Abstract

Background

In recent years, evidence is accumulating that cancer cells develop strategies to escape immune recognition. HLA class I HC down-regulation is one of the most investigated. In addition, different HLA haplotypes are known to correlate to both risk of acquiring diseases and also prognosis in survival of disease or cancer. We have previously shown that patients with serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary in advanced surgical stage disease have a particularly poor prognosis if they carry the HLA-A02* genotype. We aimed to study the relationship between HLA-A02* genotype in these patients and the subsequent HLA class I HC protein product defects in the tumour tissue.

Materials and methods

One hundred and sixty-two paraffin-embedded tumour lesions obtained from Swedish women with epithelial ovarian cancer were stained with HLA class I heavy chain (HC) and β2-microglobulin (β2-m)-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAb). Healthy ovary and tonsil tissue served as a control. The HLA genotype of these patients was determined by PCR/sequence-specific primer method. The probability of survival was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the hazard ratio (HR) was estimated using proportional hazard regression.

Results

Immunohistochemical staining of ovarian cancer lesions with mAb showed a significantly higher frequency of HLA class I HC and β2-m down-regulation in patients with worse prognosis (WP) than in those with better prognosis. In univariate analysis, both HLA class I HC down-regulation in ovarian cancer lesions and WP were associated with poor survival. In multivariate Cox-analysis, the WP group (all with an HLA-A02* genotype) had a significant higher HR to HLA class I HC down-regulation.

Conclusions

HLA-A02* is a valuable prognostic bio-marker in epithelial ovarian cancer. HLA class I HC loss and/or down-regulation was significantly more frequent in tumour tissues from HLA-A02* positive patients with serous adenocarcinoma surgical stage III–IV. In multivariate analysis, we show that the prognostic impact is reasonably correlated to the HLA genetic rather than to the expression of its protein products.

Keywords: HLA-A02*, Ovarian cancer, Serous adenocarcinoma, Immunohistochemistry, MHC, Prognosis

Introduction

EOC consists of different histological tumour entities where the most important are serous, endometrioid, mucinous and clear cell carcinoma [1]. Serous histology accounts for approximately 45–55% of EOC cases and is the most frequent type in Sweden. More than 75% of the cases are detected at late disease stage (stages III–IV) when they are inoperable. Despite excellent initial responses, most patients [2] relapse early after treatment [3, 4]. After the development of chemotherapy-resistant disease, the majority of patients with serous EOC will succumb to their disease [5, 6]. The development of new therapies for serous EOC is central to improving the prognosis of this cancer. Immune-based therapies have shown promise in the treatment of EOC, but more work is needed to understand the role of immune surveillance in ovarian cancer progression [7].

Recently, HLA-A02* genotype has been described as an independent poor prognostic factor in Swedish women with advanced EOC of serous histology [8–11]. Different HLA haplotypes have been linked to patient prognosis in several types of cancers such as lung carcinoma [12, 13], malignant melanoma [14] and head and neck squamous carcinoma [15]. In addition, the HLA phenotype has been correlated with different outcomes in immune-based therapies in melanoma [16–20], renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [21–23], cervical carcinoma [24, 25] and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) [26].

The prognostic relationship between high malignancy and HLA-A02* challenges us to analyse underlying mechanisms. In this respect, we focused on that loss or down-regulation of HLA class I HC has been reported in tumour lesions of distinct histology [27, 28], including EOC [29]. Defects in HLA class I expression may play a role of tumour progression through avoidance of detection and elimination by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) [30] resulting in a worse clinical outcome.

The purpose of this study is to determine whether the negative prognostic relationship of HLA-A02* genotype of patients with serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary in stage III–IV is associated with a higher frequency of HLA class I and β2-m defects in the tumour.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patient information and histopathology samples were accessed with approval of the local ethics committee. One hundred and eighty-two patients admitted to the gynaecological Oncology unit at the Karolinska University Hospital Department of Oncology between 1995 and 2004 were initially considered for inclusion in this study. Twenty of these patients have been previously described [8]. The diagnosis of EOC as well as tumour stage and grade were confirmed by histopathology of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour specimens. The HLA genotype of the patients was the primary inclusion criteria. After inclusion, pertinent clinical information was entered into a database. For 162 patients, FFPE tumour tissues were available for immunohistochemical analysis. The date of diagnosis, FIGO stage (I–IV), histological type of the patient’s epithelial ovarian carcinoma (serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, undifferentiated, mixed epithelial, unclassified) and grade of differentiation (well, G1; moderately, G2; poorly, G3 differentiated) were recorded. Non-epithelial ovarian cancers, borderline ovarian tumours, cancers of genital tract (except ovaries) and of extra genital localization were excluded from the analysis [31, 32]. FFPE healthy tissue from ovary (two cases) and tonsil (two cases) were used as controls. One block of FFPE tissue from each case and control was serially cut into 4-μm-thick slices and mounted onto super frost slides.

Patients groups

Patients have been grouped by surgical stage, histopathology and HLA-A genotype according to our previous findings [8, 10]. Worst prognosis (WP) is defined by stage III–IV, serous adenocarcinoma HLA-A02*. Better prognosis (BP) includes stage I–II, all the histological type and all HLA-A genotypes including HLA-A02*.

Sample preparation for DNA extraction

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained by separating blood samples on lymphoprep according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway). Genomic DNA was extracted from isolated lymphocytes using “Roche High-Pure DNA extraction kit procedures 030625” (Roche, Molecular Biochemicals, and Manheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Two hundred microlitres/sample was treated with 1 ml extraction buffer, mixed, incubated for 30 min at 80°C and then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000×g. Supernatant was collected into a new reaction tube with 400 μl binding buffer and 80 μl proteinase K. This mixture was further incubated for 10 min at 72°C adding 200 μl isopropanol and then loaded onto a filter tube placed on a collection tube and centrifuged for 1 min at 5,000×g. These samples were washed twice with 450 μl wash buffer at 5,000×g centrifugation for 2 min. After the final wash step, samples were dried by a 10-min centrifugation at max speed. DNA in the filter was then eluted with 50 μl elution buffer into a new reaction tube by a 1-min centrifugation at 5,000×g. Finally, the DNA amount and purity were determined by NanoDrop technology (GE lifesciences, Uppsala, Sweden).

HLA genotyping

DNA analysis was used for HLA genotyping of both FFPE material from deceased patients and of peripheral blood samples from consented patients, and HLA genotyping in FFPE extracted DNA was performed using primers only for HLA-A02* (provided by Olle Olerup, SSP AB, Saltsjöbaden, Sweden) as previously described [8]. For the DNA extracted from peripheral blood, complete allele HLA genotype was performed using the Olerup SSP HLA Typing Kit (Olerup SSP AB, Stockholm, Sweden) [10]. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis at 150 V for 30 min on a 3% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. An additional PCR was performed with primers for the control housekeeping gene S14.

Monoclonal antibodies for immunohistochemistry

The mAb HCA-2 (HCA), which recognizes b2m-free HLA-A (excluding -A24), -B7301 and -G heavy chains (1, 2), the mAb HC-10, which recognizes b2m-free HLA-A3, -A10, -A28, -A29, -A30, -A31, -A32, -A33 and-B (excluding -B5702, -B5804 and -B73) heavy chains (1–3) and the b2m-specific mAb L368 (4) were developed and characterized as described [33–36].

Immunohistochemical staining and analysis

Tissue sections were de-paraffined, re-hydrated and rinsed with water. The samples were heated in a microwave for 20 min for antigen retrieval. The slides were left for 30 min in 0.5% H2O2 in water, finally rinsed in water and twice for 5 min in tris-buffered saline (TBS). Blocking was performed with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS in a moist chamber for 30 min before the sections were stained with the primary antibody at +8°C over night. Avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (ABC) kit (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories) was used for antigen detection. The sections were rinsed three times for 10 min each in TBS followed by incubation with the secondary antibody for 40 min. After three washing steps for three min in TBS, an ABC reagent was added for 40 min before the slides were again rinsed three times for 10 min in TBS. The immunolabelling was developed with the chromogen 3′-diaminobenzydine (15 mg/50 ml TBS for 6 min), and haematoxylin was applied as a counter stain. Staining of tissue sections with isotypes lgG1, IgG2a mouse mAb or secondary antibody, respectively, served as negative controls. FFPE healthy ovarian tissues, obtained from two oophorhysterectomies due to uterine myomas as well as tonsillar tissues, were used as positive controls (Table 1). When present, healthy epithelium adjacent to tumour tissue and/or infiltrating lymphocytes in the stroma were used as internal control.

Table 1.

IHC staining of healthy ovarian tissue by antibodies against receptors for the MHC

| Antibody/target antigen | Epithelium | Tubar epithelium | Follicle | Endothelium | Mononuclear cells | Fibroblasts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC10/MHC class I heavy chain | Strongly positive | Negative | Positive | Strongly positive | Strongly positive | Negative |

| HCA/MHC class I heavy chain | Strongly positive | Positive | Strongly positive | Strongly positive | Strongly positive | Negative |

| L368/β2 microglobulin | Strongly positive | Weakly positive | Positive | Positive | Strongly positive | Negative |

The percentage of stained malignant cells in each lesion was evaluated twice by two investigators (EA and GM). In case of discordant results (more than two score levels), a third evaluator (AH) was consulted and consensus was made. Scoring to ensure detection of any significant differences was performed as follows: 0 (0%), 1 (1–25%), 2 (26–50%), 3 (51–75%) or 4 (76–100%) [37, 38]. This extended evaluation system gave the possibility to merge the results in fewer, but relevant, groups for statistical analysis. In parallel, the staining intensity was also evaluated and separately scored as weak, moderate or intense, but statistical analysis revealed no patterns or significant differences (data not shown).

Statistics

The χ2 test was used to examine patient characteristics for discrete categorical variables or factors. Time to death from any cause was defined as the primary end point in the study. Survival time for deceased patients was calculated using the date of first diagnosis to the date of death. For surviving patients, the survival time was calculated from the date of first diagnosis to the date of the last clinical follow-up. HLA-A02* genotype was scored as 1 and HLA-otherwise as 0. Cumulative survival plots and time-to-event Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed with the log-rank test applied to detect univariate differences between groups. Diagnostic data were collected during the year 1995–2004 and were censored at 1 June 2010. Univariate Cox regression analyses were performed for each prognostic factor we studied. These factors were clinical stage, histological type and HLA-A02* genotype grouped in WP and BP. Results from the Cox regression models are presented as Hazard Ratios (HR) together with 95% confidence intervals (CI). P values from the regression model refer to the Wald test. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed including binary coding of all factors (WP vs. BP, HC-10, HCA, L368, low vs. high staining percentages). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Interactions were evaluated by including product terms in the model. All analyses were performed with program StatView for Windows, SAS Institute Inc. Version 5.0.1.

Results

Patient population

The patients’ characteristics and the HLA genotype are summarized in Table 2. Age, stage, grade of differentiation and histology distribution of the population did not differ from the figures released by the FIGO annual report for European countries [39]. There is no significant difference in the distribution of patients younger than 60 in the two prognostic groups (P value 0.12). Forty-seven serous adenocarcinoma patients surgical stages (III–IV) HLA-A02* genotype were grouped for statistical analysis as worse prognosis (WP). The remaining 115 patients were categorized as BP group. Only four (9%) of the WP patients received radical surgery compared to 51 (44%) of the BP. The majority of the patients received platinum-based chemotherapy (97% vs. 92%) but 67% of the patients with WP required more than six therapy cycles compared to only 29% of the BP group.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the cohort and groups

| Cohorta | WPa | BPa,c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Patients eligible for analysis | 162 | 100 | 47 | 29 | 115 | 71 |

| Age median (range) | 60 | 30–86 | 61 | 36–83 | 58 | 30–86 |

| Age <60 | 88 | 50.8 | 21 | 46b | 67 | 58b |

| HLA-A2 positive | 92 | 57 | 47 | 100 | 45 | 40 |

| Surgical staging | ||||||

| I a, b, c | 38 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 38 (22) | 33 |

| II a, b, c | 17 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 15 (9) | 13 |

| III a, b, c | 82 | 51 | 32 | 68 | 52 (9) | 45 |

| IV | 25 | 15 | 15 | 32 | 10 (5) | 9 |

| Stage merged | ||||||

| A | 53 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 53 (31) | 46 |

| B | 109 | 67 | 47 | 100 | 62 (14) | 54 |

| Histopathology | ||||||

| Serous | 87 | 52 | 47 | 100 | 40 (6d) | 35 |

| Endometrioid | 45 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 45 (24) | 39 |

| Mucinous | 14 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 14 (7) | 12 |

| Clear cells | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 10 (7) | 9 |

| Others (mixed epithelial, undifferentiated) | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 (1) | 5 |

| Grade | ||||||

| 1 | 21 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 20 (11) | 17 |

| 2 | 34 | 21 | 10 | 21 | 24 (12) | 21 |

| 3 | 103 | 63 | 35 | 75 | 68 (21) | 59 |

| Unknown | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 (1) | 3 |

| Treatments | ||||||

| Primary surgery | 138 | 85 | 35 | 76 | 103 | 89 |

| Radical surgery | 55 | 34 | 4 | 9 | 51 | 44 |

| Secondary surgery | 22 | 14 | 8 | 17 | 14 | 12 |

| Platinum-based chemotherapy | 152 | 94 | 45 | 97 | 107 | 92 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | ||||||

| 6 and less | 97 | 60 | 15 | 33 | 82 | 71 |

| More than 6 | 65 | 40 | 31 | 67 | 34 | 29 |

| Radiotherapy | 7 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

Cohort: all patients included in the study. WP worst prognosis group, BP better prognosis group

Difference in % between WP and BP is NS

HLA-A02* genotype in paran-theses

HLA-A02* genotype patients: 4 in stage I and 2 in stage II

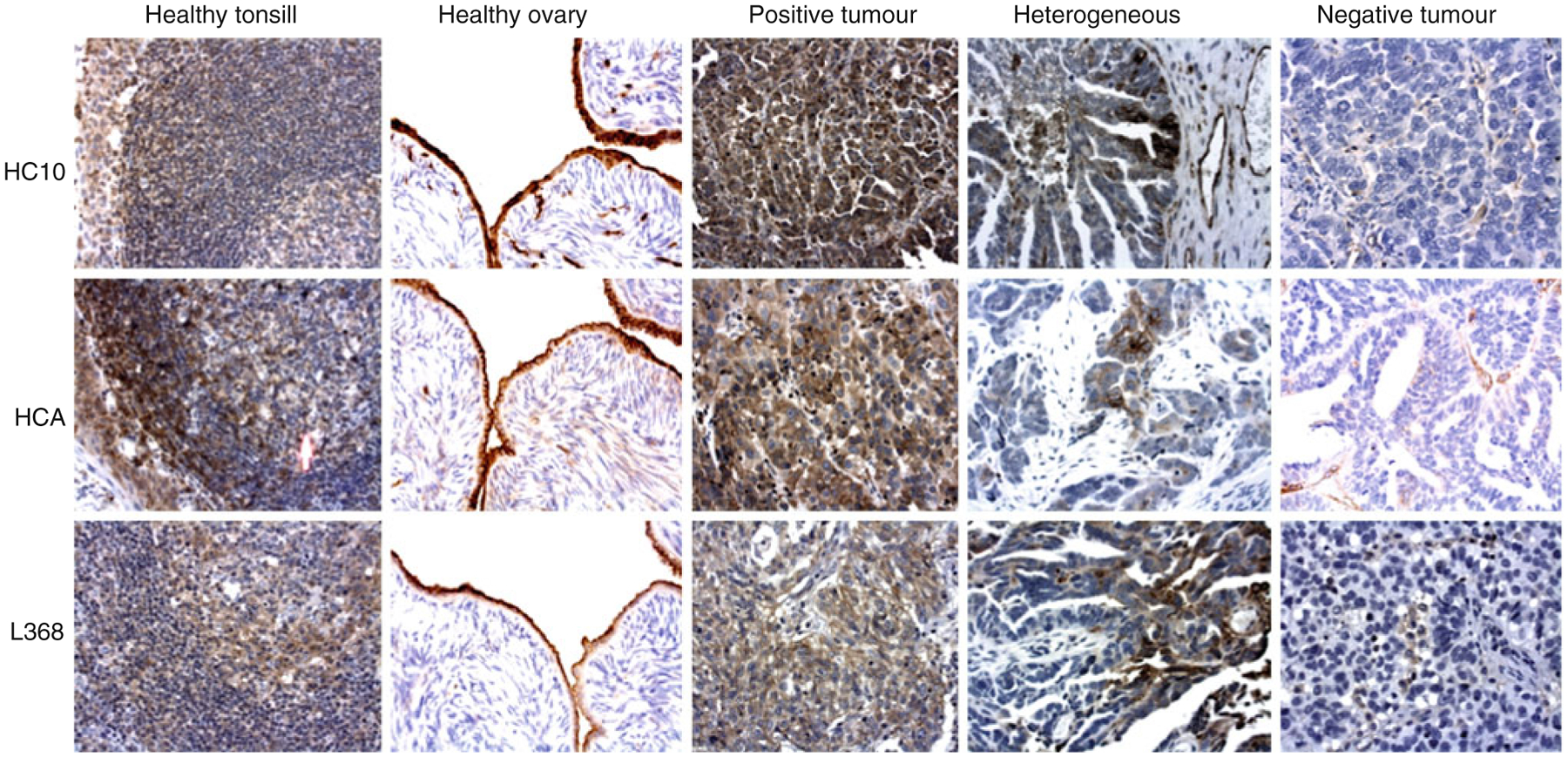

HLA class I HC and β2-m expression in healthy ovaries

The staining of the tissues from two healthy ovaries and two healthy tonsils with HLA class I HC and β2-m mAb served as positive controls. Immunoreactive expression was detected in all cells of the parenchyma (follicle and tuba epithelium), endothelium and in the inflammatory cells of the stroma. In contrast, the staining of stromal fibroblasts was negative for the mAb HC10 and was only weakly positive for HCA mAb (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of immunohistochemical staining patterns of different MHC components in healthy tissues using the mAbs HC-10 and HCA detecting the HLA class I HC and mAb L368 detecting β2-m (reading the Wgure horizontally). Vertically and from left to right; healthy tonsil and ovary, tumour tissue with the majority of stained cells (positive), heterogeneous and negative (clearly positive infiltrating cells in the stroma) staining. Original magnification ×400

HLA class I HC and β2m expression in tumour tissue

Forty-seven lesions from the WP group and 115 lesions from the BP group were stained with the HC-10, HCA and L368 mAbs (Table 3) and evaluated by five grade scoring system. Most lesions in the BP group were score 3 or 4. On the contrary, most lesions in the WP group were grade 0, 1 or 2.

Table 3.

Percentage of tumours stained with antibodies detecting MHC molecules

| Antibodies detecting MHC molecules on tumour tissue | Scoring | Cohort (%) | WP (%) | BP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 162 | 47 | 115 | |

| HC-10 | 0 | 12.3 | 21 | 8.6 |

| 1 | 6.1 | 10 | 4.3 | |

| 2 | 8.6 | 17 | 5.2 | |

| 3 | 36.4 | 26 | 40.5 | |

| 4 | 36.4 | 26 | 40.5 | |

| HCA | 0 | 17.9 | 27.6 | 14 |

| 1 | 9.8 | 12.7 | 8.6 | |

| 2 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 13 | |

| 3 | 43.2 | 34 | 47 | |

| 4 | 16.2 | 13 | 17.4 | |

| L368 | 0 | 24 | 34 | 20.2 |

| 1 | 18.5 | 28 | 14.7 | |

| 2 | 21.6 | 19 | 22.6 | |

| 3 | 19.1 | 13 | 21.7 | |

| 4 | 16.6 | 6 | 20.8 |

Scores were summarized in ≥50% (high) and <50% (low) (Table 4). In the WP group, the numbers of lesions exhibiting a low staining by mAb HC10, HCA and L368 were significantly higher than in the BP group (HC10: 48% vs. 19%; HCA: 53% vs. 36%; L368: 81% vs. 57.5%). Interestingly, 40 tumours did not stain for mAb L368, but scored high for HC10 and HCA. They were equally distributed between the BP and WP groups. In the BP group, 45 patients were HLA-A02*. Forty-three of them were distinguished by a greater percentage of high staining compared to BP with other HLA genotypes.

Table 4.

Distribution of mAbs detecting <50% or equal/more than 50% MHC molecules on the tumour tissue

| Antibodies detecting MHC molecules on tumour tissue | Cumulative % of positive tumour tissuea | Cohort | WP | BP (HLA-A02*)b | P (χ2)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 162% | 47% | 115 (45)% | ||

| HC-10 | <50% (low) | 27 | 48 | 19 (6.5) | <0.001 (14.6) |

| ≥50% (high) | 73 | 52 | 81 (93.5) | <0.001 (18.8) | |

| HCA | <50% (low) | 41 | 53 | 35.5 (11) | 0.04 (4.5) |

| ≥50% (high) | 59 | 47 | 64 (8.9) | 0.02 (5.1) | |

| L368 | <50% (low) | 64 | 81 | 57.5 (30.4) | 0.02 (5.7) |

| ≥50% (high) | 36 | 19 | 42.5 (69.6) | <0.001 (11.3) |

<50% staining scores (low) and >50% staining scores (high)

In paranthesis are presented the fraction of HLA-A02* patients

Comparison between % of WP and BP for low and high respectively. P values and χ2

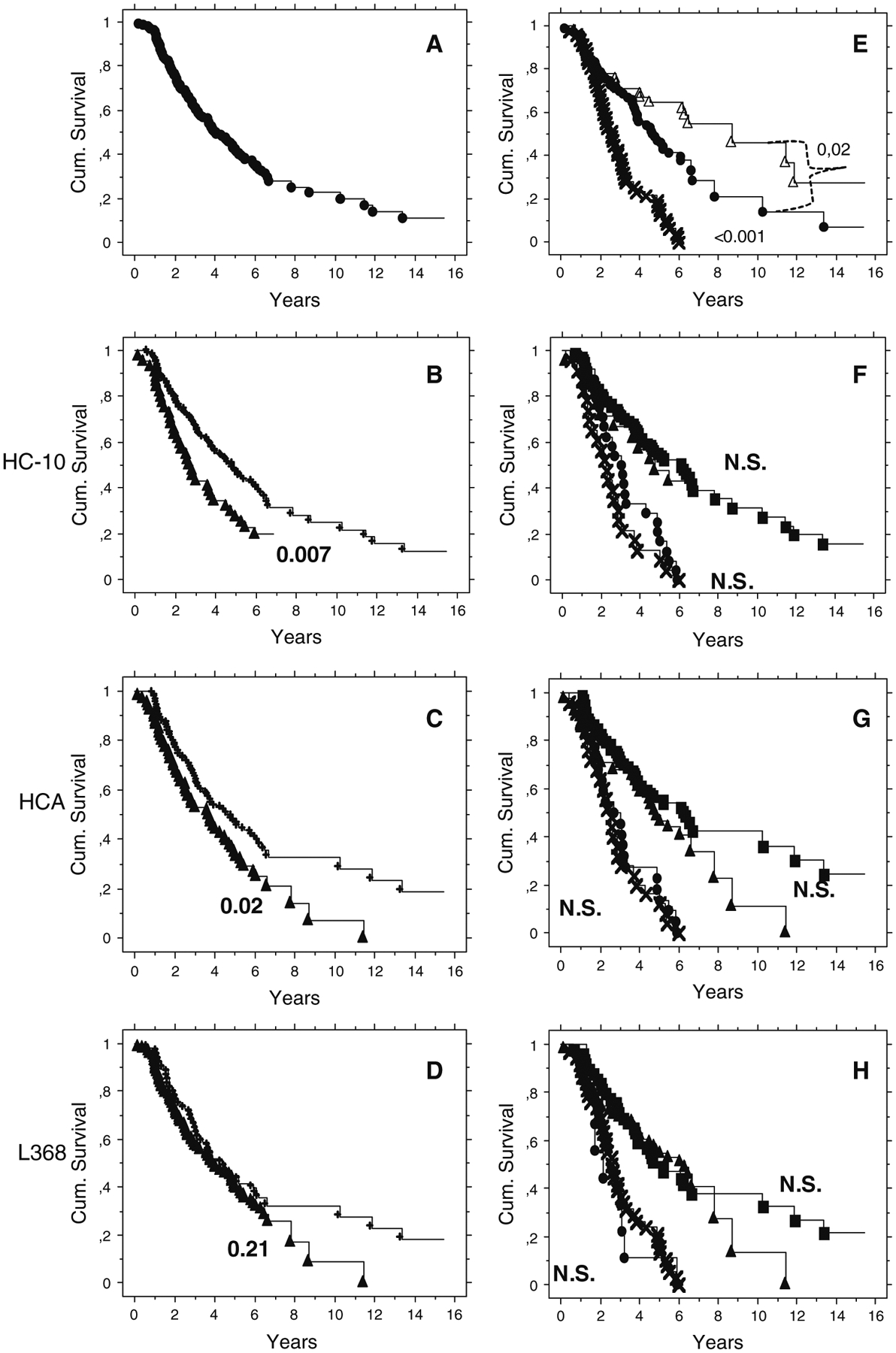

Association of HLA class I heavy chain expression with patients’ survival

The overall survival was estimated by Kaplan–Meir analysis of the cohort studied (Fig. 2a). Patients with tumours with high staining scores for HLA class I HC had a significantly longer survival than patients with low or absent HLA class I HC staining (HC10, P = 0.007; HCA, P = 0.02; Fig. 2b, c). On the other hand, no difference in survival between cases with β2-m high- or low-stained tumours could be detected (L368 P = 0.21; Fig. 2d). When the 40 patients with low L368 but high HC10/HCA staining were excluded from the analysis, the difference in survival almost reached the significance threshold (P = 0.07) (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier and log-rank P values. a All the cohort. b Immunohistochemistry staining with HC10 mAb. High (plus symbol) and low (Wlled triangle). c Stained HCA mAB. d Stained with L368 mAb. e Kaplan–Meier and log-rank P values of patients stratified for stage III–IV and serous histology and HLA-A02*. WP (times symbol) versus BP (Wlled circle) and BP HLA-A02* (open triangle). f As in E but in the log-rank calculation are considered also the subsets defined by HC10, HCA (g) and L368 (h). BP: high (Wlled square); low (Wlled triangle). WP: high (Wlled circle); low (times symbol)

The probability of survival was higher in the BP than in the WP group (P > 0.001, Fig. 2e). This confirms previous results obtained with a different patients cohort [8]. BP HLA-A02* patients are characterized by significant longer survival compared with the other groups (P = 0.02, Fig. 2e) and also a tendency of higher staining scores for HLA class I HC.

The introduction of low and high HLA class I HC or β2-m staining variables could not further improve the probability of survival of WP and BP groups (Fig. 2f–h).

These observations were completed by time to death validation using the proportional hazard regression method (Table 5). Prognostic groups (WP and BP) with high and low HLA class I HC and β2-m expression were tested in univariate and multivariate analyses. The HR in univariate analysis for WP versus BP was 3.3 (CI 2.2–4.9 P = <0.001) and for low versus high staining for HC10 was 1.7 (CI 1.1–2.5, P = 0.01) and for HCA 1.5 (CI 1.5–2.2, P = 0.02. As expected from the results presented in the Kaplan–Meir analysis, the HR for mAb L368 low versus high staining was 1.27 (CI 0.86–1.9, P = 0.22).

Table 5.

Proportional hazard regression and time to death. Comparison between MHC class I products and HLA genotype

| Strata | Factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | ||

| All patients not stratified | WP versus BP | 3.3 | 2.2–4.9 | <0.001 | 3.2 | 2.1–4.9 | <0.001 |

| HC10 low versus high | 1.7 | 1.1–2.5 | 0.01 | 1.14 | 0.65–1.99 | 0.64 | |

| HCA low versus high | 1.50 | 1.01–2.2 | 0.02 | 1.37 | 0.8–2.3 | 0.24 | |

| L368 low versus high | 1.27 | 0.86–1.9 | 0.22 | 0.79 | 0.49–1.3 | 0.34 | |

| HLA-A02* | WP versus BP | 5.4 | 3–10 | <0.001 | 5.8 | 3.1–10.9 | <0.001 |

| HC10 low versus high | 1.8 | 1–3.2 | 0.05 | 1.3 | 0.5–3.2 | 0.54 | |

| HCA low versus high | 1.5 | 0.9–2.6 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.4–2.3 | 0.99 | |

| L368 low versus high | 1.34 | 0.83–2.1 | 0.23 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 | 0.31 | |

The multivariate analysis ranked WP versus BP highly, superior to the low versus high HLA class I HC and β2-m staining. Thus, the combination of variables that characterizes WP patients (HR 3.2, CI 2.1–4.9, P = <0.001) is an independent predictor of risk of death regardless of HLA class I HC or β2-m staining (HC10 1.14, P = 0.64; HCA 1.37, P = 0.64; L368 0.79, P = 0.34).

Stratification for HLA-A02* in univariate and multivariate strongly corroborates the data presented for the all cohort.

Discussion

Cancer patients with serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary in advanced stage have a significant worse prognosis if they carry HLA-A02* genotype; however, this is not a risk factor [8, 10]. The distribution of HLA haplotypes is different over the world and mirrors populations migration as well as selection due to environmental pressure; HLA-A02* genotype is most common in Scandinavia, Asia and among American Indians [40–42]. We investigated the correlation of HLA-A02* genotype with HLA class I HC and β2-m expression in EOC patients. Since many other studies demonstrated HLA class I HC down-regulation as an independent prognostic marker [7, 43, 44], we investigated whether this could be a possible explanation for the poor prognostic impact of HLA-A02* as previously described by us [8, 10].

Firstly, we could confirm our previous observation that the WP group identified by serous histology, advanced surgical stage and HLA-A02* genotype had an impaired prognosis [8].

Our results show that HLA-A02* genotype plays the leading role in the natural course of EOC of serous histology. HLA-A02* links a prognostic factor to the aggressiveness of the disease. We have no evidence of HLA-A02* as a predictive risk factor before the tumour arises. One might speculate that HLA-A02* or genes closely connected to the HLA-A02* locus on chromosome 6 are related to other known or unknown molecules involved in proliferation, metastases and migration or NK cell resistance of tumour cells. It has recently been shown that clonal chromosomal imbalances detected by FISH with probes targeting 6p25, centromer 6 and 6q23 identify melanomas with metastatic potential [45].

HLA-G and HLA-E are also relevant, they are HLA class I paralogues and are both involved in suppression of NK cell-mediated lysis [46]. In particular, HLA-G has been described as a diagnostic and poor prognostic factor in various cancers including advanced stages of ovarian cancer [47]. Both HLA-G and HLA-E genes are in close proximity of the HLA-A gene. We are therefore currently investigating the relationship between HLA-A02* genotype and the expression of HLA-E and HLA-G antigens. This could add crucial information to explain the relationship between poor survival and HLA-A02* genotype.

Our second conclusion is that altered expression of HLA class I HC in tumour tissues predicts a lower overall survival in univariate analysis, which is in agreement with a previous study describing MHC I APM component expression and intratumoral infiltrating T-cells as independent prognostic markers in ovarian carcinoma [29]. However, β2-m down-regulation showed no impact on survival in our study. β2-m is typically co-expressed with HLA class I HC and both are needed for the trimeric HLA/β2-m/peptide complex that is presented on the cell surface. The trimeric complex is only recognized by the mAb W6/32, which does not work in formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. With that, in our study, there only exists indirect evidence of whole HLA molecule expression. On the other hand, investigation of the individual products offers very detailed information. We found that mAb L368 directed against β2-m showed more “low stained” cases compared to both mAbs HC10 and HCA. However, a significant correlation to survival in univariate or multivariate analysis was not detected. Mutations or deletions in the β2-m gene have been described in colon carcinoma, melanoma and other tumours [48, 49], and our interpretation of the 40 cases with low β2-m expression, but high expression of HLA class I HC, is that it most possibly reflect β2-m regulation at the gene level independently from HLA class I HC expression. Cases, with low staining for all three mAbs, had HR comparable to the HR observed for HLA class I HC loss alone and were more likely to represent co-down-regulation.

Our final and most important conclusion in our work highlights the association between loss of HLA class I HC expression and HLA-A02* genotype in the WP group. In multivariate analysis, the combination of variables that characterizes WP patients is an independent predictor of risk of death regardless of HLA class I HC or β2-m expression.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, examining the prognostic influence of both HLA genotype and HLA class I HC protein expression in EOC patients.

Limitations in this study include both the nature of paraffin-embedded tissues and the mAbs.

Immunohistochemical analyses of paraffin-embedded tissues are limited by the availability of locus-specific mAbs and interpretation must be made with these restrictions in mind. The two mAbs used recognize HLA class I HC of different loci: the HC10 mAb detects mainly HLA-B and HLA-C, the HCA mAb mainly HLA-A and HLA-G antigens [36, 50].

In our study, mAb HC10 stained the tumour tissues with higher frequency than mAb HCA. This could be either due to a higher sensitivity of mAb HC10 or to a higher frequency of HLA-B and HLA-C antigen expression [51, 52]. If the latter would be the case, further studies on the underlying molecular mechanisms of HLA class I antigen alterations are motivated with focus on the HLA-A locus, in particular HLA-A02*.

Immunohistochemical results give a good indication whether any alterations exists at all. They represent the basis for studies on larger patient populations and for further investigations regarding the underlying molecular mechanisms, such as loss of heterozygosity, deletions or mutations at different HLA loci. It is noteworthy that all the specimens analysed in this study were obtained from primary and not metastatic tumour lesions. Hence, this material represents different degrees of aggressiveness at the beginning of the clinical care, enabling comparative analysis of clinical outcome.

In conclusion, EOC is a deadly disease with poor outcome in general. Very few prognostic tools are available. Consequently, most patients receive indiscriminate treatment. WP patients progress early and rapidly during treatment and are likely to suffer more than they benefit from therapies today. Thus, according to our findings, it is essential to define the HLA-A genotype as soon as the patient is classified as serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary in surgical stage III–IV since additional treatment strategies need to be applied.

Investigations of loss or down-regulation of HLA class I HC have only a relative consequence in patient care or prognostic assessment. We conclude that analysis of HLA I HC expression should be pertinent when immune-based treatments are considered, and our observations point out the need for development of immunotherapies not solely relying on HLA class I restricted CD8 T-cells.

Further studies with focus on the genetics are necessary to understand the underlying mechanisms and hopefully find leads towards new therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

The statistics was performed under the supervision of Dr. Henning Johansson, Department of Oncology, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden: hemming.johansson@karolinska.se. We thank Dr. Anders Höög, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital, SE-171 76 Stockholm, Sweden, anders.hoog@karolinska.se as third pathologist consultant in the diagnosis and read out of immunohistochemistry. This study was supported by grants from the Cancer Society in Stockholm and the King Gustaf V Jubilee Fund and the Swedish Cancer Society, the Karolinska Institute/Stockholm County ALF grant and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Se-585-10-1 (Barbara Seliger). We gratefully acknowledge the motility grant #040226# from “NordForsk, Holbergs gate 1, NO-0166 Oslo, Norway” to the NCV (Emilia Andersson, HH, Lisa Villabona, Kjell Bergfeldt, Barbara Seliger, Rolf Kiessling) network project. We thank: Dr. Elisabeth Åvall-Lundqvist for her suggestions; Mrs. Liss Garber, Mrs. Gunilla Hagberg and the personnel at the Pathology Unit for assistance with the histological samples.

Abbreviations

- APM

Antigen processing machinery

- BP

Better prognosis

- β2-m

β2-microglobulin

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- EOC

Epithelial ovarian cancer

- FFPE

Formalin fixed paraffin-embedded

- HF

Haplotype frequency

- HFS

-

High frequency stained

The constitutional allele characteristicsHLA genotype

- HR

Hazard ratio

- KIR

Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors

- HLA

Human leucocyte antigen

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- FIGO

International federation of gynaecology and obstetrics

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- LFS

Low frequency stained

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- HC

Heavy chain

- Mab

Monoclonal antibody

- NK

-

Natural killer

HLA-otherwiseNon-HLA-A02*

- PLC

Peptide loading complex

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- tpn

Tapasin

- TAP

Transporter associated with antigen processing

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TA

Tumour antigen

- WP

Worst prognosis

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Emilia Andersson, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden.

Lisa Villabona, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden.

Kjell Bergfeldt, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden.

Joseph W. Carlson, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden

Soldano Ferrone, Departments of Surgery, Immunology and Pathology, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Rolf Kiessling, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden.

Barbara Seliger, Institute of Medical Immunology, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle/Saale, Germany.

Giuseppe V. Masucci, Department of Oncology-Pathology, Karolinska Institute, Radiumhemmet, Karolinska University Hospital, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden

References

- 1.Auersperg N, Wong AS, Choi KC, Kang SK, Leung PC (2001) Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev 22(2):255–288. doi: 10.1210/er.22.2.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Haiba M, Boice CR, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM (2004) The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol 23(1):41–44. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000101080.35393.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal R, Linch M, Kaye SB (2006) Novel therapeutic agents in ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 32(8):875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2002) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 55(2):74–108. doi:55/2/74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbst AL (1994) The epidemiology of ovarian carcinoma and the current status of tumor markers to detect disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170(4):1099–1105. doi:S0002937894000955; Discussion 1105–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coukos G, Rubin SC (1998) Chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer: new molecular perspectives. Obstet Gynecol 91(5 Pt 1):783–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan MJ, Nagymanyoki Z, Bonome T, Johnson ME, Litkouhi B, Sullivan EH, Hirsch MS, Matulonis UA, Liu J, Birrer MJ, Berkowitz RS, Mok SC (2008) Increased HLA-DMB expression in the tumor epithelium is associated with increased CTL infiltration and improved prognosis in advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14(23):7667–7673. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamzatova Z, Villabona L, Dahlgren L, Dalianis T, Nillson B, Bergfeldt K, Masucci GV (2006) Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) A2 as a negative clinical prognostic factor in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 103(1):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Petris L, Bergfeldt K, Hising C, Lundqvist A, Tholander B, Pisa P, Van Der Zanden HG, Masucci G (2004) Correlation between HLA-A2 gene frequency, latitude, ovarian and prostate cancer mortality rates. Med Oncol 21(1):49–52. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:1:49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamzatova Z, Villabona L, van der Zanden H, Haasnoot GW, Andersson E, Kiessling R, Seliger B, Kanter L, Dalianis T, Bergfeldt K, Masucci GV (2007) Analysis of HLA class I–II haplotype frequency and segregation in a cohort of patients with advanced stage ovarian cancer. Tiss Antigens 70(3):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masucci GV, Andersson E, Villabona L, Helgadottir H, Bergfeldt K, Cavallo F, Forni G, Ferrone S, Aniruddha C, Seliger B, Kiessling R (2010) Survival of the fittest or best adapted-HLA-dependent tumour development. J Nucl Acids Investig. doi: 10.4081/jnai.2010.e9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.So T, Takenoyama M, Sugaya M, Yasuda M, Eifuku R, Yoshimatsu T, Osaki T, Yasumoto K (2001) Unfavorable prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma associated with HLA-A2. Lung Cancer 32(1):39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogentine CN Jr, Dellon AL, Chretien PB (1977) Prolonged disease-free survival in bronchogenic carcinoma associated with HLA-Aw19 and HLA-B5. A 2-year prospective study. Cancer 39(6):2345–2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helgadottir H, Andersson E, Villabona L, Kanter L, van der Zanden H, Haasnoot GW, Seliger B, Bergfeldt K, Hansson J, Ragnarsson-Olding B, Kiessling R, Masucci GV (2009) The common Scandinavian human leucocyte antigen ancestral haplotype 62.1 as prognostic factor in patients with advanced malignant melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 58(10):1599–1608. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0669-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tisch M, Kyrberg H, Weidauer H, Mytilineos J, Conradt C, Opelz G, Maier H (2002) Human leukocyte antigens and prognosis in patients with head and neck cancer: results of a prospective follow-up study. Laryngoscope 112(4):651–657. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200204000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoon DS, Okamoto T, Wang HJ, Elashoff R, Nizze AJ, Foshag LJ, Gammon G, Morton DL (1998) Is the survival of melanoma patients receiving polyvalent melanoma cell vaccine linked to the human leukocyte antigen phenotype of patients? J Clin Oncol 16(4):1430–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JE, Abdalla J, Porter GA, Bradford L, Grimm EA, Reveille JD, Mansfield PF, Gershenwald JE, Ross MI (2002) Presence of the human leukocyte antigen class II gene DRB1* 1101 predicts interferon gamma levels and disease recurrence in melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol 9(6):587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marincola FM, Venzon D, White D, Rubin JT, Lotze MT, Simonis TB, Balkissoon J, Rosenberg SA, Parkinson DR (1992) HLA association with response and toxicity in melanoma patients treated with interleukin 2-based immunotherapy. Cancer Res 52(23):6561–6566 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell MS, Harel W, Groshen S (1992) Association of HLA phenotype with response to active specific immunotherapy of melanoma. J Clin Oncol 10(7):1158–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sosman JA, Unger JM, Liu PY, Flaherty LE, Park MS, Kempf RA, Thompson JA, Terasaki PI, Sondak VK (2002) Adjuvant immunotherapy of resected, intermediate-thickness, node-negative melanoma with an allogeneic tumor vaccine: impact of HLA class I antigen expression on outcome. J Clin Oncol 20(8):2067–2075. doi: 10.1200/jco.2002.08.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bain C, Merrouche Y, Puisieux I, Blay JY, Negrier S, Bonadona V, Lasset C, Lanier F, Duc A, Gebuhrer L, Philip T, Favrot MC (1997) Correlation between clinical response to interleukin 2 and HLA phenotypes in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 75(2):283–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzke A, Buer J, Probst-Kepper M, Lindig C, Framzle M, Schrader AJ, Ganser A, Atzpodien J (2001) HLA phenotype and cytokine-induced tumor control in advanced renal cell cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 16(5):401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onishi T, Ohishi Y, Iizuka N, Imagawa K (1996) Phenotype frequency of human leukocyte antigens in Japanese patients with renal cell carcinoma who responded to interferon-alpha treatment. Int J Urol 3(6):435–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta AM, Jordanova ES, Kenter GG, Ferrone S, Fleuren G (2008) Association of antigen processing machinery and HLA class I defects with clinicopathological outcome in cervical carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 57(2):197–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montoya L, Saiz I, Rey G, Vela F, Clerici-Larradet N (1998) Cervical carcinoma: human papillomavirus infection and HLA-associated risk factors in the Spanish population. Eur J Immunogenet 25(5):329–337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortes J, Fayad L, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Lee MS, Talpaz M (1998) Association of HLA phenotype and response to interferon-alpha in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia 12(4):455–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Campo A, Mendez R, Aptsiauri N, Rodriguez T, Zinchenko S, Garcia A, Gallego A, Gaudernack G, Ward S, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F (2007) HLA total loss: different molecular mechanisms found in different tumor cell lines. Tiss Antigens 69(5):412 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabrera T, Lopez-Nevot MA, Gaforio JJ, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F (2003) Analysis of HLA expression in human tumor tissues. Cancer Immunol Immunother 52(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0332-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han LY, Fletcher MS, Urbauer DL, Mueller P, Landen CN, Kamat AA, Lin YG, Merritt WM, Spannuth WA, Deavers MT, De Geest K, Gershenson DM, Lutgendorf SK, Ferrone S, Sood AK (2008) HLA class I antigen processing machinery component expression and intratumoral T-cell infiltrate as independent prognostic markers in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 14(11):3372–3379. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leffers N, Lambeck AJ, de Graeff P, Bijlsma AY, Daemen T, van der Zee AG, Nijman HW (2008) Survival of ovarian cancer patients overexpressing the tumour antigen p53 is diminished in case of MHC class I down-regulation. Gynecol Oncol 110(3):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benedet JL, Bender H, Jones H III, Ngan HY, Pecorelli S (2000) FIGO staging classifications and clinical practice guidelines in the management of gynecologic cancers. FIGO committee on gynecologic oncology. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 70(2):209–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavassoli F, Devilee P (2003) Tumours of the breast and female genital organs. IARC Press, Lyon. ISBN 9283224124 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lampson LA, Fisher CA, Whelan JP (1983) Striking paucity of HLA-A, B, C and beta 2-microglobulin on human neuroblastoma cell lines. J Immunol 130(5):2471–2478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perosa F, Luccarelli G, Prete M, Favoino E, Ferrone S, Dammacco F (2003) Beta 2-microglobulin-free HLA class I heavy chain epitope mimicry by monoclonal antibody HC-10-specific peptide. J Immunol 171(4):1918–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sernee MF, Ploegh HL, Schust DJ (1998) Why certain antibodies cross-react with HLA-A and HLA-G: epitope mapping of two common MHC class I reagents. Mol Immunol 35(3):177–188. doi:S0161589098000261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stam NJ, Spits H, Ploegh HL (1986) Monoclonal antibodies raised against denatured HLA-B locus heavy chains permit biochemical characterization of certain HLA-C locus products. J Immunol 137(7):2299–2306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YS, Kim TE, Kim BK, Park TG, Kim GM, Jee SB, Ryu KS, Kim IK, Kim JW (2002) Alterations of HLA class I and class II antigen expressions in borderline, invasive and metastatic ovarian cancers. Exp Mol Med 34(1):18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrido F, Cabrera T, Accolla RS et al. (1997) HLA and cancer. In: 12th International histocompatibility workshop study—HLA, June, St. Malo, France, vol I, 1996 edn, pp 445–452 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pecorelli S, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Creasman W, Shepherd J, Sideri M, Benedet J (1998) Carcinoma of the ovary. J Epidemiol Biostat 3(1):75–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A (eds) (1994) The history and geography of human genes. Princetown University Press, Princetown [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones PN (ed) (2004) American Indian MtDNA, Y chromosome genetic data, and the peopling of North America. Bäuu Institute, Boulder [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parham P, Adams EJ, Arnett KL (1995) The origins of HLA-A, B, C polymorphism. Immunol Rev 143(1):141–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1995.tb00674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leffers N, Gooden MJ, de Jong RA, Hoogeboom BN, ten Hoor KA, Hollema H, Boezen HM, van der Zee AG, Daemen T, Nijman HW (2009) Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes in primary and metastatic lesions of advanced stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 58(3):449–459. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0583-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rolland P, Deen S, Scott I, Durrant L, Spendlove I (2007) Human leukocyte antigen class I antigen expression is an independent prognostic factor in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13(12):3591–3596. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.North JP, Vetto JT, Murali R, White KP, White CR Jr, Bastian BC (2011) Assessment of copy number status of chromosomes 6 and 11 by FISH provides independent prognostic information in primary melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol 35(8):1146–1150. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318222a634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menier C, Rouas-Freiss N, Favier B, LeMaoult J, Moreau P, Carosella ED (2010) Recent advances on the non-classical major histocompatibility complex class I HLA-G molecule. Tiss Antigens 75(3):201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menier C, Prevot S, Carosella ED, Rouas-Freiss N (2009) Human leukocyte antigen-G is expressed in advanced-stage ovarian carcinoma of high-grade histology. Hum Immunol 70(12):1006–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atkins D, Ferrone S, Schmahl GE, Storkel S, Seliger B (2004) Down-regulation of HLA class I antigen processing molecules: an immune escape mechanism of renal cell carcinoma? J Urol 171(2 Pt 1):885–889. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000094807.95420.fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirata T, Yamamoto H, Taniguchi H, Horiuchi S, Oki M, Adachi Y, Imai K, Shinomura Y (2007) Characterization of the immune escape phenotype of human gastric cancers with and without high-frequency microsatellite instability. J Pathol 211(5):516–523. doi: 10.1002/path.2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stam NJ, Vroom TM, Peters PJ, Pastoors EB, Ploegh HL (1990) HLA-A and -B-specific monoclonal antibodies reactive with free heavy chains in western blots, in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and in cryo-immuno-electron microscopy. Int Immunol 2(2):113–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menon AG, Morreau H, Tollenaar RA, Alphenaar E, Van Puijenbroek M, Putter H, Janssen-Van Rhijn CM, Van De Velde CJ, Fleuren GJ, Kuppen PJ (2002) Down-regulation of HLA-A expression correlates with a better prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Lab Invest 82(12):1725–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demanet C, Mulder A, Deneys V, Worsham MJ, Maes P, Claas FH, Ferrone S (2004) Down-regulation of HLA-A and HLA-Bw6, but not HLA-Bw4, allospecificities in leukemic cells: an escape mechanism from CTL and NK attack? Blood 103(8):3122–3130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-25002003-07-2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]