Abstract

Background:

Obesity and comorbid conditions are associated with worse outcomes related to COVID-19. Moreover, social distancing adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic may predict weight gain due to decreased physical activity, increased emotional eating, and social isolation. While early studies suggest that many individuals struggled with weight management during the pandemic, less is known about healthy eating and weight control behaviors among those enrolled in weight loss programs.

Methods:

The present study evaluated weight management efforts among weight loss program participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants’ (N = 55, 90.9% female, 36% white, Mage = 49.8) demographics and body mass index were collected two months prior to the COVID-19 statewide shutdown. During the lockdown, an online survey assessed health behaviors, coping, COVID-19 experiences (e.g., social distancing, loneliness), and weight gain. Logistic regressions examined demographics, health behaviors, and COVID-19 factors as predictors of weight gain.

Results:

Most participants (58%) reported gaining weight during COVID-19. Weight gain was predicted by challenges with the following health behaviors: physical activity, monitoring food intake, choosing healthy foods, and emotional eating. Loneliness and working remotely significantly related to emotional eating, physical activity, and choosing healthy foods.

Conclusions:

Loneliness and working remotely increased the difficulty of weight management behaviors during COVID-19 among weight loss program participants. However, staying active, planning and tracking food consumption, choosing healthy foods, and reducing emotional eating protected against weight gain. Thus, these factors may be key areas for weight management efforts during the pandemic.

Keywords: Obesity, COVID-19, Weight management, Loneliness

Introduction

Perhaps one of the most notable effects of the COVID-19 pandemic is increased psychological stress and social isolation [1,2]. Individuals with obesity are already subject to weight stigma and increased risk of social isolation [3,4], which in turn are predictive of weight gain [4], poor mental health [5], emotional eating [6], and exercise avoidance [7]. Moreover, weight management may be especially difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic, as reduced in-person support, fewer physical activity options, daily routine disruption, and food-focused coping are all associated with weight gain [8,9].

Materials and methods

Subjects

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the present study was developed as an ancillary project to evaluate factors contributing to COVID-19 weight gain and health behavior engagement among adults (n = 55) who had been enrolled in a self-directed, 18-month behavioral weight management trial for 7–13 months before the statewide lockdown [blinded for review]. Participants were adults (21–75 years) with a body mass index (BMI) between 30–50 kg/m2; exclusion criteria included significant medical events (e.g., heart attack), intent to move, and use of medications impacting weight (e.g., corticosteroids). Studies were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and institutional IRB approvals.

Assessments

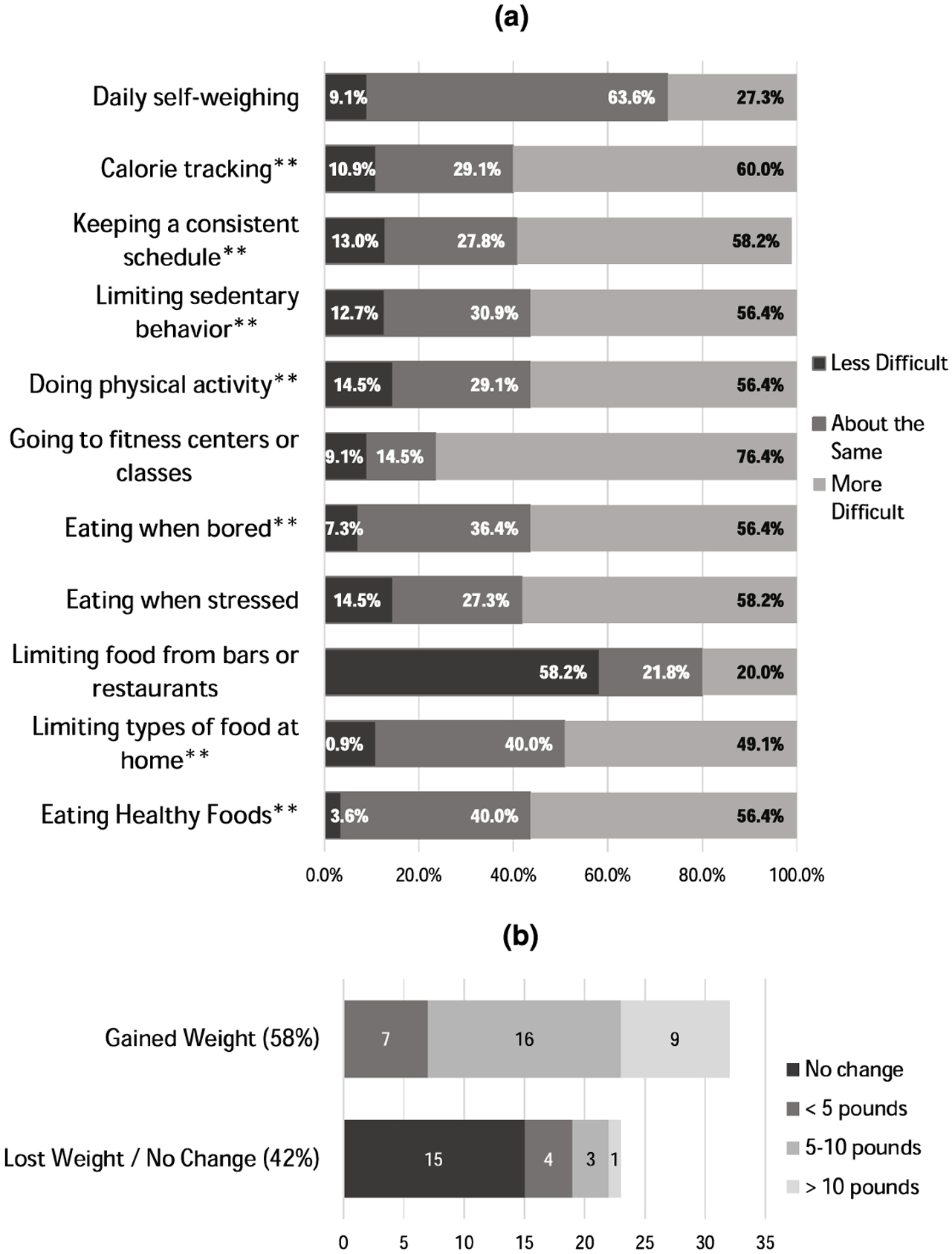

Pre-COVID assessments (July 2019, February 2020) included demographics, height and weight measurements, and the PROMIS Social Isolation Questionnaire (measuring loneliness) [10]. Participants received weekly email invitations throughout May 2020 to participate in the COVID-19 assessment and receive $10 compensation. For COVID-19 assessments, participants completed the PROMIS Questionnaire [10], reported their estimated weight change (dichotomized into lost/stayed same versus gained weight), and reported which weight management behaviors they found more, less, or similarly difficult compared to before the pandemic (Fig. 1a). Participants also indicated whether they had experienced the following pandemic-specific life changes: being an essential worker, working remotely, or experiencing negative financial changes (e.g., job loss, wages decreased). Finally, participants reported social distancing adherence, which was categorized into 3 groups: “social isolation” (no interaction outside the home); “social distancing” (limiting gatherings to <10 people); and “no social distancing” (not restricting social interactions).

Fig. 1.

(a and b) Changes in difficulty of health behaviors and changes in weight since the COVID-19 pandemic began. * = behaviors significantly associated with weight gain during COVID-19.

Data analysis

Fisher’s exact tests and independent samples t-tests evaluated demographic differences associated with COVID-19 weight gain, as well as whether COVID-19 specific events related to weight management behavior engagement. Log-binomial regression examined associations of weight management behaviors with COVID-19 weight change group, with estimates reported as crude relative risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 and SPSS version 26.0.

Results

Fifty seven percent (n = 31) of participants reported gaining weight during COVID-19, while 27% (n = 15) maintained and 15% (n = 8) lost weight (Fig. 1b). There were no between-group differences based on demographics or pre-COVID weight variables (Table 1). Unadjusted relative risk estimates for predictors of COVID-19 weight gain are shown in Table 1. Briefly, difficulties engaging in the following behaviors predicted COVID-19 weight gain: making healthy or low-calorie food choices, eating when bored, limiting types of food at home, being physically active, avoiding sedentary behavior, tracking calorie or food intake, and keeping a consistent schedule (all p < 0.05). Working from home and loneliness were marginally associated with weight gain (p < 0.1), while social distancing, being an essential worker, and financial changes were unrelated. Exploratory analyses assessed whether COVID-19 factors impacted any health behaviors significantly related to weight gain (Table 2). Working from home and loneliness both correlated with eating when bored and eating when stressed (all p > 0.05); moreover, working remotely was associated with difficulty limiting foods at home (p < 0.05), and loneliness correlated with difficulty being physically active (p < 0.05). Being an essential worker, social distancing, and financial changes did not predict difficulty with health behaviors.

Table 1.

Demographic and health behaviors of participants (n = 55), stratified by weight change status during COVID-19.

| Characteristic |

Gained weight (n = 32) Mean (SD) |

Maintained or lost weight (n = 23) Mean (SD) |

p a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Years | 48.6 (13.6) | 51.4 (8.5) | 0.36 |

| Pre-COVID BMI | kg/m2 | 38.3 (6.4) | 36.2 (6.0) | 0.21 |

| Pre-COVID weight loss | kg | 1.3 (4.9) | 1.8 (5.4) | 0.76 |

| n (%) | n (%) | p b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 4 (12.5%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| Female | 28 (87.5%) | 22 (95.7%) | 0.39 | |

| Race | White | 14 (43.8%) | 6 (26.1%) | |

| Nonwhited | 18 (56.3%) | 17 (73.9%) | 0.26 | |

| Education | <Bachelor’s degree | 11 (34.4%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 21 (65.6%) | 13 (56.5%) | 0.58 | |

| Marital status | Married | 14 (43.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

| Not marriede | 18 (56.3%) | 13 (56.5%) | 1.00 | |

| Prediabetes/diabetes history | No | 24 (75.0%) | 15 (65.2%) | |

| Yes | 8 (25.0%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.55 | |

| Behaviors contributing to weight gain | n (%) | n (%) | RR (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choosing healthy, low-calorie foods | More difficult | 23 (71.9%) | 8 (34.8%) | 1.98* (1.13, 3.45) |

| Less/equally difficult | 9 (28.1%) | 15 (65.2%) | Reference | |

| Eating when stressed | More difficult | 22 (68.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | 1.58† (0.94, 2.66) |

| Less/equally difficult | 10 (31.2%) | 13 (56.5%) | Reference | |

| Eating when bored | More difficult | 25 (78.1%) | 6 (26.1%) | 2.77** (1.45, 5.28) |

| Less/equally difficult | 7 (21.9%) | 17 (73.9%) | Reference | |

| Limiting amount or type of food in home | More difficult | 22 (68.8%) | 5 (21.7%) | 2.28** (1.34, 3.87) |

| Less/equally difficult | 10 (31.2%) | 18 (78.3%) | Reference | |

| Being physically active | More difficult | 26 (81.3%) | 5 (21.7%) | 3.35*** (1.65, 6.82) |

| Less/equally difficult | 6 (18.8%) | 18 (78.3%) | Reference | |

| Limiting time sitting or lying down | More difficult | 25 (78.1%) | 6 (26.1%) | 2.77** (1.45, 5.28) |

| Less/equally difficult | 7 (21.9%) | 17 (73.9%) | Reference | |

| Stepping on a scale frequently | More difficult | 11 (34.4%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1.39 (0.91, 2.14) |

| Less/equally difficult | 21 (65.6%) | 19 (82.6%) | Reference | |

| Tracking calorie or food intake | More difficult | 25 (78.1%) | 8 (34.8%) | 2.38** (1.25, 4.52) |

| Less/equally difficult | 7 (21.9%) | 15 (65.2%) | Reference | |

| Limiting meals from bars or restaurants | More difficult | 6 (18.8%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.92 (0.51, 1.67) |

| Less/equally difficult | 26 (81.3%) | 18 (78.3%) | Reference | |

| Going to gyms or fitness classes | More difficult | 26 (81.3%) | 16 (69.6%) | 1.34 (0.71, 2.53) |

| Less/equally difficult | 6 (18.8%) | 7 (30.4%) | Reference | |

| Keeping a consistent schedulef | More difficult | 25 (78.1%) | 7 (31.8%) | 2.46** (1.30, 4.65) |

| Less/equally difficult | 7 (21.9%) | 15 (68.2%) | Reference | |

| COVID-19 specific changes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working from home | Yes | 19 (59.4%) | 8 (34.8%) | 1.52† (0.95, 2.42) |

| No | 13 (40.6%) | 15 (65.2%) | Reference | |

| Essential worker | Yes | 7 (21.9%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.75 (0.41, 1.35) |

| No | 25 (78.1%) | 15 (65.2%) | Reference | |

| Social distancing behaviors | Social isolation | 5 (15.6%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.86 (0.39, 1.88) |

| Social distancing | 20 (62.5%) | 13 (56.5%) | 1.04 (0.60, 1.80) | |

| No social distancing | 7 (21.9%) | 5 (21.7%) | Reference | |

| Financial changes | Yes | 7 (21.9%) | 3 (13.0%) | 1.26 (0.78, 2.04) |

| No | 25 (78.1%) | 20 (87.0%) | Reference | |

| COVID-19 loneliness | Mean (SD) | 18.9 (5.9) | 15.3 (7.1) | 1.04†,g (1.00, 1.07) |

For continuous variables, p-value for independent-samples t-test is reported.

Fisher’s exact test comparing weight change status groups.

Unadjusted relative risk estimates.

Includes African American (n = 31), Asian (n = 1), and American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 2).

Includes single (n = 20) and divorced (n = 11).

n = 54, one participant with missing data. Missingness attributed to error, remaining data included in other analyses.

Relative risk for each one-point increase in continuous predictor.

p<0.1.

p< 0.05.

p<0.01.

p <0.001.

Table 2.

Associations of COVID-19 events with health behaviors (results are p-values for Fisher’s exact tests; for continuous loneliness variable t-test was used).

| Working from home φ |

Financial changes φ |

Essential worker φ |

Social distancing behaviors φ |

Loneliness during COVID-19 (t- test) t |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Making healthy or low-calorie food choices | 0.131 | −0.061 | 0.045 | 0.172 | 0.64 |

| Eating when stressed | 0.316 * | −0.078 | 0.023 | 0.270 | −4.62*** |

| Eating when bored | 0.351 * | −0.060 | 0.045 | 0.276 | −3.14** |

| Limiting the amount or types of food in the house | 0.345 * | 0.197 | −0.111 | 0.087 | −0.47 |

| Being physically active | 0.131 | 0.035 | −0.037 | 0.238 | −3.19 ** |

| Limiting time spent sitting or lying down | 0.131 | 0.035 | −0.037 | 0.191 | −1.58 |

| Writing down or tracking calorie or food intake | 0.059 | −0.096 | −0.083 | 0.106 | −0.63 |

| Keeping a consistent schedulea | 0.075 | 0.104 | 0.009 | 0.142 | −1.29 |

Working from home: Eating when stressed: p = 0.029.

Eating when bored: p = 0.014.

Limiting foods in the household: p = 0.015.

COVID-19 loneliness: Eating when stressed: p < 0.001.

Eating when bored: p = 0.002.

Being physically active: p = 0.002.

n = 54 due to one participant with missing data. Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables; phi was used to describe effect size. Loneliness was a continuous variable; as such, a t-test was used. All Levene’s tests indicated equality of variance.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Discussion

Within three months of the COVID-19 statewide lockdown, 58% of participants currently enrolled in a weight loss program had gained weight, with 16% gaining ≥10 pounds. Eight health behaviors correlated with weight gain during this time, from which four overarching “themes” emerged: (1) being active (limiting sedentary behavior, maintaining physical activity); (2) planning and tracking (calorie tracking, keeping a consistent schedule); (3) choosing healthy foods (eating healthier foods, limiting unhealthy foods at home); and (4) reducing emotional eating (eating when stressed, eating when bored). For those working remotely, planning snack times or identifying stress-relieving activities not involving food may help them manage weight gain. Moreover, individuals struggling with loneliness during this time may be susceptible to emotional eating and difficulty being physically active. This is consistent with pre-pandemic studies suggesting that loneliness predicts reduced physical activity, which is partially mediated by emotion regulation [11]. While our small sample size warrants study replication, additional weight gain during this time may increase risk for future health concerns, perceived treatment inefficacy, or hopelessness about one’s ability to manage weight. These results highlight the increased challenges individuals face in weight management efforts due to COVID-19 restrictions and suggest a need for intervention strategies that address these factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01DK106041 funded by the National Institutes of Health. Graduate trainee and ancillary study funding were provided through 5T32HS013852-17 funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Finally, we thank the participants for their time and participation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Registration: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02959021. The parent trial for this study is registered, the ancillary study was developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and was not pre-registered.

Contributor Information

Alena C. Borgatti, a Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; b Department of Psychology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States.

Camille R. Schneider-Worthington, Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Lindsay M. Stager, Department of Psychology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Olivia M. Krantz, Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Andrea L. Davis, a Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States; b Department of Psychology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Magdalene Blevins, Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States.

Carrie R. Howell, Department of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Gareth R. Dutton, Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

References

- [1].Banerjee D, Rai M. Social isolation in Covid-19: the impact of loneliness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020;66(6):525–7. 10.1177/0020764020922269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, van der Roest H, de Vries DH. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among Dutch older adults. J Gerontol B 2020:1–7. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa11 [Published online 5 August 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jung FU, Luck-Sikorski C. Overweight and lonely? A representative study on loneliness in obese people and its determinants. Obes Facts 2019;12(4):440–7. 10.1159/000500095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hunger JM, Major B, Blodorn A, Miller CT. Weighed down by stigma: how weight-based social identity threat contributes to weight gain and poor health. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2015;9(6):255–68. 10.1111/spc3.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Emmer C, Bosnjak M, Mata J. The association between weight stigma and mental health: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2020;21(1):e12935. 10.1111/obr.12935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mason TB. Loneliness, eating, and body mass index in parent-adolescent dyads from the family life, activity, sun, health, and eating study. Pers Relatsh 2020;27 (2):420–32. 10.1111/pere.12321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pels F, Kleinert J. Loneliness and physical activity: a systematic review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2016;9(1):231–60. 10.1080/1750984X.2016.1177849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zeigler Z, Forbes B, Lopez B, Pedersen G, Welty J, Deyo A, Kerekes M. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Res Clin Pract 2020;14:210–6. 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Almandoz JP, Xie L, Schellinger JN, Mathew MS, Gazda C, Ofori A, Kukreja S, Messiah SE. Impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on weight-related behaviours among patients with obesity. Clin Obes 2020:e12386. 10.1111/cob.12386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hahn EA, DeWalt DA, Bode RK, Garcia SF, DeVellis RF, Correia H, Cella D, PROMIS Cooperative Group. New English and Spanish social health measures will facilitate evaluating health determinants. Health Psychol 2014;33:490–9. 10.1037/hea0000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health Psychol 2009;28(3):354–63. 10.1037/a0014400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]