Abstract

Biases introduced in early-stage studies can lead to inflated early discoveries. The Risk of Generalizability Biases (RGBs) identifies key features of feasibility studies that, when present, lead to reduced impact in a larger trial. This meta-study examined the influence of RGBs in adult obesity interventions. Behavioral interventions with a published feasibility study and a larger-scale trial of the same intervention (e.g., pairs) were identified. Each pair was coded for the presence of RGBs. Quantitative outcomes were extracted. Multi-level meta-regression models were used to examine the impact of RGBs on the difference in the effect size (ES, standardized mean difference) from pilot to larger-scale trial. A total of 114 pairs, representing 230 studies, were identified. Overall, 75% of the pairs had at least one RGB present. The four most prevalent RGBs were duration (33%), delivery agent (30%), implementation support (23%), and target audience (22%) bias. The largest reductions in the ES were observed in pairs where an RGB was present in the pilot and removed in the larger-scale trial (average reduction ES −0.41, range −1.06 to 0.01), compared to pairs without an RGB (average reduction ES −0.15, range −0.18 to −0.14). Eliminating RGBs during early-stage testing may result in improved evidence.

Keywords: Scaling, Translation, Intervention, Pilot

Introduction

In the US alone, investing in clinical trials is a multibillion-dollar enterprise. For behavioral interventions it is common to perform one or more early-stage studies before launching larger-scale trials 1,2. These early-stage studies (referred to herein as pilot/feasibility studies) lay the foundation for more definitive hypothesis testing in larger-scale clinical trials by providing preliminary evidence on the effects of an intervention and evidence for the feasibility of trial (e.g., recruitment) and intervention (e.g., fidelity) related facets 3. Pilot/feasibility studies are consistently depicted as playing key roles in translational science frameworks for developing behavioral interventions by providing evidence about whether an intervention can be done and demonstrates initial promise 1,2,4,5. Well-designed and executed pilot/feasibility studies, thus, serve as the cornerstone for decisions regarding the execution of larger-scale clinical trials, and funding for larger-scale trials often requires these pilot studies (e.g., R01 grants from US NIH).

A challenge many researchers face in the design and execution of a pilot/feasibility study is the ability to translate initially promising findings of an intervention into an intervention that demonstrates efficaciousness when evaluated in a larger-scale trial. The transition from early-stage, often small, pilot/feasibility studies to progressively larger trials is commonly associated with a respective drop in the impact of an intervention that can render an intervention tested in the larger trial completely inert 6–8. Referred to as a scaling penalty 9,10 in the dissemination/implementation literature, a similar phenomenon is observed in the sequence of studies from pilot/feasibility to progressively larger size trials 11.

This initial promise followed by reduced effectiveness may be from the introduction of biases during the early-stage of testing that lead to exaggerated early effects. Biases, in the scientific literature on clinical trials, are typically thought of in relation to internal validity, which focus on issues resulting from randomization and blinding procedures, incomplete data and selective reporting of outcomes 12,13. While important, internal validity issues do not address other contextual factors that may lead to over- or underestimation of effects, especially in behavioral interventions. In the behavioral science field, a newly developed set of biases have been conceptualized that address contextual factors in behavioral interventions that, when present, could lead to inflated effects 11. Referred to as Risk of Generalizability Biases (RGBs), these focus on contextual factors associated with external validity or the degree to which features of the intervention and sample in the early-stage pilot/feasibility study are not scalable or generalizable to the next stage of testing in a larger, more well-powered trial. RGBs focus broadly on the conduct of behavioral interventions by including items related to where an intervention was delivered, by whom and to whom an intervention was delivered, and other support necessary to deliver the intervention. The RGBs focus on changes in these from the early-stage pilot/feasibility studies to the larger-scale trial and how such changes can potentially lead to diminished effects in the large-scale trial. The RGBs, therefore, represent contextual features that any number of behavioral interventions, regardless of theoretical and methodological approach or behavior targeted, encounter in the design and execution of an intervention.

An initial study 11 provided preliminary support for the impact of RGBs in childhood obesity trials. This study showed larger-scale trials that were informed by pilot/feasibility trials with an RGB had substantially greater reductions in outcomes in comparison to larger-scale trials informed by pilot/feasibility studies without an RGB. This, however, was demonstrated in a relatively small number of interventions (total of 39) that had a published pilot/feasibility study and a published larger-scale trial on a topic related to childhood obesity. Given pilot/feasibility studies provide evidence to inform decisions about investing in larger-scale trials, they should be conducted without the introduction of biases. We believe the RGBs represent a unique set of biases behavioral interventionist face and have the potential to inform important aspects in the design and execution of pilot/feasibility studies. The purpose of this study was to build upon previous evidence of the influence of RGBs and evaluate their impact in a sample of published pilot/feasibility studies and larger-scale trials of the same behavioral intervention on a topic related to adult obesity.

Methods

The methods are similar to the methods used in a previous meta-epidemiological investigation of RBGs in trials of childhood obesity 11. Specifically, comprehensive, meta-epidemiological review procedures were used to identify behavioral interventions focused on adult obesity (age range ≥18yrs) that have a published preliminary, early-stage testing of the intervention and a published larger-scale trial of the same intervention. Consistent with our prior work, behavioral interventions were defined as social science/public health intervention involving a coordinated set of activities targeted at one or more levels including interpersonal, intrapersonal, policy, community, macro-environments, micro-environments, and institutions 1,14–16 and obesity related topics could include diet, exercise, physical activity, screen time, sleep, sedentary behavior or combination of these behaviors. “Behavioral intervention pilot studies” were defined as studies which test the feasibility of a behavioral intervention and/or provide evidence of a preliminary effect(s) in a hypothesized direction 1,17,18. These studies are conducted separately from, and prior to, larger-scale trials, with the results used to inform the subsequent testing of the same or refined intervention 1,18. Behavioral intervention pilot studies can also be referred to as “feasibility,” “preliminary,” “proof-of-concept,” “vanguard,” “novel,” or “evidentiary”. 1,19,20

Data Sources and Search Strategy

To identify pilot/feasibility studies and larger-scale trials of behavioral interventions on a topic related to adult obesity the following procedures were used. First, a combination of controlled vocabulary terms (e.g., MeSH, Emtree), free-text terms, and Boolean operators were used to identify eligible reviews and meta-analysis across OVID Medline/PubMed; Embase/Elsevier; EBSCOhost, and Web of Science. Searches for meta-analyses and reviews allowed for the identification of a large number of behavioral intervention studies in a time effective manner and is a primary mechanism of study identification in meta-epidemiological studies 21. Each search contained one or more of the following terms for participant age – adult (i.e., 18yrs and older) – and one of the follow terms related to obesity – obesity, weight, physical activity, diet, screen, sleep, sedentary, exercise, and study design – systematic review or meta-analysis of behavioral interventions. A detailed record of the search strategy is provided in the Supplemental Material.

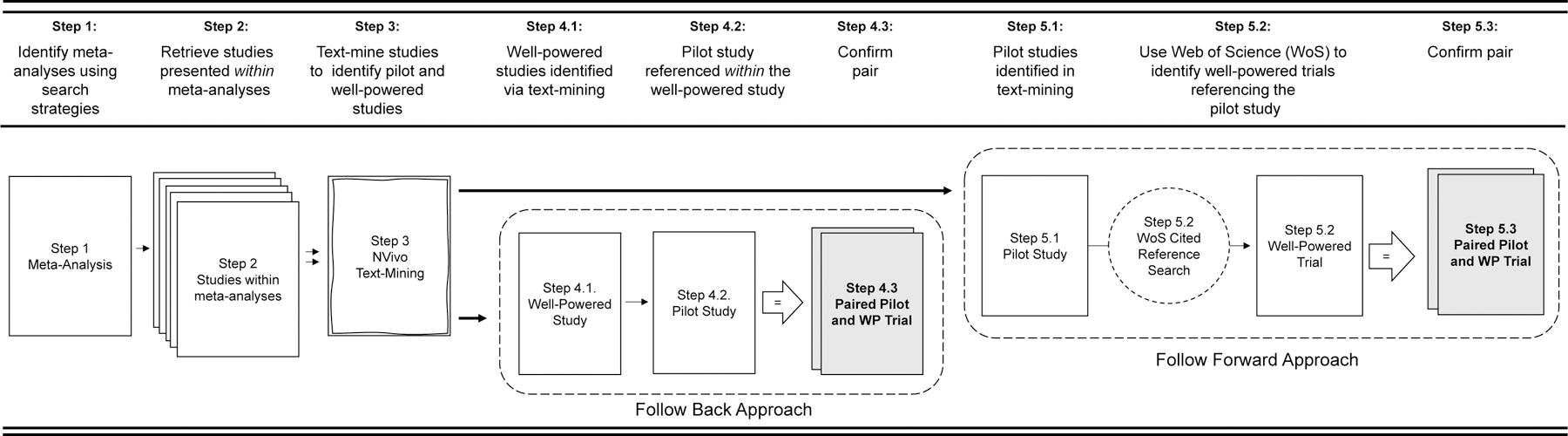

All identified systematic reviews and/or meta-analysis were uploaded in an EndNote Library (v. X9.2). Each resulting title/abstract of the systematic reviews and meta-analysis were screened by at least two independent reviewers (LV, SB, AJ) in Covidence (Covidence.org, Melbourne, Australia) prior to full-text review. All articles included with the systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses were retrieved and uploaded into an NVivo (v.12, Doncaster, Australia) file for text-mining. Articles from the reviews were text-mined using text search query to identify them as either 1) self-identified preliminary testing of an intervention or 2) larger-scale trial referring to prior preliminary work. This was done using terms such as “pilot, feasible, preliminary, protocol previously, rationale, elsewhere described, prior work” to flag sections of text. Once flagged, each section of text was reviewed to determine whether it met inclusion criteria and then tagged as either a larger-scale or smaller-scale study. After being identified and tagged as a larger-scale trial, a “follow back” approach was used to identify references to preliminary testing of an intervention within the body of the article (Figure 1, Steps 4.1 −4.2). Where larger-scale trials indicated previous published pilot/feasibility testing of the intervention, the referenced article was retrieved and reviewed to determine if it met the definition of pilot/feasibility study. For studies self-identified as pilot/feasibility, studies were “follow forward” using the Web of Science Reference Search interface to identify any subsequent published study referencing the identified pilot/feasibility study as preliminary work (Figure 1, Steps 5.1–5.2; LV, SB). Successfully paired pilot/feasibility studies and larger-scale trials identified in both the forward and backward approaches were catalogued (Figure 1, Steps 4.3 & 5.3) and narrative and analytic information was extracted (AJ, SB, LV) prior to meta-analytic modeling.

Figure 1.

Diagram of search procedures of locating pilot studies and larger-scale trial pairs.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included, studies were required to study adults 18 years of age or older participating in a behavioral intervention on a topic related to obesity. Pairs of studies were included if they had published pilot/feasibility study and a larger-scale trial of the same or similar intervention and were published in English.

Exclusion Criteria

Pairs were excluded if either the pilot study reported only outcomes associated with compliance to an intervention (e.g., feasibility metrics, attendance, adherence, N = 13) and no measures on primary or secondary outcomes, or the published pilot study or larger-scale trial provided point estimates for the outcomes but did not provide a measure of variance (e.g., SD, SE, 95CI, N = 15).

Data Management Procedures

Coding Risk of Generalizability Biases.

The risk of generalizability biases were coded in each pilot and larger-scale trial pair according to previously established criteria 11 and are defined in Table 1. Within each pair of pilot/feasibility study and larger-scale trial, two reviewers independently reviewed the entire article to identify the presence or absence of one or more RGBs. For the purpose of this review, eight of the nine originally defined RGBs were extracted for analyses, with the RGB outcome bias not coded because no analytical comparison for outcomes between a pilot and larger-scale trial could be made on this RGB. RGBs were established by comparing the description provided in the pilot/feasibility study regarding the intensity of the intervention, the amount of support to implement, who delivered the intervention, to whom the intervention was delivered, the duration of the intervention, the locale of where the intervention was delivered, the types of measurements used to collect outcomes, and the direction of the findings. For example, a pilot/feasibility study may indicate all intervention sessions were led by the first author, whereas in the larger-scale trial the intervention was delivered by community health workers. In this instance, the pair would be coded as having the risk of delivery agent bias present in the pilot/feasibility study and not in the larger-scale trial. Where discrepancies were encountered or clarifications were required a third reviewer was brought in to assist in the final coding.

Table 1.

Operational definition of risk of generalizability biases.

| Risk of Generalizability Bias | Example of Bias | |

|---|---|---|

|

Intervention Intensity Bias |

What is the potential for difference(s) between… …the number and length of contacts in the pilot study compared to the number and length of contacts in the larger-scale trial of the intervention? |

7 sessions in 7 weeks in pilot/feasibility study vs 4 sessions over 12 weeks in larger-scale trial 24 contacts per week for 12 weeks in pilot/feasibility vs 2 contacts per week for 12 weeks in larger-scale trial |

| Implementation Support Bias | …the amount of support provided to implement the intervention in the pilot study compared to the amount of support provided in the larger-scale trial? | Any adherence issues noted were immediately addressed in ongoing supervision At the end of each session, the researcher debriefed with the interventionist to discuss reasons for the variation in approach and to maintain standardization, integrity of implementation, and reliability among interventionists |

| Intervention Delivery Agent Bias | …the level of expertise of the individual(s) who delivered the intervention in the pilot study compared to who delivered the intervention in the larger-scale trial | All intervention sessions were led by the first author The interventionists were highly trained doctoral students or a postdoc |

| Target Audience Bias | …the demographics of those who received the intervention in the pilot study compared to those who received the intervention in the larger-scale trial | Affluent and educated background, mostly White non-Hispanic Participants were predominately healthy and well-educated |

| Intervention Duration Bias | …the length of the intervention provided in the pilot study compared to the length of the intervention in larger-scale trial? | 8-week intervention in pilot/feasibility study to 12-month intervention in larger-scale trial |

| Setting Bias | …the type of setting where the intervention was delivered in the pilot study compared to the setting in the larger-scale trial | A convenience sample of physicians, in one primary care office practice agreed to participate. They were approached because of a personal relationship with one of the investigators who also was responsible for providing physician training in the counseling intervention. The study was conducted at a university health science center |

| Measurement Bias | …the measures employed in the pilot study compared to the measures used in the larger-scale trial of the intervention for primary/secondary outcomes? | Use of objective measures in pilot to self-report measures in larger-scale trial |

| Directional Conclusions | Are the intervention effect(s) in the hypothesized direction for the pilot study compared to those in the larger-scale trial? | Outcomes in the opposite direction (e.g., control group improved more so than treatment group) |

Note: Based on definitions originally appearing in Beets et al. (2020)

Meta-Analytical Procedures.

Standardized difference of means (SDM) effect sizes were calculated for each study across all reported outcomes. The steps outlined by Morris and DeShon 22 were used to create effect size estimates from studies using different designs across different interventions (independent groups pre-test/post-test; repeated measures single group pre-test/post-test) into a common metric. For each study, individual effect sizes and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated for all outcome measures reported in the studies.

To ensure comparisons between pilot and larger-scale pairs were based upon similar outcomes, we classified the outcomes reported across pairs (i.e., pilot and larger-scale trial) into seven categories that represented all the data reported 23. These were measures of body composition (e.g., BMI, percent body fat, skinfolds), physical activity (e.g., moderate-to-vigorous physical activity), sedentary behaviors (e.g., TV viewing, sitting), psychosocial (e.g., self-efficacy, social support), diet (e.g., kcals, fruit/vegetable intake), physiological (e.g., HLD, LDL, glucose), or sleep (e.g., duration, onset, offset). Only outcomes within common categories represented across both the pilot and the larger-scale trial were included in analyses. For instance, a study could have reported data related to body composition, physiological, physical activity in both the pilot and larger-scale trial, but also reported sedentary outcomes for the pilot only and psychosocial related outcomes for the larger-scale only. In this scenario, only the body composition, physiological, and physical activity variables would be compared across the two studies within the pair. For studies that reported multiple outcomes within a given category, all outcomes were extracted and the shared correlation among outcomes from the same trial were accounted for in the analytical models (see below for details).

All individual outcome measures reported within categories across pairs were extracted and entered into an Excel file. Once a pair was completely extracted and reported data transformed (e.g., standard errors transformed into standard deviations), data were transferred into Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software (v3.3.07) to calculate a SDM for effects reported in a study. After all outcomes across all pairs were entered into CMA, the complete data file was exported as a comma separated file and uploaded into the R environment 24 for final data analyses to occur.

Consistent with our previous study 11 all effect sizes were corrected for differences in the direction of the scales so that positive effect sizes corresponded to improvements in the intervention group, independent of the original scale’s direction. This correction was performed for simplicity of interpretive purposes so that all effect sizes were presented in the same direction and summarized within and across studies.

The primary testing of the impact of the biases was performed by comparing the change in the SDM from the pilot study to the larger-scale trial for studies coded with and without a given bias present. All studies reported more than one outcome effect; therefore, summary effect sizes were calculated using a random-effects multi-level robust variance estimation meta-regression model 25–27, with outcomes nested within studies nested within pairs in the R environment24 using the package metafor27. This modeling procedure is distribution free and can handle the non-independence of the effects sizes from multiple outcomes reported within each of the seven categories reported within a single study. The difference in the SDM from the pilot and larger-scale trial were quantified according to previously defined formulas for the scale-up penalty 9,10 which is calculated as: the SDM of the larger-scale trial was divided by the SDM of the pilot and then multiplied by 100. A value of 100% indicates identical SDMs in both the pilot and larger-scale trial. A value of 50% indicates the larger-scale trial was half as effective as the pilot study, a value above 100% indicates the larger-scale trial is more effective than the pilot, while a negative value indicating that the direction of the effect in the larger-scale trial is opposite that of the pilot.

A secondary evaluation of the impact of the biases was performed by examining the presence/absence of the biases on the occurrence of a nominally statistically significant (i.e., P≤.05) outcome in the larger-scale trials. These analyses were restricted to the p-values for the individual outcomes in the larger-scale trials, only. P-values for each individual effect size were estimated within the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software based upon the effect size and its associated standard error. P-values from publications were not used because they were either not reported or reported as truncated values (e.g., P<.01). P-values were dichotomized as P>0.05 and P≤.05 based on conventional behavioral intervention studies. Logistic regression models, using robust variance estimators, were used to examine the odds of a nominally statistically significant outcome in the larger-scale trial based on the presence/absence of the biases. Across all models, we controlled for the influence of all other biases. Since it has been recently proposed that statistical significance thresholds should become p<0.005 rather than p<0.05 (ref. Benjamin et al. NHB; Ioannidis JAMA), we also explored these analyses using the P<0.005 threshold 28,29.

Results

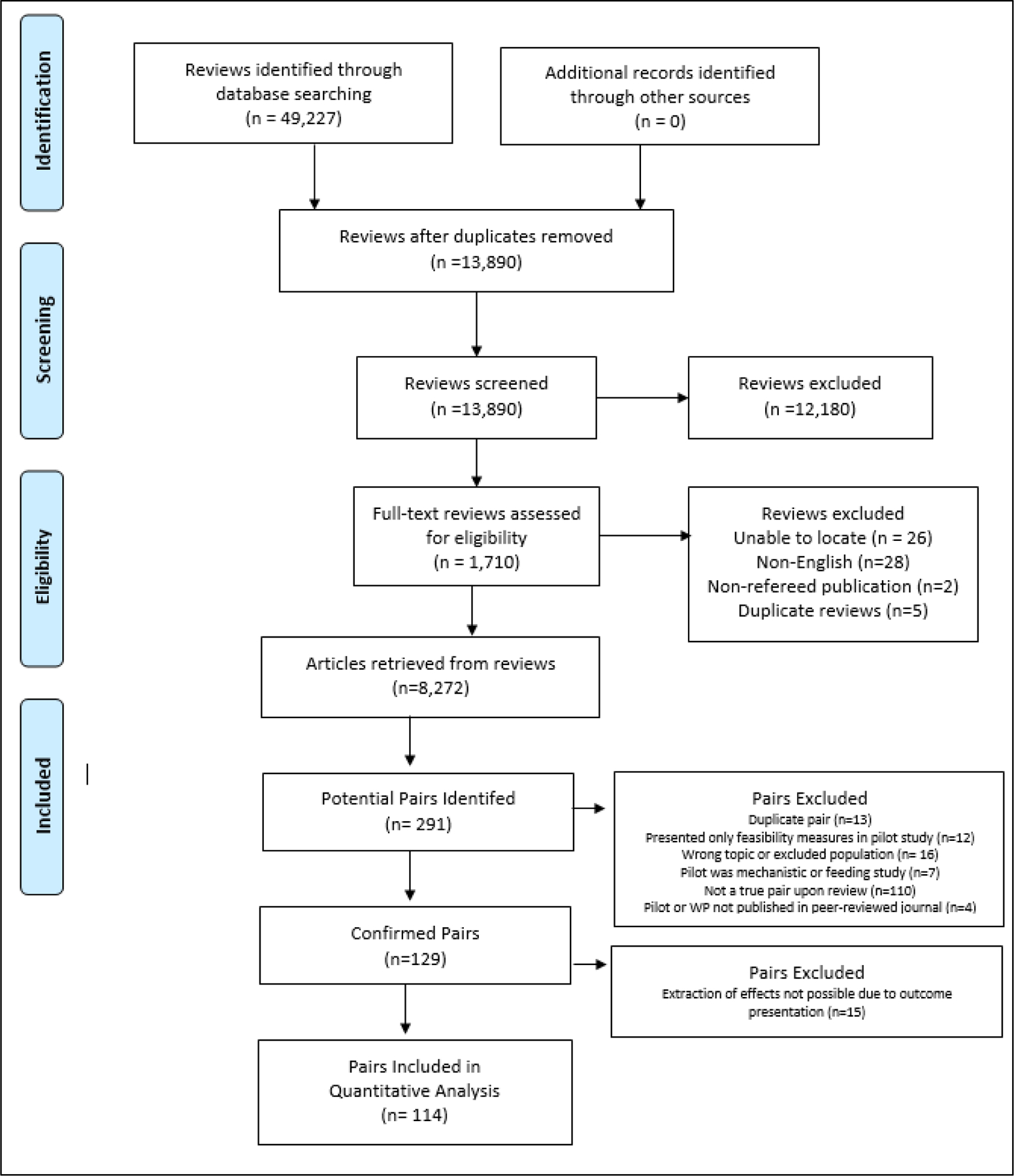

A PRISMA diagram for the literature search is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram of systematic literature search and final studies included in analyses.

From the 114 pairs, a total of 1,160 effects were extracted from the pilot studies (average 20 [SD±14] effects per study) and 1,089 effects extracted from the larger-scale trials (average 16 [SD±9] effects per trial). Studies were published between 1993 through 2020. Overall, the most commonly reported outcomes were body composition (54% of studies), physiological (51%), physical activity (50%), and psychosocial (29%), and diet (22%). The median sample size of the pilot studies was 44 (range 8 to 770, average 74) while the median sample size of the larger-scale trials was 201 (range 45 to 5801, average 361). A total of 71% of the pilot studies utilized a randomized design while 92% of the larger-scale trials utilized this design with the remaining 8% using either a single group pre/post design or two group non-randomized design.

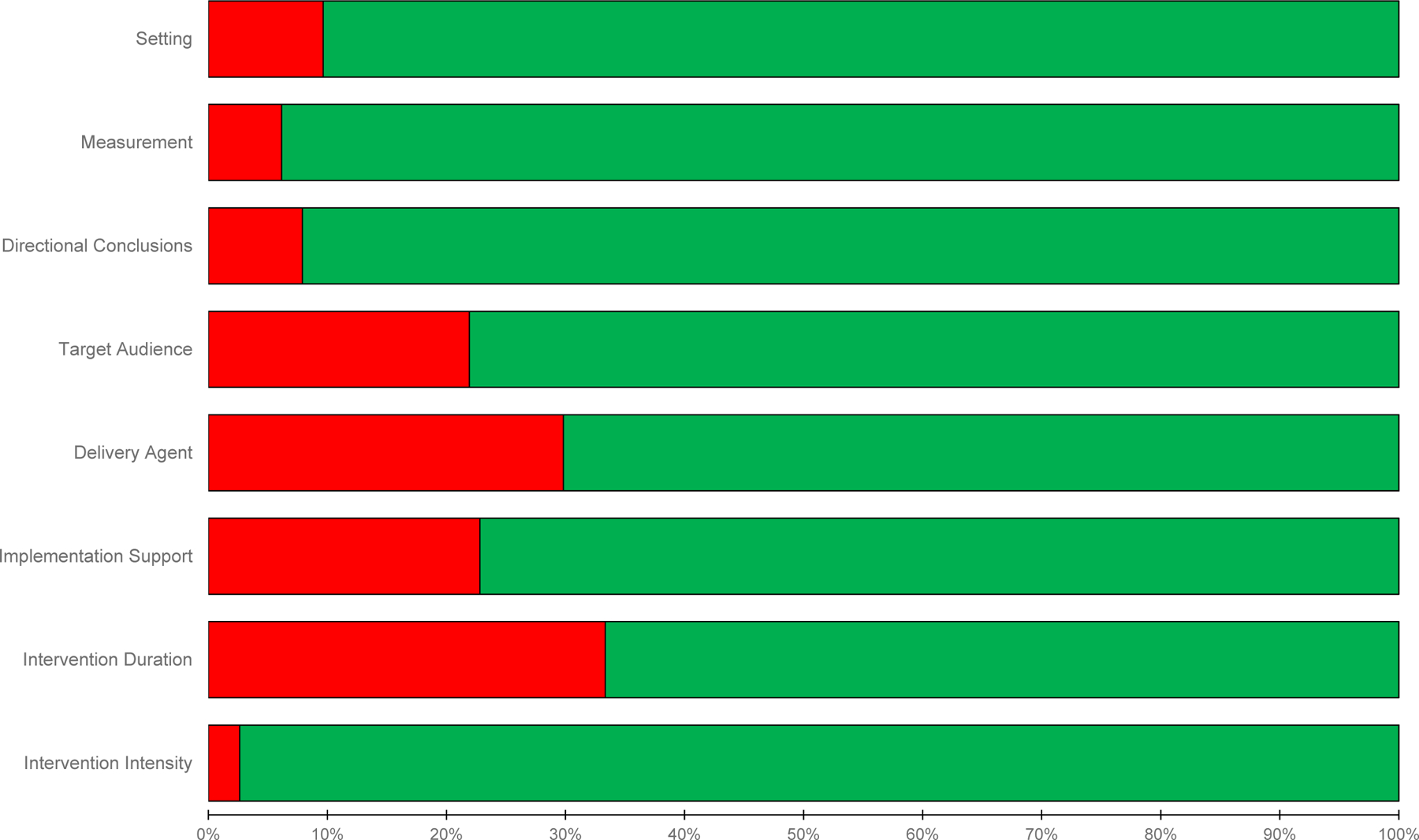

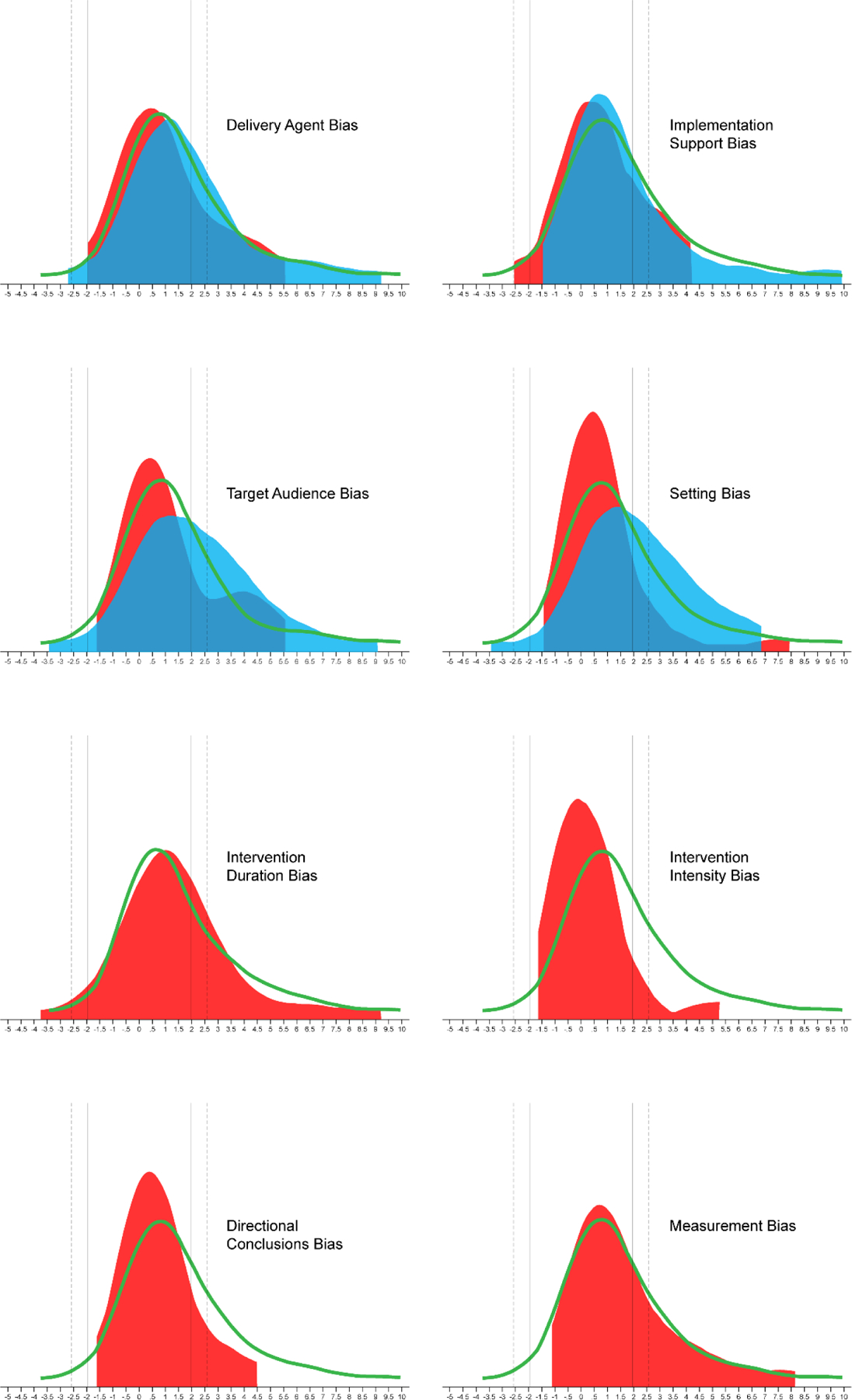

The prevalence of the RGBs across the 114 pairs is reported in Figure 3. Overall, 25% of the pairs were coded as no presence of any biases, 30% containing 1 bias, 33% containing 2 biases, and 12% with 3 or 4 biases. The four most prevalent RGBs were duration (33%), delivery agent (30%), implementation support (23%), and target audience (22%) bias.

Figure 3.

Classification of the presence (red) and absence (green) risk of generalizability biases across pilot and larger scale trial pairs

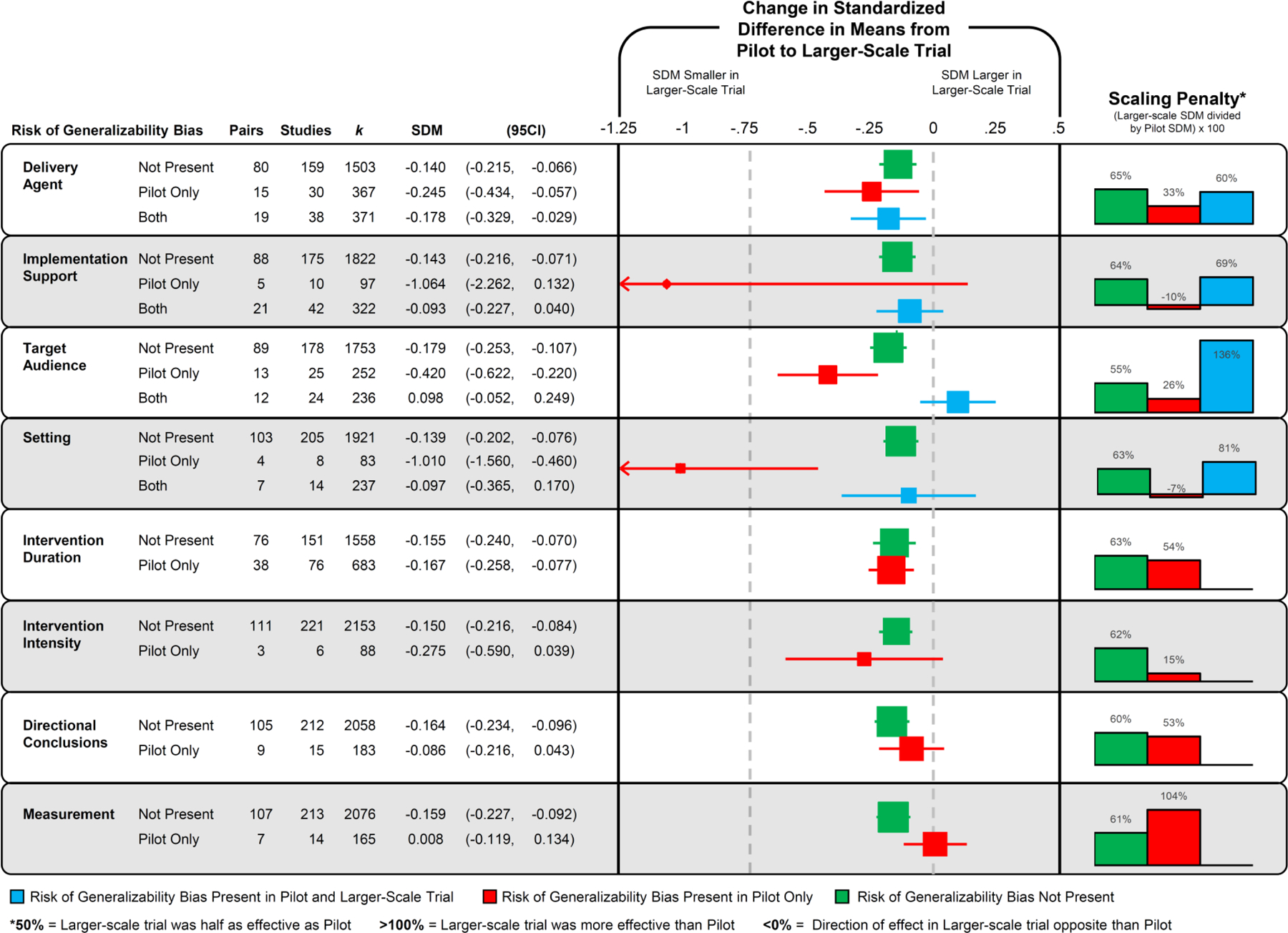

The impact of the RGBs on trial-related outcomes are presented in Figure 4. For pairs where the pilot was coded as having an RGB present and in the larger-scale trial the RGB was no longer present, the SDM decreased by an average of ΔSDM −0.41, range −1.06 to 0.01. The largest reductions in the SDM were observed for implementation support (pairs = 5, ΔSDM −1.06, 95CI −2.26 to 0.132) and setting (pairs = 4, ΔSDM −1.01, 95CI −1.56 to −0.46), followed by target audience (pairs = 13, ΔSDM −0.42, 95CI −0.62 to −0.22), intervention intensity (pairs = 3, ΔSDM −0.28, 95CI −0.59 to 0.04), and delivery agent (pairs = 15, ΔSDM −0.25, 95CI −0.43 to −0.06) biases in comparison to pairs where these biases were not coded as present in the pilot or larger-scale trial.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the change in the standardized difference in means (SDM) of the presence, absence, or carry forward of risk of generalizability biases from a pilot/feasibility study to a larger-scale trial. No pairs contained directional conclusion bias in both the pilot and larger-scale trial. Intervention duration, intervention intensity, and measurement describe differences between smaller and larger-scale studies so they can not be present in both studies.

Four of the RGBs were coded as present in the pilot and larger-scale trial: delivery agent (pairs = 19), implementation support (pairs = 21), target audience (pairs = 12), and setting (pairs = 7). Three of these four biases were associated with a smaller reduction in the SDM in comparison to pairs without the biases present. Implementation support and setting biases were associated with a reduction of −0.09 (−0.23 to 0.04) and −0.10 (−0.37 to 0.17), respectively, whereas target audience bias was associated with an increased effect in the larger-scale trial (+0.10, −0.05 to 0.25). The presence of intervention duration, directional conclusions, and measurement biases were not associated with a larger reduction in the SDM compared to pairs without these biases present.

The scale-up penalty associated with the RGBs are presented in Figure 4. Overall, on average pairs with biases present in the pilot and removed in the larger-scale trial’s effects were 33% (range −10% to 104%) of those reported in the pilot/feasibility study. This is compared to 63% (range 55% to 65%) for pairs without biases in either the pilot or larger-scale trial. Further, for pairs where a bias was present in both the pilot and larger-scale trial, the larger-scale trial effect was 86% (range 60% to 136%) of the effect observed in the pilot/feasibility study.

The impact of the RGBs on the probability of a statistically significant outcome are presented in Table 2 and the distribution of the z-value presented in Figure 5. Pairs coded as having either delivery agent, setting, intervention intensity, or directional conclusions biases in the pilot study and not in the larger-scale trial exhibited a reduced odds of detecting a nominally statistically significant effect of P<.05 in the larger-scale trials compared to pairs without an RGB present. Two (target audience and setting biases) of the four RGBs that were coded as present in the pilot and larger-scale trial, these larger-scale trials were more likely to report a nominally statistically significant effect of P<.05 in comparison to pairs without the RGB present. For detecting a statistical effect at P<.005, pairs coded as having either delivery agent, setting, duration, or intensity bias in the pilot study and not in the larger-scale trial exhibited a reduced odds of detecting a nominally statistically significant effect of P<.005 in the larger-scale trials compared to pairs without an RGB present. Consistent with the analyses for P<.05, two (target audience and setting biases) of the four RGBs that were coded as present in the pilot and larger-scale trial, these larger-scale trials were more likely to report a statistically significant effect of P<.005 in comparison to pairs without the RGB present.

Table 2.

Odds for detecting a nominally statistically significant p-value (P<.05 and P<.005) in a larger-scale trial from the presence of a risk of generalizability bias. Reference group is pilot/feasibility study and larger-scale trial pairs without a risk of generalizability bias present.

| Odds Ratio for P<.05 in Larger-scale Trial |

Odds Ratio for P<.005 in Larger-scale Trial |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of Generalizability Bias | OR | (95CI) | % Effects | OR | (95CI) | % Effects | |

| Delivery Agent | Not Present | Reference | 34% | Reference | 23% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.62 | (0.43, 0.90) | 24% | 0.60 | (0.39, 0.93) | 15% | |

| Both | 1.39 | (0.97, 2.00) | 42% | 0.96 | (0.63, 1.47) | 22% | |

|

| |||||||

| Implementation Support | Not Present | Reference | 34% | Reference | 22% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.81 | (0.42, 1.56) | 30% | 0.54 | (0.22, 1.30) | 13% | |

| Both | 0.74 | (0.51, 1.08) | 30% | 1.03 | (0.67, 1.57) | 22% | |

|

| |||||||

| Target Audience | Not Present | Reference | 32% | Reference | 20% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.72 | (0.47, 1.11) | 26% | 1.11 | (0.70, 1.75) | 21% | |

| Both | 2.05 | (1.35, 3.12) | 49% | 2.51 | (1.58, 3.98) | 34% | |

|

| |||||||

| Setting | Not Present | Reference | 33% | Reference | 21% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.17 | (0.06, 0.47) | 8% | 0.22 | (0.07, 0.70) | 6% | |

| Both | 2.01 | (1.29, 3.14) | 48% | 2.49 | (1.54, 4.03) | 35% | |

|

| |||||||

| Intervention Duration | Not Present | Reference | 34% | Reference | 23% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.83 | (0.61, 1.12) | 32% | 0.60 | (0.42, 0.84) | 17% | |

|

| |||||||

| Intervention Intensity | Not Present | Reference | 34% | Reference | 22% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.06 | (0.01, 0.46) | 3% | 0.12 | (0.02, 0.90) | 3% | |

|

| |||||||

| Measurement | Not Present | Reference | 35% | Reference | 22% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.86 | (0.52, 1.41) | 15% | 0.93 | (0.52, 1.65) | 20% | |

|

| |||||||

| Directional Conclusions | Not Present | Reference | 34% | Reference | 23% | ||

| Pilot Only | 0.27 | (0.13, 0.52) | 32% | 0.25 | (0.10, 0.60) | 8% | |

Note: Bolded values 95CIs do not cross 1.00

Figure 5.

Z-value distribution of outcomes in larger-scale trials by the absence (GREEN line) of risk of generalizability bias (RGB), RGB present in pilot and absent in larger-scale trial (RED distribution), and RGB present in both pilot and larger-scale trial (BLUE distribution). Note: Positive z-values indicate the intervention was better than the control group and negative z-values indicate the control group was better than the intervention group. Solid vertical lines represent z ±1.96 (P=.05); Dashed vertical lines represent z ±2.58 (P=.005)

Discussion

Informative, early-stage pilot/feasibility studies may provide valuable information about whether an intervention is ready to be tested in a larger-scale trial. When early-stage studies include features that result in incorrect conclusions about an intervention’s viability, this can lead to premature scale-up and, ultimately, intervention failure when evaluated at scale. The purpose of this meta-epidemiological review was to examine the influence of a set of recently catalogued biases – the Risk of Generalizability Biases (RGBs) – that, when present in pilot/feasibility studies, can lead to reduced effectiveness in larger-scale trials. As in a prior study focused on childhood obesity interventions 11, the presence of an RGB in a pilot/feasibility study tended to be associated with reduced effects in the larger-scale intervention and a reduced probability of detecting a nominally statistically significant effect. Further, the prevalence of the RGBs across the 114 pairs of published pilots and larger-scale trials of the same intervention was high, with 3 out of 4 pairs containing at least one RGB. The most impactful RGBs were delivery agent, implementation support, target audience, setting, and intervention intensity bias, although data were limited for each RGB to allow a reliable ranking of the magnitude of these biases. These findings on the prevalence and impact of RGBs on the effectiveness of larger-scale trials have implications for the behavioral intervention field because early-stage studies with RGBs appear to produce misleading results about the readiness of an intervention for scaling.

When moving from smaller, early-stage studies to trials to progressively larger sample sizes, it is not uncommon nor unexpected to see a drop in the respective impact (i.e., voltage) of an intervention 8–10. Our findings of reduced effects in the larger-scale trials compared to the effects from the pilot/feasibility studies match this pattern. This pattern, however, becomes accentuated when RGBs are considered. Pairs where an RGB was present in the pilot/feasibility study (i.e., delivery agent, implementation support, target audience, setting, intervention intensity) and not present in the larger-scale trial resulted in a greater scaling penalty, compared to pairs where an RGB was not present. Conversely, two of the four RGBs (setting and target audience) that could be carried forward (i.e. present in both the pilot/feasibility and larger-scale trial) showed less of a scaling penalty or demonstrated a greater effect in the larger-scale trial. These findings, both quantitatively and conceptually, fit the patterns expected with the presence of an RGB and provides evidence of their impact on the outcomes reported in larger-scale trials.

Comparing effect sizes generated from pilot/feasibility studies to their larger-scale trial is not without limitations, given the lower precision attributed with effect size estimations from pilot/feasibility studies 30–33. Thus, we recognize that effect sizes in pilot studies are estimated with large uncertainty, therefore putting too much trust on point estimates may be misleading. To address this, we conducted analyses considering only the larger-scale trial outcomes and the probability of detecting nominally statistically significant effects (P<.05 and P<.005). This approach eliminated the issues associated with using effects from the pilot/feasibility studies, instead relying solely upon those effects presented in the larger-scale trial. Again, findings demonstrated the presence of RGBs have an impact on the statistical significance in larger-scale trials. When larger-scale trials without an RGB, are informed by a pilot/feasibility study with an RGB, the large-scale study had a lower probability of detecting a nominally statistically significant effect compared to larger-scale trials without an RGB in either the pilot/feasibility study or larger-scale trial. An example of this is delivering an intervention in a university setting during the pilot/feasibility study vs. delivering the intervention in a community-based setting in the larger-scale trial (setting bias). A potential reduction in the odds of detecting a nominally statistically significant effect is observed across most of these comparisons and provides further support for the impact of RGBs on larger-scale trial outcomes, above and beyond any concern about comparing effect sizes between pilot/feasibility studies and larger-scale trials.

We recognize the list of RGBs evaluated herein may not fully capture the entirety of mechanisms that lead to successful or unsuccessful larger-scale trials. Recent studies 4,5,34–36 describe a number of mechanisms linked to either the successful scale-up of behavioral interventions or that should be considered in the conduct of early-stage implementation studies of behavioral interventions. These include mechanisms associated with the intervention (e.g., credibility, relevance, compatibility), organization (e.g., perceived need for intervention), environment (e.g., policy context, bureaucracy), resource team (e.g., effective leadership), scale up strategy (e.g., advocacy strategies), and planning/management (e.g., strategic monitoring). These are clearly critical mechanisms associated with developing a behavioral intervention that survives the scaling process. The current list of RGBs can have important implications and potential interactions with studies evaluating these scaling mechanisms. For instance, the risk of setting bias, target audience bias, delivery agent bias, and intervention duration bias have the potential to influence assessments related to whether an environment can support the intervention, an interventions’ adoption, adherence and dose received, and evaluations of whether the intervention is compatible and relevant. While the list of RGBs, at this time, is likely incomplete, we believe the current list identifies features of a study that transcend the content of the intervention and focus on features of how it is conducted that can lead to a lower likelihood of success in a larger-scale trial.

The introduction of one or more RGBs in pilot studies could be due to a lack of reporting and/or procedural guidelines for pilot studies that focus on topics related to RGBs. Recently, an extension to the CONSORT statement was developed for pilot/feasibility studies 37. This statement focuses predominately on features of the research design and conduct associated with internal validity and does not provide guidance for factors affiliated with external validity, such as the RGBs examined herein. Other reporting guidelines, for instance PRESCI-2 38,39 and TiDieR 14, incorporate elements of the RGBs and recommend they be detailed in scientific publications (e.g., clear description of who delivered the intervention) but do not provide a rationale for why interventionists may want to consider not introducing an RGB into their early-stage study. A lack of guidelines may stem from the limited evidence, to date, demonstrating the potential impact of the RGBs on early-stage studies and their larger-scale trial outcomes. Thus, the scientific field may be relatively unaware of the potential influence that the inclusion of RGBs in preliminary studies has on decisions related to scaling behavioral interventions.

Another potential reason for introducing RGBs is the need to demonstrate early success in a pilot study to receive funding for a larger-scale trial. Large-scale trials require strong preliminary data. Embedding RGBs into early-stage studies may provide a means to this end. A researcher may unwittingly or unintentionally introduce RGBs within preliminary studies to enhance perceived scientific credibility of the evidence to support a larger-scale trial. Given the hypercompetitive funding environment, producing strong preliminary data, which includes clearly demonstrating preliminary efficacy and promise of an intervention, may provide a logical rationale for testing an intervention at the early stages with one or more RGBs embedded within. Despite how justified and RGB introduction may be, our findings indicate that doing so has important ramifications for the outcomes of larger-scale trials. With larger-scale trials of interventions requiring some form of preliminary data, combined with the widespread introduction of RGBs within early pilot work, an environment is potentially created where awarding grants to support large-scale studies is high-risk, since the pilot/feasibility work no longer provides reliable evidence of an intervention’s likelihood of success.

Every occurrence of an RGB, however, is not inappropriate. On the contrary, RGBs within “first run” interventions can prove useful for refining intervention components. Investigators who deliver interventions themselves might gain insight about how participants react to content and whether changes are necessary. Employing RGBs may be necessary during the very early-stages of testing, but only if such studies lead to another pilot without RGBs present. The problem arises when “first run” interventions with RGBs go directly to a larger-scale trial, without conducting an intermediary trial that more closely mimics the conditions of the anticipated larger-scale trial. A sequence of studies that goes from a first run intervention to another, progressively larger, pilot/feasibility trial then onto a larger-scale more well-powered trial, may be ideal 1,2. Conducting multiple iterations of an intervention’s content, refining the content and then re-piloting could assist in identifying the correct ingredients for an intervention. This sequence implies funding is available to support a sequential, iterative process of intervention development, refinement, and testing.

The following are recommendations regarding the RGBs and early-stage preliminary studies. First, we suggest interventionists avoid introducing RGBs. Where RGBs are introduced this needs to be supported with rationale, such as first run interventions, and discussion whether their presence impacts outcomes. Existing guidelines (e.g., CONSORT) should include the Risk of Generalizability Biases in the required reporting of pilot/feasibility studies and their subsequent larger-scale trial. In published pilot/feasibility studies, details should be provided as to the anticipated conditions under which a larger-scale trial may be conducted and what changes, if any, to RGB-related items (e.g., who delivers the intervention, the length of the intervention, the setting where the intervention is conducted) may occur and how these may influence the larger-trial results. Finally, clear linkages should be made among studies used to inform a larger-scale trial. Pilot/feasibility studies need to be clearly identified and published and these should be clearly referred to in a subsequent larger-scale trial they informed.

There are several limitations in this study. First, while this study represents the largest pairing of pilot and large-scale trials to date, there are, undoubtedly, more pairs, which exist but were not captured due to our stringent inclusion criteria. We predicated our search strategy on the premise that larger-scale trials would reference published pilot studies if they existed. Thus, our search strategies likely resulted in a comprehensive list of pairings that could be made, albeit small in overall number compared to the number of larger-scale trials that exist. There are instances where a larger-scale trial was identified that did not explicitly reference prior pilot/feasibility studies, and there were instances where a pilot/feasibility study was identified but no larger-scale trial could be found. Second, the coding of the RGBs relied upon authors to clearly provide information upon which to judge their presence/absence. A recent study found only 12 of 200 RCTs provided sufficient information about who delivered the intervention 40. Other aspects of intervention reporting, such as the location of where the intervention occurred, are also poorly detailed in published RCTs. The ambiguousness or absence of this information makes identification of the RGBs difficult. The analyses conducted herein likely contain some studies that have an RGB but were coded as not having due to inadequate reporting of these important features. Hence, the impact of the RGBs could be greater or lesser, depending on the outcomes of studies that have unclear reporting. Third, not all of the RGBs demonstrated an impact. This is not entirely unexpected and could be due to the issues raised above or the reliance upon only 114 pairs. Uncertainty about the exact magnitude of the effects of RGBs is substantial. Finally, comparisons using pilot/feasibility effect sizes comes with issues of inaccurate and inflated effect sizes often observed in early-stage work. Exact replication of an effect from a pilot/feasibility study to a larger-scale trial is not the purpose of pilot/feasibility testing. Thus, analyses comparing reported effect sizes in pilot/feasibility study to those observed in the larger-scale trial are inherently limited. We agree effect sizes in pilot/feasibility studies can be imprecise and inflated and that they should not be used to inform power analyses of a larger-scale trial. Yet, it is common practice for meta-analyses to include pilot/feasibility studies in thereby giving scientific credibility to the effects they report. To address this, the analyses conducted herein include both a comparison the pilot/feasibility to larger-scale effect sizes as well as solely focusing on the effects reported in the larger-scale trials. These findings were consistent across these analyses demonstrating the impact RGBs have in trial outcomes. Fourth, even larger-scale trials may be biased or inaccurate for many other reasons not captured by RBGs, therefore their treatment effects should not be seen as an absolute gold standard.

In conclusion, the RGBs demonstrated moderate to strong support of their influence on the success of larger-scale trials. Consideration of the RGBs and how they can potentially misinform decisions about whether an intervention is ready for scale is critical given the time and resources required to conduct larger-scale trials. Future preliminary, early-stage work needs to consider whether the introduction of one or more RGBs is justifiable and if their presence will lead to incorrect decisions regarding the viability of an intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank all the authors of the published studies included in this review.

Funding:

Research reported in this abstract was supported by The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL149141 (Beets), F31HL158016 (von Klinggraeff), F32HL154530 (Burkart) as well as by the Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number P20GM130420 for the Research Center for Child Well-Being. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lubans is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship (APP1154507). Dr. Okely is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (APP1176858). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The work of John Ioannidis is supported by an unrestricted gift from Sue and Bob O’Donnell.

Abbreviations

- RGB

Risk of Generalizability Bias

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- CMA

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis

- ES

Effect size

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none to declare.

Additional Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate – Not Applicable

Availability of data and materials – The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the overall project is ongoing but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests - The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- 1.Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol 2015;34(10):971–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning Clinical Science: Unifying the Discipline to Improve the Public Health. Clin Psychol Sci 2014;2(1):22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Small R01s for Clinical Trials Targeting Diseases within the Mission of NIDDK (R01 Clinical Trial Required) National Institutes of Health. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/pas-20-160.html. Published 2020. Accessed April 1st, 2021.

- 4.Pearson N, Naylor PJ, Ashe MC, Fernandez M, Yoong SL, Wolfenden L. Guidance for conducting feasibility and pilot studies for implementation trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2020;6(1):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrabb S, Mooney K, Elton B, Grady A, Yoong SL, Wolfenden L. How to optimise public health interventions: a scoping review of guidance from optimisation process frameworks. BMC Public Health 2020;20(1):1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013;8:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med 2005;29 Suppl:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci 2007;2:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane C, McCrabb S, Nathan N, et al. How effective are physical activity interventions when they are scaled-up: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021;18(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCrabb S, Lane C, Hall A, et al. Scaling-up evidence-based obesity interventions: A systematic review assessing intervention adaptations and effectiveness and quantifying the scale-up penalty. Obes Rev 2019;20(7):964–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beets MW, Weaver RG, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Identification and evaluation of risk of generalizability biases in pilot versus efficacy/effectiveness trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020;17(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Cochrane Collaboration. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Handbook is 5.1 [updated March 2011] http://handbook.cochrane.org. Published 2011. Accessed.

- 13.de Bruin M, McCambridge J, Prins JM. Reducing the risk of bias in health behaviour change trials: improving trial design, reporting or bias assessment criteria? A review and case study. Psychol Health 2015;30(1):8–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Araújo-Soares V, Hankonen N, Presseau J, Rodrigues A, Sniehotta FF. Developing Behavior Change Interventions for Self-Management in Chronic Illness: An Integrative Overview. Eur Psychol 2019;24(1):7–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher E. Ecological models of health behavior. Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice 2015;5(43–64). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45(5):626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, Lancaster GA. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens J, Taber DR, Murray DM, Ward DS. Advances and controversies in the design of obesity prevention trials. Obesity 2007;15(9):2163–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, et al. Defining Feasibility and Pilot Studies in Preparation for Randomised Controlled Trials: Development of a Conceptual Framework. PLOS ONE 2016;11(3):e0150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puljak L, Makaric ZL, Buljan I, Pieper D. What is a meta-epidemiological study? Analysis of published literature indicated heterogeneous study designs and definitions. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 2020;9(7):497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol Methods 2002;7(1):105–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Db Syst Rev 2011(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical. [computer program] 2015.

- 25.Tipton E Small sample adjustments for robust variance estimation with meta-regression. Psychol Methods 2015;20(3):375–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konstantopoulos S Fixed effects and variance components estimation in three-level meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2011;2(1):61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viechtbauer W Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ioannidis JPA. The Proposal to Lower P Value Thresholds to .005. JAMA 2018;319(14):1429–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamin DJ, Berger JO, Johannesson M, et al. Redefine statistical significance. Nat Hum Behav 2018;2(1):6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freedland KE. Pilot trials in health-related behavioral intervention research: Problems, solutions, and recommendations. Health Psychol 2020;39(10):851–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10(2):307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45(5):626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. Bmc Med Res Methodol 2010;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milat AJ, King L, Bauman A, Redman S. Scaling up health promotion interventions: an emerging concept in implementation science. Health Promot J Austr 2011;22(3):238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, Redman S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int 2013;28(3):285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koorts H, Cassar S, Salmon J, Lawrence M, Salmon P, Dorling H. Mechanisms of scaling up: combining a realist perspective and systems analysis to understand successfully scaled interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021;18(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Loudon K. PRECIS-2 helps researchers design more applicable RCTs while CONSORT Extension for Pragmatic Trials helps knowledge users decide whether to apply them. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;84:27–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rauh SL, Turner D, Jellison S, et al. Completeness of Intervention Reporting of Clinical Trials Published in Highly Ranked Obesity Journals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021;29(2):285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References [Figure 3]

- 1.Vadheim LM, McPherson C, Kassner DR, et al. Adapted diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention can be effectively delivered through telehealth. Diabetes Educ Jul-Aug 2010;36(4):651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vadheim LM, Patch K, Brokaw SM, et al. Telehealth delivery of the diabetes prevention program to rural communities. Transl Behav Med Jun 2017;7(2):286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark AM, Ledger W, Galletly C, et al. Weight loss results in significant improvement in pregnancy and ovulation rates in anovulatory obese women. Hum Reprod Oct 1995;10(10):2705–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark AM, Thornley B, Tomlinson L, et al. Weight loss in obese infertile women results in improvement in reproductive outcome for all forms of fertility treatment. Hum Reprod Jun 1998;13(6):1502–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rock CL, Byers TE, Colditz GA, et al. Reducing breast cancer recurrence with weight loss, a vanguard trial: the Exercise and Nutrition to Enhance Recovery and Good Health for You (ENERGY) Trial. Contemp Clin Trials Mar 2013;34(2):282–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Byers TE, et al. Results of the Exercise and Nutrition to Enhance Recovery and Good Health for You (ENERGY) Trial: A Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention in Overweight or Obese Breast Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(28):3169–3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumanyika SK, Hebert PR, Cutler JA, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of sodium reduction in the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase I. Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Hypertension Oct 1993;22(4):502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumanyika SK, Cook NR, Cutler JA, et al. Sodium reduction for hypertension prevention in overweight adults: further results from the Trials of Hypertension Prevention Phase II. Journal of Human Hypertension 2005/01/01 2005;19(1):33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mau MK, Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula J, West MR, et al. Translating diabetes prevention into native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities: the PILI ‘Ohana Pilot project. Prog Community Health Partnersh Spring 2010;4(1):7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaholokula JK, Wilson RE, Townsend CK, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities: the PILI ‘Ohana Project. Transl Behav Med Jun 2014;4(2):149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pahor M, Blair SN, Espeland M, et al. Effects of a physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance: Results of the lifestyle interventions and independence for Elders Pilot (LIFE-P) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci Nov 2006;61(11):1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE study randomized clinical trial. Jama Jun 18 2014;311(23):2387–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray CM, Hunt K, Mutrie N, et al. Weight management for overweight and obese men delivered through professional football clubs: a pilot randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act Oct 30 2013;10:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt K, Wyke S, Gray CM, et al. A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2014;383(9924):1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann J, Zhou H, McDermott S, et al. Healthy behavior change of adults with mental retardation: attendance in a health promotion program. Am J Ment Retard Jan 2006;111(1):62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDermott S, Whitner W, Thomas-Koger M, et al. An efficacy trial of ‘Steps to Your Health’, a health promotion programme for adults with intellectual disability. Health Educ J 2012;71(3):278–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rock CL, Pakiz B, Flatt SW, et al. Randomized trial of a multifaceted commercial weight loss program. Obesity (Silver Spring) Apr 2007;15(4):939–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Sherwood NE, et al. Effect of a Free Prepared Meal and Incentivized Weight Loss Program on Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance in Obese and Overweight Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2010;304(16):1803–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Albright CL, et al. A pregnancy and postpartum lifestyle intervention in women with gestational diabetes mellitus reduces diabetes risk factors: a feasibility randomized control trial. Diabetes Care Jul 2011;34(7):1519–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Brown SD, et al. The Comparative Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention Strategies to Reduce Postpartum Weight Retention in Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care Jan 2016;39(1):65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Blok BM, de Greef MH, ten Hacken NH, et al. The effects of a lifestyle physical activity counseling program with feedback of a pedometer during pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns Apr 2006;61(1):48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altenburg WA, ten Hacken NH, Bossenbroek L, et al. Short- and long-term effects of a physical activity counselling programme in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Med Jan 2015;109(1):112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoellner J, Connell CL, Santell R, et al. Fit for life steps: results of a community walking intervention in the rural Mississippi delta. Prog Community Health Partnersh Spring 2007;1(1):49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zoellner J, Connell C, Madson MB, et al. HUB city steps: a 6-month lifestyle intervention improves blood pressure among a primarily African-American community. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114(4):603–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hare JP, Raymond NT, Mughal S, et al. Evaluation of delivery of enhanced diabetes care to patients of South Asian ethnicity: the United Kingdom Asian Diabetes Study (UKADS). Diabet Med Dec 2004;21(12):1357–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellary S, O’Hare JP, Raymond NT, et al. Enhanced diabetes care to patients of south Asian ethnic origin (the United Kingdom Asian Diabetes Study): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet May 24 2008;371(9626):1769–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke V, Giangiulio N, Gillam HF, et al. Health promotion in couples adapting to a shared lifestyle. Health Education Research 1999;14(2):269–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burke V, Giangiulio N, Gillam HF, et al. Physical activity and nutrition programs for couples: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2003/05/01/ 2003;56(5):421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell A, Mutrie N, White F, et al. A pilot study of a supervised group exercise programme as a rehabilitation treatment for women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs Mar 2005;9(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Whyte F, et al. Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for early stage breast cancer: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;334(7592):517–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, et al. Mindfulness Intervention for Stress Eating to Reduce Cortisol and Abdominal Fat among Overweight and Obese Women: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Study. J Obes 2011;2011:651936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daubenmier J, Moran PJ, Kristeller J, et al. Effects of a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention in adults with obesity: A randomized clinical trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) Apr 2016;24(4):794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plaete J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Verloigne M, et al. Acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of an eHealth behaviour intervention using self-regulation: ‘MyPlan’. Patient Educ Couns Jul 26 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Dyck D, Plaete J, Cardon G, et al. Effectiveness of the self-regulation eHealth intervention ‘MyPlan1.0.’ on physical activity levels of recently retired Belgian adults: a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res Oct 2016;31(5):653–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med Jul 4 2006;145(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babio N, Toledo E, Estruch R, et al. Mediterranean diets and metabolic syndrome status in the PREDIMED randomized trial. Cmaj Nov 18 2014;186(17):E649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parikh P, Simon EP, Fei K, et al. Results of a pilot diabetes prevention intervention in East Harlem, New York City: Project HEED. Am J Public Health Apr 1 2010;100 Suppl 1:S232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayer VL, Vangeepuram N, Fei K, et al. Outcomes of a Weight Loss Intervention to Prevent Diabetes Among Low-Income Residents of East Harlem, New York. Health Education & Behavior 2019/12/01 2019;46(6):1073–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathey MF, Vanneste VG, de Graaf C, et al. Health effect of improved meal ambiance in a Dutch nursing home: a 1-year intervention study. Prev Med May 2001;32(5):416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nijs KA, de Graaf C, Kok FJ, et al. Effect of family style mealtimes on quality of life, physical performance, and body weight of nursing home residents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ May 20 2006;332(7551):1180–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goessens BMB, Visseren FLJ, de Nooijer J, et al. A pilot-study to identify the feasibility of an Internet-based coaching programme for changing the vascular risk profile of high-risk patients. Patient Education and Counseling 2008/10/01/ 2008;73(1):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vernooij JWP, Kaasjager HAH, van der Graaf Y, et al. Internet based vascular risk factor management for patients with clinically manifest vascular disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ : British Medical Journal 2012;344:e3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erkkilä AT, Schwab US, Lehto S, et al. Effect of fatty and lean fish intake on lipoprotein subclasses in subjects with coronary heart disease: a controlled trial. J Clin Lipidol Jan-Feb 2014;8(1):126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lankinen M, Kolehmainen M, Jääskeläinen T, et al. Effects of Whole Grain, Fish and Bilberries on Serum Metabolic Profile and Lipid Transfer Protein Activities: A Randomized Trial (Sysdimet). PLOS ONE 2014;9(2):e90352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ligibel JA, Partridge A, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Physical and psychological outcomes among women in a telephone-based exercise intervention during adjuvant therapy for early stage breast cancer. J Womens Health (Larchmt) Aug 2010;19(8):1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ligibel JA, Giobbie-Hurder A, Shockro L, et al. Randomized trial of a physical activity intervention in women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Apr 15 2016;122(8):1169–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi MCE, Nicolucci A, Di Bartolo P, et al. Diabetes Interactive Diary: A New Telemedicine System Enabling Flexible Diet and Insulin Therapy While Improving Quality of Life. Diabetes Care 2010;33(1):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Lucisano G, et al. Impact of the “Diabetes Interactive Diary” telemedicine system on metabolic control, risk of hypoglycemia, and quality of life: a randomized clinical trial in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther Aug 2013;15(8):670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sacco WP, Morrison AD, Malone JI. A brief, regular, proactive telephone “coaching” intervention for diabetes: rationale, description, and preliminary results. J Diabetes Complications Mar-Apr 2004;18(2):113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sacco WP, Malone JI, Morrison AD, et al. Effect of a brief, regular telephone intervention by paraprofessionals for type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med Aug 2009;32(4):349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zutz A, Ignaszewski A, Bates J, et al. Utilization of the internet to deliver cardiac rehabilitation at a distance: a pilot study. Telemed J E Health Jun 2007;13(3):323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lear SA, Singer J, Banner-Lukaris D, et al. Randomized trial of a virtual cardiac rehabilitation program delivered at a distance via the Internet. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes Nov 2014;7(6):952–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernocchi P, Baratti D, Zanelli E, et al. Six-month programme on lifestyle changes in primary cardiovascular prevention: a telemedicine pilot study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation 2011/06/01 2011;18(3):481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernocchi P, Scalvini S, Bertacchini F, et al. Home based telemedicine intervention for patients with uncontrolled hypertension: - a real life - non-randomized study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2014/06/12 2014;14(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu J, Wallace DC, McCoy TP, et al. A family-based diabetes intervention for Hispanic adults and their family members. Diabetes Educ Jan-Feb 2014;40(1):48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu J, Amirehsani KA, Wallace DC, et al. A Family-Based, Culturally Tailored Diabetes Intervention for Hispanics and Their Family Members. Diabetes Educ Jun 2016;42(3):299–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friederichs S, Bolman C, Oenema A, et al. Motivational interviewing in a Web-based physical activity intervention with an avatar: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2014;16(2):e48–e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friederichs SAH, Oenema A, Bolman C, et al. Long term effects of self-determination theory and motivational interviewing in a web-based physical activity intervention: randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2015/08/18 2015;12(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brindal E, Hendrie G, Freyne J, et al. Design and pilot results of a mobile phone weight-loss application for women starting a meal replacement programme. J Telemed Telecare Apr 2013;19(3):166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brindal E, Hendrie GA, Freyne J, et al. Incorporating a Static Versus Supportive Mobile Phone App Into a Partial Meal Replacement Program With Face-to-Face Support: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth Apr 18 2018;6(4):e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim MT, Han HR, Song HJ, et al. A community-based, culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ Nov-Dec 2009;35(6):986–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim MT, Kim KB, Huh B, et al. The Effect of a Community-Based Self-Help Intervention: Korean Americans With Type 2 Diabetes. Am J Prev Med Nov 2015;49(5):726–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim KH, Linnan L, Campbell MK, et al. The WORD (wholeness, oneness, righteousness, deliverance): a faith-based weight-loss program utilizing a community-based participatory research approach. Health Educ Behav Oct 2008;35(5):634–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yeary KH-cK, Cornell CE, Turner J, et al. Feasibility of an evidence-based weight loss intervention for a faith-based, rural, African American population. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8(6):A146–A146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subak LL, Whitcomb E, Shen H, et al. Weight loss: a novel and effective treatment for urinary incontinence. J Urol Jul 2005;174(1):190–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosal MC, Olendzki B, Reed GW, et al. Diabetes self-management among low-income Spanish-speaking patients: a pilot study. Ann Behav Med Jun 2005;29(3):225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ockene IS, Tellez TL, Rosal MC, et al. Outcomes of a Latino community-based intervention for the prevention of diabetes: the Lawrence Latino Diabetes Prevention Project. American journal of public health 2012;102(2):336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, et al. A text message-based intervention for weight loss: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res Jan 13 2009;11(1):e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shapiro JR, Koro T, Doran N, et al. Text4Diet: a randomized controlled study using text messaging for weight loss behaviors. Prev Med Nov 2012;55(5):412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Godino JG, Golaszewski NM, Norman GJ, et al. Text messaging and brief phone calls for weight loss in overweight and obese English- and Spanish-speaking adults: A 1-year, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2019;16(9):e1002917–e1002917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med Oct 2008;35(4):357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ackermann RT, Liss DT, Finch EA, et al. A Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial for Preventing Type 2 Diabetes. Am J Public Health Nov 2015;105(11):2328–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nanchahal K, Townsend J, Letley L, et al. Weight-management interventions in primary care: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract May 2009;59(562):e157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nanchahal K, Power T, Holdsworth E, et al. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial in primary care of the Camden Weight Loss (CAMWEL) programme. BMJ Open 2012;2(3):e000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Rogers MA, et al. A primary care intervention for weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. Obesity (Silver Spring) Aug 2010;18(8):1614–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumanyika SK, Fassbender JE, Sarwer DB, et al. One-year results of the Think Health! study of weight management in primary care practices. Obesity (Silver Spring) Jun 2012;20(6):1249–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A Two-Year Randomized Trial of Obesity Treatment in Primary Care Practice. New England Journal of Medicine 2011/11/24 2011;365(21):1969–1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Armit CM, Brown WJ, Ritchie CB, et al. Promoting physical activity to older adults: a preliminary evaluation of three general practice-based strategies. J Sci Med Sport Dec 2005;8(4):446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Armit CM, Brown WJ, Marshall AL, et al. Randomized trial of three strategies to promote physical activity in general practice. Prev Med Feb 2009;48(2):156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Citters AD, Pratt SI, Jue K, et al. A pilot evaluation of the In SHAPE individualized health promotion intervention for adults with mental illness. Community Ment Health J Dec 2010;46(6):540–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, et al. Clinically significant improved fitness and weight loss among overweight persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv Aug 1 2013;64(8):729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kegler MC, Alcantara I, Veluswamy JK, et al. Results from an intervention to improve rural home food and physical activity environments. Prog Community Health Partnersh Fall 2012;6(3):265–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kegler MC, Haardörfer R, Alcantara IC, et al. Impact of Improving Home Environments on Energy Intake and Physical Activity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Public Health Jan 2016;106(1):143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saunders RR, Saunders MD, Donnelly JE, et al. Evaluation of an Approach to Weight Loss in Adults With Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 2011;49(2):103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ptomey LT, Saunders RR, Saunders M, et al. Weight management in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A randomized controlled trial of two dietary approaches. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil Jan 2018;31 Suppl 1:82–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaw RJ, Bosworth HB, Hess JC, et al. Development of a Theoretically Driven mHealth Text Messaging Application for Sustaining Recent Weight Loss. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2013;1(1):e5–e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shaw RJ, Bosworth HB, Silva SS, et al. Mobile health messages help sustain recent weight loss. Am J Med Nov 2013;126(11):1002–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Poston L, Briley AL, Barr S, et al. Developing a complex intervention for diet and activity behaviour change in obese pregnant women (the UPBEAT trial); assessment of behavioural change and process evaluation in a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth Jul 15 2013;13:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poston L, Bell R, Croker H, et al. Effect of a behavioural intervention in obese pregnant women (the UPBEAT study): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol Oct 2015;3(10):767–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gilson N, McKenna J, Cooke C, et al. Walking towards health in a university community: a feasibility study. Prev Med Feb 2007;44(2):167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gilson ND, Faulkner G, Murphy MH, et al. Walk@Work: An automated intervention to increase walking in university employees not achieving 10,000 daily steps. Prev Med May 2013;56(5):283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee AH, Jancey J, Howat P, et al. Effectiveness of a Home-Based Postal and Telephone Physical Activity and Nutrition Pilot Program for Seniors. Journal of Obesity 2010/08/10 2011;2011:786827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burke L, Jancey JM, Howat P, et al. Physical Activity and Nutrition Program for Seniors (PANS): process evaluation. Health Promot Pract Jul 2013;14(4):543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Vries NM, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, et al. The Coach2Move Approach: Development and Acceptability of an Individually Tailored Physical Therapy Strategy to Increase Activity Levels in Older Adults With Mobility Problems. J Geriatr Phys Ther Oct-Dec 2015;38(4):169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]