Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants have raised concerns about levels of immunity to variant Spike proteins after prior SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. Here, we report distinct cross-reactivity of Wuhan-HA-1 (WA1) induced antibodies upon BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection. We show that neutralizing antibodies against WA1 strongly correlate with Delta neutralization, and that SARS-CoV-2 infection-induced antibodies have better neutralization capability for the Delta variant compared to vaccination.

We measured the magnitude and breadth of Spike antibody responses against the original WA1 and 3 variants (Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351) and Delta (B.1.617.2) of SARS-CoV-2 in 3 cohorts: (i) SARS-CoV-2 naïve recipients of two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccine (day 90 post 1st dose; n=55); (ii) COVID-19 convalescent patients who received the 1st dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine at 6-10 months post symptom onset (day 90 post 1st dose; n=5); (iii) COVID-19 convalescent patients (n=23) at peak post infection at a median of 2 months post symptom onset. We examined the levels and breadth of anti-Spike antibodies and their neutralizing ability against WA1 and the variants Alpha, Beta and Delta, which differ by one to three amino acids (AA) within the receptor-binding domain (RBD) (Figure 1A).

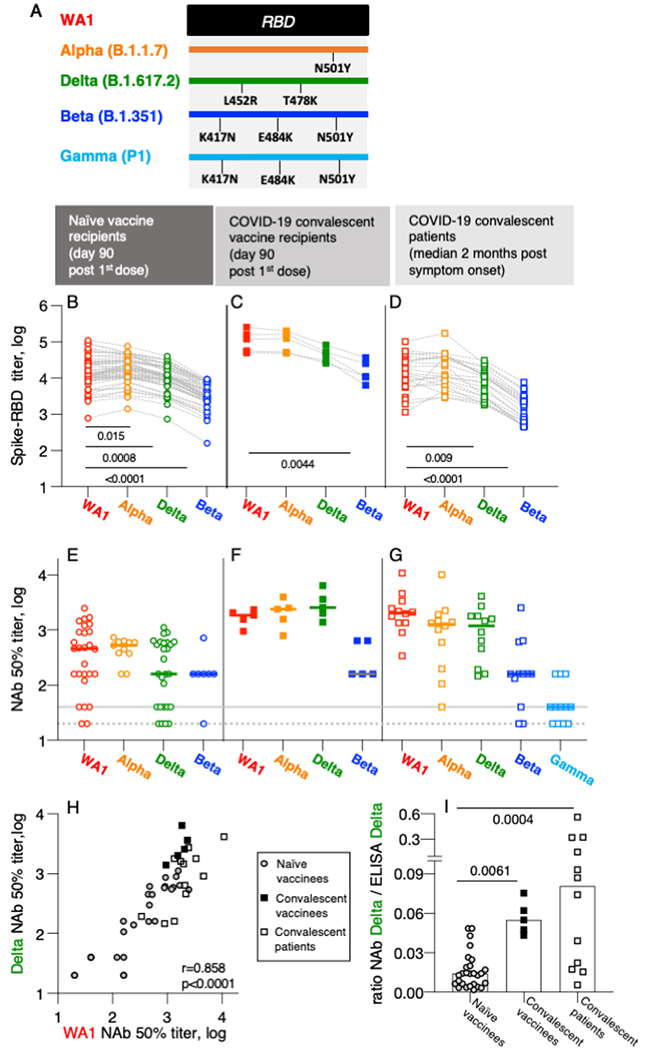

Figure 1. Anti-Spike antibody characterization in BNT162b2 mRNA vaccinated and CoV-2 infected persons.

(A) The cartoon depicts AA changes in RBD (AA 332-532). Beta and Gamma share the identical RBD but differ in several AA within Spike used in neutralization assay. (B-D) Wuhan-Spike induced antibodies were measured by in-house ELISA using a panel of purified Spike-RBD proteins. (B, C) CoV-2 naïve volunteers [1] and COVID-19 convalescent patients [1] received the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and were analyzed at day 90. The convalescent vaccine recipients [1] had detectable Spike-RBD antibodies (median titer 2.8 log, range 2.6-3.9) at the day of the 1st dose. (D) SARS-CoV-2 infected patients [16, 17] were analyzed at a median of 2 months post symptom onset. Comparison between the groups were made using ANOVA Friedmann’s multiple comparison test. (E-G) Neutralization was performed with the samples shown in panels B-D using a pseudotyped HIVNLΔEnv-Nanoluc assay carrying a panel of Spike (AA 1-1254) proteins. Threshold of detection in gray solid line; threshold of quantification in grey dotted line. (H) Correlation of NAb to WA1 and Delta in the 3 cohorts described in panels E to G. Spearman r and p value are given. (I) Ratios of Delta NAb (from panels E-G) and Delta antibody titers (panel B-D) for the different cohorts were calculated using linear values. The p values are from ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test.

The study participants include patients and volunteers are described in NCT04408209 and NCT04743388. CoV-2 naïve volunteers and COVID-19 convalescent patient received 2 doses of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine at day 1 and 21, respectively [1]. The convalescent vaccine recipients received 1st dose at 6-10 months post symptom onset [1]. SARS-CoV-2 infected patients analyzed at a median of 2 months post symptom onset have been described [16, 17]. In-house ELISA using a panel of purified Spike-RBD proteins (AA 319-525) were detailed elsewhere [5, 15]. Neutralization was performed using a pseudotyped HIVNLΔEnv-Nanoluc assay [18, 19] carrying a panel of Spike (AA 1-1254) proteins as described [5, 15, 16]. Statistical analyses were performed using ANOVA and Spearman correlation (GraphPad Prism Version 9.0.2 X; GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA).

All three cohorts showed robust humoral response to WA1 Spike-RBD. Similar antibody levels were detected in the naïve BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine recipients at day 90 and in the COVID-19 convalescent patients (2 months post-infection). A 12-x fold higher Ab level was detected in the convalescent vaccinees [1], as a result of a strong anamnestic response in this cohort [1–4] (Figure 1B–D). Compared to the responses against WA1, the vaccine-induced antibodies showed significantly lower recognition of Alpha and Delta Spike-RBD and greatly reduced binding of Beta Spike-RBD in the naïve vaccinees (Figure 1B). In contrast, the Spike-RBD antibodies in the SARS-CoV-2 convalescent vaccine recipients (Figure 1C) showed similar strong binding to Beta and Delta indicating some improved breadth. Despite the increased humoral responses, recognition of Beta Spike-RBD was significantly reduced (Figure 1C). We further compared the anti-Spike-antibody breadth in a cohort of COVID-19 convalescent patients (Figure 1D). We noted a similar ranking of responses as in the cohort of naïve vaccine recipients with reduced recognition of Delta and Beta Spike-RBD. Together, our data suggest a strong benefit of vaccination for COVID-19 convalescent patients. Our data further point to two AA changes (K417N and E484K; Figure 1A), which play a key role for RBD recognition. These data mirror our recent findings from non-human primates which received WA1 Spike based DNA vaccines [5]. Importantly, increased Spike-RBD antibody magnitude cannot compensate for this. Thus, a booster vaccination including different variants may be beneficial and should be considered.

Next, we tested the neutralizing capability of the Spike antibodies in the different groups (Figure 1E–G). Sera were tested for their ability to neutralize infection by reporter viruses pseudotyped with different Spike variants. Analysis of both the naive vaccine recipients (Figure 1E; n=27) and the convalescent vaccine recipients (Figure 1F; n=5) showed that WA1, Alpha and Delta Spike pseudotyped viruses were most susceptible. Similar data were found in the convalescent cohort (Figure 1G; n=12). A drastic reduction in the ability to neutralize Beta was found in all the groups. These data were further supported by the testing of neutralization of Gamma which shares with Beta the same AA changes in RBD but differs in several AA in Spike (Figure 1A). The convalescent cohort (Figure 1G) also showed a strong reduction in the neutralization ability of Gamma. These data support the key role of the amino acids K417N and E484K (Figure 1A) for both binding and neutralization by WA1-induced antibodies. Our data on the cross-reactive recognition of Spike variants are in overall agreement with other recent reports analyzing the Moderna mRNA-1273, Pfizer BNT162b2 or AstraZeneca vaccines in healthy vaccine recipients or in COVID-19 convalescent vaccine recipients [6–11] and in our DNA vaccine study in nonhuman primates [5].

Because of the practical importance of the ability of WA1-induced antibodies to control infection by the Delta variant, we compared neutralization abilities of antibodies against WA1 and Delta in the 3 cohorts (Figure 1H). We found a strong direct correlation (Spearman; r = 0.8586, p<0.0001), supporting the notion that individuals with robust NAb against WA1 also strongly neutralize Delta. Recent findings of breakthrough infections in individuals with vaccine- or infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 immunity [12–14] by the circulating Delta strain may occur in individuals with low anti-WA1 antibodies. Our data indicate that a WA1-based booster vaccination will greatly improve anti-Delta immune response.

To further characterize the WA1 vaccine-induced and the infection-induced Delta-specific antibodies, we compared the ratio of the respective NAb and binding antibodies in the three cohorts (Figure 1I). Interestingly, compared to the naïve vaccine recipients, we found significant higher ratios in the convalescent cohort and in the convalescent vaccine recipients. These data support the conclusion that antibodies induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection have better Delta-specific neutralization function. The subsequent vaccination of the convalescent patients was able to increase the level and maintain the breadth of anti-Delta neutralizing Ab.

The report presented here shows a side-by-side comparison of characteristics of Spike antibodies induced upon BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination, upon CoV-2 infection or a combination thereof using the same methodologies. We found that anti-Spike antibodies from the vaccine recipients (naïve and convalescent) and SARS-CoV-2 convalescent patients show a strong ability to recognize and neutralize the autologous WA1, as well as the Alpha and Delta Spike variants but that they show greatly impaired recognition of Beta, in agreement with others [6–11], pointing to the importance of AA changes within RBD. Recently emerging Variants of Concern show a multitude of such changes which will likely affect NAb function of the WA1-induced antibodies. Interestingly, our data further showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection induced antibodies show better neutralization capability of the Delta variant [6–11]. This finding points to subtle but critical differences in antibody development perhaps guided through continuous antigen exposure upon infection whereas vaccination provides a limited number of short-lived exposures.

SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccination using WA1 is being implemented in many countries to increase the anti-Spike antibody titers, and our data support its merit to improve anti-WA1 antibody magnitude and thereby increased ability to recognize Delta. However, our data also show that the magnitude alone is not sufficient to neutralize effectively current SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Thus, future booster vaccinations with variant Spike vaccines, including Delta and Beta, should be considered to increase the breadth of the immune responses. The nucleic acid vaccine platform offers the necessary versatility to rapidly adapt to emerging variants of concern, which need to be considered in the future to improve vaccine efficacy.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Esposito (Protein Expression lab; NCI) for SARS-CoV-2 Spike-RBD proteins; members of the Felber and Pavlakis labs for discussion, and T. Jones for assistance. This work was supported by funding from the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research to G.N.P. and B.K.F. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1002/ajh.26380

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

REFERENCES

- [1].Bergamaschi C, Terpos E, Rosati M, Angel M, Bear J, Stellas D, et al. Systemic IL-15, IFN-gamma, and IP-10/CXCL10 signature associated with effective immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine recipients. Cell Rep. 2021;36 109504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lozano-Ojalvo D, Camara C, Lopez-Granados E, Nozal P, Del Pino-Molina L, Bravo-Gallego LY, et al. Differential effects of the second SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine dose on T cell immunity in naive and COVID-19 recovered individuals. Cell Rep. 2021;36:109570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kremsner PG, Mann P, Kroidl A, Leroux-Roels I, Schindler C, Gabor JJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 : A phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;August 10. pii: 10.1007/s00508-021-01922-y. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01922-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Urbanowicz RA, Tsoleridis T, Jackson HJ, Cusin L, Duncan JD, Chappell JG, et al. Two doses of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine enhances antibody responses to variants in individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Transl Med. 2021;September;13(609):eabj0847. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj0847. Epub 2021 Aug 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rosati M, Agarwal A, Hu X, Devasundaram S, Stellas D, Chowdhury B, et al. Control of SARS-CoV-2 infection after Spike DNA or Spike DNA+Protein co-immunization in rhesus macaques PLOS Path. 2021;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pegu A, O’Connell S, Schmidt SD, O’Dell S, Talana CA, Lai L, et al. Durability of mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;August 12. pii: science.abj4176. doi: 10.1126/science.abj4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rajah MM, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596:276–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Betton M, Livrozet M, Planas D, Fayol A, Monel B, Vedie B, et al. Sera neutralizing activities against SARS-CoV-2 and multiple variants six month after hospitalization for COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2021; April 14. pii: 6225251. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Muecksch F, Barnes CO, Finkin S, et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature. 2021;592:616–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Collier DA, De Marco A, Ferreira I, Meng B, Datir RP, Walls AC, et al. Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 to mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies. Nature. 2021;593:136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, Amit S, Lipsitch M, Cohen C, et al. Covid-19 Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated Health Care Workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;July 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Luo CH, Morris CP, Sachithanandham J, Amadi A, Gaston D, Li M, et al. Infection with the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant is Associated with Higher Infectious Virus Loads Compared to the Alpha Variant in both Unvaccinated and Vaccinated Individuals. medRxiv. 2021;August 20. doi: 10.1101/2021.08.15.21262077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Brown CM, Vostok J, Johnson H, Burns M, Gharpure R, Sami S, et al. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 Infections, Including COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Infections, Associated with Large Public Gatherings - Barnstable County, Massachusetts, July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1059–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Farinholt T, Doddapaneni H, Qin X, Menon V, Meng Q, Metcalf G, et al. Transmission event of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant reveals multiple vaccine breakthrough infections. medRxiv. 2021; July 12. doi: 10.1101/2021.06.28.21258780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]