Abstract

Background:

Despite widespread availability of direct acting antivirals including generic formulations, limited progress has been made in global adoption of HCV treatment. Barriers to treatment scale-up include availability and access to diagnostic and monitoring tests, health care infrastructure and requirement for frequent visits during treatment.

Methods:

ACTG 5360 was a Phase IV, open-label, multi-country, single-arm trial across 38 sites on four continents. Key inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, evidence of active HCV infection (HCV RNA >1000 IU/mL) and HCV treatment naïve; compensated cirrhotics and HIV/HCV co-infected were included but their enrollment was capped. All participants received a fixed dose combination of oral sofosbuvir (400 mg)/velpatasvir (100mg) once daily for 12 weeks. The minimal monitoring (MINMON) approach comprised four components: (1) no pre-treatment genotyping; (2) entire treatment course (84 tablets) dispensed at entry; (3) no scheduled visits or laboratory monitoring; and (4) two remote contacts at Week 4 for adherence and Week 22 to schedule outcome assessment. Unplanned visits for any reason were permissible. The primary efficacy outcome was sustained virologic response defined as HCV RNA less than the lower limit of quantification measured at least 22 weeks post-treatment initiation; primary safety outcome was serious adverse events. These analyses were performed on the complete dataset of all participants who either had the primary outcomes assessment or the window to assess the primary outcomes had elapsed. All analyses presented are intent-to-treat using a missing=failure approach. This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03512210).

Findings:

Between October 22, 2018, and July 19, 2019, 400 participants enrolled across all 38 sites; 399 initiated treatment. At Week 24/SVR assessment visit, 89% (355/397) participants reported taking 100% of the trial medication during the 12 week treatment period. Overall, 379 of the 399 who initiated treatment achieved sustained virologic response (SVR: 95·0% [377/399]; 95% CI: 92·4, 96·7). Fourteen participants (3·5% [14/397]) reported serious adverse events between treatment initiation and Week 28; none were treatment related or led to treatment discontinuation or death. Fifteen participants of 399 (3.8% [15/399]) had unplanned visits; none were related to treatment.

Interpretation:

In this diverse global population of people with HCV, the MINMON approach with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir treatment was safe and achieved SVR comparable to standard monitoring observed in real-world data. Coupled with innovative case finding strategies, this strategy could be critical to the global HCV elimination agenda.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health and Gilead Sciences.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Sustained virologic response (SVR), Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir (SOF/VEL), Monitoring, HIV/HCV Coinfection

Background

Introduction of direct acting antivirals has revolutionized hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment, providing a critical tool for HCV elimination.1 The World Health Organization established ambitious targets to eliminate HCV by 2030, which requires that at least 90% of the 58 million chronically infected are diagnosed and 80% treated.2 To date, based on modelling estimates only 11 of 45 high-income countries are on track to achieve HCV elimination; Egypt and Georgia are the only low- and middle-income countries on track.3

Major challenges to widespread scale-up of HCV treatment have been related to treatment cost and access. While costs have frequently been cited as a barrier, they have significantly declined in recent years,4 particularly with the production of generic formulations.4,5 In low- and middle-income countries where over 80% of the persons with chronic HCV reside,6 costs associated with recommended diagnostics such as pre-treatment genotyping and on-treatment monitoring can be higher than the cost of medications or are often unavailable (e.g., HCV genotyping).5,7 Additionally, overburdened health care infrastructure is a key challenge to expanded access to HCV treatment, which is now further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic threatening public health programs globally. Progress toward HCV elimination has stalled during the pandemic5; models suggest this will result in excess HCV-related mortality underscoring the urgent need for simple, safe and efficacious treatment algorithms.8 While US and European Guidelines recommend simplified treatment algorithms in some patient populations,9,10 there are limited data on “simplified” models of HCV treatment monitoring, particularly from low- and middle- income settings.11,12,13

The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) A5360, “Minimal Monitoring” (MINMON) trial, examined the efficacy and safety of a minimal (in-person) monitoring strategy of HCV treatment delivery in a diverse global population living with HCV.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

A5360 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03512210) was a phase IV, multi-country, open-label, single-arm trial designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a minimal monitoring approach of delivering interferon- and ribavirin-free, pan-genotypic direct acting antivirals to HCV treatment naïve participants with evidence of active HCV infection. Four hundred participants were recruited at 38 ACTG-affiliated, National Institutes of Health Division of AIDS (DAIDS) certified clinical research sites (Supplementary Figure S1) across five countries (Brazil, South Africa, Thailand, Uganda, and the United States). All clinical research sites were nested within existing infectious diseases clinics and all provide clinical care to people living with HIV. Most sites were affiliated with universities. The clinicians at the sites varied depending on the study site and ranged from primary care physicians to infectious disease specialists. Enrollment in the United States was limited to 132 participants across the 31 sites; four enrollment slots were reserved for each of the US sites. There were no caps or reserved slots for enrollment across the seven international sites.

Participants were either recruited from within the clinic population or from the community via referrals. All participants were ≥18 years old with active HCV infection (RNA >1000 IU/mL ≤35 days to entry) and HCV treatment naïve. Liver disease stage was determined by Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) Index,14 which is estimated using age, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and platelet count. Cirrhosis was defined as FIB-4 score ≥3·25. Participants with compensated cirrhosis (FIB-4 ≥3·25 and Child-Turcotte- Pugh score ≤6) were eligible but limited to no more than 80 participants to reflect that 10–20% of people living with HCV worldwide are cirrhotic; persons with decompensated liver disease were excluded. People with HIV were eligible if suppressed (HIV RNA <400 copies/mL) on non-efavirenz containing antiretrovirals, or HIV treatment naïve with CD4 >350 cells/µL within 90 days prior to entry. Enrollment of people with HIV was limited to no more than 200 participants to ensure balance of HCV mono-infected and HIV/HCV co-infected participants. Pregnancy, breast-feeding, or evidence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (HBsAg positive) were exclusion criteria; participants with resolved HBV infection [anti-hepatitis B core (HBc) positive] with or without positive hepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs) were eligible. Participants provided written informed consent, including permission for and preferred mode of remote contact. Other major investigations performed as part of screening for the trial included hematology, liver function tests and blood chemistries. Detailed eligibility criteria and laboratory and clinical assessments performed as part of the trial are available in the study protocol that is publicly available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ProvidedDocs/10/NCT03512210/Prot_001.pdf.

The protocol was approved by Institutional Review/Ethical Review Boards of all 38 participating sites. Interim reviews for conduct and safety were performed at least yearly by a network appointed independent study monitoring committee.

Procedures

All persons consenting to be screened for the trial were evaluated for eligibility. Those eligible and willing to enroll in the trial were scheduled for an entry visit. Due to the requirement for documentation of active HCV infection (HCV RNA>1000 IU/ml) prior to enrollment, the median time from screening to enrollment was 19 days (Range: 0, 35 days).

All participants received a single-tablet fixed dose combination containing 400 mg of sofosbuvir and 100 mg of velpatasvir taken by mouth once daily for 12 weeks with or without food. The MINMON intervention strategy constituted four elements: (1) no pre-treatment HCV genotype assessment; (2) dispensation of the entire treatment course at entry (3 bottles containing 28 tablets each); (3) no scheduled clinic or laboratory monitoring visits prior to efficacy outcome assessment; and (4) two points of remote contact―Week 4 post- treatment initiation to assess adherence and update contact information, and Week 22 to update contact information and schedule the outcome assessment visit. Study staff could remotely contact participants using the participant’s preferred method (e.g., email, SMS text message, or social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook messenger, etc.). All participants were provided with a number that they could contact research staff if they had any questions or concerns related to the trial or trial medication. Unplanned clinic visits for any reason were allowed prior to the Week 24 visit including for repeat laboratory tests for laboratory abnormalities detected during study entry. To maintain compliance with our minimum monitoring intervention, no attempts were made to contact participants in-person if remote contact failed. Participants were scheduled to be followed for 72 weeks following treatment initiation; results through the primary efficacy outcome assessment scheduled at Week 24 are presented here.

HCV RNA for SVR assessment was quantified using either the Roche COBAS® HCV Quantitative nucleic acid assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) with a limit of detection of 15 international units (IU) per milliliter or the Abbott RealTime HCV assay (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) with a limit of detection of 12 IU/ml. All testing was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions at DAIDS-certified laboratories. HCV genotype was determined using stored baseline specimens after all participants completed their Week 24/SVR primary outcome assessment visit. Sanger sequencing was utilized to obtain a short (~325 bp) fragment sequence of the NS5B region and phylogenetic determination of genotype was performed using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST®).15

Site investigators were directed to report all serious and Grade 3 or higher adverse events, and adverse events associated with study treatment changes. Adverse event severity was graded per the DAIDS Grading Table.16

Substance use, alcohol use, and smoking were assessed with the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST)17,18 which was interviewer-administered at study entry and Week 24/SVR assessment visit. An aggregate substance use variable considered use of amphetamines, cocaine, hallucinogens, opioids, or sedatives. Active substance use was defined as self-reported use in the prior 3 months.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome was sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as plasma HCV RNA less than the assay’s lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) from the first sample obtained at least 22 weeks (and up to 76 weeks) following treatment initiation, corresponding to at least 10 weeks after the scheduled completion of treatment among all participants who initiated treatment irrespective of subsequent treatment disposition. Participants with HCV RNA at or above the LLOQ as well as those without any HCV RNA results in the time period specified above, were defined as non-responders. The primary safety outcome was any serious adverse event, defined as per the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines, occurring up to 28 weeks following treatment initiation, corresponding to the end of the scheduled week 24 visit window, among all participants who had at least one visit post entry.

Secondary outcomes of interest included occurrence of unplanned visits, adverse events, and premature discontinuation of study medication. Unplanned visits were defined as any visit a participant made to the study site prior to the Week 24/SVR assessment. Adverse events (AEs) were defined as any unfavorable and unintended sign (including an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom, or diagnosis that occurred in a study participant during the conduct of the study regardless of the attribution (i.e., relationship of event to study medication) between study entry and Week 28 (the upper window for the Week 24 visit where SVR was assessed). The Week 24/SVR visit was also the first visit study participants were scheduled to be seen post-treatment completion where a history of adverse events could be elicited from the participants. These included any occurrence that were new in onset or aggravated in severity or frequency from the baseline condition. Premature discontinuation was assessed by self-report if the study participant reported stopping treatment prior to the completion of the 84 tablets.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size of 400 participants in a single group was based on the Wilson score 95% confidence interval (CI) from an expected SVR from 92% to 99% where precision of the 95% CI ranged from 5·4% to 2·25% points, respectively. If eight or fewer SVR non-responders out of 400 were observed, the confidence interval would be fully bounded above 96%. Conversely, if 29 or more SVR non-responders out of 400 were observed, the confidence interval would be fully bounded below 95%. Under a true SVR of 98·5%, probability of the lower confidence bound >96% was 0·85; similarly, under a true SVR of 92%, probability of the upper confidence bound <95% was 0·74. The trial was sized on the single-group primary efficacy outcome of the entire sample, and not for any subgroups.

The proportion of the trial sample experiencing SVR was calculated by the number who achieved SVR divided by all participants who initiated treatment utilizing a missing=failure approach. The proportion experiencing the safety outcome was the number of participants with a serious adverse event divided by the number who initiated treatment and had at least one post treatment assessment. Two-sided 95% CIs for each summary measure were calculated using Wilson score method for binomial proportions. SVR proportion by select baseline characteristics were calculated; no hypothesis testing was performed. Subgroups defined a priori included country, cirrhosis classification, HIV infection status, sex at birth, and HCV genotype. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Statistical Package, Version 9·4 (USA).

There were two planned interim reviews for efficacy, with modification guidelines based on unacceptably low SVR. The first interim review of efficacy was planned at approximately 25% information (i.e., SVR outcomes available on ~100 participants). Because recruitment from international locations occurred later in calendar time, the second review was planned at ~58% information (i.e., SVR outcomes available on at least 230 participants), to allow at least 40% representation of the interim trial sample from participants from research locations outside the US. The monitoring guideline of unacceptably low SVR was if the upper confidence bound on a one-sided, 99.9% confidence interval (by Wilson score method for binomial proportions) was <95%. With 100 participants, this guideline would have been met if 14 or more SVR non- responders were observed (i.e., calculated SVR <86/100). Between reviews by the independent committee, the study team monitored study conduct and safety periodically as per the trial’s monitoring plan. This trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03512210).

Role of Funding Source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author takes final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication

Results

Study Population Characteristics

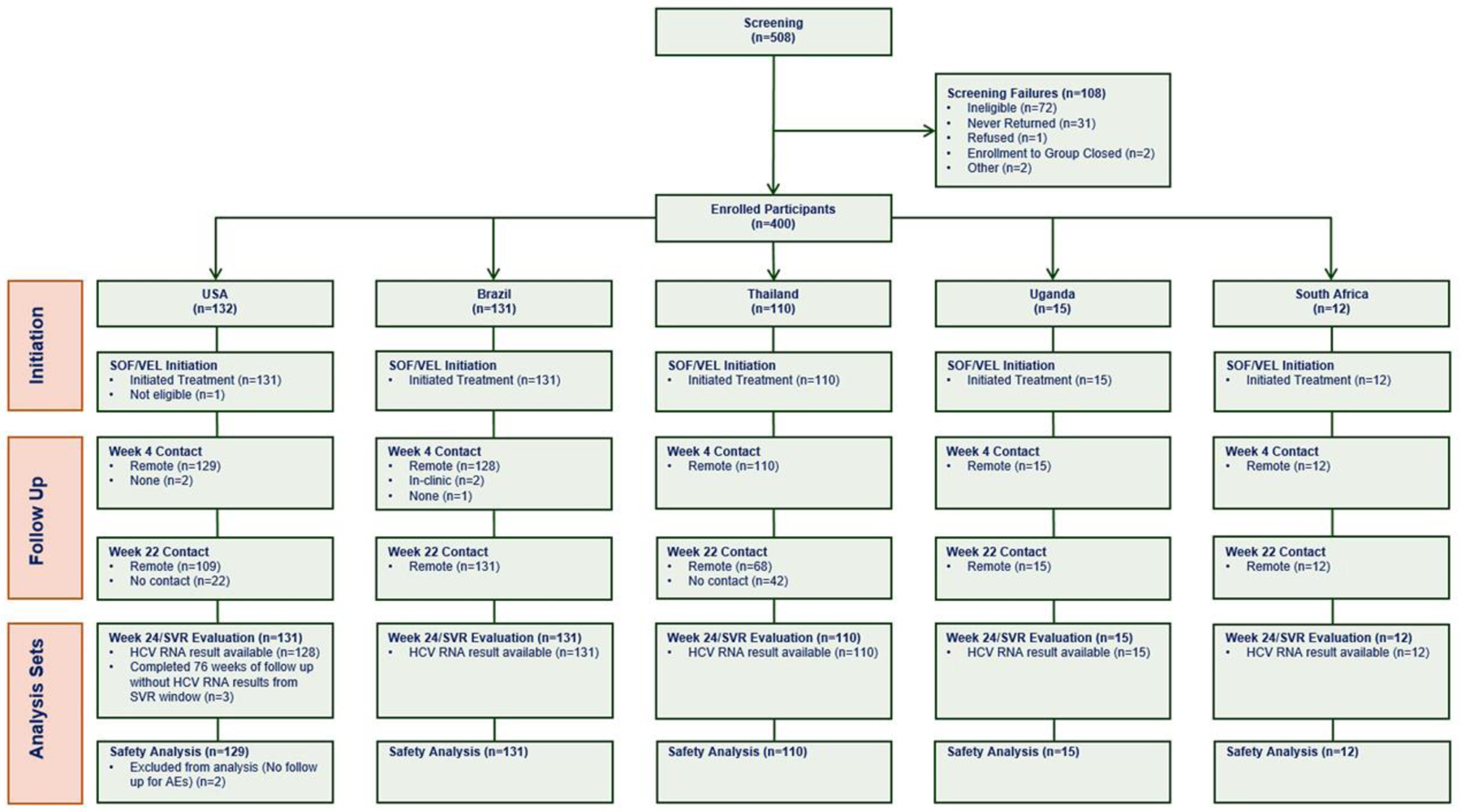

A total of 508 formal trial screenings were conducted to enroll 400 participants between October 22, 2018, and July 19, 2019; reasons for exclusion from enrollment are provided in Figure 1. Of 72 instances of screen failure, over half (54% [39/72]) were due to undetectable HCV RNA. Of 400 participants enrolled in the trial, 399 initiated treatment; one participant reported use of a contraindicated medication at the entry visit and did not start treatment. Of 399 participants initiating treatment, 397 (99·5% [397/399]) had at least one follow-up visit post-enrollment.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5360 (MINMON) trial.

The median age was 47 years and 35% (139/399) were assigned female sex at birth; 22 (6% [22/399]) identified across the transgender spectrum. Most participants were either non-Hispanic Asian (28% [113/399]), non-Hispanic white (25% [99/399]), Hispanic/Latinos of any race (24% [95/399]), or non- Hispanic black (14% [57/399]). Self-reported current substance use was 14% (56/397); current alcohol use was reported by 40% (161/397) of the participants.

At entry, 34 (9% [34/399]) of the 399 participants had compensated cirrhosis, and 121 of 374 (32% [121/374]) with HBV panel (hepatitis B surface antibody [anti-HBs], anti-HBc, HBsAg) available had evidence of resolved HBV infection. The median HCV RNA was 6·1 log10 IU/mL (Q1, Q3: 5·6, 6·6). The HCV genotype distribution in the 399 participants was: genotype 1 (62% [249/399]), genotype 2 (7% [26/399]), genotype 3 (20% [n=80/399]), genotype 4 (7% [26/399]), genotype 5 (1% [n=3/399]), genotype 6 (3% [11/399]), 7 (< 1% [1/399]), and unknown (1% [3/399]). Of the 42% (166/399) participants with HIV, 164 (99% [164/166]) were on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Detailed participant characteristics by country are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Study Entry by Country of Enrollment

| Overall (n=399) | US (n=131) | Brazil(n=131) | South Africa (n=12) | Thailand (n=110) | Uganda (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (years, 25th, 75th percentile) | 47 (37, 57) | 50 (37, 58) | 51 (42, 62) | 51.5 (43.5, 58) | 41 (33, 47) | 35 (27, 49) |

| Biological sex assigned at birth, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 260 (65) | 86 (66) | 59 (45) | 9 (75) | 91 (83) | 15 (100) |

| Female | 139 (35) | 45 (34) | 72 (55) | 3 (25) | 19 (17) | – |

| Gender Identity, n (%) | ||||||

| Cisgender | 377 (94) | 129 (98) | 129 (98) | 12 (100) | 92 (84) | 15 (100) |

| Transgender spectrum* | 22 (6) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | – | 18 (16) | – |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 99 (25) | 72 (55) | 23 (18) | 4 (33) | – | – |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 57 (14) | 29 (22) | 6 (5) | 7 (58) | – | 15 (100) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 113 (28) | 2 (2) | – | 1 (8) | 110 (100) | – |

| Hispanic/Latino, any race | 95 (24) | 23 (18) | 72 (55) | – | – | – |

| Other | 35 (9) | 5 (4) | 30 (23) | – | – | – |

| History of substance use, n (%) | ||||||

| Currently | 56 (14) | 27 (21) | 17 (13) | 2 (17) | 10 (9) | – |

| Previously | 170 (43) | 81 (62) | 36 (28) | 2 (17) | 51 (46) | – |

| Never | 171 (43) | 23 (18) | 76 (58) | 8 (67) | 49 (45) | 15 (100) |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | ||||||

| Currently | 161 (40) | 60 (46) | 43 (33) | 5 (42) | 46 (42) | 7 (47) |

| Previously | 179 (45) | 59 (45) | 56 (43) | 3 (25) | 56 (51) | 5 (33) |

| Never | 57 (14) | 12 (9) | 30 (23) | 4 (33) | 8 (7) | 3 (20) |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | ||||||

| Currently | 140 (35) | 83 (63) | 29 (22) | 3 (25) | 25 (23) | – |

| Previously | 124 (31) | 31 (24) | 43 (33) | 3 (25) | 45 (41) | 2 (13) |

| Never | 133 (33) | 17 (13) | 57 (44) | 6 (50) | 40 (36) | 13 (87) |

| Compensated cirrhosis **, n (%) | 34 (9) | 9 (7) | 13 (10) | 2 (17) | 10 (9) | – |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||||||

| Genotype 1a | 177 (44) | 72 (55) | 45 (34) | 1 (8) | 59 (54) | – |

| Genotype 1b | 72 (18) | 18 (14) | 49 (37) | 1 (8) | 4 (4) | – |

| Genotype 2 | 26 (7) | 20 (15) | 4 (3) | 2 (17) | – | – |

| Genotype 3 | 80 (20) | 17 (13) | 28 (21) | 2 (17) | 33 (30) | – |

| Genotype 4 | 26 (7) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 3 (25) | 1 (1) | 14 (93) |

| Genotype 5 | 3 (1) | – | – | 3 (25) | – | – |

| Genotype 6 | 11 (3) | – | – | – | 11 (10) | – |

| Genotype 7 | 1 (<1) | – | – | – | – | 1 (7) |

| Median log10 HCV RNA in IU/mL (25th, 75th percentile) | 6·1 (5·6, 6·6) | 6·2 (5·6, 6·6) | 5·8 (5·4, 6·2) | 6·1 (6·0, 6·6) | 6·6 (6·0, 6·9) | 5·8 (5·4, 6·2) |

| Median BMI in kg/m2 (25th,75th percentile) | 25·0 (22·2, 28·7) | 26·6 (23·7, 31·9) | 26·0 (22·3, 29·8) | 24·3 (22·3, 27·1) | 23·1 (20·5, 25·2) | 22·9 (21·9, 25·6) |

| Persons with HIV (PWH), n (%) | 166 (42) | 43 (33) | 28 (21) | 5 (42) | 89 (81) | 1 (7) |

| Currently on antiretroviral therapy, n (% of PWH) | 164 (99) | 42 (98) | 28 (100) | 5 (100) | 88 (99) | 1 (100) |

| HIV RNA <400 copies/mL, n (% of PWH) | 164 (99) | 42 (98) | 28 (100) | 5 (100) | 88 (99) | 1 (100) |

Identities across the transgender spectrum endorsed included the following: gender queer (n=15 persons assigned male at birth), female or transgender female (n=5), gender non- conforming (n=1 person assigned male at birth), transgender male (n=1)

Based on FIB-4 and CTP scoring

Missing data: substance use (n=2 from Brazil), alcohol and tobacco use (n=2 from Brazil), HCV genotype (n=3, 2 from Thailand and 1 from United States); all percentages calculated based on observed data

Implementation of the MINMON Intervention

Week 4 and Week 22 remote contact was successful in 394 (99% [394/399]) of 399 and 335 (84% [335/399]) of 399 participants, respectively. Three participants reported losing study medications. One reported the loss 14 days after the interruption occurred and, per protocol, study medications were not replaced. The two other participants reported losing their third bottle after interruptions of 4 and 7 days, and were provided with replacements. Most (91% [362/397]) self-reported completing all study medications between 77 and 91 days (expected 84 days), 6% (24/397) reported taking between 92 and 105 days, and 2% (9/397) reported taking 106 days or longer to complete their study medications. Overall, 355 (89% [355/397]) of 397 self-reported taking 100% of medications within the treatment period at the Week 24/SVR visit, and 30 (8% [30/397]) of 397 reported taking between 90 and 99%; the remainder reported taking less than 90% of study medication.

Fifteen participants (3.8% [15/399]) of 399 had 21 unplanned in-person visits between entry and Week 22. The most common reasons were abnormal laboratory results at entry (n=8) or non-AE related clinical events (n=6). Three unplanned visits were associated with an adverse event, none of which were related to study medication. None of the unplanned visits were associated with treatment discontinuation. Details of all unplanned study visits are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Two participants were lost-to-follow-up before primary outcome assessment with no information available after the entry visit – these two participants were considered non-responders in the primary efficacy analyses. One additional participant returned for the SVR assessment prior to the SVR visit window and never returned thereafter; hence, this participant was also considered as missing the SVR visit. Additionally, two participants discontinued treatment early―one due to medication loss and the other due to a Grade 1 adverse event.

Primary Efficacy Outcome

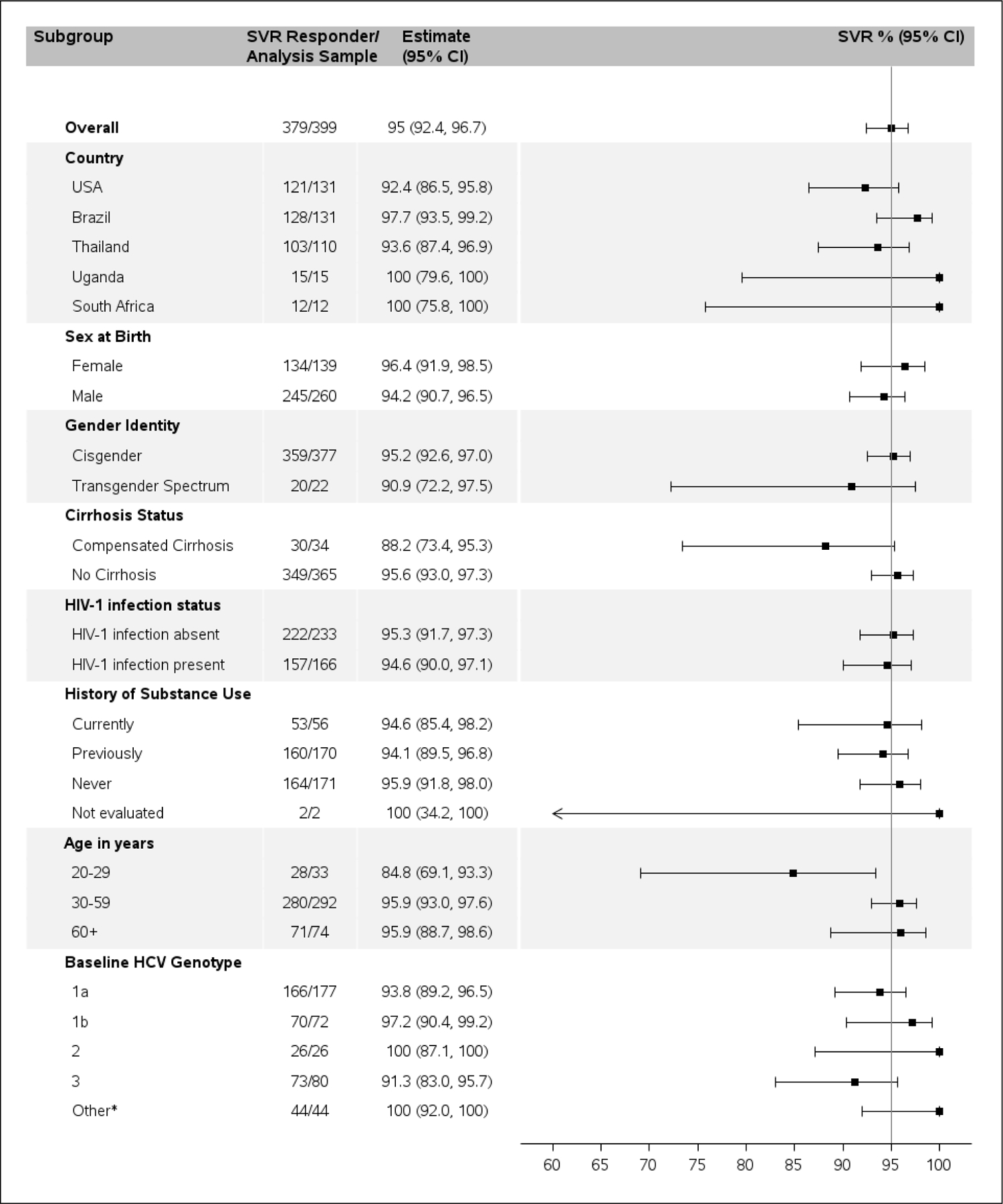

Of 399 participants who initiated treatment, 379 (95·0% [379/399]) achieved SVR (95% CI: 92·4%, 96·7%). By country, SVR ranged from 92·4% (121/131) in the United States to 100% in South Africa (12/12) and Uganda (15/15). Thirty of 34 cirrhotic (88·2% [30/34]; 95% CI: 73·4%, 95·3%) and 349 of 365 non-cirrhotic (95·6% [349/365]; 95% CI: 93·0%, 97·3%) participants achieved SVR. Among participants living with HIV, 94·6% (157/166) achieved SVR. Across genotypes, SVR ranged from 91·3% (73/80) in HCV genotype 3 to 100% within genotypes 2 (26/26), 4 (26/26), 5 (3/3), 6 (11/11), and 7 (1/1). SVR among participants with current, former, and no history of substance use were 94·6% (53/56), 94.1% (160/170), and 95·9% (164/171), respectively. Figure 2 presents SVR by participant characteristics at entry.

Figure 2.

Sustained virologic response overall and by subgroups defined by various participant baseline characteristics.

*Other included genotype 4, 5, 6, 7, and 3 with no genotype data.

Primary Safety Outcome

Fourteen participants out of 397 (3·5% [14/397]) experienced at least one serious adverse event (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2); five occurred while participants were on treatment and none were associated with study medication or resulted in treatment discontinuation or death. Two Grade 4 adverse events were reported: one myocardial infarction and one acute exacerbation of anemia in a participant with known pernicious anemia. Twenty-three participants out of 397 (5·8% [23/397]) reported 28 adverse events.

Table 2.

Unplanned Visits, and Adverse Event Occurring from Enrollment through Week 28 (n=397)

| Overall (n=397) | United States (n=129) | Brazil (n=131) | South Africa (n=12) | Thailand (n=110) | Uganda (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNPLANNED VISITS * | ||||||

| Participants reporting at least 1 unplanned visits, n (%)* | 15 (3·8) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (17) | 4 (4) | 3 (20) |

| Total number of unplanned visits, n | 21 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Reason for unplanned visits, n | ||||||

| Lab evaluations | 8 | 1 | – | 4 | 3 | – |

| Adverse event | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Clinical event (non-AE) | 6 | – | 3 | – | – | 3 |

| Other** | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – |

| SERIOUS ADVERSE EVENTS: PRIMARY SAFETY OUTCOME | ||||||

| Total number of participants reporting at least one SAE, n (%) | 14 (3·5) | 7 (5) | – | 2 (17) | 5 (5) | – |

| Toxicity grade, n | ||||||

| Grade 3 | 12 | 7 | – | 1 | 4 | – |

| Grade 4 | 2 | – | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| SAE occurring while on study medication, n | 5 | 1 | – | 1 | 3 | – |

| SAE leading to discontinuation of study drug, n | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| SAE related to study medication, n | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Death, n | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ADVERSE EVENTS (EXCLDUING SAEs): SECONDARY SAFETY OUTCOME | ||||||

| Participants reporting at least one AE (excluding SAEs), n (%) | 23 (5·8) | 7 (5) | 8 (6) | 1 (8) | 7 (6) | – |

| Total number of adverse events, n | 28 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 7 | – |

| AE occurred while on study medication, n | 8 | 7 | 1 | – | – | – |

| AE related to study medication | 5 | 4 | 1 | – | – | – |

| AE leading to discontinuation of study drug, n*** | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

All participants who initiated treatment were included in the denominator for unplanned visits (n=399)

Other included unscheduled study visit outside of window (n=1), visited site to clarify query on study treatment (n=1), visited site for counseling and collect Vitamin B12 for management of pernicious anemia (n=1), participant newly diagnosed with HIV and wanted to initiate ART (n=1)

One case of abdominal distension attributed to study product resulted in discontinuation

Eight occurred while on study medication and 5 (diarrhea [n=2], headache [n=1], fatigue [n=1], and abdominal bloating [n=1; resulted in discontinuation reported above]) were attributed to the study medication.

Characteristics of Non-responders

Twenty participants failed to achieve protocol defined SVR; two were lost-to-follow-up after entry, and one returned for SVR evaluation early. Seventeen participants had detectable HCV RNA greater than the lower limit of quantification at the Week 24/SVR visit, of whom one discontinued medication after 6 days due to loss. The remaining 16 participants completed treatment―10 had genotype 1 and 6 had genotype 3 infections. Four participants had compensated cirrhosis. Twelve of the 16 (75% [12/16]) non-responders reported taking 100% of their study medication, two of 16 (12.5% [2/16]) reported taking 90–99%, and two of 16 (12.5% [2/16]) reported taking <90%. Three of the 20 non-responders (15% [3/20]) reported current substance use. Detailed information on the 20 non-responders is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Select Characteristics of Participants Who Did Not Achieve Sustained Virologic Response

| Country | Age in years | Sex at birth (M/F) | Current substance use at entry (Y/N) | Compensated Cirrhosis based on FIB-4/CTP (Y/N) | HIV co-infection (Y/N) | Self-reported time to completion Of SOF/VEL in days | Self-reported adherence at Week 24/SVR visit | HCV genotype at entry | HCV RNA at entry in log10 IU/ml | HCV RNA at Week 24/SVR assessment in log10 IU/ml | Adverse Event (Y/N) | Unplanned Visit (Y/N) | Lost medication/premature discontinuation (Y/N) | Lost to follow-up (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 38 | M | N | N | Y | 84 | 100% | 1a | 5.6 | 5.5 | N | N | N | N |

| Brazil | 66 | M | Y | N | N | 84 | 100% | 3a | 6.0 | 5.6 | N | N | N | N |

| Brazil | 59 | F | N | Y | N | 85 | 100% | 3a | 5.5 | 6.1 | N | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 27 | M | N | N | Y | 83 | 100% | 1a | 6.4 | 6.7 | N | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 47 | M | N | N | Y | 84 | 100% | 3b | 6.3 | 6.5 | N | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 25 | M | N | N | Y | 84 | 100% | 1a | 5.9 | 5.4 | N | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 51 | M | N | Y | Y | 84 | 100% | 3a | 6.5 | 5.8 | N | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 59 | M | N | Y | N | 85 | 100% | 3b | 6.5 | 4.1 | Y | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 33 | M | N | N | Y | 88 | 100% | 1a | 6.8 | 7.1 | Y | N | N | N |

| Thailand | 20 | F | N | N | N | 157 | 50–74% | 3b | 5.8 | 3.3 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 24 | F | N | N | N | 6 | <50% | 3a | 4.1 | 5.5 | N | N | Y | N |

| US | 46 | M | N | N | N | 85 | 100% | 1a | 6.5 | 6.7 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 62 | M | N | Y | N | 85 | 100% | 1a | 6.1 | 6.5 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 60 | M | N | N | N | 85 | 100% | 1a | 5.5 | 4.6 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 58 | M | Y | N | N | 87 | 90–99% | 1a | 6.2 | 4.7 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 51 | M | N | N | Y | 95 | 90–99% | 1a | 6.2 | 6.3 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 34 | M | N | N | Y | 110 | 75–89% | 1b | 5.8 | 5.4 | N | N | N | N |

| US | 25 | F | N | N | Y | – | – | 1a | 5.3 | N/A | N | N | – | Y |

| US | 55 | M | Y | N | N | – | – | 1a | 5.5 | N/A | N | N | – | Y |

| US | 59 | F | N | N | N | 51 | <50% | 1b | 6.4 | N/A | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Note: Two participants were lost-to-follow-up post-entry with no follow up information beyond baseline; M=male; F=female; Y=Yes; N = No.

N/A: Sample not available within SVR window

Discussion

The MINMON trial recruited a diverse global sample of people living with HCV including people with compensated cirrhosis and HIV infection and achieved HCV cure (SVR) of 95% despite minimal laboratory monitoring and in-person visits. This finding has important implications for HCV elimination, particularly in the face of public health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic that threaten public health programs. The MINMON approach can specifically inform HCV elimination programs by providing a solution that overcomes barriers of in-person contact and limited resources.

In other large trials of HCV treatment with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, observed SVR was 95%−99%.19,20 Unlike MINMON, however, in these trials, participants were seen at Weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 post entry. Such intensive follow-up requires extensive resources that is not feasible outside of clinical trials, especially in resource-constrained settings where the majority of people living with HCV reside. A recent meta-analysis of over 5,500 persons enrolled in 12 clinical cohorts across Canada, Europe, and the United States observed an SVR of 92·3% when accounting for losses-to-follow-up, non-adherence, treatment discontinuation and death.21 Similarly, the SVR from a Canadian cohort treated with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir was 94·6%.22 The 95.0 % overall SVR observed in MINMON is comparable to these registrational trials where sofosbuvir/velpatasvir was delivered with intensive clinical and laboratory monitoring and more frequent in-person visits for medication refills, or observational cohorts in the setting of a standard of care with similar levels of clinical visits and monitoring.

Few studies have evaluated simplified HCV treatment delivery.11,12,13 Most reduced the frequency of on-treatment laboratory monitoring but still required pre-treatment HCV genotyping and medication dispensation at multiple time points.11,13 Most comparable to MINMON is the SMART-C trial, a randomized clinical trial comparing standard to simplified monitoring using a fixed-dose combination of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir which required three tablets to be taken orally daily for 8 weeks.12 However, this trial excluded people with cirrhosis, included only 27 (7%) individuals living with HIV and HCV and required pre-treatment HCV genotyping. While similar to MINMON in that all medications were dispensed at entry, the on-treatment remote contact in the simplified arm of SMART-C was at Weeks 4 and 8. SMART-C used transient elastography or AST to platelet ratio index to stage fibrosis as opposed to MINMON, where cirrhosis classification was based on the readily accessible and low-cost FIB-4 score, which is based on age, routine laboratory assessment of liver enzyme levels, and platelet count, and among those with FIB-4 score >3.25, the Child-Turcotte-Pugh Score, which is based on presence of signs/symptoms and routine laboratory assessments of total bilirubin, albumin, and international normalized ratio (INR). The overall SVR observed in the simplified arm of the SMART-C trial was 92%, compared to 95% that was observed in the standard monitoring arm.

There are several strengths of the MINMON trial. This is the first trial of a simplified monitoring approach to eliminate pre-treatment HCV genotyping and to include people with evidence of compensated cirrhosis. The elimination of pre-treatment genotyping is critical to the scale-up of HCV therapy particularly in low and middle-income country settings where this testing is often unavailable, and when available, is usually associated with high cost. Second, this is the first simplified monitoring study to include a racially and globally diverse population from high- to low-income settings. Third, dispensation of full treatment course at baseline and elimination of all on-treatment clinical and laboratory monitoring reduces patient, provider, and health system costs. This is also particularly relevant to populations who are mobile such as long-distance truckers who have a high HCV prevalence and may not be able to accommodate four weekly appointments for refills given the nature of their occupation.23 While this trial was designed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the elimination of in-person contact is particularly relevant now in the context of broad-based public health interventions during state and nationwide lockdowns which limit mobility. Further, telemedicine and remote contact have become the norm in the delivery of health care in several countries, especially during lockdowns. Fourth, tests used here to assess cirrhosis (FIB-4) and HBV surface antigen positivity are routinely available globally. Despite 32% of the participants having resolved HBV infection and 9% with compensated cirrhosis, we did not observe any serious adverse events related to liver dysfunction.24,25 Fifth, participants from each genotype 1–7 achieved SVR >91%, with confidence intervals including 95%. Sixth, this trial included people living with HIV (42% of study sample) and current substance use (14%) with observed SVR over 94% within each of these subgroups. SVR in participants with HIV was similar to the 95% SVR observed in the ASTRAL-5 HIV/HCV trial, which required more intensive follow-up and monitoring.26

There are, however, some limitations that need to be considered in the interpretation of these findings. A weakness of this trial was the absence of a concurrent comparator group; that is, this was a single group trial with no control group receiving standard monitoring. However, extensive experience with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and other HCV regimens in observational cohorts provided for an expected SVR of approximately 95%.21,22,27

The small number of participants in certain subgroups limits the ability to make strong conclusions regarding these populations. Of particular importance are persons who with HCV genotype 3 infection or compensated cirrhosis where the observed SVR was lower than 95% in this trial – however, of importance, the 95% CI for SVR in these groups included 95%. HCV genotype 3 infection is common in some regions where this trial was conducted and 80 study participants had genotype 3 infection. Of these, nine had genotype 3b infection which may be more likely to have NS5A resistance associated substitutions28; of these nine participants, three did not achieve SVR. The significance of this observation in a small subgroup of participants is uncertain but is unlikely to be the consequence of the minimal monitoring strategy. From the perspective of global HCV elimination, treatment implementation in the absence of HCV genotype testing is a critical element of the simplification strategy, reducing cost and increasing uptake especially in settings where genotyping may not be available.

While this trial was not designed or powered to examine subgroup differences, we are able to examine the SVR in MINMON in the context of SVR reported from other trials and large cohorts of persons taking SOF/VEL. For example, among participants with genotype 3 infection MINMON SVR of 91.3% was numerically lower than the 95% observed in ASTRAL-3, but the 95% confidence intervals for the two estimates overlapped (95% CI in ASTRAL-3 for genotype 3: 92.0 to 98.0). In an analysis of persons with genotype 2 and 3 infection outside of a trial setting, the SVR among those with genotype 3 and taking SOF/VEL was 92%.29 Similarly, in MINMON, SVR of 88.2% among those with compensated cirrhosis can be compared with a range of 90 thru 99% (depending on genotype) in the ASTRAL 2–4 trials. Additionally, in a large observational cohort of persons taking SOF/VEL, 126 (10.9%) of 1147 with cirrhosis failed to achieve SVR, which is comparable to the 88.2% SVR observed in this trial. Therefore, while the observed point estimate of SVR in certain sub-groups was lower than 95%, the observed rates were comparable to other available observational and clinical trial data using of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir with standard monitoring.

The eligibility requirement of HIV RNA suppression among participants with HIV selected for a subset of persons with documented medication adherence and may not be generalizable to all people living with HIV/HCV. Since all trial participants received sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, these results may not apply to other HCV regimens. Further, while we included people with a history of drug use, we did not have an adequate number of participants who reported a history of active injection ―future studies should evaluate this approach among people who inject drugs who may face additional adherence challenges but a critical population to be reached for HCV elimination. The small number of participants between 18 and 29 years of age limited the ability to make generalizations about the use of MINMON in young adult populations who may need additional interventions to improve adherence. Finally, another subgroup that will also need to be considered in future research are treatment experienced individuals.

Lastly, this trial was implemented at NIH-certified research sites, which may not reflect the care available in other treatment settings. However, the approach and laboratory assays used in the trial are readily available in many primary health care settings; the introduction of novel point-of-care and high throughput diagnostics for confirmation of active infection by RNA or HCV Core antigen could accelerate the implementation of such a simplified treatment approach globally.30,31 Further, in several national HCV programs across the world, task-shifting, transition to point-of-care testing and elimination of certain monitoring components are already being implemented with promising results.32,33 Yet, all require some level of on-treatment in-person contact at least for medication refills. It is critical to evaluate the utility of the MINMON approach in such programs to further simplify HCV treatment by eliminating all on-treatment visits to help accelerate the global HCV elimination agenda.

Limitations notwithstanding, the MINMON approach with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir used in this study is a simple, safe and efficacious way to deliver treatment globally to HCV-treatment naïve HCV or HCV/HIV co-infected persons without evidence of decompensated cirrhosis. Coupled with innovative case finding strategies and point-of-care diagnostics, this streamlined approach will play a critical role in achieving global HCV elimination.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

We conducted a search in PubMed on June 29, 2020, using the search terms “(hepatitis C[Title]) AND (treatment[Title] OR direct acting antivirals[Title])) AND (simplified[Title] OR minimal[Title])” which returned 13 articles. No date or language restrictions were used.

Since the introduction of all oral highly efficacious pan-genotypic direct acting antiviral (DAA) therapies for hepatitis C virus infection, there have been calls for simplification of treatment delivery to facilitate achieving the World Health Organization’s (WHO) ambitious HCV elimination targets. Indeed, the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL) and the WHO have included in their guidelines language on the simplification of HCV treatment delivery in select sub-populations. However, most of this guidance is based on expert opinion and not necessarily grounded in strong scientific data. To, date there have been few well-designed trials that have evaluated strategies to simplify HCV treatment delivery. Moreover, the data from these few trials have some limitations. First, all published trials required pre-treatment genotyping. Second, these studies used a variety of tools to classify cirrhosis including transient elastography which may not be readily available in all settings globally. Third, individuals with compensated cirrhosis were excluded from most of these trials and there was limited representation of HIV/HCV co-infected persons. Fourth, only one of these trials (Dore et al) dispensed the entire treatment course at study entry. Fifth, and most importantly, the majority of these trials including the largest trial (Dore et al) included only participants from high-income countries – over 80% of people living with HCV reside in low- and middle-income country settings. To our knowledge, no trial to date has evaluated a minimal in-person monitoring approach in a globally diverse population including persons with compensated cirrhosis and a good representation of those living with HIV/HCV co-infection.

Added value of this study

The MINMON trial demonstrates that the delivery of HCV treatment can be simplified without compromising safety or efficacy in a globally diverse population of participants from high-, middle- and low-income income settings even those with compensated cirrhosis and HIV/HCV co-infection. Further, the use of simple, easy to obtain laboratory-based tests such as FIB-4 to classify cirrhosis and elimination of pre-treatment genotyping improves the reproducibility of this study in primary care settings globally. The dispensation of the entire study course of treatment without jeopardizing efficacy also removes barriers associated with medication refills. Finally, while this study did not require pre-treatment genotyping, when samples were tested retrospectively, we identified participants with all genotypes 1–7.

Implications of all the available evidence

The data available cumulatively support the use of minimal monitoring approaches in the delivery of HCV therapy to non-decompensated cirrhotic populations living with HCV infection globally. Given the challenges with access to HCV genotyping and barriers associated with medication refill fulfillment, these data support the guidance to eliminate pre-treatment genotyping when using pangenotypic regimens, and suggest dispensation of the entire study treatment at initiation without compromising patient safety or treatment efficacy. Collectively these data support and provide added evidence for the use of simplified protocols for the delivery of HCV care. Such approaches will be critical to the achievement of HCV elimination.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank people living with HCV globally especially the ACTG A5360 participants who graciously participate in research studies globally. We would also like to acknowledge the ACTG leadership, the hepatitis transformative science group of the ACTG, and the statistical and data management center (SDMC) of the ACTG for their continued support and guidance. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of all the members of the ACTG 5360 team who oversaw the implementation of this trial.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636, and UM1 AI106701. Additional funding support and study product was provided by Gilead Sciences.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Sharing Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. Due to ethical restrictions, study data are available upon request from sdac.data@sdac.harvard.edu with the written agreement of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group.

Declaration of Interests

Sunil S Solomon declares grants and study products to the institution from Gilead sciences related to the submitted work as well as grants and study product to the institution from Gilead Sciences and Abbott Laboratories not related to the submitted work. He declares honoraria from Gilead Sciecnes. Gregory K Robbins declares grants to his institution from Gilead Sciences, Citius Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Emergent Biosolutions and Leonard Meron Bioscience, outside of the submitted work. He also declares consulting fees from Teradyne Inc., Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, and Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association. Annie Son and Nelson Cheinquer are employees of Gilead Sciences that provided funding and study product, and hold stock in the company. Estevao Portela Nunes declares honoraria from Gilead and Abbvie. Dimas Kliemann declares honoraria and support to attend conferences from Gilead Sciences. Jorge Santana declares speaker and advisory board honoraria from ViiV, Merck, Gilead and Abbvie. Pablo Tebas declares consulting fees from ViiV and Merck. C Benson declares grants from Gilead Sciences paid to her institution, outside of the submitted work, and served as the Chair of a DSMB for GlaxoSmithKline. Susanna Naggie declares grants from Gilead Sciences and Abbvie to her institution, outside of the submitted work. She also reports personal consulting fees from BioMarin and Theratechnologies, support to attend meetings from Gilead Sciences, and has participated on DSMB for Bristol Myers Squibb, FHI 360 and Personal Health Insights, Inc. She also holds stock options in Vir Bio. David Wyles declares grants to his institution from Gilead Sciences outside of the submitted work and discloses royalties/licenses from UpToDate. Mark Sulkowski declares grants to his institution from Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen and Assembly Biosciences outside of the submitted work. He also reports personal consulting fees from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Assembly Biosciences, Arbutus, Virion, Antios and GSK and has received honoraria from Practice Point Communication, DKB and Clinical Care Options. He has also served on DSMB and holds stock in Gilead Sciences and Abbvie. Christine Scello, Chanelle Wimbish, Sandra Wagner-Cardoso, Donald Anthony, Jaclyn Bennet, Anchalee Avihingsanon, Cissy Kityo, Irena Brates, Khuanchai Supparatpinyo, Benjamin Linas, Marije Van Schalkwyk and Leonard Sowah declare no conflicts.

References

- 1.Thomas DL. Global elimination of chronic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2041–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Interim guidance for country validation of viral hepatitis elimination. Guidance Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; June 8, 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240028395 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gamkrelidze I, Pawlotsky JM, Lazarus JV, et al. (2021). Progress towards hepatitis C virus elimination in high‐ income countries: An updated analysis. Liver Int 2021;41:456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linas BP, Nolen S. A Guide to the Economics of Hepatitis C Virus Cure in 2017. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2018;32:447–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Accelerating access to hepatitis C diagnostics and treatment. Overcoming barriers in low and middle-income countries. Global progress report 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1328465/retrieve

- 6.Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:161–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaillon A, Mehta SR, Hoenigl M, et al. Cost-effectiveness and budgetary impact of HCV treatment with direct-acting antivirals in India including the risk of reinfection. PLoS One 2019;14(6):e0217964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blach S, Kondili LA, Aghemo A, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on global HCV elimination efforts. J Hepatol 2021;74:31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AASLD. AASLD Practice Guidelines Alexandria, VA: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Available at: https://www.aasld.org/publications/practice-guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series. J Hepatol 2020;73:1170–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis JS, Young M, Marshall C, et al. Minimal compared with standard monitoring during sofosbuvir-based hepatitis C treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7(2):ofaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dore GJ, Feld JJ, Thompson A, et al. ; SMART-C Study Group. Simplified monitoring for hepatitis C virus treatment with glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir, a randomised non-inferiority trial. J Hepatol 2020;72:431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sood A, Duseja A, Kabrawala M, et al. Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir single-tablet regimen administered for 12 weeks in a phase 3 study with minimal monitoring in India. Hepatol Int 2019;13:173–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Nathan Clumeck N, et al. ; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006;43:1317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NIH. BLAST® Basic Local Alignment Search Tool US National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, NIH; 2021. Available at: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi [Google Scholar]

- 16.DAIDS. Division of AIDS (DAIDS) Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events. Corrected Version 2.1, July 2017. Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://rsc.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/daidsgradingcorrectedv21.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction 2008;103:1039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) Manual for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, Switzerland; January 2010. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924159938-2 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK, et al. ; ASTRAL-2 Investigators; ASTRAL-3 Investigators. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hezode C, et al. ; ASTRAL-1 Investigators. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangia A, Milligan S, Khalili M, et al. Global real-world evidence of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir as simple, effective HCV treatment: Analysis of 5552 patients from 12 cohorts. Liver Int 2020;40:1841–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilton J, Wong S, Yu A, et al. Real-world effectiveness of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir for treatment of chronic hepatitis C in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7(3):ofaa055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valway S, Jenison S, Keller N, Vega-Hernandez J, Hubbard McCree D. Risk assessment and screening for sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and hepatitis virus among long-distance truck drivers in New Mexico, 2004–2006. Am J Public Health 2009;99:2063–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pockros PJ. Black box warning for possible HBV reactivation during DAA therapy for chronic HCV infection. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;13:536–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bersoff-Matcha SJ, Cao K, Jason M, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation associated with direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus: a review of cases reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:792–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyles D, Brau N, Kottilil S, et al. ; ASTRAL-5 Investigators. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: an open-label, phase 3 study. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C, Nelson DR, Fried MW, Segal JB, Sulkowski MS. Oral direct- acting agent therapy for hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:637–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith D, Magri A, Bonsall D, et al. ; STOP-HCV Consortium. Resistance analysis of genotype 3 hepatitis C virus indicates subtypes inherently resistant to nonstructural protein 5A inhibitors. Hepatology 2019;69:1861–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Mole LA, Backus LI. Real-world effectiveness of daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir and velpatasvir/sofosbuvir in hepatitis C genotype 2 and 3. J Hepatol 2019;70:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grebely J, Lamoury FMJ, Hajarizadeh B, et al. ; LiveRLife Study Group. Evaluation of the Xpert HCV Viral Load point-of-care assay from venipuncture-collected and finger-stick capillary whole- blood samples: a cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:514–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freiman JM, Tran TM, Schumacher SG, et al. Hepatitis C core antigen testing for diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:345–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang M, O’Keefe D, Craig J, et al. Decentralised hepatitis C testing and treatment in rural Cambodia: evaluation of a simplified service model integrated in an existing public health system. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiha G, Soliman R, Serwah A, Mikhail NNH, Asselah T, Easterbrook P. A same day ‘test and treat’ model for chronic HCV and HBV infection: Results from two community-based pilot studies in Egypt. J Viral Hepat 2020;27:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.