | 75 (98.7) |

ADN, Associate Degree in Nursing; BSN, Bachelor of Science in Nursing; DNP, Doctor of Nursing Practice; ED, emergency department.

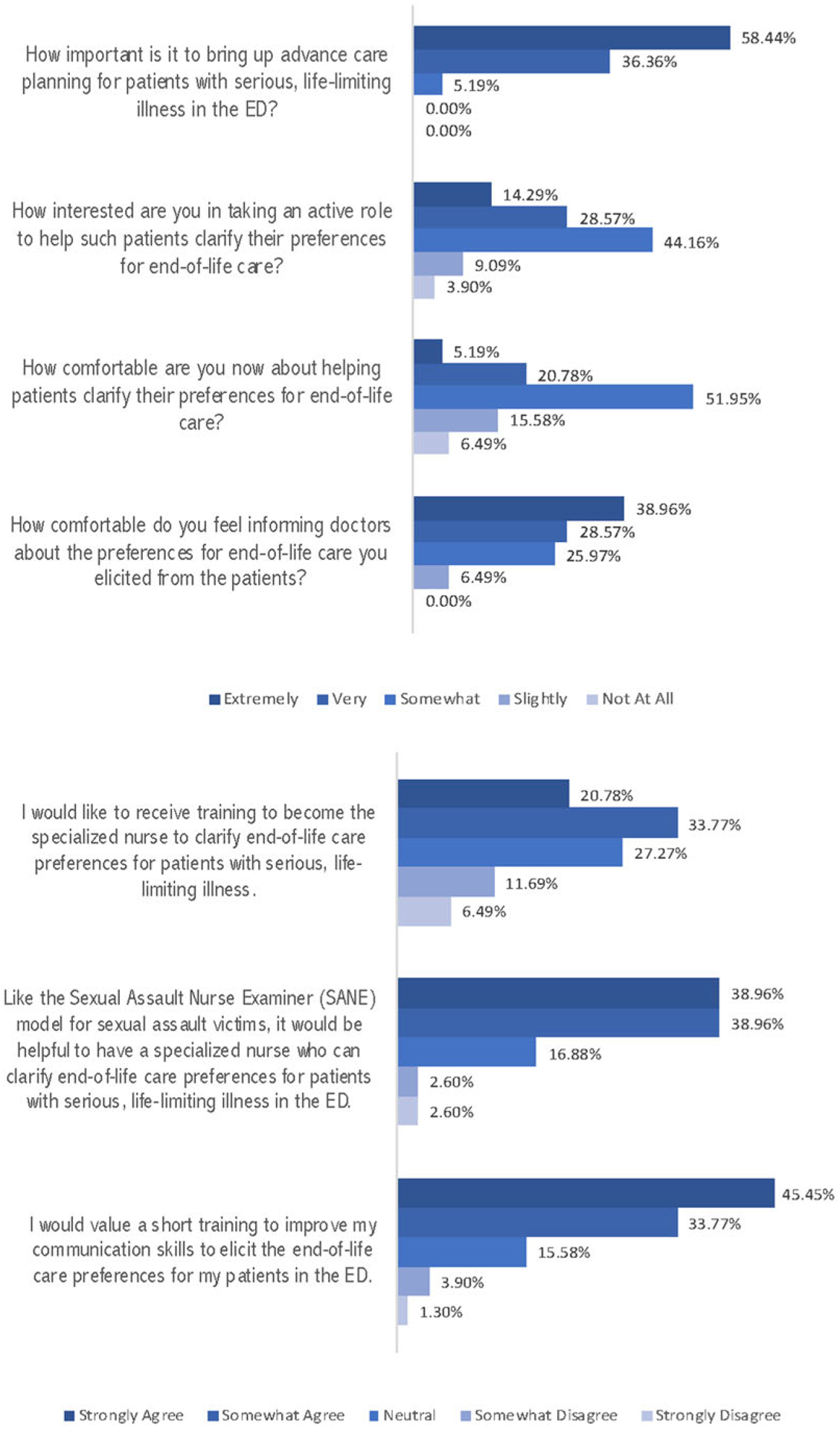

When asked about the frequency of encountering patients who would benefit from ACP conversations, most participants (51, 66.2%) responded that they encountered between 3 and 5 patients in a typical shift, whereas 12 participants (12, 15.6%) encountered 6 or more patients. All participants perceived the conversation as at least somewhat important to be discussed in the ED. Most nurses expressed an interest in taking an active role (67, 87.0%) to help patients clarify their end-of-life care preferences and to receive training to improve their communication skills in this area (61, 79.2%).

Forty nurses (51.9%) felt somewhat comfortable in helping patients clarify their preferences for end-of-life care. The majority of the participants (60, 77.9%) agreed that a specialized nurse model, akin to the existing SANE, would be helpful. All felt comfortable in informing physicians about the end-of-life preferences they obtained from patients (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Participant’s responses on advance care planning in the ED. ED, emergency department.

No significant differences were found when comparing the perceived interest and comfort in facilitating ACP conversations between the two sites in our studies, genders, and different age groups. Nurses’ interest to facilitate ACP conversations is associated with the different levels of total clinical experience χ2 (2) = 6.2, p = 0.045, with a mean rank interest score of 39.5 for nurses with <5 years, 28.8 between 5 and 10 years, and 43.1 with >10 years of total experience.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that ED nurses considered ACP conversations as at least “somewhat important” and were willing to play an active role in initiating such conversations. The respondents also recommended training to improve their communication skills to initiate ACP conversations. Early (<5 years) and later career nurses (>10 years) were more likely to be interested in facilitating ACP conversations than those between 5 and 10 years experience. We hypothesized that nurses who had between 5 and 10 years of experience might have more responsibilities at work and thus were less interested in participating in a new undertaking. The majority of the participants suggested a specially trained nurse consultation model would help conduct these difficult conversations in the ED.

National models for specially trained consultation nurses exist in the ED. Venous access nurses (i.e., nurses who insert ultrasound-guided intravenous access) and SANE are the most common examples. The SANE model has been shown to result in a higher quality of care than any other clinician in the ED for specific types of care.36–38 A specially trained nurse consultation model may be more practical than physicians-led or social workers-led models (social workers are often unavailable in most EDs). Furthermore, alternative training models in end-of-life care (e.g., End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium [ELNEC] curriculum and hospice and palliative care nurses certification39,40) may also be helpful. A study that looked at a nurse-led ACP program has been shown to lessen patients’ decisional conflict as well as increase the documentation of care preferences (e.g., advance directives and do not resuscitate orders in other clinical settings).27 Based on our study results, a nurse-led ACP intervention implemented as a specially trained nurse consultation model may be worth exploring. Future research should explore the feasibility of training a subgroup of ED nurses to become the specially trained nurses for ACP. If successful, the specialized board certification process based on competency with a train-the-trainer model could be established, similar to the SANE model.41

Our study has several limitations. The participants were recruited at one academic and one community hospital, which may have influenced their responses based on their clinical experience. The patient demographics that created the clinical experience at these hospitals were likely similar to other institutions in the United States. Participation bias captured more responses from nurses interested in ACP conversations. The responses are likely internally valid, given that we were primarily interested in the perceptions of such interested nurses in the ED. We are aware that only a subset of nurses may be interested in becoming specially trained in ACP conversations. The principal investigator is an attending emergency physician, so it is possible that the ED nurses’ responses, though deidentified, might be biased toward a more positive outlook.

Conclusion

ED nurses perceived ACP conversations as important and felt comfortable in facilitating them in the ED. Specially trained nurses may play a pivotal role in initiating these conversations with patients receiving care in the ED.

Acknowledgment

We thank Mr. Askar Myrzakhmetov for his assistance with data collection.

Funding Information

Kei Ouchi, National Institute of Aging, K76AG064434; Kei Ouchi, The Sojourns Scholar Leadership Program, Cambia Health Foundation.

Abbreviations Used

- ACP

advance care planning

- ADN

Associate Degree in Nursing

- BSN

Bachelor of Science in Nursing

- DNP

Doctor of Nursing Practice

- ED

emergency department

- SANE

Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Wright AA: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. : The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray A, Block SD, Friedlander RJ, et al. : Peaceful awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1359–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khandelwal N, Kross EK, Engelberg RA, et al. : Estimating the effect of palliative care interventions and advance care planning on ICU utilization: A systematic review. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1102–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakin JR, Block SD, Billings JA, et al. : Improving communication about serious illness in primary care: A review. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M: The economic evidence for advance care planning: Systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med 2015;29:869–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khandelwal N, Benkeser DC, Coe NB, et al. : Potential influence of advance care planning and palliative care consultation on ICU costs for patients with chronic and serious illness. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1474–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen MJ, Prigerson HG, Paulk E, et al. : Impact of end-of-life discussions on the reduction of Latino/non-Latino disparities in do-not-resuscitate order completion: Latino Disparities and DNR Order Completion. Cancer 2016;122:1749–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. : End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;156: 204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. : Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1277–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW, et al. : Short-term functional decline and service use in older emergency department patients with blunt injuries. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17:679–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Sabbe M, et al. : Characteristics of older adults admitted to the emergency department (ED) and their risk factors for ED readmission based on comprehensive geriatric assessment: A prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagurney JM, Fleischman W, Han L, et al. : Emergency department visits without hospitalization are associated with functional decline in older persons. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor AE, Winch S, Lukin W, et al. : Emergency medicine and futile care: Taking the road less travelled. Emerg Med Australas 2011;23: 640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WR: Motivational interviewing: Research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav 1996;21:835–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, et al. : A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, et al. : Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;77:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein E, Edwards E, Dorfman D, et al. : Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:1174–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruguera P, Barrio P, Oliveras C, et al. : Effectiveness of a specialized brief intervention for at-risk drinkers in an emergency department: Short-term results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Acad Emerg Med 2018;25: 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sommers MS, Lyons MS, Fargo JD, et al. : Emergency department-based brief intervention to reduce risky driving and hazardous/harmful drinking in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2013; 37:1753–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouchi K, George N, Revette AC, et al. : Empower seriously ill older adults to formulate their goals for medical care in the emergency department. J Palliat Med 2019;22:267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pajka SE, Hasdianda MA, George N, et al. : Feasibility of a brief intervention to facilitate advance care planning conversations for patients with life-limiting illness in the emergency department. J Palliat Med 2021;24: 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leiter RE, Yusufov M, Hasdianda MA, et al. : Fidelity and feasibility of a brief emergency department intervention to empower adults with serious illness to initiate advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:878–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chisholm CD, Collison EK, Nelson DR, et al. : Emergency department workplace interruptions: Are emergency physicians “interrupt-driven” and “multitasking”? Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Sherif N, Hawthorne HJ, Forsyth KL, et al. : Physician interruptions and workload during emergency department shifts. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet 2017;61:649–652. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chisholm CD, Dornfeld AM, Nelson DR, et al. : Work interrupted: A comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan HY, Ng JS, Chan KS, et al. : Effects of a nurse-led post-discharge advance care planning programme for community-dwelling patients nearing the end of life and their family members: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;87:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. : Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: An international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol 2017;18: e543–e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ke LS, Huang X, O’Connor M, et al. : Nurses’ views regarding implementing advance care planning for older people: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:2057–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dart MA: Motivational Interviewing in Nursing Practice: Empowering the Patient. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levensky ER, Forcehimes A, O’Donohue WT, et al. : Motivational interviewing: An evidence-based approach to counseling helps patients follow treatment recommendations. Am J Nurs 2007;107:50–58; quiz 58–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. : Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:W163–W194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. : Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. : The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.IBM Statistics for macOS. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell R, Patterson D, Lichty LF: The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs: A review of psychological, medical, legal, and community outcomes. Trauma Violence Abuse 2005;6: 313–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sievers V, Murphy S, Miller JJ: Sexual assault evidence collection more accurate when completed by sexual assault nurse examiners: Colorado’s experience. J Emerg Nurs 2003;29:511–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell R, Townsend SM, Long SM, et al. : Responding to sexual assault victims’ medical and emotional needs: A national study of the services provided by SANE programs. Res Nurs Health 2006;29: 384–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association: Certified Hospice and Palliative Nurse. https://advancingexpertcare.org/chpn. 2021. (Last accessed January 15, 2021).

- 40.American Association of Colleges of Nursing: End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC). https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC. 2021. (Last accessed January 15, 2021).

- 41.Ledray LE: Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Development & Operation Guide. Minneapolis, MN: Sexual Assault Resource Service, 1999. [Google Scholar]