Abstract

Public health measures enacted early in response to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in unprecedented physical isolation. Social isolation, or the objective experience of being alone, and loneliness, the subjective feeling of being lonely, are both implicated in suicidal ideation. Anxiety sensitivity (i.e., fear of somatic anxiety) and intolerance of uncertainty (distress due to uncertainty), may also be heightened in response to the pandemic increasing risk for suicidal ideation in response to social isolation and loneliness. The direct and interactive relations loneliness, anxiety sensitivity, and intolerance of uncertainty shared with suicidal ideation were examined using structural equation modeling across two samples. Sample 1 comprised 635 people (M age = 38.52, SD = 10.00; 49.0% female) recruited using Mechanical Turk in May 2020. Sample 2 comprised 435 people (M age = 34.92, SD = 14.98; 76.2% female) recruited from faculty, staff, and students at a midwestern university in June 2020. Loneliness and anxiety sensitivity were positively, uniquely associated with suicidal ideation across samples. Results of this study were cross-sectional and included only self-report measures. These findings highlight loneliness and anxiety sensitivity as important correlates of suicidal ideation. Modular treatments should be employed to target these mechanisms to reduce COVID-19-related suicidal ideation.

Keywords: COVID-19, Suicidal Ideation, Loneliness, Social Isolation, Anxiety Sensitivity, Intolerance of Uncertainty

1. Introduction

A novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was identified in November 2019 in Wuhan, China; it was classified as a pandemic in January 2020, and the first case was identified in the United States on January 20, 2020. As of July 17th, 2021, there are more than 33 million confirmed cases and over 600,000 dead in the United States (World Health Organization, n.d.). The COVID-19 pandemic is occurring on top of an ongoing suicide crisis. A recent report from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Hedegaard, 2020) found rates of suicide to have increased by 35% from 1999 to 2018. The COVID-19 pandemic may increase suicidality even further (Sher, 2020), particularly through the secondary consequences of physical distancing measures (Reger et al., 2020). Therefore, it is critical to consider the role of physical distancing requirements and the psychological consequences of these requirements in the ongoing suicide crisis.

The fluid vulnerability model of suicide (Rudd, 2006) was designed to explain the complicated temporal dynamics underlying the progression from non-suicidal to suicidal thoughts and actions. In this model, variables interact in complex patterns over time to influence the emergence of a high suicide risk state. Central to this theory is the suicide mode, which provides a framework for risk factors to influence the suicide risk state (Beck & Haigh, 2014). In this framework, there is an important distinction between chronic and imminent risk (Rudd, 2006). Certain risk factors predispose an individual to be more susceptible to environmental stressors and represent chronic risk factors. In this framework, suicide risk is dynamic, such that more severe stressors require less elevated predispositions to put an individual at an increased state of suicidal vulnerability. In the context of COVID-19, risk factors that amplify responses to environmental stress may be especially important to identify.

Social isolation and loneliness, conceptualized as perceived social isolation and dissatisfaction with current social interactions (Cacioppo et al., 2006), have been identified as longitudinal predictors of suicidal thoughts and behavior (Beutel et al., 2017; Calati et al., 2019; McClelland et al., 2020). Social isolation and loneliness are distinct constructs; social isolation refers to an objective lack of social contacts and loneliness refers to a subjective feeling (Beutel et al., 2017). However, imposed social isolation directly contributes to loneliness-like behavior in animal models and increased loneliness in experimental models with human participants (Cacioppo et al., 2015).

The unprecedented early steps taken to combat the effects of COVID-19, including stay at home orders in most states at some point from March to June 2020, have resulted in physical distancing requirements that have secondary and unavoidable impacts on social isolation as well. The impacts of these physical distancing requirements on loneliness are inconclusive. van Tilburg et al. (2020) found increased loneliness following physical distancing mandates in older adult Dutch community members. In contrast, in a nationwide sample of 1,545 American adults, Luchetti et al. 2020 found no differences in levels of loneliness assessed just prior to the outbreak, in late March and in late April. McGinty et al. (2020) compared rates of loneliness in nationally representative survey samples of US adults in April 2018 and April 2020; they found 11.0% reported feeling lonely often to always in 2018, rates that increased to 13.8% in 2020.

Despite the mixed findings regarding loneliness during the pandemic, there is increasing evidence that heightened feelings of loneliness influence psychological problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, loneliness correlated with depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder in a cross-sectional survey in the Spanish population (González-Sanguino et al., 2020). In a study of US citizens, stay at home order status was associated indirectly with suicide risk through thwarted belongingness (Gratz et al., 2020), reflecting both loneliness and lack of social support (Van Orden et al., 2012). Although loneliness was associated with suicide risk, this effect did not hold in the presence of thwarted belongingness. This is likely because thwarted belongingness and loneliness are highly overlapping, as indicated by a correlation of .86 in this study (Gratz et al., 2020). Therefore, the limited evidence on social isolation and loneliness suggests these are important potential risk factors for suicide during and after the pandemic.

The fluid vulnerability model posits that triggering of a suicidal vulnerability state is enhanced when there are many potential risk factors at play (Rudd, 2006). This aligns with calls for research exploring specific risk factors that might exacerbate the experience of loneliness on mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (Luchetti et al., 2020). Anxiety sensitivity (AS) refers to the fear of somatic anxiety due to the belief that anxiety sensations are harmful (Reiss et al., 1986). AS is multidimensional, comprising fear of physical, cognitive, and observable anxiety sensations, including fears of health-related concerns such as shortness of breath (Allan, Capron, et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2007). AS is posited to amplify distress responses (Reiss, 1991). Drawing from this, Capron and colleagues proposed the depression-distress amplification model, such that AS concerning cognitive dyscontrol would modulate the relation between depression and suicidal thoughts and behavior (Capron et al., 2012, 2015). However, Allan et al. (2015) provided evidence that the common variance across AS dimensions explained the bulk of the relations between AS and suicide outcomes. In support of the theoretical association between AS and suicide, a recent meta-analysis by Stanley and colleagues (2018) reported AS shared small-to-medium associations with suicidal ideation (r = .24) and suicide risk (r = .35). Relative to the pandemic, McKay et al. (2020) reported that AS physical concerns was significantly associated with fear of contracting COVID-19.

Intolerance of uncertainty (IU) is another risk factor highly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic (Satici et al., 2020). IU is “an individual’s dispositional incapacity to endure the aversive response triggered by the perceived absent of salient, key, or sufficient information, and sustained by the associated perception of uncertainty” (p. 31, Carleton, 2016). Although there is little work exploring the association between IU and suicide, Ciarrochi et al. (2005) found that undergraduates high in IU were also high in suicidal ideation and hopelessness, among other factors. In addition, Parlapani et al. (2020) found that elevated IU was associated with loneliness in older adults during the pandemic. In a cross-sectional study of a majority-US sample, Smith et al. (2020) found IU moderated the association between perceived social isolation and reported distress due to COVID-19. Considering the unprecedented degree of uncertainty because of the pandemic, it is crucial to explore how IU is related to loneliness and suicidality at this time.

We designed the current study to examine the unique and synergistic relations that social isolation (i.e., time under stay at home order), loneliness, AS, and IU share with suicidal ideation. Based on prior findings, we expected to find loneliness and AS would be associated with suicidal ideation (McClelland et al., 2020; Stanley et al., 2018). We tentatively hypothesized that IU would also be associated with suicidal ideation, given that this could be considered another risk factor through the lens of the fluid dynamic model (Rudd, 2006). We further tested whether AS and IU would interact with loneliness, such that the relation between loneliness and suicide would be more elevated in individuals with elevated AS and IU. This hypothesis was considered exploratory. Finally, we examined whether the relations between loneliness, AS, IU, and suicidal ideation remained when accounting for COVID-19 distress. We conducted structural equation modeling (SEM) and tested the proposed model across two samples to provide a robust test of our hypothesized relations. SEM was utilized to address the planned missingness design and because SEM is robust to measurement error compared to regression-based approaches (Crowley & Fan, 1997).

2. Method -- Study 1

2. 1. Participants

Participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk) to participate in a larger online longitudinal study using Cloudresearch to launch the study and screen participants (Litman et al., 2017). Eligibility criteria required that participants be at least 18 years of age, located in the United States, and proficient in English, with HIT approval rates (i.e., proportion of participant surveys approved by requestors) > 95% (minimum 100 surveys). Recruitment materials indicated that the study was investigating daily life experiences and the ability to cope with uncertainty. The data used in the present analysis were from the baseline administration of the questionnaires, which occurred between April 29th 2020 and May 2nd 2020. The final sample contained 635 participants (M age = 38.52, SD = 10.00; 49.0% female; see Table 1 for sample demographics).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics across samples

| Sample 1 N = 635 | Sample 2 N = 435 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographic Characteristics | M (SD) | |

| Age | 38.52 (10.00) | 34.92 (14.98) |

|

|

||

| N (%) | ||

|

|

||

| Gender/Sex at birth | ||

| Male | 323 (50.9%) | 99 (22.9%) |

| Female | 311 (49.0%) | 330 (76.2%) |

| Other | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Race | ||

| White or Caucasian | 520 (81.9%) | 398 (91.5%) |

| Black or African American | 77 (12.1%) | 13 (3.0%) |

| Asian | 44 (6.9%) | 11 (2.5%) |

| American Indian/Native American/Alaskan Native | 13 (2.0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Other | 6 (0.9%) | 8 (1.8%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.2%) | 8 (1.8%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 71 (11.2%) | 14 (3.2%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 556 (87.6%) | 406 (94.0%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (1.3%) | 12 (2.8%) |

| Estimated Yearly Family Incomea | ||

| < $10,000 | 14 (2.2%) | 30 (6.9%) |

| $10,000-25,000 | 58 (9.1%) | 50 (11.5%) |

| $25,000-40,000 | 94 (14.8%) | 48 (11.1%) |

| $40,000-75,000 | 218 (34.3%) | 110 (25.3%) |

| $75,001-100,000 | 126 (19.8%) | 61 (14.1%) |

| $100,000-150,000 | 75 (11.8%) | 68 (15.7%) |

| >$150,000 | 41 (6.5%) | 43 (9.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 9 (1.4%) | 24 (5.5%) |

Note. Participants could select more than one race option, therefore the percentages are non-mutually exclusive.

Ranges were inadvertently calculated overlapping by $1.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. COVID-19 Impact.

In addition to their demographic characteristics, COVID-19 impact statistics were gathered, including exposure to COVID-19, perceived risk of infection and impact on finances, health, community, and sense of social connection.

2.2.2. Coronavirus Impact Battery (CIB) Worry Scale (Schmidt et al., 2020).

The CIB Worry scale is a multidimensional scale, capturing Financial, Health, and Catastrophizing Worries in response to the COVID-19 outbreak across 11 items. The items on this measure use a five-point scale (from 0 = Not at all to 4 = Very Much). Participants used this scale to rate each item (e.g., “I worry that I will lose my employment;” “I worry that I will lose motivation”) based on the degree to which it has caused distress. This scale demonstrated acceptable internal and test-retest reliability and acceptable validity (Schmidt et al., 2020). This scale demonstrated excellent reliability in Sample 1 (ω = .95).

2.2.3. The 5-item NIH Toolbox Loneliness Scale (Cyranowski et al., 2013).

The five-item NIH Toolbox Loneliness Scale within the Social Relationship Assessment Battery was used to assess loneliness. Participants were asked to consider how much each item related to loneliness applied to them in the past month. Each item is scored on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The Loneliness Scale has demonstrated excellent reliability and convergent and discriminant validity (Cyranowski et al., 2013). This scale also demonstrated excellent reliability in Sample 1 (ω = .95).

2.2.4. Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3; Taylor et al., 2007).

The ASI-3 is an 18-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess feared consequences of sensations associated with anxious arousal (Taylor et al., 2007). The ASI-3 is composed of three lower-order dimensions: physical, cognitive, and social concerns. Respondents were asked to rate the degree to which they agree with each statement using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Very little) to 4 (Very much). The ASI-3 demonstrated excellent reliability in Sample 1 (ω = .91).

2.2.5. Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 (IUS-12; Carleton et al., 2007).

The IUS-12 is a 12-item self-report measure of individuals’ tolerance of, responses to, and beliefs regarding uncertainty (Carleton et al., 2007). The IUS-12 is composed of two lower-order dimensions, IU prospective and IU inhibitory. Respondents were asked to rate the degree to which they agree with each statement using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not at all a characteristic of me) to 5 (Entirely characteristic of me). The IUS-12 is a reliable and valid measure of IU (Carleton et al., 2007; 2012) and demonstrated adequate reliability in Sample 1 (ω = .70).

2.2.6. Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS; Watson et al., 2012).

The IDAS is a 64-item measure of psychopathology symptoms. Participants rate each item based on how much they felt or experienced things in the way that they were described in the past two weeks. The ratings range from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely) on a five-point Likert-type scale. The IDAS assesses psychopathology through a variety of different dimensions: dysphoria, well-being, panic, cleaning, lassitude, insomnia, suicidality, social anxiety, ill temper, mania, euphoria, claustrophobia, ordering, traumatic intrusions, checking, appetite loss, and appetite gain. The five-item suicidality subscale was used to assess suicidal tendencies, including self-harm and thoughts of death. This subscale demonstrated poor reliability in Sample 1 (ω = .65) but excellent reliability in Sample 2 (ω = .95).

2.3. Procedure

The study was posted to MTurk via CloudResearch (cloudresearch.com), an online crowdsourcing platform linked to MTurk that provides additional data collection features (e.g., creating selection criteria (Chandler et al., 2019). Participants who selected the survey link embedded in the Mturk study page were directed to a Qualtrics survey webpage containing details about the study. Those who checked on a box indicating that they were providing informed consent to participate were then directed to a battery of questionnaires. Study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and the study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Completion of the surveys took 54.37 minutes to complete on average (SD = 50.75 minutes). A planned missingness design which randomly presented 75% of most measures to participants was used in this sample based on recommendations by Rhemtulla & Little (2012) to increase the number of constructs assessed without sacrificing participant response quality. Previous research has demonstrated that planned missingness designs increase response quality, and lead to similar levels of missing data compared to standard survey designs (Rhemtulla & Little, 2012). Participants were randomly given 80% of scales other than the CIB Worry scale. Participants were compensated $4.25 for completing the online measures and an additional $1.25 if they had a child between the ages of 4 and 11 and agreed to complete an additional set of measures not used in the current study. Due to proliferation of “bot” or unreliable responses in MTurk sampling, we utilized three attention check questions throughout the survey. Only participants who completed all three of these questions were included in the sample (N = 634).

2.4. Data analytic plan

A series of structural equation models (SEMs) were fit to the data to examine the relations that the Loneliness, AS, and IU factors shared with the IDAS Suicidality factor. Age, biological sex, and reported outbreak size were included as covariates. Age and sex were included as covariates as age has been shown to be associated with loneliness (Barreto et al., 2021) and AS (Zvolensky et al., 2018), and sex has shown to be associated with AS (Stewart et al., 1997) and IU (Robichaud et al., 2003). Reported outbreak size was included as a covariate to isolate the effects of subjective loneliness, above and beyond an objective measure of loneliness (i.e., degree of isolation due to COVID). Interactions between the Loneliness factor and the AS and IU factors were tested and retained if statistically significant. In all models, higher order factors of AS, represented by three lower order factors of AS (cognitive AS, physical AS, social AS), and IU, represented by two lower order factors of IU (prospective IU and inhibitory IU) were specified. In addition, a second set of models were run that included a latent COVID Worry factor as a covariate. Items used to model the independent variables were treated as continuous. Items underlying the IDAS Suicidality factor were treated as categorical due to the skewed nature of response to suicide questionnaires in community samples. The Means and Variance-Adjusted Weighted Least Squares (WLSMV in Mplus) was used to estimate the model. Model fit was assessed through various fit indices, including the adjusted chi square (χ2), root comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the RMSEA. A statistically non-significant χ2 indicates that the model fit the data well. In addition, CFI values above .90 and .95 indicate adequate and good fit, respectively. RMSEA CI values below .05 suggest that good fit cannot be ruled out, whereas an RMSEA above .10 suggests that poor fit cannot be ruled out (Hu & Bender, 1998). Due to the use of latent variables, interactions were analyzed using the XWITH command in Mplus, using procedures outlined in Asparouhov and Muthen (2019). Models were scaled by fixing factor variances to 1. Because WLSMV uses listwise deletion, the final model was re-analyzed using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) to examine sensitivity of the findings to data missingness. However, results did not differ substantively; therefore, models using WLSMV are reported below. All analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017).

3. Results -- Study 1

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for all variables are provided in the top panel of Table 3. Aside from the items capturing Suicidality, all items fell below thresholds indicating potential problems with skew and kurtosis in simulation studies (i.e., skew values > |2|, kurtosis values > |7|; Curran et al., 1996). To correct for skewness in the Suicidality latent factor, all items for that factor were treated as categorical. Finally, each item for AS, IU, and loneliness had between 20 to 23% missing data due to the planned missingness design.

Table 3.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of study variables across Sample 1 and Sample 2.

| Sample 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Suicidality | ||||||||

| 2. ASI-3 | .76*** | |||||||

| 3. IUS-12 | .53*** | .76*** | ||||||

| 4. Loneliness | .61*** | .69*** | .56*** | |||||

| 5. Age | −.11** | −.16*** | −.09* | −.12*** | ||||

| 6. Sex | −.25*** | −.07 | −.02 | −.01 | .07 | |||

| 7. Stay at home | −.05 | −.02 | .01 | .001 | .06 | .03 | ||

| 8. CIB-Worry | .72*** | .84*** | .55*** | .68*** | −.13** | −.05 | .04 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (% Female) | 9.04 | 21.37 | 32.90 | 11.49 | 38.52 | 49.0% | 3.51 | 4.27 |

| SD | 11.84 | 20.92 | 12.24 | 6.75 | 9.99 | 1.49 | ||

| Sample 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|

| ||||||||

| 1.Suicidal Ideation | ||||||||

| 2. ASI-3 | .67*** | |||||||

| 3. IUS-12 | .49*** | .82*** | ||||||

| 4. Loneliness | .62*** | .64*** | .58*** | |||||

| 5. Age | −.42*** | −.36*** | −.38*** | −.40*** | ||||

| 6. Sex | .17 | .21** | .23** | .09 | −.13* | |||

| 7. Stay at home | .09 | .05 | .05 | −.03 | .04 | .07 | ||

| 8. CIB-Worry | .71*** | .96*** | .76*** | .75*** | .28*** | .24* | .001 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (% Female) | 0.41 | 22.87 | 32.69 | 14.24 | 34.92 | 75.9% | 1.51 | 4.32 |

| SD | 0.81 | 20.29 | 10.82 | 10.45 | 14.98 | 2.22 | 3.07 | |

Note. ASI-3 = Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. IUS-12 = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12. Loneliness = PROMIS loneliness scale. Stay at home = Stay at home status. Sex was coded as a 0 or 1 (female) binary in both samples. IDAS Suicidality includes items assessing suicidal ideation as well as items assessing desire for self-harm.

= p < .05.

= p < .01.

= p < .001.

Regarding participants’ perception of the approximate size of the COVID-19 outbreak in their area, the largest percentage (21.3%) of respondents indicated a “Medium” outbreak (see Table 2 for COVID-19 sample characteristics). Regarding the perceived threat of COVID-19 on participants’ health or the health of their loved ones, the largest proportion of respondents (34.6%) indicated there to be “Some” threat. Similarly, regarding the impact of COVID-19 on one’s finances, the largest proportion of participants (31.2%) indicated there to be “Some” impact. Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on participants’ sense of social connection, the largest proportion of participants (38.1%) also indicated there to be “Some” impact. The majority (87.6%) of respondents indicated that they were currently under a stay-at-home order and, of those, the largest proportion (47.9%) reported being under that order for 4-6 weeks.

Table 2.

COVID-19 participant characteristics

| Sample 1 N = 635 | Sample 2 N = 435 | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Yes (N [%]) | ||

| COVID-19 Screening (modal date) | ||

|

| ||

| Have you been diagnosed with COVID-19? | 11 (1.7%) | 6 (1.4%) |

| Do you think you have COVID-19, but have not been tested/diagnosed? a | 23 (3.7%) | 28 (6.5%) |

| Have you been exposed to someone who has confirmed COVID-19? | 42 (6.6%) | 25 (5.7%) |

| Have you been exposed to someone who has been tested for COVID-19 but is awaiting the results? | 38 (6.0%) | 25 (5.7%) |

| Has anyone in your home contracted COVID-19? | 11 (1.7%) | 10 (2.3%) |

| Does your job require contact with people affected with COVID-19? b | 39 (8.3%) | 29 (7.9%) |

| Do you have any medical conditions that puts you at an elevated risk for COVID-19? | 101 (15.9%) | 129 (29.7%) |

| Do you smoke or vape? | 130 (20.5%) | 71 (16.3%) |

|

| ||

| COVID-19 Real or Perceived Threat | ||

|

| ||

| What is the approximate size of the COVID-19 outbreak in your area? | ||

| No cases | 5 (0.8%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Very small | 79 (12.5%) | 162 (37.3%) |

| Small | 117 (18.5%) | 129 (29.7%) |

| Small to medium | 125 (19.7%) | 47 (10.8%) |

| Medium | 135 (21.3%) | 38 (8.8%) |

| Medium to large | 91 (14.4%) | 30 (6.9%) |

| Large | 50 (7.9%) | 17 (3.9%) |

| Very large | 32 (5.0%) | 8 (1.8%) |

| Are you currently under a “stay at home” or “shelter in place” order? | 556 (87.6%) | 141 (32.4%) |

| If yes, for how long have you been under that order? | ||

| 0-1 week | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (2.1%) |

| 1-2 weeks | 11 (2.0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| 2-4 weeks | 104 (18.7%) | 4 (2.8%) |

| 4-6 weeks | 304 (54.7%) | 27 (19.1%) |

| 6-8 weeks | 136 (24.5%) | 106 (75.2%) |

Note. Except for the two questions denoted with superscript “a” and superscript “b”, all other discrepancies in sample sizes were due to missingness.

This question was only asked of participants who indicated that they did not have a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis.

This question was only asked of participants who indicated that they were currently employed.

3.2. Structural Equation Model between Loneliness, AS, IU, and Suicidality

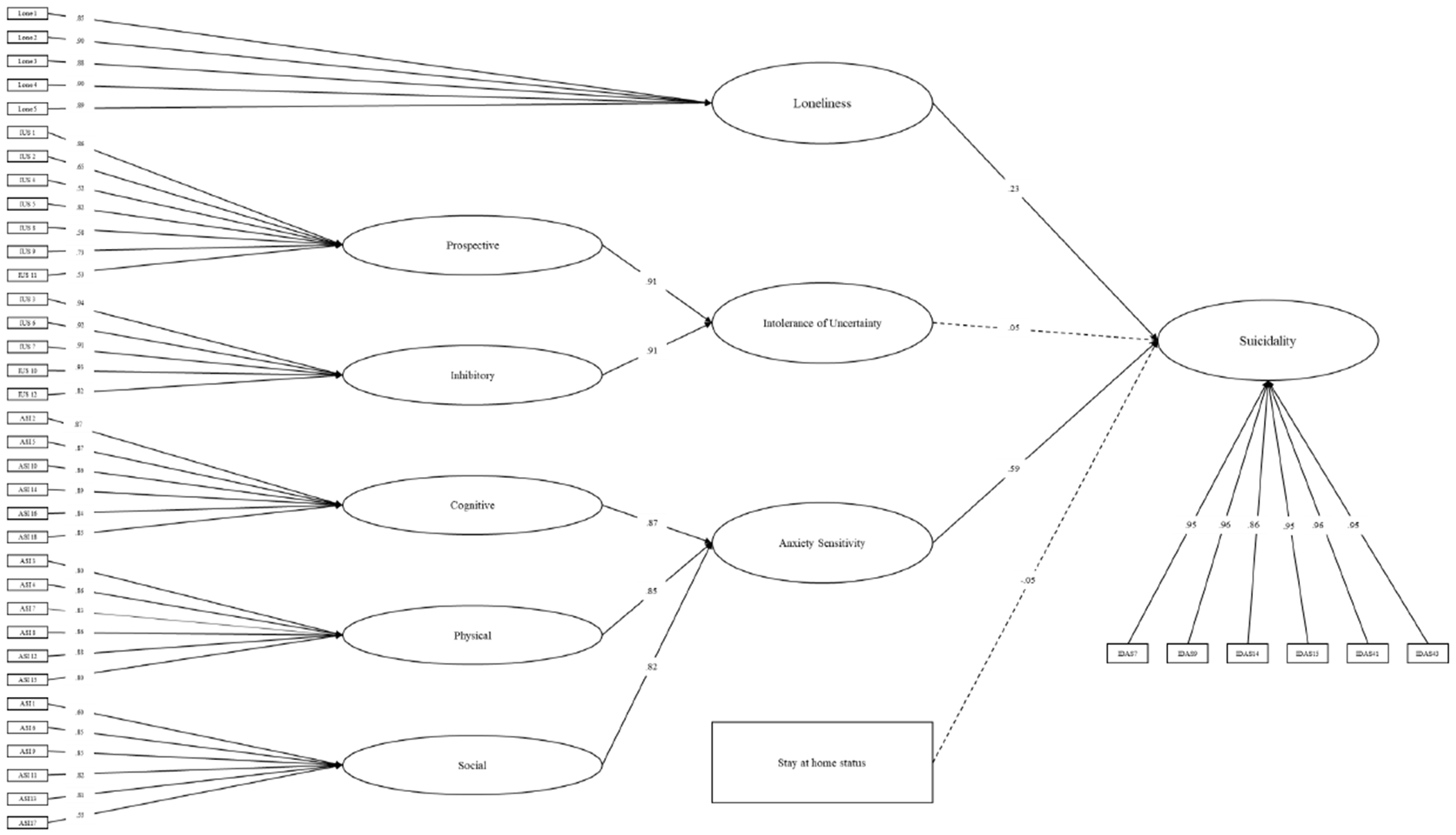

The SEM examining the relations that the Loneliness, AS, and IU factors share with the Suicidality factor, controlling for time under stay at home order status, age, and biological sex (0 = Male) provided adequate fit to the data (χ2 = 1547.21, df = 889, p < .001, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI [.03, .04]). There were no statistically significant latent variable interactions; interaction terms were therefore not included for model parsimony. In this model (see Figure 1), Loneliness (β = .23, p < .001) and AS (β = .59, p < .001) were each uniquely and positively associated with Suicidality. This model accounted for 74.3% of variance in Suicidality.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model examining the relations between the Anxiety Sensitivity, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Loneliness factors and the Suicidality factor. All reported effects are standardized. Statistically significant associations are captured by solid lines in the figure. Statistically non-significant associations are captured by dashed lines.

This model was re-examined after including a latent variable assessing COVID-19 Worry as an additional covariate. The model including this additional covariate provided marginal to adequate fit to the data (χ2 = 1756.66, df = 1017, p < .001, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .03, 90% CI [.03, .04]). The COVID-19 Worry factor was significantly, positively associated with Suicidality (β = .55, p < .001). Loneliness remained associated with Suicidality (β = .13, p < .05). However, AS (β = .12, p = .39) was no longer associated with Suicidality. In addition, the relation between IU and Suicidality (β = .17, p < .05) was statistically significant. In this model, there was a high inter-correlation (r = .86) between the AS factor and the COVID-19 Worry factor. This model accounted for 82.5% of variance in Suicidality.

4. Method -- Study 2

4.1. Participants

Participants were recruited from a small midwestern university (Ohio University) through an email to all faculty, staff, and students. Recruitment materials indicated that the study was investigating the ways the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic fallout have impacted mental health. Eligibility criteria required that participants be at least 18 years of age, located in the United States, proficient in English, and have access to the internet. The final sample was collected between May 23rd 2020 and July 2nd 2020 and contained 435 participants (M age = 34.92, SD = 14.98; 76.2% female; see Table 1 for sample demographics).

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. COVID-19 Demographic Characteristics.

Characteristics of Sample 2 participants were gathered, including exposure to COVID-19, perceived risk of infection and impact on finances, health, community, and sense of social connection. Information about behaviors being used in response to the COVID-19 outbreak were also gathered.

4.2.2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001).

The PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report scale used to assess depressive symptoms. The items on this measure use a five-point scale (from 0 = Not at all to 4 = Nearly every day). Participants used this scale to rate the degree to which each problem has been bothersome over the course of the past two weeks. The final item, that measuring “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself,” was used to assess suicidal tendencies.

4.2.3. Coronavirus Impact Battery (CIB) Worry Scale (Schmidt et al., 2020).

The CIB Worry scale demonstrated excellent reliability in Sample 2 (ω = .95).

4.2.4. The 5-item NIH Toolbox Loneliness Scale (Cyranowski et al., 2013).

This scale demonstrated excellent reliability in Sample 2 (ω = .93).

4.2.5. Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3; Taylor et al., 2007).

The ASI-3 scale demonstrated excellent reliability in Sample 2 (ω = .93).

4.2.6. Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 (IUS-12; Carleton et al., 2007).

This scale demonstrated excellent reliability (ω = .94).

4.3. Procedure

Recruitment for this study was sent via an advertisement to BLINDED FOR REVIEW faculty, staff, and students. Participants who selected the survey link embedded in the recruitment email were directed to a Qualtrics survey webpage containing details about the study. Those who checked on a box indicating that they were providing informed consent to participate were then directed to a battery of questionnaires. Study procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and the study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Completion of the surveys took 46.59 minutes to complete on average (SD = 30.83 minutes). Participants volunteered their participation in this study and were not monetarily compensated.

4.4. Data Analytic Plan

Analyses for Sample 2 followed the same procedures as in Sample 1. Suicidal ideation was measured from a single item from the PHQ-9 in Sample 2. Unstandardized model parameters are reported for Sample 2.

5. Results – Sample 2

5.1. Descriptive statistics

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of all variables are provided in Table 3. Aside from the single item assessing suicidal ideation (PHQ-9 item 9), all items fell within values found to not be problematic in simulation studies (i.e., skew values < |2|, kurtosis values < |7|; (Curran et al., 1996)). Due to significant skew in the manifest suicidal ideation variable, this variable was treated as a binary variable (i.e., 0 = absent, 1 = present). Finally, each item for AS had between 20 to 23% missing data due to the planned missingness design of the data.

Regarding participants’ perception of the approximate size of the COVID-19 outbreak in their area, the largest percentage (42.4%) of respondents indicating a “Very Small” outbreak (see Table 2 for COVID-19 sample characteristics). Regarding the perceived threat of COVID-19 on participants’ health or the health of their loved ones, the largest proportion of respondents (43.7%) indicated there to be “Some” threat. Similarly, regarding the impact of COVID-19 on one’s finances, the largest proportion of participants (38.5%) indicated there to be “Some” impact. A similar number of respondents (30.0%) indicated COVID-19 to be impacting their sense of social connection “Some” or “Much”. Less than half (47.0%) of respondents indicated that they were currently under a stay at home order and of those, a majority (73.2%) reported being under that order for 6-8 weeks.

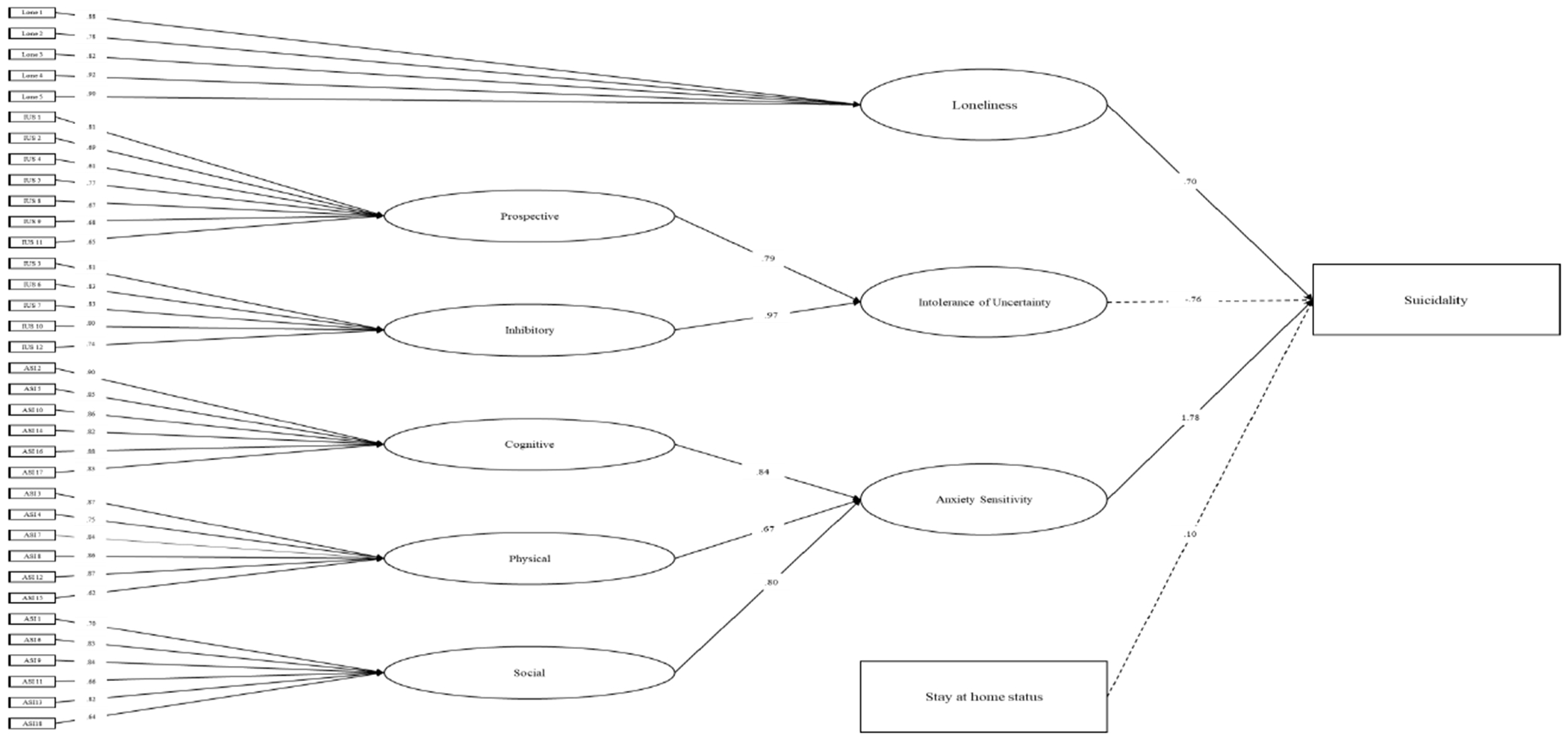

5.2. Structural equation model of main effects

The SEM examining the relations that the Loneliness, AS, and IU factors shared with the manifest suicidal ideation item, controlling for stay-at-home status, age, and biological sex (0 = Male) provided poor fit to the data (χ2 = 1685.49, df = 689, p < .001, CFI = .67, RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [.06, .06]). Examining modification indices led to the inclusion of a covariance between age and the Loneliness, AS, and IU factors and a correlation between the residual variances for IU items 4 and 11. This model resulted in improved, albeit marginal model fit to the data (χ2 = 1048.04, df = 687, p < .001, CFI = .88, RMSEA = .04, 90% CI [.03, .04]). There were no statistically significant latent variable interactions; interaction terms were therefore not included for model parsimony. Figure 2 contains unstandardized model parameter estimates. Loneliness (B = 0.32, p < .001, OR = 1.38) and AS (B = 0.61, p < .001, OR = 1.84) were uniquely and positively associated with suicidal ideation. IU was uniquely and negatively associated with suicidal ideation (B = −0.26, p = .037, OR = .77). This model accounted for 55.4% of the variance in suicidal ideation.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model examining the relations between the Anxiety Sensitivity, Intolerance of Uncertainty, and Loneliness factors and suicidal ideation. All reported effects are unstandardized and can be exponentiated to provide odds ratios. Statistically significant associations are captured by solid lines in the figure. Statistically non-significant associations are captured by dashed lines.

This model was re-examined including a latent variable assessing COVID Worry as an additional covariate. This model provided marginal model fit (χ2 = 1490.47, df = 800, p < .001, CFI = .79, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.04, .05]). Loneliness (B = .31, p < .001, OR = 1.36) and AS (B = .57, p < .001, OR = 1.77) were uniquely and positively associated with suicidal ideation, after controlling for COVID worry. IU (B = −.26, p = .041, OR = .77) was uniquely and negatively associated with suicidal ideation. The COVID Worry factor was not significantly associated with suicidal ideation (B = .07, p = .28). This model accounted for 55.8% of the variance in suicidal ideation.

6. Discussion

We designed the current study to examine the relations that loneliness, AS, and IU shared with suicidal ideation during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., May to July, 2020) in the US. Across samples, loneliness and AS were uniquely associated with suicidal ideation, controlling for IU, demographic characteristics, and time under stay at home orders. IU shared a bivariate association with suicidal ideation, but this effect did not remain statistically significant in the presence of AS and loneliness. The variance captured by AS appeared to overlap with variance capturing distress due to COVID-19. Taken together, these results provide support for loneliness and AS as unique risk factors associated with suicidal ideation.

Across both samples, levels of loneliness and AS were higher than levels of these constructs prior to the pandemic in community-recruited samples using the same measures. AS means in this study (M sample 1 = 21.37; M sample 2 = 22.87) fall between scores observed in nonclinical (M = 12.8) and clinical samples (Ms = 26.3-32.6; Taylor et al., 2007). Factor mixture modeling (FMM) studies can be used to determine ideal cut-points between groups of people based on their scores on a measure. Across FMM studies (Allan, Korte, et al., 2014; Allan, Raines, et al., 2014), scores of 17 or higher indicate moderate to severe levels of AS. In our studies, 37.2 to 39.5% of people exceeded this cut-score, compared to approximately 20% in prior community-based AS studies. For loneliness, the majority of participants endorsed scores falling at least 1 SD above average loneliness levels (63.1% in sample 1, 83.5% in sample 2), suggesting a need for heightened surveillance or concern according to the NIH Toolbox Scoring and Interpretation Guide (Cyranowski et al., 2013). Finally, IU scores in the current study (M sample 1 = 32.90; M sample 2 = 32.69) were elevated compared to average scores observed in undergraduate (Ms = 25.85-27.52) and community samples (M = 29.53; Carleton et al., 2007, 2012) but were lower than mean levels observed in clinical samples (Ms = 37.01-43.04; Carleton et al., 2012). Together, these findings highlight heightened trait risk factors associated with suicidal ideation, particularly loneliness and AS during the pandemic.

Subjective feeling of loneliness, and not length of time under a stay at home order, was associated with suicidal ideation. These results are consistent with the recent findings of Gratz et al. (2020), also in a sample of individuals experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic, who found statistically significant correlations between loneliness and suicide risk (r = .30, p < .001) but not stay at home status and suicide risk (r = −.04, p > .05). Although a recent narrative review by Calati et al. (2019) found both social isolation and subjective loneliness contributed to suicide risk, social isolation in the studies they reviewed was measured at an individual level and not at the local and regional level. Results of the present study suggest that it is the subjective state of loneliness and not social distancing orders that contribute to suicidal vulnerability.

The finding that AS was uniquely related to suicidal ideation is consistent with a recent meta-analysis by Stanley et al. (2018). One explanation for this may be that fear of COVID-19 may have increased monitoring of bodily sensations, particularly due to fear that the sensations could be catastrophic. Results across the two samples in the current study support this supposition. It appears that AS and Worry due to COVID-19 might be accounting for similar variance in suicidal thoughts. That is, AS was no longer significantly associated with suicidality when including COVID-19 worry. In Sample 2, COVID-19 worry was not significantly associated with suicidality when including AS. Further, these factors correlated highly across samples (r = .86 to .93). Together this suggests that fear of bodily sensations might be mechanistically involved in the relations between COVID-19 Worry and suicide risk.

In contrast to our hypotheses, IU was not uniquely associated with suicidal ideation. Prior studies have found unique relations between IU and suicide (Ciarrochi et al., 2005). One explanation for these findings is that other risk factors better capture the contribution of IU-related distress to suicide. Indeed, AS may partially align with anxiety through its shared focus on uncertainty (Carleton et al., 2007). Further, in a sample of older adults in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, Parlapani et al. (2020) found that IU was uniquely associated with loneliness but not symptoms of depression and anxiety. One possible explanation for these findings is that IU is an important prognostic indicator of suicide risk, but that this risk occurs through the association IU shares with AS and loneliness. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether IU conveys an important, unique risk for suicide during the pandemic through other risk factors.

Given evidence that loneliness, AS, and IU are heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic; loneliness, AS, and IU are all associated with suicidal ideation; and loneliness and AS are uniquely associated with suicidal ideation, interventions targeting these risk factors may serve to reduce suicide during the pandemic and as we transition back to “normal.” Consistent with public health recommendations, targeting these risk factors through remotely delivered interventions is necessary to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Computerized interventions targeting loneliness, AS, and IU that can be remotely delivered have proven efficacious (Allan et al., 2018; Oglesby et al., 2017; Raines et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2016). Further, because the experience of these risk factors is common and is not stigmatized in the way that mental health constructs are, more people might be prone to utilize these interventions. Thus, brief interventions targeting loneliness, AS, and IU may be cost-effective and efficient means of reducing suicide risk during and after the impacts of COVID-19.

There are several limitations of the current study. First, we only tested cross-sectional models. Whereas this provides important information about associations among AS, IU, loneliness, and suicidal ideation, it does not provide information about causal associations. Longitudinal studies are needed, particularly studies that consider the complexities of cross-lagged longitudinal data analysis (Zyphur et al., 2020). Second, we measured objective social isolation using perceived length of time under stay at home orders and not with other measures such as proximity to others, stay at home orders as indicated by area code, or efforts at maintaining social interactions while maintaining physical distance. This is important because even under these orders, the level of social interaction and individual experiences is likely to vary widely. Third, the nature of the pandemic and the need to get data out as quickly as possible, have precluded the inclusion of data other than self-report, as well as longitudinal data. This is a limitation that future studies should address as the pandemic continues. Fourth, because of the low base rates of suicidal behavior as well as the need for expediency, we focused on suicidal ideation as an outcome. Again, as the pandemic unfolds and through its aftermath, we must continue to examine the complex dynamics of suicidality. We hope that other studies heed the call to continue to track clinical progress as much as possible, as this information may be critical in identifying the best possible avenues to address the treatment burden that is coming.

This study, across two samples, provides guidance at a critical juncture for resource deployment, regardless of these limitations. In the current study, models including loneliness, AS, and IU accounted for between 50 and 74% of the variance in suicidal ideation. Further, both loneliness and AS were uniquely associated with suicidal thoughts. Although IU was not significantly correlated with suicidal ideation, and there were no synergistic relations between risk factors on suicidal ideation, the fluid vulnerability model suggests that this and other risk factors could interact with a multitude of the potential stressors experienced during the pandemic to place an individual in a state of heightened suicide risk. Both short and long-term longitudinal models are needed to supplement this work and inform the role of these variables during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Highlights.

We examined the relations between suicidal desire and risk factors for suicide.

Loneliness was uniquely associated with increased suicidal ideation.

Anxiety sensitivity was uniquely associated with increased suicidal ideation.

Intolerance of uncertainty correlated with increased suicidal ideation.

Funding

This study is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RMH116311A (PI: Allan). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no conflicts of interest for any authors involved in production of this manuscript.

References

- Allan NP, Boffa JW, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2018). Intervention related reductions in perceived burdensomeness mediates incidence of suicidal thoughts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 282–288. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Capron DW, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2014). Unique relations among anxiety sensitivity factors and anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(2), 266–275. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Korte KJ, Capron DW, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2014). Factor mixture modeling of anxiety sensitivity: A three-class structure. Psychological Assessment, 26, 1184–1195. 10.1037/a0037436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Raines AM, Capron DW, Norr AM, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2014). Identification of anxiety sensitivity classes and clinical cut-scores in a sample of adult smokers: Results from a factor mixture model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(7), 696–703. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Short NA, Albanese BJ, Keough ME, & Schmidt NB (2015). Direct and Mediating Effects of an Anxiety Sensitivity Intervention on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Trauma-Exposed Individuals. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(6), 512–524. 10.1080/16506073.2015.1075227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Haigh EAP (2014). Advances in Cognitive Theory and Therapy: The Generic Cognitive Model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 1–24. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, Reiner I, Jünger C, Michal M, Wiltink J, Wild PS, Münzel T, Lackner KJ, & Tibubos AN (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 97. 10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, & Thisted RA (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. - PsycNET. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0882-7974.21.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, & Cacioppo JT (2015). Loneliness: Clinical Import and Interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. 10.1177/1745691615570616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, Oasi O, Olié E, Carvalho AF, & Courtet P (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 653–667. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron DW, Allan NP, Ialongo NS, Leen-Feldner E, & Schmidt NB (2015). The depression distress amplification model in adolescents: A longitudinal examination of anxiety sensitivity cognitive concerns, depression and suicidal ideation. Journal of Adolescence, 41, 17–24. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capron DW, Cougle JR, Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE, & Schmidt NB (2012). An interactive model of anxiety sensitivity relevant to suicide attempt history and future suicidal ideation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(2), 174–180. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Mulvogue MK, Thibodeau MA, McCabe RE, Antony MM, & Asmundson GJG (2012). Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 468–479. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Norton MAPJ, & Asmundson GJG (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 105–117. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J, Rosenzweig C, Moss AJ, Robinson J, & Litman L (2019). Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 51(5), 2022–2038. 10.3758/s13428-019-01273-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Said T, & Deane FP (2005). When simplifying life is not so bad: The link between rigidity, stressful life events, and mental health in an undergraduate population. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 33(2), 185–197. 10.1080/03069880500132540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SL, & Fan X (1997). Structural Equation Modeling: Basic Concepts and Applications in Personality Assessment Research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 68(3), 508–531. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6803_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, & Finch JF (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Zill N, Bode R, Butt Z, Kelly MAR, Pilkonis PA, Salsman JM, & Cella D (2013). Assessing social support, companionship, and distress: National Institute of Health (NIH) Toolbox Adult Social Relationship Scales. Health Psychology, 32(3), 293–301. 10.1037/a0028586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, & Muñoz M (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 172–176. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Richmond JR, Edmonds KA, Scamaldo KM, & Rose JP (2020). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness explain the associations of COVID-19 social and economic consequences to suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, n/a(n/a). 10.1111/sltb.12654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Curtin, &. Warner. (2020). Increase in Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. 362, 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. - PsycNET. /doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F1082-989X.3.4.424 [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman L, Robinson J, & Abberbock T (2017). TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 433–442. 10.3758/sl3428-016-0727-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, Sesker A, Strickhouser JE, Terracciano A, & Sutin AR (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2020-42807-001.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McClelland H, Evans JJ, Nowland R, Ferguson E, & O’Connor RC (2020). Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 880–896. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, & Barry CL (2020). Psychological Distress and Loneliness Reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA, 324(1), 93. 10.1001/jama.2020.9740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay D, Yang H, Elhai J, & Asmundson GJG (2020). Anxiety regarding contracting COVID-19 related to interoceptive anxiety sensations: The moderating role of disgust propensity and sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102233. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas Carleton R, Sharpe D, & Asmundson GJG (2007). Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty: Requisites of the fundamental fears? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(10), 2307–2316. 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oglesby ΜE, Allan NP, & Schmidt NB (2017). Randomized control trial investigating the efficacy of a computer-based intolerance of uncertainty intervention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 95, 50–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlapani E, Holeva V, Nikopoulou VA, Sereslis K, Athanasiadou M, Godosidis A, Stephanou T, & Diakogiannis I (2020). Intolerance of Uncertainty and Loneliness in Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pels F, & Kleinert J (2017). Feeling lonely in the lab: A literature review and partial examination of recent loneliness induction procedures for experiments. Psihologija, 50(2), 203–211. 10.2298/PSI160823006P [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raines AM, Allan NP, McGrew SJ, Gooch CV, Wyatt M, Laurel Franklin C, & Schmidt NB (2020). A computerized anxiety sensitivity intervention for opioid use disorders: A pilot investigation among veterans. Addictive Behaviors, 104, 106285. 10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2019.106285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger MA, Stanley IH, & Joiner TE (2020). Suicide Mortality and Coronavirus Disease 2019—A Perfect Storm? JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1093. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S (1991). Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clinical Psychology Review, 11(2), 141–153. 10.1016/0272-7358(91)90092-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, & McNally RJ (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(1), 1–8. 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD (2006). Fluid Vulnerability Theory: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding the Process of Acute and Chronic Suicide Risk. In Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy (pp. 355–368). American Psychological Association, 10.1037/11377-016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satici B, Saricali M, Satici SA, & Griffiths MD (2020). Intolerance of Uncertainty and Mental Wellbeing: Serial Mediation by Rumination and Fear of COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10.1007/s11469-020-00305-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Raines AM, Allan NP, & Zvolensky MJ (2016). Anxiety sensitivity risk reduction in smokers: A randomized control trial examining effects on panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 138–146. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L (2020). COVID-19, anxiety, sleep disturbances and suicide. Sleep Medicine, 70, 124. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BM, Twohy AJ, & Smith GS (2020). Psychological inflexibility and intolerance of uncertainty moderate the relationship between social isolation and mental health outcomes during COVID-19. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 162–174. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Boffa JW, Rogers ML, Horn MA, Albanese BJ, Chu C, Capron DW, Schmidt NB, & Joiner TE (2018). Anxiety sensitivity and suicidal ideation/suicide risk: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(11), 946–960. 10.1037/ccp0000342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, Abramowitz JS, Holaway RM, Sandin B, Stewart SH, Coles M, Eng W, Daly ES, Arrindell WA, Bouvard M, & Cardenas SJ (2007a). Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 176–188. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, Abramowitz JS, Holaway RM, Sandin B, Stewart SH, Coles M, Eng W, Daly ES, Arrindell WA, Bouvard M, & Cardenas SJ (2007b). Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment, 19, 176–188. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 197–215. 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, van der Roest H, & de Vries DH (2020). Loneliness and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study Among Dutch Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 10.1093/geronb/gbaa111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Naragon-Gainey K, Koffel E, Chmielewski M, Kotov R, Stasik SM, & Ruggero CJ (2012). Development and Validation of New Anxiety and Bipolar Symptom Scales for an Expanded Version of the IDAS (the IDAS-II). Assessment, 19(4), 399–420. 10.1177/1073191112449857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, (n.d.).WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. World Health Organization. Retrieved July 17, 2021, from https://covidl9.who.int [Google Scholar]

- Zyphur MJ, Allison PD, Tay L, Voelkle MC, Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, Hamaker EL, Shamsollahi A, Pierides DC, Koval P, & Diener E (2020). From Data to Causes I: Building A General Cross-Lagged Panel Model (GCLM). Organizational Research Methods, 23(4), 651–687. 10.1177/1094428119847278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]