Abstract

Metabolites, the biochemical products of the cellular process, can be used to measure alterations in biochemical pathways related to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the relationships between systemic abnormalities in metabolism and the pathogenesis of AD are poorly understood. In this study, we aim to identify AD-specific metabolomic changes and their potential upstream genetic and transcriptional regulators through an integrative systems biology framework for analyzing genetic, transcriptomic, metabolomic and proteomic data in AD. Metabolite co-expression network analysis of the blood metabolomic data in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) shows short-chain acylcarnitines/amino acids and medium/long-chain acylcarnitines are most associated with AD clinical outcomes including episodic memory scores and disease severity. Integration of the gene expression data in both the blood from the ADNI and the brain from the Accelerating Medicines Partnership Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) program reveals ABCA1 and CPT1A are involved in the regulation of acylcarnitines and amino acids in AD. Gene co-expresion network analysis of the AMP-AD brain RNA-seq data suggests the CPT1A and ABCA1 centered subnetworks are associated with neuronal system and immune response, respectively. Increased ABCA1 gene expression and adiponectin protein, a regulator of ABCA1, correspond to decreased short-chain acylcarnitines and amines in AD in the ADNI. In summary, our integrated analysis of large scale multi-omics data in AD systematically identifies novel metabolites and their potential regulators in AD and the findings pave a way for not only developing sensitive and specific diagnostic biomarkers for AD but also identifying novel molecular mechanisms of AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, metabolomics, genetic, acylcarnitines, amino acids, CPT1A, ABCA1, Adiponectin, risk factors, multiscale metabolite co-expression network

NARRATIVE

1.1. Contextual background

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, presently affecting more than 6 million Americans, and the number of AD patients in the US is expected to increase dramatically each year [1, 2]. In the past several decades, many studies have been carried out to investigate CSF biomarkers (Tau and Abeta) [3, 4], neuroimaging measurements of hippocampal/cortical atrophy and amyloid-beta deposition in the brain [5], mitochondrial disturbance [6] and microglial dysfunction and immune response in AD [7] to better understand metabolic alterations in the early stage of AD. Metabolites, which are the biochemical products of cellular processes, can be used as a readout for alterations in biochemical pathways related to the pathogenesis of AD. Despite significant advances in the field, the metabolic basis of AD is, however, still poorly understood, and the relationships between systemic abnormalities in metabolism and AD pathogenesis remain elusive. Similarly, we are still seeking biological processes and genetic mechanisms that might underlie metabolic involvement in AD progression.

The concentration of specific types of metabolites in blood, cells, tissues, and cerebrospinal fluid are influenced by disease pathogenesis [8, 9]. Changes in metabolites have also been linked to genetic variations [10], immune response [11], microbiome [12], and lifestyle and diet [13]. Recent studies revealed that plasma phospholipids were associated with cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD patients [14], and altered sphingomyelin and ceramide levels were observed in the early stage of AD [15]. Furthermore, while glucosylceramides, lysophosphatidylcholines, and unsaturated triacylglycerides levels are significantly associated with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Abeta level a monounsaturated sphingomyelins and ceramide levels are positively correlated with CSF total tau and brain atrophy [16, 17]. Acylcarnitines and several amines have been associated with brain volume changes and cognitive impairment in symptomatic stages of AD, while a specific set of sphingomyelins and phosphatidylcholines have been associated with CSF amyloid-beta level in preclinical AD stages [18]. A more recent study revealed that 26 metabolites, including sphingolipids, were highly correlated with hippocampal atrophy, AD-pathology related biomarkers as well as memory scores in the brain and blood in preclinical AD [19].

This study aims to address two critical questions in the metabolomic analysis of AD: (1) “Are metabolite co-expression networks and upstream genetic regulators predictive of disease progression and survival?”, (2) “What are the genetic mechanism and upstream regulators of the changes in acylcarnitines and amino acids during AD progression?”. We hypothesized specific metabolites are significantly associated with AD-related clinical outcomes, and key genetic drivers play a significant role in regulating metabolites in AD. Towards this end, we systematically interrogated metabolomic, genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical data from the matched subjects in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the metabolomics data generated by the Alzheimer Disease Metabolomics Consortium to identify 1) specific metabolites highly associated with AD pathology and cognitive phenotypes, 2) key biological processes underlying changes in metabolites in blood.

1.2. Study Conclusions, Future Directions and Limitations

Our results indicate that the balance between essential amino acids/BCAAs and short-chain acylcarnitine homeostasis is disturbed in AD, with medium/long-chain acylcarnitines levels being also significantly different in AD versus control but in the opposite direction. We identified two important genes (ABCA1 and CPT1A) and two proteins (Adiponectin and NGAL) involved in the regulation of acylcarnitines and amines. Increased ABCA1 gene expression and adiponectin protein (a regulator of ABCA1) corresponded to decreased short-chain acylcarnitines and amines in AD. In addition, CPT1A and ABCA1 genes were differently expressed in the brains of AD patients compared to controls, and their subnetworks were enriched for AD, aging, and neuronal system-related gene signatures/pathways. The proposed framework opens up a new avenue for identifying not only dysregulated acylcarnitine and amine metabolisms in AD, but also genetic mechanisms and biological processes underlying these metabolic changes. We acknowledge that our proposed acylcarnitines/amines hypothesis and the more generic disease-related metabolic perturbation hypothesis derived from integrative analysis of genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data are based on a correlation analysis of observed variables. But the advanced network biology approach utilized here has the potential to identify key genes and cellular/molecular pathways that may drive disease-associated perturbations in acylcarnitines, amino acids, and other metabolites. As an example, based on observations for our large-scale integrative analyses, we posit that low levels of the short-chain acylcarnitines/amines and high levels of medium/long-chain acylcarnitines could be highly predictive diagnostic biomarkers for an early stage of AD. Moving forward, we anticipate that machine learning techniques such as random forest and support vector machine (SVM) can be employed to predict disease progression (especially progression towards early AD) using these metabolites [19–21].

However, existing metabolomic and other Omics data represent only a snapshot in time of molecular states of particular patient subpopulations; therefore, network models based on such data should be considered as the initial phase of fully-fledged models, which will be developed from matched, longitudinal multi-Omics data from relatively large patient populations using more advanced network biology approaches such as causal network inference. To further infer causal relationships among a large collection of dissimilar variables at different -omics layers, we can conduct Bayesian probabilistic causal network (BN) analysis [22–25] as we and others have previously done in AD [26–28] and other complex traits [29, 30]. Moreover, the static state BN analysis can be expanded to model dynamic and time-dependent regulation changes in a longitudinal or time-series dataset. For example, a dynamic BN (DBN) framework had been employed to model the dynamic causal network of blood gene expression in response to food intake over multiple time points, where intra-time-slice BN structure from a large data set generated at static states was combined with inter-time-slice structure inferred from the time series data [31]. The data-driven causal networks will provide a systems-wide context for understanding the mechanisms of known regulators and discovering novel key causal regulators among mRNA, protein, and metabolite levels. As transcription regulates the abundance of metabolites [32, 33], metabolites also transfer the information back to the transcription network directly or indirectly interacting with a transcription factor [34–36].

There are several limitations in our study. First, even though ADNI is one of the best and largest cohorts with matched multi-omics and metabolomics data in AD, we have only a moderate number of metabolites, and we still do not have longitudinal metabolite data to monitor metabolite changes during the course of each individual’s disease progression. The other significant limitation is that the transcriptomic and metabolomic data were from the blood. The metabolites in the blood are circulating metabolites and gene expression represents blood cell transcriptomics, and thus, they represent substantially differrent compartments of the body. Such difference limits the findings from our analysis. Another limitation of this study is the lack of an independent cohort to replicate our key findings. Further studies are also needed to validate ABCA1 and CPT1A as potential upstream regulators of acylcarnitines in AD.

One of the major challenges in identifying AD-specific metabolites is that neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have comorbidity. Interestingly, some altered metabolic signatures are common in AD, PD, and ALS [37, 38]. ABC transporters carrying multiple substances through the blood-brain barrier are expressed in all cell types in the brain and are significantly associated with several neurodegenerative diseases [38–40]. Medium/long-chain acylcarnitines, phosphatidylcholine, and lysophosphatidylcholine levels increase in the urine of PD patients [41–43] while plasma levels of acylcarnitine, phosphatidylcholine (PC), and sphingomyelin in AD and MCI patients decreased when compared with healthy individuals [44].

2. CONSOLIDATED RESULTS AND STUDY DESIGN

In this study, we systematically interrogated metabolomic, genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical data from the matched subjects in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) to identify key drivers and metabolic pathways associated with changes in metabolites with disease severity. We show acylcarnitines and amines are highly correlated with AD clinical outcomes and further reveal key biological drivers and pathways that are involved in metabolomic changes in MCI and AD. One hundred forty metabolites in fasting serum samples from the ADNI (362 controls, 94 with significant memory concerns, 764 with mild cognitive impairment, and 298 with AD), were analyzed using the AbsoluteIDQ-p180 kit. The data were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), education, cohort, and medication. A metabolite co-expression network was constructed using Multiscale Embedded Gene co-Expression Network Analysis (MEGENA). Co-expressed metabolite modules were then prioritized by the strength of association with clinical/cognitive and pathological traits. Correlation analysis of the co-expressed metabolite modules and the matched gene/protein expression data was performed. The ROS/MAP cohort was used as a replication study of the co-expression network. Six brain transcriptomic datasets from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank, ROS/MAP, and Mayo clinic cohorts were utilized to build up gene-centered correlation networks to elucidate functions of upstream regulators of candidate metabolites. Modules comprised of short-chain acylcarnitines/amino acids, and medium/long-chain acylcarnitines were most associated with worse AD clinical outcomes, including episodic memory scores and disease severity. Short-chain acylcarnitines (especially C3), BCAAs (isoleucine and valine) and other amino acids (tryptophan and tyrosine), as well as medium/long-chain acylcarnitines (C12, C14:1/C14:2, C16:1 and C18), are significantly correlated with AD severity and cognitive traits. CPT1A gene expression was highly correlated with an increased level of the medium/long-chain acylcarnitines. Increased ABCA1 gene expression and adiponectin (a regulator of ABCA1) protein expression corresponded to decreased short-chain acylcarnitines and amines in AD. In addition, CPT1A and ABCA1 were differently expressed in the brains of AD patients compared to controls, and their subnetworks were enriched for AD, aging, and neuronal system-related gene signatures/pathways. The integration of genetic and transcriptomic data with metabolomic networks, highlights novel pathways and driver molecules that potentially contribute to disease pathogenesis. For example, the interaction between the acylcarnitines and amino acids with proteins such as Adiponectin and NGAL indicates a novel framework of cellular mechanism. In addition, we developed the trajectory inference analysis and Granger causality test on bulk tissue metabolomic data in ADNI using Slingshot [45] to identify metabolite changes along the pseudo time. Preliminary data shows that the expression level of the module of short-chain acylcarnitines and amines decreases over time while that of the module of medium/long-chain acylcarnitines increases over time. Our multiscale metabolite co-expression network of ROS/MAP brain data also revealed that the modules of amines and short-chain acylcarnitine are significantly correlated with neuritic plaque burden in midfrontal cortex, and significantly overlap with the top modules in ADNI. The key strength of our findings in terms of the modeling is that the identification of the biological drivers/pathways highly correlated with the co-expressed metabolites in AD can be used as predictors during disease progression and survival. Integrated analysis of genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data pave the way for the development of sensitive and specific diagnostic biomarkers either alone or in combination in the early stage of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Our findings clearly indicate that (1) BCAAs and Acylcarnitines are increasingly utilized in AD progression and (2) fatty acid β-oxidation is dysregulated and/or mitochondria are in dysfunction in AD, (3) Acylcarnitines can be predictive of AD phenotype conversion from MCI compared with MCI stable phenotype. Therefore, the results from our correlative study are consistent with the connection between mitochondrial dysfunction and AD pathogenesis but provide more insights into the underlying mechanisms for diabetes as a risk factor for AD. Since previous studies showed increased utilization of branched amino acids is associated with type 2 diabetes and mitochondrial dysfunction is common in diabetes [46, 47], the association of branched-chain amino acids with AD revealed by this study opposite to this notion. Besides the opposite connection between obesity and Type 2 diabetes, elevated medium/long-chain acylcarnitines in plasma are associated with the disruption of β-oxidation in depression [48, 49].

3. DETAILED METHODS AND RESULTS

3.1. Methods

Study Participants

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)

Metabolites in fasting serum samples were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Phase 1 (ADNI-1) and its subsequent extensions (ADNI-GO/2) for this study (adni.loni.usc.edu). ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD., and participants were recruited from more than 50 sites across the United States and Canada. The ADNI dataset includes serial MRI and PET scans, longitudinal CSF markers, neuropsychological test scores, and clinical assessments. ADNI cohort includes cognitively normal older individuals (CN), significant memory concerns (SMC), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD aged 55–90 (http://www.adni-info.org/). The ADNI dataset includes structural MRI and PET scans, longitudinal CSF markers, and performance on neuropsychological and clinical assessments. Also, ADNI samples have APOE and genome-wide genotyping data, transcriptomics, and whole-genome sequencing data.

Quantitative metabolomics was performed by Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium (https://sites.duke.edu/adnimetab/) using ADNI samples and the Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p180 (Biocrates Life Sciences AG, Innsbruck, Austria) platform. Quantification of serum metabolites including amino acids, acylcarnitines, sphingomyelins (SMs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), hexoses (h1s), and biogenic amines was done using methods published previously [18, 50, 51]. Flow injection analysis-tandem mass spectrometry (FIA-MS/MS) was used to analyze the acylcarnitines, lipids, and h1s Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) using an AB SCIEX 4000 QTrap mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Darmstadt, Germany) with electrospray ionization was used to analyze the amino acids and biogenic amines. The concentration of each metabolite was measured in μM [18]. Blood metabolites were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), education, cohort, and medication information.

We analyzed metabolic profiles from 1,518 individuals, including 362 CN older individuals, 94 individuals with SMC, 270 individuals diagnosed with EMCI, 494 individuals with LMCI, and 298 individuals diagnosed with AD. Supplemental Table S1 includes demographic and clinical characteristics of the ADNI participants.

The Religious Orders Study (ROS) and Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP)

Description of ROSMAP has been previously reported [52]. Metabolomics data from brain ROS/MAP Dataset was used as a replication dataset to test whether metabolite modules are conserved between the blood and the brain (Synapse:syn10235596). Data were obtained with the same Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p180 kit used in the ADNI study. Brain metabolites (N=163) were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and education. We identified co-expressed metabolite modules from 50 individuals with no cognitive impairment (NCI), 30 individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 25 individuals diagnosed with AD. Fisher’s exact test (FET) was utilized to test if the co-expressed modules in the blood significantly overlap those from the brain.

Construction of multiscale metabolite co-expression network

We constructed a multiscale metabolite co-expression network (MMCEN) using the quality-controlled and normalized metabolomic data from the blood samples collected from the ADNI participants (N=1,518). The Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p180 platform, which measures amino acids, acylcarnitines, sphingomyelins (SMs), phosphatidylcholines (PCs), hexoses (h1s), and biogenic amines, was used to generate the metabolite data [53]. In total, 140 metabolites were used in the metabolite network analysis. The metabolite expression data from 1,518 individuals were adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), education, and cohort (ADNI1 and ADNIGO/2).

A metabolite co-expression network for the ADNI blood expression data was constructed using Multiscale Embedded Gene co-Expression Network Analysis (MEGENA) [54]. MEGENA first constructed a Planar Filtered Network (PFN) from significantly correlated metabolite pairs of the resulted PFN then went through a multiscale clustering analysis to identify co-expressed modules using different scales of compactness of modular structures controlled by a resolution parameter. The metabolite modules were then compared with random PFN modules generated by shuffling the link weights of the parent cluster to calculate the statistical significance of each module. A multiscale hub analysis was then performed to identify highly connected hub nodes (metabolites) for each significant module. The modules with less than 10 metabolites were excluded from further downstream analyses. Finally, principal component (PC) analysis was performed on each module to obtain the principal component vectors (eigen-metabolites) for subsequent correlation analysis of modules and various cognitive, clinical and neuropathological traits.

Cognitive and neuropathological traits

AD-pathology related traits including Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), cerebrospinal fluid tau, phospho-tau (p-tau) and amyloid-beta levels, Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F) (FDG)-PET, Florbetapir (AV-45) PET, clinical and cognitive performance data, were downloaded from the ADNI1 and ADNIGO/2 database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). CSF measurements and quality control data were obtained from the LONI website as “UPENN CSF Biomarkers Elecsys.” The complete descriptions of the collection and process protocols can be found at www.adni-info.org. Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-Cog), Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE), Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores and self (PT)- and informant (SP)- everyday cognition (ECog) memory scores which include language, visuospatial, organization of items and divided attention were downloaded as representations of cognitive test scores [55–57]. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) score, the assessment of episodic memory, consists of 5 learning trials of 15 words, immediate recall, and 30-minute delayed recall, as well as an interference list and recognition test. MMSE and MOCA measures memory, recall, and attention [58]. The other important memory score is ADAS-Cog, which is similar to RAVLT and measures the episodic memory using ten unrelated words. For all score types, those scores determined baseline was chosen for our analyses. Since not all participants in ADNI have cognitive, clinical, and pathology recorded scores, Supplemental Table S2 summarizes how many participants were included for each correlation-based analysis.

Correlation analysis of the metabolite modules and neuropathological traits

To determine the predictive power of the co-expressed metabolite modules of the MMCEN, we evaluated correlations of the metabolite modules with clinical/cognitive CSF (tau and A) and imaging (FDG and AV45 PET) biomarker variables. We ranked order co-expressed metabolite modules based on the overall strength of such correlations. Since each module includes at least ten metabolites, we reduced the dimensionality of the data by computing the first principal component (PC) from the metabolites in each module and then computed Spearman’s correlation coefficient between each clinical/cognitive/CSF trait (i) and the first PC of each metabolite module (j). P-value () of the correlation coefficient was computed via the asymptotic t approximation. Significant correlations were defined as those with multiple testing adjusted P value less than 0.05 (adjusted by the i*j number of correlations).

The aforementioned correlations between a metabolite module (j) and clinical/cognitive/pathological traits were then combined into a composite importance score by , where n denotes the total number of traits. The importance score essentially computes the mean of the absolute value of the correlation coefficients across traits for each metabolite module. We have previously used this type of composite score to rank order the importance of key driver genes identified in gene networks across multiple brain regions [26]. The metabolite modules were then ranked by their composite importance scores. All available clinical/cognitive/AD-pathological traits were used for the correlation analysis.

Identification of genes correlated with metabolite co-expression network

Microarray-based RNA gene expression data from blood samples of 745 ADNI participants was downloaded from the ADNI LONI website (http://adni.loni.usc.edu) [59]. We only included the individuals with both metabolomic and transcriptomic data (N=417; CN=121, EMCI=183, LMCI=76, AD=37). Probe sets of the Affymetrix Human Genome U219 platform (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were excluded from the data if they did not match any gene or matched multiple genes. All gene expression data were adjusted for RIN, batch effect, and sex. For each gene with multiple probes, the probe with the most variation across all the samples was selected as the representative of the gene. In total, 17,848 genes were included in the correlation analysis of the gene expression data and the metabolite modules using both Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses. Significance levels were adjusted by multiple testing. Adjusted p <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analyses carried out in this study.

Construction of CPT1A and ABCA1 centered co-expression gene network in AD

Six RNA-seq datasets from six different brain regions in three human postmortem brain cohorts, including the Mount Sinai Brain Bank AD cohort (MSBB) (4 cortical regions) [60], the Religious Order Study (ROS) and the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) (ROSMAP) cohort (the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)) [61, 62] and the Mayo Clinic cohort (the temporal cortex (TCX)) [63] were used for constructing CPT1A and ABCA1 centered co-expression gene networks.

The MSBB AD cohort contained brain specimens obtained from the Mount Sinai/JJ Peters VA Medical Center Brain Bank, which holds over 1,700 samples. This cohort was assembled after applying stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria and represents the full spectrum of disease severity ranging from cognitively normal to severe dementia. RNA-sequencing gene expression profiles were generated across four cortex brain regions (the frontal pole, the superior temporal gyrus, the parahippocampal gyrus, the inferior temporal gyrus) from about 360 brains [60]. Besides, microarray gene expression data were also generated from a smaller set of brains for 19 different cortical regions, including the hippocampus of 55 brains, which was used here [64]. The ROSMAP dataset included two prospective cohort studies of aging as the Religious Order Study (ROS) and the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) [52, 65]. About 60% of the subjects had a pathologic diagnosis of AD at autopsy. ROSMAP has postmortem RNA-sequencing data generated from the DLPFC of over 600 brains [65]. The preprocessed expression data for the MSBB AD RNA-seq and ROSMAP RNA-seq cohorts were downloaded from the AMP-AD knowledge portal at Synapse [66]. The Mayo RNAseq Study includes whole transcriptome data for 274 temporal cortex (TCX) samples from North American Caucasian subjects with a neuropathological diagnosis of AD, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), pathologic aging (PA) or elderly controls (CON) without neurodegenerative diseases. For each dataset, we calculated correlation coefficients between each candidate gene (CPT1A or ABCA1) and the rest genes. We only focused on the genes present in all the six gene expression datasets. Finally, the genes showing significant correlations with CPT1A and ABCA1 (FDR-corrected p values ≤ 0.05) in all the six datasets with consistent correlation direction were used to define the CPT1A-centered and ABCA1-centered correlation networks, respectively.

Identification of proteins correlated with metabolite co-expression network

The proteomic data of 146 proteins in the RBM Human DiscoveryMAP panel from 566 participants at the baseline visit from the ADNI-1 dataset were downloaded from the ADNI official website (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). Sample selection criteria and quality control steps were explained previously [67]. The data were adjusted for age and sex. Four hundred ninety-eight (498) individuals (CN=51, MCI=343, and AD=104) with both blood metabolomic and proteomic data were used for this analysis. In the module-protein correlation analysis, the first PC of each metabolite module was used for computing correlation with each protein. Both the Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses were performed, and significance levels were corrected for multiple testing. An adjusted p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Mendelian Randomization Analysis

Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) [68, 69] and Heterogeneity In Dependent Instruments (HEIDI) tests were conducted to explore likely causal paths that link gene expression to metabolite concentrations. We integrated summary statistics from our metabolites GWAS and GTEx v7 eQTL summary data [70], GTEx-brain eQTL summary data [71], Cardiogenics study [72, 73], eQTLGen Consortium [74] and eQTL ADNI blood.

Input/output of each experimental steps and study workflow can be found in Supplementary Figure S1.

Major Computational Tools Analyzing and Integrating Metabolomics and Other Types of Omics Data

This study utilized several major computational tools, including data preprocessing and imputation, Mendelian Randomization, and metabolite co-expression network analysis. The metabolomics data was preprocessed to limit the potential for false-positive findings. To this end, missing values were imputed using minimum value imputation (half of the plate-specific limit of detection), single measurement outliers were winsorized to 3 standard deviations from the global mean, and multi-variate sample outliers were removed using Mahalanobis distance. The imputation had no significant influence on metabolite associations with AD biomarker profiles [75]. We used SMR [76] for Mendelian Randomization to investigate pleiotropic relationships between the expression level of a gene and disease risk. This method effectively tests whether the effect size of an SNP on a phenotype is mediated by gene expression and uses a heterogeneity test (HEIDI test) to distinguish pleiotropy from the linkage. However, it is important to note that statistical analyses such as HEIDI or COLOC [77] are not capable of providing perfect separation of pleiotropy and linkage [68], are dependent on the tissue-specific effect of eQTLs, and to date predominantly utilize cis-eQTLs and exclude trans-eQTLs. The proposed metabolite co-expression network analysis aims to systematically identify co-expression and co-regulation relationships among metabolites. The high complexity of co-expression and co-regulation structures requires effective analytic algorithms to uncover the natural network organization of metabolite-metabolite interaction, such as modularity and hierarchy among the modules. MEGENA can identify biologically more meaningful and relevant co-expressed metabolite clusters than previously established network clustering methods such as eigenvector spectral clustering and WGCNA [54]. However, some true correlations may be missed in an MEGENA derived network due to the application of a planarity constraint. In addition, the co-expression network analysis doesn’t explicitly define causal relationships though hub nodes are more likely to be key regulators.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. A multiscale metabolite co-expression network (MMCEN) revealed that Acylcarnitines and Amines are highly associated with AD worse outcomes in blood

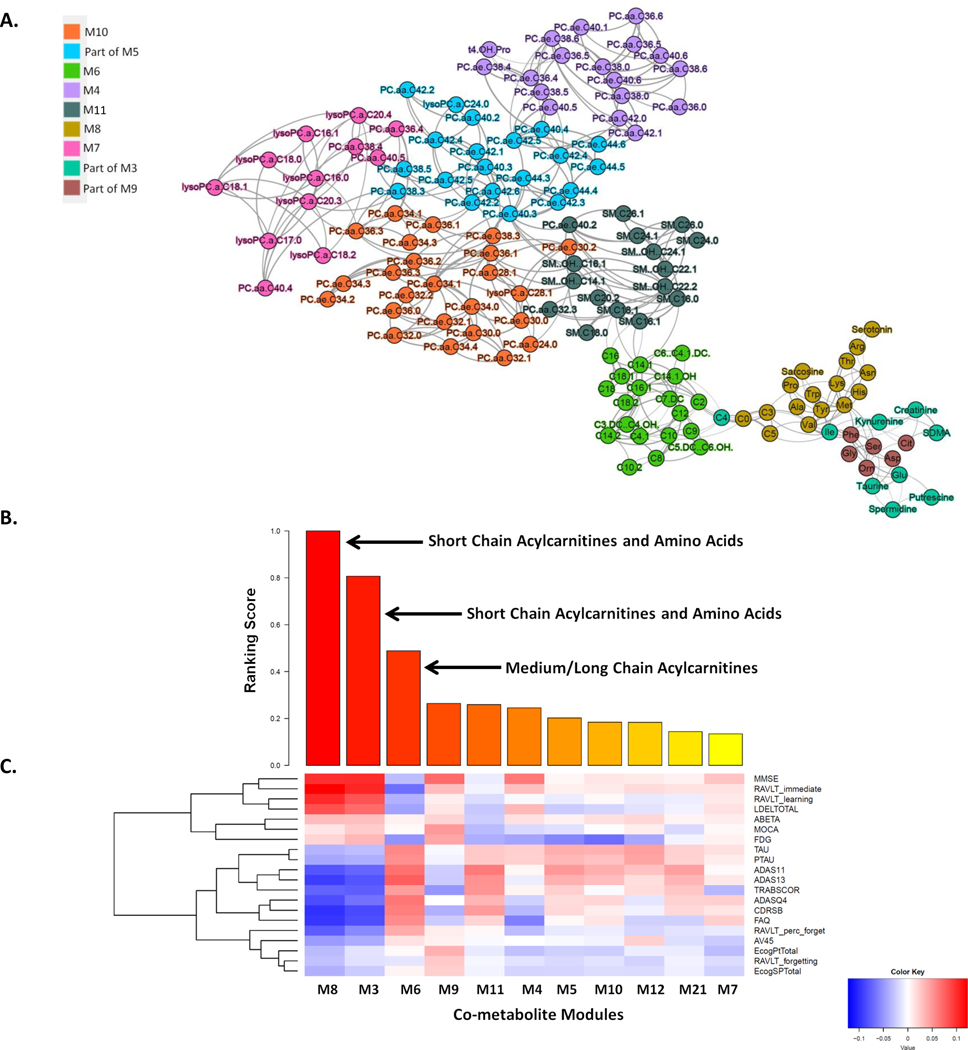

By combining two ADNI cohorts (ADNI1 and ADNIGO/2) (Supplemental Table S1) in this study provides further evidence that short-chain acylcarnitines (especially C3), BCAAs (isoleucine and valine) and other amino acids (tryptophan and tyrosine), as well as medium/long-chain acylcarnitines (C12, C14:1/C14:2, C16:1 and C18), are significantly correlated with AD severity and cognitive traits (Supplemental Table S2). First, we identified co-expressed metabolites as modules through the multiscale embedded gene co-expression network analysis (MEGENA) [54] of the metabolomic data in the ADNI, and eleven co-expressed metabolite modules were identified (Figure 1A; Supplementary Table S3). Note that the metabolomic data were corrected for age and other covariates (Methods) and thus the results from the subsequent analyses of the data are independent of age. Multiscale in MEGENA means multiple levels of clustering compactness used for identifying clusters or modules with a hierarchical structure. Metabolite modules are then characterized and prioritized by association with AD through correlation analysis of the first principle component of each metabolite module and various clinical/cognitive/AD-pathology traits (Figure 1B–C). The top-ranked metabolite modules include short-chain acylcarnitines (C0, C3, and C5) and amino acids (histidine, lysine, tryptophan, asparagine, isoleucine, tyrosine, alanine, arginine, proline, valine, tyrosine, sarcosine, serotonin sarcosine, serotonin) as well as medium/long-chain acylcarnitines (C5.DC..C6.OH., C6..C4.1.DC., C7.DC, C8, C9, C10, C10.2, C12, C14.1, C14.1.OH, C16, C16.1, C18, C18.1) (Supplementary Table S4). To better understand which metabolites significantly changed during disease progression (CN → SMC → EMCI → LMCI →AD), univariate analysis of variance was performed on individual metabolites using SPSS 23.0. Propionylcarnitine (C3), valerylcarnitine (C5), histidine (His), lysine (Lys), tryptophan (Trp), valine (Val), sarcosine in the top module M8 showed the most significant decrease during the course of disease progression, which was also confirmed by the down-regulation in the MCI and AD groups (p-value < 0.05). On the contrary, five important medium/long-chain acylcarnitines as C12, C14.1, C14.2, C16.1, and C18 in the module M6 significantly increased in the blood during the course of disease progression (C12: Dodecanoylcarnitine; C14.1: Tetradecenoylcarnitine; C14.2: Tetradecenoylcarnitine; C16.1: Hexadecenoylcarnitine; C18.1: Octadecenoylcarnitine). Interestingly, the C18 level significantly increased in the LMCI group compared with CN.

Figure 1. Multiscale metabolite co-expression network analysis of the blood metabolomic data in the ADNI.

(A) The global metabolite co-expression network. Two parent modules M3 and M5 are not shown here. (B) Rank-ordered metabolite modules by the extent of association to the clinical outcomes. (C) Heatmap of the correlations between clinical/cognitive AD-pathology related traits and metabolite modules. Cognitive and pathological traits are shown on the right axis while the metabolite modules are shown at the bottom axis. The intensity of the color in each cell indicates the magnitude of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the corresponding row and column variables, for those correlations with adjusted p values <0.05. Red and blue colors indicate positive and negative correlations, respectively.

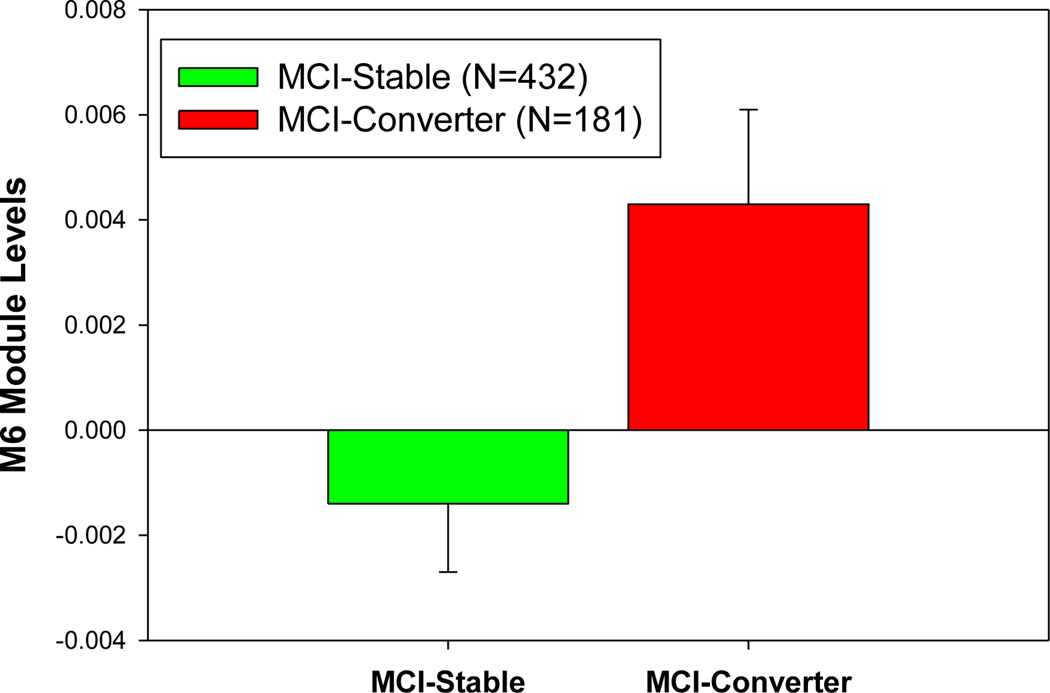

In addition, we compared the module and metabolite expression levels in the MCI-to-AD converters with those in the MCI non-converters. The module M6 includes medium/long-chain acylcarnitines, which significantly increased in the MCI-to-AD converters compared with MCI stable individuals over two years (p=0.016) (Figure 2), suggesting medium/long chain acylcarnitines as risk factors for AD. We also developed a multiple logistic regression model to predict MCI to AD pheno-conversion status (0=non-converter, 1=converter) using multiple predictors including network modules, metabolites, clinical traits, and imaging features based on the ADNI cohort. To validate our model, we used 10-fold cross-validation on the 368 participants (converters=104, non-converters=264) with all the predictors available and determined the mean precision, recall, and accuracy across all the runs. Prediction yielded a continuous value from 0 to 1, converted to a binary prediction of conversion status using a cutoff value of 0.35. Our logistic model used the following variables to predict MCI conversion status: M6, M10, M11, M12, M21, education, ADAS13 (baseline), MMSE (baseline), RAVLT (baseline), Hippocampal volume (baseline), C3, C18, C14.1, and C14.2. We achieved an average accuracy of 76.88% (std=7.53%) in 10-fold cross-validation. To predict continuous hippocampal and whole brain volumes at two years (24 months) post-baseline measurement, we developed a generalized linear model using the same predictors for MCI conversion status and intracranial volume (ICV) at baseline as an additional covariate. Model accuracy from 10-fold cross-validation was determined by assessing the Pearson correlation between predicted and observed hippocampal and whole brain volumes for all participants. We achieved a Pearson correlation R2 of 0.938 (p-value= 2.15 × 10−223) for the hippocampal volume and 0.694 (p-value=4.46 × 10−96) for the whole brain volume at 24 months.

Figure 2.

The expression level of the module M6 (i.e., module eigen-metabolite represented by the first PC of the module) significantly increases in the subjects with conversion from MCI to AD (termed MCI converters) compared with those MCI subjects without conversion (termed MCI stable group) in two years.

3.2.2. Acylcarnitines and Amines are significantly associated with AD-pathology in brain

To examine the concordance between blood and brain metabolites in AD, we constructed the multiscale embedded gene co-expression network analysis using The ROSMAP brain metabolite data (CN=50, MCI=30, and AD=25) and then rank-ordered metabolite modules by the strength of correlation with AD endophenotypes such as memory scores and neurotic plaque burden. The top three modules (M10, M3, and M17) (Supplementary Table S5) contain short-chain acylcarnitines and Amines, and are significantly correlated with neuritic plaque burden in midfrontal cortex (FDR corrected p-value = 0.03) (Supplementary Table S6). Interestingly, the top metabolite module in the blood metabolite network significantly overlaps the top one in the brain metabolite network, and both modules contain short-chain acylcarnitines and Amines (representation factor: 3.7 p < 2.8×10−6). Therefore, the analysis shows that the metabolomic changes in the blood and the brain could be early biomarkers of AD.

3.2.3. Co-Expression Metabolite Transcriptome Network Analysis establishes a link between metabolites and a blood transcriptional network associated with AD

We then integrated the metabolomic and transcriptomic data from the blood of ADNI participants at the baseline visit to identify potential genes associated with the eleven metabolite modules. Based on the data from the participants with both transcriptomic and metabolomic data (CN=121, MCI=259, AD=37), we identified ten genes highly correlated with the top three modules containing short-chain acylcarnitines and amino acids (M8 and M3) as well as medium/long-chain acylcarnitines (M6) (Table 1). After our novel finding in the blood data, we further examined the expression levels of those eight genes in the brains of the subjects with or without AD using the MSBB (4 cortex regions) [60] and Mayo Clinic (DOI:10.7303/syn5550404) cohorts. Two of the eight genes (CPT1A and ABCA1) are differentially expressed between AD and control in the parahippocampus gyrus (PHG) from the MSBB AD cohort and the temporal cortex (TCX) from the Mayo Clinic cohort with FDR corrected p-values = 3.06×10−4 and 1.35×10−4, respectively (Table 2). Our correlation analysis shows that CPT1A is significantly associated with a medium/long-chain acylcarnitine enriched module. C12, C14.1, C14.2, C16, and C18 acylcarnitines levels increase in MCI and AD group compared with cognitively healthy individuals. In addition, CPT1A is differentially expressed in the PHG and the TCX of the AD subjects compared with the normal control. CPT1A-dependent regulation of acylcarnitines transfer may control the levels of C12, C14.1, C14.2, and C16 as well as C18 in the plasma during disease progression. As the accumulation of medium/long-chain fatty acylcarnitines is associated with AD development and progression, fatty acid transport into mitochondria becomes critical. Since fatty acid transport through CPT1A is the limiting step of this transport process, the connection of CPT1A gene/protein expression with AD becomes obvious. This finding suggests that CPT1A may serve as a drug target for the accumulation of fatty acylcarnitines and thus for AD.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation analysis of the top three modules (including acylcarnitines and amino acids) and the blood gene expression data in ADNI. The module M6 includes medium/long-chain acylcarnitines while the modules M8 and M3 include short-chain acylcarnitines and amino acids, respectively.

| Gene Expression (N=17849) | Top Metabolite Modules | Rho value | p-value | p.adj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT1A (Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1A ) |

M6 | 0.317 | 3.50×10−11 | 1.87×10−6 |

| SLC25A20 (Carnitine/Acylcarnitine Translocase) |

M6 | 0.261 | 6.60×10−8 | 1.8×10−3 |

| ABCA1 (ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 1) |

M8 | −0.236 | 1.10×10−6 | 0.02 |

| MRPL47 | M3 | 0.233 | 1.50×10−6 | 0.02 |

| ABCA1 | M3 | −0.23 | 2.10×10−6 | 0.02 |

| ABCG1 | M3 | −0.222 | 4.90×10−6 | 0.038 |

| PDK4 | M6 | 0.222 | 4.60×10−6 | 0.038 |

| UCHL3 | M3 | 0.22 | 5.80×10−6 | 0.039 |

| CCT2 | M3 | 0.215 | 9.10×10−6 | 0.049 |

| ABCG1 | M8 | −0.216 | 8.80×10−6 | 0.049 |

Table 2.

Differentially expressed genes in the human brain from the MSBB cohort. logFC= fold change; Padj = FDR adjusted p-value; AD = Alzheimer’s Disease; CN = Cognitively Normal.

| Gene | logFC | p-value | Padj | Contrast | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT1A | 0.27 | 9.09×10−6 | 1.61×10−4 | AD vs CN | PHG |

| ABCA1 | 0.41 | 2.56×10−6 | 7.53×10−5 | AD vs CN | PHG |

| CPT1A | 0.39 | 1.15×10−5 | 3.06×10−4 | AD vs CN | TCX |

| ABCA1 | 0.56 | 3×10−6 | 1.35×10−4 | AD vs CN | TCX |

Carnitine is essential for the transport of the long-chain acyl-CoAs into mitochondria, which are converted to acylcarnitines by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) [78, 79]. There are three forms of CPT enzyme including CPT1A, CPT1B, and CPT1C [80]. CPT1 activity has been implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases as a relationship with the alteration of insulin equilibrium in the brain [81]. The regulation of CPT1 affects the limited levels of long-chain acylcarnitines as C16-, C18-, and C18:1-CN levels that lead to the increase of free-CN:C16-CN in the plasma [82]. Increased plasma levels of C14:1-CN and C16-OH–CN have bene identified as a product of very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, respectively during β-oxidation in obesity and Type 2 diabetes [82]. Similarly, we identified CPT1A is significantly associated with a module comprised of medium/long-chain acylcarnitines. C12, C14.1, C14.2, C16, and C18 acylcarnitine levels increase in MCI and AD group compared with cognitively healthy individuals. Furthermore, CPT1A was differentially expressed in the hippocampus and the temporal cortex of the AD subjects compared with the normal control. We may conclude that CPT1A-dependent regulation of acylcarnitine transfer may control the levels of C12, C14.1, C14.2, and C16 as well as C18 in the plasma during disease progression. Acylcarnitine levels with mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation significantly increases in patients with major depression because of the metabolic dysfunction [49], and the association of medium/long-chain acylcarnitines with AD revealed by this study shows the same of this notion. Anti-depressants that decrease acylcarnitine levels in major depression patients might be considered for a potential treatment for AD patients.

We also show that ABCA1 gene expression is negatively correlated with the module M8 comprised of short-chain acylcarnitines and amino acids. While the levels of the metabolites in M8 significantly decrease in AD, ABCA1 expression in the blood increases in the AD group compared with the other groups. ABCA1 belongs to the superfamily of ATP-binding cassette proteins and plays a vital role in stimulating the efflux of cellular cholesterol from macrophages to Apolipoprotein A-1 (ApoA-1) and HDL, respectively [83–86]. It has been shown that the ABCA1 gene expression increased in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in AD compared with healthy control [87]. ABCA1, which is highly expressed in the brain, plays an essential role in the lipidation of AD risk gene Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) and enables clearance of amyloid-beta accumulation [88, 89]. Our ABCA1 centered consensus co-expression network demonstrates a strong interaction between ABCA1 and APOE in the brain. Since the module M7 consisting of glycerophospholipids (mostly Lysophosphatidylcholines) is highly correlated with the reduction of the short-chain acylcarnitine and amino acid modules (M8 and M3) and ABCA1 level, our finding may suggest that ABCA1 blood expression level increases as a compensation to the reduction of the glycerophospholipids.

In addition to our finding of the increased level of long-chain acylcarnitines in MCI and AD, we detected a significant decrease in the metabolite module containing C3 and amino acids in the MCI and AD groups. Acylcarnitines are produced explicitly in mitochondria using different substrates. Acylcarnitines containing eight or more carbon atoms are generated from the fatty acid β-oxidation; short-chain acylcarnitines (i.e., C3 to C6) are yielded from further β-oxidation as well as oxidation of amino acids; and C2 acylcarnitine is from all the energy substrates including fatty acids, amino acids, and glucose. Among short-chain acylcarnitines, odd-numbered acylcarnitines (i.e., C3 and C5) are specifically generated from BCAAs, suggesting BCAA/short-chain acylcarnitines are linked biochemically and functionally [82, 90]. Decreased levels of C3 in MCI compared with healthy individuals [91] and a distinguished level of C3 metabolite identified in the inferior temporal gyrus in the AD brain were reported previously [19]. We show that ABCA1 gene expression is negatively correlated with the short-chain acylcarnitine and amino acid module (M8) and differentially expressed in AD versus CN. We further reveal that the Adiponectin level, which controls ABCA1 expression through liver X receptor alpha (LXRα) in macrophages in the liver [92], is highly correlated with the short-chain acylcarnitines and branched-chain amino acids. Since RXRA mRNA level is highly correlated with that of ABCA1 in the brain, changes in the mRNA level of RXR/LXR (transcription factors) might upregulate ABCA1 in AD. ABCA1 overexpressed AD mice might be used to validate this hypothesis.

Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) and Heterogeneity In Dependent Instruments (HEIDI) tests were conducted [68, 69] to explore likely causal paths that link ABCA1/CPT1A gene expression to metabolite (C3, C5, His, Lys, Trp, Val, Sarcosine, C12; C14.1; C14.2; C16.1; C18.1) concentrations. To accomplish this, we integrated summary statistics from our metabolites GWAS and GTEx v7 eQTL summary data [70], GTEx-brain eQTL summary data [71], Cardiogenics study [72, 73], eQTLGen Consortium [74] and eQTL ADNI blood. cis-eQTLs were significantly associated with ABCA1 and CPT1A expression in human monocytes and macrophages in Cardiogenics study (NSNP_ABCA1= 19, NSNP_CPT1A = 1991), human Brain in GTEx v7 eQTL study NSNP_ABCA1= 49, NSNP_CPT1A = 1, and the ADNI blood (NSNP_ABCA1= 23, NSNP_CPT1A = 17). However, SMR/HEIDI analysis did not identify a causal path between ABCA1 and CPT1A gene expression and metabolite concentrations. In the blood, MRPL47 was identified as the most likely gene whose expression levels were associated with C3 and histidine metabolite levels because of causality/pleiotropy at the same underlying causal variant (rs10513761) while SLC22A5 was highly associated with C14.1, C14.2, and C18.2 metabolite levels because of causality/pleiotropy at the same underlying causal variant (rs2631360) (SMR-multi corrected p-value < 0.05; Supplementary Table S7).

It is important to note that the presumptive mechanism proposed by this study is essentially based on a set of ‘correlations’, which may or may not indicate causative linkages among the observed variables. Further animal model studies would help to understand the causative linkage between genes/proteins and metabolites. For example, ABCA1 is not only a key factor for ApoE particle lipidation in the brain, as discussed above, but also plays a crucial role in cholesterol and phospholipid homeostasis in the whole body. Therefore, it is expected that ABCA1 has many functions involving the cellular membrane and subcellular organelles. The association of ABCA1 with PC and lysoPC species revealed in the study clearly indicates such a connection. Further investigation is needed to determine whether alterations in phospholipid homeostasis induced by ABCA1 expression and Adiponectin lead to changes in general mitochondrial function, which subsequently affect energy metabolism and substrate utilization. The importance of ABCA1 beyond the lipidation of ApoE particles in the brain and association with AD pathogenesis should be recognized using the transgenic ABCA1 mice model. We could measure the levels of acylcarnitines, BCAA as well as phosphatidylcholine and cholesterol efflux from ABCA1 expressing cells and APOE lipidation ex vivo. Since ABCA1 is upregulated in AD brains, compared with control, the measurement of metabolites and their upstream regulators in ABCA1 overexpressed mice would help us identify the mechanism between ABCA1 and short-chain acylcarnitines and lysophosphatidylcholine.

There are some tool compounds available to explore ABCA1 and CPT1A involved pathways. Multiple HDL apolipoproteins, including apolipoproteins A-I and A-II, interact with ABCA1 and activate multiple signaling pathways such as Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK2/STAT3), protein kinase A, Rho family G protein CDC42, and protein kinase C [93]. The activation of protein kinase A and Rho family G protein CDC42 involve in the regulation of ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux, and JAK2/STAT3 regulates both ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux and anti-inflammation [93]. Liver X receptors (LXR) and Retinoic X Receptors (RXR) are the other regulators of ABCA1 transcription [94]. Bexarotene, an FDA-approved RXR agonist, decreases amyloid-beta plaque accumulation and cognitive impairment, and increases amyloid-beta clearance in mice [95–98]. On the other hand, Etomoxir, an inhibitor of CPT1A, is a small molecule that prevents fatty acid oxidation, and induces oxidative stress [99]. Etomoxir inhibits the formation of acyl-carnitine and the transport of fatty acyl-CoA into the mitochondria and is an efficient CPT1A blocker to treat anhedonia and inflammation in depression [100]. The effectiveness of these compounds for treating AD need be further investigated.

Besides animal models, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provides an excellent opportunity to identify fatty acid metabolism associated genes and their upstream regulators during the beta-oxidation in AD [101, 102]. Since long-chain fatty acids could not diffuse the mitochondrial inner membrane without the carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) 1, translocase, and CPT2 during fatty acid breakdown [103], we could use the fatty acid oxidation-related metabolites to the induction of iPSCs to better understand how the reaction mediated by CPT1A and CACT (Carnitine/Acylcarnitine Translocase) is disturbed during the disease progression. iPSC-based model systems and CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing of iPSCs [102] will be critical in understanding the roles of CPT1A and ABCA1 as well as their variations/mutations may modify AD risk. We could investigate the essential metabolites and factors required for the formation of pathology using a human brain tissue model from iPSC cells [102, 104]. While iPSCs are stripped of their aging brain epigenome, there are strong polygenic risk associations with AD and related dementia traits [105–107]. The polygenic risk approach using the novel AD candidate genes identified here will help us define the experimental models and systems to test the associated metabolites.

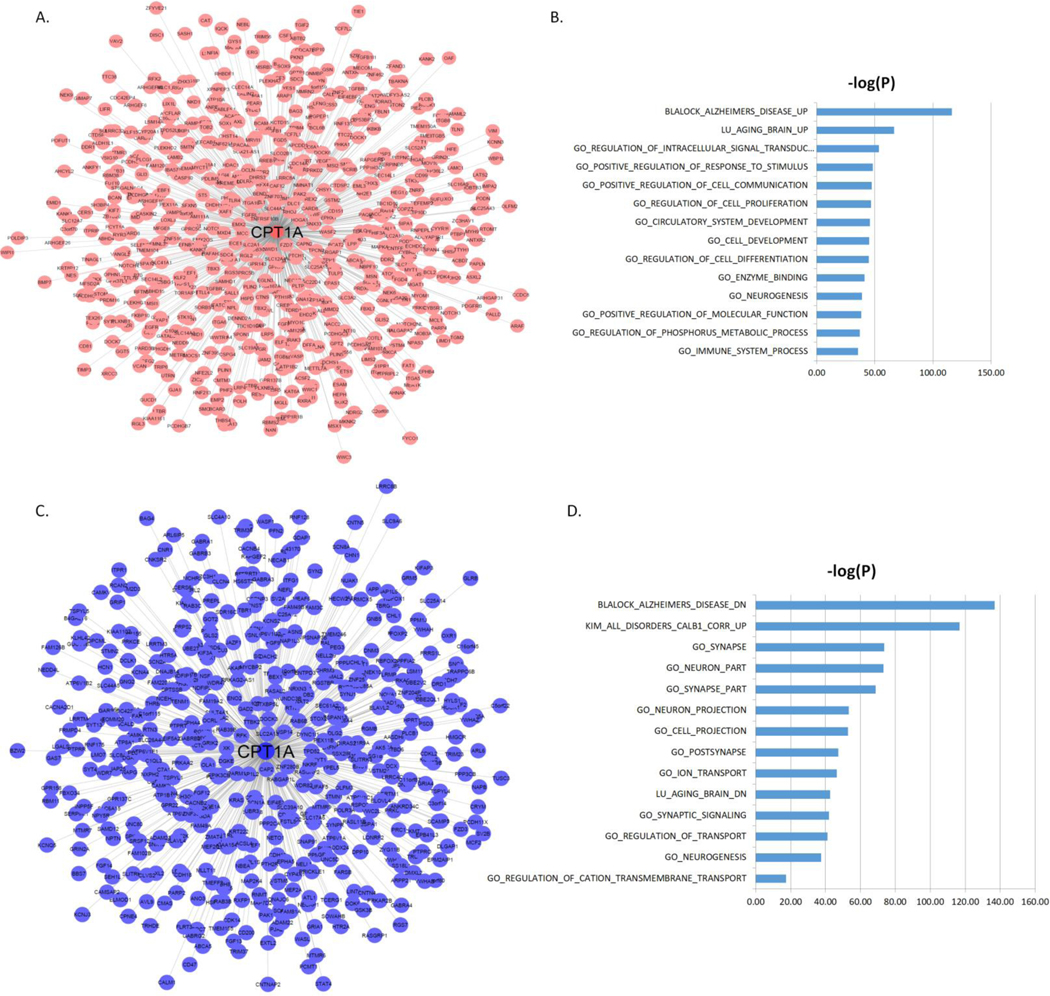

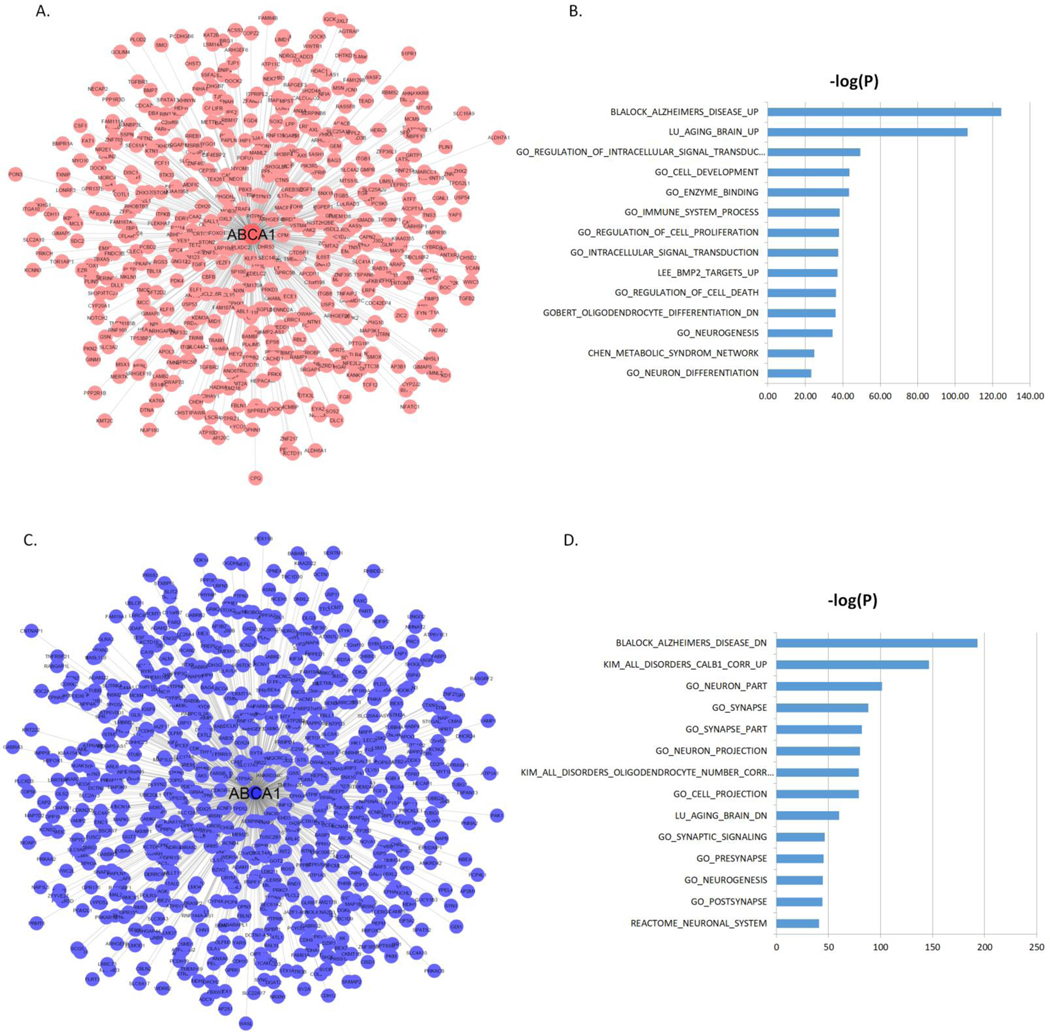

3.2.4. ABCA1 and CPT1A centered gene co-expression subnetworks are enriched for AD signatures

To understand the functional contexts in which CPT1A and ABCA1 operate in AD, we construct CPT1A and ABCA1 centered gene co-expression networks using six gene expression datasets from six different brain regions in three AD cohorts of human postmortem brains, including the Mount Sinai Brain Bank (MSBB) AD cohort (4 cortical regions) [60], the ROSMAP RNA-seq (DLPFC) [61, 62] and the Mayo Clinic cohort (TCX) [63] (Supplemental Table S8). CPT1A is positively correlated with 765 genes and negatively correlated with 621 genes (Figure 3A–C; Supplementary Table S9), while ABCA1 is positively correlated with 675 genes and negatively correlated with 806 genes) (Figure 4A–C; Supplementary Table S10) in all six datasets (FDR corrected p-value < 10−6). The CPT1A-centered subnetwork is enriched for AD signatures and neuronal system-related pathways such as synapse, synapse part, neuron part, metabolic process, synaptic signaling, neurogenesis and immune system (Figure 3B–D; Supplementary Table S11–S12). The ABCA1 centered subnetwork is enriched for known AD gene signatures and pathways such as immune system, neuron part, tyrosine kinase signaling, metabolic syndrome, synaptic signaling, and metabolic process (Figure 4B–D; Supplementary Table S13–S14).

Figure 3. CPT1A centered co-expression networks.

(A) The genes positively correlated with CPT1A (FDR < 10−6). (B) MSigDB GO and canonical pathways enriched in the CPT1A centered subnetwork shown in (A). (C) The genes negatively correlated with CPT1A (FDR < 10−6). (D) MSigDB GO and canonical pathways enriched in the CPT1A centered subnetwork shown in (C). The blue bars represent the –log10 values of the adjusted p-values.

Figure 4. ABCA1 centered co-expression networks.

(A) The genes positively correlated with ABCA1 (FDR < 10−6). (B) MSigDB GO and canonical pathways enriched in the ABCA1 centered subnetwork shown in (A). (C) The genes negatively correlated with ABCA1 (FDR < 10−6). (D) MSigDB GO and canonical pathways enriched in the ABCA1 centered subnetwork shown in (C). The blue bars represent the –log10 values of the adjusted p-values.

Co-Expression Metabolite Protein Network Analysis establishes a link between metabolites and protein network associated with AD

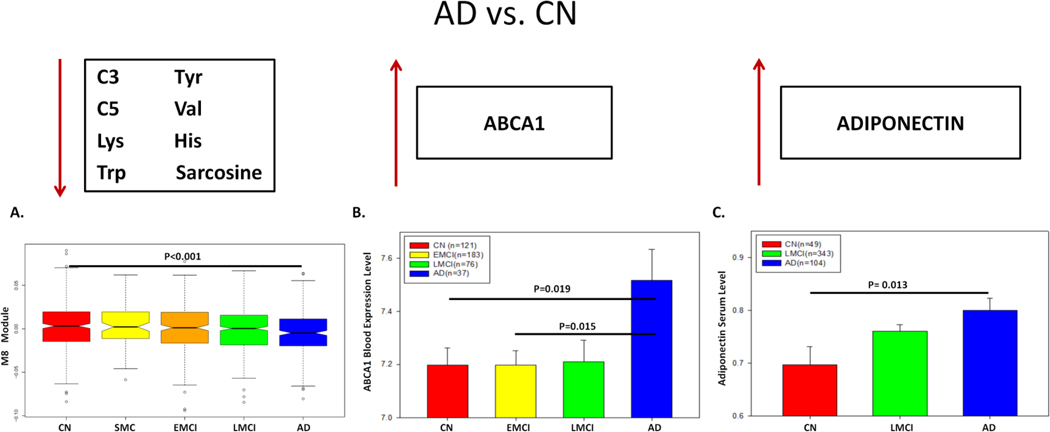

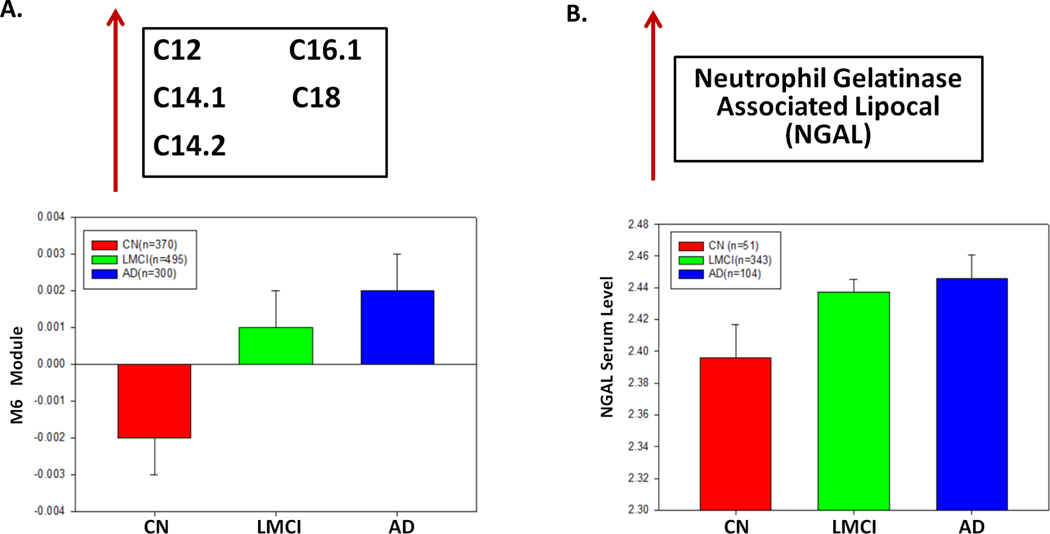

Since ABCA1 plays an important role in cholesterol and phospholipid transport and ABCA1 gene expression is controlled by Adiponectin, an adipocyte-specific protein [92, 108, 109], we hypothesize that Adiponectin is highly correlated with the level of module M8 (short-chain acylcarnitine and amino acids). In ADNI-1, 496 individuals (CN=49, MCI=343, AD=104) had both metabolomic and proteomic data (N=146 proteins). Our correlation analysis reveals that Adiponectin is significantly correlated with the modules M8 and M3 with corrected p-value = 0.012 and 0.013, respectively. Moreover, we identify several key proteins that are highly correlated with medium/long-chain acylcarnitines (FDR < 0.05) (Table 3). However, Neutrophil Gelatinase Associated Lipocalin (NGAL), Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), Thrombomodulin, Leptin, Myoglobin, Ferritin, and AXL Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (AXL) are among the proteins highly correlated with medium/long-chain acylcarnitine module (M6). Since Adiponectin has been shown to play an essential role in the regulation of ABCA1 expression [92] and be correlated with AD [110], we test if ABCA1 gene expression and Adiponectin levels changed similarly across diagnosis groups. Opposite to the decrease of the short-chain acylcarnitines and amino acids in M8 in the AD group (Figure 5A), ABCA1 mRNA expression and adiponectin levels increase in the AD patients compared with cognitively normal individuals (Figure 5B–C). Our finding suggests interactions among ABCA1, Adiponectin, short-chain acylcarnitines and amino acids in AD. NGAL is the other interesting finding highly correlated with our medium/long-chain acylcarnitine module (M6). Both the metabolites in M6 (Figure 6A) and NGAL (Figure 6B) increase in AD, comparing the cognitively normal group (p-value < 0.05).

Table 3:

The top 10 proteins most correlated with the top AD associated metabolite modules which include acylcarnitines and amino acids.

| Protein | Top Modules | Rho value | P-value | P.adj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin..ug.mL. | M3 | −0.168 | 0.00017 | 0.01241 |

| Adiponectin..ug.mL. | M8 | −0.165 | 0.00022 | 0.012653 |

| Hepatocyte Growth Factor..HGF…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.225 | 4.20×10−7 | 0.000173 |

| Neutrophil.Gelatinase.Associated.Lipocal..ng.ml. | M6 | 0.22 | 7.90×10 −7 | 0.000173 |

| Thrombomodulin..TM…ng.ml. | M6 | 0.188 | 2.60×10−5 | 0.003614 |

| Myoglobin..ng.mL. | M6 | 0.185 | 3.30×10−5 | 0.003614 |

| Chemokine.CC.4..HCC.4…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.17 | 0.00014 | 0.012264 |

| FASLG.Receptor..FAS…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.163 | 0.00026 | 0.012653 |

| Myeloid.Progenitor.Inhibitory.Factor.1….ng.mL. | M6 | 0.163 | 0.00026 | 0.012653 |

| Cystatin.C..ng.ml. | M6 | 0.162 | 0.00029 | 0.012702 |

| CD.40.antigen..CD40…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.159 | 0.00039 | 0.015529 |

| Beta.2.Microglobulin..B2M…ug.mL. | M6 | 0.154 | 0.00059 | 0.019436 |

| Thymus.Expressed.Chemokine..TECK…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.153 | 0.00063 | 0.019436 |

| Ferritin..FRTN…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.152 | 0.00067 | 0.019436 |

| AXL.Receptor.Tyrosine.Kinase..AXL…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.151 | 0.00071 | 0.019436 |

| Vascular.Cell.Adhesion.Molecule.1..VCAM…ng.mL. | M6 | 0.152 | 0.00071 | 0.019436 |

| Brain.Natriuretic.Peptide…BNP…pg.ml. | M6 | 0.147 | 0.0011 | 0.028341 |

| Pancreatic.Polypeptide..PPP…pg.ml. | M6 | 0.141 | 0.0016 | 0.038933 |

| B.Lymphocyte.Chemoattractant..BLC…pg.ml. | M6 | 0.14 | 0.0018 | 0.041495 |

Figure 5. Integrative analysis of metabolites, genes and proteins.

(A) The expression level of the module M8 (i.e., the eigen-metabolite represented by the first PC of the module), which contains short-chain acylcarnitine and amino acid, varies significantly across five diagnosis groups (p-value < 0.05). (B) ABCA1 mRNA level in the blood is significantly different across four diagnosis groups. (C) Adiponectin protein level in the blood is significantly different across AD, LMCI and control.

Figure 6. Medium/long chain acylcarnitines are significantly associated with NGAL protein level in AD.

(A) Medium/long-chain acylcarnitines module (M6) expression level increases during the disease progression from control to LMCI and to AD. (B) NGAL protein level in blood is significantly different across diagnosis groups (p-value < 0.05).

Adiponectin is released from the adipose tissue as a hormone and is associated with many cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases [111]. Adiponectin has a protective effect on oxidative stress due to amyloid-beta accumulation in the brain [112]. Adiponectin is a key hormone in the regulation of energy metabolism and fatty acid homeostasis and plays a key role in the development of diabetes/obesity and the modulation of brain insulin balance and amyloid-beta in the early stage of AD [111, 113]. The connection of short-chain acylcarnitines with this gene and other related ones is obvious. Modulating adiponectin expression to reduce short-chain acylcarnitine production and accumulation could be important in both diabetes and AD. Adiponectin, as a potential drug target for the treatment of diabetes, has been well recognized. Thus, Adiponectin, which serves as a potential candidate for the treatment of AD, could also be considered. Our integrative analysis of metabolomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data revealed decreased short-chain acylcarnitines and amino acids and increased ABCA1 mRNA and Adiponectin protein levels in AD comparing cognitively healthy group. This novel result may suggest that the increase of circulating adiponectin levels and ABCA1 expression could be a compensatory effect against neurodegeneration. ABCA1 overexpressed mice model would help us to understand the upstream regulators and biological processes better.

Conclusion

This report represents emerging novel evidence of metabolic network failures related to AD pathology. A new perspective for prevention and treatment of AD involves key genetic drivers and pathways underlying metabolomic changes in the blood by integrating metabolomic, genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data in AD. This effort aims to reassess the role of acylcarnitines and amines, and their potential upstream genetic and transcriptional regulators through this highly integrative analysis of multi-omics data in AD, which paves the way for identifying novel biomarkers as well as therapeutic targets for AD. Detection of changes of small molecule metabolites in blood, cells, tissues, and cerebrospinal fluid at the early stage of AD is challenging but would help us to understand the metabolic mechanisms underlying AD. Metabolite-based biomarker studies enable us to interpret the elusive pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases. AD is a heterogeneous disorder associated with multiple clinical and pathological phenotypes as well as many genetic risk factors. Unraveling the heterogeneity of AD will pave the way for not only understanding the mechanisms of AD but also developing novel therapeutics. For this consideration, a future direction is to identify AD subtypes using metabolomic data.

In conclusion, the identification of acylcarnitines enriched modules and their potential upstream genetic and transcriptional regulators through this highly integrative analysis of multi-omics data in AD paves the way for identifying novel biomarkers as well as therapeutic targets for AD. Our novel findings may suggest that an increase of circulating adiponectin and metabolite dependent ABCA1 mRNA expression could be a compensatory effect against neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in parts by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Aging (U01AG046170, RF1AG054014, RF1AG057440, R01AG057907, R01AG068030, U01AG052411, R01AG062355, U01AG058635).

The brain transcriptomic data from the MSBB, ROS/MAP and Mayo cohorts are available via the AD Knowledge Portal (https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org). The AD Knowledge Portal is a platform for accessing data, analyses, and tools generated by the Accelerating Medicines Partnership (AMP-AD) Target Discovery Program and other National Institute on Aging (NIA)-supported programs to enable open-science practices and accelerate translational learning. Data is available for general research use according to the following requirements for data access and data attribution (https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/#/DataAccess/Instructions).

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education,and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium: “Data used in the preparation of this article were generated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium (ADMC). Data generation was funded wholly or in part by the following grants and supplements thereto: NIA R01AG046171, RF1AG051550, RF1AG057452, R01AG059093, RF1AG058942, U01AG061359, U19AG063744 and FNIH: #DAOU16AMPA awarded to Dr. Kaddurah-Daouk at Duke University along with a large number of academic centers. As such, the investigators within the ADMC, not listed specifically in this publication’s author’s list, provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this manuscript. A complete listing of ADMC investigators can be found at: https://sites.duke.edu/adnimetab/team/.”

Data was generated by the Duke Metabolomics and Proteomics Shared Resource using protocols published previously for blood samples (Toledo et al., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.020; St. John-Williams et al., https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.140; Arnold et al., https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14959-w); a custom protocol developed for this study by the Duke shared resource for the brain samples can be found at (https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn10235609).

Data on GCTOF and Lipidomics datasets were generated at UC Davis, a member of ADMC. Protocols for data generation are described at: (https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.263).

For ROS/MAP: “The results published here are in whole or in part based on data obtained from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (doi:10.7303/syn2580853). Study data were provided through NIA grant 3R01AG046171-02S2 awarded to Rima Kaddurah-Daouk at Duke University, based on specimens provided by the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, where data collection was supported through funding by NIA grants P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917, R01AG30146, R01AG36836, U01AG32984, U01AG46152, U01AG61356, the Illinois Department of Public Health, and the Translational Genomics Research Institute.” For all acknowledgement related to the source of the samples other than ROS/MAP refer text found in the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal: (https://adknowledgeportal.synapse.org/#/DataAccess/AcknowledgementStatements)

Footnotes

Data and Code Availability: The multi-Omics data in the ADNI are available at http://adni.loni.usc.edu/. The brain metabolomic data, analyses outputs, and codes are available via the AD Knowledge Portal (https://adknowledgeportal.org). The AD Knowledge Portal is a platform for accessing data, analyses, and tools generated by the Accelerating Medicines Partnership (AMP-AD) Target Discovery Program and other National Institute on Aging (NIA)-supported programs to enable open-science practices and accelerate translational learning. The data, analyses and tools are shared early in the research cycle without a publication embargo on secondary use. Data is available for general research use according to the following requirements for data access and data attribution (https://adknowledgeportal.org/DataAccess/Instructions). For access to content described in this manuscript see: http://doi.org/10.7303/syn25257534.

Data was generated by the Duke Metabolomics and Proteomics Shared Resource using protocols published previously for blood samples (Toledo et al., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.020; St. John-Williams et al., https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.140; Arnold et al., https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467–020-14959-w)

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

Metabolomics data is provided by the Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium (ADMC) and funded wholly or in part by the following grants and supplements thereto: NIA R01AG046171, RF1AG051550, RF1AG057452, R01AG059093, RF1AG058942, U01AG061359, U19AG063744 and FNIH: #DAOU16AMPA awarded to Dr. Kaddurah-Daouk at Duke University in partnership with a large number of academic institutions. As such, the investigators within the ADMC, not listed specifically in this publication’s author’s list, provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this manuscript. A complete listing of ADMC investigators can be found at: https://sites.duke.edu/adnimetab/team/.

Conflict of Interests Statement: The authors of this manuscript have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Shen L, et al. , Genetic analysis of quantitative phenotypes in AD and MCI: imaging, cognition and biomarkers. Brain Imaging Behav, 2014. 8(2): p. 183–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s A, 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement, 2016. 12(4): p. 459–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zetterberg H, Wahlund LO, and Blennow K, Cerebrospinal fluid markers for prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett, 2003. 352(1): p. 67–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flood DG, Marek GJ, and Williams M, Developing predictive CSF biomarkers-a challenge critical to success in Alzheimer’s disease and neuropsychiatric translational medicine. Biochem Pharmacol, 2011. 81(12): p. 1422–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veitch DP, et al. , Understanding disease progression and improving Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: Recent highlights from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Alzheimers Dement, 2019. 15(1): p. 106–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theurey P, et al. , Systems biology identifies preserved integrity but impaired metabolism of mitochondria due to a glycolytic defect in Alzheimer’s disease neurons. Aging Cell, 2019. 18(3): p. e12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuade A. and Blurton-Jones M, Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring How Genetics and Phenotype Influence Risk. J Mol Biol, 2019. 431(9): p. 1805–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M, et al. , Primary fatty amides in plasma associated with brain amyloid burden, hippocampal volume, and memory in the European Medical Information Framework for Alzheimer’s Disease biomarker discovery cohort. Alzheimers Dement, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oresic M, et al. , Metabolome in progression to Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry, 2011. 1: p. e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swain-Lenz D, et al. , Causal Genetic Variation Underlying Metabolome Differences. Genetics, 2017. 206(4): p. 2199–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganeshan K. and Chawla A, Metabolic regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol, 2014. 32: p. 609–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X, et al. , Response of Gut Microbiota to Metabolite Changes Induced by Endurance Exercise. Front Microbiol, 2018. 9: p. 765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujisaka S, et al. , Diet, Genetics, and the Gut Microbiome Drive Dynamic Changes in Plasma Metabolites. Cell Rep, 2018. 22(11): p. 3072–3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mapstone M, et al. , Plasma phospholipids identify antecedent memory impairment in older adults. Nat Med, 2014. 20(4): p. 415–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han X, et al. , Metabolomics in early Alzheimer’s disease: identification of altered plasma sphingolipidome using shotgun lipidomics. PLoS One, 2011. 6(7): p. e21643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barupal DK, et al. , Sets of coregulated serum lipids are associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Alzheimers Dement (Amst), 2019. 11: p. 619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barupal DK, et al. , Generation and quality control of lipidomics data for the alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative cohort. Sci Data, 2018. 5(1): p. 180263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toledo JB, et al. , Metabolic network failures in Alzheimer’s disease: A biochemical road map. Alzheimers Dement, 2017. 13(9): p. 965–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varma VR, et al. , Brain and blood metabolite signatures of pathology and progression in Alzheimer disease: A targeted metabolomics study. PLoS Med, 2018. 15(1): p. e1002482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkins JM and Trushina E, Application of Metabolomics in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurol, 2017. 8: p. 719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamate D, et al. , A metabolite-based machine learning approach to diagnose Alzheimer-type dementia in blood: Results from the European Medical Information Framework for Alzheimer disease biomarker discovery cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 2019. 5: p. 933–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu J, et al. , Increasing the Power to Detect Causal Associations by Combining Genotypic and Expression Data in Segregating Populations. PLoS Comput Biol, 2007. 3(4): p. e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu J, et al. , Integrating large-scale functional genomic data to dissect the complexity of yeast regulatory networks. Nat Genet, 2008. 40(7): p. 854–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haure-Mirande JV, et al. , Integrative approach to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: deficiency of TYROBP in cerebral Abeta amyloidosis mouse normalizes clinical phenotype and complement subnetwork molecular pathology without reducing Abeta burden. Mol Psychiatry, 2019. 24(3): p. 431–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, et al. , Validation of candidate causal genes for obesity that affect shared metabolic pathways and networks. Nat Genet, 2009. 41(4): p. 415–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B, et al. , Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell, 2013. 153(3): p. 707–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang M, et al. , Transformative Network Modeling of Multi-omics Data Reveals Detailed Circuits, Key Regulators, and Potential Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckmann ND, et al. , Multiscale causal networks identify VGF as a key regulator of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang IM, et al. , Systems analysis of eleven rodent disease models reveals an inflammatome signature and key drivers. Mol Syst Biol, 2012. 8: p. 594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong LP, et al. , Increased expression of Annexin A2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Oral Biol, 2009. 54(1): p. 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu J, et al. , Characterizing dynamic changes in the human blood transcriptional network. PLoS Comput Biol, 2010. 6(2): p. e1000671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redestig H. and Costa IG, Detection and interpretation of metabolite-transcript coresponses using combined profiling data. Bioinformatics, 2011. 27(13): p. i357–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lempp M, et al. , Systematic identification of metabolites controlling gene expression in E. coli. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chubukov V, et al. , Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2014. 12(5): p. 327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Browning DF and Busby SJ, Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2016. 14(10): p. 638–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jozefczuk S, et al. , Metabolomic and transcriptomic stress response of Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol, 2010. 6: p. 364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donatti A, et al. , Circulating Metabolites as Potential Biomarkers for Neurological Disorders-Metabolites in Neurological Disorders. Metabolites, 2020. 10(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kori M, et al. , Metabolic Biomarkers and Neurodegeneration: A Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. OMICS, 2016. 20(11): p. 645–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pahnke J, Langer O, and Krohn M, Alzheimer’s and ABC transporters--new opportunities for diagnostics and treatment. Neurobiol Dis, 2014. 72 Pt A: p. 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schumacher T, et al. , ABC transporters B1, C1 and G2 differentially regulate neuroregeneration in mice. PLoS One, 2012. 7(4): p. e35613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Havelund JF, et al. , Biomarker Research in Parkinson’s Disease Using Metabolite Profiling. Metabolites, 2017. 7(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schipper HM and Song W, A heme oxygenase-1 transducer model of degenerative and developmental brain disorders. Int J Mol Sci, 2015. 16(3): p. 5400–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeWitt PA, et al. , Metabolomic biomarkers as strong correlates of Parkinson disease progression. Neurology, 2017. 88(9): p. 862–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa AC, et al. , Three plasma metabolites in elderly patients differentiate mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2020. 270(4): p. 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]