Abstract

Objectives:

This research evaluates whether environmental exposures (pesticides and smoke) influence respiratory and allergic outcomes in women living in a tropical, agricultural environment.

Methods:

We used data from 266 mothers from the Infants’ Environmental Health (ISA) cohort study in Costa Rica. We evaluated environmental exposures in women by measuring seven pesticide and two polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons metabolites in urine samples. We defined “high exposure” as having a metabolite value in the top 75th percentile. We collected survey data on respiratory and allergic outcomes in mothers as well as on pesticides and other environmental exposures. Using logistic regression models adjusted for obesity, we assessed the associations of pesticide exposure with multiple outcomes (wheeze, doctor-diagnosed asthma, high (≥2) asthma score based on symptoms, rhinitis, eczema, and itchy rash).

Results:

Current pesticide use in the home was positively associated with diagnosed asthma (OR=1.99, [95% CI=1.05, 3.87]). High urinary levels of 5-hydroxythiabendazole (thiabendazole metabolite) and living in a neighborhood with frequent smoke from waste burning were associated with a high asthma score (1.84, [1.05, 3.25] and 2.31, [1.11, 5.16], respectively). Women who worked in agriculture had a significantly lower prevalence of rhinitis (0.19, [0.01, 0.93]), but were more likely to report eczema (2.54, [1.33, 4.89]) and an itchy rash (3.17, [1.24, 7.73]).

Conclusions:

While limited by sample size, these findings suggest that environmental exposure to both pesticides and smoke may impact respiratory and skin-related allergic outcomes in women.

Keywords: Asthma, respiratory disease, allergy, pesticide, agriculture

Introduction

Women living in rural settings in low and middle income countries experience a myriad of environmental exposures that can cause or exacerbate respiratory and allergic diseases. These environmental exposures can occur around the home as well as in the community or workplace. Women living in the banana growing regions in Costa Rica are exposed to a variety of environmental exposures such as pesticides, including fungicides (e.g., mancozeb), insecticides (e.g., chlorpyrifos, permethrin, buprofezin), and herbicides (e.g., 2,4-D), and smoke from various sources.1–5 Pesticide exposures occur through multiple pathways, including ambient exposure via aerial spraying, direct contact via occupational exposure, and para-occupational exposure due to other household members working in agriculture.1,6 Pesticides are also applied in/around the home by the Ministry of Health or women themselves, mainly for vector control. Exposures to smoke can be caused by tobacco smoke, household and industrial waste burning, or use of biomass for cooking fuel.4,5

Both pesticide and smoke exposures have been related to respiratory and allergic outcomes in women globally. Pesticides have been associated with respiratory and allergic symptoms in occupationally exposed populations.1,7–9 Studies investigating the relationships between agricultural pesticide exposure and health outcomes have traditionally focused on men, but are increasingly examining women as many women are employed in agriculture.1,8–12 Previous research on women exposed to pesticides has found increased risk of respiratory and allergic outcomes like rhinitis.9,11,13 Allergic skin conditions may also be associated with pesticide exposure,14–16 but more research on this relationship in women is warranted. Smoke exposure from waste burning (both commercial and household) and the use of biomass cooking fuel has been associated with respiratory symptoms and allergic symptoms such as rhinitis in resource-poor countries.17–20

The Infants’ Environmental Health (‘Infantes y Salud Ambiental’, ISA) study is a prospective birth cohort study of pregnant women and their children living near banana plantations in Matina County, Costa Rica.2,21 This analysis examines the associations of women’s exposure to pesticides (during pregnancy and when their children were 1 and 5 years old) and smoke (when their children were 5 years old) with respiratory and allergic outcomes. The goal of this study is to observe the relationship between these environmental exposures and the health of women in a resource-poor setting. We hypothesized that higher exposures to both pesticides and smoke would be associated with a higher likelihood of respiratory and allergic symptoms.

Methods

Study design

The ISA study enrolled 451 pregnant women between March 2010 and June 2011.2,21 Eligible women were age >15 years, <33 weeks pregnant, and lived in Matina County, Costa Rica. Women completed two to six study visits between pregnancy and when their children were 5 years old. These were one to three study visits during pregnancy (depending on their gestational age at enrollment), shortly after delivery (median=7 weeks postpartum), and when their children were 1 and 5 years old (Figure S1). The majority of the attrition in the cohort occurred soon after childbirth.

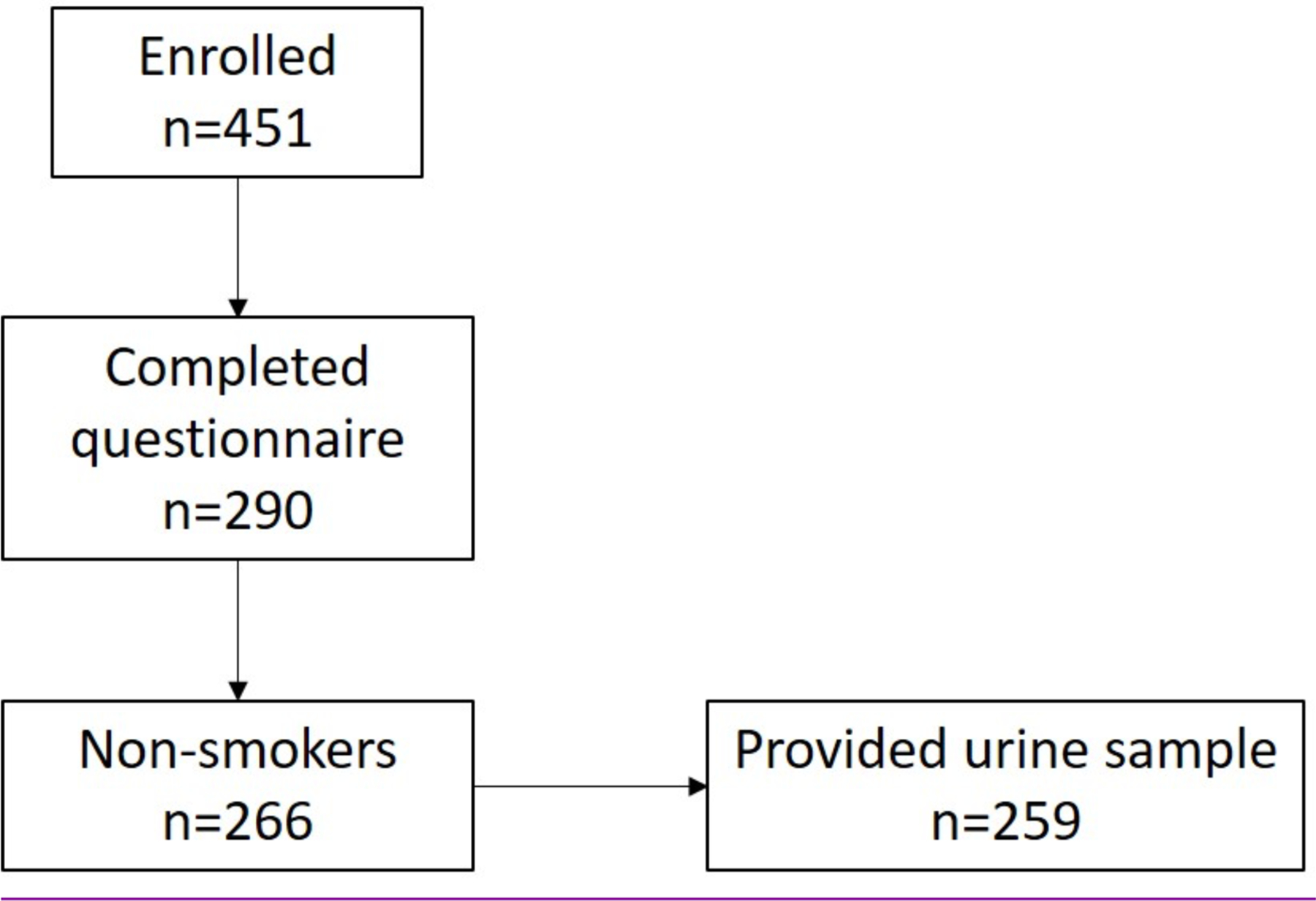

This analysis focuses the 290 women who completed a questionnaire when their children were five years old (Figure 1). We excluded the 24 women with any history of smoking, resulting in an effective sample size of 266. Only 259 women provided a urine sample at their children’s 5-year study visit.

Figure 1.

Cohort sample sizes, Matina County, Costa Rica, 2010–2017

Women completed a questionnaire based on both previous ISA questionnaires and the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) at their children’s 5-year study visit that collected information on age, education, parity, smoking history, occupational history, and medical history (e.g., medical conditions and medication use).22 We also asked women about environmental exposures such as residential pesticide use, vector-control pesticide spraying by health authorities, frequency of smoke from any waste burning, cooking fuel use, and tobacco use (both personally and in their homes). This questionnaire has been previously used in studies of Costa Rican populations.1,23,24 Women’s height and weight were measured at the same study visit and used to calculate BMI.

The Ethical and Scientific Committee of the Universidad Nacional in Costa Rica approved all study protocols. All mothers provided written informed consent at enrollment and additional informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of participants aged <18 years.

Respiratory and Allergic Outcomes

We examined three respiratory outcomes: (i) wheeze (ii) doctor-diagnosed asthma, and (iii) asthma symptom score based on Sunyer’s methodology (a score ranging from zero to five based on the following symptoms: wheezing with shortness of breath in the last 12 months, woken up with a feeling of chest tightness in the last 12 months, attack of shortness of breath at rest in the last 12 months, attack of shortness of breath after exercise in the last 12 months, and woken by attack of shortness of breath in the last 12 months).25 The asthma score was developed using baseline self-reported responses from the health survey and has shown to be predictive of future asthma medication use and airway reactivity follow-up.26 We chose this as a potential metric of undiagnosed or poorly managed asthma in this medically underserved community. For our statistical analysis, we a priori dichotomized the asthma scores into low (0–1) and high (2–5).

We considered rhinitis, eczema, and itchy rash as allergic outcomes. We recognize that these may not all meet the definition of allergy as defined by specific or total IgE.27 Notably, the questions related to eczema and itchy rash were administered to all (n=266), whereas the rhinitis question was administered to only 246 women (it was added to the questionnaire after the study visits had started).

Exposure assessment of pesticides and markers of smoke

At each study visit we collected spot urine samples, which were frozen and shipped on dry ice to the lab. Details of specimen collection and analysis have been previously published.2,21 Urine samples were analyzed at the Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Lund University in Sweden. The laboratory participates and has qualified as a European Human Biomonitoring Initiative (HBM4EU) laboratory for the analysis of 1-HP. Urinary metabolites were measured using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; QTRAP 5500, AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). Briefly, the samples were analyzed for fungicides [ethylenethiourea (ETU, metabolite of mancozeb), hydroxypyrimethanil (OHP, metabolite of pyrimethanil), 5-hydroxythiabendazole (OHT, metabolite of thiabendazole)], organophosphate (OP) insecticides [3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP, metabolite of chlorpyrifos) used in banana plantations, the sum of cis/trans [3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid (DCCA, metabolite of permethrin, cypermethrin, and cyfluthrin), 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3PBA, metabolite of permethrin, cypermethrin, cyfluthrin, deltamethrin, allethrin, resmethrin, and fenvalerate)], and the herbicide 2,4-D.28 Urine samples collected from women when their children were 5 years old were also analyzed for 1-hydroxypyrene (1-HP) and hydroxyphenanthrene (2-OH-PH), biomarkers of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which can originate from wood burning.29,30 Urinary metabolite concentrations were corrected for dilution using specific gravity. Detection limits have been previously published.21,28,30 Metabolite concentrations below the limit of detection (LOD) were randomly imputed to vary between half the LOD and the LOD.

Statistical analysis

Socio-demographic, outcome, and exposure data were summarized with counts (percentages) for categorical variables and medians (25th, 75th percentiles) for continuous variables. Frequency of smoke from waste burning was grouped into three categories: Never, Some/Monthly, and Weekly/Daily. The association between a woman working in agriculture and having high levels of OHT was assessed with a chi-squared test. Spearman correlation coefficients between metabolites were calculated.

Women’s pesticide exposures were classified as “historic” (i.e., during pregnancy, shortly after delivery, and when their children were 1 years old) or “current” (i.e., when their children were 5 years old). Due to the large variability in metabolite concentrations and presence of extreme values, we dichotomized current exposure to each pesticide or PAHs biomarker into low (≤75th percentile) and high (>75th percentile). This was done prior to any modeling analysis. The cut point was selected based on the distributions of the metabolites in conjunction with power considerations (Figure S2). Historic pesticide exposures also varied widely over time, thus we used the overall historic distributions to identify a cut point for “high” exposure.21 To avoid regression to the mean in the historic exposures, we created distributions of pesticide exposures from all historic samples. A woman who exceeded the 75th percentile of a distribution in more than 40% of her historic study visits was considered to have frequent high exposure to that pesticide. Frequent high exposure was defined as greater than 40% of a woman’s historic visits based on the number of visits where exposures were high (>75th percentile). This method of exposure classification was driven by the short half-lives of pesticide metabolites and assumes if a woman has been frequently exposed to high levels of a specific pesticide she is likely to have repeated exposure to this pesticide.

We fit individual logistic regression models adjusted for obesity (dichotomous: BMI<30, BMI≥30) to assess the exposure-outcome associations of interest. We excluded ever smokers (n=24) from our main models, but they were included in sensitivity analyses. We highlight statistically significant associations (α=0.05). All analyses were done in R (version 3.6.1).31

Results

A total of 266 women were included in this analysis. At the time of questionnaire administration (2016–2017), the median (25th, 75th) age of study participants was 29 (25, 35) years and 45% (n=119) of the women were obese (Table 1). Women included in our main analysis did not smoke or live with someone who frequently smoked.

Table 1.

Demographic, health, and exposure data for 266 non-smoking women living in Matina County, Costa Rica, 2016–2017

| Cohort Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Median | (25th, 75th) | |

| Age | 29 | (25, 35) |

| N | % | |

| Obesity | ||

| Obese (BMI>30) | 119 | 44.7 |

| Not Obese (BMI <30) | 147 | 55.3 |

| Outcomes | N | % |

| Wheeze | 43 | 16.2 |

| Asthma diagnosed by doctor | 56 | 21.1 |

| Asthma Score 25 | ||

| 0 | 118 | 44.4 |

| 1 | 50 | 18.8 |

| 2 | 34 | 12.8 |

| 3 | 27 | 10.2 |

| 4 | 24 | 9.0 |

| 5 | 13 | 4.9 |

| Dichotomized Asthma score | ||

| 0,1 | 168 | 63.2 |

| 2,3,4,5 | 98 | 36.8 |

| Rhinitis | 25 | 9.4 |

| Missing1 | 17 | 6.4 |

| Eczema | 83 | 31.2 |

| Itchy Rash | 25 | 9.4 |

| Exposures | N | % |

| Historic urine sample obtained | 266 | 100 |

| Concurrent urine sample obtained | 259 | 97.4 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.1 |

| Mother worked in banana or other agriculture business in the last 3 years | 89 | 33.5 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.4 |

| Mother currently working in banana or other agriculture business | 47 | 17.7 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.4 |

| Husband worked in banana field in the last 3 years | 137 | 51.5 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.4 |

| Husband currently working in banana field | 125 | 47 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.4 |

| Husband worked in other agriculture business in the last 3 years | 21 | 7.9 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.4 |

| Husband currently working in other agriculture business | 14 | 5.3 |

| Missing | 9 | 3.4 |

| Smoke from waste burning reached house (grouped) | ||

| Never | 44 | 16.5 |

| Some/Monthly | 54 | 20.3 |

| Weekly/Daily | 168 | 63.2 |

| Cooking Fuel: Gas | 235 | 88.3 |

| Cooking Fuel: Wood | 66 | 24.8 |

| Cooking Fuel: Electric | 50 | 18.8 |

| Pesticide used inside the home | 139 | 52.3 |

| Missing | 11 | 4.1 |

| Pesticide used outside the home | 13 | 4.9 |

| Missing | 14 | 5.3 |

| Vector Control (Spraying by health authorities) | 146 | 54.9 |

| Missing | 11 | 4.1 |

n=17 women received a questionnaire missing a question about rhinitis

Doctor-diagnosed asthma was more commonly reported (21%, n=56) than wheeze in the 12 months prior to the survey (16%, n=43; Table 1). The asthma score was right skewed with 44% (n=118) of participants having a score of zero. A total of 98 women (37%) had two or more asthma symptoms and were considered to have a high asthma score. About 70% (n=184) of the women with a high asthma score had been diagnosed with asthma by a doctor, whereas 8% (n=20) reported an asthma diagnosis but did not have a high asthma score (Table 2). The variability between diagnosed asthma and symptomatic asthma suggests some women with asthmatic symptoms were not diagnosed with asthma, while others had well-controlled asthma as they were asymptomatic.

Table 2.

Diagnosed asthma and asthma score counts for 266 non-smoking women living in Matina County, Costa Rica, 2016–2017

| Diagnosed asthma | Asthma Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Yes | 12 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 5 |

| No | 106 | 42 | 26 | 15 | 13 | 8 |

We evaluated three allergic outcomes (rhinitis, itchy rash, and eczema). Rhinitis (9%, n=25) and itchy rash (9%, n=25) were uncommon, but eczema (31%, n=83) was reported by about one-third of the study population (Table 1).

We also collected data on non-specific occupational and residential exposures using self-reported information (Table 1). One-third of study participants reported working in agriculture (including banana farms) in the three years prior to the health survey (34%, n=89). About half of the women reported using pesticides inside their home (52%, n=139) or having been exposed to vector-control pesticide spraying by health authorities during the last six months (55%, n=146). Waste burning was common with most women reporting smoke from waste burning reaching their home daily or weekly (63%, n=168). Pesticide exposure was common in the study population; over 99% of historic samples had detectable concentrations of all metabolites. Detection in current samples was also high (pyrethroids, ETU, TCP, and 2,4-D were detected in all samples). OHP was measured in 92% of current samples; OHT was measured in 72% of samples (Table S1). The range of each metabolite as well as the value used for the 75th percentile cutoff is shown in Table S1. Historic pesticide exposure levels were similar to current exposure concentrations for TCP, 2,4-D, OHP, and OHT. For ETU, current exposures were slightly lower than historic exposures. Pyrethroid (3PBA, DCCA, and combined pyrethroids) concentrations were slightly higher in current samples. Women who worked in agriculture were more likely to have high values of OHT (p <0.001). Metabolites of PAHs were detected in 94% (2-OH-PH) and 98% (1-HP) of the current samples. PAH metabolites were correlated with each other (r=0.74), but most pesticide metabolites had weak correlations (Table S2). Only 3PBA and DCCA were strongly correlated, as they are both markers of pyrethroids (r=0.80). Respiratory outcomes were associated with self-reported exposure to pesticides and other environmental chemicals and with current urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations, but there was no clear pattern in the results (Table 3). Pesticide use in the home was associated with increased odds of doctor-diagnosed asthma (OR=1.99, 95% CI: [1.05, 3.87]). For the symptom-based asthma score, frequent exposure to smoke burning (daily/weekly vs. never) was significantly associated with a high asthma score (OR=2.31, 95% CI: [1.11, 5.16]). Wheeze was not associated with any occupational or residential exposures assessed via questionnaire. Current high OHT exposure was associated with a high asthma score (OR=1.84, 95% CI: [1.05, 3.25]). Wheeze was inversely associated with high historic pyrethroid exposure (OR=0.38, 95% CI: [0.14, 0.91]) and DCCA (OR=0.31, 95% CI: [0.10, 0.77], Table S3); current exposures showed similar associations (Table 3). Doctor-diagnosed asthma had a suggestive positive association with current TCP (OR=1.75, 95% CI: [0.89, 3.36]), but there was no evidence of an association of current TCP with wheeze or asthma score. High levels of hydroxypyrene metabolites related to burning were not significantly associated with any respiratory outcomes.

Table 3.

Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for respiratory outcomes and environmental exposures in non-smoking women living in Matina County, Costa Rica, 2016–2017 (n=266).

| Exposure | Wheeze (n=43) | Doctor-diagnosed Asthma (n=56) | High asthma Score (n=98) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation al/Residential Exposures (n=266) | N Exposed | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | aOR 1 | 95% Confidence Interval | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | aOR 1 | 95% Confidence Interval | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | aOR 1 | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Mother currently works in banana or other agriculture business | 47 | 1.69 | (0.73, 3.67) | 1.75 | (0.75, 3.89) | 1.58 | (0.74, 3.20) | 1.64 | (0.76, 3.40) | 1.81 | (0.73, 4.22) | 1.40 | (0.72, 2.70) |

| Father currently works on banana plantation | 125 | 0.79 | (0.39, 1.56) | 0.68 | (0.33, 1.37) | 0.89 | (0.48, 1.62) | 0.77 | (0.41, 1.43) | 1.04 | (0.49, 2.19) | 1.21 | (0.72, 2.05) |

| Father worked in other agriculture business in last 3 years | 21 | 1.35 | (0.37, 3.91) | 1.26 | (0.34, 3.71) | 2.54 | (0.96, 6.40) | 2.43 | (0.90, 6.28) | 0.79 | (0.12, 3.07) | 1.26 | (0.49, 3.14) |

| Pesticide used inside the home | 139 | 1.24 | (0.62, 2.51) | 1.14 | (0.57, 2.34) | 2.11 | (1.13, 4.08) | 1.99 | (1.05, 3.87) | 1.66 | (0.78, 3.68) | 1.17 | (0.70, 1.99) |

| Government spraying | 146 | 1.23 | (0.62, 2.53) | 1.35 | (0.67, 2.81) | 1.44 | (0.78, 2.73) | 1.59 | (0.84, 3.06) | 0.89 | (0.42, 1.91) | 0.91 | (0.54, 1.54) |

| Smoke from waste burning reached house | |||||||||||||

| Never | 44 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Some Months/Monthly | 54 | 1.36 | (0.42, 4.80) | 1.32 | (0.40, 4.71) | 1.15 | (0.42, 3.26) | 1.11 | (0.40, 3.20) | 1.02 | (0.33, 3.20) | 1.35 | (0.55, 3.40) |

| Weekly/Daily | 168 | 1.7 | (0.66, 5.23) | 1.82 | (0.70, 5.67) | 1.27 | (0.57, 3.15) | 1.36 | (0.60, 3.42) | 1.06 | (0.43, 2.88) | 2.31 | (1.11, 5.16) |

| Current Metabolites2 (n=259) | |||||||||||||

| Pesticides | |||||||||||||

| ETU | 70 | 1.1 | (0.51, 2.24) | 1.07 | (0.50, 2.20) | 1.03 | (0.52, 1.98) | 1.00 | (0.50, 1.94) | 0.73 | (0.29, 1.65) | 0.84 | (0.46, 1.48) |

| TCP | 63 | 0.7 | (0.29, 1.53) | 0.68 | (0.28, 1.51) | 1.74 | (0.89, 3.30) | 1.75 | (0.89, 3.36) | 0.62 | (0.22, 1.50) | 0.97 | (0.53, 1.75) |

| 2,4-D | 65 | 0.79 | (0.34, 1.69) | 0.82 | (0.35, 1.76) | 0.71 | (0.33, 1.42) | 0.73 | (0.33, 1.48) | 1.08 | (0.46, 2.35) | 0.86 | (0.47, 1.56) |

| OHP | 66 | 0.65 | (0.27, 1.42) | 0.67 | (0.27, 1.49) | 0.6 | (0.27, 1.22) | 0.62 | (0.28, 1.28) | 1.7 | (0.76, 3.65) | 1.57 | (0.88, 2.80) |

| OHT | 70 | 1.44 | (0.69, 2.88) | 1.46 | (0.70, 2.96) | 1.29 | (0.66, 2.44) | 1.31 | (0.67, 2.51) | 1.7 | (0.76, 3.65) | 1.84 | (1.05, 3.25) |

| 3PBA | 65 | 0.79 | (0.34, 1.69) | 0.70 | (0.30, 1.52) | 1.64 | (0.85, 3.11) | 1.50 | (0.76, 2.88) | 1.06 | (0.44, 2.37) | 1.10 | (0.61, 1.96) |

| DCCA | 65 | 0.55 | (0.22, 1.24) | 0.53 | (0.20, 1.20) | 0.71 | (0.33, 1.42) | 0.67 | (0.31, 1.37) | 0.91 | (0.38, 2.01) | 0.74 | (0.40, 1.34) |

| Pyrethroid3 | 64 | 0.57 | (0.22, 1.27) | 0.52 | (0.20, 1.19) | 0.94 | (0.46, 1.85) | 0.88 | (0.42, 1.75) | 1 | (0.41, 2.21) | 0.90 | (0.49, 1.62) |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons | |||||||||||||

| 1-HP | 71 | 0.68 | (0.29, 1.45) | 0.60 | (0.25, 1.30) | 0.96 | (0.48, 1.84) | 0.86 | (0.42, 1.67) | 1.05 | (0.47, 2.27) | 0.69 | (0.37, 1.23) |

| 2-OH-HP | 62 | 0.84 | (0.36, 1.81) | 0.60 | (0.25, 1.30) | 1.08 | (0.53, 2.10) | 1.02 | (0.49, 2.02) | 1.22 | (0.52, 2.70) | 0.96 | (0.52, 1.74) |

Abbreviations: ETU=ethylenethiourea, TCP=3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol, OHP= hydroxypyrimethanil, OHT=5-hydroxythiabendazole, 3PBA=3-phenoxybenzoic acid, DCCA=3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid, 1-HP=1-hydroxypyrene, 2-OH-HP=hydroxyphenanthrene

Odds ratios adjusted for obesity (BMI≥30)

Dichotomized at the 75th percentile

Sum of 3PBA and DCCA

For allergic conditions and current exposures, we found evidence of both positive and inverse associations (Table 4). For occupational and residential exposures with allergic outcomes, we observed that women who currently worked in agriculture were more likely to have eczema (OR=2.54, 95% CI: [1.33, 4.89] and itchy rash (OR=3.17, 95% CI: [1.12, 7.73]), but were less likely to report rhinitis (OR=0.19, 95% CI: [0.01, 0.93]) (Table 4). Women whose partners worked in agriculture in the three years prior to the health survey were more likely to report an itchy rash (OR=3.44, 95% CI: [1.03, 10.00]), but were less likely to report rhinitis (OR=1.02, 95% CI: [0.15, 3.85]). Pesticide spraying by health authorities was also associated with increased rhinitis (OR=2.43, 95% CI: [0.97, 6.93]). High exposure to OHT both historically and currently was associated with a doubling of itchy rash odds, but this was not statistically significant with either exposure (Tables 3 and S3).

Table 4.

Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) between allergic outcomes and environmental exposures in non-smoking women living in Matina County, Costa Rica, 2016–2017 (n=266)

| Exposure | Rhinitis (n=25) | Eczema (n=83) | Itchy Rash (n=25) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational/Residential Exposures (n=266) | N Exposed | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | aOR 1 | 95% Confidence Interval | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | aOR 1 | 95% Confidence Interval | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | aOR 1 | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Mother currently works in banana or other agriculture business | 47 | 0.19 | (0.01, 0.94) | 0.19 | (0.01, 0.93) | 2.51 | (1.31, 4.81) | 2.54 | (1.33, 4.89) | 3.08 | (1.22, 7.45) | 3.17 | (1.24, 7.73) |

| Father currently works on banana plantation | 125 | 0.2 | (0.06, 0.54) | 0.20 | (0.06, 0.56) | 1.12 | (0.66, 1.90) | 1.08 | (0.63, 1.84) | 0.88 | (0.37, 2.05) | 0.81 | (0.34, 1.90) |

| Father worked in other agriculture business in last 3 years | 21 | 1.02 | (0.15, 3.85) | 1.04 | (0.16, 3.94) | 1.37 | (0.52, 3.41) | 1.34 | (0.51, 3.33) | 3.57 | (1.08, 10.30) | 3.44 | (1.03, 10.00) |

| Pesticide used inside the home | 139 | 1.34 | (0.56, 3.35) | 1.36 | (0.57, 3.40) | 1.03 | (0.61, 1.76) | 1.00 | (0.59, 1.71) | 1.33 | (0.56, 3.31) | 1.25 | (0.52, 3.13) |

| Government spraying | 146 | 2.47 | (0.99, 7.03) | 2.43 | (0.97, 6.93) | 0.94 | (0.55, 1.61) | 0.96 | (0.56, 1.65) | 0.66 | (0.28, 1.56) | 0.69 | (0.29, 1.64) |

| Smoke from waste burning reached house | |||||||||||||

| Never | 44 | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Some Months/Monthly | 54 | 2.49 | (0.54, 17.65) | 2.55 | (0.55, 18.15) | 1.19 | (0.51, 2.86) | 1.18 | (0.50, 2.83) | 1.44 | (0.49, 4.57) | 1.41 | (0.47, 4.51) |

| Weekly/Daily | 168 | 2.4 | (0.65, 15.56) | 2.38 | (0.64, 15.43) | 1.07 | (0.53, 2.27) | 1.09 | (0.53, 2.31) | 0.36 | (0.12, 1.13) | 0.37 | (0.12, 1.16) |

| Current Metabolites2 (n=259) | |||||||||||||

| Pesticides | |||||||||||||

| ETU | 70 | 0.83 | (0.29, 2.05) | 0.83 | (0.29, 2.08) | 0.93 | (0.50, 1.66) | 0.92 | (0.50, 1.65) | 1.1 | (0.41, 2.65) | 1.08 | (0.40, 2.61) |

| TCP | 63 | 1.91 | (0.77, 4.50) | 1.93 | (0.77, 4.55) | 1.14 | (0.61, 2.06) | 1.13 | (0.61, 2.06) | 0.59 | (0.17 1.62) | 0.58 | (0.16, 1.60) |

| 2,4-D | 65 | 0.38 | (0.09, 1.15) | 0.38 | (0.09, 1.14) | 1.17 | (0.64, 2.11) | 1.19 | (0.65, 2.15) | 0.97 | (0.34, 2.43) | 1.00 | (0.35, 2.51) |

| OHP | 66 | 1.19 | (0.44, 2.90) | 1.18 | (0.44, 2.87) | 1.14 | (0.62, 2.05) | 1.16 | (0.63, 2.08) | 0.55 | (0.16, 1.51) | 0.57 | (0.16, 1.57) |

| OHT | 70 | 0.39 | (0.09, 1.18) | 0.38 | (0.09, 1.16) | 1.71 | (0.96, 3.02) | 1.72 | (0.96, 3.04) | 2.01 | (0.83, 4.67) | 2.04 | (0.84, 4.76) |

| 3PBA | 65 | 1.86 | (0.75, 4.38) | 1.96 | (0.78, 4.66) | 1.07 | (0.58, 1.93) | 1.04 | (0.56, 1.88) | 1.23 | (0.46, 2.97) | 1.13 | (0.42, 2.77) |

| DCCA | 65 | 1.77 | (0.71, 4.16) | 1.81 | (0.73, 4.28) | 0.88 | (0.47, 1.61) | 0.87 | (0.47, 1.60) | 1.52 | (0.59, 3.61) | 1.49 | (0.58, 3.55) |

| Pyrethroid3 | 64 | 1.56 | (0.61, 3.72) | 1.60 | (0.62, 3.83) | 1.33 | (0.73, 2.39) | 1.31 | (0.71, 2.35) | 1.55 | (0.61, 3.69) | 1.49 | (0.58, 3.56) |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons | |||||||||||||

| 1-HP | 71 | 0.86 | (0.30, 2.15) | 0.88 | (0.31, 2.22) | 1.28 | (0.71, 2.27) | 1.24 | (0.69, 2.21) | 1.28 | (0.50, 3.02) | 1.18 | (0.46, 2.83) |

| 2-OH-PH | 62 | 0.59 | (0.17, 1.65) | 0.60 | (0.17, 1.67) | 1.06 | (0.57, 1.94) | 1.04 | (0.56, 1.91) | 1.92 | (0.77, 4.52) | 1.86 | (0.74, 4.4) |

Abbreviations: ETU=ethylenethiourea, TCP=3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol, OHP= hydroxypyrimethanil, OHT=5-hydroxythiabendazole, 3PBA=3-phenoxybenzoic acid, DCCA=3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid, 1-HP=1-hydroxypyrene, 2-OH-HP=hydroxyphenanthrene

Odds ratios adjusted for obesity (BMI≥30)

Dichotomized at the 75th percentile

Sum of 3PBA and DCCA

Sensitivity analyses including the current and past smokers showed similar associations to those from our main models (Tables S4 and S5). Similarly, adjusting for cotinine had no effect on the results.

Discussion

We used three different outcome measures to address respiratory symptoms: wheeze, asthma score (a sum of five respiratory symptoms), and doctor diagnosis of asthma. While all three have been used in epidemiologic studies, they probably measure different things in medically underserved areas than in more developed parts of the world. Health outcome data were self-reported, which is why we chose to focus more on symptoms than self-reported diagnoses where possible. Our cohort had a higher prevalence of asthma compared to other cohorts of adults. For example, AGRICOH (A Consortium of Agricultural Cohort Studies) found an average asthma prevalence of 7.8% in women in the 18 cohorts studied, while 21% of women in our cohort reported an asthma diagnosis and 37% exhibited asthma symptoms, as measured by the asthma score.32 Our cohort did have a similar prevalence of wheeze (16%) compared to AGRICOH, which found an average of 15% of participants had respiratory symptoms (cough and wheeze).32 A study of mothers of young children living in an urban setting in Ethiopia found a lower prevalence of wheeze (6.2%) compared to our cohort; it also reported a statistically significant relationship between pesticide use in the household and respiratory symptoms.33 We similarly found an association between pesticide use in the home and doctor-diagnosed asthma.

We saw little evidence of associations between current pesticide exposure measures and current respiratory symptoms and disease. A positive association between thiabendazole exposure and high asthma score was the only significant association observed for current pesticide exposures. Thiabendazole is a post-harvest fungicide, applied to bananas before packing them for export. Women working on banana plantations had higher OHT concentrations compared to women not working in agriculture. With respect to questionnaire data, the strongest association was for pesticide use in the home with an almost two-fold increase in doctor-diagnosed asthma in women who reported pesticide use. We did not observe this association for asthma score or wheeze. These results suggest this association for asthma may be associated with increased use of insecticide by people with asthma, rather than insecticides leading to increased asthma risk.

OP insecticides have been associated with respiratory symptoms in other populations.1,8,11 We found no strong evidence of an association between chlorpyrifos (measured by TCP) and respiratory symptoms. High TCP concentrations were inversely associated with wheeze, but positively associated with asthma (there was no association with asthma score). We do not have additional data to evaluate if our findings are due to chance, a difference in application methods in the study site, or something else. Measurement error may have influenced these results in a number of ways. Pesticide metabolites are very short lived and only capture very recent exposures, so urinary biomarkers may miss peaks of exposure that may contribute to respiratory symptoms. This is for example reflected by the relatively low intraclass correlation coefficient of ETU during pregnancy (ICC=0.15).2 Our analysis of current exposures is cross-sectional and limited to one biomarker measurement. While the evidence was somewhat stronger for current exposures than for exposures five years prior, repeated measures of recent exposures would potentially help to strengthen our estimates. We attempted in our historic exposure assignment strategy to try to assign women how had been consistently highly exposed, but we probably had too few measurements to accurately assign exposure.

Frequent exposure to smoke from waste burning was associated with increased odds of a high asthma score, but not with doctor-diagnosed asthma. We did not find associations with the metabolite measurements of PAH, which may have been due to the short half-lives of 1-HP and 2-OH-PH. While we do not have detailed data on what types of waste burning occurred, burning of residential waste can result in a diverse exposure mixture including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen oxides.18,34,35 These air pollutants are known contributors to airway disease worldwide and contribute to the estimated 235 million global burden of asthma.17,20,36,37 Given that general waste burning happens on a regular basis in this area, we expect less measurement error in the questionnaire estimates than those for PAH metabolites.

Although smoking is a known risk factor for respiratory disease, we excluded smokers from our main analysis due to small numbers. Our results were consistent when smokers were included or we adjusted for cotinine levels. The women in this study did not report frequent exposure to secondhand smoke in their homes. Our small sample size and the small proportion of smokers impacted our ability to examine smoking as an effect modifier.

We found less evidence for associations between pesticide metabolites and rhinitis than other studies. Our cohort had a similar prevalence of rhinitis (9%) to a recent study in Colombia, which had a rhinitis prevalence of 10% and observed an increased risk for rhinitis in adults exposed to mixtures of paraquat, profenofos, and glyphosate.38 Similarly, a study of grape farmers in Greece had a higher prevalence of allergic rhinitis (37%) and found positive associations between use of some pesticides and allergic rhinitis. Consistent with our findings, this study did not find evidence of an association between organophosphates and rhinitis.39 We found that women who currently worked in agriculture were five times less likely to have rhinitis, consistent with a healthy worker effect. This finding may suggest women with rhinitis are less likely to seek employment in agriculture, or that women with rhinitis leave agricultural work. A study of occupational rhinitis in Slovakia also found a low prevalence of rhinitis in agricultural workers.40

Allergic skin conditions were more often associated with indirect measures of pesticide exposure such as agricultural work or government spraying of pesticides. Our findings were similar to research done in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) which found associations between agricultural pesticide exposures and skin conditions like eczema and itchy rash.15 A study of agricultural workers in the UAE found 21% had eczema and 24% had rash.15 Our cohort had more eczema (31%) than itchy rash (9%), but both studies found associations between working in agriculture and eczema. Skin-related allergic conditions were associated with longer-term exposure (i.e., both eczema and itchy rash being more common in women who currently worked in agriculture).

Additionally, high OHT concentrations were associated with increased odds of eczema and itchy rash. This finding is consistent with previous research from Panama on thiabendazole exposure and dermatologic conditions among workers in banana packing.41,42 Exposure levels of OHT were very low among most of the women in our sample and as a result the high exposed group contained women with relatively low exposures (75th percentile = 0.387 μg/L, max = 299.96 μg/L). These results suggest that allergic skin conditions may appear after prolonged exposure to pesticides.

Pyrethroids may contribute to allergic outcomes. Studies in Greece and the United States found associations between pyrethroid exposures and rhinitis.43,44 In our sample, women whose houses were treated for vector control were more likely to report rhinitis. Pyrethroids are commonly used for vector control in Costa Rica and around the world, both by health authorities and by individuals. In Costa Rica, pyrethroids are readily available at local markets and their sale is not regulated, therefore some women may be simultaneously exposed from personal use and vector control programs.

The major limitation of this study is its small sample size, which restricted our statistical power. While respiratory and allergic outcomes are common, they are multi-factorial outcomes, and we lacked the ability to control for other factors. We excluded women who smoked to help address that issue but that reduced our sample size further. For rhinitis, we had an even smaller sample size since some women were not asked this question. Given our small sample size, the cross-sectional nature of the majority of this analysis, and the high variability in the pesticide metabolite concentrations, we still observed significant associations with these outcomes, suggesting that studies with a larger sample size with more measures of exposure are necessary to help address these questions related to pesticides and other environmental exposures and respiratory and allergic outcomes.

Further research is needed on measures to effectively reduce pesticide exposures. For example, thiabendazole exposure primarily occurs at banana packing plants via fumigation chambers. Exposure may be mitigated through effective extraction procedures in the chambers or direct topical application rather than fumigation, but best practices in exposure reduction remain unknown.12

The ISA cohort provides a unique cohort to study the associations between environmental and occupational pesticide exposures and respiratory and allergic diseases. By studying women who experience pesticide exposure due to their living conditions and occupations we are able to explore how these exposures uniquely impact women. Our results add to the growing literature linking pesticides and disease among women.

Supplementary Material

What is already known?

Pesticides may contribute to respiratory and allergic symptoms in occupationally exposed individuals. A majority of these studies have been conducted in men.

What are the new findings?

Specific pesticides were associated with increased asthma symptoms in environmentally exposed women in Costa Rica.

Occupationally exposed women were more likely to report allergic skin conditions than respiratory allergic conditions.

Waste burning in rural settings continues to be a risk for asthma symptoms.

How might this impact policy in the foreseeable future?

These results may support stronger pesticide use controls which minimize environmental and occupational exposure. Waste burning should be replaced with more health protective means of waste disposal.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the ISA families, staff, and community partners. We would also like to thank Michael Cuffney, Juan Camilo Cano, Rosario Quesada, Claudia Hernandez, Diego Hidalgo, Jorge Peñaloza Castañeda, Alighierie Fajardo Soto, Marie Bengtsson, Daniela Pineda, Moosa Faniband, and Margareta Maxe for their fieldwork, laboratory analyses, and/or data management assistance.

Funding

This publication was made possible by research supported by grant numbers: PO1 105296-001 (IDRC); 6807-05-2011/7300127 (Health Canada); 2010-1211, 2009-2070, and 2014-01095 (Swedish Research Council Formas); R21 ES025374 (NIEHS); and R24 ES028526 (NIEHS).

Citations

- 1.Fieten KB, Kromhout H, Heederik D, Van Wendel De Joode B. Pesticide exposure and respiratory health of indigenous women in Costa Rica. Am J Epidemiol. 2009. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Wendel de Joode B, Mora AM, Córdoba L, et al. Aerial application of mancozeb and urinary ethylene thiourea (ETU) concentrations among pregnant women in Costa Rica: The infants’ environmental health study (ISA). Environ Health Perspect. 2015. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Wendel de Joode B, Barraza D, Ruepert C, et al. Indigenous children living nearby plantations with chlorpyrifos-treated bags have elevated 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCPy) urinary concentrations. Environ Res. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Costa Rica). Costa Rica National Household Survey 2019. San José, Costa Rica: National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Costa Rica). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park E, Lee K. Particulate exposure and size distribution from wood burning stoves in Costa Rica. Indoor Air. 2003. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2003.00194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barraza D, Jansen K, van Wendel de Joode B, Wesseling C. Pesticide use in banana and plantain production and risk perception among local actors in Talamanca, Costa Rica. Environ Res. 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, London SJ, Lynch CF, Alavanja MCR, Sandler DP. Pesticides associated with wheeze among commercial pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoppin JA, Umbach DM, London SJ, et al. Pesticides and atopic and nonatopic asthma among farm women in the agricultural health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-821OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nigatu AW, Bråtveit M, Deressa W, Moen BE. Respiratory symptoms, fractional exhaled nitric oxide & endotoxin exposure among female flower farm workers in Ethiopia. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2015;10(1). doi: 10.1186/s12995-015-0053-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García AM. Pesticide Exposure and Women’s Health. Am J Ind Med. 2003:44(6) 584–594. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ndlovu V, Dalvie MA, Jeebhay MF. Asthma associated with pesticide exposure among women in rural Western Cape of South Africa. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57(12):1331–1343. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mora Fallas M Exposición de madres y sus hijos al fungicida tiabendazol en el cantón de Matina, Csita Rica: resultados del infantes y salud ambiental (ISA). 2017. http://www.isa.una.ac.cr/images/articulos/tesis/2017_Tesis_Marcela_Mora_Fallas.pdf.

- 13.Negatu B, Kromhout H, Mekonnen Y, Vermeulen R. Occupational pesticide exposure and respiratory health: a large-scale cross-sectional study in three commercial farming systems in Ethiopia. Thorax. 2017;72(6):498–499. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangemi S, Miozzi E, Teodoro M, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides as a possible risk factor for the development of chronic diseases in humans (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2016. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beshwari MMM, Bener A, Ameen A, Al-Mehdi AM, Ouda HZ, Pasha MAH. Pesticide-related health problems and diseases among farmers in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Environ Health Res. 1999. doi: 10.1080/09603129973182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buralli RJ, Dultra AF, Ribeiro H. Respiratory and allergic effects in children exposed to pesticides—a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurmi OP, Lam KBH, Ayres JG. Indoor air pollution and the lung in low- and medium-income countries. Eur Respir J. 2012. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00190211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pongpiachan S, Hattayanone M, Cao J. Effect of agricultural waste burning season on PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) levels in Northern Thailand. Atmos Pollut Res. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2017.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy B, Goh N. A review on smoke haze in Southeast Asia: Deadly impact on health and economy. Quest Int J Med Heal Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanhueza PA, Torreblanca MA, Diaz-Robles LA, Schiappacasse LN, Silva MP, Astete TD. Particulate air pollution and health effects for cardiovascular and respiratory causes in Temuco, Chile: A wood-smoke-polluted urban area. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2009. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.59.12.1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mora AM, Hoppin JA, Córdoba L, et al. Prenatal pesticide exposure and respiratory health outcomes in the first year of life: Results from the infants’ Environmental Health (ISA) study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burney PGJ, Luczynska C, Chinn S, Jarvis D. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Eur Respir J. 1994. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07050954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gascon M, Kromhout H, Heederik D, Eduard W, Van Wendel De Joode B. Respiratory, allergy and eye problems in bagasse-exposed sugar cane workers in Costa Rica. Occup Environ Med. 2012. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez-Zamora MG, Zock JP, Van Wendel De Joode B, Mora AM. Respiratory health outcomes, rhinitis, and eczema in workers from grain storage facilities in Costa Rica. Ann Work Expo Heal. 2018. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxy068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunyer J, Pekkanen J, Garcia-Esteban R, et al. Asthma score: Predictive ability and risk factors. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;62(2):142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarvis D The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. Eur Respir J. 2002. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00046802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoppin JA, Jaramillo R, Salo P, Sandler DP, London SJ, Zeldin DC. Questionnaire predictors of atopy in a US population sample: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2011. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norén E, Lindh C, Rylander L, et al. Concentrations and temporal trends in pesticide biomarkers in urine of Swedish adolescents, 2000–2017. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2020;30(4):756–767. doi: 10.1038/s41370-020-0212-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeng HA, Pan CH. 1-Hydroxypyrene as a biomarker for environmental health. In: General Methods in Biomarker Research and Their Applications.; 2015. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7696-8_49 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alhamdow A, Lindh C, Albin M, Gustavsson P, Tinnerberg H, Broberg K. Early markers of cardiovascular disease are associated with occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Sci Rep. 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09956-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fix J, Annesi-Maesano I, Baldi I, et al. Gender differences in respiratory health outcomes among farming cohorts around the globe: findings from the AGRICOH consortium. J Agromedicine. 2020. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2020.1713274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andualem Z, Azene ZN, Azanaw J, Taddese AA, Dagne H. Acute respiratory symptoms and its associated factors among mothers who have under five-years-old children in northwest, Ethiopia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2020;25(1). doi: 10.1186/s12199-020-00859-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grutzen PJ, Andreae MO. Biomass burning in the tropics: Impact on atmospheric chemistry and biogeochemical cycles. Science (80-). 1990. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4988.1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Shen H, Chen Y, et al. Global organic carbon emissions from primary sources from 1960 to 2009. Atmos Environ. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.10.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferkol T, Schraufnagel D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-405PS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Låg M, Øvrevik J, Refsnes M, Holme JA. Potential role of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in air pollution-induced non-malignant respiratory diseases. Respir Res. 2020. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01563-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Díaz-Criollo S, Palma M, Monroy-García AA, Idrovo AJ, Combariza D, Varona-Uribe ME. Chronic pesticide mixture exposure including paraquat and respiratory outcomes among colombian farmers. Ind Health. 2020. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2018-0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chatzi L, Alegakis A, Tzanakis N, Siafakas N, Kogevinas M, Lionis C. Association of allergic rhinitis with pesticide use among grape farmers in Crete, Greece. Occup Environ Med. 2007. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.029835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perečinský S, Legáth Ľ, Varga M, Javorský M, Bátora I, Klimentová G. Occupational rhinitis in the Slovak Republic - A long-term retrospective study. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penagos H Contact dermatitis caused by pesticides among banana plantation workers in Panama. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2002.8.1.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penagos H, Ruepert C, Partanen T, Wesseling C. Pesticide patch test series for the assessment of allergic contact dermatitis among banana plantation workers in Panama. Dermatitis. 2004. doi: 10.2310/6620.2004.04014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slager RE, Simpson SL, Levan TD, Poole JA, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Rhinitis associated with pesticide use among private pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study. J Toxicol Environ Heal - Part A Curr Issues. 2010. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2010.497443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koureas M, Rachiotis G, Tsakalof A, Hadjichristodoulou C. Increased frequency of rheumatoid arthritis and allergic rhinitis among pesticide sprayers and associations with pesticide use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.