Abstract

The degree of metastatic disease varies widely amongst cancer patients and impacts clinical outcomes. However, the biological and functional differences that drive the extent of metastasis are poorly understood. We analyzed primary tumors and paired metastases using a multi-fluorescent lineage-labeled mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) – a tumor type where most patients present with metastases. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis revealed an association between metastatic burden and gene amplification or transcriptional upregulation of MYC and its downstream targets. Functional experiments showed that MYC promotes metastasis by recruiting tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), leading to greater bloodstream intravasation. Consistent with these findings, metastatic progression in human PDAC was associated with activation of MYC signaling pathways and enrichment for MYC amplifications specifically in metastatic patients. Collectively, these results implicate MYC activity as a major determinant of metastatic burden in advanced PDAC.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Metastasis, Myc, Invasion, Copy Number Alterations, Tumor heterogeneity, Tumor associated macrophages, Tumor immune micorenvironment

Introduction

Tumor heterogeneity, most commonly studied in a primary disease setting, is a critical driver of phenotypic diversity, culminating in metastatic, lethal cancers (1–5). In most cancers, prognosis and therapeutic decisions are defined by the presence or absence of metastasis. However, tumor heterogeneity is increasingly being questioned at the level of metastatic disease, with recent studies in several cancer types suggesting that metastasis is not a binary phenotype but rather a disease spectrum ranging from oligo- (limited) to polymetastatic (widespread) disesase (6–8). Heterogeneity in the manifestation of metastatic disease can guide decisions on use of local regional vs. systemic therapies with emerging evidence of its importance in clinical outcome (9–11). Despite its clinical significance, the mechanisms that underlie this spectrum of metastatic states remains unclear and largely understudied.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) represents a disease entity well suited for the study of metastasis, as most PDACs present with metastatic disease that is associated with dismal prognosis (12). Genomic studies have comprehensively catalogued core mutations responsible for primary tumor development in PDAC (e.g. KRAS, TRP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4), paving the path for genomic investigations of metastatic disease and the identification of metastasis-promoting alterations. Indeed, recent sequencing studies as well as functional analysis in model systems have associated genomic amplification in mutant KRAS alleles with progression from non-metastatic (stage III) to metastatic disease (stage IV) state (13). However, genetic factors mediating metastasic heterogeneity in patients and, importantly, the downstream cellular mechanisms, remain largely undefined (14–18). Furthermore, it is unclear whether metastasis-associated alterations perturb the tumor microenvironment (TME), whose influence on metastatic behavior is well-documented (19–31). Therefore, understanding the interplay between genetic alterations that influence metastatic behavior and the tumor biology that promotes it – via cell autonomous and/or non-cell autonomous mechanisms – is crucial for understanding metastasis as a distinct disease state and critical for the development of more effective treatments.

One barrier to understanding metastatic heterogeneity has been a paucity of model systems that capture this natural variation and allow for direct assessments of paired primary tumors and metastases in vivo. This has limited the ability to define factors intrinsic to primary tumors that influence the extent of metastatic spread. We previously developed an autochthonous model of PDAC – the KPCX model – that employs multiplexed fluorescence-based labeling to track the simultaneous development of multiple primary tumor cell lineages and follow them as they metastasize (32). Importantly, this technique facilitates confirmation of lineage relationships in vivo, such that primary tumor clones with substantial metastatic potential can be distinguished from those having poor metastatic potential. Here, we show that this system recapitulates the variation in metastatic burden found in human PDAC, and we use it to dissect molecular and cellular features contributing to metastatic heterogeneity.

Results

Metastatic burden is variable in human and murine PDAC

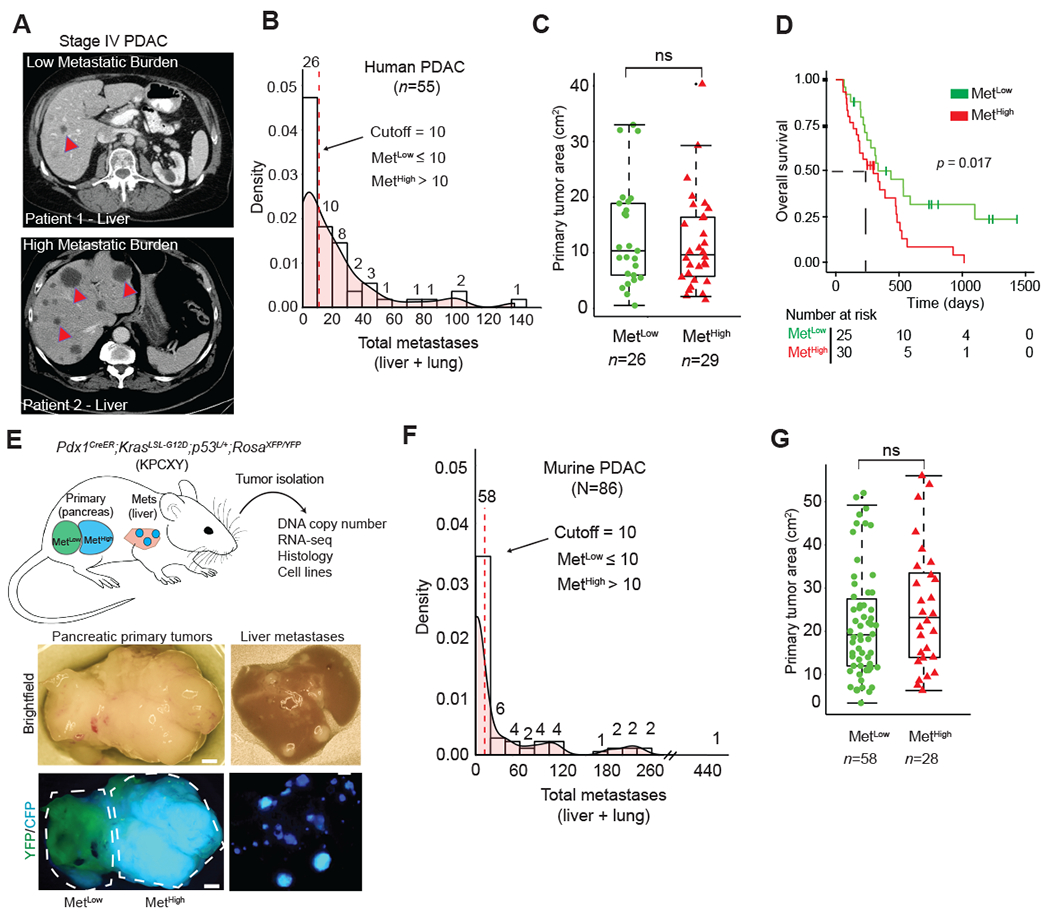

While the vast majority of PDAC patients have metastases (principally liver and lung), the number of metastases is highly variable from patient to patient (33,34). Importantly, data regarding metastases have largely been obtained at autopsy and thus confounded by varying treatment histories and reseeding due to end-stage disease (4). Thus, we first sought to characterize the burden of metastases in treatment-naïve patients. To this end, we performed a retrospective analysis of initial CT scans from 55 patients newly diagnosed with metastatic (stage IV) PDAC (Fig. 1A). The total number of lesions in the lung and liver were counted by examining both coronal and sagittal planes for both organs and binned into groups of ten, revealing a wide distribution of metastatic burden (Fig. 1B). K-means clustering identified two metastatic subgroups: a Metlow subgroup (≤10 metastases, 25/55) and a Methigh subgroup (>10 metastases, 30/55) (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. S1A). Primary tumor size, age, sex, and race were not correlated with differences in metastatic burden (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Fig. S1B). However, having a greater number of metastases was associated with worse overall survival (Fig. 1D). Thus, even among patients with stage IV PDAC, metastatic burden is variable and correlates with clinical outcome.

Figure 1: Advanced pancreatic tumors exhibit intertumoral differences in their propensity for metastasis.

A. CT imaging of human PDAC liver metastasis demonstrating heterogeneity in metastatic burden in Stage IV disease. Arrowheads indicate solitary metastasis in the top panel and selected metastases in the bottom panel

B. Density plot and histogram showing the distribution of total (liver and lung) metastases enumerated from CT scans of human Stage IV PDAC at the time of diagnosis (n=55). Values above each histogram bar represent the number of patients in each group. The vertical dotted line (red) represents the cutoff between MetLow tumors (≤ 10 mets) and MetHigh tumors (>10 mets) determined by k-means clustering.

C. Quantification of tumor area (based on tumor dimensions from largest cross-sectional plane on imaging) comparing MetLow and MetHigh cases from the cohort in (b).

D. Overall survival analysis of the cohort in (B).

E. Top: Schematic view of the KPCXY model, showing multiple primary tumors distinguishable by color arising in the pancreas with matched metastases in the liver. Bottom: Representative fluorescent stereomicroscopic images showing a YFP+ tumor adjoining a CFP+ tumor in the pancreas (left) and liver metastases derived from the CFP+ tumor in the same animal (right).

F. Density plot and histogram showing the distribution of total (liver and lung) metastases enumerated at autopsy of KPCXY mice. Values above each histogram bar represent the number of tumors giving rise to the indicated number of metastases, based on color (n=85 tumors from 30 KPCXY mice). The vertical dotted line (red) represents the cutoff between MetLow tumors (≤ 10 mets, n=58) and MetHigh tumors (>10 mets, n=28) determined by k-means clustering.

G. Quantification of tumor area comparing MetLow and MetHigh tumors from the cohort in (F).

Statistical analysis by Student’s unpaired t-test with p-values indicated (ns, not significant). Box-whisker plots in (C) and (F) indicate mean and interquartile range. Scale bar (E) = 1mm.

We hypothesized that the differences in metastatic burden seen in human PDAC may also be present in autochthonous murine models. To test this, we used the KPCXY model – in which Cre-mediated recombination triggers expression of mutant KrasG12D and deletion of one allele of Trp53 in the pancreatic epithelium along with YFP and confetti (X) lineage tracers (Fig. 1E, Methods) – to measure metastatic heterogeneity in a cohort of tumor bearing mice. By exploiting the multi-color features of the KPCX model, we previously showed that these mice harbor (on average) 2-5 independent primary tumor clones; importantly, the clonal marking of tumors with different fluorophores makes it possible to infer the lineages of primary tumors with different metastatic potential (32). In our earlier work with this model, we noted that in most tumor-bearing animals – even those with multiple primary tumors – liver and lung metastases were driven by a single tumor clone (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Fig. S1C). This suggested that tumor cell-intrinsic factors strongly influence the metastatic behavior of a tumor, even within a single animal.

To quantify differences in metastatic burden, we examined a panel of mice with at least 2 uniquely labeled fluorescent tumors where most metastases could be attributed to a specific tumor on the basis of color (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Fig. S1C). A total of 85 primary tumors from 30 mice were examined, and gross metastases to the liver and lung arising from each tumor were then quantified by stereomicroscopy (Methods). Murine PDACs exhibited a wide distribution of metastatic burden, with a pattern resembling that of the human disease (Fig. 1F). Similarly, K-means clustering grouped murine samples into a low metastasis subgroup (≤10 metastases, 58/85) and a high metastasis subgroup (>10 metastases, 27/85), which we similarly refer to as MetLow and MetHigh, respectively (Fig. 1F, Supplementary Fig. S1D). As with the human disease, neither primary tumor size nor tumor cell proliferation correlated with metastatic burden (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Fig. S1E). Thus, the KPCXY model recapitulates the intertumoral metastatic heterogeneity seen in human PDAC and provides a unique experimental model for comparing highly metastatic and poorly metastatic tumor clones.

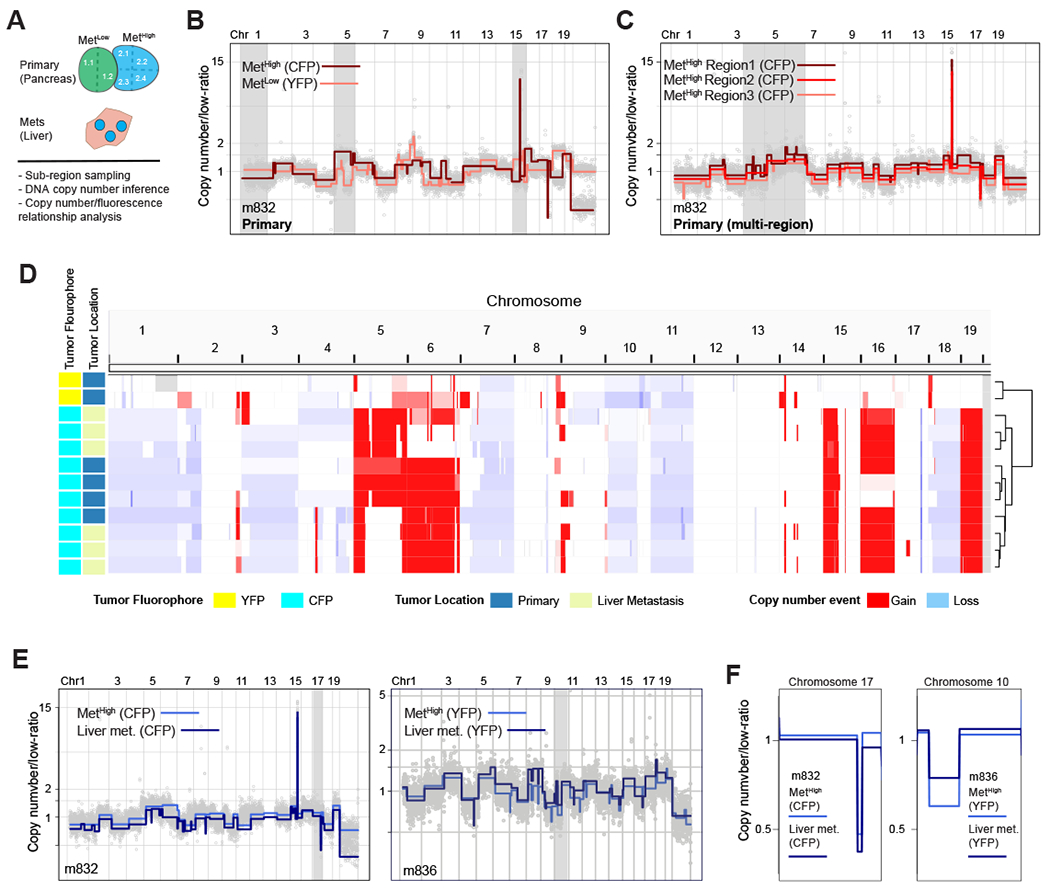

Individual tumor lineages in KPCXY mice correspond to clones with distinct somatic copy number profiles

Although primary KPCXY tumors were easily distinguishable based on the expression of a distinct fluorophore, each tumor could have arisen via the clonal expansion of a single cell or through fusion of multiple tumors which happened to share the same color. Somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) have been shown to provide an unambiguous picture of genomic heterogeneity and lineage relationships between primary tumors and matching metastases in human disease (35). Consequently, we performed copy number analysis via genome sequencing on a set of 20 primary tumors, including multi-regional sampling on a subset of the tumors where sufficient tissue was available (9 tumors with 2-4 regions sampled per tumor) (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table 1). Tumors bearing different colors exhibited unique DNA copy number profiles, indicating that they arose independently (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S2A) (36). By contrast, multi-regional sampling of monochromatic tumors revealed shared copy number alterations, indicating that all subregions within a given tumor (defined by color) shared a common ancestral lineage (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. S2B). In addition, subregion-specific alterations were also observed, suggesting that subclonal heterogeneity is also present in each tumor (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. S2B). These results suggest that the monochromatic tumors observed in KPCXY mice are clonal in origin and continue to undergo subclonal evolution during tumor progression.

Figure 2: Somatic copy number alteration analysis confirms fluorescence based lineage relationships and reveals genetic heterogeneity in paired primary pancreatic tumors and liver metastases.

A. Schematic representation of KPCXY pancreatic tumor and matching liver metastases with multi-region sampling for copy number sequence analysis.

B. Representative genome-wide copy number profiles of MetHigh (CFP+ fluorescence) and MetLow (YFP+ fluorescence) tumors from mouse 832 (m832) as depicted in Fig. 1E. Gray shading denotes alterations that are unique to the MetHigh (CFP+) tumor. Y-axis illustrates normalized read count values (low-ratio) which are directly proportional to genome copy number at a given chromosomal location. The copy number profiles are centered around a mean of 1 with gains and deletions called for segments with values higher and lower than the mean, respectively (Methods).

C. Representative genome-wide copy number profiles of three sub-sampled tissue regions of the MetHigh (CFP+) primary tumor from m832. Gray shading denotes alterations that are found heterogeneously from multi-region sequencing of the primary tumor.

D. Genome-wide heatmap with hierarchal clustering based on copy number alterations of matched primary and metastatic samples profiled from m832.

E. Representative genome-wide copy number profiles of fluorescently matched primary and metastatic tissue from two profiled mice (m832-left panel and m836-right panel) illustrating the shared clonal genetic lineage.

F. Zoom-in chromosomal views of copy number alterations with distinguishing breakpoint patterns supporting shared genetic lineage. Panels are ordered as in (E).

To ascertain the lineage relationships between primary tumors and metastases, we compared DNA copy number profiles between liver metastases and primary tumors within a given mouse. This revealed that primary tumors and metastases of the same color shared common DNA copy number profiles across the dataset, confirming on a genetic basis the fluorescence-based lineage relationships (Fig. 2D–F, Supplementary Fig. S2C). As most lung metastases were microscopic and difficult to isolate by dissection, they were not included in the molecular analysis. Together, these results indicate that the lineage history of metastases can be inferred by color and genomic analysis, allowing primary tumors with high vs. low metastatic potential to be unambiguously classified.

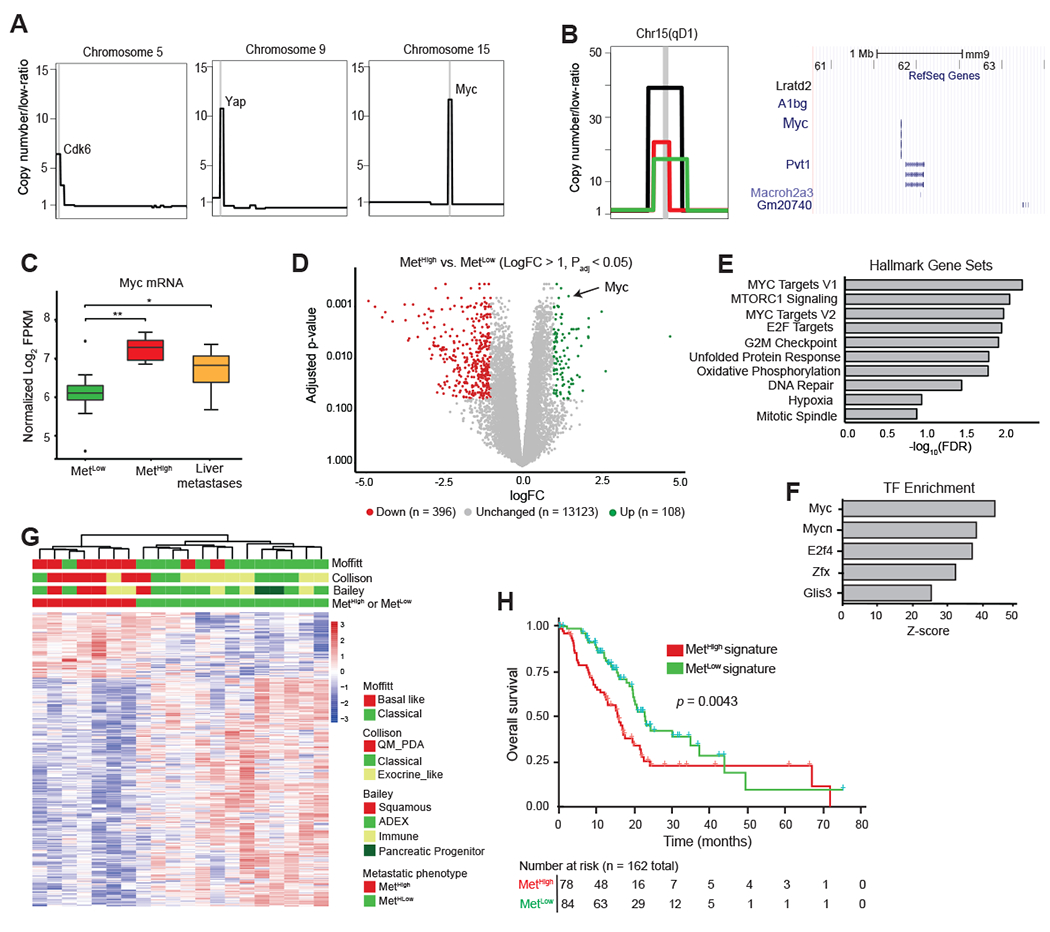

Genomic and transcriptional analyses identify Myc as a potential driver of metastatic phenotypes

We next sought to examine the molecular differences that distinguish primary tumors with high vs. low metastatic potential. We began by examining large scale (mega-base level as well as chromosome wide) SCNAs in 20 MetHigh and MetLow primary tumor samples. This analysis revealed largely similar genome-wide copy number patterns between MetHigh and MetLow primary tumors, with key PDAC associated genes, such as loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) at Cdkn2a/b and Trp53 as well as chromosomal gain of Kras occurring at similar frequencies (Fig. S3A). Thus, KPCXY tumors exhibit frequent copy number alterations in canonical PDAC genes, but these alterations do not account for the variation in metastatic behavior between MetHigh and MetLow tumors.

We next asked whether other factors (genomic and/or transcriptional) may be acting to enhance metastasis in the MetHigh group. Focal amplifications in driver oncogenes – Cdk6 and Yap in breast cancer and mutant Kras in PDAC – have been linked to the acquisition of metastatic competence (13,14,37,38). Consistent with prior studies, we observed focal amplicons at genomic regions encoding Cdk6, Yap, and Kras in our tumors (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. S3A) (13,14,37–39). However, in contrast to these amplifications, which occurred at equal frequencies in MetHigh and MetLow tumors, focal high amplitude amplifications in Myc were found in 42.8% (3/7) of MetHigh tumors compared to 7.6% (1/13) of MetLow tumors (Fig. 3B). Thus, Myc amplifications are enriched in MetHigh tumors. In all cases, these amplifications were maintained in paired metastases (Supplementary Fig. S3B). In addition, RNA-seq analysis demonstrated significantly higher levels of Myc transcripts in MetHigh tumors and metastases compared to MetLow tumors (Fig. 3C); overall, Myc was the third-most significantly upregulated gene in MetHigh tumors compared to MetLow tumors (Fig. 3D). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the differentially expressed genes between MetHigh and MetLow tumors identified MYC and E2F signatures as highly enriched, along with other signatures that have been implicated in PDAC metastasis including unfolded protein response, oxidative phosphorylation, and hypoxia (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Table S2) (31,40,41). Moreover, MetaCore transcription factor enrichment analysis identified MYC as the TF most significantly associated with genes overexpressed in MetHigh tumors (Fig. 3F), and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis placed Myc at the center of the interactome generated by these differentially expressed genes (Supplementary Fig. S4). Collectively, these results demonstrate a strong association between a tumor’s metastatic behavior and the abundance and/or activity of Myc at the genomic and transcriptional levels.

Figure 3: The MetHigh phenotype is associated with focal, high amplitude Myc amplifications and elevated expression.

A. Schematic representation of focal amplifications identified in profiled primary tumors. Vertical gray line denotes the location of amplicon and likely driver gene.

B. (Left) Representative focal amplification containing the Myc locus on chromosome 15 of a MetHigh tumor. (Center) Zoomed in schematic representation of three identified Myc amplicons in MetHigh tumors illustrating the focal and high-amplitude nature of the event. Each event (amplicon) is illustrated by a different colored segment line. The shared amplified region between the different amplicons is denoted by the chromosomal cytoband top of panel and illustrated in a UCSC genome browser view (Right) with RefSeq Genes, including Myc, illustrated.

C. Box-and-whisker plot showing Myc mRNA levels in MetHigh tumors (n=7) and paired metastases (N=34) compared to MetLow tumors (n=13).

D. Volcano plot illustrating genes meeting cutoffs for differential expression (logfold-change >1, Padj <0.05) between MetHigh and MetLow tumors (n=20 tumors used in the comparison). Genes upregulated in MetHigh tumors are highlighted in green, and genes upregulated in MetLow tumors are highlighted in red.

E. Top ten Hallmark Gene Sets identified as enriched in MetHigh tumors compared to MetLow tumors using all differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (adj. p < 0.05).

F. Top five transcription factor binding sites enriched in DEGs in MetHigh tumors compared to MetLow tumors (adj. p< 0.05) identified by Metacore prediction software.

G. Heatmap showing unsupervised clustering of differentially expressed genes (logfold-change >1, Padj <0.05) between MetHigh and MetLow tumors (n=20) and their association with PDAC transcriptional subtypes previously reported by Collison (42), Moffitt (15), and Bailey (16).

H. Kaplan-Meier analysis showing overall survival of PDAC patients in the TCGA cohort stratified into those with a MetHigh signature (red line) versus those with a MetLow signature (blue line). Signature based on DEGs with absolute logfold-change > 0.58 and Padj <0.05 (736 up and 1036 down regulated genes)

Statistical analysis in (C) was performed by Wilcoxon test (*, p=3.9x10−4; **, p=5.3x10−5). Box and whiskers represent median mRNA expression and interquartile range. Statistical analysis in (H) was performed by log-rank test.

Human PDAC can be grouped into two main transcriptomic subtypes – a well-differentiated classical/exocrine-like/progenitor (classical) subtype and a poorly differentiated squamous/quasi-mesenchymal/basal (basal-like) subtype (15,16,18,42). We found that MetHigh tumors were associated with basal-like PDACs, in line with their more aggressive behavior (Fig. 3G). Likewise, applying murine MetLow and MetHigh signatures (see Methods) to human TCGA data predicted a worse survival – indicative of disease recurrence – for patients with a MetHigh signature (Fig. 3H). These data indicate that murine MetHigh tumors correspond to the more aggressive subtypes of human PDAC.

A panel of cell lines that preserve the MetLow and MetHigh phenotypes

To understand the mechanisms underlying these different metastatic properties, we generated a panel of cell lines from six MetHigh tumors and five MetLow tumors. Consistent with the parental in vivo tumors, Myc gene expression and Myc protein levels were higher in the MetHigh lines compared to the MetLow lines (Fig. 4A–B). SCNA analysis in these cells lines found that they retained the majority of the genomic alterations found in the matched primary samples, including Myc amplifications (Supplementary Fig. S5A–B). Furthermore, Myc amplifications were not found in any of the cell lines whose tumors were originally characterized as non-Myc amplified, indicating that in vitro culture does not select for this specific copy number alteration. Importantly, elevations in Myc mRNA and protein were observed in both the Myc amplified and non-amplified MetHigh lines, suggesting that elevated Myc expression is a stable phenotype of these cells in culture.

Figure 4: Myc regulates metastasis by enhancing tumor cell intravasation.

A. Bar graph showing Myc mRNA levels in cell lines derived from MetHigh and MetLow tumors, normalized to Gapdh (n=6 MetHigh and n=5 MetLow cell lines).

B. Western blot showing corresponding MYC protein levels in cell lines derived from MetHigh and MetLow tumors shown in (A).

C. Representative fluorescent images of primary tumors and associated liver and lung metastases following orthotopic transplantation of the cell lines in (A) and (B) into NOD.SCID mice. The bar graph shows the total number of metastases (liver and lung) counted following orthotopic transplantation of 5 MetLow cell lines or 5 MetHigh cell lines (pooled data from n=49 mice in total).

D. Representative fluorescent images of primary tumors, liver, and lung metastases following orthotopic transplantation of MetLow cell lines that were stably transduced with either a Myc overexpression construct (Myc_OE) or empty vector (EV). The bar graph shows the total number of metastases (liver and lung) counted following orthotopic transplantations of Myc_OE or EV cells. Data were pooled from 4 independent MetLow lines transduced with either the Myc_OE or EV construct transplanted into 12 NOD.SCID (for the Myc_OE cells) or 10 NOD.SCID mice (for the EV cells).

E. Quantification of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in arterial blood derived from the orthotopic tumors depicted in (c) (n=27 mice examined) and (D) (n=12 mice examined).

F. Representative fluorescent images of lung metastases following tail vein injection of cell lines derived from the MetLow and MetHigh primary tumor clones. The bar graph shows the total number of lung metastases counted following tail vein injection of 5 MetLow cell lines or 5 MetHigh cell lines (pooled data from n=36 mice in total).

Statistical analysis by Student’s unpaired t-test with significance indicated (*, p=0.0152; **, p = 0.013; ***, p= 0.0008; **** p < 0.0001; ns, not significant). Error bars indicate SEM (C-F). Scale bar = 1 mm (C-D,F).

To investigate the metastatic properties of the MetHigh and MetLow lines in vivo, we performed orthotopic implantation of 5 MetHigh and 5 MetLow lines into the pancreas of NOD.SCID mice and examined distant organs for evidence of metastasis. Although the weights of MetHigh and MetLow tumors were not significantly different (Supplementary Fig. S6A), MetHigh tumors gave rise to 28-fold more liver and lung metastases compared to MetLow tumors (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the cell line expression differences, the orthotopic MetHigh tumors expressed higher levels of Myc compared to MetLow tumors (Supplementary Fig. S6B). To further confirm that differences in Myc expression were sufficient to drive the metastatic phenotype, we introduced a Myc overexpression (Myc_OE) construct into 4 MetLow lines and generated orthotopic tumors (Supplementary Fig. S6C). Myc overexpression led to a dramatic (22-fold) increase in liver and lung metastases (Fig. 4D). Thus, cell lines derived from spontaneously-generated MetHigh and MetLow tumors retain their metastatic phenotypes upon implantation.

Myc promotes tumor cell intravasation through the recruitment of tumor associated macrophages

To form distant metastases, cancer cells must navigate a series of events collectively referred to as the “metastatic cascade.” These events include (i) intravasation into the bloodstream or lymphatics, (ii) survival in the circulation, (iii) extravasation from the vessel, and (iv) growth and survival at the distant site (43). To determine the step(s) at which Myc was exerting its prometastatic effects, we began by measuring the number of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in orthotopically-implanted MetHigh and MetLow tumors and in MetLow tumors engineered to overexpress Myc. Remarkably, CTCs arising from MetHigh and Myc_OE tumors were 38-fold and 17-fold more abundant than those arising from MetLow tumors (Fig. 4E), far greater than the approximately 2-fold increase in tumor weight resulting from Myc overexpression (Supplementary Fig. S6D). Next, we performed a tail vein metastasis assay, which bypasses the invasion step by introducing tumor cells directly into the bloodstream, and measured lung metastases. Surprisingly, in contrast to the orthotopic tumor experiment, there was no difference in the number of metastases between MetHigh and MetLow lines (Fig. 4F). Moreover, Myc over-expression had no effect on tumor cell survival in the circulation (Supplementary Fig. S6E–G). Taken together, these data suggest that MetHigh tumors achieve a higher metastatic rate principally by promoting cancer cell invasion into the circulation, which can be driven by increased Myc expression.

Beyond activation of tumor cell intrinsic programs, Myc can also affect tumor phenotypes by altering the tumor immune microenvironment (TiME) (44–46). Thus, we sought to determine if differences in Myc levels between MetHigh and MetLow tumors were associated with distinct TiMEs. To this end, we examined the immune composition of parental primary tumors by staining for markers of immune cells previously implicated in metastasis of PDAC and other cancers. While MetHigh and MetLow tumors had a similar degree of neutrophil infiltration, MetHigh tumors had lower numbers of CD3+ T cells but were highly enriched for F4/80+ macrophages (Fig. 5A). Thus, compared to MetLow tumors, the TiME of MetHigh tumors contains an increased number of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs).

Figure 5: Myc recruits pro-metastatic macrophages to the tumor microenvironment.

A. Representative immunofluorescence images (top) and quantification (bottom) of T cells (CD3+), Neutrophils (anti-neutrophil antibody+), and macrophages (F4/80+) in primary KPCXY tumors categorized as MetLow or MetHigh, with quantification below (n=3 mice for each subgroup and 4-5 random fields of view analyzed).

B. Representative immunofluorescence images (left) and quantification (right) of macrophages that have migrated across a transwell filter following co-culture with MetHigh or MetLow tumor cells (n=2 MetLow and 2 MetHigh cell lines used, 3 replicates per cell line with 3 20X images taken per transwell; each dot represents quantification of an independent image).

C. Quantification of tumor infiltrating macrophages (as a percentage of total CD45+ cells) in MetLow or MetHigh subcutaneous tumors assessed by flow cytometry (n=5 MetHigh cell lines and 3 MetLow cell lines; 2 NOD.SCID mice examined per cell line with 2 tumors per mouse; each dot represents an independent tumor).

D. Quantification of tumor infiltrating macrophages (as a percentage of total CD45+ cells) in Myc_OE or control (EV) subcutaneous tumors assessed by flow cytometry (n=2 Myc_OE cell lines and 2 EV cell lines; 2 NOD.SCID mice examined per cell line with 2 tumors per mouse; each dot represents an independent tumor).

E-F. Representative immunofluorescence images (left) and quantification (right) of Arg1+ (E) and CD206+ (F) tumor associated macrophages in primary KPCXY tumors categorized as MetLow or MetHigh (n=3 mice for each subgroup and 4-5 random fields of view analyzed).

G-H. Quantification of Arg1+ (G) and CD206+ (H) tumor associated macrophages in primary MYC_OE or control (EV) orthotopic tumors assessd by immunflourescence staining (n=2 Myc_OE cell lines and 2 EV cell lines; 2 NOD.SCID mice examined per cell line; 4-5 random fields of view analyzed).

I. Quantification of tumor cell intravasation from an in vitro trans-endothelial migration (iTEM) assay. MYC_OE or EV-transduced tumor cells were cultured in transwell filters seeded with an endothelial cell monolayer in the presence or absence of macrophages (see Methods). Tumor cells that traversed the endothelial layer were quantified and normalized to the EV control in the absence of macrophages for each of two MetLow tumor lines.

J. Schematic outline of the macrophage depletion experiment. Mice were orthotopically implanted with Myc-OE cells (n=2 independent cell lines) and after 10d tumor-bearing animals were treated with a combination of CSFR inhibitor (GW2580) and liposomal clodronate (CLD) or vehicle. Metastases were quantified 14d later.

K. Quantification of total metastases (liver and lung) following the macrophage depletion strategy outlined in (J) (n=6 control mice and n=7 GW2580+CLD mice; each dot represents an independent mouse).

Statistical analysis (A-H, K) by Student’s unpaired t-test with significance indicated (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0001; ns, not significant); statistical analysis (I) by two-way ANOVA (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars = 10 μm (A, E-F) and 50 μm (B).

To examine the ability of MetHigh and MetLow tumor cells to recruit macrophages, we co-cultured these cell lines with primary bone marrow derived murine macrophages (BMDMs) in a transwell migration assay (39). Compared to MetLow co-cultures, MetHigh co-cultures exhibited greater macrophage migration towards the tumor cells (Fig. 5B). Consistent with these in vitro results, orthotopic tumors generated from MetHigh cell lines exhibited greater TAM infiltration than those generated from MetLow cell lines (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, MetLow lines overexpressing Myc gave rise to tumors with greater TAM infiltration compared to controls (Fig. 5D). These results demonstrate that MetHigh tumors exhibit enhanced macrophage recruitment and implicate Myc expression as a driver of macrophage infiltration. Macrophages have been reported to facilitate metastasis in several cancers (47). This is achieved, in part, through the activation of an “M2-like” polarization state in TAMs characterized by increased expression of Arg1 and CD206 expression (48). To determine whether Myc expression in pancreatic tumor cells alters macrophage phenotypes, we stained for these markers and found that both MetHigh tumors and Myc_OE tumors were enriched for Arg1+ and CD206+ TAMs compared to MetLow and EV control tumors (Fig. 5E–H). Thus, Myc over-expression is associated with an enrichment for M2-like macrophages in the tumor microenvironment.

In breast cancer, macrophages promote tumor cell invasion and metastasis through the development of specialized structures called Tumor Microenvironment of Metastasis (TMEM) doorways, in which macrophages facilitate the movement of cancer cells across an endothelial barrier (49). To investigate whether macrophages might promote metastasis in PDAC through a similar mechanism, we performed an in vitro trans-endothelial migration (iTEM) assay, in which the pro-invasive activity of Myc over-expression and macrophages could be directly assessed (50–52). Tumor cell intravasation across an endothelial monolayer was enhanced by either the addition of macrophages or Myc over-expression, an effect that was greatest when both stimuli were present (Fig. 5I).

To directly test whether TAMs are required for Myc driven metastasis in PDAC, we performed a macrophage depletion experiment. We generated orthotopic tumors from MetLow Myc_OE cells and 10 days later treated mice with a combination of the colony stimulating factor receptor inhibitor (CSFRi) GW2580 and liposomal clodronate (CLD) (Fig. 5J). Consistent with prior studies (29,53–55), this regimen was highly effective at depleting both circulating and tumor resident macrophages (Supplementary Fig. S7A–B) and caused a modest increase in tumor weight (Supplementary Fig. S7C). Depeletion also reduced tissue resident macrophages in liver and lung pre-metastatic niches with no significant effect on neutrophil abundance (Fig. S7D–F). Macrophage depletion resulted in a 4-6-fold reduction in metastases (Fig. 5K), an effect that had no impact on CTC viability, seeding, or outgrowth in the lung (Supplementary Fig. S7G–J). Taken together, these data suggest that Myc enhances metastatic spread at least in part by creating a TAM-rich environment in the primary tumor that increases tumor cell invasion. While previous studies have implicated macrophages in tumor cell infiltration, these results directly link this process to the genomic and transcriptional activation of Myc, which occurs naturally in our model and is subsequently selected for as a driver of metastasis (21,26,28,47,53,56–61).

Myc ehances TAM recruitment and metastasis through increased expression of Cxcl3 and Mif

To identify factors that might be responsible for the increased abundance of macrophages in MetHigh tumors, we mined our RNA-seq data to identify secreted factors that are differentially expressed between MetHigh and MetLow tumors (p value <0.01 and logFC >1). This resulted in identification of six cytokines/chemokines upregulated in MetHigh tumors (Supplementary Fig. S8A). Interestingly, each of these factors has been previously implicated in regulating macrophage recruitment in pancreatic and other cancer types (59,62–65). To determine which of these factors may be regulated by Myc in a clinically relevant setting, we examined gene expression data from the COMPASS trial cohort of PDAC patients, comparing tumors with either high or low levels of MYC expression. This revealed that three of the six factors (Mif, Cxcl3, and Ccl3) were also enriched in human PDACs exhibiting elevated Myc expression (Fig. 6A). To determine which of these factors depend on Myc for their expression, we used shRNA to knock down Myc levels in three MetHigh tumor lines (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Mif and Cxcl3 expression was significantly reduced following Myc knockdown (Fig. 6B) whereas the expression of the other factors was either unchanged or elevated following Myc knockdown (Supplementary Fig. S8C). Consistent with these findings, Myc overexpression in a MetLow cell line resulted in the upregulation of these factors (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, analysis of the Gene Transcription Regulation Database and Eukaryotic Promoter Database revealed direct evidence for Myc binding to the Cxcl3 and Mif promoters (Supplementary Fig. S8D–E) (66–69). These results suggest that Myc regulates macrophage recruitment in part through the regulation of Mif and Cxcl3.

Figure 6: Myc acts through Cxcl3 and Mif to promote macrophage recruitment and metastasis.

A. Expression of selected cytokines/chemokines in human PDAC. Samples from the COMPASS cohort (enriched for tumor cells by laser capture microdissection) were stratified into MYC high and low groups based on RNA-seq (n=373) and assessed for the expression of five chemokines/cytokines identified as significantly upregulated in MetHigh vs. MetLow tumors (Supplementary Fig. S8A).

B. Relative expression of Mif and Cxcl3 in control or Myc knockdown (shRNA) MetHigh cell line 850_MetHigh_4. Data is representative of 2 independent Myc shRNAs (n=3 biological replicates).

C. Bar graph showing fold-increase in Cxcl3 and Mif mRNA levels comparing Myc_OE to EV control cell lines. Data representative of 2 independent cell lines (n=3 biological replicates)

D. Quantification of total F4/80+ tumor infiltrating macrophages by immunoflourescence in cell lines that were stably transduced with either a Cxcl3 or Mif overexpression construct (Cxcl3_OE and Mif_OE, respectively) or empty vector (EV). (n=4 tumors examined from each group with 4-5 random fields of view analyzed).

E. Quantification of total metastases (liver and lung) following orthotopic transplantation of EV, Cxcl3_OE, or Mif_OE orthotopic tumors from (D). Data were pooled from 2 independent MetLow lines transduced with either the Cxcl3_OE, Mif_OE, or EV construct transplanted into 5 NOD.SCID mice (for each cell line). Each dot represents an independent animal.

F. Quantification of macrophages that migrated across a transwell filter following co-culture with 832 Myc_OE tumor cells treated with either a Cxcr2 inhibitor (AZD-5069) or a Mif inhibitor (ISO-1). Data are representative of two independent experiments; 3 replicates with 4-5 20X images taken per transwell.

G. Schematic outline of the Cxcr2 and Mif inhibitor experiment. Mice were orthotopically implanted with 832 Myc_OE cells and after 10d were treated with a Cxcr2 inhibitor (AZD-5069), Mif inhibitor (ISO-1), combination (AZD-5069+ISO-1), or vehicle. Metastases and macrophages were quantified 14d later.

H-I. Quantification of F4/80+ (H) and CD206 (I) macrophages in orthtotopic tumors following the Cxcr2 and Mif strategy outlined in (G) (n=4 tumors per group, 4-5 random fields of view analyzed; each dot represents an independent animal).

J. Quantification of total metastases (liver and lung) following the Cxcr2 and Mif strategy outlined in (G) (n=4 control mice, n=4 AZD-5069 mice, n=4 ISO-1 mice, and n=4 AZD-5069+ISO-1 mice; each dot represents an independent animal).

Statistical analysis by Student’s t-test with significance indicated (*, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.007; ****, p<0.0005; *****, p<0.0001; n.s., not significant). Error bars indicate SEM.

To further examine the role of these chemokines in macrophage recruitment, we overexpressed each factor in MetLow lines (Supplementary Fig. S8F) and examined their effects in vivo. Compared to controls, orthotopic tumors from Cxcl3_OE and Mif_OE cells resulted in a 3-4-fold increase in intratumoral macrophages (Fig. 6D) and a significant increase in lung and liver metastases (Fig. 6E). Thus, Cxcl3 and Mif overexpression is sufficient to increase TAM abundance and promote metastasis of MetLow tumors.

Tumor secreted factors can regulate immune cell phenotypes through specific recptor-ligand interactions and enzymatic activities. The cognate receptor for Cxcl3 is Cxcr2, which has previously been reported to modulate myeloid cell recruitment in prostate cancer and PDAC (59,70). Similary, Mif can regulate immune cell function through binding various receptors and its tautomerase activity (71,72). To examine the role of these factors in macrophage recruitment in our system, we treated Myc_OE tumor cells with a Cxcr2 inhibitor (AZD5069) or Mif inhibitor (ISO-1) in an in vitro transwell migration assay (52,70,72,73). Compared to vehicle controls, inhibition of Cxcr2 or Mif led to 2-10 fold decrease in macrophage migration (Fig. 6F). Next, we assessed the impact of these drugs on TAM recruitment and metastasis in vivo (Fig. 6G). Treatment of Myc_OE orthotopic tumors with AZD5069 or ISO-1 reduced TAM recruitment and metastatic burden (Fig. 6H–J) and caused a slight decrease in tumor weight (Supplementary Fig. S8G). Interestingly, compared to each inhibitor alone, the combination of both inhbitors resulted in significantly lower levels of TAMs (F4/80+ and CD206+) and metastasis (Fig. 6H–J). Taken together these data suggest that multiple Myc-regulated factors contribute to macrophage recruitment and metastasis in PDAC.

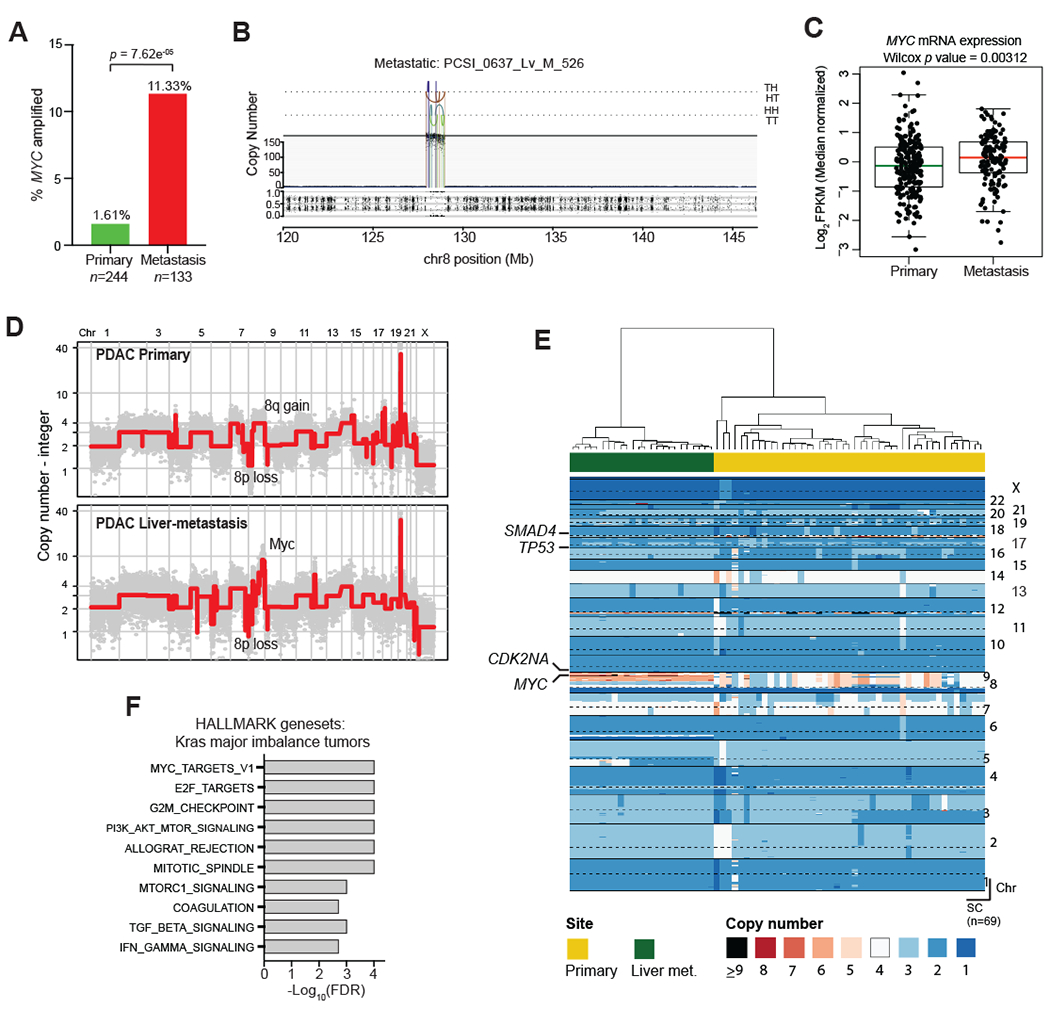

Metastasis in human PDAC is associated with MYC gene amplification and elevated expression

Given the finding that genomic and transcriptional variation in Myc was associated with metastatic heterogeneity in murine PDAC, we sought to determine whether MYC is associated with similar metastatic phenotypes in human PDAC. Since the majority of PDAC samples in the ICGC and TCGA are derived from resected stage I/II tumors (18), these datasets provide limited insight into the determinants of metastatic burden. Consequently, we analyzed data from the COMPASS trial cohort (NCT02750657) which is focused on metastatic PDAC patients and utilizes laser capture microdissection (LCM) to enrich for tumor cells prior to whole genome sequencing or RNA-seq (14,74). By comparing primary tumors and metastases, we found that 11.3% (n=17/133) of metastases were enriched for MYC amplifications compared to 1.61% (n=4/244) of resectable tumors (Fig. 7A–B; p=7.6e-5, Fisher’s test). Likewise, advanced tumors (defined as either locally advanced or metastatic) were significantly enriched for MYC amplifications (9.22%; n=19/206) compared to resectable tumors having no evidence of metastasis at diagnosis (1.04%; n=2/192) (Supplementary Fig. S9A; p=1.33e-4). As predicted, amplification was associated with higher levels of MYC mRNA (Supplementary Fig. S9B). MYC amplified tumors did not exhibit greater genomic instability compared to non-amplified tumors (Supplementary Fig. S9C), indicating that MYC amplification is not a proxy for more generalized chromosome-level events. Moreover, metastases expressed higher levels of MYC mRNA than primary tumors (Fig. 7C; p=0.00312). These results indicate that MYC amplification and transcriptional upregulation are strongly associated with PDAC metastases.

Figure 7: MYC amplification and enhanced transcriptional activity are associated with metastasis in human PDAC.

A. Bar graph showing the relative frequencies of MYC amplifications in primary PDAC tumors and metastases from the COMPASS cohort.

B. Representative plot of chromosome 8 from a metastatic tumor with MYC amplification. Orientation of breakpoint junctions from intra-chromosomal rearrangements indicated by TH, HT, HH, and TT where T = tail (3’ end of fragment) and H = head (5’ end of fragment).

C. Box-and-whisker plot showing MYC mRNA levels (FPKM) in primary PDAC tumors and metastases.

D. Representative genome-wide absolute copy number plots of single cells retrieved from a primary (top panel) and its matched metastasis (lower panel) illustrating acquisition of focal MYC amplification in the metastatic lesion.

E. Heatmap depiction of cancer single cells sequenced from a matched primary PDAC and its liver metastasis. Color codes indicate absolute copy number in single-cells. Top bar plot depicts tissue site from where single-cells were retrieved.

F. Gene set enrichment analysis of tumors with a major imbalance of mutant KRAS (compared to those with no major imbalance) in the COMPASS cohort.

Box-whisker plot in (C) indicates mean and interquartile range.

Next, we examined a separate patient cohort (n=20) in which matched primary PDAC tumors and metastases were available for comparison. MYC amplifications were common in the primary tumors of patients with metastatic disease (35.0%; n=7/20), and these amplifications were retained in the matching metastases (Supplementary Fig. S9D), similar to our mouse model. The enrichment of MYC amplifications in metastatic samples and the observed retention of the amplification when analyzing matched primary/metastasis samples suggests that amplification and/or transcriptional upregulation of MYC in primary PDACs are selected for and retained during tumor metastatic progression. Consistent with this notion, we identified a PDAC patient in whom single cell analysis of a paired primary tumor and metastasis revealed enrichment of a MYC amplified subclone in the metastatic lesion compared to the primary (Fig. 7D–E, Supplementary Fig. S9E). Collectively, these data suggest that enhanced expression and/or genomic amplification of MYC is associated with metastatic spread in human PDAC, complementing our findings from the mouse model.

Discussion

Phenotypic variation, the result of inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity arising during tumor progression, has made it challenging to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor spread (1,75). Consequently, the demonstration that certain genes function as “metastasis drivers” – promoting metastasis through mechanisms distinct from their roles in primary tumor growth – has proven elusive (76). In this study, we exploited an autochthonous PDAC model with varying degrees of metastatic spread to explore the molecular basis of naturally-arising variation in metastatic burden. This system revealed a strong association between the level of Myc – at either the genomic or transcriptional level – and tumor metastasis, a relationship that was also observed in human PDAC samples. Myc exerts its pro-metastatic effect at least in part by recruiting pro-invasive TAMs, leading to greater tumor cell intravasation into the bloodstream. These activities are not directly related to Myc’s well-described role in primary tumor growth (46,77,78), as tumors with different levels of Myc expression grow at comparable rates despite dramatic differences in metastatic ability.

Prior work by us and others has examined the genetic events associated with PDAC metastasis. In one study, a comparison of matched primary tumors and metastases from four patients failed to reveal nonsynonymous mutations in driver oncogenes that distinguished primary tumors from metastases (79). By contrast, examination of DNA copy number changes in mouse and human PDAC revealed a significant association between increased mutant KRAS gene dosage and metastatic progression (13,14). While our mouse studies did not detect an association between Kras focal amplification and metastatic potential, Kras gains (via entire gain of chromosome 6) were detected with comparable frequency in both MetHigh and MetLow tumors, consistent with the ability of both tumor populations to metastasize. Interestingly, among PDAC patients with KRAS amplifications or major allelic imbalances, the MYC_TARGETS geneset represented the most highly enriched signature in (Fig. 7F) mirroring the enrichment of this signature in MYC amplified PDAC tumors (Supplementary Fig. S9F). Signaling through KRAS has long been known to impact MYC expression (44,80–82), and thus our results are consistent with a model in which elevated MYC activity – as a result of MYC and/or KRAS amplification, or some other mechanism – enhances metastatic activity. This interpretation is consistent with recent studies of lung, breast, and prostate cancers identifying a link between MYC amplification and brain or bone metastasis (37,38,83).

Although tumor formation in the KPCXY model results from shared founder mutations (KrasG12D activation and Trp53 loss) our genomic analysis revealed ongoing somatic events during tumor progression, resulting in heterogeneous patterns of genomic alterations within a given tumor. Such alterations were largely present at the level of copy number gains and losses rather than point mutations or small insertion/deletions. Although the complexity of genomic rearrangements varied between tumors, the degree of genome instability did not correlate with metastatic burden. Thus, the increase in metastasis observed in MetHigh tumors is not a function of overall SCNA burden but is instead specific to Myc.

While subregions within a tumor shared many genomic alterations, consistent with a clonal origin, distinct copy number alterations were also present, suggesting ongoing subclonal evolution. Clonally related metastases exhibited unique (“private”) alterations; however most copy number gains and losses were shared with the parental primary tumor clone, suggesting that they were present prior to dissemination. In this respect, it is noteworthy that MYC amplifications in human PDAC were far more common in metastases than primary tumors, including one case in which we were able to trace a metastatic lesion directly to a MYC-amplified subclone in the primary tumor. Collectively, these results suggest that subclonal MYC amplifications, which have been observed in human primary tumors, provide a selective advantage during metastatic progression (84,85). Given that our analysis identified a Myc signature in tumor MetHigh clones without Myc amplifications, and MYC amplifications are present in only 11% of human PDAC metastases, other mechanisms for the increased expression of MYC mRNA in PDAC metastases are likely to exist.

As one of the best-studied oncogenes, MYC has been associated with multiple tumor-promoting activities (80). Given MYC’s role in tumor cell growth and proliferation, one possible explanation for our results is that MetHigh tumors had an earlier onset and/or grew more rapidly, leading to increased metastasis by mass effect. Against this possibility, we found that tumor size and proliferation rates showed no correlation with metastatic burden in either mouse models or human patients. Likewise, our MetHigh and MetLow cell lines exhibited dramatic differences in metastatic ability despite giving rise to primary tumors of comparable size. Prior studies have shown that Myc overexpression in the pancreas in the context of tumor initiation, without Kras activation, does not result in PDAC but rather insulinomas (86). By contrast, our work provides evidence that Myc hyperactivation – particularly in the setting of focal, high amplitude amplification – confers metastatic properties after a primary PDAC is established. These results suggest that genetic context (e.g. mutant Kras status) and timing (e.g. early vs. late) may determine whether enhanced tumor growth or promotion of metastasis is the prevalent phenotypic consequence of Myc hyperactivation.

Our studies implicate non-cell autonomous mechanisms involving the recruitment of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) as contributors to metastatic heterogeneity. The ability of TAMs to promote tumor cell invasion is well-documented (21,26,28,47,53,56–61), a property that is in agreement with our finding that MetHigh and Myc_OE tumors exhibit enhanced vascular intravasation. Furthermore, MYC expression in tumor cells is known to shape the makeup of the surrounding immune microenvironment, making it more immunosuppressive (39,45). In line with these observations, we find that MetHigh tumors are enriched for alternatively activated TAMs and have decreased T-cell infiltration – features that favor metastasis (21,26,28,30,31,47,53,56–61). Our data thus support a model wherein stochastically-arising tumor subclones with elevated levels of MYC alter the tumor immune microenvironment to facilitate intravasation and metastasis.

While the specific molecular mediator(s) of TAM recruitment remain to be fully elucidated, we speculate that MYC acts indirectly by regulating the expression of factors that regulate TAM migration and/or function. Consistent with this, we identified several chemokines/cytokines that were upregulated in MetHigh tumors and could also be induced by Myc overexpression. Functional validation of these factors identified Cxcl3 and Mif as potential mediators of TAM recruitment and associated metastasis. Furthermore, combined inhibition of Mif and Cxcr2 significantly reduced both metastasis and TAM invasion. Thus, we hypothesize that multiple secreted factors, as opposed to a single factor, act in concert to drive the MYC-associated increase in pro-invasive macrophages.

Most patients with PDAC develop metastases. Our data show that even within this population, the extent of metastatic disease varies widely between patients and impacts survival. While many steps are required for tumor cells to metastasize, our data indicate that bloodstream invasion may be a rate limiting event for metastasis in PDAC. Our work further suggests that in addition to its well-documented cell autonomous role in tumor growth, MYC acts non-cell autonomously to promote metastasis. Supporting this, modest overexpression of MYC was previously shown to suffice with KRAS activation to drive PDAC metatsasis in an autochthonous mouse model (44). Given that MYC family members are focally amplified in 28% of human cancer (87), these results have broad implications for metastasis in tumor types other than PDAC (88).

Materials and Methods

Mouse models

All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health policies on the use of laboratory animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. KPCX mice were generated through a series of backcrosses as previously described (32). The RosaConfetti (“X”) reporter allele was introduced into mutant strains bearing Pdx1CreER (“C”), KrasG12D (“K”), and Trp53fl/+ (“P”) alleles to obtain Pdx1CreER; KrasG12D; Trp53fl/+; RosaConfetti (“KPCX”) mice (32). For most experiments, animals were heterozygous for the confetti reporter and also contained a RosaYFP allele in lieu of the second confetti allele to generate “KPCXY” mice. The Yfp reporter was introduced to enable fluorescent lineage labeling of tumors that undergo a “no-color” recombination event in the confetti reporter as previously described (89). To induce recombination, a suspension of tamoxifen (MP Biomedicals) in corn oil (Sigma Aldrich) was administered to pups via lactation following oral gavage of the mother with 6 mg of the drug on postnatal day 0, 1, 2. On average, tumor bearing KPCXY mice were 14-16 weeks of age at time of sacrifice.

Multicolor image analysis

Pancreatic tumors and organs from tumor bearing KCPXY mice were isolated and analyzed by fluorescent stereomicroscopy using a Lecia M216FA fluorescent microscope with CFP, YFP, and dsRED filters (Chroma). As previously described (32), distinct colorimetric tumor clones in the primary tumor mass are defined as an anatomically contiguous region of monochromatic cells that share a border with adjacent clones of a different color (Fig. 1E, Fig. S1C). In order to accurately quantify the contribution of a different colorimetric tumors to metastases, we used the following criteria to identify KPCXY mice suitable for analysis: (i) presence of at least one metastatic lesion to the liver and/or lung, (ii) two or more tumors present, (iii) each metastatic primary tumor carries a unique fluorescent color, and (iv) metastatic lesions can be linked to specific tumor based on a shared unique fluorescent lineage label. Using these criteria, we identified a panel of 30 mice with a total of 85 tumors. Metastases were quantified by fluorescent stereomicroscopy. Tumor size was determined using ImageJ to measure the largest circumference of each fluorescent tumor.

Murine tumor and metastasis sample acquisition

Pancreatic tumors and associated liver and lung tissues were isolated from tumor bearing KPCXY mice. Under fluorescent stereomicroscopy, individual colored tumors were identified and biopsied using a 6mm punch biopsy. Initial biopsies were placed in 750μl of RNAlater (Sigma Aldrich) for downstream nucleic acid isolation. Subsequent biopsies were submitted for cell line generation and histology. In tumor where sufficient tissue was available, additional biopsies were taken from anatomically distinct regions of the tumor to obtain subclonal biopsies for genomic analysis. From 7 KPCXY mice, we obtained biopsies from 20 tumors, 8 of which were amenable to additional sub-regional biopsies. Paired primary tumors and metastases from each mouse were identified by shared fluorescent lineage labels. Metastases were harvested by microdissection under fluorescent stereomicroscopy and split and portions placed in 500μl of RNAlater for nucleic acid isolation or used directly for cell line generation. The remainder of the tissue was embedded for histology. In total, 56 metastases were isolated for genomic analysis. While individual liver metastases were of sufficient size for microdissection, lung lesions typically were microscopic and could not be readily isolated for molecular analysis.

Tumor digestion and cell lines

Pancreatic tumors were dissociated into single-cell suspensions through mechanical separation and enzymatic digestion as previously described (90). Murine PDAC cell lines 471_MetHigh_1, 832_MetHigh_1, 836_MetHigh_1, 850_MetHigh_4, 852_MetHigh_1, 853 MetHigh_1, 471_MetLow_2, 832_MetLow_2, 842_MetLow_2, 850_MetLow_1, 852_MetLow_2 were derived from KPCXY primary tumors that were also evaluated by SCNA and RNA-seq. Murine cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 medium supplemented with 5 mg/mL D-glucose (Invitrogen), 0.1 mg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor type I (Invitrogen), 5 mL/L insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS Premix; BD Biosciences), 25 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract (Gemini Bio-Products), 5 nmol/L 3,3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine (Sigma), 1 μmol/L dexamethasone (Sigma), 100 ng/mL cholera toxin (Sigma), 10 mmol/L nicotinamide (Sigma), 5% Nu-serum IV culture supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and antibiotics (gentamicin 150 μg/mL, Gibco; amphotericin B 0.25 μg/mL, Invitrogen) at 37°C, 5% CO2, 21% O2 and 100% humidity. Cell lines were maintained and passaged according to ATCC recommended procedures and regularly tested for mycoplasma using MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza).

Immunofluorescence and histological analysis

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (EMS) at room temperature for 45 minutes followed by an overnight incubation in 30% weight/volume sucrose solution (Sigma Aldrich). Samples were then embedded in O.C.T. (Tissue-Tek) and frozen on dry ice. Staining was performed on 10 μm sections by first blocking with 5% donkey serum and 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h followed by overnight incubation with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer in a humidified chamber. Sections were washed three times in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. For immunofluorescence (IF) staining, slides were then incubated with DAPI (Life Technologies, 1:1000), and Alexa flourophore conjugated antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For immunohistochemistry (IHC), slides were first incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and developed using the ABC HRP and DAB kits per manufacture protocols (Vectorlabs). Primary antibodies used were as follows: rat anti-Ki67 (eBioscience, 14-5698-82), rabbit anti-c-Myc [Y69] (Abcam, Ab32072), rabbit anti-CD3 (Invitrogen, PA1-29547), rabbit anti-F4/80 (Novus, NBP2-12506), rat anti-neutrophil (ABCAM, NIMP_R14), anti-CD206 (R&D systems, AF2535), and Rabbit Anti-Arg1 (Cell Signaling, 93668).

Bone marrow derived macrophage (BMDM) isolation

Bone marrow immune cells were isolated as described (91). 2x106 isolated immune cells were plated in a 6-well dish in IMDM (Gibco, 12440053) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine (Corning, MT25005CI), 1% Non-essential Amino Acids (Corning, 11140076), 1% Sodium pyruvate (Gibco, 11360-070), 0.001% 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco, 21985023), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, 15140163), 20ng/ml recombinant murine M-CSF (PeproTech, 315-02) at 37°C, 5% CO2, 21% O2 and 100% humidity. BMDMs were differentiated for 7 days and used by gentle scraping before 10 days

Macrophage transwell migration assay

Macrophage invasion was assessed using a 12-well transwell chamber with 5-8 mm filter inserts (Corning). Tumor cells were plated in the lower chamber 24 hours before addition of bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs). For Figures 5B and 6F, tumor cells were plated on growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning 356231) which was diluted 1:1 in PBS and plated onto the transwell. 100,000 BMDMs were plated per transwell. After 24 hours, the non-migrated BMDMs and Matrigel were gently removed with a swab. Cells in the lower surface (migrated BMDMs) of the membrane were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 mins. DAPI (Fig. 5B; Invitrogen D21490) or crystal violet stain (Fig. 6F; Sigma 65092a-95) was added in PBS to the transwells. The membranes were imaged and number of macrophages counted in 4 random fields. For Mif and Cxcr2 inhibition, AZD-5092 (MedKoo 206473, 0.1mM in DMSO) and ISO-1 (Santa Cruz sc-204807B, 200μm in DMSO) were added to tumor cells in transwells prior to co-incubation with the macrophages. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

Macrophage depletion in vivo

10,000 tumor cells were orthotopically injected into the pancreas of NOD.SCID mice. Treatments started 10 days after implantation. GW2580, CSF-1R inhibitor (AdooQ Bioscience, A11959) was dissolved in 0.5% hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose and 0.1% Tween (HPMT) and dosed 3 times a week at 160 mg/kg by oral gavage. 200ul of Clodronate or control liposomes (Liposoma, CP-025-025) was given once per week by intraperitoneal injection. Blood was sampled to confirm depletion. Experimental and control mice were euthanized 14 days after initiation of treatment and analyzed for metastasis and immune cells by flow cytometry. Control and experimental groups were run in at least triplicate.

Mif and Cxcr2 inhibition in vivo

50,000 tumor cells were orthotopically injected into the pancreata of NOD.SCID mice. Treatments started 10 days after implantation. The Mif inhibitor ISO-1 (Santa Cruz sc-204807B) was dissolved in DMSO to make a 0.05 mg/μl stock solution and then diluted to 10 mg/kg in HPMT solution for gavage 5 times a week. The CXCR2 inhibitor AZD-5092 (MedKoo 206473) was dissolved in HPMT and dosed 5 times a week at 0.1 mg/kg by oral gavage. Experimental and control mice were euthanized 14 days after treatment start and analyzed for metastasis and immune cells by immunoflouresence staining. Control and experimental groups were run in at least triplicate.

In vitro transendothelial migration (iTEM) assay

The iTEM assay was performed as previously described (50–52). Briefly, transwells from EMD Millipore (cat# MCEP24H48) were coated with 2.5 μg/mL Matrigel (cat# 356230, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) in a total volume of 50 μL. Then approximately 1 × 104 human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Lonza) in 50 μL of EGM-2 medium were plated on the inverted transwells previously coated with Matrigel and allowed to adhere for 4 h at 37 °C. Transwells were then placed into a 24-well plate with 1 mL of EGM-2 with all supplemental factors (Lonza) in the bottom well and 200 μL inside the upper chamber and allowed to grow for 48 h in order to form a monolayer. Pancreatic tumor cells (EV or Myc_OE) were labeled with CellTracker™ green dye and macrophages (Bac1.2F5) with CellTracker™ red (Green cat# C7025, Red cat# C34552, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), resuspended in DMEM media (cat# SH30253.01, Hyclone) without serum and plated at 15,000 pancreatic cancer cells without macrophages or with 60,000 macrophages per transwell and allowed to transmigrate towards EGM-2 containing 36 μg/ml of CSF-1 for 4 hrs. Samples were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 1% Triton-X 100 for 5 min and stained with ZO-1 (Sigma) to determine and locate the endothelial mono-layer formation. Transwell membranes were cut from the transwell chambers and mounted on a slide using Prolong Diamond anti-fade. The slides were imaged using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope using a 60x 1.4NA objective and processed using Image J (NIH). Quantitation was performed by counting the number of tumor cells that had crossed the endothelium within the same field of view (60X, 10 random fields) and represented as normalized values from at least 3 independent experiments.

Analysis of RNA-seq, differential gene expression, GSEA, and molecular subtype.

RNA sequencing was performed on bulk tumor and metastasis samples from 7 KPCX mice resulting in 66 samples for analysis (primary tumor with subregional biopsies and metastasis). RNA purity and integrity were verified on the Agilent Tapestation prior to library construction followed by paired-end 50-75bp sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 high-throughput sequencer. Alignment of fastq files was performed with STAR aligner v2.5.2b using mm10 as the reference genome (92). Gene level expression data in terms of expected counts and FPKM was obtained using RSEM v1.2.28(93). Low expressing genes were removed using cutoff of 100 for count and 10 for FKPM. For primary tumor clones where subregional biopsies were taken, count data for the tumor was obtained by merging expression data of the subclone count data using the mean value. This resulted in a total of 54 samples for downstream analysis (MetLow = 13, MetHigh = 7, and Metastasis = 34). For differential expression analysis, count data was normalized using the voom function in the limma R-package followed by batch correction using the ComBat R-package (94,95). Then limma was used to perform differential expression between MetHigh, MetLow, and metastasis. Boxplots of log2 FPKM values for genes were generated using the ggplot2 R-package. To generate volcano plots, differential expression data comparing MetLow and MetHigh clones was plotted using ggplot2 with log base 2-fold change from MetLow compared to MetHigh tumors of each gene was plotted on the x-axis and the adjusted p-values plotted on the Y axis. Genes with adjusted p-values less than 0.01 and absolute log2 fold change >1 were highlighted. Differentially expressed genes were used as input for GSEA MSigDB geneset enrichment analysis(96). Transcription factor enrichment on all differentially expressed genes was performed using the Metacore software package (https://clarivate.com/products/metacore/, Clarivate Analytics, London, UK). Network analysis was performed on all differentially expressed genes using ingenuity pathway analysis software (www.ingenuity.com, Ingenuity Systems Inc., Redwood City, CA). Molecular subtype classification using the Bailey, Moffitt, and Collision (15,16,42) signature was performed on each sample by subtracting the sum of normalized expression for genes corresponding to specific classes within a particular molecular signature. We then took the maximum score observed across each class and assigned to the samples. Heatmaps were generated using differentially expressed genes with adjusted p-value <0.05 and absolute LogFC >1.

Survival analysis of TCGA data

TCGA PAAD expression and patient and sample level clinical data was downloaded from cBioportal (http://www.cbioportal.org/). Samples were filtered to those classified as pancreatic adenocarcinoma and having available expression data (162 of 186 samples). To develop a signature gene list associated with the MetHigh phenotype, we filtered differentially expressed genes between MetHigh and MetLow tumors using an adjusted p-value <0.05 and absolute logFC >0.58 resulting in a set of genes that are upregulated or downregulated in the MetHigh tumors (736 Up and 1036 down). To calculate a signature score for each TCGA PAAD sample, we first z-score normalized the TCGA PAAD expression data and then subtracted the sum of all downregulated gene expression from the sum of all upregulated gene expression values. We divided the signature score into high and low strata using a cutoff score >0. Kaplan-Meier analysis was done to compare survival between the two groups.

Human Stage IV pancreatic tumor and metastasis imaging analysis

CT scans were obtained from patients with metastatic PDAC undergoing treatment at the University of Pennsylvania under an IRB approved protocol (#822028). Patients were filtered to include only those with CT-scan imaging of the abdomen and chest with IV contrast at the time of diagnosis and prior to any treatment and found to have Stage IV disease. In total, 55 patients were included. CT images for each patient were reviewed and metastatic lesions in liver and lung were counted. All metastases were examined in multiple planes to ensure accurate assessment. Tumor area was pulled from the initial radiologist report and measured at the largest diameter. The cut-off for high and low metastasis groups was determined using k-means with n=2 clusters.

Human pancreatic cancer patient sample acquisition with genomic and RNA-seq analysis

Sample acquisition resulted from patients recruited as part of the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) Pancreatic Cancer Ductal Adenocarcinoma Canadian sequencing initiative or the COMPASS trial as previously described (97). Tissue samples were collected at the University Health Network (Toronto), Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Toronto), Kingston General Hospital (Kingston), McGill University (Montreal), Mayo Clinic (Rochester), or Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston) with written informed consent and approval from Institutional Review or Research Ethics Boards. Whole Genome Sequencing and RNA Sequencing was performed on fresh frozen tumor tissue samples which were enriched for tumor content by laser capture microdissection (LCM). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and RNAseq were performed at the Ontario Institute of Cancer Research as described previously (97). DNA Read Alignment and MYC Copy Number Variations were performed on paired end whole genome sequencing reads aligned to human reference genome hg19 using BWA 0.6.2 (98). PCR duplicates were marked with Picard 1.90. Tumor cellularity, ploidy, and copy number segments were derived using an in-house algorithm CELLULOID (99). RNA reads were aligned to human reference genome hg38 and to transcriptome Ensemble v84 using STAR v2.5.2a (92). Duplicate reads were marked with Picard 1.121. Raw counts were obtained using HTSeq 0.6.1 (100). Differential gene expression analysis was performed with DESeq2 v.1.14.1 (101) using default settings. Briefly, RNA HTSeq count data was imported to generate a dispersion estimate and a generalized linear model. Wald statistical test was used to compare gene expression of MYC amplified to non-amplified cases. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using genes ranked based on the P value and sign of the log2 fold change from differential gene expression analysis. Gene set enrichment analysis was run using GSEA Preranked 4.0.2 with default settings against hallmark gene sets(96). Statistical Analyses included pairwise comparisons of quantitative variables performed using Wilcoxon rank sum test. All tests were two-sided. Analyses were carried out in R 3.3.0.

Somatic Copy Number Analysis (SCNA) in murine tumors

DNA purified from dissected murine tumors was processed for Illumina library preparation and sequencing using standard protocols. In brief, isolated DNA (between 100-100ng in total) was sonicated on a Covaris instrument. Sonicated DNA was then end-repaired and ligated to TruSeq dual-index library adaptors. Index libraries were subsequently enriched by 10 cycles of PCR amplification followed by pooling and multiplex sequencing targeting a coverage of roughly 2 million reads per sample (102). For data processing and copy number inference, sequencing data was processed as previously described with mouse genomic bins computed in a manner similar to human bins (36). In brief, sequencing reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome built mm9. Sequencing reads were indexed, sorted, with PCR duplicates removed. Uniquely mapped reads were counted in each bin and normalized for GC content using lowess smoothing. Normalized read count data were then segmented using Circular Binary Segmentation (CBS) (103) with the profiles centered around a mean of 1. Chromosomal segments with variance that was above or below the mean were called as gains or deletions, respectively. A threshold of 0.2 was used. For hierarchal clustering and lineage reconstruction, an analysis based on copy number values and alteration breakpoints, in a genome-wide manner, was employed.

Bulk and single cell analysis of matched primary and metastasis from human tissue

For 20 patients, tissue sections from flash frozen samples were processed for bulk DNA purification using Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit. Purified DNA was processed as described above for multiplex sequencing. A coverage of 2 million sequencing reads was similarly targeted. For a single case, matched pancreatic primary and liver metastasis tissue was retrieved and processed for single-nuclei isolation as previously described (36). Single-nuclei were sorted based on DNA content from both diploid and polyploid populations of each tissue. Approximately 100 nuclei per tissue sample were amplified using WGA4 kit (Sigma-Aldrich) with the resulting Whole Genome Amplified (WGA) DNA processed for TruSeq Indexed sequencing library preparation as described above. Sequencing data was processed as described above with the exception that a least squares fitting algorithm was used to calculate absolute integer copy number (102).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used is indicated in each figure where relevant. All statistical analyses were performed with Graphpad Prism 8 (GraphPad). K-means clustering and Survival analysis were carried out in R 3.3.0. Error bars show standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM) shown as indicated in the legend and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. * indicates p<0.05; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0001, unless otherwise indicated. ns denotes not significant.

Data and Code Availability

The datasets generated during this study are available through the Sequence Read Archive (SRA; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under the accession numbers PRJNA647834, PRJNA646123, and PRJNA646156. Additional primary data needed for review or to replicate the findings will be made available on request. Code generated during this study is available at https://github.com/rmaddipati79/Maddipati_PDAC_metastasis.git

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Here, we investigate metastatic variation seen clinically in PDAC patients and murine PDAC tumors and identify MYC as a major driver of this heterogeneity.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful advice from Gregory Beatty, Chi Dang, David DeNardo, Rosalie Sears and all members of the Stanger Laboratory. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (CA229803 to B.Z.S., DK109292 to R.M., CA236269 to R.N.), CPRIT (RR190029 to R.M.), AGA (Caroline Craig and Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer to R.M.). J.M. is supported by grants from the Albert Einstein Cancer Center (#305631) and a Ruth L. Kirschstein T32 (CA200561). T.B. is supported by the William C. and Joyce C. O’Neil Charitable Trust, Memorial Sloan Kettering Single Cell Sequencing Initiative. F.N. is supported by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (no. 388785), Cancer Research Society (no. 23383), and the Gattuso-Slaight Personalized Cancer Medicine Fund from Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. Additional support was provided by the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute, the Abramson Cancer Center, and the NIH/Penn Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases.

Conflict of interest statement

B.Z.S. has received research funding from Boehringer-Ingelheim and serves as a consultant to iTeos Therapeutics. E.L.C. has received research funding from Janssen, Merck, and Becton Dickinson.

Footnotes

Additional detailed methods can be found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

References

- 1.McGranahan N, Swanton C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 2017;168(4):613–28 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turajlic S, Xu H, Litchfield K, Rowan A, Chambers T, Lopez JI, et al. Tracking Cancer Evolution Reveals Constrained Routes to Metastases: TRACERx Renal. Cell 2018;173(3):581–94 e12 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter KW, Amin R, Deasy S, Ha NH, Wakefield L. Genetic insights into the morass of metastatic heterogeneity. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18(4):211–23 doi 10.1038/nrc.2017.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gundem G, Van Loo P, Kremeyer B, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JMC, Papaemmanuil E, et al. The evolutionary history of lethal metastatic prostate cancer. Nature 2015;520(7547):353–7 doi 10.1038/nature14347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao ZM, Zhao B, Bai Y, Iamarino A, Gaffney SG, Schlessinger J, et al. Early and multiple origins of metastatic lineages within primary tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016;113(8):2140–5 doi 10.1073/pnas.1525677113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster CC, Pitroda SP, Weichselbaum RR. Definition, Biology, and History of Oligometastatic and Oligoprogressive Disease. Cancer J 2020;26(2):96–9 doi 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pitroda SP, Weichselbaum RR. Integrated molecular and clinical staging defines the spectrum of metastatic cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16(9):581–8 doi 10.1038/s41571-019-0220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;8(6):378–82 doi 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deek MP, Tran PT. Oligometastatic and Oligoprogression Disease and Local Therapies in Prostate Cancer. Cancer J 2020;26(2):137–43 doi 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips R, Shi WY, Deek M, Radwan N, Lim SJ, Antonarakis ES, et al. Outcomes of Observation vs Stereotactic Ablative Radiation for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: The ORIOLE Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6(5):650–9 doi 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, Gan G, Lu X, Bunn PA Jr., et al. Local ablative therapy of oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7(12):1807–14 doi 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182745948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371(11):1039–49 doi 10.1056/NEJMra1404198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller S, Engleitner T, Maresch R, Zukowska M, Lange S, Kaltenbacher T, et al. Evolutionary routes and KRAS dosage define pancreatic cancer phenotypes. Nature 2018;554(7690):62–8 doi 10.1038/nature25459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan-Seng-Yue M, Kim JC, Wilson GW, Ng K, Figueroa EF, O’Kane GM, et al. Transcription phenotypes of pancreatic cancer are driven by genomic events during tumor evolution. Nature genetics 2020;52(2):231–40 doi 10.1038/s41588-019-0566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]